User login

How to manage hypothyroid disease in pregnancy

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A pregnant woman whose thyroid gland isn’t doing its job presents a serious management problem for her obstetrician. If she has overt hypothyroidism, seen in between 0.3% and 2.5% of pregnancies, active intervention is required to prevent serious damage to the fetus.1,2 Even if she has subclinical disease, seen in 2% to 3% of pregnancies, current research indicates that intervention may be indicated.

Fetal thyroxine requirements increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation, when the fetus is still dependent on maternal thyroxine. A deficiency of maternal thyroxine can have severe adverse outcomes, affecting the course of the pregnancy and the neurologic development of the fetus. To prevent such sequelae, patients who were on thyroid medication before pregnancy should increase the dosage by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed, and hypothyroidism that develops in pregnancy should be managed aggressively and meticulously.

Here, we’ll examine the published research to advise you on evidence-based approaches for diagnosis and management of this complex condition.

Maternal thyroid function

An elaborate negative-feedback loop prevails before pregnancy

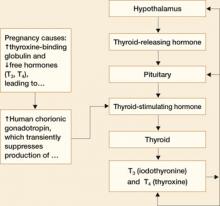

In a nonpregnant woman, thyroid function is controlled by a negative-feedback loop that works like this:

- The hypothalamus releases thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH)

- TRH acts on the pituitary gland to release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- TSH, in turn, acts on the thyroid gland to release the thyroid hormones iodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) that regulate metabolism

- TRH and TSH concentrations are inversely related to T3 and T4 concentrations. That is, the more TRH and TSH circulating in the blood stream, the less T3 and T4 will be produced by the thyroid gland3

- Almost all (approximately 99%) circulating T3 and T4 is bound to a protein called thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). Only 1% of these hormones circulate in the free form, and only the free forms are biologically active.3

This relationship is illustrated in FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1 Thyroid physiology and the impact of pregnancy

Pregnancy reduces free forms of T3 and T4, and increases TSH slightly

Pregnancy alters thyroid function in significant ways:

- Increases in circulating estrogen lead to the production of more TBG

- When TBG increases, more T3 and T4 are bound and fewer free forms of these hormones are available

- Because the total T3 (TT3) and total free T4 (TT4) are decreased in pregnancy, they are not good measures of thyroid function. Maternal thyroid function in pregnancy should be monitored using free T4 (FT4) and TSH levels

- Increased TBG also leads to a slight increase in TSH between the first trimester and term

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations also increase in pregnancy. Because hCG has thyrotropin-like activity, these higher levels cause a transient decrease in TSH by suppression of TSH production between approximately 8 and 14 weeks of gestation.

Fetal thyroid function

During early gestation, the fetus receives thyroid hormone from the mother.1 Maternal T4 crosses the placenta actively—the only hormone that does so.4 The fetus’s need for thyroxine starts to increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation.5

Fetal thyroid development does not begin until 10 to 12 weeks of gestation, and then continues until term. The fetus relies on maternal T4 exclusively before 12 weeks and partially thereafter for normal fetal neurologic development. It follows that maternal hypothyroidism could be detrimental to fetal development if not detected and corrected very early in gestation.

How (and whom) to screen for maternal hypothyroidism

Routine screening has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of deficient thyroid function.6 In recent years, some authors have recommended screening all pregnant women for thyroid dysfunction, but such recommendations remain controversial.3,7,8 Routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.6

Symptoms overlap typical conditions of pregnancy

The difficulty here is that the characteristic signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism are very similar to physiologic conditions seen in most pregnancies. They include fatigue, constipation, cold intolerance, muscle cramps, hair loss, dry skin, brittle nails, weight gain, intellectual slowness, bradycardia, depression, insomnia, periorbital edema, myxedema, and myxedema coma.6 A side-by-side comparison of pregnancy conditions and hypothyroidism symptoms is provided in TABLE 1.

TABLE 1

Distinguishing hypothyroidism from a normal gestation can be challenging

| SYMPTOM | HYPOTHYROIDISM | PREGNANCY |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | • | • |

| Constipation | • | • |

| Hair loss | • | |

| Dry skin | • | |

| Brittle nails | • | |

| Weight gain | • | • |

| Fluid retention | • | • |

| Bradycardia | • | • |

| Goiter | • | |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | • | • |

Which laboratory tests are informative?

Because screening is controversial and symptomatology does not reliably distinguish hypothyroidism from normal pregnancy, laboratory tests are the standard for diagnosis. Overt hypothyroidism is diagnosed in a symptomatic patient by elevated TSH level and low levels of FT4 and free T3 (FT3). Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as elevated TSH with normal FT4 and FT3 in an asymptomatic patient. Level changes characteristic of normal pregnancy, overt hypothyroidism, and subclinical hypothyroidism are given in TABLE 2.6

TABLE 2

Laboratory diagnosis of hypothyroidism

| MATERNAL CONDITION | TSH | FREE T3 | FREE T4 | TOTAL T3 | TOTAL T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal pregnancy | No change | No change | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Hypothyroidism | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | ↑ | No change | No change | ↓ | ↓ |

| Adapted from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 | |||||

What causes hypothyroidism?

The most common cause of hypothyroidism in most of the world is iodine deficiency. In developed countries, however, where lack of iodine in the diet is not a problem, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, is the most common cause. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is characterized by the presence of antithyroid antibodies, including both thyroid antimicrosomial and antithyroglobulin antibodies. Both iodine deficiency and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are associated with goiter.5 Other causes of hypothyroidism include radioactive iodine therapy for Graves’ disease, a condition we will discuss in Part 2 of this series in February; thyroidectomy; viral thyroiditis; pituitary tumors; Sheehan’s syndrome; and a number of medications.

Causes of hypothyroidism are summarized in TABLE 3.3

TABLE 3

Causes of hypothyroidism

| Iodine deficiency |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

| Radioactive iodine therapy |

| Thyroidectomy |

| Viral thyroiditis |

| Sheehan’s syndrome |

Medications

|

Effects vary by medication

Medications alter thyroid function in different ways. Iodine and lithium inhibit thyroid function and, along with dopamine antagonists, increase TSH levels. Conversely, thioamides, glucocorticoids, dopamine agonists, and somatostatins decrease TSH levels. Finally, ferrous sulfate, sucrafate, cholestyramine, and aluminum hydroxide antacids all inhibit gastrointestinal absorption of thyroid hormone and therefore should not be taken within 4 hours of thyroid medication.6

Maternal hypothyroidism: Effects on fetus, newborn

The impact of maternal hypothyroidism on the fetus depends on the severity of the condition.

- Uncontrolled hypothyroidism. The consequences of this condition can be dire. The possibilities include intrauterine fetal demise and stillbirth, preterm delivery, low birth weight, preeclampsia, and developmental anomalies including reduced intelligence quotient (IQ).1,2,4,6 Blazer and colleagues correlated intrauterine growth with maternal TSH and fetal FT4 and concluded that impaired intrauterine growth is related to abnormal thyroid function and might reflect an insufficient level of hormone production by hypothyroid mothers during pregnancy.9 Maternal and congenital hypothyroidism resulting from severe iodine deficiency are associated with profound neurologic impairment and mental retardation.1,3,10 If the condition is left untreated, cretinism can occur. Congenital cretinism is associated with growth failure, mental retardation, and other neuropsychologic deficits including deaf-mutism.3,4 However, if cretinism is identified and treated in the first 3 months of life, near-normal growth and intelligence can be expected.6 For this reason, all 50 states and the District of Columbia require newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism.6

- Asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism. Several studies have evaluated neonatal outcomes in pregnancy complicated by asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism—that is, women who had previously been diagnosed with hypothyroidism, who have abnormal TSH and FT4 levels, but who do not have symptoms. Pop and colleagues have shown impaired psychomotor development at 10 months in infants born to mothers who had low T4 during the first 12 weeks of gestation.7 Haddow and colleagues correlated elevated maternal TSH levels at less than 17 weeks’ gestation with low IQ scores in the offspring at 7 to 9 years of age.8 Klein and colleagues demonstrated an inverse correlation between a woman’s TSH level during pregnancy and the IQ of her offspring.11 Kooistra and colleagues confirmed that maternal hypothyroxinemia is a risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities that can be identified as early as 3 weeks of age.12 Studies of this relationship are summarized in TABLE 4.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism. During the past decade, researchers have focused attention on neonatal neurologic function in infants born to mothers who had subclinical disease. Mitchell and Klein evaluated the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism at less than 17 weeks’ gestation and subsequently compared the IQs in these children with those of controls.4 They found the mean and standard-deviation IQs of the children in the control and treated groups to be significantly higher than those of the children whose mothers were not treated. Casey and colleagues evaluated pregnancy outcomes in women who had undiagnosed subclinical hypothyroidism.10 They found that such pregnancies were more likely to be complicated by placental abruption and preterm birth, and speculated that the reduced IQ demonstrated in the Mitchell and Klein study might have been related to the effects of prematurity.

