User login

Fibroids: Growing management options for a prevalent problem

OBG Manag. 33(12). | doi 10.12788/obgm.0169

2022 Update on obstetrics

Obstetrical practice saw updates in 2021 to 3 major areas of pregnancy management: preterm birth prevention, antepartum fetal surveillance, and the use of antenatal corticosteroids.

Updated guidance on predicting and preventing spontaneous PTB

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65-e90.

Preterm birth (PTB) continues to pose a challenge in clinical obstetrics, with the most recently reported rate of 10.2% in the United States.1 This accounts for almost 75% of perinatal mortality and more than half of neonatal morbidity, in which effects last well past the neonatal period. PTB is classified as spontaneous (following preterm labor, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, or cervical insufficiency) or iatrogenic (indicated due to maternal and/or fetal complications).

Assessing risk for PTB

The single strongest predictor of subsequent PTB is a history of spontaneous PTB. Recurrence risk is further increased by the number of prior PTBs and the gestational age at prior PTB. Identification of and intervention for a short cervix has been shown to prolong gestation. Transvaginal ultrasonography of the cervix is the most accurate method for evaluating cervical length (CL). Specific examination criteria exist to ensure that CL measurements are reproducible and reliable.2 A short CL is generally defined as a measurement of less than 25 mm between 16 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

Screening strategies

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), with an endorsement from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), recommends cervical evaluation during the anatomy ultrasound exam between 18 0/7 and 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation in all pregnant patients regardless of prior PTB.3 If transabdominal imaging is concerning for a shortened cervix, transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed to assess the CL.

Serial transvaginal CL measurements are recommended between 16 0/7 and 24 0/7 weeks’ gestation for patients with a current singleton pregnancy and history of a spontaneous PTB, but not for patients with a history of iatrogenic or indicated PTB.

Interventions: Mind your p’s and c’s

Interventions to reduce the risk of spontaneous PTB depend on whether the current pregnancy is a singleton, twins, or higher-order multiples; CL measurement; and history of spontaneous PTB. Preconception optimization of underlying medical conditions also is important to reduce the risk of recurrent indicated PTB.

Continue to: Progesterone...

Progesterone

Vaginal administration. Several trials have shown that vaginal progesterone can be used to reduce the risk of spontaneous PTB in asymptomatic patients with a singleton pregnancy, incidental finding of a short cervix (<25 mm), and no history of spontaneous PTB. This is a change from the prior recommendation of CL of less than 20 mm. In the setting of a twin pregnancy, regardless of CL, data do not definitively support the use of vaginal progesterone.

Intramuscular administration.4,5 The popularity of intramuscular progesterone has waxed and waned. At present, ACOG recommends that all patients with a singleton pregnancy and history of spontaneous PTB be offered progesterone beginning at 16 0/7 weeks’ gestation following a shared decision-making process that includes the limited data of efficacy noted in existing studies.

In a twin pregnancy with no history of spontaneous PTB, the use of intramuscular progesterone has been shown to potentially increase the risk of PTB and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. As such, intramuscular progesterone in the setting of a twin gestation without a history of spontaneous PTB is not recommended. When a prior spontaneous PTB has occurred, there may be some benefit to intramuscular progesterone in twin gestations.

Cerclage

Ultrasound indicated. In a singleton pregnancy with an incidental finding of short cervix (<25 mm) and no history of PTB, the use of cerclage is of uncertain benefit. Effectiveness may be seen if the cervix is less than 10 mm. Ultrasound-indicated cerclage should be considered in a singleton pregnancy with a CL less than 25 mm and a history of spontaneous PTB.

Possibly one of the most controversial topics is ultrasound-indicated cerclage placement in twin gestation. As with many situations in obstetrics, data regarding ultrasound-indicated cerclage in twin gestation is based on small retrospective studies fraught with bias. Results from these studies range from no benefit, to potential benefit, to even possible increased risk of PTB. Since data are limited, as we await more evidence, it is recommended that the clinician and patient use shared decision making to decide on cerclage placement in a twin gestation.

Exam indicated. In a singleton pregnancy with a dilated cervix on digital or speculum exam between 16 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks’ gestation, a physical exam–indicated cerclage should be offered. Exam-indicated cerclage also may reduce the incidence of PTB in twin gestations with cervical dilation between 16 0/7 and 23 6/7 weeks’ gestation. Indomethacin tocolysis and perioperative antibiotics should be considered when an exam-indicated cerclage is placed.

As the limits of viability are continually pushed earlier, more in-depth conversation is needed with patients who are considering an exam-indicated cerclage. The nuances of periviability and the likelihood that an exam-indicated cerclage will commit a pregnancy to a periviable or extremely preterm birth should be discussed in detail using a shared decision making model.

Regardless of whether the cerclage is ultrasound or exam indicated, once it is placed there is no utility in additional CL ultrasound monitoring.

Pessary

Vaginal pessaries for prevention of PTB have not gained popularity in the United States as they have in other countries. Trials are being conducted to determine the utility of vaginal pessary, but current data have not proven its effectiveness in preventing PTB in the setting of singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and no history of spontaneous PTB. So for now, pessary is not recommended. The same can be said for use in the twin gestation.

- All patients should have cervical evaluation during pregnancy. Serial imaging is reserved for those with a history of spontaneous PTB.

- Progesterone supplementation should be offered to patients with a singleton pregnancy and a history of spontaneous PTB or to patients with a singleton pregnancy and no history of spontaneous PTB who have cervical shortening at less than 24 weeks.

- Cerclage may be offered between 16 and 24 weeks for a cervical length less than 25 mm in a patient with a singleton gestation who has a history of spontaneous PTB (<10 mm if no history of spontaneous PTB) or for a dilated cervix on exam regardless of history.

- Women who have a twin gestation with cervical dilation may be offered physical exam–indicated cerclage.

Which patients may benefit from antepartum fetal surveillance and when to initiate it

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetrics Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal surveillance: ACOG committee opinion, number 828. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Antepartum fetal surveillance: ACOG practice bulletin, number 229. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e116-e127.

The ultimate purpose of antenatal fetal surveillance is to prevent stillbirth. However, stillbirth has multiple etiologies, not all of which are preventable with testing. In June 2021, ACOG released a new Committee Opinion containing guidelines for fetal surveillance, including suggested gestational age at initiation and frequency of testing, for the most common high-risk conditions. ACOG also released an update to the Practice Bulletin on antepartum fetal surveillance; additions include randomized controlled trial level data on the utility of fetal kick counts (FKCs) and recommendations that align with the new Committee Opinion.

Data for the efficacy of antepartum fetal surveillance are lacking, mainly due to the difficulty of performing prospective studies in stillbirth. The existing evidence is subject to intervention bias, as deliveries increase in tested patients, and recommendations rely heavily on expert consensus and nonrandomized studies. Antenatal testing is also time, cost, and labor intensive, with the risk of intervention for a false-positive result. Despite these limitations, obstetrical practices routinely perform antenatal fetal surveillance.

The new guidelines: The why, when, and how often

Why. Antepartum fetal surveillance is suggested for conditions that have a risk of stillbirth greater than 0.8 per 1,000 (that is, the false-negative rate of a biophysical profile or a modified biophysical profile) and the relative risk or odds ratio is greater than 2.0 for stillbirth compared with unaffected pregnancies.

When. For most conditions, ACOG recommends initiation of testing at 32 weeks or later, with notable earlier exceptions for some of the highest-risk patients. For certain conditions, such as fetal growth restriction and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, the recommendation is to start “at diagnosis,” with the corollary “or at a gestational age when delivery would be considered because of abnormal results.” Shared decision making with the patient about pregnancy goals therefore is required, particularly in cases of fetal anomalies, genetic conditions, or at very early gestational ages.

How often. The recommended frequency of testing is at least weekly. Testing frequency should be increased to twice-weekly outpatient or daily inpatient for the most complicated pregnancies (for example, fetal growth restriction with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies, preeclampsia with severe features).

Once or twice weekly is an option for many conditions, which gives the clinician the opportunity to assess clinical stability as well as the patient’s input in terms of logistics and anxiety.

Patients with multiple conditions may fall into the “individualized” category, as do patients with suboptimal control of conditions (for example, diabetes, hypertension) that may affect the fetus as the pregnancy progresses.

New diagnoses included for surveillance

Several diagnoses not previously included now qualify for antepartum fetal surveillance under the new guidelines, most notably:

- history of obstetrical complications in the immediate preceding pregnancy

—history of prior fetal growth restriction requiring preterm delivery

—history of prior preeclampsia requiring delivery

- alcohol use of 5 or more drinks per day

- in vitro fertilization

- abnormal serum markers

—pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) in the fifth or lower percentile or 0.4 multiples of the median (MoM)

—second trimester inhibin A of 2 or greater MoM

- prepregnancy body mass index (BMI)

—this is divided into 2 categories for timing of initiation of testing:

- 37 weeks for BMI of 35 to 39.9 kg/m2

- 34 weeks for BMI of or greater than 40 kg/m2.

