User login

Atypical Disseminated Herpes Zoster: Management Guidelines in Immunocompromised Patients

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

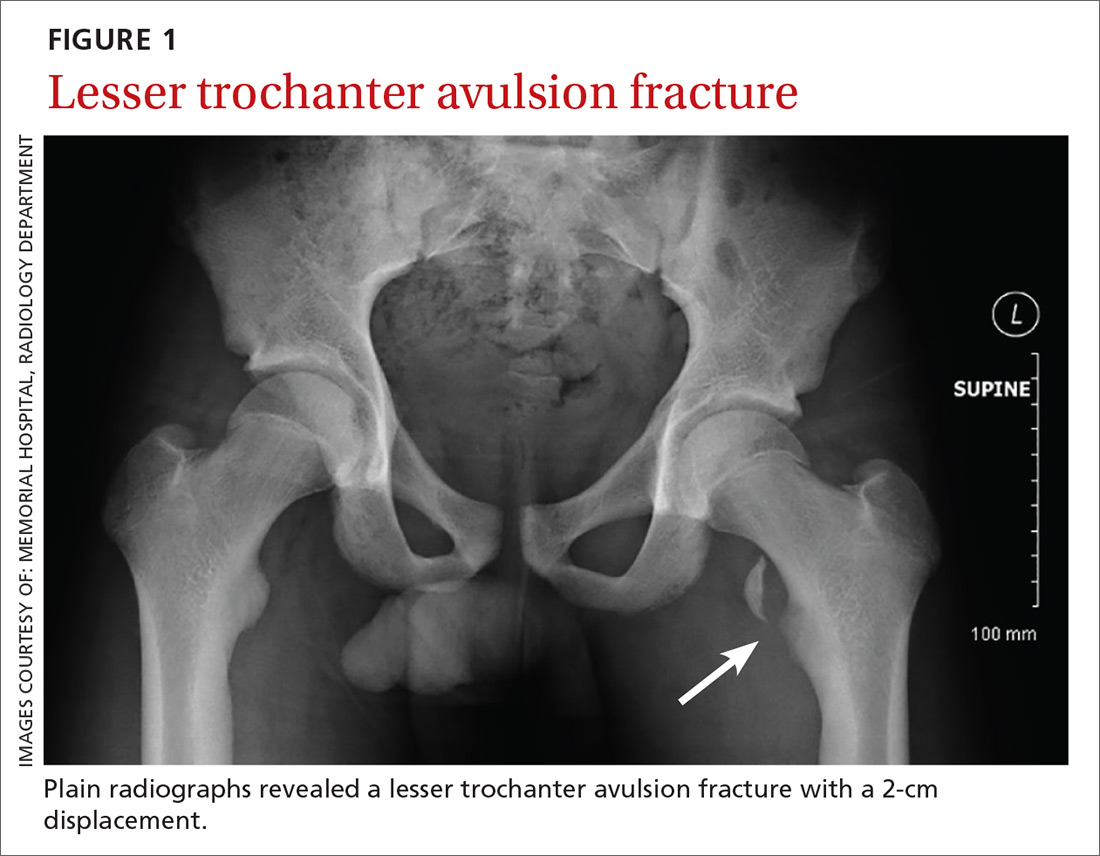

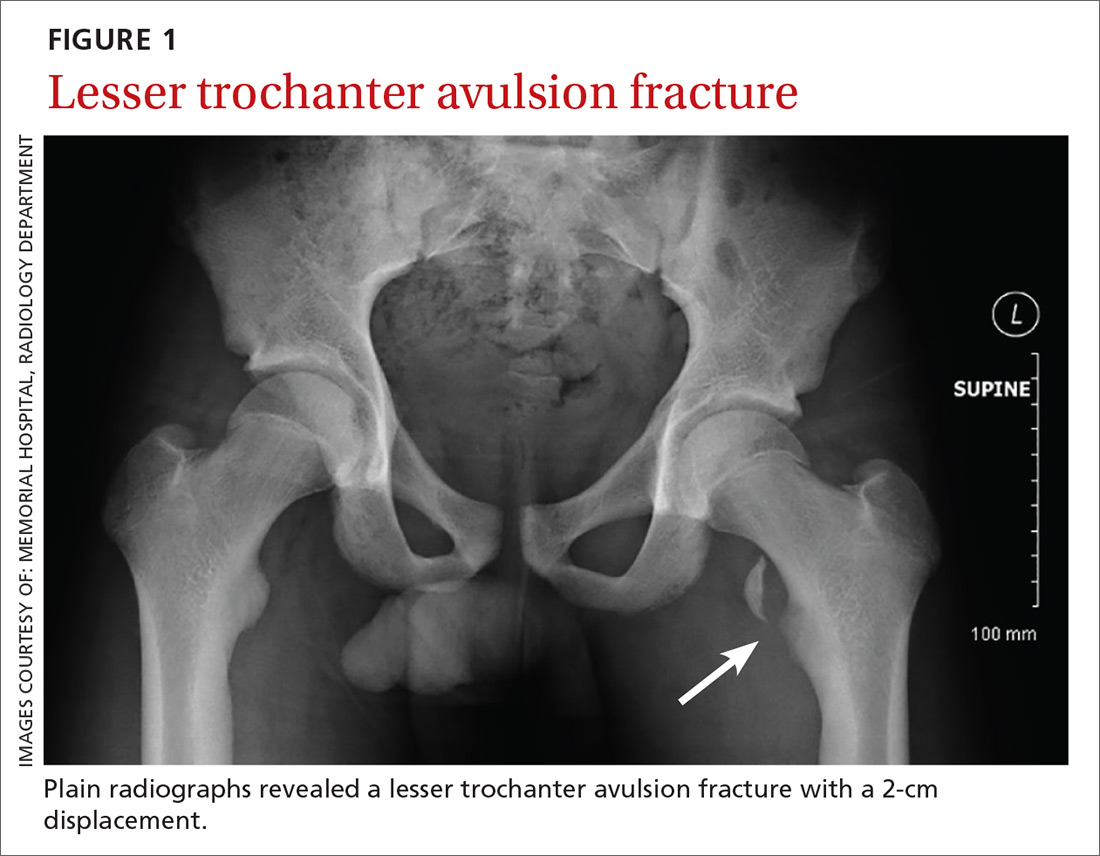

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

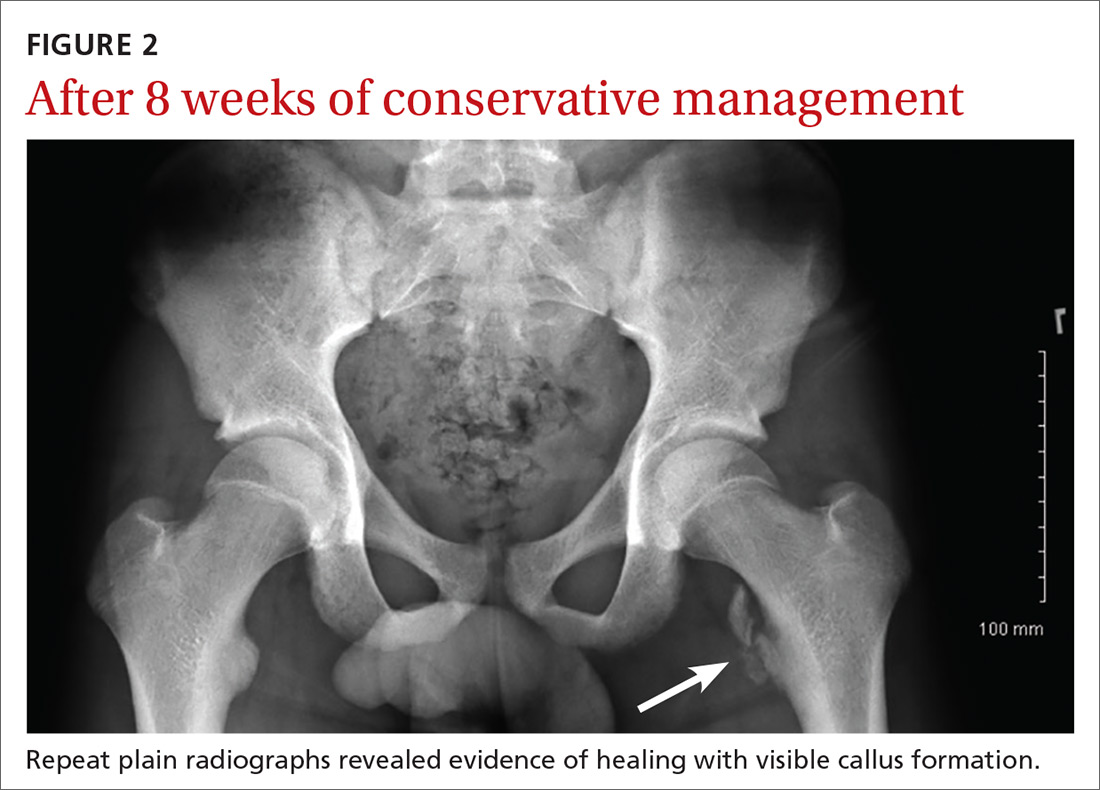

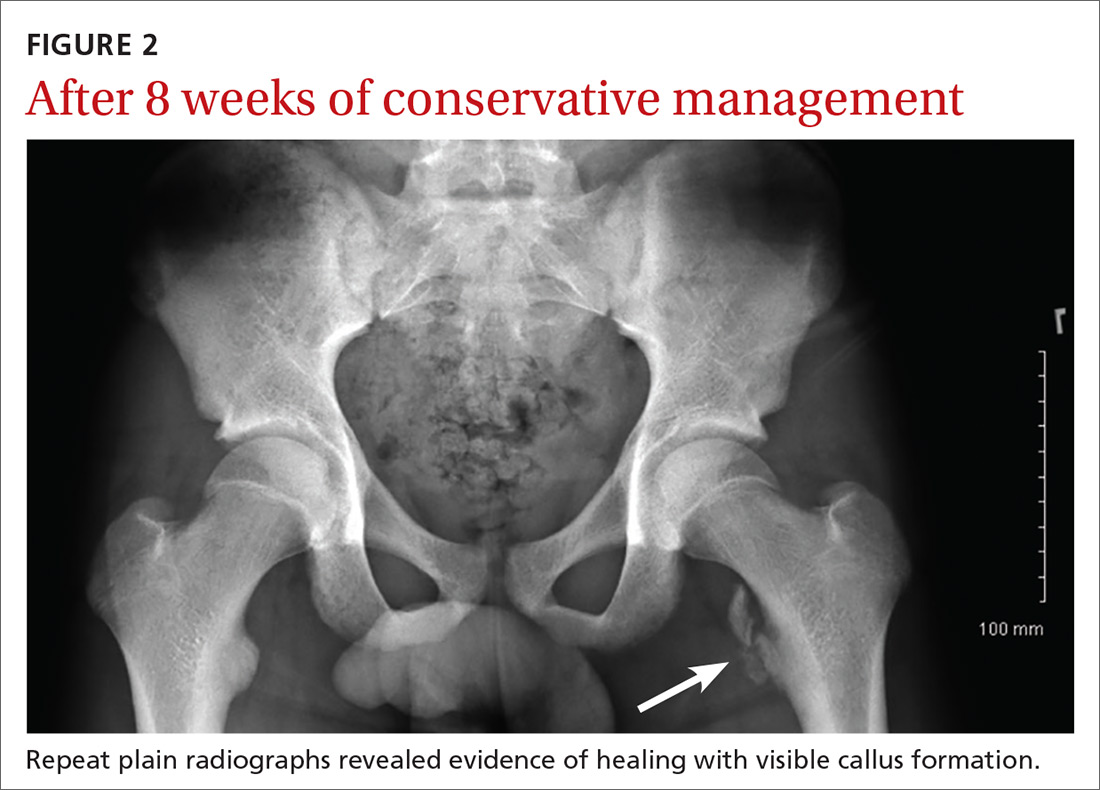

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

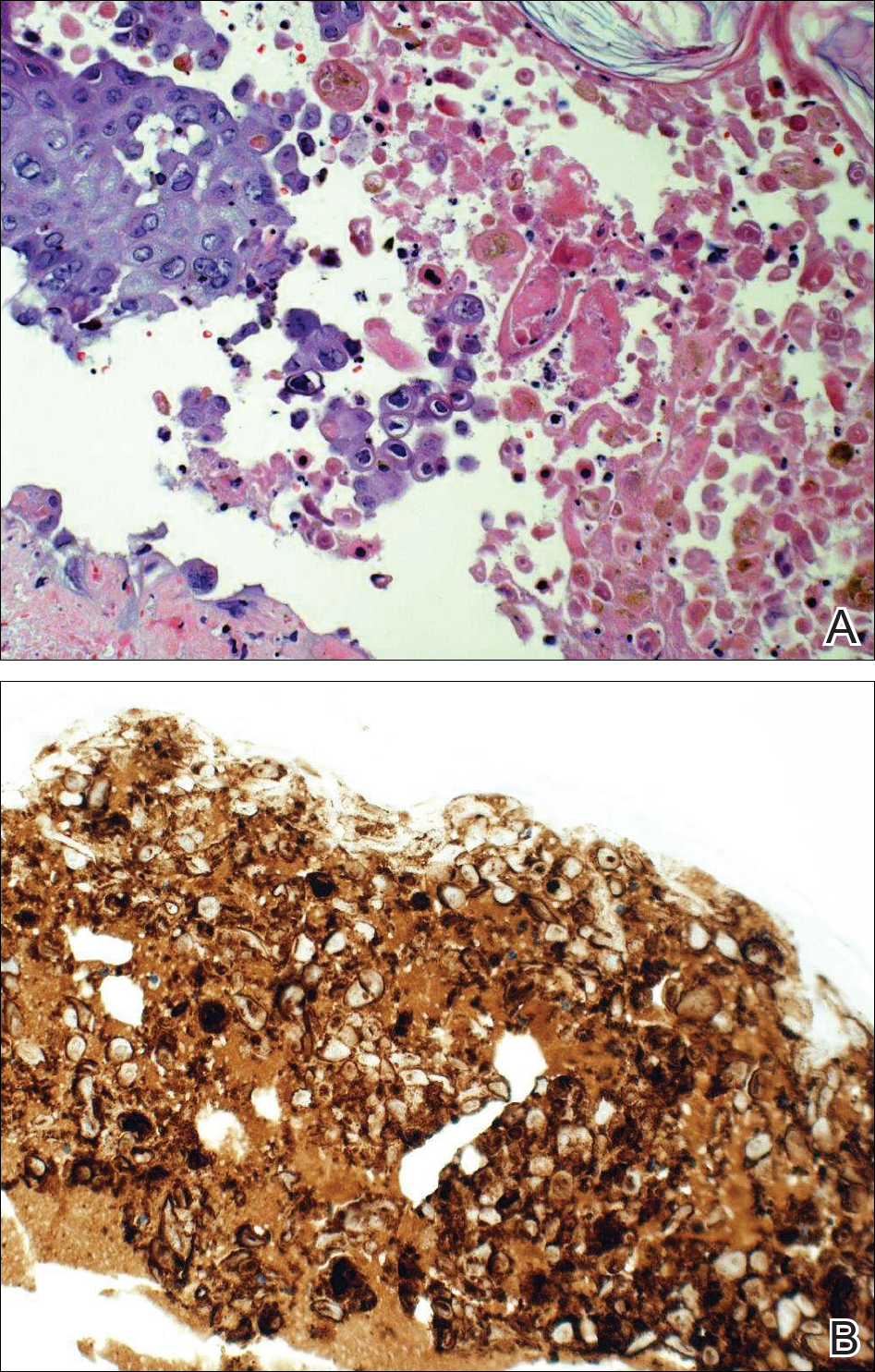

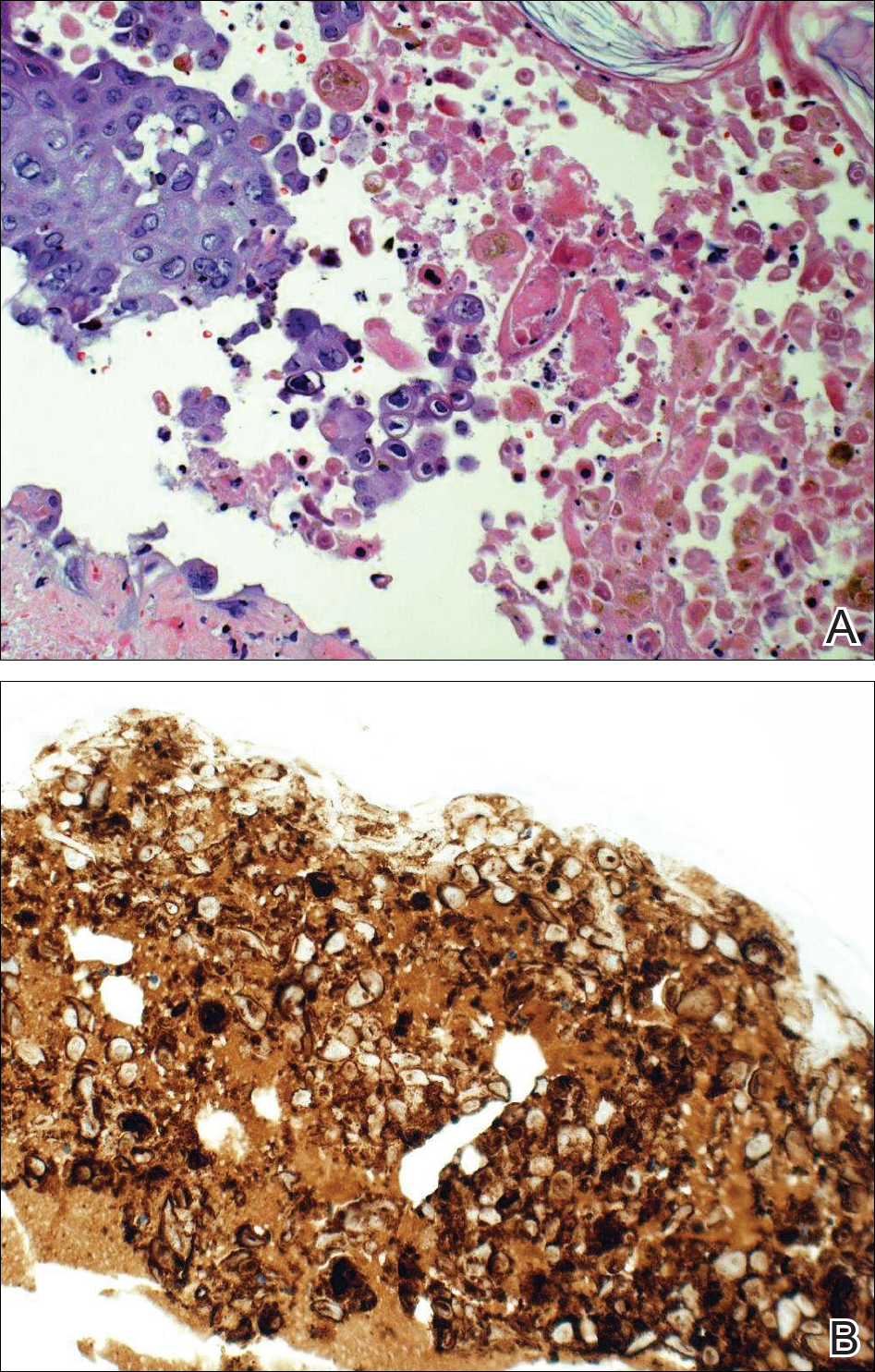

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

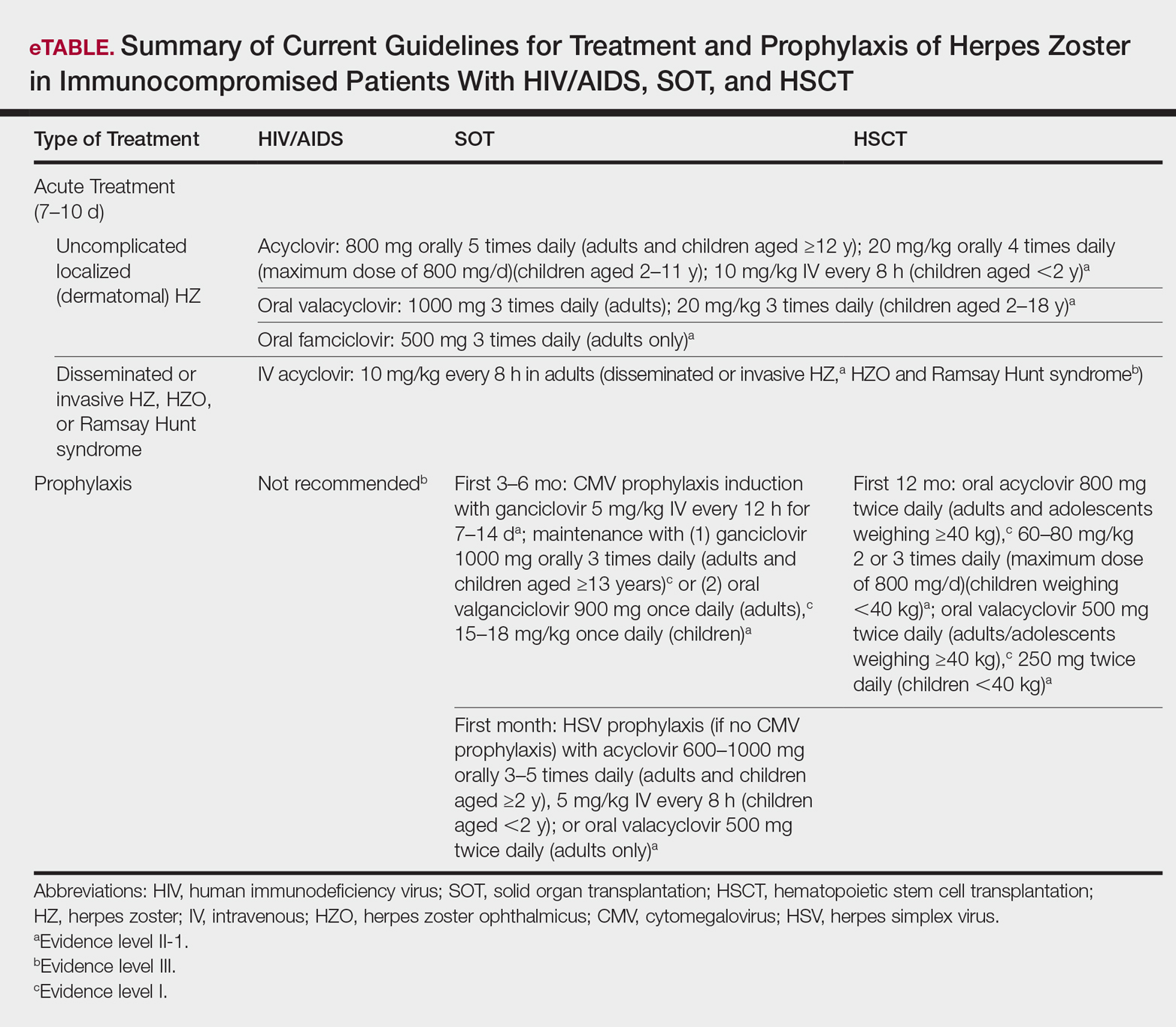

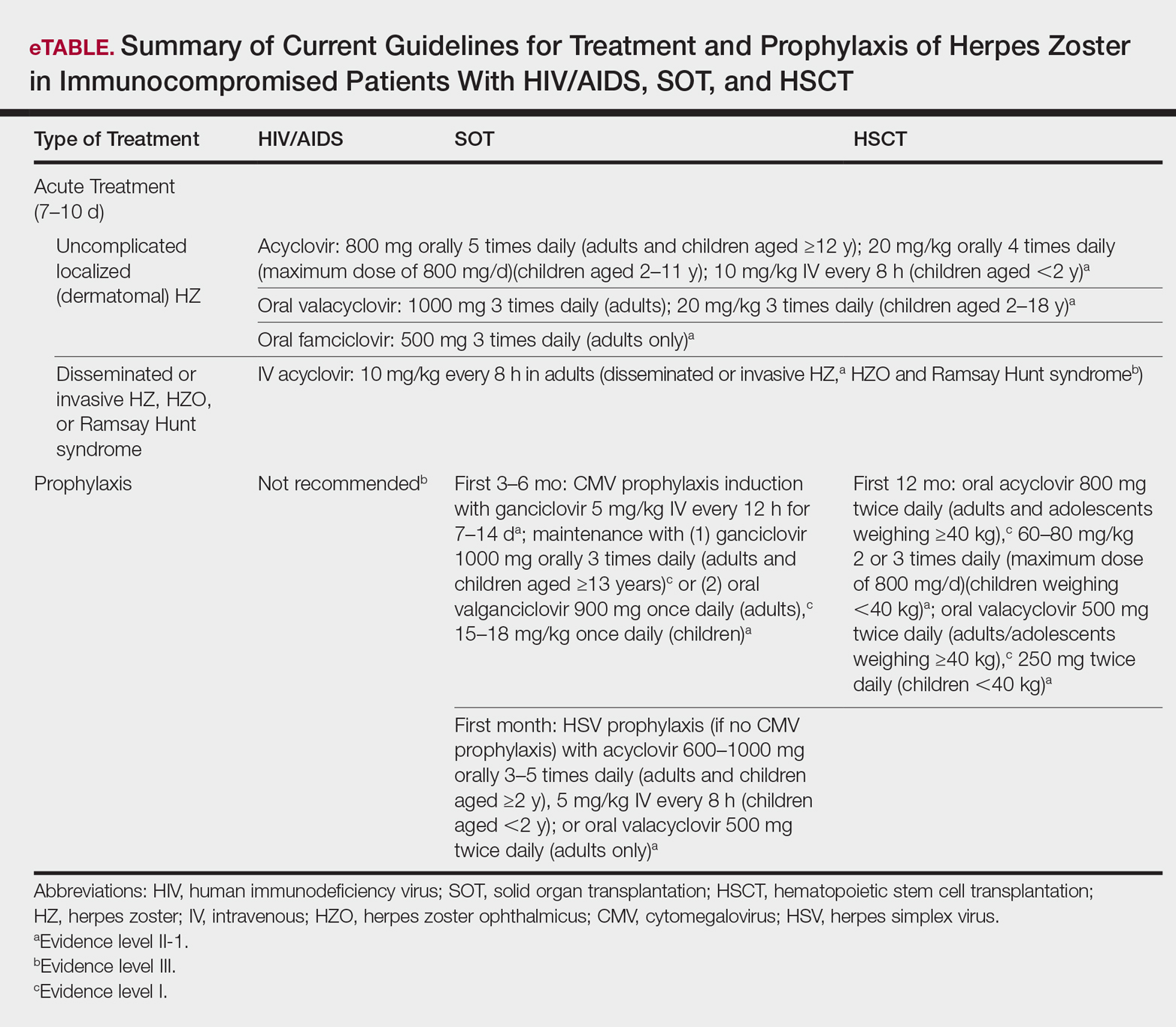

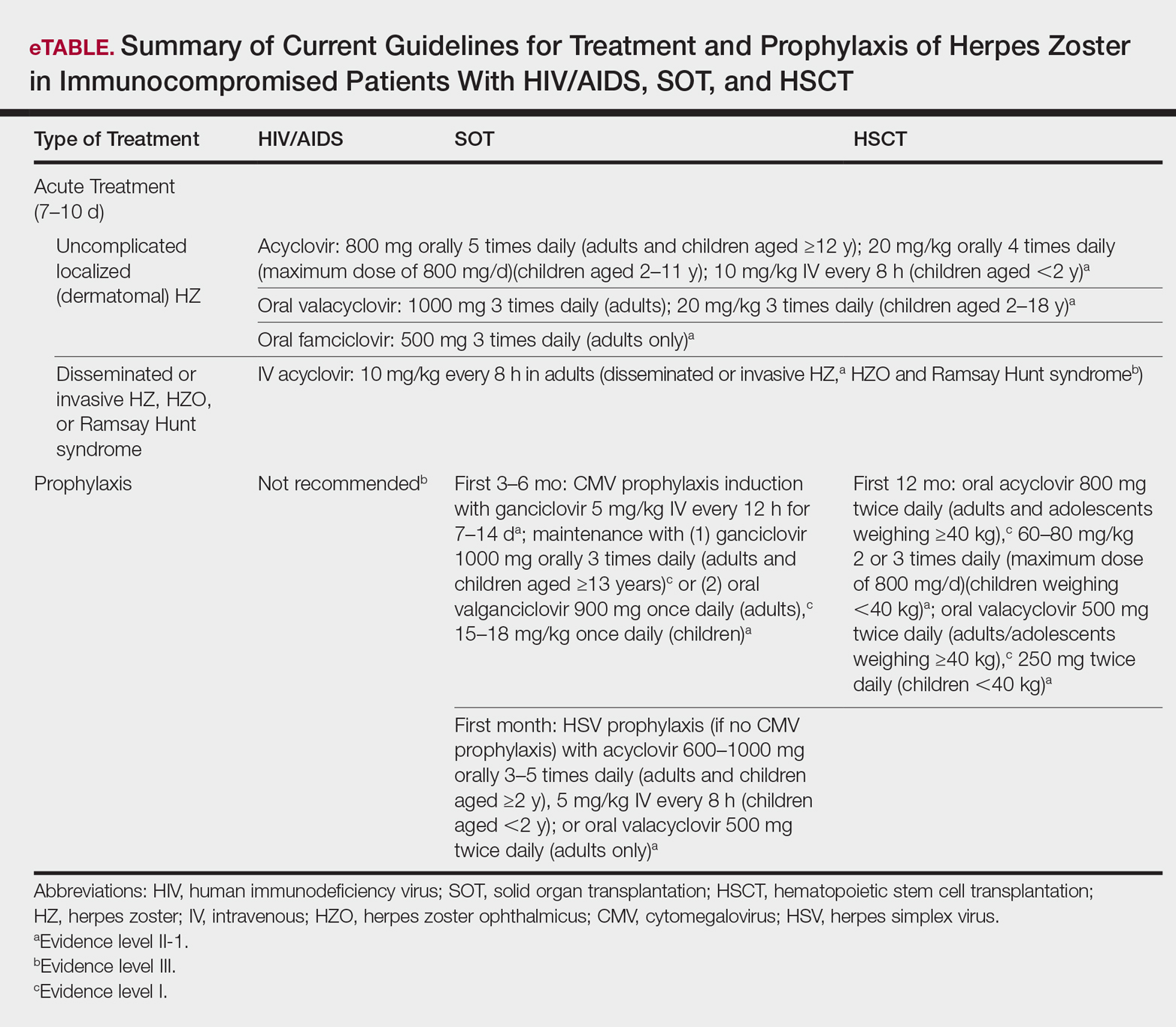

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

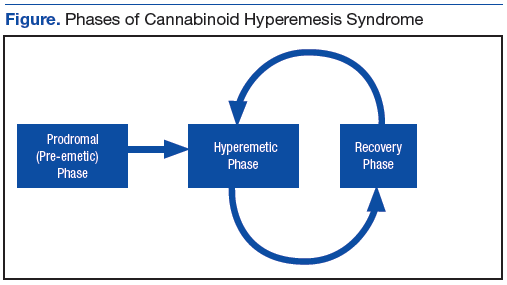

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

Practice Points

- Clinician awareness of management guidelines for the prevention and treatment of varicella-zoster virus infection in immunocompromised individuals is critical to minimize the risk for disease and associated morbidity.

- Antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following solid organ transplantation or 1 year following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for herpes zoster.

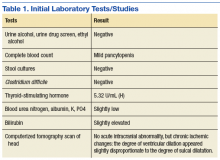

Ulcerative Sarcoidosis: A Prototypical Presentation and Review

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that primarily affects the lungs and lymphatic system but also may involve the skin, eyes, liver, spleen, muscles, bones, and nervous system.1 Cutaneous symptoms of sarcoidosis occur in approximately 25% of patients and are classified as specific and nonspecific, with specific lesions demonstrating noncaseating granuloma formation, which is typical of sarcoidosis.2 Nonspecific lesions primarily include erythema nodosum and calcinosis cutis. Specific lesions commonly present as reddish brown infiltrated plaques that may be annular, polycyclic, or serpiginous.1,3 They also may appear as yellowish brown or violaceous maculopapular lesions. However, specific lesions may present in a wide variety of morphologies, most often papules, nodules, subcutaneous infiltrates, and lupus pernio.4 Additionally, atypical cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis include erythroderma; scarring alopecia; nail dystrophy; and verrucous, ichthyosiform, psoriasiform, hypopigmented, or ulcerative skin lesions.3-5 Among these many potential clinical presentations, ulcerative sarcoidosis is quite uncommon.

We report a case of a patient who presented with classic clinical and histopathological findings of ulcerative sarcoidosis to highlight the prototypical presentation of a rare condition. We also review 34 additional cases of ulcerative sarcoidosis published in the English-language literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ulcerative sarcoid.4-32 Analyzing this historical information, the scope of this unusual form of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be better understood, recognized, and treated. Although current standard-of-care treatments are most often successful, there is a paucity of definitive clinical trials to justify and verify comparative therapeutic efficacy.

