User login

Heartburn or heart attack? A mimic of MI

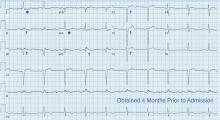

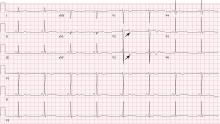

A 71-year-old man with a history of hypertension, 4 prior myocardial infarctions (MIs), and well-compensated ischemic cardiomyopathy presented to the emergency department after 2 episodes of sharp pain in the left upper abdomen and chest. The episodes lasted 1 to 2 minutes and were not relieved by rest. Their location was similar to that of the pain he experienced with his MIs. He could not identify any exacerbating or ameliorating factors. The pain had resolved without specific therapy before he arrived.

He reported polydipsia and constipation over the past 2 weeks and generalized muscle weakness and acute exacerbations of chronic back pain in the past 2 days. Neither he nor a friend who accompanied him noticed any confusion. He had been taking as many as 15 calcium carbonate tablets a day for 6 weeks to self-treat dyspepsia refractory to once-daily ranitidine, and hydrochlorothiazide for his hypertension for 3 weeks.

FURTHER EVALUATION, CARDIOLOGY CONSULT

On physical examination, he had diffuse weakness, dry mucous membranes, and an irregular heart rhythm.

Laboratory testing showed the following:

- Troponin I 0.11 ng/mL (reference range ≤ 0.04); repeated, it was 0.12 ng/mL

- Serum creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (0.44–1.27) (9 months earlier it had been 0.99 mg/dL)

- Serum calcium 17.3 mg/dL (8.6–10.5)

- Parathyroid hormone 9 pg/mL (12–88)

- Serum bicarbonate 33 mmol/L (24–32); 2 weeks earlier, it had been 27 mmol/L.

DIAGNOSIS: MILK-ALKALI SYNDROME

The diagnosis, based on the presentation and the results of the workup, was milk-alkali syndrome complicated by recent hydrochlorothiazide use. This syndrome consists of the triad of hypercalcemia, metabolic alkalosis, and acute kidney injury, all due to excessive ingestion of calcium and alkali, usually calcium carbonate.

His hydrochlorothiazide and calcium carbonate were discontinued. He was given intravenous normal saline and subcutaneous calcitonin, and his serum calcium level came down to 11.5 mg/dL within the next 24 hours. His dyspepsia was treated with pantoprazole.

The patient had no further episodes of chest pain, and the cardiology consult team again recommended against coronary angiography. Repeat ECG after the hypercalcemia resolved showed results identical to those 4 months before his admission. Two months later, his serum calcium level was 9.4 mg/dL and his creatinine level was 1.24 mg/dL.

A MIMIC OF STEMI

In numerous reported cases, these electrocardiographic findings coupled with chest pain led to misdiagnosis of STEMI.1–3 While STEMI and occasionally hypercalcemia can cause ST elevation, hypercalcemia causes a significant shortening of the corrected QT interval that is not associated with STEMI.4,5

Ultimately, the diagnosis of MI involves clinical, laboratory, and ECG findings, and if a strong clinical suspicion for myocardial ischemia exists, STEMI cannot reliably be distinguished from hypercalcemia by ECG alone. It is nonetheless important to be aware of this complication of hypercalcemia to avoid unnecessary cardiac interventions.

- Ashizawa N, Arakawa S, Koide Y, Toda G, Seto S, Yano K. Hypercalcemia due to vitamin D intoxication with clinical features mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med 2003; 42:340–344.

- Nishi SP, Barbagelata NA, Atar S, Birnbaum Y, Tuero E. Hypercalcemia-induced ST-segment elevation mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Electrocardiol 2006; 39:298–300.

- Turnham S, Kilickap M, Kilinc S. ST segment elevation mimicking acute myocardial infarction in hypercalcemia. Heart 2005; 91:999.

- Nierenberg DW, Ransil BJ. Q-aTc interval as a clinical indicator of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol 1979; 44:243–248.

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11:395–400.

A 71-year-old man with a history of hypertension, 4 prior myocardial infarctions (MIs), and well-compensated ischemic cardiomyopathy presented to the emergency department after 2 episodes of sharp pain in the left upper abdomen and chest. The episodes lasted 1 to 2 minutes and were not relieved by rest. Their location was similar to that of the pain he experienced with his MIs. He could not identify any exacerbating or ameliorating factors. The pain had resolved without specific therapy before he arrived.

He reported polydipsia and constipation over the past 2 weeks and generalized muscle weakness and acute exacerbations of chronic back pain in the past 2 days. Neither he nor a friend who accompanied him noticed any confusion. He had been taking as many as 15 calcium carbonate tablets a day for 6 weeks to self-treat dyspepsia refractory to once-daily ranitidine, and hydrochlorothiazide for his hypertension for 3 weeks.

FURTHER EVALUATION, CARDIOLOGY CONSULT

On physical examination, he had diffuse weakness, dry mucous membranes, and an irregular heart rhythm.

Laboratory testing showed the following:

- Troponin I 0.11 ng/mL (reference range ≤ 0.04); repeated, it was 0.12 ng/mL

- Serum creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (0.44–1.27) (9 months earlier it had been 0.99 mg/dL)

- Serum calcium 17.3 mg/dL (8.6–10.5)

- Parathyroid hormone 9 pg/mL (12–88)

- Serum bicarbonate 33 mmol/L (24–32); 2 weeks earlier, it had been 27 mmol/L.

DIAGNOSIS: MILK-ALKALI SYNDROME

The diagnosis, based on the presentation and the results of the workup, was milk-alkali syndrome complicated by recent hydrochlorothiazide use. This syndrome consists of the triad of hypercalcemia, metabolic alkalosis, and acute kidney injury, all due to excessive ingestion of calcium and alkali, usually calcium carbonate.

His hydrochlorothiazide and calcium carbonate were discontinued. He was given intravenous normal saline and subcutaneous calcitonin, and his serum calcium level came down to 11.5 mg/dL within the next 24 hours. His dyspepsia was treated with pantoprazole.

