User login

Plantar Ulcerative Lichen Planus: Rapid Improvement With a Novel Triple-Therapy Approach

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

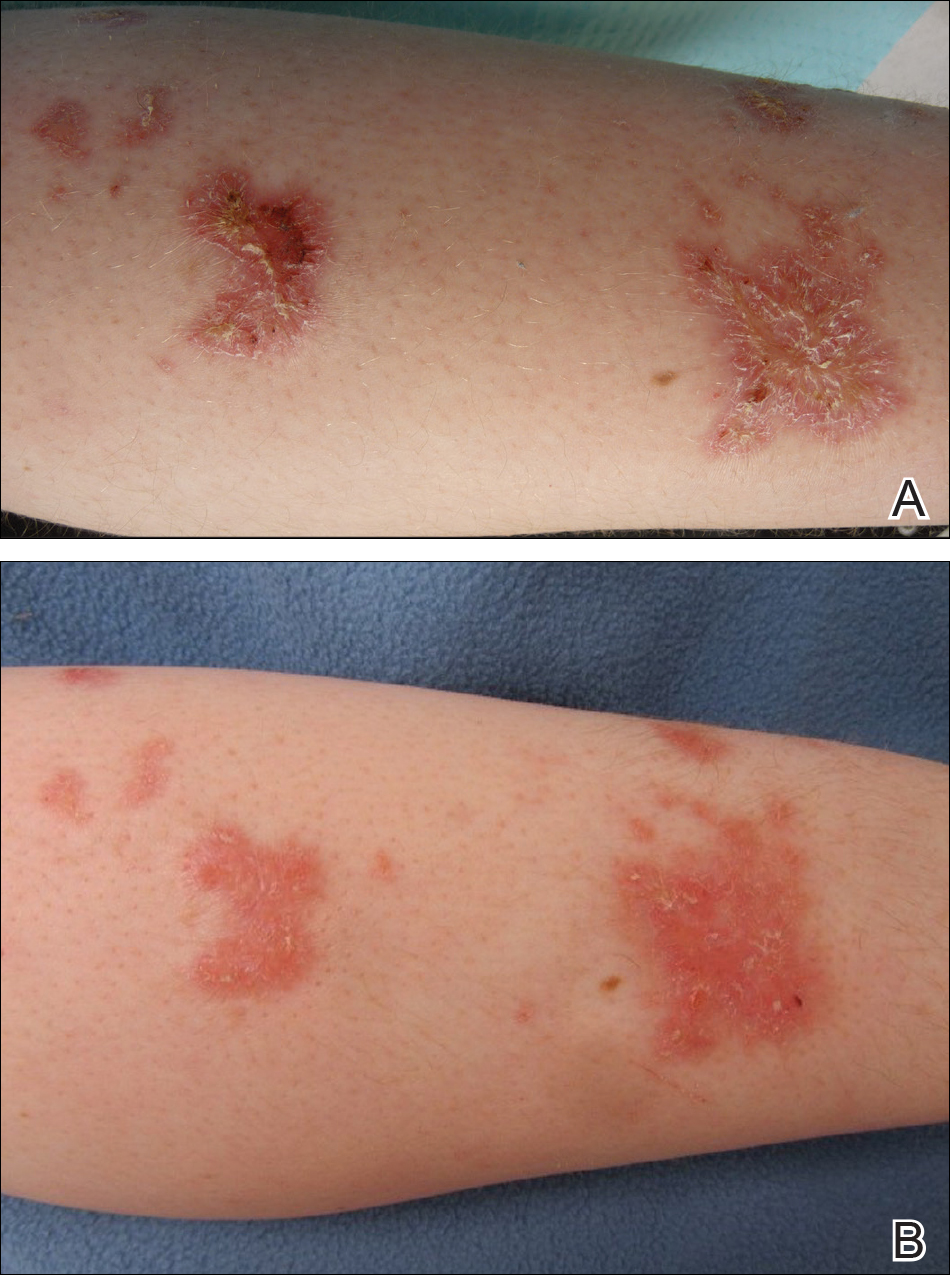

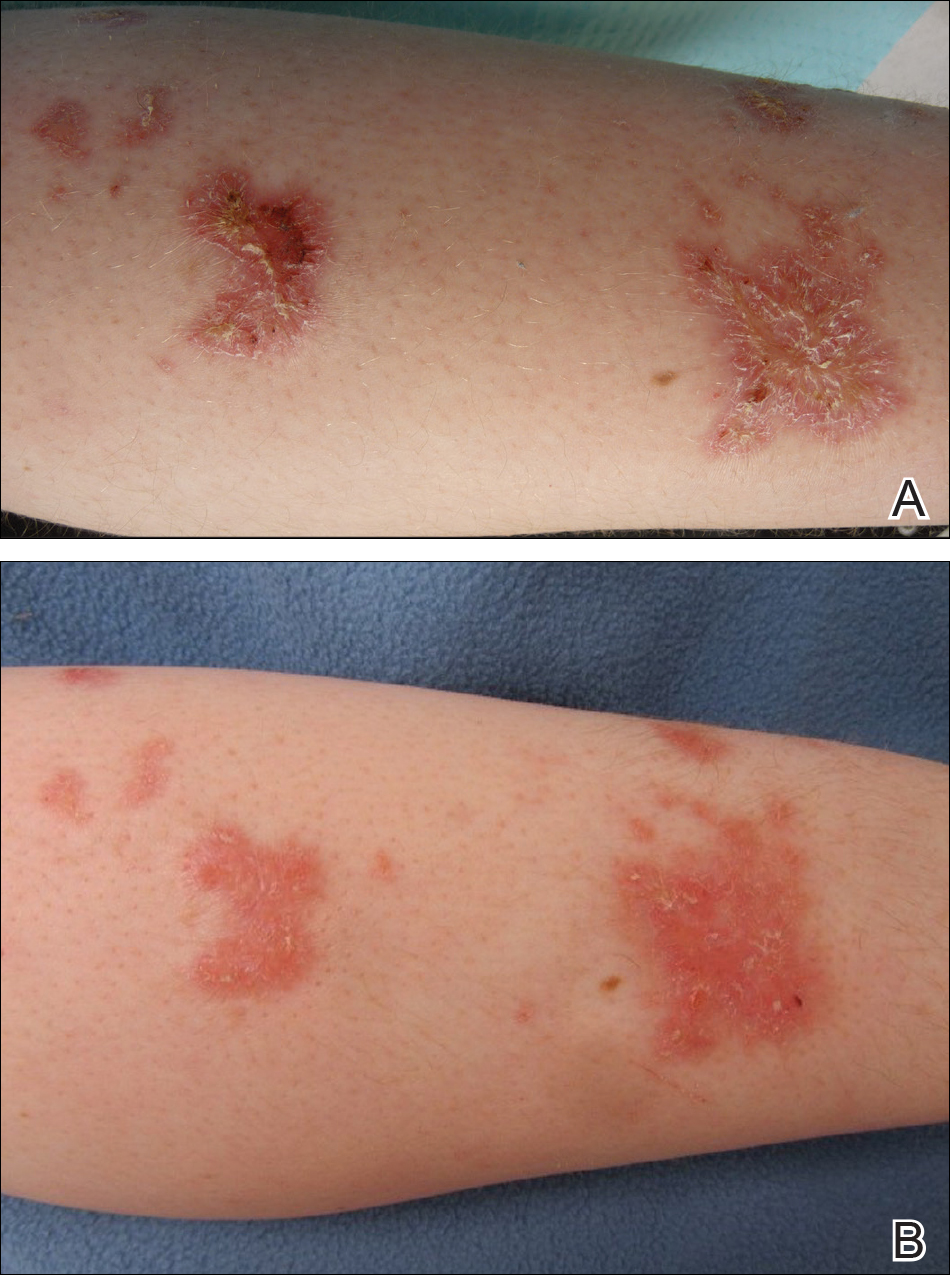

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

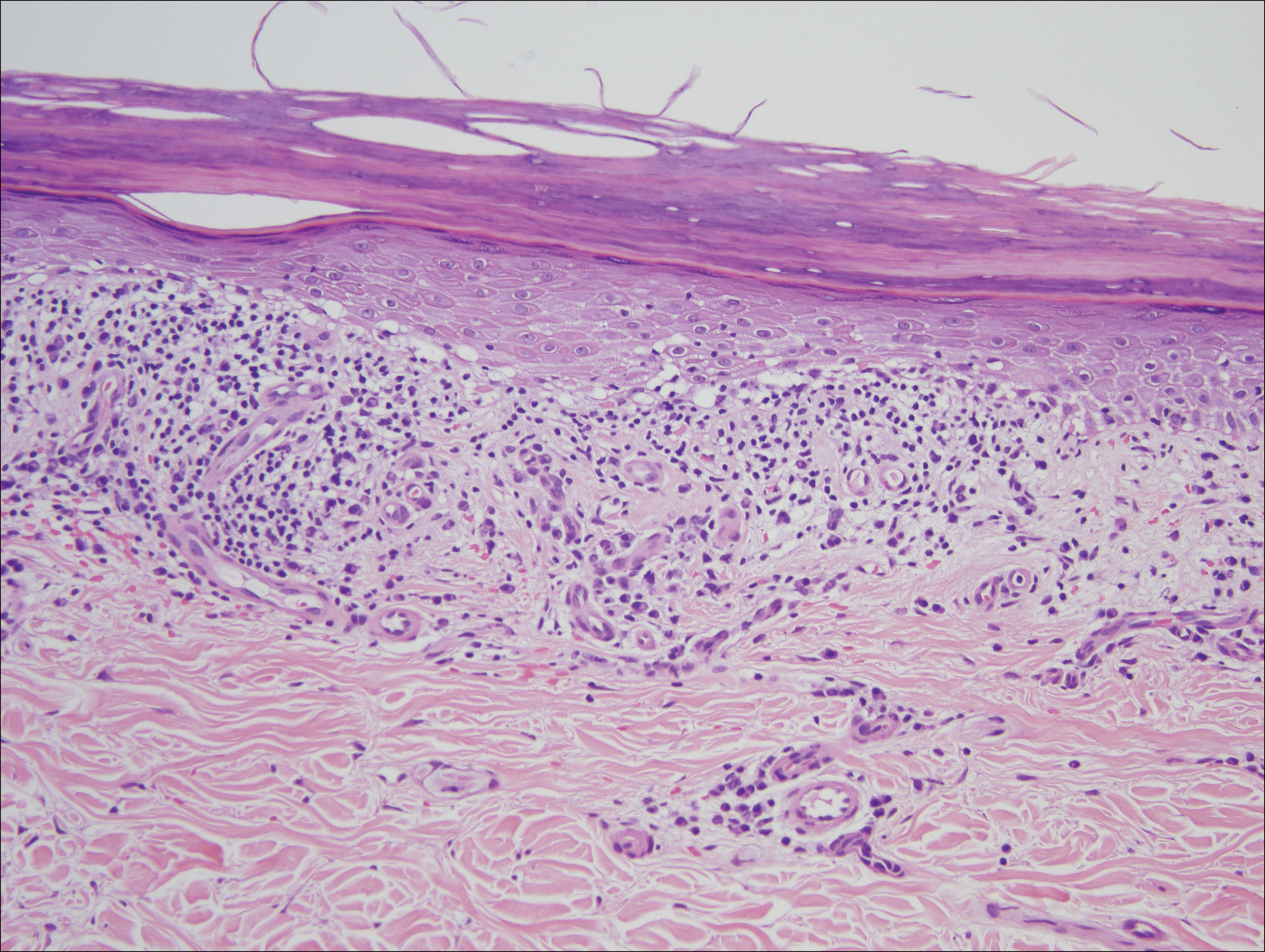

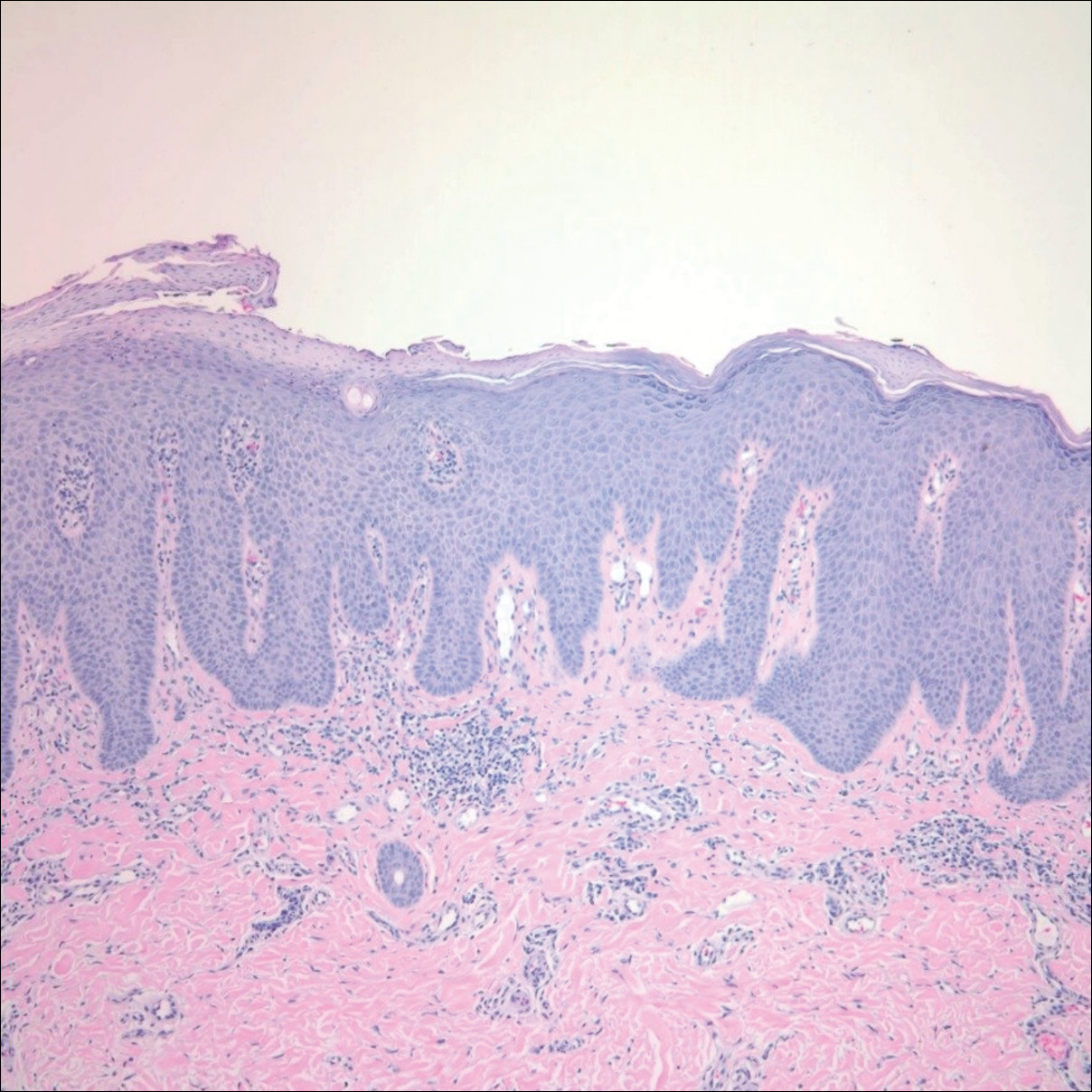

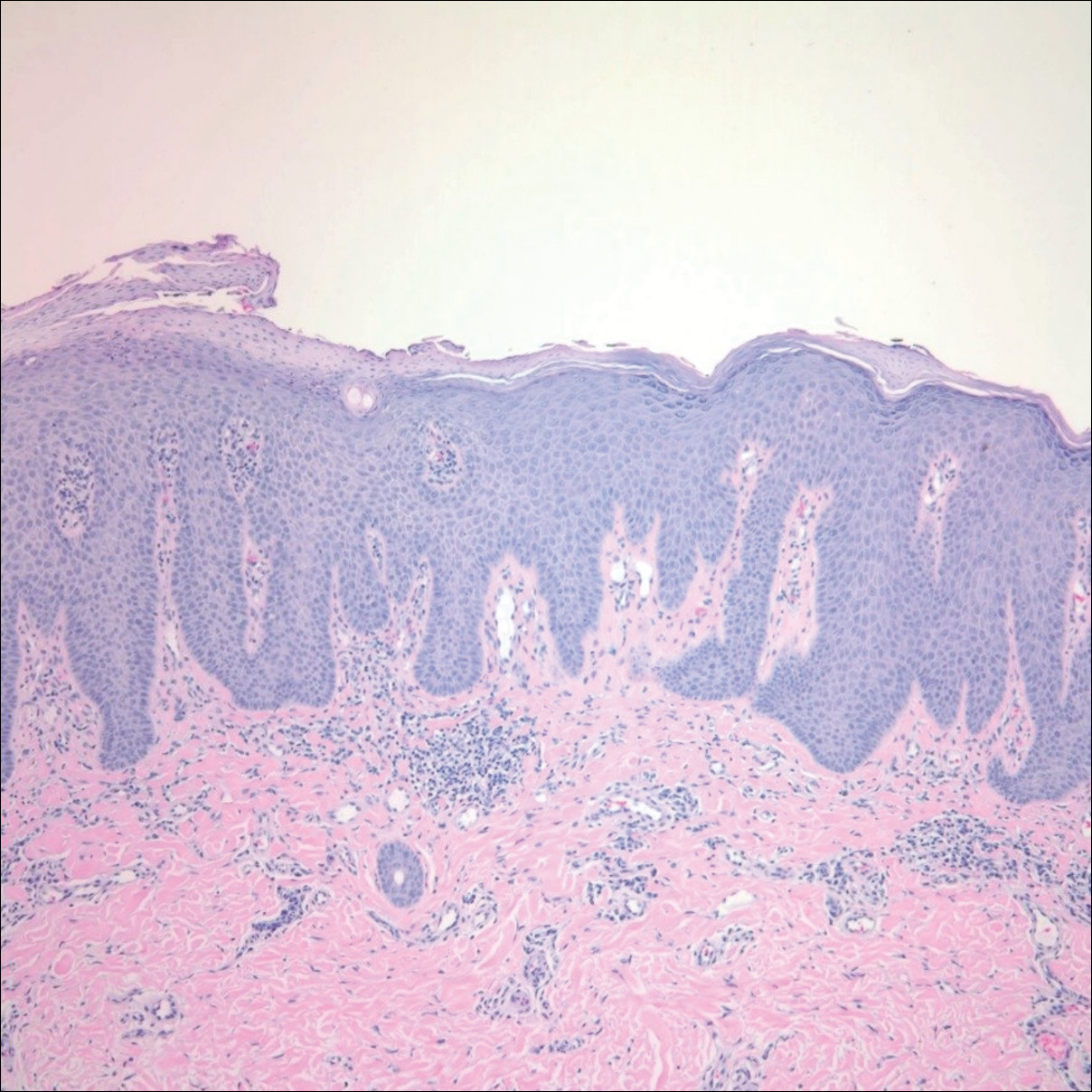

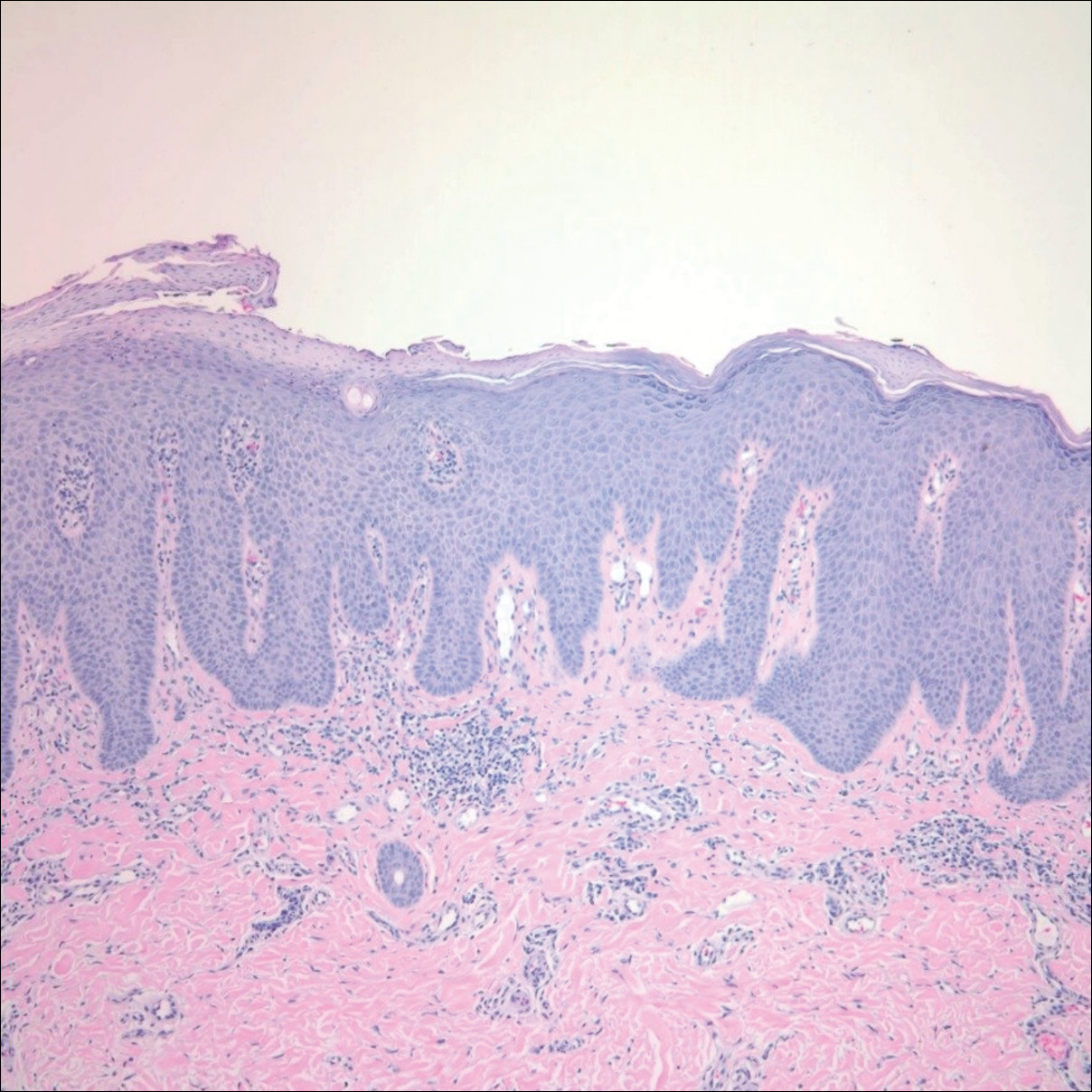

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

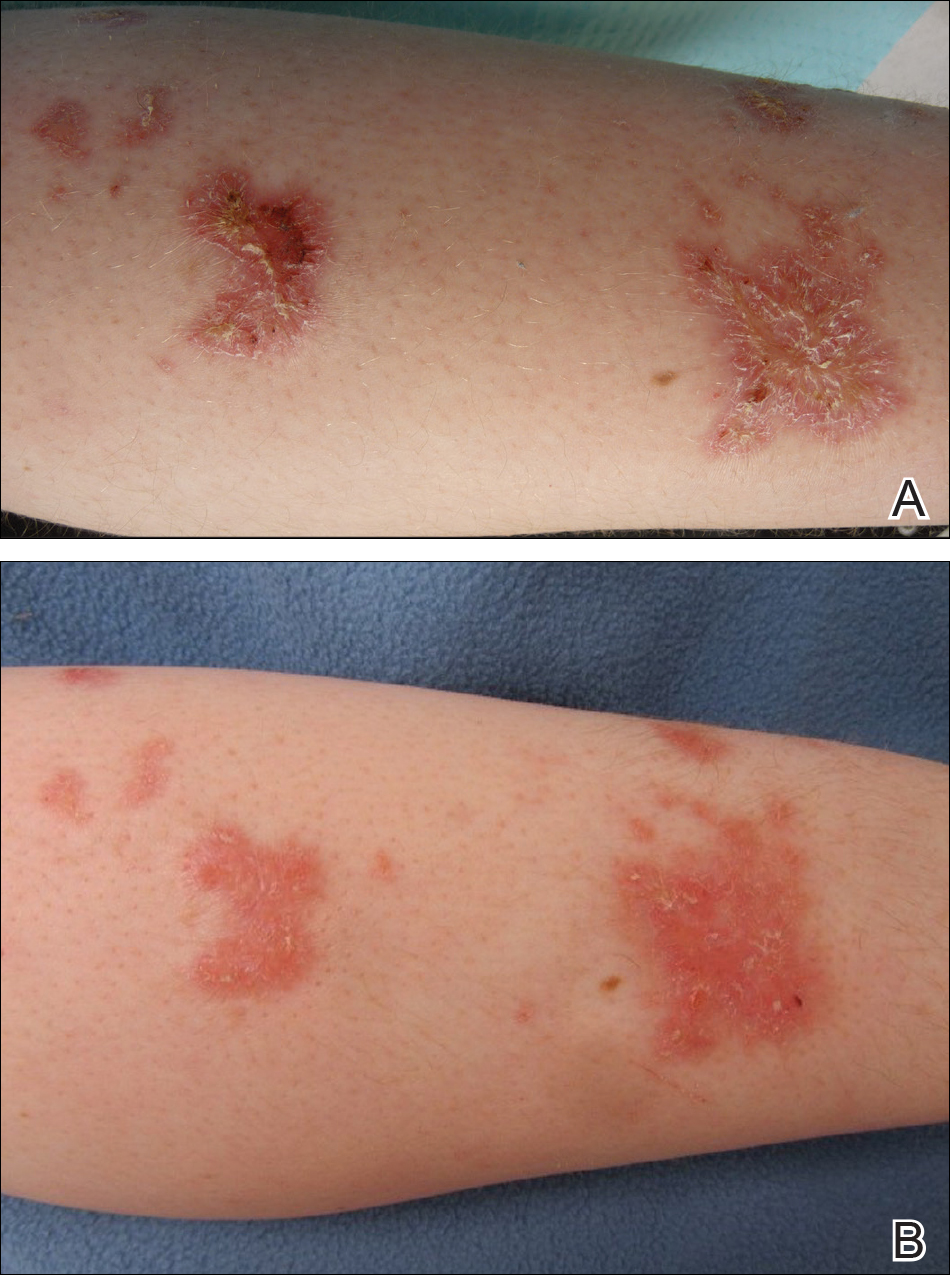

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

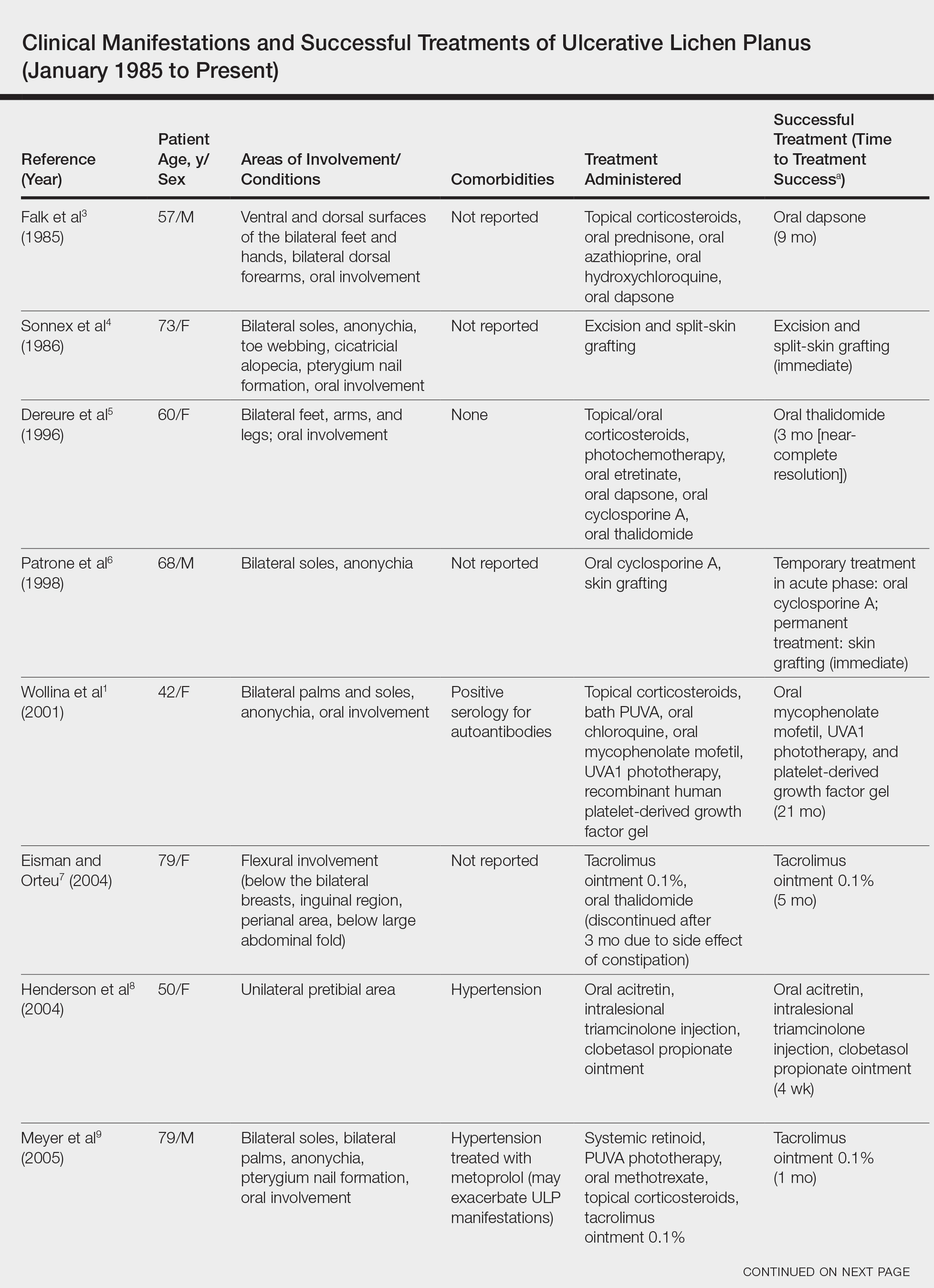

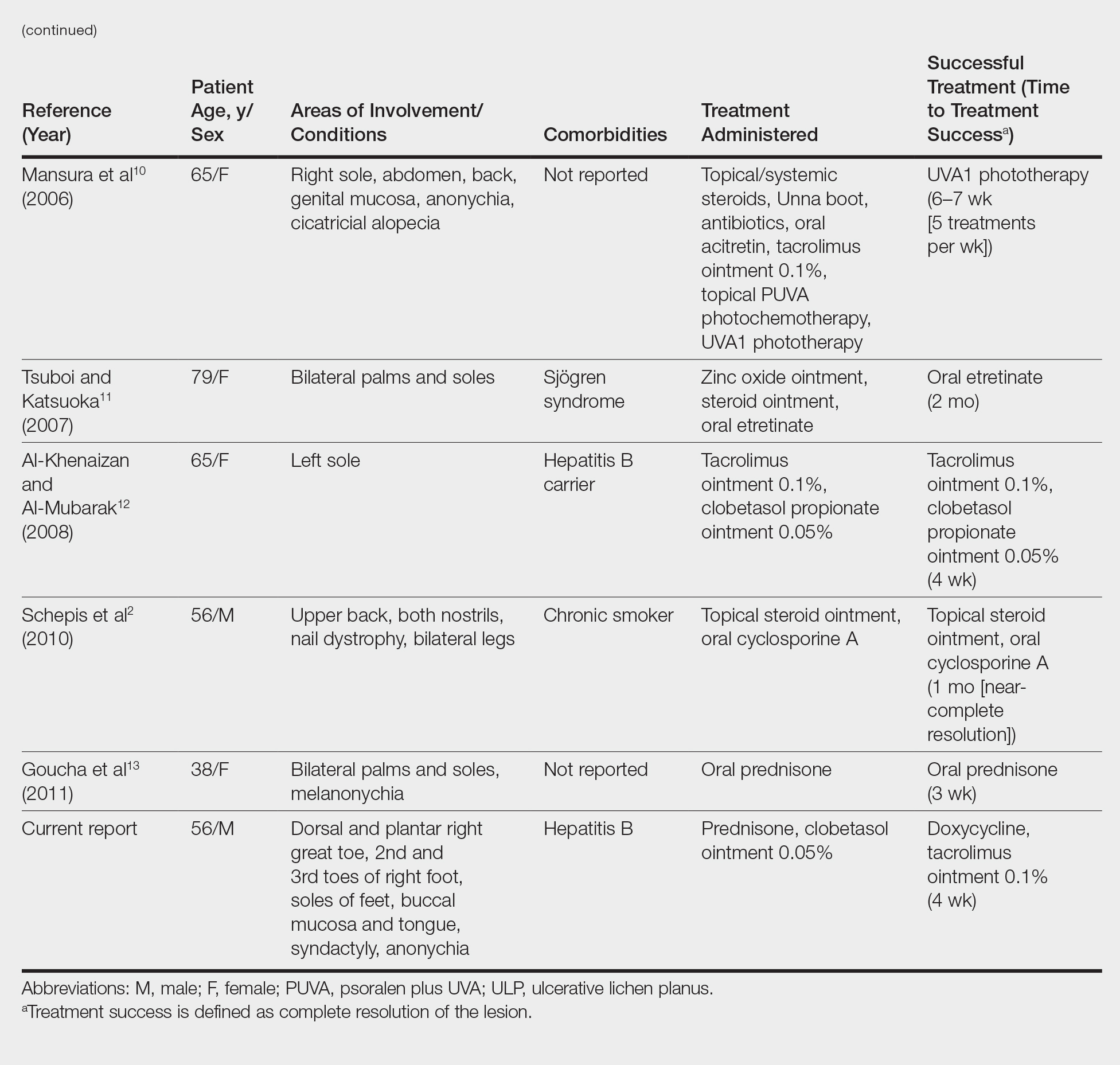

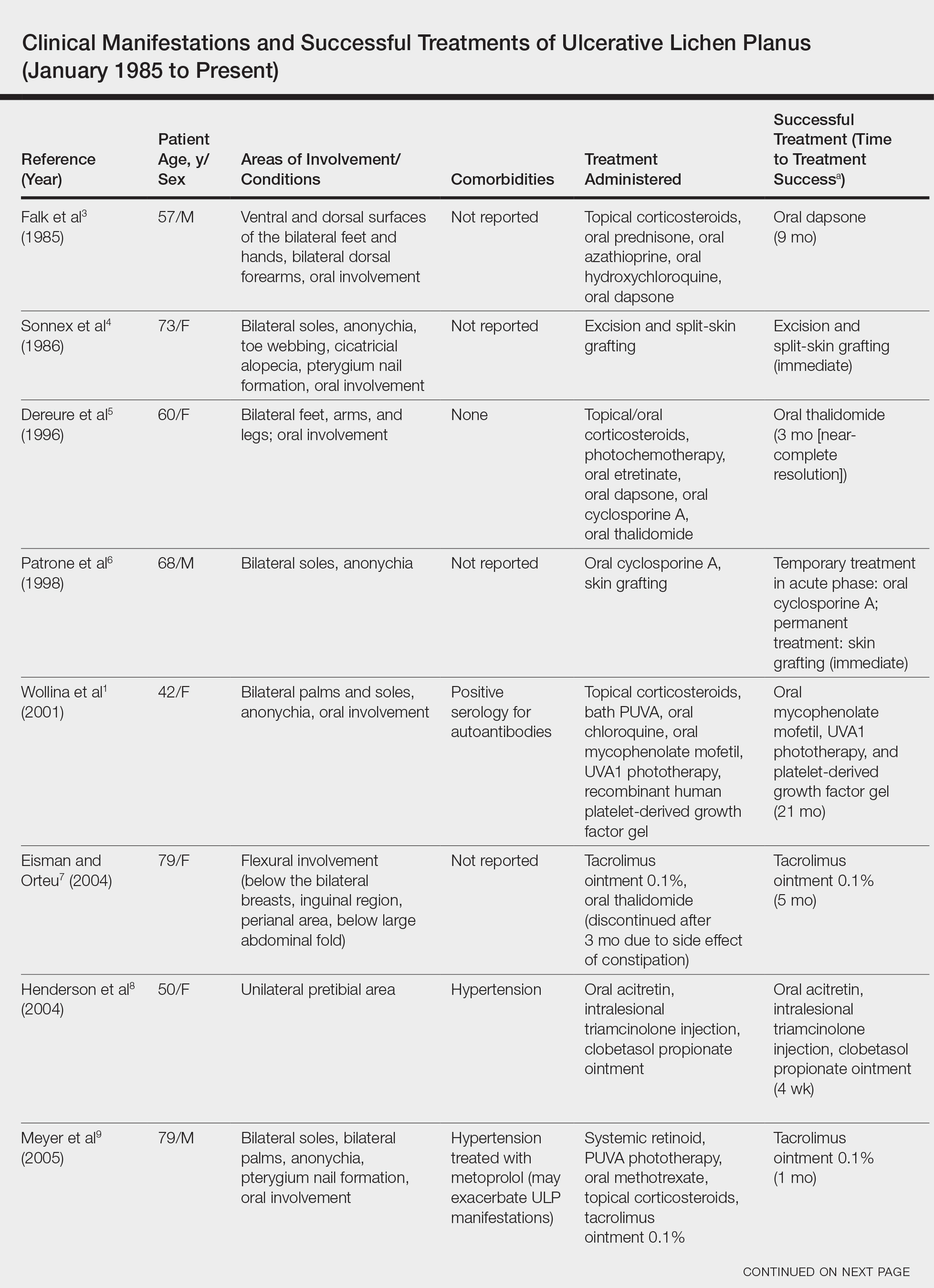

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

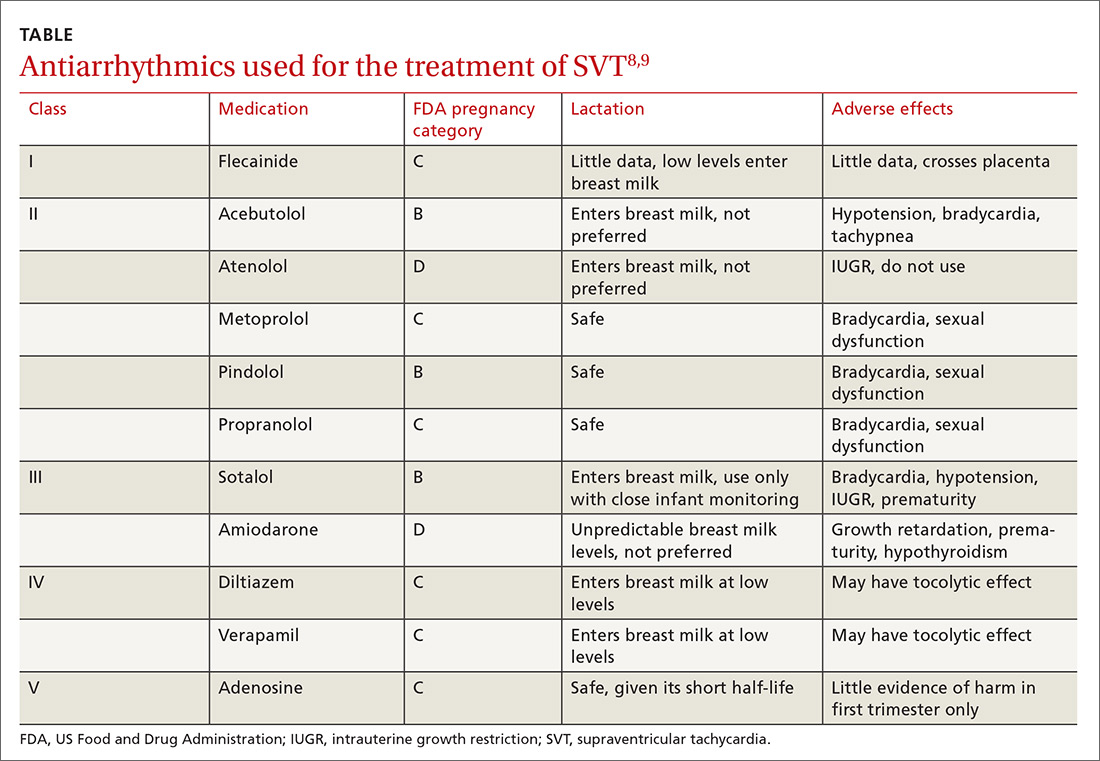

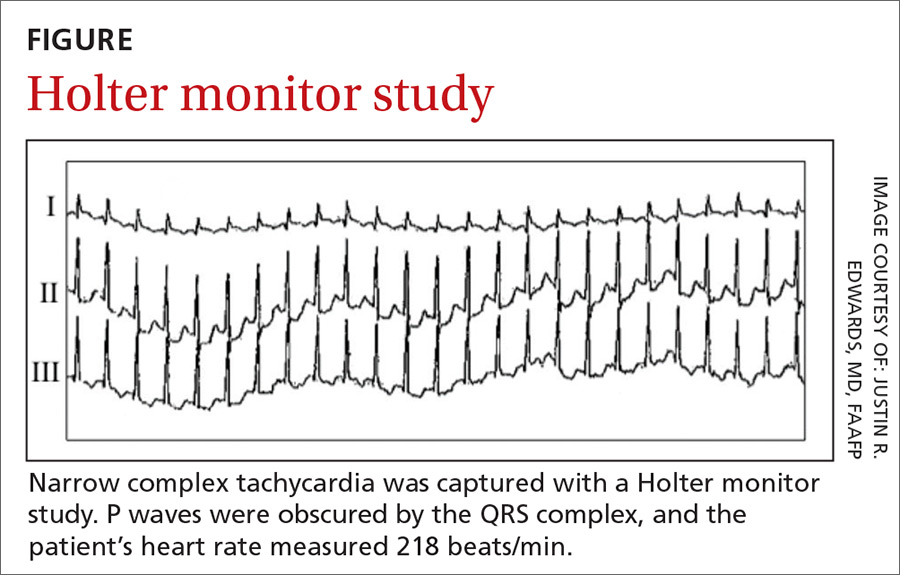

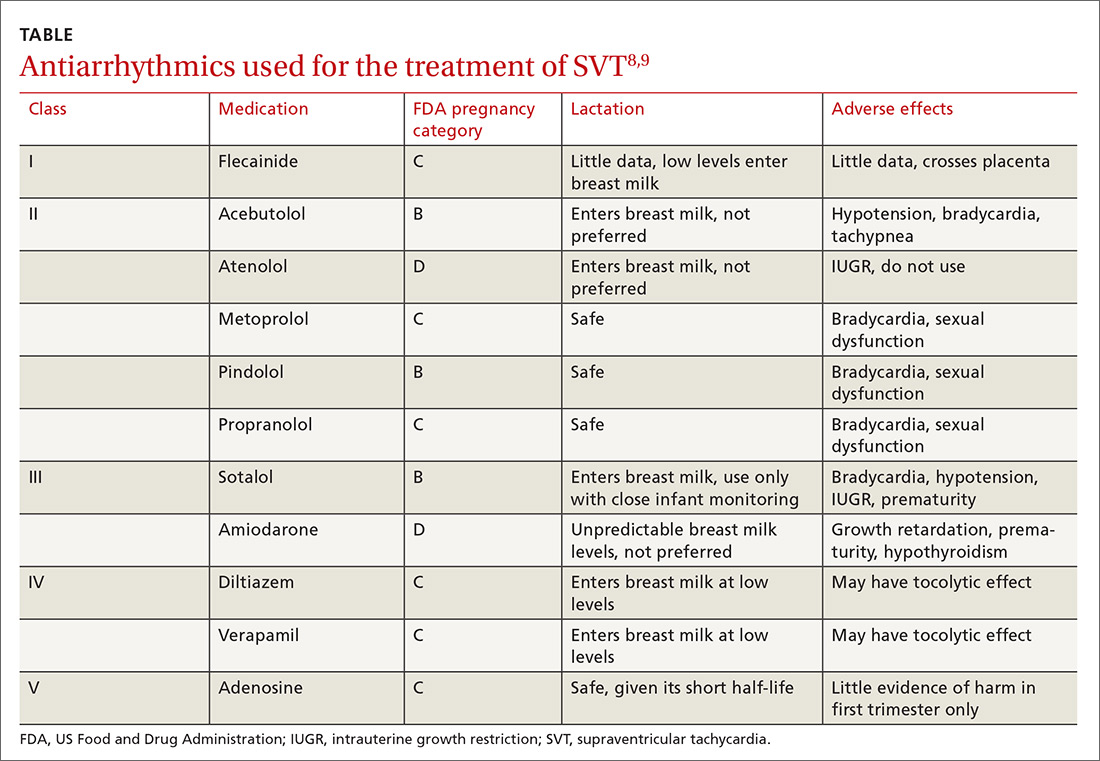

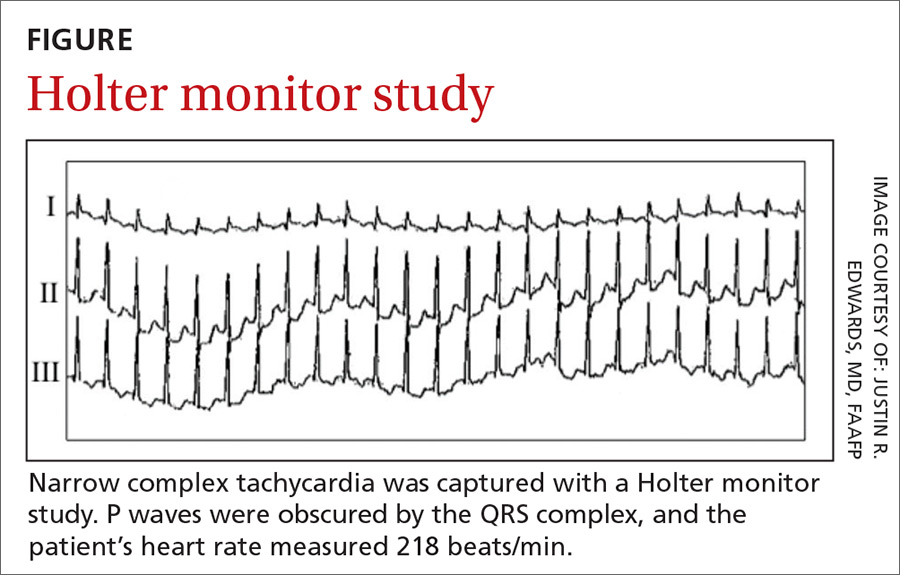

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Practice Points

- Consider ulcerative lichen planus (ULP) for chronic wounds on the soles.

- Topical therapeutic options may present a rapidly effective and relatively safe alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term management of plantar ULP.

Deer Ked: A Lyme-Carrying Ectoparasite on the Move

How to Prevent Mosquito and Tick-Borne Disease

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic 1 day after mountain biking in the woods in Hartford County, Connecticut. He stated that he found a tick attached to his shirt after riding (Figure). Careful examination of the patient showed no signs of a bite reaction. The insect was identified via microscopy as the deer ked Lipoptena cervi.

Comment

