User login

Multi-cancer early detection liquid biopsy testing: A predictive genetic test not quite ready for prime time

CASE Patient inquires about new technology to detect cancer

A 51-year-old woman (para 2) presents to your clinic for a routine gynecology exam. She is up to date on her screening mammogram and Pap testing. She has her first colonoscopy scheduled for next month. She has a 10-year remote smoking history, but she stopped smoking in her late twenties. Her cousin was recently diagnosed with skin cancer, her father had prostate cancer and is now in remission, and her paternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer. She knows ovarian cancer does not have an effective screening test, and she recently heard on the news about a new blood test that can detect cancer before symptoms start. She would like to know more about this test. Could it replace her next Pap, mammogram, and future colonoscopies? She also wants to know—How can a simple blood test detect cancer?

The power of genomics in cancer care

Since the first human genome was sequenced in 2000, the power of genomics has been evident across many aspects of medicine, including cancer care.1 Whereas the first human genome to be sequenced took more than 10 years to sequence and cost over $1 billion, sequencing of your entire genome can now be obtained for less than $400—with results in a week.2

Genomics is now an integral part of cancer care, with results having implications for both cancer risk and prevention as well as more individualized treatment. For example, a healthy 42-year-old patient with a strong family history of breast cancer may undergo genetic testing and discover she has a mutation in the tumor suppression gene BRCA1, which carries a 39% to 58% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.3 By undergoing a risk-reducing bilateral salpingooophorectomy she will lower her ovarian cancer risk by up to 96%.4,5 A 67-year-old with a new diagnosis of stage III ovarian cancer and a BRCA2 mutation may be in remission for 5+ years due to her BRCA2 mutation, which makes her eligible for the use of the poly(ADPribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib.6 Genetic testing as illustrated above has led to decreased cancer-related mortality and prolonged survival.7 However, many women with such germline mutations are faced with difficult choices about surgical risk reduction, with the potential harms of early menopause and quality of life concerns. Having a test that does not just predict cancer risk but in fact quantifies that risk for the individual would greatly help in these decisions. Furthermore, more than 75% of ovarian cancers occur without a germline mutation.

Advances in genetic testing technology also have led to the ability to obtain genetic information from a simple blood test. For example, cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which is DNA fragments that are normally found to be circulating in the bloodstream, is routinely used as a screening tool for prenatal genetic testing to detect chromosomal abnormalities in the fetus.8 This technology relies on analyzing fetal free (non-cellular) DNA that is naturally found circulating in maternal blood. More recently, similar technology using cfDNA has been applied for the screening and characterization of certain cancers.9 This powerful technology can detect cancer before symptoms begin—all from a simple blood test, often referred to as a “liquid biopsy.” However, understanding the utility, supporting data, and target population for these tests is important before employing them as part of routine clinical practice.

Continue to: Current methods of cancer screening are limited...

Current methods of cancer screening are limited

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, with nearly 10 million cancer-related deaths annually, and it may surpass cardiovascular disease as the leading cause over the course of the century.10,11 Many cancer deaths are in part due to late-stage diagnosis, when the cancer has already metastasized.12 Early detection of cancer improves outcomes and survival rates, but it is often difficult to detect early due to the lack of early symptoms with many cancers, which can limit cancer screening and issues with access to care.13

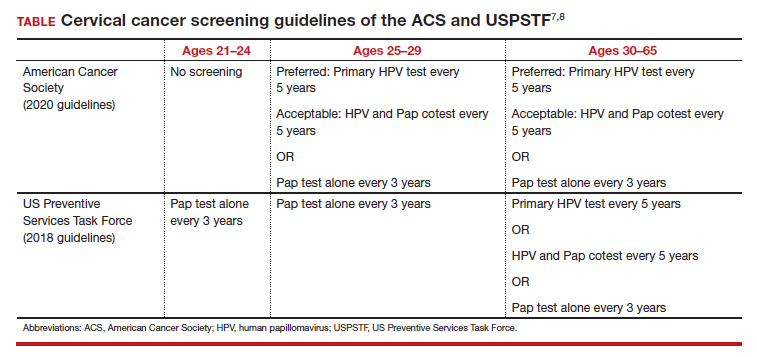

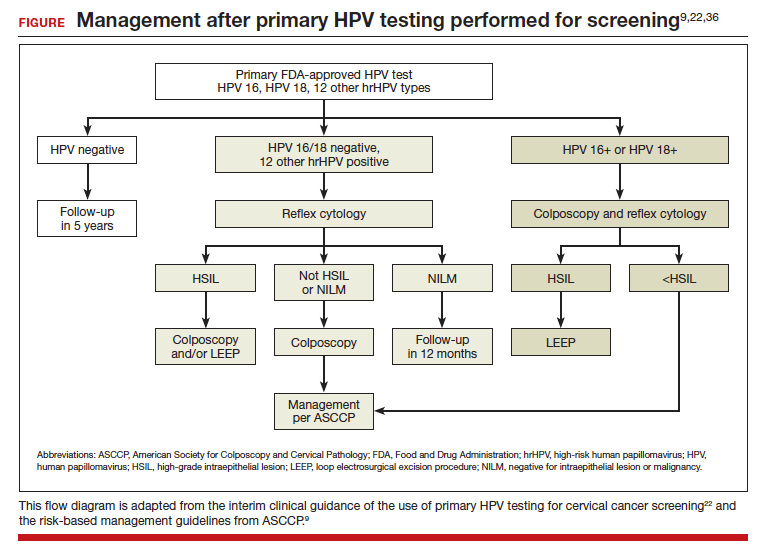

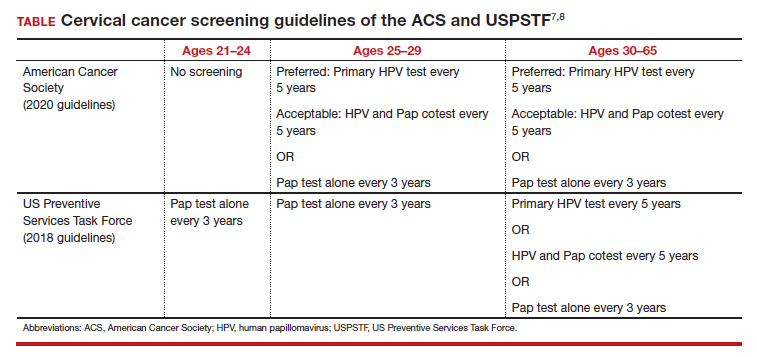

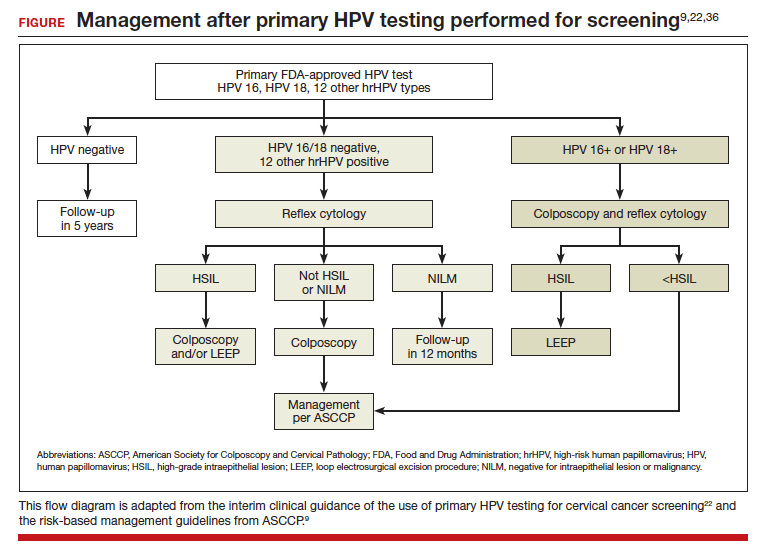

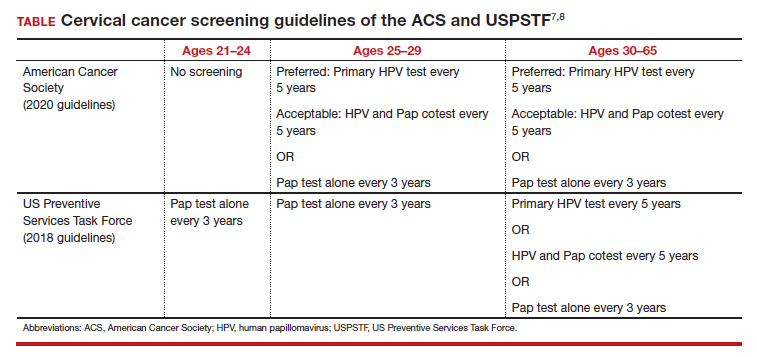

Currently, there are only 5 cancers: cervical, prostate, breast, colon, and lung (for high-risk adults) that are screened for in the general population (see "Cancer screening has helped save countless lives" at the end of this article).14 The Pap test to screen for cervical cancer, developed in the 1940s, has saved millions of women’s lives and reduced the mortality of cervical cancer by 70%.15 Coupled with the availability and implementation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, cervical cancer rates are decreasing at substantial rates.16 However, there are no validated screening tests for uterine cancer, the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, or ovarian cancer, the most lethal.

Screening tests for cervical, prostate, breast, colon, and lung cancer have helped save millions of lives; however, these tests also come with high false-positive rates and the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment. For example, half of women undergoing mammograms will receive a false-positive result over a 10-year time period,17 and up to 50% of men undergoing prostate cancer screening have a positive prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test result when they do not actually have prostate cancer.18 Additionally, the positive predictive value of the current standard-of-care screening tests can be as low as <5%. Most diagnoses of cancer are made from a surgical biopsy, but these types of procedures can be difficult depending on the location or size of the tumor.19

The liquid biopsy. Given the limitations of current cancer screening and diagnostic tests, there is a great need for a more sensitive test that also can detect cancer from multiple organ sites. Liquid biopsy-based biomarkers can include circulating tumor cells, exosomes, microRNAs, and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). With advances in next-generation sequencing, ctDNA techniques remain the most promising.20

Methylation-based MCED testing: A new way of cancer screening

Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) technology was developed to address the need for better cancer screening and has the potential to detect up to 50 cancers with a simple blood test. This new technology opens the possibility for early detection of multiple cancers before symptoms even begin. MCED testing is sometimes referred to as “GRAIL” testing, after the American biotechnology company that developed the first commercially available MCED test, called the Galleri test (Galleri, Menlo Park, California). Although other biotechnology companies are developing similar technology (Exact Sciences, Madison, Wisconsin, and Freenome, South San Francisco, California, for example), this is the first test of its kind available to the public.21

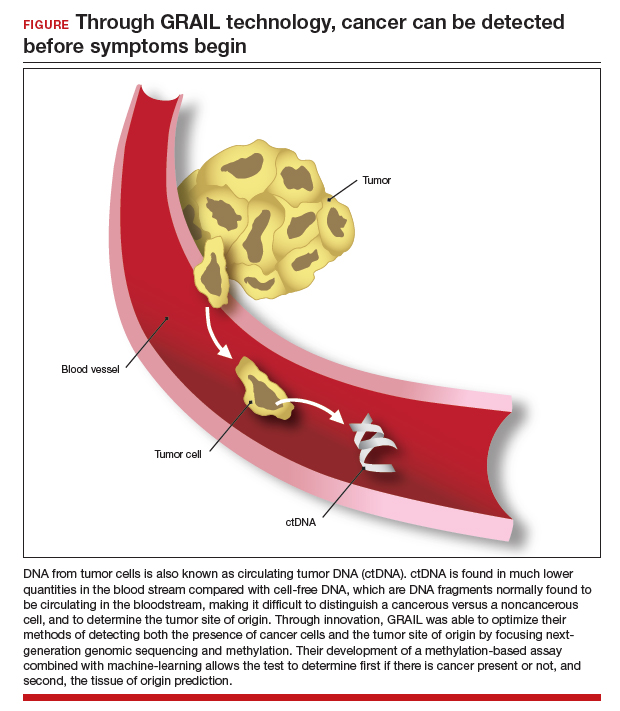

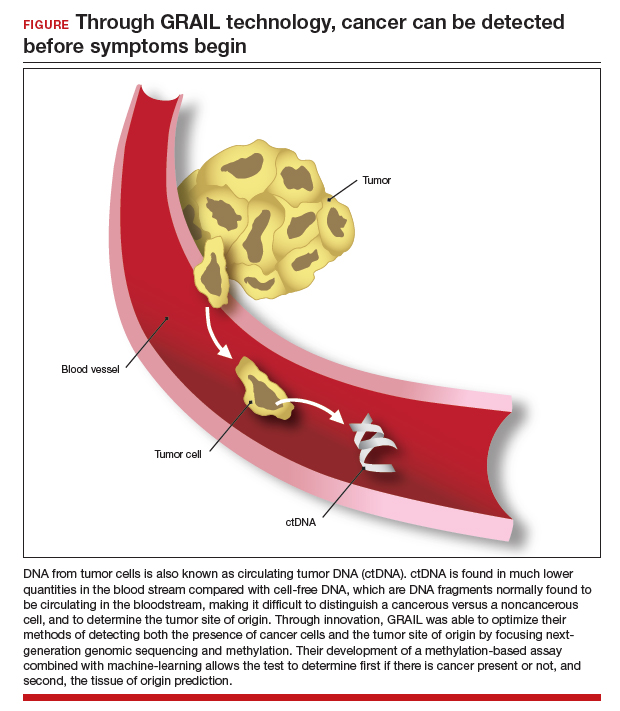

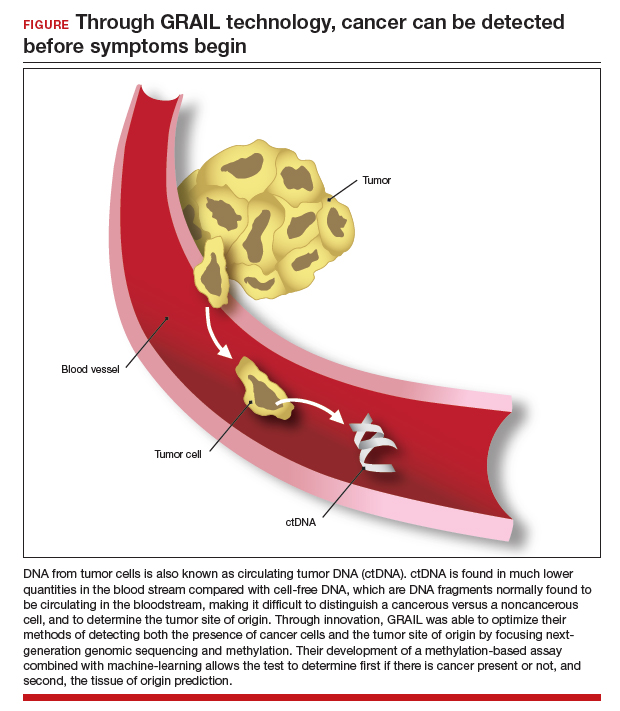

The MCED test works by detecting the cfDNA fragments that are released into the blood passively by necrotic or apoptotic cells or secreted actively from tumor cells. The DNA from tumor cells is also known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). CtDNA is found in much lower quantities in the blood stream compared with cfDNA from cells, making it difficult to distinguish a cancer versus a noncancer cell and to determine the tumor site of origin.22

Through innovation, the first example of detecting cancer through this method in fact came as a surprise result from an abnormal cfDNA test. A pregnant 37-yearold woman had a cfDNA result suggestive of aneuploidy for chromosomes 18 and 13; however, she gave birth to a normal male fetus. Shortly thereafter, a vaginal biopsy confirmed small-cell carcinoma with alterations in chromosomes 18 and 13.23 GRAIL testing for this patient was subsequently able to optimize their methods of detecting both the presence of cancer cells and the tumor site of origin by utilizing next-generation genomic sequencing and methylation. Their development of a methylation-based assay combined with 46 machine-learning allowed the test to determine, first, if there is cancer present or not, and second, the tissue of origin prediction. It is important to note that these tests are meant to be used in addition to standard-of-care screening tests, not as an alternative, and this is emphasized throughout the company’s website and the medical literature.24

Continue to: The process to develop and validate GRAIL’s blood-based cancer screening test...

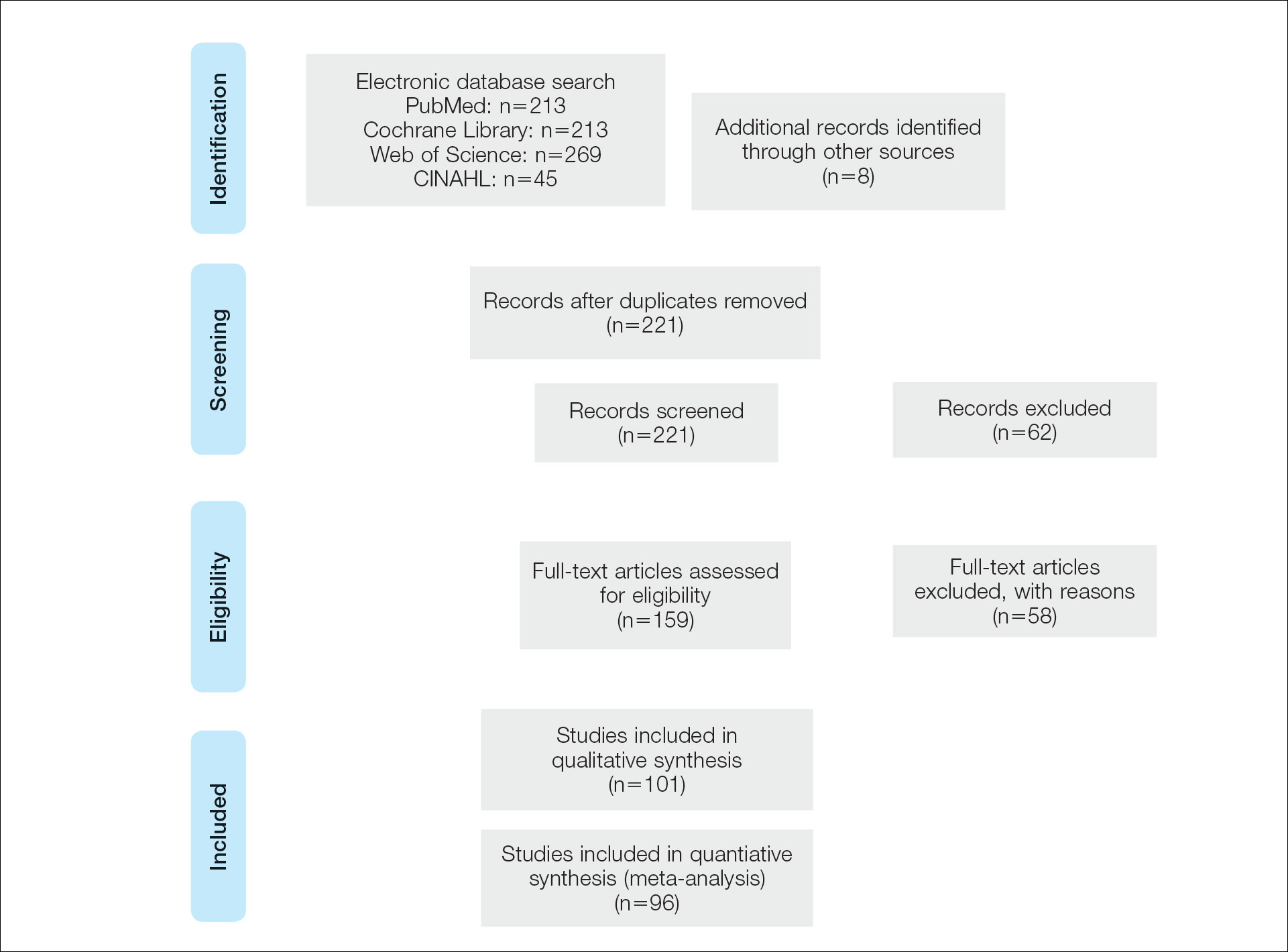

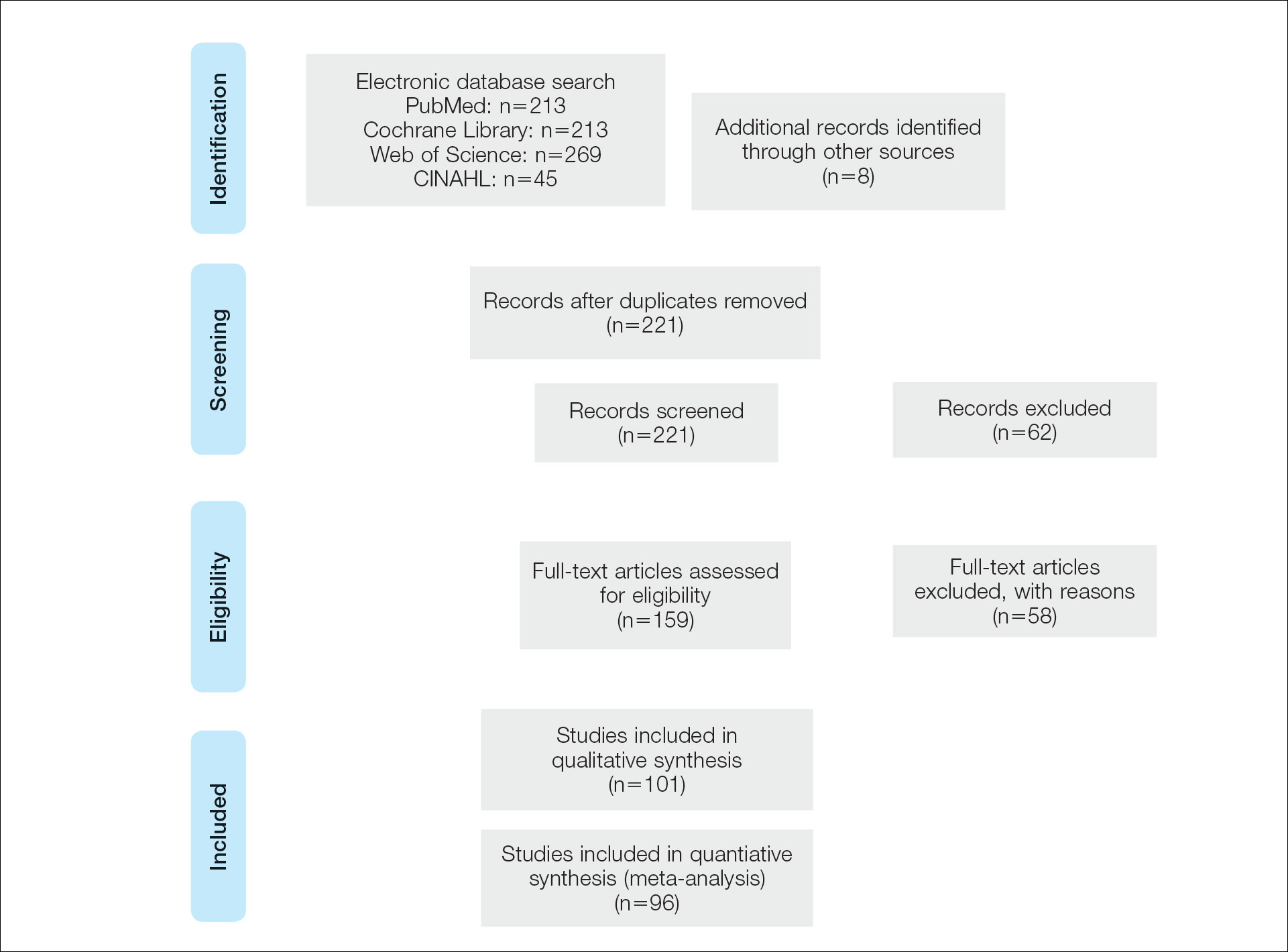

The process to develop and validate GRAIL’s blood-based cancer screening test includes 4 large clinical trials of more than 180,000 participants, including those with cancer and those without. The Circulating Cell-Free Genome Atlas (CCGA) Study, was a prospective, case-controlled, observational study enrolling approximately 15,000 participants with 3 prespecified sub-studies. The first sub-study developed the machine-learning classifier for both early detection and tumor of origin detection.25,26

The highest performing assay from the first sub-study then went on to be further validated in the 2nd and 3rd sub-studies. The 3rd sub-study, published in the Annals of Oncology in 2021 looked at a cohort of 4,077 participants with and without cancer, and found the specificity of cancer signal detection to be 99.5% and the overall sensitivity to be 51.5%, with increasing sensitivity by cancer stage (stage I - 17%, stage II - 40%, stage III - 77%, and stage IV - 90.1%).24 The false-positive rate was low, at 0.7%, and the true positive rate was 88.7%. Notably, the test was able to correctly identify the tumor of origin for 93% of samples.24 The study overall demonstrated high specificity and accuracy of tumor site of origin and supported the use of this blood-based MCED assay.

The PATHFINDER study was another prospective, multicenter clinical trial that enrolled more than 6,000 participants in the United States. The participants were aged >50 years with or without additional cancer risk factors. The goal of this study was to determine the extent of testing required to achieve diagnosis after a “cancer signal detected” result. The study results found that, when MCED testing was added to the standard-of-care screening, the number of cancers detected doubled when compared with standard cancer screening alone.27,28 Of the 92 participants with positive cancer signals, 35 were diagnosed with cancer, and 71% of these cancer types did not have standard-ofcare screening. The tumor site of origin was correctly detected in 97% of cases, and there were less than 1% of false positives. Overall, the test led to diagnostic evaluation of 1.4% of patients and a cancer diagnosis in 0.5%.

Currently, there are 2 ongoing clinical trials to further evaluate the Galleri MCED test. The STRIVE trial that aims to prospectively validate the MCED test in a population of nearly 100,000 women undergoing mammography,29 and the SUMMIT trial,30 which is similarly aiming to validate the test in a group of individuals, half of whom have a significantly elevated risk of lung cancer.

With the promising results described above, the Galleri test became the first MCED test available for commercial use starting in 2022. It is only available for use in people who are aged 50 and older, have a family history of cancer, or are at an increased risk for cancer (although GRAIL does not elaborate on what constitutes increased risk). However, the Galleri test is only available through prescription—therefore, if interested, patients must ask their health care provider to register with GRAIL and order the test (https://www .galleri.com/hcp/the-galleri-test/ordering). Additionally, the test will cost the patient $949 and is not yet covered by insurances. Currently, several large health care groups such as the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Cleveland Clinic, and Mercy hospitals have partnered with GRAIL to offer their test to certain patients for use as part of clinical trials. Currently, no MCED test, including the Galleri, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Incorporating MCED testing into clinical practice

The Galleri MCED test has promising potential to make multi-cancer screening feasible and obtainable, which could ultimately reduce late-stage cancer diagnosis and decrease mortality from all cancers. The compelling data from large cohorts and numerous clinical trials demonstrate its accuracy, reliability, reproducibility, and specificity. It can detect up to 50 different types of cancers, including cancers that affect our gynecologic patients, including breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine. Additionally, its novel methylation-based assay accurately identifies the tumor site of origin in 97% of cases.28 Ongoing and future clinical trials will continue to validate and refine these methods and improve the sensitivity and positive-predictive value of this assay. As mentioned, although it has been incorporated into various large health care systems, it is not FDA approved and has not been validated in the general population. Additionally, it should not be used as a replacement for recommended screening.

CASE Resolved

The patient is eligible for the Galleri MCED test if ordered by her physician. However, she will need to pay for the test out-of-pocket. Due to her family history, she should consider germline genetic testing (either for herself, or if possible, for her father, who should meet criteria based on his prostate cancer).3 Panel testing for germline mutations has become much more accessible, and until MCED testing is ready for prime time, it remains one of the best ways to predict and prevent cancers. Additionally, she should continue to undergo routine screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer as indicated. ●

- Mammography has helped reduce breast cancer mortality in the United States by nearly 40% since 19901

- Increases in screening for lung cancer with computed tomography in the United States are estimated to have saved more than 10,000 lives between 2014 and 20182

- Routine prostate specific antigen screening is no longer recommended for men at average risk for prostate cancer, and patients are advised to discuss risks and benefits of screening with their clinicians3

- Where screening programs have long been established, cervical cancer rates have decreased by as much as 65% over the past 40 years4

- 68% of colorectal cancer deaths could be prevented with increased screening, and one of the most effective ways to get screened is colonoscopy5

References

1. American College of Radiology website. https://www.acr.org/Practice-Management-Quality-Informatics/Practice-Toolkit/PatientResources/Mammography-Saves-Lives. Accessed March 1, 2023.

2. US lung cancer screening linked to earlier diagnosis and better survival. BMJ.com. https://www.bmj.com/company/newsroom/ us-lung-cancer-screening-linked-to-earlier-diagnosis-and-better-survival/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

3. Draisma G, Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: importance of methods and context. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:374-383.

4. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: Can J Clinicians. 2015;65:87-108.

5. Colon cancer coalition website. Fact check: Do colonoscopies save lives? https://coloncancercoalition.org/2022/10/11/fact-checkdo-colonoscopies-save-lives/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Centers%20for,get%20screened%20is%20a%20colonoscopy. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719-724.

- Davies K. The era of genomic medicine. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13:594-601.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. Version 3.2023. February 13, 2023.

- Finch APM, Lubinski J, Møller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1547-1553.

- Xiao Y-L, Wang K, Liu Q, et al. Risk reduction and survival benefit of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in hereditary breast cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19:e48-e65.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

- Pritchard D, Goodman C, Nadauld LD. Clinical utility of genomic testing in cancer care. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100349.

- Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities: ACOG Practice Bulletin summary, number 226. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:859-867.

- Yan Y-y, Guo Q-r, Wang F-h, et al. Cell-free DNA: hope and potential application in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9.

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, et al. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127:3029-3030.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71:209-249.

- Hawkes N. Cancer survival data emphasize importance of early diagnosis. BMJ. 2019;364:408.

- Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:S92-S107.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening tests. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/prevention/screening. htm#print. Reviewed May 19, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Wingo PA, Cardinez CJ, Landis SH, et al. Long-term trends in cancer mortality in the United States, 1930–1998. Cancer. 2003;97:3133-3275.

- Liao CI, Franceur AA, Kapp DS, et al. Trends in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers, Demographic Characteristics, and Vaccinations in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e222530. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2022.2530.

- Ho T-QH, Bissell MCS, Kerlikowske K, et al. Cumulative probability of false-positive results after 10 years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:e222440.

- Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: the CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:883-895.

- Heitzer E, Ulz P, Geigl JB. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer. Clin Chem. 2015;61:112-123.

- Dominguez-Vigil IG, Moreno-Martinez AK, Wang JY, et al. The dawn of the liquid biopsy in the fight against cancer. Oncotarget. 2018; 9:2912–2922. doi: 10.18632/ oncotarget.23131.

- GRAIL. https://grail.com/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, et al. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:531-548.

- Osborne CM, Hardisty E, Devers P, et al. Discordant noninvasive prenatal testing results in a patient subsequently diagnosed with metastatic disease. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33:609-611.

- Klein EA, Richards D, Cohn A, et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncology. 2021;32:1167-1177.

- Li B, Wang C, Xu J, et al. Abstract A06: multiplatform analysis of early-stage cancer signatures in blood. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11 supplement):A06-A.

- Shen SY, Singhania R, Fehringer G, et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature. 2018;563:579-583.

- Nadauld LD, McDonnell CH 3rd, Beer TM, et al. The PATHFINDER Study: assessment of the implementation of an investigational multi-cancer early detection test into clinical practice. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13.

- Klein EA. A prospective study of a multi-cancer early detection blood test in a clinical practice setting. Abstract presented at ESMO conference; Portland, OR. October 18, 2022.

- The STRIVE Study: development of a blood test for early detection of multiple cancer types. https://clinicaltrials.gov /ct2/show/NCT03085888. Accessed March 2, 2023.

- The SUMMIT Study: a cancer screening study (SUMMIT). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03934866. Accessed March 2, 2023.

CASE Patient inquires about new technology to detect cancer

A 51-year-old woman (para 2) presents to your clinic for a routine gynecology exam. She is up to date on her screening mammogram and Pap testing. She has her first colonoscopy scheduled for next month. She has a 10-year remote smoking history, but she stopped smoking in her late twenties. Her cousin was recently diagnosed with skin cancer, her father had prostate cancer and is now in remission, and her paternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer. She knows ovarian cancer does not have an effective screening test, and she recently heard on the news about a new blood test that can detect cancer before symptoms start. She would like to know more about this test. Could it replace her next Pap, mammogram, and future colonoscopies? She also wants to know—How can a simple blood test detect cancer?

The power of genomics in cancer care

Since the first human genome was sequenced in 2000, the power of genomics has been evident across many aspects of medicine, including cancer care.1 Whereas the first human genome to be sequenced took more than 10 years to sequence and cost over $1 billion, sequencing of your entire genome can now be obtained for less than $400—with results in a week.2

Genomics is now an integral part of cancer care, with results having implications for both cancer risk and prevention as well as more individualized treatment. For example, a healthy 42-year-old patient with a strong family history of breast cancer may undergo genetic testing and discover she has a mutation in the tumor suppression gene BRCA1, which carries a 39% to 58% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.3 By undergoing a risk-reducing bilateral salpingooophorectomy she will lower her ovarian cancer risk by up to 96%.4,5 A 67-year-old with a new diagnosis of stage III ovarian cancer and a BRCA2 mutation may be in remission for 5+ years due to her BRCA2 mutation, which makes her eligible for the use of the poly(ADPribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib.6 Genetic testing as illustrated above has led to decreased cancer-related mortality and prolonged survival.7 However, many women with such germline mutations are faced with difficult choices about surgical risk reduction, with the potential harms of early menopause and quality of life concerns. Having a test that does not just predict cancer risk but in fact quantifies that risk for the individual would greatly help in these decisions. Furthermore, more than 75% of ovarian cancers occur without a germline mutation.

Advances in genetic testing technology also have led to the ability to obtain genetic information from a simple blood test. For example, cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which is DNA fragments that are normally found to be circulating in the bloodstream, is routinely used as a screening tool for prenatal genetic testing to detect chromosomal abnormalities in the fetus.8 This technology relies on analyzing fetal free (non-cellular) DNA that is naturally found circulating in maternal blood. More recently, similar technology using cfDNA has been applied for the screening and characterization of certain cancers.9 This powerful technology can detect cancer before symptoms begin—all from a simple blood test, often referred to as a “liquid biopsy.” However, understanding the utility, supporting data, and target population for these tests is important before employing them as part of routine clinical practice.

Continue to: Current methods of cancer screening are limited...

Current methods of cancer screening are limited

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, with nearly 10 million cancer-related deaths annually, and it may surpass cardiovascular disease as the leading cause over the course of the century.10,11 Many cancer deaths are in part due to late-stage diagnosis, when the cancer has already metastasized.12 Early detection of cancer improves outcomes and survival rates, but it is often difficult to detect early due to the lack of early symptoms with many cancers, which can limit cancer screening and issues with access to care.13

Currently, there are only 5 cancers: cervical, prostate, breast, colon, and lung (for high-risk adults) that are screened for in the general population (see "Cancer screening has helped save countless lives" at the end of this article).14 The Pap test to screen for cervical cancer, developed in the 1940s, has saved millions of women’s lives and reduced the mortality of cervical cancer by 70%.15 Coupled with the availability and implementation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, cervical cancer rates are decreasing at substantial rates.16 However, there are no validated screening tests for uterine cancer, the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, or ovarian cancer, the most lethal.

Screening tests for cervical, prostate, breast, colon, and lung cancer have helped save millions of lives; however, these tests also come with high false-positive rates and the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment. For example, half of women undergoing mammograms will receive a false-positive result over a 10-year time period,17 and up to 50% of men undergoing prostate cancer screening have a positive prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test result when they do not actually have prostate cancer.18 Additionally, the positive predictive value of the current standard-of-care screening tests can be as low as <5%. Most diagnoses of cancer are made from a surgical biopsy, but these types of procedures can be difficult depending on the location or size of the tumor.19

The liquid biopsy. Given the limitations of current cancer screening and diagnostic tests, there is a great need for a more sensitive test that also can detect cancer from multiple organ sites. Liquid biopsy-based biomarkers can include circulating tumor cells, exosomes, microRNAs, and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). With advances in next-generation sequencing, ctDNA techniques remain the most promising.20

Methylation-based MCED testing: A new way of cancer screening

Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) technology was developed to address the need for better cancer screening and has the potential to detect up to 50 cancers with a simple blood test. This new technology opens the possibility for early detection of multiple cancers before symptoms even begin. MCED testing is sometimes referred to as “GRAIL” testing, after the American biotechnology company that developed the first commercially available MCED test, called the Galleri test (Galleri, Menlo Park, California). Although other biotechnology companies are developing similar technology (Exact Sciences, Madison, Wisconsin, and Freenome, South San Francisco, California, for example), this is the first test of its kind available to the public.21

The MCED test works by detecting the cfDNA fragments that are released into the blood passively by necrotic or apoptotic cells or secreted actively from tumor cells. The DNA from tumor cells is also known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). CtDNA is found in much lower quantities in the blood stream compared with cfDNA from cells, making it difficult to distinguish a cancer versus a noncancer cell and to determine the tumor site of origin.22

Through innovation, the first example of detecting cancer through this method in fact came as a surprise result from an abnormal cfDNA test. A pregnant 37-yearold woman had a cfDNA result suggestive of aneuploidy for chromosomes 18 and 13; however, she gave birth to a normal male fetus. Shortly thereafter, a vaginal biopsy confirmed small-cell carcinoma with alterations in chromosomes 18 and 13.23 GRAIL testing for this patient was subsequently able to optimize their methods of detecting both the presence of cancer cells and the tumor site of origin by utilizing next-generation genomic sequencing and methylation. Their development of a methylation-based assay combined with 46 machine-learning allowed the test to determine, first, if there is cancer present or not, and second, the tissue of origin prediction. It is important to note that these tests are meant to be used in addition to standard-of-care screening tests, not as an alternative, and this is emphasized throughout the company’s website and the medical literature.24

Continue to: The process to develop and validate GRAIL’s blood-based cancer screening test...

The process to develop and validate GRAIL’s blood-based cancer screening test includes 4 large clinical trials of more than 180,000 participants, including those with cancer and those without. The Circulating Cell-Free Genome Atlas (CCGA) Study, was a prospective, case-controlled, observational study enrolling approximately 15,000 participants with 3 prespecified sub-studies. The first sub-study developed the machine-learning classifier for both early detection and tumor of origin detection.25,26

The highest performing assay from the first sub-study then went on to be further validated in the 2nd and 3rd sub-studies. The 3rd sub-study, published in the Annals of Oncology in 2021 looked at a cohort of 4,077 participants with and without cancer, and found the specificity of cancer signal detection to be 99.5% and the overall sensitivity to be 51.5%, with increasing sensitivity by cancer stage (stage I - 17%, stage II - 40%, stage III - 77%, and stage IV - 90.1%).24 The false-positive rate was low, at 0.7%, and the true positive rate was 88.7%. Notably, the test was able to correctly identify the tumor of origin for 93% of samples.24 The study overall demonstrated high specificity and accuracy of tumor site of origin and supported the use of this blood-based MCED assay.

The PATHFINDER study was another prospective, multicenter clinical trial that enrolled more than 6,000 participants in the United States. The participants were aged >50 years with or without additional cancer risk factors. The goal of this study was to determine the extent of testing required to achieve diagnosis after a “cancer signal detected” result. The study results found that, when MCED testing was added to the standard-of-care screening, the number of cancers detected doubled when compared with standard cancer screening alone.27,28 Of the 92 participants with positive cancer signals, 35 were diagnosed with cancer, and 71% of these cancer types did not have standard-ofcare screening. The tumor site of origin was correctly detected in 97% of cases, and there were less than 1% of false positives. Overall, the test led to diagnostic evaluation of 1.4% of patients and a cancer diagnosis in 0.5%.

Currently, there are 2 ongoing clinical trials to further evaluate the Galleri MCED test. The STRIVE trial that aims to prospectively validate the MCED test in a population of nearly 100,000 women undergoing mammography,29 and the SUMMIT trial,30 which is similarly aiming to validate the test in a group of individuals, half of whom have a significantly elevated risk of lung cancer.

With the promising results described above, the Galleri test became the first MCED test available for commercial use starting in 2022. It is only available for use in people who are aged 50 and older, have a family history of cancer, or are at an increased risk for cancer (although GRAIL does not elaborate on what constitutes increased risk). However, the Galleri test is only available through prescription—therefore, if interested, patients must ask their health care provider to register with GRAIL and order the test (https://www .galleri.com/hcp/the-galleri-test/ordering). Additionally, the test will cost the patient $949 and is not yet covered by insurances. Currently, several large health care groups such as the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Cleveland Clinic, and Mercy hospitals have partnered with GRAIL to offer their test to certain patients for use as part of clinical trials. Currently, no MCED test, including the Galleri, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Incorporating MCED testing into clinical practice

The Galleri MCED test has promising potential to make multi-cancer screening feasible and obtainable, which could ultimately reduce late-stage cancer diagnosis and decrease mortality from all cancers. The compelling data from large cohorts and numerous clinical trials demonstrate its accuracy, reliability, reproducibility, and specificity. It can detect up to 50 different types of cancers, including cancers that affect our gynecologic patients, including breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine. Additionally, its novel methylation-based assay accurately identifies the tumor site of origin in 97% of cases.28 Ongoing and future clinical trials will continue to validate and refine these methods and improve the sensitivity and positive-predictive value of this assay. As mentioned, although it has been incorporated into various large health care systems, it is not FDA approved and has not been validated in the general population. Additionally, it should not be used as a replacement for recommended screening.

CASE Resolved

The patient is eligible for the Galleri MCED test if ordered by her physician. However, she will need to pay for the test out-of-pocket. Due to her family history, she should consider germline genetic testing (either for herself, or if possible, for her father, who should meet criteria based on his prostate cancer).3 Panel testing for germline mutations has become much more accessible, and until MCED testing is ready for prime time, it remains one of the best ways to predict and prevent cancers. Additionally, she should continue to undergo routine screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer as indicated. ●

- Mammography has helped reduce breast cancer mortality in the United States by nearly 40% since 19901

- Increases in screening for lung cancer with computed tomography in the United States are estimated to have saved more than 10,000 lives between 2014 and 20182

- Routine prostate specific antigen screening is no longer recommended for men at average risk for prostate cancer, and patients are advised to discuss risks and benefits of screening with their clinicians3

- Where screening programs have long been established, cervical cancer rates have decreased by as much as 65% over the past 40 years4

- 68% of colorectal cancer deaths could be prevented with increased screening, and one of the most effective ways to get screened is colonoscopy5

References

1. American College of Radiology website. https://www.acr.org/Practice-Management-Quality-Informatics/Practice-Toolkit/PatientResources/Mammography-Saves-Lives. Accessed March 1, 2023.

2. US lung cancer screening linked to earlier diagnosis and better survival. BMJ.com. https://www.bmj.com/company/newsroom/ us-lung-cancer-screening-linked-to-earlier-diagnosis-and-better-survival/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

3. Draisma G, Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: importance of methods and context. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:374-383.

4. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: Can J Clinicians. 2015;65:87-108.

5. Colon cancer coalition website. Fact check: Do colonoscopies save lives? https://coloncancercoalition.org/2022/10/11/fact-checkdo-colonoscopies-save-lives/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Centers%20for,get%20screened%20is%20a%20colonoscopy. Accessed March 1, 2023.

CASE Patient inquires about new technology to detect cancer

A 51-year-old woman (para 2) presents to your clinic for a routine gynecology exam. She is up to date on her screening mammogram and Pap testing. She has her first colonoscopy scheduled for next month. She has a 10-year remote smoking history, but she stopped smoking in her late twenties. Her cousin was recently diagnosed with skin cancer, her father had prostate cancer and is now in remission, and her paternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer. She knows ovarian cancer does not have an effective screening test, and she recently heard on the news about a new blood test that can detect cancer before symptoms start. She would like to know more about this test. Could it replace her next Pap, mammogram, and future colonoscopies? She also wants to know—How can a simple blood test detect cancer?

The power of genomics in cancer care

Since the first human genome was sequenced in 2000, the power of genomics has been evident across many aspects of medicine, including cancer care.1 Whereas the first human genome to be sequenced took more than 10 years to sequence and cost over $1 billion, sequencing of your entire genome can now be obtained for less than $400—with results in a week.2

Genomics is now an integral part of cancer care, with results having implications for both cancer risk and prevention as well as more individualized treatment. For example, a healthy 42-year-old patient with a strong family history of breast cancer may undergo genetic testing and discover she has a mutation in the tumor suppression gene BRCA1, which carries a 39% to 58% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.3 By undergoing a risk-reducing bilateral salpingooophorectomy she will lower her ovarian cancer risk by up to 96%.4,5 A 67-year-old with a new diagnosis of stage III ovarian cancer and a BRCA2 mutation may be in remission for 5+ years due to her BRCA2 mutation, which makes her eligible for the use of the poly(ADPribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib.6 Genetic testing as illustrated above has led to decreased cancer-related mortality and prolonged survival.7 However, many women with such germline mutations are faced with difficult choices about surgical risk reduction, with the potential harms of early menopause and quality of life concerns. Having a test that does not just predict cancer risk but in fact quantifies that risk for the individual would greatly help in these decisions. Furthermore, more than 75% of ovarian cancers occur without a germline mutation.

Advances in genetic testing technology also have led to the ability to obtain genetic information from a simple blood test. For example, cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which is DNA fragments that are normally found to be circulating in the bloodstream, is routinely used as a screening tool for prenatal genetic testing to detect chromosomal abnormalities in the fetus.8 This technology relies on analyzing fetal free (non-cellular) DNA that is naturally found circulating in maternal blood. More recently, similar technology using cfDNA has been applied for the screening and characterization of certain cancers.9 This powerful technology can detect cancer before symptoms begin—all from a simple blood test, often referred to as a “liquid biopsy.” However, understanding the utility, supporting data, and target population for these tests is important before employing them as part of routine clinical practice.

Continue to: Current methods of cancer screening are limited...

Current methods of cancer screening are limited

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, with nearly 10 million cancer-related deaths annually, and it may surpass cardiovascular disease as the leading cause over the course of the century.10,11 Many cancer deaths are in part due to late-stage diagnosis, when the cancer has already metastasized.12 Early detection of cancer improves outcomes and survival rates, but it is often difficult to detect early due to the lack of early symptoms with many cancers, which can limit cancer screening and issues with access to care.13

Currently, there are only 5 cancers: cervical, prostate, breast, colon, and lung (for high-risk adults) that are screened for in the general population (see "Cancer screening has helped save countless lives" at the end of this article).14 The Pap test to screen for cervical cancer, developed in the 1940s, has saved millions of women’s lives and reduced the mortality of cervical cancer by 70%.15 Coupled with the availability and implementation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, cervical cancer rates are decreasing at substantial rates.16 However, there are no validated screening tests for uterine cancer, the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, or ovarian cancer, the most lethal.

Screening tests for cervical, prostate, breast, colon, and lung cancer have helped save millions of lives; however, these tests also come with high false-positive rates and the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment. For example, half of women undergoing mammograms will receive a false-positive result over a 10-year time period,17 and up to 50% of men undergoing prostate cancer screening have a positive prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test result when they do not actually have prostate cancer.18 Additionally, the positive predictive value of the current standard-of-care screening tests can be as low as <5%. Most diagnoses of cancer are made from a surgical biopsy, but these types of procedures can be difficult depending on the location or size of the tumor.19

The liquid biopsy. Given the limitations of current cancer screening and diagnostic tests, there is a great need for a more sensitive test that also can detect cancer from multiple organ sites. Liquid biopsy-based biomarkers can include circulating tumor cells, exosomes, microRNAs, and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). With advances in next-generation sequencing, ctDNA techniques remain the most promising.20

Methylation-based MCED testing: A new way of cancer screening

Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) technology was developed to address the need for better cancer screening and has the potential to detect up to 50 cancers with a simple blood test. This new technology opens the possibility for early detection of multiple cancers before symptoms even begin. MCED testing is sometimes referred to as “GRAIL” testing, after the American biotechnology company that developed the first commercially available MCED test, called the Galleri test (Galleri, Menlo Park, California). Although other biotechnology companies are developing similar technology (Exact Sciences, Madison, Wisconsin, and Freenome, South San Francisco, California, for example), this is the first test of its kind available to the public.21

The MCED test works by detecting the cfDNA fragments that are released into the blood passively by necrotic or apoptotic cells or secreted actively from tumor cells. The DNA from tumor cells is also known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). CtDNA is found in much lower quantities in the blood stream compared with cfDNA from cells, making it difficult to distinguish a cancer versus a noncancer cell and to determine the tumor site of origin.22

Through innovation, the first example of detecting cancer through this method in fact came as a surprise result from an abnormal cfDNA test. A pregnant 37-yearold woman had a cfDNA result suggestive of aneuploidy for chromosomes 18 and 13; however, she gave birth to a normal male fetus. Shortly thereafter, a vaginal biopsy confirmed small-cell carcinoma with alterations in chromosomes 18 and 13.23 GRAIL testing for this patient was subsequently able to optimize their methods of detecting both the presence of cancer cells and the tumor site of origin by utilizing next-generation genomic sequencing and methylation. Their development of a methylation-based assay combined with 46 machine-learning allowed the test to determine, first, if there is cancer present or not, and second, the tissue of origin prediction. It is important to note that these tests are meant to be used in addition to standard-of-care screening tests, not as an alternative, and this is emphasized throughout the company’s website and the medical literature.24

Continue to: The process to develop and validate GRAIL’s blood-based cancer screening test...

The process to develop and validate GRAIL’s blood-based cancer screening test includes 4 large clinical trials of more than 180,000 participants, including those with cancer and those without. The Circulating Cell-Free Genome Atlas (CCGA) Study, was a prospective, case-controlled, observational study enrolling approximately 15,000 participants with 3 prespecified sub-studies. The first sub-study developed the machine-learning classifier for both early detection and tumor of origin detection.25,26

The highest performing assay from the first sub-study then went on to be further validated in the 2nd and 3rd sub-studies. The 3rd sub-study, published in the Annals of Oncology in 2021 looked at a cohort of 4,077 participants with and without cancer, and found the specificity of cancer signal detection to be 99.5% and the overall sensitivity to be 51.5%, with increasing sensitivity by cancer stage (stage I - 17%, stage II - 40%, stage III - 77%, and stage IV - 90.1%).24 The false-positive rate was low, at 0.7%, and the true positive rate was 88.7%. Notably, the test was able to correctly identify the tumor of origin for 93% of samples.24 The study overall demonstrated high specificity and accuracy of tumor site of origin and supported the use of this blood-based MCED assay.

The PATHFINDER study was another prospective, multicenter clinical trial that enrolled more than 6,000 participants in the United States. The participants were aged >50 years with or without additional cancer risk factors. The goal of this study was to determine the extent of testing required to achieve diagnosis after a “cancer signal detected” result. The study results found that, when MCED testing was added to the standard-of-care screening, the number of cancers detected doubled when compared with standard cancer screening alone.27,28 Of the 92 participants with positive cancer signals, 35 were diagnosed with cancer, and 71% of these cancer types did not have standard-ofcare screening. The tumor site of origin was correctly detected in 97% of cases, and there were less than 1% of false positives. Overall, the test led to diagnostic evaluation of 1.4% of patients and a cancer diagnosis in 0.5%.

Currently, there are 2 ongoing clinical trials to further evaluate the Galleri MCED test. The STRIVE trial that aims to prospectively validate the MCED test in a population of nearly 100,000 women undergoing mammography,29 and the SUMMIT trial,30 which is similarly aiming to validate the test in a group of individuals, half of whom have a significantly elevated risk of lung cancer.

With the promising results described above, the Galleri test became the first MCED test available for commercial use starting in 2022. It is only available for use in people who are aged 50 and older, have a family history of cancer, or are at an increased risk for cancer (although GRAIL does not elaborate on what constitutes increased risk). However, the Galleri test is only available through prescription—therefore, if interested, patients must ask their health care provider to register with GRAIL and order the test (https://www .galleri.com/hcp/the-galleri-test/ordering). Additionally, the test will cost the patient $949 and is not yet covered by insurances. Currently, several large health care groups such as the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Cleveland Clinic, and Mercy hospitals have partnered with GRAIL to offer their test to certain patients for use as part of clinical trials. Currently, no MCED test, including the Galleri, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Incorporating MCED testing into clinical practice

The Galleri MCED test has promising potential to make multi-cancer screening feasible and obtainable, which could ultimately reduce late-stage cancer diagnosis and decrease mortality from all cancers. The compelling data from large cohorts and numerous clinical trials demonstrate its accuracy, reliability, reproducibility, and specificity. It can detect up to 50 different types of cancers, including cancers that affect our gynecologic patients, including breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine. Additionally, its novel methylation-based assay accurately identifies the tumor site of origin in 97% of cases.28 Ongoing and future clinical trials will continue to validate and refine these methods and improve the sensitivity and positive-predictive value of this assay. As mentioned, although it has been incorporated into various large health care systems, it is not FDA approved and has not been validated in the general population. Additionally, it should not be used as a replacement for recommended screening.

CASE Resolved

The patient is eligible for the Galleri MCED test if ordered by her physician. However, she will need to pay for the test out-of-pocket. Due to her family history, she should consider germline genetic testing (either for herself, or if possible, for her father, who should meet criteria based on his prostate cancer).3 Panel testing for germline mutations has become much more accessible, and until MCED testing is ready for prime time, it remains one of the best ways to predict and prevent cancers. Additionally, she should continue to undergo routine screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer as indicated. ●

- Mammography has helped reduce breast cancer mortality in the United States by nearly 40% since 19901

- Increases in screening for lung cancer with computed tomography in the United States are estimated to have saved more than 10,000 lives between 2014 and 20182

- Routine prostate specific antigen screening is no longer recommended for men at average risk for prostate cancer, and patients are advised to discuss risks and benefits of screening with their clinicians3

- Where screening programs have long been established, cervical cancer rates have decreased by as much as 65% over the past 40 years4

- 68% of colorectal cancer deaths could be prevented with increased screening, and one of the most effective ways to get screened is colonoscopy5

References

1. American College of Radiology website. https://www.acr.org/Practice-Management-Quality-Informatics/Practice-Toolkit/PatientResources/Mammography-Saves-Lives. Accessed March 1, 2023.

2. US lung cancer screening linked to earlier diagnosis and better survival. BMJ.com. https://www.bmj.com/company/newsroom/ us-lung-cancer-screening-linked-to-earlier-diagnosis-and-better-survival/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

3. Draisma G, Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: importance of methods and context. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:374-383.

4. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: Can J Clinicians. 2015;65:87-108.

5. Colon cancer coalition website. Fact check: Do colonoscopies save lives? https://coloncancercoalition.org/2022/10/11/fact-checkdo-colonoscopies-save-lives/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Centers%20for,get%20screened%20is%20a%20colonoscopy. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719-724.

- Davies K. The era of genomic medicine. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13:594-601.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. Version 3.2023. February 13, 2023.

- Finch APM, Lubinski J, Møller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1547-1553.

- Xiao Y-L, Wang K, Liu Q, et al. Risk reduction and survival benefit of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in hereditary breast cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19:e48-e65.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

- Pritchard D, Goodman C, Nadauld LD. Clinical utility of genomic testing in cancer care. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100349.

- Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities: ACOG Practice Bulletin summary, number 226. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:859-867.

- Yan Y-y, Guo Q-r, Wang F-h, et al. Cell-free DNA: hope and potential application in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9.

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, et al. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127:3029-3030.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71:209-249.

- Hawkes N. Cancer survival data emphasize importance of early diagnosis. BMJ. 2019;364:408.

- Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:S92-S107.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening tests. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/prevention/screening. htm#print. Reviewed May 19, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Wingo PA, Cardinez CJ, Landis SH, et al. Long-term trends in cancer mortality in the United States, 1930–1998. Cancer. 2003;97:3133-3275.

- Liao CI, Franceur AA, Kapp DS, et al. Trends in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers, Demographic Characteristics, and Vaccinations in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e222530. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2022.2530.

- Ho T-QH, Bissell MCS, Kerlikowske K, et al. Cumulative probability of false-positive results after 10 years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:e222440.

- Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: the CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:883-895.

- Heitzer E, Ulz P, Geigl JB. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer. Clin Chem. 2015;61:112-123.

- Dominguez-Vigil IG, Moreno-Martinez AK, Wang JY, et al. The dawn of the liquid biopsy in the fight against cancer. Oncotarget. 2018; 9:2912–2922. doi: 10.18632/ oncotarget.23131.

- GRAIL. https://grail.com/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, et al. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:531-548.

- Osborne CM, Hardisty E, Devers P, et al. Discordant noninvasive prenatal testing results in a patient subsequently diagnosed with metastatic disease. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33:609-611.

- Klein EA, Richards D, Cohn A, et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncology. 2021;32:1167-1177.

- Li B, Wang C, Xu J, et al. Abstract A06: multiplatform analysis of early-stage cancer signatures in blood. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11 supplement):A06-A.

- Shen SY, Singhania R, Fehringer G, et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature. 2018;563:579-583.

- Nadauld LD, McDonnell CH 3rd, Beer TM, et al. The PATHFINDER Study: assessment of the implementation of an investigational multi-cancer early detection test into clinical practice. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13.

- Klein EA. A prospective study of a multi-cancer early detection blood test in a clinical practice setting. Abstract presented at ESMO conference; Portland, OR. October 18, 2022.

- The STRIVE Study: development of a blood test for early detection of multiple cancer types. https://clinicaltrials.gov /ct2/show/NCT03085888. Accessed March 2, 2023.

- The SUMMIT Study: a cancer screening study (SUMMIT). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03934866. Accessed March 2, 2023.

- Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719-724.

- Davies K. The era of genomic medicine. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13:594-601.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. Version 3.2023. February 13, 2023.

- Finch APM, Lubinski J, Møller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1547-1553.

- Xiao Y-L, Wang K, Liu Q, et al. Risk reduction and survival benefit of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in hereditary breast cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19:e48-e65.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

- Pritchard D, Goodman C, Nadauld LD. Clinical utility of genomic testing in cancer care. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100349.

- Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities: ACOG Practice Bulletin summary, number 226. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:859-867.

- Yan Y-y, Guo Q-r, Wang F-h, et al. Cell-free DNA: hope and potential application in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9.

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, et al. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127:3029-3030.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71:209-249.

- Hawkes N. Cancer survival data emphasize importance of early diagnosis. BMJ. 2019;364:408.

- Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:S92-S107.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening tests. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/prevention/screening. htm#print. Reviewed May 19, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Wingo PA, Cardinez CJ, Landis SH, et al. Long-term trends in cancer mortality in the United States, 1930–1998. Cancer. 2003;97:3133-3275.

- Liao CI, Franceur AA, Kapp DS, et al. Trends in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers, Demographic Characteristics, and Vaccinations in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e222530. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2022.2530.

- Ho T-QH, Bissell MCS, Kerlikowske K, et al. Cumulative probability of false-positive results after 10 years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:e222440.

- Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: the CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:883-895.

- Heitzer E, Ulz P, Geigl JB. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer. Clin Chem. 2015;61:112-123.

- Dominguez-Vigil IG, Moreno-Martinez AK, Wang JY, et al. The dawn of the liquid biopsy in the fight against cancer. Oncotarget. 2018; 9:2912–2922. doi: 10.18632/ oncotarget.23131.

- GRAIL. https://grail.com/. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, et al. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:531-548.

- Osborne CM, Hardisty E, Devers P, et al. Discordant noninvasive prenatal testing results in a patient subsequently diagnosed with metastatic disease. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33:609-611.

- Klein EA, Richards D, Cohn A, et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncology. 2021;32:1167-1177.

- Li B, Wang C, Xu J, et al. Abstract A06: multiplatform analysis of early-stage cancer signatures in blood. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11 supplement):A06-A.

- Shen SY, Singhania R, Fehringer G, et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature. 2018;563:579-583.

- Nadauld LD, McDonnell CH 3rd, Beer TM, et al. The PATHFINDER Study: assessment of the implementation of an investigational multi-cancer early detection test into clinical practice. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13.

- Klein EA. A prospective study of a multi-cancer early detection blood test in a clinical practice setting. Abstract presented at ESMO conference; Portland, OR. October 18, 2022.

- The STRIVE Study: development of a blood test for early detection of multiple cancer types. https://clinicaltrials.gov /ct2/show/NCT03085888. Accessed March 2, 2023.

- The SUMMIT Study: a cancer screening study (SUMMIT). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03934866. Accessed March 2, 2023.

CarePostRoe.com: Study seeks to document poor quality medical care due to new abortion bans

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization removed federal protections for abortion that previously had been codified in Roe v Wade. Since this removal, most abortions have been banned in at least 13 states, and about half of states are expected to attempt to ban or heavily restrict abortion.1,2 These laws banning abortion are having effects on patient care far beyond abortion, leading to uncertainty and fear among providers and denied or delayed care for patients.3,4 It is critical that research documents the harmful effects of this policy change.

Patients that are pregnant with fetuses with severe malformations have had to travel long distances to other states to obtain care.5 Others have faced delays in obtaining treatment for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and even for other conditions that use medications that could potentially cause an abortion.6,7 These cases have the potential to result in serious harm or death of the patient with altered care. There is a published report from Texas showing how the change in practice due to the 6-week abortion ban imposed in 2021 was associated with a doubling of severe morbidity for patients presenting with preterm premature rupture of membranes and other complications before 22 weeks’ gestation.8

While these cases have been highlighted in the media, there has not been a resource that comprehensively documents the changes in care that clinicians have been forced to make because of abortion bans as well as the consequences for their patients’ health. The media also may not be the most desirable platform for sharing cases of substandard care if providers feel their confidentiality may be breached as they are told by their employers to avoid speaking with reporters.9 Bearing this in mind, our team of researchers at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California San Francisco and the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas at Austin has launched a project aiming to collect stories of poor quality care post-Roe from health care professionals across the United States. The aim of the study is to document examples of the challenges in patient care that have arisen since the Dobbs decision.

The study website CarePostRoe.com was launched in October 2022 to collect narratives from health care providers who participated in the care of a patient whose management was different from the usual standard due to a need to comply with new restrictions on abortion since the Dobbs decision. These providers can include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, or other allied health professionals. Clinicians can share information about a case through a brief survey linked on the website that will allow them to either submit a written narrative or a voice memo. The submissions are anonymous, and providers are not asked to submit any protected health information. If the submitter would like to share more information about the case via telephone interview, they will be taken to a separate survey which is not linked to the narrative submission to give contact information to participate in an interview.

Since October, more than 40 cases have been submitted that document patient cases from over half of the states with abortion bans. Clinicians describe pregnant patients with severe fetal malformations who have had to overcome financial and logistical barriers to travel to access abortion care. Several cases of patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies have been submitted, including cases that are being followed expectantly, which is inconsistent with the standard of care.10 We also have received several submissions about cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes in the second trimester where the patient was sent home and presented several days later with a severe infection requiring management in the intensive care unit. Cases of early pregnancy loss that could have been treated safely and routinely also were delayed, increasing the risk to patients who, in addition to receiving substandard medical care, had the trauma of fearing they could be prosecuted for receiving treatment.

We hope these data will be useful to document the impact of the Court’s decision and to improve patient care as health care institutions work to update their policies and protocols to reduce delays in care in the face of legal ambiguities. If you have been involved in such a case since June 2022, including caring for a patient who traveled from another state, please consider submitting it at CarePostRoe.com, and please spread the word through your networks.

- McCann A, Schoenfeld Walker A, Sasani A, et al. Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. May 24, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com /interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade .html

- Nash E, Ephross P. State policy trends 2022: in a devastating year, US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe leads to bans, confusion and chaos. Guttmacher Institute website. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org/2022/12/state -policy-trends-2022-devastating-year-us -supreme-courts-decision-overturn-roe-leads

- Cha AE. Physicians face confusion and fear in post-Roe world. Washington Post. June 28, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www .washingtonpost.com/health/2022/06/28 /abortion-ban-roe-doctors-confusion/

- Zernike K. Medical impact of Roe reversal goes well beyond abortion clinics, doctors say. New York Times. September 10, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes .com/2022/09/10/us/abortion-bans-medical -care-women.html

- Abrams A. ‘Never-ending nightmare.’ an Ohio woman was forced to travel out of state for an abortion. Time. August 29, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://time.com/6208860/ohio -woman-forced-travel-abortion/

- Belluck P. They had miscarriages, and new abortion laws obstructed treatment. New York Times. July 17, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/17/health /abortion-miscarriage-treatment.html

- Sellers FS, Nirappil F. Confusion post-Roe spurs delays, denials for some lifesaving pregnancy care. Washington Post. July 16, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost .com/health/2022/07/16/abortion-miscarriage -ectopic-pregnancy-care/.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1.

- Cohen E, Lape J, Herman D. “Heartbreaking” stories go untold, doctors say, as employers “muzzle” them in wake of abortion ruling. CNN website. Published October 12, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/12 /health/abortion-doctors-talking/index.html.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Miller R, Gyamfi-Bannerman C; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy [published online July 16, 2022]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Sep;227:B9-B20. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2022.06.024.

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization removed federal protections for abortion that previously had been codified in Roe v Wade. Since this removal, most abortions have been banned in at least 13 states, and about half of states are expected to attempt to ban or heavily restrict abortion.1,2 These laws banning abortion are having effects on patient care far beyond abortion, leading to uncertainty and fear among providers and denied or delayed care for patients.3,4 It is critical that research documents the harmful effects of this policy change.

Patients that are pregnant with fetuses with severe malformations have had to travel long distances to other states to obtain care.5 Others have faced delays in obtaining treatment for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and even for other conditions that use medications that could potentially cause an abortion.6,7 These cases have the potential to result in serious harm or death of the patient with altered care. There is a published report from Texas showing how the change in practice due to the 6-week abortion ban imposed in 2021 was associated with a doubling of severe morbidity for patients presenting with preterm premature rupture of membranes and other complications before 22 weeks’ gestation.8

While these cases have been highlighted in the media, there has not been a resource that comprehensively documents the changes in care that clinicians have been forced to make because of abortion bans as well as the consequences for their patients’ health. The media also may not be the most desirable platform for sharing cases of substandard care if providers feel their confidentiality may be breached as they are told by their employers to avoid speaking with reporters.9 Bearing this in mind, our team of researchers at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California San Francisco and the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas at Austin has launched a project aiming to collect stories of poor quality care post-Roe from health care professionals across the United States. The aim of the study is to document examples of the challenges in patient care that have arisen since the Dobbs decision.

The study website CarePostRoe.com was launched in October 2022 to collect narratives from health care providers who participated in the care of a patient whose management was different from the usual standard due to a need to comply with new restrictions on abortion since the Dobbs decision. These providers can include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, or other allied health professionals. Clinicians can share information about a case through a brief survey linked on the website that will allow them to either submit a written narrative or a voice memo. The submissions are anonymous, and providers are not asked to submit any protected health information. If the submitter would like to share more information about the case via telephone interview, they will be taken to a separate survey which is not linked to the narrative submission to give contact information to participate in an interview.

Since October, more than 40 cases have been submitted that document patient cases from over half of the states with abortion bans. Clinicians describe pregnant patients with severe fetal malformations who have had to overcome financial and logistical barriers to travel to access abortion care. Several cases of patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies have been submitted, including cases that are being followed expectantly, which is inconsistent with the standard of care.10 We also have received several submissions about cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes in the second trimester where the patient was sent home and presented several days later with a severe infection requiring management in the intensive care unit. Cases of early pregnancy loss that could have been treated safely and routinely also were delayed, increasing the risk to patients who, in addition to receiving substandard medical care, had the trauma of fearing they could be prosecuted for receiving treatment.

We hope these data will be useful to document the impact of the Court’s decision and to improve patient care as health care institutions work to update their policies and protocols to reduce delays in care in the face of legal ambiguities. If you have been involved in such a case since June 2022, including caring for a patient who traveled from another state, please consider submitting it at CarePostRoe.com, and please spread the word through your networks.

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization removed federal protections for abortion that previously had been codified in Roe v Wade. Since this removal, most abortions have been banned in at least 13 states, and about half of states are expected to attempt to ban or heavily restrict abortion.1,2 These laws banning abortion are having effects on patient care far beyond abortion, leading to uncertainty and fear among providers and denied or delayed care for patients.3,4 It is critical that research documents the harmful effects of this policy change.

Patients that are pregnant with fetuses with severe malformations have had to travel long distances to other states to obtain care.5 Others have faced delays in obtaining treatment for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and even for other conditions that use medications that could potentially cause an abortion.6,7 These cases have the potential to result in serious harm or death of the patient with altered care. There is a published report from Texas showing how the change in practice due to the 6-week abortion ban imposed in 2021 was associated with a doubling of severe morbidity for patients presenting with preterm premature rupture of membranes and other complications before 22 weeks’ gestation.8

While these cases have been highlighted in the media, there has not been a resource that comprehensively documents the changes in care that clinicians have been forced to make because of abortion bans as well as the consequences for their patients’ health. The media also may not be the most desirable platform for sharing cases of substandard care if providers feel their confidentiality may be breached as they are told by their employers to avoid speaking with reporters.9 Bearing this in mind, our team of researchers at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California San Francisco and the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas at Austin has launched a project aiming to collect stories of poor quality care post-Roe from health care professionals across the United States. The aim of the study is to document examples of the challenges in patient care that have arisen since the Dobbs decision.

The study website CarePostRoe.com was launched in October 2022 to collect narratives from health care providers who participated in the care of a patient whose management was different from the usual standard due to a need to comply with new restrictions on abortion since the Dobbs decision. These providers can include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, or other allied health professionals. Clinicians can share information about a case through a brief survey linked on the website that will allow them to either submit a written narrative or a voice memo. The submissions are anonymous, and providers are not asked to submit any protected health information. If the submitter would like to share more information about the case via telephone interview, they will be taken to a separate survey which is not linked to the narrative submission to give contact information to participate in an interview.

Since October, more than 40 cases have been submitted that document patient cases from over half of the states with abortion bans. Clinicians describe pregnant patients with severe fetal malformations who have had to overcome financial and logistical barriers to travel to access abortion care. Several cases of patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies have been submitted, including cases that are being followed expectantly, which is inconsistent with the standard of care.10 We also have received several submissions about cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes in the second trimester where the patient was sent home and presented several days later with a severe infection requiring management in the intensive care unit. Cases of early pregnancy loss that could have been treated safely and routinely also were delayed, increasing the risk to patients who, in addition to receiving substandard medical care, had the trauma of fearing they could be prosecuted for receiving treatment.

We hope these data will be useful to document the impact of the Court’s decision and to improve patient care as health care institutions work to update their policies and protocols to reduce delays in care in the face of legal ambiguities. If you have been involved in such a case since June 2022, including caring for a patient who traveled from another state, please consider submitting it at CarePostRoe.com, and please spread the word through your networks.

- McCann A, Schoenfeld Walker A, Sasani A, et al. Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. May 24, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com /interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade .html

- Nash E, Ephross P. State policy trends 2022: in a devastating year, US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe leads to bans, confusion and chaos. Guttmacher Institute website. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org/2022/12/state -policy-trends-2022-devastating-year-us -supreme-courts-decision-overturn-roe-leads

- Cha AE. Physicians face confusion and fear in post-Roe world. Washington Post. June 28, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www .washingtonpost.com/health/2022/06/28 /abortion-ban-roe-doctors-confusion/

- Zernike K. Medical impact of Roe reversal goes well beyond abortion clinics, doctors say. New York Times. September 10, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes .com/2022/09/10/us/abortion-bans-medical -care-women.html

- Abrams A. ‘Never-ending nightmare.’ an Ohio woman was forced to travel out of state for an abortion. Time. August 29, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://time.com/6208860/ohio -woman-forced-travel-abortion/