User login

Subacute loss of vision in one eye • rash on hands and feet • plaques with scaling on genitals • Dx?

THE CASE

A 67-year-old man presented to the hospital with subacute loss of vision in his left eye. The visual changes began 2 weeks earlier, with a central area of visual loss that had since progressed to near complete vision loss in the left eye.

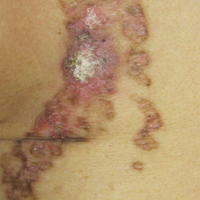

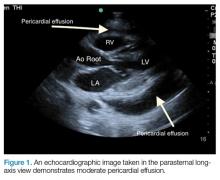

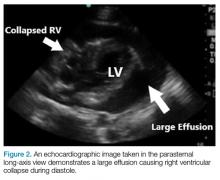

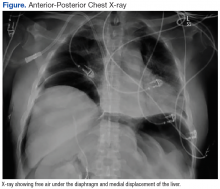

Physical examination revealed patchy alopecia, a scaling and hyperkeratotic rash of his hands and feet (FIGURE 1), and blanching, erythematous plaques with associated scaling on the scrotum and glans penis. Ophthalmologic examination revealed 1/200 vision in his left eye with a large plaque occupying a substantial portion of the superior quadrant, smaller perifoveal plaques in both of his eyes, and a small infiltrate above the left optic nerve head (FIGURE 2). The patient also described fatigue, loss of taste, and an unintentional weight loss of 7 to 10 kg over the previous 6 months. He had seen his primary care provider 3 months prior for a burning sensation and scaling rash on his feet and hands, and was prescribed a topical steroid.

The patient’s social history was relevant for intermittent condom use with 6 lifetime female partners, but it was negative for new sexual partners, sexual contact with men, intravenous drug use, tattoos, blood transfusions, or travel outside the state. His medical history was significant for hypertension.

Routine laboratory tests were remarkable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 53 mm/hr (normal: 0-15 mm/hr) and a C-reactive protein of 5.3 mg/dL (normal: <0.5 mg/dL). Lumbar puncture revealed a white blood cell count of 133 cells/mcL (normal: 0-5 cells/mcL) with 87% lymphocytes and protein elevated to 63 mg/dL (normal: 15-40 mg/dL).

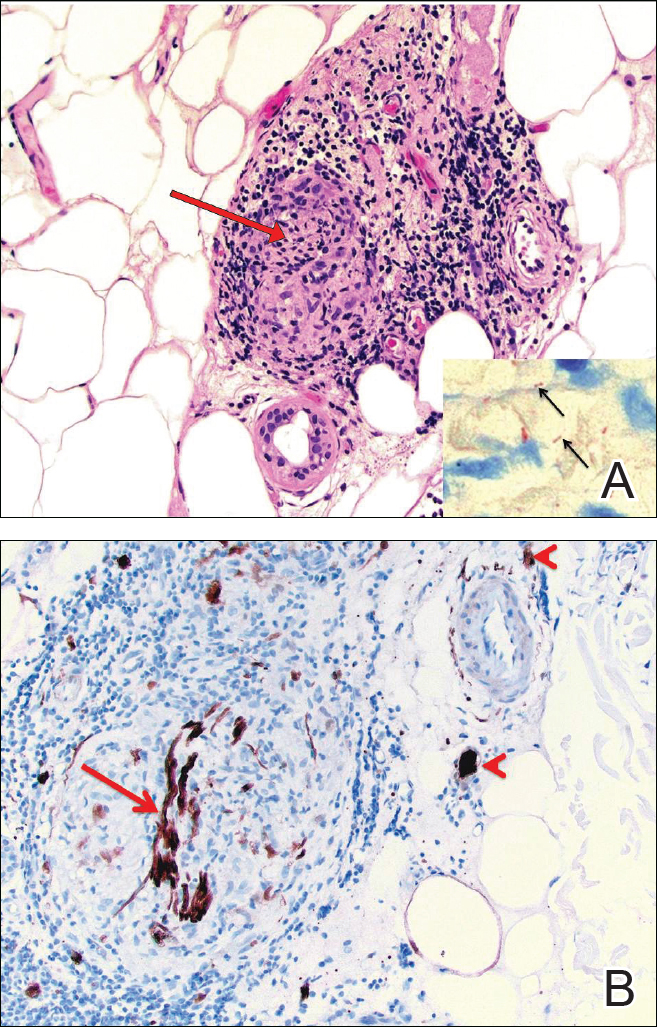

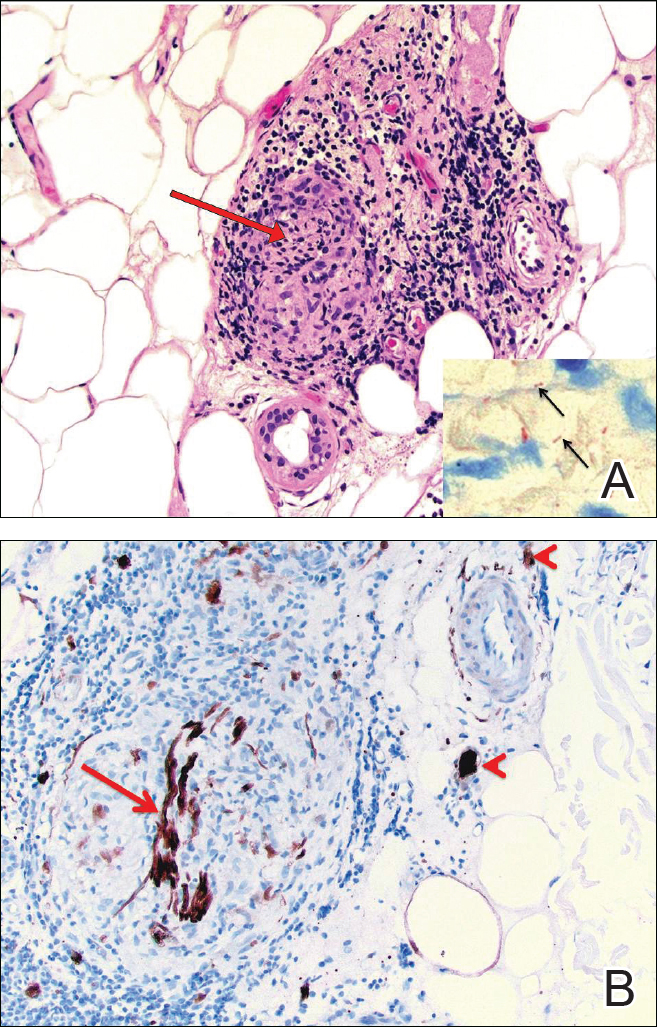

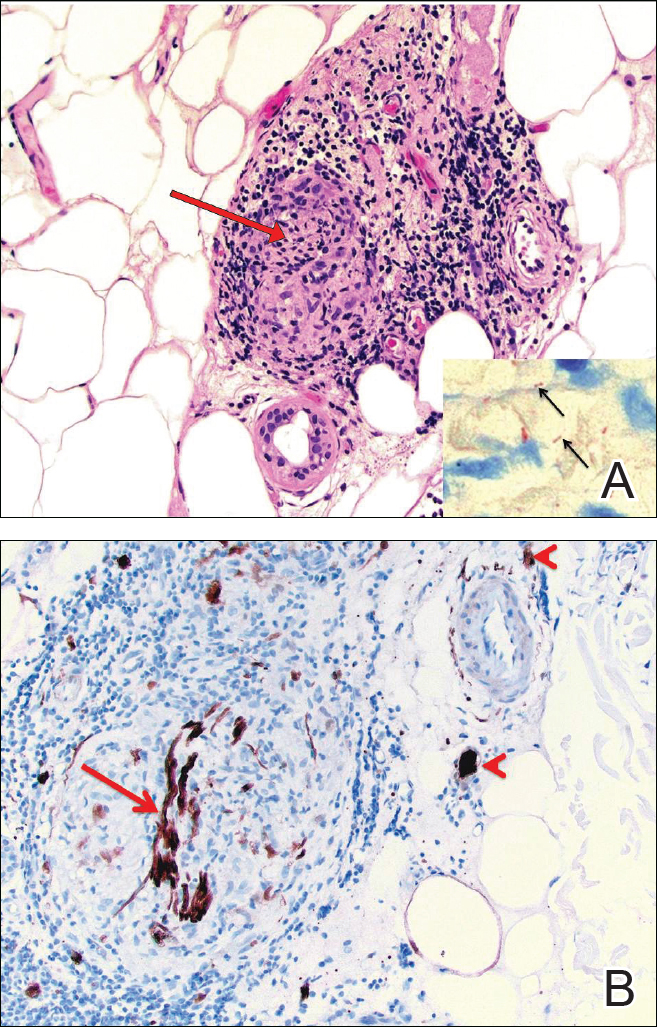

Other tests were ordered and included a serum fourth-generation ELISA to screen for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2, a cerebrospinal fluid venereal disease research laboratory (CSF-VDRL) test, a syphilis IgG screen and reflexive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) quantitation, and tests for cytomegalovirus antibodies, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and Toxoplasma antibodies. Punch biopsy of the patient’s palmar skin changes was also performed; Steiner stain and spirochete immunohistochemical stain were applied to the sample. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbit was unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s HIV screening test came back positive and was followed by confirmation of HIV-1 antibody, with an HIV viral load of 61,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 383 cells/mm3. The CSF-VDRL test and serum syphilis IgG were also positive, and the RPR titer was 1:16. The Steiner and spirochete immunohistochemical stains confirmed the presence of treponemes in the epidermis (FIGURE 3). Taken together, these findings confirmed a unifying diagnosis of ocular syphilis and syphilitic keratoderma with concomitant HIV.

DISCUSSION

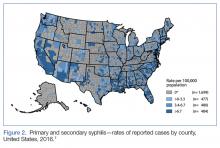

After reaching an all-time low in the mid-1990s, several recent reports indicate that the incidence of syphilis is again increasing in North America.1-3 In the United States, annual incidence rates have increased from 2.1/100,000 in 2000 to 5.3/100,000 in 2013.3 The increase has been most notable in younger men, men who have sex with men (MSM), and those with HIV infection.1

A 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory highlights an unusual collection of cases of ocular syphilis, predominantly in HIV-infected MSM, from California and Washington.4 Disease sequelae in this outbreak have resulted in blindness.