Lipoptena cervi, known as the deer ked, is an ectoparasite of cervids traditionally found in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.1 The deer ked was first reported in American deer in 2 independent sightings in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire in 1907.2 More recently deer keds have been reported in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.3 In the United States, L cervi is thought to be an invasive species transported from Europe in the 1800s.4,5 The main host is thought to be the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus viginianus). Once a suitable host is found, the deer ked sheds its wings and crawls into the fur. After engorging on a blood meal, it deposits prepupae that fall from the host and mature into winged adults during the late summer into the autumn. Adults may exhibit swarming behavior, and it is during this host-seeking activity that they land on humans.3

Following the bite of a deer ked, there are reports of long-lasting dermatitis in both humans and dogs.1,4,6 One case series involving 19 patients following deer ked bites reported pruritic bite papules.4 The reaction appeared to be treatment resistant and lasted from 2 weeks to 12 months. Histologic examination was typical for arthropod assault. Of 11 papules that were biopsied, most (7/11) showed C3 deposition in dermal vessel walls under direct immunofluorescence. Of 19 patients, 57% had elevated serum IgE levels.4

In addition to the associated dermatologic findings, the deer ked is a vector of various infectious agents. Bartonella schoenbuchensis has been isolated from deer ked in Massachusettes.7 A recent study found a 75% prevalence of Bartonella species in 217 deer keds collected from red deer in Poland.5 The first incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophylum in deer keds was reported in the United States in 2016. Of 48 adult deer keds collected from an unknown number of deer, 19 (40%), 14 (29%), and 3 (6%) were positive for B burgdorferi, A phagocytophylum, and both on polymerase chain reaction, respectively.3

