User login

She’s Not My Mother: A 24-Year-Old Man With Capgras Delusion

Many patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals present with delusions; however, the Capgras delusion is a rare type that often appears as a sequela of certain medical and neurologic conditions.1 The Capgras delusion is a condition in which a person believes that either an individual or a group of people has been replaced by doubles or imposters.

In 1923, French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras first described the delusion. He and Jean Reboul-Lachaux coauthored a paper on a 53-year-old woman. The patient was a paranoid megalomaniac who “transformed everyone in her entourage, even those closest to her, such as her husband and daughter, into various and numerous doubles.”2 She believed she was famous, wealthy, and of royal lineage. Although 3 of her children had died, she believed that they were abducted, and that her only surviving child was replaced by a look-alike.2,3 Although the prevalence of such delusions in the general population has not been fully studied, a psychiatric hospital in Turkey found a 1.3% prevalence (1.8% women and 0.9% men) in 920 admissions over 5 years.4

The Capgras delusion is one of many delusions related to the misidentification of people, places, or objects; these delusions collectively are known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS).5,6 The Fregoli delusion involves the belief that several different people are the same person in disguise. Intermetamorphosis is the belief that an individual has been transformed internally and externally to another person. Subjective doubles is the belief that a doppelganger of the afflicted person exists, living and functioning independently in the world. Reduplicative paramnesia is the belief that a person, place, or object has been duplicated. A rarer example of DMS is the Cotard delusion, which is the belief that the patient himself or herself is dead, putrefying, exsanguinating, or lacking internal organs.

The most common of the DMS is the Capgras delusion. One common presentation of Capgras delusion involves the spouse of the patient, who believes that an imposter of the same sex as their spouse has taken over his or her body. Rarer delusions are those in which a person misidentifies him or herself as the imposter.3,5,6

Case Presentation

This case involved a 24-year-old male veteran who had received a wide range of mental health diagnoses in the past, including major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, generalized anxiety disorder, cannabis use disorder, adjustment disorder, and borderline personality disorder. He also had a medical history related to a motor vehicle accident with subsequent intestinal rupture and colostomy placement that had occurred a year and a half prior to presentation. He had no history of brain trauma.

The patient voluntarily presented to the hospital for increased suicidal thoughts and was admitted voluntarily for stabilization and self-harm prevention. He stated that “I feel everything is unreal. I feel suicidal and guilt” and endorsed a plan to either walk into traffic or shoot himself in the head due to increasingly distressing thoughts and memories. According to the patient, he had reported to the police that he raped his ex-girlfriend a year previously, although she denied the claim to the police.

The patient further disclosed that he did not believe his mother was real. “Last year my sister told me it was not 2016, but it was 2022,” he said. “She told me that I have hurt my mother with a padlock—that you could no longer identify her face. I don’t remember having done this. I have lived with her since that time, so I don’t think it’s really [my mother].” He believed that his mother was replaced by “government employees” who were sent to elicit confessions for his behavior while in the military. He expressed guilt over several actions he had performed while in military service, such as punching a wall during boot camp, stealing “soak-up” pads, and napping during work hours. His mother was contacted by a staff psychiatrist in the inpatient unit and denied that any assault had taken place.

The patient’s psychiatric review of systems was positive for visual hallucinations (specifically “blurs” next to his bed in the morning that disappeared as he tried to touch them), depressed mood, anxiety, hopelessness, and insomnia. Pertinent negatives of the review of systems included a denial of manic symptoms and auditory hallucinations. For additional details of his past psychiatric history, the patient admitted that his motor vehicle accident, intestinal rupture, and colostomy were the result of his 1 suicide attempt a year and a half prior after a verbal dispute with the same ex-girlfriend that he believed he had raped. After undergoing extensive medical and surgical treatment, he began seeing an outpatient psychiatrist as well as attending substance use counseling to curtail his marijuana use. He was prescribed a combination of duloxetine and risperidone as an outpatient, which he was taking with intermittent adherence.

Regarding substance use, the patient admitted to using marijuana regularly in the past but quit completely 1 month prior and denied any other drug use or alcohol use. He reported a family history of a sister who was undergoing treatment for bipolar disorder. In his social history, the patient disclosed that he was raised by both parents and described a good childhood with a life absent of abuse in any form. He was single with no children. Although he was unemployed, he lived off the funds from an insurance settlement from his motor vehicle accident. He was living in a trailer with his brother and mother. He also denied having access to firearms.

The patient was overweight, neatly groomed, had good eye contact, and was calm and cooperative. He seemed anxious as evidenced by his continuous shaking of his feet; although speech was normal in rate and tone. He reported his mood as “depressed and anxious” with congruent and tearful affect. His thought process was concrete, although his thought content contained delusions, suicidal ideation, and paranoia. He denied any homicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming others. He did not present with any auditory or visual hallucinations. Insight and judgment were poor. The mental status examination revealed no notable deficits in cognition.

The patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophreniform disorder, exacerbation of MDD with psychotic features, and the psychotic component of cannabis use disorder. His outpatient risperidone and duloxetine were not restarted. Aripiprazole 15 mg daily was prescribed for his delusions, paranoia, and visual hallucinations. The patient also received a prescription for hydroxyzine 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for anxiety.

Because of the nature of his delusions, comorbid medical and neurologic conditions were considered. Neurology consultation recommended a noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scan and an electroencephalogram (EEG). Laboratory workup included HIV antibody, thyroid panel, chemistry panel, complete blood count, hepatitis B serum antigen, urine drug screen, hepatitis C virus, and rapid plasma reagin. All laboratory results were benign and unremarkable, and the urine drug screen was negative. The noncontrast CT revealed no acute findings, and the EEG revealed no recorded epileptiform abnormalities or seizures.

Throughout his hospital course, the patient remained cooperative with treatment. Three days into the hospitalization, he stated that he believed the entire family had been replaced by imposters. He began to distrust members of his family and was reticent to communicate with them when they attempted to contact him. He also experienced fragmented sleep during his hospital stay, and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime was added.

After aripiprazole was increased to 20 mg daily on hospital day 2 and then to 30 mg daily on hospital day 3 due to the patient’s delusions, he began to doubt the validity of his beliefs. After showing gradual improvement over 6 days, the patient reported that he no longer believed that those memories were real. His sleep, depressed mood, anxiety, and paranoia had markedly improved toward the end of the hospitalization and suicidal ideation/intent resolved. The patient was discharged home to his mother and brother after 6 days of hospitalization with aripiprazole 30 mg daily and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime.

Discussion

The Capgras delusion can present in several different contexts. A psychiatric differential diagnosis includes disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum (brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and substance-induced psychotic disorder. In addition to psychiatric disorders, the Capgras delusion has been shown to occur in several medical conditions, which include stroke, central nervous system tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, and dementia.1,2,4,7

A 2007 retrospective study by Josephs examined 47 patients diagnosed with the Capgras delusion from several tertiary care centers. Of those patients, 38 (81%) had a neurodegenerative disease, most commonly Lewy body dementia (LBD).1 In his review of the Josephs study, Devinsky proposed that the loss of striatal D2 receptors in LBD may be implicated in the manifestation of Capgras delusions.2 The data suggest multiple brain regions may be involved, including the frontal lobes, right temporal lobe, right parietal lobe, parahippocampus, and amygdala.1,2 Most patients in the Josephs study demonstrated global atrophy on imaging studies. One hypothesis is that it is the disconnection of the frontal lobe to other brain regions that may be implicated.1,2,4 This results in intact recognition of facial features of familiar people, impaired emotional recognition, and impaired self-correction due to executive dysfunction.

Methamphetamine also has been implicated in a small number of cases of Capgras; the proposed mechanism involves dopaminergic neuronal impairment/loss.1,2 Additionally, Capgras delusions have been described in cases of patients treated with antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine.8 Younger patients with the Capgras delusion were more likely to have purely psychiatric comorbidities—such as schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder—as opposed to underlying medical conditions.1 In the case presented here, the Capgras delusion was thought to be due to a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, specifically schizophreniform disorder.

