User login

Pancreatitis: The great masquerader?

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1 week of bilateral lower-extremity joint pain associated with painful skin nodules. He had a history of chronic recurrent alcoholic pancreatitis. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Results of initial laboratory testing:

- Alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L (reference range 36–108)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h (0–15)

- Lipase 20,000 U/L (16–61).

AN ATYPICAL PRESENTATION OF A COMMON DISEASE

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare systemic complication of pancreatic disease occurring most often in middle-aged men with an acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis and a history of alcohol use disorder.1,2 It is also associated with pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreas divisum, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–6 It is characterized by systemic fat necrosis secondary to severe and persistent elevation of pancreatic enzymes. The mortality rate is high; in a case series of 25 patients, 24% died within days to weeks after admission.1

Clinical presentation and treatment

The diagnosis of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is often missed. Abdominal pain is mild or absent in over 60% of patients.1 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis.

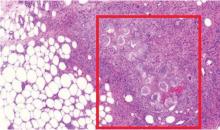

The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis (including Löfgren syndrome), subcutaneous infection, and vasculitis. “Ghost adipocytes” on skin biopsy are pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and are the result of saponification; they appear to be anuclear, with basophilic material throughout the cytoplasm.7 Arthrocentesis of affected joints may reveal thick, creamy material, rich in triglycerides, which is diagnostic of pancreatic arthritis.1,8

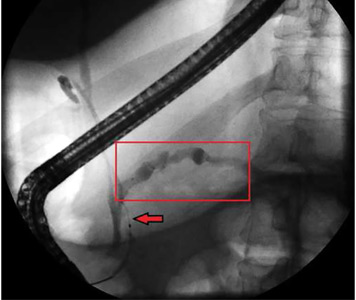

Treatment relies on correction of the underlying pancreatic pathology. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome has been successfully treated by cyst gastrostomy, pancreatic duct stenting, and pancreaticoduodenectomy.7,9–11

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome mimics rheumatologic disease and often presents without abdominal pain.

- The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum lipase or amylase, pancreatic imaging showing pancreatitis, and ghost adipocytes on skin biopsy.

- Treatment is aimed at correcting the underlying pancreatic abnormality.

- Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39(5):417–423. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.001

- Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(3):259–261. pmid:11246359

- Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9(9):1145–1150. pmid:20865849

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med 1994; 87(6):361–362. pmid:8046712

- Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13(4):e74–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01548.x

- Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14(2 pt 2):331–334. pmid:3950133

- Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34(7):680–683. pmid:7670790

- Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2006; 35(1):72–74. doi:10.1080/03009740500228073

- Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(2):456–458. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.040

- Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(9):1835–1837. pmid:8792709

- Potts JR. Pancreatic-portal vein fistula with disseminated fat necrosis treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy. South Med J 1991; 84(5):632–635. pmid:2035087

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1 week of bilateral lower-extremity joint pain associated with painful skin nodules. He had a history of chronic recurrent alcoholic pancreatitis. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Results of initial laboratory testing:

- Alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L (reference range 36–108)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h (0–15)

- Lipase 20,000 U/L (16–61).

AN ATYPICAL PRESENTATION OF A COMMON DISEASE

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare systemic complication of pancreatic disease occurring most often in middle-aged men with an acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis and a history of alcohol use disorder.1,2 It is also associated with pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreas divisum, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–6 It is characterized by systemic fat necrosis secondary to severe and persistent elevation of pancreatic enzymes. The mortality rate is high; in a case series of 25 patients, 24% died within days to weeks after admission.1

Clinical presentation and treatment

The diagnosis of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is often missed. Abdominal pain is mild or absent in over 60% of patients.1 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis (including Löfgren syndrome), subcutaneous infection, and vasculitis. “Ghost adipocytes” on skin biopsy are pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and are the result of saponification; they appear to be anuclear, with basophilic material throughout the cytoplasm.7 Arthrocentesis of affected joints may reveal thick, creamy material, rich in triglycerides, which is diagnostic of pancreatic arthritis.1,8

Treatment relies on correction of the underlying pancreatic pathology. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome has been successfully treated by cyst gastrostomy, pancreatic duct stenting, and pancreaticoduodenectomy.7,9–11

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome mimics rheumatologic disease and often presents without abdominal pain.

- The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum lipase or amylase, pancreatic imaging showing pancreatitis, and ghost adipocytes on skin biopsy.

- Treatment is aimed at correcting the underlying pancreatic abnormality.

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1 week of bilateral lower-extremity joint pain associated with painful skin nodules. He had a history of chronic recurrent alcoholic pancreatitis. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Results of initial laboratory testing:

- Alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L (reference range 36–108)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h (0–15)

- Lipase 20,000 U/L (16–61).

AN ATYPICAL PRESENTATION OF A COMMON DISEASE

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare systemic complication of pancreatic disease occurring most often in middle-aged men with an acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis and a history of alcohol use disorder.1,2 It is also associated with pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreas divisum, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–6 It is characterized by systemic fat necrosis secondary to severe and persistent elevation of pancreatic enzymes. The mortality rate is high; in a case series of 25 patients, 24% died within days to weeks after admission.1

Clinical presentation and treatment

The diagnosis of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is often missed. Abdominal pain is mild or absent in over 60% of patients.1 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis (including Löfgren syndrome), subcutaneous infection, and vasculitis. “Ghost adipocytes” on skin biopsy are pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and are the result of saponification; they appear to be anuclear, with basophilic material throughout the cytoplasm.7 Arthrocentesis of affected joints may reveal thick, creamy material, rich in triglycerides, which is diagnostic of pancreatic arthritis.1,8

Treatment relies on correction of the underlying pancreatic pathology. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome has been successfully treated by cyst gastrostomy, pancreatic duct stenting, and pancreaticoduodenectomy.7,9–11

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome mimics rheumatologic disease and often presents without abdominal pain.

