User login

Photosensitive Atopic Dermatitis Exacerbated by UVB Exposure

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of the global population.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic relapsing dermatitis with pruritus, often beginning in infancy or childhood. Atopic dermatitis is caused by a defect in epidermal barrier function, which results in increased transepidermal water loss.1 The criteria for AD include a pruritic skin condition plus 3 or more of the following: history of involvement of the skin creases, history of asthma or hay fever, history of AD in a first-degree relative (in children), 1-year history of generally dry skin, visible flexural eczema, and an age of onset of less than 2 years. Adults with AD frequently present with hand or facial dermatitis.1

UV light therapies including narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) have all been used as effective treatments of AD.3,4 UV light is beneficial for AD patients due to its immunomodulatory effects, thickening of the stratum corneum, and the reduction of Staphylococcus aureus in the skin.2 Most patients with AD improve with light therapy; however, it is estimated that 1% to 3% of patients with AD will experience a paradoxical worsening of their AD after exposure to UV light.2,5 This condition is referred to as photosensitive AD and is characterized by a photodistributed rash in patients who fulfill the criteria of AD. Photosensitive AD has a female predominance and generally affects patients with late-onset disease with development of AD after puberty.2,5 The pathogenesis for the development of photosensitivity in patients with AD who previously tolerated exposure to sunlight is unknown.5 We describe a case of photosensitive AD exacerbated by UVB exposure.