Because an increasing amount of evidence indicates that the Capgras delusion is associated with certain medical conditions, a workup should be performed to rule out underlying medical etiology. Of note, no official guidelines for the workup have been produced for the Capgras delusion. However, the workup may include brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging and/or CT scan to rule out mass lesions, vascular malformations, stroke, or neuro-infectious processes; laboratory tests, such as vitamin B12, liver panel, HIV, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis B and C viruses, parathyroid hormone levels, urine drug screen, and thyroid panel can be ordered to rule out other medical causes.1,2,6,7,9

Consultations with internal medicine and neurology departments may be beneficial. Although treatment of the underlying condition may lead to an improvement in the symptoms, full remission in all cases has not been consistently demonstrated in the current literature.5,7,9,10 Patients with the Capgras delusion are challenging to treat, because their delusions have been shown to be refractory to antipsychotic therapy. However, antipsychotics are currently the mainstay of treatment. Some case studies have shown efficacy with pimozide, tricyclic antidepressants, and mirtazapine.6,9

One case study in 2014 in India of a 45-year-old woman who believed her husband and son were replaced by imposters out to kill her, showed a 40% to 50% reduction of paranoia, irritability, and suspicious scanning behaviors with a combination of risperidone and trihexyphenidyl. Despite the improvements, the woman continued to have delusions.7

A notable feature associated with those experiencing the Capgras delusion is the increased risk of violent behaviors, often because of suspiciousness and paranoia. A 2004 review suggested the risk of violence and homicidality is much higher in male patients compared with that of female patients with the Capgras delusion.9 This is despite evidence suggesting that the prevalence of the Capgras delusion seems to be greater in women.6,9 Moreover, patients often demonstrated social withdrawal and self-isolation prior to violent acts. The victims often were family members or those who live with the patient, which is consistent with the evidence that those most familiar to patients are more likely to be misidentified.1,2,7,9,10

A 1989 case series that examined 8 cases of the Capgras delusion listed the following violent behaviors: shot and killed father, pointed knife at mother, held knife to mother’s throat, punched parents, threatened to stab husband with scissors, nonspecifically threatened physical harm to family, injured mother with axe, and threatened to stab son with knife and burn him. Seven of the 8 patients lived with the misidentified persons, and 5 of the 8 patients were treatment resistant. The study posited that chronicity of the delusion, content of the delusion, and accessibility of misidentified persons seemed to increase the risk of violent behaviors. These authors went on to suggest that despite the appearance of stability, patients may react violently to minute changes.10 Overall literature seems to suggest the importance of performing a violence and homicidality assessment with special attention to assessment for themes of hostility toward misidentified individuals.9,10

Conclusion

The Capgras delusion is an uncommon symptom associated with varied psychiatric, medical, iatrogenic, and neurologic conditions. Treatment of underlying medical conditions may improve or resolve the delusions. However, in this case, the patient did not seem to have any underlying medical conditions, and it was thought that he may have been experiencing a prodrome within the schizophrenia spectrum. This is consistent with the literature, which suggests that those with the delusions at younger ages may have a psychiatric etiology.

Although this patient was responsive to aripiprazole, the Capgras delusion has been known to be resistant to antipsychotic therapy. It is worth considering a medical and neurologic workup with the addition of a psychiatry referral. Further, while the patient in the presented case had the delusion that he had assaulted his mother, whom he misidentified as an imposter, the patient did not demonstrate any hostility and denied thoughts of harming her. However, given the increased risk of violence in patients with the Capgras delusion, a homicidality and violence assessment should be performed. While further recommendations are outside the scope of this article, the provider should be cognizant of local duty-to-warn and duty-to-protect laws regarding potentially homicidal patients.

1. Josephs KA. The Capgras delusion and its relationship to neurodegenerative disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1762-1766.

2. Devinsky O. Behavioral neurology. The neurology of the Capgras delusion. Rev Neurol Dis. 2008;5(2):97-100.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2007.

4. Tamam L, Karatas G, Zeren T, Ozpyraz N. The prevalence of Capgras syndrome in a university hospital setting. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15(5):290-295.

5. Klein CA, Hirchan S. The masks of identities: who’s who? Delusional misidentification syndromes. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(3):369-378.

6. Atta K. Forlenza N, Gujski M, Hashmi S, Isaac G. Delusional misidentification syndromes: separate disorders or unusual presentations of existing DSM-IV categories? Psychiatry (Edgemont). 2006;3(9):56-61.

7. Sathe H, Karia S, De Sousa A, Shah N. Capgras syndrome: a case report. Paripex Indian J Res. 2014;3(8):134-135. 8. Bhatia MS, Singhal PK, Agrawal P, Malik SC. Capgras’ syndrome in chloroquine induced psychosis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30(3):311-313.

9. Bourget D, Whitehurst L. Capgras syndrome: a review of the neurophysiological correlates and presenting clinical features in cases involving physical violence. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):719-725.

10. Silva JA, Leong GB, Weinstock R, Boyer CL. Capgras syndrome and dangerousness. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1989;17(1):5-14.

Many patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals present with delusions; however, the Capgras delusion is a rare type that often appears as a sequela of certain medical and neurologic conditions.1 The Capgras delusion is a condition in which a person believes that either an individual or a group of people has been replaced by doubles or imposters.

In 1923, French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras first described the delusion. He and Jean Reboul-Lachaux coauthored a paper on a 53-year-old woman. The patient was a paranoid megalomaniac who “transformed everyone in her entourage, even those closest to her, such as her husband and daughter, into various and numerous doubles.”2 She believed she was famous, wealthy, and of royal lineage. Although 3 of her children had died, she believed that they were abducted, and that her only surviving child was replaced by a look-alike.2,3 Although the prevalence of such delusions in the general population has not been fully studied, a psychiatric hospital in Turkey found a 1.3% prevalence (1.8% women and 0.9% men) in 920 admissions over 5 years.4

The Capgras delusion is one of many delusions related to the misidentification of people, places, or objects; these delusions collectively are known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS).5,6 The Fregoli delusion involves the belief that several different people are the same person in disguise. Intermetamorphosis is the belief that an individual has been transformed internally and externally to another person. Subjective doubles is the belief that a doppelganger of the afflicted person exists, living and functioning independently in the world. Reduplicative paramnesia is the belief that a person, place, or object has been duplicated. A rarer example of DMS is the Cotard delusion, which is the belief that the patient himself or herself is dead, putrefying, exsanguinating, or lacking internal organs.

The most common of the DMS is the Capgras delusion. One common presentation of Capgras delusion involves the spouse of the patient, who believes that an imposter of the same sex as their spouse has taken over his or her body. Rarer delusions are those in which a person misidentifies him or herself as the imposter.3,5,6

Case Presentation

This case involved a 24-year-old male veteran who had received a wide range of mental health diagnoses in the past, including major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, generalized anxiety disorder, cannabis use disorder, adjustment disorder, and borderline personality disorder. He also had a medical history related to a motor vehicle accident with subsequent intestinal rupture and colostomy placement that had occurred a year and a half prior to presentation. He had no history of brain trauma.

The patient voluntarily presented to the hospital for increased suicidal thoughts and was admitted voluntarily for stabilization and self-harm prevention. He stated that “I feel everything is unreal. I feel suicidal and guilt” and endorsed a plan to either walk into traffic or shoot himself in the head due to increasingly distressing thoughts and memories. According to the patient, he had reported to the police that he raped his ex-girlfriend a year previously, although she denied the claim to the police.

The patient further disclosed that he did not believe his mother was real. “Last year my sister told me it was not 2016, but it was 2022,” he said. “She told me that I have hurt my mother with a padlock—that you could no longer identify her face. I don’t remember having done this. I have lived with her since that time, so I don’t think it’s really [my mother].” He believed that his mother was replaced by “government employees” who were sent to elicit confessions for his behavior while in the military. He expressed guilt over several actions he had performed while in military service, such as punching a wall during boot camp, stealing “soak-up” pads, and napping during work hours. His mother was contacted by a staff psychiatrist in the inpatient unit and denied that any assault had taken place.

The patient’s psychiatric review of systems was positive for visual hallucinations (specifically “blurs” next to his bed in the morning that disappeared as he tried to touch them), depressed mood, anxiety, hopelessness, and insomnia. Pertinent negatives of the review of systems included a denial of manic symptoms and auditory hallucinations. For additional details of his past psychiatric history, the patient admitted that his motor vehicle accident, intestinal rupture, and colostomy were the result of his 1 suicide attempt a year and a half prior after a verbal dispute with the same ex-girlfriend that he believed he had raped. After undergoing extensive medical and surgical treatment, he began seeing an outpatient psychiatrist as well as attending substance use counseling to curtail his marijuana use. He was prescribed a combination of duloxetine and risperidone as an outpatient, which he was taking with intermittent adherence.

