User login

Secondary syphilis

Results of laboratory testing included a positive reactive syphilis immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme immunoassay and a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test (titer 1:256). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing was negative, and serologic testing demonstrated prior immunization to hepatitis B virus. Given the clinical presentation and laboratory findings, secondary syphilis was considered the most probable diagnosis.

The patient was treated with benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly.

SYPHILIS: A REEMERGING CONDITION

Epidemiology

The rate of reported primary and secondary syphilis cases in the United States has risen since 2001.1 Most cases occur in men who have sex with men.1 Additional risk factors include condomless intercourse and drug use.2

Signs and symptoms of the 3 stages

Primary syphilis begins 2 to 3 weeks after inoculation of a mucosal surface.3 This stage is marked by one or more painless chancres and, in some cases, local nontender lymphadenopathy.3,4 Secondary syphilis presents 4 to 8 weeks later with systemic symptoms including rash, classically involving the palms or soles, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, fever, and weight loss.2,3 Untreated primary and secondary syphilis may progress to latent or asymptomatic disease.5

Tertiary syphilis, defined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as gummas or cardiovascular syphilis, occurs 15 to 30 years after an untreated exposure.4,6 Neurosyphilis can present at any stage of the disease.6

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of syphilis involves a nontreponemal test such as RPR or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) to screen for disease, followed by a treponemal antibody test such as fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, or syphilis IgG to confirm the diagnosis.5 There is no screening test for tertiary disease in patients previously diagnosed with primary or secondary syphilis, but a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is recommended if neurologic or ocular manifestations are present.6

Treatment

Treatment of primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is a single dose of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G given intramuscularly.7 The treatment of late latent and tertiary syphilis is less well defined by the current literature but generally includes penicillin.7

Patients with primary and secondary syphilis undergo serologic and clinical evaluation at 6 and 12 months to be assessed for treatment failure or reinfection.6 Patients with latent disease require serologic follow-up at 6, 12, and 24 months.6 Additionally, CSF analysis should be done if baseline high titers do not fall within 12 to 24 months of treatment or if symptoms suggest syphilis.6 Patients with neurosyphilis often require CSF evaluation every 6 months.6 Follow-up for patients with tertiary syphilis is less well defined.

Patients coinfected with HIV have special needs and considerations, as outlined in the CDC’s 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.6

Sexual contacts of patients with syphilis deserve evaluation. Exposure within 90 days of a patient’s diagnosis with primary, secondary, or latent disease requires treatment regardless of the results of serologic testing.6 Persons exposed more than 90 days before diagnosis may undergo serologic testing; however, if results are not immediately available or follow-up is unlikely, the individual should be treated for early syphilis.6 If serologic testing results are negative, no treatment is required.6

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15. Accessed May 22, 2017.

- Nyatsanza F, Tipple C. Syphilis: presentations in general medicine. Clin Med (Lond) 2016; 16:184–188.

- French P. Syphilis. BMJ 2007; 334:143–147. Erratum in: BMJ 2007; 335:0.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Appendix C1. Case definitions for nationally notifiable infectious diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/appendixc.htm. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Syphilis—CDC fact sheet (detailed). www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-Syphilis-detailed.htm. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Syphilis. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Clement ME, Okeke NL, Hicks CB. Treatment of syphilis: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312:1905–1917.

Results of laboratory testing included a positive reactive syphilis immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme immunoassay and a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test (titer 1:256). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing was negative, and serologic testing demonstrated prior immunization to hepatitis B virus. Given the clinical presentation and laboratory findings, secondary syphilis was considered the most probable diagnosis.

The patient was treated with benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly.

SYPHILIS: A REEMERGING CONDITION

Epidemiology

The rate of reported primary and secondary syphilis cases in the United States has risen since 2001.1 Most cases occur in men who have sex with men.1 Additional risk factors include condomless intercourse and drug use.2

Signs and symptoms of the 3 stages

Primary syphilis begins 2 to 3 weeks after inoculation of a mucosal surface.3 This stage is marked by one or more painless chancres and, in some cases, local nontender lymphadenopathy.3,4 Secondary syphilis presents 4 to 8 weeks later with systemic symptoms including rash, classically involving the palms or soles, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, fever, and weight loss.2,3 Untreated primary and secondary syphilis may progress to latent or asymptomatic disease.5

Tertiary syphilis, defined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as gummas or cardiovascular syphilis, occurs 15 to 30 years after an untreated exposure.4,6 Neurosyphilis can present at any stage of the disease.6

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of syphilis involves a nontreponemal test such as RPR or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) to screen for disease, followed by a treponemal antibody test such as fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, or syphilis IgG to confirm the diagnosis.5 There is no screening test for tertiary disease in patients previously diagnosed with primary or secondary syphilis, but a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is recommended if neurologic or ocular manifestations are present.6

Treatment

Treatment of primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is a single dose of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G given intramuscularly.7 The treatment of late latent and tertiary syphilis is less well defined by the current literature but generally includes penicillin.7

Patients with primary and secondary syphilis undergo serologic and clinical evaluation at 6 and 12 months to be assessed for treatment failure or reinfection.6 Patients with latent disease require serologic follow-up at 6, 12, and 24 months.6 Additionally, CSF analysis should be done if baseline high titers do not fall within 12 to 24 months of treatment or if symptoms suggest syphilis.6 Patients with neurosyphilis often require CSF evaluation every 6 months.6 Follow-up for patients with tertiary syphilis is less well defined.

Patients coinfected with HIV have special needs and considerations, as outlined in the CDC’s 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.6

Sexual contacts of patients with syphilis deserve evaluation. Exposure within 90 days of a patient’s diagnosis with primary, secondary, or latent disease requires treatment regardless of the results of serologic testing.6 Persons exposed more than 90 days before diagnosis may undergo serologic testing; however, if results are not immediately available or follow-up is unlikely, the individual should be treated for early syphilis.6 If serologic testing results are negative, no treatment is required.6

Results of laboratory testing included a positive reactive syphilis immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme immunoassay and a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test (titer 1:256). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing was negative, and serologic testing demonstrated prior immunization to hepatitis B virus. Given the clinical presentation and laboratory findings, secondary syphilis was considered the most probable diagnosis.

The patient was treated with benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly.

