User login

Hematocrit, White Blood Cells, and Thrombotic Events in the Veteran Population With Polycythemia Vera

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm affecting 44 to 57 individuals per 100,000 in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in hyperproliferation of mature myeloid lineage cells.2 Sustained erythrocytosis is a hallmark of PV, although many patients also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.2,3 These patients have increased inherent thrombotic risk with arterial events reported to occur at rates of 7 to 21/1000 person-years and venous thrombotic events at 5 to 20/1000 person-years.4-7 Thrombotic and cardiovascular events are leading causes of morbidity and mortality, resulting in a reduced overall survival of patients with PV compared with the general population.3,8-10

Blood Cell Counts and Thrombotic Events in PV

Treatment strategies for patients with PV mainly aim to prevent or manage thrombotic and bleeding complications through normalization of blood counts.11 Hematocrit (Hct) control has been reported to be associated with reduced thrombotic risk in patients with PV. This was shown and popularized by the prospective, randomized Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial in which participants were randomized 1:1 to maintaining either a low (< 45%) or high (45%-50%) Hct for 5 years to examine the long-term effects of more- or less-intensive cytoreductive therapy.12 Patients in the low-Hct group were found to have a lower rate of death from cardiovascular events or major thrombosis (1.1/100 person-years in the low-Hct group vs 4.4 in the high-Hct group; hazard ratio [HR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-10.53; P = .007). Likewise, cardiovascular events occurred at a lower rate in patients in the low-Hct group compared with the high-Hct group (4.4% vs 10.9% of patients, respectively; HR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.19-6.12; P = .02).12

Leukocytosis has also been linked to elevated risk for vascular events as shown in several studies, including the real-world European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) observational study and a post hoc subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study.13,14 In a multivariate, time-dependent analysis in ECLAP, patients with white blood cell (WBC) counts > 15 × 109/L had a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis compared with those who had lower WBC counts, with higher WBC count more strongly associated with arterial than venous thromboembolism.13 In CYTO-PV, a significant correlation between elevated WBC count (≥ 11 × 109/L vs reference level of < 7 × 109/L) and time-dependent risk of major thrombosis was shown (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.24-12.3; P = .02).14 Likewise, WBC count ≥ 11 × 109/L was found to be a predictor of subsequent venous events in a separate single-center multivariate analysis of patients with PV.8

Although CYTO-PV remains one of the largest prospective landmark studies in PV demonstrating the impact of Hct control on thrombosis, it is worthwhile to note that the patients in the high-Hct group who received less frequent myelosuppressive therapy with hydroxyurea than the low-Hct group also had higher WBC counts.12,15 Work is needed to determine the relative effects of high Hct and high WBC counts on PV independent of each other.

The Veteran Population with PV

Two recently published retrospective analyses from Parasuraman and colleagues used data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, with an aim to replicate findings from CYTO-PV in a real-world population.16,17 The 2 analyses focused independently on the effects of Hct control and WBC count on the risk of a thrombotic event in patients with PV.

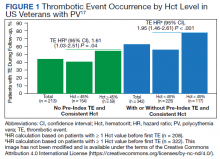

In the first retrospective analysis, 213 patients with PV and no prior thrombosis were placed into groups based on whether Hct levels were consistently either < 45% or ≥ 45% throughout the study period.17 The mean follow-up time was 2.3 years, during which 44.1% of patients experienced a thrombotic event (Figure 1). Patients with Hct levels < 45% had a lower rate of thrombotic events compared to those with levels ≥ 45% (40.3% vs 54.2%, respectively; HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51; P = .04). In a sensitivity analysis that included patients with pre-index thrombotic events (N = 342), similar results were noted (55.6% vs 76.9% between the < 45% and ≥ 45% groups, respectively; HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46-2.61; P < .001).

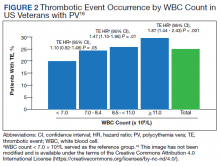

In the second analysis, the authors investigated the relationship between WBC counts and thrombotic events.16 Evaluable patients (N = 1565) were grouped into 1 of 4 cohorts based on the last WBC measurement taken during the study period before a thrombotic event or through the end of follow-up: (1) WBC < 7.0 × 109/L, (2) 7.0 to 8.4 × 109/L, (3) 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L, or (4) ≥ 11.0 × 109/L. Mean follow-up time ranged from 3.6 to 4.5 years among WBC count cohorts, during which 24.9% of patients experienced a thrombotic event. Compared with the reference cohort (WBC < 7.0 × 109/L), a significant positive association between WBC counts and thrombotic event occurrence was observed among patients with WBC counts of 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96; P < .01) and ≥ 11 × 109/L (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.44-2.43; P < .001) (Figure 2).16 When including all patients in a sensitivity analysis regardless of whether they experienced thrombotic events before the index date (N = 1876), similar results were obtained (7.0-8.4 × 109/L group: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.97-1.55; P = .0959; 8.5 - 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81; P = .0062; ≥ 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001; compared with < 7.0 × 109/L reference group). Rates of phlebotomy and cytoreductive treatments were similar across groups.16

Some limitations to these studies are attributable to their retrospective design, reliance on health records, and the VHA population characteristics, which differ from the general population. For example, in this analysis, patients with PV in the VHA population had significantly increased risk of thrombotic events, even at a lower WBC count threshold (≥ 8.5 × 109/L) compared with those reported in CYTO-PV (≥ 11 × 109/L). Furthermore, approximately one-third of patients had elevated WBC levels, compared with 25.5% in the CYTO-PV study.14,16 This is most likely due to the unique nature of the VHA patient population, who are predominantly older adult men and generally have a higher comorbidity burden. A notable pre-index comorbidity burden was reported in the VHA population in the Hct analysis, even when compared to patients with PV in the general US population (Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 1.3 vs 0.8).6,17 Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use, which are most common among the VHA population, are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events.18,19 However, whether these higher levels of comorbidities affected the type of treatments they received was not elucidated, and the effectiveness of treatments to maintain target Hct levels was not addressed in the study.

Current PV Management and Future Implications

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology in myeloproliferative neoplasms recommend maintaining Hct levels < 45% in patients with PV.11 Patients with high-risk disease (age ≥ 60 years and/or history of thrombosis) are monitored for new thrombosis or bleeding and are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, they receive low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, and are managed with pharmacologic cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy primarily consists of hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a for younger patients. Ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor, is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as second-line treatment for those with PV that is intolerant or unresponsive to hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a treatments.11,20 However, the role of cytoreductive therapy is not clear for patients with low-risk disease (age < 60 years and no history of thrombosis). These patients are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors, undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, are maintained on low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), and are monitored for indications for cytoreductive therapy, which include any new thrombosis or disease-related major bleeding, frequent or persistent need for phlebotomy with poor tolerance for the procedure, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and disease-related symptoms (eg, aquagenic pruritus, night sweats, fatigue).