Case Report

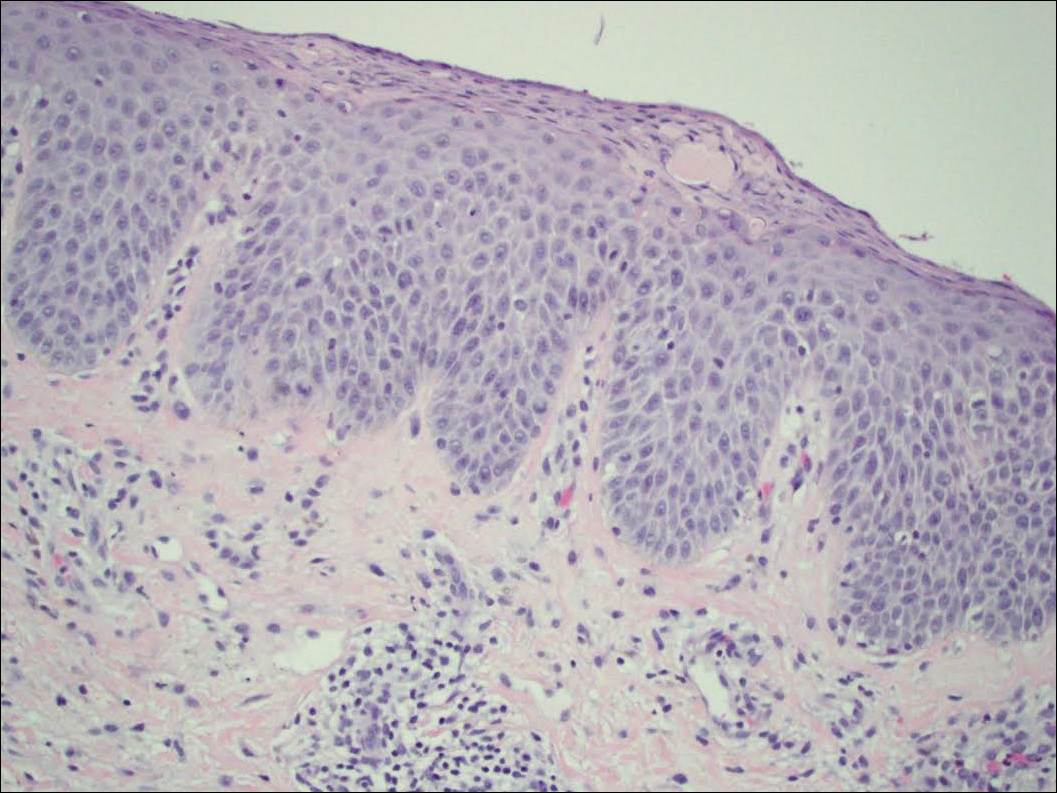

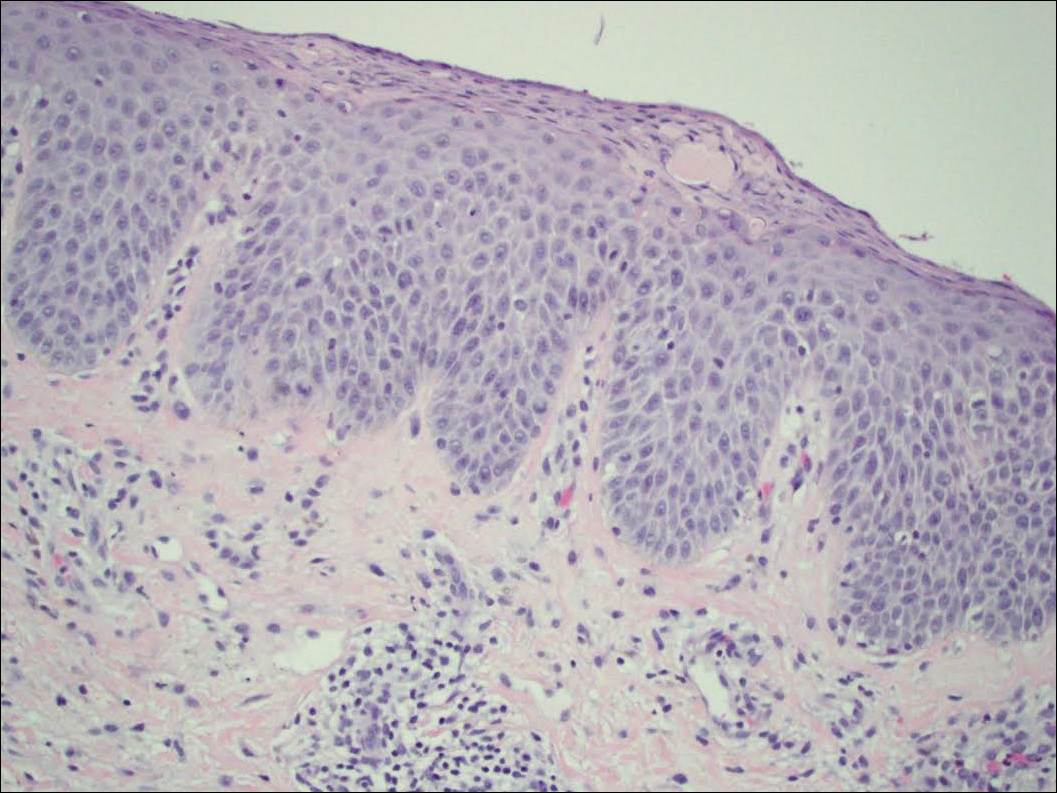

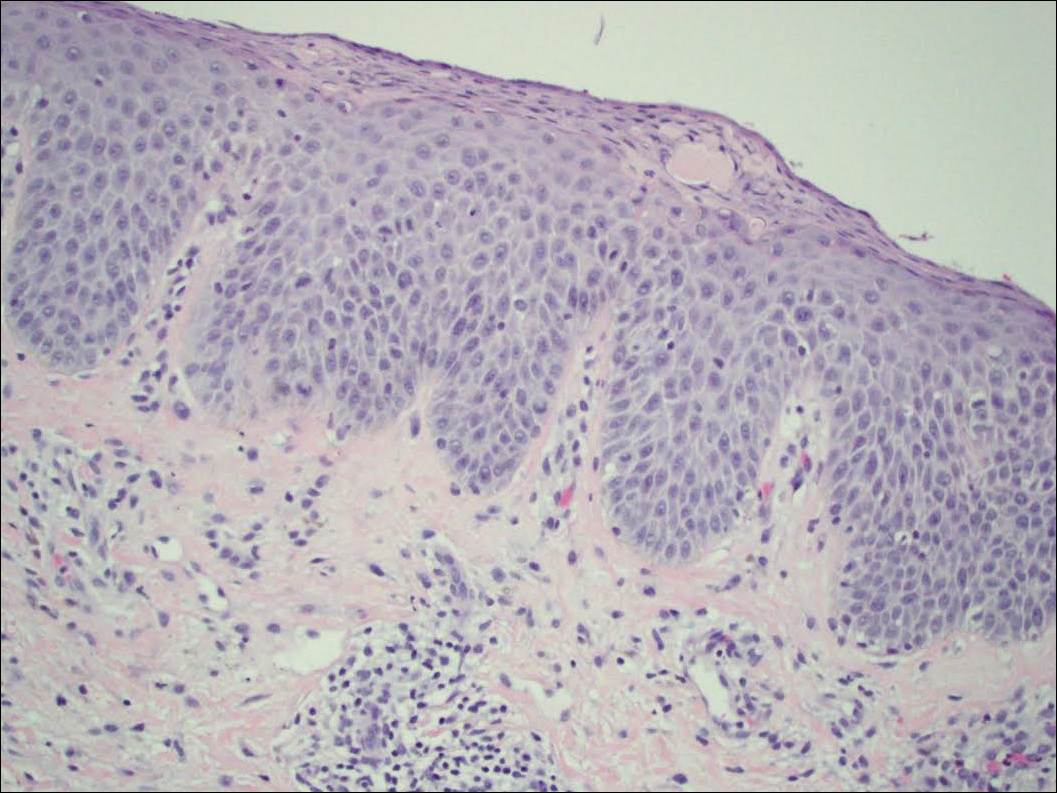

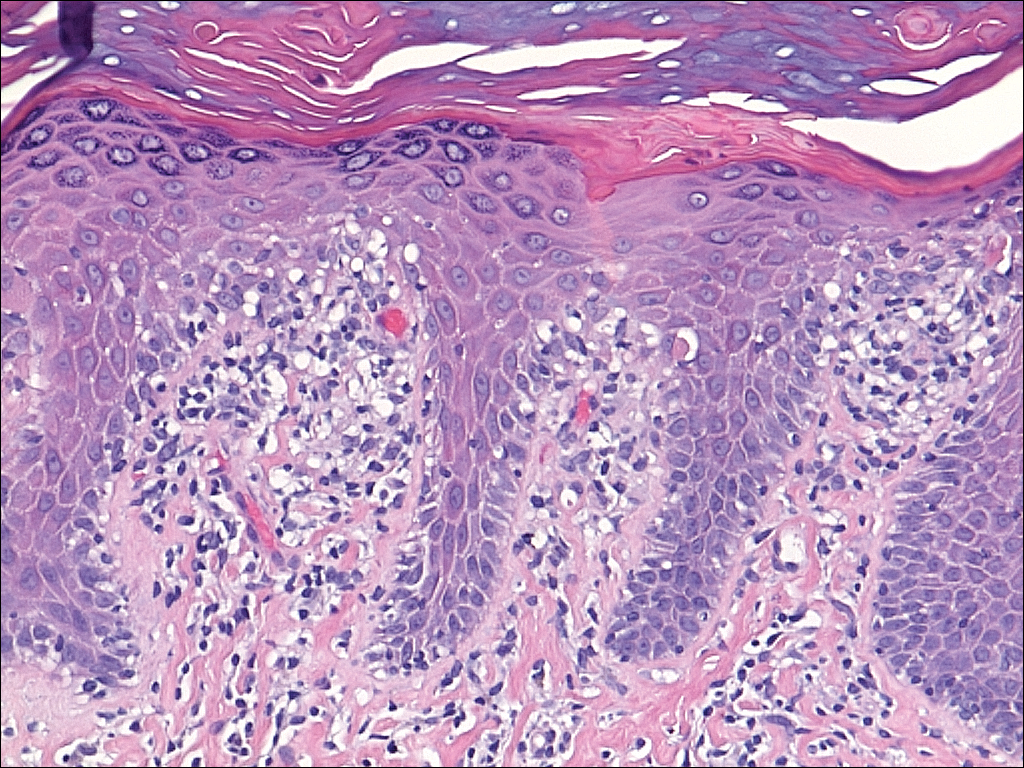

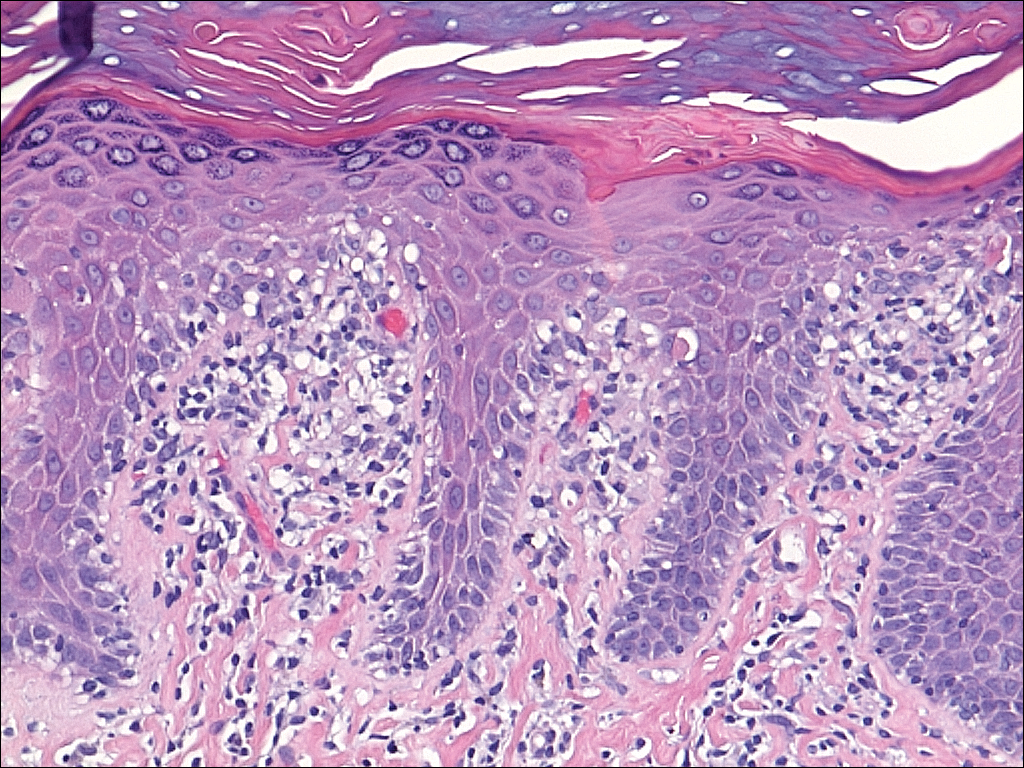

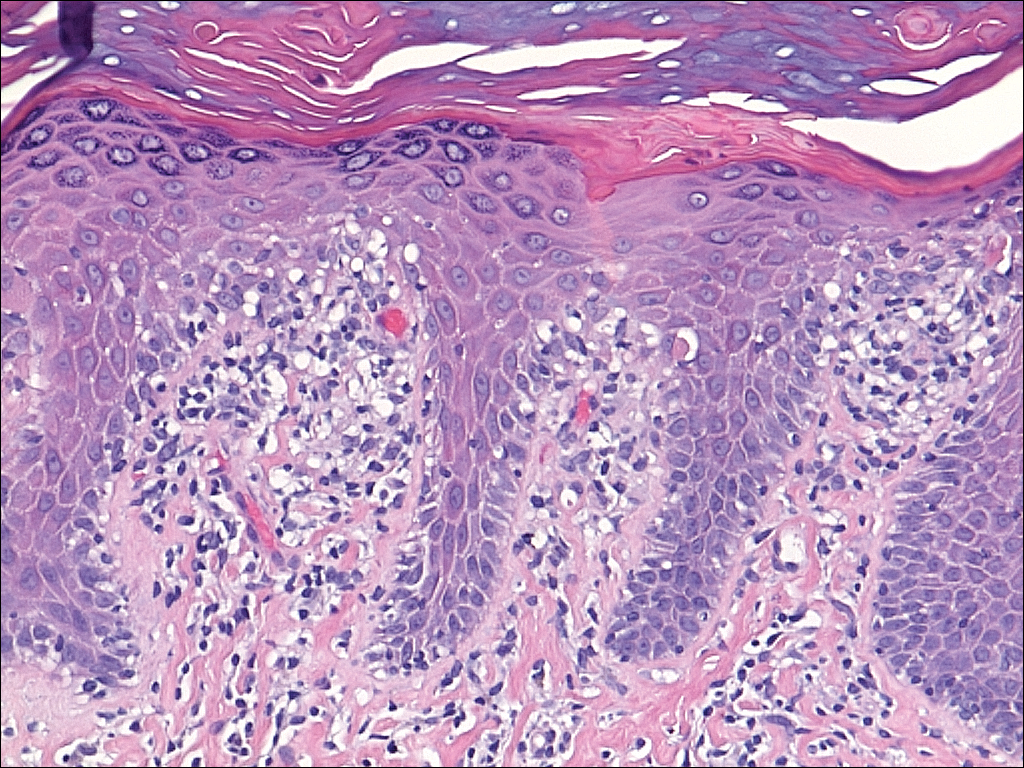

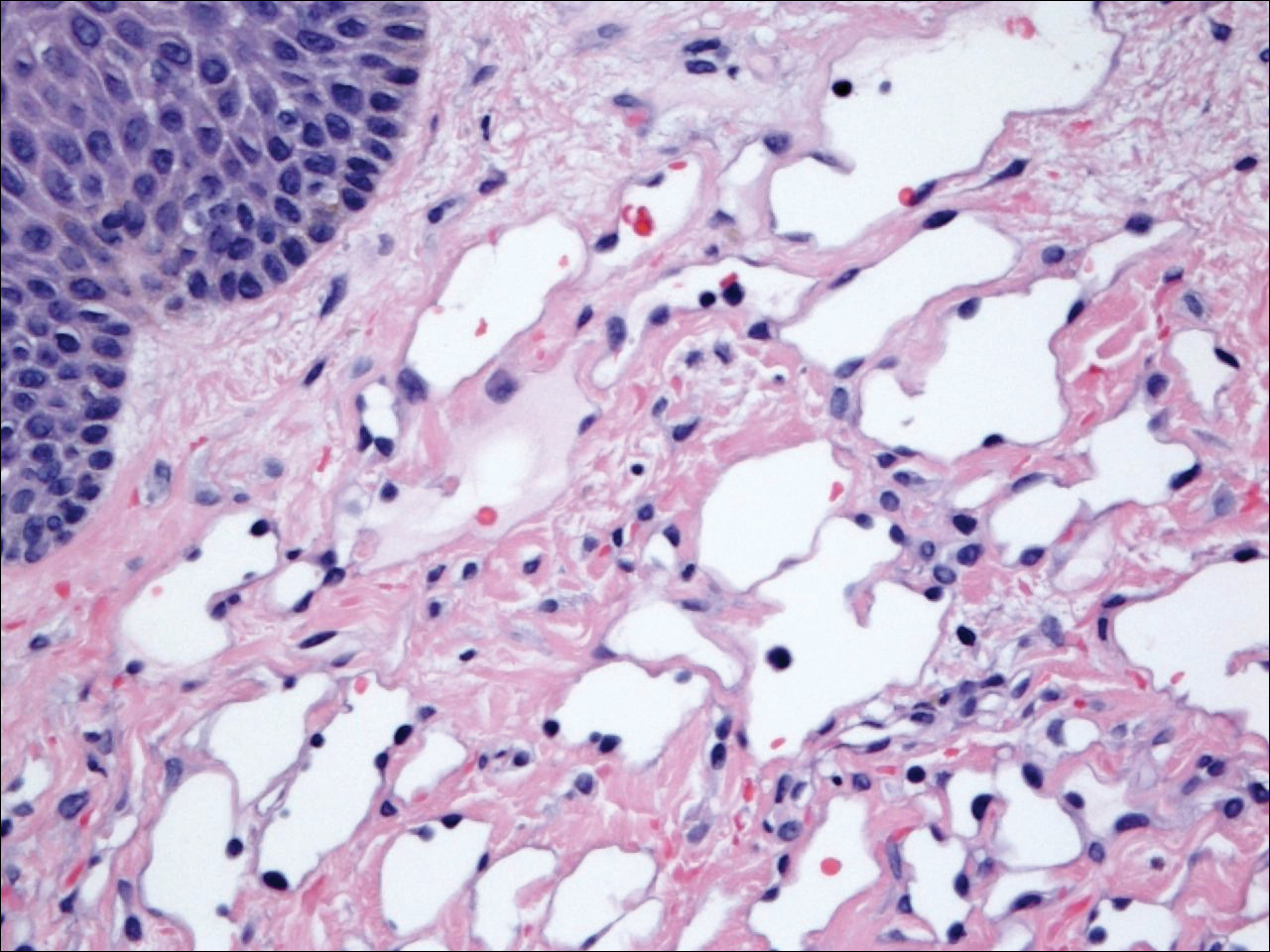

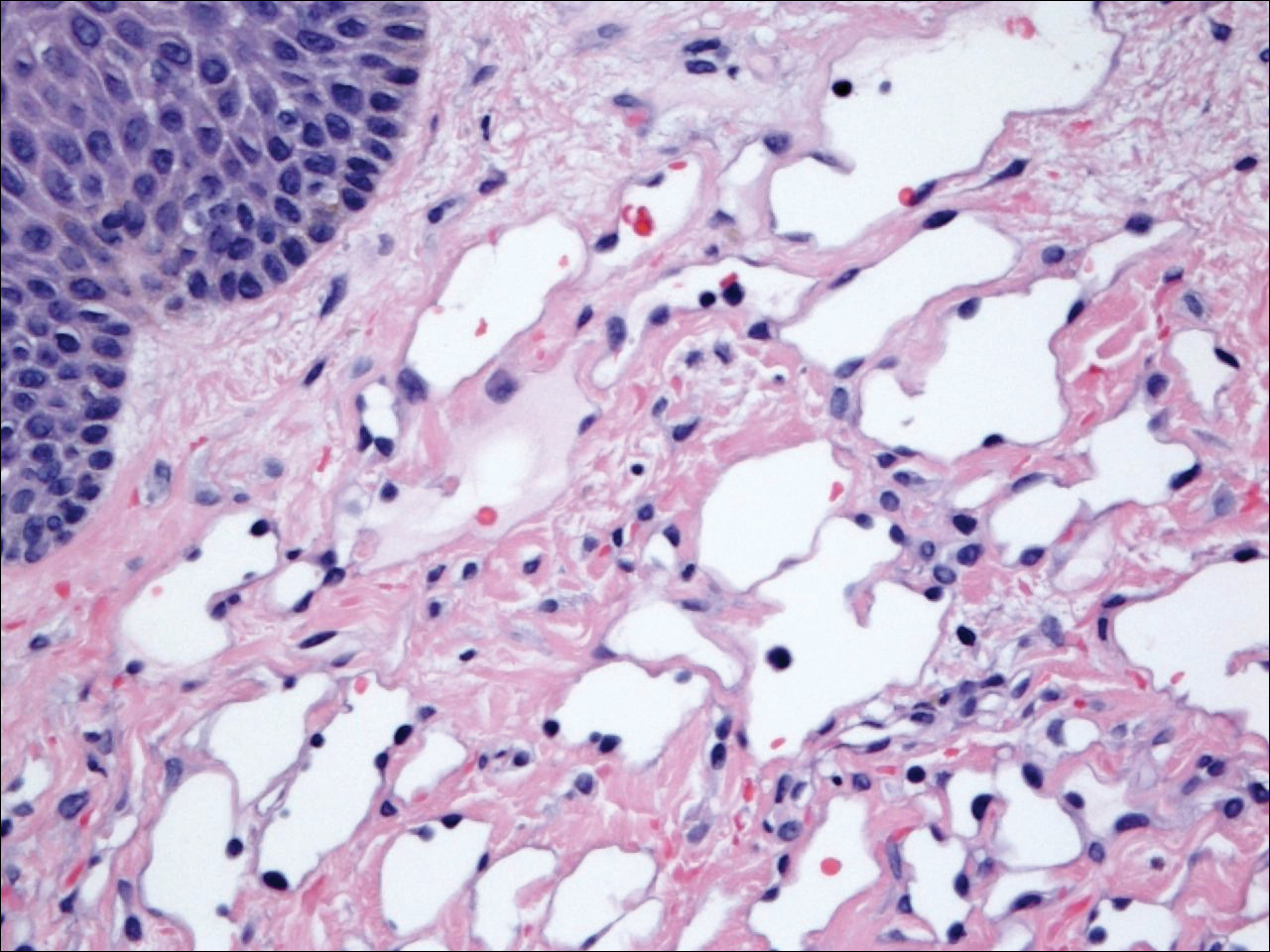

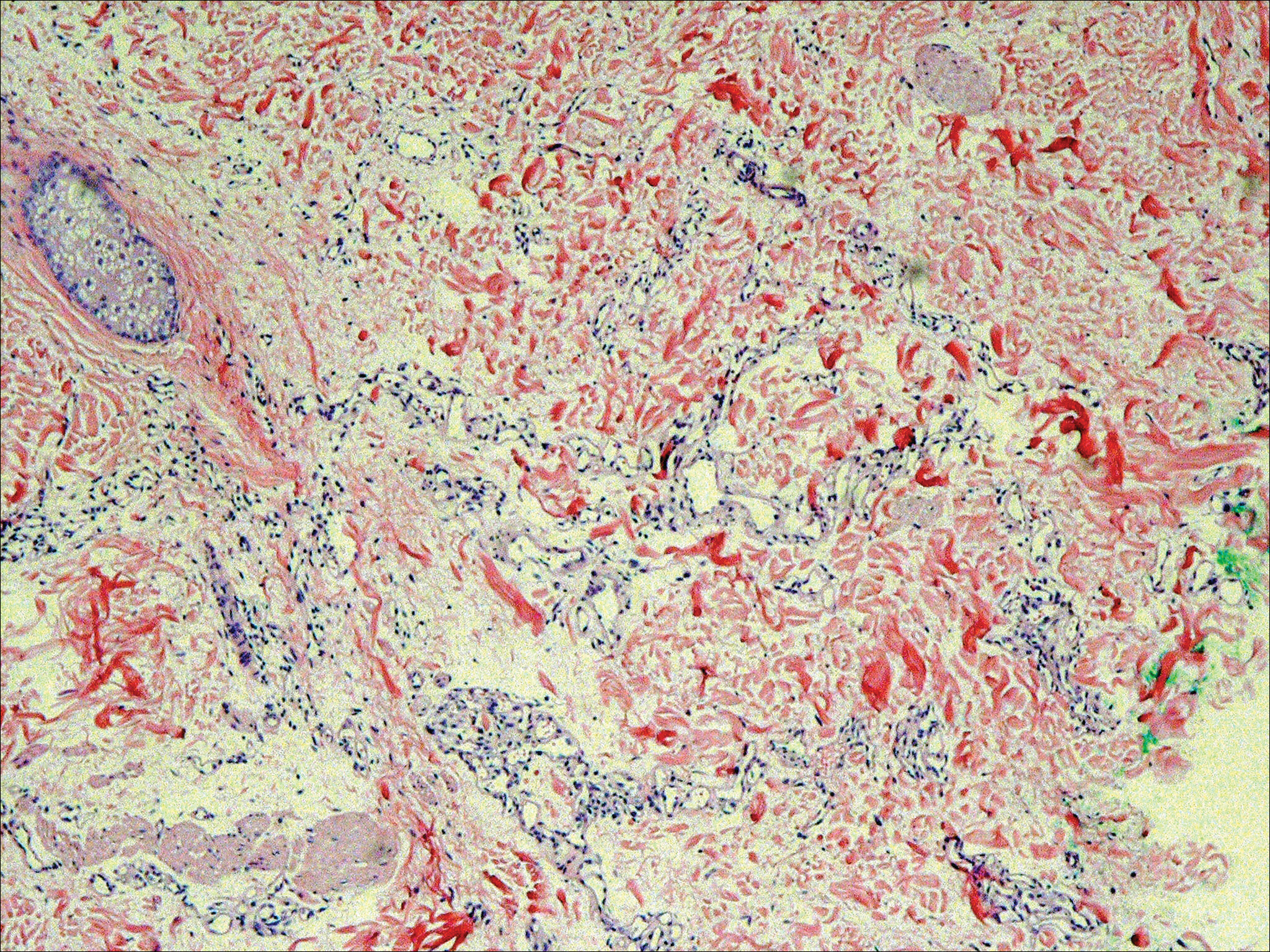

On physical examination the patient had thin, well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with scaling, primarily on sun-exposed skin on the forehead (Figure 1A), cheeks (Figure 1B), eyelids, upper lip, neck (Figures 1B and 1C), upper chest (Figure 1C), and dorsal aspect of the hands, with excoriated pink papules on the forearms, shoulders, and back. A punch biopsy of the right neck showed spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Further workup was pursued including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, liver function panel, Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B test, antinuclear antibody test, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antigen/antibody test, hepatitis panel, and mycobacterium tuberculosis test, which were all within reference range. Photodermatosis was suspected and she underwent phototesting including UVA, NB-UVB, and visible light. Phototesting confirmed she had a UVB photosensitivity with a markedly decreased minimal erythema dose (MED) to NB-UVB. The MED to NB-UVB was positive at 24 hours to all tested sites, the lowest of which was 0.135 J/cm2. Eczematous changes began to develop at day 6 at doses of 0.945 and 1.080 J/cm2. The patient also underwent visible light testing, which was negative. The patient was patch tested for multiple standardized agents as well as personal products, all of which were negative. Subsequent photopatch testing revealed a slightly positive reaction to benzophenone 4, a common ingredient in sunscreens.

The patient was then started on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Repeat MED testing to NB-UVB was performed. Her repeat MED to NB-UVB was determined to be 0.405 J/cm2, and hardening commenced at 3 times per week at 70% of the MED (0.2835 J/cm2). She began to flare and develop an eczematous reaction, thus the dose was decreased to 50% of the MED (0.2025 J/cm2), which she tolerated.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The literature on photosensitive AD is scant, and this disease entity is rare. Alternative names include photoaggravated AD, photosensitive eczema, and light-exacerbated eczema.5 Two main studies have been conducted in recent years that were intended to characterize photosensitive AD. ten Berge et al5 conducted a retrospective study of 145 patients with AD that were phototested in 2009. They found that 3% of their total AD patient population had photosensitive AD.5 In 2016, Ellenbogen et al2 performed a similar single-center retrospective analysis of 17 patients with long-standing AD who suddenly developed photosensitivity.

Patients with photosensitive AD typically present with lesions on sun-exposed skin with coexisting eczematous lesions in sites with a predilection for AD.2 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 2 main reaction patterns were observed: erythematous papules with pruritus and an eczematous reaction.

Histopathology

The histopathologic findings of photosensitive AD are nonspecific but are characterized by spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2

Diagnosis With Phototesting

Phototesting of patients with AD should be considered if there is a suspicion for photosensitivity based on persistent disease despite use of photoprotection and local treatment.5-7 Patients may not notice a correlation of skin exacerbations with UV exposure, especially if they are only sensitive to UVA, as it is still present on cloudy days and can penetrate glass windows.8 Phototesting evaluates the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response. Phototesting consists of determining the MED to UVA and UVB, the minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA, and visible light exposure. Further evaluation may include photoprovocation testing or photopatch testing, as these patients can have coexisting photocontact allergies.

The MED is defined as the minimal dose of UV light needed to induce perceptible erythema in exposed skin.5 It is dependent on the light source and patient’s skin type, and individual units may vary. To determine the MED to UVA or UVB, 2×2-cm skin fields are irradiated with increasing cumulative UVA/UVB. The dose varies by skin type and it is then read at 24 hours. The majority of patients with photosensitive AD are reported to have a normal MED; however, some studies have reported the MED to be decreased.5,7-9 ten Berge et al5 found 7% of their study participants exhibited a lower MED, as seen in our patient.

The minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA is defined as the least exposure dose of UVA 1 hour after ingestion of 0.4 mg/kg of methoxsalen that produces pink erythema with 4 distinct borders at 48, 72, or 96 hours after ingestion.10 Visible light exposure is tested using a slide projector as the light source to an approximately 10×5-cm area of skin for 45 minutes. Any immediate or delayed reaction is abnormal and considered positive.10

Photoprovocation testing has been performed in several studies.2,5 It consists of exposing an 8-cm area of skin to 80 J/cm2 UVA and 10 mJ/cm2 UVB, which is read at 24, 48, or 72 hours. A papular or eczematous reaction is considered positive.2,11

The results of phototesting have varied between studies. ten Berge et al5 phototested 107 patients with AD and photosensitivity and 17% were found to be solely sensitive to UVA whereas 67% were found to be sensitive to UVA and UVB. In contrast, Ellenbogen et al2 only tested 17 patients with AD and photosensitivity and they found that 56% (9/16) were sensitive to UVA alone while only 44% (7/16) were sensitive to UVA and UVB.

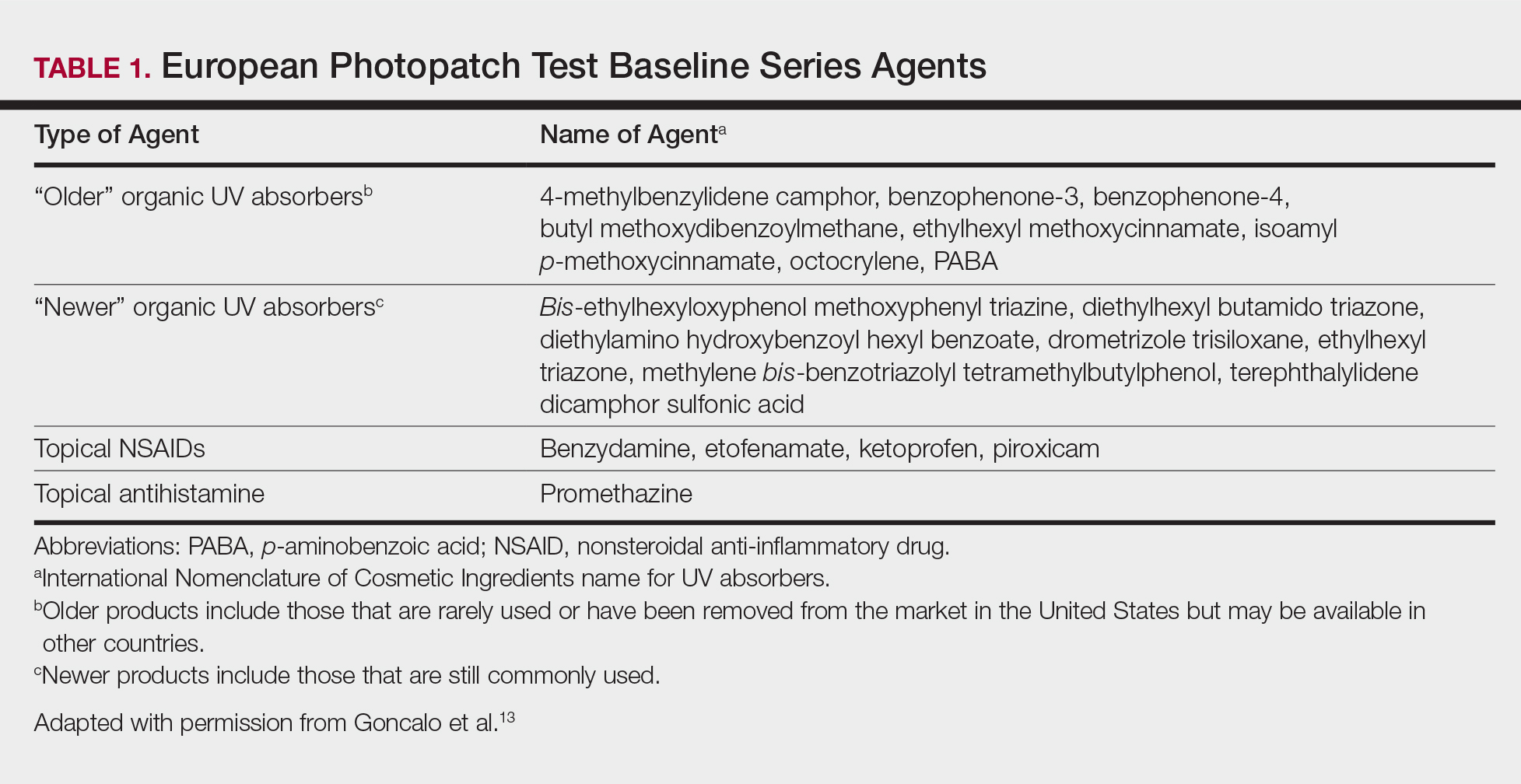

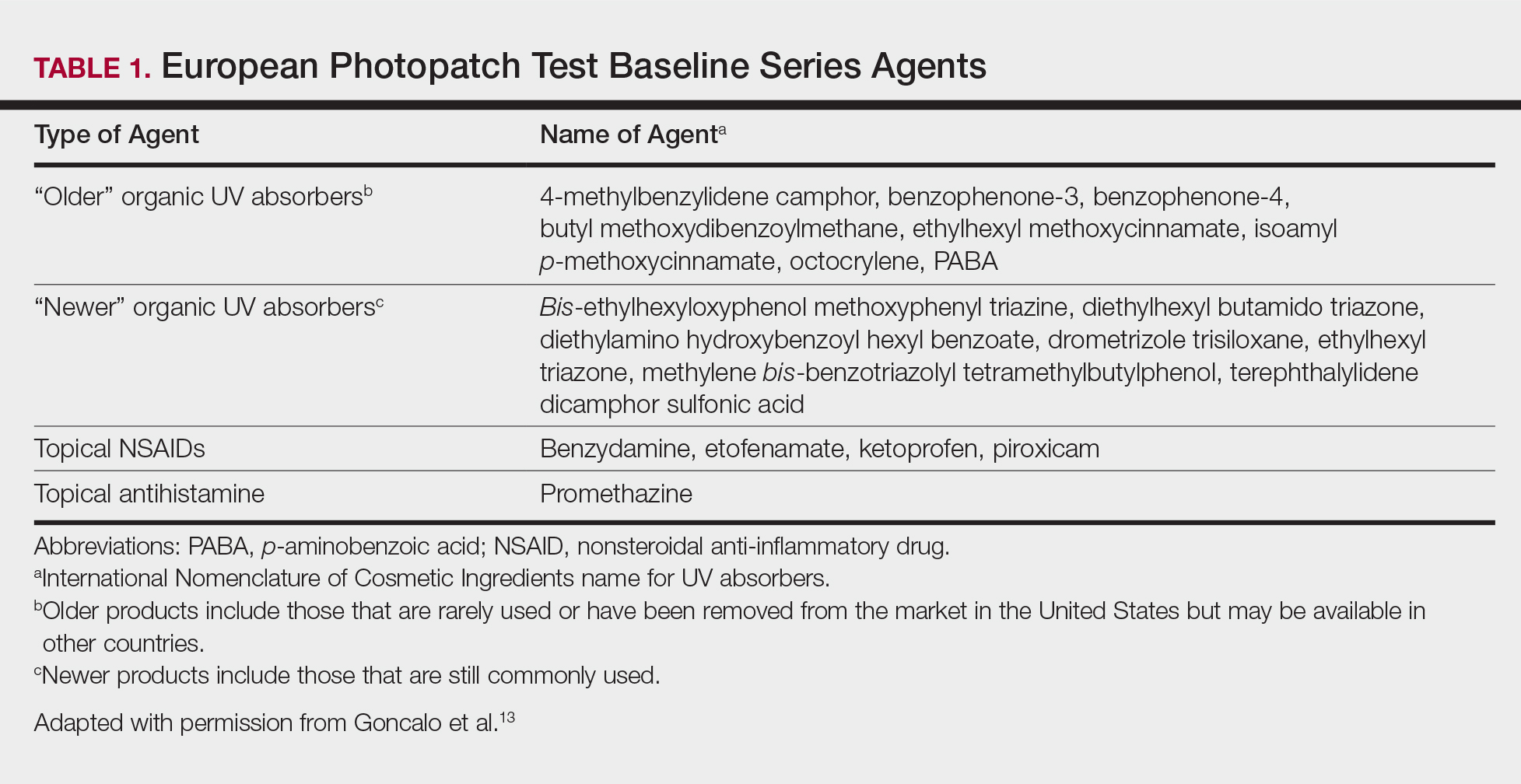

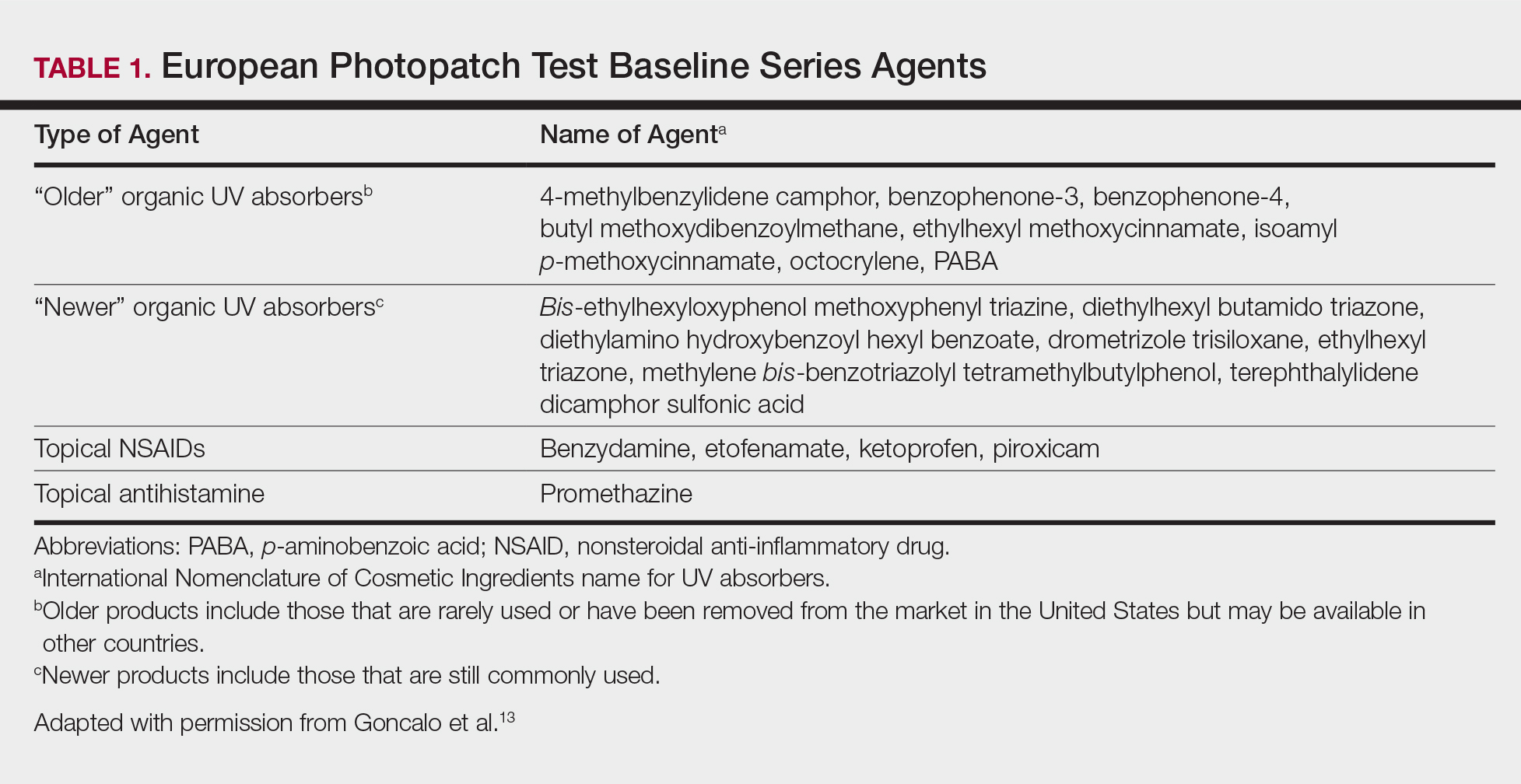

Photopatch testing can help to rule out photosensitivity due to a substance in the presence of UV light. In studies of patients with photosensitive AD (N=125), photocontact reactions occurred in 23% and were predominantly associated with sunscreens, skin care products, and fragrances.5,12 Photopatch testing is done by placing duplicate sets of patches on nonlesional skin using the Finn Chamber technique. A published list of allergens, which were agreed upon by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis and the European Society for Photodermatology in 2000 are seen in Table 1.13 The list contains mainly UV filters and drugs. The patients’ own products also should be tested in addition to the published list of allergens, but a maximum of 30 patches should be placed at one time. The patches are removed at either 24 or 48 hours; some researchers have found greater sensitivity with the 48-hour time period, while others have not found a significant difference.10 One set of skin fields then is covered with an impermeable occlusive dressing as a control while the other is irradiated with 5 J/cm2 of a broad-spectrum UVA light source. UVA fluorescent lamps are the light source of choice because of their widespread availability, reproducible broad spectrum, and beam uniformity.10 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 photopatch testing was performed on 125 patients, and 29 patients were found to be positive to one or more substances. Ellenbogen et al2 photopatch tested 5 patients with photosensitive AD and a clinical suspicion of photoallergy; however, all 5 were negative. Our patient underwent traditional patch testing due to clinical suspicion of a coexisting contact allergy, which was negative.