HIV coinfection has been reported in 27.5% of males and 12.4% of females with new diagnoses of syphilis.1 Patients with HIV are more likely to have asymptomatic primary syphilitic infection, and may have an earlier onset of secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis.1,5,6 Cutaneous findings such as malignant syphilis (characterized by ulcerating, pustular, or rupioid lesions), as well as other atypical rashes mimicking eczema, leprosy, mycosis fungoides, or keratoderma blenorrhagicum, may all be more common in those with HIV coinfection.6 Ageusia or dysgeusia is rare in syphilis, and to our knowledge has only been described with concomitant oral lesions.7

MANAGEMENT

Our patient was treated with a continuous daily infusion of 20 million units of penicillin G for 14 days, one drop of 1% ocular prednisolone in each eye 4 times daily for 4 weeks, one drop of 2% cyclopentoate in each eye 2 times daily for 4 weeks, and 60 mg/d of oral prednisone tapered over 3 months. For the HIV infection, he was started on antiretroviral therapy soon after diagnosis.

Within 48 hours of initiating penicillin, he reported a marked improvement in vision and regained the ability to taste. After one week of therapy, near resolution of the palmoplantar rash was noted and the patient was discharged on hospital Day 8. At a 3-month follow-up visit, he was asymptomatic, with return of normal sensation. Repeat ophthalmologic examination showed no evidence of disease.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case complements other sporadic reports of symptoms of ocular and cutaneous syphilis serving as the initial presentation of HIV infection.5,8,9 Risk-factor based screening for HIV often leads to missed diagnoses, and early recognition of this constellation of symptoms may aid in prompt diagnosis and treatment of syphilis and HIV.10

1. Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:456-466.

2. Butler JN, Throne JE. Current status of HIV infection and ocular disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:517-522.

3. Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis–United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:402-406.

4. Woolston S, Cohen SE, Fanfare RN, et al. A cluster of ocular syphilis cases–Seattle, Washington, and San Francisco, California, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1150-1151.

5. Kirby JS, Goreshi R, Mahoney N. Syphilitic palmoplantar keratoderma and ocular disease: a rare combination in an HIV-positive patient. Cutis. 2009;84:305-310.

6. Shimizu S, Yasui C, Tajima Y, et al. Unusual cutaneous features of syphilis in patients positive for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:169-172.

7. Giovani EM, de Paula Neto ER, Vieira BC, et al. Conventional systemic treatments associated with therapeutic sites of local lesions of secondary syphilis in the oral cavity in patients with AIDS. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23:670-673.

8. Kunkel J, Schürmann D, Pleyer U, et al. Ocular syphilis–indicator of previously unknown HIV-infection. J Infect. 2009;58:32-36.

9. Kishimoto M, Lee MJ, Mor A, et al. Syphilis mimicking Reiter’s syndrome in an HIV-positive patient. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332:90-92.

10. Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, et al. Risk-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing fails to detect the majority of HIV-infected persons in medical care settings. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:329-333.

THE CASE

A 67-year-old man presented to the hospital with subacute loss of vision in his left eye. The visual changes began 2 weeks earlier, with a central area of visual loss that had since progressed to near complete vision loss in the left eye.

Physical examination revealed patchy alopecia, a scaling and hyperkeratotic rash of his hands and feet (FIGURE 1), and blanching, erythematous plaques with associated scaling on the scrotum and glans penis. Ophthalmologic examination revealed 1/200 vision in his left eye with a large plaque occupying a substantial portion of the superior quadrant, smaller perifoveal plaques in both of his eyes, and a small infiltrate above the left optic nerve head (FIGURE 2). The patient also described fatigue, loss of taste, and an unintentional weight loss of 7 to 10 kg over the previous 6 months. He had seen his primary care provider 3 months prior for a burning sensation and scaling rash on his feet and hands, and was prescribed a topical steroid.

The patient’s social history was relevant for intermittent condom use with 6 lifetime female partners, but it was negative for new sexual partners, sexual contact with men, intravenous drug use, tattoos, blood transfusions, or travel outside the state. His medical history was significant for hypertension.

Routine laboratory tests were remarkable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 53 mm/hr (normal: 0-15 mm/hr) and a C-reactive protein of 5.3 mg/dL (normal: <0.5 mg/dL). Lumbar puncture revealed a white blood cell count of 133 cells/mcL (normal: 0-5 cells/mcL) with 87% lymphocytes and protein elevated to 63 mg/dL (normal: 15-40 mg/dL).

Other tests were ordered and included a serum fourth-generation ELISA to screen for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2, a cerebrospinal fluid venereal disease research laboratory (CSF-VDRL) test, a syphilis IgG screen and reflexive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) quantitation, and tests for cytomegalovirus antibodies, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and Toxoplasma antibodies. Punch biopsy of the patient’s palmar skin changes was also performed; Steiner stain and spirochete immunohistochemical stain were applied to the sample. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbit was unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s HIV screening test came back positive and was followed by confirmation of HIV-1 antibody, with an HIV viral load of 61,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 383 cells/mm3. The CSF-VDRL test and serum syphilis IgG were also positive, and the RPR titer was 1:16. The Steiner and spirochete immunohistochemical stains confirmed the presence of treponemes in the epidermis (FIGURE 3). Taken together, these findings confirmed a unifying diagnosis of ocular syphilis and syphilitic keratoderma with concomitant HIV.

DISCUSSION

After reaching an all-time low in the mid-1990s, several recent reports indicate that the incidence of syphilis is again increasing in North America.1-3 In the United States, annual incidence rates have increased from 2.1/100,000 in 2000 to 5.3/100,000 in 2013.3 The increase has been most notable in younger men, men who have sex with men (MSM), and those with HIV infection.1

A 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory highlights an unusual collection of cases of ocular syphilis, predominantly in HIV-infected MSM, from California and Washington.4 Disease sequelae in this outbreak have resulted in blindness.

HIV coinfection has been reported in 27.5% of males and 12.4% of females with new diagnoses of syphilis.1 Patients with HIV are more likely to have asymptomatic primary syphilitic infection, and may have an earlier onset of secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis.1,5,6 Cutaneous findings such as malignant syphilis (characterized by ulcerating, pustular, or rupioid lesions), as well as other atypical rashes mimicking eczema, leprosy, mycosis fungoides, or keratoderma blenorrhagicum, may all be more common in those with HIV coinfection.6 Ageusia or dysgeusia is rare in syphilis, and to our knowledge has only been described with concomitant oral lesions.7

MANAGEMENT

Our patient was treated with a continuous daily infusion of 20 million units of penicillin G for 14 days, one drop of 1% ocular prednisolone in each eye 4 times daily for 4 weeks, one drop of 2% cyclopentoate in each eye 2 times daily for 4 weeks, and 60 mg/d of oral prednisone tapered over 3 months. For the HIV infection, he was started on antiretroviral therapy soon after diagnosis.

Within 48 hours of initiating penicillin, he reported a marked improvement in vision and regained the ability to taste. After one week of therapy, near resolution of the palmoplantar rash was noted and the patient was discharged on hospital Day 8. At a 3-month follow-up visit, he was asymptomatic, with return of normal sensation. Repeat ophthalmologic examination showed no evidence of disease.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case complements other sporadic reports of symptoms of ocular and cutaneous syphilis serving as the initial presentation of HIV infection.5,8,9 Risk-factor based screening for HIV often leads to missed diagnoses, and early recognition of this constellation of symptoms may aid in prompt diagnosis and treatment of syphilis and HIV.10

THE CASE

A 67-year-old man presented to the hospital with subacute loss of vision in his left eye. The visual changes began 2 weeks earlier, with a central area of visual loss that had since progressed to near complete vision loss in the left eye.

Physical examination revealed patchy alopecia, a scaling and hyperkeratotic rash of his hands and feet (FIGURE 1), and blanching, erythematous plaques with associated scaling on the scrotum and glans penis. Ophthalmologic examination revealed 1/200 vision in his left eye with a large plaque occupying a substantial portion of the superior quadrant, smaller perifoveal plaques in both of his eyes, and a small infiltrate above the left optic nerve head (FIGURE 2). The patient also described fatigue, loss of taste, and an unintentional weight loss of 7 to 10 kg over the previous 6 months. He had seen his primary care provider 3 months prior for a burning sensation and scaling rash on his feet and hands, and was prescribed a topical steroid.

The patient’s social history was relevant for intermittent condom use with 6 lifetime female partners, but it was negative for new sexual partners, sexual contact with men, intravenous drug use, tattoos, blood transfusions, or travel outside the state. His medical history was significant for hypertension.

Routine laboratory tests were remarkable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 53 mm/hr (normal: 0-15 mm/hr) and a C-reactive protein of 5.3 mg/dL (normal: <0.5 mg/dL). Lumbar puncture revealed a white blood cell count of 133 cells/mcL (normal: 0-5 cells/mcL) with 87% lymphocytes and protein elevated to 63 mg/dL (normal: 15-40 mg/dL).

Other tests were ordered and included a serum fourth-generation ELISA to screen for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2, a cerebrospinal fluid venereal disease research laboratory (CSF-VDRL) test, a syphilis IgG screen and reflexive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) quantitation, and tests for cytomegalovirus antibodies, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and Toxoplasma antibodies. Punch biopsy of the patient’s palmar skin changes was also performed; Steiner stain and spirochete immunohistochemical stain were applied to the sample. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbit was unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s HIV screening test came back positive and was followed by confirmation of HIV-1 antibody, with an HIV viral load of 61,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 383 cells/mm3. The CSF-VDRL test and serum syphilis IgG were also positive, and the RPR titer was 1:16. The Steiner and spirochete immunohistochemical stains confirmed the presence of treponemes in the epidermis (FIGURE 3). Taken together, these findings confirmed a unifying diagnosis of ocular syphilis and syphilitic keratoderma with concomitant HIV.

DISCUSSION

After reaching an all-time low in the mid-1990s, several recent reports indicate that the incidence of syphilis is again increasing in North America.1-3 In the United States, annual incidence rates have increased from 2.1/100,000 in 2000 to 5.3/100,000 in 2013.3 The increase has been most notable in younger men, men who have sex with men (MSM), and those with HIV infection.1

A 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory highlights an unusual collection of cases of ocular syphilis, predominantly in HIV-infected MSM, from California and Washington.4 Disease sequelae in this outbreak have resulted in blindness.