Even though the current guidelines recommend maintaining a target Hct of < 45% in patients with high-risk PV, the role of Hct as the main determinant of thrombotic risk in patients with PV is still debated.21 In JAK2V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia, Hct levels are usually normal but risk of thrombosis is nevertheless still significant.22 The risk of thrombosis is significantly lower in primary familial and congenital polycythemia and much lower in secondary erythrocytosis such as cyanotic heart disease, long-term native dwellers of high altitude, and those with high-oxygen–affinity hemoglobins.21,23 In secondary erythrocytosis from hypoxia or upregulated hypoxic pathway such as hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) mutation and Chuvash erythrocytosis, the risk of thrombosis is more associated with the upregulated HIF pathway and its downstream consequences, rather than the elevated Hct level.24

However, most current literature supports the association of increased risk of thrombosis with higher Hct and high WBC count in patients with PV. In addition, the underlying mechanism of thrombogenesis still remains elusive; it is likely a complex process that involves interactions among multiple components, including elevated blood counts arising from clonal hematopoiesis, JAK2V617F allele burden, and platelet and WBC activation and their interaction with endothelial cells and inflammatory cytokines.25

Nevertheless, Hct control and aspirin use are current standard of care for patients with PV to mitigate thrombotic risk, and the results from the 2 analyses by Parasuraman and colleagues, using real-world data from the VHA, support the current practice guidelines to maintain Hct < 45% in these patients. They also provide additional support for considering WBC counts when determining patient risk and treatment plans. Although treatment response criteria from the European LeukemiaNet include achieving normal WBC levels to decrease the risk of thrombosis, current NCCN guidelines do not include WBC counts as a component for establishing patient risk or provide a target WBC count to guide patient management.11,26,27 Updates to these practice guidelines may be warranted. In addition, further study is needed to understand the mechanism of thrombogenesis in PV and other myeloproliferative disorders in order to develop novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Tania Iqbal, PhD, an employee of ICON (North Wales, PA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE).

1. Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595-600. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.813500

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

3. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1874-1881. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.163

4. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R, et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2224-2232. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062

5. Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110(3):840-846. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287

6. Goyal RK, Davis KL, Cote I, Mounedji N, Kaye JA. Increased incidence of thromboembolic event rates in patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera: results from an observational cohort study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2014;124:4840. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.4840.4840

7. Barbui T, Carobbio A, Rumi E, et al. In contemporary patients with polycythemia vera, rates of thrombosis and risk factors delineate a new clinical epidemiology. Blood. 2014;124(19):3021-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-591610 8. Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, et al. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(12):662. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6

9. Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV. Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, and emerging treatment options. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):1965-1976. doi:10.1007/s00277-014-2205-y

10. Hultcrantz M, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM-L, et al. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2995-3001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1925

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in myeloproliferative neoplasms (Version 1.2020). Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

12. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

13. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Barbui T, et al. Leukocytosis as a major thrombotic risk factor in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2007;109(6):2446-2452. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-042515

14. Barbui T, Masciulli A, Marfisi MR, et al. White blood cell counts and thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study. Blood. 2015;126(4):560-561. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-638593

15. Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Treatment target in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1555-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1301262

16. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):63-69. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010

17. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Hematocrit levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2533-2539. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03793-w

18. WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1332-e1345. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3.

19. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

20. Jakafi. Package insert. Incyte Corporation; 2020.

21. Gordeuk VR, Key NS, Prchal JT. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):653-658. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.210732

22. Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117(22):5857-5859. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-339002

23. Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87(6):1954-1959. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1954

24. Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):e87-e90. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.216267

25. Kroll MH, Michaelis LC, Verstovsek S. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in polycythemia vera. Blood Rev. 2015;29(4):215-221. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.002

26. Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057-1069. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1

27. Barosi G, Mesa R, Finazzi G, et al. Revised response criteria for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: an ELN and IWG-MRT consensus project. Blood. 2013;121(23):4778-4781. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-478891

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm affecting 44 to 57 individuals per 100,000 in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in hyperproliferation of mature myeloid lineage cells.2 Sustained erythrocytosis is a hallmark of PV, although many patients also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.2,3 These patients have increased inherent thrombotic risk with arterial events reported to occur at rates of 7 to 21/1000 person-years and venous thrombotic events at 5 to 20/1000 person-years.4-7 Thrombotic and cardiovascular events are leading causes of morbidity and mortality, resulting in a reduced overall survival of patients with PV compared with the general population.3,8-10

Blood Cell Counts and Thrombotic Events in PV

Treatment strategies for patients with PV mainly aim to prevent or manage thrombotic and bleeding complications through normalization of blood counts.11 Hematocrit (Hct) control has been reported to be associated with reduced thrombotic risk in patients with PV. This was shown and popularized by the prospective, randomized Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial in which participants were randomized 1:1 to maintaining either a low (< 45%) or high (45%-50%) Hct for 5 years to examine the long-term effects of more- or less-intensive cytoreductive therapy.12 Patients in the low-Hct group were found to have a lower rate of death from cardiovascular events or major thrombosis (1.1/100 person-years in the low-Hct group vs 4.4 in the high-Hct group; hazard ratio [HR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-10.53; P = .007). Likewise, cardiovascular events occurred at a lower rate in patients in the low-Hct group compared with the high-Hct group (4.4% vs 10.9% of patients, respectively; HR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.19-6.12; P = .02).12

Leukocytosis has also been linked to elevated risk for vascular events as shown in several studies, including the real-world European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) observational study and a post hoc subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study.13,14 In a multivariate, time-dependent analysis in ECLAP, patients with white blood cell (WBC) counts > 15 × 109/L had a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis compared with those who had lower WBC counts, with higher WBC count more strongly associated with arterial than venous thromboembolism.13 In CYTO-PV, a significant correlation between elevated WBC count (≥ 11 × 109/L vs reference level of < 7 × 109/L) and time-dependent risk of major thrombosis was shown (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.24-12.3; P = .02).14 Likewise, WBC count ≥ 11 × 109/L was found to be a predictor of subsequent venous events in a separate single-center multivariate analysis of patients with PV.8

Although CYTO-PV remains one of the largest prospective landmark studies in PV demonstrating the impact of Hct control on thrombosis, it is worthwhile to note that the patients in the high-Hct group who received less frequent myelosuppressive therapy with hydroxyurea than the low-Hct group also had higher WBC counts.12,15 Work is needed to determine the relative effects of high Hct and high WBC counts on PV independent of each other.