Fetal kick counts

The major change to the updated Practice Bulletin on antenatal surveillance is the inclusion of data on FKCs, a simple modality of fetal surveillance that does not require a clinical visit. For FKCs, a meta-analysis of more than 450,000 patients did not demonstrate a difference in perinatal death between the FKC intervention group (0.54%) and the control group (0.59%). Of note, there were small but statistically significant increases in the rates of induction of labor, cesarean delivery, and preterm delivery in the FKC intervention group. Therefore, this update does not recommend a formal program of FKCs for all patients.

- The antenatal fetal surveillance guidelines are just that—guidelines, not mandates. Their use will need to be adapted for specific patient populations and practice management patterns.

- Many conditions qualify for “individualized” surveillance, which offers the opportunity for detailed discussions on the patient’s care. This includes shared decision making with patients to meet their goals for the pregnancy.

- Although patient-perceived decreased fetal movement always warrants clinical evaluation, a regular program of fetal kick count monitoring is not recommended for all patients due to lack of data supporting its benefit in reducing perinatal death.

- As with any change, new guidelines potentially are a source of frustration, so a concerted effort by obstetrical clinicians to agree on adoption of the guidelines is needed. Additional clinical resources and both clinician and patient education may be required depending on current practice style, as the new strategy may increase the number of appointments and ultrasound exams required.

Continue to: Use of antenatal corticosteroids now may be considered at 22 weeks’ gestation...

Use of antenatal corticosteroids now may be considered at 22 weeks’ gestation

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Use of antenatal corticosteroids at 22 weeks of gestation: ACOG practice advisory. September 2021. https://www .acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory /articles/2021/09/use-of-antenatal-corticosteroids-at -22-weeks-of-gestation. Accessed December 11, 2021.

In September 2021, ACOG and SMFM released a Practice Advisory updating the current recommendations for the administration of antenatal corticosteroids in the periviable period (22 to 25 6/7 weeks’ gestation). Whereas the prior lower limit of gestational age for consideration of steroids was 23 weeks, the new recommendation now extends this consideration down to 22 weeks.

The cited data include a meta-analysis of more than 2,200 patients in which the survival rate of infants born between 22 and 22 6/7 weeks who were exposed to antenatal steroids was 39% compared with 19.5% in the unexposed group. Another study of more than 1,000 patients demonstrated a statistically significant increase in overall survival in patients treated with antenatal steroids plus life support compared with life support only (38.5% vs 17.7%). Survival without major morbidity in this study, although increased from 1% to 4.4%, was still low.

Recommendation carries caveats

Given this information, the Practice Advisory offers a 2C level recommendation (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence) for antenatal steroids at 22 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation if neonatal resuscitation is planned, acknowledging the limitations and potential bias of the available data.

The Practice Advisory emphasizes the importance of counseling and patient involvement in the decision making. This requires a multidisciplinary collaboration among the neonatology and obstetrical teams, flexibility in the plan after birth depending on the infant’s condition, and redirection of care if appropriate. Estimated fetal weight, the presence of multiple gestations, fetal biologic sex, and any anomalies are also important in helping families make an informed decision for their particular pregnancy. As described in the Obstetric Care Consensus on periviable birth,6 it is important to remember that considerations and recommendations are not the same as requirements, and redirection of care to comfort and family memory making is not the same as withholding care.

The rest of the recommendations for the administration of antenatal steroids remain the same: Antenatal steroids are not recommended at less than 22 weeks due to lack of evidence of benefit, and they continue to be recommended at 24 weeks and beyond. ●

- Antenatal corticosteroids may be considered at 22 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation if, after thorough patient counseling, neonatal resuscitation is desired and planned by the family.

- The overall likelihood of survival and survival without major morbidities continues to be very low in the periviable period, especially at 22 weeks. Gestational age is only one of the many factors that must be considered in the shared decision making for this very difficult decision.

- Palliative care is a valid and appropriate option for patients facing a periviable delivery after appropriate counseling or after evaluation of the infant has occurred after birth.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 387. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. October 2020. www.cdc.gov/nchs /data/databriefs/db387-H.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- To MS, Skentou C, Chan C, et al. Cervical assessment at the routine 23-week scan: standardizing techniques. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:217-219.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65-e90.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement: use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:B16-B18.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:127-136.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus no. 6: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e187-e199.

Obstetrical practice saw updates in 2021 to 3 major areas of pregnancy management: preterm birth prevention, antepartum fetal surveillance, and the use of antenatal corticosteroids.

Updated guidance on predicting and preventing spontaneous PTB

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65-e90.

Preterm birth (PTB) continues to pose a challenge in clinical obstetrics, with the most recently reported rate of 10.2% in the United States.1 This accounts for almost 75% of perinatal mortality and more than half of neonatal morbidity, in which effects last well past the neonatal period. PTB is classified as spontaneous (following preterm labor, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, or cervical insufficiency) or iatrogenic (indicated due to maternal and/or fetal complications).

Assessing risk for PTB

The single strongest predictor of subsequent PTB is a history of spontaneous PTB. Recurrence risk is further increased by the number of prior PTBs and the gestational age at prior PTB. Identification of and intervention for a short cervix has been shown to prolong gestation. Transvaginal ultrasonography of the cervix is the most accurate method for evaluating cervical length (CL). Specific examination criteria exist to ensure that CL measurements are reproducible and reliable.2 A short CL is generally defined as a measurement of less than 25 mm between 16 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

Screening strategies

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), with an endorsement from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), recommends cervical evaluation during the anatomy ultrasound exam between 18 0/7 and 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation in all pregnant patients regardless of prior PTB.3 If transabdominal imaging is concerning for a shortened cervix, transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed to assess the CL.

Serial transvaginal CL measurements are recommended between 16 0/7 and 24 0/7 weeks’ gestation for patients with a current singleton pregnancy and history of a spontaneous PTB, but not for patients with a history of iatrogenic or indicated PTB.

Interventions: Mind your p’s and c’s

Interventions to reduce the risk of spontaneous PTB depend on whether the current pregnancy is a singleton, twins, or higher-order multiples; CL measurement; and history of spontaneous PTB. Preconception optimization of underlying medical conditions also is important to reduce the risk of recurrent indicated PTB.

Continue to: Progesterone...

Progesterone

Vaginal administration. Several trials have shown that vaginal progesterone can be used to reduce the risk of spontaneous PTB in asymptomatic patients with a singleton pregnancy, incidental finding of a short cervix (<25 mm), and no history of spontaneous PTB. This is a change from the prior recommendation of CL of less than 20 mm. In the setting of a twin pregnancy, regardless of CL, data do not definitively support the use of vaginal progesterone.

Intramuscular administration.4,5 The popularity of intramuscular progesterone has waxed and waned. At present, ACOG recommends that all patients with a singleton pregnancy and history of spontaneous PTB be offered progesterone beginning at 16 0/7 weeks’ gestation following a shared decision-making process that includes the limited data of efficacy noted in existing studies.

In a twin pregnancy with no history of spontaneous PTB, the use of intramuscular progesterone has been shown to potentially increase the risk of PTB and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. As such, intramuscular progesterone in the setting of a twin gestation without a history of spontaneous PTB is not recommended. When a prior spontaneous PTB has occurred, there may be some benefit to intramuscular progesterone in twin gestations.

Cerclage

Ultrasound indicated. In a singleton pregnancy with an incidental finding of short cervix (<25 mm) and no history of PTB, the use of cerclage is of uncertain benefit. Effectiveness may be seen if the cervix is less than 10 mm. Ultrasound-indicated cerclage should be considered in a singleton pregnancy with a CL less than 25 mm and a history of spontaneous PTB.

Possibly one of the most controversial topics is ultrasound-indicated cerclage placement in twin gestation. As with many situations in obstetrics, data regarding ultrasound-indicated cerclage in twin gestation is based on small retrospective studies fraught with bias. Results from these studies range from no benefit, to potential benefit, to even possible increased risk of PTB. Since data are limited, as we await more evidence, it is recommended that the clinician and patient use shared decision making to decide on cerclage placement in a twin gestation.

Exam indicated. In a singleton pregnancy with a dilated cervix on digital or speculum exam between 16 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks’ gestation, a physical exam–indicated cerclage should be offered. Exam-indicated cerclage also may reduce the incidence of PTB in twin gestations with cervical dilation between 16 0/7 and 23 6/7 weeks’ gestation. Indomethacin tocolysis and perioperative antibiotics should be considered when an exam-indicated cerclage is placed.

As the limits of viability are continually pushed earlier, more in-depth conversation is needed with patients who are considering an exam-indicated cerclage. The nuances of periviability and the likelihood that an exam-indicated cerclage will commit a pregnancy to a periviable or extremely preterm birth should be discussed in detail using a shared decision making model.

Regardless of whether the cerclage is ultrasound or exam indicated, once it is placed there is no utility in additional CL ultrasound monitoring.

Pessary

Vaginal pessaries for prevention of PTB have not gained popularity in the United States as they have in other countries. Trials are being conducted to determine the utility of vaginal pessary, but current data have not proven its effectiveness in preventing PTB in the setting of singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and no history of spontaneous PTB. So for now, pessary is not recommended. The same can be said for use in the twin gestation.