SYPHILIS: A REEMERGING CONDITION

Epidemiology

The rate of reported primary and secondary syphilis cases in the United States has risen since 2001.1 Most cases occur in men who have sex with men.1 Additional risk factors include condomless intercourse and drug use.2

Signs and symptoms of the 3 stages

Primary syphilis begins 2 to 3 weeks after inoculation of a mucosal surface.3 This stage is marked by one or more painless chancres and, in some cases, local nontender lymphadenopathy.3,4 Secondary syphilis presents 4 to 8 weeks later with systemic symptoms including rash, classically involving the palms or soles, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, fever, and weight loss.2,3 Untreated primary and secondary syphilis may progress to latent or asymptomatic disease.5

Tertiary syphilis, defined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as gummas or cardiovascular syphilis, occurs 15 to 30 years after an untreated exposure.4,6 Neurosyphilis can present at any stage of the disease.6

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of syphilis involves a nontreponemal test such as RPR or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) to screen for disease, followed by a treponemal antibody test such as fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, or syphilis IgG to confirm the diagnosis.5 There is no screening test for tertiary disease in patients previously diagnosed with primary or secondary syphilis, but a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is recommended if neurologic or ocular manifestations are present.6

Treatment

Treatment of primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is a single dose of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G given intramuscularly.7 The treatment of late latent and tertiary syphilis is less well defined by the current literature but generally includes penicillin.7

Patients with primary and secondary syphilis undergo serologic and clinical evaluation at 6 and 12 months to be assessed for treatment failure or reinfection.6 Patients with latent disease require serologic follow-up at 6, 12, and 24 months.6 Additionally, CSF analysis should be done if baseline high titers do not fall within 12 to 24 months of treatment or if symptoms suggest syphilis.6 Patients with neurosyphilis often require CSF evaluation every 6 months.6 Follow-up for patients with tertiary syphilis is less well defined.

Patients coinfected with HIV have special needs and considerations, as outlined in the CDC’s 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.6

Sexual contacts of patients with syphilis deserve evaluation. Exposure within 90 days of a patient’s diagnosis with primary, secondary, or latent disease requires treatment regardless of the results of serologic testing.6 Persons exposed more than 90 days before diagnosis may undergo serologic testing; however, if results are not immediately available or follow-up is unlikely, the individual should be treated for early syphilis.6 If serologic testing results are negative, no treatment is required.6

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15. Accessed May 22, 2017.

- Nyatsanza F, Tipple C. Syphilis: presentations in general medicine. Clin Med (Lond) 2016; 16:184–188.

- French P. Syphilis. BMJ 2007; 334:143–147. Erratum in: BMJ 2007; 335:0.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Appendix C1. Case definitions for nationally notifiable infectious diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/appendixc.htm. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Syphilis—CDC fact sheet (detailed). www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-Syphilis-detailed.htm. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Syphilis. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Clement ME, Okeke NL, Hicks CB. Treatment of syphilis: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312:1905–1917.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15. Accessed May 22, 2017.

- Nyatsanza F, Tipple C. Syphilis: presentations in general medicine. Clin Med (Lond) 2016; 16:184–188.

- French P. Syphilis. BMJ 2007; 334:143–147. Erratum in: BMJ 2007; 335:0.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Appendix C1. Case definitions for nationally notifiable infectious diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/appendixc.htm. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Syphilis—CDC fact sheet (detailed). www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-Syphilis-detailed.htm. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Syphilis. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Clement ME, Okeke NL, Hicks CB. Treatment of syphilis: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312:1905–1917.

A large mass in the right ventricle: Tumor or thrombus?

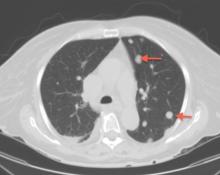

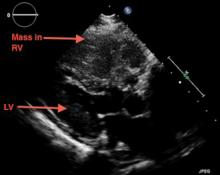

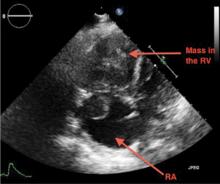

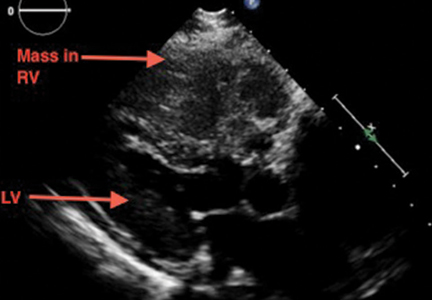

A 69-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease presented with a 1-month history of worsening episodic dyspnea, lower-extremity edema, and dizziness. Two months earlier, she had been diagnosed with poorly differentiated pelvic adnexal sarcoma associated with a mature teratoma of the left ovary, and she had undergone bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, and omentectomy.

Examination revealed tachypnea (23 breaths per minute) and bilateral pitting pedal edema. The neck veins were distended. There was no hepatomegaly. Results of laboratory testing were unremarkable.

EVALUATING A CARDIAC MASS

Thrombus, tumor, or vegetation?

If an intracardiac mass is discovered, we need to determine what it is.

Thrombosis is more likely if contrast echocardiography shows the mass has no stalk (thrombi almost never have a stalk), the atrial chamber is enlarged, cardiac output is low, there is stasis, the mass is avascular, and it responds to thrombolytic therapy. A giant organized thrombus can clinically mimic a tumor if it is immobile, is located close to the wall, and responds poorly to thrombolysis. A wall-motion abnormality adjacent to the mass, global hypokinesis, or a concomitant autoimmune condition such as lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome may also favor thrombosis.

Tumors in the heart are uncommon. The prevalence of primary cardiac tumors has been reported as 0.01% to 0.1% in autopsy studies. Metastases to the pericardium, myocardium, coronary arteries, or great vessels have been found at autopsy in 0.7% to 3.5% of the general population and in 9.1% of patients with known malignancy.1

Vegetations from infective endocarditis should also be considered early in the evaluation of an intracardiac mass. They can result from bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection. Vegetations are generally irregular in appearance, mobile, and attached to a valve. Left-sided valves are generally involved, and a larger mass may indicate fungal origin. Abscess from tuberculosis may need to be considered in the appropriate setting. Whenever feasible, tissue diagnosis is desirable.

Occasionally, there may be an inflammatory component to masses detected in the setting of autoimmune disease.

CT and MRI

If echocardiography cannot clearly distinguish whether the mass is a tumor or a thrombus, MRI with gadolinium contrast is useful. MRI is superior to CT in depicting anatomic details and does not involve radiation.

Cardiac CT is increasingly used when other imaging findings are equivocal or to study a calcified mass. CT with contrast carries a small risk of contrast-induced nephropathy and has lower soft-tissue and temporal resolution. CT without contrast can detect the mass and reveal calcifications within the mass, but contrast is needed to assess the vascularity of the tumor. New-generation CT with electrocardiographic gating nearly matches MRI imaging, and CT is preferred for patients with contraindications to MRI.

CT provides additional information on the global assessment of the chest, lung and vascular structures.2 Cardiac CT and MRI help in precise anatomic delineation, characterization, and preoperative planning of treatment of a large cardiac mass.

TYPES OF CARDIAC TUMORS

Metastases account for most cardiac tumors and are often from primary cancers of the lung, breast, skin, thyroid, and kidney.

Primary cardiac tumors are most often myxomas, which are benign and generally found in the atrial chamber, solitary, with a stalk attached to the area of the fossa ovalis. Other primary cardiac tumors include sarcomas, angiosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, papillary fibroelastomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, mesotheliomas, and rhabdomyomas.

TREATMENT OF CARDIAC TUMORS

For primary and secondary cardiac tumors, complete resection should be considered, provided there is no other organ involvement.3 For suspected lymphomas, image-guided biopsy should be performed before treatment.