TABLE 4

Fetal and neonatal effects of asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism

| STUDY | LABORATORY FINDINGS | OUTCOMES AND RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Kooistra et al12 | ↓ FT4 | Maternal hypothyroxinemia is a risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities as early as 3 weeks of age |

| Casey et al10 | ↑ TSH | Pregnancies with undiagnosed subclinical hypothyroidism were more likely to be complicated by placental abruption and preterm birth. The reduced IQ seen in a prior study (Mitchell and Klein4) may be related to effects of prematurity |

| Mitchell and Klein4 | ↑ TSH | The mean and standard deviation of IQs of the children of treated mothers with hypothyroidism and the control group were significantly higher than those for children of untreated hypothyroid women |

| Blazer et al9 | ↑ maternal TSH, ↑ fetal FT4 | Impaired intrauterine growth may reflect insufficient levels of hormone replacement therapy in hypothyroid mothers during pregnancy |

| Pop et al7 | ↓ FT4 | Impaired psychomotor development at 10 months of age in offspring of mothers with low T4 at ≤12 weeks |

| Haddow et al8 | ↑ TSH, ↓ FT4 | Elevated TSH levels at <17 weeks’ gestation are associated with low IQ scores at 7 to 9 years of age. Routine screening for thyroid deficiency may be warranted |

| Klein et al11 | ↑ TSH, ↓ FT4, ↓ TT4 | Inverse correlation between TSH during pregnancy and IQ of offspring |

| FT4=free thyroxine, TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone, TT4=total thyroxine | ||

Managing hypothyroidism in pregnancy

The treatment of choice for correction of hypothyroidism is synthetic T4, or levothyroxine (Levothyroid, Levoxyl, Synthroid, and Unithroid). Initial treatment in the nonpregnant patient is 1.7 μg/kg/day or 12.5 to 25 μg/day adjusted by 25 μg/day every 2 to 4 weeks until a euthyroid state is achieved.13

Patients who were on thyroxine therapy before pregnancy should increase the dose by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed.1,5 Serum thyrotropin levels should be monitored every 4 weeks to maintain a TSH level between 1 and 2 mU/L and FT4 in upper third of normal.1 Once a euthyroid state has been achieved, thyrotropin levels should be monitored every trimester until delivery. FIGURE 2 provides an algorithm for management of hypothyroidism in pregnancy.

FIGURE 2 During pregnancy, thyroid function merits regular monitoring, fine-tuning of treatment

Postpartum thyroiditis

About 5% of all obstetrical patients develop postpartum thyroiditis. Approximately 45% of these women present with hypothyroidism, with the rest evenly divided between thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism) and thyrotoxicosis followed by hypothyroidism. Unfortunately, the signs and symptoms of hypo- and hyperthyroidism are similar to the postpartum state. Many of these patients are not diagnosed. A high index of suspicion warrants thyroid function testing. Women who have a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus have a 25% chance of developing postpartum thyroid dysfunction.

The diagnosis is made by documenting abnormal levels of TSH and FT4. Postpartum hyperthyroidism may be diagnosed by the presence of antimicrosomal or thyroperoxidase antithyroid peroxidase antibodies. Goiter may be present in up to 50% of patients.

Postpartum thyroiditis has two phases

The first phase, also known as the thyrotoxic phase, occurs 1 to 4 months after delivery when transient thyrotoxicosis develops from excessive release of thyroid hormones. The most common symptoms with early postpartum thyroiditis are fatigue and palpitations. Approximately 67% of these women will return to a euthyroid state, and thioamide therapy is generally considered ineffective. Hypothyroidism can develop within 1 month of the onset of thyroiditis.

The second phase occurs between 4 and 8 months postpartum, and these women present with hypothyroidism. Thyromegaly and associated symptoms are common. Unlike the first (thyrotoxic) phase, medical treatment is recommended. Thyroxine treatment should be initiated and maintained for 6 to 12 months. Postpartum thyroiditis carries a 30% risk of recurrence.14

Postpartum thyroiditis may be associated with depression or aggravate symptoms of depression, although the data on this association are conflicting. The largest study addressing this issue concluded that there was no difference in the clinical and psychiatric signs and symptoms between postpartum thyroiditis and controls.15 Nevertheless, it would seem prudent to evaluate thyroid function in postpartum depression if other signs of thyroid dysfunction are present.

1. Idris I, Srinivasan R, Simm A, Page RC. Effects of maternal hyperthyroidism during early gestation on neonatal and obstetric outcome. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;65:133-135.

2. Girling JC. Thyroid disorders in pregnancy. Curr Obstet Gynecol. 2006;16:47-53.

3. Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams J. Maternal–Fetal Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2004:1063-1082.

4. Mitchell ML, Klein RZ. The sequelae of untreated maternal hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 Suppl 3:U45-U48.

5. Alexander EK, Marqusee E, Lawrence J, Jarolim P, Fischer GA, Larsen PR. Timing and magnitude of increases in levothyroxine requirements during pregnancy in women with hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:241-249.

6. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 32, November 2001). Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:387-396.

7. Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:149-155.

8. Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:549-555.

9. Blazer S, Moreh-Waterman Y, Miller-Lotan R, Tamir A, Hochberg Z. Maternal hypothyroidism may affect fetal growth and neonatal thyroid function. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:232-241.

10. Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:239-245.

11. Klein RZ, Haddow JE, Faix JD, et al. Prevalence of thyroid deficiency in pregnant women. Clin Endocrinol. 1991;35:41-46.

12. Kooistra L, Crawford S, van Baar AL, Brouwers EP, Pop VJ. Neonatal effects of maternal hypothyroxinemia during early pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2006;117:161-167.

13. Levothyroxine: Drug information. Lexicomp. http://www.utdol.com/utd/content/topic.do?topicKey=drug_l_z/143814&type=A&selectedTitle=2~39. Accessed December 14, 2007.

14. Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1283-1292.

15. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;51:429-438.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A pregnant woman whose thyroid gland isn’t doing its job presents a serious management problem for her obstetrician. If she has overt hypothyroidism, seen in between 0.3% and 2.5% of pregnancies, active intervention is required to prevent serious damage to the fetus.1,2 Even if she has subclinical disease, seen in 2% to 3% of pregnancies, current research indicates that intervention may be indicated.

Fetal thyroxine requirements increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation, when the fetus is still dependent on maternal thyroxine. A deficiency of maternal thyroxine can have severe adverse outcomes, affecting the course of the pregnancy and the neurologic development of the fetus. To prevent such sequelae, patients who were on thyroid medication before pregnancy should increase the dosage by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed, and hypothyroidism that develops in pregnancy should be managed aggressively and meticulously.

Here, we’ll examine the published research to advise you on evidence-based approaches for diagnosis and management of this complex condition.