Differential Diagnosis

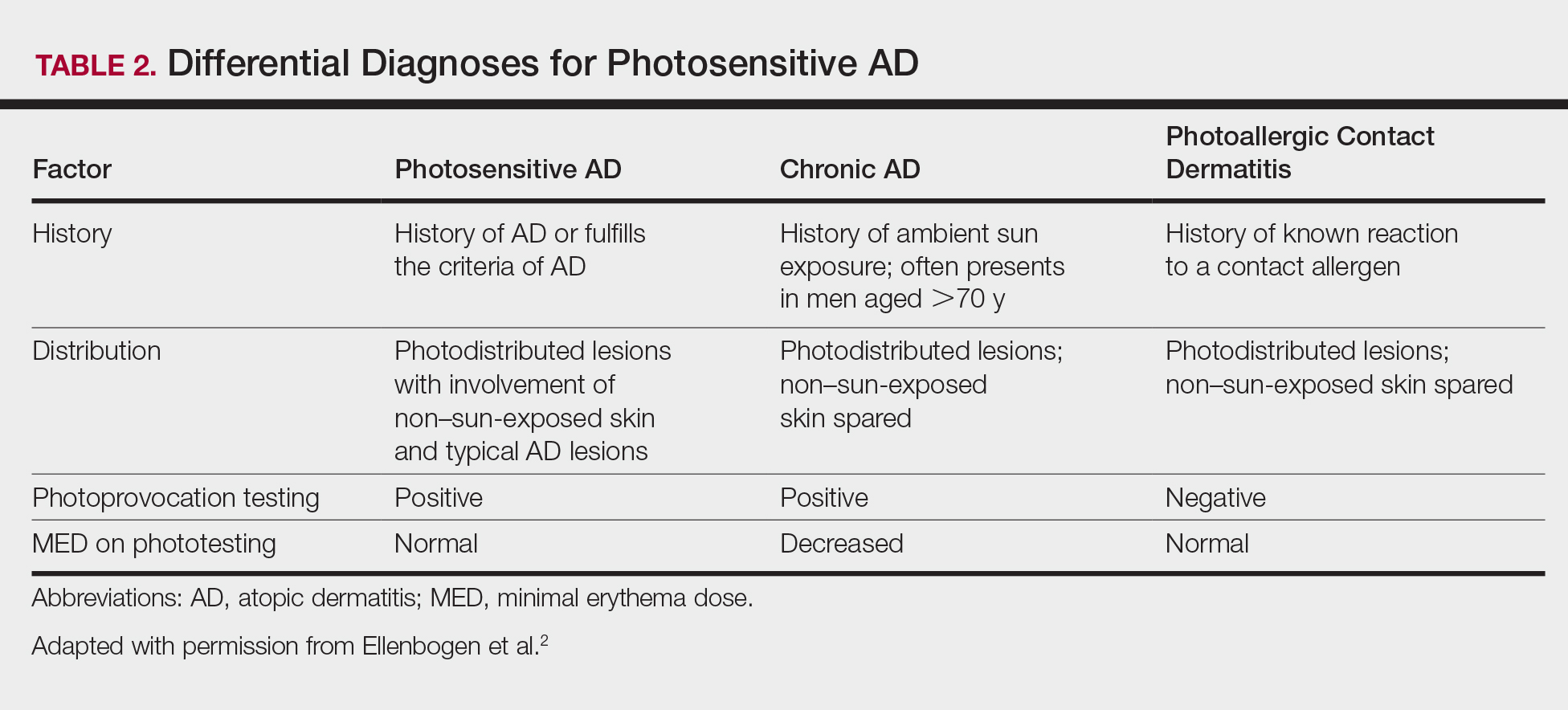

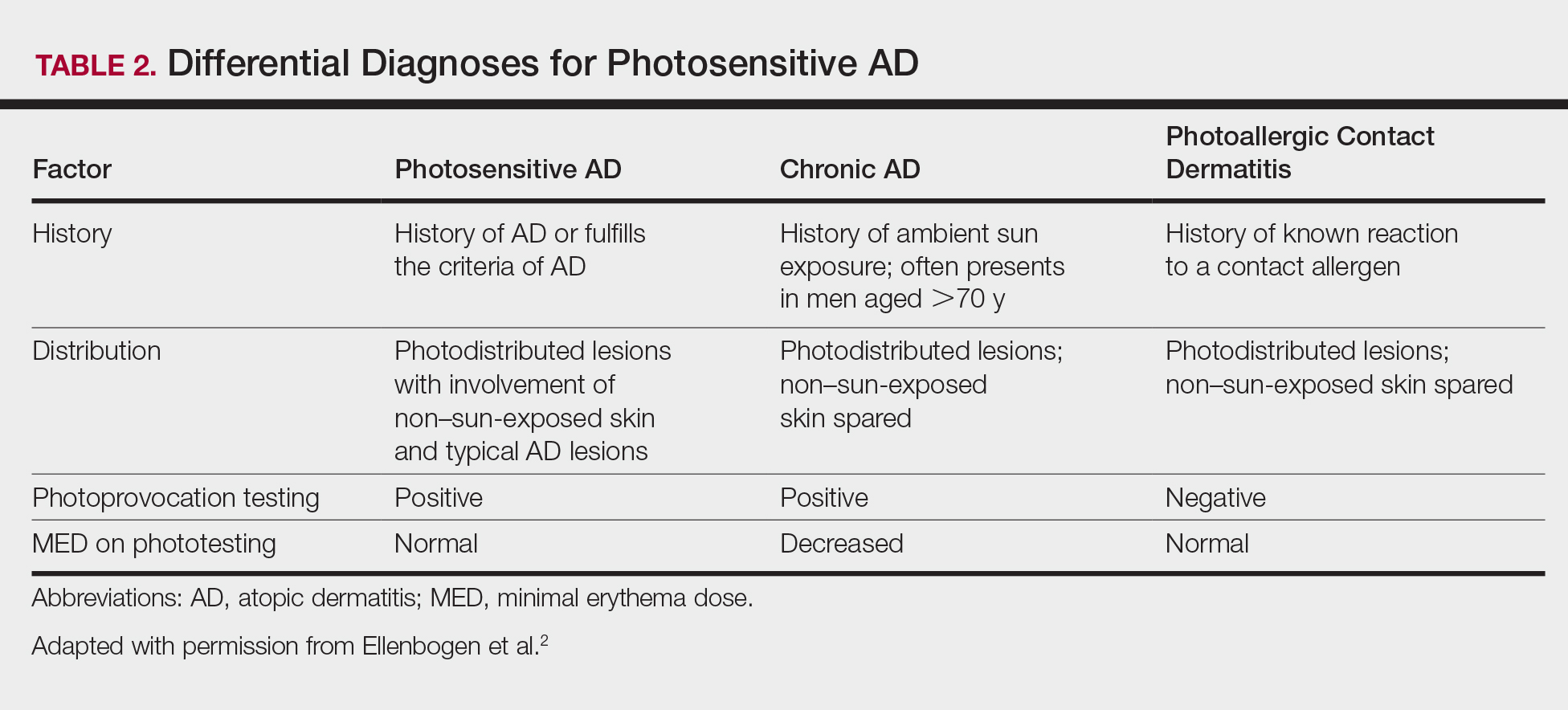

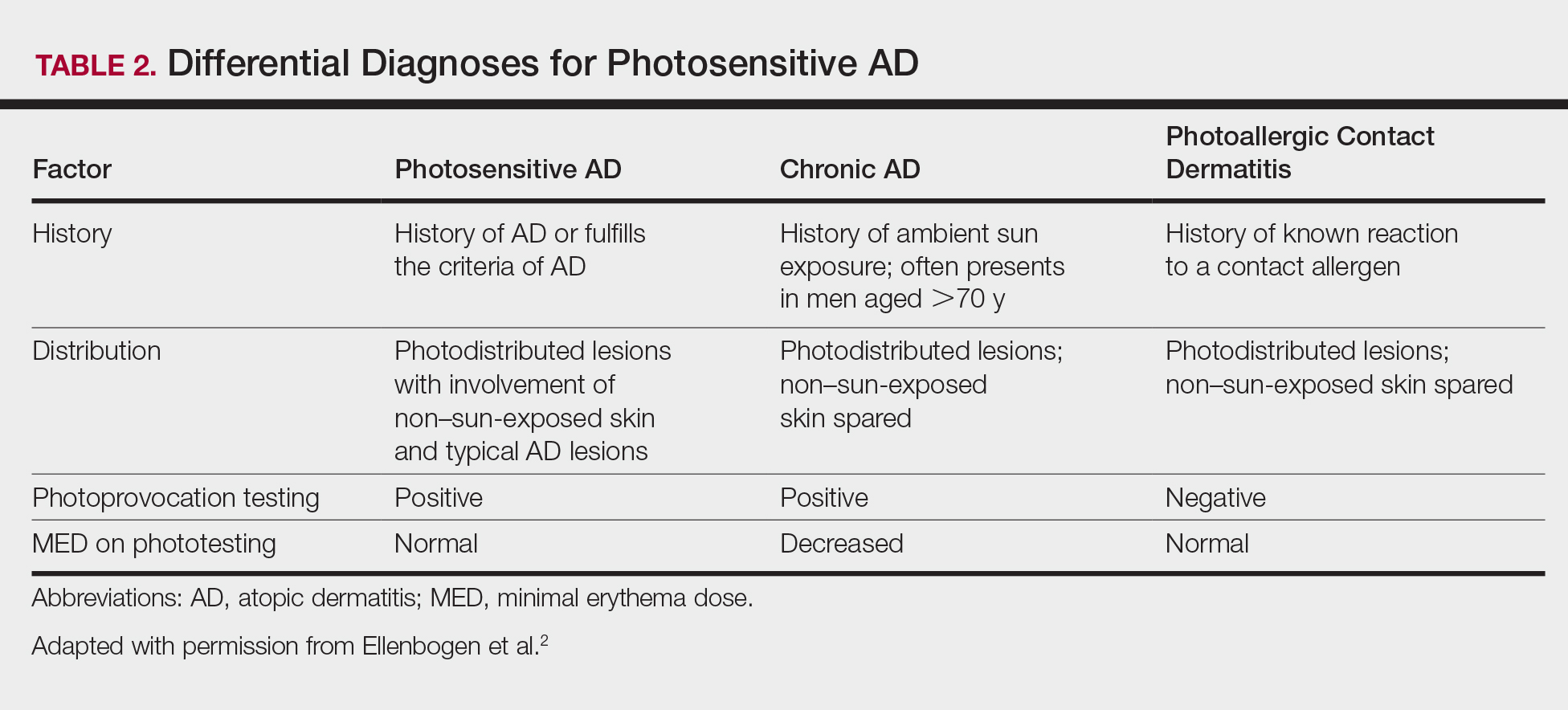

The differential diagnosis for photosensitive AD includes PMLE with coexisting AD, chronic AD, and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photosensitive AD worsens with increasing exposure to uncontrolled sunlight, in contrast to patients with PMLE who experience UV radiation (UVR) hardening with increasing UV exposure during the summer months, resulting in improvement of skin lesions. Patients with chronic AD generally report a history of chronic ambient sun exposure and exhibit well-demarcated eczematous lesions in a photodistributed pattern with sparing of sun-protected skin.2 In contrast, photosensitive AD involves both sun-exposed and covered areas of the body. Chronic AD will have a positive photoprovocation test with a decreased MED (Table 2). Photoallergic contact dermatitis also will have photodistributed eczematous lesions with relative sparing of non–sun-exposed skin; however, these patients generally have negative photoprovocation testing with a normal MED.2 These patients may or may not have a history of reaction to a known allergen, but they likely will have a positive photopatch test.

Treatment

The treatment of photosensitive AD is based on the severity of the photosensitivity. Treatment for mild disease is limited to sun protection in addition to topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors. For moderate disease and unsatisfactory relief with proper sun protection, UVR hardening is recommended. If severe disease is present, immunosuppression with medications such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil is suggested to prevent flaring of disease during UVR hardening.2,5,8,14

Conclusion

Photosensitive AD is a rare entity characterized by a photodistributed rash and involvement of non–sun-exposed skin. Patients will either have a history of AD or fulfill the criteria of AD. They have positive photoprovocation testing and generally have a normal MED. They may have positive photopatch testing with coexisting photoallergies. Histopathology is nonspecific but shows spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Diagnosis is essential, as this disease can be life altering and affect quality of life. Effective treatment options are available, and the therapeutic ladder is based on severity of disease.2,5

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:203-230.

- Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, et al. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270-275.

- Yule S, Dawe RS, Cameron H, et al. Does narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy work in atopic dermatitis through a local or a systemic effect? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:333-335.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119-123.

- O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398.

- Crouch RB, Foley PA, Baker CS. Analysis of patients with suspected photosensitivity referred for investigation to an Australian photodermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:714-720.

- Russell SC, Dawes RS, Collins P, et al. The photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome (chronic actinic dermatitis) occurring in seven young atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:496-501.

- Tajima T, Ibe M, Matsushita T, et al. A variety of skin responses to ultraviolet irradiation in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;17:101-107.

- Faurschou A, Wulf HC. European Dermatology Guideline for the photodermatoses: phototesting. European Dermatology Forum website. http://www.euroderm.org/edf/index.php/edf-guidelines/category/3-guidelines-on-photodermatoses. Accessed August 21, 2017.

- Keong CH, Kurumaji Y, Miyamoto C, et al. Photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: demonstration of abnormal response to UVB. J Dermatol. 1992;19:342-347.

- Lee PA, Freeman S. Photosensitivity: the 9-year experience at a Sydney contact dermatitis clinic. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:289-292.

- Goncalo M, Ferguson J, Bonevalle A, et al. Photopatch testing: recommendations for a European photopatch test baseline series. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:239-243.

- Amon U, Mangalo S, Roth A. Clinical relevance of increased UV-sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB39.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of the global population.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic relapsing dermatitis with pruritus, often beginning in infancy or childhood. Atopic dermatitis is caused by a defect in epidermal barrier function, which results in increased transepidermal water loss.1 The criteria for AD include a pruritic skin condition plus 3 or more of the following: history of involvement of the skin creases, history of asthma or hay fever, history of AD in a first-degree relative (in children), 1-year history of generally dry skin, visible flexural eczema, and an age of onset of less than 2 years. Adults with AD frequently present with hand or facial dermatitis.1

UV light therapies including narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) have all been used as effective treatments of AD.3,4 UV light is beneficial for AD patients due to its immunomodulatory effects, thickening of the stratum corneum, and the reduction of Staphylococcus aureus in the skin.2 Most patients with AD improve with light therapy; however, it is estimated that 1% to 3% of patients with AD will experience a paradoxical worsening of their AD after exposure to UV light.2,5 This condition is referred to as photosensitive AD and is characterized by a photodistributed rash in patients who fulfill the criteria of AD. Photosensitive AD has a female predominance and generally affects patients with late-onset disease with development of AD after puberty.2,5 The pathogenesis for the development of photosensitivity in patients with AD who previously tolerated exposure to sunlight is unknown.5 We describe a case of photosensitive AD exacerbated by UVB exposure.

Case Report

On physical examination the patient had thin, well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with scaling, primarily on sun-exposed skin on the forehead (Figure 1A), cheeks (Figure 1B), eyelids, upper lip, neck (Figures 1B and 1C), upper chest (Figure 1C), and dorsal aspect of the hands, with excoriated pink papules on the forearms, shoulders, and back. A punch biopsy of the right neck showed spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Further workup was pursued including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, liver function panel, Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B test, antinuclear antibody test, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antigen/antibody test, hepatitis panel, and mycobacterium tuberculosis test, which were all within reference range. Photodermatosis was suspected and she underwent phototesting including UVA, NB-UVB, and visible light. Phototesting confirmed she had a UVB photosensitivity with a markedly decreased minimal erythema dose (MED) to NB-UVB. The MED to NB-UVB was positive at 24 hours to all tested sites, the lowest of which was 0.135 J/cm2. Eczematous changes began to develop at day 6 at doses of 0.945 and 1.080 J/cm2. The patient also underwent visible light testing, which was negative. The patient was patch tested for multiple standardized agents as well as personal products, all of which were negative. Subsequent photopatch testing revealed a slightly positive reaction to benzophenone 4, a common ingredient in sunscreens.

The patient was then started on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Repeat MED testing to NB-UVB was performed. Her repeat MED to NB-UVB was determined to be 0.405 J/cm2, and hardening commenced at 3 times per week at 70% of the MED (0.2835 J/cm2). She began to flare and develop an eczematous reaction, thus the dose was decreased to 50% of the MED (0.2025 J/cm2), which she tolerated.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The literature on photosensitive AD is scant, and this disease entity is rare. Alternative names include photoaggravated AD, photosensitive eczema, and light-exacerbated eczema.5 Two main studies have been conducted in recent years that were intended to characterize photosensitive AD. ten Berge et al5 conducted a retrospective study of 145 patients with AD that were phototested in 2009. They found that 3% of their total AD patient population had photosensitive AD.5 In 2016, Ellenbogen et al2 performed a similar single-center retrospective analysis of 17 patients with long-standing AD who suddenly developed photosensitivity.

Patients with photosensitive AD typically present with lesions on sun-exposed skin with coexisting eczematous lesions in sites with a predilection for AD.2 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 2 main reaction patterns were observed: erythematous papules with pruritus and an eczematous reaction.

Histopathology

The histopathologic findings of photosensitive AD are nonspecific but are characterized by spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2

Diagnosis With Phototesting

Phototesting of patients with AD should be considered if there is a suspicion for photosensitivity based on persistent disease despite use of photoprotection and local treatment.5-7 Patients may not notice a correlation of skin exacerbations with UV exposure, especially if they are only sensitive to UVA, as it is still present on cloudy days and can penetrate glass windows.8 Phototesting evaluates the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response. Phototesting consists of determining the MED to UVA and UVB, the minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA, and visible light exposure. Further evaluation may include photoprovocation testing or photopatch testing, as these patients can have coexisting photocontact allergies.

