User login

Eruptive Melanocytic Nevi During Azathioprine Therapy for Antisynthetase Syndrome

Case Report

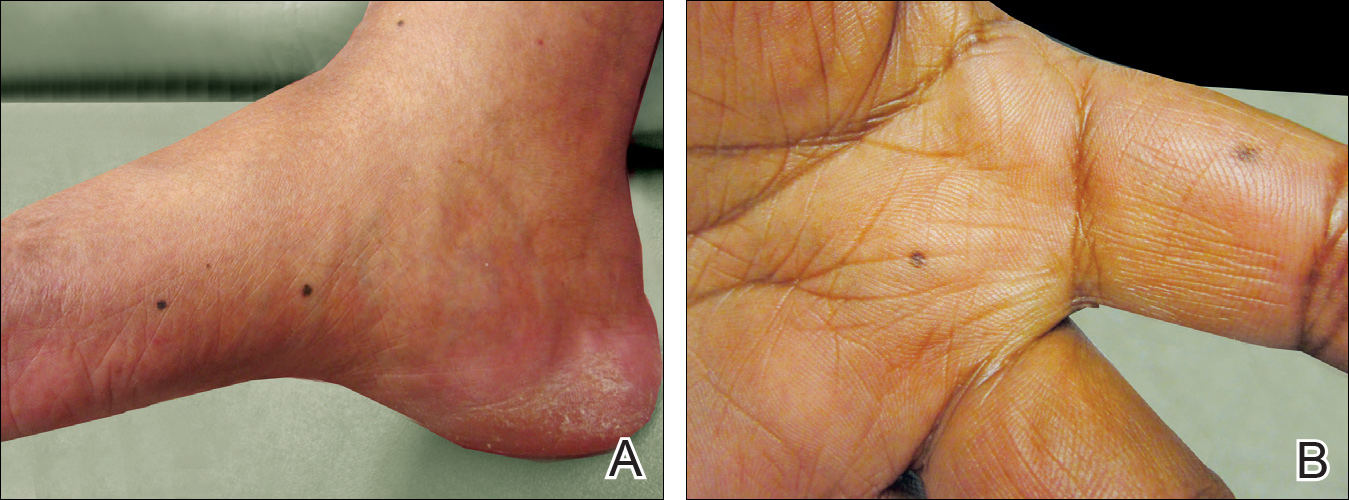

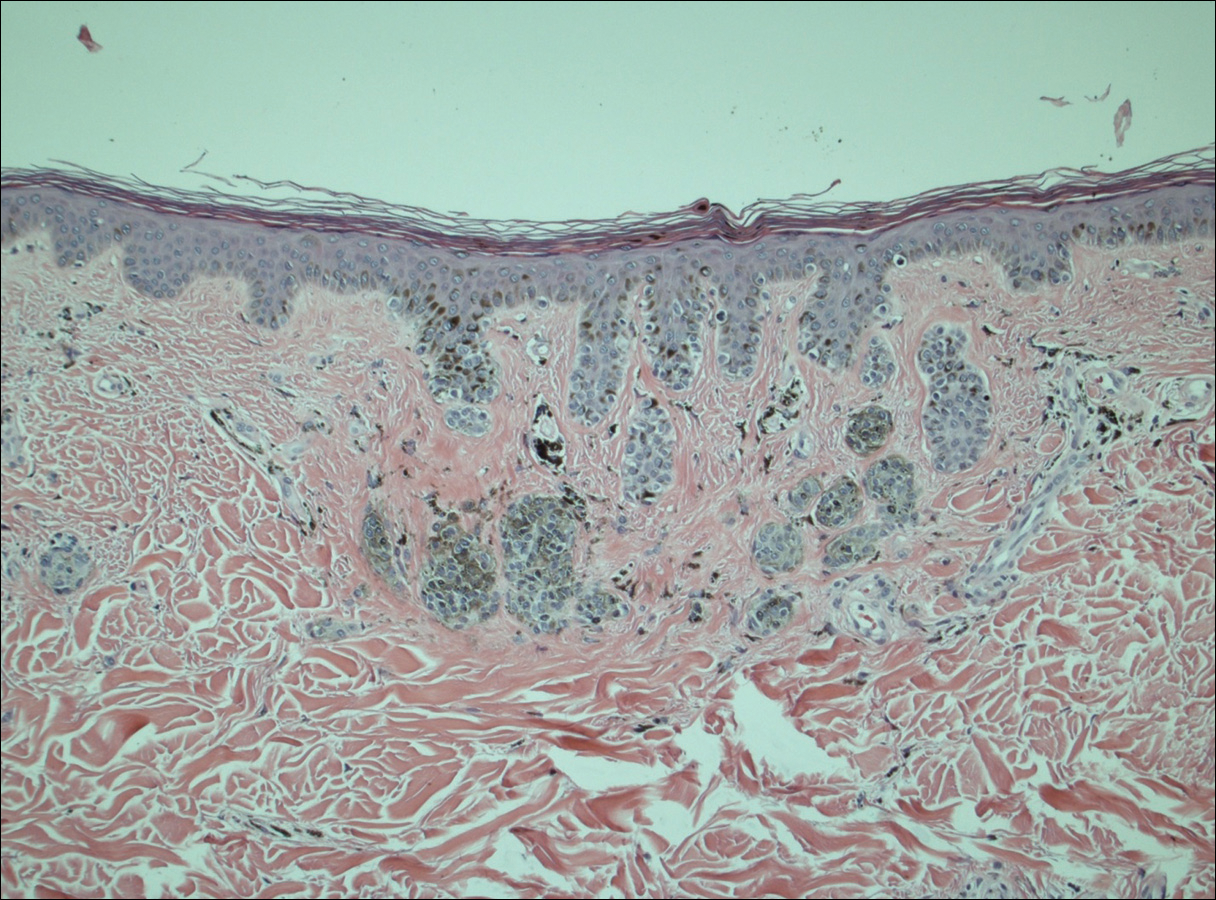

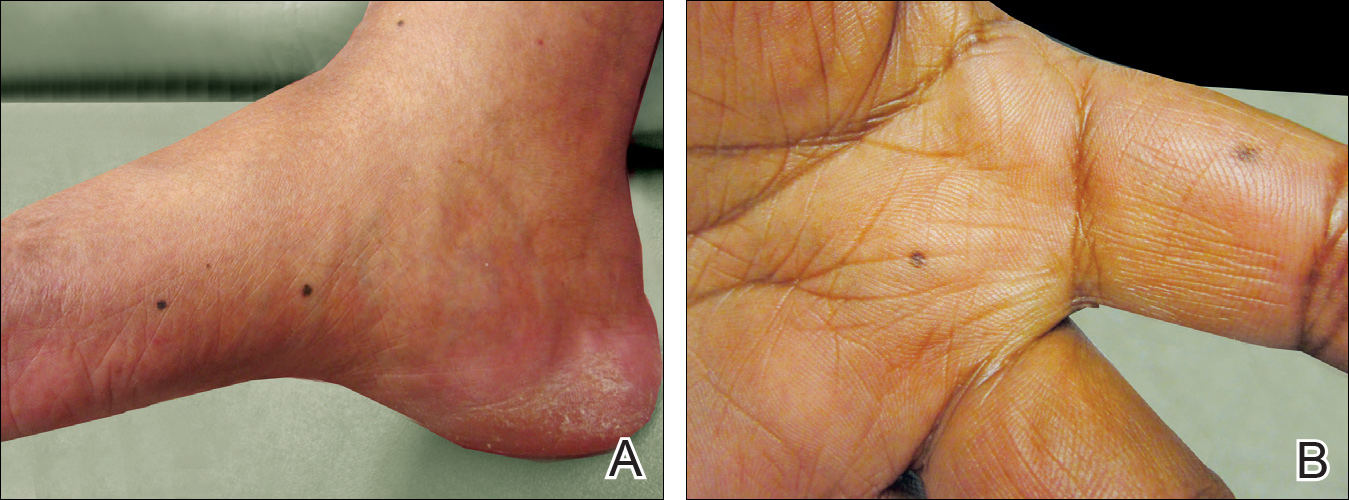

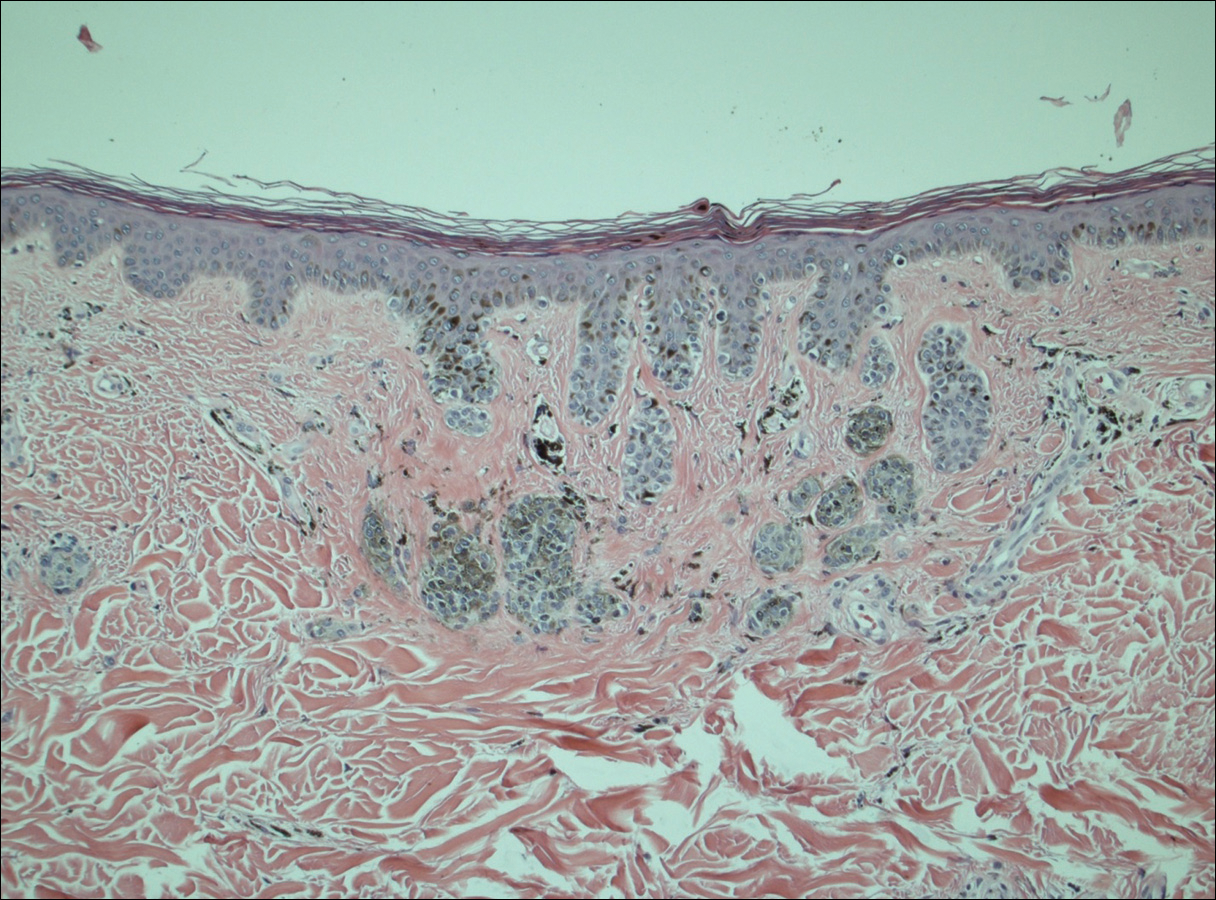

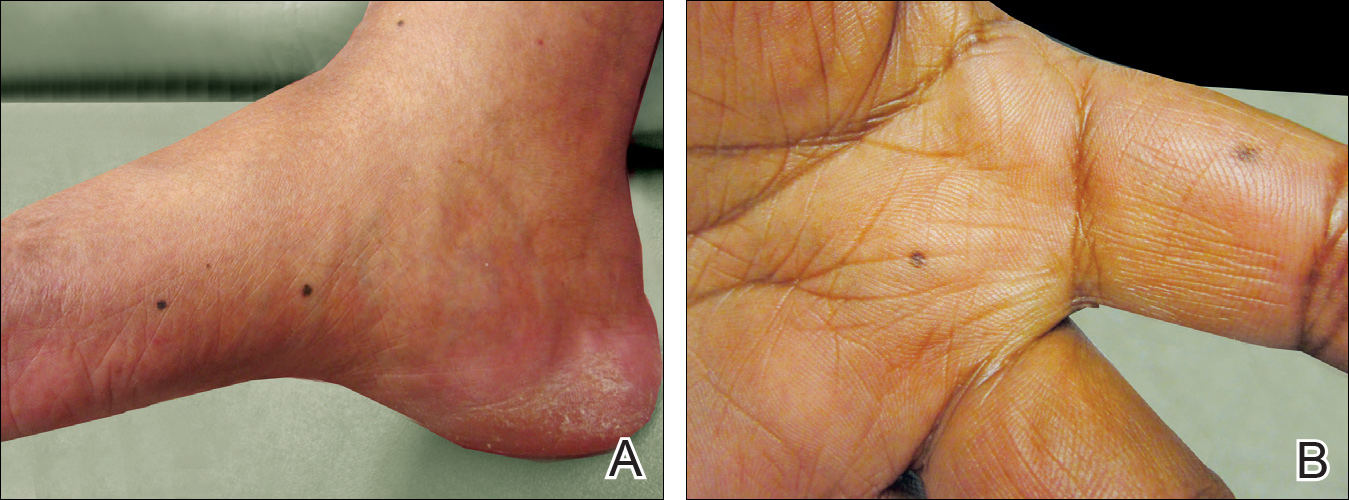

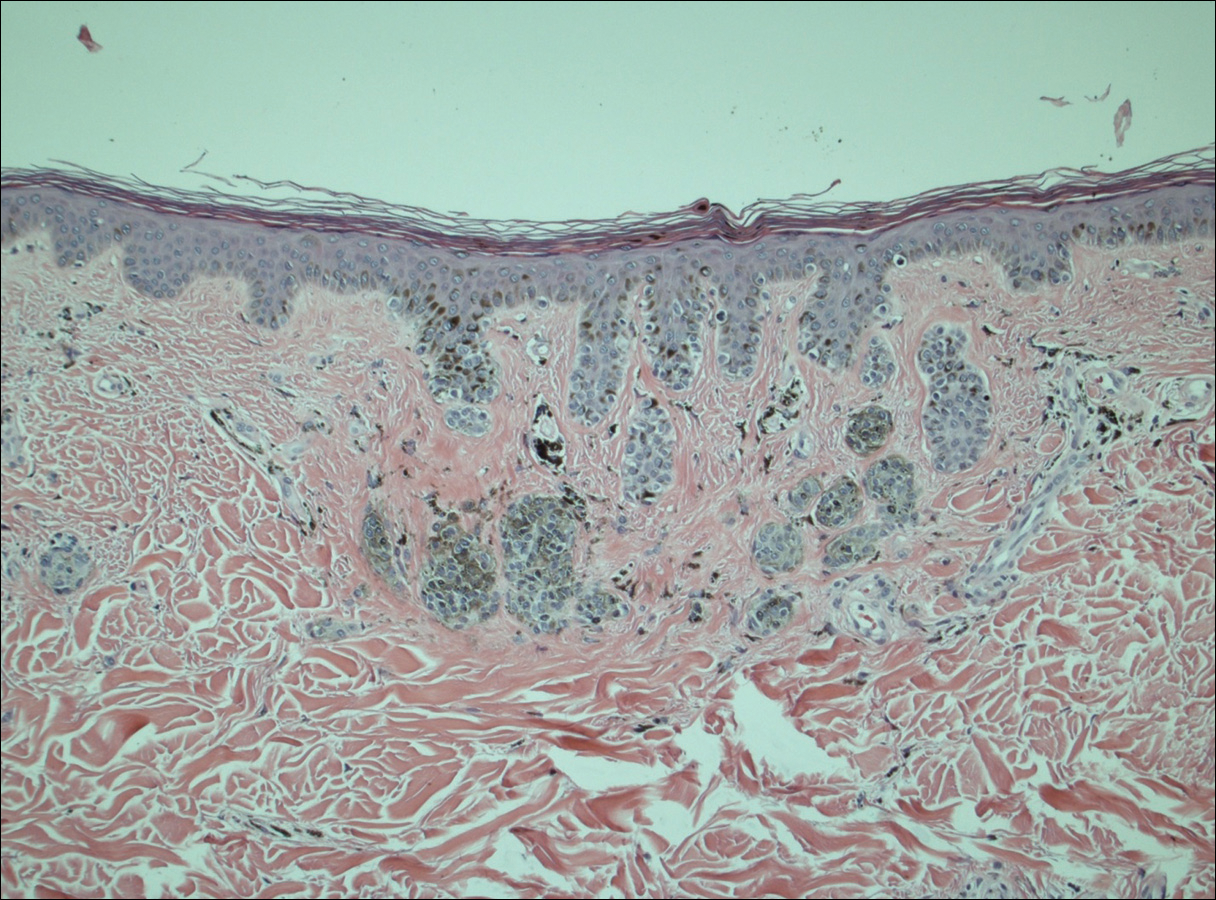

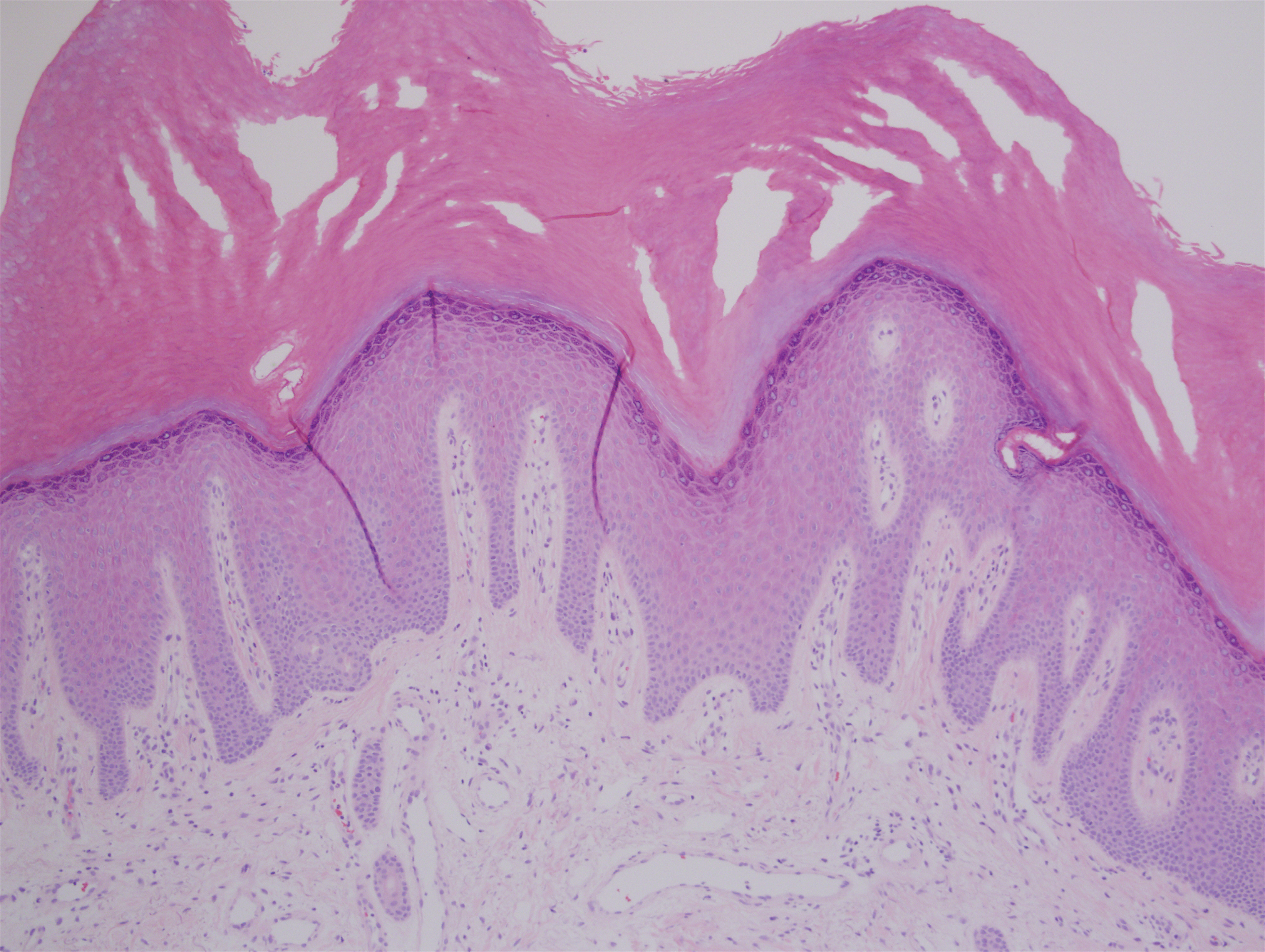

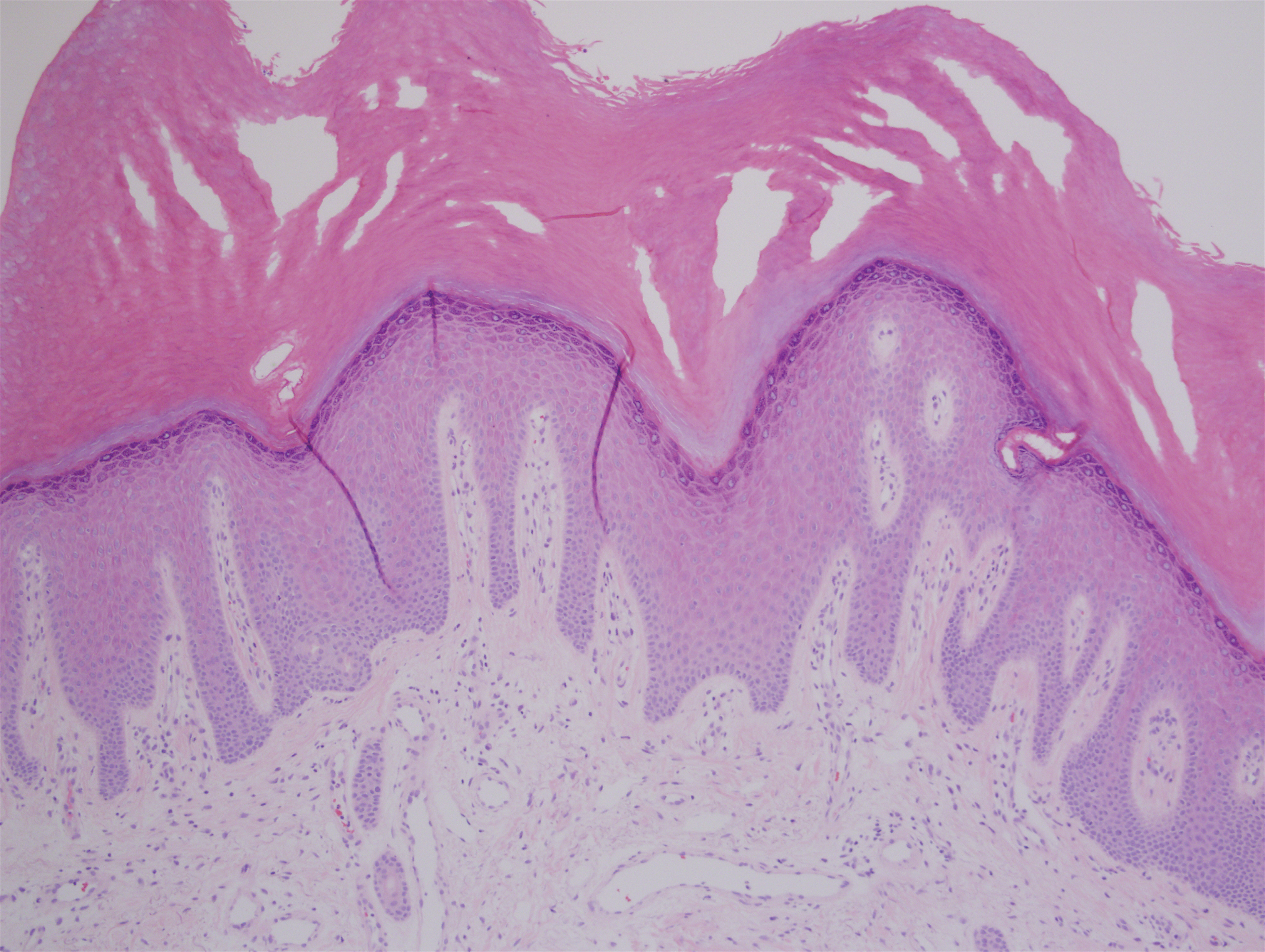

A 50-year-old man with a history of antisynthetase syndrome (positive for anti–Jo-1 polymyositis with interstitial lung disease) and sarcoidosis presented for evaluation of numerous new moles. The lesions had developed on the trunk, arms, legs, hands, and feet approximately 3 weeks after starting azathioprine 100 mg once daily for pulmonary and muscular involvement of antisynthetase syndrome. He denied any preceding cutaneous inflammation or sunburns. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer, and no family members had multiple nevi. Physical examination revealed 30 to 40 benign-appearing, 2- to 5-mm, hyperpigmented macules scattered on the medial aspect of the right foot (Figure 1A), left palm (Figure 1B), back, abdomen, chest, arms, and legs. A larger, somewhat asymmetric, irregularly bordered, and irregularly pigmented macule was noted on the left side of the upper back. A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed a benign, mildly atypical lentiginous compound nevus (Figure 2). Pathology confirmed that the lesions represented eruptive melanocytic nevi (EMN). The patient continued azathioprine therapy and was followed with regular full-body skin examinations. Mycophenolate mofetil was suggested as an alternative therapy, if clinically appropriate, though this change has not been made by the patient’s rheumatologists.