The patient had no further episodes of chest pain, and the cardiology consult team again recommended against coronary angiography. Repeat ECG after the hypercalcemia resolved showed results identical to those 4 months before his admission. Two months later, his serum calcium level was 9.4 mg/dL and his creatinine level was 1.24 mg/dL.

A MIMIC OF STEMI

In numerous reported cases, these electrocardiographic findings coupled with chest pain led to misdiagnosis of STEMI.1–3 While STEMI and occasionally hypercalcemia can cause ST elevation, hypercalcemia causes a significant shortening of the corrected QT interval that is not associated with STEMI.4,5

Ultimately, the diagnosis of MI involves clinical, laboratory, and ECG findings, and if a strong clinical suspicion for myocardial ischemia exists, STEMI cannot reliably be distinguished from hypercalcemia by ECG alone. It is nonetheless important to be aware of this complication of hypercalcemia to avoid unnecessary cardiac interventions.

A 71-year-old man with a history of hypertension, 4 prior myocardial infarctions (MIs), and well-compensated ischemic cardiomyopathy presented to the emergency department after 2 episodes of sharp pain in the left upper abdomen and chest. The episodes lasted 1 to 2 minutes and were not relieved by rest. Their location was similar to that of the pain he experienced with his MIs. He could not identify any exacerbating or ameliorating factors. The pain had resolved without specific therapy before he arrived.

He reported polydipsia and constipation over the past 2 weeks and generalized muscle weakness and acute exacerbations of chronic back pain in the past 2 days. Neither he nor a friend who accompanied him noticed any confusion. He had been taking as many as 15 calcium carbonate tablets a day for 6 weeks to self-treat dyspepsia refractory to once-daily ranitidine, and hydrochlorothiazide for his hypertension for 3 weeks.

FURTHER EVALUATION, CARDIOLOGY CONSULT

On physical examination, he had diffuse weakness, dry mucous membranes, and an irregular heart rhythm.

Laboratory testing showed the following:

- Troponin I 0.11 ng/mL (reference range ≤ 0.04); repeated, it was 0.12 ng/mL

- Serum creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (0.44–1.27) (9 months earlier it had been 0.99 mg/dL)

- Serum calcium 17.3 mg/dL (8.6–10.5)

- Parathyroid hormone 9 pg/mL (12–88)

- Serum bicarbonate 33 mmol/L (24–32); 2 weeks earlier, it had been 27 mmol/L.

DIAGNOSIS: MILK-ALKALI SYNDROME

The diagnosis, based on the presentation and the results of the workup, was milk-alkali syndrome complicated by recent hydrochlorothiazide use. This syndrome consists of the triad of hypercalcemia, metabolic alkalosis, and acute kidney injury, all due to excessive ingestion of calcium and alkali, usually calcium carbonate.

His hydrochlorothiazide and calcium carbonate were discontinued. He was given intravenous normal saline and subcutaneous calcitonin, and his serum calcium level came down to 11.5 mg/dL within the next 24 hours. His dyspepsia was treated with pantoprazole.

The patient had no further episodes of chest pain, and the cardiology consult team again recommended against coronary angiography. Repeat ECG after the hypercalcemia resolved showed results identical to those 4 months before his admission. Two months later, his serum calcium level was 9.4 mg/dL and his creatinine level was 1.24 mg/dL.

A MIMIC OF STEMI

In numerous reported cases, these electrocardiographic findings coupled with chest pain led to misdiagnosis of STEMI.1–3 While STEMI and occasionally hypercalcemia can cause ST elevation, hypercalcemia causes a significant shortening of the corrected QT interval that is not associated with STEMI.4,5

Ultimately, the diagnosis of MI involves clinical, laboratory, and ECG findings, and if a strong clinical suspicion for myocardial ischemia exists, STEMI cannot reliably be distinguished from hypercalcemia by ECG alone. It is nonetheless important to be aware of this complication of hypercalcemia to avoid unnecessary cardiac interventions.

- Ashizawa N, Arakawa S, Koide Y, Toda G, Seto S, Yano K. Hypercalcemia due to vitamin D intoxication with clinical features mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med 2003; 42:340–344.

- Nishi SP, Barbagelata NA, Atar S, Birnbaum Y, Tuero E. Hypercalcemia-induced ST-segment elevation mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Electrocardiol 2006; 39:298–300.

- Turnham S, Kilickap M, Kilinc S. ST segment elevation mimicking acute myocardial infarction in hypercalcemia. Heart 2005; 91:999.

- Nierenberg DW, Ransil BJ. Q-aTc interval as a clinical indicator of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol 1979; 44:243–248.

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11:395–400.

- Ashizawa N, Arakawa S, Koide Y, Toda G, Seto S, Yano K. Hypercalcemia due to vitamin D intoxication with clinical features mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med 2003; 42:340–344.

- Nishi SP, Barbagelata NA, Atar S, Birnbaum Y, Tuero E. Hypercalcemia-induced ST-segment elevation mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Electrocardiol 2006; 39:298–300.

- Turnham S, Kilickap M, Kilinc S. ST segment elevation mimicking acute myocardial infarction in hypercalcemia. Heart 2005; 91:999.

- Nierenberg DW, Ransil BJ. Q-aTc interval as a clinical indicator of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol 1979; 44:243–248.

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11:395–400.

Palmar erythema as a sign of cancer

An 83-year-old man presented with fatigue and anorexia. Two years earlier, a small lung nodule had been found that was suspected to be primary lung cancer; however, he had refused surgical treatment or chemotherapy because of his age.

Aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels had been normal, and results of serologic testing for hepatitis viruses were negative, making chronic liver disease unlikely. He was not a habitual drinker and was not taking any medications.

Laboratory and imaging studies revealed lung cancer with hepatic metastasis complicated by severe hypercalcemia. The estradiol level was normal, but the serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentration was high.