- The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum lipase or amylase, pancreatic imaging showing pancreatitis, and ghost adipocytes on skin biopsy.

- Treatment is aimed at correcting the underlying pancreatic abnormality.

- Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39(5):417–423. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.001

- Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(3):259–261. pmid:11246359

- Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9(9):1145–1150. pmid:20865849

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med 1994; 87(6):361–362. pmid:8046712

- Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13(4):e74–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01548.x

- Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14(2 pt 2):331–334. pmid:3950133

- Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34(7):680–683. pmid:7670790

- Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2006; 35(1):72–74. doi:10.1080/03009740500228073

- Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(2):456–458. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.040

- Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(9):1835–1837. pmid:8792709

- Potts JR. Pancreatic-portal vein fistula with disseminated fat necrosis treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy. South Med J 1991; 84(5):632–635. pmid:2035087

- Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39(5):417–423. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.001

- Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(3):259–261. pmid:11246359

- Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9(9):1145–1150. pmid:20865849

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med 1994; 87(6):361–362. pmid:8046712

- Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13(4):e74–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01548.x

- Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14(2 pt 2):331–334. pmid:3950133

- Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34(7):680–683. pmid:7670790

- Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2006; 35(1):72–74. doi:10.1080/03009740500228073

- Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(2):456–458. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.040

- Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(9):1835–1837. pmid:8792709

- Potts JR. Pancreatic-portal vein fistula with disseminated fat necrosis treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy. South Med J 1991; 84(5):632–635. pmid:2035087

Fournier gangrene

An 88-year-old man with a 1-day history of fever and altered mental status was transferred to the emergency department. He had been receiving conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer but had no previous cardiovascular or gastrointestinal problems.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was Fournier gangrene. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died 2 hours after admission.

FOURNIER GANGRENE: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS OF THE PERINEUM

Fournier gangrene is a rare but rapidly progressive necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum with a high death rate.

Predisposing factors for Fournier gangrene include older age, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disorders, chronic alcoholism, long-term corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.1,2 Urethral obstruction, instrumentation, urinary extravasation, and trauma have also been associated with this condition.3

In general, organisms from the urinary tract spread along the fascial planes to involve the penis and scrotum.

The differential diagnosis of Fournier gangrene includes scrotal and perineal disorders, as well as intra-abdominal disorders such as cellulitis, abscess, strangulated hernia, pyoderma gangrenosum, allergic vasculitis, vascular occlusion syndromes, and warfarin necrosis.

Delay in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene leads to an extremely high death rate due to rapid progression of the disease, leading to sepsis, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement reduce morbidity and control the infection. Antibiotics for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered if there is a history of or risk factors for this organism.4

Necrotizing fasciitis, including Fournier gangrene, is a common indication for intravenous immunoglobulin, and this treatment has been reported to be effective in a few cases. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of this treatment was terminated early due to slow patient recruitment.5

A delay of even a few hours from suspicion of Fournier gangrene to surgical debridement significantly increases the risk of death.6 Thus, when it is suspected, immediate surgical intervention may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to treat it. The usual combination of antibiotic therapy for Fournier gangrene includes penicillin for the streptococcal species, a third-generation cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside for the gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria.

- Wang YK, Li YH, Wu ST, Meng E. Fournier’s gangrene. QJM 2017; 110(10):671–672. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx124

- Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg 2006; 30(9):1750–1754. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3

- Paonam SS, Bag S. Fournier gangrene with extensive necrosis of urethra and bladder mucosa: a rare occurrence in a patient with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Ann 2015; 7(4):507–509. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.157975

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of soft tissue and muscle infections. Int J Surg 2008; 6(4):328–338. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.07.001

- Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, Padberg W, Wolff M, Henrich M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—a case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):260–263. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.017

- Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier's gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016; 88(3):157–164. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157

An 88-year-old man with a 1-day history of fever and altered mental status was transferred to the emergency department. He had been receiving conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer but had no previous cardiovascular or gastrointestinal problems.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was Fournier gangrene. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died 2 hours after admission.

FOURNIER GANGRENE: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS OF THE PERINEUM

Fournier gangrene is a rare but rapidly progressive necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum with a high death rate.

Predisposing factors for Fournier gangrene include older age, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disorders, chronic alcoholism, long-term corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.1,2 Urethral obstruction, instrumentation, urinary extravasation, and trauma have also been associated with this condition.3

In general, organisms from the urinary tract spread along the fascial planes to involve the penis and scrotum.

The differential diagnosis of Fournier gangrene includes scrotal and perineal disorders, as well as intra-abdominal disorders such as cellulitis, abscess, strangulated hernia, pyoderma gangrenosum, allergic vasculitis, vascular occlusion syndromes, and warfarin necrosis.

Delay in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene leads to an extremely high death rate due to rapid progression of the disease, leading to sepsis, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement reduce morbidity and control the infection. Antibiotics for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered if there is a history of or risk factors for this organism.4

Necrotizing fasciitis, including Fournier gangrene, is a common indication for intravenous immunoglobulin, and this treatment has been reported to be effective in a few cases. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of this treatment was terminated early due to slow patient recruitment.5

A delay of even a few hours from suspicion of Fournier gangrene to surgical debridement significantly increases the risk of death.6 Thus, when it is suspected, immediate surgical intervention may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to treat it. The usual combination of antibiotic therapy for Fournier gangrene includes penicillin for the streptococcal species, a third-generation cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside for the gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria.

An 88-year-old man with a 1-day history of fever and altered mental status was transferred to the emergency department. He had been receiving conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer but had no previous cardiovascular or gastrointestinal problems.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was Fournier gangrene. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died 2 hours after admission.