- All patients should have cervical evaluation during pregnancy. Serial imaging is reserved for those with a history of spontaneous PTB.

- Progesterone supplementation should be offered to patients with a singleton pregnancy and a history of spontaneous PTB or to patients with a singleton pregnancy and no history of spontaneous PTB who have cervical shortening at less than 24 weeks.

- Cerclage may be offered between 16 and 24 weeks for a cervical length less than 25 mm in a patient with a singleton gestation who has a history of spontaneous PTB (<10 mm if no history of spontaneous PTB) or for a dilated cervix on exam regardless of history.

- Women who have a twin gestation with cervical dilation may be offered physical exam–indicated cerclage.

Which patients may benefit from antepartum fetal surveillance and when to initiate it

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetrics Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal surveillance: ACOG committee opinion, number 828. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Antepartum fetal surveillance: ACOG practice bulletin, number 229. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e116-e127.

The ultimate purpose of antenatal fetal surveillance is to prevent stillbirth. However, stillbirth has multiple etiologies, not all of which are preventable with testing. In June 2021, ACOG released a new Committee Opinion containing guidelines for fetal surveillance, including suggested gestational age at initiation and frequency of testing, for the most common high-risk conditions. ACOG also released an update to the Practice Bulletin on antepartum fetal surveillance; additions include randomized controlled trial level data on the utility of fetal kick counts (FKCs) and recommendations that align with the new Committee Opinion.

Data for the efficacy of antepartum fetal surveillance are lacking, mainly due to the difficulty of performing prospective studies in stillbirth. The existing evidence is subject to intervention bias, as deliveries increase in tested patients, and recommendations rely heavily on expert consensus and nonrandomized studies. Antenatal testing is also time, cost, and labor intensive, with the risk of intervention for a false-positive result. Despite these limitations, obstetrical practices routinely perform antenatal fetal surveillance.

The new guidelines: The why, when, and how often

Why. Antepartum fetal surveillance is suggested for conditions that have a risk of stillbirth greater than 0.8 per 1,000 (that is, the false-negative rate of a biophysical profile or a modified biophysical profile) and the relative risk or odds ratio is greater than 2.0 for stillbirth compared with unaffected pregnancies.

When. For most conditions, ACOG recommends initiation of testing at 32 weeks or later, with notable earlier exceptions for some of the highest-risk patients. For certain conditions, such as fetal growth restriction and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, the recommendation is to start “at diagnosis,” with the corollary “or at a gestational age when delivery would be considered because of abnormal results.” Shared decision making with the patient about pregnancy goals therefore is required, particularly in cases of fetal anomalies, genetic conditions, or at very early gestational ages.

How often. The recommended frequency of testing is at least weekly. Testing frequency should be increased to twice-weekly outpatient or daily inpatient for the most complicated pregnancies (for example, fetal growth restriction with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies, preeclampsia with severe features).

Once or twice weekly is an option for many conditions, which gives the clinician the opportunity to assess clinical stability as well as the patient’s input in terms of logistics and anxiety.

Patients with multiple conditions may fall into the “individualized” category, as do patients with suboptimal control of conditions (for example, diabetes, hypertension) that may affect the fetus as the pregnancy progresses.

New diagnoses included for surveillance

Several diagnoses not previously included now qualify for antepartum fetal surveillance under the new guidelines, most notably:

- history of obstetrical complications in the immediate preceding pregnancy

—history of prior fetal growth restriction requiring preterm delivery

—history of prior preeclampsia requiring delivery

- alcohol use of 5 or more drinks per day

- in vitro fertilization

- abnormal serum markers

—pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) in the fifth or lower percentile or 0.4 multiples of the median (MoM)

—second trimester inhibin A of 2 or greater MoM

- prepregnancy body mass index (BMI)

—this is divided into 2 categories for timing of initiation of testing:

- 37 weeks for BMI of 35 to 39.9 kg/m2

- 34 weeks for BMI of or greater than 40 kg/m2.

Fetal kick counts

The major change to the updated Practice Bulletin on antenatal surveillance is the inclusion of data on FKCs, a simple modality of fetal surveillance that does not require a clinical visit. For FKCs, a meta-analysis of more than 450,000 patients did not demonstrate a difference in perinatal death between the FKC intervention group (0.54%) and the control group (0.59%). Of note, there were small but statistically significant increases in the rates of induction of labor, cesarean delivery, and preterm delivery in the FKC intervention group. Therefore, this update does not recommend a formal program of FKCs for all patients.

- The antenatal fetal surveillance guidelines are just that—guidelines, not mandates. Their use will need to be adapted for specific patient populations and practice management patterns.

- Many conditions qualify for “individualized” surveillance, which offers the opportunity for detailed discussions on the patient’s care. This includes shared decision making with patients to meet their goals for the pregnancy.

- Although patient-perceived decreased fetal movement always warrants clinical evaluation, a regular program of fetal kick count monitoring is not recommended for all patients due to lack of data supporting its benefit in reducing perinatal death.

- As with any change, new guidelines potentially are a source of frustration, so a concerted effort by obstetrical clinicians to agree on adoption of the guidelines is needed. Additional clinical resources and both clinician and patient education may be required depending on current practice style, as the new strategy may increase the number of appointments and ultrasound exams required.

Continue to: Use of antenatal corticosteroids now may be considered at 22 weeks’ gestation...

Use of antenatal corticosteroids now may be considered at 22 weeks’ gestation

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Use of antenatal corticosteroids at 22 weeks of gestation: ACOG practice advisory. September 2021. https://www .acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory /articles/2021/09/use-of-antenatal-corticosteroids-at -22-weeks-of-gestation. Accessed December 11, 2021.

In September 2021, ACOG and SMFM released a Practice Advisory updating the current recommendations for the administration of antenatal corticosteroids in the periviable period (22 to 25 6/7 weeks’ gestation). Whereas the prior lower limit of gestational age for consideration of steroids was 23 weeks, the new recommendation now extends this consideration down to 22 weeks.

The cited data include a meta-analysis of more than 2,200 patients in which the survival rate of infants born between 22 and 22 6/7 weeks who were exposed to antenatal steroids was 39% compared with 19.5% in the unexposed group. Another study of more than 1,000 patients demonstrated a statistically significant increase in overall survival in patients treated with antenatal steroids plus life support compared with life support only (38.5% vs 17.7%). Survival without major morbidity in this study, although increased from 1% to 4.4%, was still low.

Recommendation carries caveats

Given this information, the Practice Advisory offers a 2C level recommendation (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence) for antenatal steroids at 22 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation if neonatal resuscitation is planned, acknowledging the limitations and potential bias of the available data.

The Practice Advisory emphasizes the importance of counseling and patient involvement in the decision making. This requires a multidisciplinary collaboration among the neonatology and obstetrical teams, flexibility in the plan after birth depending on the infant’s condition, and redirection of care if appropriate. Estimated fetal weight, the presence of multiple gestations, fetal biologic sex, and any anomalies are also important in helping families make an informed decision for their particular pregnancy. As described in the Obstetric Care Consensus on periviable birth,6 it is important to remember that considerations and recommendations are not the same as requirements, and redirection of care to comfort and family memory making is not the same as withholding care.

The rest of the recommendations for the administration of antenatal steroids remain the same: Antenatal steroids are not recommended at less than 22 weeks due to lack of evidence of benefit, and they continue to be recommended at 24 weeks and beyond. ●

- Antenatal corticosteroids may be considered at 22 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation if, after thorough patient counseling, neonatal resuscitation is desired and planned by the family.

- The overall likelihood of survival and survival without major morbidities continues to be very low in the periviable period, especially at 22 weeks. Gestational age is only one of the many factors that must be considered in the shared decision making for this very difficult decision.

- Palliative care is a valid and appropriate option for patients facing a periviable delivery after appropriate counseling or after evaluation of the infant has occurred after birth.

Obstetrical practice saw updates in 2021 to 3 major areas of pregnancy management: preterm birth prevention, antepartum fetal surveillance, and the use of antenatal corticosteroids.

Updated guidance on predicting and preventing spontaneous PTB

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65-e90.

Preterm birth (PTB) continues to pose a challenge in clinical obstetrics, with the most recently reported rate of 10.2% in the United States.1 This accounts for almost 75% of perinatal mortality and more than half of neonatal morbidity, in which effects last well past the neonatal period. PTB is classified as spontaneous (following preterm labor, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, or cervical insufficiency) or iatrogenic (indicated due to maternal and/or fetal complications).

Assessing risk for PTB

The single strongest predictor of subsequent PTB is a history of spontaneous PTB. Recurrence risk is further increased by the number of prior PTBs and the gestational age at prior PTB. Identification of and intervention for a short cervix has been shown to prolong gestation. Transvaginal ultrasonography of the cervix is the most accurate method for evaluating cervical length (CL). Specific examination criteria exist to ensure that CL measurements are reproducible and reliable.2 A short CL is generally defined as a measurement of less than 25 mm between 16 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

Screening strategies

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), with an endorsement from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), recommends cervical evaluation during the anatomy ultrasound exam between 18 0/7 and 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation in all pregnant patients regardless of prior PTB.3 If transabdominal imaging is concerning for a shortened cervix, transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed to assess the CL.