The MED is defined as the minimal dose of UV light needed to induce perceptible erythema in exposed skin.5 It is dependent on the light source and patient’s skin type, and individual units may vary. To determine the MED to UVA or UVB, 2×2-cm skin fields are irradiated with increasing cumulative UVA/UVB. The dose varies by skin type and it is then read at 24 hours. The majority of patients with photosensitive AD are reported to have a normal MED; however, some studies have reported the MED to be decreased.5,7-9 ten Berge et al5 found 7% of their study participants exhibited a lower MED, as seen in our patient.

The minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA is defined as the least exposure dose of UVA 1 hour after ingestion of 0.4 mg/kg of methoxsalen that produces pink erythema with 4 distinct borders at 48, 72, or 96 hours after ingestion.10 Visible light exposure is tested using a slide projector as the light source to an approximately 10×5-cm area of skin for 45 minutes. Any immediate or delayed reaction is abnormal and considered positive.10

Photoprovocation testing has been performed in several studies.2,5 It consists of exposing an 8-cm area of skin to 80 J/cm2 UVA and 10 mJ/cm2 UVB, which is read at 24, 48, or 72 hours. A papular or eczematous reaction is considered positive.2,11

The results of phototesting have varied between studies. ten Berge et al5 phototested 107 patients with AD and photosensitivity and 17% were found to be solely sensitive to UVA whereas 67% were found to be sensitive to UVA and UVB. In contrast, Ellenbogen et al2 only tested 17 patients with AD and photosensitivity and they found that 56% (9/16) were sensitive to UVA alone while only 44% (7/16) were sensitive to UVA and UVB.

Photopatch testing can help to rule out photosensitivity due to a substance in the presence of UV light. In studies of patients with photosensitive AD (N=125), photocontact reactions occurred in 23% and were predominantly associated with sunscreens, skin care products, and fragrances.5,12 Photopatch testing is done by placing duplicate sets of patches on nonlesional skin using the Finn Chamber technique. A published list of allergens, which were agreed upon by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis and the European Society for Photodermatology in 2000 are seen in Table 1.13 The list contains mainly UV filters and drugs. The patients’ own products also should be tested in addition to the published list of allergens, but a maximum of 30 patches should be placed at one time. The patches are removed at either 24 or 48 hours; some researchers have found greater sensitivity with the 48-hour time period, while others have not found a significant difference.10 One set of skin fields then is covered with an impermeable occlusive dressing as a control while the other is irradiated with 5 J/cm2 of a broad-spectrum UVA light source. UVA fluorescent lamps are the light source of choice because of their widespread availability, reproducible broad spectrum, and beam uniformity.10 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 photopatch testing was performed on 125 patients, and 29 patients were found to be positive to one or more substances. Ellenbogen et al2 photopatch tested 5 patients with photosensitive AD and a clinical suspicion of photoallergy; however, all 5 were negative. Our patient underwent traditional patch testing due to clinical suspicion of a coexisting contact allergy, which was negative.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for photosensitive AD includes PMLE with coexisting AD, chronic AD, and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photosensitive AD worsens with increasing exposure to uncontrolled sunlight, in contrast to patients with PMLE who experience UV radiation (UVR) hardening with increasing UV exposure during the summer months, resulting in improvement of skin lesions. Patients with chronic AD generally report a history of chronic ambient sun exposure and exhibit well-demarcated eczematous lesions in a photodistributed pattern with sparing of sun-protected skin.2 In contrast, photosensitive AD involves both sun-exposed and covered areas of the body. Chronic AD will have a positive photoprovocation test with a decreased MED (Table 2). Photoallergic contact dermatitis also will have photodistributed eczematous lesions with relative sparing of non–sun-exposed skin; however, these patients generally have negative photoprovocation testing with a normal MED.2 These patients may or may not have a history of reaction to a known allergen, but they likely will have a positive photopatch test.

Treatment

The treatment of photosensitive AD is based on the severity of the photosensitivity. Treatment for mild disease is limited to sun protection in addition to topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors. For moderate disease and unsatisfactory relief with proper sun protection, UVR hardening is recommended. If severe disease is present, immunosuppression with medications such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil is suggested to prevent flaring of disease during UVR hardening.2,5,8,14

Conclusion

Photosensitive AD is a rare entity characterized by a photodistributed rash and involvement of non–sun-exposed skin. Patients will either have a history of AD or fulfill the criteria of AD. They have positive photoprovocation testing and generally have a normal MED. They may have positive photopatch testing with coexisting photoallergies. Histopathology is nonspecific but shows spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Diagnosis is essential, as this disease can be life altering and affect quality of life. Effective treatment options are available, and the therapeutic ladder is based on severity of disease.2,5

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of the global population.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic relapsing dermatitis with pruritus, often beginning in infancy or childhood. Atopic dermatitis is caused by a defect in epidermal barrier function, which results in increased transepidermal water loss.1 The criteria for AD include a pruritic skin condition plus 3 or more of the following: history of involvement of the skin creases, history of asthma or hay fever, history of AD in a first-degree relative (in children), 1-year history of generally dry skin, visible flexural eczema, and an age of onset of less than 2 years. Adults with AD frequently present with hand or facial dermatitis.1

UV light therapies including narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) have all been used as effective treatments of AD.3,4 UV light is beneficial for AD patients due to its immunomodulatory effects, thickening of the stratum corneum, and the reduction of Staphylococcus aureus in the skin.2 Most patients with AD improve with light therapy; however, it is estimated that 1% to 3% of patients with AD will experience a paradoxical worsening of their AD after exposure to UV light.2,5 This condition is referred to as photosensitive AD and is characterized by a photodistributed rash in patients who fulfill the criteria of AD. Photosensitive AD has a female predominance and generally affects patients with late-onset disease with development of AD after puberty.2,5 The pathogenesis for the development of photosensitivity in patients with AD who previously tolerated exposure to sunlight is unknown.5 We describe a case of photosensitive AD exacerbated by UVB exposure.

Case Report

On physical examination the patient had thin, well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with scaling, primarily on sun-exposed skin on the forehead (Figure 1A), cheeks (Figure 1B), eyelids, upper lip, neck (Figures 1B and 1C), upper chest (Figure 1C), and dorsal aspect of the hands, with excoriated pink papules on the forearms, shoulders, and back. A punch biopsy of the right neck showed spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Further workup was pursued including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, liver function panel, Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B test, antinuclear antibody test, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antigen/antibody test, hepatitis panel, and mycobacterium tuberculosis test, which were all within reference range. Photodermatosis was suspected and she underwent phototesting including UVA, NB-UVB, and visible light. Phototesting confirmed she had a UVB photosensitivity with a markedly decreased minimal erythema dose (MED) to NB-UVB. The MED to NB-UVB was positive at 24 hours to all tested sites, the lowest of which was 0.135 J/cm2. Eczematous changes began to develop at day 6 at doses of 0.945 and 1.080 J/cm2. The patient also underwent visible light testing, which was negative. The patient was patch tested for multiple standardized agents as well as personal products, all of which were negative. Subsequent photopatch testing revealed a slightly positive reaction to benzophenone 4, a common ingredient in sunscreens.

The patient was then started on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Repeat MED testing to NB-UVB was performed. Her repeat MED to NB-UVB was determined to be 0.405 J/cm2, and hardening commenced at 3 times per week at 70% of the MED (0.2835 J/cm2). She began to flare and develop an eczematous reaction, thus the dose was decreased to 50% of the MED (0.2025 J/cm2), which she tolerated.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The literature on photosensitive AD is scant, and this disease entity is rare. Alternative names include photoaggravated AD, photosensitive eczema, and light-exacerbated eczema.5 Two main studies have been conducted in recent years that were intended to characterize photosensitive AD. ten Berge et al5 conducted a retrospective study of 145 patients with AD that were phototested in 2009. They found that 3% of their total AD patient population had photosensitive AD.5 In 2016, Ellenbogen et al2 performed a similar single-center retrospective analysis of 17 patients with long-standing AD who suddenly developed photosensitivity.

Patients with photosensitive AD typically present with lesions on sun-exposed skin with coexisting eczematous lesions in sites with a predilection for AD.2 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 2 main reaction patterns were observed: erythematous papules with pruritus and an eczematous reaction.

Histopathology

The histopathologic findings of photosensitive AD are nonspecific but are characterized by spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2

Diagnosis With Phototesting

Phototesting of patients with AD should be considered if there is a suspicion for photosensitivity based on persistent disease despite use of photoprotection and local treatment.5-7 Patients may not notice a correlation of skin exacerbations with UV exposure, especially if they are only sensitive to UVA, as it is still present on cloudy days and can penetrate glass windows.8 Phototesting evaluates the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response. Phototesting consists of determining the MED to UVA and UVB, the minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA, and visible light exposure. Further evaluation may include photoprovocation testing or photopatch testing, as these patients can have coexisting photocontact allergies.

The MED is defined as the minimal dose of UV light needed to induce perceptible erythema in exposed skin.5 It is dependent on the light source and patient’s skin type, and individual units may vary. To determine the MED to UVA or UVB, 2×2-cm skin fields are irradiated with increasing cumulative UVA/UVB. The dose varies by skin type and it is then read at 24 hours. The majority of patients with photosensitive AD are reported to have a normal MED; however, some studies have reported the MED to be decreased.5,7-9 ten Berge et al5 found 7% of their study participants exhibited a lower MED, as seen in our patient.

The minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA is defined as the least exposure dose of UVA 1 hour after ingestion of 0.4 mg/kg of methoxsalen that produces pink erythema with 4 distinct borders at 48, 72, or 96 hours after ingestion.10 Visible light exposure is tested using a slide projector as the light source to an approximately 10×5-cm area of skin for 45 minutes. Any immediate or delayed reaction is abnormal and considered positive.10

Photoprovocation testing has been performed in several studies.2,5 It consists of exposing an 8-cm area of skin to 80 J/cm2 UVA and 10 mJ/cm2 UVB, which is read at 24, 48, or 72 hours. A papular or eczematous reaction is considered positive.2,11

The results of phototesting have varied between studies. ten Berge et al5 phototested 107 patients with AD and photosensitivity and 17% were found to be solely sensitive to UVA whereas 67% were found to be sensitive to UVA and UVB. In contrast, Ellenbogen et al2 only tested 17 patients with AD and photosensitivity and they found that 56% (9/16) were sensitive to UVA alone while only 44% (7/16) were sensitive to UVA and UVB.

Photopatch testing can help to rule out photosensitivity due to a substance in the presence of UV light. In studies of patients with photosensitive AD (N=125), photocontact reactions occurred in 23% and were predominantly associated with sunscreens, skin care products, and fragrances.5,12 Photopatch testing is done by placing duplicate sets of patches on nonlesional skin using the Finn Chamber technique. A published list of allergens, which were agreed upon by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis and the European Society for Photodermatology in 2000 are seen in Table 1.13 The list contains mainly UV filters and drugs. The patients’ own products also should be tested in addition to the published list of allergens, but a maximum of 30 patches should be placed at one time. The patches are removed at either 24 or 48 hours; some researchers have found greater sensitivity with the 48-hour time period, while others have not found a significant difference.10 One set of skin fields then is covered with an impermeable occlusive dressing as a control while the other is irradiated with 5 J/cm2 of a broad-spectrum UVA light source. UVA fluorescent lamps are the light source of choice because of their widespread availability, reproducible broad spectrum, and beam uniformity.10 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 photopatch testing was performed on 125 patients, and 29 patients were found to be positive to one or more substances. Ellenbogen et al2 photopatch tested 5 patients with photosensitive AD and a clinical suspicion of photoallergy; however, all 5 were negative. Our patient underwent traditional patch testing due to clinical suspicion of a coexisting contact allergy, which was negative.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for photosensitive AD includes PMLE with coexisting AD, chronic AD, and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photosensitive AD worsens with increasing exposure to uncontrolled sunlight, in contrast to patients with PMLE who experience UV radiation (UVR) hardening with increasing UV exposure during the summer months, resulting in improvement of skin lesions. Patients with chronic AD generally report a history of chronic ambient sun exposure and exhibit well-demarcated eczematous lesions in a photodistributed pattern with sparing of sun-protected skin.2 In contrast, photosensitive AD involves both sun-exposed and covered areas of the body. Chronic AD will have a positive photoprovocation test with a decreased MED (Table 2). Photoallergic contact dermatitis also will have photodistributed eczematous lesions with relative sparing of non–sun-exposed skin; however, these patients generally have negative photoprovocation testing with a normal MED.2 These patients may or may not have a history of reaction to a known allergen, but they likely will have a positive photopatch test.

Treatment

The treatment of photosensitive AD is based on the severity of the photosensitivity. Treatment for mild disease is limited to sun protection in addition to topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors. For moderate disease and unsatisfactory relief with proper sun protection, UVR hardening is recommended. If severe disease is present, immunosuppression with medications such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil is suggested to prevent flaring of disease during UVR hardening.2,5,8,14

Conclusion

Photosensitive AD is a rare entity characterized by a photodistributed rash and involvement of non–sun-exposed skin. Patients will either have a history of AD or fulfill the criteria of AD. They have positive photoprovocation testing and generally have a normal MED. They may have positive photopatch testing with coexisting photoallergies. Histopathology is nonspecific but shows spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Diagnosis is essential, as this disease can be life altering and affect quality of life. Effective treatment options are available, and the therapeutic ladder is based on severity of disease.2,5

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:203-230.

- Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, et al. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270-275.

- Yule S, Dawe RS, Cameron H, et al. Does narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy work in atopic dermatitis through a local or a systemic effect? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:333-335.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119-123.

- O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398.

- Crouch RB, Foley PA, Baker CS. Analysis of patients with suspected photosensitivity referred for investigation to an Australian photodermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:714-720.

- Russell SC, Dawes RS, Collins P, et al. The photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome (chronic actinic dermatitis) occurring in seven young atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:496-501.

- Tajima T, Ibe M, Matsushita T, et al. A variety of skin responses to ultraviolet irradiation in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;17:101-107.

- Faurschou A, Wulf HC. European Dermatology Guideline for the photodermatoses: phototesting. European Dermatology Forum website. http://www.euroderm.org/edf/index.php/edf-guidelines/category/3-guidelines-on-photodermatoses. Accessed August 21, 2017.

- Keong CH, Kurumaji Y, Miyamoto C, et al. Photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: demonstration of abnormal response to UVB. J Dermatol. 1992;19:342-347.

- Lee PA, Freeman S. Photosensitivity: the 9-year experience at a Sydney contact dermatitis clinic. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:289-292.

- Goncalo M, Ferguson J, Bonevalle A, et al. Photopatch testing: recommendations for a European photopatch test baseline series. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:239-243.

- Amon U, Mangalo S, Roth A. Clinical relevance of increased UV-sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB39.

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:203-230.

- Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, et al. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270-275.

- Yule S, Dawe RS, Cameron H, et al. Does narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy work in atopic dermatitis through a local or a systemic effect? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:333-335.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119-123.

- O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398.

- Crouch RB, Foley PA, Baker CS. Analysis of patients with suspected photosensitivity referred for investigation to an Australian photodermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:714-720.

- Russell SC, Dawes RS, Collins P, et al. The photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome (chronic actinic dermatitis) occurring in seven young atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:496-501.

- Tajima T, Ibe M, Matsushita T, et al. A variety of skin responses to ultraviolet irradiation in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;17:101-107.

- Faurschou A, Wulf HC. European Dermatology Guideline for the photodermatoses: phototesting. European Dermatology Forum website. http://www.euroderm.org/edf/index.php/edf-guidelines/category/3-guidelines-on-photodermatoses. Accessed August 21, 2017.

- Keong CH, Kurumaji Y, Miyamoto C, et al. Photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: demonstration of abnormal response to UVB. J Dermatol. 1992;19:342-347.

- Lee PA, Freeman S. Photosensitivity: the 9-year experience at a Sydney contact dermatitis clinic. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:289-292.

- Goncalo M, Ferguson J, Bonevalle A, et al. Photopatch testing: recommendations for a European photopatch test baseline series. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:239-243.

- Amon U, Mangalo S, Roth A. Clinical relevance of increased UV-sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB39.