A recent study from Europe showed deer keds are now more frequently found in regions where they had not previously been observed.8 It stands to reason that with climate change, L cervi and other disease-carrying vectors are likely to migrate to and inhabit new regions of the country. Even in the current climate, there are more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied in medicine, and all patients who experience an arthropod assault should be monitored for signs of systemic disease.

- Mysterud A, Madslien K, Herland A, et al. Phenology of deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) host-seeking flight activity and its relationship with prevailing autumn weather. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:95.

- Bequaert JC. A Monograph of the Melophaginae or Ked-flies of Sheep, Goats, Deer, and Antelopes (Diptera, Hippoboscidae). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Entomological Society; 1942.

- Buss M, Case L, Kearney B, et al. Detection of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis pathogens via PCR in Pennsylvania deer ked. J Vector Ecol. 2016;41:292-294.

- Rantanen T, Reunala T, Vuojolahti P, et al. Persistent pruritic papules from deer ked bites. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:307-311.

- Szewczyk T, Werszko J, Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:487.

- Hermosilla C, Pantchev N, Bachmann R, et al. Lipoptena cervi (deer ked) in two naturally infested dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;159:286-287.

- Matsumoto K, Berrada ZL, Klinger E, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella schoenbuchensis from ectoparasites of deer in Massachusetts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:549-554.

- Sokół R, Gałęcki R. Prevalence of keds on city dogs in central Poland. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:114-116.

How to Prevent Mosquito and Tick-Borne Disease