The Veteran Population with PV

Two recently published retrospective analyses from Parasuraman and colleagues used data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, with an aim to replicate findings from CYTO-PV in a real-world population.16,17 The 2 analyses focused independently on the effects of Hct control and WBC count on the risk of a thrombotic event in patients with PV.

In the first retrospective analysis, 213 patients with PV and no prior thrombosis were placed into groups based on whether Hct levels were consistently either < 45% or ≥ 45% throughout the study period.17 The mean follow-up time was 2.3 years, during which 44.1% of patients experienced a thrombotic event (Figure 1). Patients with Hct levels < 45% had a lower rate of thrombotic events compared to those with levels ≥ 45% (40.3% vs 54.2%, respectively; HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51; P = .04). In a sensitivity analysis that included patients with pre-index thrombotic events (N = 342), similar results were noted (55.6% vs 76.9% between the < 45% and ≥ 45% groups, respectively; HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46-2.61; P < .001).

In the second analysis, the authors investigated the relationship between WBC counts and thrombotic events.16 Evaluable patients (N = 1565) were grouped into 1 of 4 cohorts based on the last WBC measurement taken during the study period before a thrombotic event or through the end of follow-up: (1) WBC < 7.0 × 109/L, (2) 7.0 to 8.4 × 109/L, (3) 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L, or (4) ≥ 11.0 × 109/L. Mean follow-up time ranged from 3.6 to 4.5 years among WBC count cohorts, during which 24.9% of patients experienced a thrombotic event. Compared with the reference cohort (WBC < 7.0 × 109/L), a significant positive association between WBC counts and thrombotic event occurrence was observed among patients with WBC counts of 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96; P < .01) and ≥ 11 × 109/L (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.44-2.43; P < .001) (Figure 2).16 When including all patients in a sensitivity analysis regardless of whether they experienced thrombotic events before the index date (N = 1876), similar results were obtained (7.0-8.4 × 109/L group: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.97-1.55; P = .0959; 8.5 - 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81; P = .0062; ≥ 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001; compared with < 7.0 × 109/L reference group). Rates of phlebotomy and cytoreductive treatments were similar across groups.16

Some limitations to these studies are attributable to their retrospective design, reliance on health records, and the VHA population characteristics, which differ from the general population. For example, in this analysis, patients with PV in the VHA population had significantly increased risk of thrombotic events, even at a lower WBC count threshold (≥ 8.5 × 109/L) compared with those reported in CYTO-PV (≥ 11 × 109/L). Furthermore, approximately one-third of patients had elevated WBC levels, compared with 25.5% in the CYTO-PV study.14,16 This is most likely due to the unique nature of the VHA patient population, who are predominantly older adult men and generally have a higher comorbidity burden. A notable pre-index comorbidity burden was reported in the VHA population in the Hct analysis, even when compared to patients with PV in the general US population (Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 1.3 vs 0.8).6,17 Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use, which are most common among the VHA population, are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events.18,19 However, whether these higher levels of comorbidities affected the type of treatments they received was not elucidated, and the effectiveness of treatments to maintain target Hct levels was not addressed in the study.

Current PV Management and Future Implications

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology in myeloproliferative neoplasms recommend maintaining Hct levels < 45% in patients with PV.11 Patients with high-risk disease (age ≥ 60 years and/or history of thrombosis) are monitored for new thrombosis or bleeding and are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, they receive low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, and are managed with pharmacologic cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy primarily consists of hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a for younger patients. Ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor, is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as second-line treatment for those with PV that is intolerant or unresponsive to hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a treatments.11,20 However, the role of cytoreductive therapy is not clear for patients with low-risk disease (age < 60 years and no history of thrombosis). These patients are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors, undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, are maintained on low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), and are monitored for indications for cytoreductive therapy, which include any new thrombosis or disease-related major bleeding, frequent or persistent need for phlebotomy with poor tolerance for the procedure, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and disease-related symptoms (eg, aquagenic pruritus, night sweats, fatigue).

Even though the current guidelines recommend maintaining a target Hct of < 45% in patients with high-risk PV, the role of Hct as the main determinant of thrombotic risk in patients with PV is still debated.21 In JAK2V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia, Hct levels are usually normal but risk of thrombosis is nevertheless still significant.22 The risk of thrombosis is significantly lower in primary familial and congenital polycythemia and much lower in secondary erythrocytosis such as cyanotic heart disease, long-term native dwellers of high altitude, and those with high-oxygen–affinity hemoglobins.21,23 In secondary erythrocytosis from hypoxia or upregulated hypoxic pathway such as hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) mutation and Chuvash erythrocytosis, the risk of thrombosis is more associated with the upregulated HIF pathway and its downstream consequences, rather than the elevated Hct level.24

However, most current literature supports the association of increased risk of thrombosis with higher Hct and high WBC count in patients with PV. In addition, the underlying mechanism of thrombogenesis still remains elusive; it is likely a complex process that involves interactions among multiple components, including elevated blood counts arising from clonal hematopoiesis, JAK2V617F allele burden, and platelet and WBC activation and their interaction with endothelial cells and inflammatory cytokines.25

Nevertheless, Hct control and aspirin use are current standard of care for patients with PV to mitigate thrombotic risk, and the results from the 2 analyses by Parasuraman and colleagues, using real-world data from the VHA, support the current practice guidelines to maintain Hct < 45% in these patients. They also provide additional support for considering WBC counts when determining patient risk and treatment plans. Although treatment response criteria from the European LeukemiaNet include achieving normal WBC levels to decrease the risk of thrombosis, current NCCN guidelines do not include WBC counts as a component for establishing patient risk or provide a target WBC count to guide patient management.11,26,27 Updates to these practice guidelines may be warranted. In addition, further study is needed to understand the mechanism of thrombogenesis in PV and other myeloproliferative disorders in order to develop novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Tania Iqbal, PhD, an employee of ICON (North Wales, PA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE).