Serial transvaginal CL measurements are recommended between 16 0/7 and 24 0/7 weeks’ gestation for patients with a current singleton pregnancy and history of a spontaneous PTB, but not for patients with a history of iatrogenic or indicated PTB.

Interventions: Mind your p’s and c’s

Interventions to reduce the risk of spontaneous PTB depend on whether the current pregnancy is a singleton, twins, or higher-order multiples; CL measurement; and history of spontaneous PTB. Preconception optimization of underlying medical conditions also is important to reduce the risk of recurrent indicated PTB.

Continue to: Progesterone...

Progesterone

Vaginal administration. Several trials have shown that vaginal progesterone can be used to reduce the risk of spontaneous PTB in asymptomatic patients with a singleton pregnancy, incidental finding of a short cervix (<25 mm), and no history of spontaneous PTB. This is a change from the prior recommendation of CL of less than 20 mm. In the setting of a twin pregnancy, regardless of CL, data do not definitively support the use of vaginal progesterone.

Intramuscular administration.4,5 The popularity of intramuscular progesterone has waxed and waned. At present, ACOG recommends that all patients with a singleton pregnancy and history of spontaneous PTB be offered progesterone beginning at 16 0/7 weeks’ gestation following a shared decision-making process that includes the limited data of efficacy noted in existing studies.

In a twin pregnancy with no history of spontaneous PTB, the use of intramuscular progesterone has been shown to potentially increase the risk of PTB and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. As such, intramuscular progesterone in the setting of a twin gestation without a history of spontaneous PTB is not recommended. When a prior spontaneous PTB has occurred, there may be some benefit to intramuscular progesterone in twin gestations.

Cerclage

Ultrasound indicated. In a singleton pregnancy with an incidental finding of short cervix (<25 mm) and no history of PTB, the use of cerclage is of uncertain benefit. Effectiveness may be seen if the cervix is less than 10 mm. Ultrasound-indicated cerclage should be considered in a singleton pregnancy with a CL less than 25 mm and a history of spontaneous PTB.

Possibly one of the most controversial topics is ultrasound-indicated cerclage placement in twin gestation. As with many situations in obstetrics, data regarding ultrasound-indicated cerclage in twin gestation is based on small retrospective studies fraught with bias. Results from these studies range from no benefit, to potential benefit, to even possible increased risk of PTB. Since data are limited, as we await more evidence, it is recommended that the clinician and patient use shared decision making to decide on cerclage placement in a twin gestation.

Exam indicated. In a singleton pregnancy with a dilated cervix on digital or speculum exam between 16 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks’ gestation, a physical exam–indicated cerclage should be offered. Exam-indicated cerclage also may reduce the incidence of PTB in twin gestations with cervical dilation between 16 0/7 and 23 6/7 weeks’ gestation. Indomethacin tocolysis and perioperative antibiotics should be considered when an exam-indicated cerclage is placed.

As the limits of viability are continually pushed earlier, more in-depth conversation is needed with patients who are considering an exam-indicated cerclage. The nuances of periviability and the likelihood that an exam-indicated cerclage will commit a pregnancy to a periviable or extremely preterm birth should be discussed in detail using a shared decision making model.

Regardless of whether the cerclage is ultrasound or exam indicated, once it is placed there is no utility in additional CL ultrasound monitoring.

Pessary

Vaginal pessaries for prevention of PTB have not gained popularity in the United States as they have in other countries. Trials are being conducted to determine the utility of vaginal pessary, but current data have not proven its effectiveness in preventing PTB in the setting of singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and no history of spontaneous PTB. So for now, pessary is not recommended. The same can be said for use in the twin gestation.

- All patients should have cervical evaluation during pregnancy. Serial imaging is reserved for those with a history of spontaneous PTB.

- Progesterone supplementation should be offered to patients with a singleton pregnancy and a history of spontaneous PTB or to patients with a singleton pregnancy and no history of spontaneous PTB who have cervical shortening at less than 24 weeks.

- Cerclage may be offered between 16 and 24 weeks for a cervical length less than 25 mm in a patient with a singleton gestation who has a history of spontaneous PTB (<10 mm if no history of spontaneous PTB) or for a dilated cervix on exam regardless of history.

- Women who have a twin gestation with cervical dilation may be offered physical exam–indicated cerclage.

Which patients may benefit from antepartum fetal surveillance and when to initiate it

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetrics Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal surveillance: ACOG committee opinion, number 828. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Antepartum fetal surveillance: ACOG practice bulletin, number 229. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e116-e127.

The ultimate purpose of antenatal fetal surveillance is to prevent stillbirth. However, stillbirth has multiple etiologies, not all of which are preventable with testing. In June 2021, ACOG released a new Committee Opinion containing guidelines for fetal surveillance, including suggested gestational age at initiation and frequency of testing, for the most common high-risk conditions. ACOG also released an update to the Practice Bulletin on antepartum fetal surveillance; additions include randomized controlled trial level data on the utility of fetal kick counts (FKCs) and recommendations that align with the new Committee Opinion.

Data for the efficacy of antepartum fetal surveillance are lacking, mainly due to the difficulty of performing prospective studies in stillbirth. The existing evidence is subject to intervention bias, as deliveries increase in tested patients, and recommendations rely heavily on expert consensus and nonrandomized studies. Antenatal testing is also time, cost, and labor intensive, with the risk of intervention for a false-positive result. Despite these limitations, obstetrical practices routinely perform antenatal fetal surveillance.

The new guidelines: The why, when, and how often

Why. Antepartum fetal surveillance is suggested for conditions that have a risk of stillbirth greater than 0.8 per 1,000 (that is, the false-negative rate of a biophysical profile or a modified biophysical profile) and the relative risk or odds ratio is greater than 2.0 for stillbirth compared with unaffected pregnancies.

When. For most conditions, ACOG recommends initiation of testing at 32 weeks or later, with notable earlier exceptions for some of the highest-risk patients. For certain conditions, such as fetal growth restriction and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, the recommendation is to start “at diagnosis,” with the corollary “or at a gestational age when delivery would be considered because of abnormal results.” Shared decision making with the patient about pregnancy goals therefore is required, particularly in cases of fetal anomalies, genetic conditions, or at very early gestational ages.

How often. The recommended frequency of testing is at least weekly. Testing frequency should be increased to twice-weekly outpatient or daily inpatient for the most complicated pregnancies (for example, fetal growth restriction with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies, preeclampsia with severe features).

Once or twice weekly is an option for many conditions, which gives the clinician the opportunity to assess clinical stability as well as the patient’s input in terms of logistics and anxiety.

Patients with multiple conditions may fall into the “individualized” category, as do patients with suboptimal control of conditions (for example, diabetes, hypertension) that may affect the fetus as the pregnancy progresses.

New diagnoses included for surveillance

Several diagnoses not previously included now qualify for antepartum fetal surveillance under the new guidelines, most notably:

- history of obstetrical complications in the immediate preceding pregnancy

—history of prior fetal growth restriction requiring preterm delivery

—history of prior preeclampsia requiring delivery

- alcohol use of 5 or more drinks per day

- in vitro fertilization

- abnormal serum markers

—pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) in the fifth or lower percentile or 0.4 multiples of the median (MoM)

—second trimester inhibin A of 2 or greater MoM

- prepregnancy body mass index (BMI)

—this is divided into 2 categories for timing of initiation of testing:

- 37 weeks for BMI of 35 to 39.9 kg/m2

- 34 weeks for BMI of or greater than 40 kg/m2.

Fetal kick counts

The major change to the updated Practice Bulletin on antenatal surveillance is the inclusion of data on FKCs, a simple modality of fetal surveillance that does not require a clinical visit. For FKCs, a meta-analysis of more than 450,000 patients did not demonstrate a difference in perinatal death between the FKC intervention group (0.54%) and the control group (0.59%). Of note, there were small but statistically significant increases in the rates of induction of labor, cesarean delivery, and preterm delivery in the FKC intervention group. Therefore, this update does not recommend a formal program of FKCs for all patients.

- The antenatal fetal surveillance guidelines are just that—guidelines, not mandates. Their use will need to be adapted for specific patient populations and practice management patterns.

- Many conditions qualify for “individualized” surveillance, which offers the opportunity for detailed discussions on the patient’s care. This includes shared decision making with patients to meet their goals for the pregnancy.

- Although patient-perceived decreased fetal movement always warrants clinical evaluation, a regular program of fetal kick count monitoring is not recommended for all patients due to lack of data supporting its benefit in reducing perinatal death.

- As with any change, new guidelines potentially are a source of frustration, so a concerted effort by obstetrical clinicians to agree on adoption of the guidelines is needed. Additional clinical resources and both clinician and patient education may be required depending on current practice style, as the new strategy may increase the number of appointments and ultrasound exams required.

Continue to: Use of antenatal corticosteroids now may be considered at 22 weeks’ gestation...