PALMAR ERYTHEMA AND SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Palmar erythema syndrome is characterized by reddening of the palmar skin, especially in the thenar and hypothenar areas, the distal portion of the palm, and the fingertips; the dorsal surface of the hand is rarely affected.1 The affected areas are typically not pruritic or painful.

Conditions in the differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of palmar erythema includes allergic drug eruptions, contact dermatitis, erythema multiforme, cellulitis, dermatomyositis, and palmoplantar pustulosis. Hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction are other important conditions to consider in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.2 Hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction can present as palmoplantar erythema and are usually accompanied by dysesthesia and swelling.

Palmar erythema can develop in either primary or secondary forms as a result of an underlying systemic disease.2 Although the pathogenesis is not fully understood, the impaired degradation or increased production of angiogenic factors appears to be essential. The hormone estrogen can induce vascularization3 and is known to cause palmar erythema in pregnant women and patients with cirrhosis. Because estradiol is metabolized in the liver, increased levels of estrogen are associated with hepatic decompensation in cirrhosis.4

Neoplasm can cause palmar erythema.2,5 In a clinicopathologic study of brain tumors, palmar erythema was recognized in 27 (25%) of 107 patients.5 Histologic examination in that study demonstrated that the intensity of erythema correlated with both cutaneous vessel dilation and prominent vascularization in the patients’ brain tumors, suggesting the role of circulating angiogenic factors such as VEGF. VEGF is a potent mediator of angiogenesis, which is critical for tumor development and growth.6

Our patient had a metastatic hepatic tumor, a normal estradiol level, and an increased level of VEGF, suggesting that the VEGF produced by the neoplasm promoted the development of palmar erythema.

The presence of palmar erythema in cancer patients is likely underestimated2 and may suggest the presence of malignancy when it develops in the elderly.

In our patient, intensive hydration and intravenous bisphosphonate administration rapidly corrected the malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. However, he was severely debilitated during the hospital stay and developed aspiration pneumonia repeatedly. Thereafter, he was transferred to hospice care. The palmar erythema remained after the electrolyte disorder was corrected.

- Perera GA. A note on palmar erythema (so-called liver palms). JAMA 1942; 119:1417–1418.

- Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007; 8:347–356.

- Losordo DW, Isner JM. Estrogen and angiogenesis: a review. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:6–12.

- Maruyama Y, Adachi Y, Aoki N, Suzuki Y, Shinohara H, Yamamoto T. Mechanism of feminization in male patients with non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis: role of sex hormone-binding globulin. Gastroenterol Jpn 1991; 26: 435–439.

- Noble JP, Boisnic S, Branchet-Gumila MC, Poisson M. Palmar erythema: cutaneous marker of neoplasms. Dermatology 2002; 204:209–213.

- Zheng CL, Qiu C, Shen MX, et al. Prognostic impact of elevation of vascular endothelial growth factor family expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16:1881–1895.

An 83-year-old man presented with fatigue and anorexia. Two years earlier, a small lung nodule had been found that was suspected to be primary lung cancer; however, he had refused surgical treatment or chemotherapy because of his age.

Aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels had been normal, and results of serologic testing for hepatitis viruses were negative, making chronic liver disease unlikely. He was not a habitual drinker and was not taking any medications.

Laboratory and imaging studies revealed lung cancer with hepatic metastasis complicated by severe hypercalcemia. The estradiol level was normal, but the serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentration was high.

PALMAR ERYTHEMA AND SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Palmar erythema syndrome is characterized by reddening of the palmar skin, especially in the thenar and hypothenar areas, the distal portion of the palm, and the fingertips; the dorsal surface of the hand is rarely affected.1 The affected areas are typically not pruritic or painful.

Conditions in the differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of palmar erythema includes allergic drug eruptions, contact dermatitis, erythema multiforme, cellulitis, dermatomyositis, and palmoplantar pustulosis. Hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction are other important conditions to consider in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.2 Hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction can present as palmoplantar erythema and are usually accompanied by dysesthesia and swelling.

Palmar erythema can develop in either primary or secondary forms as a result of an underlying systemic disease.2 Although the pathogenesis is not fully understood, the impaired degradation or increased production of angiogenic factors appears to be essential. The hormone estrogen can induce vascularization3 and is known to cause palmar erythema in pregnant women and patients with cirrhosis. Because estradiol is metabolized in the liver, increased levels of estrogen are associated with hepatic decompensation in cirrhosis.4

Neoplasm can cause palmar erythema.2,5 In a clinicopathologic study of brain tumors, palmar erythema was recognized in 27 (25%) of 107 patients.5 Histologic examination in that study demonstrated that the intensity of erythema correlated with both cutaneous vessel dilation and prominent vascularization in the patients’ brain tumors, suggesting the role of circulating angiogenic factors such as VEGF. VEGF is a potent mediator of angiogenesis, which is critical for tumor development and growth.6

Our patient had a metastatic hepatic tumor, a normal estradiol level, and an increased level of VEGF, suggesting that the VEGF produced by the neoplasm promoted the development of palmar erythema.

The presence of palmar erythema in cancer patients is likely underestimated2 and may suggest the presence of malignancy when it develops in the elderly.

In our patient, intensive hydration and intravenous bisphosphonate administration rapidly corrected the malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. However, he was severely debilitated during the hospital stay and developed aspiration pneumonia repeatedly. Thereafter, he was transferred to hospice care. The palmar erythema remained after the electrolyte disorder was corrected.

An 83-year-old man presented with fatigue and anorexia. Two years earlier, a small lung nodule had been found that was suspected to be primary lung cancer; however, he had refused surgical treatment or chemotherapy because of his age.

Aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels had been normal, and results of serologic testing for hepatitis viruses were negative, making chronic liver disease unlikely. He was not a habitual drinker and was not taking any medications.

Laboratory and imaging studies revealed lung cancer with hepatic metastasis complicated by severe hypercalcemia. The estradiol level was normal, but the serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentration was high.

PALMAR ERYTHEMA AND SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Palmar erythema syndrome is characterized by reddening of the palmar skin, especially in the thenar and hypothenar areas, the distal portion of the palm, and the fingertips; the dorsal surface of the hand is rarely affected.1 The affected areas are typically not pruritic or painful.