Regarding substance use, the patient admitted to using marijuana regularly in the past but quit completely 1 month prior and denied any other drug use or alcohol use. He reported a family history of a sister who was undergoing treatment for bipolar disorder. In his social history, the patient disclosed that he was raised by both parents and described a good childhood with a life absent of abuse in any form. He was single with no children. Although he was unemployed, he lived off the funds from an insurance settlement from his motor vehicle accident. He was living in a trailer with his brother and mother. He also denied having access to firearms.

The patient was overweight, neatly groomed, had good eye contact, and was calm and cooperative. He seemed anxious as evidenced by his continuous shaking of his feet; although speech was normal in rate and tone. He reported his mood as “depressed and anxious” with congruent and tearful affect. His thought process was concrete, although his thought content contained delusions, suicidal ideation, and paranoia. He denied any homicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming others. He did not present with any auditory or visual hallucinations. Insight and judgment were poor. The mental status examination revealed no notable deficits in cognition.

The patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophreniform disorder, exacerbation of MDD with psychotic features, and the psychotic component of cannabis use disorder. His outpatient risperidone and duloxetine were not restarted. Aripiprazole 15 mg daily was prescribed for his delusions, paranoia, and visual hallucinations. The patient also received a prescription for hydroxyzine 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for anxiety.

Because of the nature of his delusions, comorbid medical and neurologic conditions were considered. Neurology consultation recommended a noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scan and an electroencephalogram (EEG). Laboratory workup included HIV antibody, thyroid panel, chemistry panel, complete blood count, hepatitis B serum antigen, urine drug screen, hepatitis C virus, and rapid plasma reagin. All laboratory results were benign and unremarkable, and the urine drug screen was negative. The noncontrast CT revealed no acute findings, and the EEG revealed no recorded epileptiform abnormalities or seizures.

Throughout his hospital course, the patient remained cooperative with treatment. Three days into the hospitalization, he stated that he believed the entire family had been replaced by imposters. He began to distrust members of his family and was reticent to communicate with them when they attempted to contact him. He also experienced fragmented sleep during his hospital stay, and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime was added.

After aripiprazole was increased to 20 mg daily on hospital day 2 and then to 30 mg daily on hospital day 3 due to the patient’s delusions, he began to doubt the validity of his beliefs. After showing gradual improvement over 6 days, the patient reported that he no longer believed that those memories were real. His sleep, depressed mood, anxiety, and paranoia had markedly improved toward the end of the hospitalization and suicidal ideation/intent resolved. The patient was discharged home to his mother and brother after 6 days of hospitalization with aripiprazole 30 mg daily and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime.

Discussion

The Capgras delusion can present in several different contexts. A psychiatric differential diagnosis includes disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum (brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and substance-induced psychotic disorder. In addition to psychiatric disorders, the Capgras delusion has been shown to occur in several medical conditions, which include stroke, central nervous system tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, and dementia.1,2,4,7

A 2007 retrospective study by Josephs examined 47 patients diagnosed with the Capgras delusion from several tertiary care centers. Of those patients, 38 (81%) had a neurodegenerative disease, most commonly Lewy body dementia (LBD).1 In his review of the Josephs study, Devinsky proposed that the loss of striatal D2 receptors in LBD may be implicated in the manifestation of Capgras delusions.2 The data suggest multiple brain regions may be involved, including the frontal lobes, right temporal lobe, right parietal lobe, parahippocampus, and amygdala.1,2 Most patients in the Josephs study demonstrated global atrophy on imaging studies. One hypothesis is that it is the disconnection of the frontal lobe to other brain regions that may be implicated.1,2,4 This results in intact recognition of facial features of familiar people, impaired emotional recognition, and impaired self-correction due to executive dysfunction.

Methamphetamine also has been implicated in a small number of cases of Capgras; the proposed mechanism involves dopaminergic neuronal impairment/loss.1,2 Additionally, Capgras delusions have been described in cases of patients treated with antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine.8 Younger patients with the Capgras delusion were more likely to have purely psychiatric comorbidities—such as schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder—as opposed to underlying medical conditions.1 In the case presented here, the Capgras delusion was thought to be due to a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, specifically schizophreniform disorder.

Because an increasing amount of evidence indicates that the Capgras delusion is associated with certain medical conditions, a workup should be performed to rule out underlying medical etiology. Of note, no official guidelines for the workup have been produced for the Capgras delusion. However, the workup may include brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging and/or CT scan to rule out mass lesions, vascular malformations, stroke, or neuro-infectious processes; laboratory tests, such as vitamin B12, liver panel, HIV, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis B and C viruses, parathyroid hormone levels, urine drug screen, and thyroid panel can be ordered to rule out other medical causes.1,2,6,7,9

Consultations with internal medicine and neurology departments may be beneficial. Although treatment of the underlying condition may lead to an improvement in the symptoms, full remission in all cases has not been consistently demonstrated in the current literature.5,7,9,10 Patients with the Capgras delusion are challenging to treat, because their delusions have been shown to be refractory to antipsychotic therapy. However, antipsychotics are currently the mainstay of treatment. Some case studies have shown efficacy with pimozide, tricyclic antidepressants, and mirtazapine.6,9

One case study in 2014 in India of a 45-year-old woman who believed her husband and son were replaced by imposters out to kill her, showed a 40% to 50% reduction of paranoia, irritability, and suspicious scanning behaviors with a combination of risperidone and trihexyphenidyl. Despite the improvements, the woman continued to have delusions.7

A notable feature associated with those experiencing the Capgras delusion is the increased risk of violent behaviors, often because of suspiciousness and paranoia. A 2004 review suggested the risk of violence and homicidality is much higher in male patients compared with that of female patients with the Capgras delusion.9 This is despite evidence suggesting that the prevalence of the Capgras delusion seems to be greater in women.6,9 Moreover, patients often demonstrated social withdrawal and self-isolation prior to violent acts. The victims often were family members or those who live with the patient, which is consistent with the evidence that those most familiar to patients are more likely to be misidentified.1,2,7,9,10

A 1989 case series that examined 8 cases of the Capgras delusion listed the following violent behaviors: shot and killed father, pointed knife at mother, held knife to mother’s throat, punched parents, threatened to stab husband with scissors, nonspecifically threatened physical harm to family, injured mother with axe, and threatened to stab son with knife and burn him. Seven of the 8 patients lived with the misidentified persons, and 5 of the 8 patients were treatment resistant. The study posited that chronicity of the delusion, content of the delusion, and accessibility of misidentified persons seemed to increase the risk of violent behaviors. These authors went on to suggest that despite the appearance of stability, patients may react violently to minute changes.10 Overall literature seems to suggest the importance of performing a violence and homicidality assessment with special attention to assessment for themes of hostility toward misidentified individuals.9,10

Conclusion

The Capgras delusion is an uncommon symptom associated with varied psychiatric, medical, iatrogenic, and neurologic conditions. Treatment of underlying medical conditions may improve or resolve the delusions. However, in this case, the patient did not seem to have any underlying medical conditions, and it was thought that he may have been experiencing a prodrome within the schizophrenia spectrum. This is consistent with the literature, which suggests that those with the delusions at younger ages may have a psychiatric etiology.

Although this patient was responsive to aripiprazole, the Capgras delusion has been known to be resistant to antipsychotic therapy. It is worth considering a medical and neurologic workup with the addition of a psychiatry referral. Further, while the patient in the presented case had the delusion that he had assaulted his mother, whom he misidentified as an imposter, the patient did not demonstrate any hostility and denied thoughts of harming her. However, given the increased risk of violence in patients with the Capgras delusion, a homicidality and violence assessment should be performed. While further recommendations are outside the scope of this article, the provider should be cognizant of local duty-to-warn and duty-to-protect laws regarding potentially homicidal patients.

Many patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals present with delusions; however, the Capgras delusion is a rare type that often appears as a sequela of certain medical and neurologic conditions.1 The Capgras delusion is a condition in which a person believes that either an individual or a group of people has been replaced by doubles or imposters.