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic 1 day after mountain biking in the woods in Hartford County, Connecticut. He stated that he found a tick attached to his shirt after riding (Figure). Careful examination of the patient showed no signs of a bite reaction. The insect was identified via microscopy as the deer ked Lipoptena cervi.

Comment

Lipoptena cervi, known as the deer ked, is an ectoparasite of cervids traditionally found in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.1 The deer ked was first reported in American deer in 2 independent sightings in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire in 1907.2 More recently deer keds have been reported in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.3 In the United States, L cervi is thought to be an invasive species transported from Europe in the 1800s.4,5 The main host is thought to be the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus viginianus). Once a suitable host is found, the deer ked sheds its wings and crawls into the fur. After engorging on a blood meal, it deposits prepupae that fall from the host and mature into winged adults during the late summer into the autumn. Adults may exhibit swarming behavior, and it is during this host-seeking activity that they land on humans.3

Following the bite of a deer ked, there are reports of long-lasting dermatitis in both humans and dogs.1,4,6 One case series involving 19 patients following deer ked bites reported pruritic bite papules.4 The reaction appeared to be treatment resistant and lasted from 2 weeks to 12 months. Histologic examination was typical for arthropod assault. Of 11 papules that were biopsied, most (7/11) showed C3 deposition in dermal vessel walls under direct immunofluorescence. Of 19 patients, 57% had elevated serum IgE levels.4