Practice Points

- Photosensitive atopic dermatitis (AD) is rare but should be considered in patients with uncontrolled AD with a rash on sun-exposed skin.

- A thorough history and physical examination of these patients can provide the necessary clues for further workup.

- Phototesting should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response.

- Photoprovocation and photopatch testing also can be useful to confirm the diagnosis.

Immigrant with stomach pain, distension, nausea, and fever • Dx?

THE CASE

A 34-year-old Eritrean man presented to the emergency department with complaints of diffuse abdominal pain and distention. He had emigrated to the United States 3 months earlier, following 5 years in a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Two weeks earlier, the patient sought care at his primary care clinic and was diagnosed with post-operative urinary retention and constipation following a recent hemorrhoidectomy. A Foley catheter was inserted and provided a short period of relief.

Following the visit, however, his abdominal pain worsened. He also experienced increasing abdominal distention, a declining appetite, and persistent nausea. The patient said that he was unable to urinate and had not had a bowel movement in 6 days. He also described fevers, drenching night sweats, chills, and a 4-kg weight loss over 2 months.

On physical examination, the patient had a wasted appearance. He was afebrile, alert, and oriented, but anxious and writhing in pain. An abdominal examination revealed some distention, generalized guarding, and tenderness. There was dullness to percussion in all regions without rebound, and no caput medusa was noted. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

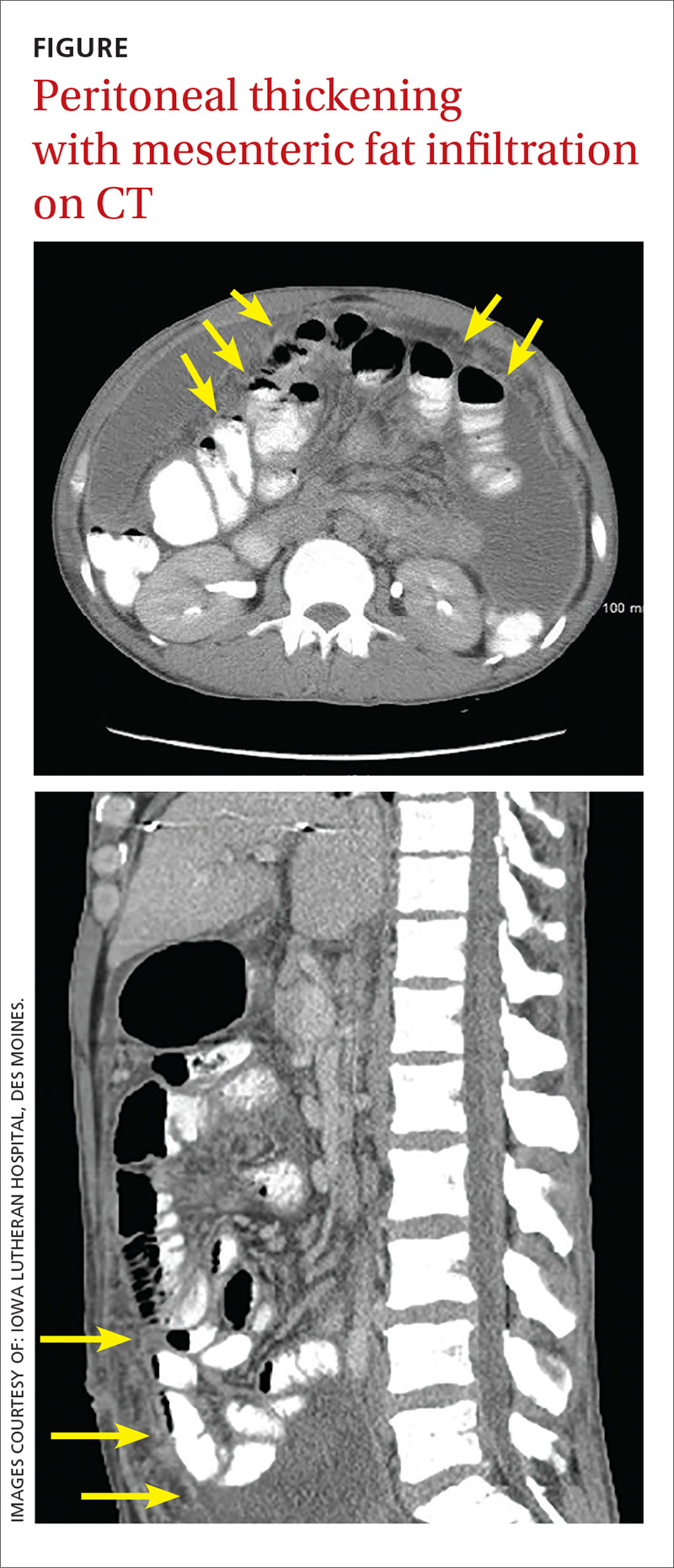

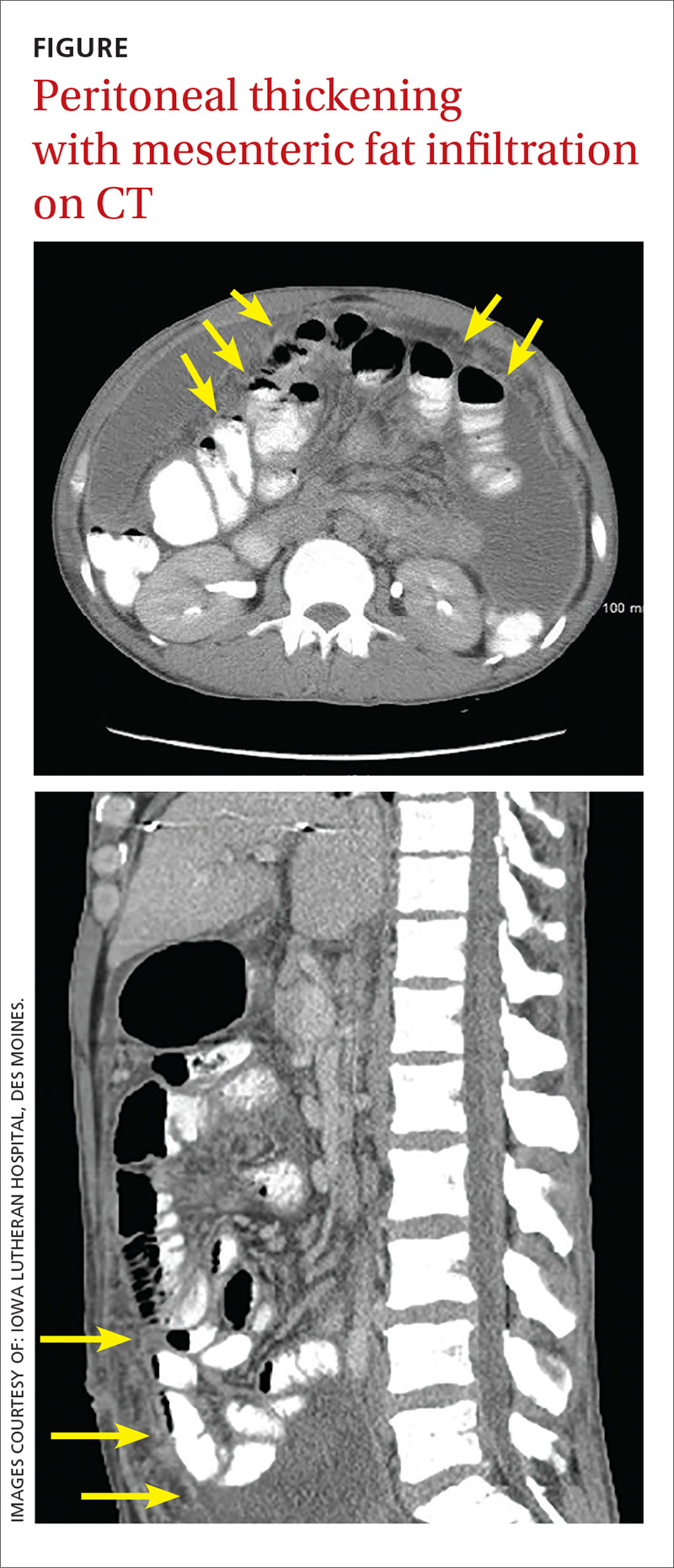

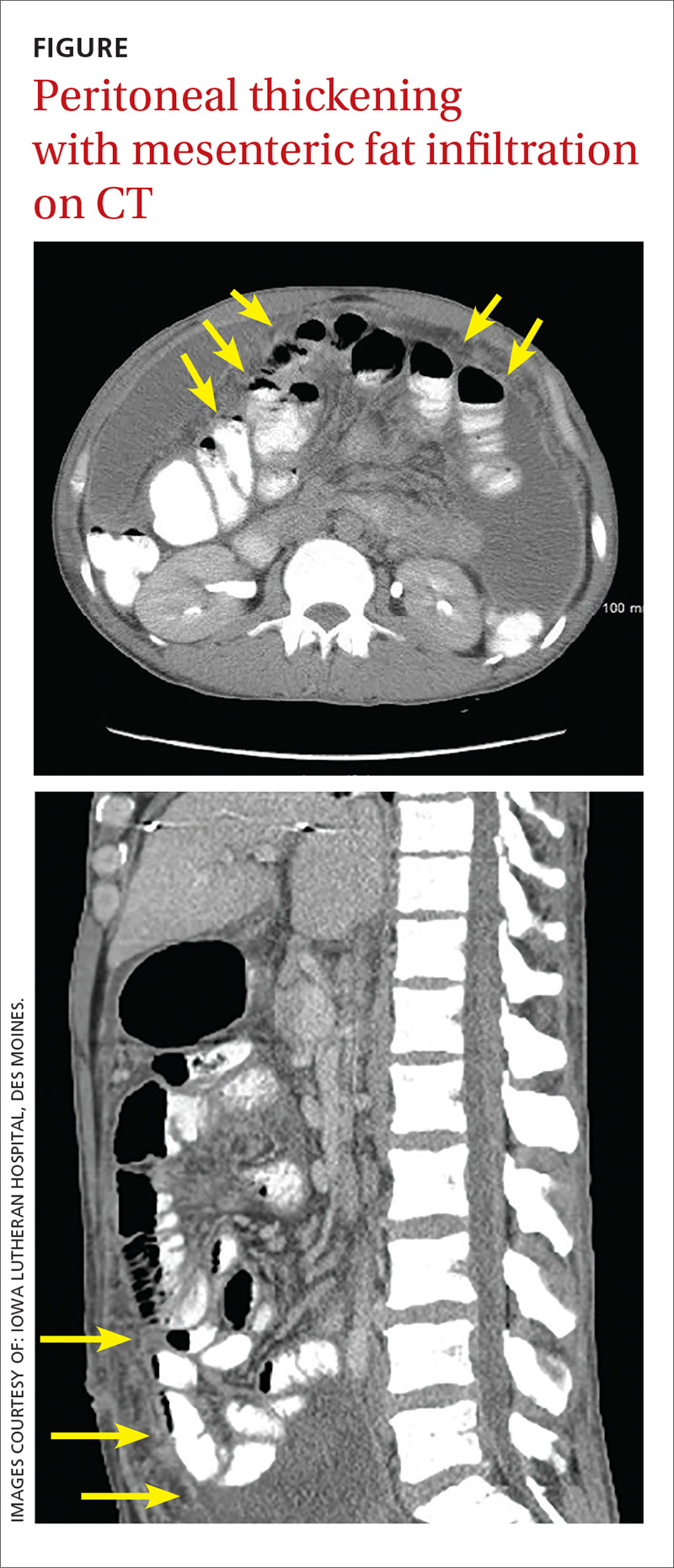

Pertinent laboratory values included negative screens for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and 2, and a purified protein derivative test that produced 10 mm of induration at 48 hours. An interferon-gamma release assay was not performed following these results. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast revealed thickening of the peritoneal lining with infiltration of the mesenteric fat and large loculated fluid collections in the abdominal cavity (FIGURE). A CT scan of the patient’s lungs showed some mild atelectasis with left-sided effusion.

After hospital admission, the patient spiked fevers as high as 103.3° F and developed progressively worsening ascites. An ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed, during which almost 2 liters of yellow, hazy fluid was removed. Fluid and blood cultures were negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

With a high clinical suspicion for tuberculosis (TB) peritonitis, we requested a surgical consultation and a peritoneal biopsy was performed. The patient was started on ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, pyridoxine, and rifampin while the biopsy results were pending.

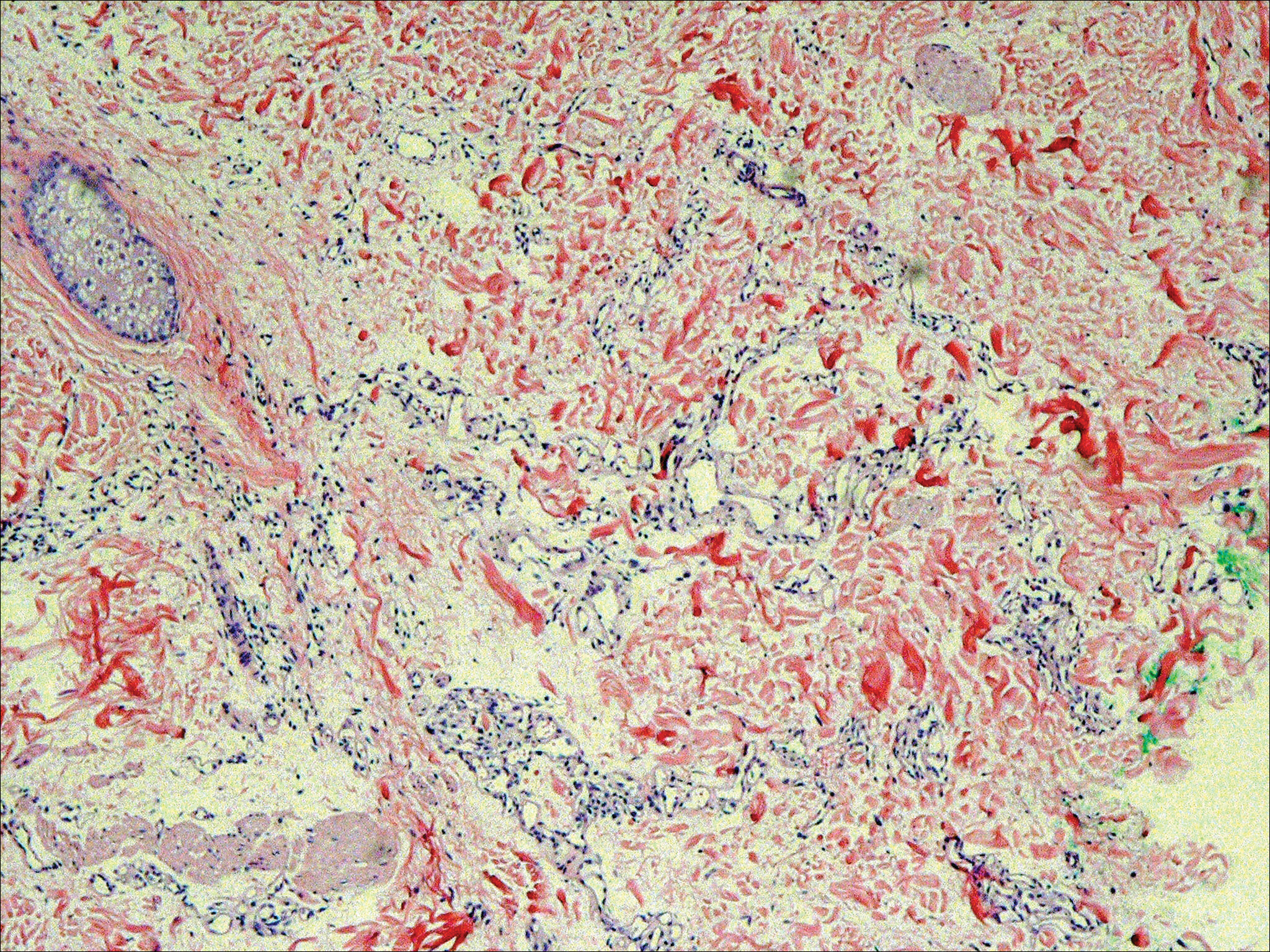

Pathology subsequently confirmed a diagnosis of TB peritonitis, reporting dense fibroconnective tissue with areas of chronic inflammation and occasional accumulations of histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells showing granulomatous inflammation. An acid-fast (AF) bacilli stain for Mycobacteria showed a single curved bacillus compatible with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The patient was discharged following a 3-week hospital stay. At his follow-up visit several weeks later, the patient reported marked improvement and increasing exercise tolerance. He had gained weight, and the abdominal distention and tenderness had resolved.