For uncertain and diagnostically challenging cases, guided biopsy of the lesions using intracardiac echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography has been reported to be helpful.4

Most often, the workup and management of cardiac masses calls for a team involving an internist, cardiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, and vascular medicine specialist. Depending on the nature of the mass, the team may also include an oncologist, radiotherapist, and infectious disease specialist.

Because our patient had significant kidney disease, CT was done without contrast. However, it was not able to clearly delineate the mass in the right ventricle. Cardiac MRI was not performed. Biopsy with transesophageal or intracardiac echocardiographic guidance was not an option, as the patient’s condition was poor.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

The differential diagnosis of an intracardiac mass includes thrombus, benign or malignant tumors, and masses of infectious or inflammatory origin. While noninvasive imaging tests provide clues that can help narrow the differential diagnosis, tissue biopsy with histologic study is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. A team approach is paramount in managing cardiac masses.

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128:1790–1794.

- Exarhos DN, Tavernaraki EA, Kyratzi F, et al. Imaging of cardiac tumours and masses. Hospital Chronicles 2010; 5:1–9.

- Hoffmeier A, Sindermann JR, Scheld HH, Martens S. Cardiac tumors—diagnosis and surgical treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111:205–211.

- Park K-I, Kim MJ, Oh JK, et al. Intracardiac echocardiography to guide biopsy for two cases of intracardiac masses. Korean Circ J 2015; 45:165–168.

A 69-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease presented with a 1-month history of worsening episodic dyspnea, lower-extremity edema, and dizziness. Two months earlier, she had been diagnosed with poorly differentiated pelvic adnexal sarcoma associated with a mature teratoma of the left ovary, and she had undergone bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, and omentectomy.

Examination revealed tachypnea (23 breaths per minute) and bilateral pitting pedal edema. The neck veins were distended. There was no hepatomegaly. Results of laboratory testing were unremarkable.

EVALUATING A CARDIAC MASS

Thrombus, tumor, or vegetation?

If an intracardiac mass is discovered, we need to determine what it is.

Thrombosis is more likely if contrast echocardiography shows the mass has no stalk (thrombi almost never have a stalk), the atrial chamber is enlarged, cardiac output is low, there is stasis, the mass is avascular, and it responds to thrombolytic therapy. A giant organized thrombus can clinically mimic a tumor if it is immobile, is located close to the wall, and responds poorly to thrombolysis. A wall-motion abnormality adjacent to the mass, global hypokinesis, or a concomitant autoimmune condition such as lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome may also favor thrombosis.

Tumors in the heart are uncommon. The prevalence of primary cardiac tumors has been reported as 0.01% to 0.1% in autopsy studies. Metastases to the pericardium, myocardium, coronary arteries, or great vessels have been found at autopsy in 0.7% to 3.5% of the general population and in 9.1% of patients with known malignancy.1

Vegetations from infective endocarditis should also be considered early in the evaluation of an intracardiac mass. They can result from bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection. Vegetations are generally irregular in appearance, mobile, and attached to a valve. Left-sided valves are generally involved, and a larger mass may indicate fungal origin. Abscess from tuberculosis may need to be considered in the appropriate setting. Whenever feasible, tissue diagnosis is desirable.

Occasionally, there may be an inflammatory component to masses detected in the setting of autoimmune disease.

CT and MRI

If echocardiography cannot clearly distinguish whether the mass is a tumor or a thrombus, MRI with gadolinium contrast is useful. MRI is superior to CT in depicting anatomic details and does not involve radiation.

Cardiac CT is increasingly used when other imaging findings are equivocal or to study a calcified mass. CT with contrast carries a small risk of contrast-induced nephropathy and has lower soft-tissue and temporal resolution. CT without contrast can detect the mass and reveal calcifications within the mass, but contrast is needed to assess the vascularity of the tumor. New-generation CT with electrocardiographic gating nearly matches MRI imaging, and CT is preferred for patients with contraindications to MRI.

CT provides additional information on the global assessment of the chest, lung and vascular structures.2 Cardiac CT and MRI help in precise anatomic delineation, characterization, and preoperative planning of treatment of a large cardiac mass.

TYPES OF CARDIAC TUMORS

Metastases account for most cardiac tumors and are often from primary cancers of the lung, breast, skin, thyroid, and kidney.

Primary cardiac tumors are most often myxomas, which are benign and generally found in the atrial chamber, solitary, with a stalk attached to the area of the fossa ovalis. Other primary cardiac tumors include sarcomas, angiosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, papillary fibroelastomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, mesotheliomas, and rhabdomyomas.

TREATMENT OF CARDIAC TUMORS

For primary and secondary cardiac tumors, complete resection should be considered, provided there is no other organ involvement.3 For suspected lymphomas, image-guided biopsy should be performed before treatment.

For uncertain and diagnostically challenging cases, guided biopsy of the lesions using intracardiac echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography has been reported to be helpful.4

Most often, the workup and management of cardiac masses calls for a team involving an internist, cardiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, and vascular medicine specialist. Depending on the nature of the mass, the team may also include an oncologist, radiotherapist, and infectious disease specialist.

Because our patient had significant kidney disease, CT was done without contrast. However, it was not able to clearly delineate the mass in the right ventricle. Cardiac MRI was not performed. Biopsy with transesophageal or intracardiac echocardiographic guidance was not an option, as the patient’s condition was poor.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

The differential diagnosis of an intracardiac mass includes thrombus, benign or malignant tumors, and masses of infectious or inflammatory origin. While noninvasive imaging tests provide clues that can help narrow the differential diagnosis, tissue biopsy with histologic study is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. A team approach is paramount in managing cardiac masses.

A 69-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease presented with a 1-month history of worsening episodic dyspnea, lower-extremity edema, and dizziness. Two months earlier, she had been diagnosed with poorly differentiated pelvic adnexal sarcoma associated with a mature teratoma of the left ovary, and she had undergone bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, and omentectomy.

Examination revealed tachypnea (23 breaths per minute) and bilateral pitting pedal edema. The neck veins were distended. There was no hepatomegaly. Results of laboratory testing were unremarkable.

EVALUATING A CARDIAC MASS

Thrombus, tumor, or vegetation?

If an intracardiac mass is discovered, we need to determine what it is.

Thrombosis is more likely if contrast echocardiography shows the mass has no stalk (thrombi almost never have a stalk), the atrial chamber is enlarged, cardiac output is low, there is stasis, the mass is avascular, and it responds to thrombolytic therapy. A giant organized thrombus can clinically mimic a tumor if it is immobile, is located close to the wall, and responds poorly to thrombolysis. A wall-motion abnormality adjacent to the mass, global hypokinesis, or a concomitant autoimmune condition such as lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome may also favor thrombosis.

Tumors in the heart are uncommon. The prevalence of primary cardiac tumors has been reported as 0.01% to 0.1% in autopsy studies. Metastases to the pericardium, myocardium, coronary arteries, or great vessels have been found at autopsy in 0.7% to 3.5% of the general population and in 9.1% of patients with known malignancy.1

Vegetations from infective endocarditis should also be considered early in the evaluation of an intracardiac mass. They can result from bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection. Vegetations are generally irregular in appearance, mobile, and attached to a valve. Left-sided valves are generally involved, and a larger mass may indicate fungal origin. Abscess from tuberculosis may need to be considered in the appropriate setting. Whenever feasible, tissue diagnosis is desirable.

