User login

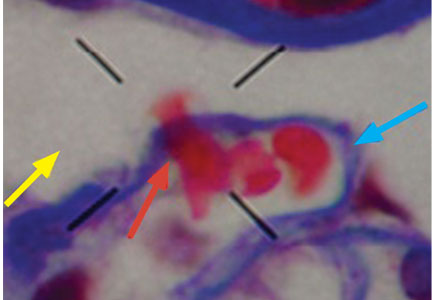

Dysmorphic red blood cell formation

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

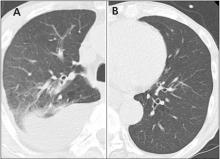

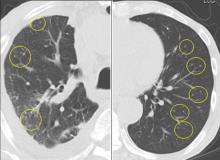

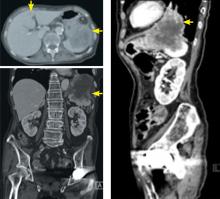

Drug reaction or metastatic lung cancer?

A 76-year-old man with ulcerative colitis presented with a 1-week history of low-grade fever and progressive dyspnea. He was taking infliximab for the ulcerative colitis. He was known to be negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

Since the M tuberculosis cultured from his lung proved to be sensitive to the antituberculosis drugs, we suspected that the nodules were a paradoxical reaction to the drug therapy, and thus we continued the treatment because of the continued low-grade fever. After 9 months of therapy, the fever had resolved and the nodules had disappeared, confirming our suspicion of a paradoxical reaction. The number of lymphocytes gradually increased during drug therapy.

Paradoxical reaction during tuberculosis treatment is defined as a worsening of pre-existing lesions or as the emergence of new lesions during appropriate therapy.1,2 The diagnosis is sometimes difficult, since new lesions can resemble other lung diseases. However, a paradoxical reaction involving randomly distributed nodules is rare and radiographically resembles metastatic lung cancer. Clinicians should be aware of this type of reaction in patients on tuberculosis therapy.

- Cheng SL, Wang HC, Yang PC. Paradoxical response during anti-tuberculosis treatment in HIV-negative patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007; 11:1290–1295.

- Narita M, Ashkin D, Hollender ES, Pitchenik AE. Paradoxical worsening of tuberculosis following antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158:157–161.

A 76-year-old man with ulcerative colitis presented with a 1-week history of low-grade fever and progressive dyspnea. He was taking infliximab for the ulcerative colitis. He was known to be negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

Since the M tuberculosis cultured from his lung proved to be sensitive to the antituberculosis drugs, we suspected that the nodules were a paradoxical reaction to the drug therapy, and thus we continued the treatment because of the continued low-grade fever. After 9 months of therapy, the fever had resolved and the nodules had disappeared, confirming our suspicion of a paradoxical reaction. The number of lymphocytes gradually increased during drug therapy.

Paradoxical reaction during tuberculosis treatment is defined as a worsening of pre-existing lesions or as the emergence of new lesions during appropriate therapy.1,2 The diagnosis is sometimes difficult, since new lesions can resemble other lung diseases. However, a paradoxical reaction involving randomly distributed nodules is rare and radiographically resembles metastatic lung cancer. Clinicians should be aware of this type of reaction in patients on tuberculosis therapy.

A 76-year-old man with ulcerative colitis presented with a 1-week history of low-grade fever and progressive dyspnea. He was taking infliximab for the ulcerative colitis. He was known to be negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

Since the M tuberculosis cultured from his lung proved to be sensitive to the antituberculosis drugs, we suspected that the nodules were a paradoxical reaction to the drug therapy, and thus we continued the treatment because of the continued low-grade fever. After 9 months of therapy, the fever had resolved and the nodules had disappeared, confirming our suspicion of a paradoxical reaction. The number of lymphocytes gradually increased during drug therapy.

Paradoxical reaction during tuberculosis treatment is defined as a worsening of pre-existing lesions or as the emergence of new lesions during appropriate therapy.1,2 The diagnosis is sometimes difficult, since new lesions can resemble other lung diseases. However, a paradoxical reaction involving randomly distributed nodules is rare and radiographically resembles metastatic lung cancer. Clinicians should be aware of this type of reaction in patients on tuberculosis therapy.

- Cheng SL, Wang HC, Yang PC. Paradoxical response during anti-tuberculosis treatment in HIV-negative patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007; 11:1290–1295.

- Narita M, Ashkin D, Hollender ES, Pitchenik AE. Paradoxical worsening of tuberculosis following antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158:157–161.

- Cheng SL, Wang HC, Yang PC. Paradoxical response during anti-tuberculosis treatment in HIV-negative patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007; 11:1290–1295.

- Narita M, Ashkin D, Hollender ES, Pitchenik AE. Paradoxical worsening of tuberculosis following antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158:157–161.

The Leser-Trélat sign

An 85-year-old woman presented with night sweats, dry cough, and an unintended 30-pound weight loss over the preceding 6 months. She also reported the sudden onset of “itchy moles” on her back.

KERATOSES AND MALIGNANCY

The Leser-Trélat sign is the sudden development of multiple pruritic seborrheic keratoses, often associated with malignancy.1–4 Roughly half of these associated malignancies are adenocarcinomas, most commonly of the stomach, breast, colon, or rectum. However, it can be seen in other malignancies, including lymphoma, leukemia, and squamous cell carcinoma, as in this case.

Eruption of seborrheic keratoses has also been observed with benign neoplasms, pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus infections, and the use of adalimumab, which indicates that the Leser-Trélat sign is not very specific. Despite these concerns, the eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses should continue to trigger the thought of an internal malignancy in the differential diagnosis.