Maternal thyroid function

An elaborate negative-feedback loop prevails before pregnancy

In a nonpregnant woman, thyroid function is controlled by a negative-feedback loop that works like this:

- The hypothalamus releases thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH)

- TRH acts on the pituitary gland to release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- TSH, in turn, acts on the thyroid gland to release the thyroid hormones iodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) that regulate metabolism

- TRH and TSH concentrations are inversely related to T3 and T4 concentrations. That is, the more TRH and TSH circulating in the blood stream, the less T3 and T4 will be produced by the thyroid gland3

- Almost all (approximately 99%) circulating T3 and T4 is bound to a protein called thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). Only 1% of these hormones circulate in the free form, and only the free forms are biologically active.3

This relationship is illustrated in FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1 Thyroid physiology and the impact of pregnancy

Pregnancy reduces free forms of T3 and T4, and increases TSH slightly

Pregnancy alters thyroid function in significant ways:

- Increases in circulating estrogen lead to the production of more TBG

- When TBG increases, more T3 and T4 are bound and fewer free forms of these hormones are available

- Because the total T3 (TT3) and total free T4 (TT4) are decreased in pregnancy, they are not good measures of thyroid function. Maternal thyroid function in pregnancy should be monitored using free T4 (FT4) and TSH levels

- Increased TBG also leads to a slight increase in TSH between the first trimester and term

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations also increase in pregnancy. Because hCG has thyrotropin-like activity, these higher levels cause a transient decrease in TSH by suppression of TSH production between approximately 8 and 14 weeks of gestation.

Fetal thyroid function

During early gestation, the fetus receives thyroid hormone from the mother.1 Maternal T4 crosses the placenta actively—the only hormone that does so.4 The fetus’s need for thyroxine starts to increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation.5

Fetal thyroid development does not begin until 10 to 12 weeks of gestation, and then continues until term. The fetus relies on maternal T4 exclusively before 12 weeks and partially thereafter for normal fetal neurologic development. It follows that maternal hypothyroidism could be detrimental to fetal development if not detected and corrected very early in gestation.

How (and whom) to screen for maternal hypothyroidism

Routine screening has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of deficient thyroid function.6 In recent years, some authors have recommended screening all pregnant women for thyroid dysfunction, but such recommendations remain controversial.3,7,8 Routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.6

Symptoms overlap typical conditions of pregnancy

The difficulty here is that the characteristic signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism are very similar to physiologic conditions seen in most pregnancies. They include fatigue, constipation, cold intolerance, muscle cramps, hair loss, dry skin, brittle nails, weight gain, intellectual slowness, bradycardia, depression, insomnia, periorbital edema, myxedema, and myxedema coma.6 A side-by-side comparison of pregnancy conditions and hypothyroidism symptoms is provided in TABLE 1.

TABLE 1

Distinguishing hypothyroidism from a normal gestation can be challenging

| SYMPTOM | HYPOTHYROIDISM | PREGNANCY |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | • | • |

| Constipation | • | • |

| Hair loss | • | |

| Dry skin | • | |

| Brittle nails | • | |

| Weight gain | • | • |

| Fluid retention | • | • |

| Bradycardia | • | • |

| Goiter | • | |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | • | • |

Which laboratory tests are informative?

Because screening is controversial and symptomatology does not reliably distinguish hypothyroidism from normal pregnancy, laboratory tests are the standard for diagnosis. Overt hypothyroidism is diagnosed in a symptomatic patient by elevated TSH level and low levels of FT4 and free T3 (FT3). Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as elevated TSH with normal FT4 and FT3 in an asymptomatic patient. Level changes characteristic of normal pregnancy, overt hypothyroidism, and subclinical hypothyroidism are given in TABLE 2.6

TABLE 2

Laboratory diagnosis of hypothyroidism

| MATERNAL CONDITION | TSH | FREE T3 | FREE T4 | TOTAL T3 | TOTAL T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal pregnancy | No change | No change | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Hypothyroidism | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | ↑ | No change | No change | ↓ | ↓ |

| Adapted from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 | |||||

What causes hypothyroidism?

The most common cause of hypothyroidism in most of the world is iodine deficiency. In developed countries, however, where lack of iodine in the diet is not a problem, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, is the most common cause. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is characterized by the presence of antithyroid antibodies, including both thyroid antimicrosomial and antithyroglobulin antibodies. Both iodine deficiency and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are associated with goiter.5 Other causes of hypothyroidism include radioactive iodine therapy for Graves’ disease, a condition we will discuss in Part 2 of this series in February; thyroidectomy; viral thyroiditis; pituitary tumors; Sheehan’s syndrome; and a number of medications.

Causes of hypothyroidism are summarized in TABLE 3.3

TABLE 3

Causes of hypothyroidism

| Iodine deficiency |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

| Radioactive iodine therapy |

| Thyroidectomy |

| Viral thyroiditis |

| Sheehan’s syndrome |

Medications

|

Effects vary by medication

Medications alter thyroid function in different ways. Iodine and lithium inhibit thyroid function and, along with dopamine antagonists, increase TSH levels. Conversely, thioamides, glucocorticoids, dopamine agonists, and somatostatins decrease TSH levels. Finally, ferrous sulfate, sucrafate, cholestyramine, and aluminum hydroxide antacids all inhibit gastrointestinal absorption of thyroid hormone and therefore should not be taken within 4 hours of thyroid medication.6

Maternal hypothyroidism: Effects on fetus, newborn

The impact of maternal hypothyroidism on the fetus depends on the severity of the condition.

- Uncontrolled hypothyroidism. The consequences of this condition can be dire. The possibilities include intrauterine fetal demise and stillbirth, preterm delivery, low birth weight, preeclampsia, and developmental anomalies including reduced intelligence quotient (IQ).1,2,4,6 Blazer and colleagues correlated intrauterine growth with maternal TSH and fetal FT4 and concluded that impaired intrauterine growth is related to abnormal thyroid function and might reflect an insufficient level of hormone production by hypothyroid mothers during pregnancy.9 Maternal and congenital hypothyroidism resulting from severe iodine deficiency are associated with profound neurologic impairment and mental retardation.1,3,10 If the condition is left untreated, cretinism can occur. Congenital cretinism is associated with growth failure, mental retardation, and other neuropsychologic deficits including deaf-mutism.3,4 However, if cretinism is identified and treated in the first 3 months of life, near-normal growth and intelligence can be expected.6 For this reason, all 50 states and the District of Columbia require newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism.6

- Asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism. Several studies have evaluated neonatal outcomes in pregnancy complicated by asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism—that is, women who had previously been diagnosed with hypothyroidism, who have abnormal TSH and FT4 levels, but who do not have symptoms. Pop and colleagues have shown impaired psychomotor development at 10 months in infants born to mothers who had low T4 during the first 12 weeks of gestation.7 Haddow and colleagues correlated elevated maternal TSH levels at less than 17 weeks’ gestation with low IQ scores in the offspring at 7 to 9 years of age.8 Klein and colleagues demonstrated an inverse correlation between a woman’s TSH level during pregnancy and the IQ of her offspring.11 Kooistra and colleagues confirmed that maternal hypothyroxinemia is a risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities that can be identified as early as 3 weeks of age.12 Studies of this relationship are summarized in TABLE 4.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism. During the past decade, researchers have focused attention on neonatal neurologic function in infants born to mothers who had subclinical disease. Mitchell and Klein evaluated the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism at less than 17 weeks’ gestation and subsequently compared the IQs in these children with those of controls.4 They found the mean and standard-deviation IQs of the children in the control and treated groups to be significantly higher than those of the children whose mothers were not treated. Casey and colleagues evaluated pregnancy outcomes in women who had undiagnosed subclinical hypothyroidism.10 They found that such pregnancies were more likely to be complicated by placental abruption and preterm birth, and speculated that the reduced IQ demonstrated in the Mitchell and Klein study might have been related to the effects of prematurity.