Case Report

A 49-year-old black man with known pulmonary sarcoidosis, idiopathic (human immunodeficiency virus–negative) CD4 depletion syndrome, and chronic kidney disease presented with persistent bilateral ulcers of the legs of 1 month’s duration. The lesions first appeared as multiple “dark spots” on the legs. After the patient applied homemade aloe vera extract under occlusion for 1 to 2 days, the lesions became painful and began to ulcerate approximately 3 months prior to presentation. The patient applied a combination of a topical first aid antibiotic ointment, Epsom salts, and hydrogen peroxide without any improvement. A current review of systems was negative.

The patient’s medical history was notable for sarcoidosis diagnosed more than 10 years prior. During this time, he had intermittently been treated elsewhere with low-dose oral prednisone (5 mg once daily), hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily), and an inhaled steroid as needed. He had a history of human immunodeficiency virus–negative, idiopathic CD4 depletion syndrome, which had been complicated by cryptococcal meningitis 7 years prior to presentation. He also had renal insufficiency, with baseline creatinine levels ranging from 1.4 to 1.7 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). There was no personal or family history of known or suspected inflammatory bowel disease.

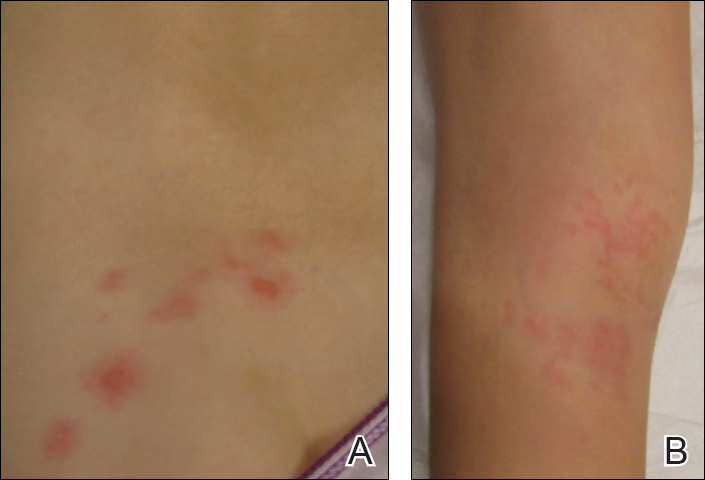

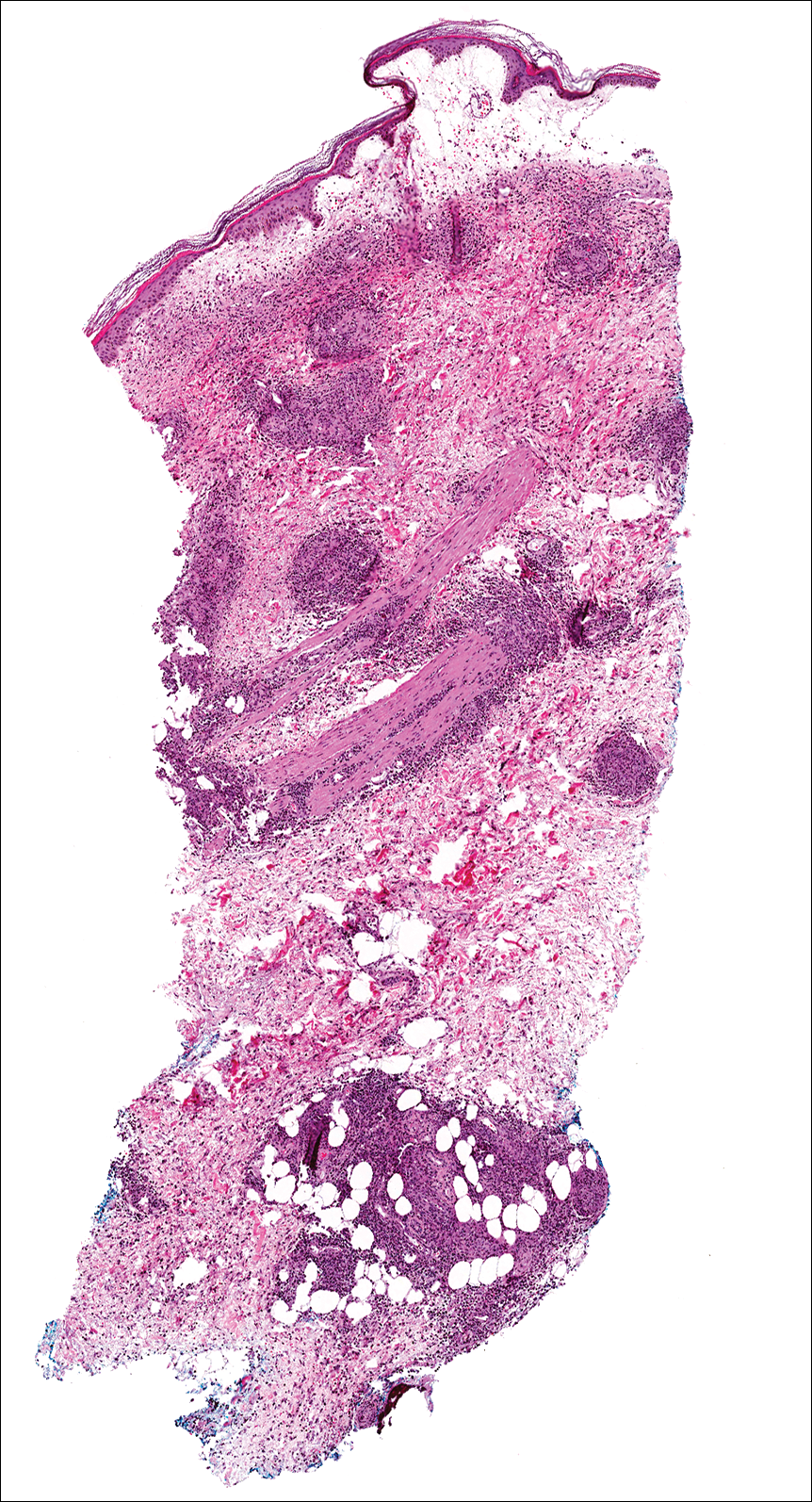

On physical examination, numerous discrete, coalescing, punched out–appearing ulcerations with foul-smelling, greenish yellow, purulent drainage were present bilaterally on the legs (Figure 1). The ulcers had a rolled border with a moderate amount of seemingly nonviable necrotic tissue. A number of hyperpigmented round papules, patches, and plaques also were present on the proximal legs. Laboratory evaluation revealed a CD4 count of 151 cc/mm3 (reference range, 500–1600 cc/mm3) and mildly elevated calcium of 10.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL).

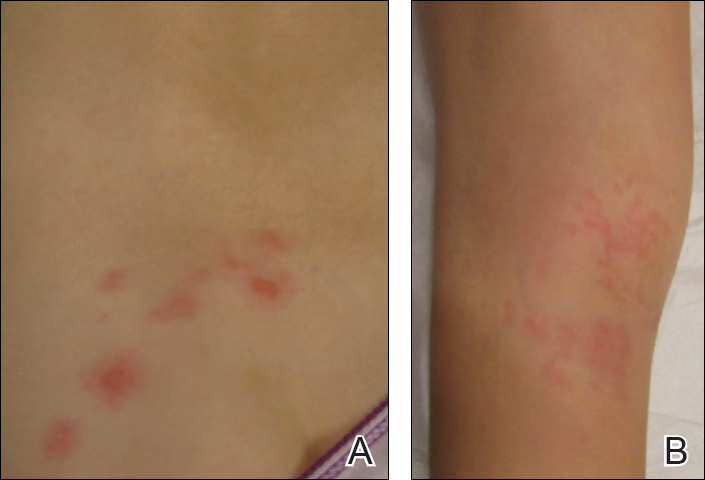

Aerobic, anaerobic, mycobacterial, and fungal cultures of the purulent exudate were obtained. Given a high suspicion for secondary infection of the exogenous wound sites, doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) and topical mupir-ocin were initiated. Gram stain revealed few to moderate polymorphonuclear cells and many gram-positive cocci in pairs, chains, and clusters, along with many gram-negative rods. Bacterial culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus species group G streptococci, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus–positive staphylococci. Ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) was then initiated, but the ulcers showed absolutely no clinical improvement and in fact worsened both in number and depth (Figure 2) over subsequent clinic visits during the next 3 months, even after amoxicillin (500 mg 3 times daily) was added. The patient was admitted for treatment with intravenous antibiotics after additional wound cultures revealed fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas.