Use of antenatal corticosteroids now may be considered at 22 weeks’ gestation

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Use of antenatal corticosteroids at 22 weeks of gestation: ACOG practice advisory. September 2021. https://www .acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory /articles/2021/09/use-of-antenatal-corticosteroids-at -22-weeks-of-gestation. Accessed December 11, 2021.

In September 2021, ACOG and SMFM released a Practice Advisory updating the current recommendations for the administration of antenatal corticosteroids in the periviable period (22 to 25 6/7 weeks’ gestation). Whereas the prior lower limit of gestational age for consideration of steroids was 23 weeks, the new recommendation now extends this consideration down to 22 weeks.

The cited data include a meta-analysis of more than 2,200 patients in which the survival rate of infants born between 22 and 22 6/7 weeks who were exposed to antenatal steroids was 39% compared with 19.5% in the unexposed group. Another study of more than 1,000 patients demonstrated a statistically significant increase in overall survival in patients treated with antenatal steroids plus life support compared with life support only (38.5% vs 17.7%). Survival without major morbidity in this study, although increased from 1% to 4.4%, was still low.

Recommendation carries caveats

Given this information, the Practice Advisory offers a 2C level recommendation (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence) for antenatal steroids at 22 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation if neonatal resuscitation is planned, acknowledging the limitations and potential bias of the available data.

The Practice Advisory emphasizes the importance of counseling and patient involvement in the decision making. This requires a multidisciplinary collaboration among the neonatology and obstetrical teams, flexibility in the plan after birth depending on the infant’s condition, and redirection of care if appropriate. Estimated fetal weight, the presence of multiple gestations, fetal biologic sex, and any anomalies are also important in helping families make an informed decision for their particular pregnancy. As described in the Obstetric Care Consensus on periviable birth,6 it is important to remember that considerations and recommendations are not the same as requirements, and redirection of care to comfort and family memory making is not the same as withholding care.

The rest of the recommendations for the administration of antenatal steroids remain the same: Antenatal steroids are not recommended at less than 22 weeks due to lack of evidence of benefit, and they continue to be recommended at 24 weeks and beyond. ●

- Antenatal corticosteroids may be considered at 22 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation if, after thorough patient counseling, neonatal resuscitation is desired and planned by the family.

- The overall likelihood of survival and survival without major morbidities continues to be very low in the periviable period, especially at 22 weeks. Gestational age is only one of the many factors that must be considered in the shared decision making for this very difficult decision.

- Palliative care is a valid and appropriate option for patients facing a periviable delivery after appropriate counseling or after evaluation of the infant has occurred after birth.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 387. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. October 2020. www.cdc.gov/nchs /data/databriefs/db387-H.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- To MS, Skentou C, Chan C, et al. Cervical assessment at the routine 23-week scan: standardizing techniques. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:217-219.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65-e90.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement: use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:B16-B18.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:127-136.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus no. 6: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e187-e199.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 387. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. October 2020. www.cdc.gov/nchs /data/databriefs/db387-H.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- To MS, Skentou C, Chan C, et al. Cervical assessment at the routine 23-week scan: standardizing techniques. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:217-219.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65-e90.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement: use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:B16-B18.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:127-136.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus no. 6: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e187-e199.

The troubling trend of repackaging feminine hygiene products for the next generation