FOURNIER GANGRENE: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS OF THE PERINEUM

Fournier gangrene is a rare but rapidly progressive necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum with a high death rate.

Predisposing factors for Fournier gangrene include older age, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disorders, chronic alcoholism, long-term corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.1,2 Urethral obstruction, instrumentation, urinary extravasation, and trauma have also been associated with this condition.3

In general, organisms from the urinary tract spread along the fascial planes to involve the penis and scrotum.

The differential diagnosis of Fournier gangrene includes scrotal and perineal disorders, as well as intra-abdominal disorders such as cellulitis, abscess, strangulated hernia, pyoderma gangrenosum, allergic vasculitis, vascular occlusion syndromes, and warfarin necrosis.

Delay in the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene leads to an extremely high death rate due to rapid progression of the disease, leading to sepsis, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and extensive surgical debridement reduce morbidity and control the infection. Antibiotics for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be considered if there is a history of or risk factors for this organism.4

Necrotizing fasciitis, including Fournier gangrene, is a common indication for intravenous immunoglobulin, and this treatment has been reported to be effective in a few cases. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of this treatment was terminated early due to slow patient recruitment.5

A delay of even a few hours from suspicion of Fournier gangrene to surgical debridement significantly increases the risk of death.6 Thus, when it is suspected, immediate surgical intervention may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to treat it. The usual combination of antibiotic therapy for Fournier gangrene includes penicillin for the streptococcal species, a third-generation cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside for the gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria.

- Wang YK, Li YH, Wu ST, Meng E. Fournier’s gangrene. QJM 2017; 110(10):671–672. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx124

- Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg 2006; 30(9):1750–1754. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3

- Paonam SS, Bag S. Fournier gangrene with extensive necrosis of urethra and bladder mucosa: a rare occurrence in a patient with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Ann 2015; 7(4):507–509. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.157975

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of soft tissue and muscle infections. Int J Surg 2008; 6(4):328–338. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.07.001

- Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, Padberg W, Wolff M, Henrich M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—a case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):260–263. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.017

- Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier's gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016; 88(3):157–164. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157

- Wang YK, Li YH, Wu ST, Meng E. Fournier’s gangrene. QJM 2017; 110(10):671–672. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx124

- Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg 2006; 30(9):1750–1754. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3

- Paonam SS, Bag S. Fournier gangrene with extensive necrosis of urethra and bladder mucosa: a rare occurrence in a patient with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Ann 2015; 7(4):507–509. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.157975

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of soft tissue and muscle infections. Int J Surg 2008; 6(4):328–338. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.07.001

- Koch C, Hecker A, Grau V, Padberg W, Wolff M, Henrich M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in necrotizing fasciitis—a case report and review of recent literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):260–263. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.017

- Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier's gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016; 88(3):157–164. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157

Brain abscesses in a 60-year-old man

A 60-year-old man with hypertension and persistent atrial fibrillation refractory to radiofrequency ablation was brought to the hospital in status epilepticus requiring intubation. His wife said that during the past month he had experienced a number of episodic seizures, but due to his busy work schedule he had not sought medical attention. He had also been hospitalized 3 times during the past week for chills, tremors, and fevers with temperatures up to 101°F (38.3°C), and his symptoms had been ascribed to the amiodarone he had been taking for the past 11 days for atrial fibrillation. The amiodarone dose had been decreased to half a tablet after the first 7 days, but his symptoms had continued.

When the patient was able to speak, he denied intravenous drug abuse and claimed to be up to date with vaccinations. Colonoscopy 10 years earlier had been negative. He has no pets, but says that there are stray cats around his home and that he has had contact with cat feces while gardening. He works as a diesel mechanic and is exposed to motor oil and diesel fuel, but denies any direct exposure to carcinogenic chemicals.

On admission, his temperature was 37.7°C (99.9°F), blood pressure 92/69 mm Hg, heart rate 96 beats per minute, respiratory rate 21 per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air and 100% on oxygen at 2 L per minute.

Decerebrate posturing and forced left visual gaze deviation was observed. Oral examination revealed severe decay of multiple teeth, with some teeth broken down to the level of the gingiva, and moderate generalized periodontal disease with heavy plaque and calculi in the gingiva.

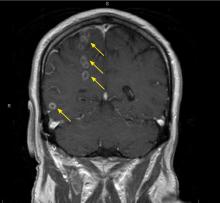

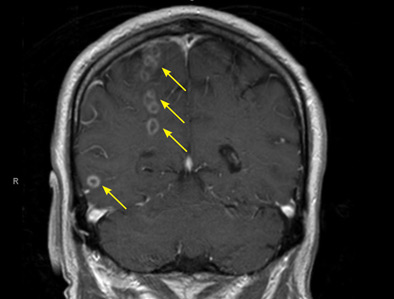

The differential diagnosis for intracranial ring-enhancing lesions includes metastasis, abscess, infection in an immunocompromised state (eg, toxoplasmosis), glioblastoma, subacute infarct, neurocysticercosis, lymphoma, demyelination, and resolving hematoma. In our patient, further testing to narrow the differential included lumbar puncture, with results within normal limits, and transthoracic echocardiography, which was negative for endocarditis. A biopsy obtained by craniotomy confirmed the diagnosis of abscess surrounded by reactive glioses.

During his hospitalization, the patient’s antiseizure regimen was lorazepam 1 to 2 mg as needed, levetiracetam 1,500 mg twice daily, and fosphenytoin infusion at 100 mg phenytoin sodium equivalents per minute. Initial antibiotic therapy included ampicillin 2 g intravenously (IV) 4 times daily.