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm affecting 44 to 57 individuals per 100,000 in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in hyperproliferation of mature myeloid lineage cells.2 Sustained erythrocytosis is a hallmark of PV, although many patients also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.2,3 These patients have increased inherent thrombotic risk with arterial events reported to occur at rates of 7 to 21/1000 person-years and venous thrombotic events at 5 to 20/1000 person-years.4-7 Thrombotic and cardiovascular events are leading causes of morbidity and mortality, resulting in a reduced overall survival of patients with PV compared with the general population.3,8-10

Blood Cell Counts and Thrombotic Events in PV

Treatment strategies for patients with PV mainly aim to prevent or manage thrombotic and bleeding complications through normalization of blood counts.11 Hematocrit (Hct) control has been reported to be associated with reduced thrombotic risk in patients with PV. This was shown and popularized by the prospective, randomized Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial in which participants were randomized 1:1 to maintaining either a low (< 45%) or high (45%-50%) Hct for 5 years to examine the long-term effects of more- or less-intensive cytoreductive therapy.12 Patients in the low-Hct group were found to have a lower rate of death from cardiovascular events or major thrombosis (1.1/100 person-years in the low-Hct group vs 4.4 in the high-Hct group; hazard ratio [HR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-10.53; P = .007). Likewise, cardiovascular events occurred at a lower rate in patients in the low-Hct group compared with the high-Hct group (4.4% vs 10.9% of patients, respectively; HR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.19-6.12; P = .02).12

Leukocytosis has also been linked to elevated risk for vascular events as shown in several studies, including the real-world European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) observational study and a post hoc subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study.13,14 In a multivariate, time-dependent analysis in ECLAP, patients with white blood cell (WBC) counts > 15 × 109/L had a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis compared with those who had lower WBC counts, with higher WBC count more strongly associated with arterial than venous thromboembolism.13 In CYTO-PV, a significant correlation between elevated WBC count (≥ 11 × 109/L vs reference level of < 7 × 109/L) and time-dependent risk of major thrombosis was shown (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.24-12.3; P = .02).14 Likewise, WBC count ≥ 11 × 109/L was found to be a predictor of subsequent venous events in a separate single-center multivariate analysis of patients with PV.8

Although CYTO-PV remains one of the largest prospective landmark studies in PV demonstrating the impact of Hct control on thrombosis, it is worthwhile to note that the patients in the high-Hct group who received less frequent myelosuppressive therapy with hydroxyurea than the low-Hct group also had higher WBC counts.12,15 Work is needed to determine the relative effects of high Hct and high WBC counts on PV independent of each other.

The Veteran Population with PV

Two recently published retrospective analyses from Parasuraman and colleagues used data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, with an aim to replicate findings from CYTO-PV in a real-world population.16,17 The 2 analyses focused independently on the effects of Hct control and WBC count on the risk of a thrombotic event in patients with PV.

In the first retrospective analysis, 213 patients with PV and no prior thrombosis were placed into groups based on whether Hct levels were consistently either < 45% or ≥ 45% throughout the study period.17 The mean follow-up time was 2.3 years, during which 44.1% of patients experienced a thrombotic event (Figure 1). Patients with Hct levels < 45% had a lower rate of thrombotic events compared to those with levels ≥ 45% (40.3% vs 54.2%, respectively; HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51; P = .04). In a sensitivity analysis that included patients with pre-index thrombotic events (N = 342), similar results were noted (55.6% vs 76.9% between the < 45% and ≥ 45% groups, respectively; HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46-2.61; P < .001).

In the second analysis, the authors investigated the relationship between WBC counts and thrombotic events.16 Evaluable patients (N = 1565) were grouped into 1 of 4 cohorts based on the last WBC measurement taken during the study period before a thrombotic event or through the end of follow-up: (1) WBC < 7.0 × 109/L, (2) 7.0 to 8.4 × 109/L, (3) 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L, or (4) ≥ 11.0 × 109/L. Mean follow-up time ranged from 3.6 to 4.5 years among WBC count cohorts, during which 24.9% of patients experienced a thrombotic event. Compared with the reference cohort (WBC < 7.0 × 109/L), a significant positive association between WBC counts and thrombotic event occurrence was observed among patients with WBC counts of 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96; P < .01) and ≥ 11 × 109/L (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.44-2.43; P < .001) (Figure 2).16 When including all patients in a sensitivity analysis regardless of whether they experienced thrombotic events before the index date (N = 1876), similar results were obtained (7.0-8.4 × 109/L group: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.97-1.55; P = .0959; 8.5 - 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81; P = .0062; ≥ 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001; compared with < 7.0 × 109/L reference group). Rates of phlebotomy and cytoreductive treatments were similar across groups.16

Some limitations to these studies are attributable to their retrospective design, reliance on health records, and the VHA population characteristics, which differ from the general population. For example, in this analysis, patients with PV in the VHA population had significantly increased risk of thrombotic events, even at a lower WBC count threshold (≥ 8.5 × 109/L) compared with those reported in CYTO-PV (≥ 11 × 109/L). Furthermore, approximately one-third of patients had elevated WBC levels, compared with 25.5% in the CYTO-PV study.14,16 This is most likely due to the unique nature of the VHA patient population, who are predominantly older adult men and generally have a higher comorbidity burden. A notable pre-index comorbidity burden was reported in the VHA population in the Hct analysis, even when compared to patients with PV in the general US population (Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 1.3 vs 0.8).6,17 Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use, which are most common among the VHA population, are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events.18,19 However, whether these higher levels of comorbidities affected the type of treatments they received was not elucidated, and the effectiveness of treatments to maintain target Hct levels was not addressed in the study.

Current PV Management and Future Implications

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology in myeloproliferative neoplasms recommend maintaining Hct levels < 45% in patients with PV.11 Patients with high-risk disease (age ≥ 60 years and/or history of thrombosis) are monitored for new thrombosis or bleeding and are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, they receive low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, and are managed with pharmacologic cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy primarily consists of hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a for younger patients. Ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor, is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as second-line treatment for those with PV that is intolerant or unresponsive to hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a treatments.11,20 However, the role of cytoreductive therapy is not clear for patients with low-risk disease (age < 60 years and no history of thrombosis). These patients are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors, undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, are maintained on low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), and are monitored for indications for cytoreductive therapy, which include any new thrombosis or disease-related major bleeding, frequent or persistent need for phlebotomy with poor tolerance for the procedure, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and disease-related symptoms (eg, aquagenic pruritus, night sweats, fatigue).