TABLE 4

Fetal and neonatal effects of asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism

| STUDY | LABORATORY FINDINGS | OUTCOMES AND RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Kooistra et al12 | ↓ FT4 | Maternal hypothyroxinemia is a risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities as early as 3 weeks of age |

| Casey et al10 | ↑ TSH | Pregnancies with undiagnosed subclinical hypothyroidism were more likely to be complicated by placental abruption and preterm birth. The reduced IQ seen in a prior study (Mitchell and Klein4) may be related to effects of prematurity |

| Mitchell and Klein4 | ↑ TSH | The mean and standard deviation of IQs of the children of treated mothers with hypothyroidism and the control group were significantly higher than those for children of untreated hypothyroid women |

| Blazer et al9 | ↑ maternal TSH, ↑ fetal FT4 | Impaired intrauterine growth may reflect insufficient levels of hormone replacement therapy in hypothyroid mothers during pregnancy |

| Pop et al7 | ↓ FT4 | Impaired psychomotor development at 10 months of age in offspring of mothers with low T4 at ≤12 weeks |

| Haddow et al8 | ↑ TSH, ↓ FT4 | Elevated TSH levels at <17 weeks’ gestation are associated with low IQ scores at 7 to 9 years of age. Routine screening for thyroid deficiency may be warranted |

| Klein et al11 | ↑ TSH, ↓ FT4, ↓ TT4 | Inverse correlation between TSH during pregnancy and IQ of offspring |

| FT4=free thyroxine, TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone, TT4=total thyroxine | ||

Managing hypothyroidism in pregnancy

The treatment of choice for correction of hypothyroidism is synthetic T4, or levothyroxine (Levothyroid, Levoxyl, Synthroid, and Unithroid). Initial treatment in the nonpregnant patient is 1.7 μg/kg/day or 12.5 to 25 μg/day adjusted by 25 μg/day every 2 to 4 weeks until a euthyroid state is achieved.13

Patients who were on thyroxine therapy before pregnancy should increase the dose by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed.1,5 Serum thyrotropin levels should be monitored every 4 weeks to maintain a TSH level between 1 and 2 mU/L and FT4 in upper third of normal.1 Once a euthyroid state has been achieved, thyrotropin levels should be monitored every trimester until delivery. FIGURE 2 provides an algorithm for management of hypothyroidism in pregnancy.

FIGURE 2 During pregnancy, thyroid function merits regular monitoring, fine-tuning of treatment

Postpartum thyroiditis

About 5% of all obstetrical patients develop postpartum thyroiditis. Approximately 45% of these women present with hypothyroidism, with the rest evenly divided between thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism) and thyrotoxicosis followed by hypothyroidism. Unfortunately, the signs and symptoms of hypo- and hyperthyroidism are similar to the postpartum state. Many of these patients are not diagnosed. A high index of suspicion warrants thyroid function testing. Women who have a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus have a 25% chance of developing postpartum thyroid dysfunction.

The diagnosis is made by documenting abnormal levels of TSH and FT4. Postpartum hyperthyroidism may be diagnosed by the presence of antimicrosomal or thyroperoxidase antithyroid peroxidase antibodies. Goiter may be present in up to 50% of patients.

Postpartum thyroiditis has two phases

The first phase, also known as the thyrotoxic phase, occurs 1 to 4 months after delivery when transient thyrotoxicosis develops from excessive release of thyroid hormones. The most common symptoms with early postpartum thyroiditis are fatigue and palpitations. Approximately 67% of these women will return to a euthyroid state, and thioamide therapy is generally considered ineffective. Hypothyroidism can develop within 1 month of the onset of thyroiditis.

The second phase occurs between 4 and 8 months postpartum, and these women present with hypothyroidism. Thyromegaly and associated symptoms are common. Unlike the first (thyrotoxic) phase, medical treatment is recommended. Thyroxine treatment should be initiated and maintained for 6 to 12 months. Postpartum thyroiditis carries a 30% risk of recurrence.14

Postpartum thyroiditis may be associated with depression or aggravate symptoms of depression, although the data on this association are conflicting. The largest study addressing this issue concluded that there was no difference in the clinical and psychiatric signs and symptoms between postpartum thyroiditis and controls.15 Nevertheless, it would seem prudent to evaluate thyroid function in postpartum depression if other signs of thyroid dysfunction are present.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A pregnant woman whose thyroid gland isn’t doing its job presents a serious management problem for her obstetrician. If she has overt hypothyroidism, seen in between 0.3% and 2.5% of pregnancies, active intervention is required to prevent serious damage to the fetus.1,2 Even if she has subclinical disease, seen in 2% to 3% of pregnancies, current research indicates that intervention may be indicated.

Fetal thyroxine requirements increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation, when the fetus is still dependent on maternal thyroxine. A deficiency of maternal thyroxine can have severe adverse outcomes, affecting the course of the pregnancy and the neurologic development of the fetus. To prevent such sequelae, patients who were on thyroid medication before pregnancy should increase the dosage by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed, and hypothyroidism that develops in pregnancy should be managed aggressively and meticulously.

Here, we’ll examine the published research to advise you on evidence-based approaches for diagnosis and management of this complex condition.

Maternal thyroid function

An elaborate negative-feedback loop prevails before pregnancy

In a nonpregnant woman, thyroid function is controlled by a negative-feedback loop that works like this:

- The hypothalamus releases thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH)

- TRH acts on the pituitary gland to release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- TSH, in turn, acts on the thyroid gland to release the thyroid hormones iodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) that regulate metabolism

- TRH and TSH concentrations are inversely related to T3 and T4 concentrations. That is, the more TRH and TSH circulating in the blood stream, the less T3 and T4 will be produced by the thyroid gland3

- Almost all (approximately 99%) circulating T3 and T4 is bound to a protein called thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). Only 1% of these hormones circulate in the free form, and only the free forms are biologically active.3

This relationship is illustrated in FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1 Thyroid physiology and the impact of pregnancy

Pregnancy reduces free forms of T3 and T4, and increases TSH slightly

Pregnancy alters thyroid function in significant ways:

- Increases in circulating estrogen lead to the production of more TBG

- When TBG increases, more T3 and T4 are bound and fewer free forms of these hormones are available

- Because the total T3 (TT3) and total free T4 (TT4) are decreased in pregnancy, they are not good measures of thyroid function. Maternal thyroid function in pregnancy should be monitored using free T4 (FT4) and TSH levels

- Increased TBG also leads to a slight increase in TSH between the first trimester and term

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations also increase in pregnancy. Because hCG has thyrotropin-like activity, these higher levels cause a transient decrease in TSH by suppression of TSH production between approximately 8 and 14 weeks of gestation.

Fetal thyroid function

During early gestation, the fetus receives thyroid hormone from the mother.1 Maternal T4 crosses the placenta actively—the only hormone that does so.4 The fetus’s need for thyroxine starts to increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation.5

Fetal thyroid development does not begin until 10 to 12 weeks of gestation, and then continues until term. The fetus relies on maternal T4 exclusively before 12 weeks and partially thereafter for normal fetal neurologic development. It follows that maternal hypothyroidism could be detrimental to fetal development if not detected and corrected very early in gestation.

How (and whom) to screen for maternal hypothyroidism

Routine screening has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of deficient thyroid function.6 In recent years, some authors have recommended screening all pregnant women for thyroid dysfunction, but such recommendations remain controversial.3,7,8 Routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.6

Symptoms overlap typical conditions of pregnancy

The difficulty here is that the characteristic signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism are very similar to physiologic conditions seen in most pregnancies. They include fatigue, constipation, cold intolerance, muscle cramps, hair loss, dry skin, brittle nails, weight gain, intellectual slowness, bradycardia, depression, insomnia, periorbital edema, myxedema, and myxedema coma.6 A side-by-side comparison of pregnancy conditions and hypothyroidism symptoms is provided in TABLE 1.