Comment

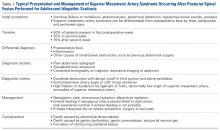

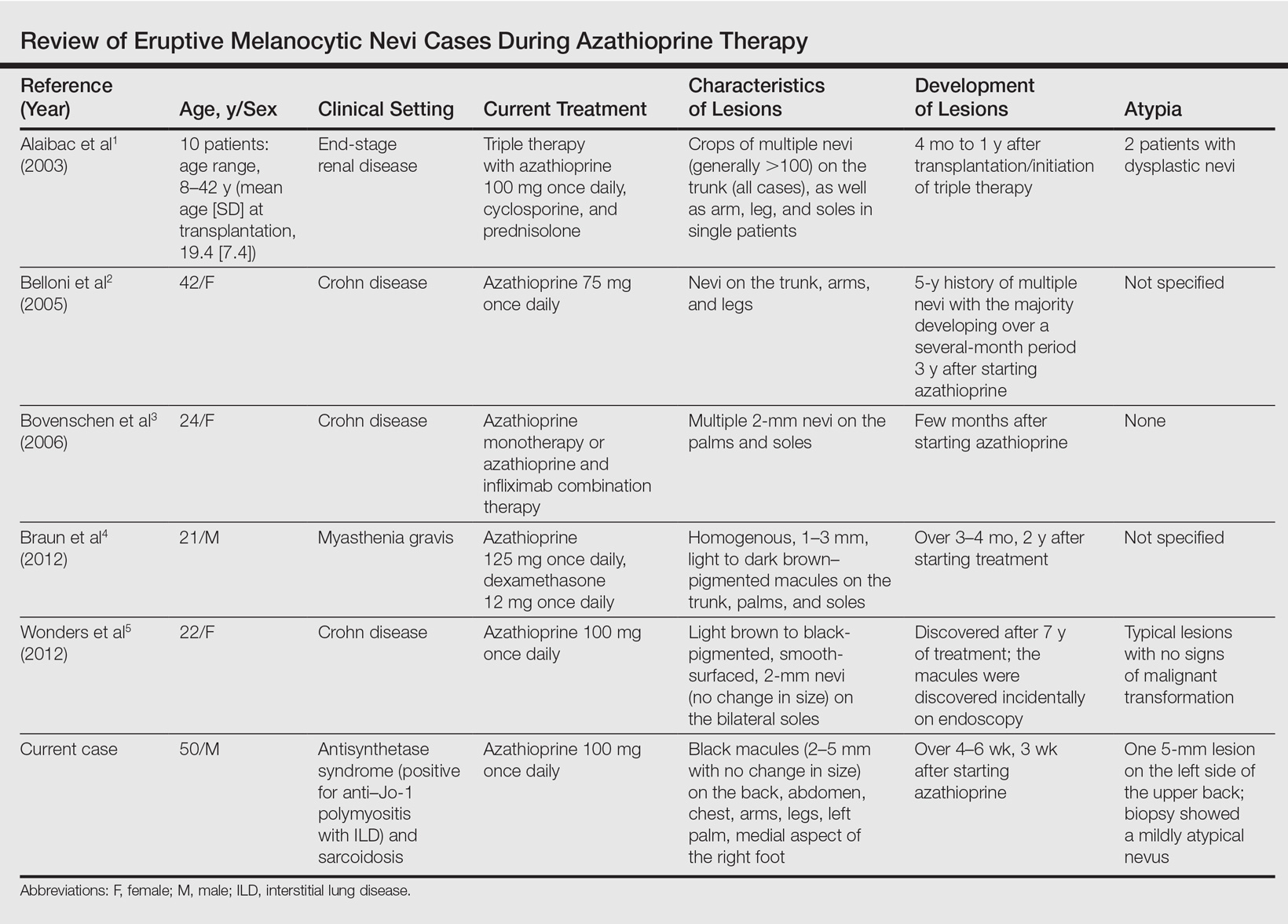

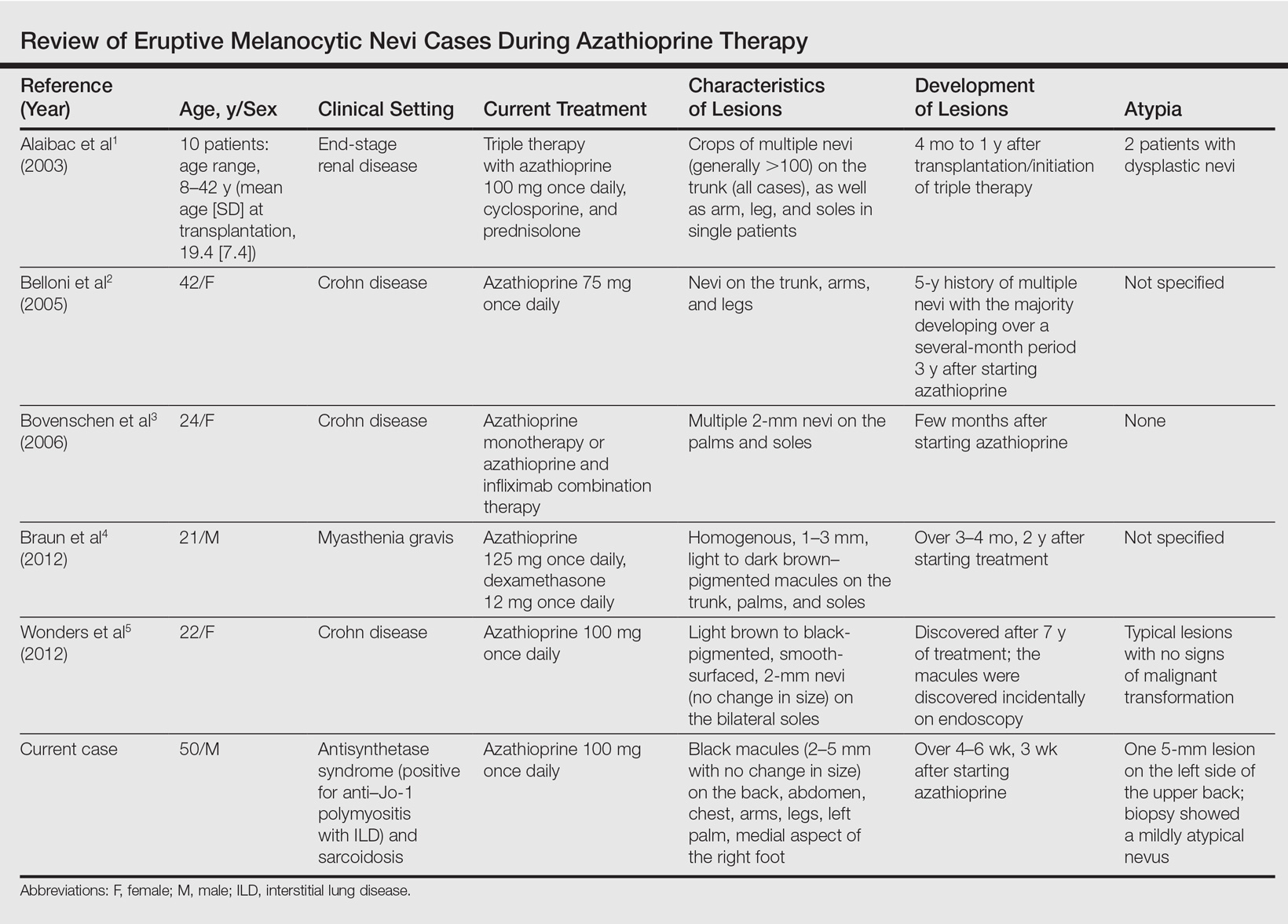

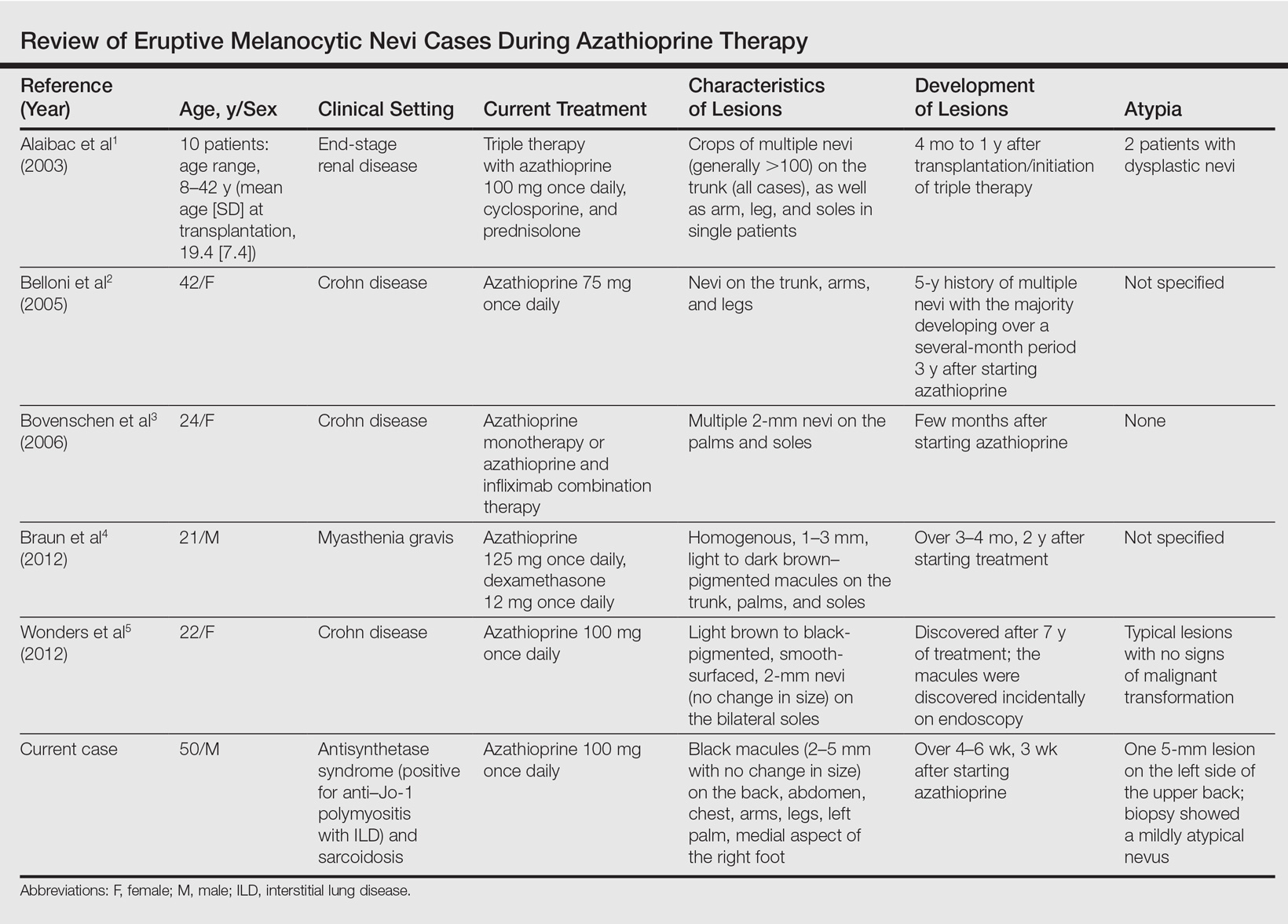

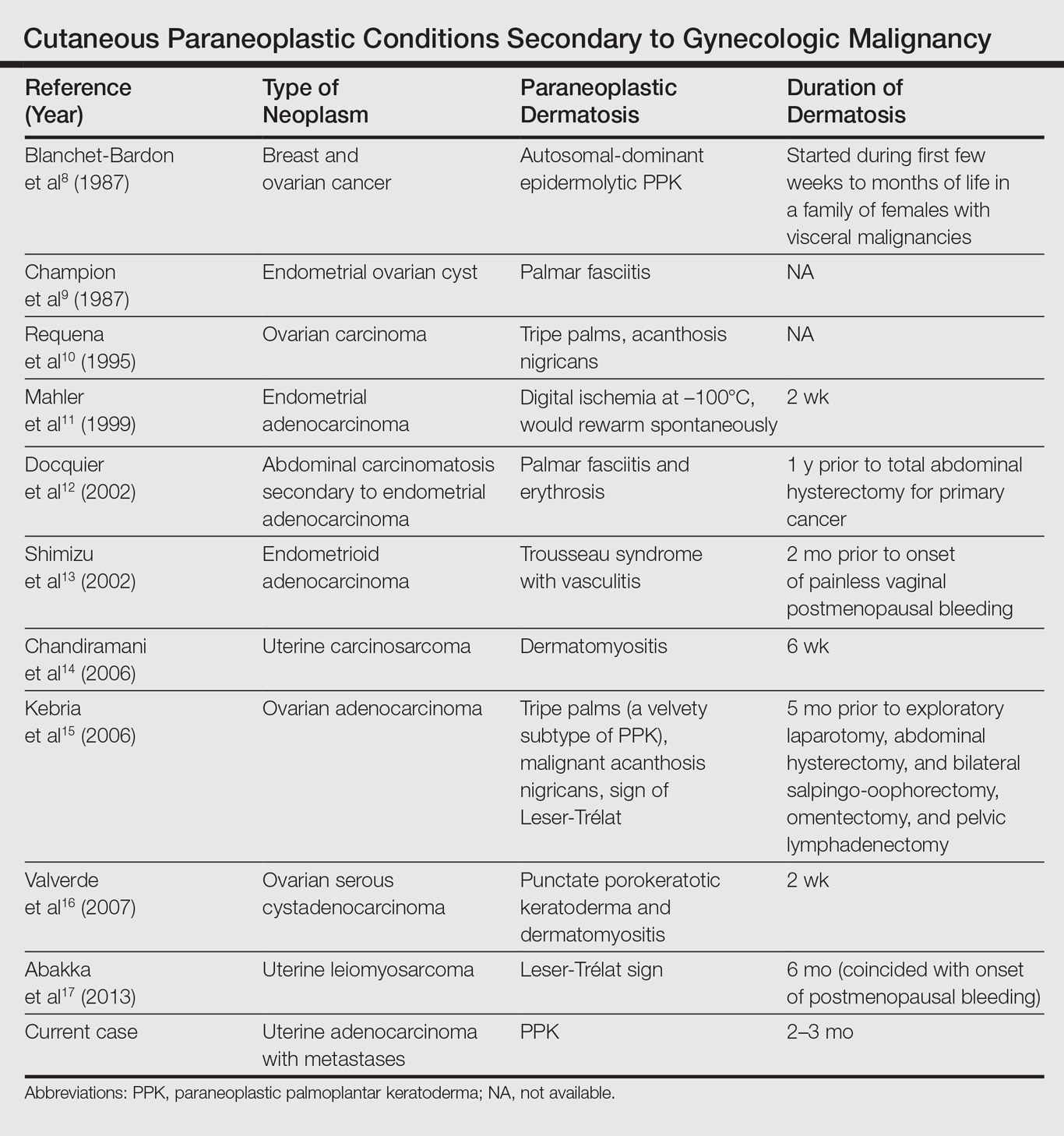

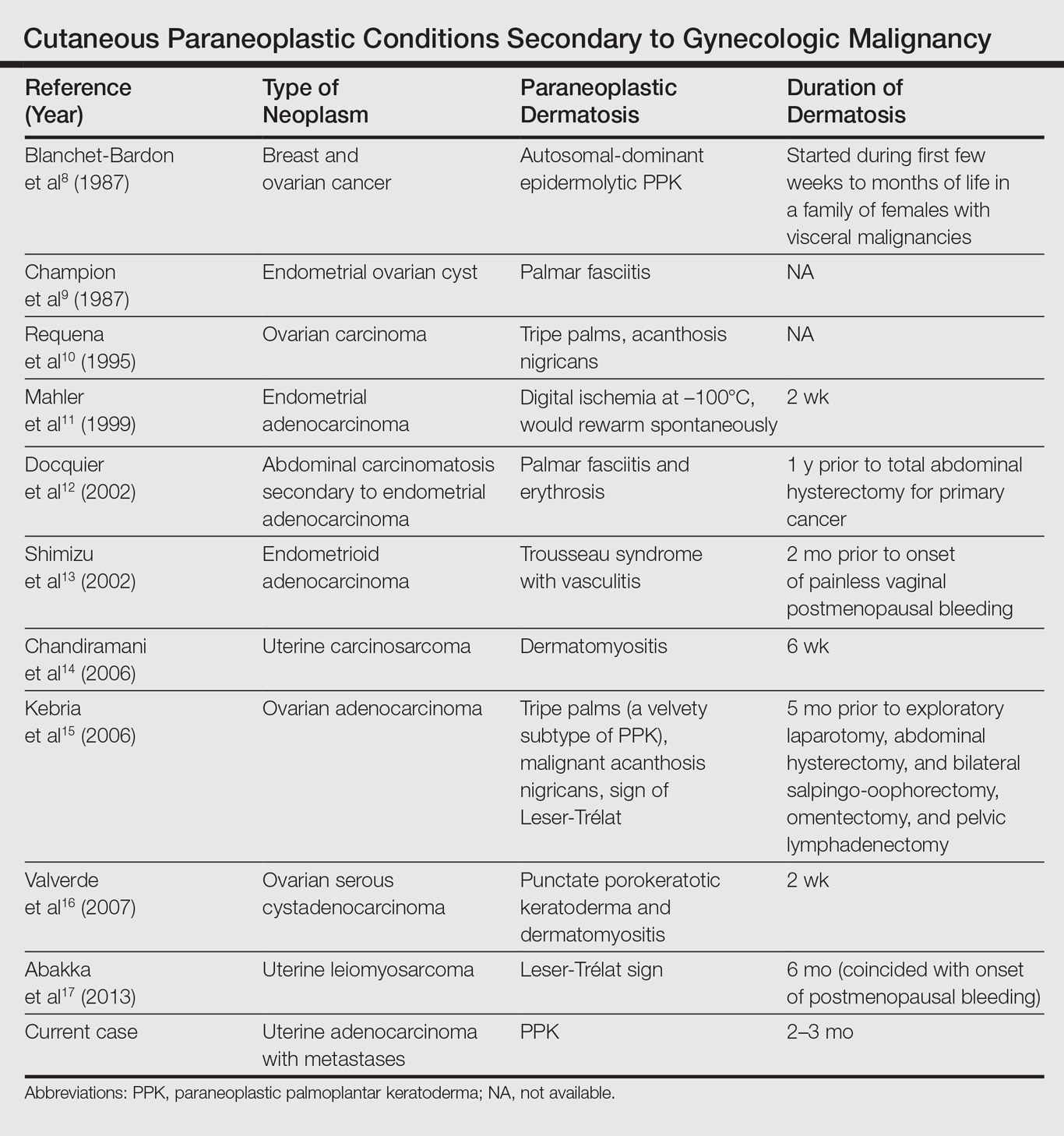

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms eruptive melanocytic nevi and azathioprine revealed 14 cases of EMN in the setting of azathioprine therapy, either during azathioprine monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressants, including systemic corticosteroids, biologics, and cyclosporine (Table).1-5 The majority of these cases occurred in renal transplant patients,1 with 3 additional cases reported in the setting of Crohn disease,2,3,5 and another in a patient with myasthenia gravis.4 Patients ranged in age from 8 to 42 years (mean age, 22 years), with lesions developing a few months to up to 7 years after starting therapy. When specified, the reported lesions typically were small, ranging from 1 to 3 mm in size, and developed rapidly over a couple of months with a predilection for the palms, soles, and trunk. Although dysplastic nevi were described in only 2 patients, melanomas were not detected.

Various hypotheses have sought to explain the largely unknown etiology of EMN. Bovenschen et al3 suggested that immunocompromised patients have diminished immune surveillance in the skin, which allows for unchecked proliferation of melanocytes. Specifically, immune suppression may induce melanocyte-stimulating hormone or melanoma growth stimulatory activity, with composition-specific growth in skin at the palms and soles.3,4 The preferential growth on the palms and soles suggests that those regions may have special sensitivity to melanocyte-stimulating hormone.4 Woodhouse and Maytin6 postulated that the increased density of eccrine sweat glands in the palms and soles as well as the absence of pilosebaceous units and apocrine glands and plentiful Pacinian and Meissner corpuscles may allow for a unique response to circulating melanocytic growth factors. Another hypothesis suggests the presence of genetic factors that allow subclinical nests of nevus cells to form, which become clinical eruptions following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.3 Azathioprine also has been suggested to induce various transcription factors that play a critical role in differentiation and proliferation of melanocytic stem cells, which leads to the formation of nevi.4 Our case and others similar to it implore that further studies be done to determine the molecular mechanism driving this phenomenon and whether a specific genetic predisposition exists that lowers the threshold for rapid proliferation of melanocytes given an immunosuppressed status.2

The risk for melanoma development in cases of EMN is unknown. Although our review of the literature did not reveal any melanomas reported in cases attributed to azathioprine, a theoretical risk exists given the established associations between melanoma and immunosuppression as well as increased numbers of nevi.6 Accordingly, these patients should be followed with regular skin examinations and biopsies of atypical-appearing lesions as indicated.2,3,5 Braun et al4 also suggested the discontinuance of azathioprine and switch to mycophenolic acid, which has not been noted to cause such eruptions; this drug was recommended in our case.

- Alaibac M, Piaserico S, Rossi CR, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi in patients with renal allografts: report of 10 cases with dermoscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1020-1022.

- Belloni FA, Piaserico S, Zattra E, et al. Dermoscopic features of eruptive melanocytic naevi in an adult patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy for Crohn’s disease. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:223-224.

- Bovenschen HJ, Tjioe M, Vermaat H, et al. Induction of eruptive benign melanocytic naevi by immune suppressive agents, including biologicals. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:880-884.

- Braun SA, Helbig D, Frank J, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi during azathioprine therapy in myasthenia gravis [in German]. Hautarzt. 2012;63:756-759.

- Wonders J, De Boer N, Van Weyenberg S. Spot diagnosis: eruptive melanocytic naevi during azathioprine therapy in Crohn’s disease [published online March 6, 2012]. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:636.

- Woodhouse J, Maytin EV. Eruptive nevi of the palms and soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S96-S100.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man with a history of antisynthetase syndrome (positive for anti–Jo-1 polymyositis with interstitial lung disease) and sarcoidosis presented for evaluation of numerous new moles. The lesions had developed on the trunk, arms, legs, hands, and feet approximately 3 weeks after starting azathioprine 100 mg once daily for pulmonary and muscular involvement of antisynthetase syndrome. He denied any preceding cutaneous inflammation or sunburns. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer, and no family members had multiple nevi. Physical examination revealed 30 to 40 benign-appearing, 2- to 5-mm, hyperpigmented macules scattered on the medial aspect of the right foot (Figure 1A), left palm (Figure 1B), back, abdomen, chest, arms, and legs. A larger, somewhat asymmetric, irregularly bordered, and irregularly pigmented macule was noted on the left side of the upper back. A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed a benign, mildly atypical lentiginous compound nevus (Figure 2). Pathology confirmed that the lesions represented eruptive melanocytic nevi (EMN). The patient continued azathioprine therapy and was followed with regular full-body skin examinations. Mycophenolate mofetil was suggested as an alternative therapy, if clinically appropriate, though this change has not been made by the patient’s rheumatologists.