Even though the current guidelines recommend maintaining a target Hct of < 45% in patients with high-risk PV, the role of Hct as the main determinant of thrombotic risk in patients with PV is still debated.21 In JAK2V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia, Hct levels are usually normal but risk of thrombosis is nevertheless still significant.22 The risk of thrombosis is significantly lower in primary familial and congenital polycythemia and much lower in secondary erythrocytosis such as cyanotic heart disease, long-term native dwellers of high altitude, and those with high-oxygen–affinity hemoglobins.21,23 In secondary erythrocytosis from hypoxia or upregulated hypoxic pathway such as hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) mutation and Chuvash erythrocytosis, the risk of thrombosis is more associated with the upregulated HIF pathway and its downstream consequences, rather than the elevated Hct level.24

However, most current literature supports the association of increased risk of thrombosis with higher Hct and high WBC count in patients with PV. In addition, the underlying mechanism of thrombogenesis still remains elusive; it is likely a complex process that involves interactions among multiple components, including elevated blood counts arising from clonal hematopoiesis, JAK2V617F allele burden, and platelet and WBC activation and their interaction with endothelial cells and inflammatory cytokines.25

Nevertheless, Hct control and aspirin use are current standard of care for patients with PV to mitigate thrombotic risk, and the results from the 2 analyses by Parasuraman and colleagues, using real-world data from the VHA, support the current practice guidelines to maintain Hct < 45% in these patients. They also provide additional support for considering WBC counts when determining patient risk and treatment plans. Although treatment response criteria from the European LeukemiaNet include achieving normal WBC levels to decrease the risk of thrombosis, current NCCN guidelines do not include WBC counts as a component for establishing patient risk or provide a target WBC count to guide patient management.11,26,27 Updates to these practice guidelines may be warranted. In addition, further study is needed to understand the mechanism of thrombogenesis in PV and other myeloproliferative disorders in order to develop novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Tania Iqbal, PhD, an employee of ICON (North Wales, PA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE).

1. Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595-600. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.813500

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

3. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1874-1881. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.163

4. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R, et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2224-2232. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062

5. Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110(3):840-846. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287

6. Goyal RK, Davis KL, Cote I, Mounedji N, Kaye JA. Increased incidence of thromboembolic event rates in patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera: results from an observational cohort study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2014;124:4840. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.4840.4840

7. Barbui T, Carobbio A, Rumi E, et al. In contemporary patients with polycythemia vera, rates of thrombosis and risk factors delineate a new clinical epidemiology. Blood. 2014;124(19):3021-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-591610 8. Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, et al. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(12):662. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6

9. Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV. Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, and emerging treatment options. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):1965-1976. doi:10.1007/s00277-014-2205-y

10. Hultcrantz M, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM-L, et al. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2995-3001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1925

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in myeloproliferative neoplasms (Version 1.2020). Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

12. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

13. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Barbui T, et al. Leukocytosis as a major thrombotic risk factor in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2007;109(6):2446-2452. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-042515

14. Barbui T, Masciulli A, Marfisi MR, et al. White blood cell counts and thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study. Blood. 2015;126(4):560-561. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-638593

15. Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Treatment target in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1555-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1301262

16. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):63-69. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010

17. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Hematocrit levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2533-2539. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03793-w

18. WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1332-e1345. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3.

19. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

20. Jakafi. Package insert. Incyte Corporation; 2020.

21. Gordeuk VR, Key NS, Prchal JT. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):653-658. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.210732

22. Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117(22):5857-5859. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-339002

23. Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87(6):1954-1959. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1954

24. Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):e87-e90. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.216267

25. Kroll MH, Michaelis LC, Verstovsek S. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in polycythemia vera. Blood Rev. 2015;29(4):215-221. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.002

26. Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057-1069. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1

27. Barosi G, Mesa R, Finazzi G, et al. Revised response criteria for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: an ELN and IWG-MRT consensus project. Blood. 2013;121(23):4778-4781. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-478891

1. Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595-600. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.813500

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

3. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1874-1881. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.163

4. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R, et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2224-2232. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062

5. Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110(3):840-846. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287

6. Goyal RK, Davis KL, Cote I, Mounedji N, Kaye JA. Increased incidence of thromboembolic event rates in patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera: results from an observational cohort study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2014;124:4840. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.4840.4840

7. Barbui T, Carobbio A, Rumi E, et al. In contemporary patients with polycythemia vera, rates of thrombosis and risk factors delineate a new clinical epidemiology. Blood. 2014;124(19):3021-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-591610 8. Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, et al. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(12):662. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6

9. Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV. Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, and emerging treatment options. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):1965-1976. doi:10.1007/s00277-014-2205-y

10. Hultcrantz M, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM-L, et al. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2995-3001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1925

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in myeloproliferative neoplasms (Version 1.2020). Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

12. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

13. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Barbui T, et al. Leukocytosis as a major thrombotic risk factor in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2007;109(6):2446-2452. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-042515

14. Barbui T, Masciulli A, Marfisi MR, et al. White blood cell counts and thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study. Blood. 2015;126(4):560-561. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-638593

15. Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Treatment target in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1555-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1301262

16. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):63-69. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010

17. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Hematocrit levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2533-2539. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03793-w

18. WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1332-e1345. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3.

19. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

20. Jakafi. Package insert. Incyte Corporation; 2020.

21. Gordeuk VR, Key NS, Prchal JT. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):653-658. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.210732

22. Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117(22):5857-5859. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-339002

23. Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87(6):1954-1959. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1954

24. Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):e87-e90. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.216267

25. Kroll MH, Michaelis LC, Verstovsek S. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in polycythemia vera. Blood Rev. 2015;29(4):215-221. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.002

26. Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057-1069. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1

27. Barosi G, Mesa R, Finazzi G, et al. Revised response criteria for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: an ELN and IWG-MRT consensus project. Blood. 2013;121(23):4778-4781. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-478891

2022 Update on gynecologic cancer

Despite the challenges of an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, researchers in 2021 delivered practice-changing studies in gynecologic oncology. In this cancer Update, we highlight 4 studies that shed light on the surgical and systemic therapies that may improve outcomes for patients with cancers of the ovary, endometrium, and cervix. We review DESKTOP III, a trial that investigated the role of cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, and SENTOR, a study that evaluated the performance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with high-grade endometrial cancers. Additionally, we examine 2 studies of systemic therapy that reveal the growing role of targeted therapies and immuno-oncology in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies.

A new era for patients with BRCA mutation–associated ovarian cancer

Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, et al. Maintenance olaparib for patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation (SOLO1/GOG 3004): 5-year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1721-1731.