Occasionally, there may be an inflammatory component to masses detected in the setting of autoimmune disease.

CT and MRI

If echocardiography cannot clearly distinguish whether the mass is a tumor or a thrombus, MRI with gadolinium contrast is useful. MRI is superior to CT in depicting anatomic details and does not involve radiation.

Cardiac CT is increasingly used when other imaging findings are equivocal or to study a calcified mass. CT with contrast carries a small risk of contrast-induced nephropathy and has lower soft-tissue and temporal resolution. CT without contrast can detect the mass and reveal calcifications within the mass, but contrast is needed to assess the vascularity of the tumor. New-generation CT with electrocardiographic gating nearly matches MRI imaging, and CT is preferred for patients with contraindications to MRI.

CT provides additional information on the global assessment of the chest, lung and vascular structures.2 Cardiac CT and MRI help in precise anatomic delineation, characterization, and preoperative planning of treatment of a large cardiac mass.

TYPES OF CARDIAC TUMORS

Metastases account for most cardiac tumors and are often from primary cancers of the lung, breast, skin, thyroid, and kidney.

Primary cardiac tumors are most often myxomas, which are benign and generally found in the atrial chamber, solitary, with a stalk attached to the area of the fossa ovalis. Other primary cardiac tumors include sarcomas, angiosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, papillary fibroelastomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, mesotheliomas, and rhabdomyomas.

TREATMENT OF CARDIAC TUMORS

For primary and secondary cardiac tumors, complete resection should be considered, provided there is no other organ involvement.3 For suspected lymphomas, image-guided biopsy should be performed before treatment.

For uncertain and diagnostically challenging cases, guided biopsy of the lesions using intracardiac echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography has been reported to be helpful.4

Most often, the workup and management of cardiac masses calls for a team involving an internist, cardiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, and vascular medicine specialist. Depending on the nature of the mass, the team may also include an oncologist, radiotherapist, and infectious disease specialist.

Because our patient had significant kidney disease, CT was done without contrast. However, it was not able to clearly delineate the mass in the right ventricle. Cardiac MRI was not performed. Biopsy with transesophageal or intracardiac echocardiographic guidance was not an option, as the patient’s condition was poor.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

The differential diagnosis of an intracardiac mass includes thrombus, benign or malignant tumors, and masses of infectious or inflammatory origin. While noninvasive imaging tests provide clues that can help narrow the differential diagnosis, tissue biopsy with histologic study is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. A team approach is paramount in managing cardiac masses.

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128:1790–1794.

- Exarhos DN, Tavernaraki EA, Kyratzi F, et al. Imaging of cardiac tumours and masses. Hospital Chronicles 2010; 5:1–9.

- Hoffmeier A, Sindermann JR, Scheld HH, Martens S. Cardiac tumors—diagnosis and surgical treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111:205–211.

- Park K-I, Kim MJ, Oh JK, et al. Intracardiac echocardiography to guide biopsy for two cases of intracardiac masses. Korean Circ J 2015; 45:165–168.

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128:1790–1794.

- Exarhos DN, Tavernaraki EA, Kyratzi F, et al. Imaging of cardiac tumours and masses. Hospital Chronicles 2010; 5:1–9.

- Hoffmeier A, Sindermann JR, Scheld HH, Martens S. Cardiac tumors—diagnosis and surgical treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111:205–211.

- Park K-I, Kim MJ, Oh JK, et al. Intracardiac echocardiography to guide biopsy for two cases of intracardiac masses. Korean Circ J 2015; 45:165–168.

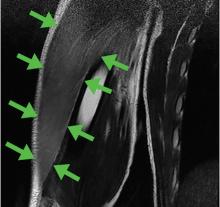

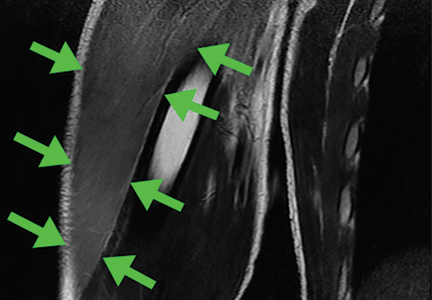

Swelling of both arms and chest after push-ups

A healthy 16-year-old boy presented with muscle pain and weakness in the chest and both arms after performing 50 push-ups daily for 3 days, and the symptoms did not seem to improve after 3 days.

EXERCISE-INDUCED RHABDOMYOLYSIS

Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the characteristic triad of myalgia (84%), muscle weakness (73%), and dark urine (80%), and 8.1% to 52% present with muscle swelling.1 Rhabdomyolysis may be caused by exercise,2 and risk factors include physical deconditioning, high ambient temperature, high humidity, impaired sweating (due to anticholinergic drugs), sickle cell trait, and hypokalemia from sweating.2 Pain and swelling of the affected focal muscles is the chief complaint.3

Although acute renal failure in exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare, failure to recognize rhabdomyolysis can cause diagnostic delay and inappropriate treatment.4

In healthy people, exercise-induced muscle damage begins to resolve within 1 to 3 days.5,6 Physicians should suspect exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged muscle swelling and tenderness in affected muscles that lasts longer than expected.7

- Nance JR, Mammen AL. Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51:793–810.

- Sayers SP, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002; 1:59–60.

- Have L, Drouet A. Isolated exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis of brachialis and brachioradialis muscles: an atypical clinical case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54:525–529.

- Keah SH, Chng K. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure after strenuous push-ups. Malays Fam Physician 2009; 4:37–39.

- Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:953–961.

- Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev 2005; 11:64–85.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J (2013) 2014; 97:22–24.

A healthy 16-year-old boy presented with muscle pain and weakness in the chest and both arms after performing 50 push-ups daily for 3 days, and the symptoms did not seem to improve after 3 days.

EXERCISE-INDUCED RHABDOMYOLYSIS

Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the characteristic triad of myalgia (84%), muscle weakness (73%), and dark urine (80%), and 8.1% to 52% present with muscle swelling.1 Rhabdomyolysis may be caused by exercise,2 and risk factors include physical deconditioning, high ambient temperature, high humidity, impaired sweating (due to anticholinergic drugs), sickle cell trait, and hypokalemia from sweating.2 Pain and swelling of the affected focal muscles is the chief complaint.3

Although acute renal failure in exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare, failure to recognize rhabdomyolysis can cause diagnostic delay and inappropriate treatment.4

In healthy people, exercise-induced muscle damage begins to resolve within 1 to 3 days.5,6 Physicians should suspect exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged muscle swelling and tenderness in affected muscles that lasts longer than expected.7

A healthy 16-year-old boy presented with muscle pain and weakness in the chest and both arms after performing 50 push-ups daily for 3 days, and the symptoms did not seem to improve after 3 days.

EXERCISE-INDUCED RHABDOMYOLYSIS

Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the characteristic triad of myalgia (84%), muscle weakness (73%), and dark urine (80%), and 8.1% to 52% present with muscle swelling.1 Rhabdomyolysis may be caused by exercise,2 and risk factors include physical deconditioning, high ambient temperature, high humidity, impaired sweating (due to anticholinergic drugs), sickle cell trait, and hypokalemia from sweating.2 Pain and swelling of the affected focal muscles is the chief complaint.3

Although acute renal failure in exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare, failure to recognize rhabdomyolysis can cause diagnostic delay and inappropriate treatment.4

In healthy people, exercise-induced muscle damage begins to resolve within 1 to 3 days.5,6 Physicians should suspect exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged muscle swelling and tenderness in affected muscles that lasts longer than expected.7

- Nance JR, Mammen AL. Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51:793–810.

- Sayers SP, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002; 1:59–60.

- Have L, Drouet A. Isolated exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis of brachialis and brachioradialis muscles: an atypical clinical case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54:525–529.

- Keah SH, Chng K. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure after strenuous push-ups. Malays Fam Physician 2009; 4:37–39.

- Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:953–961.

- Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev 2005; 11:64–85.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J (2013) 2014; 97:22–24.

- Nance JR, Mammen AL. Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51:793–810.

- Sayers SP, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002; 1:59–60.

- Have L, Drouet A. Isolated exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis of brachialis and brachioradialis muscles: an atypical clinical case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54:525–529.

- Keah SH, Chng K. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure after strenuous push-ups. Malays Fam Physician 2009; 4:37–39.

- Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:953–961.

- Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev 2005; 11:64–85.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J (2013) 2014; 97:22–24.

Black hairy tongue cured concurrently with respiratory infection

A 54-year-old female smoker was admitted to the hospital for fever and respiratory infection. On the day of admission, she reported lesions of the oral mucosa for the past several months. She denied taking any medications recently.

Physical examination showed brownish papillary lesions spread across the dorsum of the tongue; the lesions were a darker shade proximally (Figure 1), leading to the diagnosis of black hairy tongue. Hygienic measures were recommended, with other treatment options to be considered later, if necessary. Of note, during her 1-week hospital stay, she was treated with levofloxacin for the respiratory infection, and she did not smoke during this period. One week after her admission, the lesions had disappeared (Figure 2).

LINGUA VILLOSA NIGRA

Black hairy tongue (lingua villosa nigra) is a rare but benign condition caused by defective desquamation and reactive hypertrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue. Causes that have been proposed include medications, hyposalivation, poor oral hygiene, oxidizing mouthwashes (eg, hydrogen peroxide), alcohol, smoking, and infection.1

The differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans, oral hairy leukoplakia, oral candidiasis, pigmented fungiform papillae, Addison disease, and black staining over a normal tongue from bismuth or food colorings.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Visual inspection and a detailed history are often sufficient for diagnosis. The optimal treatment is unclear, but the condition can improve with hygienic measures alone, topical or oral retinoids,2 topical triamcinolone acetonide, salicylic acid, vitamin B complex, or antifungals. There are isolated cases in the literature in which improvement occurred with antibiotics, but their role is unclear.1 Rarely, surgical excision of the filliform papilla in black hairy tongue has been done for symptomatic relief and cosmetic purposes.3

While our patient presented with typical features of black hairy tongue, which resolved with hygienic measures and smoking cessation, we could not completely rule out the contribution of antibiotics given for the respiratory infection. It is important to keep this disease in mind to avoid unnecessary tests and to apply the most appropriate treatment according to the patient’s symptoms.

- Nakajima M, Mizooka M, Tazuma S. Black hairy tongue treated with oral antibiotics: a case report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:412–413.

- Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:10845–10850.

- Stringer LL, Zitella L. Hyperpigmentation of the tongue. J Adv Pract Oncol 2014; 5:71–72.

A 54-year-old female smoker was admitted to the hospital for fever and respiratory infection. On the day of admission, she reported lesions of the oral mucosa for the past several months. She denied taking any medications recently.

Physical examination showed brownish papillary lesions spread across the dorsum of the tongue; the lesions were a darker shade proximally (Figure 1), leading to the diagnosis of black hairy tongue. Hygienic measures were recommended, with other treatment options to be considered later, if necessary. Of note, during her 1-week hospital stay, she was treated with levofloxacin for the respiratory infection, and she did not smoke during this period. One week after her admission, the lesions had disappeared (Figure 2).

LINGUA VILLOSA NIGRA

Black hairy tongue (lingua villosa nigra) is a rare but benign condition caused by defective desquamation and reactive hypertrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue. Causes that have been proposed include medications, hyposalivation, poor oral hygiene, oxidizing mouthwashes (eg, hydrogen peroxide), alcohol, smoking, and infection.1

The differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans, oral hairy leukoplakia, oral candidiasis, pigmented fungiform papillae, Addison disease, and black staining over a normal tongue from bismuth or food colorings.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Visual inspection and a detailed history are often sufficient for diagnosis. The optimal treatment is unclear, but the condition can improve with hygienic measures alone, topical or oral retinoids,2 topical triamcinolone acetonide, salicylic acid, vitamin B complex, or antifungals. There are isolated cases in the literature in which improvement occurred with antibiotics, but their role is unclear.1 Rarely, surgical excision of the filliform papilla in black hairy tongue has been done for symptomatic relief and cosmetic purposes.3

While our patient presented with typical features of black hairy tongue, which resolved with hygienic measures and smoking cessation, we could not completely rule out the contribution of antibiotics given for the respiratory infection. It is important to keep this disease in mind to avoid unnecessary tests and to apply the most appropriate treatment according to the patient’s symptoms.

A 54-year-old female smoker was admitted to the hospital for fever and respiratory infection. On the day of admission, she reported lesions of the oral mucosa for the past several months. She denied taking any medications recently.

Physical examination showed brownish papillary lesions spread across the dorsum of the tongue; the lesions were a darker shade proximally (Figure 1), leading to the diagnosis of black hairy tongue. Hygienic measures were recommended, with other treatment options to be considered later, if necessary. Of note, during her 1-week hospital stay, she was treated with levofloxacin for the respiratory infection, and she did not smoke during this period. One week after her admission, the lesions had disappeared (Figure 2).

LINGUA VILLOSA NIGRA

Black hairy tongue (lingua villosa nigra) is a rare but benign condition caused by defective desquamation and reactive hypertrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue. Causes that have been proposed include medications, hyposalivation, poor oral hygiene, oxidizing mouthwashes (eg, hydrogen peroxide), alcohol, smoking, and infection.1

The differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans, oral hairy leukoplakia, oral candidiasis, pigmented fungiform papillae, Addison disease, and black staining over a normal tongue from bismuth or food colorings.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Visual inspection and a detailed history are often sufficient for diagnosis. The optimal treatment is unclear, but the condition can improve with hygienic measures alone, topical or oral retinoids,2 topical triamcinolone acetonide, salicylic acid, vitamin B complex, or antifungals. There are isolated cases in the literature in which improvement occurred with antibiotics, but their role is unclear.1 Rarely, surgical excision of the filliform papilla in black hairy tongue has been done for symptomatic relief and cosmetic purposes.3

While our patient presented with typical features of black hairy tongue, which resolved with hygienic measures and smoking cessation, we could not completely rule out the contribution of antibiotics given for the respiratory infection. It is important to keep this disease in mind to avoid unnecessary tests and to apply the most appropriate treatment according to the patient’s symptoms.