DISCUSSION

Worldwide, TB is one of the top 10 causes of death. The World Health Organization estimates that there were 1.4 million TB deaths globally in 2015.1 And while rates of TB are decreasing in the United States, there was a resurgence from 1985 to 1992.2 This was attributable to the HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome epidemic, increased immigration from countries endemic for TB, and deterioration of the TB public health infrastructure.3

Transmission. M tuberculosis is a rod-shaped, nonspore-forming AF bacillus that typically infects the lungs, but may infect other areas of the body. Transmission typically occurs via airborne spread of droplets from an infected individual. Possible other methods of disease dissemination include ingestion of infected sputum, hematogenous spread from active pulmonary TB, or ingestion of contaminated milk or food.

M tuberculosis elicits a proinflammatory phase, which facilitates the formation of a granuloma within the host tissues. The host’s immune response to M tuberculosis plays a role in the risk of developing this type of TB.3

TB presentation is classified as pulmonary, extrapulmonary, or both. Clinicians are generally attentive to the classic symptoms of pulmonary TB: cough, weight loss, night sweats, and fever. Presentation of extrapulmonary TB, however, may vary.4

According to one study, the most common presenting symptoms for peritoneal TB are weight loss, abdominal pain, and/or fever, all of which our patient experienced.5 In addition, our patient was an immigrant from Africa, and black patients have been shown to have a significantly higher incidence of extrapulmonary TB than their nonblack counterparts.6 Although our patient was HIV-negative, a recent meta-analysis confirmed the strong association between extrapulmonary TB and HIV, emphasizing the importance of including HIV screens in the standard work-up for TB.7

Other symptoms may include microcytosis, anemia, thrombocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although a chest x-ray is often negative, advanced imaging, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging, is often abnormal and may point to the diagnosis.5

Treatment of extrapulmonary TB is generally the same as that for pulmonary TB and, interestingly, the incidence of multi-drug resistant extrapulmonary TB is not necessarily higher than it is for pulmonary TB (<1% vs 1.6%).3,7 In light of this, a standard regimen—like the one our patient received—is generally utilized for 6 to 9 months. Nonetheless, resistance testing should still be performed.3,4

THE TAKEAWAY

While considered uncommon, more than 20% of TB cases in the United States are extrapulmonary (the most common form is TB lymphadenitis).7,8 It is imperative to identify appropriate risk factors, including associated comorbidities, patient characteristics, and population/endemic differences in immigrant populations.

In this case, although the symptom combination of persistent abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss may not trigger suspicion of a TB diagnosis in isolation, combining the symptoms with knowledge of the patient’s immigration status should at least raise an eyebrow. Given their nonpulmonary symptoms, many of these patients will not present to pulmonologists, making diagnosis particularly relevant to primary care.

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2016_executive_summary.pdf?ua=1. Accessed August 22, 2017.

2. Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1350-1357.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2006. Available at: http://digitallibrary.utah.gov/awweb/awarchive?type=file&item=56908. Accessed August 3, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19908en/s19908en.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2017.

5. Ramesh J, Banait GS, Ormerod LP. Abdominal tuberculosis in a district general hospital: a retrospective review of 86 cases. QJM. 2008;101:189-195.

6. Fiske CT, Griffin MR, Erin H, et al. Black race, sex and extrapulmonary tuberculosis risk: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:16.

7. Naing C, Mak JW, Maung M, et al. Meta-analysis: the association between HIV infection and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Lung. 2013;191:27-34.

8. Neelakantan S, Nair PP, Emmanuel RV, et al. Diversities in presentations of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013.

THE CASE

A 34-year-old Eritrean man presented to the emergency department with complaints of diffuse abdominal pain and distention. He had emigrated to the United States 3 months earlier, following 5 years in a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Two weeks earlier, the patient sought care at his primary care clinic and was diagnosed with post-operative urinary retention and constipation following a recent hemorrhoidectomy. A Foley catheter was inserted and provided a short period of relief.

Following the visit, however, his abdominal pain worsened. He also experienced increasing abdominal distention, a declining appetite, and persistent nausea. The patient said that he was unable to urinate and had not had a bowel movement in 6 days. He also described fevers, drenching night sweats, chills, and a 4-kg weight loss over 2 months.

On physical examination, the patient had a wasted appearance. He was afebrile, alert, and oriented, but anxious and writhing in pain. An abdominal examination revealed some distention, generalized guarding, and tenderness. There was dullness to percussion in all regions without rebound, and no caput medusa was noted. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Pertinent laboratory values included negative screens for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and 2, and a purified protein derivative test that produced 10 mm of induration at 48 hours. An interferon-gamma release assay was not performed following these results. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast revealed thickening of the peritoneal lining with infiltration of the mesenteric fat and large loculated fluid collections in the abdominal cavity (FIGURE). A CT scan of the patient’s lungs showed some mild atelectasis with left-sided effusion.

After hospital admission, the patient spiked fevers as high as 103.3° F and developed progressively worsening ascites. An ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed, during which almost 2 liters of yellow, hazy fluid was removed. Fluid and blood cultures were negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

With a high clinical suspicion for tuberculosis (TB) peritonitis, we requested a surgical consultation and a peritoneal biopsy was performed. The patient was started on ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, pyridoxine, and rifampin while the biopsy results were pending.

Pathology subsequently confirmed a diagnosis of TB peritonitis, reporting dense fibroconnective tissue with areas of chronic inflammation and occasional accumulations of histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells showing granulomatous inflammation. An acid-fast (AF) bacilli stain for Mycobacteria showed a single curved bacillus compatible with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The patient was discharged following a 3-week hospital stay. At his follow-up visit several weeks later, the patient reported marked improvement and increasing exercise tolerance. He had gained weight, and the abdominal distention and tenderness had resolved.

DISCUSSION

Worldwide, TB is one of the top 10 causes of death. The World Health Organization estimates that there were 1.4 million TB deaths globally in 2015.1 And while rates of TB are decreasing in the United States, there was a resurgence from 1985 to 1992.2 This was attributable to the HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome epidemic, increased immigration from countries endemic for TB, and deterioration of the TB public health infrastructure.3

Transmission. M tuberculosis is a rod-shaped, nonspore-forming AF bacillus that typically infects the lungs, but may infect other areas of the body. Transmission typically occurs via airborne spread of droplets from an infected individual. Possible other methods of disease dissemination include ingestion of infected sputum, hematogenous spread from active pulmonary TB, or ingestion of contaminated milk or food.

M tuberculosis elicits a proinflammatory phase, which facilitates the formation of a granuloma within the host tissues. The host’s immune response to M tuberculosis plays a role in the risk of developing this type of TB.3

TB presentation is classified as pulmonary, extrapulmonary, or both. Clinicians are generally attentive to the classic symptoms of pulmonary TB: cough, weight loss, night sweats, and fever. Presentation of extrapulmonary TB, however, may vary.4

According to one study, the most common presenting symptoms for peritoneal TB are weight loss, abdominal pain, and/or fever, all of which our patient experienced.5 In addition, our patient was an immigrant from Africa, and black patients have been shown to have a significantly higher incidence of extrapulmonary TB than their nonblack counterparts.6 Although our patient was HIV-negative, a recent meta-analysis confirmed the strong association between extrapulmonary TB and HIV, emphasizing the importance of including HIV screens in the standard work-up for TB.7

Other symptoms may include microcytosis, anemia, thrombocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although a chest x-ray is often negative, advanced imaging, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging, is often abnormal and may point to the diagnosis.5

Treatment of extrapulmonary TB is generally the same as that for pulmonary TB and, interestingly, the incidence of multi-drug resistant extrapulmonary TB is not necessarily higher than it is for pulmonary TB (<1% vs 1.6%).3,7 In light of this, a standard regimen—like the one our patient received—is generally utilized for 6 to 9 months. Nonetheless, resistance testing should still be performed.3,4

THE TAKEAWAY

While considered uncommon, more than 20% of TB cases in the United States are extrapulmonary (the most common form is TB lymphadenitis).7,8 It is imperative to identify appropriate risk factors, including associated comorbidities, patient characteristics, and population/endemic differences in immigrant populations.

In this case, although the symptom combination of persistent abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss may not trigger suspicion of a TB diagnosis in isolation, combining the symptoms with knowledge of the patient’s immigration status should at least raise an eyebrow. Given their nonpulmonary symptoms, many of these patients will not present to pulmonologists, making diagnosis particularly relevant to primary care.

THE CASE

A 34-year-old Eritrean man presented to the emergency department with complaints of diffuse abdominal pain and distention. He had emigrated to the United States 3 months earlier, following 5 years in a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Two weeks earlier, the patient sought care at his primary care clinic and was diagnosed with post-operative urinary retention and constipation following a recent hemorrhoidectomy. A Foley catheter was inserted and provided a short period of relief.

Following the visit, however, his abdominal pain worsened. He also experienced increasing abdominal distention, a declining appetite, and persistent nausea. The patient said that he was unable to urinate and had not had a bowel movement in 6 days. He also described fevers, drenching night sweats, chills, and a 4-kg weight loss over 2 months.

On physical examination, the patient had a wasted appearance. He was afebrile, alert, and oriented, but anxious and writhing in pain. An abdominal examination revealed some distention, generalized guarding, and tenderness. There was dullness to percussion in all regions without rebound, and no caput medusa was noted. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Pertinent laboratory values included negative screens for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and 2, and a purified protein derivative test that produced 10 mm of induration at 48 hours. An interferon-gamma release assay was not performed following these results. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast revealed thickening of the peritoneal lining with infiltration of the mesenteric fat and large loculated fluid collections in the abdominal cavity (FIGURE). A CT scan of the patient’s lungs showed some mild atelectasis with left-sided effusion.

After hospital admission, the patient spiked fevers as high as 103.3° F and developed progressively worsening ascites. An ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed, during which almost 2 liters of yellow, hazy fluid was removed. Fluid and blood cultures were negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

With a high clinical suspicion for tuberculosis (TB) peritonitis, we requested a surgical consultation and a peritoneal biopsy was performed. The patient was started on ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, pyridoxine, and rifampin while the biopsy results were pending.

Pathology subsequently confirmed a diagnosis of TB peritonitis, reporting dense fibroconnective tissue with areas of chronic inflammation and occasional accumulations of histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells showing granulomatous inflammation. An acid-fast (AF) bacilli stain for Mycobacteria showed a single curved bacillus compatible with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The patient was discharged following a 3-week hospital stay. At his follow-up visit several weeks later, the patient reported marked improvement and increasing exercise tolerance. He had gained weight, and the abdominal distention and tenderness had resolved.

DISCUSSION

Worldwide, TB is one of the top 10 causes of death. The World Health Organization estimates that there were 1.4 million TB deaths globally in 2015.1 And while rates of TB are decreasing in the United States, there was a resurgence from 1985 to 1992.2 This was attributable to the HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome epidemic, increased immigration from countries endemic for TB, and deterioration of the TB public health infrastructure.3

Transmission. M tuberculosis is a rod-shaped, nonspore-forming AF bacillus that typically infects the lungs, but may infect other areas of the body. Transmission typically occurs via airborne spread of droplets from an infected individual. Possible other methods of disease dissemination include ingestion of infected sputum, hematogenous spread from active pulmonary TB, or ingestion of contaminated milk or food.

M tuberculosis elicits a proinflammatory phase, which facilitates the formation of a granuloma within the host tissues. The host’s immune response to M tuberculosis plays a role in the risk of developing this type of TB.3

TB presentation is classified as pulmonary, extrapulmonary, or both. Clinicians are generally attentive to the classic symptoms of pulmonary TB: cough, weight loss, night sweats, and fever. Presentation of extrapulmonary TB, however, may vary.4

According to one study, the most common presenting symptoms for peritoneal TB are weight loss, abdominal pain, and/or fever, all of which our patient experienced.5 In addition, our patient was an immigrant from Africa, and black patients have been shown to have a significantly higher incidence of extrapulmonary TB than their nonblack counterparts.6 Although our patient was HIV-negative, a recent meta-analysis confirmed the strong association between extrapulmonary TB and HIV, emphasizing the importance of including HIV screens in the standard work-up for TB.7

Other symptoms may include microcytosis, anemia, thrombocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although a chest x-ray is often negative, advanced imaging, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging, is often abnormal and may point to the diagnosis.5

Treatment of extrapulmonary TB is generally the same as that for pulmonary TB and, interestingly, the incidence of multi-drug resistant extrapulmonary TB is not necessarily higher than it is for pulmonary TB (<1% vs 1.6%).3,7 In light of this, a standard regimen—like the one our patient received—is generally utilized for 6 to 9 months. Nonetheless, resistance testing should still be performed.3,4

THE TAKEAWAY

While considered uncommon, more than 20% of TB cases in the United States are extrapulmonary (the most common form is TB lymphadenitis).7,8 It is imperative to identify appropriate risk factors, including associated comorbidities, patient characteristics, and population/endemic differences in immigrant populations.

In this case, although the symptom combination of persistent abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss may not trigger suspicion of a TB diagnosis in isolation, combining the symptoms with knowledge of the patient’s immigration status should at least raise an eyebrow. Given their nonpulmonary symptoms, many of these patients will not present to pulmonologists, making diagnosis particularly relevant to primary care.

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2016_executive_summary.pdf?ua=1. Accessed August 22, 2017.

2. Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1350-1357.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2006. Available at: http://digitallibrary.utah.gov/awweb/awarchive?type=file&item=56908. Accessed August 3, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19908en/s19908en.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2017.

5. Ramesh J, Banait GS, Ormerod LP. Abdominal tuberculosis in a district general hospital: a retrospective review of 86 cases. QJM. 2008;101:189-195.

6. Fiske CT, Griffin MR, Erin H, et al. Black race, sex and extrapulmonary tuberculosis risk: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:16.

7. Naing C, Mak JW, Maung M, et al. Meta-analysis: the association between HIV infection and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Lung. 2013;191:27-34.

8. Neelakantan S, Nair PP, Emmanuel RV, et al. Diversities in presentations of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013.

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2016_executive_summary.pdf?ua=1. Accessed August 22, 2017.

2. Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1350-1357.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2006. Available at: http://digitallibrary.utah.gov/awweb/awarchive?type=file&item=56908. Accessed August 3, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19908en/s19908en.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2017.

5. Ramesh J, Banait GS, Ormerod LP. Abdominal tuberculosis in a district general hospital: a retrospective review of 86 cases. QJM. 2008;101:189-195.

6. Fiske CT, Griffin MR, Erin H, et al. Black race, sex and extrapulmonary tuberculosis risk: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:16.

7. Naing C, Mak JW, Maung M, et al. Meta-analysis: the association between HIV infection and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Lung. 2013;191:27-34.

8. Neelakantan S, Nair PP, Emmanuel RV, et al. Diversities in presentations of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013.

Postpartum Treatment of Metastatic Recurrent Giant Cell Tumor of Capitate Bone of Wrist

Take-Home Points

- GCT of bones of the wrist is rare. This article is the only report of a wrist GCT during pregnancy that we could identify.

- Routine treatment usually consists of surgical excision with local adjuvant, and in the wrist, often results in reduced wrist motion.

- GCT of the wrist is more aggressive than the more common locations in long bones, with higher local recurrence rates if treated with surgery alone.