In 1923, French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras first described the delusion. He and Jean Reboul-Lachaux coauthored a paper on a 53-year-old woman. The patient was a paranoid megalomaniac who “transformed everyone in her entourage, even those closest to her, such as her husband and daughter, into various and numerous doubles.”2 She believed she was famous, wealthy, and of royal lineage. Although 3 of her children had died, she believed that they were abducted, and that her only surviving child was replaced by a look-alike.2,3 Although the prevalence of such delusions in the general population has not been fully studied, a psychiatric hospital in Turkey found a 1.3% prevalence (1.8% women and 0.9% men) in 920 admissions over 5 years.4

The Capgras delusion is one of many delusions related to the misidentification of people, places, or objects; these delusions collectively are known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS).5,6 The Fregoli delusion involves the belief that several different people are the same person in disguise. Intermetamorphosis is the belief that an individual has been transformed internally and externally to another person. Subjective doubles is the belief that a doppelganger of the afflicted person exists, living and functioning independently in the world. Reduplicative paramnesia is the belief that a person, place, or object has been duplicated. A rarer example of DMS is the Cotard delusion, which is the belief that the patient himself or herself is dead, putrefying, exsanguinating, or lacking internal organs.

The most common of the DMS is the Capgras delusion. One common presentation of Capgras delusion involves the spouse of the patient, who believes that an imposter of the same sex as their spouse has taken over his or her body. Rarer delusions are those in which a person misidentifies him or herself as the imposter.3,5,6

Case Presentation

This case involved a 24-year-old male veteran who had received a wide range of mental health diagnoses in the past, including major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, generalized anxiety disorder, cannabis use disorder, adjustment disorder, and borderline personality disorder. He also had a medical history related to a motor vehicle accident with subsequent intestinal rupture and colostomy placement that had occurred a year and a half prior to presentation. He had no history of brain trauma.

The patient voluntarily presented to the hospital for increased suicidal thoughts and was admitted voluntarily for stabilization and self-harm prevention. He stated that “I feel everything is unreal. I feel suicidal and guilt” and endorsed a plan to either walk into traffic or shoot himself in the head due to increasingly distressing thoughts and memories. According to the patient, he had reported to the police that he raped his ex-girlfriend a year previously, although she denied the claim to the police.

The patient further disclosed that he did not believe his mother was real. “Last year my sister told me it was not 2016, but it was 2022,” he said. “She told me that I have hurt my mother with a padlock—that you could no longer identify her face. I don’t remember having done this. I have lived with her since that time, so I don’t think it’s really [my mother].” He believed that his mother was replaced by “government employees” who were sent to elicit confessions for his behavior while in the military. He expressed guilt over several actions he had performed while in military service, such as punching a wall during boot camp, stealing “soak-up” pads, and napping during work hours. His mother was contacted by a staff psychiatrist in the inpatient unit and denied that any assault had taken place.

The patient’s psychiatric review of systems was positive for visual hallucinations (specifically “blurs” next to his bed in the morning that disappeared as he tried to touch them), depressed mood, anxiety, hopelessness, and insomnia. Pertinent negatives of the review of systems included a denial of manic symptoms and auditory hallucinations. For additional details of his past psychiatric history, the patient admitted that his motor vehicle accident, intestinal rupture, and colostomy were the result of his 1 suicide attempt a year and a half prior after a verbal dispute with the same ex-girlfriend that he believed he had raped. After undergoing extensive medical and surgical treatment, he began seeing an outpatient psychiatrist as well as attending substance use counseling to curtail his marijuana use. He was prescribed a combination of duloxetine and risperidone as an outpatient, which he was taking with intermittent adherence.

Regarding substance use, the patient admitted to using marijuana regularly in the past but quit completely 1 month prior and denied any other drug use or alcohol use. He reported a family history of a sister who was undergoing treatment for bipolar disorder. In his social history, the patient disclosed that he was raised by both parents and described a good childhood with a life absent of abuse in any form. He was single with no children. Although he was unemployed, he lived off the funds from an insurance settlement from his motor vehicle accident. He was living in a trailer with his brother and mother. He also denied having access to firearms.

The patient was overweight, neatly groomed, had good eye contact, and was calm and cooperative. He seemed anxious as evidenced by his continuous shaking of his feet; although speech was normal in rate and tone. He reported his mood as “depressed and anxious” with congruent and tearful affect. His thought process was concrete, although his thought content contained delusions, suicidal ideation, and paranoia. He denied any homicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming others. He did not present with any auditory or visual hallucinations. Insight and judgment were poor. The mental status examination revealed no notable deficits in cognition.

The patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophreniform disorder, exacerbation of MDD with psychotic features, and the psychotic component of cannabis use disorder. His outpatient risperidone and duloxetine were not restarted. Aripiprazole 15 mg daily was prescribed for his delusions, paranoia, and visual hallucinations. The patient also received a prescription for hydroxyzine 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for anxiety.

Because of the nature of his delusions, comorbid medical and neurologic conditions were considered. Neurology consultation recommended a noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scan and an electroencephalogram (EEG). Laboratory workup included HIV antibody, thyroid panel, chemistry panel, complete blood count, hepatitis B serum antigen, urine drug screen, hepatitis C virus, and rapid plasma reagin. All laboratory results were benign and unremarkable, and the urine drug screen was negative. The noncontrast CT revealed no acute findings, and the EEG revealed no recorded epileptiform abnormalities or seizures.

Throughout his hospital course, the patient remained cooperative with treatment. Three days into the hospitalization, he stated that he believed the entire family had been replaced by imposters. He began to distrust members of his family and was reticent to communicate with them when they attempted to contact him. He also experienced fragmented sleep during his hospital stay, and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime was added.

After aripiprazole was increased to 20 mg daily on hospital day 2 and then to 30 mg daily on hospital day 3 due to the patient’s delusions, he began to doubt the validity of his beliefs. After showing gradual improvement over 6 days, the patient reported that he no longer believed that those memories were real. His sleep, depressed mood, anxiety, and paranoia had markedly improved toward the end of the hospitalization and suicidal ideation/intent resolved. The patient was discharged home to his mother and brother after 6 days of hospitalization with aripiprazole 30 mg daily and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime.

Discussion

The Capgras delusion can present in several different contexts. A psychiatric differential diagnosis includes disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum (brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and substance-induced psychotic disorder. In addition to psychiatric disorders, the Capgras delusion has been shown to occur in several medical conditions, which include stroke, central nervous system tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, and dementia.1,2,4,7

A 2007 retrospective study by Josephs examined 47 patients diagnosed with the Capgras delusion from several tertiary care centers. Of those patients, 38 (81%) had a neurodegenerative disease, most commonly Lewy body dementia (LBD).1 In his review of the Josephs study, Devinsky proposed that the loss of striatal D2 receptors in LBD may be implicated in the manifestation of Capgras delusions.2 The data suggest multiple brain regions may be involved, including the frontal lobes, right temporal lobe, right parietal lobe, parahippocampus, and amygdala.1,2 Most patients in the Josephs study demonstrated global atrophy on imaging studies. One hypothesis is that it is the disconnection of the frontal lobe to other brain regions that may be implicated.1,2,4 This results in intact recognition of facial features of familiar people, impaired emotional recognition, and impaired self-correction due to executive dysfunction.

Methamphetamine also has been implicated in a small number of cases of Capgras; the proposed mechanism involves dopaminergic neuronal impairment/loss.1,2 Additionally, Capgras delusions have been described in cases of patients treated with antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine.8 Younger patients with the Capgras delusion were more likely to have purely psychiatric comorbidities—such as schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder—as opposed to underlying medical conditions.1 In the case presented here, the Capgras delusion was thought to be due to a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, specifically schizophreniform disorder.