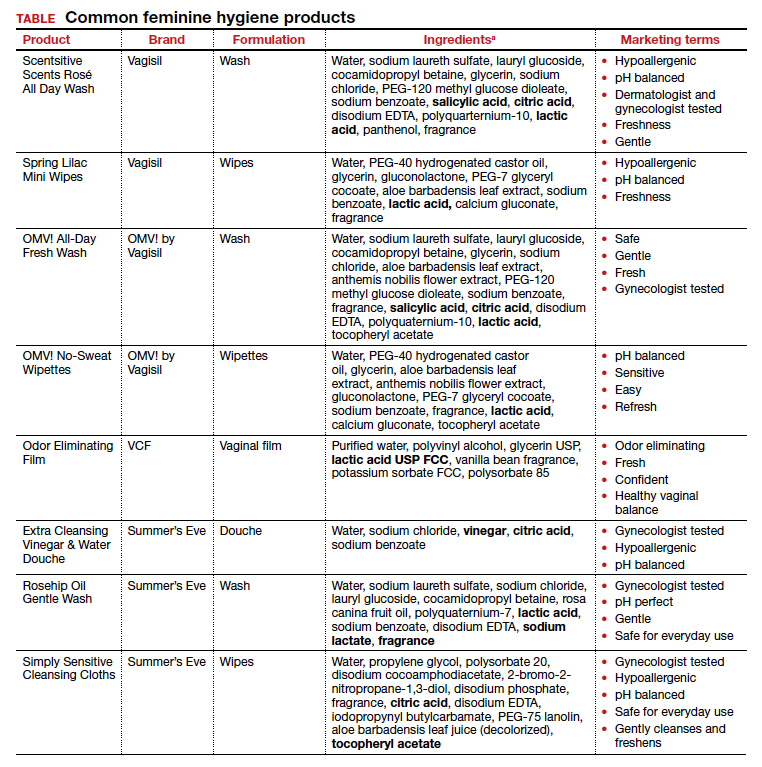

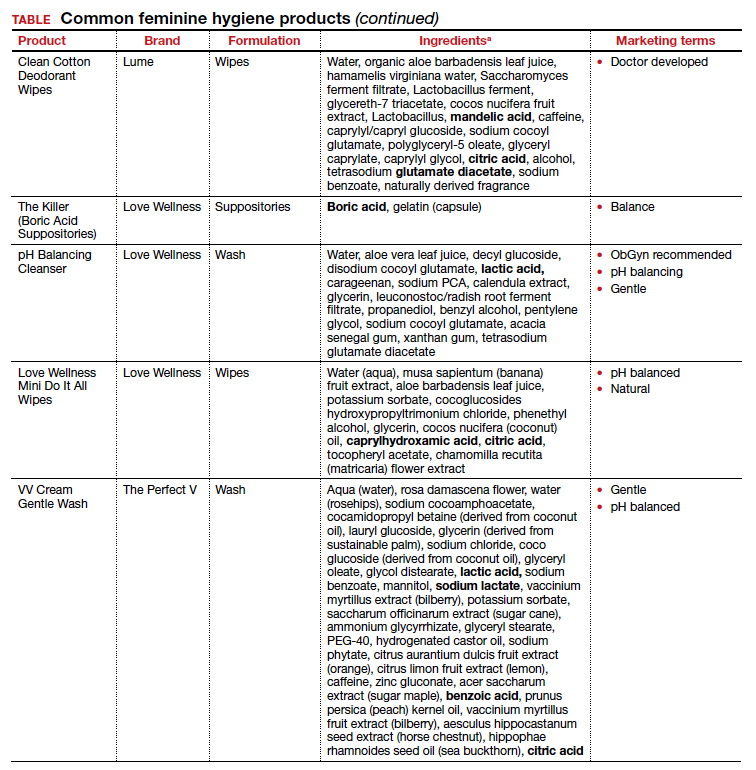

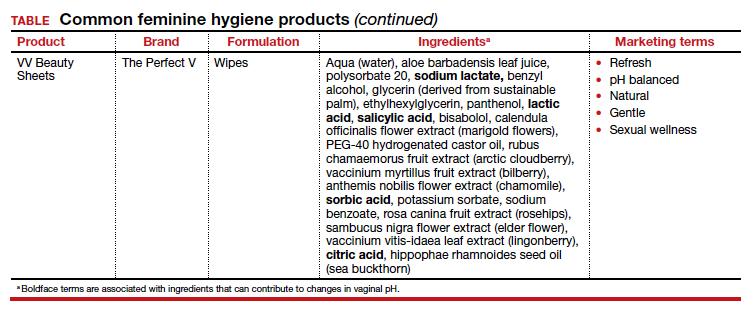

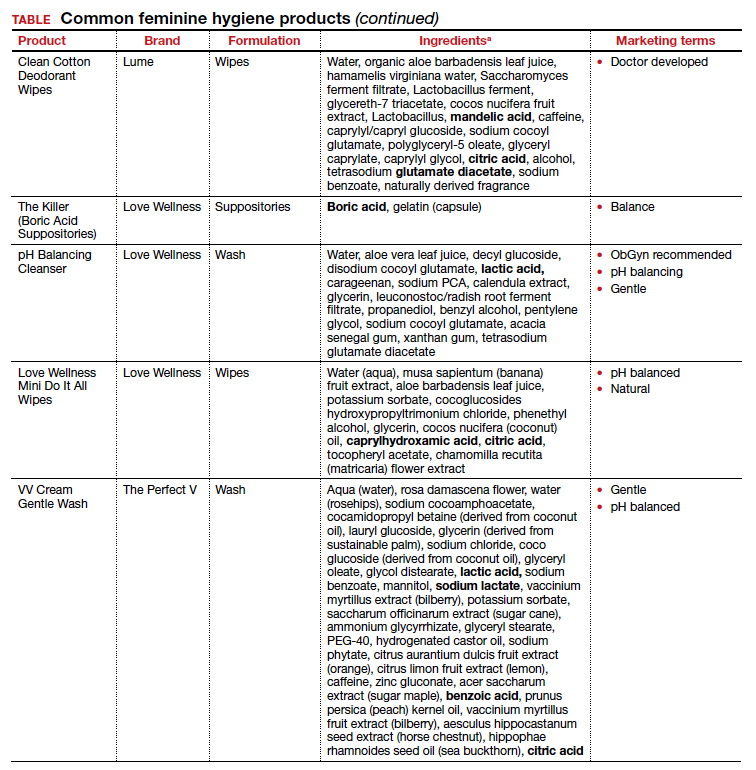

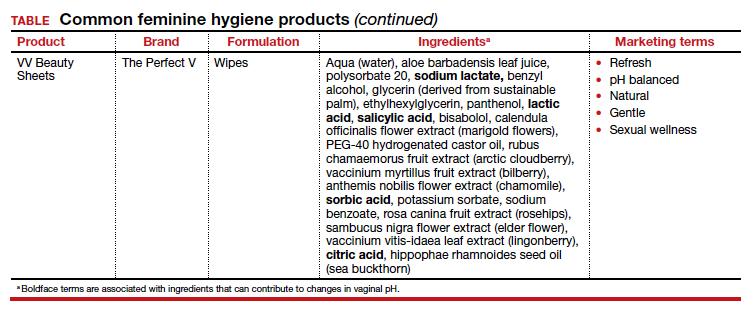

Feminine hygiene products have been commercially available for decades. They are commonly marketed to reduce odor or clean vaginal discharge and menses. Multiple formulas are available as topical washes, wipes, creams, sprays, powders, deodorants, and douches.1 Products on the market range from those used externally on the vulva, such as wipes and sprays, to liquid solutions used intravaginally, such as washes and douches.

Who uses feminine hygiene products?

According to a 2006 study, the majority of women who use douches started using them between age 15 and 19 years, but some women initiate this practice habit as early as age 10 to 14.1 Predictably, women who douche are more likely to perceive douche products as safe.1

Demographic data on douche utilization are mixed: Some studies show that there are no significant racial differences in douching practices,2 while others have found that Black and African American women are more likely to practice douching than White and Hispanic women.1,3 Studies have shown a significant difference in attitudes toward douching and knowledge of normal vaginal symptoms among US racial demographics, although this must be examined through the historical context of racism and the lens of medical anthropology.4

Women cite that common reasons they use feminine hygiene products are to feel clean, to control odor, and to use after menses and intercourse.1,2

Modern marketing approaches

From wipes to soaps to douches, feminine hygiene products often are advertised to promote “funk-free periods”5 and “freshness,” fostering an environment in which women and men develop unrealistic standards for what is considered normal genital odor and resulting in poor body image.6

Recently, Vagisil (Combe Incorporated) marketing efforts faced backlash from the ObGyn community for targeting younger populations with a specific product line for adolescents called OMV! In addition, attention has been drawn to VCF vaginal odor eliminating film (Apothecus Pharmaceutical Corp), small stamp-sized dissolving films that are placed in the vaginal canal in contact with the epithelium. This product has entered the market of feminine hygiene products accompanied by slogans of eliminating “feminine odor” and providing “confidence for women to be intimate.”

Continue to: Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome...

Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome

Frequent use of feminine hygiene products has been associated with recurrent vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, and general irritation/itch,7,8 which can cause more discharge and odor. Ironically, this may result in women using the product more frequently since they often seek out these products to eliminate odor and discharge.1,2

The pH of the vagina changes during a woman’s lifetime, but in the reproductive years, the normal pH range is typically 3.8 to 4.4.9 This range allows for a normal vaginal flora to form with bacteria such as Lactobacillus species and Gardnerella vaginalis, while feminine hygiene products have a wide range of pH.9,10