Comment

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms eruptive melanocytic nevi and azathioprine revealed 14 cases of EMN in the setting of azathioprine therapy, either during azathioprine monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressants, including systemic corticosteroids, biologics, and cyclosporine (Table).1-5 The majority of these cases occurred in renal transplant patients,1 with 3 additional cases reported in the setting of Crohn disease,2,3,5 and another in a patient with myasthenia gravis.4 Patients ranged in age from 8 to 42 years (mean age, 22 years), with lesions developing a few months to up to 7 years after starting therapy. When specified, the reported lesions typically were small, ranging from 1 to 3 mm in size, and developed rapidly over a couple of months with a predilection for the palms, soles, and trunk. Although dysplastic nevi were described in only 2 patients, melanomas were not detected.

Various hypotheses have sought to explain the largely unknown etiology of EMN. Bovenschen et al3 suggested that immunocompromised patients have diminished immune surveillance in the skin, which allows for unchecked proliferation of melanocytes. Specifically, immune suppression may induce melanocyte-stimulating hormone or melanoma growth stimulatory activity, with composition-specific growth in skin at the palms and soles.3,4 The preferential growth on the palms and soles suggests that those regions may have special sensitivity to melanocyte-stimulating hormone.4 Woodhouse and Maytin6 postulated that the increased density of eccrine sweat glands in the palms and soles as well as the absence of pilosebaceous units and apocrine glands and plentiful Pacinian and Meissner corpuscles may allow for a unique response to circulating melanocytic growth factors. Another hypothesis suggests the presence of genetic factors that allow subclinical nests of nevus cells to form, which become clinical eruptions following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.3 Azathioprine also has been suggested to induce various transcription factors that play a critical role in differentiation and proliferation of melanocytic stem cells, which leads to the formation of nevi.4 Our case and others similar to it implore that further studies be done to determine the molecular mechanism driving this phenomenon and whether a specific genetic predisposition exists that lowers the threshold for rapid proliferation of melanocytes given an immunosuppressed status.2

The risk for melanoma development in cases of EMN is unknown. Although our review of the literature did not reveal any melanomas reported in cases attributed to azathioprine, a theoretical risk exists given the established associations between melanoma and immunosuppression as well as increased numbers of nevi.6 Accordingly, these patients should be followed with regular skin examinations and biopsies of atypical-appearing lesions as indicated.2,3,5 Braun et al4 also suggested the discontinuance of azathioprine and switch to mycophenolic acid, which has not been noted to cause such eruptions; this drug was recommended in our case.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man with a history of antisynthetase syndrome (positive for anti–Jo-1 polymyositis with interstitial lung disease) and sarcoidosis presented for evaluation of numerous new moles. The lesions had developed on the trunk, arms, legs, hands, and feet approximately 3 weeks after starting azathioprine 100 mg once daily for pulmonary and muscular involvement of antisynthetase syndrome. He denied any preceding cutaneous inflammation or sunburns. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer, and no family members had multiple nevi. Physical examination revealed 30 to 40 benign-appearing, 2- to 5-mm, hyperpigmented macules scattered on the medial aspect of the right foot (Figure 1A), left palm (Figure 1B), back, abdomen, chest, arms, and legs. A larger, somewhat asymmetric, irregularly bordered, and irregularly pigmented macule was noted on the left side of the upper back. A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed a benign, mildly atypical lentiginous compound nevus (Figure 2). Pathology confirmed that the lesions represented eruptive melanocytic nevi (EMN). The patient continued azathioprine therapy and was followed with regular full-body skin examinations. Mycophenolate mofetil was suggested as an alternative therapy, if clinically appropriate, though this change has not been made by the patient’s rheumatologists.