Because of persistent nocturnal fevers with temperatures ranging from 37.8°C (100°F) to 41.2°C (106.2°F), antibiotic coverage was broadened to meropenem 2 g IV every 8 hours. Testing for Toxoplasma gondii, human immunodeficiency virus, and JC polyomavirus was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid culture and abscess cultures were also negative. Blood cultures were eventually positive for Peptostreptococcus micros and Streptococcus constellatus. Based on review of culture results, antibiotic therapy was switched to ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg IV 3 times daily.

For the dental infection, the patient underwent surgical irrigation and debridement with full dental extraction for multiple dental abscesses.

His regimen for seizure control was changed to phenytoin and valproic acid, and he was discharged in stable condition on the following drug regimen: ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily, metronidazole 500 mg IV 3 times daily for 6 weeks, levetiracetam 1,500 mg twice daily, and valproic acid 750 mg 3 times daily.

At a 3-month follow-up visit, he reported no seizure-like activity but demonstrated persistent neurologic deficits (dysdiadochokinesia and mild ataxia).

A LESS COMMON CAUSE OF BRAIN ABSCESS

In the United States, 1,500 to 2,000 cases of brain abscess are diagnosed every year, and this condition is responsible for an estimated 1 in 10,000 hospitalizations. Most patients hospitalized are men over age 60 or children. Most patients with hematogenous or embolic spread of infection from a primary infection source are immunocompromised.

However, the lesions in our patient were not from compromised immunity, but rather from septic hematogenous spread of an odontogenic infection. Odontogenic bacteria are a common cause of pyogenic orofascial infection, including periapical abscess and infection of adjoining fascial spaces of the head and neck.1

P micros and S constellatus have been commonly found in many types of odontogenic infection, including dentoalveolar infection, periodontitis, and pericoronitis.2 Our patient was found to have several periodontal abscesses with bacteremia and spread to the brain. Although transthoracic echocardiography was negative for vegetations or patent foramen ovale, the quality and location of the brain abscesses suggested embolic spread of infection. Most of the suspected septic emboli were in the right hemisphere, consistent with patterns seen with cardioembolic phenomena, and a number of lesions appeared to be within the distribution of the right anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery.

EMPIRIC AND SPECIFIC THERAPIES

Empiric antibiotic therapy for local odontogenic infection includes amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and metronidazole.1 Our patient’s treatment with ceftriaxone and metronidazole was based on the species and sensitivities of the bacteria in blood cultures.

Surgical irrigation with debridement is considered first-line therapy for local dental infection, with antimicrobials as adjunctive therapy. Initiation of antibiotic therapy before surgery has been associated with a shortened duration of infection and a reduced risk of bacteremia.3

First-line therapy for cerebral abscess is typically antibiotics, specifically ceftriaxone and metronidazole as in our patient. Ceftriaxone is selected for coverage against streptococci, enterobacteriacae, and most common anaerobes, whereas metronidazole is chosen for its efficacy against Bacteroides fragilis.

Computed tomography-guided stereotactic aspiration and open drainage are viable options for solitary and surgically accessible abscesses—typically those greater than 2 cm. Our patient had multiple small septic emboli in the right hemisphere, with the largest lesion measuring 1.5 cm, thus limiting the effectiveness of surgical intervention.

Some patients with mass effect or other evidence of increased intracranial pressure may benefit from high doses of a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone. However, since our patient had no clinical or diagnostic findings suggesting elevated intracranial pressure, we opted for nonsurgical management of the brain abscesses, with 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, an antiseizure regimen, and plans for repeat imaging in the outpatient setting.

- Bahl R, Sandhu S, Singh K, Sahai N, Gupta M. Odontogenic infections: microbiology and management. Contemp Clin Dent 2014; 5(3):307–311. doi:10.4103/0976-237X.137921

- Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S. Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive cocci isolated from pus specimens of orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2002; 17(2):132–135. pmid:11929563

- Peedikayil FC. Antibiotics in odontogenic infections—an update. J Antimicro 2016; 2:(2)117. doi:10.4172/2472-1212.1000117

A 60-year-old man with hypertension and persistent atrial fibrillation refractory to radiofrequency ablation was brought to the hospital in status epilepticus requiring intubation. His wife said that during the past month he had experienced a number of episodic seizures, but due to his busy work schedule he had not sought medical attention. He had also been hospitalized 3 times during the past week for chills, tremors, and fevers with temperatures up to 101°F (38.3°C), and his symptoms had been ascribed to the amiodarone he had been taking for the past 11 days for atrial fibrillation. The amiodarone dose had been decreased to half a tablet after the first 7 days, but his symptoms had continued.

When the patient was able to speak, he denied intravenous drug abuse and claimed to be up to date with vaccinations. Colonoscopy 10 years earlier had been negative. He has no pets, but says that there are stray cats around his home and that he has had contact with cat feces while gardening. He works as a diesel mechanic and is exposed to motor oil and diesel fuel, but denies any direct exposure to carcinogenic chemicals.

On admission, his temperature was 37.7°C (99.9°F), blood pressure 92/69 mm Hg, heart rate 96 beats per minute, respiratory rate 21 per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air and 100% on oxygen at 2 L per minute.

Decerebrate posturing and forced left visual gaze deviation was observed. Oral examination revealed severe decay of multiple teeth, with some teeth broken down to the level of the gingiva, and moderate generalized periodontal disease with heavy plaque and calculi in the gingiva.

The differential diagnosis for intracranial ring-enhancing lesions includes metastasis, abscess, infection in an immunocompromised state (eg, toxoplasmosis), glioblastoma, subacute infarct, neurocysticercosis, lymphoma, demyelination, and resolving hematoma. In our patient, further testing to narrow the differential included lumbar puncture, with results within normal limits, and transthoracic echocardiography, which was negative for endocarditis. A biopsy obtained by craniotomy confirmed the diagnosis of abscess surrounded by reactive glioses.