HIV coinfection has been reported in 27.5% of males and 12.4% of females with new diagnoses of syphilis.1 Patients with HIV are more likely to have asymptomatic primary syphilitic infection, and may have an earlier onset of secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis.1,5,6 Cutaneous findings such as malignant syphilis (characterized by ulcerating, pustular, or rupioid lesions), as well as other atypical rashes mimicking eczema, leprosy, mycosis fungoides, or keratoderma blenorrhagicum, may all be more common in those with HIV coinfection.6 Ageusia or dysgeusia is rare in syphilis, and to our knowledge has only been described with concomitant oral lesions.7

MANAGEMENT

Our patient was treated with a continuous daily infusion of 20 million units of penicillin G for 14 days, one drop of 1% ocular prednisolone in each eye 4 times daily for 4 weeks, one drop of 2% cyclopentoate in each eye 2 times daily for 4 weeks, and 60 mg/d of oral prednisone tapered over 3 months. For the HIV infection, he was started on antiretroviral therapy soon after diagnosis.

Within 48 hours of initiating penicillin, he reported a marked improvement in vision and regained the ability to taste. After one week of therapy, near resolution of the palmoplantar rash was noted and the patient was discharged on hospital Day 8. At a 3-month follow-up visit, he was asymptomatic, with return of normal sensation. Repeat ophthalmologic examination showed no evidence of disease.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case complements other sporadic reports of symptoms of ocular and cutaneous syphilis serving as the initial presentation of HIV infection.5,8,9 Risk-factor based screening for HIV often leads to missed diagnoses, and early recognition of this constellation of symptoms may aid in prompt diagnosis and treatment of syphilis and HIV.10

1. Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:456-466.

2. Butler JN, Throne JE. Current status of HIV infection and ocular disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:517-522.

3. Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis–United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:402-406.

4. Woolston S, Cohen SE, Fanfare RN, et al. A cluster of ocular syphilis cases–Seattle, Washington, and San Francisco, California, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1150-1151.

5. Kirby JS, Goreshi R, Mahoney N. Syphilitic palmoplantar keratoderma and ocular disease: a rare combination in an HIV-positive patient. Cutis. 2009;84:305-310.

6. Shimizu S, Yasui C, Tajima Y, et al. Unusual cutaneous features of syphilis in patients positive for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:169-172.

7. Giovani EM, de Paula Neto ER, Vieira BC, et al. Conventional systemic treatments associated with therapeutic sites of local lesions of secondary syphilis in the oral cavity in patients with AIDS. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23:670-673.

8. Kunkel J, Schürmann D, Pleyer U, et al. Ocular syphilis–indicator of previously unknown HIV-infection. J Infect. 2009;58:32-36.

9. Kishimoto M, Lee MJ, Mor A, et al. Syphilis mimicking Reiter’s syndrome in an HIV-positive patient. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332:90-92.

10. Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, et al. Risk-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing fails to detect the majority of HIV-infected persons in medical care settings. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:329-333.

1. Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:456-466.

2. Butler JN, Throne JE. Current status of HIV infection and ocular disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:517-522.

3. Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis–United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:402-406.

4. Woolston S, Cohen SE, Fanfare RN, et al. A cluster of ocular syphilis cases–Seattle, Washington, and San Francisco, California, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1150-1151.

5. Kirby JS, Goreshi R, Mahoney N. Syphilitic palmoplantar keratoderma and ocular disease: a rare combination in an HIV-positive patient. Cutis. 2009;84:305-310.

6. Shimizu S, Yasui C, Tajima Y, et al. Unusual cutaneous features of syphilis in patients positive for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:169-172.

7. Giovani EM, de Paula Neto ER, Vieira BC, et al. Conventional systemic treatments associated with therapeutic sites of local lesions of secondary syphilis in the oral cavity in patients with AIDS. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23:670-673.

8. Kunkel J, Schürmann D, Pleyer U, et al. Ocular syphilis–indicator of previously unknown HIV-infection. J Infect. 2009;58:32-36.

9. Kishimoto M, Lee MJ, Mor A, et al. Syphilis mimicking Reiter’s syndrome in an HIV-positive patient. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332:90-92.

10. Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, et al. Risk-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing fails to detect the majority of HIV-infected persons in medical care settings. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:329-333.

Erythematous, friable nipple with loss of protrusion • history of breastfeeding • Dx?

THE CASE

A 34-year-old healthy woman presented to the breast surgical oncology clinic with skin changes to her left nipple after being referred by her primary care provider. She attributed the skin changes to shearing from breastfeeding her third child 5 years earlier. Physical examination revealed an erythematous and friable nipple with loss of protrusion (FIGURE 1). The patient reported routine bleeding from her nipple, but said the skin changes had remained stable and denied any breast masses. The patient’s last mammogram was 2.5 years earlier and had only been remarkable for bilateral benign calcifications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