Conditions in the differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of palmar erythema includes allergic drug eruptions, contact dermatitis, erythema multiforme, cellulitis, dermatomyositis, and palmoplantar pustulosis. Hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction are other important conditions to consider in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.2 Hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction can present as palmoplantar erythema and are usually accompanied by dysesthesia and swelling.

Palmar erythema can develop in either primary or secondary forms as a result of an underlying systemic disease.2 Although the pathogenesis is not fully understood, the impaired degradation or increased production of angiogenic factors appears to be essential. The hormone estrogen can induce vascularization3 and is known to cause palmar erythema in pregnant women and patients with cirrhosis. Because estradiol is metabolized in the liver, increased levels of estrogen are associated with hepatic decompensation in cirrhosis.4

Neoplasm can cause palmar erythema.2,5 In a clinicopathologic study of brain tumors, palmar erythema was recognized in 27 (25%) of 107 patients.5 Histologic examination in that study demonstrated that the intensity of erythema correlated with both cutaneous vessel dilation and prominent vascularization in the patients’ brain tumors, suggesting the role of circulating angiogenic factors such as VEGF. VEGF is a potent mediator of angiogenesis, which is critical for tumor development and growth.6

Our patient had a metastatic hepatic tumor, a normal estradiol level, and an increased level of VEGF, suggesting that the VEGF produced by the neoplasm promoted the development of palmar erythema.

The presence of palmar erythema in cancer patients is likely underestimated2 and may suggest the presence of malignancy when it develops in the elderly.

In our patient, intensive hydration and intravenous bisphosphonate administration rapidly corrected the malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. However, he was severely debilitated during the hospital stay and developed aspiration pneumonia repeatedly. Thereafter, he was transferred to hospice care. The palmar erythema remained after the electrolyte disorder was corrected.

- Perera GA. A note on palmar erythema (so-called liver palms). JAMA 1942; 119:1417–1418.

- Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007; 8:347–356.

- Losordo DW, Isner JM. Estrogen and angiogenesis: a review. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:6–12.

- Maruyama Y, Adachi Y, Aoki N, Suzuki Y, Shinohara H, Yamamoto T. Mechanism of feminization in male patients with non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis: role of sex hormone-binding globulin. Gastroenterol Jpn 1991; 26: 435–439.

- Noble JP, Boisnic S, Branchet-Gumila MC, Poisson M. Palmar erythema: cutaneous marker of neoplasms. Dermatology 2002; 204:209–213.

- Zheng CL, Qiu C, Shen MX, et al. Prognostic impact of elevation of vascular endothelial growth factor family expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16:1881–1895.

- Perera GA. A note on palmar erythema (so-called liver palms). JAMA 1942; 119:1417–1418.

- Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007; 8:347–356.

- Losordo DW, Isner JM. Estrogen and angiogenesis: a review. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:6–12.

- Maruyama Y, Adachi Y, Aoki N, Suzuki Y, Shinohara H, Yamamoto T. Mechanism of feminization in male patients with non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis: role of sex hormone-binding globulin. Gastroenterol Jpn 1991; 26: 435–439.

- Noble JP, Boisnic S, Branchet-Gumila MC, Poisson M. Palmar erythema: cutaneous marker of neoplasms. Dermatology 2002; 204:209–213.

- Zheng CL, Qiu C, Shen MX, et al. Prognostic impact of elevation of vascular endothelial growth factor family expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16:1881–1895.

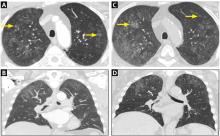

Metastatic pulmonary calcification and end-stage renal disease

A 64-year-old man with end-stage renal disease was evaluated in the pulmonary clinic for persistent abnormalities on axial computed tomography (CT) of the chest. He was a lifelong nonsmoker and had no history of exposure to occupational dust or fumes. His oxygen saturation was 100% on room air, and he denied any respiratory symptoms.

WHEN TO CONSIDER METASTATIC PULMONARY CALCIFICATION

The differential diagnosis for chronic upper-lobe-predominant ground-glass nodules is broad and includes atypical infections, recurrent alveolar hemorrhage, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, occupational lung disease, and pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. However, several aspects of our patient’s case suggested an often overlooked diagnosis, metastatic pulmonary calcification.

Metastatic pulmonary calcification is caused by deposition of calcium salts in lung tissue and is most commonly seen in patients on dialysis,1,2 and our patient had been dependent on dialysis for many years. The chronically elevated calcium-phosphorus product and secondary hyperparathyroidism often seen with end-stage renal disease may explain this association.

Our patient’s lack of symptoms is also an important diagnostic clue. Unlike many other causes of chronic upper-lobe-predominant ground-glass nodules, metastatic pulmonary calcification does not usually cause symptoms and is often identified only at autopsy.3 Results of pulmonary function testing are often normal.4

Metastatic pulmonary calcification can appear as diffusely calcified nodules or high-attenuation areas of consolidation on CT. However, as in our patient’s case, CT may demonstrate fluffy, centrilobular ground-glass nodules due to the microscopic size of the deposited calcium crystals.1 Identifying calcified vessels on imaging supports the diagnosis.4

Treatment of metastatic pulmonary calcification in a patient with end-stage renal disease is focused on correcting underlying metabolic abnormalities with phosphate binders, vitamin D supplementation, and dialysis.

- Chan ED, Morales DV, Welsh CH, McDermott MT, Schwarz MI. Calcium deposition with or without bone formation in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:1654–1669.

- Beyzaei A, Francis J, Knight H, Simon DB, Finkelstein FO. Metabolic lung disease: diffuse metastatic pulmonary calcifications with progression to calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Adv Perit Dial 2007; 23:112–117.

- Conger JD, Hammond WS, Alfrey AC, Contiguglia SR, Stanford RE, Huffer WE. Pulmonary calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Clinical and pathologic studies. Ann Intern Med 1975; 83:330–336.