- Nakajima M, Mizooka M, Tazuma S. Black hairy tongue treated with oral antibiotics: a case report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:412–413.

- Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:10845–10850.

- Stringer LL, Zitella L. Hyperpigmentation of the tongue. J Adv Pract Oncol 2014; 5:71–72.

- Nakajima M, Mizooka M, Tazuma S. Black hairy tongue treated with oral antibiotics: a case report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:412–413.

- Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:10845–10850.

- Stringer LL, Zitella L. Hyperpigmentation of the tongue. J Adv Pract Oncol 2014; 5:71–72.

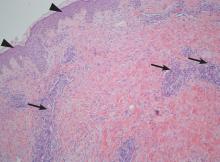

A 68-year-old man with a blue toe

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

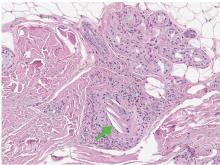

A dermatosis of pregnancy

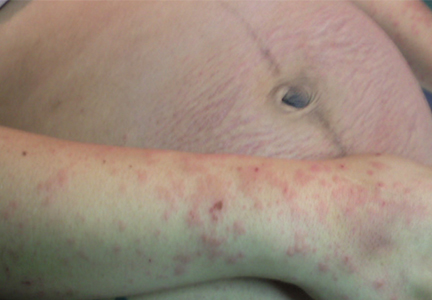

On the eighth day after giving birth to monochorionic twins, a 33-year-old woman presented with pruritic erythematous papules and plaques that started on the striae of the lower abdomen and spread rapidly to the thighs and upper limbs, sparing the umbilical region (Figure 1). Histologic examination of a specimen of the abdominal plaques showed moderate superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils (Figure 2), leading to the diagnosis of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Oral cetirizine 10 mg/day and topical methylprednisolone cream brought complete regression of the lesions within 1 month.

DERMATOSES OF PREGNANCY

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy—also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy1—is a specific dermatosis of pregnancy characterized by pruritic urticarial papules on abdominal striae that usually first appear during the latter portion of the third trimester or immediately postpartum. It is more frequent in primiparous women and does not represent a risk to the mother or fetus.2–4

The lesions tend to coalesce into plaques, spreading to the buttocks and proximal thighs. They then become more polymorphic and vesicular, with widespread nonurticated erythema and targetoid and eczematous lesions. Characteristically, the lesions spare the umbilical region. Their location within striae suggests that stretching of abdominal skin may damage the connective tissue, initiating an immune response with subsequent appearance of the eruption.2,4

The diagnosis is mainly clinical. In some cases, skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Histologic features are nonspecific and vary with the stage of disease, showing a superficial to mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils. At earlier stages, biopsy results can show a prominent dermal edema. In later stages, epidermal changes such as spongiosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis can occur.2

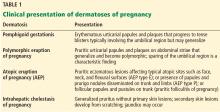

As an aid to diagnosis, Table 1 lists clinical differences between various dermatoses of pregnancy.

- Lawley TJ, Hertz KC, Wade TR, Ackerman AB, Katz SI. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. JAMA 1979; 241:1696–1699.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy—clues to diagnosis, fetal risk and therapy. Ann Dermatol 2011; 23:265–275.

- Rudolph C, Shornick J. Pregnancy dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, UK: Saunders; 2012:441–443.

- Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, Müllegger RR, Kerl H, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154:54–60.

On the eighth day after giving birth to monochorionic twins, a 33-year-old woman presented with pruritic erythematous papules and plaques that started on the striae of the lower abdomen and spread rapidly to the thighs and upper limbs, sparing the umbilical region (Figure 1). Histologic examination of a specimen of the abdominal plaques showed moderate superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils (Figure 2), leading to the diagnosis of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Oral cetirizine 10 mg/day and topical methylprednisolone cream brought complete regression of the lesions within 1 month.

DERMATOSES OF PREGNANCY

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy—also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy1—is a specific dermatosis of pregnancy characterized by pruritic urticarial papules on abdominal striae that usually first appear during the latter portion of the third trimester or immediately postpartum. It is more frequent in primiparous women and does not represent a risk to the mother or fetus.2–4

The lesions tend to coalesce into plaques, spreading to the buttocks and proximal thighs. They then become more polymorphic and vesicular, with widespread nonurticated erythema and targetoid and eczematous lesions. Characteristically, the lesions spare the umbilical region. Their location within striae suggests that stretching of abdominal skin may damage the connective tissue, initiating an immune response with subsequent appearance of the eruption.2,4

The diagnosis is mainly clinical. In some cases, skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Histologic features are nonspecific and vary with the stage of disease, showing a superficial to mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils. At earlier stages, biopsy results can show a prominent dermal edema. In later stages, epidermal changes such as spongiosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis can occur.2

As an aid to diagnosis, Table 1 lists clinical differences between various dermatoses of pregnancy.

On the eighth day after giving birth to monochorionic twins, a 33-year-old woman presented with pruritic erythematous papules and plaques that started on the striae of the lower abdomen and spread rapidly to the thighs and upper limbs, sparing the umbilical region (Figure 1). Histologic examination of a specimen of the abdominal plaques showed moderate superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils (Figure 2), leading to the diagnosis of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Oral cetirizine 10 mg/day and topical methylprednisolone cream brought complete regression of the lesions within 1 month.

DERMATOSES OF PREGNANCY

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy—also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy1—is a specific dermatosis of pregnancy characterized by pruritic urticarial papules on abdominal striae that usually first appear during the latter portion of the third trimester or immediately postpartum. It is more frequent in primiparous women and does not represent a risk to the mother or fetus.2–4

The lesions tend to coalesce into plaques, spreading to the buttocks and proximal thighs. They then become more polymorphic and vesicular, with widespread nonurticated erythema and targetoid and eczematous lesions. Characteristically, the lesions spare the umbilical region. Their location within striae suggests that stretching of abdominal skin may damage the connective tissue, initiating an immune response with subsequent appearance of the eruption.2,4

The diagnosis is mainly clinical. In some cases, skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Histologic features are nonspecific and vary with the stage of disease, showing a superficial to mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils. At earlier stages, biopsy results can show a prominent dermal edema. In later stages, epidermal changes such as spongiosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis can occur.2

As an aid to diagnosis, Table 1 lists clinical differences between various dermatoses of pregnancy.

- Lawley TJ, Hertz KC, Wade TR, Ackerman AB, Katz SI. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. JAMA 1979; 241:1696–1699.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy—clues to diagnosis, fetal risk and therapy. Ann Dermatol 2011; 23:265–275.