- Ehst BD, Minzer-Conzetti K, Swerdlin A, Devere TS. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. Curr Probl Surg 2010; 47:384–445.

- Schwartz RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35:88–95.

- Ellis DL, Yates RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. Clin Dermatol 1993; 11:141–148.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; 59:73–98.

An 85-year-old woman presented with night sweats, dry cough, and an unintended 30-pound weight loss over the preceding 6 months. She also reported the sudden onset of “itchy moles” on her back.

KERATOSES AND MALIGNANCY

The Leser-Trélat sign is the sudden development of multiple pruritic seborrheic keratoses, often associated with malignancy.1–4 Roughly half of these associated malignancies are adenocarcinomas, most commonly of the stomach, breast, colon, or rectum. However, it can be seen in other malignancies, including lymphoma, leukemia, and squamous cell carcinoma, as in this case.

Eruption of seborrheic keratoses has also been observed with benign neoplasms, pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus infections, and the use of adalimumab, which indicates that the Leser-Trélat sign is not very specific. Despite these concerns, the eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses should continue to trigger the thought of an internal malignancy in the differential diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman presented with night sweats, dry cough, and an unintended 30-pound weight loss over the preceding 6 months. She also reported the sudden onset of “itchy moles” on her back.

KERATOSES AND MALIGNANCY

The Leser-Trélat sign is the sudden development of multiple pruritic seborrheic keratoses, often associated with malignancy.1–4 Roughly half of these associated malignancies are adenocarcinomas, most commonly of the stomach, breast, colon, or rectum. However, it can be seen in other malignancies, including lymphoma, leukemia, and squamous cell carcinoma, as in this case.

Eruption of seborrheic keratoses has also been observed with benign neoplasms, pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus infections, and the use of adalimumab, which indicates that the Leser-Trélat sign is not very specific. Despite these concerns, the eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses should continue to trigger the thought of an internal malignancy in the differential diagnosis.

- Ehst BD, Minzer-Conzetti K, Swerdlin A, Devere TS. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. Curr Probl Surg 2010; 47:384–445.

- Schwartz RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35:88–95.

- Ellis DL, Yates RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. Clin Dermatol 1993; 11:141–148.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; 59:73–98.

- Ehst BD, Minzer-Conzetti K, Swerdlin A, Devere TS. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. Curr Probl Surg 2010; 47:384–445.

- Schwartz RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35:88–95.

- Ellis DL, Yates RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. Clin Dermatol 1993; 11:141–148.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; 59:73–98.

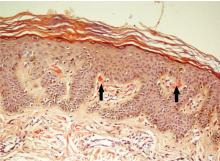

Scapular rash and endocrine neoplasia

A woman in her 30s presented with an itchy skin-colored rash over her left scapular region that had first appeared 8 years earlier. It had started as itchy skin-colored papules that coalesced to a patch and later became hyperpigmented because of repeated scratching.

She had undergone total thyroidectomy for medullary thyroid carcinoma 1 year ago, and the rash had been diagnosed at that time as lichen planus. She was referred to us by her physician for histopathologic confirmation of the lesions. She denied any history of episodic headache or palpitation.

Her urine normetanephrine excretion was elevated at 1,425 μg/day (reference range 148–560), and her metanephrine excretion was also high at 2,024 μg/day (reference range 44–261).

At a 3-month follow-up visit, the woman’s skin lesions had improved with twice-a-day application of mometasone 0.1% cream; she was lost to follow-up after that visit.

MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA

Our patient’s scapular lesions and first-degree family history of MEN type 2A confirmed the diagnosis of the newly recognized variant, MEN type 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, in which the characteristic pigmented scapular rash typically predates the first diagnosis of neoplasia.1 The dermal amyloidosis is caused by deposition of keratinlike peptides rather than calcitoninlike peptides.2

A recent systematic review on MEN type 2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis showed a female preponderance and a high penetrance of cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, which was the second most frequent manifestation of the syndrome, preceded only by medullary thyroid carcinoma.1

As in our patient’s case, scapular rash and a history of medullary thyroid carcinoma should prompt an investigation for MEN type 2A. These patients should be closely followed for underlying MEN type 2A-related neoplasms.

The mucosal neuromas and skin lipomas seen in MEN type 1 and MEN type 2B are absent in MEN type 2A.3 Cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is the only dermatologic marker for MEN type 2A. Owing to a similar genetic background, cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is also associated with familial medullary thyroid carcinoma, another rare variant of MEN type 2A.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Notalgia paresthetica is a unilateral chronic neuropathic pruritus on the back, mostly located between the shoulders and corresponding to the second and the sixth thoracic nerves. It is mostly attributed to compression of spinal nerves by an abnormality of the thoracic spine.5 In our patient, this was ruled out by the radiologic evaluation.

Before MEN type 2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis was recognized as a variant of MEN type 2A, lesions suggestive of notalgia paresthetica were reported with MEN type 2A.3 The classic infrascapular location, history of painful neck muscle spasms, touch hyperesthesia of the lesions, and absence of amyloid deposits on histopathologic study help to differentiate notalgia paresthetica from cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. However, later phases of notalgia paresthetica may show amyloid deposits on histopathologic study, while detection of a scant amount of amyloid is difficult in the early stages of cutaneous lichen amyloidosis.

TAKE-HOME POINT

Cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is usually seen on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It is considered benign, caused by filamentous degeneration of keratinocytes from repeated scratching. But cutaneous lichen amyloidosis at an early age in the scapular area of women warrants a detailed family history for endocrine neoplasia, blood pressure monitoring, thyroid palpation, and blood testing for serum calcium, calcitonin, and parathyroid hormone.