Because an increasing amount of evidence indicates that the Capgras delusion is associated with certain medical conditions, a workup should be performed to rule out underlying medical etiology. Of note, no official guidelines for the workup have been produced for the Capgras delusion. However, the workup may include brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging and/or CT scan to rule out mass lesions, vascular malformations, stroke, or neuro-infectious processes; laboratory tests, such as vitamin B12, liver panel, HIV, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis B and C viruses, parathyroid hormone levels, urine drug screen, and thyroid panel can be ordered to rule out other medical causes.1,2,6,7,9

Consultations with internal medicine and neurology departments may be beneficial. Although treatment of the underlying condition may lead to an improvement in the symptoms, full remission in all cases has not been consistently demonstrated in the current literature.5,7,9,10 Patients with the Capgras delusion are challenging to treat, because their delusions have been shown to be refractory to antipsychotic therapy. However, antipsychotics are currently the mainstay of treatment. Some case studies have shown efficacy with pimozide, tricyclic antidepressants, and mirtazapine.6,9

One case study in 2014 in India of a 45-year-old woman who believed her husband and son were replaced by imposters out to kill her, showed a 40% to 50% reduction of paranoia, irritability, and suspicious scanning behaviors with a combination of risperidone and trihexyphenidyl. Despite the improvements, the woman continued to have delusions.7

A notable feature associated with those experiencing the Capgras delusion is the increased risk of violent behaviors, often because of suspiciousness and paranoia. A 2004 review suggested the risk of violence and homicidality is much higher in male patients compared with that of female patients with the Capgras delusion.9 This is despite evidence suggesting that the prevalence of the Capgras delusion seems to be greater in women.6,9 Moreover, patients often demonstrated social withdrawal and self-isolation prior to violent acts. The victims often were family members or those who live with the patient, which is consistent with the evidence that those most familiar to patients are more likely to be misidentified.1,2,7,9,10

A 1989 case series that examined 8 cases of the Capgras delusion listed the following violent behaviors: shot and killed father, pointed knife at mother, held knife to mother’s throat, punched parents, threatened to stab husband with scissors, nonspecifically threatened physical harm to family, injured mother with axe, and threatened to stab son with knife and burn him. Seven of the 8 patients lived with the misidentified persons, and 5 of the 8 patients were treatment resistant. The study posited that chronicity of the delusion, content of the delusion, and accessibility of misidentified persons seemed to increase the risk of violent behaviors. These authors went on to suggest that despite the appearance of stability, patients may react violently to minute changes.10 Overall literature seems to suggest the importance of performing a violence and homicidality assessment with special attention to assessment for themes of hostility toward misidentified individuals.9,10

Conclusion

The Capgras delusion is an uncommon symptom associated with varied psychiatric, medical, iatrogenic, and neurologic conditions. Treatment of underlying medical conditions may improve or resolve the delusions. However, in this case, the patient did not seem to have any underlying medical conditions, and it was thought that he may have been experiencing a prodrome within the schizophrenia spectrum. This is consistent with the literature, which suggests that those with the delusions at younger ages may have a psychiatric etiology.

Although this patient was responsive to aripiprazole, the Capgras delusion has been known to be resistant to antipsychotic therapy. It is worth considering a medical and neurologic workup with the addition of a psychiatry referral. Further, while the patient in the presented case had the delusion that he had assaulted his mother, whom he misidentified as an imposter, the patient did not demonstrate any hostility and denied thoughts of harming her. However, given the increased risk of violence in patients with the Capgras delusion, a homicidality and violence assessment should be performed. While further recommendations are outside the scope of this article, the provider should be cognizant of local duty-to-warn and duty-to-protect laws regarding potentially homicidal patients.

1. Josephs KA. The Capgras delusion and its relationship to neurodegenerative disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1762-1766.

2. Devinsky O. Behavioral neurology. The neurology of the Capgras delusion. Rev Neurol Dis. 2008;5(2):97-100.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2007.

4. Tamam L, Karatas G, Zeren T, Ozpyraz N. The prevalence of Capgras syndrome in a university hospital setting. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15(5):290-295.

5. Klein CA, Hirchan S. The masks of identities: who’s who? Delusional misidentification syndromes. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(3):369-378.

6. Atta K. Forlenza N, Gujski M, Hashmi S, Isaac G. Delusional misidentification syndromes: separate disorders or unusual presentations of existing DSM-IV categories? Psychiatry (Edgemont). 2006;3(9):56-61.

7. Sathe H, Karia S, De Sousa A, Shah N. Capgras syndrome: a case report. Paripex Indian J Res. 2014;3(8):134-135. 8. Bhatia MS, Singhal PK, Agrawal P, Malik SC. Capgras’ syndrome in chloroquine induced psychosis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30(3):311-313.

9. Bourget D, Whitehurst L. Capgras syndrome: a review of the neurophysiological correlates and presenting clinical features in cases involving physical violence. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):719-725.

10. Silva JA, Leong GB, Weinstock R, Boyer CL. Capgras syndrome and dangerousness. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1989;17(1):5-14.

1. Josephs KA. The Capgras delusion and its relationship to neurodegenerative disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1762-1766.

2. Devinsky O. Behavioral neurology. The neurology of the Capgras delusion. Rev Neurol Dis. 2008;5(2):97-100.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2007.

4. Tamam L, Karatas G, Zeren T, Ozpyraz N. The prevalence of Capgras syndrome in a university hospital setting. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15(5):290-295.

5. Klein CA, Hirchan S. The masks of identities: who’s who? Delusional misidentification syndromes. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(3):369-378.

6. Atta K. Forlenza N, Gujski M, Hashmi S, Isaac G. Delusional misidentification syndromes: separate disorders or unusual presentations of existing DSM-IV categories? Psychiatry (Edgemont). 2006;3(9):56-61.

7. Sathe H, Karia S, De Sousa A, Shah N. Capgras syndrome: a case report. Paripex Indian J Res. 2014;3(8):134-135. 8. Bhatia MS, Singhal PK, Agrawal P, Malik SC. Capgras’ syndrome in chloroquine induced psychosis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30(3):311-313.

9. Bourget D, Whitehurst L. Capgras syndrome: a review of the neurophysiological correlates and presenting clinical features in cases involving physical violence. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):719-725.

10. Silva JA, Leong GB, Weinstock R, Boyer CL. Capgras syndrome and dangerousness. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1989;17(1):5-14.

Transformation of Benign Giant Cell Tumor of Bone Into Epithelioid Angiosarcoma

Take-Home Points

- Malignant transformation of a benign GCT is extremely rare.

- It is difficult to distinguish between an early malignant transformation and an overlooked malignancy.

- The most common clinical presentation of transformation of GCT into malignancy is pain, often with swelling.

- Interval monitoring of GCTs may be necessary in patients with symptoms concerning for malignant transformation.

- Clinicians should maintain a high clinical suspicion for malignant transformation or late recurrence of GCT in a patient with new pain at the wound site.

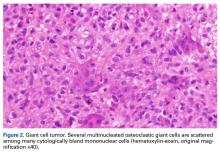

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of bone account for about 5% of all primary bone tumors in adults, with a predominance in the third decade in life.1 Clinically, GCT of bone often presents with pain, pathologic fracture, and/or soft- tissue expansion in the epiphysis of long bones. However, GCT of bone also has been reported in non-long bones, such as the talus and the calcaneus.2,3 Histologically, GCT of bone consists of neoplastic stromal cells, mononuclear histiocytic cells, and multinucleated giant cells that resemble osteoclasts.4 The radiologic appearance of GCT is often described as a lytic, eccentrically located bony lesion that extends near the articular surface in patients with closed physes. Many GCTs have aggressive radiologic features with possible extensive bony destruction and soft-tissue extension.

Although categorized as a benign lesion, GCT can be locally aggressive, with a variable local recurrence rate of 0% to 65%, depending on treatment modality and skeletal location. Given the aggressiveness of GCT of bone, recommendations for operative intervention include intralesional curettage with adjuvant therapy (eg, cryotherapy, phenol, argon beam, electrocautery) and placement of bone void fillers (eg, bone graft polymethylmethacrylate). Wide resection is recommended when the articular surface is no longer viable for reconstruction secondary to extensive destruction. Some authors have reported that surgical margin is the only risk factor in local recurrence,5,6 and thus complete resection may be needed for tumor eradication. In addition, about 3% of GCTs demonstrate benign pulmonary implants, which have been cited as cause of death in 16% to 25% of reported cases of pulmonary spread.7,8

The literature includes few reports of primary or secondary malignant transformation of GCT. Hutter and colleagues9 defined primary malignant GCT as GCT with sarcomatous tissue juxtaposed with zones of typical benign GCT cells. Secondary malignant GCT is a sarcomatous lesion at the site of a previously documented benign GCT. Secondary malignant GCT of bone histologically has been classified as a fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, or osteosarcoma transformation.10

Most malignant transformations of GCT of bone have been attributed to previous irradiation of the lesion.11,12 However, there are some case reports of benign bone GCT malignant transformation in situ without any other medical intervention. It was reported that non-radiation-induced secondary transformations occur relatively early after GCT treatment.13 During the early stages of tumor recurrence, however, it is difficult to distinguish between malignant transformation and primary disease overlooked as a result of sampling error.