TABLE 1

Distinguishing hypothyroidism from a normal gestation can be challenging

| SYMPTOM | HYPOTHYROIDISM | PREGNANCY |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | • | • |

| Constipation | • | • |

| Hair loss | • | |

| Dry skin | • | |

| Brittle nails | • | |

| Weight gain | • | • |

| Fluid retention | • | • |

| Bradycardia | • | • |

| Goiter | • | |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | • | • |

Which laboratory tests are informative?

Because screening is controversial and symptomatology does not reliably distinguish hypothyroidism from normal pregnancy, laboratory tests are the standard for diagnosis. Overt hypothyroidism is diagnosed in a symptomatic patient by elevated TSH level and low levels of FT4 and free T3 (FT3). Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as elevated TSH with normal FT4 and FT3 in an asymptomatic patient. Level changes characteristic of normal pregnancy, overt hypothyroidism, and subclinical hypothyroidism are given in TABLE 2.6

TABLE 2

Laboratory diagnosis of hypothyroidism

| MATERNAL CONDITION | TSH | FREE T3 | FREE T4 | TOTAL T3 | TOTAL T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal pregnancy | No change | No change | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Hypothyroidism | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | ↑ | No change | No change | ↓ | ↓ |

| Adapted from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 | |||||

What causes hypothyroidism?

The most common cause of hypothyroidism in most of the world is iodine deficiency. In developed countries, however, where lack of iodine in the diet is not a problem, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, is the most common cause. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is characterized by the presence of antithyroid antibodies, including both thyroid antimicrosomial and antithyroglobulin antibodies. Both iodine deficiency and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are associated with goiter.5 Other causes of hypothyroidism include radioactive iodine therapy for Graves’ disease, a condition we will discuss in Part 2 of this series in February; thyroidectomy; viral thyroiditis; pituitary tumors; Sheehan’s syndrome; and a number of medications.

Causes of hypothyroidism are summarized in TABLE 3.3

TABLE 3

Causes of hypothyroidism

| Iodine deficiency |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

| Radioactive iodine therapy |

| Thyroidectomy |

| Viral thyroiditis |

| Sheehan’s syndrome |

Medications

|

Effects vary by medication

Medications alter thyroid function in different ways. Iodine and lithium inhibit thyroid function and, along with dopamine antagonists, increase TSH levels. Conversely, thioamides, glucocorticoids, dopamine agonists, and somatostatins decrease TSH levels. Finally, ferrous sulfate, sucrafate, cholestyramine, and aluminum hydroxide antacids all inhibit gastrointestinal absorption of thyroid hormone and therefore should not be taken within 4 hours of thyroid medication.6

Maternal hypothyroidism: Effects on fetus, newborn

The impact of maternal hypothyroidism on the fetus depends on the severity of the condition.

- Uncontrolled hypothyroidism. The consequences of this condition can be dire. The possibilities include intrauterine fetal demise and stillbirth, preterm delivery, low birth weight, preeclampsia, and developmental anomalies including reduced intelligence quotient (IQ).1,2,4,6 Blazer and colleagues correlated intrauterine growth with maternal TSH and fetal FT4 and concluded that impaired intrauterine growth is related to abnormal thyroid function and might reflect an insufficient level of hormone production by hypothyroid mothers during pregnancy.9 Maternal and congenital hypothyroidism resulting from severe iodine deficiency are associated with profound neurologic impairment and mental retardation.1,3,10 If the condition is left untreated, cretinism can occur. Congenital cretinism is associated with growth failure, mental retardation, and other neuropsychologic deficits including deaf-mutism.3,4 However, if cretinism is identified and treated in the first 3 months of life, near-normal growth and intelligence can be expected.6 For this reason, all 50 states and the District of Columbia require newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism.6

- Asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism. Several studies have evaluated neonatal outcomes in pregnancy complicated by asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism—that is, women who had previously been diagnosed with hypothyroidism, who have abnormal TSH and FT4 levels, but who do not have symptoms. Pop and colleagues have shown impaired psychomotor development at 10 months in infants born to mothers who had low T4 during the first 12 weeks of gestation.7 Haddow and colleagues correlated elevated maternal TSH levels at less than 17 weeks’ gestation with low IQ scores in the offspring at 7 to 9 years of age.8 Klein and colleagues demonstrated an inverse correlation between a woman’s TSH level during pregnancy and the IQ of her offspring.11 Kooistra and colleagues confirmed that maternal hypothyroxinemia is a risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities that can be identified as early as 3 weeks of age.12 Studies of this relationship are summarized in TABLE 4.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism. During the past decade, researchers have focused attention on neonatal neurologic function in infants born to mothers who had subclinical disease. Mitchell and Klein evaluated the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism at less than 17 weeks’ gestation and subsequently compared the IQs in these children with those of controls.4 They found the mean and standard-deviation IQs of the children in the control and treated groups to be significantly higher than those of the children whose mothers were not treated. Casey and colleagues evaluated pregnancy outcomes in women who had undiagnosed subclinical hypothyroidism.10 They found that such pregnancies were more likely to be complicated by placental abruption and preterm birth, and speculated that the reduced IQ demonstrated in the Mitchell and Klein study might have been related to the effects of prematurity.

TABLE 4

Fetal and neonatal effects of asymptomatic overt hypothyroidism

| STUDY | LABORATORY FINDINGS | OUTCOMES AND RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Kooistra et al12 | ↓ FT4 | Maternal hypothyroxinemia is a risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities as early as 3 weeks of age |

| Casey et al10 | ↑ TSH | Pregnancies with undiagnosed subclinical hypothyroidism were more likely to be complicated by placental abruption and preterm birth. The reduced IQ seen in a prior study (Mitchell and Klein4) may be related to effects of prematurity |

| Mitchell and Klein4 | ↑ TSH | The mean and standard deviation of IQs of the children of treated mothers with hypothyroidism and the control group were significantly higher than those for children of untreated hypothyroid women |

| Blazer et al9 | ↑ maternal TSH, ↑ fetal FT4 | Impaired intrauterine growth may reflect insufficient levels of hormone replacement therapy in hypothyroid mothers during pregnancy |

| Pop et al7 | ↓ FT4 | Impaired psychomotor development at 10 months of age in offspring of mothers with low T4 at ≤12 weeks |

| Haddow et al8 | ↑ TSH, ↓ FT4 | Elevated TSH levels at <17 weeks’ gestation are associated with low IQ scores at 7 to 9 years of age. Routine screening for thyroid deficiency may be warranted |

| Klein et al11 | ↑ TSH, ↓ FT4, ↓ TT4 | Inverse correlation between TSH during pregnancy and IQ of offspring |

| FT4=free thyroxine, TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone, TT4=total thyroxine | ||

Managing hypothyroidism in pregnancy

The treatment of choice for correction of hypothyroidism is synthetic T4, or levothyroxine (Levothyroid, Levoxyl, Synthroid, and Unithroid). Initial treatment in the nonpregnant patient is 1.7 μg/kg/day or 12.5 to 25 μg/day adjusted by 25 μg/day every 2 to 4 weeks until a euthyroid state is achieved.13

Patients who were on thyroxine therapy before pregnancy should increase the dose by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed.1,5 Serum thyrotropin levels should be monitored every 4 weeks to maintain a TSH level between 1 and 2 mU/L and FT4 in upper third of normal.1 Once a euthyroid state has been achieved, thyrotropin levels should be monitored every trimester until delivery. FIGURE 2 provides an algorithm for management of hypothyroidism in pregnancy.

FIGURE 2 During pregnancy, thyroid function merits regular monitoring, fine-tuning of treatment

Postpartum thyroiditis

About 5% of all obstetrical patients develop postpartum thyroiditis. Approximately 45% of these women present with hypothyroidism, with the rest evenly divided between thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism) and thyrotoxicosis followed by hypothyroidism. Unfortunately, the signs and symptoms of hypo- and hyperthyroidism are similar to the postpartum state. Many of these patients are not diagnosed. A high index of suspicion warrants thyroid function testing. Women who have a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus have a 25% chance of developing postpartum thyroid dysfunction.