- Belem LC, Zanetti G, Souza AS Jr, et al. Metastatic pulmonary calcification: state-of-the-art review focused on imaging findings. Respir Med 2014; 108:668–676.

A 64-year-old man with end-stage renal disease was evaluated in the pulmonary clinic for persistent abnormalities on axial computed tomography (CT) of the chest. He was a lifelong nonsmoker and had no history of exposure to occupational dust or fumes. His oxygen saturation was 100% on room air, and he denied any respiratory symptoms.

WHEN TO CONSIDER METASTATIC PULMONARY CALCIFICATION

The differential diagnosis for chronic upper-lobe-predominant ground-glass nodules is broad and includes atypical infections, recurrent alveolar hemorrhage, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, occupational lung disease, and pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. However, several aspects of our patient’s case suggested an often overlooked diagnosis, metastatic pulmonary calcification.

Metastatic pulmonary calcification is caused by deposition of calcium salts in lung tissue and is most commonly seen in patients on dialysis,1,2 and our patient had been dependent on dialysis for many years. The chronically elevated calcium-phosphorus product and secondary hyperparathyroidism often seen with end-stage renal disease may explain this association.

Our patient’s lack of symptoms is also an important diagnostic clue. Unlike many other causes of chronic upper-lobe-predominant ground-glass nodules, metastatic pulmonary calcification does not usually cause symptoms and is often identified only at autopsy.3 Results of pulmonary function testing are often normal.4

Metastatic pulmonary calcification can appear as diffusely calcified nodules or high-attenuation areas of consolidation on CT. However, as in our patient’s case, CT may demonstrate fluffy, centrilobular ground-glass nodules due to the microscopic size of the deposited calcium crystals.1 Identifying calcified vessels on imaging supports the diagnosis.4

Treatment of metastatic pulmonary calcification in a patient with end-stage renal disease is focused on correcting underlying metabolic abnormalities with phosphate binders, vitamin D supplementation, and dialysis.

A 64-year-old man with end-stage renal disease was evaluated in the pulmonary clinic for persistent abnormalities on axial computed tomography (CT) of the chest. He was a lifelong nonsmoker and had no history of exposure to occupational dust or fumes. His oxygen saturation was 100% on room air, and he denied any respiratory symptoms.

WHEN TO CONSIDER METASTATIC PULMONARY CALCIFICATION

The differential diagnosis for chronic upper-lobe-predominant ground-glass nodules is broad and includes atypical infections, recurrent alveolar hemorrhage, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, occupational lung disease, and pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. However, several aspects of our patient’s case suggested an often overlooked diagnosis, metastatic pulmonary calcification.

Metastatic pulmonary calcification is caused by deposition of calcium salts in lung tissue and is most commonly seen in patients on dialysis,1,2 and our patient had been dependent on dialysis for many years. The chronically elevated calcium-phosphorus product and secondary hyperparathyroidism often seen with end-stage renal disease may explain this association.

Our patient’s lack of symptoms is also an important diagnostic clue. Unlike many other causes of chronic upper-lobe-predominant ground-glass nodules, metastatic pulmonary calcification does not usually cause symptoms and is often identified only at autopsy.3 Results of pulmonary function testing are often normal.4

Metastatic pulmonary calcification can appear as diffusely calcified nodules or high-attenuation areas of consolidation on CT. However, as in our patient’s case, CT may demonstrate fluffy, centrilobular ground-glass nodules due to the microscopic size of the deposited calcium crystals.1 Identifying calcified vessels on imaging supports the diagnosis.4

Treatment of metastatic pulmonary calcification in a patient with end-stage renal disease is focused on correcting underlying metabolic abnormalities with phosphate binders, vitamin D supplementation, and dialysis.

- Chan ED, Morales DV, Welsh CH, McDermott MT, Schwarz MI. Calcium deposition with or without bone formation in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:1654–1669.

- Beyzaei A, Francis J, Knight H, Simon DB, Finkelstein FO. Metabolic lung disease: diffuse metastatic pulmonary calcifications with progression to calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Adv Perit Dial 2007; 23:112–117.

- Conger JD, Hammond WS, Alfrey AC, Contiguglia SR, Stanford RE, Huffer WE. Pulmonary calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Clinical and pathologic studies. Ann Intern Med 1975; 83:330–336.

- Belem LC, Zanetti G, Souza AS Jr, et al. Metastatic pulmonary calcification: state-of-the-art review focused on imaging findings. Respir Med 2014; 108:668–676.

- Chan ED, Morales DV, Welsh CH, McDermott MT, Schwarz MI. Calcium deposition with or without bone formation in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:1654–1669.

- Beyzaei A, Francis J, Knight H, Simon DB, Finkelstein FO. Metabolic lung disease: diffuse metastatic pulmonary calcifications with progression to calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Adv Perit Dial 2007; 23:112–117.

- Conger JD, Hammond WS, Alfrey AC, Contiguglia SR, Stanford RE, Huffer WE. Pulmonary calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Clinical and pathologic studies. Ann Intern Med 1975; 83:330–336.

- Belem LC, Zanetti G, Souza AS Jr, et al. Metastatic pulmonary calcification: state-of-the-art review focused on imaging findings. Respir Med 2014; 108:668–676.

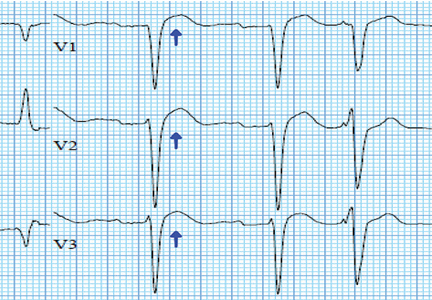

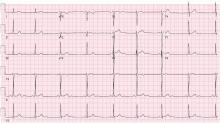

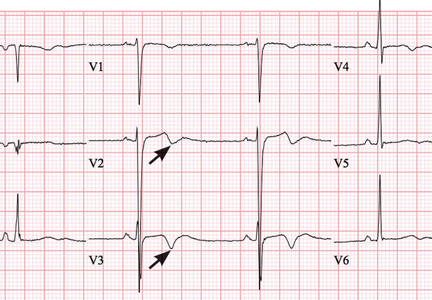

Pseudo-Wellens syndrome after heavy marijuana use

A 22-year old man with no cardiac history presented to our emergency department after 5 days of dyspnea, cough, vomiting, and sharp intermittent epigastric pain. He used marijuana chronically and had inhaled it in unusually high amounts for several days before the onset of his symptoms.