During his hospitalization, the patient’s antiseizure regimen was lorazepam 1 to 2 mg as needed, levetiracetam 1,500 mg twice daily, and fosphenytoin infusion at 100 mg phenytoin sodium equivalents per minute. Initial antibiotic therapy included ampicillin 2 g intravenously (IV) 4 times daily.

Because of persistent nocturnal fevers with temperatures ranging from 37.8°C (100°F) to 41.2°C (106.2°F), antibiotic coverage was broadened to meropenem 2 g IV every 8 hours. Testing for Toxoplasma gondii, human immunodeficiency virus, and JC polyomavirus was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid culture and abscess cultures were also negative. Blood cultures were eventually positive for Peptostreptococcus micros and Streptococcus constellatus. Based on review of culture results, antibiotic therapy was switched to ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg IV 3 times daily.

For the dental infection, the patient underwent surgical irrigation and debridement with full dental extraction for multiple dental abscesses.

His regimen for seizure control was changed to phenytoin and valproic acid, and he was discharged in stable condition on the following drug regimen: ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily, metronidazole 500 mg IV 3 times daily for 6 weeks, levetiracetam 1,500 mg twice daily, and valproic acid 750 mg 3 times daily.

At a 3-month follow-up visit, he reported no seizure-like activity but demonstrated persistent neurologic deficits (dysdiadochokinesia and mild ataxia).

A LESS COMMON CAUSE OF BRAIN ABSCESS

In the United States, 1,500 to 2,000 cases of brain abscess are diagnosed every year, and this condition is responsible for an estimated 1 in 10,000 hospitalizations. Most patients hospitalized are men over age 60 or children. Most patients with hematogenous or embolic spread of infection from a primary infection source are immunocompromised.

However, the lesions in our patient were not from compromised immunity, but rather from septic hematogenous spread of an odontogenic infection. Odontogenic bacteria are a common cause of pyogenic orofascial infection, including periapical abscess and infection of adjoining fascial spaces of the head and neck.1

P micros and S constellatus have been commonly found in many types of odontogenic infection, including dentoalveolar infection, periodontitis, and pericoronitis.2 Our patient was found to have several periodontal abscesses with bacteremia and spread to the brain. Although transthoracic echocardiography was negative for vegetations or patent foramen ovale, the quality and location of the brain abscesses suggested embolic spread of infection. Most of the suspected septic emboli were in the right hemisphere, consistent with patterns seen with cardioembolic phenomena, and a number of lesions appeared to be within the distribution of the right anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery.

EMPIRIC AND SPECIFIC THERAPIES

Empiric antibiotic therapy for local odontogenic infection includes amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and metronidazole.1 Our patient’s treatment with ceftriaxone and metronidazole was based on the species and sensitivities of the bacteria in blood cultures.

Surgical irrigation with debridement is considered first-line therapy for local dental infection, with antimicrobials as adjunctive therapy. Initiation of antibiotic therapy before surgery has been associated with a shortened duration of infection and a reduced risk of bacteremia.3

First-line therapy for cerebral abscess is typically antibiotics, specifically ceftriaxone and metronidazole as in our patient. Ceftriaxone is selected for coverage against streptococci, enterobacteriacae, and most common anaerobes, whereas metronidazole is chosen for its efficacy against Bacteroides fragilis.

Computed tomography-guided stereotactic aspiration and open drainage are viable options for solitary and surgically accessible abscesses—typically those greater than 2 cm. Our patient had multiple small septic emboli in the right hemisphere, with the largest lesion measuring 1.5 cm, thus limiting the effectiveness of surgical intervention.

Some patients with mass effect or other evidence of increased intracranial pressure may benefit from high doses of a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone. However, since our patient had no clinical or diagnostic findings suggesting elevated intracranial pressure, we opted for nonsurgical management of the brain abscesses, with 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, an antiseizure regimen, and plans for repeat imaging in the outpatient setting.

A 60-year-old man with hypertension and persistent atrial fibrillation refractory to radiofrequency ablation was brought to the hospital in status epilepticus requiring intubation. His wife said that during the past month he had experienced a number of episodic seizures, but due to his busy work schedule he had not sought medical attention. He had also been hospitalized 3 times during the past week for chills, tremors, and fevers with temperatures up to 101°F (38.3°C), and his symptoms had been ascribed to the amiodarone he had been taking for the past 11 days for atrial fibrillation. The amiodarone dose had been decreased to half a tablet after the first 7 days, but his symptoms had continued.

When the patient was able to speak, he denied intravenous drug abuse and claimed to be up to date with vaccinations. Colonoscopy 10 years earlier had been negative. He has no pets, but says that there are stray cats around his home and that he has had contact with cat feces while gardening. He works as a diesel mechanic and is exposed to motor oil and diesel fuel, but denies any direct exposure to carcinogenic chemicals.

On admission, his temperature was 37.7°C (99.9°F), blood pressure 92/69 mm Hg, heart rate 96 beats per minute, respiratory rate 21 per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air and 100% on oxygen at 2 L per minute.

Decerebrate posturing and forced left visual gaze deviation was observed. Oral examination revealed severe decay of multiple teeth, with some teeth broken down to the level of the gingiva, and moderate generalized periodontal disease with heavy plaque and calculi in the gingiva.

The differential diagnosis for intracranial ring-enhancing lesions includes metastasis, abscess, infection in an immunocompromised state (eg, toxoplasmosis), glioblastoma, subacute infarct, neurocysticercosis, lymphoma, demyelination, and resolving hematoma. In our patient, further testing to narrow the differential included lumbar puncture, with results within normal limits, and transthoracic echocardiography, which was negative for endocarditis. A biopsy obtained by craniotomy confirmed the diagnosis of abscess surrounded by reactive glioses.