The diagnosis is made by documenting abnormal levels of TSH and FT4. Postpartum hyperthyroidism may be diagnosed by the presence of antimicrosomal or thyroperoxidase antithyroid peroxidase antibodies. Goiter may be present in up to 50% of patients.

Postpartum thyroiditis has two phases

The first phase, also known as the thyrotoxic phase, occurs 1 to 4 months after delivery when transient thyrotoxicosis develops from excessive release of thyroid hormones. The most common symptoms with early postpartum thyroiditis are fatigue and palpitations. Approximately 67% of these women will return to a euthyroid state, and thioamide therapy is generally considered ineffective. Hypothyroidism can develop within 1 month of the onset of thyroiditis.

The second phase occurs between 4 and 8 months postpartum, and these women present with hypothyroidism. Thyromegaly and associated symptoms are common. Unlike the first (thyrotoxic) phase, medical treatment is recommended. Thyroxine treatment should be initiated and maintained for 6 to 12 months. Postpartum thyroiditis carries a 30% risk of recurrence.14

Postpartum thyroiditis may be associated with depression or aggravate symptoms of depression, although the data on this association are conflicting. The largest study addressing this issue concluded that there was no difference in the clinical and psychiatric signs and symptoms between postpartum thyroiditis and controls.15 Nevertheless, it would seem prudent to evaluate thyroid function in postpartum depression if other signs of thyroid dysfunction are present.

1. Idris I, Srinivasan R, Simm A, Page RC. Effects of maternal hyperthyroidism during early gestation on neonatal and obstetric outcome. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;65:133-135.

2. Girling JC. Thyroid disorders in pregnancy. Curr Obstet Gynecol. 2006;16:47-53.

3. Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams J. Maternal–Fetal Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2004:1063-1082.

4. Mitchell ML, Klein RZ. The sequelae of untreated maternal hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 Suppl 3:U45-U48.

5. Alexander EK, Marqusee E, Lawrence J, Jarolim P, Fischer GA, Larsen PR. Timing and magnitude of increases in levothyroxine requirements during pregnancy in women with hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:241-249.

6. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 32, November 2001). Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:387-396.

7. Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:149-155.

8. Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:549-555.

9. Blazer S, Moreh-Waterman Y, Miller-Lotan R, Tamir A, Hochberg Z. Maternal hypothyroidism may affect fetal growth and neonatal thyroid function. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:232-241.

10. Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:239-245.

11. Klein RZ, Haddow JE, Faix JD, et al. Prevalence of thyroid deficiency in pregnant women. Clin Endocrinol. 1991;35:41-46.

12. Kooistra L, Crawford S, van Baar AL, Brouwers EP, Pop VJ. Neonatal effects of maternal hypothyroxinemia during early pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2006;117:161-167.

13. Levothyroxine: Drug information. Lexicomp. http://www.utdol.com/utd/content/topic.do?topicKey=drug_l_z/143814&type=A&selectedTitle=2~39. Accessed December 14, 2007.

14. Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1283-1292.

15. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;51:429-438.

1. Idris I, Srinivasan R, Simm A, Page RC. Effects of maternal hyperthyroidism during early gestation on neonatal and obstetric outcome. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;65:133-135.

2. Girling JC. Thyroid disorders in pregnancy. Curr Obstet Gynecol. 2006;16:47-53.

3. Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams J. Maternal–Fetal Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2004:1063-1082.

4. Mitchell ML, Klein RZ. The sequelae of untreated maternal hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 Suppl 3:U45-U48.

5. Alexander EK, Marqusee E, Lawrence J, Jarolim P, Fischer GA, Larsen PR. Timing and magnitude of increases in levothyroxine requirements during pregnancy in women with hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:241-249.

6. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. (Replaces Practice Bulletin Number 32, November 2001). Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:387-396.

7. Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:149-155.

8. Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:549-555.

9. Blazer S, Moreh-Waterman Y, Miller-Lotan R, Tamir A, Hochberg Z. Maternal hypothyroidism may affect fetal growth and neonatal thyroid function. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:232-241.

10. Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:239-245.

11. Klein RZ, Haddow JE, Faix JD, et al. Prevalence of thyroid deficiency in pregnant women. Clin Endocrinol. 1991;35:41-46.

12. Kooistra L, Crawford S, van Baar AL, Brouwers EP, Pop VJ. Neonatal effects of maternal hypothyroxinemia during early pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2006;117:161-167.

13. Levothyroxine: Drug information. Lexicomp. http://www.utdol.com/utd/content/topic.do?topicKey=drug_l_z/143814&type=A&selectedTitle=2~39. Accessed December 14, 2007.

14. Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1283-1292.

15. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;51:429-438.

PRENATAL COUNSELING

Investigations of maternal alcohol consumption have consistently produced the same finding: Even a low level of alcohol—especially in the first trimester—has a harmful effect on fetal development. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), American Academy of Pediatricians, and the US Surgeon General now support the tenet that no lower limit of alcohol consumption is safe during pregnancy.

Although a specific fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) was not identified until 1968, the adverse effects of alcohol during pregnancy have been observed for centuries. FAS is the most severe manifestation of maternal alcohol consumption and is estimated to affect 0.2 to 1.5 of every 1,000 births. The term refers to a “constellation of physical abnormalities” and “problems of behavior and cognition in children born to mothers who drank heavily during pregnancy.”1 The syndrome is also “completely preventable.”1

The US Surgeon General recommends that health professionals:

- routinely inquire about alcohol consumption in women of childbearing age

- inform them of the risks of alcohol consumption during pregnancy

- advise them not to drink during pregnancy.2

New drinking pattern emerges

Of special concern is binge drinking, initially defined as the consumption of five or more drinks during one session, even among women who do not chronically consume alcohol. Like lower levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy, binge drinking increases the risk of developmental and growth delays in the child. The higher peak levels of alcohol associated with binge drinking appear particularly deleterious to fetal neurodevelopment. And because a woman may engage in binge drinking before she is aware that she is pregnant, the issue merits particular attention.

Hallmarks of FAS

FAS causes facial dysmorphia, including short palpebral fissures, flattened midfacies, epicanthal folds, and micrognathia. Defects of the central nervous system and cardiac, renal, and skeletal systems also can occur, along with prenatal and postnatal growth delay. In addition, developmental delay is present.

FAS can be present even if history of alcohol exposure is uncertain

In 1996, the Institute of Medicine broadened the classification of FAS to include:

- Category 1 – FAS with a confirmed history of maternal alcohol exposure

- Category 2 – FAS with no confirmed history of maternal alcohol exposure

- Category 3 – partial FAS with a history of maternal alcohol exposure

- Category 4 – alcohol-related birth defects (physical anomalies only)

- Category 5 – alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders.1

Alcohol exposure linked to a spectrum of effects

In 2005, the term “fetal alcohol spectrum disorder” (FASD) entered the lexicon. FASD is not intended to be used as a clinical diagnosis but to describe a spectrum of conditions that may result from prenatal alcohol exposure.

The prevalence of FASD is uncertain, although alcohol-related neurobehavioral abnormalities that affect learning and behavior may occur in three additional children for every one child who is given a diagnosis of classic FAS.

In this Update, I highlight recent studies or publications that:

- describe drinking patterns among women of reproductive age

- offer screening strategies or

- suggest a framework for counseling the patient to reduce or eliminate alcohol consumption.

Which women are most likely to drink during pregnancy?

Tsai J, Floyd RL, Green PP, Bouyle CA. Patterns and average volume of alcohol use among women of childbearing age. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:437–445.

Tsai J, Floyd RL, Bertrand J. Tracking binge drinking among childbearing-age women. Prev Med. 2007; 44:298–302.

Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Floyd L, McGrath C. The epidemiology of drinking among women of childbearing age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1023–1030.

Studies that led to the phenotypic description of FASD focused on women who had recognized alcohol dependency and who drank heavily. Additional research has identified another subset of women who are likely to continue alcohol consumption during pregnancy: binge drinkers. Many women who report binge drinking do not consider their alcohol consumption to be chronic or excessive.