Comment

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms eruptive melanocytic nevi and azathioprine revealed 14 cases of EMN in the setting of azathioprine therapy, either during azathioprine monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressants, including systemic corticosteroids, biologics, and cyclosporine (Table).1-5 The majority of these cases occurred in renal transplant patients,1 with 3 additional cases reported in the setting of Crohn disease,2,3,5 and another in a patient with myasthenia gravis.4 Patients ranged in age from 8 to 42 years (mean age, 22 years), with lesions developing a few months to up to 7 years after starting therapy. When specified, the reported lesions typically were small, ranging from 1 to 3 mm in size, and developed rapidly over a couple of months with a predilection for the palms, soles, and trunk. Although dysplastic nevi were described in only 2 patients, melanomas were not detected.

Various hypotheses have sought to explain the largely unknown etiology of EMN. Bovenschen et al3 suggested that immunocompromised patients have diminished immune surveillance in the skin, which allows for unchecked proliferation of melanocytes. Specifically, immune suppression may induce melanocyte-stimulating hormone or melanoma growth stimulatory activity, with composition-specific growth in skin at the palms and soles.3,4 The preferential growth on the palms and soles suggests that those regions may have special sensitivity to melanocyte-stimulating hormone.4 Woodhouse and Maytin6 postulated that the increased density of eccrine sweat glands in the palms and soles as well as the absence of pilosebaceous units and apocrine glands and plentiful Pacinian and Meissner corpuscles may allow for a unique response to circulating melanocytic growth factors. Another hypothesis suggests the presence of genetic factors that allow subclinical nests of nevus cells to form, which become clinical eruptions following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.3 Azathioprine also has been suggested to induce various transcription factors that play a critical role in differentiation and proliferation of melanocytic stem cells, which leads to the formation of nevi.4 Our case and others similar to it implore that further studies be done to determine the molecular mechanism driving this phenomenon and whether a specific genetic predisposition exists that lowers the threshold for rapid proliferation of melanocytes given an immunosuppressed status.2

The risk for melanoma development in cases of EMN is unknown. Although our review of the literature did not reveal any melanomas reported in cases attributed to azathioprine, a theoretical risk exists given the established associations between melanoma and immunosuppression as well as increased numbers of nevi.6 Accordingly, these patients should be followed with regular skin examinations and biopsies of atypical-appearing lesions as indicated.2,3,5 Braun et al4 also suggested the discontinuance of azathioprine and switch to mycophenolic acid, which has not been noted to cause such eruptions; this drug was recommended in our case.

- Alaibac M, Piaserico S, Rossi CR, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi in patients with renal allografts: report of 10 cases with dermoscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1020-1022.

- Belloni FA, Piaserico S, Zattra E, et al. Dermoscopic features of eruptive melanocytic naevi in an adult patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy for Crohn’s disease. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:223-224.

- Bovenschen HJ, Tjioe M, Vermaat H, et al. Induction of eruptive benign melanocytic naevi by immune suppressive agents, including biologicals. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:880-884.

- Braun SA, Helbig D, Frank J, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi during azathioprine therapy in myasthenia gravis [in German]. Hautarzt. 2012;63:756-759.

- Wonders J, De Boer N, Van Weyenberg S. Spot diagnosis: eruptive melanocytic naevi during azathioprine therapy in Crohn’s disease [published online March 6, 2012]. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:636.

- Woodhouse J, Maytin EV. Eruptive nevi of the palms and soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S96-S100.

- Alaibac M, Piaserico S, Rossi CR, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi in patients with renal allografts: report of 10 cases with dermoscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1020-1022.

- Belloni FA, Piaserico S, Zattra E, et al. Dermoscopic features of eruptive melanocytic naevi in an adult patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy for Crohn’s disease. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:223-224.

- Bovenschen HJ, Tjioe M, Vermaat H, et al. Induction of eruptive benign melanocytic naevi by immune suppressive agents, including biologicals. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:880-884.

- Braun SA, Helbig D, Frank J, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi during azathioprine therapy in myasthenia gravis [in German]. Hautarzt. 2012;63:756-759.

- Wonders J, De Boer N, Van Weyenberg S. Spot diagnosis: eruptive melanocytic naevi during azathioprine therapy in Crohn’s disease [published online March 6, 2012]. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:636.

- Woodhouse J, Maytin EV. Eruptive nevi of the palms and soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S96-S100.

Practice Points

- A theoretical risk exists in the setting of eruptive melanocytic nevi (EMN) given the established associations between melanoma and immunosuppression as well as increased numbers of nevi.

- Follow patients with EMN with regular skin examinations and biopsies of atypical-appearing lesions given the increased risk for melanoma in this population.

Muscle spasms, twitches in arm upon throwing • Dx?

THE CASE

A 31-year-old right-handed college baseball coach presented to his family physician (FP) with concerns about the “yips” in his right arm. His ability to throw a baseball had been gradually deteriorating. Involuntary upper right arm muscle contractions and spasms, which began intermittently when he was a teenager, were now a real problem for him as an adult. (See the video below.) The patient was having difficulty rolling a baseball underhand to players as part of infield practice and he was experiencing muscle spasms when lifting his right arm over his head. “Twitches” in the patient’s upper arm were making drinking difficult, but he had no problems feeding himself, writing, or performing other basic activities of daily living.

The patient experienced the same symptoms whether it was baseball season or not. He hadn’t noticed a change in symptoms with caffeine and denied use of any other stimulants in the last 4 years. His symptoms didn’t improve or worsen with greater or lesser quantity or quality of sleep or when he concentrated on stifling the involuntary movements. He had attempted to learn to throw left-handed to overcome the impairment, but was concerned that the same problem would occur in his left arm.

The patient had previously worked with a sports psychologist and hypnotherapist to overcome any potential subconscious performance anxiety, but this hadn’t helped. Stretching and strengthening with a physical therapist and numerous sessions with an acupuncturist hadn’t helped either. Despite this, he believed the problem to be primarily psychological.

The patient’s history included mild attention deficit disorder and exercise-induced asthma; his family history was negative for any movement or psychiatric disorders. He had 2 dislocation repairs on his left, non-throwing shoulder in his early twenties. His medications included fluticasone-salmeterol twice daily and albuterol, as needed.

The patient denied myalgia or arthralgia, decreased passive range of motion, shoulder or arm weakness, swelling, or muscle atrophy. He also didn’t have paresthesias in his right arm or hand, a resting tremor, difficulty moving (other than drinking from a cup), difficulty moving other extremities, dizziness, imbalance, or seizures.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. He had full range of motion and 5 out of 5 strength without pain during right shoulder abduction, external and internal rotation, an empty can test, a lower back lift off (Gerber’s) test, and a test of bicep and tricep strength, along with negative Neer and Hawkins tests.

There was no evidence of muscle wasting or asymmetry in the bilateral upper extremities. The patient’s deep tendon reflex grade was 2+ out of 4 in both of his arms. He didn’t have a sensory deficit to light touch in areas of C5 to T1 and he had normal cranial nerves II to XII. He had normal rapid alternating movements, heel-to-shin testing, and finger-to-nose testing, as well as a normal gait and Romberg test.

The patient provided a video showing the abnormal involuntary flexion of his shoulder when attempting to throw a baseball.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s FP was aware of the “yips,” a condition that is commonly viewed as psychological or related to performance anxiety. (The “yips” are colloquially known as “Steve Blass Disease”—named after a Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher who suddenly lost the ability to control his pitches.1) But based on the patient’s clinical presentation and history of seeing a number of mental health care providers—in addition to his worsening symptoms—the FP ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. The MRI turned out to be unremarkable, so the patient was referred to Neurology.

In the general neurology clinic, a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease (a condition that leads to excess copper deposition in multiple organ systems, including the nervous system) was considered, as it can cause symptoms similar to those our patient was experiencing. However, a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, ceruloplasmin test, and copper level were all normal, effectively ruling it out. An MRI of the cervical spine showed mild to moderate right foraminal stenosis at C3-4 and C5-6, but this did not explain the patient’s symptoms.

A diagnosis of paroxysmal exercise-induced dystonia was also considered at the time of the initial work-up, as our patient’s symptoms were most pronounced during physical activity. But this condition usually responds to antiepileptics, and carbamazepine and phenytoin were each tried for multiple months early in his evaluation without benefit.

3 factors led to a diagnosis of focal limb dystonia: Only our patient’s right arm was affected, his laboratory and imaging work-ups were negative, and he didn’t respond to antiepileptic treatment. Characterization of a movement disorder is based upon phenomenology. In this case, the patient had sustained abnormal posturing at the shoulder during right upper limb activation, which was only triggered with specific voluntary actions. This was consistent with dystonia, a movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal movements and/or postures—often initiated or worsened by voluntary action.2

DISCUSSION

The “yips,” or intermittent, transient tremors, jerks, or spasms3 that are seen in athletes, are well-documented in the lay press, but haven’t been significantly addressed in the medical literature.4 Stigma surrounding the condition among athletes likely leads to under-reporting. Athletes typically experience yips with fine motor movements, such as short putts in golf and pitching in baseball. In fact, while the majority of the medical literature on yips revolves around golfers, many talented baseball players have had their careers altered by the condition. The yips may also affect movements in sports like darts, cricket, table tennis, and billiards.

In 1984, dystonia was defined as a disorder of sensorimotor integration that results in co-contraction of agonist/antagonist muscles, and may be characterized by state dependence (exacerbation with specific activities) or sensory tricks (amelioration with specific types of sensory input).5 In 2013, the definition was revised to remove “co-contraction” from the definition because phenomenology alone is sufficient to make the diagnosis.1

Many athletes and sports fans believe the yips are caused by performance anxiety or related phobias, but evidence suggests that many athletes with the movement disorder may actually have focal limb dystonia.6,7 The yips can, however, lead to performance anxiety,3 but there has been no difference noted between the anxiety level of golfers with or without the yips.7 Psychological treatment approaches are commonly employed, but surface electromyograms have shown abnormal co-contraction of wrist flexor and extensor muscles in 5 out of 10 golfers with the yips (but 0 of those without) while putting—which is consistent with focal limb dystonia.8

Botulinum toxin injections are Tx of choice, but can cause weakness

Muscle relaxers, such as baclofen and benzodiazepines, as well as dopamine antagonists, can ameliorate dystonia.9 Focal limb dystonia may also respond to the antispasmodic trihexyphenidyl, but the dose must often be limited due to adverse effects such as nausea, dizziness, and anxiety.10

Botulinum toxin injections have proven effective for focal limb dystonia11 and are considered the treatment of choice. However, there are few reports on their use in athletes, where the adverse effect of weakness could affect performance. One case report also showed improvement of yips with acupuncture, although this has not been extensively studied.12

Our patient didn’t respond to low-dose (2 mg twice a day) trihexyphenidyl. Tetrabenazine, a dopamine depletor frequently used for hyperkinetic disorders, was not effective at 25 mg taken prior to coaching sessions. Higher doses of an anticholinergic could have been effective, but the patient declined our recommendation to pursue this (or botulinum toxin injections). He decided instead to train himself to use his left arm while coaching.

THE TAKEAWAY

Athletes who play sports that require precision movements commonly develop the yips. While the prevailing theory among athletes is that this is a psychological phenomenon, evidence shows that this may in fact be a neurologic focal dystonia caused by repetitive use. Greater awareness of yips as a possible organic, treatable neurologic condition is needed in order to stimulate more research on this topic.

1. Baseball’s head cases often prove baffling. USA Today Baseball Weekly. 2001. Available at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/bbw/2001-02-07/2001-02-07-head.htm. Accessed March 15, 2017.

2. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28:863-873.

3. Dhungana S, Jankovic J. Yips and other movement disorders in golfers. Mov Disord. 2013;28:576-581.

4. Stacy MA, ed. Handbook of dystonia. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc; 2007.

5. Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB. Classification and investigation of dystonia. In: Marsden CD, Fahn S, eds. Movement disorders 2. London: Butterworths; 1987:332-358.