In addition to the associated dermatologic findings, the deer ked is a vector of various infectious agents. Bartonella schoenbuchensis has been isolated from deer ked in Massachusettes.7 A recent study found a 75% prevalence of Bartonella species in 217 deer keds collected from red deer in Poland.5 The first incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophylum in deer keds was reported in the United States in 2016. Of 48 adult deer keds collected from an unknown number of deer, 19 (40%), 14 (29%), and 3 (6%) were positive for B burgdorferi, A phagocytophylum, and both on polymerase chain reaction, respectively.3

A recent study from Europe showed deer keds are now more frequently found in regions where they had not previously been observed.8 It stands to reason that with climate change, L cervi and other disease-carrying vectors are likely to migrate to and inhabit new regions of the country. Even in the current climate, there are more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied in medicine, and all patients who experience an arthropod assault should be monitored for signs of systemic disease.

How to Prevent Mosquito and Tick-Borne Disease

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic 1 day after mountain biking in the woods in Hartford County, Connecticut. He stated that he found a tick attached to his shirt after riding (Figure). Careful examination of the patient showed no signs of a bite reaction. The insect was identified via microscopy as the deer ked Lipoptena cervi.

Comment

Lipoptena cervi, known as the deer ked, is an ectoparasite of cervids traditionally found in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.1 The deer ked was first reported in American deer in 2 independent sightings in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire in 1907.2 More recently deer keds have been reported in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.3 In the United States, L cervi is thought to be an invasive species transported from Europe in the 1800s.4,5 The main host is thought to be the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus viginianus). Once a suitable host is found, the deer