The physical examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic tests including a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipase level, urinalysis, and chest radiography showed no notable abnormalities. A urine drug screen revealed marijuana use.

Given this clinical picture, the question was whether cardiac catheterization was needed. Our young, previously healthy patient lacked risk factors for coronary artery disease and did not present with chest pain. Though dyspnea and epigastric pain are angina equivalents, he did not have the profile of patients commonly presenting with angina. Further, acute marijuana intoxication has been reported to be associated with reversible changes affecting the P and T waves and ST segments.1,2 The likelihood of critical occlusion of the left anterior descending artery in this patient was deemed low.

PSEUDO-WELLENS SYNDROME

Wellens syndrome is characterized by biphasic or deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 and V3, normal precordial R-wave progression, and the absence of pathologic Q waves, in addition to a history of angina and minimal or no elevation of cardiac enzymes in a patient with or without ongoing chest pain.3,4 This ominous syndrome is associated with critical occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery whose natural history is anterior myocardial infarction in the next few days. Stress testing is contraindicated, and urgent catheterization is warranted to prevent progression to myocardial infarction, even in patients without known heart disease or multiple cardiac risk factors.5

This case shows that acute marijuana intoxication may present with symptoms typical of Wellens syndrome. Because Wellens syndrome is considered highly specific for impending anterior myocardial infarction, urgent cardiac catheterization typically would be recommended. In this age of increasing use and legalization of marijuana, knowledge of the electrocardiographic findings associated with heavy marijuana use may prevent unnecessary cardiac catheterization procedures, especially in patients at low risk.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart 2000; 83:627–633.

- Bachs L, Morland H. Acute cardiovascular fatalities following cannabis use. Forensic Sci Int 2001; 124:200–203.

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1982; 103:730–736.

- Rhinehardt J, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of Wellens’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2002; 20:638–643.

- Mead NE, O’Keefe KP. Wellen’s syndrome: an ominous EKG pattern. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2009; 2:206–208.

A 22-year old man with no cardiac history presented to our emergency department after 5 days of dyspnea, cough, vomiting, and sharp intermittent epigastric pain. He used marijuana chronically and had inhaled it in unusually high amounts for several days before the onset of his symptoms.

The physical examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic tests including a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipase level, urinalysis, and chest radiography showed no notable abnormalities. A urine drug screen revealed marijuana use.

Given this clinical picture, the question was whether cardiac catheterization was needed. Our young, previously healthy patient lacked risk factors for coronary artery disease and did not present with chest pain. Though dyspnea and epigastric pain are angina equivalents, he did not have the profile of patients commonly presenting with angina. Further, acute marijuana intoxication has been reported to be associated with reversible changes affecting the P and T waves and ST segments.1,2 The likelihood of critical occlusion of the left anterior descending artery in this patient was deemed low.

PSEUDO-WELLENS SYNDROME

Wellens syndrome is characterized by biphasic or deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 and V3, normal precordial R-wave progression, and the absence of pathologic Q waves, in addition to a history of angina and minimal or no elevation of cardiac enzymes in a patient with or without ongoing chest pain.3,4 This ominous syndrome is associated with critical occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery whose natural history is anterior myocardial infarction in the next few days. Stress testing is contraindicated, and urgent catheterization is warranted to prevent progression to myocardial infarction, even in patients without known heart disease or multiple cardiac risk factors.5

This case shows that acute marijuana intoxication may present with symptoms typical of Wellens syndrome. Because Wellens syndrome is considered highly specific for impending anterior myocardial infarction, urgent cardiac catheterization typically would be recommended. In this age of increasing use and legalization of marijuana, knowledge of the electrocardiographic findings associated with heavy marijuana use may prevent unnecessary cardiac catheterization procedures, especially in patients at low risk.

A 22-year old man with no cardiac history presented to our emergency department after 5 days of dyspnea, cough, vomiting, and sharp intermittent epigastric pain. He used marijuana chronically and had inhaled it in unusually high amounts for several days before the onset of his symptoms.

The physical examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic tests including a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipase level, urinalysis, and chest radiography showed no notable abnormalities. A urine drug screen revealed marijuana use.

Given this clinical picture, the question was whether cardiac catheterization was needed. Our young, previously healthy patient lacked risk factors for coronary artery disease and did not present with chest pain. Though dyspnea and epigastric pain are angina equivalents, he did not have the profile of patients commonly presenting with angina. Further, acute marijuana intoxication has been reported to be associated with reversible changes affecting the P and T waves and ST segments.1,2 The likelihood of critical occlusion of the left anterior descending artery in this patient was deemed low.

PSEUDO-WELLENS SYNDROME

Wellens syndrome is characterized by biphasic or deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 and V3, normal precordial R-wave progression, and the absence of pathologic Q waves, in addition to a history of angina and minimal or no elevation of cardiac enzymes in a patient with or without ongoing chest pain.3,4 This ominous syndrome is associated with critical occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery whose natural history is anterior myocardial infarction in the next few days. Stress testing is contraindicated, and urgent catheterization is warranted to prevent progression to myocardial infarction, even in patients without known heart disease or multiple cardiac risk factors.5

This case shows that acute marijuana intoxication may present with symptoms typical of Wellens syndrome. Because Wellens syndrome is considered highly specific for impending anterior myocardial infarction, urgent cardiac catheterization typically would be recommended. In this age of increasing use and legalization of marijuana, knowledge of the electrocardiographic findings associated with heavy marijuana use may prevent unnecessary cardiac catheterization procedures, especially in patients at low risk.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart 2000; 83:627–633.