6. Smith AM, Adler CH, Crews D, et al. The ‘yips’ in golf: a continuum between a focal dystonia and choking. Sports Med. 2003;33:13-31.

7. Sachdev P. Golfers’ cramp: clinical characteristics and evidence against it being an anxiety disorder. Mov Disord. 1992;7:326-332.

8. Adler CH, Crews D, Hentz JG, et al. Abnormal co-contraction in yips-affected but not unaffected golfers: evidence for focal dystonia. Neurology. 2005;64:1813-1814.

9. Jankovic J. Treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:844-856.

10. Jankovic J. Treatment of dystonia. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:864-872.

11. Lungu C, Karp BI, Alter K, et al. Long-term follow-up of botulinum toxin therapy for focal hand dystonia: outcome at 10 years or more. Mov Disord. 2011;26:750-753.

12. Rosted P. Acupuncture for treatment of the yips?—a case report. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:188-189.

THE CASE

A 31-year-old right-handed college baseball coach presented to his family physician (FP) with concerns about the “yips” in his right arm. His ability to throw a baseball had been gradually deteriorating. Involuntary upper right arm muscle contractions and spasms, which began intermittently when he was a teenager, were now a real problem for him as an adult. (See the video below.) The patient was having difficulty rolling a baseball underhand to players as part of infield practice and he was experiencing muscle spasms when lifting his right arm over his head. “Twitches” in the patient’s upper arm were making drinking difficult, but he had no problems feeding himself, writing, or performing other basic activities of daily living.

The patient experienced the same symptoms whether it was baseball season or not. He hadn’t noticed a change in symptoms with caffeine and denied use of any other stimulants in the last 4 years. His symptoms didn’t improve or worsen with greater or lesser quantity or quality of sleep or when he concentrated on stifling the involuntary movements. He had attempted to learn to throw left-handed to overcome the impairment, but was concerned that the same problem would occur in his left arm.

The patient had previously worked with a sports psychologist and hypnotherapist to overcome any potential subconscious performance anxiety, but this hadn’t helped. Stretching and strengthening with a physical therapist and numerous sessions with an acupuncturist hadn’t helped either. Despite this, he believed the problem to be primarily psychological.

The patient’s history included mild attention deficit disorder and exercise-induced asthma; his family history was negative for any movement or psychiatric disorders. He had 2 dislocation repairs on his left, non-throwing shoulder in his early twenties. His medications included fluticasone-salmeterol twice daily and albuterol, as needed.

The patient denied myalgia or arthralgia, decreased passive range of motion, shoulder or arm weakness, swelling, or muscle atrophy. He also didn’t have paresthesias in his right arm or hand, a resting tremor, difficulty moving (other than drinking from a cup), difficulty moving other extremities, dizziness, imbalance, or seizures.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. He had full range of motion and 5 out of 5 strength without pain during right shoulder abduction, external and internal rotation, an empty can test, a lower back lift off (Gerber’s) test, and a test of bicep and tricep strength, along with negative Neer and Hawkins tests.

There was no evidence of muscle wasting or asymmetry in the bilateral upper extremities. The patient’s deep tendon reflex grade was 2+ out of 4 in both of his arms. He didn’t have a sensory deficit to light touch in areas of C5 to T1 and he had normal cranial nerves II to XII. He had normal rapid alternating movements, heel-to-shin testing, and finger-to-nose testing, as well as a normal gait and Romberg test.

The patient provided a video showing the abnormal involuntary flexion of his shoulder when attempting to throw a baseball.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s FP was aware of the “yips,” a condition that is commonly viewed as psychological or related to performance anxiety. (The “yips” are colloquially known as “Steve Blass Disease”—named after a Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher who suddenly lost the ability to control his pitches.1) But based on the patient’s clinical presentation and history of seeing a number of mental health care providers—in addition to his worsening symptoms—the FP ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. The MRI turned out to be unremarkable, so the patient was referred to Neurology.

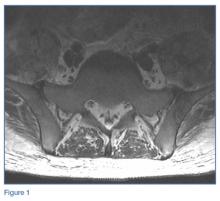

In the general neurology clinic, a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease (a condition that leads to excess copper deposition in multiple organ systems, including the nervous system) was considered, as it can cause symptoms similar to those our patient was experiencing. However, a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, ceruloplasmin test, and copper level were all normal, effectively ruling it out. An MRI of the cervical spine showed mild to moderate right foraminal stenosis at C3-4 and C5-6, but this did not explain the patient’s symptoms.

A diagnosis of paroxysmal exercise-induced dystonia was also considered at the time of the initial work-up, as our patient’s symptoms were most pronounced during physical activity. But this condition usually responds to antiepileptics, and carbamazepine and phenytoin were each tried for multiple months early in his evaluation without benefit.

3 factors led to a diagnosis of focal limb dystonia: Only our patient’s right arm was affected, his laboratory and imaging work-ups were negative, and he didn’t respond to antiepileptic treatment. Characterization of a movement disorder is based upon phenomenology. In this case, the patient had sustained abnormal posturing at the shoulder during right upper limb activation, which was only triggered with specific voluntary actions. This was consistent with dystonia, a movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal movements and/or postures—often initiated or worsened by voluntary action.2

DISCUSSION

The “yips,” or intermittent, transient tremors, jerks, or spasms3 that are seen in athletes, are well-documented in the lay press, but haven’t been significantly addressed in the medical literature.4 Stigma surrounding the condition among athletes likely leads to under-reporting. Athletes typically experience yips with fine motor movements, such as short putts in golf and pitching in baseball. In fact, while the majority of the medical literature on yips revolves around golfers, many talented baseball players have had their careers altered by the condition. The yips may also affect movements in sports like darts, cricket, table tennis, and billiards.

In 1984, dystonia was defined as a disorder of sensorimotor integration that results in co-contraction of agonist/antagonist muscles, and may be characterized by state dependence (exacerbation with specific activities) or sensory tricks (amelioration with specific types of sensory input).5 In 2013, the definition was revised to remove “co-contraction” from the definition because phenomenology alone is sufficient to make the diagnosis.1

Many athletes and sports fans believe the yips are caused by performance anxiety or related phobias, but evidence suggests that many athletes with the movement disorder may actually have focal limb dystonia.6,7 The yips can, however, lead to performance anxiety,3 but there has been no difference noted between the anxiety level of golfers with or without the yips.7 Psychological treatment approaches are commonly employed, but surface electromyograms have shown abnormal co-contraction of wrist flexor and extensor muscles in 5 out of 10 golfers with the yips (but 0 of those without) while putting—which is consistent with focal limb dystonia.8

Botulinum toxin injections are Tx of choice, but can cause weakness

Muscle relaxers, such as baclofen and benzodiazepines, as well as dopamine antagonists, can ameliorate dystonia.9 Focal limb dystonia may also respond to the antispasmodic trihexyphenidyl, but the dose must often be limited due to adverse effects such as nausea, dizziness, and anxiety.10

Botulinum toxin injections have proven effective for focal limb dystonia11 and are considered the treatment of choice. However, there are few reports on their use in athletes, where the adverse effect of weakness could affect performance. One case report also showed improvement of yips with acupuncture, although this has not been extensively studied.12

Our patient didn’t respond to low-dose (2 mg twice a day) trihexyphenidyl. Tetrabenazine, a dopamine depletor frequently used for hyperkinetic disorders, was not effective at 25 mg taken prior to coaching sessions. Higher doses of an anticholinergic could have been effective, but the patient declined our recommendation to pursue this (or botulinum toxin injections). He decided instead to train himself to use his left arm while coaching.

THE TAKEAWAY

Athletes who play sports that require precision movements commonly develop the yips. While the prevailing theory among athletes is that this is a psychological phenomenon, evidence shows that this may in fact be a neurologic focal dystonia caused by repetitive use. Greater awareness of yips as a possible organic, treatable neurologic condition is needed in order to stimulate more research on this topic.

THE CASE

A 31-year-old right-handed college baseball coach presented to his family physician (FP) with concerns about the “yips” in his right arm. His ability to throw a baseball had been gradually deteriorating. Involuntary upper right arm muscle contractions and spasms, which began intermittently when he was a teenager, were now a real problem for him as an adult. (See the video below.) The patient was having difficulty rolling a baseball underhand to players as part of infield practice and he was experiencing muscle spasms when lifting his right arm over his head. “Twitches” in the patient’s upper arm were making drinking difficult, but he had no problems feeding himself, writing, or performing other basic activities of daily living.

The patient experienced the same symptoms whether it was baseball season or not. He hadn’t noticed a change in symptoms with caffeine and denied use of any other stimulants in the last 4 years. His symptoms didn’t improve or worsen with greater or lesser quantity or quality of sleep or when he concentrated on stifling the involuntary movements. He had attempted to learn to throw left-handed to overcome the impairment, but was concerned that the same problem would occur in his left arm.

The patient had previously worked with a sports psychologist and hypnotherapist to overcome any potential subconscious performance anxiety, but this hadn’t helped. Stretching and strengthening with a physical therapist and numerous sessions with an acupuncturist hadn’t helped either. Despite this, he believed the problem to be primarily psychological.

The patient’s history included mild attention deficit disorder and exercise-induced asthma; his family history was negative for any movement or psychiatric disorders. He had 2 dislocation repairs on his left, non-throwing shoulder in his early twenties. His medications included fluticasone-salmeterol twice daily and albuterol, as needed.

The patient denied myalgia or arthralgia, decreased passive range of motion, shoulder or arm weakness, swelling, or muscle atrophy. He also didn’t have paresthesias in his right arm or hand, a resting tremor, difficulty moving (other than drinking from a cup), difficulty moving other extremities, dizziness, imbalance, or seizures.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. He had full range of motion and 5 out of 5 strength without pain during right shoulder abduction, external and internal rotation, an empty can test, a lower back lift off (Gerber’s) test, and a test of bicep and tricep strength, along with negative Neer and Hawkins tests.

There was no evidence of muscle wasting or asymmetry in the bilateral upper extremities. The patient’s deep tendon reflex grade was 2+ out of 4 in both of his arms. He didn’t have a sensory deficit to light touch in areas of C5 to T1 and he had normal cranial nerves II to XII. He had normal rapid alternating movements, heel-to-shin testing, and finger-to-nose testing, as well as a normal gait and Romberg test.

The patient provided a video showing the abnormal involuntary flexion of his shoulder when attempting to throw a baseball.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s FP was aware of the “yips,” a condition that is commonly viewed as psychological or related to performance anxiety. (The “yips” are colloquially known as “Steve Blass Disease”—named after a Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher who suddenly lost the ability to control his pitches.1) But based on the patient’s clinical presentation and history of seeing a number of mental health care providers—in addition to his worsening symptoms—the FP ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. The MRI turned out to be unremarkable, so the patient was referred to Neurology.

In the general neurology clinic, a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease (a condition that leads to excess copper deposition in multiple organ systems, including the nervous system) was considered, as it can cause symptoms similar to those our patient was experiencing. However, a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, ceruloplasmin test, and copper level were all normal, effectively ruling it out. An MRI of the cervical spine showed mild to moderate right foraminal stenosis at C3-4 and C5-6, but this did not explain the patient’s symptoms.

A diagnosis of paroxysmal exercise-induced dystonia was also considered at the time of the initial work-up, as our patient’s symptoms were most pronounced during physical activity. But this condition usually responds to antiepileptics, and carbamazepine and phenytoin were each tried for multiple months early in his evaluation without benefit.

3 factors led to a diagnosis of focal limb dystonia: Only our patient’s right arm was affected, his laboratory and imaging work-ups were negative, and he didn’t respond to antiepileptic treatment. Characterization of a movement disorder is based upon phenomenology. In this case, the patient had sustained abnormal posturing at the shoulder during right upper limb activation, which was only triggered with specific voluntary actions. This was consistent with dystonia, a movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal movements and/or postures—often initiated or worsened by voluntary action.2

DISCUSSION

The “yips,” or intermittent, transient tremors, jerks, or spasms3 that are seen in athletes, are well-documented in the lay press, but haven’t been significantly addressed in the medical literature.4 Stigma surrounding the condition among athletes likely leads to under-reporting. Athletes typically experience yips with fine motor movements, such as short putts in golf and pitching in baseball. In fact, while the majority of the medical literature on yips revolves around golfers, many talented baseball players have had their careers altered by the condition. The yips may also affect movements in sports like darts, cricket, table tennis, and billiards.