ked sheds its wings and crawls into the fur. After engorging on a blood meal, it deposits prepupae that fall from the host and mature into winged adults during the late summer into the autumn. Adults may exhibit swarming behavior, and it is during this host-seeking activity that they land on humans.3

Following the bite of a deer ked, there are reports of long-lasting dermatitis in both humans and dogs.1,4,6 One case series involving 19 patients following deer ked bites reported pruritic bite papules.4 The reaction appeared to be treatment resistant and lasted from 2 weeks to 12 months. Histologic examination was typical for arthropod assault. Of 11 papules that were biopsied, most (7/11) showed C3 deposition in dermal vessel walls under direct immunofluorescence. Of 19 patients, 57% had elevated serum IgE levels.4

In addition to the associated dermatologic findings, the deer ked is a vector of various infectious agents. Bartonella schoenbuchensis has been isolated from deer ked in Massachusettes.7 A recent study found a 75% prevalence of Bartonella species in 217 deer keds collected from red deer in Poland.5 The first incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophylum in deer keds was reported in the United States in 2016. Of 48 adult deer keds collected from an unknown number of deer, 19 (40%), 14 (29%), and 3 (6%) were positive for B burgdorferi, A phagocytophylum, and both on polymerase chain reaction, respectively.3

A recent study from Europe showed deer keds are now more frequently found in regions where they had not previously been observed.8 It stands to reason that with climate change, L cervi and other disease-carrying vectors are likely to migrate to and inhabit new regions of the country. Even in the current climate, there are more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied in medicine, and all patients who experience an arthropod assault should be monitored for signs of systemic disease.