- Bachs L, Morland H. Acute cardiovascular fatalities following cannabis use. Forensic Sci Int 2001; 124:200–203.

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1982; 103:730–736.

- Rhinehardt J, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of Wellens’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2002; 20:638–643.

- Mead NE, O’Keefe KP. Wellen’s syndrome: an ominous EKG pattern. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2009; 2:206–208.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart 2000; 83:627–633.

- Bachs L, Morland H. Acute cardiovascular fatalities following cannabis use. Forensic Sci Int 2001; 124:200–203.

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1982; 103:730–736.

- Rhinehardt J, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of Wellens’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2002; 20:638–643.

- Mead NE, O’Keefe KP. Wellen’s syndrome: an ominous EKG pattern. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2009; 2:206–208.

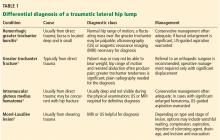

A lump on the hip

A 42-year-old man presented with a lump on the side of his left hip, which had developed after he fell on his hip while playing basketball about 2 weeks earlier. He was able to continue playing and finished the game. After the game he noticed a lump, which rapidly increased in size. Significant bruising developed afterwards, and the area was mildly painful. The lump did not interfere with his daily activities, but it was annoying.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morel-Lavallée lesion is an uncommon condition resulting from shearing trauma and collection of fluid in the space between deep fatty tissue and superficial fascia.6 It is usually the result of severe trauma, as in a motor vehicle accident, but it can also result from sports-related trauma, as in our patient.6–8 Lateral hip, gluteal, and sacral regions are the most common locations for Morel-Lavallée lesions and are often associated with an underlying fracture.6,9

Morel-Lavallée lesions usually develop hours or days after trauma, although they may develop weeks or even months later.2 Symptoms include bulging, pain, and loss of cutaneous sensation over the affected area. Although ultrasonography can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging.6,10 If there is concern for fracture, plain radiography should be performed.

Mellado and Bencardino classified Morel-Lavallée lesions into 6 types based on their morphology, presence or absence of a capsule, signal behavior on MRI, and enhancement pattern.10 The exact rate of infection in patients with Morel-Lavallée lesions is unknown; however, the risk of infection seems to be highest after surgical intervention or aspiration.5,6

Another potential complication is fluid reaccumulation, which most often occurs with large lesions (> 50 mL) and lesions with a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule.5 Large lesions can compromise adjacent neurovascular structures, particularly in the extremities.5 Potential consequences include dermal necrosis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.5

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Aspiration of a fluid-filled mass is useful in both diagnosis and management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Treatment includes watchful waiting; compression and pressure wraps; injection of a sclerosing agent (eg, doxycyline, alcohol); needle aspiration; percutaneous drainage with debridement, irrigation, and suction; and incision and evacuation.6

The approach to treatment depends on the stage of the lesion and whether an underlying fracture is present. Depending on the amount of blood and lymphatic products and the acuity of the collected fluid (hours to days post-trauma), aspiration with a large-bore needle (eg, 14 to 22 gauge) may or may not be successful.7 In general, traumatic serosanguinous fluid collections are less painful and resolve faster than well-formed coagulated hematomas.

Patients who have a large lesion, significant pain, or decreased range of motion should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Our patient was managed conservatively, and his symptoms completely resolved in 2 months.

- Ahmad Z, Tibrewal S, Waters G, Nolan J. Solitary amyloidoma related to THA. Orthopedics 2013; 36:e971–e973.

- Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:33–37.

- Price MD, Busconi BD, McMillan S. Proximal femur fractures. In: Miller MD, Sanders TG, eds. Presentation, Imaging and Treatment of Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:365–376.

- Stanton MC, Maloney MD, Dehaven KE, Giordano BD. Acute traumatic tear of gluteus medius and minimus tendons in a patient without antecedant peritrochanteric hip pain. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012; 3:84–88.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS, Mathern S, Bravman JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:417–422.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014; 21:35–43.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS. Ankle Morel-Lavallée lesion in a recreational racquetball player. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Shmerling A, Bravman JT, Khodaee M. Morel-Lavallée lesion of the knee in a recreational frisbee player. Case Rep Orthop 2016; 2016:8723489.

- Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty 2014; 14:ic12.

- Mellado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005; 13:775–782.

A 42-year-old man presented with a lump on the side of his left hip, which had developed after he fell on his hip while playing basketball about 2 weeks earlier. He was able to continue playing and finished the game. After the game he noticed a lump, which rapidly increased in size. Significant bruising developed afterwards, and the area was mildly painful. The lump did not interfere with his daily activities, but it was annoying.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morel-Lavallée lesion is an uncommon condition resulting from shearing trauma and collection of fluid in the space between deep fatty tissue and superficial fascia.6 It is usually the result of severe trauma, as in a motor vehicle accident, but it can also result from sports-related trauma, as in our patient.6–8 Lateral hip, gluteal, and sacral regions are the most common locations for Morel-Lavallée lesions and are often associated with an underlying fracture.6,9

Morel-Lavallée lesions usually develop hours or days after trauma, although they may develop weeks or even months later.2 Symptoms include bulging, pain, and loss of cutaneous sensation over the affected area. Although ultrasonography can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging.6,10 If there is concern for fracture, plain radiography should be performed.

Mellado and Bencardino classified Morel-Lavallée lesions into 6 types based on their morphology, presence or absence of a capsule, signal behavior on MRI, and enhancement pattern.10 The exact rate of infection in patients with Morel-Lavallée lesions is unknown; however, the risk of infection seems to be highest after surgical intervention or aspiration.5,6

Another potential complication is fluid reaccumulation, which most often occurs with large lesions (> 50 mL) and lesions with a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule.5 Large lesions can compromise adjacent neurovascular structures, particularly in the extremities.5 Potential consequences include dermal necrosis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.5

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Aspiration of a fluid-filled mass is useful in both diagnosis and management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Treatment includes watchful waiting; compression and pressure wraps; injection of a sclerosing agent (eg, doxycyline, alcohol); needle aspiration; percutaneous drainage with debridement, irrigation, and suction; and incision and evacuation.6

The approach to treatment depends on the stage of the lesion and whether an underlying fracture is present. Depending on the amount of blood and lymphatic products and the acuity of the collected fluid (hours to days post-trauma), aspiration with a large-bore needle (eg, 14 to 22 gauge) may or may not be successful.7 In general, traumatic serosanguinous fluid collections are less painful and resolve faster than well-formed coagulated hematomas.