Ovarian cancer remains the most lethal gynecologic malignancy due to the frequency of advanced-stage diagnosis and frequent relapse after primary therapy. But for ovarian cancer patients with inherited mutations of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, a class of oral anticancer medicines that target DNA repair, have ushered in a new era in which the possibility of long-term remission, and even cure, is more likely than at any other time.

Olaparib trial details

The SOLO1 study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial that investigated the role of PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy with olaparib in patients with pathologic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who responded to platinum-based chemotherapy administered for a newly diagnosed, advanced-stage ovarian cancer.1 The study enrolled 391 patients, with 260 randomly assigned to receive olaparib for 24 months and 131 patients randomly assigned to receive placebo tablets. Most patients in the study had a mutation in the BRCA1 gene (72%), 27% had a BRCA2 mutation, and 1% had mutations in both genes.

The primary analysis of SOLO1 was published in 2018 and was based on a median follow-up of 3.4 years.1 That study showed that olaparib maintenance therapy resulted in a large progression-free survival benefit and led to its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a maintenance therapy for patients with BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

In 2021, Banerjee and colleagues updated the progression-free survival results for the SOLO1 trial after 5 years of follow-up.2 In this study, the patients randomly assigned to olaparib maintenance therapy had a persistent and statistically significant progression-free survival benefit, with the median progression-free survival reaching 56 months among the olaparib group compared with 13.8 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25–0.43).2 Olaparib maintenance therapy resulted in more clinically significant adverse events, including anemia and neutropenia. Serious adverse events occurred in 55 (21%) of the olaparib-treated patients and 17 (13%) of the placebo-treated patients, but no treatment-related adverse events were fatal.

The updated progression-free survival data from the SOLO1 study provides important and promising evidence that frontline PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy may affect long-term remission in an unprecedented proportion of patients with BRCA-related ovarian cancer. Significant, sustained benefit was seen well beyond the end of treatment, and median progression-free survival was an astonishing 3.5 years longer in the olaparib treatment group than among patients who received placebo therapy.

Continue to: Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer improves survival in well-selected patients...

Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer improves survival in well-selected patients

Harter P, Sehouli J, Vergote I, et al; DESKTOP III Investigators. Randomized trial of cytoreductive surgery for relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2123- 2131.

In the DESKTOP III trial, Harter and colleagues contribute results to the ongoing discourse surrounding treatment options for patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.3 Systemic therapies continue to be the mainstay of treatment in this setting; however, several groups have attempted to evaluate the role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in this setting.4,5

Specific inclusion criteria employed

The DESKTOP III investigators randomly assigned 407 patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer to secondary cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy (n = 206) or platinum-based chemotherapy alone (n = 201).3 An essential aspect of the study’s design was the use of specific inclusion criteria known to identify patients with a high likelihood of complete resection at the time of secondary cytoreduction.6,7 Patients were eligible only if they had at least a 6-month remission following platinum-based chemotherapy, had a complete resection at their previous surgery, had no restriction on physical activity, and had ascites of no more than 500 mL.

Surgery group had superior overall and progression-free survival

After a median follow-up of approximately 70 months, patients randomly assigned to surgery had superior overall survival (53.7 months) compared with those assigned to chemotherapy alone (46.0 months; HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.59–0.96).3 Progression-free survival also was improved among patients who underwent surgery (median 18.4 vs 12.7 months; HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.54–0.82). Subgroup analyses did not identify any subset of patients who did not benefit from surgery. Whether a complete resection was achieved at secondary cytoreduction was highly prognostic: Patients who had a complete resection had a median overall survival of 61.9 months compared with 27.7 months in patients with residual disease. There were no deaths within 90 days of surgery.

The DESKTOP III trial provides compelling evidence that secondary cytoreductive surgery improves overall and progression-free survival among well-selected patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. These results differ from those of a recently reported Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trial that failed to detect a survival benefit for secondary cytoreductive surgery among patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.5 Key differences, which might explain the studies’ seemingly contradictory results, were that the GOG study had fewer specific eligibility criteria than the DESKTOP III trial, and that bevacizumab was administered much more frequently in the GOG study. It is therefore reasonable to discuss the possible benefits of secondary cytoreductive surgery with patients who meet DESKTOP III eligibility criteria, with a focus toward shared decision making and a candid discussion of the potential risks and benefits of secondary cytoreduction.

Continue to: Immunotherapy enters first-line treatment regimen for advanced cervical cancer...

Immunotherapy enters first-line treatment regimen for advanced cervical cancer

Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

Persistent, recurrent, and metastatic cervical cancer carries a very poor prognosis: Most patients progress less than a year after starting treatment, and fewer than half survive for 2 years. First-line treatment in this setting has been platinum-based chemotherapy, often given with bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits tumor growth by blocking angiogenesis.8 Pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, targets cancer cells by blocking their ability to evade the immune system, and it is FDA approved and widely administered to patients with advanced cervical cancer who progress after first-line treatment.9

Addition of pembrolizumab extended survival

In the KEYNOTE-826 trial, Colombo and colleagues investigated the efficacy of incorporating an immune checkpoint inhibitor into the first-line treatment regimen for patients with persistent, recurrent, and metastatic cervical cancer.10 Researchers in this double-blinded, phase 3, randomized controlled trial assigned 617 patients to receive pembrolizumab or placebo concurrently with the investigator’s choice platinum-based chemotherapy. Bevacizumab was administered at the discretion of the treating oncologist.

The proportion of patients who survived at least 2 years following randomization was significantly higher among those assigned to pembrolizumab compared with placebo (53% vs 42%; HR, 0.67, 95% CI, 0.54–0.84).10 Similarly, median progression-free survival was superior among patients who received pembrolizumab compared with those who received placebo (10.4 months vs 8.2 months; HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53–0.79). The role of bevacizumab in conjunction with pembrolizumab and platinum-based chemotherapy was not elucidated in this study because bevacizumab administration was not randomly assigned.

Anemia and neutropenia were the most common adverse events and were more frequent in the pembrolizumab group, but there were no new safety concerns related to concurrent use of pembrolizumab with cytotoxic chemotherapy and bevacizumab. Importantly, subgroup analysis results suggested that pembrolizumab was effective only in patients whose tumors expressed PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1), a biomarker of pembrolizumab sensitivity in cervical cancer.

In light of the significant improvements in overall and progression-free survival demonstrated in the KEYNOTE-826 trial, in October 2021, the FDA approved the use of frontline pembrolizumab alongside platinum-based chemotherapy, with or without bevacizumab, for treatment of patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancers that express PD-L1.