- Mysterud A, Madslien K, Herland A, et al. Phenology of deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) host-seeking flight activity and its relationship with prevailing autumn weather. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:95.

- Bequaert JC. A Monograph of the Melophaginae or Ked-flies of Sheep, Goats, Deer, and Antelopes (Diptera, Hippoboscidae). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Entomological Society; 1942.

- Buss M, Case L, Kearney B, et al. Detection of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis pathogens via PCR in Pennsylvania deer ked. J Vector Ecol. 2016;41:292-294.

- Rantanen T, Reunala T, Vuojolahti P, et al. Persistent pruritic papules from deer ked bites. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:307-311.

- Szewczyk T, Werszko J, Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:487.

- Hermosilla C, Pantchev N, Bachmann R, et al. Lipoptena cervi (deer ked) in two naturally infested dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;159:286-287.

- Matsumoto K, Berrada ZL, Klinger E, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella schoenbuchensis from ectoparasites of deer in Massachusetts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:549-554.

- Sokół R, Gałęcki R. Prevalence of keds on city dogs in central Poland. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:114-116.

- Mysterud A, Madslien K, Herland A, et al. Phenology of deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) host-seeking flight activity and its relationship with prevailing autumn weather. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:95.

- Bequaert JC. A Monograph of the Melophaginae or Ked-flies of Sheep, Goats, Deer, and Antelopes (Diptera, Hippoboscidae). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Entomological Society; 1942.

- Buss M, Case L, Kearney B, et al. Detection of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis pathogens via PCR in Pennsylvania deer ked. J Vector Ecol. 2016;41:292-294.

- Rantanen T, Reunala T, Vuojolahti P, et al. Persistent pruritic papules from deer ked bites. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:307-311.

- Szewczyk T, Werszko J, Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:487.

- Hermosilla C, Pantchev N, Bachmann R, et al. Lipoptena cervi (deer ked) in two naturally infested dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;159:286-287.

- Matsumoto K, Berrada ZL, Klinger E, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella schoenbuchensis from ectoparasites of deer in Massachusetts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:549-554.

- Sokół R, Gałęcki R. Prevalence of keds on city dogs in central Poland. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:114-116.

Practice Points

- There are many more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied by scientists and physicians.

- Even if the insect cannot be identified, it is important to monitor patients who have experienced arthropod assault for signs of clinical diseases.

Latex Hypersensitivity to Injection Devices for Biologic Therapies in Psoriasis Patients