Patients who have a large lesion, significant pain, or decreased range of motion should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Our patient was managed conservatively, and his symptoms completely resolved in 2 months.

A 42-year-old man presented with a lump on the side of his left hip, which had developed after he fell on his hip while playing basketball about 2 weeks earlier. He was able to continue playing and finished the game. After the game he noticed a lump, which rapidly increased in size. Significant bruising developed afterwards, and the area was mildly painful. The lump did not interfere with his daily activities, but it was annoying.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morel-Lavallée lesion is an uncommon condition resulting from shearing trauma and collection of fluid in the space between deep fatty tissue and superficial fascia.6 It is usually the result of severe trauma, as in a motor vehicle accident, but it can also result from sports-related trauma, as in our patient.6–8 Lateral hip, gluteal, and sacral regions are the most common locations for Morel-Lavallée lesions and are often associated with an underlying fracture.6,9

Morel-Lavallée lesions usually develop hours or days after trauma, although they may develop weeks or even months later.2 Symptoms include bulging, pain, and loss of cutaneous sensation over the affected area. Although ultrasonography can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging.6,10 If there is concern for fracture, plain radiography should be performed.

Mellado and Bencardino classified Morel-Lavallée lesions into 6 types based on their morphology, presence or absence of a capsule, signal behavior on MRI, and enhancement pattern.10 The exact rate of infection in patients with Morel-Lavallée lesions is unknown; however, the risk of infection seems to be highest after surgical intervention or aspiration.5,6

Another potential complication is fluid reaccumulation, which most often occurs with large lesions (> 50 mL) and lesions with a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule.5 Large lesions can compromise adjacent neurovascular structures, particularly in the extremities.5 Potential consequences include dermal necrosis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.5

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Aspiration of a fluid-filled mass is useful in both diagnosis and management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Treatment includes watchful waiting; compression and pressure wraps; injection of a sclerosing agent (eg, doxycyline, alcohol); needle aspiration; percutaneous drainage with debridement, irrigation, and suction; and incision and evacuation.6

The approach to treatment depends on the stage of the lesion and whether an underlying fracture is present. Depending on the amount of blood and lymphatic products and the acuity of the collected fluid (hours to days post-trauma), aspiration with a large-bore needle (eg, 14 to 22 gauge) may or may not be successful.7 In general, traumatic serosanguinous fluid collections are less painful and resolve faster than well-formed coagulated hematomas.

Patients who have a large lesion, significant pain, or decreased range of motion should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Our patient was managed conservatively, and his symptoms completely resolved in 2 months.

- Ahmad Z, Tibrewal S, Waters G, Nolan J. Solitary amyloidoma related to THA. Orthopedics 2013; 36:e971–e973.

- Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:33–37.

- Price MD, Busconi BD, McMillan S. Proximal femur fractures. In: Miller MD, Sanders TG, eds. Presentation, Imaging and Treatment of Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:365–376.

- Stanton MC, Maloney MD, Dehaven KE, Giordano BD. Acute traumatic tear of gluteus medius and minimus tendons in a patient without antecedant peritrochanteric hip pain. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012; 3:84–88.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS, Mathern S, Bravman JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:417–422.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014; 21:35–43.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS. Ankle Morel-Lavallée lesion in a recreational racquetball player. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Shmerling A, Bravman JT, Khodaee M. Morel-Lavallée lesion of the knee in a recreational frisbee player. Case Rep Orthop 2016; 2016:8723489.

- Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty 2014; 14:ic12.

- Mellado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005; 13:775–782.

- Ahmad Z, Tibrewal S, Waters G, Nolan J. Solitary amyloidoma related to THA. Orthopedics 2013; 36:e971–e973.

- Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:33–37.

- Price MD, Busconi BD, McMillan S. Proximal femur fractures. In: Miller MD, Sanders TG, eds. Presentation, Imaging and Treatment of Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:365–376.

- Stanton MC, Maloney MD, Dehaven KE, Giordano BD. Acute traumatic tear of gluteus medius and minimus tendons in a patient without antecedant peritrochanteric hip pain. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012; 3:84–88.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS, Mathern S, Bravman JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:417–422.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014; 21:35–43.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS. Ankle Morel-Lavallée lesion in a recreational racquetball player. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Shmerling A, Bravman JT, Khodaee M. Morel-Lavallée lesion of the knee in a recreational frisbee player. Case Rep Orthop 2016; 2016:8723489.

- Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty 2014; 14:ic12.

- Mellado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005; 13:775–782.

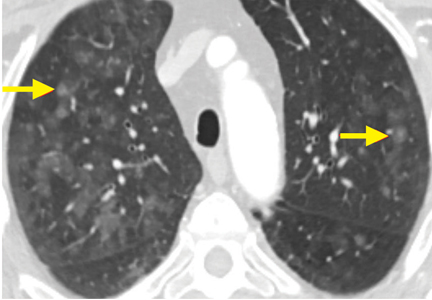

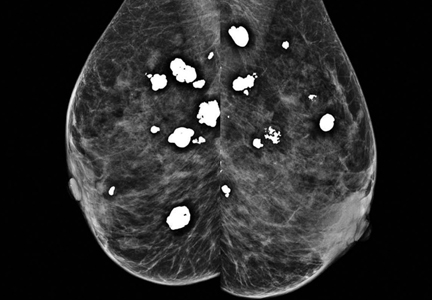

Breast calcifications mimicking pulmonary nodules

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.