Continue to: Endometrial cancer surgical staging...

Endometrial cancer surgical staging: Is sentinel lymph node biopsy a viable option for high-risk histologies?

Cusimano MC, Vicus D, Pulman K, et al. Assessment of sentinel lymph node biopsy vs lymphadenectomy for intermediate- and high-grade endometrial cancer staging. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:157-164.

The use of intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy to identify lymph node metastases among patients undergoing surgical staging for endometrial cancer has become increasingly common. Lymph node status is an important prognostic factor, and it guides adjuvant treatment decisions in endometrial cancer. However, traditional pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is associated with increased risk of lower-extremity lymphedema, postoperative complications, and intraoperative injury.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy seeks to identify lymph node metastases while minimizing surgical morbidity by identifying and excising only lymph nodes that directly receive lymphatic drainage from the uterus. The combination of a fluorescent dye (indocyanine green) and near infrared cameras have led to the broad adoption of sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer staging surgery. This practice is supported by prospective studies that demonstrate the high diagnostic accuracy of this approach.11,12 However, because most patients included in prior studies had low-grade endometrial cancer, the utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy in cases of high-grade histology has been less clear.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy vs lymphadenectomy for staging

In the SENTOR trial, Cusimano and colleagues examined the diagnostic accuracy of sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy, using indocyanine green, in patients with intermediate- or high-grade early-stage endometrial cancer.13

All eligible patients (N = 156) underwent traditional or robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Subsequently, patients with grade 2 endometrioid carcinoma underwent bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy, and those with high-grade histology (grade 3 endometrioid, serous, carcinosarcoma, clear cell, undifferentiated or dedifferentiated, and mixed high grade) underwent bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. The investigators evaluated the diagnostic characteristics of sentinel lymph node biopsy, treating complete lymphadenectomy as the gold standard.

Of the 156 patients enrolled, the median age was 65.5 and median body mass index was 27.5; 126 patients (81%) had high-grade histology. The sentinel lymph node biopsy had a sensitivity of 96% (95% CI, 81%–100%), identifying 26 of the 27 patients with nodal metastases. The false-negative rate was 4% (95% CI, 0%–9%) and the negative predictive value was 99% (95% CI, 96%–100%). Intraoperative adverse events occurred in 5 patients (3%), but none occurred during the sentinel lymph node biopsy. ●

The high sensitivity and negative predictive value of sentinel lymph node biopsy in the intermediate- and high-grade cohort included in the SENTOR trial are concordant with prior studies that predominantly included patients with low-grade endometrial cancer. These findings suggest that sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy is a reasonable option for surgical staging, not only for patients with low-grade endometrial cancer but also for those with intermediate- and high-grade disease.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

- Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, et al. Maintenance olaparib for patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation (SOLO1/GOG 3004): 5-year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1721-1731.

- Harter P, Sehouli J, Vergote I, et al; DESKTOP III Investigators. Randomized trial of cytoreductive surgery for relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2123-2131.

- Shi T, Zhu J, Feng Y, et al. Secondary cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer (SOC-1): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:439-449.

- Coleman RL, Spiritos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

- Harter P, du Bois A, Hahmann M, et al; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Committee; AGO Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) DESKTOP OVAR trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702-1710.

- Harter P, Sehouli J, Reuss A, et al. Prospective validation study of a predictive score for operability of recurrent ovarian cancer: the Multicenter Intergroup Study DESKTOP II. A project of the AGO Kommission OVAR, AGO Study Group, NOGGO, AGO-Austria, and MITO. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21: 289-295.

- Tewari KS, Sill MW, Penson RT, et al. Bevacizumab for advanced cervical cancer: final overall survival and adverse event analysis of a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial (Gynecologic Oncology Group 240). Lancet. 2017;390:1654-1663.

- Frenel JS, Le Tourneau C, O’Neil B, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab in advanced, programmed death ligand 1-positive cervical cancer: results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:4035-4041.

- Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

- Rossi EC, Kowalski L, Scalici J, et al. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:384-392.

- Ballester M, Dubernard G, Lecuru F, et al. Detection rate and diagnostic accuracy of sentinel-node biopsy in early stage endometrial cancer: a prospective multicentre study (SENTIENDO). Lancet Oncol. 2011;12: 469-476.

- Cusimano MC, Vicus D, Pulman K, et al. Assessment of sentinel lymph node biopsy vs lymphadenectomy for intermediate- and high-grade endometrial cancer staging. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:157-164.

Despite the challenges of an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, researchers in 2021 delivered practice-changing studies in gynecologic oncology. In this cancer Update, we highlight 4 studies that shed light on the surgical and systemic therapies that may improve outcomes for patients with cancers of the ovary, endometrium, and cervix. We review DESKTOP III, a trial that investigated the role of cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, and SENTOR, a study that evaluated the performance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with high-grade endometrial cancers. Additionally, we examine 2 studies of systemic therapy that reveal the growing role of targeted therapies and immuno-oncology in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies.

A new era for patients with BRCA mutation–associated ovarian cancer

Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, et al. Maintenance olaparib for patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation (SOLO1/GOG 3004): 5-year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1721-1731.

Ovarian cancer remains the most lethal gynecologic malignancy due to the frequency of advanced-stage diagnosis and frequent relapse after primary therapy. But for ovarian cancer patients with inherited mutations of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, a class of oral anticancer medicines that target DNA repair, have ushered in a new era in which the possibility of long-term remission, and even cure, is more likely than at any other time.

Olaparib trial details

The SOLO1 study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial that investigated the role of PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy with olaparib in patients with pathologic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who responded to platinum-based chemotherapy administered for a newly diagnosed, advanced-stage ovarian cancer.1 The study enrolled 391 patients, with 260 randomly assigned to receive olaparib for 24 months and 131 patients randomly assigned to receive placebo tablets. Most patients in the study had a mutation in the BRCA1 gene (72%), 27% had a BRCA2 mutation, and 1% had mutations in both genes.

The primary analysis of SOLO1 was published in 2018 and was based on a median follow-up of 3.4 years.1 That study showed that olaparib maintenance therapy resulted in a large progression-free survival benefit and led to its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a maintenance therapy for patients with BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

In 2021, Banerjee and colleagues updated the progression-free survival results for the SOLO1 trial after 5 years of follow-up.2 In this study, the patients randomly assigned to olaparib maintenance therapy had a persistent and statistically significant progression-free survival benefit, with the median progression-free survival reaching 56 months among the olaparib group compared with 13.8 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25–0.43).2 Olaparib maintenance therapy resulted in more clinically significant adverse events, including anemia and neutropenia. Serious adverse events occurred in 55 (21%) of the olaparib-treated patients and 17 (13%) of the placebo-treated patients, but no treatment-related adverse events were fatal.