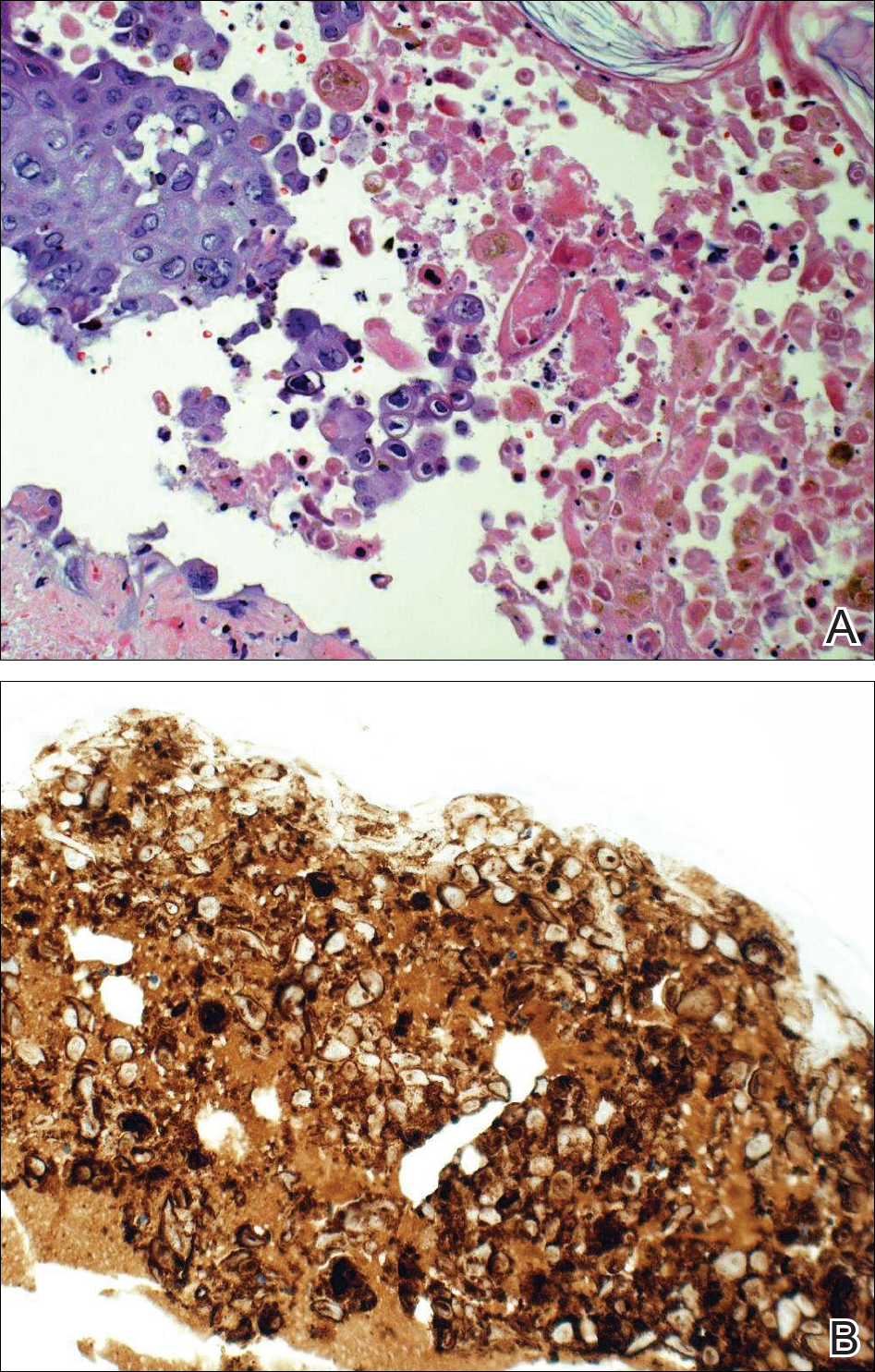

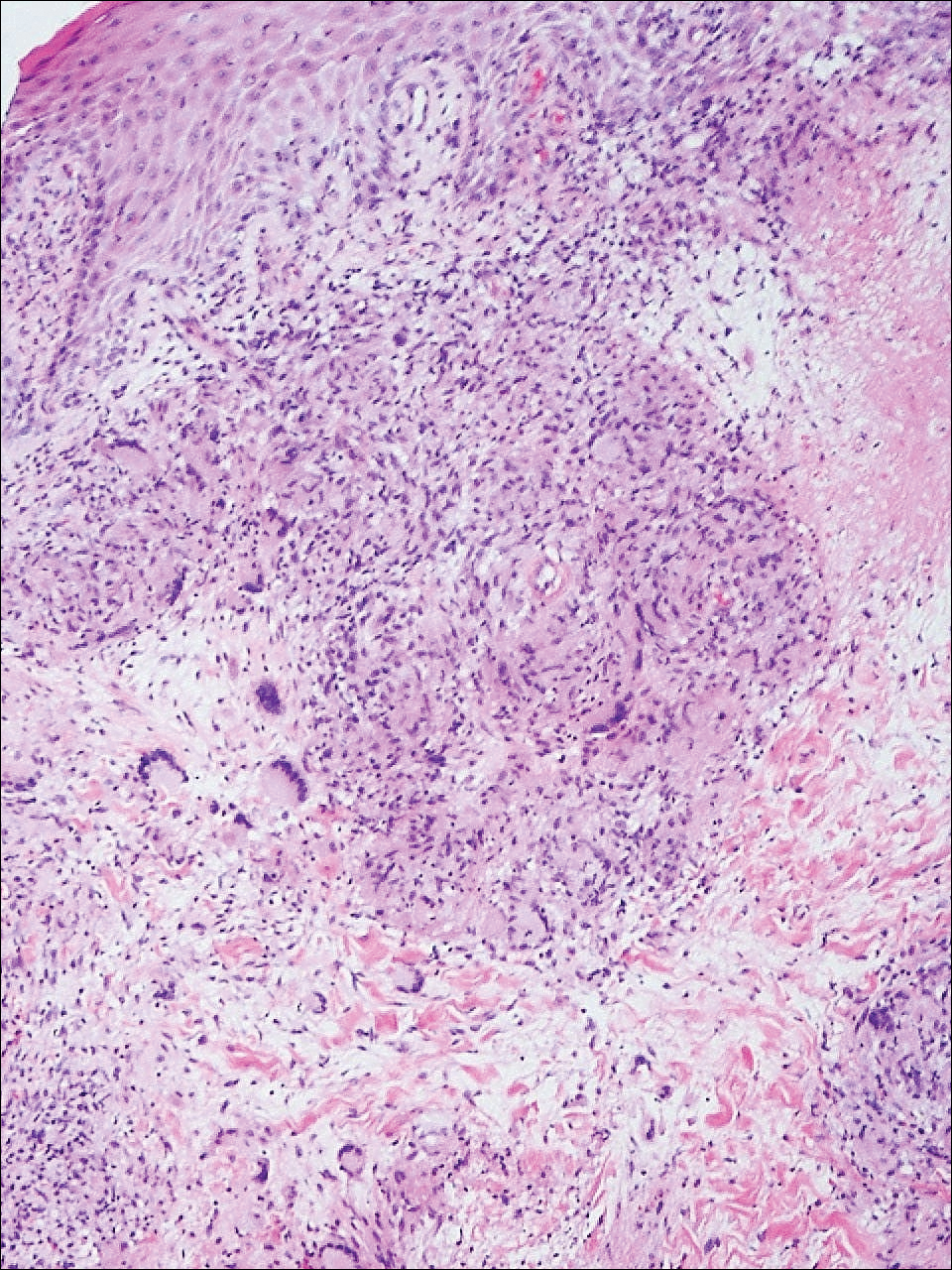

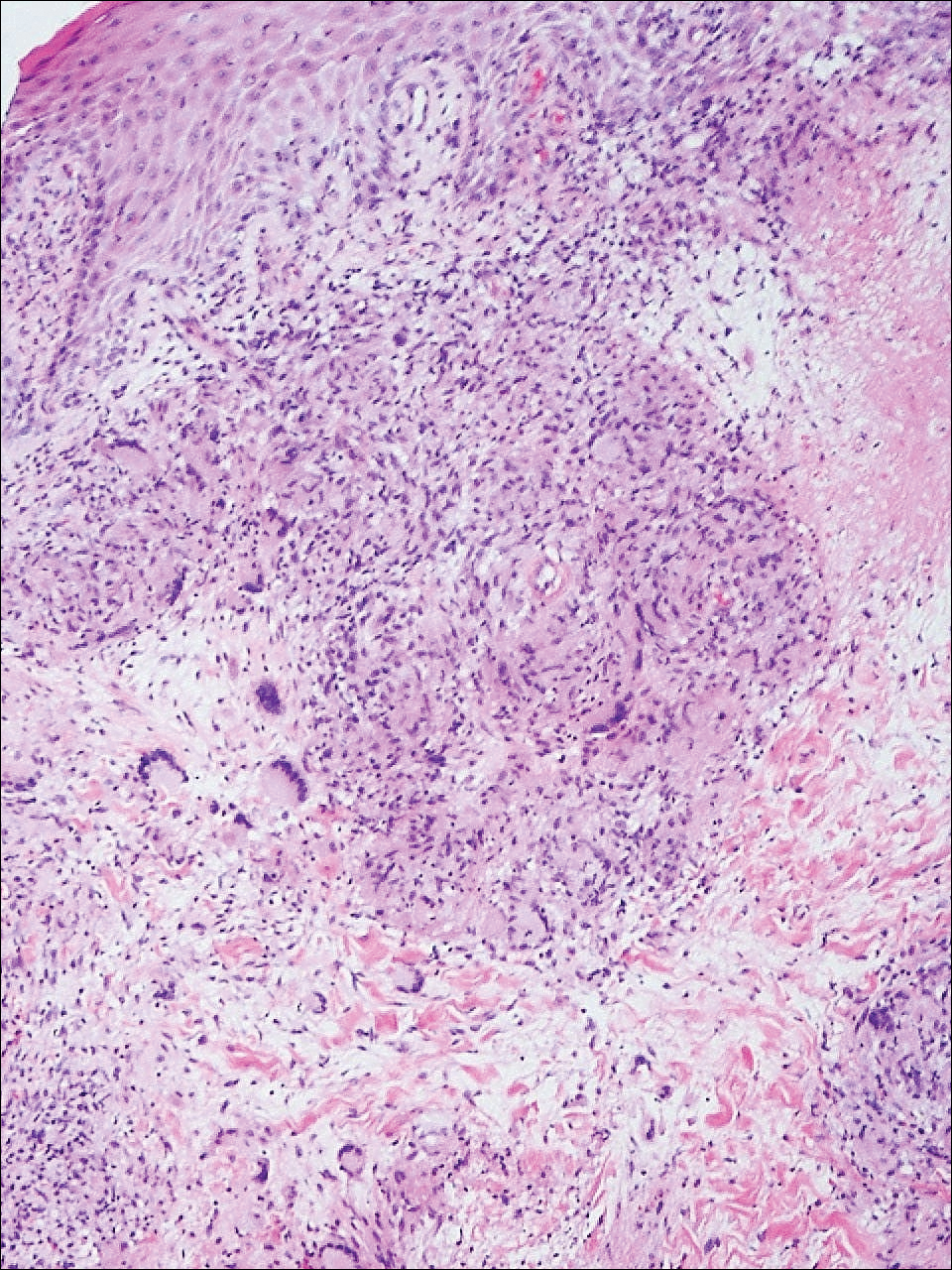

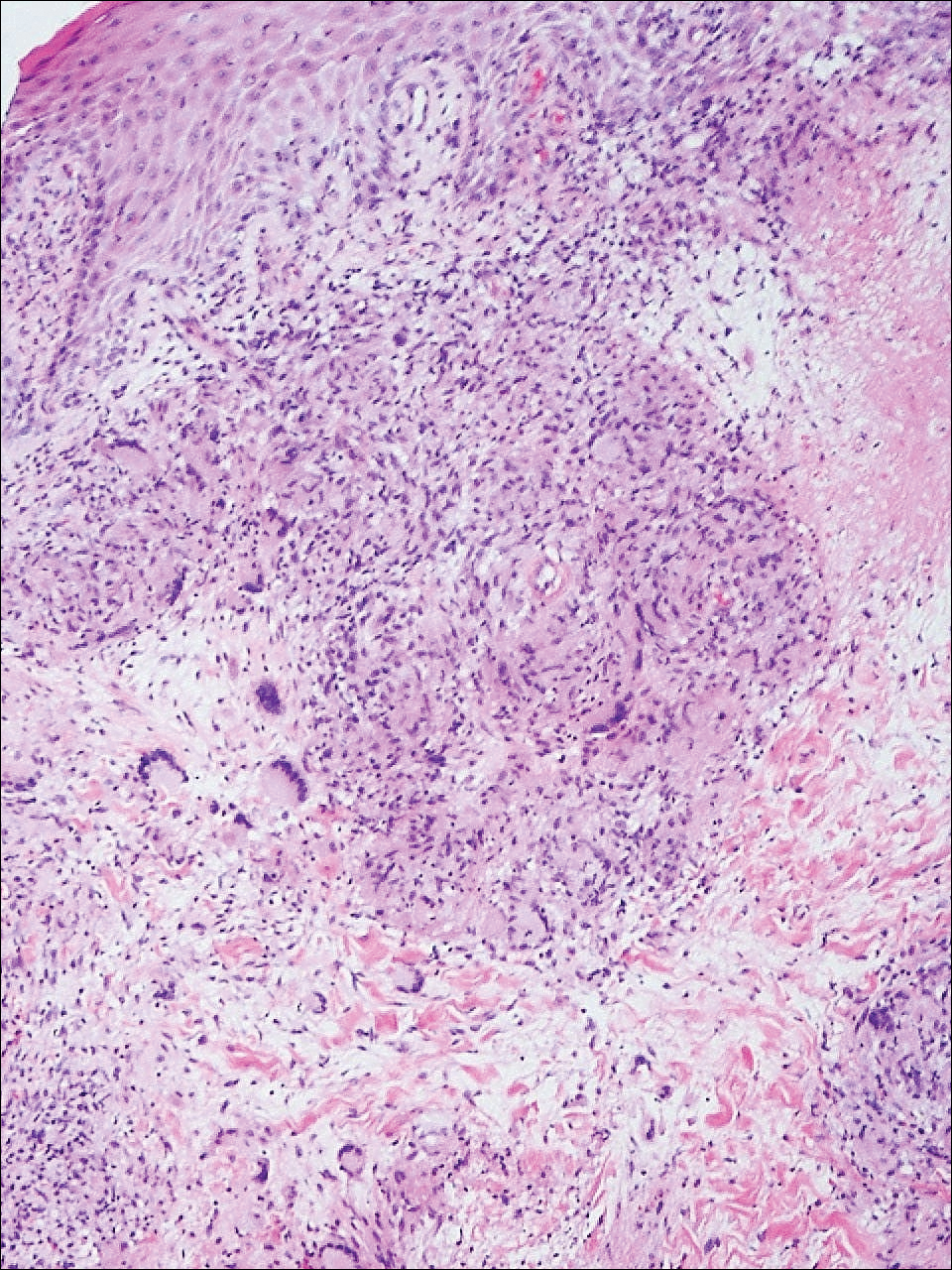

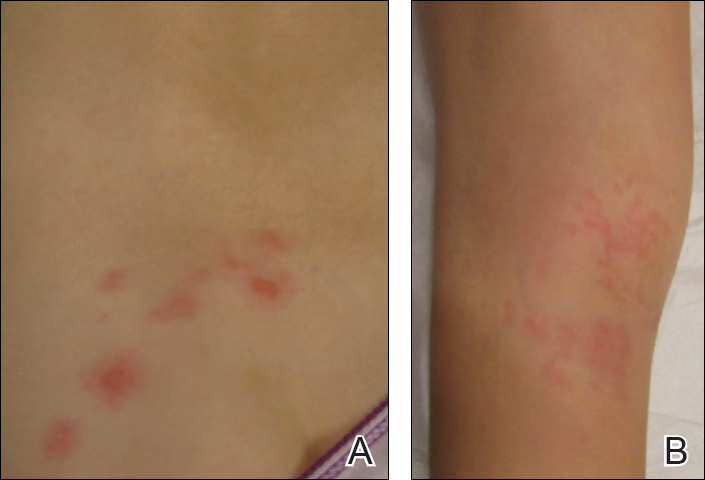

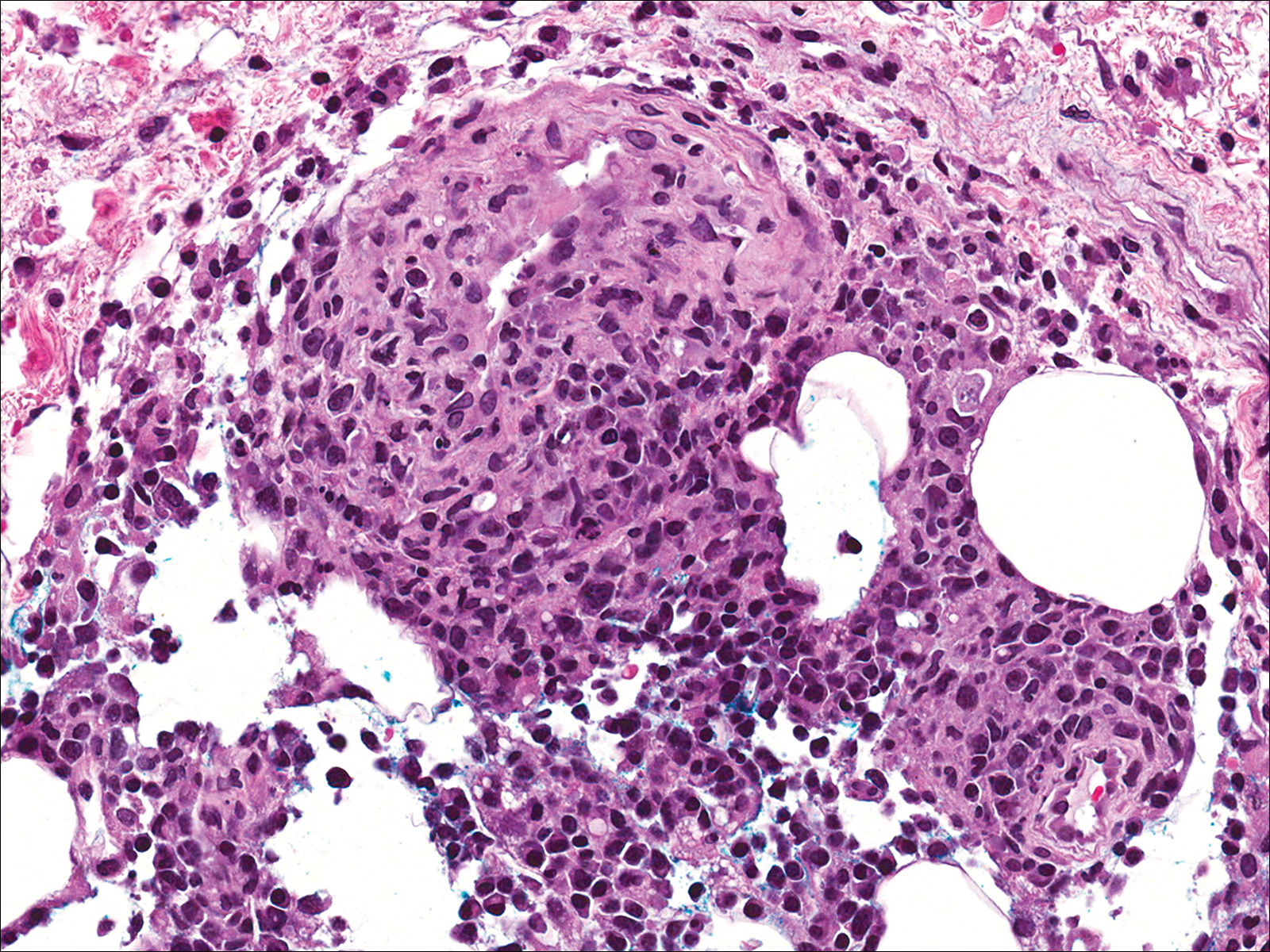

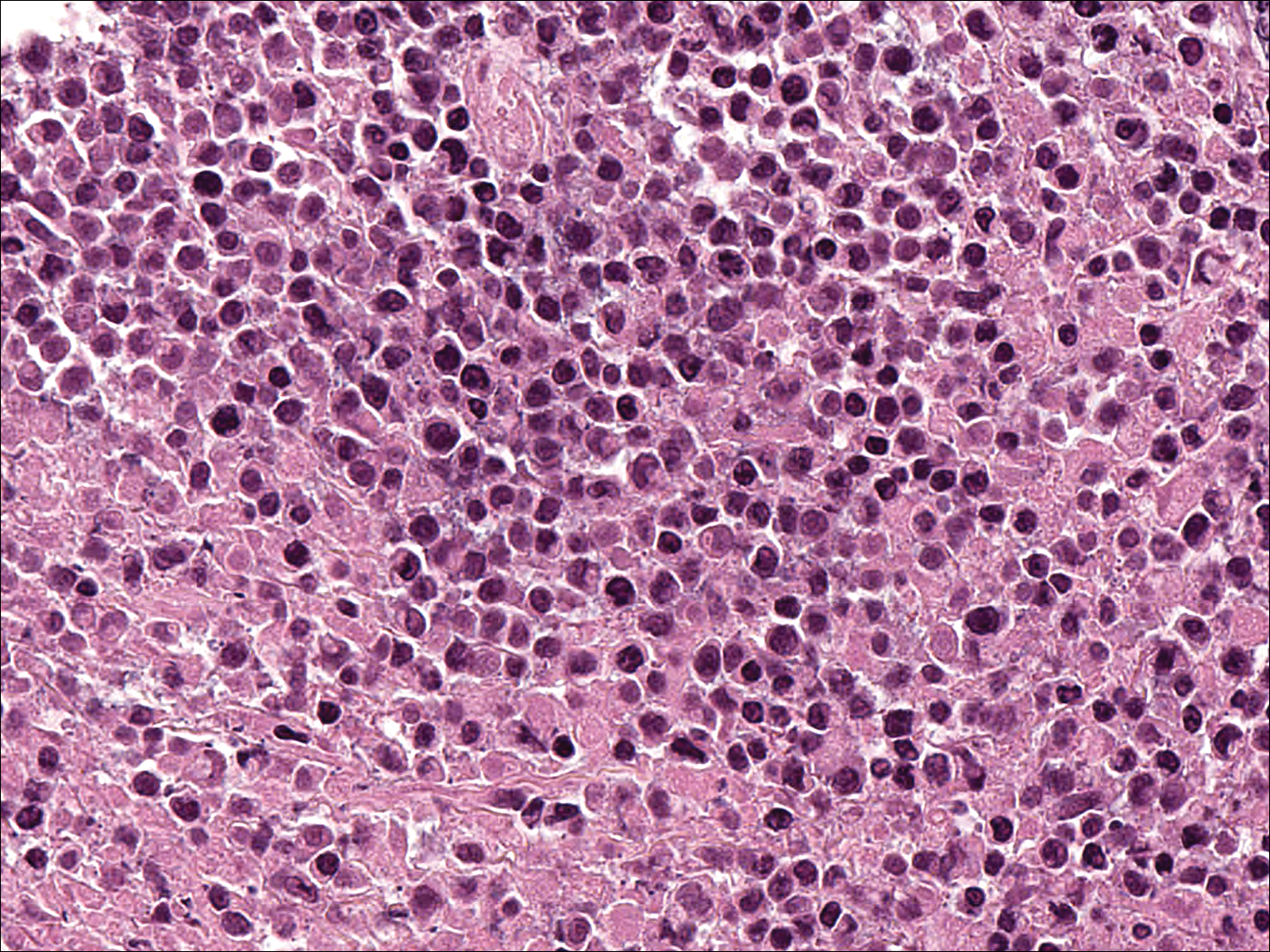

Punch biopsies of the ulcers showed nonspecific acute inflammation and tissue necrosis in the active ulcers with nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation extending into the deep dermis, with many Langerhans-type giant cells present in the palpable ulcer borders (Figure 3). Neither birefringent particles nor asteroid bodies were observed. Tissue Gram stains did not reveal evidence of bacterial infection. Special stains for acid-fast and fungal organisms (ie, periodic acid–Schiff, Gomori methenamine-silver, Fite, acid-fast bacilli) were similarly negative. Tissue cultures obtained on deep biopsy revealed only rare colonies of P aeruginosa and no isolates on anaerobic, mycobacterial, or fungal cultures. Polymerase chain reaction for mycobacteria and common endemic fungi also was negative. In the absence of infection and considering his history of known sarcoidosis, these histologic features were consistent with ulcerative sarcoidosis. The patient was started on prednisone (60 mg once daily) and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily). The prednisone was tapered to 20 mg once daily over a 2-year period, at which point 90% of the ulcers had healed. He was continued on hydroxychloroquine at the initial dose, and at a 3-year follow-up his ulcers had healed completely without relapse.