- Scapineli JO, Ceolin L, Puñales MK, Dora JM, Maia AL. MEN 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis: report of three kindred and systematic literature review of clinical, biochemical and molecular characteristics. Fam Cancer 2016; 15:625–633.

- Donovan DT, Levy ML, Furst EJ, et al. Familial cutaneous lichen amyloidosis in association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A: a new variant. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1989; 37:147–150.

- Cox NH, Coulson IH. Systemic disease and the skin. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2010:62.24.

- Moline J, Eng C. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: an overview. Genet Med 2011; 13:755–764.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1085–1087.

A woman in her 30s presented with an itchy skin-colored rash over her left scapular region that had first appeared 8 years earlier. It had started as itchy skin-colored papules that coalesced to a patch and later became hyperpigmented because of repeated scratching.

She had undergone total thyroidectomy for medullary thyroid carcinoma 1 year ago, and the rash had been diagnosed at that time as lichen planus. She was referred to us by her physician for histopathologic confirmation of the lesions. She denied any history of episodic headache or palpitation.

Her urine normetanephrine excretion was elevated at 1,425 μg/day (reference range 148–560), and her metanephrine excretion was also high at 2,024 μg/day (reference range 44–261).

At a 3-month follow-up visit, the woman’s skin lesions had improved with twice-a-day application of mometasone 0.1% cream; she was lost to follow-up after that visit.

MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA

Our patient’s scapular lesions and first-degree family history of MEN type 2A confirmed the diagnosis of the newly recognized variant, MEN type 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, in which the characteristic pigmented scapular rash typically predates the first diagnosis of neoplasia.1 The dermal amyloidosis is caused by deposition of keratinlike peptides rather than calcitoninlike peptides.2

A recent systematic review on MEN type 2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis showed a female preponderance and a high penetrance of cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, which was the second most frequent manifestation of the syndrome, preceded only by medullary thyroid carcinoma.1

As in our patient’s case, scapular rash and a history of medullary thyroid carcinoma should prompt an investigation for MEN type 2A. These patients should be closely followed for underlying MEN type 2A-related neoplasms.

The mucosal neuromas and skin lipomas seen in MEN type 1 and MEN type 2B are absent in MEN type 2A.3 Cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is the only dermatologic marker for MEN type 2A. Owing to a similar genetic background, cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is also associated with familial medullary thyroid carcinoma, another rare variant of MEN type 2A.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Notalgia paresthetica is a unilateral chronic neuropathic pruritus on the back, mostly located between the shoulders and corresponding to the second and the sixth thoracic nerves. It is mostly attributed to compression of spinal nerves by an abnormality of the thoracic spine.5 In our patient, this was ruled out by the radiologic evaluation.

Before MEN type 2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis was recognized as a variant of MEN type 2A, lesions suggestive of notalgia paresthetica were reported with MEN type 2A.3 The classic infrascapular location, history of painful neck muscle spasms, touch hyperesthesia of the lesions, and absence of amyloid deposits on histopathologic study help to differentiate notalgia paresthetica from cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. However, later phases of notalgia paresthetica may show amyloid deposits on histopathologic study, while detection of a scant amount of amyloid is difficult in the early stages of cutaneous lichen amyloidosis.

TAKE-HOME POINT

Cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is usually seen on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It is considered benign, caused by filamentous degeneration of keratinocytes from repeated scratching. But cutaneous lichen amyloidosis at an early age in the scapular area of women warrants a detailed family history for endocrine neoplasia, blood pressure monitoring, thyroid palpation, and blood testing for serum calcium, calcitonin, and parathyroid hormone.

A woman in her 30s presented with an itchy skin-colored rash over her left scapular region that had first appeared 8 years earlier. It had started as itchy skin-colored papules that coalesced to a patch and later became hyperpigmented because of repeated scratching.

She had undergone total thyroidectomy for medullary thyroid carcinoma 1 year ago, and the rash had been diagnosed at that time as lichen planus. She was referred to us by her physician for histopathologic confirmation of the lesions. She denied any history of episodic headache or palpitation.

Her urine normetanephrine excretion was elevated at 1,425 μg/day (reference range 148–560), and her metanephrine excretion was also high at 2,024 μg/day (reference range 44–261).

At a 3-month follow-up visit, the woman’s skin lesions had improved with twice-a-day application of mometasone 0.1% cream; she was lost to follow-up after that visit.

MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA

Our patient’s scapular lesions and first-degree family history of MEN type 2A confirmed the diagnosis of the newly recognized variant, MEN type 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, in which the characteristic pigmented scapular rash typically predates the first diagnosis of neoplasia.1 The dermal amyloidosis is caused by deposition of keratinlike peptides rather than calcitoninlike peptides.2

A recent systematic review on MEN type 2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis showed a female preponderance and a high penetrance of cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, which was the second most frequent manifestation of the syndrome, preceded only by medullary thyroid carcinoma.1

As in our patient’s case, scapular rash and a history of medullary thyroid carcinoma should prompt an investigation for MEN type 2A. These patients should be closely followed for underlying MEN type 2A-related neoplasms.

The mucosal neuromas and skin lipomas seen in MEN type 1 and MEN type 2B are absent in MEN type 2A.3 Cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is the only dermatologic marker for MEN type 2A. Owing to a similar genetic background, cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is also associated with familial medullary thyroid carcinoma, another rare variant of MEN type 2A.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Notalgia paresthetica is a unilateral chronic neuropathic pruritus on the back, mostly located between the shoulders and corresponding to the second and the sixth thoracic nerves. It is mostly attributed to compression of spinal nerves by an abnormality of the thoracic spine.5 In our patient, this was ruled out by the radiologic evaluation.