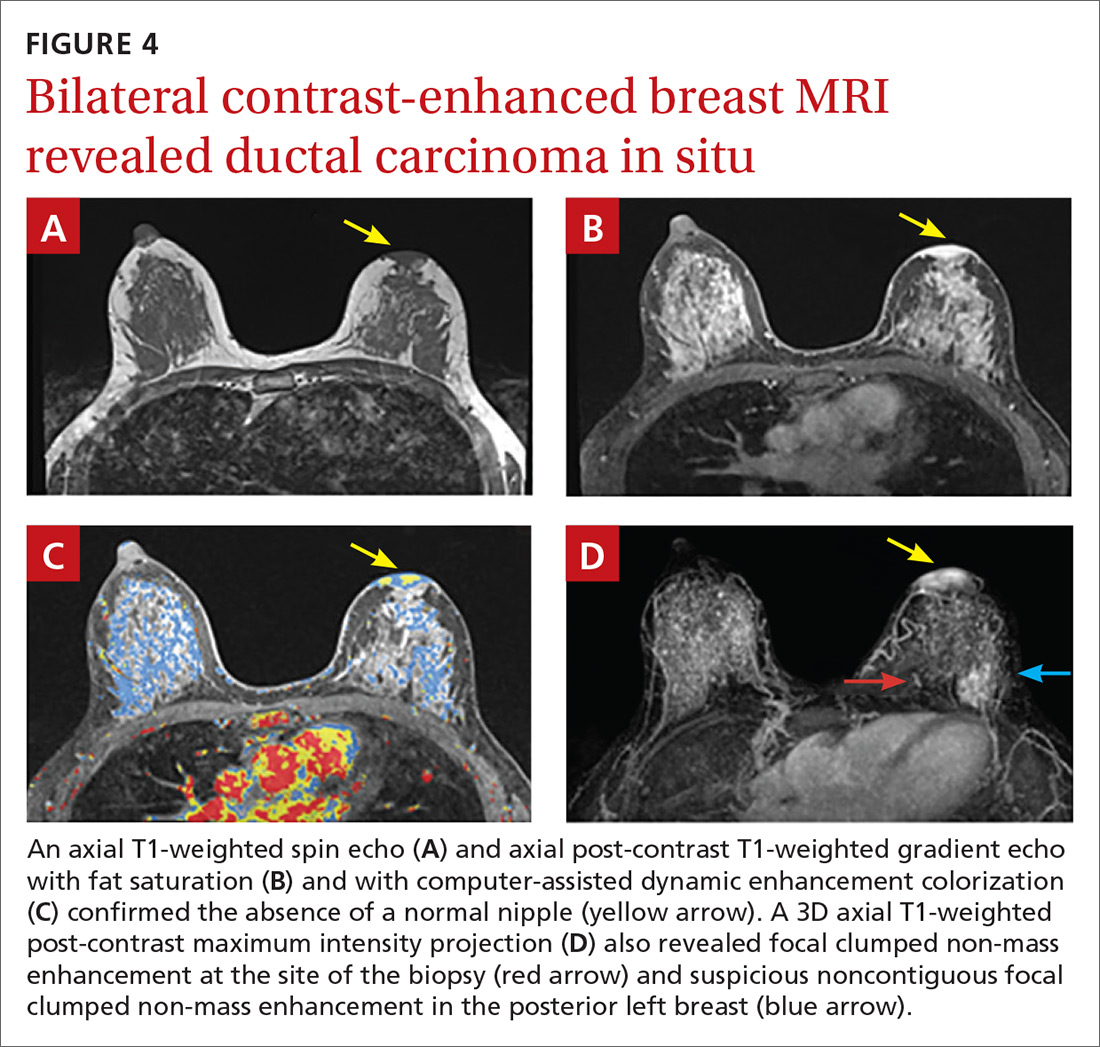

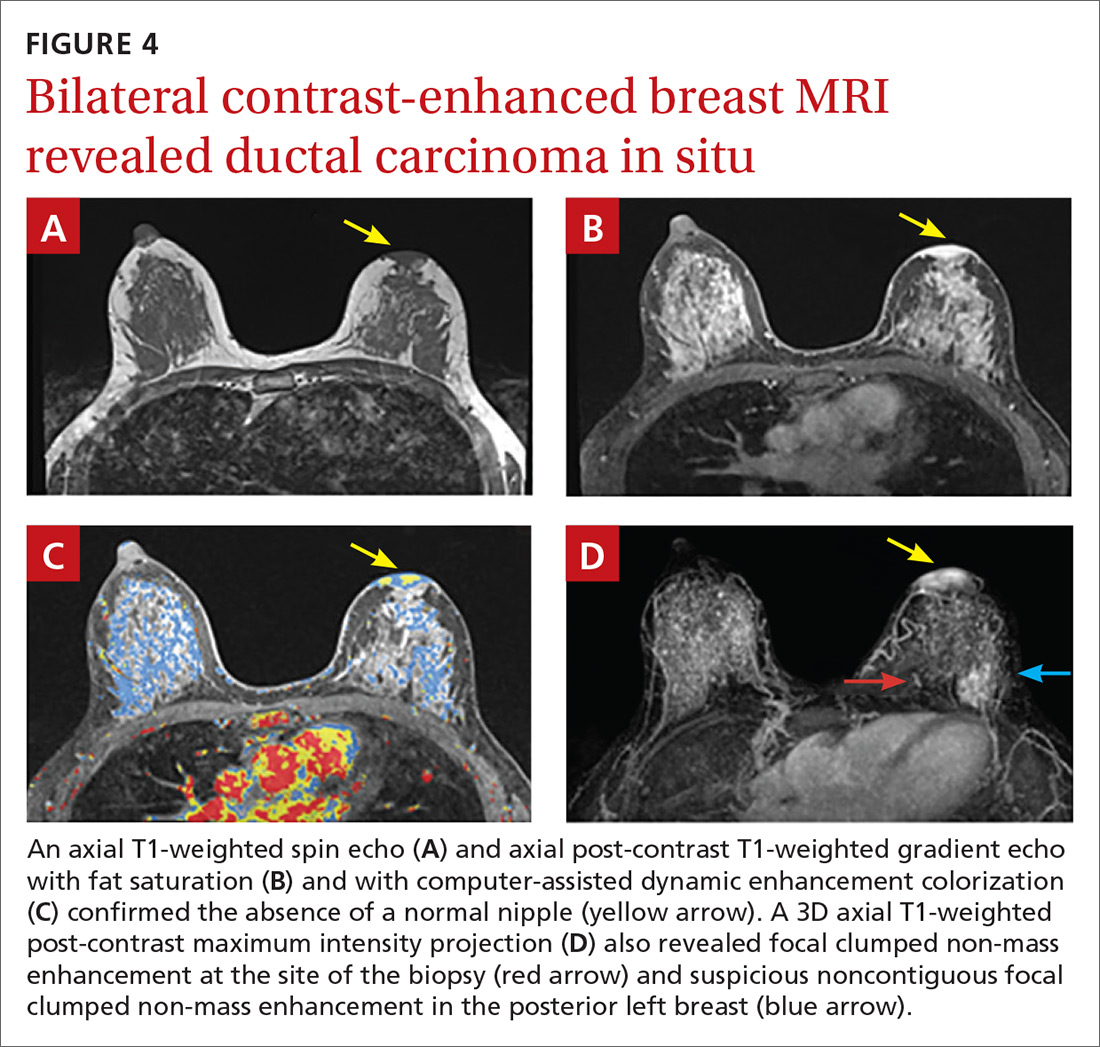

A screening mammogram showed flattening and retraction of the left nipple, as well as suspicious left breast calcifications (BIRADS [Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System] 4 classification, FIGURE 2). A subsequent diagnostic mammogram showed a cluster of fine pleomorphic calcifications in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast (FIGURE 3). A stereotactic core needle biopsy was performed, and results confirmed a diagnosis of high-grade, estrogen receptor-negative, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Subsequent work-up included a staging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a left areola punch biopsy. MRI revealed an absence of a normal left nipple and extensive focal clumped non-mass enhancement in the area of the known DCIS (FIGURE 4). Biopsy results revealed enlarged atypical single cells within the epidermis. The cells stained positive for mucicarmine and cytokeratin 7 and negative for carcinoembryonic antigen and S-100 protein. This ruled out a pagetoid spread of melanoma and confirmed a diagnosis of Paget’s disease (PD) of the breast.

DISCUSSION

PD of the breast is a rare disorder (accounting for 0.5%-5% of all breast cancers) that is clinically characterized by erythematous, eczematous changes of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC).1-7 PD is almost always unilateral and symptoms include pain, burning, and itching of the nipple, often with bloody nipple discharge.1,3-8

PD can be mistaken for benign skin changes and diagnosed as dermatitis or eczema.3,5 Because such changes often resolve temporarily with the use of topical corticosteroids or no treatment at all,2 diagnosis is often delayed. PD of the breast is associated with underlying ductal carcinoma in 90% to 100% of cases,1,2,5,8 so any skin pathology involving the nipple should be assumed to be PD until proven otherwise.

When no palpable mass is noted on physical exam, DCIS is usually found centrally behind the nipple.1 In addition, lymph node involvement is noted in about 60% of cases.1

Confirm the diagnosis with these tests

Diagnosis of PD of the breast is primarily clinical, with pathologic confirmation. All patients with clinically suspected PD should be evaluated using the following tests to determine the need for biopsy.

Mammography with magnification views of the NAC will show thickening, retraction, or flattening of the nipple, microcalcifications of the retroareolar region, and/or a subareolar mass.3 However, because breast tissue appears normal on mammography in 22% to 71% of patients,1,5 the use of ultrasound and potentially MRI to delineate the extent of disease is warranted.

Ultrasound. While there are no characteristic findings on ultrasound, it can be used to detect dilation of the subareolar ducts, calcification, or a mass.4

MRI has a higher sensitivity for detection of occult disease.2,5 MRI is also useful in the evaluation of axillary node asymmetry, which may indicate nodal involvement.2

Treatment is variable and has not been widely studied

Due to the rarity of PD, there are no randomized studies to point toward optimal treatment strategies.7 Treatment for PD is typically surgical and often involves mastectomy, with or without axillary node dissection.1 Retrospective analyses have demonstrated that central lumpectomy (complete resection of the NAC and underlying disease) with radiation therapy has outcomes similar to mastectomy;2 however, the cosmetic result is sometimes unfavorable.

In cases where there is no palpable mass nor mammographic findings of disease, breast conserving therapy may be considered. If chemotherapy is considered, it should be chosen based on the receptor profile of the disease and subsequent oncotype scoring.

The prognosis for patients with PD who are adequately treated and remain disease free after 5 years is excellent. These patients are likely to have achieved cure.2

Our patient underwent left simple mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy and tissue expander placement. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged home on postoperative Day 1. On final pathology, the 2 sentinel nodes were disease free. The left mastectomy specimen was found to have high-grade DCIS with clear surgical margins. The area of involvement was found to be 3.5 cm × 3 cm in size and had clear skin margins. At follow-up one year later, the patient was doing well with no evidence of disease. She subsequently underwent implant insertion.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the unique progression of undiagnosed PD of the breast. It also highlights the importance of ruling out PD when skin changes involving the nipple are present, despite other possible explanations for those changes. This case in particular was complicated by a proximal history of breastfeeding, which erroneously provided an explanation and false reassurance for the primary care provider and patient.

Due to the common association of PD of the breast with underlying DCIS or invasive cancer, the most important aspect of care is early diagnostic work-up and appropriate referral. Primary care physicians have a unique role in obtaining appropriate early diagnostic tests (including mammogram and ultrasound) and making the necessary referral to a breast specialist in the presence of an abnormal physical exam involving the NAC, even in the absence of a palpable mass. In our patient’s case, punch biopsy of the NAC would have been appropriate at the first signs of friable, erythematous changes.

1. Kollmorgen DR, Varanasi JS, Edge SB, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast: a 33-year experience. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:171-177.

2. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard K, Sarr MG, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:9-18.

3. Sandoval-Leon AC, Drews-Elger K, Gomez-Fernandez CR, et al. Paget’s disease of the nipple. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141:1-12.

4. Soler T, Lerin A, Serrano T, et al. Pigmented paget disease of the breast nipple with underlying infiltrating carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:e54-e57.

5. Trebska-McGowan K, Terracina KP, Takabe K. Update on the surgical management of Paget’s disease. Gland Surg. 2013;2:137-142.

6. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard DK, Sarr MG, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast: a clinical perspective. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386;444-450.

7. Durkan B, Bresee C, Bose S, et al. Paget’s disease of the nipple with parenchymal ductal carcinoma in situ is associated with worse prognosis than Paget’s disease alone. Am Surg. 2013;79:1009-1012.

8. Ward KA, Burton JL. Dermatologic diseases of the breast in young women. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:45-52.

THE CASE

A 34-year-old healthy woman presented to the breast surgical oncology clinic with skin changes to her left nipple after being referred by her primary care provider. She attributed the skin changes to shearing from breastfeeding her third child 5 years earlier. Physical examination revealed an erythematous and friable nipple with loss of protrusion (FIGURE 1). The patient reported routine bleeding from her nipple, but said the skin changes had remained stable and denied any breast masses. The patient’s last mammogram was 2.5 years earlier and had only been remarkable for bilateral benign calcifications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A screening mammogram showed flattening and retraction of the left nipple, as well as suspicious left breast calcifications (BIRADS [Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System] 4 classification, FIGURE 2). A subsequent diagnostic mammogram showed a cluster of fine pleomorphic calcifications in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast (FIGURE 3). A stereotactic core needle biopsy was performed, and results confirmed a diagnosis of high-grade, estrogen receptor-negative, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Subsequent work-up included a staging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a left areola punch biopsy. MRI revealed an absence of a normal left nipple and extensive focal clumped non-mass enhancement in the area of the known DCIS (FIGURE 4). Biopsy results revealed enlarged atypical single cells within the epidermis. The cells stained positive for mucicarmine and cytokeratin 7 and negative for carcinoembryonic antigen and S-100 protein. This ruled out a pagetoid spread of melanoma and confirmed a diagnosis of Paget’s disease (PD) of the breast.

DISCUSSION

PD of the breast is a rare disorder (accounting for 0.5%-5% of all breast cancers) that is clinically characterized by erythematous, eczematous changes of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC).1-7 PD is almost always unilateral and symptoms include pain, burning, and itching of the nipple, often with bloody nipple discharge.1,3-8

PD can be mistaken for benign skin changes and diagnosed as dermatitis or eczema.3,5 Because such changes often resolve temporarily with the use of topical corticosteroids or no treatment at all,2 diagnosis is often delayed. PD of the breast is associated with underlying ductal carcinoma in 90% to 100% of cases,1,2,5,8 so any skin pathology involving the nipple should be assumed to be PD until proven otherwise.

When no palpable mass is noted on physical exam, DCIS is usually found centrally behind the nipple.1 In addition, lymph node involvement is noted in about 60% of cases.1

Confirm the diagnosis with these tests

Diagnosis of PD of the breast is primarily clinical, with pathologic confirmation. All patients with clinically suspected PD should be evaluated using the following tests to determine the need for biopsy.

Mammography with magnification views of the NAC will show thickening, retraction, or flattening of the nipple, microcalcifications of the retroareolar region, and/or a subareolar mass.3 However, because breast tissue appears normal on mammography in 22% to 71% of patients,1,5 the use of ultrasound and potentially MRI to delineate the extent of disease is warranted.

Ultrasound. While there are no characteristic findings on ultrasound, it can be used to detect dilation of the subareolar ducts, calcification, or a mass.4

MRI has a higher sensitivity for detection of occult disease.2,5 MRI is also useful in the evaluation of axillary node asymmetry, which may indicate nodal involvement.2

Treatment is variable and has not been widely studied

Due to the rarity of PD, there are no randomized studies to point toward optimal treatment strategies.7 Treatment for PD is typically surgical and often involves mastectomy, with or without axillary node dissection.1 Retrospective analyses have demonstrated that central lumpectomy (complete resection of the NAC and underlying disease) with radiation therapy has outcomes similar to mastectomy;2 however, the cosmetic result is sometimes unfavorable.