During his hospitalization, the patient’s antiseizure regimen was lorazepam 1 to 2 mg as needed, levetiracetam 1,500 mg twice daily, and fosphenytoin infusion at 100 mg phenytoin sodium equivalents per minute. Initial antibiotic therapy included ampicillin 2 g intravenously (IV) 4 times daily.

Because of persistent nocturnal fevers with temperatures ranging from 37.8°C (100°F) to 41.2°C (106.2°F), antibiotic coverage was broadened to meropenem 2 g IV every 8 hours. Testing for Toxoplasma gondii, human immunodeficiency virus, and JC polyomavirus was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid culture and abscess cultures were also negative. Blood cultures were eventually positive for Peptostreptococcus micros and Streptococcus constellatus. Based on review of culture results, antibiotic therapy was switched to ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg IV 3 times daily.

For the dental infection, the patient underwent surgical irrigation and debridement with full dental extraction for multiple dental abscesses.

His regimen for seizure control was changed to phenytoin and valproic acid, and he was discharged in stable condition on the following drug regimen: ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily, metronidazole 500 mg IV 3 times daily for 6 weeks, levetiracetam 1,500 mg twice daily, and valproic acid 750 mg 3 times daily.

At a 3-month follow-up visit, he reported no seizure-like activity but demonstrated persistent neurologic deficits (dysdiadochokinesia and mild ataxia).

A LESS COMMON CAUSE OF BRAIN ABSCESS

In the United States, 1,500 to 2,000 cases of brain abscess are diagnosed every year, and this condition is responsible for an estimated 1 in 10,000 hospitalizations. Most patients hospitalized are men over age 60 or children. Most patients with hematogenous or embolic spread of infection from a primary infection source are immunocompromised.

However, the lesions in our patient were not from compromised immunity, but rather from septic hematogenous spread of an odontogenic infection. Odontogenic bacteria are a common cause of pyogenic orofascial infection, including periapical abscess and infection of adjoining fascial spaces of the head and neck.1

P micros and S constellatus have been commonly found in many types of odontogenic infection, including dentoalveolar infection, periodontitis, and pericoronitis.2 Our patient was found to have several periodontal abscesses with bacteremia and spread to the brain. Although transthoracic echocardiography was negative for vegetations or patent foramen ovale, the quality and location of the brain abscesses suggested embolic spread of infection. Most of the suspected septic emboli were in the right hemisphere, consistent with patterns seen with cardioembolic phenomena, and a number of lesions appeared to be within the distribution of the right anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery.

EMPIRIC AND SPECIFIC THERAPIES

Empiric antibiotic therapy for local odontogenic infection includes amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and metronidazole.1 Our patient’s treatment with ceftriaxone and metronidazole was based on the species and sensitivities of the bacteria in blood cultures.

Surgical irrigation with debridement is considered first-line therapy for local dental infection, with antimicrobials as adjunctive therapy. Initiation of antibiotic therapy before surgery has been associated with a shortened duration of infection and a reduced risk of bacteremia.3

First-line therapy for cerebral abscess is typically antibiotics, specifically ceftriaxone and metronidazole as in our patient. Ceftriaxone is selected for coverage against streptococci, enterobacteriacae, and most common anaerobes, whereas metronidazole is chosen for its efficacy against Bacteroides fragilis.

Computed tomography-guided stereotactic aspiration and open drainage are viable options for solitary and surgically accessible abscesses—typically those greater than 2 cm. Our patient had multiple small septic emboli in the right hemisphere, with the largest lesion measuring 1.5 cm, thus limiting the effectiveness of surgical intervention.

Some patients with mass effect or other evidence of increased intracranial pressure may benefit from high doses of a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone. However, since our patient had no clinical or diagnostic findings suggesting elevated intracranial pressure, we opted for nonsurgical management of the brain abscesses, with 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, an antiseizure regimen, and plans for repeat imaging in the outpatient setting.

- Bahl R, Sandhu S, Singh K, Sahai N, Gupta M. Odontogenic infections: microbiology and management. Contemp Clin Dent 2014; 5(3):307–311. doi:10.4103/0976-237X.137921

- Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S. Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive cocci isolated from pus specimens of orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2002; 17(2):132–135. pmid:11929563

- Peedikayil FC. Antibiotics in odontogenic infections—an update. J Antimicro 2016; 2:(2)117. doi:10.4172/2472-1212.1000117

- Bahl R, Sandhu S, Singh K, Sahai N, Gupta M. Odontogenic infections: microbiology and management. Contemp Clin Dent 2014; 5(3):307–311. doi:10.4103/0976-237X.137921

- Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S. Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive cocci isolated from pus specimens of orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2002; 17(2):132–135. pmid:11929563

- Peedikayil FC. Antibiotics in odontogenic infections—an update. J Antimicro 2016; 2:(2)117. doi:10.4172/2472-1212.1000117

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy

A 51-year-old man with end-stage renal disease, on peritoneal dialysis for the past 4 years, presented to the emergency department with severe pain in both legs. The pain had started 2 months previously and had progressively worsened. After multiple admissions in the past for hyperkalemia and volume overload due to noncompliance, he had been advised to switch to hemodialysis.

See related article and editorial

Laboratory analysis revealed the following values:

- Serum creatinine 12.62 mg/dL (reference range 0.73–1.22)

- Blood urea nitrogen 159 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum calcium corrected for serum albumin 8.1 mg/dL (8.4–10.0)

- Serum phosphorus 10.6 mg/dL (2.7–4.8).