Comment

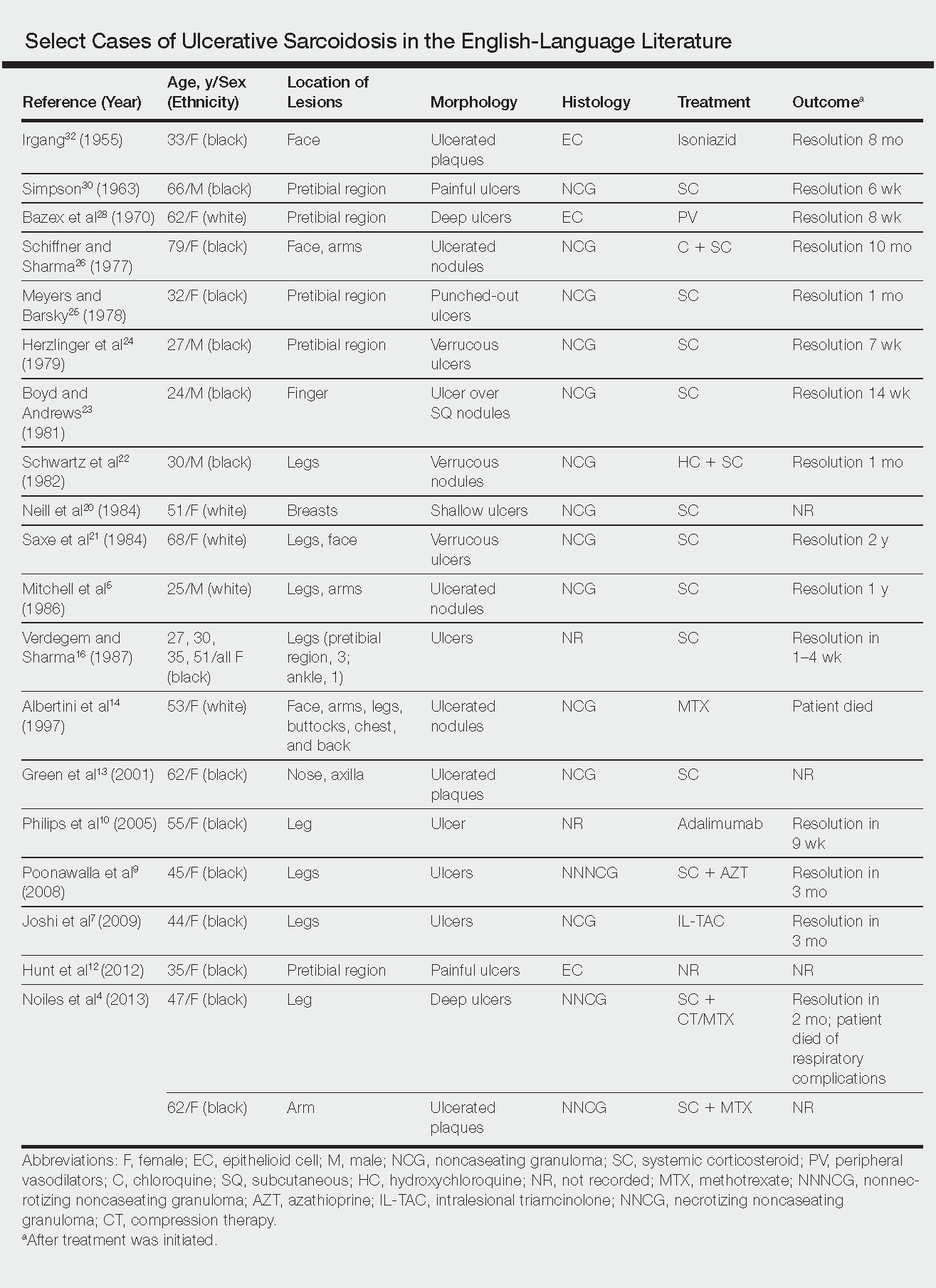

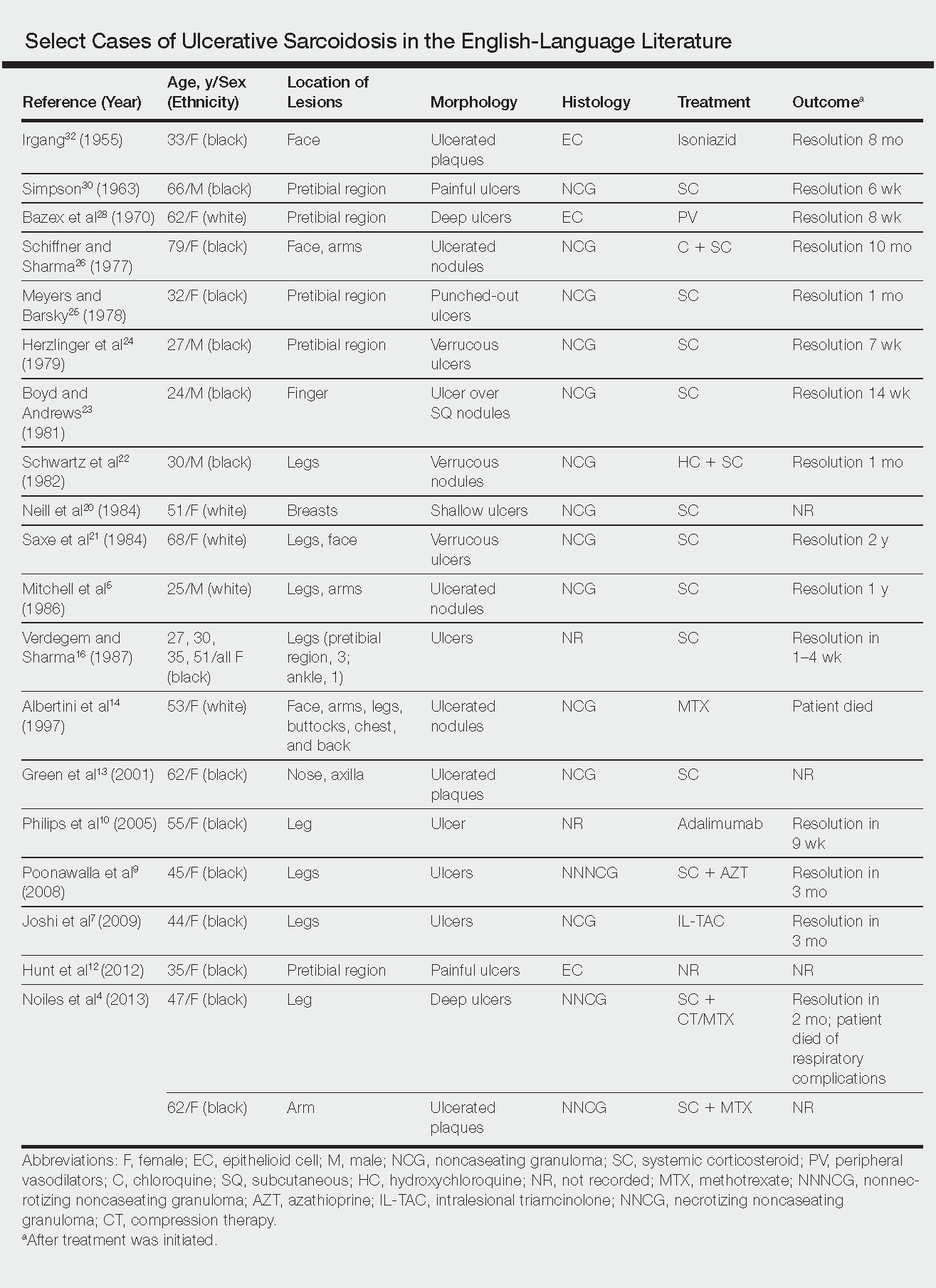

Ulcerative sarcoidosis is rare, seen worldwide in only 5% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis.33 However, cases have been encountered worldwide, with reports emanating from Japan, China, Germany, France, and Russia, among others.6,34-55 We reviewed 34 cases from the English-language literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ulcerative sarcoid and examined patient demographics, clinical presentation, histological findings, treatment type, and outcome. Key references are presented in the Table. Disease prevalence previously has been estimated as being 3-times more common in women than men1; in our literature review, we found a female to male ratio of 3.25 to 1. Additionally, ulcerative sarcoidosis is reported to be twice as common in black versus white individuals.33 In our literature review, when race was reported, 66% (21/32) of patients were black. Disease prevalence has been reported to peak at 20 to 40 years of age.3 In this review, the average age of presentation was 45 years (age range, 24–79 years).

Ulceration may arise de novo but more commonly arises in preexisting scars or cutaneous lesions. There are 2 distinct patterns seen in ulcerative sarcoidosis.4 The first is characterized by ulceration within necrotic yellow plaques.2 The second pattern is characterized by violaceous nodules arising in an annular confluent pattern that eventually ulcerate.4 This presentation commonly mimics or may be mimicked by multiple disease states, including sporotrichosis, tuberculosis, stasis dermatitis with venous ulceration, and even metastatic breast cancer.7,46,55,56 Regardless of presentation, the legs are the most common location of ulcer formation.1,33 In our review, 85% (29/34) of cases presented with involvement of the legs, including our own case. Other locations of ulcer formation have included the face, arms, trunk, and genital area.

On histologic examination of ulcerative sarcoidosis, epithelioid granulomas composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and scant numbers of lymphocytes are present.1,3 These formations are the noncaseating granulomas typical of sarcoidosis (Table). All of the cases in our review of the literature were described as either a collection of epithelioid granulomas with giant cell formation or noncaseating granulomas. There also have been reports of atypical features including necrotizing granulomas and granulomatous vasculitis.4,8,9,50 The histologic differential diagnosis in this case also would primarily include an infectious granulomatous process and less so an id reaction, rosacea, a paraneoplastic phenomenon, foreign body granulomas, and metastatic Crohn disease. The presence of ulceration, the large number of lesions, and the anatomic distribution help rule out most of these alternate diagnostic considerations. Diligent extensive workup was done in our patient to insure it was not an infection.

The goals of treatment include symptomatic relief, improvement in objective parameters of disease activity, and prevention of disease progression and subsequent disability.33,57 Fortunately, the majority of sarcoidosis patients with cutaneous symptoms achieve full recovery within months to years.33 Our literature review indicated that 81% (22/27) of patients with ulcerative lesions experienced full resolution within 1 year of treatment. Of those that did not (19% [5/27]), the patients were either lost to follow-up or died from other complications of sarcoidosis.

The widely accepted standard therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids; antimalarials; and methotrexate.33,57 Steroids and methotrexate act by suppressing granuloma formation, while antimalarials prevent antigen presentation (presumably part of the pathogenesis).33 For mild to moderate disease, topical and intralesional steroids may be all that is necessary.33,57 Systemic steroids are used for disfiguring, destructive, and widespread lesions that have been refractory to local and other systemic therapies.33,57 Steroids are tapered gradually depending on the patient’s response, as it is common for patients to relapse below a certain dose.33,57 Antimalarials (chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine) and methotrexate are considered adjunct treatments for patients who are either steroid unresponsive or who are unable to tolerate corticosteroid treatment due to adverse events.33,57

Standard therapy is complicated by the side effects of treatment. Use of corticosteroids may lead to gastrointestinal tract upset, increased appetite, mood disturbances, impaired wound healing, hyperglycemia, hypertension, cushingoid features, and acne.57 Antimalarials can cause nausea, anorexia, and agranulocytosis, and chloroquine therapy in particular can lead to blurred vision, corneal deposits, and central retinopathy.33,57 Methotrexate is associated with hematologic, gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary, and hepatic toxicities well known to most practitioners.