Before MEN type 2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis was recognized as a variant of MEN type 2A, lesions suggestive of notalgia paresthetica were reported with MEN type 2A.3 The classic infrascapular location, history of painful neck muscle spasms, touch hyperesthesia of the lesions, and absence of amyloid deposits on histopathologic study help to differentiate notalgia paresthetica from cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. However, later phases of notalgia paresthetica may show amyloid deposits on histopathologic study, while detection of a scant amount of amyloid is difficult in the early stages of cutaneous lichen amyloidosis.

TAKE-HOME POINT

Cutaneous lichen amyloidosis is usually seen on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It is considered benign, caused by filamentous degeneration of keratinocytes from repeated scratching. But cutaneous lichen amyloidosis at an early age in the scapular area of women warrants a detailed family history for endocrine neoplasia, blood pressure monitoring, thyroid palpation, and blood testing for serum calcium, calcitonin, and parathyroid hormone.

- Scapineli JO, Ceolin L, Puñales MK, Dora JM, Maia AL. MEN 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis: report of three kindred and systematic literature review of clinical, biochemical and molecular characteristics. Fam Cancer 2016; 15:625–633.

- Donovan DT, Levy ML, Furst EJ, et al. Familial cutaneous lichen amyloidosis in association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A: a new variant. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1989; 37:147–150.

- Cox NH, Coulson IH. Systemic disease and the skin. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2010:62.24.

- Moline J, Eng C. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: an overview. Genet Med 2011; 13:755–764.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1085–1087.

- Scapineli JO, Ceolin L, Puñales MK, Dora JM, Maia AL. MEN 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis: report of three kindred and systematic literature review of clinical, biochemical and molecular characteristics. Fam Cancer 2016; 15:625–633.

- Donovan DT, Levy ML, Furst EJ, et al. Familial cutaneous lichen amyloidosis in association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A: a new variant. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1989; 37:147–150.

- Cox NH, Coulson IH. Systemic disease and the skin. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2010:62.24.

- Moline J, Eng C. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: an overview. Genet Med 2011; 13:755–764.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1085–1087.

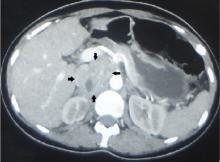

Iliopsoas abscess

A 52-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus presented with a 1-month history of pain in the right lower abdomen and right back. Although she had a fever when the pain started and her pain was aggravated by walking, her pain and fever had gotten better after taking antibiotics prescribed earlier.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for percutaneous drainage, which produced 26 mL of pus on the first day and 320 mL on the next day; culture was positive for Escherichia coli. Urine culture was also positive for E coli; blood culture was not. We concluded that these results were secondary to pyelonephritis.

We started intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam 2.25 g every 8 hours for empiric therapy. We changed this to oral ampicillin-cloxacillin 2 g/day after E coli was cultured and pyelonephritis was suspected. The patient was discharged after a 2-week hospital stay, with no significant complications.

ILIOPSOAS ABSCESS: DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Iliopsoas abscess can occur at any age.1–3 Pain is the most common symptom, occurring in more than 90% of patients.1 Fever with temperatures over 38°C is less common at first, found in less than half of patients.1,2

Only 13% of patients with iliopsoas abscess may have a palpable mass on physical examination.1 The psoas sign—a worsening of lower abdominal pain on the affected side with passive extension of the thigh while supine—has a sensitivity of only 24% for iliopsoas abscess; it can also indicate inflammation to the iliopsoas muscle in other conditions such as retrocecal appendicitis.3

Hip flexion deformity can be a helpful diagnostic feature, as 96% of patients with iliopsoas abscess hold the hip in flexion to relieve pain.4 But pain on hip flexion can also occur in conditions such as septic arthritis.4

Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated in all patients with iliopsoas abscess, so if those markers are not elevated, we may have to consider other conditions such as cancer.1 Computed tomography is nearly 100% sensitive for iliopsoas abscess and is the gold standard for diagnosis.3

TREATMENT

Inadequate treatment of iliopsoas abscess raises the risk of relapse and death.3 Drainage and appropriate antibiotic therapy have been shown to be effective.1,3

Iliopsoas abscess can also be secondary to a number of conditions, eg, Crohn disease, appendicitis, intra-abdominal infection, and cancer,5 and the primary condition needs to be addressed. In addition, culture of a secondary abscess is more likely to grow mixed organisms.5

The average size of the abscess is 6 cm. Percutaneous drainage is required if the mass is larger than 3.5 cm.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

Iliopsoas abscess is difficult to diagnose because patients have few specific complaints. Checking for hip flexion deformity and inflammatory markers may help rule out the disease. When iliopsoas abscess is suspected, computed tomography is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Drainage and appropriate antibiotics are effective treatment.

- Tabrizian P, Nguyen SQ, Greenstein A, Rajhbeharrysingh U, Divino CM. Management and treatment of iliopsoas abscess. Arch Surg 2009; 144:946–949.

- Shields D, Robinson P, Crowley TP. Iliopsoas abscess—a review and update on the literature. Int J Surg 2012; 10:466–469.

- Huang JJ, Ruaan MK, Lan RR, Wang MC. Acute pyogenic iliopsoas abscess in Taiwan: clinical features, diagnosis, treatments and outcome. J Infect 2000; 40:248–255.

- Stefanich RJ, Moskowitz A. Hip flexion deformity secondary to acute pyogenic psoas abscess. Orthop Rev 1987; 16:67–77.