In cases where there is no palpable mass nor mammographic findings of disease, breast conserving therapy may be considered. If chemotherapy is considered, it should be chosen based on the receptor profile of the disease and subsequent oncotype scoring.

The prognosis for patients with PD who are adequately treated and remain disease free after 5 years is excellent. These patients are likely to have achieved cure.2

Our patient underwent left simple mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy and tissue expander placement. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged home on postoperative Day 1. On final pathology, the 2 sentinel nodes were disease free. The left mastectomy specimen was found to have high-grade DCIS with clear surgical margins. The area of involvement was found to be 3.5 cm × 3 cm in size and had clear skin margins. At follow-up one year later, the patient was doing well with no evidence of disease. She subsequently underwent implant insertion.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the unique progression of undiagnosed PD of the breast. It also highlights the importance of ruling out PD when skin changes involving the nipple are present, despite other possible explanations for those changes. This case in particular was complicated by a proximal history of breastfeeding, which erroneously provided an explanation and false reassurance for the primary care provider and patient.

Due to the common association of PD of the breast with underlying DCIS or invasive cancer, the most important aspect of care is early diagnostic work-up and appropriate referral. Primary care physicians have a unique role in obtaining appropriate early diagnostic tests (including mammogram and ultrasound) and making the necessary referral to a breast specialist in the presence of an abnormal physical exam involving the NAC, even in the absence of a palpable mass. In our patient’s case, punch biopsy of the NAC would have been appropriate at the first signs of friable, erythematous changes.

THE CASE

A 34-year-old healthy woman presented to the breast surgical oncology clinic with skin changes to her left nipple after being referred by her primary care provider. She attributed the skin changes to shearing from breastfeeding her third child 5 years earlier. Physical examination revealed an erythematous and friable nipple with loss of protrusion (FIGURE 1). The patient reported routine bleeding from her nipple, but said the skin changes had remained stable and denied any breast masses. The patient’s last mammogram was 2.5 years earlier and had only been remarkable for bilateral benign calcifications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A screening mammogram showed flattening and retraction of the left nipple, as well as suspicious left breast calcifications (BIRADS [Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System] 4 classification, FIGURE 2). A subsequent diagnostic mammogram showed a cluster of fine pleomorphic calcifications in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast (FIGURE 3). A stereotactic core needle biopsy was performed, and results confirmed a diagnosis of high-grade, estrogen receptor-negative, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Subsequent work-up included a staging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a left areola punch biopsy. MRI revealed an absence of a normal left nipple and extensive focal clumped non-mass enhancement in the area of the known DCIS (FIGURE 4). Biopsy results revealed enlarged atypical single cells within the epidermis. The cells stained positive for mucicarmine and cytokeratin 7 and negative for carcinoembryonic antigen and S-100 protein. This ruled out a pagetoid spread of melanoma and confirmed a diagnosis of Paget’s disease (PD) of the breast.

DISCUSSION

PD of the breast is a rare disorder (accounting for 0.5%-5% of all breast cancers) that is clinically characterized by erythematous, eczematous changes of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC).1-7 PD is almost always unilateral and symptoms include pain, burning, and itching of the nipple, often with bloody nipple discharge.1,3-8

PD can be mistaken for benign skin changes and diagnosed as dermatitis or eczema.3,5 Because such changes often resolve temporarily with the use of topical corticosteroids or no treatment at all,2 diagnosis is often delayed. PD of the breast is associated with underlying ductal carcinoma in 90% to 100% of cases,1,2,5,8 so any skin pathology involving the nipple should be assumed to be PD until proven otherwise.

When no palpable mass is noted on physical exam, DCIS is usually found centrally behind the nipple.1 In addition, lymph node involvement is noted in about 60% of cases.1

Confirm the diagnosis with these tests

Diagnosis of PD of the breast is primarily clinical, with pathologic confirmation. All patients with clinically suspected PD should be evaluated using the following tests to determine the need for biopsy.

Mammography with magnification views of the NAC will show thickening, retraction, or flattening of the nipple, microcalcifications of the retroareolar region, and/or a subareolar mass.3 However, because breast tissue appears normal on mammography in 22% to 71% of patients,1,5 the use of ultrasound and potentially MRI to delineate the extent of disease is warranted.

Ultrasound. While there are no characteristic findings on ultrasound, it can be used to detect dilation of the subareolar ducts, calcification, or a mass.4

MRI has a higher sensitivity for detection of occult disease.2,5 MRI is also useful in the evaluation of axillary node asymmetry, which may indicate nodal involvement.2

Treatment is variable and has not been widely studied

Due to the rarity of PD, there are no randomized studies to point toward optimal treatment strategies.7 Treatment for PD is typically surgical and often involves mastectomy, with or without axillary node dissection.1 Retrospective analyses have demonstrated that central lumpectomy (complete resection of the NAC and underlying disease) with radiation therapy has outcomes similar to mastectomy;2 however, the cosmetic result is sometimes unfavorable.

In cases where there is no palpable mass nor mammographic findings of disease, breast conserving therapy may be considered. If chemotherapy is considered, it should be chosen based on the receptor profile of the disease and subsequent oncotype scoring.

The prognosis for patients with PD who are adequately treated and remain disease free after 5 years is excellent. These patients are likely to have achieved cure.2

Our patient underwent left simple mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy and tissue expander placement. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged home on postoperative Day 1. On final pathology, the 2 sentinel nodes were disease free. The left mastectomy specimen was found to have high-grade DCIS with clear surgical margins. The area of involvement was found to be 3.5 cm × 3 cm in size and had clear skin margins. At follow-up one year later, the patient was doing well with no evidence of disease. She subsequently underwent implant insertion.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the unique progression of undiagnosed PD of the breast. It also highlights the importance of ruling out PD when skin changes involving the nipple are present, despite other possible explanations for those changes. This case in particular was complicated by a proximal history of breastfeeding, which erroneously provided an explanation and false reassurance for the primary care provider and patient.

Due to the common association of PD of the breast with underlying DCIS or invasive cancer, the most important aspect of care is early diagnostic work-up and appropriate referral. Primary care physicians have a unique role in obtaining appropriate early diagnostic tests (including mammogram and ultrasound) and making the necessary referral to a breast specialist in the presence of an abnormal physical exam involving the NAC, even in the absence of a palpable mass. In our patient’s case, punch biopsy of the NAC would have been appropriate at the first signs of friable, erythematous changes.

1. Kollmorgen DR, Varanasi JS, Edge SB, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast: a 33-year experience. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:171-177.

2. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard K, Sarr MG, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:9-18.

3. Sandoval-Leon AC, Drews-Elger K, Gomez-Fernandez CR, et al. Paget’s disease of the nipple. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141:1-12.

4. Soler T, Lerin A, Serrano T, et al. Pigmented paget disease of the breast nipple with underlying infiltrating carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:e54-e57.

5. Trebska-McGowan K, Terracina KP, Takabe K. Update on the surgical management of Paget’s disease. Gland Surg. 2013;2:137-142.

6. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard DK, Sarr MG, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast: a clinical perspective. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386;444-450.

7. Durkan B, Bresee C, Bose S, et al. Paget’s disease of the nipple with parenchymal ductal carcinoma in situ is associated with worse prognosis than Paget’s disease alone. Am Surg. 2013;79:1009-1012.

8. Ward KA, Burton JL. Dermatologic diseases of the breast in young women. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:45-52.

1. Kollmorgen DR, Varanasi JS, Edge SB, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast: a 33-year experience. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:171-177.

2. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard K, Sarr MG, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:9-18.

3. Sandoval-Leon AC, Drews-Elger K, Gomez-Fernandez CR, et al. Paget’s disease of the nipple. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141:1-12.

4. Soler T, Lerin A, Serrano T, et al. Pigmented paget disease of the breast nipple with underlying infiltrating carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:e54-e57.

5. Trebska-McGowan K, Terracina KP, Takabe K. Update on the surgical management of Paget’s disease. Gland Surg. 2013;2:137-142.

6. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard DK, Sarr MG, et al. Paget’s disease of the breast: a clinical perspective. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386;444-450.

7. Durkan B, Bresee C, Bose S, et al. Paget’s disease of the nipple with parenchymal ductal carcinoma in situ is associated with worse prognosis than Paget’s disease alone. Am Surg. 2013;79:1009-1012.

8. Ward KA, Burton JL. Dermatologic diseases of the breast in young women. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:45-52.

Linear Porokeratosis Associated With Multiple Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Lesions of porokeratosis are thought to arise from disordered keratinization, though the exact pathogenesis remains uncertain. At least 5 clinical subtypes of porokeratosis have been identified: porokeratosis of Mibelli, disseminated superficial porokeratosis and disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), linear porokeratosis, punctuate porokeratosis, and porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata (PPPD).1,2 Linear porokeratosis is a rare subtype with a clinical differential diagnosis that includes lichen striatus, linear lichen planus, linear verrucous epidermal nevus, segmental Darier disease, and incontinentia pigmenti.3 Definitive diagnosis of linear porokeratosis is made by histopathologic examination demonstrating a cornoid lamella, defined as a column of parakeratotic cells that lies at 45°to the surface of the epidermis and contains pyknotic basophilic nuclei.4 Patients with linear porokeratosis typically develop lesions along the lines of Blaschko in infancy or childhood.5,6 Among the different subtypes of porokeratosis, linear porokeratosis demonstrates the highest rate of malignant transformation, therefore requiring close clinical observation.7

Case Report

An 83-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic with a large linear plaque on the right leg that had been present since birth. Ten years prior to presentation, a portion of the lesion started to bleed; biopsy of the area was performed by an outside provider demonstrating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which was treated with wide local excision. One year prior to presentation, a separate portion of the plaque was biopsied by an outside provider and another diagnosis of SCC was made.