Because of the variable clinical response of patients to standard therapy and their associated toxicities, other treatment options have been used including pentoxifylline, tetracyclines, isotretinoin, leflunomide, thalidomide, infliximab, adalimumab, allopurinol, and the pulsed dye or CO2 laser.10,33,57 In nonhealing ulcers, split-thickness grafting and a bilayered bioengineered skin substitute have been used with good results in conjunction with ongoing systemic therapy.11,47 Additionally, nanoparticle silver burn paste has been used successfully, with resolution of ulcers within 2 weeks in the Chinese literature.53

All of these treatment recommendations are based on historically accepted modalities. Controlled trials with longitudinal follow-up are needed to provide justification for the current standard of care.34

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Elsevier; 2008:1421-1435.

- Doherty CB, Rosen T. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Drugs. 2008;68:1361-1383.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

- Noiles K, Beleznay K, Crawford RI, et al. Sarcoidosis can present with necrotizing granulomas histologically: two cases of ulcerated sarcoidosis and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:377-378.

- Mitchell IC, Sweatman MC, Rustin MH, et al. Ulcerative and hypopigmented sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:1062-1065.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Joshi SS, Romanelli R, Kirsner RS. Sarcoidosis mimicking a venous ulcer: a case report. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2009;55:46-48.

- Petri M, Barr E, Cho K, et al. Overlap of granulomatous vasculitis and sarcoidosis: presentation with uveitis, eosinophilia, leg ulcers, sinusitis and past foot drop. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1171-1173.

- Poonawalla T, Colome-Grimmer MI, Kelly B. Ulcerative sarcoidosis in the legs with granulomatous vasculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:282-286.

- Philips MA, Lynch J, Azmi FH. Ulcerative sarcoidosis responding to adalimumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:917.

- Collison DW, Novice F, Banse L, et al. Split-thickness skin grafting in extensive ulcerative sarcoidosis. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:679-683.

- Hunt RD, Gonzalez ME, Robinson M, et al. Ulcerative sarcoidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:29.

- Green JJ, Lawrence N, Heymann WR. Generalized ulcerative sarcoidosis induced by therapy with the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:507-508.

- Albertini JG, Tyler W, Miller OF. Ulcerative sarcoidosis. case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:215-219.

- Thomas J, Williams DW. Peritoneal involvement and ulcerative skin plaques in sarcoidosis: a case report. Sarcoidosis. 1989;6:161-162.

- Verdegem TD, Sharma OP. Cutaneous ulcers in sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1531-1534.

- Gupta AK, Haberman HF, From GL, et al. Sarcoidosis with extensive cutaneous ulceration. unusual clinical presentation. Dermatologica. 1987;174:135-139.

- Hruza GJ, Kerdel FA. Generalized atrophic sarcoidosis with ulcerations. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:320-322.

- Muhlemann MF, Walker NP, Tan LB, et al. Elephantine sarcoidosis presenting as ulcerating lymphoedema. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:260-261.

- Neill SM, Smith NP, Eady RA. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: a rare manifestation of a common disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:277-279.

- Saxe N, Benatar SR, Bok L, et al. Sarcoidosis with leg ulcers and annular facial lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:93-96.

- Schwartz RA, Robertson DB, Tierney LM, et al. Generalized ulcerative sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:931-933.

- Boyd RE, Andrews BS. Sarcoidosis presenting as cutaneous ulceration, subcutaneous nodules and chronic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1981;8:311-316.

- Herzlinger DC, Marland AM, Barr RJ. Verrucous ulcerative skin lesions in sarcoidosis. an unusual clinical presentation. Cutis. 1979;23:569-572.

- Meyers M, Barsky S. Ulcerative sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:447.

- Schiffner J, Sharma OP. Ulcerative sarcoidosis. report of an unusual case. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:676-677.

- Williamson DM. Sarcoidosis with atrophic lesions and ulcers of the legs. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:92-93.

- Bazex A, Dupre A, Christol B, et al. Sarcoidosis with atrophic lesions and ulcers and the presence in some sarcoid granulomata of orceinophil fibres. Br J Dermatol. 1970;83:255-262.

- Brodkin RH. Leg ulcers. a report of two cases caused by sarcoidosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1969;49:584-587.

- Simpson JR. Sarcoidosis with erythrodermia and ulceration. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:193-198.

- Irgang S. Ulcerative cutaneous lesion in sarcoidosis; report of a case with clinical resemblance to lupus vulgaris. Harlem Hosp Bull. 1956;8:134-139.

- Irgang S. Ulcerative cutaneous lesions in sarcoidosis; report of a case with clinical resemblance to papulonecrotic tuberculide. Br J Dermatol. 1955;67:255-260.

- Hoffman MD. Atypical ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:222-235.

- Hopf B, Krebs A. Ulcera cruris as a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis. Dermatologica. 1974;113:55-62.

- Metz J, Hartmann A, Hautkr Z. Ulcerative form of skin sarcoidosis. Z Hautkr. 1977;52:890-896.

- Berenbeĭn BA, Malygina LA, Tiutiunnikova IA. Ulcerative form of skin sarcoidosis [in Russian]. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1984;4:50-53.

- Takahashi N, Hoshino M, Takase T, et al. A case of ulcerative sarcoidosis [in Japanese]. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;95:1049-1054.

- Schamroth JM. Sarcoidosis with severe extensive skin ulceration. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:451-452.

- Porteau L, Dromer C, Le Guennec P, et al. Ulcer lesions in sarcoidosis: apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1997;148:105-106.

- de La Blanchardière A, Bachmeyer C, Toutous L, et al. Cutaneous ulcerations in sarcoidosis [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 1995;16:927-929.

- Mitsuishi T, Nogita T, Kawashima M. Psoriasiform sarcoidosis with ulceration. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:339-340.

- Rodionov AN, Samtsov AV. The ulcerative form of skin sarcoidosis [in Russian]. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1990;7:68-71.

- Jacyk WK. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in black South Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:841-845.

- Gungor E, Artuz F, Alli N, et al. Ulcerative sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:78-79.

- Schleinitz N, Luc M, Genot S, et al. Ulcerative cutaneous lesions: a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2005;26:758-759.

- Klocker J, Duckers J, Morse R, et al. Ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis masquerading as metastatic carcinoma of the breast. Age Ageing. 2002;31:77-79.

- Streit M, Bohlen LM, Braathen LR. Ulcerative sarcoidosis successfully treated with apligraf. Dermatology. 2001;202:367-370.

- Ichiki Y, Kitajima Y. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: case report and review of the Japanese literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:526-528

- Meyersburg D, Schön MP, Bertsch HP, et al. Uncommon cutaneous ulcerative and systemic sarcoidosis. successful treatment with hydroxychloroquine and compression therapy [in German]. Hautarzt. 2011;62:691-695.

- Wei CH, Huang YH, Shih YC, et al. Sarcoidosis with cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:198-201.

- Kluger N, Girard C, Durand L, et al. Leg ulcers revealing systemic sarcoidosis with splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1425-1427.

- Jun L, Jia-Wei L, Hong-Zhong J. Ulcerative sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E315-E316.

- Chen JH, Wang TT, Lin ZQ. Successful application of a novel dressing for the treatment of ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis. Chin Med J. 2013;126:3400.

- Ri G, Yoshikawa E, Shigekiyo T, et al. Takayasu artertitis and ulcerative sarcoidosis. Intern Med. 2015;54:1075-1080.

- Spiliopoulou I, Foka A, Bounas A, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii cutaneous infection in a patient with sarcoidosis treated with anti-TNF agents. Acta Clin Belg. 2014;69:229-231.

- Yang DJ, Krishnan RS, Guillen DR, et al. Disseminated sporotrichosis mimicking sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:450-453.

- Badgwell C, Rosen T. Cutaneous sarcoidosis therapy updated. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:69-83.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that primarily affects the lungs and lymphatic system but also may involve the skin, eyes, liver, spleen, muscles, bones, and nervous system.1 Cutaneous symptoms of sarcoidosis occur in approximately 25% of patients and are classified as specific and nonspecific, with specific lesions demonstrating noncaseating granuloma formation, which is typical of sarcoidosis.2 Nonspecific lesions primarily include erythema nodosum and calcinosis cutis. Specific lesions commonly present as reddish brown infiltrated plaques that may be annular, polycyclic, or serpiginous.1,3 They also may appear as yellowish brown or violaceous maculopapular lesions. However, specific lesions may present in a wide variety of morphologies, most often papules, nodules, subcutaneous infiltrates, and lupus pernio.4 Additionally, atypical cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis include erythroderma; scarring alopecia; nail dystrophy; and verrucous, ichthyosiform, psoriasiform, hypopigmented, or ulcerative skin lesions.3-5 Among these many potential clinical presentations, ulcerative sarcoidosis is quite uncommon.

We report a case of a patient who presented with classic clinical and histopathological findings of ulcerative sarcoidosis to highlight the prototypical presentation of a rare condition. We also review 34 additional cases of ulcerative sarcoidosis published in the English-language literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ulcerative sarcoid.4-32 Analyzing this historical information, the scope of this unusual form of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be better understood, recognized, and treated. Although current standard-of-care treatments are most often successful, there is a paucity of definitive clinical trials to justify and verify comparative therapeutic efficacy.

Case Report

A 49-year-old black man with known pulmonary sarcoidosis, idiopathic (human immunodeficiency virus–negative) CD4 depletion syndrome, and chronic kidney disease presented with persistent bilateral ulcers of the legs of 1 month’s duration. The lesions first appeared as multiple “dark spots” on the legs. After the patient applied homemade aloe vera extract under occlusion for 1 to 2 days, the lesions became painful and began to ulcerate approximately 3 months prior to presentation. The patient applied a combination of a topical first aid antibiotic ointment, Epsom salts, and hydrogen peroxide without any improvement. A current review of systems was negative.

The patient’s medical history was notable for sarcoidosis diagnosed more than 10 years prior. During this time, he had intermittently been treated elsewhere with low-dose oral prednisone (5 mg once daily), hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily), and an inhaled steroid as needed. He had a history of human immunodeficiency virus–negative, idiopathic CD4 depletion syndrome, which had been complicated by cryptococcal meningitis 7 years prior to presentation. He also had renal insufficiency, with baseline creatinine levels ranging from 1.4 to 1.7 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). There was no personal or family history of known or suspected inflammatory bowel disease.

On physical examination, numerous discrete, coalescing, punched out–appearing ulcerations with foul-smelling, greenish yellow, purulent drainage were present bilaterally on the legs (Figure 1). The ulcers had a rolled border with a moderate amount of seemingly nonviable necrotic tissue. A number of hyperpigmented round papules, patches, and plaques also were present on the proximal legs. Laboratory evaluation revealed a CD4 count of 151 cc/mm3 (reference range, 500–1600 cc/mm3) and mildly elevated calcium of 10.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL).