User login

Cardiac Biomarkers: Current Standards, Future Trends

Since the 1950s, researchers and clinicians have sought a simple chemical biomarker that would aid in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD). An initial discovery was that proteins normally found within cardiac myocytes are released into the circulation when the myocardial cell membrane loses its integrity as a result of hypoxic injury.1 Over the past 60 years, major advances have been made to distinguish which proteins are highly cardiac specific, and which are suggestive of other pathologic cardiovascular processes.

In the past 15 to 20 years, significant data have emerged that support the role of cardiac-specific troponins in the cardiac disease process, making their measurement an important consideration in diagnosis and clinical decision-making for patients with various forms of CVD.2-7 With the exception of 1918, CVD has accounted for more deaths in the United States than any other illness in every year since 1900.8 It has been suggested that nearly 2,300 Americans die of CVD each day—an average of one death every 38 seconds. The direct and indirect costs of CVD for 2010 were projected at $503.2 billion—including $155 billion for total hospital costs alone.9 By comparison, a 2010 projection from the National Cancer Institute was $124.57 billion for the direct costs of cancer care.10

It is imperative for practitioners in all areas of medicine to have a working knowledge of the role of cardiac biomarkers and their potential impact on patients’ overall health. Primary care clinicians in particular should be familiar with the release kinetics of certain cardiac biomarkers to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of the cardiac patient. This article is intended as an overview of the cardiac biomarkers that are being used in practice today, and to review the novel biomarkers that may have an impact on the way clinicians practice in the near future.

BIOMARKERS CURRENTLY IN USE

Cardiac Troponins

The cardiac-specific troponins (cTn) are an integral component of the myosin-actin binding complex found in striated muscle tissue. The troponin complex includes three regulatory proteins: troponin C, troponin I, and troponin T. The genes that code for troponin C are identical in skeletal and cardiac tissue; for this reason, troponin C becomes much less cardiospecific.

However, cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) have differing amino acid sequences, making it possible to develop highly sensitive immunoassays to detect circulating antibody-troponin complexes after myocardial cell injury, as seen in acute coronary syndrome (ACS).12-14 No cross-reactivity occurs between skeletal and cardiac sources, indicating the unique cardiospecificity of the cTn proteins.11

Of note, there are numerous patient populations in which elevated cTn may be found; the associated conditions are outlined in Table 1.11,15,16 In particular, elevations in cTn (more specifically cTnT) are commonly observed in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).11,17 The pathogenesis of elevated cTnT is not completely understood but has been proposed as a promising prognostic tool for use in patients with ESRD. Elevated levels of cTnT identify patients whose chance of survival is poor, with an increased risk for cardiac death.7 It should be noted that a significant proportion of patients with chronic renal failure succumb to cardiovascular death.17

Recently, deFilippi and colleagues18 reported a correlation between trace amounts of circulating cTnT in older patients not known to have CVD and an increased risk for future heart failure or even cardiovascular-related death. This novel finding may add valuable information to the screening and risk stratification of relatively healthy but sedentary individuals older than 65.

Elevations in cTn can be seen as early as two to four hours after myocardial injury.11 A small portion of cTnT and cTnI is found within the myocardial cells’ cytosol and is not bound to the troponin complex, which begins to degrade after cell injury.1,14 This cytosolic pool allows for earlier recognition of cardiac injury. As increasingly sensitive assays are developed, rises in cTn levels can be detected earlier after symptom onset, thus making the use of less specific early biomarkers, such as myoglobin and creatine kinase–MB, obsolete.

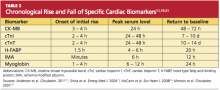

Because of the continuous release of structural proteins from the degrading myocardial tissue, elevations of cTnI may persist for seven to 10 days, while cTnT elevations can continue for 10 to 14 days postinfarction.11 This prolonged period allows for detection of even very slight cardiac damage and provides an advantage for identification and treatment of high-risk patients. When measured 72 hours after infarction, cTnI can also provide prognostic information, such as the potential size of the affected myocardial area.5,6 This, too, facilitates risk stratification. Timing of the release of key biomarkers can be seen in Table 2.11,19-21

Natriuretic Peptides

The natriuretic peptides are cardiac neurohormones that are released in response to myocardial wall stress.11 B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP; previously known as brain natriuretic peptide) is synthesized and released from the ventricular myocardium in times of volume expansion and increased pressure burden. Initially, the prohormone proBNP is released and is enzymatically cleaved to N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) and then to “mature” BNP.11

Today, BNP is used widely as a biomarker for congestive heart failure.22 In the Breathing Not Properly (BNP) study,23 BNP was able to accurately distinguish dyspnea caused by heart failure from that with a pulmonary etiology; it was found to be the strongest predictor for the diagnosis of heart failure. In the evaluation of serum BNP, a level below 100 ng/L makes heart failure unlikely (negative predictive value, 90%). If the value rises above 500 ng/L, heart failure is highly likely (positive predictive value, 90%).23

As for NT-proBNP, levels exceeding 450 ng/L in patients younger than 50 and exceeding 900 ng/L in patients 50 or older have been found highly sensitive and specific for heart failure–related dyspnea.24 Current studies suggest that NT-proBNP may have greater sensitivity and specificity than standard BNP when these age-related cut-off limits are applied.25

Researchers for the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study reported that when NT-proBNP was measured in the emergency department (ED) in patients with dyspnea, patients were less likely to require hospitalization for heart failure.26 Instead, patients were presenting with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which would best be managed on an outpatient basis. Those who were admitted experienced shorter lengths of stay with subsequent reductions in health care costs, and had no significant difference in readmission or mortality rates.

Use of BNP as a cardiac biomarker does not come without its limitations. In addition to right-sided heart failure, ACS, and MI, elevations in BNP have been associated with septic shock, sepsis, renal dysfunction, and acute pulmonary embolus.27 Correlations have been made between the degree of BNP elevation and the extent of myocardial ischemia; increased levels of both BNP and cTnI were associated with higher mortality rates.28

C-Reactive Protein

Inflammation is known to play a key role in the development of atherosclerotic plaques. Measuring byproducts of the atherosclerotic process, from the initial development of fatty streaks to plaque rupture, can help determine whether a patient is at an increased risk for a cardiovascular event.29 Primary proinflammatory markers from the local site of intravascular inflammation signal messenger cytokines that are altered in the liver via an acute-phase reaction.

One of the major acute-phase reactants, C-reactive protein (CRP) is simply a byproduct of inflammation—yet it has become a major indicator of atherosclerotic plaque stability.30 A high-sensitivity CRP assay (hsCRP) can be a significantly effective predictor for MI, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, even in patients who appear to be healthy.31 Studies have suggested that hsCRP is a better indicator of unstable plaque, and a better predictor of adverse cardiovascular events, than is low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), when these markers are used independently.32 When detected together, however, hsCRP and LDL-C elevations have been shown to be an even better predictor of adverse events in patients with no overt cardiovascular risk factors.31

As a risk factor, elevated hsCRP has been called as important as smoking or hypertension—highlighting the role of inflammation in formation of atherosclerosis at every level.33

In the evaluation of serum hsCRP, it is important to know that levels tend to be stable over long periods of time, have no circadian rhythms, and are not affected by various prandial states. Levels can be measured conveniently during the standard annual cholesterol screening. Relative cardiovascular risk is deemed low, medium, and high, in patients with an hsCRP measurement of less than 1 mg/L, 1 to 3 mg/L, and greater than 3 mg/L, respectively.2 Values exceeding 8.0 mg/L may be consistent with an acute infectious or inflammatory process, thus exposing the nonspecific nature of this popular biomarker.34 However, when used in conjunction with cTn, BNP, and patient history, hsCRP still proves to be an important clinical tool, offering prognostic information to facilitate clinical decision making.

Chronically elevated hsCRP signifies a very high risk for future cardiovascular events and should prompt the clinician to target the patient’s modifiable risk factors, including consideration of statin therapy as a part of the treatment regimen.35 According to results from the PROVE IT–TIMI 22 trial,35 statin use appears particularly cardioprotective in patients whose hsCRP levels are lower than 2 mg/L and who maintain LDL-C below 70 mg/dL. Researchers for this study group recommend monitoring hsCRP along with serum lipids for a more comprehensive cardiovascular risk profile.

Creatine Kinase

Three isoenzymes of creatine kinase (CK) exist: MM (skeletal muscle type), BB (brain type), and MB (myocardial band). The CK-MB isoenzyme was the diagnostic marker of choice for ACS until the introduction of cardiac-specific troponins in the early 1990s.36,37

CK-MB is an intracellular carrier protein for high-energy phosphates, found in higher concentrations in the myocardium than are the other CK isoenzymes.11 CK-MB accounts for about 15% of total CK, but it also exists in skeletal muscle and to a lesser extent in the small intestine, diaphragm, uterus, and prostate.21 As with most cardiac biomarkers, cardiospecificity of CK-MB is not 100%, and false-positive elevations can occur in a multitude of clinical settings, including significant musculoskeletal injury, heavy exertion, and myopathies.11

CK-MB is detectable three to four hours after myocardial injury, peaks at 24 hours, and returns to normal in 48 to 72 hours. CK-MB may be used to evaluate for ACS if cardiac troponin assays are not accessible,21 but its usefulness is limited during the early hours of ACS onset and after 72 hours.

The relative index of CK-MB to total CK (CK-MB/CK) can help the clinician assess whether the rise in CK-MB is attributable to a skeletal muscle source (CK-MB/CK < 3) or a cardiac source (CK-MB/CK > 5, indicating myocardial release of CK-MB). A relative index that falls between 3 and 5 warrants further investigation with serial analyses.36 It may also be helpful to know that a CK-MB elevation associated with skeletal muscle release tends to persist and plateau over a period of several days—as opposed to CK-MB elevation with a myocardial source, which follows the time course stated above.21

In a 2006 study that included nearly 30,000 patients, it was found that 28% of those with ACS had conflicting results between troponin levels and CK-MB.38 Patients with no elevations in cardiac troponins but elevations in CK-MB had no significant increased risk for in-hospital mortality, compared with patients with negative results for both markers. Thus, an isolated elevation in CK-MB has limited prognostic value in patients with negative troponin levels.

By contrast, however, Lim et al39 recently found that elevations in CK-MB were closely associated with perioperative necrosis and MI after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as a result of currently oversensitive thresholds for cTnI. Thus, CK-MB use may play a role as an independent marker of necrosis in certain situations.

Myoglobin

Because of its small molecular size, myoglobin has timely release kinetics, with elevations appreciable before those of CK-MB or cTn.11,21 Myoglobin typically rises one to four hours after myocardial injury, peaks at six to 12 hours, and returns to normal within 24 hours. For this reason, it has held special interest as an early marker of cardiac injury.

With its early release/degradation kinetics, myoglobin may serve as a marker for reinfarction.21 It can also be used to assess further damage to the myocardium, as seen with distal thrombus embolization or coronary artery manipulation. However, troponin values provide similar information on reinfarction status.4

An established shortcoming of myoglobin as an early marker of necrosis is its lack of cardiac specificity, as it is found extensively in skeletal muscle.21 Patients who present with inflammation, trauma, or significant skeletal muscle injury can have extremely high levels of serum myoglobin without myocardial involvement. Since 2000, when cTn was designated the myocardial biomarker of choice (according to the revised definition of MI, as presented that year by the European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology), the use of myoglobin to identify ACS has been considered obsolete.14

NOVEL BIOMARKERS OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Heart-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein

A low–molecular-weight protein, heart-type fatty acid–binding protein (H-FABP) is involved in the intracellular uptake and buffering of myocardial free fatty acids. Because its molecular size is similar to that of troponin, it is rapidly released from the cytosol and has been proposed as an early sensitive marker of acute MI.40 In a 2010 study, H-FABP was shown to be of additional prognostic value when used in conjunction with cTnI in patients at low to moderate risk for suspected ACS.41 According to the known release kinetics of H-FABP after myocardial ischemia or infarct, a rise is detectable as early as 1.5 hours after symptom onset. The marker peaks after four to six hours and, because of rapid renal clearance, returns to baseline within 20 hours.20

Interpreting results may be hindered in the patient with impaired renal function—with not only higher levels, but sustained levels of H-FABP.20 Early assays used antibodies to detect circulating H-FABP levels, but cross-reactivity occurring between other fatty acid–binding protein types have limited the clinical applications of H-FABP testing.20 As more highly specific assays are produced, more practical protocols can be implemented to confirm the presence of ACS in patients presenting early to the ED with apparent ACS.

Ischemia-Modified Albumin

A biomarker that could detect ischemia alone would help identify patients at highest risk for infarction; immediate intervention could then prevent the progression of ACS, as evidenced by rising markers of necrosis. Ischemia-modified albumin (IMA), which is produced rapidly when circulating albumin comes into contact with ischemic myocardial tissue, has been touted as such a biomarker.42

Several changes occur in the human albumin molecule in the presence of ischemia, including its ability to bind transition metals—especially cobalt. This discovery led to the creation of an albumin-cobalt–binding assay, approved by the FDA for rapid detection of myocardial ischemia.19 When artificial ischemia is produced by balloon inflation during percutaneous coronary angioplasty, IMA levels can be detected, using the assay, within minutes of coronary artery occlusion. Levels tend to peak within six hours and can be elevated for as long as 12 hours.19

When IMA is used in conjunction with ECG findings and cTnT levels, a sensitivity of 97% for detecting ACS can be achieved. This could reduce the number of patients being discharged from the ED with occult ACS,43 giving IMA a potentially important precautionary and supplemental role. As with most cardiac biomarkers, IMA alone is not 100% specific for ACS since it is also present in other ischemic conditions, thus hindering its usefulness in clinical practice. Elevations had been reported in patients with liver cirrhosis, uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, obstetric conditions associated with placental ischemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, and cerebrovascular ischemia.44-47

Recent suggestions to use IMA to rule out rather than diagnose ACS show promise, since the absence of this acute-phase reactant should exclude the presence of myocardial ischemia.48 Further studies are needed to determine the exact physiology of IMA production in order to identify its cardiac specificity for clinical use.49

Homocysteine

As a marker of increased cardiovascular risk, homocysteine is thought to have multiple effects on the cardiovascular system. These include endothelial dysfunction, decreased arteriole vasodilation (ie, reduced release of nitric oxide), increased platelet activation, increased production of free radicals, and increased LDL oxidation with arteriole lipid accumulation.50

In patients with severe hyperhomocysteinemia (ie, homocysteine serum levels > 100 mol/L), risk for premature atherothrombosis and venous thromboembolism is increased. In the general public, mildly elevated homocysteine levels (> 15 mol/L) have been attributed to insufficient dietary intake of folic acid. Folate in its natural form has been known to decrease serum homocysteine levels by 25%, if supplemented appropriately with vitamins B6 and B12.50

In recent years, folate deficiency has declined due to enrichment of certain foods with this crucial nutrient, initially mandated to decrease the incidence of neural tube defects in developing embryos. From a cardiovascular standpoint, researchers have been unable to determine whether elevated homocysteine increases CVD risk or is simply a marker of existing disease burden.50 In clinical trials in which subjects took B-vitamins supplemented with folate, homocysteine levels were reduced; yet in one study, stroke risk was not reduced in patients with a history of stroke51; in a second, in-stent restenosis was more common in patients who took the supplement after undergoing angioplasty52; and in a third, patients following the vitamin regimen after a recent acute MI proved to be at higher cardiovascular risk.53

As a result of this conflicting evidence, no recommendations have been made for routine homocysteine screening except in patients with a history of markedly premature atherosclerosis or a family history of early-onset acute MI or stroke.50 Monitoring may be advisable in patients who take a folate antagonist (eg, methotrexate, carbamazepine), considering the risk for folate deficiency and subsequent hyperhomocysteinemia.

ACUTE INFLAMMATORY MARKERS OF PLAQUE RUPTURE OR VULNERABILITY

Myeloperoxidase

Many researchers have taken a particular interest in the acute substances formed as a result of atherothrombotic plaque inflammation or rupture. One such biomarker is myeloperoxidase (MPO), which is thought to be expressed from the degranulation of activated leukocytes found in atherosclerotic plaques. This acute-phase enzyme may convert LDL into a high-uptake form for macrophages, leading to foam cell formation and depletion of nitric oxide, contributing to additional ischemia by way of vasoconstriction.54

Recently, a high systemic MPO level was found to be a more significant marker of plaque at risk for rupture, compared with already-ruptured plaque.55 Although MPO elevations may also occur in a number of inflammatory, infectious, or infiltrative conditions, the association between MPO, inflammation, and oxidative stress supports its use as a marker for plaque that is vulnerable to rupture.56,57

Serum levels of MPO have been shown to predict increased risk for subsequent death or MI in patients who present to the ED with ACS, independent of other cardiac risk factors or cardiac biomarkers. In a 2001 study, Zhang et al54 established an association between elevated MPO levels and angiographically proven coronary atherosclerosis, with a 20-fold higher risk for coronary artery disease; earlier this year, Oemrawsingh et al58 reported an independent association between MPO and long-term adverse outcomes in patients who presented with non–ST-segment elevation ACS. Thus, MPO may be a significant indicator of vascular inflammation.57

Soluble CD40 Ligand

In the 1980s, postmortem studies confirmed that erosions or ruptures in atherosclerotic fibrous caps lead to platelet activation—the main pathophysiologic contributor in ACS.59 This fundamental actuality suggests that biomarkers of platelet activation may provide supplemental information in patients who present with chest pain of cardiac origin. Another acute inflammatory marker, soluble CD40 ligand, is a marker of active platelet stimulation.60 Increased serum levels of soluble CD40 ligand have been correlated to increased risk for cardiovascular events in apparently healthy women.61

Soluble CD40 ligand, expressed within seconds of platelet activation, is also commonly found on various leukocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth-muscle cells.60 This may provide insight into cardiovascular disease progression and plaque deterioration that precedes the events of ACS.

Therapeutic antiplatelet medications are now the mainstay in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular complications associated with ischemic thrombus formation.11 Platelet biomarkers are likely to play an essential supplemental role in the diagnosis of ACS.

Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein A

Additional risk-stratifying biomarkers include those that may determine whether a patient has plaques that are acutely vulnerable to rupture. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), first detected in the 1970s in the circulation of pregnant women, is now widely used in first-trimester screening for fetal trisomy.62

Since then, it has been found that PAPP-A, which is theorized to be produced by vascular smooth-muscle cells, is extensively expressed in unstable coronary artery plaques, while minimally expressed in stable plaques.63 Since a significant proportion of patients who present with symptoms of ACS have normal cTn levels, PAPP-A may help identify patients who are at increased risk for subsequent short-term cardiovascular complications resulting from occult disease.64 This relatively new marker may also prove useful for screening in the office setting, identifying outpatients who are at high cardiovascular risk. Further studies are needed to define the release kinetics of PAPP-A, guiding clinicians in its implementation and clinical use.

CONCLUSION

When used in conjunction with the history and physical exam, cardiac biomarkers can provide a simple, noninvasive means to further the clinician’s exploration into a suspected underlying cardiovascular process. As advances continue in the understanding of the pathogenesis of heart disease, new interpretations of existing markers and discovery of novel markers may allow for specific therapeutic interventions to improve patient outcomes.

It is important to note that the list of biomarkers described here is by no means complete, and there is continued interest in finding more specific and sensitive markers of heart disease. Numerous cardiovascular organizations are now suggesting a shift toward a multi-marker strategy to determine the best etiology in the patient who presents with decompensating cardiovascular disease. A change in cardiac enzyme panels may be inevitable in the near future. Practicing PAs and NPs, particularly those who care for patients at risk for CVD, should remain up-to-date and proficient in interpreting those results to help determine the best course of action for each patient.

REFERENCES

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(22):2634-2653.

2. Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003; 107(3):499-511.

3. Kavsak PA, MacRae AR, Newman AM, et al. Effects of contemporary troponin assay sensitivity on the utility of the early markers myoglobin and CKMB isoforms in evaluating patients with possible acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chim Acta. 2007; 380(1-2):213-216.

4. Eggers KM, Oldgren J, Nordenskjöld A, Lindahl B. Diagnostic value of serial measurement of cardiac markers in patients with chest pain: limited value of adding myoglobin to troponin I for exclusion of myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004; 148(4):574-581.

5. Licka M, Zimmermann R, Zehelein J, et al. Troponin T concentrations 72 hours after myocardial infarction as a serological estimate of infarct size. Heart. 2002;87(6):520-524.

6. Panteghini M, Cuccia C, Bonetti G, et al. Single-point cardiac troponin T at coronary care unit discharge after myocardial infarction correlates with infarct size and ejection fraction. Clin Chem. 2002; 48(9):1432-1436.

7. Giannitsis E, Müller-Bardorff M, Lehrke S, et al. Admission troponin T level predicts clinical outcomes, TIMI flow, and myocardial tissue perfusion after primary percutaneous intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(6):630-635.

8. Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25-e146.

9. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010; 121(7):e46-e215.

10. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128.

11. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(18):e426-e579.

12. Ohman EM, Armstrong PW, Christenson RH, et al; GUSTO IIA Investigators. Cardiac troponin T levels for risk stratification in acute myocardial ischemia.

N Engl J Med. 1996;335(18):1333-1341.

13. Antman EM, Tanasijevic MJ, Thompson B, et al. Cardiac-specific troponin I levels to predict the risk of mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(18):1342-1349.

14. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959-969.

15. Jaffe AS, Babuin L, Apple FS. Biomarkers in acute cardiac disease: the present and the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(1):1-11.

16. Galvani M, Ottani F, Ferrini D, et al. Prognostic influence of elevated values of cardiac troponin I in patients with unstable angina. Circulation. 1997;95 (8):2053-2059.

17. Freda BJ, Tang WH, Van Lente F, et al. Cardiac troponins in renal insufficiency: review and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(12):2065-2071.

18. deFilippi CR, de Lemos JA, Christenson RH, et al. Association of serial measures of cardiac troponin T using a sensitive assay with incident heart failure and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2494-2502.

19. Sinha MK, Roy D, Gaze DC, et al. Role of “ischemia modified albumin,” a new biochemical marker of myocardial ischaemia, in the early diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Emerg Med J. 2004; 21(1):29-34.

20. McCann CJ, Glover BM, Menown IB, et al. Novel biomarkers in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction compared with cardiac troponin T. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(23):2843-2850.

21. Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2007;115(13): e356-e375.

22. Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al; Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study Investigators. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):161-167.

23. McCullough PA, Nowak RM, McCord J, et al: B-type natriuretic peptide and clinical judgment in emergency diagnosis of heart failure: analysis from Breathing Not Properly (BNP) Multinational Study. Circulation. 2002;106(4):416-422.

24. Januzzi JL Jr, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S, et al. The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(8):948-954.

25. Mueller C, Laule-Kilian K, Scholer A, et al. Use of B-type natriuretic peptide for the management of women with dyspnea. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 94(12):1510-1514.

26. Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(3):330-337.

27. Maisel AS. The diagnosis of acute congestive heart failure: role of BNP measurements. Heart Fail Rev. 2003;8(4):327-334.

28. Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Sabatine MS, et al. Evaluation of B-type natriuretic peptide for risk assessment in unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: B-type natriuretic peptide and prognosis in TACTICS-TIMI 18. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(8):1264-1272.

29. Libby P, Ridker PM. Inflammation and atherothrombosis: from population biology and bench research to clinical practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48(9 suppl A):A33-A46.

30. Ridker PM. Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation. 2003;107(3):363-369.

31. Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, et al. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1557-1565.

32. Boekholdt SM, Hack CE, Sandhu MS, et al. C-reactive protein levels and coronary artery disease incidence and mortality in apparently healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study 1993-2003. Atherosclerosis. 2006; 187(2):415-422.

33. Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1387-1397.

34. Ridker PM, Cook N. Clinical usefulness of very high and very low levels of C-reactive protein across the full range of Framingham Risk Scores. Circulation. 2004;109(16):1955-1959.

35. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombosis in Myocardial Infarction 22 (PROVE IT-TIMI 22) Investigators. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(1):20-28.

36. Fischer JH, Jeschkeit-Schubbert S, Kuhn-Régnier F, Switkowski R. The origin of CK-MB serum levels and CK-MB/total CK ratios: measurements of CK isoenzyme activities in various tissues. Internet J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;7(1).

37. Adams JE 3rd, Abendschein DR, Jaffe AS. Biochemical markers of myocardial injury: is MB creatine kinase the choice for the 1990s? Circulation. 1993;88(2):750-763.

38. Newby LK, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al; CRUSADE Investigators. Frequency and clinical implications of discordant creatine kinase-MB and troponin measurements in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(2):312-318.

39. Lim CC, van Gaal WJ, Testa L, et al. With the “universal definition,” measurement of creatine kinase–myocardial band rather than troponin allows more accurate diagnosis of periprocedural necrosis and infarction after coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(6):653-661.

40. Kilcullen N, Viswanathan K, Das R, et al; EMMACE-2 Investigators. Heart-type fatty acid–binding protein predicts long-term mortality after acute coronary syndrome and identifies high-risk patients across the range of troponin values. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(21):2061-2067.

41. Viswanathan K, Kilcullen N, Morrell C, et al. Heart-type fatty acid–binding protein predicts long-term mortality and re-infarction in consecutive patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome who are troponin-negative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55(23): 2590-2598.

42. Abadie JM, Blassingame CL, Bankson DD. Albumin cobalt binding assay to rule out acute coronary syndrome. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2005;35(1):66-72.

43. Anwaruddin S, Januzzi JL Jr, Baggish AL, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin improves the usefulness of standard cardiac biomarkers for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia in the emergency department setting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123(1):140-145.

44. Piwowar A, Knapik-Kordecka M, Warwas M. Ischemia-modified albumin level in type 2 diabetes mellitus: preliminary report. Dis Markers. 2008; 24(6):311-317.

45. Prefumo F, Gaze DC, Papageorghiou AT, et al. First trimester maternal serum ischaemia-modified albumin: a marker of hypoxia-ischaemia-driven early trophoblast development. Hum Reprod. 2007; 22(7):2029-2032.

46. Gunduz A, Turedi S, Mentese A, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin levels in cerebrovascular accidents. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(8):874-878.

47. Turedi S, Cinar O, Kaldirim U, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin levels in carbon monoxide poisoning. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(6):675-681.

48. Sbarouni E, Georgiadou P, Voudris V. Ischemia modified albumin changes: review and clinical implications. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49(2):177-184.

49. Gaze DC. Ischemia modified albumin: a novel biomarker for the detection of cardiac ischemia. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24(4):333-341.

50. Kaul S, Zadeh AA, Shah PK. Homocysteine hypothesis for atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease: not validated. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48(5):914-923.

51. Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, et al. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(5):565-575.

52. Lange H, Suryapranata H, De Luca G, et al. Folate therapy and in-stent restenosis after coronary stenting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2673-2681.

53. Bønaa KH, Njølstad I, Ueland PM, et al; NORVIT Trial Investigators. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1578-1588.

54. Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, et al. Association between myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2001;286(17):2136-2142.

55. Ferrante G, Nakano M, Prati F, et al. High levels of systemic myeloperoxidase are associated with coronary plaque erosion in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a clinicopathological study. Circulation. 2010;122(24):2505-2513.

56. Loria V, Dato I, Graziani F, Biasucci LM. Myeloperoxidase: a new biomarker of inflammation in ischemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes. Mediators Inflamm. 2008;2008:135625.

57. Apple FS, Wu AH, Mair J, et al; Committee on Standardization of Markers of Cardiac Damage of the IFCC. Future biomarkers for detection of ischemia and risk stratification in acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chem. 2005;51(5):810-824.

58. Oemrawsingh RM, Lenderink T, Akkerhuis KM, et al. Multimarker risk model containing troponin-T, interleukin 10, myeloperoxidase and placental growth factor predicts long-term cardiovascular risk after non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2011;97(13):1061-1066.

59. Davies MJ, Thomas AC. Plaque fissuring: the cause of acute myocardial infarction, sudden ischaemic death, and crescendo angina. Br Heart J. 1985;53(4):363-373.

60. Heeschen C, Dimmeler S, Hamm CW, et al; CAPTURE Study. Soluble CD40 ligand in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12): 1104-1111.

61. Schönbeck U, Varo N, Libby P, et al. Soluble CD40L and cardiovascular risk in women. Circulation. 2001;104(19):2266-2268.

62. Lin TM, Galbert SP, Kiefer D, et al. Characterization of four human pregnancy–associated plasma proteins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974; 118(2):223-236.

63. Bayes-Genis A, Conover CA, Overgaard MT, et al. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A as a marker of acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(14):1022-1029.

64. Lund J, Qin QP, Ilva T, et al. Circulating pregnancy-associated plasma protein A predicts outcome in patients with acute coronary syndrome but no troponin I elevation. Circulation. 2003; 108(16):1924-1926.

Since the 1950s, researchers and clinicians have sought a simple chemical biomarker that would aid in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD). An initial discovery was that proteins normally found within cardiac myocytes are released into the circulation when the myocardial cell membrane loses its integrity as a result of hypoxic injury.1 Over the past 60 years, major advances have been made to distinguish which proteins are highly cardiac specific, and which are suggestive of other pathologic cardiovascular processes.

In the past 15 to 20 years, significant data have emerged that support the role of cardiac-specific troponins in the cardiac disease process, making their measurement an important consideration in diagnosis and clinical decision-making for patients with various forms of CVD.2-7 With the exception of 1918, CVD has accounted for more deaths in the United States than any other illness in every year since 1900.8 It has been suggested that nearly 2,300 Americans die of CVD each day—an average of one death every 38 seconds. The direct and indirect costs of CVD for 2010 were projected at $503.2 billion—including $155 billion for total hospital costs alone.9 By comparison, a 2010 projection from the National Cancer Institute was $124.57 billion for the direct costs of cancer care.10

It is imperative for practitioners in all areas of medicine to have a working knowledge of the role of cardiac biomarkers and their potential impact on patients’ overall health. Primary care clinicians in particular should be familiar with the release kinetics of certain cardiac biomarkers to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of the cardiac patient. This article is intended as an overview of the cardiac biomarkers that are being used in practice today, and to review the novel biomarkers that may have an impact on the way clinicians practice in the near future.

BIOMARKERS CURRENTLY IN USE

Cardiac Troponins

The cardiac-specific troponins (cTn) are an integral component of the myosin-actin binding complex found in striated muscle tissue. The troponin complex includes three regulatory proteins: troponin C, troponin I, and troponin T. The genes that code for troponin C are identical in skeletal and cardiac tissue; for this reason, troponin C becomes much less cardiospecific.

However, cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) have differing amino acid sequences, making it possible to develop highly sensitive immunoassays to detect circulating antibody-troponin complexes after myocardial cell injury, as seen in acute coronary syndrome (ACS).12-14 No cross-reactivity occurs between skeletal and cardiac sources, indicating the unique cardiospecificity of the cTn proteins.11

Of note, there are numerous patient populations in which elevated cTn may be found; the associated conditions are outlined in Table 1.11,15,16 In particular, elevations in cTn (more specifically cTnT) are commonly observed in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).11,17 The pathogenesis of elevated cTnT is not completely understood but has been proposed as a promising prognostic tool for use in patients with ESRD. Elevated levels of cTnT identify patients whose chance of survival is poor, with an increased risk for cardiac death.7 It should be noted that a significant proportion of patients with chronic renal failure succumb to cardiovascular death.17

Recently, deFilippi and colleagues18 reported a correlation between trace amounts of circulating cTnT in older patients not known to have CVD and an increased risk for future heart failure or even cardiovascular-related death. This novel finding may add valuable information to the screening and risk stratification of relatively healthy but sedentary individuals older than 65.

Elevations in cTn can be seen as early as two to four hours after myocardial injury.11 A small portion of cTnT and cTnI is found within the myocardial cells’ cytosol and is not bound to the troponin complex, which begins to degrade after cell injury.1,14 This cytosolic pool allows for earlier recognition of cardiac injury. As increasingly sensitive assays are developed, rises in cTn levels can be detected earlier after symptom onset, thus making the use of less specific early biomarkers, such as myoglobin and creatine kinase–MB, obsolete.

Because of the continuous release of structural proteins from the degrading myocardial tissue, elevations of cTnI may persist for seven to 10 days, while cTnT elevations can continue for 10 to 14 days postinfarction.11 This prolonged period allows for detection of even very slight cardiac damage and provides an advantage for identification and treatment of high-risk patients. When measured 72 hours after infarction, cTnI can also provide prognostic information, such as the potential size of the affected myocardial area.5,6 This, too, facilitates risk stratification. Timing of the release of key biomarkers can be seen in Table 2.11,19-21

Natriuretic Peptides

The natriuretic peptides are cardiac neurohormones that are released in response to myocardial wall stress.11 B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP; previously known as brain natriuretic peptide) is synthesized and released from the ventricular myocardium in times of volume expansion and increased pressure burden. Initially, the prohormone proBNP is released and is enzymatically cleaved to N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) and then to “mature” BNP.11

Today, BNP is used widely as a biomarker for congestive heart failure.22 In the Breathing Not Properly (BNP) study,23 BNP was able to accurately distinguish dyspnea caused by heart failure from that with a pulmonary etiology; it was found to be the strongest predictor for the diagnosis of heart failure. In the evaluation of serum BNP, a level below 100 ng/L makes heart failure unlikely (negative predictive value, 90%). If the value rises above 500 ng/L, heart failure is highly likely (positive predictive value, 90%).23

As for NT-proBNP, levels exceeding 450 ng/L in patients younger than 50 and exceeding 900 ng/L in patients 50 or older have been found highly sensitive and specific for heart failure–related dyspnea.24 Current studies suggest that NT-proBNP may have greater sensitivity and specificity than standard BNP when these age-related cut-off limits are applied.25

Researchers for the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study reported that when NT-proBNP was measured in the emergency department (ED) in patients with dyspnea, patients were less likely to require hospitalization for heart failure.26 Instead, patients were presenting with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which would best be managed on an outpatient basis. Those who were admitted experienced shorter lengths of stay with subsequent reductions in health care costs, and had no significant difference in readmission or mortality rates.

Use of BNP as a cardiac biomarker does not come without its limitations. In addition to right-sided heart failure, ACS, and MI, elevations in BNP have been associated with septic shock, sepsis, renal dysfunction, and acute pulmonary embolus.27 Correlations have been made between the degree of BNP elevation and the extent of myocardial ischemia; increased levels of both BNP and cTnI were associated with higher mortality rates.28

C-Reactive Protein

Inflammation is known to play a key role in the development of atherosclerotic plaques. Measuring byproducts of the atherosclerotic process, from the initial development of fatty streaks to plaque rupture, can help determine whether a patient is at an increased risk for a cardiovascular event.29 Primary proinflammatory markers from the local site of intravascular inflammation signal messenger cytokines that are altered in the liver via an acute-phase reaction.

One of the major acute-phase reactants, C-reactive protein (CRP) is simply a byproduct of inflammation—yet it has become a major indicator of atherosclerotic plaque stability.30 A high-sensitivity CRP assay (hsCRP) can be a significantly effective predictor for MI, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, even in patients who appear to be healthy.31 Studies have suggested that hsCRP is a better indicator of unstable plaque, and a better predictor of adverse cardiovascular events, than is low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), when these markers are used independently.32 When detected together, however, hsCRP and LDL-C elevations have been shown to be an even better predictor of adverse events in patients with no overt cardiovascular risk factors.31

As a risk factor, elevated hsCRP has been called as important as smoking or hypertension—highlighting the role of inflammation in formation of atherosclerosis at every level.33

In the evaluation of serum hsCRP, it is important to know that levels tend to be stable over long periods of time, have no circadian rhythms, and are not affected by various prandial states. Levels can be measured conveniently during the standard annual cholesterol screening. Relative cardiovascular risk is deemed low, medium, and high, in patients with an hsCRP measurement of less than 1 mg/L, 1 to 3 mg/L, and greater than 3 mg/L, respectively.2 Values exceeding 8.0 mg/L may be consistent with an acute infectious or inflammatory process, thus exposing the nonspecific nature of this popular biomarker.34 However, when used in conjunction with cTn, BNP, and patient history, hsCRP still proves to be an important clinical tool, offering prognostic information to facilitate clinical decision making.

Chronically elevated hsCRP signifies a very high risk for future cardiovascular events and should prompt the clinician to target the patient’s modifiable risk factors, including consideration of statin therapy as a part of the treatment regimen.35 According to results from the PROVE IT–TIMI 22 trial,35 statin use appears particularly cardioprotective in patients whose hsCRP levels are lower than 2 mg/L and who maintain LDL-C below 70 mg/dL. Researchers for this study group recommend monitoring hsCRP along with serum lipids for a more comprehensive cardiovascular risk profile.

Creatine Kinase

Three isoenzymes of creatine kinase (CK) exist: MM (skeletal muscle type), BB (brain type), and MB (myocardial band). The CK-MB isoenzyme was the diagnostic marker of choice for ACS until the introduction of cardiac-specific troponins in the early 1990s.36,37

CK-MB is an intracellular carrier protein for high-energy phosphates, found in higher concentrations in the myocardium than are the other CK isoenzymes.11 CK-MB accounts for about 15% of total CK, but it also exists in skeletal muscle and to a lesser extent in the small intestine, diaphragm, uterus, and prostate.21 As with most cardiac biomarkers, cardiospecificity of CK-MB is not 100%, and false-positive elevations can occur in a multitude of clinical settings, including significant musculoskeletal injury, heavy exertion, and myopathies.11

CK-MB is detectable three to four hours after myocardial injury, peaks at 24 hours, and returns to normal in 48 to 72 hours. CK-MB may be used to evaluate for ACS if cardiac troponin assays are not accessible,21 but its usefulness is limited during the early hours of ACS onset and after 72 hours.

The relative index of CK-MB to total CK (CK-MB/CK) can help the clinician assess whether the rise in CK-MB is attributable to a skeletal muscle source (CK-MB/CK < 3) or a cardiac source (CK-MB/CK > 5, indicating myocardial release of CK-MB). A relative index that falls between 3 and 5 warrants further investigation with serial analyses.36 It may also be helpful to know that a CK-MB elevation associated with skeletal muscle release tends to persist and plateau over a period of several days—as opposed to CK-MB elevation with a myocardial source, which follows the time course stated above.21

In a 2006 study that included nearly 30,000 patients, it was found that 28% of those with ACS had conflicting results between troponin levels and CK-MB.38 Patients with no elevations in cardiac troponins but elevations in CK-MB had no significant increased risk for in-hospital mortality, compared with patients with negative results for both markers. Thus, an isolated elevation in CK-MB has limited prognostic value in patients with negative troponin levels.

By contrast, however, Lim et al39 recently found that elevations in CK-MB were closely associated with perioperative necrosis and MI after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as a result of currently oversensitive thresholds for cTnI. Thus, CK-MB use may play a role as an independent marker of necrosis in certain situations.

Myoglobin

Because of its small molecular size, myoglobin has timely release kinetics, with elevations appreciable before those of CK-MB or cTn.11,21 Myoglobin typically rises one to four hours after myocardial injury, peaks at six to 12 hours, and returns to normal within 24 hours. For this reason, it has held special interest as an early marker of cardiac injury.

With its early release/degradation kinetics, myoglobin may serve as a marker for reinfarction.21 It can also be used to assess further damage to the myocardium, as seen with distal thrombus embolization or coronary artery manipulation. However, troponin values provide similar information on reinfarction status.4

An established shortcoming of myoglobin as an early marker of necrosis is its lack of cardiac specificity, as it is found extensively in skeletal muscle.21 Patients who present with inflammation, trauma, or significant skeletal muscle injury can have extremely high levels of serum myoglobin without myocardial involvement. Since 2000, when cTn was designated the myocardial biomarker of choice (according to the revised definition of MI, as presented that year by the European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology), the use of myoglobin to identify ACS has been considered obsolete.14

NOVEL BIOMARKERS OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Heart-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein

A low–molecular-weight protein, heart-type fatty acid–binding protein (H-FABP) is involved in the intracellular uptake and buffering of myocardial free fatty acids. Because its molecular size is similar to that of troponin, it is rapidly released from the cytosol and has been proposed as an early sensitive marker of acute MI.40 In a 2010 study, H-FABP was shown to be of additional prognostic value when used in conjunction with cTnI in patients at low to moderate risk for suspected ACS.41 According to the known release kinetics of H-FABP after myocardial ischemia or infarct, a rise is detectable as early as 1.5 hours after symptom onset. The marker peaks after four to six hours and, because of rapid renal clearance, returns to baseline within 20 hours.20

Interpreting results may be hindered in the patient with impaired renal function—with not only higher levels, but sustained levels of H-FABP.20 Early assays used antibodies to detect circulating H-FABP levels, but cross-reactivity occurring between other fatty acid–binding protein types have limited the clinical applications of H-FABP testing.20 As more highly specific assays are produced, more practical protocols can be implemented to confirm the presence of ACS in patients presenting early to the ED with apparent ACS.

Ischemia-Modified Albumin

A biomarker that could detect ischemia alone would help identify patients at highest risk for infarction; immediate intervention could then prevent the progression of ACS, as evidenced by rising markers of necrosis. Ischemia-modified albumin (IMA), which is produced rapidly when circulating albumin comes into contact with ischemic myocardial tissue, has been touted as such a biomarker.42

Several changes occur in the human albumin molecule in the presence of ischemia, including its ability to bind transition metals—especially cobalt. This discovery led to the creation of an albumin-cobalt–binding assay, approved by the FDA for rapid detection of myocardial ischemia.19 When artificial ischemia is produced by balloon inflation during percutaneous coronary angioplasty, IMA levels can be detected, using the assay, within minutes of coronary artery occlusion. Levels tend to peak within six hours and can be elevated for as long as 12 hours.19

When IMA is used in conjunction with ECG findings and cTnT levels, a sensitivity of 97% for detecting ACS can be achieved. This could reduce the number of patients being discharged from the ED with occult ACS,43 giving IMA a potentially important precautionary and supplemental role. As with most cardiac biomarkers, IMA alone is not 100% specific for ACS since it is also present in other ischemic conditions, thus hindering its usefulness in clinical practice. Elevations had been reported in patients with liver cirrhosis, uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, obstetric conditions associated with placental ischemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, and cerebrovascular ischemia.44-47

Recent suggestions to use IMA to rule out rather than diagnose ACS show promise, since the absence of this acute-phase reactant should exclude the presence of myocardial ischemia.48 Further studies are needed to determine the exact physiology of IMA production in order to identify its cardiac specificity for clinical use.49

Homocysteine

As a marker of increased cardiovascular risk, homocysteine is thought to have multiple effects on the cardiovascular system. These include endothelial dysfunction, decreased arteriole vasodilation (ie, reduced release of nitric oxide), increased platelet activation, increased production of free radicals, and increased LDL oxidation with arteriole lipid accumulation.50

In patients with severe hyperhomocysteinemia (ie, homocysteine serum levels > 100 mol/L), risk for premature atherothrombosis and venous thromboembolism is increased. In the general public, mildly elevated homocysteine levels (> 15 mol/L) have been attributed to insufficient dietary intake of folic acid. Folate in its natural form has been known to decrease serum homocysteine levels by 25%, if supplemented appropriately with vitamins B6 and B12.50

In recent years, folate deficiency has declined due to enrichment of certain foods with this crucial nutrient, initially mandated to decrease the incidence of neural tube defects in developing embryos. From a cardiovascular standpoint, researchers have been unable to determine whether elevated homocysteine increases CVD risk or is simply a marker of existing disease burden.50 In clinical trials in which subjects took B-vitamins supplemented with folate, homocysteine levels were reduced; yet in one study, stroke risk was not reduced in patients with a history of stroke51; in a second, in-stent restenosis was more common in patients who took the supplement after undergoing angioplasty52; and in a third, patients following the vitamin regimen after a recent acute MI proved to be at higher cardiovascular risk.53

As a result of this conflicting evidence, no recommendations have been made for routine homocysteine screening except in patients with a history of markedly premature atherosclerosis or a family history of early-onset acute MI or stroke.50 Monitoring may be advisable in patients who take a folate antagonist (eg, methotrexate, carbamazepine), considering the risk for folate deficiency and subsequent hyperhomocysteinemia.

ACUTE INFLAMMATORY MARKERS OF PLAQUE RUPTURE OR VULNERABILITY

Myeloperoxidase

Many researchers have taken a particular interest in the acute substances formed as a result of atherothrombotic plaque inflammation or rupture. One such biomarker is myeloperoxidase (MPO), which is thought to be expressed from the degranulation of activated leukocytes found in atherosclerotic plaques. This acute-phase enzyme may convert LDL into a high-uptake form for macrophages, leading to foam cell formation and depletion of nitric oxide, contributing to additional ischemia by way of vasoconstriction.54

Recently, a high systemic MPO level was found to be a more significant marker of plaque at risk for rupture, compared with already-ruptured plaque.55 Although MPO elevations may also occur in a number of inflammatory, infectious, or infiltrative conditions, the association between MPO, inflammation, and oxidative stress supports its use as a marker for plaque that is vulnerable to rupture.56,57

Serum levels of MPO have been shown to predict increased risk for subsequent death or MI in patients who present to the ED with ACS, independent of other cardiac risk factors or cardiac biomarkers. In a 2001 study, Zhang et al54 established an association between elevated MPO levels and angiographically proven coronary atherosclerosis, with a 20-fold higher risk for coronary artery disease; earlier this year, Oemrawsingh et al58 reported an independent association between MPO and long-term adverse outcomes in patients who presented with non–ST-segment elevation ACS. Thus, MPO may be a significant indicator of vascular inflammation.57

Soluble CD40 Ligand

In the 1980s, postmortem studies confirmed that erosions or ruptures in atherosclerotic fibrous caps lead to platelet activation—the main pathophysiologic contributor in ACS.59 This fundamental actuality suggests that biomarkers of platelet activation may provide supplemental information in patients who present with chest pain of cardiac origin. Another acute inflammatory marker, soluble CD40 ligand, is a marker of active platelet stimulation.60 Increased serum levels of soluble CD40 ligand have been correlated to increased risk for cardiovascular events in apparently healthy women.61

Soluble CD40 ligand, expressed within seconds of platelet activation, is also commonly found on various leukocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth-muscle cells.60 This may provide insight into cardiovascular disease progression and plaque deterioration that precedes the events of ACS.

Therapeutic antiplatelet medications are now the mainstay in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular complications associated with ischemic thrombus formation.11 Platelet biomarkers are likely to play an essential supplemental role in the diagnosis of ACS.

Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein A

Additional risk-stratifying biomarkers include those that may determine whether a patient has plaques that are acutely vulnerable to rupture. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), first detected in the 1970s in the circulation of pregnant women, is now widely used in first-trimester screening for fetal trisomy.62

Since then, it has been found that PAPP-A, which is theorized to be produced by vascular smooth-muscle cells, is extensively expressed in unstable coronary artery plaques, while minimally expressed in stable plaques.63 Since a significant proportion of patients who present with symptoms of ACS have normal cTn levels, PAPP-A may help identify patients who are at increased risk for subsequent short-term cardiovascular complications resulting from occult disease.64 This relatively new marker may also prove useful for screening in the office setting, identifying outpatients who are at high cardiovascular risk. Further studies are needed to define the release kinetics of PAPP-A, guiding clinicians in its implementation and clinical use.

CONCLUSION

When used in conjunction with the history and physical exam, cardiac biomarkers can provide a simple, noninvasive means to further the clinician’s exploration into a suspected underlying cardiovascular process. As advances continue in the understanding of the pathogenesis of heart disease, new interpretations of existing markers and discovery of novel markers may allow for specific therapeutic interventions to improve patient outcomes.

It is important to note that the list of biomarkers described here is by no means complete, and there is continued interest in finding more specific and sensitive markers of heart disease. Numerous cardiovascular organizations are now suggesting a shift toward a multi-marker strategy to determine the best etiology in the patient who presents with decompensating cardiovascular disease. A change in cardiac enzyme panels may be inevitable in the near future. Practicing PAs and NPs, particularly those who care for patients at risk for CVD, should remain up-to-date and proficient in interpreting those results to help determine the best course of action for each patient.

REFERENCES

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(22):2634-2653.

2. Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003; 107(3):499-511.

3. Kavsak PA, MacRae AR, Newman AM, et al. Effects of contemporary troponin assay sensitivity on the utility of the early markers myoglobin and CKMB isoforms in evaluating patients with possible acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chim Acta. 2007; 380(1-2):213-216.

4. Eggers KM, Oldgren J, Nordenskjöld A, Lindahl B. Diagnostic value of serial measurement of cardiac markers in patients with chest pain: limited value of adding myoglobin to troponin I for exclusion of myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004; 148(4):574-581.

5. Licka M, Zimmermann R, Zehelein J, et al. Troponin T concentrations 72 hours after myocardial infarction as a serological estimate of infarct size. Heart. 2002;87(6):520-524.

6. Panteghini M, Cuccia C, Bonetti G, et al. Single-point cardiac troponin T at coronary care unit discharge after myocardial infarction correlates with infarct size and ejection fraction. Clin Chem. 2002; 48(9):1432-1436.

7. Giannitsis E, Müller-Bardorff M, Lehrke S, et al. Admission troponin T level predicts clinical outcomes, TIMI flow, and myocardial tissue perfusion after primary percutaneous intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(6):630-635.

8. Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25-e146.

9. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010; 121(7):e46-e215.

10. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128.

11. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(18):e426-e579.

12. Ohman EM, Armstrong PW, Christenson RH, et al; GUSTO IIA Investigators. Cardiac troponin T levels for risk stratification in acute myocardial ischemia.

N Engl J Med. 1996;335(18):1333-1341.

13. Antman EM, Tanasijevic MJ, Thompson B, et al. Cardiac-specific troponin I levels to predict the risk of mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(18):1342-1349.

14. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959-969.

15. Jaffe AS, Babuin L, Apple FS. Biomarkers in acute cardiac disease: the present and the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(1):1-11.

16. Galvani M, Ottani F, Ferrini D, et al. Prognostic influence of elevated values of cardiac troponin I in patients with unstable angina. Circulation. 1997;95 (8):2053-2059.

17. Freda BJ, Tang WH, Van Lente F, et al. Cardiac troponins in renal insufficiency: review and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(12):2065-2071.

18. deFilippi CR, de Lemos JA, Christenson RH, et al. Association of serial measures of cardiac troponin T using a sensitive assay with incident heart failure and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2494-2502.

19. Sinha MK, Roy D, Gaze DC, et al. Role of “ischemia modified albumin,” a new biochemical marker of myocardial ischaemia, in the early diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Emerg Med J. 2004; 21(1):29-34.

20. McCann CJ, Glover BM, Menown IB, et al. Novel biomarkers in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction compared with cardiac troponin T. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(23):2843-2850.

21. Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2007;115(13): e356-e375.

22. Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al; Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study Investigators. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):161-167.

23. McCullough PA, Nowak RM, McCord J, et al: B-type natriuretic peptide and clinical judgment in emergency diagnosis of heart failure: analysis from Breathing Not Properly (BNP) Multinational Study. Circulation. 2002;106(4):416-422.

24. Januzzi JL Jr, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S, et al. The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(8):948-954.

25. Mueller C, Laule-Kilian K, Scholer A, et al. Use of B-type natriuretic peptide for the management of women with dyspnea. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 94(12):1510-1514.

26. Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(3):330-337.

27. Maisel AS. The diagnosis of acute congestive heart failure: role of BNP measurements. Heart Fail Rev. 2003;8(4):327-334.

28. Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Sabatine MS, et al. Evaluation of B-type natriuretic peptide for risk assessment in unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: B-type natriuretic peptide and prognosis in TACTICS-TIMI 18. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(8):1264-1272.

29. Libby P, Ridker PM. Inflammation and atherothrombosis: from population biology and bench research to clinical practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48(9 suppl A):A33-A46.

30. Ridker PM. Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation. 2003;107(3):363-369.

31. Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, et al. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1557-1565.