The updated progression-free survival data from the SOLO1 study provides important and promising evidence that frontline PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy may affect long-term remission in an unprecedented proportion of patients with BRCA-related ovarian cancer. Significant, sustained benefit was seen well beyond the end of treatment, and median progression-free survival was an astonishing 3.5 years longer in the olaparib treatment group than among patients who received placebo therapy.

Continue to: Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer improves survival in well-selected patients...

Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer improves survival in well-selected patients

Harter P, Sehouli J, Vergote I, et al; DESKTOP III Investigators. Randomized trial of cytoreductive surgery for relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2123- 2131.

In the DESKTOP III trial, Harter and colleagues contribute results to the ongoing discourse surrounding treatment options for patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.3 Systemic therapies continue to be the mainstay of treatment in this setting; however, several groups have attempted to evaluate the role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in this setting.4,5

Specific inclusion criteria employed

The DESKTOP III investigators randomly assigned 407 patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer to secondary cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy (n = 206) or platinum-based chemotherapy alone (n = 201).3 An essential aspect of the study’s design was the use of specific inclusion criteria known to identify patients with a high likelihood of complete resection at the time of secondary cytoreduction.6,7 Patients were eligible only if they had at least a 6-month remission following platinum-based chemotherapy, had a complete resection at their previous surgery, had no restriction on physical activity, and had ascites of no more than 500 mL.

Surgery group had superior overall and progression-free survival

After a median follow-up of approximately 70 months, patients randomly assigned to surgery had superior overall survival (53.7 months) compared with those assigned to chemotherapy alone (46.0 months; HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.59–0.96).3 Progression-free survival also was improved among patients who underwent surgery (median 18.4 vs 12.7 months; HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.54–0.82). Subgroup analyses did not identify any subset of patients who did not benefit from surgery. Whether a complete resection was achieved at secondary cytoreduction was highly prognostic: Patients who had a complete resection had a median overall survival of 61.9 months compared with 27.7 months in patients with residual disease. There were no deaths within 90 days of surgery.

The DESKTOP III trial provides compelling evidence that secondary cytoreductive surgery improves overall and progression-free survival among well-selected patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. These results differ from those of a recently reported Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trial that failed to detect a survival benefit for secondary cytoreductive surgery among patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.5 Key differences, which might explain the studies’ seemingly contradictory results, were that the GOG study had fewer specific eligibility criteria than the DESKTOP III trial, and that bevacizumab was administered much more frequently in the GOG study. It is therefore reasonable to discuss the possible benefits of secondary cytoreductive surgery with patients who meet DESKTOP III eligibility criteria, with a focus toward shared decision making and a candid discussion of the potential risks and benefits of secondary cytoreduction.

Continue to: Immunotherapy enters first-line treatment regimen for advanced cervical cancer...

Immunotherapy enters first-line treatment regimen for advanced cervical cancer

Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

Persistent, recurrent, and metastatic cervical cancer carries a very poor prognosis: Most patients progress less than a year after starting treatment, and fewer than half survive for 2 years. First-line treatment in this setting has been platinum-based chemotherapy, often given with bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits tumor growth by blocking angiogenesis.8 Pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, targets cancer cells by blocking their ability to evade the immune system, and it is FDA approved and widely administered to patients with advanced cervical cancer who progress after first-line treatment.9

Addition of pembrolizumab extended survival

In the KEYNOTE-826 trial, Colombo and colleagues investigated the efficacy of incorporating an immune checkpoint inhibitor into the first-line treatment regimen for patients with persistent, recurrent, and metastatic cervical cancer.10 Researchers in this double-blinded, phase 3, randomized controlled trial assigned 617 patients to receive pembrolizumab or placebo concurrently with the investigator’s choice platinum-based chemotherapy. Bevacizumab was administered at the discretion of the treating oncologist.

The proportion of patients who survived at least 2 years following randomization was significantly higher among those assigned to pembrolizumab compared with placebo (53% vs 42%; HR, 0.67, 95% CI, 0.54–0.84).10 Similarly, median progression-free survival was superior among patients who received pembrolizumab compared with those who received placebo (10.4 months vs 8.2 months; HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53–0.79). The role of bevacizumab in conjunction with pembrolizumab and platinum-based chemotherapy was not elucidated in this study because bevacizumab administration was not randomly assigned.

Anemia and neutropenia were the most common adverse events and were more frequent in the pembrolizumab group, but there were no new safety concerns related to concurrent use of pembrolizumab with cytotoxic chemotherapy and bevacizumab. Importantly, subgroup analysis results suggested that pembrolizumab was effective only in patients whose tumors expressed PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1), a biomarker of pembrolizumab sensitivity in cervical cancer.

In light of the significant improvements in overall and progression-free survival demonstrated in the KEYNOTE-826 trial, in October 2021, the FDA approved the use of frontline pembrolizumab alongside platinum-based chemotherapy, with or without bevacizumab, for treatment of patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancers that express PD-L1.

Continue to: Endometrial cancer surgical staging...

Endometrial cancer surgical staging: Is sentinel lymph node biopsy a viable option for high-risk histologies?

Cusimano MC, Vicus D, Pulman K, et al. Assessment of sentinel lymph node biopsy vs lymphadenectomy for intermediate- and high-grade endometrial cancer staging. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:157-164.

The use of intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy to identify lymph node metastases among patients undergoing surgical staging for endometrial cancer has become increasingly common. Lymph node status is an important prognostic factor, and it guides adjuvant treatment decisions in endometrial cancer. However, traditional pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is associated with increased risk of lower-extremity lymphedema, postoperative complications, and intraoperative injury.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy seeks to identify lymph node metastases while minimizing surgical morbidity by identifying and excising only lymph nodes that directly receive lymphatic drainage from the uterus. The combination of a fluorescent dye (indocyanine green) and near infrared cameras have led to the broad adoption of sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer staging surgery. This practice is supported by prospective studies that demonstrate the high diagnostic accuracy of this approach.11,12 However, because most patients included in prior studies had low-grade endometrial cancer, the utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy in cases of high-grade histology has been less clear.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy vs lymphadenectomy for staging