Binge drinking is on the rise among women of childbearing age…

Binge drinking has increased steadily over the past 10 years despite public health initiatives and other programs developed to educate consumers. Tsai and colleagues used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System from 2001 to 2003 to calculate the magnitude of alcohol consumption among women of childbearing age. The rate of binge drinking increased from 10.3% to 13% between 1991 and 2003. In 2003, the highest prevalence of binge drinking was observed in the 18- to 24-year-old age group (20.5%), and among non-Hispanic white (15.5%), employed (14%), college-educated (13.3%), and unmarried women (18.7%). The highest number of binge sessions in the preceding month followed the same pattern.

In 2004, as it became clear that the adverse effects of binge alcohol consumption were more significant in women than men, at-risk binge drinking was redefined as more than three drinks in a single session.

…and also on the rise among pregnant women

In a separate study by Tsai and colleagues using the same data, one in 50 gravidas reported alcohol consumption in a binge fashion during the current pregnancy, with a background rate of 9% to 12% of pregnant women who reported any use of alcohol. More than 50% of the pregnant women who reported binge drinking said they had engaged in binge drinking at least twice during the preceding month.

Binge drinking and unplanned pregnancy—a risky combination

Binge drinking among women of reproductive age is especially risky because roughly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, so a woman may unwittingly engage in binge drinking during pregnancy. The rate of unintended pregnancy is highest among adolescents (82%) and 20- to 24-year-olds (61%), the groups with the highest rate of binge drinking (20%) and the most episodes in the preceding month (3.5). These figures suggest that efforts to prevent FAS should encompass the concept of binge drinking as an at-risk behavior and focus on all women of reproductive age, not just those known to be pregnant.

The typical binge drinker? She’s young, white, single, and employed

Utilizing the 2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, Caetano and colleagues explored alcohol consumption among women of reproductive age before they recognized they were pregnant. Women of childbearing age who are social drinkers but develop a pattern of binge drinking represent a larger percentage of the female population than do women who consume alcohol daily, but both groups face an increased risk of bearing a child with alcohol-related neurodevelopmental difficulties.

Unplanned pregnancies were associated with a higher rate of preconception binge drinking than were planned gestations, and unmarried Caucasian women who smoked were most likely to engage in preconception binge drinking.

When the year preceding the study was assessed for both alcohol use and pregnancy, Caetano and associates found that 20% of women met the criteria for binge drinking or alcohol dependence. The high prevalence probably reflects the longer time span for acknowledgment of alcohol consumption (an entire year) and the lower drink limit for the redefined term “binge drinking” (in this study, it was defined as four drinks or more rather than five or more drinks on one occasion). The highest-risk women were young, single, and Caucasian, and had a higher income (>$40,000). White women had higher rates of binge drinking than black or Hispanic women at comparable ages, marital status, and income levels.

What’s the best way to screen for “at-risk” alcohol consumption?

Drinking and Reproductive Health: A Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Prevention Tool Kit. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2006. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/acog_toolkit.htm

In 2006, in collaboration with the CDC, ACOG developed a comprehensive educational tool kit for physicians. The kit, which can be downloaded from the CDC Web site, outlines office-based screening for at-risk drinking patterns in pregnant and nonpregnant women. It includes a screening tool—T-ACE—that has proved to be effective and can be incorporated into practice fairly efficiently. T-ACE and a similar tool—TWEAK—are presented in the TABLE.

ACOG recommends, and research supports, routine screening of all women of childbearing age. Studies assessing the prevalence of at-risk drinking and the efficacy of various interventions suggest that screening for alcohol use should be a routine part of prenatal care—as well as annual gynecologic care among women of childbearing age. One applicable approach is incorporation of a screening tool into the health-and-habits questionnaire administered to the patient.

Available as companion pieces to the tool kit are patient education sheets covering the risks of alcohol exposure and emphasizing basic concepts such as:

- alcohol equivalency (12 oz of beer=5 oz of wine=1 oz of liquor)

- risks of alcohol exposure before pregnancy is recognized

- goals for reducing or eliminating alcohol consumption.

Use these tools to screen for excessive alcohol consumption

| FOCUS | QUESTION | POINTS |

|---|---|---|

| T-ACE (a positive screen is ≥2 points) | ||

| (T) Tolerance | How many drinks does it take to make you feel high? | 1 point per drink |

| (A) Annoyed | Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? | Yes = 1 point |

| (C) Cut down | Have you ever felt you ought to cut down on your drinking? | Yes = 1 point |

| (E) Eye-opener | Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover? | Yes = 1 point |

| TWEAK (a positive screen is ≥2 points) | ||

| (T) Tolerance | Are more than two drinks necessary to make you feel high? | Yes = 2 points |

| (W) Worry | Are your friends or family worried about your level of alcohol consumption? | Yes = 1 point |

| (E) Eye-opener | Do you ever need to drink in the morning? | Yes = 1 point |

| (A) Amnesia | Do you ever black out when drinking? | Yes = 1 point |

| (K) Cut down | Do you believe you need to cut down on your drinking? | Yes = 1 point |

Are efforts to reduce alcohol use among gravidas successful?

Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez M, et al; Project CHOICES Efficacy Study Group. Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:1–10.

Brief intervention has been a successful tool for changing the behavior of nonpregnant adults. It also appears to be effective and efficient in the pregnant population. A brief intervention typically consists of a time-limited motivational counseling session that aims to educate, recommend a change in habits, and help the patient set goals. Brief intervention has had special success among nondependent women and has been used effectively in obstetric clinics and among women of various racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

This randomized, controlled trial by Floyd and colleagues focused on the pregnant population. Like three other brief intervention trials conducted between 2000 and 2006, it found that brief intervention reduced alcohol consumption, increased positive newborn outcomes, and decreased alcohol consumption in subsequent pregnancies.3-5

FRAMES model: 6 manageable steps

One successful brief intervention is the FRAMES model, which is included in the ACOG tool kit for physicians. It is based on concepts of:

- feedback (F) – compare the patient’s level of drinking with drinking patterns that are not risky

- responsibility (R) – emphasize that it is up to her to change her habits

- advice (A) – counsel her to change her behavior

- menu (M) – identify risky drinking situations and offer tactics for coping

- empathy (E) – be understanding

- self-efficacy (S) – encourage the patient to set goals and commit to change.

Use an individualized approach to change behavior

Despite widespread, population-based educational efforts throughout the 1990s, the prevalence of alcohol consumption among nonpregnant and pregnant women remains largely unchanged or even increased, particularly binge drinking. Other approaches are needed to avert the largest preventable contributor to birth defects and childhood neurodevelopmental disability.

With improved and validated office-based methods for identifying alcohol consumption, along with referrals when appropriate, it is possible to reduce maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy. These simple methods are also easy to incorporate into an office routine. Equally important is incorporation of these methods into the office visit for the nonpregnant woman of reproductive age, with the aim of reducing alcohol consumption and increasing use of effective contraception.

1. Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F. eds. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. Available at: www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=4991&page=R1. Accessed December 5, 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Alcohol Use in Pregnancy. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/pressreleases/sg02222005.html. Accessed December 5, 2007.

3. Manwell LB, Fleming MF, Mundt MP, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL. Treatment of problem alcohol use in women of childbearing age: results of a brief intervention trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1517-1524.

4. Ingersoll KS, Ceperich SD, Nettleman MD, Karanda K, Brocksen S, Johnson BA. Reducing alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk in college women: initial outcomes of a clinical trial of a motivational intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29:173-189.

5. Chang G, Wilkins-Haug BS, Goetz MA. Brief interventions for alcohol use in pregnancy: a randomized trial. Addiction. 1999;94:1499-1508.

Investigations of maternal alcohol consumption have consistently produced the same finding: Even a low level of alcohol—especially in the first trimester—has a harmful effect on fetal development. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), American Academy of Pediatricians, and the US Surgeon General now support the tenet that no lower limit of alcohol consumption is safe during pregnancy.