We report a case of secondary malignant transformation of GCT of bone 11 years after surgical curettage, cryotherapy, and cementation without adjuvant radiation therapy. To our knowledge, this case report is the first to describe transformation of a nonirradiated benign GCT into an aggressive, high-grade epithelioid angiosarcoma, a very rare vascular bone tumor. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

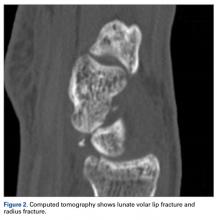

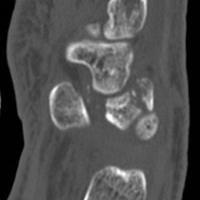

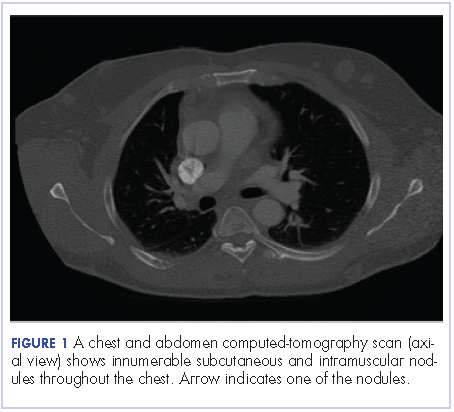

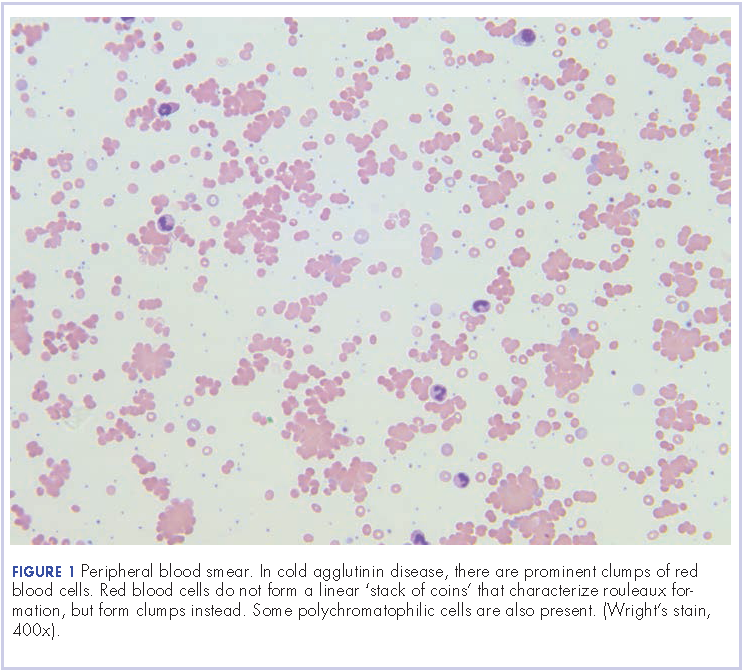

In July 2003, a 46-year-old woman presented with left heel pain of several months’ duration. Plain radiographs showed a nonaggressive-appearing lytic lesion of the superior aspect of the posterior calcaneal tuberosity with a small cortical incongruity along the superior margin of the lesion (Figures 1A-1D).

A postoperative splint was placed, and weight-bearing progressed over 6 weeks. The patient was followed at 2- to 3-month intervals over the first 5 postoperative years. She was able to work and perform activities of daily living, but her postoperative course was complicated by significant chronic pain in multiple extremities and long-term treatment by the chronic pain service. At no time did postoperative imaging—magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 6 years, whole-body bone scan at 7 years, plain radiographs at 10 years—show evidence of recurrence.

Radiographs showed stable postoperative changes with a small radiolucent area (with sclerotic rim) surrounding the cement-bone interface. Given its proximity to the Achilles tendon and more motion than usual at the wound site, the radiolucency likely was caused by small movements of the interface. The radiolucent area remained stable over a 15-month period.

Whole-body bone scan showed a small area of osteoblastic activity in the left calcaneus, consistent with inflammation surrounding the bone- cement interface, but the uptake was minor relative to other areas of signal, and there were no significant inflammatory reactive changes on MRI (Figures 3A, 3B).

Over 11 years, regular 6- to 12-month follow-up examinations revealed no significant changes in the left foot or in plain radiographs of the chest. In addition, physical examinations revealed no evidence of a palpable mass of the left foot.

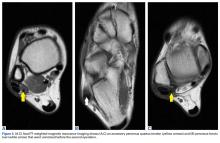

In July 2014 (11 years after curettage and cementation), the patient presented to her pain clinic appointment with severe left foot pain. She said that, over a few weeks, she experienced a significant increase in pain and developed posterolateral foot swelling, which limited her ability to ambulate. Plain radiographs showed a significant soft-tissue prominence around the posterior calcaneus, increased lucency around the bone-cement interface in the calcaneus with elevation, and a cortical break of the superior margin of the posterior calcaneus (Figures 3C, 3D). MRI showed a large lobular mass in the calcaneus and surrounding soft tissue with T1 and T2 signal heterogeneity and enhancement after administration of gadolinium (Figures 4A-4D). There was a large extraosseous extension of the calcaneus-based mass laterally and superiorly with edema in the surrounding hindfoot region (Figure 4).

Physical examination revealed exquisite tenderness along the lateral and posterior aspects of the left hindfoot. The patient was unable to bear weight and had soft-tissue swelling throughout the foot and mid calf as well as a palpable mass in the posterior heel. She was otherwise neurovascularly intact through all distributions of the left lower extremity. It was unclear if the GCT of the calcaneus had recurred or if there was a new, secondary tumor. Given her severe pain and morbidity, the patient decided to proceed with open biopsy and a pathology-pending plan for possible amputation in the near future.

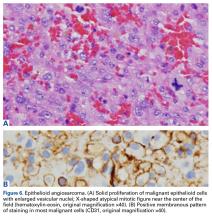

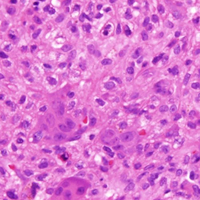

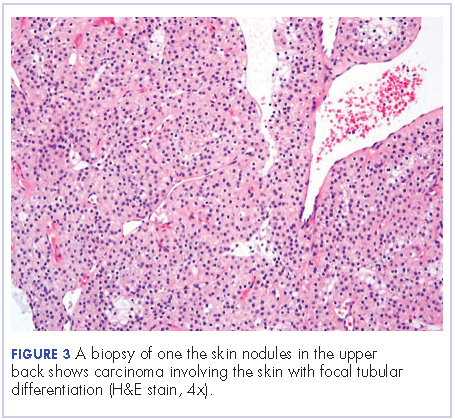

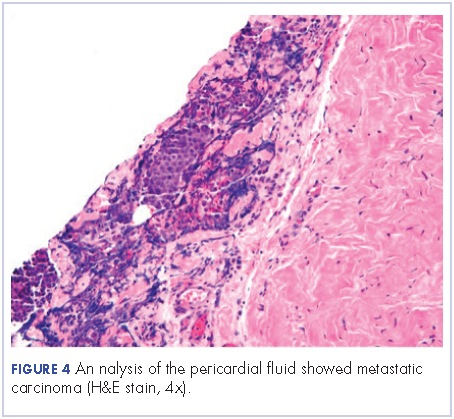

In August 2014, an open biopsy with intraoperative frozen evaluation yielded a diagnosis of malignant neoplasm not otherwise specified. Permanent sections showed a proliferation of malignant epithelioid cells with extensive necrosis, hemorrhage, and hemosiderin deposition but no multinucleated giant cells.

Transformation of the GCT into a high-grade epithelioid angiosarcoma prompted presentation of the patient’s case to a multidisciplinary board of physicians with a focused clinical practice in sarcoma management. The board included board-certified specialists in orthopedic oncology, pathology, musculoskeletal radiology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. Although discussion included pre-resection use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to evaluate for disease response, the patient’s severe pain led her to forgo this treatment and proceed directly to below-knee amputation.