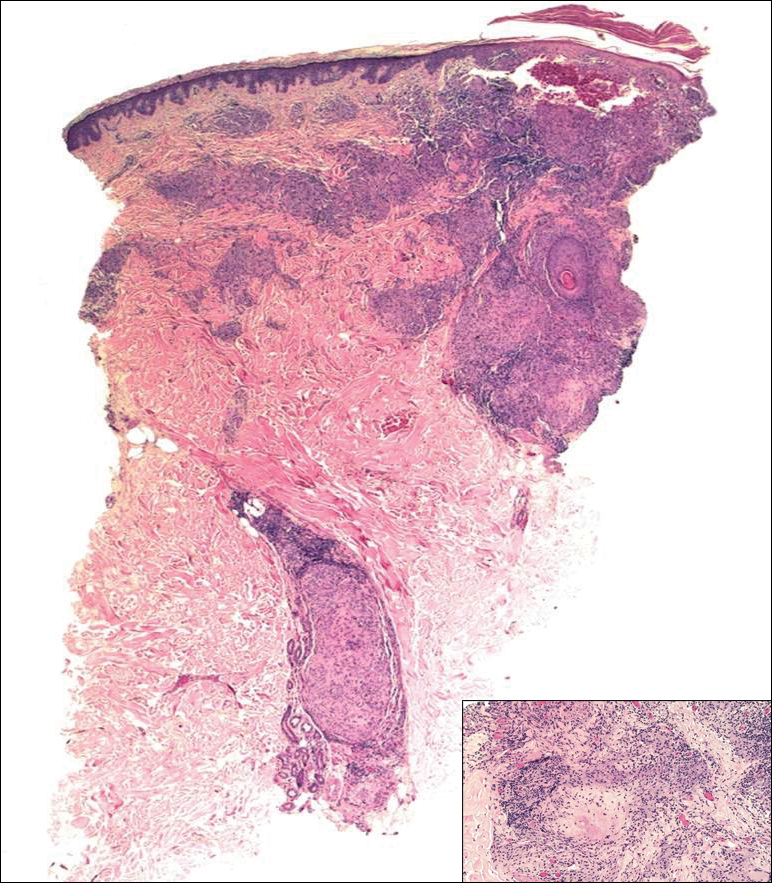

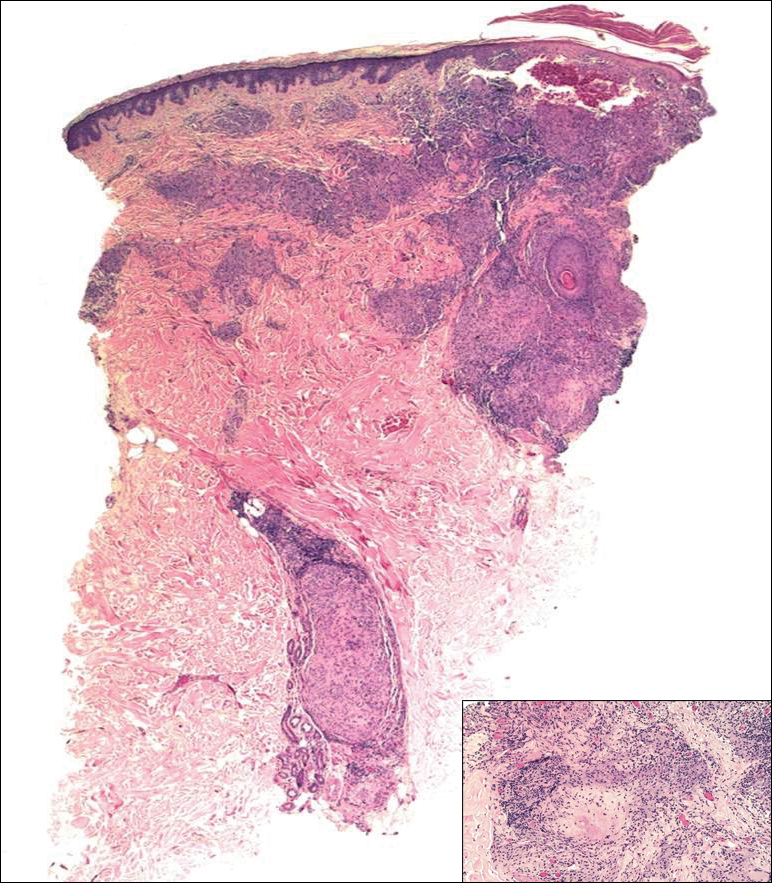

On examination performed during the initial presentation to our clinic, there was a well-demarcated tan to violaceous linear plaque present at the lower buttock and extending along the posterior leg to the skin overlying the Achilles tendon and dorsal aspect of the right foot. Within the plaque, there were areas of atrophy and areas of inflammation, induration, and hyperkeratosis (Figures 1 and 2). Two punch biopsies were performed: one from the edge of the plaque and one from a hyperkeratotic region within the plaque. Histology from the edge of the plaque demonstrated a cornoid lamella, consistent with a porokeratosis (Figure 3), whereas the histology from the hyperkeratotic region demonstrated a lichenoid infiltrate (Figure 4).

Several treatment options directed at the entire lesion were offered to the patient, but she declined these therapies and opted to address only those areas with clinical features of SCC, such as hyperkeratosis, bleeding, and rapid growth. Although biopsies performed by an outside provider were consistent with SCC, it had not been detected on biopsy performed during her initial visit to our clinic.

The patient was educated on the risk associated with her condition and instructed to follow up every 6 months to monitor for the development of SCC.

Comment

Porokeratosis is a disorder of keratinization with at least 5 clinical subtypes that share histologic similarities: porokeratosis of Mibelli, disseminated superficial porokeratosis and DSAP, linear porokeratosis, punctate porokeratosis, and PPPD.1,2 Other less common variants of porokeratosis include porokeratosis ptychotropica (a verrucous variant confined to the perianal area) and congenital unilateral linear porokeratosis.8,9

Linear porokeratosis appears in infancy or childhood with plaques that follow the lines of Blaschko.5,6 Most commonly, it presents unilaterally with annular plaques and linear hyperkeratotic papules that preferentially affect the extremities, though it also may present in a more generalized form or appear in a zosteriform pattern.10,11 Linear porokeratosis affects fewer than 20,000 individuals in the United States and accounts for fewer than 13% of all porokeratosis cases.12,13

Despite its relatively low prevalence, early identification of linear porokeratosis is important due to its high oncogenic potential, with malignant transformation to basal cell carcinoma or, more commonly, SCC reported in 19% of reported cases.1,5,7,14 The malignant transformation rate of linear porokeratosis is reported to be higher than rates seen in other porokeratosis subtypes (9.5%, 7.6%, and 3.4% for PPPD, porokeratosis of Mibelli, and DSAP, respectively).7 The risk of malignant transformation from porokeratosis increases with exposure to ionizing radiation, duration of the lesion, larger or coalescing lesions, and advanced age.7,15,16 Histologic studies have provided support for correlation between lesion size and oncogenic potential, with greater numbers of mitotic cells and more abnormal DNA ploidy seen in larger lesions.17

Histopathology

All subtypes of porokeratosis share certain histopathologic features that aid in the diagnosis of the disorder.18 Identification of the clinically observed hyperkeratotic ridged border or cornoid lamella is the primary means of definitively diagnosing porokeratosis; however, cornoid lamellae may be observed in other conditions, including verruca vulgaris and actinic keratosis.4,14

The cornoid lamella appears as a skewed column of densely packed parakeratotic cells with pyknotic basophilic nuclei extending through the stratum corneum from an epidermal invagination.4 Directly beneath the cornoid lamella, the granular layer is markedly diminished or absent, and cells of the stratum spinosum may demonstrate vacuolar changes or dyskeratosis.4,19 The superficial layer of the cornoid lamella may appear to be more centrifugally located and the cornoid lamella may be seen in several locations throughout the lesion.2,20 The degree of epidermal invagination, which is present under the cornoid lamella, varies by porokeratosis subtype; the central portion of the lesion may contain epidermis that ranges from hyperplastic to atrophic.2 Shumack et al21 noted that histologic changes under the cornoid lamella may include a lichenoid tissue reaction, papillary dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, vacuolar changes, dyskeratosis, and liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer. Because many of these histologic features also can be identified in lichen planus, a biopsy of the edge of lesions of porokeratosis is essential for making the correct diagnosis.

Heritability

Although linear porokeratosis has no identified pattern of inheritance and appears sporadic in onset, reports have described concomitant occurrence of linear porokeratosis and DSAP as well as linear porokeratosis arising in children of parents who have a diagnosis of DSAP.5,18,22,23 Based on these findings, it has been hypothesized that linear porokeratosis may represent a mosaic or segmental form of autosomal-dominant inherited subtypes of porokeratosis, such as DSAP.5 According to this hypothesis, loss of heterozygosity in patients with a DSAP mutation during early embryogenesis leads to proliferation of cells that are homozygous or hemizygous for the underlying mutation along lines of Blaschko.24 It has been suggested that the allelic loss implicated in the development of linear porokeratosis is the first step in a multistage process of carcinogenesis, which may help to explain the higher rates of malignant transformation that can be seen in linear porokeratosis.24

Management

Several treatment options exist for porokeratosis, including cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil with or without adjunctive retinoid treatment, topical imiquimod, CO2 laser, shave and linear excision, curettage, dermabrasion, and oral acitretin for widespread lesions.1,25-29 One case report detailed successful treatment of adult-onset linear porokeratosis with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.30 Treatments for porokeratosis demonstrate variable degrees of success, with the aim of eradicating the clonal population of mutant keratinocytes.2 Additionally, protection from UV radiation should be encouraged, especially in patients who have lesions that occur in areas of high actinic damage.1

Conclusion

We report of a case of linear porokeratosis with associated multiple SCCs that developed within the lesion. Definitive diagnosis of linear porokeratosis is important due to the higher rate of malignant transformation than the rate seen in other porokeratoses. In larger lesions, appropriate sampling and orientation of the pathology specimen is essential for identifying cornoid lamellae, thus allowing for appropriate follow-up and management. Several treatment options are available, though evidence for the effectiveness of any particular therapy is lacking. Research has shed light on possible genetic and molecular abnormalities in linear porokeratosis, but the exact pathogenesis of the disorder remains unclear.

- Curkova AK, Hegyi J, Kozub P, et al. A case of linear porokeratosis treated with photodynamic therapy with confocal microscopy surveillance. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:144-147.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Wade TR, Ackerman AB. Cornoid lamellation. a histologic reaction pattern. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:5-15.

- Curnow P, Foley P, Baker C. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas complicating linear porokeratosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:136-139.

- Rahbari H, Cordero AA, Mehregan AH. Linear porokeratosis. a distinctive clinical variant of porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:526-528.

- Sasson M, Krain AD. Porokeratosis and cutaneous malignancy. a review. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:339-342.

- Yeo J, Winhoven S, Tallon B. Porokeratosis ptychotropica: a rare and evolving variant of porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:1042-1047.

- Scola N, Skrygan M, Wieland U, et al. Altered gene expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from congenital unilateral linear porokeratosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:781-785.