32. Boekholdt SM, Hack CE, Sandhu MS, et al. C-reactive protein levels and coronary artery disease incidence and mortality in apparently healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study 1993-2003. Atherosclerosis. 2006; 187(2):415-422.

33. Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1387-1397.

34. Ridker PM, Cook N. Clinical usefulness of very high and very low levels of C-reactive protein across the full range of Framingham Risk Scores. Circulation. 2004;109(16):1955-1959.

35. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombosis in Myocardial Infarction 22 (PROVE IT-TIMI 22) Investigators. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(1):20-28.

36. Fischer JH, Jeschkeit-Schubbert S, Kuhn-Régnier F, Switkowski R. The origin of CK-MB serum levels and CK-MB/total CK ratios: measurements of CK isoenzyme activities in various tissues. Internet J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;7(1).

37. Adams JE 3rd, Abendschein DR, Jaffe AS. Biochemical markers of myocardial injury: is MB creatine kinase the choice for the 1990s? Circulation. 1993;88(2):750-763.

38. Newby LK, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al; CRUSADE Investigators. Frequency and clinical implications of discordant creatine kinase-MB and troponin measurements in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(2):312-318.

39. Lim CC, van Gaal WJ, Testa L, et al. With the “universal definition,” measurement of creatine kinase–myocardial band rather than troponin allows more accurate diagnosis of periprocedural necrosis and infarction after coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(6):653-661.

40. Kilcullen N, Viswanathan K, Das R, et al; EMMACE-2 Investigators. Heart-type fatty acid–binding protein predicts long-term mortality after acute coronary syndrome and identifies high-risk patients across the range of troponin values. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(21):2061-2067.

41. Viswanathan K, Kilcullen N, Morrell C, et al. Heart-type fatty acid–binding protein predicts long-term mortality and re-infarction in consecutive patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome who are troponin-negative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55(23): 2590-2598.

42. Abadie JM, Blassingame CL, Bankson DD. Albumin cobalt binding assay to rule out acute coronary syndrome. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2005;35(1):66-72.

43. Anwaruddin S, Januzzi JL Jr, Baggish AL, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin improves the usefulness of standard cardiac biomarkers for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia in the emergency department setting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123(1):140-145.

44. Piwowar A, Knapik-Kordecka M, Warwas M. Ischemia-modified albumin level in type 2 diabetes mellitus: preliminary report. Dis Markers. 2008; 24(6):311-317.

45. Prefumo F, Gaze DC, Papageorghiou AT, et al. First trimester maternal serum ischaemia-modified albumin: a marker of hypoxia-ischaemia-driven early trophoblast development. Hum Reprod. 2007; 22(7):2029-2032.

46. Gunduz A, Turedi S, Mentese A, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin levels in cerebrovascular accidents. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(8):874-878.

47. Turedi S, Cinar O, Kaldirim U, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin levels in carbon monoxide poisoning. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(6):675-681.

48. Sbarouni E, Georgiadou P, Voudris V. Ischemia modified albumin changes: review and clinical implications. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49(2):177-184.

49. Gaze DC. Ischemia modified albumin: a novel biomarker for the detection of cardiac ischemia. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24(4):333-341.

50. Kaul S, Zadeh AA, Shah PK. Homocysteine hypothesis for atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease: not validated. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48(5):914-923.

51. Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, et al. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(5):565-575.

52. Lange H, Suryapranata H, De Luca G, et al. Folate therapy and in-stent restenosis after coronary stenting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2673-2681.

53. Bønaa KH, Njølstad I, Ueland PM, et al; NORVIT Trial Investigators. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1578-1588.

54. Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, et al. Association between myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2001;286(17):2136-2142.

55. Ferrante G, Nakano M, Prati F, et al. High levels of systemic myeloperoxidase are associated with coronary plaque erosion in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a clinicopathological study. Circulation. 2010;122(24):2505-2513.

56. Loria V, Dato I, Graziani F, Biasucci LM. Myeloperoxidase: a new biomarker of inflammation in ischemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes. Mediators Inflamm. 2008;2008:135625.

57. Apple FS, Wu AH, Mair J, et al; Committee on Standardization of Markers of Cardiac Damage of the IFCC. Future biomarkers for detection of ischemia and risk stratification in acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chem. 2005;51(5):810-824.

58. Oemrawsingh RM, Lenderink T, Akkerhuis KM, et al. Multimarker risk model containing troponin-T, interleukin 10, myeloperoxidase and placental growth factor predicts long-term cardiovascular risk after non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2011;97(13):1061-1066.

59. Davies MJ, Thomas AC. Plaque fissuring: the cause of acute myocardial infarction, sudden ischaemic death, and crescendo angina. Br Heart J. 1985;53(4):363-373.

60. Heeschen C, Dimmeler S, Hamm CW, et al; CAPTURE Study. Soluble CD40 ligand in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12): 1104-1111.

61. Schönbeck U, Varo N, Libby P, et al. Soluble CD40L and cardiovascular risk in women. Circulation. 2001;104(19):2266-2268.

62. Lin TM, Galbert SP, Kiefer D, et al. Characterization of four human pregnancy–associated plasma proteins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974; 118(2):223-236.

63. Bayes-Genis A, Conover CA, Overgaard MT, et al. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A as a marker of acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(14):1022-1029.

64. Lund J, Qin QP, Ilva T, et al. Circulating pregnancy-associated plasma protein A predicts outcome in patients with acute coronary syndrome but no troponin I elevation. Circulation. 2003; 108(16):1924-1926.

Since the 1950s, researchers and clinicians have sought a simple chemical biomarker that would aid in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD). An initial discovery was that proteins normally found within cardiac myocytes are released into the circulation when the myocardial cell membrane loses its integrity as a result of hypoxic injury.1 Over the past 60 years, major advances have been made to distinguish which proteins are highly cardiac specific, and which are suggestive of other pathologic cardiovascular processes.

In the past 15 to 20 years, significant data have emerged that support the role of cardiac-specific troponins in the cardiac disease process, making their measurement an important consideration in diagnosis and clinical decision-making for patients with various forms of CVD.2-7 With the exception of 1918, CVD has accounted for more deaths in the United States than any other illness in every year since 1900.8 It has been suggested that nearly 2,300 Americans die of CVD each day—an average of one death every 38 seconds. The direct and indirect costs of CVD for 2010 were projected at $503.2 billion—including $155 billion for total hospital costs alone.9 By comparison, a 2010 projection from the National Cancer Institute was $124.57 billion for the direct costs of cancer care.10

It is imperative for practitioners in all areas of medicine to have a working knowledge of the role of cardiac biomarkers and their potential impact on patients’ overall health. Primary care clinicians in particular should be familiar with the release kinetics of certain cardiac biomarkers to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of the cardiac patient. This article is intended as an overview of the cardiac biomarkers that are being used in practice today, and to review the novel biomarkers that may have an impact on the way clinicians practice in the near future.

BIOMARKERS CURRENTLY IN USE

Cardiac Troponins

The cardiac-specific troponins (cTn) are an integral component of the myosin-actin binding complex found in striated muscle tissue. The troponin complex includes three regulatory proteins: troponin C, troponin I, and troponin T. The genes that code for troponin C are identical in skeletal and cardiac tissue; for this reason, troponin C becomes much less cardiospecific.

However, cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) have differing amino acid sequences, making it possible to develop highly sensitive immunoassays to detect circulating antibody-troponin complexes after myocardial cell injury, as seen in acute coronary syndrome (ACS).12-14 No cross-reactivity occurs between skeletal and cardiac sources, indicating the unique cardiospecificity of the cTn proteins.11