- Ricci MA, Rose FB, Meyer KK. Pyogenic psoas abscess: worldwide variations in etiology. World J Surg 1986; 10:834–843.

A 52-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus presented with a 1-month history of pain in the right lower abdomen and right back. Although she had a fever when the pain started and her pain was aggravated by walking, her pain and fever had gotten better after taking antibiotics prescribed earlier.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for percutaneous drainage, which produced 26 mL of pus on the first day and 320 mL on the next day; culture was positive for Escherichia coli. Urine culture was also positive for E coli; blood culture was not. We concluded that these results were secondary to pyelonephritis.

We started intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam 2.25 g every 8 hours for empiric therapy. We changed this to oral ampicillin-cloxacillin 2 g/day after E coli was cultured and pyelonephritis was suspected. The patient was discharged after a 2-week hospital stay, with no significant complications.

ILIOPSOAS ABSCESS: DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Iliopsoas abscess can occur at any age.1–3 Pain is the most common symptom, occurring in more than 90% of patients.1 Fever with temperatures over 38°C is less common at first, found in less than half of patients.1,2

Only 13% of patients with iliopsoas abscess may have a palpable mass on physical examination.1 The psoas sign—a worsening of lower abdominal pain on the affected side with passive extension of the thigh while supine—has a sensitivity of only 24% for iliopsoas abscess; it can also indicate inflammation to the iliopsoas muscle in other conditions such as retrocecal appendicitis.3

Hip flexion deformity can be a helpful diagnostic feature, as 96% of patients with iliopsoas abscess hold the hip in flexion to relieve pain.4 But pain on hip flexion can also occur in conditions such as septic arthritis.4

Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated in all patients with iliopsoas abscess, so if those markers are not elevated, we may have to consider other conditions such as cancer.1 Computed tomography is nearly 100% sensitive for iliopsoas abscess and is the gold standard for diagnosis.3

TREATMENT

Inadequate treatment of iliopsoas abscess raises the risk of relapse and death.3 Drainage and appropriate antibiotic therapy have been shown to be effective.1,3

Iliopsoas abscess can also be secondary to a number of conditions, eg, Crohn disease, appendicitis, intra-abdominal infection, and cancer,5 and the primary condition needs to be addressed. In addition, culture of a secondary abscess is more likely to grow mixed organisms.5

The average size of the abscess is 6 cm. Percutaneous drainage is required if the mass is larger than 3.5 cm.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

Iliopsoas abscess is difficult to diagnose because patients have few specific complaints. Checking for hip flexion deformity and inflammatory markers may help rule out the disease. When iliopsoas abscess is suspected, computed tomography is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Drainage and appropriate antibiotics are effective treatment.

A 52-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus presented with a 1-month history of pain in the right lower abdomen and right back. Although she had a fever when the pain started and her pain was aggravated by walking, her pain and fever had gotten better after taking antibiotics prescribed earlier.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for percutaneous drainage, which produced 26 mL of pus on the first day and 320 mL on the next day; culture was positive for Escherichia coli. Urine culture was also positive for E coli; blood culture was not. We concluded that these results were secondary to pyelonephritis.

We started intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam 2.25 g every 8 hours for empiric therapy. We changed this to oral ampicillin-cloxacillin 2 g/day after E coli was cultured and pyelonephritis was suspected. The patient was discharged after a 2-week hospital stay, with no significant complications.

ILIOPSOAS ABSCESS: DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Iliopsoas abscess can occur at any age.1–3 Pain is the most common symptom, occurring in more than 90% of patients.1 Fever with temperatures over 38°C is less common at first, found in less than half of patients.1,2

Only 13% of patients with iliopsoas abscess may have a palpable mass on physical examination.1 The psoas sign—a worsening of lower abdominal pain on the affected side with passive extension of the thigh while supine—has a sensitivity of only 24% for iliopsoas abscess; it can also indicate inflammation to the iliopsoas muscle in other conditions such as retrocecal appendicitis.3

Hip flexion deformity can be a helpful diagnostic feature, as 96% of patients with iliopsoas abscess hold the hip in flexion to relieve pain.4 But pain on hip flexion can also occur in conditions such as septic arthritis.4

Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated in all patients with iliopsoas abscess, so if those markers are not elevated, we may have to consider other conditions such as cancer.1 Computed tomography is nearly 100% sensitive for iliopsoas abscess and is the gold standard for diagnosis.3

TREATMENT

Inadequate treatment of iliopsoas abscess raises the risk of relapse and death.3 Drainage and appropriate antibiotic therapy have been shown to be effective.1,3

Iliopsoas abscess can also be secondary to a number of conditions, eg, Crohn disease, appendicitis, intra-abdominal infection, and cancer,5 and the primary condition needs to be addressed. In addition, culture of a secondary abscess is more likely to grow mixed organisms.5

The average size of the abscess is 6 cm. Percutaneous drainage is required if the mass is larger than 3.5 cm.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

Iliopsoas abscess is difficult to diagnose because patients have few specific complaints. Checking for hip flexion deformity and inflammatory markers may help rule out the disease. When iliopsoas abscess is suspected, computed tomography is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Drainage and appropriate antibiotics are effective treatment.

- Tabrizian P, Nguyen SQ, Greenstein A, Rajhbeharrysingh U, Divino CM. Management and treatment of iliopsoas abscess. Arch Surg 2009; 144:946–949.

- Shields D, Robinson P, Crowley TP. Iliopsoas abscess—a review and update on the literature. Int J Surg 2012; 10:466–469.