His history of end-stage renal disease, failure of peritoneal dialysis, high calcium-phosphorus product (8.1 mg/dL × 10.6 mg/dL = 85.9 mg2/dL2, reference range ≤ 55), and characteristic physical findings led to the diagnosis of calcific uremic arteriolopathy.

CALCIFIC UREMIC ARTERIOLOPATHY

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy or “calciphylaxis,” seen most often in patients with end-stage renal disease, is caused by calcium deposition in the media of the dermo-hypodermic arterioles, leading to infarction of adjacent tissue.1–3 A high calcium-phosphorus product (> 55) has been implicated in its development; however, the calcium-phosphorus product can be normal despite hyperphosphatemia, which itself may promote ectopic calcification.

Early ischemic manifestations include livedo reticularis and painful retiform purpura on the thighs and other areas of high adiposity. Lesions evolve into violaceous plaquelike subcutaneous nodules that can infarct, become necrotic, ulcerate, and become infected. Punch biopsy demonstrating arteriolar calcification, subintimal fibrosis, and thrombosis confirms the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Warfarin necrosis can cause large, irregular, bloody bullae that ulcerate and turn into eschar that may resemble lesions of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Our patient, however, had no exposure to warfarin.

Pemphigus foliaceus, an immunoglobulin G4-mediated autoimmune disorder targeted against desmoglein-1, leads to the formation of fragile blisters that easily rupture when rubbed (Nikolsky sign). Lesions evolve into scaling, crusty erosions on an erythematous base. With tender blisters and lack of mucous membrane involvement, pemphigus foliaceus shares similarities with calcific uremic arteriolopathy, but the presence of necrotic eschar surrounded by violaceous plaques in our patient made it an unlikely diagnosis.

Cryofibrinogenemia. In the right clinical scenario, ie, in a patient with vasculitis, malignancy, infection, cryoglobulinemia, or collagen diseases, cryofibrinogen-mediated cold-induced occlusive lesions may mimic calcific uremic arteriolopathy, with painful or pruritic erythema, purpura, livedo reticularis, necrosis, and ulceration.4 Our patient had no color changes with exposure to cold, nor any history of Raynaud phenomenon or joint pain, making the diagnosis of cryofibrinogenemia less likely.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Gadolinium contrast medium in magnetic resonance imaging can cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, characterized by erythematous papules that coalesce into brawny plaques with surrounding woody induration, which may resemble lesions of calcific uremic arteriolopathy.5 However, our patient had not been exposed to gadolinium.

Management

Management is multidisciplinary and includes the following1:

- Hemodialysis, modified to optimize calcium balance2

- Intravenous sodium thiosulfate: the exact mechanism of action remains unclear, but it is thought to play a role in chelating calcium from tissue deposits, thus decreasing pain and promoting regression of skin lesions3

- Wound care, including chemical debridement agents, negative-pressure wound therapy, and surgical debridement for infected wounds6

- Pain management with opioid analgesics.

The patient was treated with all these measures. However, he died of sudden cardiac arrest during the same admission.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56(4):569–579. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66(1):133–146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, MacDonald AS. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 35(4):588–597. pmid:10739777

- Michaud M, Pourrat J. Cryofibrinogenemia. J Clin Rheumatol 2013; 19(3):142–148. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e318289e06e

- Galan A, Cowper SE, Bucala R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy). Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006; 18(6):614–617. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000245725.94887.8d

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003:558–562.

A 51-year-old man with end-stage renal disease, on peritoneal dialysis for the past 4 years, presented to the emergency department with severe pain in both legs. The pain had started 2 months previously and had progressively worsened. After multiple admissions in the past for hyperkalemia and volume overload due to noncompliance, he had been advised to switch to hemodialysis.

See related article and editorial

Laboratory analysis revealed the following values:

- Serum creatinine 12.62 mg/dL (reference range 0.73–1.22)

- Blood urea nitrogen 159 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum calcium corrected for serum albumin 8.1 mg/dL (8.4–10.0)

- Serum phosphorus 10.6 mg/dL (2.7–4.8).

His history of end-stage renal disease, failure of peritoneal dialysis, high calcium-phosphorus product (8.1 mg/dL × 10.6 mg/dL = 85.9 mg2/dL2, reference range ≤ 55), and characteristic physical findings led to the diagnosis of calcific uremic arteriolopathy.

CALCIFIC UREMIC ARTERIOLOPATHY

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy or “calciphylaxis,” seen most often in patients with end-stage renal disease, is caused by calcium deposition in the media of the dermo-hypodermic arterioles, leading to infarction of adjacent tissue.1–3 A high calcium-phosphorus product (> 55) has been implicated in its development; however, the calcium-phosphorus product can be normal despite hyperphosphatemia, which itself may promote ectopic calcification.

Early ischemic manifestations include livedo reticularis and painful retiform purpura on the thighs and other areas of high adiposity. Lesions evolve into violaceous plaquelike subcutaneous nodules that can infarct, become necrotic, ulcerate, and become infected. Punch biopsy demonstrating arteriolar calcification, subintimal fibrosis, and thrombosis confirms the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Warfarin necrosis can cause large, irregular, bloody bullae that ulcerate and turn into eschar that may resemble lesions of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Our patient, however, had no exposure to warfarin.

Pemphigus foliaceus, an immunoglobulin G4-mediated autoimmune disorder targeted against desmoglein-1, leads to the formation of fragile blisters that easily rupture when rubbed (Nikolsky sign). Lesions evolve into scaling, crusty erosions on an erythematous base. With tender blisters and lack of mucous membrane involvement, pemphigus foliaceus shares similarities with calcific uremic arteriolopathy, but the presence of necrotic eschar surrounded by violaceous plaques in our patient made it an unlikely diagnosis.