- Rudolph C, Shornick J. Pregnancy dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, UK: Saunders; 2012:441–443.

- Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, Müllegger RR, Kerl H, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154:54–60.

- Lawley TJ, Hertz KC, Wade TR, Ackerman AB, Katz SI. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. JAMA 1979; 241:1696–1699.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy—clues to diagnosis, fetal risk and therapy. Ann Dermatol 2011; 23:265–275.

- Rudolph C, Shornick J. Pregnancy dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, UK: Saunders; 2012:441–443.

- Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, Müllegger RR, Kerl H, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154:54–60.

A broken pacemaker lead in a 69-year-old woman

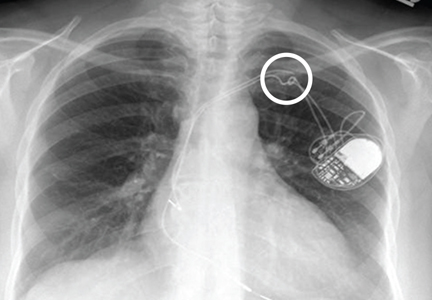

A 69-year-old woman presented with fatigue, cough, and lightheadedness. She had a history of atrial fibrillation and complete heart block, for which she had a pacemaker (dual-pacing, dual-sensing, dual-response, and rate-adaptive mode) inserted in 2005. Her heart rate was 30 beats per minute.

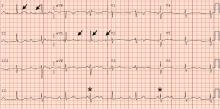

A chest radiograph showed a fractured right ventricular pacemaker lead (Figure 1). Electrocardiography showed sinus rhythm with a high-grade atrioventricular block (Figure 2). Pacemaker interrogation confirmed the diagnosis of lead fracture. A new lead was placed, and the old lead was abandoned.

HOW LEADS BREAK

The rate of lead fracture ranges from 0.1% to 4.2% per patient-year, and the annual failure rate increases progressively with time after implantation.1,2

Extrinsic pressure on the lead can eventually break it. This can happen between the first rib and clavicle, in “subclavian crush” injury, or with any anatomical abnormality that narrows the thoracic outlet. Typically, classic subclavian crush results from entrapment of the pacemaker leads by the subclavius muscle or the costoclavicular ligament as the lead follows the needle course of the antecedent access puncture of the subclavian vein. This results in intermittent flexing of the lead and potential lead fracture3 and was likely the cause of lead fracture in our patient.

The risk of fracture is higher in patients under the age of 50, those who perform intense physical activity, women, and patients with greater left ventricular ejection fraction.4,5 Certain leads are prone to fracture due to design flaws. One of these was the Medtronic Sprint Fidelis cardioverter defibrillator lead, which was recalled in 2007.5

DETECTING LEAD FRACTURE

Symptoms of lead fracture vary, depending on the patient’s pacemaker-dependency and on the degree of loss of capture (ie, the degree to which the heart fails to respond to the pacemaker’s signals), and may include lightheadedness, syncope, and extracardiac stimulation.

The electrical integrity of a lead can be tested by measuring the circuit impedance, which normally ranges from 300 to 1,000 ohms.6 An insulation failure results in very low impedance, while a disrupted circuit due to lead fracture commonly causes a sudden rather than gradual increase in impedance.6

Simple imaging studies such as chest radiography or fluoroscopy may establish the diagnosis of lead fracture. One should carefully trace every lead along its entire course and look for any conductor discontinuity, kinks, or sharp bends.6

REMOVE THE OLD LEAD, OR LEAVE IT IN PLACE?

The treatment for lead fracture is usually to put in a new lead, with or without extracting the old one.

In view of the potential complications of lead removal such as cardiac perforation or vascular tear, lead abandonment with placement of a new lead may be performed.7 There are no controlled clinical studies comparing lead abandonment vs lead extraction.8 However, extraction is currently recommended only in patients in whom the old lead causes life-threatening arrhythmias, interferes with the operation of implanted cardiac devices, interferes with radiation therapy or needed surgery, or, due to its design or failure, poses an immediate threat to the patient if left in place.7 Lead removal is reasonable in patients who require specific imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging with no available imaging alternative for the diagnosis.7

In our patient, a new lead was placed without removing the fractured lead, with no complications. Afterward, the patient’s heart rhythm was observed to be appropriately paced, and she was discharged home the following day.

- Alt E, Völker R, Blömer H. Lead fracture in pacemaker patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987; 35:101–104.

- Kleemann T, Becker T, Doenges K, et al. Annual rate of transvenous defibrillation lead defects in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators over a period of > 10 years. Circulation 2007; 115:2474–2480.

- Magney JE, Flynn DM, Parsons JA, et al. Anatomical mechanisms explaining damage to pacemaker leads, defibrillator leads, and failure of central venous catheters adjacent to the sternoclavicular joint. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1993; 16:445–457.

- Farwell D, Green MS, Lemery R, Gollob MH, Birnie DH. Accelerating risk of Fidelis lead fracture. Heart Rhythm 2008; 5:1375–1379.

- Morrison TB, Rea RF, Hodge DO, et al. Risk factors for implantable defibrillator lead fracture in a recalled and a nonrecalled lead. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2010; 21:671–677.

- Swerdlow CD, Ellenbogen KA. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads: design, diagnostics, and management. Circulation 2013; 128:2062–2071.

- Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL, et al; Heart Rhythm Society; American Heart Association. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management: this document was endorsed by the American Heart Association (AHA). Heart Rhythm 2009; 6:1085–1104.

- Maytin M, Epstein LM, Henrikson CA. Lead extraction is preferred for lead revisions and system upgrades: when less is more. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3:413–424.

A 69-year-old woman presented with fatigue, cough, and lightheadedness. She had a history of atrial fibrillation and complete heart block, for which she had a pacemaker (dual-pacing, dual-sensing, dual-response, and rate-adaptive mode) inserted in 2005. Her heart rate was 30 beats per minute.

A chest radiograph showed a fractured right ventricular pacemaker lead (Figure 1). Electrocardiography showed sinus rhythm with a high-grade atrioventricular block (Figure 2). Pacemaker interrogation confirmed the diagnosis of lead fracture. A new lead was placed, and the old lead was abandoned.

HOW LEADS BREAK

The rate of lead fracture ranges from 0.1% to 4.2% per patient-year, and the annual failure rate increases progressively with time after implantation.1,2

Extrinsic pressure on the lead can eventually break it. This can happen between the first rib and clavicle, in “subclavian crush” injury, or with any anatomical abnormality that narrows the thoracic outlet. Typically, classic subclavian crush results from entrapment of the pacemaker leads by the subclavius muscle or the costoclavicular ligament as the lead follows the needle course of the antecedent access puncture of the subclavian vein. This results in intermittent flexing of the lead and potential lead fracture3 and was likely the cause of lead fracture in our patient.

The risk of fracture is higher in patients under the age of 50, those who perform intense physical activity, women, and patients with greater left ventricular ejection fraction.4,5 Certain leads are prone to fracture due to design flaws. One of these was the Medtronic Sprint Fidelis cardioverter defibrillator lead, which was recalled in 2007.5

DETECTING LEAD FRACTURE

Symptoms of lead fracture vary, depending on the patient’s pacemaker-dependency and on the degree of loss of capture (ie, the degree to which the heart fails to respond to the pacemaker’s signals), and may include lightheadedness, syncope, and extracardiac stimulation.