- Huang JJ, Ruaan MK, Lan RR, Wang MC. Acute pyogenic iliopsoas abscess in Taiwan: clinical features, diagnosis, treatments and outcome. J Infect 2000; 40:248–255.

- Stefanich RJ, Moskowitz A. Hip flexion deformity secondary to acute pyogenic psoas abscess. Orthop Rev 1987; 16:67–77.

- Ricci MA, Rose FB, Meyer KK. Pyogenic psoas abscess: worldwide variations in etiology. World J Surg 1986; 10:834–843.

- Tabrizian P, Nguyen SQ, Greenstein A, Rajhbeharrysingh U, Divino CM. Management and treatment of iliopsoas abscess. Arch Surg 2009; 144:946–949.

- Shields D, Robinson P, Crowley TP. Iliopsoas abscess—a review and update on the literature. Int J Surg 2012; 10:466–469.

- Huang JJ, Ruaan MK, Lan RR, Wang MC. Acute pyogenic iliopsoas abscess in Taiwan: clinical features, diagnosis, treatments and outcome. J Infect 2000; 40:248–255.

- Stefanich RJ, Moskowitz A. Hip flexion deformity secondary to acute pyogenic psoas abscess. Orthop Rev 1987; 16:67–77.

- Ricci MA, Rose FB, Meyer KK. Pyogenic psoas abscess: worldwide variations in etiology. World J Surg 1986; 10:834–843.

Osborn waves of hypothermia

A 40-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with altered mental status. His roommate had found him lying unconscious in snow on the lawn outside his residence. When the emergency medical services team arrived, they recorded a core body temperature of 28.3°C (82.9°F) and instituted advanced cardiac life support.

During transit to the hospital, the patient’s heart rhythm changed from asystole to ventricular fibrillation, and defibrillation was performed twice.

Upon his arrival at the emergency room, advanced life support was continued, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, with slow, wide-complex QRS rhythm noted on electrocardiography (ECG).

On examination, the patient’s pupils were fixed and dilated. The extremities were cold to palpation. The core body temperature dropped to 27.7°C (81.9°F).

Laboratory test results showed severe acidemia (arterial pH 6.8), elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and elevated creatinine and troponin. The troponin was measured 3 times and rose from 0.8 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

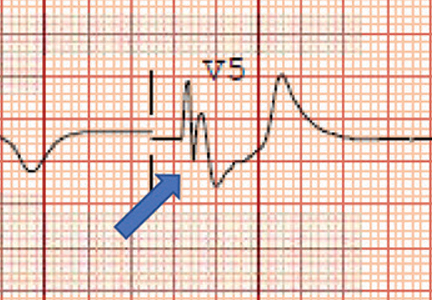

ECG revealed J-point elevation (Osborn waves) in the precordial leads (Figure 1). A baseline electrocardiogram in the medical record from a previous admission had been normal.

An aggressive hypothermia protocol was initiated, but the patient died despite resuscitation efforts.

HYPOTHERMIA AND HEART RHYTHMS

Hypothermia—a core body temperature below 35°C (95°F)—causes generalized slowing of impulse conduction through cardiac tissues, shown on ECG as a prolongation of the PR, RR, QRS, and QT intervals.1

A characteristic feature is elevation of the J point, also called the J wave or Osborn wave, most prominent in precordial leads V2 to V5 and caused by abnormal membrane repolarization in the early phase. The degree of hypothermia correlates linearly with the amplitude of the Osborn wave.2,3

Laboratory tests can identify complications such as rhabdomyolysis, spontaneous bleeding, and lactic acidosis. Moderate to severe hypothermia may cause prolongation of all ECG intervals. Management requires resuscitation and rewarming.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are Brugada syndrome, hypercalcemia, and early repolarization syndrome.

- Doshi HH, Giudici MC. The EKG in hypothermia and hyperthermia. J Electrocardiol 2015; 48:203–208.

- Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung 2001; 30:161–163.

- Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 2001; 12:232–235.

A 40-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with altered mental status. His roommate had found him lying unconscious in snow on the lawn outside his residence. When the emergency medical services team arrived, they recorded a core body temperature of 28.3°C (82.9°F) and instituted advanced cardiac life support.

During transit to the hospital, the patient’s heart rhythm changed from asystole to ventricular fibrillation, and defibrillation was performed twice.

Upon his arrival at the emergency room, advanced life support was continued, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, with slow, wide-complex QRS rhythm noted on electrocardiography (ECG).

On examination, the patient’s pupils were fixed and dilated. The extremities were cold to palpation. The core body temperature dropped to 27.7°C (81.9°F).

Laboratory test results showed severe acidemia (arterial pH 6.8), elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and elevated creatinine and troponin. The troponin was measured 3 times and rose from 0.8 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

ECG revealed J-point elevation (Osborn waves) in the precordial leads (Figure 1). A baseline electrocardiogram in the medical record from a previous admission had been normal.

An aggressive hypothermia protocol was initiated, but the patient died despite resuscitation efforts.

HYPOTHERMIA AND HEART RHYTHMS

Hypothermia—a core body temperature below 35°C (95°F)—causes generalized slowing of impulse conduction through cardiac tissues, shown on ECG as a prolongation of the PR, RR, QRS, and QT intervals.1

A characteristic feature is elevation of the J point, also called the J wave or Osborn wave, most prominent in precordial leads V2 to V5 and caused by abnormal membrane repolarization in the early phase. The degree of hypothermia correlates linearly with the amplitude of the Osborn wave.2,3

Laboratory tests can identify complications such as rhabdomyolysis, spontaneous bleeding, and lactic acidosis. Moderate to severe hypothermia may cause prolongation of all ECG intervals. Management requires resuscitation and rewarming.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are Brugada syndrome, hypercalcemia, and early repolarization syndrome.