Cryofibrinogenemia. In the right clinical scenario, ie, in a patient with vasculitis, malignancy, infection, cryoglobulinemia, or collagen diseases, cryofibrinogen-mediated cold-induced occlusive lesions may mimic calcific uremic arteriolopathy, with painful or pruritic erythema, purpura, livedo reticularis, necrosis, and ulceration.4 Our patient had no color changes with exposure to cold, nor any history of Raynaud phenomenon or joint pain, making the diagnosis of cryofibrinogenemia less likely.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Gadolinium contrast medium in magnetic resonance imaging can cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, characterized by erythematous papules that coalesce into brawny plaques with surrounding woody induration, which may resemble lesions of calcific uremic arteriolopathy.5 However, our patient had not been exposed to gadolinium.

Management

Management is multidisciplinary and includes the following1:

- Hemodialysis, modified to optimize calcium balance2

- Intravenous sodium thiosulfate: the exact mechanism of action remains unclear, but it is thought to play a role in chelating calcium from tissue deposits, thus decreasing pain and promoting regression of skin lesions3

- Wound care, including chemical debridement agents, negative-pressure wound therapy, and surgical debridement for infected wounds6

- Pain management with opioid analgesics.

The patient was treated with all these measures. However, he died of sudden cardiac arrest during the same admission.

A 51-year-old man with end-stage renal disease, on peritoneal dialysis for the past 4 years, presented to the emergency department with severe pain in both legs. The pain had started 2 months previously and had progressively worsened. After multiple admissions in the past for hyperkalemia and volume overload due to noncompliance, he had been advised to switch to hemodialysis.

See related article and editorial

Laboratory analysis revealed the following values:

- Serum creatinine 12.62 mg/dL (reference range 0.73–1.22)

- Blood urea nitrogen 159 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum calcium corrected for serum albumin 8.1 mg/dL (8.4–10.0)

- Serum phosphorus 10.6 mg/dL (2.7–4.8).

His history of end-stage renal disease, failure of peritoneal dialysis, high calcium-phosphorus product (8.1 mg/dL × 10.6 mg/dL = 85.9 mg2/dL2, reference range ≤ 55), and characteristic physical findings led to the diagnosis of calcific uremic arteriolopathy.

CALCIFIC UREMIC ARTERIOLOPATHY

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy or “calciphylaxis,” seen most often in patients with end-stage renal disease, is caused by calcium deposition in the media of the dermo-hypodermic arterioles, leading to infarction of adjacent tissue.1–3 A high calcium-phosphorus product (> 55) has been implicated in its development; however, the calcium-phosphorus product can be normal despite hyperphosphatemia, which itself may promote ectopic calcification.

Early ischemic manifestations include livedo reticularis and painful retiform purpura on the thighs and other areas of high adiposity. Lesions evolve into violaceous plaquelike subcutaneous nodules that can infarct, become necrotic, ulcerate, and become infected. Punch biopsy demonstrating arteriolar calcification, subintimal fibrosis, and thrombosis confirms the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Warfarin necrosis can cause large, irregular, bloody bullae that ulcerate and turn into eschar that may resemble lesions of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Our patient, however, had no exposure to warfarin.

Pemphigus foliaceus, an immunoglobulin G4-mediated autoimmune disorder targeted against desmoglein-1, leads to the formation of fragile blisters that easily rupture when rubbed (Nikolsky sign). Lesions evolve into scaling, crusty erosions on an erythematous base. With tender blisters and lack of mucous membrane involvement, pemphigus foliaceus shares similarities with calcific uremic arteriolopathy, but the presence of necrotic eschar surrounded by violaceous plaques in our patient made it an unlikely diagnosis.

Cryofibrinogenemia. In the right clinical scenario, ie, in a patient with vasculitis, malignancy, infection, cryoglobulinemia, or collagen diseases, cryofibrinogen-mediated cold-induced occlusive lesions may mimic calcific uremic arteriolopathy, with painful or pruritic erythema, purpura, livedo reticularis, necrosis, and ulceration.4 Our patient had no color changes with exposure to cold, nor any history of Raynaud phenomenon or joint pain, making the diagnosis of cryofibrinogenemia less likely.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Gadolinium contrast medium in magnetic resonance imaging can cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, characterized by erythematous papules that coalesce into brawny plaques with surrounding woody induration, which may resemble lesions of calcific uremic arteriolopathy.5 However, our patient had not been exposed to gadolinium.

Management

Management is multidisciplinary and includes the following1:

- Hemodialysis, modified to optimize calcium balance2

- Intravenous sodium thiosulfate: the exact mechanism of action remains unclear, but it is thought to play a role in chelating calcium from tissue deposits, thus decreasing pain and promoting regression of skin lesions3

- Wound care, including chemical debridement agents, negative-pressure wound therapy, and surgical debridement for infected wounds6

- Pain management with opioid analgesics.

The patient was treated with all these measures. However, he died of sudden cardiac arrest during the same admission.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56(4):569–579. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66(1):133–146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, MacDonald AS. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 35(4):588–597. pmid:10739777

- Michaud M, Pourrat J. Cryofibrinogenemia. J Clin Rheumatol 2013; 19(3):142–148. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e318289e06e

- Galan A, Cowper SE, Bucala R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy). Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006; 18(6):614–617. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000245725.94887.8d

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003:558–562.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56(4):569–579. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66(1):133–146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, MacDonald AS. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 35(4):588–597. pmid:10739777

- Michaud M, Pourrat J. Cryofibrinogenemia. J Clin Rheumatol 2013; 19(3):142–148. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e318289e06e

- Galan A, Cowper SE, Bucala R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy). Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006; 18(6):614–617. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000245725.94887.8d

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003:558–562.

Palmoplantar exanthema and liver dysfunction

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5