In 1984, dystonia was defined as a disorder of sensorimotor integration that results in co-contraction of agonist/antagonist muscles, and may be characterized by state dependence (exacerbation with specific activities) or sensory tricks (amelioration with specific types of sensory input).5 In 2013, the definition was revised to remove “co-contraction” from the definition because phenomenology alone is sufficient to make the diagnosis.1

Many athletes and sports fans believe the yips are caused by performance anxiety or related phobias, but evidence suggests that many athletes with the movement disorder may actually have focal limb dystonia.6,7 The yips can, however, lead to performance anxiety,3 but there has been no difference noted between the anxiety level of golfers with or without the yips.7 Psychological treatment approaches are commonly employed, but surface electromyograms have shown abnormal co-contraction of wrist flexor and extensor muscles in 5 out of 10 golfers with the yips (but 0 of those without) while putting—which is consistent with focal limb dystonia.8

Botulinum toxin injections are Tx of choice, but can cause weakness

Muscle relaxers, such as baclofen and benzodiazepines, as well as dopamine antagonists, can ameliorate dystonia.9 Focal limb dystonia may also respond to the antispasmodic trihexyphenidyl, but the dose must often be limited due to adverse effects such as nausea, dizziness, and anxiety.10

Botulinum toxin injections have proven effective for focal limb dystonia11 and are considered the treatment of choice. However, there are few reports on their use in athletes, where the adverse effect of weakness could affect performance. One case report also showed improvement of yips with acupuncture, although this has not been extensively studied.12

Our patient didn’t respond to low-dose (2 mg twice a day) trihexyphenidyl. Tetrabenazine, a dopamine depletor frequently used for hyperkinetic disorders, was not effective at 25 mg taken prior to coaching sessions. Higher doses of an anticholinergic could have been effective, but the patient declined our recommendation to pursue this (or botulinum toxin injections). He decided instead to train himself to use his left arm while coaching.

THE TAKEAWAY

Athletes who play sports that require precision movements commonly develop the yips. While the prevailing theory among athletes is that this is a psychological phenomenon, evidence shows that this may in fact be a neurologic focal dystonia caused by repetitive use. Greater awareness of yips as a possible organic, treatable neurologic condition is needed in order to stimulate more research on this topic.

1. Baseball’s head cases often prove baffling. USA Today Baseball Weekly. 2001. Available at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/bbw/2001-02-07/2001-02-07-head.htm. Accessed March 15, 2017.

2. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28:863-873.

3. Dhungana S, Jankovic J. Yips and other movement disorders in golfers. Mov Disord. 2013;28:576-581.

4. Stacy MA, ed. Handbook of dystonia. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc; 2007.

5. Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB. Classification and investigation of dystonia. In: Marsden CD, Fahn S, eds. Movement disorders 2. London: Butterworths; 1987:332-358.

6. Smith AM, Adler CH, Crews D, et al. The ‘yips’ in golf: a continuum between a focal dystonia and choking. Sports Med. 2003;33:13-31.

7. Sachdev P. Golfers’ cramp: clinical characteristics and evidence against it being an anxiety disorder. Mov Disord. 1992;7:326-332.

8. Adler CH, Crews D, Hentz JG, et al. Abnormal co-contraction in yips-affected but not unaffected golfers: evidence for focal dystonia. Neurology. 2005;64:1813-1814.

9. Jankovic J. Treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:844-856.

10. Jankovic J. Treatment of dystonia. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:864-872.

11. Lungu C, Karp BI, Alter K, et al. Long-term follow-up of botulinum toxin therapy for focal hand dystonia: outcome at 10 years or more. Mov Disord. 2011;26:750-753.

12. Rosted P. Acupuncture for treatment of the yips?—a case report. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:188-189.

1. Baseball’s head cases often prove baffling. USA Today Baseball Weekly. 2001. Available at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/bbw/2001-02-07/2001-02-07-head.htm. Accessed March 15, 2017.

2. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28:863-873.

3. Dhungana S, Jankovic J. Yips and other movement disorders in golfers. Mov Disord. 2013;28:576-581.

4. Stacy MA, ed. Handbook of dystonia. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc; 2007.

5. Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB. Classification and investigation of dystonia. In: Marsden CD, Fahn S, eds. Movement disorders 2. London: Butterworths; 1987:332-358.

6. Smith AM, Adler CH, Crews D, et al. The ‘yips’ in golf: a continuum between a focal dystonia and choking. Sports Med. 2003;33:13-31.

7. Sachdev P. Golfers’ cramp: clinical characteristics and evidence against it being an anxiety disorder. Mov Disord. 1992;7:326-332.

8. Adler CH, Crews D, Hentz JG, et al. Abnormal co-contraction in yips-affected but not unaffected golfers: evidence for focal dystonia. Neurology. 2005;64:1813-1814.

9. Jankovic J. Treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:844-856.

10. Jankovic J. Treatment of dystonia. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:864-872.

11. Lungu C, Karp BI, Alter K, et al. Long-term follow-up of botulinum toxin therapy for focal hand dystonia: outcome at 10 years or more. Mov Disord. 2011;26:750-753.

12. Rosted P. Acupuncture for treatment of the yips?—a case report. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:188-189.

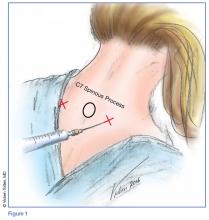

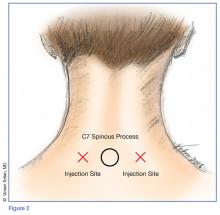

Paraspinous Cervical Nerve Block for Primary Headache

Headaches—pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck—are a very common reason for ED visits.1 In 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that 46.5% of the population in North and South America aged 18 to 65 years old experienced at least one headache within the previous year.1

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder that afflicts 18% of US women and 9% of US men,2 resulting in at least 1.2 million visits to US EDs annually.1 The economic cost resulting from migraine-related loss of productive time in the US workforce is more than $13 billion per year, most of which is in the form of reduced work productivity.3 Management and treatment for migraine headache in the ED commonly include intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications, fluids, or oxygen. While ultimately effective, these methods require nursing care and additional time for posttreatment monitoring, both of which adversely affect patient flow.

In 2006, Mellick et al4 described the safety and effectiveness of paraspinous cervical nerve block (PCNB) to abort migraine headaches. Despite its demonstrated efficacy and safety, a decade later, PCNB is still rarely used. Friedman et al5 ranked peripheral nerve blocks as the fourth step in management suggestions for primary headache.

Case Reports of Headache Patients

We report on seven headache patients we treated in our ED with PCNB who had good-to-complete resolution of pain, suggesting that PCNB is efficacious and can potentially shorten the ED length of stay. This series of seven patients (six female, one male) was a convenience sample of primary headache patients who presented over a 10-month period and were safely and rapidly treated with PCNB (Table).

In each case, the PCNB procedure was explained to the patient and consent was obtained. Each patient was treated with a total of 3 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine injected into the posterior neck according to the method described by Mellick et al.4 Our seven patients achieved an average 5-point reduction in pain on a 10-point pain scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worse possible pain.

Other than the provision of medications, no nursing assistance was required. Only one of the patients required further treatment after the PCNB, and none had an adverse reaction. All of the patients reported that their headaches were similar in nature to past headaches. Based on their history and physical examination, none were diagnosed to be experiencing a secondary, more serious cause of headache, and none subsequently returned to our institution with a secondary type of headache.

The Paraspinal Cervical Nerve Block

Paraspinous cervical nerve block requires less time to administer and recovery is shorter than that from IM or IV opioids, sedatives, or neuroleptics. It is an easy technique to teach since it requires bilateral injections.

Technique

Prior to the procedure, cleanse the bilateral paravertebral zones surrounding C6 and C7 with chlorhexidine. Next, fill a 3 cc syringe using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Once the injection is complete, withdraw the needle completely, and compress and massage the injection site to facilitate anesthetic diffusion to surrounding tissues.

Indications

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is an appropriate treatment only for patients who are having a typical episode of chronic, recurring headaches, whose history and physical examination do not suggest the need for any further diagnostic work-up, and who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, require only pain relief.

Contraindications

A patient should not be considered for PCNB if he or she has a new-onset headache, fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, meningismus, findings suggestive of meningitis, papilledema, increased intracranial pressure from a space-occupying lesion, recent head trauma with concern for intracranial hemorrhage, or suspicion of an alternate diagnosis.

Efficacy and Patient Response

Paraspinous cervical nerve block has been shown to decrease pain in patients who had failed standard migraine therapy and patients reported no complications. Of the seven patients in this case report, only one patient received opioids in the ED and none received prescriptions for opioids upon discharge for outpatient use.

Mellick and Mellick6 have postulated that pain may be modified due to the PCNB effect on the convergence of the trigeminal nerve with sensory fibers from the upper cervical roots. Since cervical innervation provides feeling to the head and upper neck, blocking this input can ameliorate pain.6

Summary

This series of seven patients provides further evidence of the effectiveness of PCNB in relieving headache symptoms for patients with recurrent, primary headaches when a secondary, more serious cause has been clinically excluded. Each of the seven patients had marked improvement of their pain and required only minimal nursing attention; moreover, all stated they would willingly undergo the procedure for future painful episodes.

Although there were no reported complications, this series is too small to demonstrate complete safety of the procedure. While this report is limited by a small sample size, it demonstrates that this is a quick, effective, and easily learned method of addressing a common ED complaint that obviates the need for parenteral medications and offers a potentially decreased patient length of stay.

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is a promising modality of treatment of ED patients who present with headache and migraine symptoms who do not respond to their outpatient “rescue” therapy. This procedure should be considered as an early treatment for migraine and other primary headaches unless contraindicated.

1. World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders_results.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(9):1065-1072. doi:10.1177/0333102409355601.

3. Chawla J. Migraine headache. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview. Accessed February 9, 2017.

4. Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1-year retrospective review of 417 patients. Headache. 2006;46(9):1441-1449.

5. Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:301-309.

6. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections—another treatment option for headaches. http://www.neurologist-doctor.com/images/Mellick_Headache_injections.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

Headaches—pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck—are a very common reason for ED visits.1 In 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that 46.5% of the population in North and South America aged 18 to 65 years old experienced at least one headache within the previous year.1

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder that afflicts 18% of US women and 9% of US men,2 resulting in at least 1.2 million visits to US EDs annually.1 The economic cost resulting from migraine-related loss of productive time in the US workforce is more than $13 billion per year, most of which is in the form of reduced work productivity.3 Management and treatment for migraine headache in the ED commonly include intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications, fluids, or oxygen. While ultimately effective, these methods require nursing care and additional time for posttreatment monitoring, both of which adversely affect patient flow.

In 2006, Mellick et al4 described the safety and effectiveness of paraspinous cervical nerve block (PCNB) to abort migraine headaches. Despite its demonstrated efficacy and safety, a decade later, PCNB is still rarely used. Friedman et al5 ranked peripheral nerve blocks as the fourth step in management suggestions for primary headache.

Case Reports of Headache Patients

We report on seven headache patients we treated in our ED with PCNB who had good-to-complete resolution of pain, suggesting that PCNB is efficacious and can potentially shorten the ED length of stay. This series of seven patients (six female, one male) was a convenience sample of primary headache patients who presented over a 10-month period and were safely and rapidly treated with PCNB (Table).

In each case, the PCNB procedure was explained to the patient and consent was obtained. Each patient was treated with a total of 3 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine injected into the posterior neck according to the method described by Mellick et al.4 Our seven patients achieved an average 5-point reduction in pain on a 10-point pain scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worse possible pain.

Other than the provision of medications, no nursing assistance was required. Only one of the patients required further treatment after the PCNB, and none had an adverse reaction. All of the patients reported that their headaches were similar in nature to past headaches. Based on their history and physical examination, none were diagnosed to be experiencing a secondary, more serious cause of headache, and none subsequently returned to our institution with a secondary type of headache.

The Paraspinal Cervical Nerve Block

Paraspinous cervical nerve block requires less time to administer and recovery is shorter than that from IM or IV opioids, sedatives, or neuroleptics. It is an easy technique to teach since it requires bilateral injections.

Technique

Prior to the procedure, cleanse the bilateral paravertebral zones surrounding C6 and C7 with chlorhexidine. Next, fill a 3 cc syringe using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Once the injection is complete, withdraw the needle completely, and compress and massage the injection site to facilitate anesthetic diffusion to surrounding tissues.

Indications

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is an appropriate treatment only for patients who are having a typical episode of chronic, recurring headaches, whose history and physical examination do not suggest the need for any further diagnostic work-up, and who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, require only pain relief.

Contraindications

A patient should not be considered for PCNB if he or she has a new-onset headache, fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, meningismus, findings suggestive of meningitis, papilledema, increased intracranial pressure from a space-occupying lesion, recent head trauma with concern for intracranial hemorrhage, or suspicion of an alternate diagnosis.

Efficacy and Patient Response

Paraspinous cervical nerve block has been shown to decrease pain in patients who had failed standard migraine therapy and patients reported no complications. Of the seven patients in this case report, only one patient received opioids in the ED and none received prescriptions for opioids upon discharge for outpatient use.

Mellick and Mellick6 have postulated that pain may be modified due to the PCNB effect on the convergence of the trigeminal nerve with sensory fibers from the upper cervical roots. Since cervical innervation provides feeling to the head and upper neck, blocking this input can ameliorate pain.6

Summary

This series of seven patients provides further evidence of the effectiveness of PCNB in relieving headache symptoms for patients with recurrent, primary headaches when a secondary, more serious cause has been clinically excluded. Each of the seven patients had marked improvement of their pain and required only minimal nursing attention; moreover, all stated they would willingly undergo the procedure for future painful episodes.