- Sertznig P, von Felbert V, Megahed M. Porokeratosis: present concepts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:404-412.

- Goldner R. Zosteriform porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:425-426.

- Malhotra SK, Puri KJ, Goyal T, et al. Linear porokeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:15.

- Leow YH, Soon YH, Tham SN. A report of 31 cases of porokeratosis at the National Skin Centre. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:837-841.

- Vivas AC, Maderal AD, Kirsner RS. Giant ulcerating squamous cell carcinoma arising from linear porokeratosis: a case study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58:18-20.

- Arranz-Salas I, Sanz-Trelles A, Ojeda DB. p53 alterations in porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:455-458.

- Otsuka F, Someya T, Ishibashi Y. Porokeratosis and malignant skin tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117:55-60.

- Otsuka F, Umebayashi Y, Watanabe S, et al. Porokeratosis large skin lesions are susceptible to skin cancer development: histological and cytological explanation for the susceptibility. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1993;119:395-400.

- Lohrer R, Neumann-Acikel A, Eming R, et al. A case of linear porokeratosis superimposed on disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2010;2:130-134.

- Biswas A. Cornoid lamellation revisited: apropos of porokeratosis with emphasis on unusual clinicopathological variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:145-155.

- Reed RJ, Leone P. Porokeratosis—a mutant clonal keratosis of the epidermis. I. histogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:340-347.

- Shumack S, Commens C, Kossard S. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. a histological review of 61 cases with particular reference to lymphocytic inflammation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:26-31.

- Murase J, Gilliam AC. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis co-existing with linear and verrucous porokeratosis in an elderly woman: update on the genetics and clinical expression of porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:886-891.

- Commens CA, Shumack SP. Linear porokeratosis in two families with disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1987;4:209-214.

- Happle R. Cancer proneness of linear porokeratosis may be explained by allelic loss. Dermatology. 1997;195:20-25.

- Rabbin PE, Baldwin HE. Treatment of porokeratosis of Mibelli with CO2 laser vaporization versus surgical excision with split-thickness skin graft. a comparison. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:199-202.

- Spencer JM, Katz BE. Successful treatment of porokeratosis of Mibelli with diamond fraise dermabrasion. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1187-1188.

- Venkatarajan S, LeLeux TM, Yang D, et al. Porokeratosis of Mibelli: successful treatment with 5 percent topical imiquimod and topical 5 percent 5-fluorouracil. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:10.

- McDonald SG, Peterka ES. Porokeratosis (Mibelli): treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:107-110.

- Shumack SP, Commens CA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a clinical study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:1015-1022.

- Parks AC, Conner KJ, Armstrong CA. Long-term clearance of linear porokeratosis with tacrolimus, 0.1%, ointment. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:194-196.

Lesions of porokeratosis are thought to arise from disordered keratinization, though the exact pathogenesis remains uncertain. At least 5 clinical subtypes of porokeratosis have been identified: porokeratosis of Mibelli, disseminated superficial porokeratosis and disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), linear porokeratosis, punctuate porokeratosis, and porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata (PPPD).1,2 Linear porokeratosis is a rare subtype with a clinical differential diagnosis that includes lichen striatus, linear lichen planus, linear verrucous epidermal nevus, segmental Darier disease, and incontinentia pigmenti.3 Definitive diagnosis of linear porokeratosis is made by histopathologic examination demonstrating a cornoid lamella, defined as a column of parakeratotic cells that lies at 45°to the surface of the epidermis and contains pyknotic basophilic nuclei.4 Patients with linear porokeratosis typically develop lesions along the lines of Blaschko in infancy or childhood.5,6 Among the different subtypes of porokeratosis, linear porokeratosis demonstrates the highest rate of malignant transformation, therefore requiring close clinical observation.7

Case Report

An 83-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic with a large linear plaque on the right leg that had been present since birth. Ten years prior to presentation, a portion of the lesion started to bleed; biopsy of the area was performed by an outside provider demonstrating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which was treated with wide local excision. One year prior to presentation, a separate portion of the plaque was biopsied by an outside provider and another diagnosis of SCC was made.

On examination performed during the initial presentation to our clinic, there was a well-demarcated tan to violaceous linear plaque present at the lower buttock and extending along the posterior leg to the skin overlying the Achilles tendon and dorsal aspect of the right foot. Within the plaque, there were areas of atrophy and areas of inflammation, induration, and hyperkeratosis (Figures 1 and 2). Two punch biopsies were performed: one from the edge of the plaque and one from a hyperkeratotic region within the plaque. Histology from the edge of the plaque demonstrated a cornoid lamella, consistent with a porokeratosis (Figure 3), whereas the histology from the hyperkeratotic region demonstrated a lichenoid infiltrate (Figure 4).

Several treatment options directed at the entire lesion were offered to the patient, but she declined these therapies and opted to address only those areas with clinical features of SCC, such as hyperkeratosis, bleeding, and rapid growth. Although biopsies performed by an outside provider were consistent with SCC, it had not been detected on biopsy performed during her initial visit to our clinic.

The patient was educated on the risk associated with her condition and instructed to follow up every 6 months to monitor for the development of SCC.

Comment

Porokeratosis is a disorder of keratinization with at least 5 clinical subtypes that share histologic similarities: porokeratosis of Mibelli, disseminated superficial porokeratosis and DSAP, linear porokeratosis, punctate porokeratosis, and PPPD.1,2 Other less common variants of porokeratosis include porokeratosis ptychotropica (a verrucous variant confined to the perianal area) and congenital unilateral linear porokeratosis.8,9

Linear porokeratosis appears in infancy or childhood with plaques that follow the lines of Blaschko.5,6 Most commonly, it presents unilaterally with annular plaques and linear hyperkeratotic papules that preferentially affect the extremities, though it also may present in a more generalized form or appear in a zosteriform pattern.10,11 Linear porokeratosis affects fewer than 20,000 individuals in the United States and accounts for fewer than 13% of all porokeratosis cases.12,13

Despite its relatively low prevalence, early identification of linear porokeratosis is important due to its high oncogenic potential, with malignant transformation to basal cell carcinoma or, more commonly, SCC reported in 19% of reported cases.1,5,7,14 The malignant transformation rate of linear porokeratosis is reported to be higher than rates seen in other porokeratosis subtypes (9.5%, 7.6%, and 3.4% for PPPD, porokeratosis of Mibelli, and DSAP, respectively).7 The risk of malignant transformation from porokeratosis increases with exposure to ionizing radiation, duration of the lesion, larger or coalescing lesions, and advanced age.7,15,16 Histologic studies have provided support for correlation between lesion size and oncogenic potential, with greater numbers of mitotic cells and more abnormal DNA ploidy seen in larger lesions.17

Histopathology

All subtypes of porokeratosis share certain histopathologic features that aid in the diagnosis of the disorder.18 Identification of the clinically observed hyperkeratotic ridged border or cornoid lamella is the primary means of definitively diagnosing porokeratosis; however, cornoid lamellae may be observed in other conditions, including verruca vulgaris and actinic keratosis.4,14

The cornoid lamella appears as a skewed column of densely packed parakeratotic cells with pyknotic basophilic nuclei extending through the stratum corneum from an epidermal invagination.4 Directly beneath the cornoid lamella, the granular layer is markedly diminished or absent, and cells of the stratum spinosum may demonstrate vacuolar changes or dyskeratosis.4,19 The superficial layer of the cornoid lamella may appear to be more centrifugally located and the cornoid lamella may be seen in several locations throughout the lesion.2,20 The degree of epidermal invagination, which is present under the cornoid lamella, varies by porokeratosis subtype; the central portion of the lesion may contain epidermis that ranges from hyperplastic to atrophic.2 Shumack et al21 noted that histologic changes under the cornoid lamella may include a lichenoid tissue reaction, papillary dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, vacuolar changes, dyskeratosis, and liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer. Because many of these histologic features also can be identified in lichen planus, a biopsy of the edge of lesions of porokeratosis is essential for making the correct diagnosis.

Heritability

Although linear porokeratosis has no identified pattern of inheritance and appears sporadic in onset, reports have described concomitant occurrence of linear porokeratosis and DSAP as well as linear porokeratosis arising in children of parents who have a diagnosis of DSAP.5,18,22,23 Based on these findings, it has been hypothesized that linear porokeratosis may represent a mosaic or segmental form of autosomal-dominant inherited subtypes of porokeratosis, such as DSAP.5 According to this hypothesis, loss of heterozygosity in patients with a DSAP mutation during early embryogenesis leads to proliferation of cells that are homozygous or hemizygous for the underlying mutation along lines of Blaschko.24 It has been suggested that the allelic loss implicated in the development of linear porokeratosis is the first step in a multistage process of carcinogenesis, which may help to explain the higher rates of malignant transformation that can be seen in linear porokeratosis.24

Management

Several treatment options exist for porokeratosis, including cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil with or without adjunctive retinoid treatment, topical imiquimod, CO2 laser, shave and linear excision, curettage, dermabrasion, and oral acitretin for widespread lesions.1,25-29 One case report detailed successful treatment of adult-onset linear porokeratosis with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.30 Treatments for porokeratosis demonstrate variable degrees of success, with the aim of eradicating the clonal population of mutant keratinocytes.2 Additionally, protection from UV radiation should be encouraged, especially in patients who have lesions that occur in areas of high actinic damage.1

Conclusion

We report of a case of linear porokeratosis with associated multiple SCCs that developed within the lesion. Definitive diagnosis of linear porokeratosis is important due to the higher rate of malignant transformation than the rate seen in other porokeratoses. In larger lesions, appropriate sampling and orientation of the pathology specimen is essential for identifying cornoid lamellae, thus allowing for appropriate follow-up and management. Several treatment options are available, though evidence for the effectiveness of any particular therapy is lacking. Research has shed light on possible genetic and molecular abnormalities in linear porokeratosis, but the exact pathogenesis of the disorder remains unclear.