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

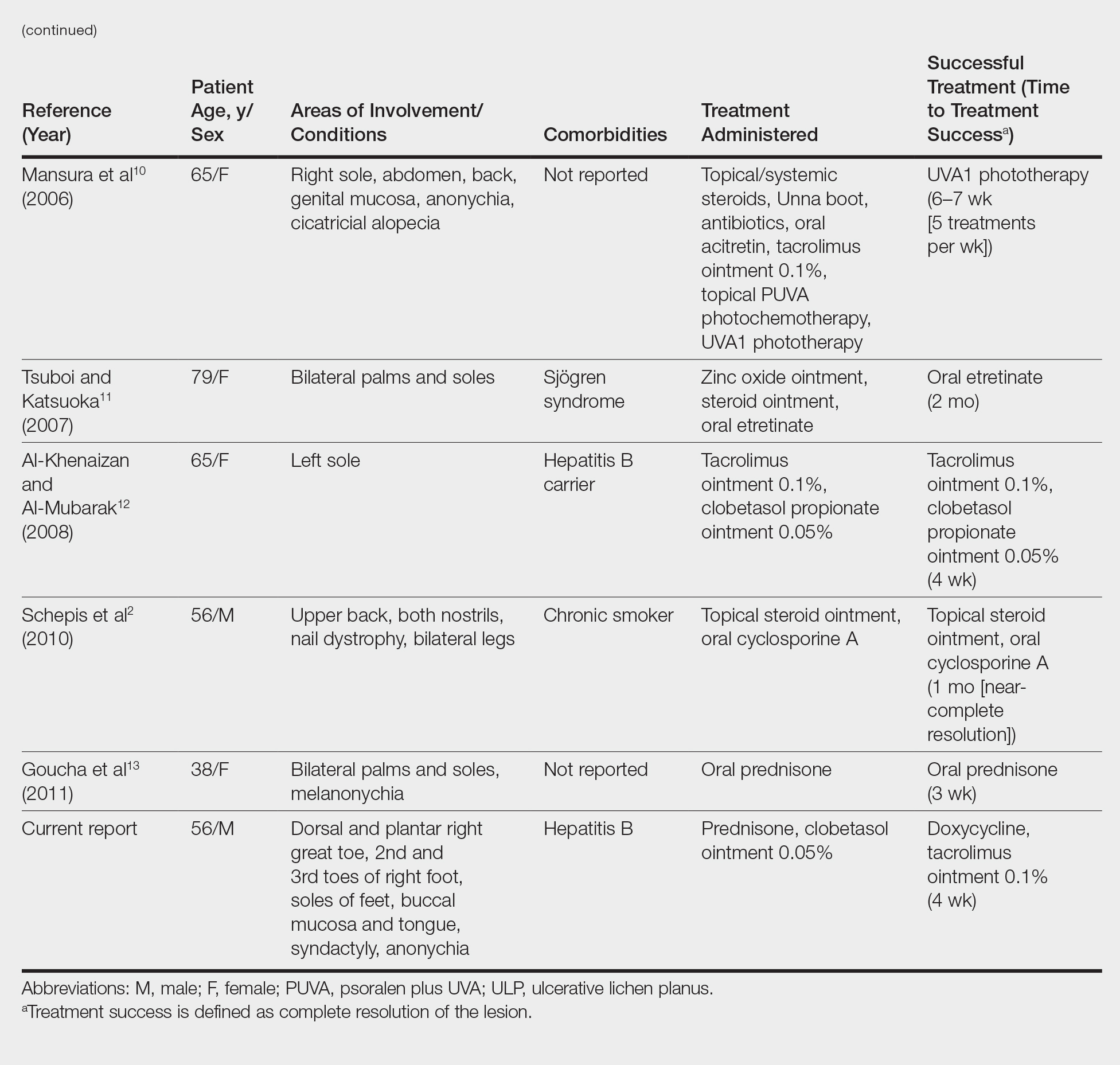

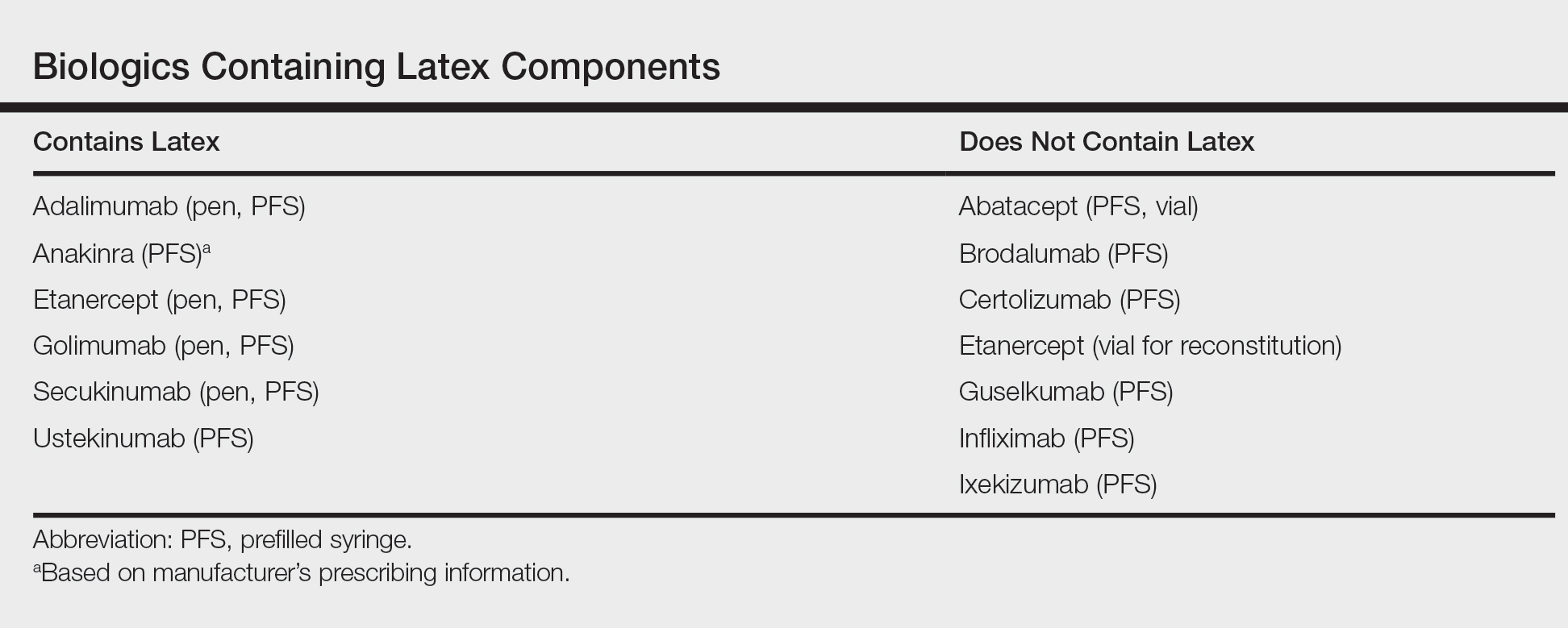

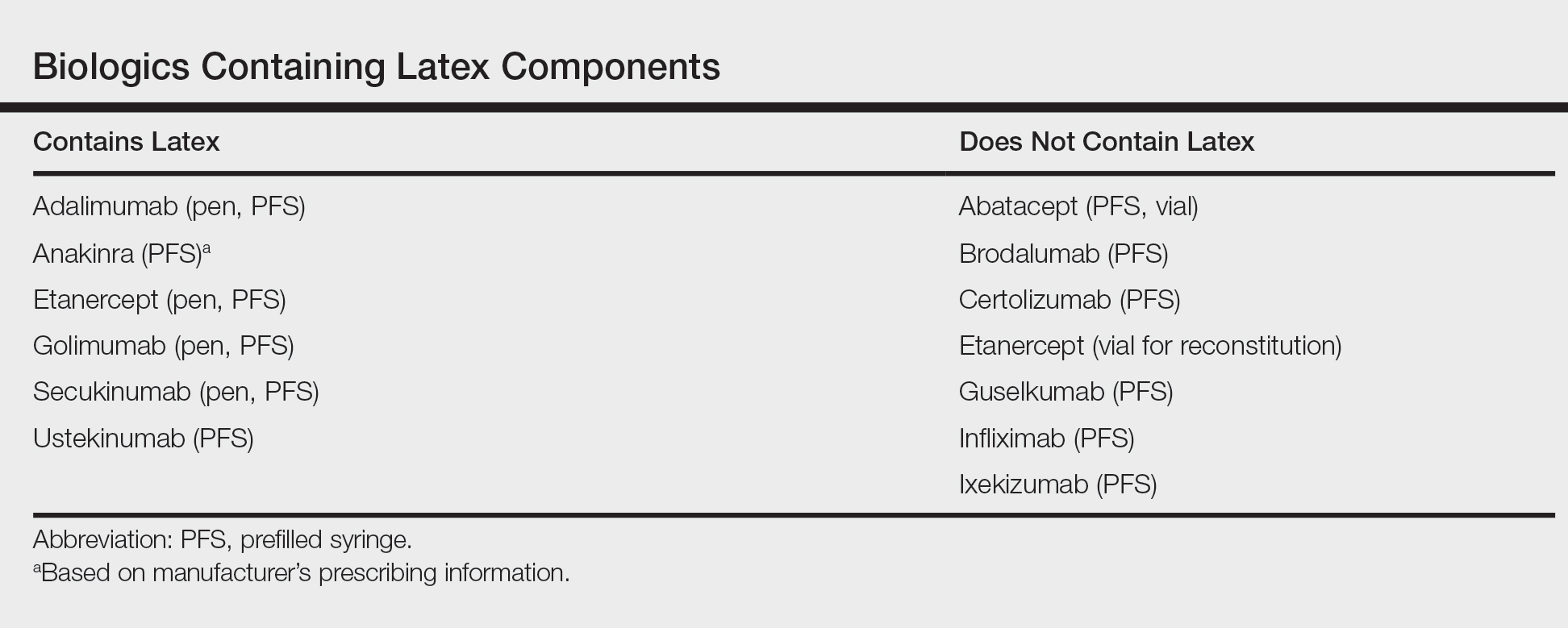

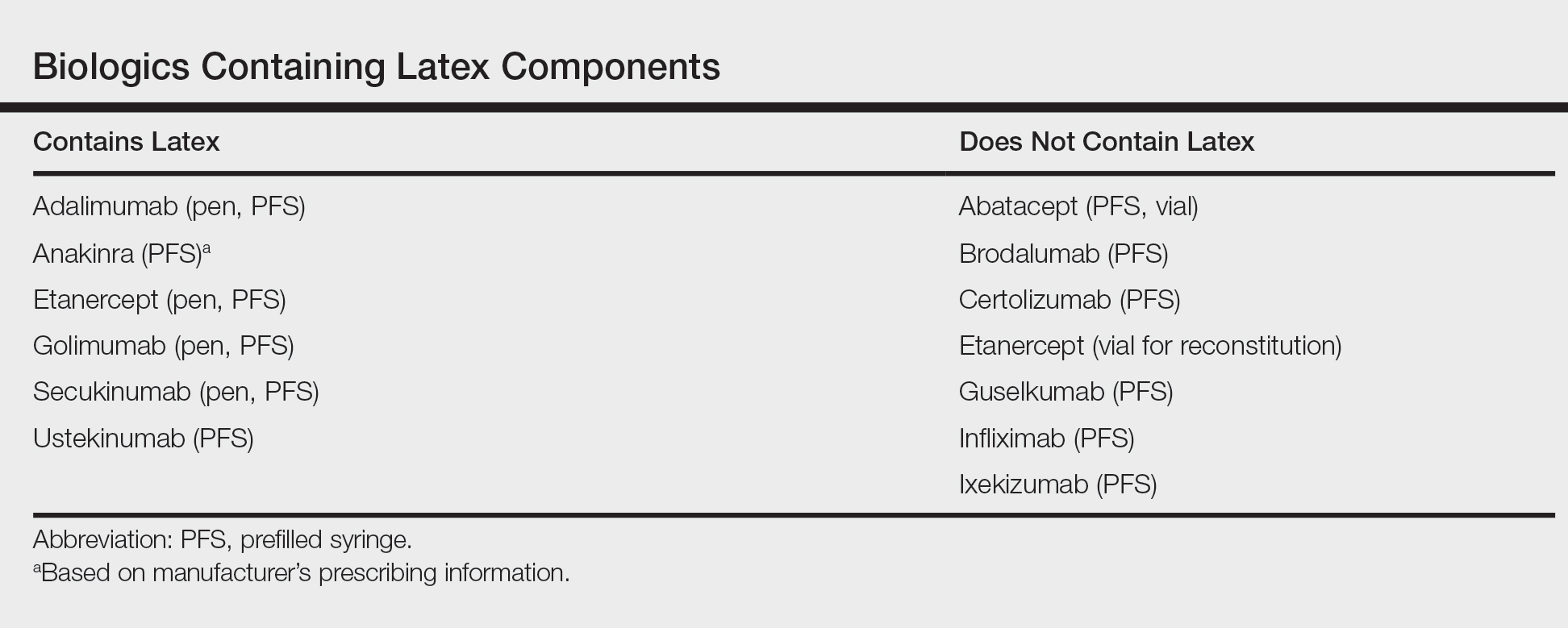

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus Responsive to 308-nm Excimer Laser Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis

Despite the histopathologic overlap with psoriasis, ILVEN exhibits fewer Ki-67-positive keratinocyte nuclei (proliferative marker) and more cytokeratin 10-positive cells (epidermal differentiation marker) than psoriasis.16 Furthermore, ILVEN has demonstrated fewer CD4−, CD8−, CD45RO−, CD2−, CD25−, CD94−, and CD161+ cells within the dermis and epidermis than psoriasis.16

The clinical presentations of ILVEN and psoriasis may be similar, as some patients with linear psoriasis also present with psoriatic plaques along the lines of Blaschko.17 Additionally, ILVEN may be a precursor to psoriasis. Altman and Mehregan1 found that ILVEN patients who developed psoriasis did so in areas previously affected by ILVEN; however, they continued to distinguish the 2 pathologies as distinct entities. Another early report also hypothesized that the dermoepidermal defect caused by epidermal nevi provided a site for the development of psoriatic lesions because of the Koebner phenomenon.18

Patients with ILVEN also have been found to have extracutaneous manifestations and symptoms commonly seen in psoriasis patients. A 2012 retrospective review revealed that 37% (7/19) of patients with ILVEN also had psoriatic arthritis, cutaneous psoriatic lesions, and/or nail pitting. The authors concluded that ILVEN may lead to the onset of psoriasis later in life and may indicate an underlying psoriatic predisposition.19 Genetic theories also have been proposed, stating that ILVEN may be a mosaic of psoriasis2 or that a postzygotic mutation leads to the predisposition for developing psoriasis.20

Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus frequently is refractory to treatment; however, the associated pruritus and distressing cosmesis make treatment attempts worthwhile.11 No single therapy has been found to be successful in all patients. A widely used first-line treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the former typically used with occlusion.13 Other treatments include adalimumab, calcipotriol,22,23 tretinoin,24 and 5-fluorouracil.24 Physical modalities such as cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, and dermabrasion have been reported with varying success.15,24 Surgical treatments include tangential25 and full-thickness excisions.26