Although there were no reported complications, this series is too small to demonstrate complete safety of the procedure. While this report is limited by a small sample size, it demonstrates that this is a quick, effective, and easily learned method of addressing a common ED complaint that obviates the need for parenteral medications and offers a potentially decreased patient length of stay.

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is a promising modality of treatment of ED patients who present with headache and migraine symptoms who do not respond to their outpatient “rescue” therapy. This procedure should be considered as an early treatment for migraine and other primary headaches unless contraindicated.

Headaches—pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck—are a very common reason for ED visits.1 In 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that 46.5% of the population in North and South America aged 18 to 65 years old experienced at least one headache within the previous year.1

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder that afflicts 18% of US women and 9% of US men,2 resulting in at least 1.2 million visits to US EDs annually.1 The economic cost resulting from migraine-related loss of productive time in the US workforce is more than $13 billion per year, most of which is in the form of reduced work productivity.3 Management and treatment for migraine headache in the ED commonly include intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications, fluids, or oxygen. While ultimately effective, these methods require nursing care and additional time for posttreatment monitoring, both of which adversely affect patient flow.

In 2006, Mellick et al4 described the safety and effectiveness of paraspinous cervical nerve block (PCNB) to abort migraine headaches. Despite its demonstrated efficacy and safety, a decade later, PCNB is still rarely used. Friedman et al5 ranked peripheral nerve blocks as the fourth step in management suggestions for primary headache.

Case Reports of Headache Patients

We report on seven headache patients we treated in our ED with PCNB who had good-to-complete resolution of pain, suggesting that PCNB is efficacious and can potentially shorten the ED length of stay. This series of seven patients (six female, one male) was a convenience sample of primary headache patients who presented over a 10-month period and were safely and rapidly treated with PCNB (Table).

In each case, the PCNB procedure was explained to the patient and consent was obtained. Each patient was treated with a total of 3 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine injected into the posterior neck according to the method described by Mellick et al.4 Our seven patients achieved an average 5-point reduction in pain on a 10-point pain scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worse possible pain.

Other than the provision of medications, no nursing assistance was required. Only one of the patients required further treatment after the PCNB, and none had an adverse reaction. All of the patients reported that their headaches were similar in nature to past headaches. Based on their history and physical examination, none were diagnosed to be experiencing a secondary, more serious cause of headache, and none subsequently returned to our institution with a secondary type of headache.

The Paraspinal Cervical Nerve Block

Paraspinous cervical nerve block requires less time to administer and recovery is shorter than that from IM or IV opioids, sedatives, or neuroleptics. It is an easy technique to teach since it requires bilateral injections.

Technique

Prior to the procedure, cleanse the bilateral paravertebral zones surrounding C6 and C7 with chlorhexidine. Next, fill a 3 cc syringe using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Once the injection is complete, withdraw the needle completely, and compress and massage the injection site to facilitate anesthetic diffusion to surrounding tissues.

Indications

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is an appropriate treatment only for patients who are having a typical episode of chronic, recurring headaches, whose history and physical examination do not suggest the need for any further diagnostic work-up, and who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, require only pain relief.

Contraindications

A patient should not be considered for PCNB if he or she has a new-onset headache, fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, meningismus, findings suggestive of meningitis, papilledema, increased intracranial pressure from a space-occupying lesion, recent head trauma with concern for intracranial hemorrhage, or suspicion of an alternate diagnosis.

Efficacy and Patient Response

Paraspinous cervical nerve block has been shown to decrease pain in patients who had failed standard migraine therapy and patients reported no complications. Of the seven patients in this case report, only one patient received opioids in the ED and none received prescriptions for opioids upon discharge for outpatient use.

Mellick and Mellick6 have postulated that pain may be modified due to the PCNB effect on the convergence of the trigeminal nerve with sensory fibers from the upper cervical roots. Since cervical innervation provides feeling to the head and upper neck, blocking this input can ameliorate pain.6

Summary

This series of seven patients provides further evidence of the effectiveness of PCNB in relieving headache symptoms for patients with recurrent, primary headaches when a secondary, more serious cause has been clinically excluded. Each of the seven patients had marked improvement of their pain and required only minimal nursing attention; moreover, all stated they would willingly undergo the procedure for future painful episodes.

Although there were no reported complications, this series is too small to demonstrate complete safety of the procedure. While this report is limited by a small sample size, it demonstrates that this is a quick, effective, and easily learned method of addressing a common ED complaint that obviates the need for parenteral medications and offers a potentially decreased patient length of stay.

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is a promising modality of treatment of ED patients who present with headache and migraine symptoms who do not respond to their outpatient “rescue” therapy. This procedure should be considered as an early treatment for migraine and other primary headaches unless contraindicated.

1. World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders_results.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(9):1065-1072. doi:10.1177/0333102409355601.

3. Chawla J. Migraine headache. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview. Accessed February 9, 2017.

4. Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1-year retrospective review of 417 patients. Headache. 2006;46(9):1441-1449.

5. Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:301-309.

6. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections—another treatment option for headaches. http://www.neurologist-doctor.com/images/Mellick_Headache_injections.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

1. World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders_results.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(9):1065-1072. doi:10.1177/0333102409355601.

3. Chawla J. Migraine headache. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview. Accessed February 9, 2017.

4. Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1-year retrospective review of 417 patients. Headache. 2006;46(9):1441-1449.

5. Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:301-309.

6. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections—another treatment option for headaches. http://www.neurologist-doctor.com/images/Mellick_Headache_injections.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

Hypothyroidism-Induced Stercoral Sigmoid Colonic Perforation

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, abdominal pain is the leading reason for ED visits in the United States, with approximately 10 million visits per year.1 Though a large number of presentations are due to nontraumatic causes of abdominal pain, one etiology is among the most time-sensitive and critical diagnoses: acute colonic perforation.

Colonic perforations can be caused by diverticulitis, trauma, malignancy, ulcerative colitis, and other etiologies.2 A rare, yet life-threatening cause of colonic perforation, of which only a few cases have been documented in the literature, is stercoral colonic perforation.2

Regardless of the etiology, the critical actions for any colonic perforation are quick recognition, medical stabilization, and surgical evaluation. This case report highlights the diagnosis and treatment of acute stercoral colonic perforation with peritonitis secondary to hypothyroidism.

Case

A 49-year-old woman with a medical history significant for hypothyroidism presented to the ED for evaluation of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting that started in the early evening of presentation. The patient denied any previous pain or associated symptoms, and said she had a small, hard bowel movement 1 day prior to arrival. She began experiencing mild abdominal pain on the morning of presentation. Her symptoms acutely worsened at approximately 5:00

On physical examination, her vital signs were: heart rate, 156 beats/min; blood pressure, 134/84 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, 97.4°F. The patient appeared ill and diaphoretic, writhing on the stretcher. Abdominal examination was significant for diminished bowel sounds, diffuse abdominal distension, rigidity, and tenderness with light palpation.

Laboratory evaluation showed an elevated lactic acid level of 7.7 mmol/L, a white blood cell count of 7,200 cells/mm3 (segment form, 69.5%), and the following abnormal blood chemistry results: creatinine, 2.08 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 176 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 138 U/L; and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 225.3 mcIU/mL. Other laboratory results were within normal range. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a rate of 154 beats/min, a QTc within normal limits, and no ST elevations or depressions.

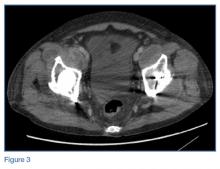

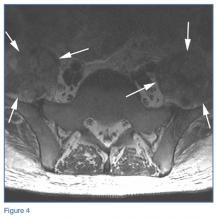

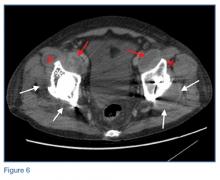

An abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed free air, free fluid, and possibly stool within the abdomen and pelvis. The findings were consistent with a ruptured hollow viscus, possibly a sigmoid colonic perforation. The radiologist also noted hepatomegaly and significant hepatic steatosis. A surgeon was immediately notified and evaluated the patient in the ED. The working diagnosis was stercoral colonic perforation secondary to severe hypothyroidism, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating room for repair.

Intraoperatively, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed gross fecal contamination of the abdomen. The surgeon noted that there was fecal staining along the serosal surface of the small bowel and throughout the pelvis. There were also large, hard stool balls outside of the colon. The perforation was along the mesenteric surface of the sigmoid just above the rectosigmoid junction.

The abdomen was copiously irrigated, the perforated segment was resected, and a Hartmann colostomy was created. The diagnosis was stercoral sigmoid perforation with peritonitis, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for antibiotic treatment and further medical care, including intravenous (IV) levothyroxine.

She was extubated uneventfully on postoperative day 2, and the acute renal failure improved with supportive care only. Her bowel function slowly returned without complication. She was switched to oral levothyroxine on postoperative day 3. On day 13, she was given strict instructions for continuation of her thyroid medication and close monitoring for postsurgical complications, and was discharged home with appropriate follow-up.

Discussion

Multiple contributing factors can lead to bowel perforation. In this case, severe hypothyroidism with constipation caused a colonic perforation. Our patient had severe constipation that increased intraluminal pressure, causing the bowel wall to become ischemic and subsequently perforate.3 Any disease that causes significant constipation or obstruction of transit could lead to the same catastrophic result.

According to Huang et al,4 as of 2002, fewer than 90 cases of general stercoral bowel perforation had been reported, with no clear age range. However, patients in their mid-50s to mid-60s appear to be the most commonly affected age group.4 Our patient was younger than this age group, making identification of the problem by age alone difficult.

Hypothyroidism

The incidence of hypothyroidism in iodine-replete communities varies between 1% to 2% of the general population.5 The condition is more common in older women, affecting approximately 10% of those over age 65 years. In the United States, the prevalence of biochemical hypothyroidism is 4.6%; however, clinically evident hypothyroidism is present in only 0.3%.6 Common causes for hypothyroidism are listed in the Table.7,8

Myxedema Coma

Untreated, hypothyroidism can lead to potentially fatal conditions, such as myxedema coma, which is characterized by hypothermia, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression, and altered mental status.7 Severe myxedema coma can result in cardiovascular collapse, and eventual death. Electrocardiography findings of severe hypothyroidism include bradycardia, low-voltage QRS, and widespread T-wave inversions.7 Our patient was tachycardic and did not have any acute findings to suggest myxedema coma.

Treatment for myxedema coma includes supportive care with ventilatory support and pressor support if necessary. Patients should be given IV hydrocortisone, 100 mg, to treat possible adrenal insufficiency and T4, 4 mcg/kg by slow IV infusion.7 Caution should be taken if giving a patient T3 due to the risk of dysrhythmias and myocardial infarction (MI).7 As our patient was not displaying myxedema coma, the surgeon elected not to start IV thyroid replacement to avoid exacerbating the patient’s tachycardia and possibly precipitating an MI intraoperatively.

Conclusion

Our case underscores the importance of promptly recognizing the signs and symptoms of stercoral colonic perforation in patients who present with nontraumatic abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting. Although stercoral colonic perforation is a rare cause of nontraumatic abdominal pain, as with any type of colonic perforation, it constitutes a life-threatening medical emergency. As our case illustrates, prompt diagnosis through a thorough history taking, physical examination, and laboratory and imaging studies is critical to ensure medical stabilization and surgical management to reduce morbidity and mortality.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Table 10. Ten leading principal reasons for emergency department visits, by patient age and sex: United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2017.

2. Nam JK, Kim BS, Kim KS, Moon DJ. Clinical analysis of stercoral perforation of the colon. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:46-51.

3. Heffernan C, Pachter HL, Megibow AJ, Macari M. Stercoral colitis leading to fatal peritonitis: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(4):1189-1193. doi:10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841189.

4. Huang WS, Wang CS, Hsieh CC, Lin PY, Chin CC, Wang JY. Management of patients with stercoral perforation of the sigmoid colon: Report of five cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(3):500-503.

5. Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):526-534.

6. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):489-499.

7. Idrose AM. Hypothyroidism. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:1469-1472.

8. Skugor M. Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism. Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education. August 2014. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/endocrinology/hypothyroidism-and-hyperthyroidism/. Accessed March 3, 2017.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, abdominal pain is the leading reason for ED visits in the United States, with approximately 10 million visits per year.1 Though a large number of presentations are due to nontraumatic causes of abdominal pain, one etiology is among the most time-sensitive and critical diagnoses: acute colonic perforation.

Colonic perforations can be caused by diverticulitis, trauma, malignancy, ulcerative colitis, and other etiologies.2 A rare, yet life-threatening cause of colonic perforation, of which only a few cases have been documented in the literature, is stercoral colonic perforation.2

Regardless of the etiology, the critical actions for any colonic perforation are quick recognition, medical stabilization, and surgical evaluation. This case report highlights the diagnosis and treatment of acute stercoral colonic perforation with peritonitis secondary to hypothyroidism.

Case