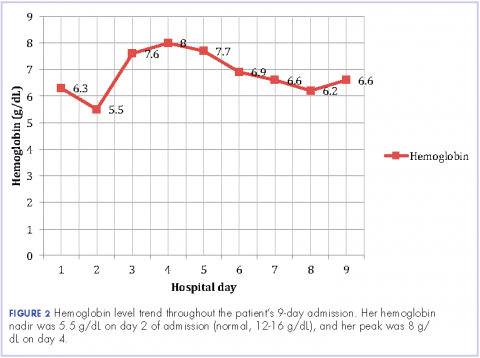

Amputation revealed a 7.7-cm hemorrhagic necrotic mass composed of a highly cellular spindle and epithelioid malignancy with abundant hemosiderin deposition (Figure 5). In addition, several atypical mitotic figures and malignant multinucleated tumor giant cells were randomly scattered throughout the neoplasm.

At first follow-up, the patient reported significant pain relief and asked to begin titrating off her chronic pain medicine. Clinical staging, which involved performing whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography, revealed nothing concerning for metastases. When this report was being written, the patient was being monitored for recurrent disease in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. In the absence of residual sarcoma, our medical oncology team discussed adjuvant chemotherapy options with her. Subsequently, however, she proceeded only with observation and periodic imaging.

Discussion

Malignant transformation of a benign GCT is extremely rare, especially in cases in which the tumor bed has not previously undergone radiation therapy. Although the literature includes historical case reports, primary and secondary malignant GCTs comprise <9% of all GCTs.11,13,14 Primary bone epithelioid angiosarcoma is also extremely rare, especially in the calcaneus; only 1 case is described in the literature.15 In this article, we report on a benign GCT of bone that transformed into an epithelioid angiosarcoma more than a decade after the GCT was treated with curettage and cementation.

The fact that the malignant areas of a previous tumor may have been missed because of sampling error is important for benign GCT of bone in the early postoperative period, as distinguishing between early malignant transformation and an overlooked malignancy may not be possible. However, transformation is more likely the case when a benign GCT becomes a high-grade malignancy after a long disease-free interval. Several authors have indicated that a benign GCT tumor recurring with a secondary malignancy 2 to 5 years after initial GCT treatment suggests malignant transformation.16 Grote and colleagues10 compiled reports of malignant transformation of GCT of bone and described the clinicopathologic features of secondary malignant transformation of GCTs. The data they compiled and data from several other studies indicate a poor prognosis after malignant transformation of GCT; 4 years after diagnosis, mean survival is 40% to 50%.10,16 The most common clinical presentation of transformation of GCT into malignancy is pain, often with coincident swelling of the native wound bed. However, a few cases have been identified with radiologic imaging alone and without a period of clinical symptoms.16

To our knowledge, this case report is the first to describe a longitudinal assessment of the transformation of a benign GCT of bone into an epithelioid angiosarcoma. Whereas an earlier reported GCT of bone transformed into epithelioid angiosarcoma after irradiation,12 our patient’s GCT of bone transformed without irradiation. GCTs of bone are locally aggressive benign tumors and are relatively rare. Malignant transformation of a benign bone tumor a decade after initial, definitive treatment is concerning, especially given the poor prognosis after malignant transformation in this clinical scenario. Current adjuvant treatments have not changed the prognosis. The literature includes a wide variety of histologic transformations, including high-grade sarcomas, after a long disease-free interval. Although malignant transformation of benign GCTs is rare, clinicians should be aware of the potential. Interval monitoring of GCTs may be necessary in patients with symptoms concerning for malignant transformation—pain or swelling in the wound bed—and patients should know to immediately inform their physician of any changes in pain level or local wound bed. Clinicians should maintain a high clinical suspicion for malignant transformation or late recurrence of GCT in a patient with new pain at the site of a previously treated GCT of bone with a disease-free interval of several years.

1. Unni KK. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996.

2. Errani C, Ruggieri P, Asenzio MA, et al. Giant cell tumor of the extremity: a review of 349 cases from a single institution. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(1):1-7.

3. Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(1):106-114.

4. Werner M. Giant cell tumour of bone: morphological, biological and histogenetical aspects. Int Orthop. 2006;30(6):484-489.

5 Klenke FM, Wenger DE, Inwards CY, Rose PS, Sim FH. Recurrent giant cell tumor of long bones: analysis of surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1181-1187.

6. McDonald DJ, Sim FH, McLeod RA, Dahlin DC. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(2):235-242.

7. Kay RM, Eckardt JJ, Seeger LL, Mirra JM, Hak DJ. Pulmonary metastasis of benign giant cell tumor of bone. Six histologically confirmed cases, including one of spontaneous regression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(302):219-230.

8. Maloney WJ, Vaughan LM, Jones HH, Ross J, Nagel DA. Benign metastasizing giant-cell tumor of bone. Report of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(243):208-215.

9. Hutter RV, Worcester JN Jr, Francis KC, Foote FW Jr, Stewart FW. Benign and malignant giant cell tumors of bone. A clinicopathological analysis of the natural history of the disease. Cancer. 1962;15:653-690.

10. Grote HJ, Braun M, Kalinski T, et al. Spontaneous malignant transformation of conventional giant cell tumor. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(3):169-175.

11. Rock MG, Sim FH, Unni KK, et al. Secondary malignant giant-cell tumor of bone. Clinicopathological assessment of nineteen patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(7):1073-1079.

12. Mittal S, Goswami C, Kanoria N, Bhattacharya A. Post-irradiation angiosarcoma of bone. J Cancer Res Ther. 2007;3(2):96-99.

13. Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Staals EL. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer. 2003;97(10):2520-2529.

14. Dahlin DC, Cupps RE, Johnson EW Jr. Giant-cell tumor: a study of 195 cases. Cancer. 1970;25(5):1061-1070.

15. Balaji GG, Arockiaraj JS, Roy AC, Deepak B. Primary epithelioid angiosarcoma of the calcaneum: a diagnostic dilemma. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53(2):239-242.

16. Anract P, De Pinieux G, Cottias P, Pouillart P, Forest M, Tomeno B. Malignant giant-cell tumours of bone. Clinico-pathological types and prognosis: a review of 29 cases. Int Orthop. 1998;22(1):19-26.

Take-Home Points

- Malignant transformation of a benign GCT is extremely rare.

- It is difficult to distinguish between an early malignant transformation and an overlooked malignancy.

- The most common clinical presentation of transformation of GCT into malignancy is pain, often with swelling.

- Interval monitoring of GCTs may be necessary in patients with symptoms concerning for malignant transformation.

- Clinicians should maintain a high clinical suspicion for malignant transformation or late recurrence of GCT in a patient with new pain at the wound site.

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of bone account for about 5% of all primary bone tumors in adults, with a predominance in the third decade in life.1 Clinically, GCT of bone often presents with pain, pathologic fracture, and/or soft- tissue expansion in the epiphysis of long bones. However, GCT of bone also has been reported in non-long bones, such as the talus and the calcaneus.2,3 Histologically, GCT of bone consists of neoplastic stromal cells, mononuclear histiocytic cells, and multinucleated giant cells that resemble osteoclasts.4 The radiologic appearance of GCT is often described as a lytic, eccentrically located bony lesion that extends near the articular surface in patients with closed physes. Many GCTs have aggressive radiologic features with possible extensive bony destruction and soft-tissue extension.

Although categorized as a benign lesion, GCT can be locally aggressive, with a variable local recurrence rate of 0% to 65%, depending on treatment modality and skeletal location. Given the aggressiveness of GCT of bone, recommendations for operative intervention include intralesional curettage with adjuvant therapy (eg, cryotherapy, phenol, argon beam, electrocautery) and placement of bone void fillers (eg, bone graft polymethylmethacrylate). Wide resection is recommended when the articular surface is no longer viable for reconstruction secondary to extensive destruction. Some authors have reported that surgical margin is the only risk factor in local recurrence,5,6 and thus complete resection may be needed for tumor eradication. In addition, about 3% of GCTs demonstrate benign pulmonary implants, which have been cited as cause of death in 16% to 25% of reported cases of pulmonary spread.7,8

The literature includes few reports of primary or secondary malignant transformation of GCT. Hutter and colleagues9 defined primary malignant GCT as GCT with sarcomatous tissue juxtaposed with zones of typical benign GCT cells. Secondary malignant GCT is a sarcomatous lesion at the site of a previously documented benign GCT. Secondary malignant GCT of bone histologically has been classified as a fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, or osteosarcoma transformation.10

Most malignant transformations of GCT of bone have been attributed to previous irradiation of the lesion.11,12 However, there are some case reports of benign bone GCT malignant transformation in situ without any other medical intervention. It was reported that non-radiation-induced secondary transformations occur relatively early after GCT treatment.13 During the early stages of tumor recurrence, however, it is difficult to distinguish between malignant transformation and primary disease overlooked as a result of sampling error.