Although a specific fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) was not identified until 1968, the adverse effects of alcohol during pregnancy have been observed for centuries. FAS is the most severe manifestation of maternal alcohol consumption and is estimated to affect 0.2 to 1.5 of every 1,000 births. The term refers to a “constellation of physical abnormalities” and “problems of behavior and cognition in children born to mothers who drank heavily during pregnancy.”1 The syndrome is also “completely preventable.”1

The US Surgeon General recommends that health professionals:

- routinely inquire about alcohol consumption in women of childbearing age

- inform them of the risks of alcohol consumption during pregnancy

- advise them not to drink during pregnancy.2

New drinking pattern emerges

Of special concern is binge drinking, initially defined as the consumption of five or more drinks during one session, even among women who do not chronically consume alcohol. Like lower levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy, binge drinking increases the risk of developmental and growth delays in the child. The higher peak levels of alcohol associated with binge drinking appear particularly deleterious to fetal neurodevelopment. And because a woman may engage in binge drinking before she is aware that she is pregnant, the issue merits particular attention.

Hallmarks of FAS

FAS causes facial dysmorphia, including short palpebral fissures, flattened midfacies, epicanthal folds, and micrognathia. Defects of the central nervous system and cardiac, renal, and skeletal systems also can occur, along with prenatal and postnatal growth delay. In addition, developmental delay is present.

FAS can be present even if history of alcohol exposure is uncertain

In 1996, the Institute of Medicine broadened the classification of FAS to include:

- Category 1 – FAS with a confirmed history of maternal alcohol exposure

- Category 2 – FAS with no confirmed history of maternal alcohol exposure

- Category 3 – partial FAS with a history of maternal alcohol exposure

- Category 4 – alcohol-related birth defects (physical anomalies only)

- Category 5 – alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders.1

Alcohol exposure linked to a spectrum of effects

In 2005, the term “fetal alcohol spectrum disorder” (FASD) entered the lexicon. FASD is not intended to be used as a clinical diagnosis but to describe a spectrum of conditions that may result from prenatal alcohol exposure.

The prevalence of FASD is uncertain, although alcohol-related neurobehavioral abnormalities that affect learning and behavior may occur in three additional children for every one child who is given a diagnosis of classic FAS.

In this Update, I highlight recent studies or publications that:

- describe drinking patterns among women of reproductive age

- offer screening strategies or

- suggest a framework for counseling the patient to reduce or eliminate alcohol consumption.

Which women are most likely to drink during pregnancy?

Tsai J, Floyd RL, Green PP, Bouyle CA. Patterns and average volume of alcohol use among women of childbearing age. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:437–445.

Tsai J, Floyd RL, Bertrand J. Tracking binge drinking among childbearing-age women. Prev Med. 2007; 44:298–302.

Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Floyd L, McGrath C. The epidemiology of drinking among women of childbearing age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1023–1030.

Studies that led to the phenotypic description of FASD focused on women who had recognized alcohol dependency and who drank heavily. Additional research has identified another subset of women who are likely to continue alcohol consumption during pregnancy: binge drinkers. Many women who report binge drinking do not consider their alcohol consumption to be chronic or excessive.

Binge drinking is on the rise among women of childbearing age…

Binge drinking has increased steadily over the past 10 years despite public health initiatives and other programs developed to educate consumers. Tsai and colleagues used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System from 2001 to 2003 to calculate the magnitude of alcohol consumption among women of childbearing age. The rate of binge drinking increased from 10.3% to 13% between 1991 and 2003. In 2003, the highest prevalence of binge drinking was observed in the 18- to 24-year-old age group (20.5%), and among non-Hispanic white (15.5%), employed (14%), college-educated (13.3%), and unmarried women (18.7%). The highest number of binge sessions in the preceding month followed the same pattern.

In 2004, as it became clear that the adverse effects of binge alcohol consumption were more significant in women than men, at-risk binge drinking was redefined as more than three drinks in a single session.

…and also on the rise among pregnant women

In a separate study by Tsai and colleagues using the same data, one in 50 gravidas reported alcohol consumption in a binge fashion during the current pregnancy, with a background rate of 9% to 12% of pregnant women who reported any use of alcohol. More than 50% of the pregnant women who reported binge drinking said they had engaged in binge drinking at least twice during the preceding month.

Binge drinking and unplanned pregnancy—a risky combination

Binge drinking among women of reproductive age is especially risky because roughly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, so a woman may unwittingly engage in binge drinking during pregnancy. The rate of unintended pregnancy is highest among adolescents (82%) and 20- to 24-year-olds (61%), the groups with the highest rate of binge drinking (20%) and the most episodes in the preceding month (3.5). These figures suggest that efforts to prevent FAS should encompass the concept of binge drinking as an at-risk behavior and focus on all women of reproductive age, not just those known to be pregnant.

The typical binge drinker? She’s young, white, single, and employed

Utilizing the 2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, Caetano and colleagues explored alcohol consumption among women of reproductive age before they recognized they were pregnant. Women of childbearing age who are social drinkers but develop a pattern of binge drinking represent a larger percentage of the female population than do women who consume alcohol daily, but both groups face an increased risk of bearing a child with alcohol-related neurodevelopmental difficulties.

Unplanned pregnancies were associated with a higher rate of preconception binge drinking than were planned gestations, and unmarried Caucasian women who smoked were most likely to engage in preconception binge drinking.

When the year preceding the study was assessed for both alcohol use and pregnancy, Caetano and associates found that 20% of women met the criteria for binge drinking or alcohol dependence. The high prevalence probably reflects the longer time span for acknowledgment of alcohol consumption (an entire year) and the lower drink limit for the redefined term “binge drinking” (in this study, it was defined as four drinks or more rather than five or more drinks on one occasion). The highest-risk women were young, single, and Caucasian, and had a higher income (>$40,000). White women had higher rates of binge drinking than black or Hispanic women at comparable ages, marital status, and income levels.

What’s the best way to screen for “at-risk” alcohol consumption?

Drinking and Reproductive Health: A Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Prevention Tool Kit. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2006. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/acog_toolkit.htm

In 2006, in collaboration with the CDC, ACOG developed a comprehensive educational tool kit for physicians. The kit, which can be downloaded from the CDC Web site, outlines office-based screening for at-risk drinking patterns in pregnant and nonpregnant women. It includes a screening tool—T-ACE—that has proved to be effective and can be incorporated into practice fairly efficiently. T-ACE and a similar tool—TWEAK—are presented in the TABLE.

ACOG recommends, and research supports, routine screening of all women of childbearing age. Studies assessing the prevalence of at-risk drinking and the efficacy of various interventions suggest that screening for alcohol use should be a routine part of prenatal care—as well as annual gynecologic care among women of childbearing age. One applicable approach is incorporation of a screening tool into the health-and-habits questionnaire administered to the patient.

Available as companion pieces to the tool kit are patient education sheets covering the risks of alcohol exposure and emphasizing basic concepts such as:

- alcohol equivalency (12 oz of beer=5 oz of wine=1 oz of liquor)

- risks of alcohol exposure before pregnancy is recognized

- goals for reducing or eliminating alcohol consumption.

Use these tools to screen for excessive alcohol consumption

| FOCUS | QUESTION | POINTS |

|---|---|---|

| T-ACE (a positive screen is ≥2 points) | ||

| (T) Tolerance | How many drinks does it take to make you feel high? | 1 point per drink |

| (A) Annoyed | Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? | Yes = 1 point |

| (C) Cut down | Have you ever felt you ought to cut down on your drinking? | Yes = 1 point |

| (E) Eye-opener | Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover? | Yes = 1 point |

| TWEAK (a positive screen is ≥2 points) | ||

| (T) Tolerance | Are more than two drinks necessary to make you feel high? | Yes = 2 points |

| (W) Worry | Are your friends or family worried about your level of alcohol consumption? | Yes = 1 point |