- Diagnosis is often delayed for GCT of the wrist, due to insufficient imaging, which should include CT or MRI.

- For pregnant women with GCT, local adjuvant treatments can be used in addition to surgery. Following pregnancy, denosumab can be used systemically, and can be effective with metastatic or unresectable disease.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone accounts for about 5% of primary bone tumors.1-3 Only 3% to 5% of GCTs occur in the hand.4,5 Wrist involvement, which is rare, most often involves the hamate bone.5-7 Capitate bone involvement is exceedingly rare.8-11 Although histologically benign, GCT can recur locally after treatment with curettage alone, and lung metastases are found in 2% to 5% of cases.2,12-14 Therefore, en bloc tumor excision is preferred in the setting of cortical erosion or soft-tissue involvement.1,4,8 Wrist joint motion is inevitably reduced, and bone graft donor-site morbidity is significant.6-8

In the unusual case reported here, GCT presented in the capitate bone and, after the patient became pregnant, recurred in the hamate and trapezoid bones with soft-tissue extension and lung metastases. The capitate was excised en bloc and reconstructed with an interposition of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. Pulmonary metastases developed, and the GCT expanded to involve multiple carpal bones and the bases of the second through fourth metacarpals. A 10-month course of systemic chemotherapy with the RANK ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab was started after the pregnancy. After this treatment, the patient underwent both tumor resection and reconstruction with autogenous bicortical iliac crest bone graft (ICBG) carefully designed to preserve range of motion and maintain the fingers in anatomical position. Treatment with denosumab was continued after surgery. Although this case offers no endpoint for postoperative chemotherapy with denosumab, preoperative treatment dramatically reduced the GCT and permitted limb-sparing reconstruction. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 19-year-old right-handed woman with atraumatic swelling of the left wrist presented to an orthopedic surgeon at an outside facility. Physical examination revealed tender fullness on the dorsum of the wrist, slightly reduced range of motion and grip strength, and a neurovascularly intact wrist. The diagnosis was periarticular cyst, and the patient underwent physical therapy. Two years later, the swelling returned, tenderness was increasing, and symptoms did not resolve with cast immobilization. A radiograph showed a lytic lesion in the capitate bone (Figure 1).[[{"fid":"202332","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_left","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-left","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_left","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 1.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_left","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 1.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

GCT was diagnosed with percutaneous needle biopsy. A preoperative chest radiograph was reported normal. For initial treatment, the capitate and trapezoid bones were resected en bloc through a dorsal approach. Reconstruction consisted of limited arthrodesis using bone cement without additional fixation.

At 6-month follow-up, the patient was pregnant, and there was a recurrence of the wrist lesion. During the first 2 months of pregnancy, swelling and pain rapidly progressed, and a palpable mass formed. Radiographs showed a lytic lesion extending into the hamate bone (Figure 2), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed articular extension of the lesion with involvement of the base of the fourth metacarpal. [[{"fid":"202334","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"2"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 2.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 2.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]Targeted anti-RANKL therapy was not recommended (and was not available at the patient’s home hospital). The patient deferred surgical treatment because of the pregnancy, which proved otherwise uneventful and ended with a full-term delivery.

After the pregnancy, radiographs of the wrist showed complete destruction of the hamate and trapezium bones, with erosion of the bases of the second through fourth metacarpals (Figure 3A). [[{"fid":"202335","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_left","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-left","data-delta":"3"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_left","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 3.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_left","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 3.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]The patient presented at our institution 4 years after initial diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed numerous bilateral pulmonary nodular opacities. Wrist imaging showed soft-tissue extension (Figure 3B). The diagnosis of recurrent metastatic GCT was confirmed with needle biopsies of the wrist mass and the right lung nodule.

Systemic chemotherapy was initiated with 120 mg of denosumab, given subcutaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 and then monthly during the 10 months leading up to surgery. Serum calcium was monitored during treatment and remained within the normal range the entire time, except for once at the start of therapy, when it dropped to 6.8 mg/dL. After 8 months, the soft-tissue mass, originally 8 cm × 8 cm × 6 cm, shrunk and stabilized at 5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm (Figure 3B), and a bony shell reformed around it. Nodules in both lung fields showed response to denosumab.

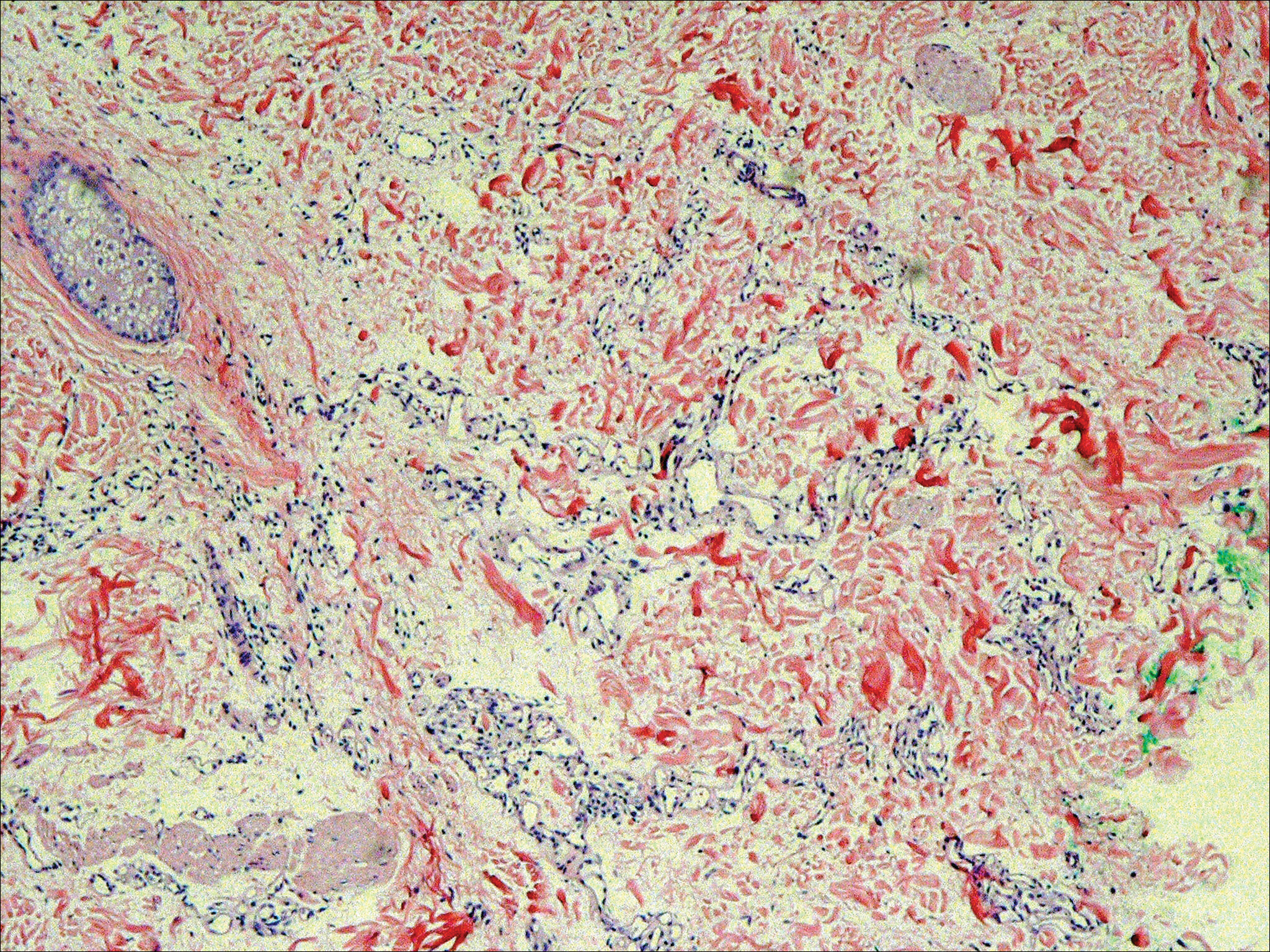

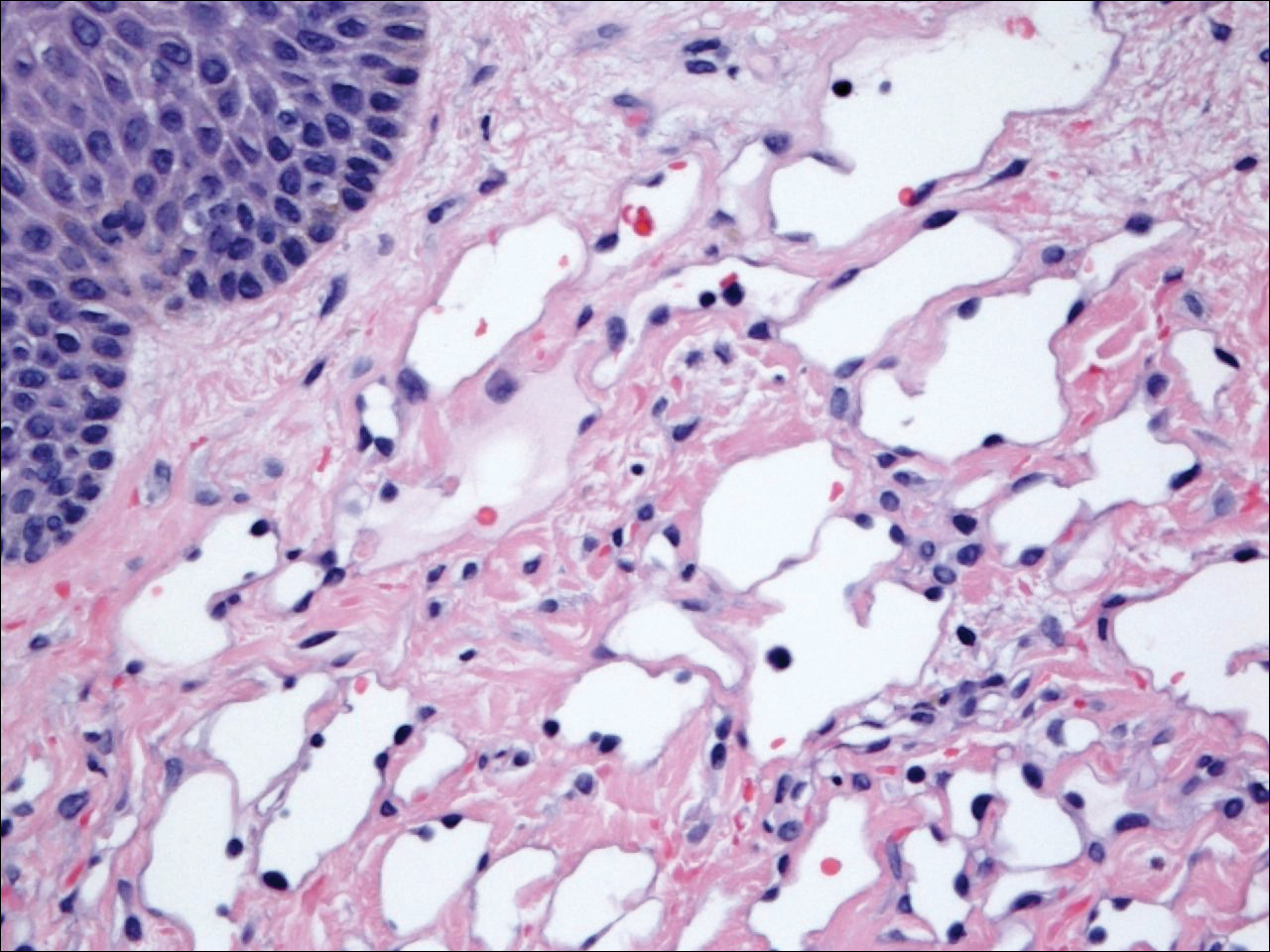

Histologic examination revealed scattered osteoclast-like, multinucleated giant cells, consistent with a recurrent lesion (Figure 4). [[{"fid":"202336","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"4"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 4.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"4":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 4.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]After 10 months of treatment with denosumab, the patient underwent resection (dorsal approach) of the residual cement, the soft-tissue mass, the affected carpal bones, half of the third metacarpal, and the second and fourth metacarpal bases. The proximal carpal row was preserved after no intra-articular involvement was verified. The closet margin was marginal; the tumor mass abutted without encompassing the flexor tendons and median nerve. The tumor was meticulously elevated from the neurovascular and tendinous structures, which were not sacrificed. Hydrogen peroxide was used for local adjuvant treatment. Bicortical autogenous ICBG was placed between the remaining scaphoid, lunate, and metacarpal bones. The second, third, and fourth metacarpal bases were stabilized on the overlapping outer table of ICBG with 2.0-mm plates and miniscrews (Figure 5A). Kirschner wires were used to stabilize the proximal bone graft and the scapholunate fossa. Cancellous bone graft was packed between the structural bone graft and neighboring unaffected carpal bones (Figure 5A). Immobilization with a short-arm thumb spica cast was maintained for 6 weeks after surgery and was followed by a 12-week rehabilitation program. The patient returned to normal activities when plain radiographs showed solid bony union (Figure 5B). Fourteen months after initial surgery, tenolysis was performed to free the extensor tendons (index, middle, and ring fingers on dorsum of left hand) from adhesions to the bone graft. At 37-month follow-up (Figure 5C), there was no clinical or radiographic evidence of progression in the wrist.[[{"fid":"202337","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_left","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-left","data-delta":"5"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_left","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 5.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"5":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_left","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 5.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

The patient had bilateral pulmonary metastases (Figures 6A, 6B). Treatment with denosumab produced an initial response (smaller pulmonary lesions) and subsequent stability. After 12 months of treatment with denosumab, the patient underwent left thoracotomy and wedge resection of pulmonary metastases on the left. Pathologic evaluation revealed pulmonary parenchyma with calcification and ossification and limited viable tumor. Given the dramatic effects on the left pulmonary metastases, denosumab was continued, and surgical intervention on the right was not attempted. Pulmonary metastases were stable afterward (Figure 6C).[[{"fid":"202338","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"6"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 6.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"6":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Figure 6.","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

At 54-month follow-up, systemic treatment with denosumab was continued. The patient had no pain in the wrist or hand and was able to use the left hand normally. There was some fissuring of the third and fourth digits over each other. However, the patient had good grip strength and was using eating utensils, picking up water bottles, and engaging in other activities without difficulty.

Discussion

GCT isolated to the carpus is rare. However, compared with GCT in the more common locations in long bones, it is also more aggressive, and its local recurrence rates are higher, probably 60% or more if treated with curettage alone.15 Therefore, excision augmented with adjuvant treatment is recommended.2,7 Use of bone cement in the hand is relatively uncommon.4,5,7-10

The diagnosis of GCT in the carpus is difficult and often delayed. The initial complaint is usually mild wrist pain after relatively mild trauma.5 The first reported case of GCT in the lunate bone was mistakenly thought to be Kienbock disease.5 Similarly, our patient was initially given a nononcologic diagnosis, which prompted conservative management.

Whether the biological behavior of GCT in the carpus differs from that of GCT in other sites is unclear. The high recurrence rates might be attributable in part to suboptimal curettage.5,6 En bloc resections of involved bone inevitably result in carpal instability or loss of wrist motion if arthrodesis is performed.4-7,11 In the present case, resection was followed by limited arthrodesis to mitigate motion losses.

Multifocal GCT in the carpal bones often affects younger patients and has a high rate of recurrence.7,16 In the present case, the patient’s pregnancy delayed treatment and allowed tumor extension into soft tissues and metacarpal bones. Given her young age, en bloc tumor resection was performed, with the proximal carpal row spared to preserve wrist motion. ICBG was carefully shaped to match the defect that remained after tumor resection.7 Supporting wrist height to prevent carpal collapse provided a stable base for remaining distal segments of the second through fourth metacarpals. After short-arm thumb spica casting and early rehabilitation, the patient recovered wrist motion and use of the involved fingers distal to the carpometacarpal joints.