We report a case of secondary malignant transformation of GCT of bone 11 years after surgical curettage, cryotherapy, and cementation without adjuvant radiation therapy. To our knowledge, this case report is the first to describe transformation of a nonirradiated benign GCT into an aggressive, high-grade epithelioid angiosarcoma, a very rare vascular bone tumor. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

In July 2003, a 46-year-old woman presented with left heel pain of several months’ duration. Plain radiographs showed a nonaggressive-appearing lytic lesion of the superior aspect of the posterior calcaneal tuberosity with a small cortical incongruity along the superior margin of the lesion (Figures 1A-1D).

A postoperative splint was placed, and weight-bearing progressed over 6 weeks. The patient was followed at 2- to 3-month intervals over the first 5 postoperative years. She was able to work and perform activities of daily living, but her postoperative course was complicated by significant chronic pain in multiple extremities and long-term treatment by the chronic pain service. At no time did postoperative imaging—magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 6 years, whole-body bone scan at 7 years, plain radiographs at 10 years—show evidence of recurrence.

Radiographs showed stable postoperative changes with a small radiolucent area (with sclerotic rim) surrounding the cement-bone interface. Given its proximity to the Achilles tendon and more motion than usual at the wound site, the radiolucency likely was caused by small movements of the interface. The radiolucent area remained stable over a 15-month period.

Whole-body bone scan showed a small area of osteoblastic activity in the left calcaneus, consistent with inflammation surrounding the bone- cement interface, but the uptake was minor relative to other areas of signal, and there were no significant inflammatory reactive changes on MRI (Figures 3A, 3B).

Over 11 years, regular 6- to 12-month follow-up examinations revealed no significant changes in the left foot or in plain radiographs of the chest. In addition, physical examinations revealed no evidence of a palpable mass of the left foot.

In July 2014 (11 years after curettage and cementation), the patient presented to her pain clinic appointment with severe left foot pain. She said that, over a few weeks, she experienced a significant increase in pain and developed posterolateral foot swelling, which limited her ability to ambulate. Plain radiographs showed a significant soft-tissue prominence around the posterior calcaneus, increased lucency around the bone-cement interface in the calcaneus with elevation, and a cortical break of the superior margin of the posterior calcaneus (Figures 3C, 3D). MRI showed a large lobular mass in the calcaneus and surrounding soft tissue with T1 and T2 signal heterogeneity and enhancement after administration of gadolinium (Figures 4A-4D). There was a large extraosseous extension of the calcaneus-based mass laterally and superiorly with edema in the surrounding hindfoot region (Figure 4).

Physical examination revealed exquisite tenderness along the lateral and posterior aspects of the left hindfoot. The patient was unable to bear weight and had soft-tissue swelling throughout the foot and mid calf as well as a palpable mass in the posterior heel. She was otherwise neurovascularly intact through all distributions of the left lower extremity. It was unclear if the GCT of the calcaneus had recurred or if there was a new, secondary tumor. Given her severe pain and morbidity, the patient decided to proceed with open biopsy and a pathology-pending plan for possible amputation in the near future.

In August 2014, an open biopsy with intraoperative frozen evaluation yielded a diagnosis of malignant neoplasm not otherwise specified. Permanent sections showed a proliferation of malignant epithelioid cells with extensive necrosis, hemorrhage, and hemosiderin deposition but no multinucleated giant cells.

Transformation of the GCT into a high-grade epithelioid angiosarcoma prompted presentation of the patient’s case to a multidisciplinary board of physicians with a focused clinical practice in sarcoma management. The board included board-certified specialists in orthopedic oncology, pathology, musculoskeletal radiology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. Although discussion included pre-resection use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to evaluate for disease response, the patient’s severe pain led her to forgo this treatment and proceed directly to below-knee amputation.

Amputation revealed a 7.7-cm hemorrhagic necrotic mass composed of a highly cellular spindle and epithelioid malignancy with abundant hemosiderin deposition (Figure 5). In addition, several atypical mitotic figures and malignant multinucleated tumor giant cells were randomly scattered throughout the neoplasm.

At first follow-up, the patient reported significant pain relief and asked to begin titrating off her chronic pain medicine. Clinical staging, which involved performing whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography, revealed nothing concerning for metastases. When this report was being written, the patient was being monitored for recurrent disease in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. In the absence of residual sarcoma, our medical oncology team discussed adjuvant chemotherapy options with her. Subsequently, however, she proceeded only with observation and periodic imaging.

Discussion

Malignant transformation of a benign GCT is extremely rare, especially in cases in which the tumor bed has not previously undergone radiation therapy. Although the literature includes historical case reports, primary and secondary malignant GCTs comprise <9% of all GCTs.11,13,14 Primary bone epithelioid angiosarcoma is also extremely rare, especially in the calcaneus; only 1 case is described in the literature.15 In this article, we report on a benign GCT of bone that transformed into an epithelioid angiosarcoma more than a decade after the GCT was treated with curettage and cementation.

The fact that the malignant areas of a previous tumor may have been missed because of sampling error is important for benign GCT of bone in the early postoperative period, as distinguishing between early malignant transformation and an overlooked malignancy may not be possible. However, transformation is more likely the case when a benign GCT becomes a high-grade malignancy after a long disease-free interval. Several authors have indicated that a benign GCT tumor recurring with a secondary malignancy 2 to 5 years after initial GCT treatment suggests malignant transformation.16 Grote and colleagues10 compiled reports of malignant transformation of GCT of bone and described the clinicopathologic features of secondary malignant transformation of GCTs. The data they compiled and data from several other studies indicate a poor prognosis after malignant transformation of GCT; 4 years after diagnosis, mean survival is 40% to 50%.10,16 The most common clinical presentation of transformation of GCT into malignancy is pain, often with coincident swelling of the native wound bed. However, a few cases have been identified with radiologic imaging alone and without a period of clinical symptoms.16

To our knowledge, this case report is the first to describe a longitudinal assessment of the transformation of a benign GCT of bone into an epithelioid angiosarcoma. Whereas an earlier reported GCT of bone transformed into epithelioid angiosarcoma after irradiation,12 our patient’s GCT of bone transformed without irradiation. GCTs of bone are locally aggressive benign tumors and are relatively rare. Malignant transformation of a benign bone tumor a decade after initial, definitive treatment is concerning, especially given the poor prognosis after malignant transformation in this clinical scenario. Current adjuvant treatments have not changed the prognosis. The literature includes a wide variety of histologic transformations, including high-grade sarcomas, after a long disease-free interval. Although malignant transformation of benign GCTs is rare, clinicians should be aware of the potential. Interval monitoring of GCTs may be necessary in patients with symptoms concerning for malignant transformation—pain or swelling in the wound bed—and patients should know to immediately inform their physician of any changes in pain level or local wound bed. Clinicians should maintain a high clinical suspicion for malignant transformation or late recurrence of GCT in a patient with new pain at the site of a previously treated GCT of bone with a disease-free interval of several years.

Take-Home Points

- Malignant transformation of a benign GCT is extremely rare.

- It is difficult to distinguish between an early malignant transformation and an overlooked malignancy.

- The most common clinical presentation of transformation of GCT into malignancy is pain, often with swelling.

- Interval monitoring of GCTs may be necessary in patients with symptoms concerning for malignant transformation.

- Clinicians should maintain a high clinical suspicion for malignant transformation or late recurrence of GCT in a patient with new pain at the wound site.

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of bone account for about 5% of all primary bone tumors in adults, with a predominance in the third decade in life.1 Clinically, GCT of bone often presents with pain, pathologic fracture, and/or soft- tissue expansion in the epiphysis of long bones. However, GCT of bone also has been reported in non-long bones, such as the talus and the calcaneus.2,3 Histologically, GCT of bone consists of neoplastic stromal cells, mononuclear histiocytic cells, and multinucleated giant cells that resemble osteoclasts.4 The radiologic appearance of GCT is often described as a lytic, eccentrically located bony lesion that extends near the articular surface in patients with closed physes. Many GCTs have aggressive radiologic features with possible extensive bony destruction and soft-tissue extension.