A 40-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with altered mental status. His roommate had found him lying unconscious in snow on the lawn outside his residence. When the emergency medical services team arrived, they recorded a core body temperature of 28.3°C (82.9°F) and instituted advanced cardiac life support.

During transit to the hospital, the patient’s heart rhythm changed from asystole to ventricular fibrillation, and defibrillation was performed twice.

Upon his arrival at the emergency room, advanced life support was continued, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, with slow, wide-complex QRS rhythm noted on electrocardiography (ECG).

On examination, the patient’s pupils were fixed and dilated. The extremities were cold to palpation. The core body temperature dropped to 27.7°C (81.9°F).

Laboratory test results showed severe acidemia (arterial pH 6.8), elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and elevated creatinine and troponin. The troponin was measured 3 times and rose from 0.8 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

ECG revealed J-point elevation (Osborn waves) in the precordial leads (Figure 1). A baseline electrocardiogram in the medical record from a previous admission had been normal.

An aggressive hypothermia protocol was initiated, but the patient died despite resuscitation efforts.

HYPOTHERMIA AND HEART RHYTHMS

Hypothermia—a core body temperature below 35°C (95°F)—causes generalized slowing of impulse conduction through cardiac tissues, shown on ECG as a prolongation of the PR, RR, QRS, and QT intervals.1

A characteristic feature is elevation of the J point, also called the J wave or Osborn wave, most prominent in precordial leads V2 to V5 and caused by abnormal membrane repolarization in the early phase. The degree of hypothermia correlates linearly with the amplitude of the Osborn wave.2,3

Laboratory tests can identify complications such as rhabdomyolysis, spontaneous bleeding, and lactic acidosis. Moderate to severe hypothermia may cause prolongation of all ECG intervals. Management requires resuscitation and rewarming.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are Brugada syndrome, hypercalcemia, and early repolarization syndrome.

- Doshi HH, Giudici MC. The EKG in hypothermia and hyperthermia. J Electrocardiol 2015; 48:203–208.

- Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung 2001; 30:161–163.

- Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 2001; 12:232–235.

- Doshi HH, Giudici MC. The EKG in hypothermia and hyperthermia. J Electrocardiol 2015; 48:203–208.

- Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung 2001; 30:161–163.

- Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 2001; 12:232–235.

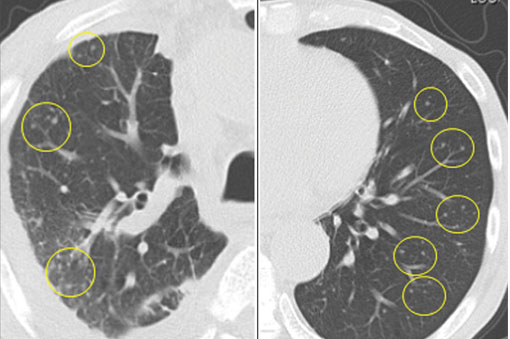

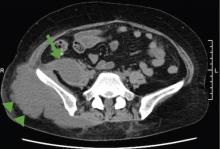

Sarcoidosis mimicking lytic osseous metastases

A 41-year-old woman presented with coughing, wheezing, and painful subcutaneous nodules on her legs. She had presented 6 years ago with similar nodules and enlarged retroauricular, occipital, and maxillary lymph nodes. At that time, biopsy study of submaxillary lymph nodes and skin showed nonnecrotizing granulomas, with negative microbiology studies. Chest radiography and spirometry were normal. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. Treatment was offered but refused.

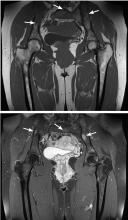

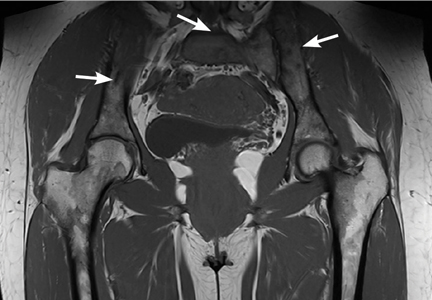

Based on this history, computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen was performed and showed mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, small bilateral lung nodules, and osseous cystic areas in both iliac blades. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed numerous discrete lesions in both iliac bones (Figure 1). Biopsy study of iliac bone revealed preserved architecture with no evidence of malignancy or granulomas.

Radiography of the hands showed an osseous lytic lesion in the third proximal phalanx of the right hand. No other radiographic abnormalities were noted.

The clinical and radiographic features and the patient’s clinical course were consistent with osseous sarcoidosis. She was started on methotrexate and a low-dose corticosteroid and was symptom-free at 12-month follow-up. Follow-up MRI showed reduction in the lymphadenopathies and stabilization of the bone lesions.

SARCOIDOSIS AND BONE

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that involves the lung in more than 90% of cases. Skeletal involvement has been reported in 1% to 14% of patients.1,2 Typical osseous involvement is cystic osteitis of the phalangeal bones of the hands and feet, but any part of the skeleton may be involved.3

Bone sarcoidosis is usually asymptomatic and is discovered incidentally. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis has usually been established clinically before bone lesions are detected on MRI. However, sarcoidosis-related bone lesions resembling bone metastases on MRI may be the initial presentation. The presence of intralesional fat has been described as a feature that excludes malignancy.

No treatment has been shown to be of benefit.4 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion and radiographic lytic bone features are not specific, so a neoplastic cause (such as primary osteoblastoma, metastasis, or multiple myeloma) must always be ruled out, as well as other bone conditions such as osteomyelitis or bone cyst.

- Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014; 383:1155–1167.

- James DG, Neville E, Carstairs LS. Bone and joint sarcoidosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1976; 6:53–81.

- Moore SL, Kransdorf MJ, Schweitzer ME, Murphey MD, Babb JS. Can sarcoidosis and metastatic bone lesions be reliably differentiated on routine MRI? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 198:1387–1393.

- Hamoud S, Srour S, Fruchter O, Vlodavsky E, Hayek T. Lytic bone lesion: presenting finding of sarcoidosis. Isr Med Assoc J 2010; 12:59–60.

A 41-year-old woman presented with coughing, wheezing, and painful subcutaneous nodules on her legs. She had presented 6 years ago with similar nodules and enlarged retroauricular, occipital, and maxillary lymph nodes. At that time, biopsy study of submaxillary lymph nodes and skin showed nonnecrotizing granulomas, with negative microbiology studies. Chest radiography and spirometry were normal. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. Treatment was offered but refused.

Based on this history, computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen was performed and showed mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, small bilateral lung nodules, and osseous cystic areas in both iliac blades. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed numerous discrete lesions in both iliac bones (Figure 1). Biopsy study of iliac bone revealed preserved architecture with no evidence of malignancy or granulomas.

Radiography of the hands showed an osseous lytic lesion in the third proximal phalanx of the right hand. No other radiographic abnormalities were noted.

The clinical and radiographic features and the patient’s clinical course were consistent with osseous sarcoidosis. She was started on methotrexate and a low-dose corticosteroid and was symptom-free at 12-month follow-up. Follow-up MRI showed reduction in the lymphadenopathies and stabilization of the bone lesions.

SARCOIDOSIS AND BONE

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that involves the lung in more than 90% of cases. Skeletal involvement has been reported in 1% to 14% of patients.1,2 Typical osseous involvement is cystic osteitis of the phalangeal bones of the hands and feet, but any part of the skeleton may be involved.3

Bone sarcoidosis is usually asymptomatic and is discovered incidentally. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis has usually been established clinically before bone lesions are detected on MRI. However, sarcoidosis-related bone lesions resembling bone metastases on MRI may be the initial presentation. The presence of intralesional fat has been described as a feature that excludes malignancy.

No treatment has been shown to be of benefit.4 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion and radiographic lytic bone features are not specific, so a neoplastic cause (such as primary osteoblastoma, metastasis, or multiple myeloma) must always be ruled out, as well as other bone conditions such as osteomyelitis or bone cyst.

A 41-year-old woman presented with coughing, wheezing, and painful subcutaneous nodules on her legs. She had presented 6 years ago with similar nodules and enlarged retroauricular, occipital, and maxillary lymph nodes. At that time, biopsy study of submaxillary lymph nodes and skin showed nonnecrotizing granulomas, with negative microbiology studies. Chest radiography and spirometry were normal. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. Treatment was offered but refused.

Based on this history, computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen was performed and showed mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, small bilateral lung nodules, and osseous cystic areas in both iliac blades. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed numerous discrete lesions in both iliac bones (Figure 1). Biopsy study of iliac bone revealed preserved architecture with no evidence of malignancy or granulomas.

Radiography of the hands showed an osseous lytic lesion in the third proximal phalanx of the right hand. No other radiographic abnormalities were noted.

The clinical and radiographic features and the patient’s clinical course were consistent with osseous sarcoidosis. She was started on methotrexate and a low-dose corticosteroid and was symptom-free at 12-month follow-up. Follow-up MRI showed reduction in the lymphadenopathies and stabilization of the bone lesions.

SARCOIDOSIS AND BONE

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that involves the lung in more than 90% of cases. Skeletal involvement has been reported in 1% to 14% of patients.1,2 Typical osseous involvement is cystic osteitis of the phalangeal bones of the hands and feet, but any part of the skeleton may be involved.3

Bone sarcoidosis is usually asymptomatic and is discovered incidentally. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis has usually been established clinically before bone lesions are detected on MRI. However, sarcoidosis-related bone lesions resembling bone metastases on MRI may be the initial presentation. The presence of intralesional fat has been described as a feature that excludes malignancy.

No treatment has been shown to be of benefit.4 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion and radiographic lytic bone features are not specific, so a neoplastic cause (such as primary osteoblastoma, metastasis, or multiple myeloma) must always be ruled out, as well as other bone conditions such as osteomyelitis or bone cyst.

- Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014; 383:1155–1167.

- James DG, Neville E, Carstairs LS. Bone and joint sarcoidosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1976; 6:53–81.

- Moore SL, Kransdorf MJ, Schweitzer ME, Murphey MD, Babb JS. Can sarcoidosis and metastatic bone lesions be reliably differentiated on routine MRI? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 198:1387–1393.

- Hamoud S, Srour S, Fruchter O, Vlodavsky E, Hayek T. Lytic bone lesion: presenting finding of sarcoidosis. Isr Med Assoc J 2010; 12:59–60.

- Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014; 383:1155–1167.

- James DG, Neville E, Carstairs LS. Bone and joint sarcoidosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1976; 6:53–81.

- Moore SL, Kransdorf MJ, Schweitzer ME, Murphey MD, Babb JS. Can sarcoidosis and metastatic bone lesions be reliably differentiated on routine MRI? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 198:1387–1393.

- Hamoud S, Srour S, Fruchter O, Vlodavsky E, Hayek T. Lytic bone lesion: presenting finding of sarcoidosis. Isr Med Assoc J 2010; 12:59–60.