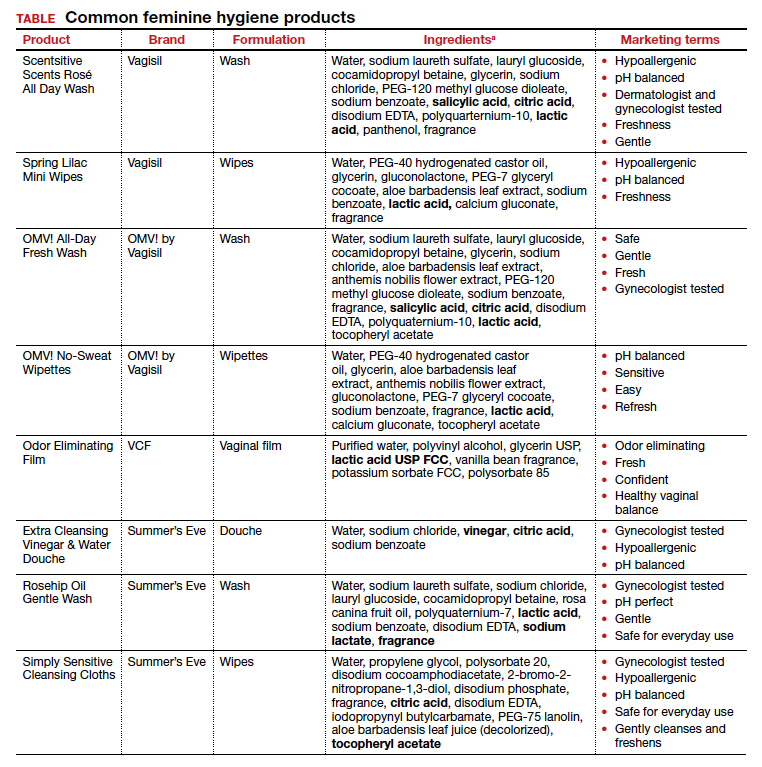

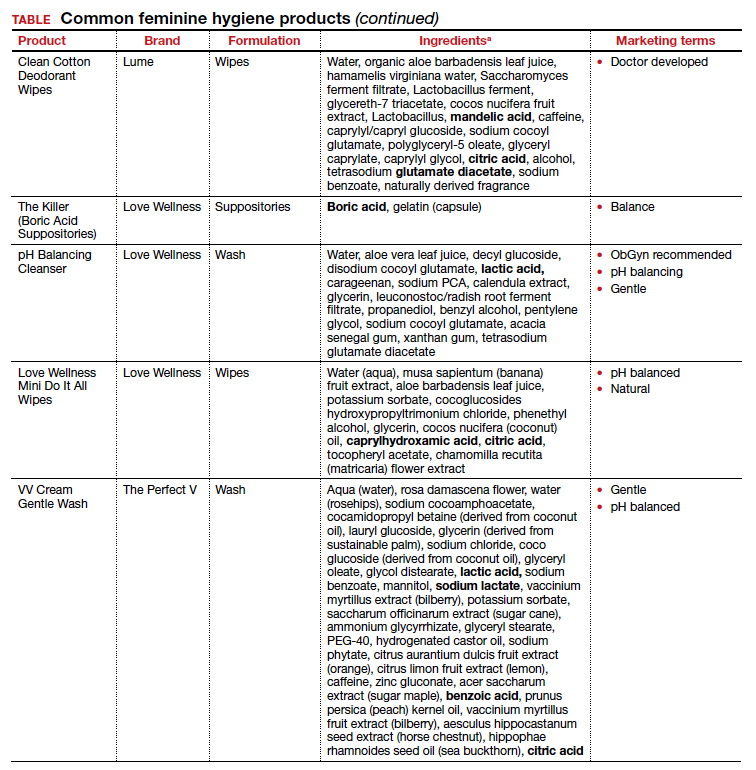

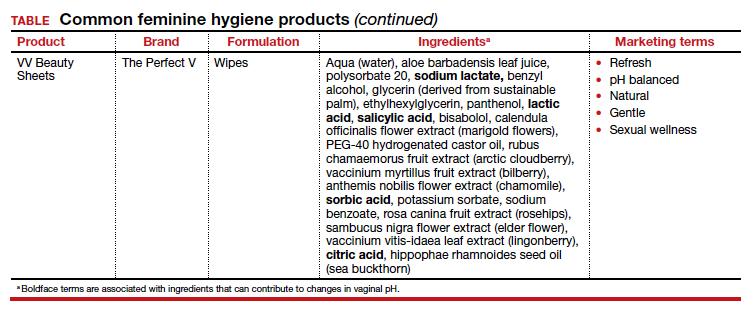

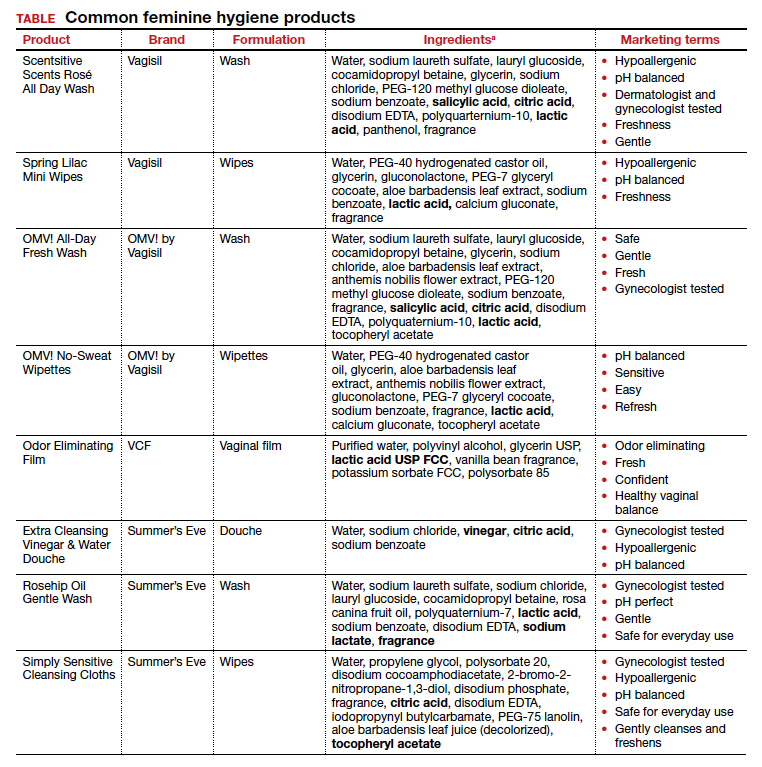

Regardless of the formulation, most feminine hygiene products contain ingredients and compositions that potentially are detrimental to the health of the vulva and vagina. Many products contain acidic ingredients, such as citric acid, lactic acid, and dehydroacetic acid, that can alter the vaginal pH and weaken the vaginal barrier by wiping out normal vaginal flora10 despite being advertised for use on “sensitive areas” (TABLE). Lactic acid also has been found to increase diverse anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal microbiome.11 Some feminine hygiene products have been shown to suppress Lactobacillus growth at 2 hours after use and to kill all lactobacilli at 24 hours.10 Shifts in microbiota numbers often occur when the vaginal pH has been altered, as is frequently the case with feminine hygiene products. In the absence of microbiome bacteria, the presence of vaginal hygiene products has been shown to increase interleukin-8 (IL-8), suggesting a proinflammatory reaction.10

A study in the United Kingdom found that women who used bubble bath, antiseptics, or douche products had a higher incidence of bacterial vaginosis compared with women who did not use such products.7 Women in Canada who used feminine hygiene products were more likely to report adverse conditions, including yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, urinary tract infections, and sexually transmitted diseases.8 Furthermore, a significant association exists between vaginal douching and endometrial infection by bacterial vaginosis–associated organisms.12

Additionally, a study that analyzed volatile organic compound levels in the blood with the use of feminine hygiene products revealed a significant positive dose-exposure relationship between the frequency of vaginal douching in the last 6 months and concentrations of 1,4-dichloromethane, one of the volatile organic compounds.3 This points to the issue of not only disruption of pH and vaginal flora but also to the introduction of harmful substances that can further disrupt the vaginal barrier.

Understand the products to help educate patients

Use of feminine hygiene products is common among women. While women depend on the market to filter out products that are considered unsafe or may have harmful side effects,1 unfortunately that is not necessarily the case. With increasingly more feminine products on the market and the target demographic becoming younger, women of all ages are susceptible to misinformation that could affect their vaginal health long term.

It is vital that clinicians understand the topical effects of these products in order to properly educate and counsel patients. Ultimately, research on feminine hygiene products is limited and, as more products come to market, we must continue to reassess the effects of topical products on the vaginal epithelium and vulvar tissues. ●

- Grimley DM, Annang L, Foushee HR, et al. Vaginal douches and other feminine hygiene products: women’s practices and perceptions of product safety. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:303-310. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0054-y.

- Foch BJ, McDaniel ND, Chacko MR. Racial differences in vaginal douching knowledge, attitude, and practices among sexually active adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;14:29-33. doi: 10.1016/S1083-3188(00)00080-2.

- Lin N, Ding N, Meza-Wilson E, et al. Volatile organic compounds in feminine hygiene products sold in the US market: a survey of products and health risks. Environ Int. 2020;144:105740. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105740.

- Wayne State University Digital Commons. Guy-Lee AK. Rituals reproducing race: African American women’s feminine hygiene practices, shared experiences, and power. 2017. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1806. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- YouTube. OMV! by Vagisil—Intimate care products designed by teens. July 10, 2020. www.youtube.com/ watch?v=VkVsCagrAw0. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Jenkins A, O’Doherty KC. The clean vagina, the healthy vagina, and the dirty vagina: exploring women’s portrayals of the vagina in relation to vaginal cleansing product use. Fem Psychol. 2021;31:192-211. doi: 10.1177/0959353520944144.

- Rajamanoharan S, Low N, Jones SB, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, ethnicity, and the use of genital cleansing agents: a case control study. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:404-409.

- Crann SE, Cunningham S, Albert A, et al. Vaginal health and hygiene practices and product use in Canada: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:52. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0543-y.

- Chen Y, Bruning E, Rubino J, et al. Role of female intimate hygiene in vulvovaginal health: global hygiene practices and product usage. Womens Health (London). 2017;13:58-67. doi: 10.1177/1745505717731011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd. v24i0.19703.

- Van der Veer C, Bruisten SM, Van Houdt R, et al. Effects of an over-the-counter lactic-acid containing intra-vaginal douching product on the vaginal microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:168. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1545-0.

- Gondwe T, Ness R, Totten PA, et al. Novel bacterial vaginosis-associated organisms mediate the relationship between vaginal douching and pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2020;96:439-444. doi: 10.1136/ sextrans-2019-054191.

Feminine hygiene products have been commercially available for decades. They are commonly marketed to reduce odor or clean vaginal discharge and menses. Multiple formulas are available as topical washes, wipes, creams, sprays, powders, deodorants, and douches.1 Products on the market range from those used externally on the vulva, such as wipes and sprays, to liquid solutions used intravaginally, such as washes and douches.

Who uses feminine hygiene products?

According to a 2006 study, the majority of women who use douches started using them between age 15 and 19 years, but some women initiate this practice habit as early as age 10 to 14.1 Predictably, women who douche are more likely to perceive douche products as safe.1

Demographic data on douche utilization are mixed: Some studies show that there are no significant racial differences in douching practices,2 while others have found that Black and African American women are more likely to practice douching than White and Hispanic women.1,3 Studies have shown a significant difference in attitudes toward douching and knowledge of normal vaginal symptoms among US racial demographics, although this must be examined through the historical context of racism and the lens of medical anthropology.4

Women cite that common reasons they use feminine hygiene products are to feel clean, to control odor, and to use after menses and intercourse.1,2

Modern marketing approaches

From wipes to soaps to douches, feminine hygiene products often are advertised to promote “funk-free periods”5 and “freshness,” fostering an environment in which women and men develop unrealistic standards for what is considered normal genital odor and resulting in poor body image.6

Recently, Vagisil (Combe Incorporated) marketing efforts faced backlash from the ObGyn community for targeting younger populations with a specific product line for adolescents called OMV! In addition, attention has been drawn to VCF vaginal odor eliminating film (Apothecus Pharmaceutical Corp), small stamp-sized dissolving films that are placed in the vaginal canal in contact with the epithelium. This product has entered the market of feminine hygiene products accompanied by slogans of eliminating “feminine odor” and providing “confidence for women to be intimate.”

Continue to: Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome...

Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome

Frequent use of feminine hygiene products has been associated with recurrent vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, and general irritation/itch,7,8 which can cause more discharge and odor. Ironically, this may result in women using the product more frequently since they often seek out these products to eliminate odor and discharge.1,2

The pH of the vagina changes during a woman’s lifetime, but in the reproductive years, the normal pH range is typically 3.8 to 4.4.9 This range allows for a normal vaginal flora to form with bacteria such as Lactobacillus species and Gardnerella vaginalis, while feminine hygiene products have a wide range of pH.9,10

Regardless of the formulation, most feminine hygiene products contain ingredients and compositions that potentially are detrimental to the health of the vulva and vagina. Many products contain acidic ingredients, such as citric acid, lactic acid, and dehydroacetic acid, that can alter the vaginal pH and weaken the vaginal barrier by wiping out normal vaginal flora10 despite being advertised for use on “sensitive areas” (TABLE). Lactic acid also has been found to increase diverse anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal microbiome.11 Some feminine hygiene products have been shown to suppress Lactobacillus growth at 2 hours after use and to kill all lactobacilli at 24 hours.10 Shifts in microbiota numbers often occur when the vaginal pH has been altered, as is frequently the case with feminine hygiene products. In the absence of microbiome bacteria, the presence of vaginal hygiene products has been shown to increase interleukin-8 (IL-8), suggesting a proinflammatory reaction.10

A study in the United Kingdom found that women who used bubble bath, antiseptics, or douche products had a higher incidence of bacterial vaginosis compared with women who did not use such products.7 Women in Canada who used feminine hygiene products were more likely to report adverse conditions, including yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, urinary tract infections, and sexually transmitted diseases.8 Furthermore, a significant association exists between vaginal douching and endometrial infection by bacterial vaginosis–associated organisms.12

Additionally, a study that analyzed volatile organic compound levels in the blood with the use of feminine hygiene products revealed a significant positive dose-exposure relationship between the frequency of vaginal douching in the last 6 months and concentrations of 1,4-dichloromethane, one of the volatile organic compounds.3 This points to the issue of not only disruption of pH and vaginal flora but also to the introduction of harmful substances that can further disrupt the vaginal barrier.