The electrical integrity of a lead can be tested by measuring the circuit impedance, which normally ranges from 300 to 1,000 ohms.6 An insulation failure results in very low impedance, while a disrupted circuit due to lead fracture commonly causes a sudden rather than gradual increase in impedance.6

Simple imaging studies such as chest radiography or fluoroscopy may establish the diagnosis of lead fracture. One should carefully trace every lead along its entire course and look for any conductor discontinuity, kinks, or sharp bends.6

REMOVE THE OLD LEAD, OR LEAVE IT IN PLACE?

The treatment for lead fracture is usually to put in a new lead, with or without extracting the old one.

In view of the potential complications of lead removal such as cardiac perforation or vascular tear, lead abandonment with placement of a new lead may be performed.7 There are no controlled clinical studies comparing lead abandonment vs lead extraction.8 However, extraction is currently recommended only in patients in whom the old lead causes life-threatening arrhythmias, interferes with the operation of implanted cardiac devices, interferes with radiation therapy or needed surgery, or, due to its design or failure, poses an immediate threat to the patient if left in place.7 Lead removal is reasonable in patients who require specific imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging with no available imaging alternative for the diagnosis.7

In our patient, a new lead was placed without removing the fractured lead, with no complications. Afterward, the patient’s heart rhythm was observed to be appropriately paced, and she was discharged home the following day.

A 69-year-old woman presented with fatigue, cough, and lightheadedness. She had a history of atrial fibrillation and complete heart block, for which she had a pacemaker (dual-pacing, dual-sensing, dual-response, and rate-adaptive mode) inserted in 2005. Her heart rate was 30 beats per minute.

A chest radiograph showed a fractured right ventricular pacemaker lead (Figure 1). Electrocardiography showed sinus rhythm with a high-grade atrioventricular block (Figure 2). Pacemaker interrogation confirmed the diagnosis of lead fracture. A new lead was placed, and the old lead was abandoned.

HOW LEADS BREAK

The rate of lead fracture ranges from 0.1% to 4.2% per patient-year, and the annual failure rate increases progressively with time after implantation.1,2

Extrinsic pressure on the lead can eventually break it. This can happen between the first rib and clavicle, in “subclavian crush” injury, or with any anatomical abnormality that narrows the thoracic outlet. Typically, classic subclavian crush results from entrapment of the pacemaker leads by the subclavius muscle or the costoclavicular ligament as the lead follows the needle course of the antecedent access puncture of the subclavian vein. This results in intermittent flexing of the lead and potential lead fracture3 and was likely the cause of lead fracture in our patient.

The risk of fracture is higher in patients under the age of 50, those who perform intense physical activity, women, and patients with greater left ventricular ejection fraction.4,5 Certain leads are prone to fracture due to design flaws. One of these was the Medtronic Sprint Fidelis cardioverter defibrillator lead, which was recalled in 2007.5

DETECTING LEAD FRACTURE

Symptoms of lead fracture vary, depending on the patient’s pacemaker-dependency and on the degree of loss of capture (ie, the degree to which the heart fails to respond to the pacemaker’s signals), and may include lightheadedness, syncope, and extracardiac stimulation.

The electrical integrity of a lead can be tested by measuring the circuit impedance, which normally ranges from 300 to 1,000 ohms.6 An insulation failure results in very low impedance, while a disrupted circuit due to lead fracture commonly causes a sudden rather than gradual increase in impedance.6

Simple imaging studies such as chest radiography or fluoroscopy may establish the diagnosis of lead fracture. One should carefully trace every lead along its entire course and look for any conductor discontinuity, kinks, or sharp bends.6

REMOVE THE OLD LEAD, OR LEAVE IT IN PLACE?

The treatment for lead fracture is usually to put in a new lead, with or without extracting the old one.

In view of the potential complications of lead removal such as cardiac perforation or vascular tear, lead abandonment with placement of a new lead may be performed.7 There are no controlled clinical studies comparing lead abandonment vs lead extraction.8 However, extraction is currently recommended only in patients in whom the old lead causes life-threatening arrhythmias, interferes with the operation of implanted cardiac devices, interferes with radiation therapy or needed surgery, or, due to its design or failure, poses an immediate threat to the patient if left in place.7 Lead removal is reasonable in patients who require specific imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging with no available imaging alternative for the diagnosis.7

In our patient, a new lead was placed without removing the fractured lead, with no complications. Afterward, the patient’s heart rhythm was observed to be appropriately paced, and she was discharged home the following day.

- Alt E, Völker R, Blömer H. Lead fracture in pacemaker patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987; 35:101–104.

- Kleemann T, Becker T, Doenges K, et al. Annual rate of transvenous defibrillation lead defects in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators over a period of > 10 years. Circulation 2007; 115:2474–2480.

- Magney JE, Flynn DM, Parsons JA, et al. Anatomical mechanisms explaining damage to pacemaker leads, defibrillator leads, and failure of central venous catheters adjacent to the sternoclavicular joint. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1993; 16:445–457.

- Farwell D, Green MS, Lemery R, Gollob MH, Birnie DH. Accelerating risk of Fidelis lead fracture. Heart Rhythm 2008; 5:1375–1379.

- Morrison TB, Rea RF, Hodge DO, et al. Risk factors for implantable defibrillator lead fracture in a recalled and a nonrecalled lead. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2010; 21:671–677.

- Swerdlow CD, Ellenbogen KA. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads: design, diagnostics, and management. Circulation 2013; 128:2062–2071.

- Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL, et al; Heart Rhythm Society; American Heart Association. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management: this document was endorsed by the American Heart Association (AHA). Heart Rhythm 2009; 6:1085–1104.

- Maytin M, Epstein LM, Henrikson CA. Lead extraction is preferred for lead revisions and system upgrades: when less is more. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3:413–424.

- Alt E, Völker R, Blömer H. Lead fracture in pacemaker patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987; 35:101–104.

- Kleemann T, Becker T, Doenges K, et al. Annual rate of transvenous defibrillation lead defects in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators over a period of > 10 years. Circulation 2007; 115:2474–2480.

- Magney JE, Flynn DM, Parsons JA, et al. Anatomical mechanisms explaining damage to pacemaker leads, defibrillator leads, and failure of central venous catheters adjacent to the sternoclavicular joint. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1993; 16:445–457.

- Farwell D, Green MS, Lemery R, Gollob MH, Birnie DH. Accelerating risk of Fidelis lead fracture. Heart Rhythm 2008; 5:1375–1379.

- Morrison TB, Rea RF, Hodge DO, et al. Risk factors for implantable defibrillator lead fracture in a recalled and a nonrecalled lead. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2010; 21:671–677.

- Swerdlow CD, Ellenbogen KA. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads: design, diagnostics, and management. Circulation 2013; 128:2062–2071.