Lesions of porokeratosis are thought to arise from disordered keratinization, though the exact pathogenesis remains uncertain. At least 5 clinical subtypes of porokeratosis have been identified: porokeratosis of Mibelli, disseminated superficial porokeratosis and disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), linear porokeratosis, punctuate porokeratosis, and porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata (PPPD).1,2 Linear porokeratosis is a rare subtype with a clinical differential diagnosis that includes lichen striatus, linear lichen planus, linear verrucous epidermal nevus, segmental Darier disease, and incontinentia pigmenti.3 Definitive diagnosis of linear porokeratosis is made by histopathologic examination demonstrating a cornoid lamella, defined as a column of parakeratotic cells that lies at 45°to the surface of the epidermis and contains pyknotic basophilic nuclei.4 Patients with linear porokeratosis typically develop lesions along the lines of Blaschko in infancy or childhood.5,6 Among the different subtypes of porokeratosis, linear porokeratosis demonstrates the highest rate of malignant transformation, therefore requiring close clinical observation.7

Case Report

An 83-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic with a large linear plaque on the right leg that had been present since birth. Ten years prior to presentation, a portion of the lesion started to bleed; biopsy of the area was performed by an outside provider demonstrating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which was treated with wide local excision. One year prior to presentation, a separate portion of the plaque was biopsied by an outside provider and another diagnosis of SCC was made.

On examination performed during the initial presentation to our clinic, there was a well-demarcated tan to violaceous linear plaque present at the lower buttock and extending along the posterior leg to the skin overlying the Achilles tendon and dorsal aspect of the right foot. Within the plaque, there were areas of atrophy and areas of inflammation, induration, and hyperkeratosis (Figures 1 and 2). Two punch biopsies were performed: one from the edge of the plaque and one from a hyperkeratotic region within the plaque. Histology from the edge of the plaque demonstrated a cornoid lamella, consistent with a porokeratosis (Figure 3), whereas the histology from the hyperkeratotic region demonstrated a lichenoid infiltrate (Figure 4).

Several treatment options directed at the entire lesion were offered to the patient, but she declined these therapies and opted to address only those areas with clinical features of SCC, such as hyperkeratosis, bleeding, and rapid growth. Although biopsies performed by an outside provider were consistent with SCC, it had not been detected on biopsy performed during her initial visit to our clinic.

The patient was educated on the risk associated with her condition and instructed to follow up every 6 months to monitor for the development of SCC.

Comment

Porokeratosis is a disorder of keratinization with at least 5 clinical subtypes that share histologic similarities: porokeratosis of Mibelli, disseminated superficial porokeratosis and DSAP, linear porokeratosis, punctate porokeratosis, and PPPD.1,2 Other less common variants of porokeratosis include porokeratosis ptychotropica (a verrucous variant confined to the perianal area) and congenital unilateral linear porokeratosis.8,9

Linear porokeratosis appears in infancy or childhood with plaques that follow the lines of Blaschko.5,6 Most commonly, it presents unilaterally with annular plaques and linear hyperkeratotic papules that preferentially affect the extremities, though it also may present in a more generalized form or appear in a zosteriform pattern.10,11 Linear porokeratosis affects fewer than 20,000 individuals in the United States and accounts for fewer than 13% of all porokeratosis cases.12,13

Despite its relatively low prevalence, early identification of linear porokeratosis is important due to its high oncogenic potential, with malignant transformation to basal cell carcinoma or, more commonly, SCC reported in 19% of reported cases.1,5,7,14 The malignant transformation rate of linear porokeratosis is reported to be higher than rates seen in other porokeratosis subtypes (9.5%, 7.6%, and 3.4% for PPPD, porokeratosis of Mibelli, and DSAP, respectively).7 The risk of malignant transformation from porokeratosis increases with exposure to ionizing radiation, duration of the lesion, larger or coalescing lesions, and advanced age.7,15,16 Histologic studies have provided support for correlation between lesion size and oncogenic potential, with greater numbers of mitotic cells and more abnormal DNA ploidy seen in larger lesions.17

Histopathology

All subtypes of porokeratosis share certain histopathologic features that aid in the diagnosis of the disorder.18 Identification of the clinically observed hyperkeratotic ridged border or cornoid lamella is the primary means of definitively diagnosing porokeratosis; however, cornoid lamellae may be observed in other conditions, including verruca vulgaris and actinic keratosis.4,14

The cornoid lamella appears as a skewed column of densely packed parakeratotic cells with pyknotic basophilic nuclei extending through the stratum corneum from an epidermal invagination.4 Directly beneath the cornoid lamella, the granular layer is markedly diminished or absent, and cells of the stratum spinosum may demonstrate vacuolar changes or dyskeratosis.4,19 The superficial layer of the cornoid lamella may appear to be more centrifugally located and the cornoid lamella may be seen in several locations throughout the lesion.2,20 The degree of epidermal invagination, which is present under the cornoid lamella, varies by porokeratosis subtype; the central portion of the lesion may contain epidermis that ranges from hyperplastic to atrophic.2 Shumack et al21 noted that histologic changes under the cornoid lamella may include a lichenoid tissue reaction, papillary dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, vacuolar changes, dyskeratosis, and liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer. Because many of these histologic features also can be identified in lichen planus, a biopsy of the edge of lesions of porokeratosis is essential for making the correct diagnosis.

Heritability

Although linear porokeratosis has no identified pattern of inheritance and appears sporadic in onset, reports have described concomitant occurrence of linear porokeratosis and DSAP as well as linear porokeratosis arising in children of parents who have a diagnosis of DSAP.5,18,22,23 Based on these findings, it has been hypothesized that linear porokeratosis may represent a mosaic or segmental form of autosomal-dominant inherited subtypes of porokeratosis, such as DSAP.5 According to this hypothesis, loss of heterozygosity in patients with a DSAP mutation during early embryogenesis leads to proliferation of cells that are homozygous or hemizygous for the underlying mutation along lines of Blaschko.24 It has been suggested that the allelic loss implicated in the development of linear porokeratosis is the first step in a multistage process of carcinogenesis, which may help to explain the higher rates of malignant transformation that can be seen in linear porokeratosis.24

Management

Several treatment options exist for porokeratosis, including cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil with or without adjunctive retinoid treatment, topical imiquimod, CO2 laser, shave and linear excision, curettage, dermabrasion, and oral acitretin for widespread lesions.1,25-29 One case report detailed successful treatment of adult-onset linear porokeratosis with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.30 Treatments for porokeratosis demonstrate variable degrees of success, with the aim of eradicating the clonal population of mutant keratinocytes.2 Additionally, protection from UV radiation should be encouraged, especially in patients who have lesions that occur in areas of high actinic damage.1

Conclusion

We report of a case of linear porokeratosis with associated multiple SCCs that developed within the lesion. Definitive diagnosis of linear porokeratosis is important due to the higher rate of malignant transformation than the rate seen in other porokeratoses. In larger lesions, appropriate sampling and orientation of the pathology specimen is essential for identifying cornoid lamellae, thus allowing for appropriate follow-up and management. Several treatment options are available, though evidence for the effectiveness of any particular therapy is lacking. Research has shed light on possible genetic and molecular abnormalities in linear porokeratosis, but the exact pathogenesis of the disorder remains unclear.

- Curkova AK, Hegyi J, Kozub P, et al. A case of linear porokeratosis treated with photodynamic therapy with confocal microscopy surveillance. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:144-147.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Wade TR, Ackerman AB. Cornoid lamellation. a histologic reaction pattern. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:5-15.

- Curnow P, Foley P, Baker C. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas complicating linear porokeratosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:136-139.

- Rahbari H, Cordero AA, Mehregan AH. Linear porokeratosis. a distinctive clinical variant of porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:526-528.

- Sasson M, Krain AD. Porokeratosis and cutaneous malignancy. a review. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:339-342.

- Yeo J, Winhoven S, Tallon B. Porokeratosis ptychotropica: a rare and evolving variant of porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:1042-1047.

- Scola N, Skrygan M, Wieland U, et al. Altered gene expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from congenital unilateral linear porokeratosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:781-785.

- Sertznig P, von Felbert V, Megahed M. Porokeratosis: present concepts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:404-412.

- Goldner R. Zosteriform porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:425-426.

- Malhotra SK, Puri KJ, Goyal T, et al. Linear porokeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:15.

- Leow YH, Soon YH, Tham SN. A report of 31 cases of porokeratosis at the National Skin Centre. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:837-841.

- Vivas AC, Maderal AD, Kirsner RS. Giant ulcerating squamous cell carcinoma arising from linear porokeratosis: a case study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58:18-20.

- Arranz-Salas I, Sanz-Trelles A, Ojeda DB. p53 alterations in porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:455-458.

- Otsuka F, Someya T, Ishibashi Y. Porokeratosis and malignant skin tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117:55-60.

- Otsuka F, Umebayashi Y, Watanabe S, et al. Porokeratosis large skin lesions are susceptible to skin cancer development: histological and cytological explanation for the susceptibility. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1993;119:395-400.

- Lohrer R, Neumann-Acikel A, Eming R, et al. A case of linear porokeratosis superimposed on disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2010;2:130-134.

- Biswas A. Cornoid lamellation revisited: apropos of porokeratosis with emphasis on unusual clinicopathological variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:145-155.

- Reed RJ, Leone P. Porokeratosis—a mutant clonal keratosis of the epidermis. I. histogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:340-347.

- Shumack S, Commens C, Kossard S. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. a histological review of 61 cases with particular reference to lymphocytic inflammation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:26-31.

- Murase J, Gilliam AC. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis co-existing with linear and verrucous porokeratosis in an elderly woman: update on the genetics and clinical expression of porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:886-891.

- Commens CA, Shumack SP. Linear porokeratosis in two families with disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1987;4:209-214.

- Happle R. Cancer proneness of linear porokeratosis may be explained by allelic loss. Dermatology. 1997;195:20-25.

- Rabbin PE, Baldwin HE. Treatment of porokeratosis of Mibelli with CO2 laser vaporization versus surgical excision with split-thickness skin graft. a comparison. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:199-202.

- Spencer JM, Katz BE. Successful treatment of porokeratosis of Mibelli with diamond fraise dermabrasion. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1187-1188.

- Venkatarajan S, LeLeux TM, Yang D, et al. Porokeratosis of Mibelli: successful treatment with 5 percent topical imiquimod and topical 5 percent 5-fluorouracil. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:10.

- McDonald SG, Peterka ES. Porokeratosis (Mibelli): treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:107-110.

- Shumack SP, Commens CA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a clinical study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:1015-1022.

- Parks AC, Conner KJ, Armstrong CA. Long-term clearance of linear porokeratosis with tacrolimus, 0.1%, ointment. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:194-196.

- Curkova AK, Hegyi J, Kozub P, et al. A case of linear porokeratosis treated with photodynamic therapy with confocal microscopy surveillance. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:144-147.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Wade TR, Ackerman AB. Cornoid lamellation. a histologic reaction pattern. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:5-15.