Understand the products to help educate patients

Use of feminine hygiene products is common among women. While women depend on the market to filter out products that are considered unsafe or may have harmful side effects,1 unfortunately that is not necessarily the case. With increasingly more feminine products on the market and the target demographic becoming younger, women of all ages are susceptible to misinformation that could affect their vaginal health long term.

It is vital that clinicians understand the topical effects of these products in order to properly educate and counsel patients. Ultimately, research on feminine hygiene products is limited and, as more products come to market, we must continue to reassess the effects of topical products on the vaginal epithelium and vulvar tissues. ●

Feminine hygiene products have been commercially available for decades. They are commonly marketed to reduce odor or clean vaginal discharge and menses. Multiple formulas are available as topical washes, wipes, creams, sprays, powders, deodorants, and douches.1 Products on the market range from those used externally on the vulva, such as wipes and sprays, to liquid solutions used intravaginally, such as washes and douches.

Who uses feminine hygiene products?

According to a 2006 study, the majority of women who use douches started using them between age 15 and 19 years, but some women initiate this practice habit as early as age 10 to 14.1 Predictably, women who douche are more likely to perceive douche products as safe.1

Demographic data on douche utilization are mixed: Some studies show that there are no significant racial differences in douching practices,2 while others have found that Black and African American women are more likely to practice douching than White and Hispanic women.1,3 Studies have shown a significant difference in attitudes toward douching and knowledge of normal vaginal symptoms among US racial demographics, although this must be examined through the historical context of racism and the lens of medical anthropology.4

Women cite that common reasons they use feminine hygiene products are to feel clean, to control odor, and to use after menses and intercourse.1,2

Modern marketing approaches

From wipes to soaps to douches, feminine hygiene products often are advertised to promote “funk-free periods”5 and “freshness,” fostering an environment in which women and men develop unrealistic standards for what is considered normal genital odor and resulting in poor body image.6

Recently, Vagisil (Combe Incorporated) marketing efforts faced backlash from the ObGyn community for targeting younger populations with a specific product line for adolescents called OMV! In addition, attention has been drawn to VCF vaginal odor eliminating film (Apothecus Pharmaceutical Corp), small stamp-sized dissolving films that are placed in the vaginal canal in contact with the epithelium. This product has entered the market of feminine hygiene products accompanied by slogans of eliminating “feminine odor” and providing “confidence for women to be intimate.”

Continue to: Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome...

Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome

Frequent use of feminine hygiene products has been associated with recurrent vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, and general irritation/itch,7,8 which can cause more discharge and odor. Ironically, this may result in women using the product more frequently since they often seek out these products to eliminate odor and discharge.1,2

The pH of the vagina changes during a woman’s lifetime, but in the reproductive years, the normal pH range is typically 3.8 to 4.4.9 This range allows for a normal vaginal flora to form with bacteria such as Lactobacillus species and Gardnerella vaginalis, while feminine hygiene products have a wide range of pH.9,10

Regardless of the formulation, most feminine hygiene products contain ingredients and compositions that potentially are detrimental to the health of the vulva and vagina. Many products contain acidic ingredients, such as citric acid, lactic acid, and dehydroacetic acid, that can alter the vaginal pH and weaken the vaginal barrier by wiping out normal vaginal flora10 despite being advertised for use on “sensitive areas” (TABLE). Lactic acid also has been found to increase diverse anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal microbiome.11 Some feminine hygiene products have been shown to suppress Lactobacillus growth at 2 hours after use and to kill all lactobacilli at 24 hours.10 Shifts in microbiota numbers often occur when the vaginal pH has been altered, as is frequently the case with feminine hygiene products. In the absence of microbiome bacteria, the presence of vaginal hygiene products has been shown to increase interleukin-8 (IL-8), suggesting a proinflammatory reaction.10

A study in the United Kingdom found that women who used bubble bath, antiseptics, or douche products had a higher incidence of bacterial vaginosis compared with women who did not use such products.7 Women in Canada who used feminine hygiene products were more likely to report adverse conditions, including yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, urinary tract infections, and sexually transmitted diseases.8 Furthermore, a significant association exists between vaginal douching and endometrial infection by bacterial vaginosis–associated organisms.12

Additionally, a study that analyzed volatile organic compound levels in the blood with the use of feminine hygiene products revealed a significant positive dose-exposure relationship between the frequency of vaginal douching in the last 6 months and concentrations of 1,4-dichloromethane, one of the volatile organic compounds.3 This points to the issue of not only disruption of pH and vaginal flora but also to the introduction of harmful substances that can further disrupt the vaginal barrier.

Understand the products to help educate patients

Use of feminine hygiene products is common among women. While women depend on the market to filter out products that are considered unsafe or may have harmful side effects,1 unfortunately that is not necessarily the case. With increasingly more feminine products on the market and the target demographic becoming younger, women of all ages are susceptible to misinformation that could affect their vaginal health long term.

It is vital that clinicians understand the topical effects of these products in order to properly educate and counsel patients. Ultimately, research on feminine hygiene products is limited and, as more products come to market, we must continue to reassess the effects of topical products on the vaginal epithelium and vulvar tissues. ●

- Grimley DM, Annang L, Foushee HR, et al. Vaginal douches and other feminine hygiene products: women’s practices and perceptions of product safety. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:303-310. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0054-y.

- Foch BJ, McDaniel ND, Chacko MR. Racial differences in vaginal douching knowledge, attitude, and practices among sexually active adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;14:29-33. doi: 10.1016/S1083-3188(00)00080-2.

- Lin N, Ding N, Meza-Wilson E, et al. Volatile organic compounds in feminine hygiene products sold in the US market: a survey of products and health risks. Environ Int. 2020;144:105740. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105740.

- Wayne State University Digital Commons. Guy-Lee AK. Rituals reproducing race: African American women’s feminine hygiene practices, shared experiences, and power. 2017. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1806. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- YouTube. OMV! by Vagisil—Intimate care products designed by teens. July 10, 2020. www.youtube.com/ watch?v=VkVsCagrAw0. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Jenkins A, O’Doherty KC. The clean vagina, the healthy vagina, and the dirty vagina: exploring women’s portrayals of the vagina in relation to vaginal cleansing product use. Fem Psychol. 2021;31:192-211. doi: 10.1177/0959353520944144.

- Rajamanoharan S, Low N, Jones SB, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, ethnicity, and the use of genital cleansing agents: a case control study. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:404-409.

- Crann SE, Cunningham S, Albert A, et al. Vaginal health and hygiene practices and product use in Canada: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:52. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0543-y.

- Chen Y, Bruning E, Rubino J, et al. Role of female intimate hygiene in vulvovaginal health: global hygiene practices and product usage. Womens Health (London). 2017;13:58-67. doi: 10.1177/1745505717731011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd. v24i0.19703.

- Van der Veer C, Bruisten SM, Van Houdt R, et al. Effects of an over-the-counter lactic-acid containing intra-vaginal douching product on the vaginal microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:168. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1545-0.

- Gondwe T, Ness R, Totten PA, et al. Novel bacterial vaginosis-associated organisms mediate the relationship between vaginal douching and pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2020;96:439-444. doi: 10.1136/ sextrans-2019-054191.

- Grimley DM, Annang L, Foushee HR, et al. Vaginal douches and other feminine hygiene products: women’s practices and perceptions of product safety. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:303-310. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0054-y.

- Foch BJ, McDaniel ND, Chacko MR. Racial differences in vaginal douching knowledge, attitude, and practices among sexually active adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;14:29-33. doi: 10.1016/S1083-3188(00)00080-2.

- Lin N, Ding N, Meza-Wilson E, et al. Volatile organic compounds in feminine hygiene products sold in the US market: a survey of products and health risks. Environ Int. 2020;144:105740. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105740.

- Wayne State University Digital Commons. Guy-Lee AK. Rituals reproducing race: African American women’s feminine hygiene practices, shared experiences, and power. 2017. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1806. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- YouTube. OMV! by Vagisil—Intimate care products designed by teens. July 10, 2020. www.youtube.com/ watch?v=VkVsCagrAw0. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Jenkins A, O’Doherty KC. The clean vagina, the healthy vagina, and the dirty vagina: exploring women’s portrayals of the vagina in relation to vaginal cleansing product use. Fem Psychol. 2021;31:192-211. doi: 10.1177/0959353520944144.

- Rajamanoharan S, Low N, Jones SB, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, ethnicity, and the use of genital cleansing agents: a case control study. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:404-409.

- Crann SE, Cunningham S, Albert A, et al. Vaginal health and hygiene practices and product use in Canada: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:52. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0543-y.

- Chen Y, Bruning E, Rubino J, et al. Role of female intimate hygiene in vulvovaginal health: global hygiene practices and product usage. Womens Health (London). 2017;13:58-67. doi: 10.1177/1745505717731011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd. v24i0.19703.