User login

Vaccinations for the ObGyn’s toolbox

CASE 1st prenatal appointment for young, pregnant migrant

A 21-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks’ gestation recently immigrated to the United States from an impoverished rural area of Southeast Asia. On the first prenatal appointment, she is noted to have no evidence of immunity to rubella, measles, or varicella. Her hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody tests are negative. She also has negative test results for gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV infection. Her pap test is negative.

- What vaccinations should this patient receive during her pregnancy?

- What additional vaccinations are indicated postpartum?

Preventive vaccinations: What to know

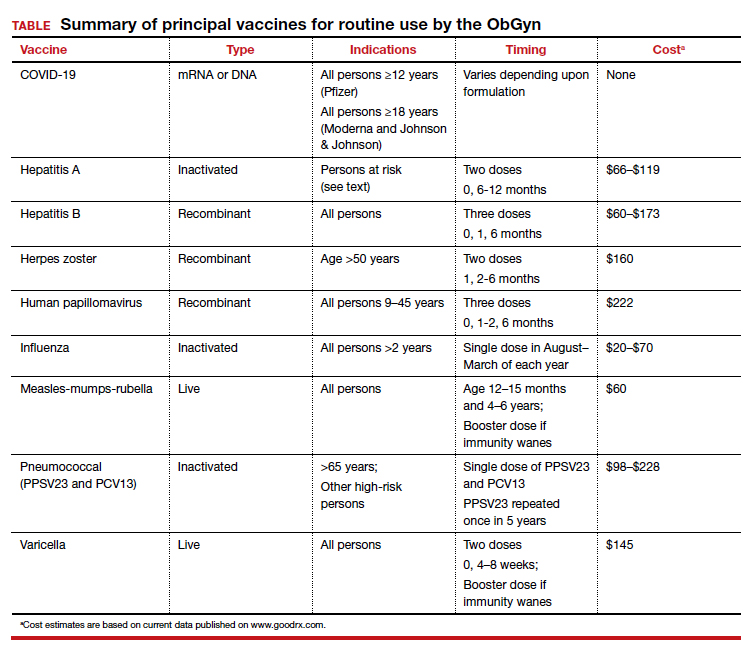

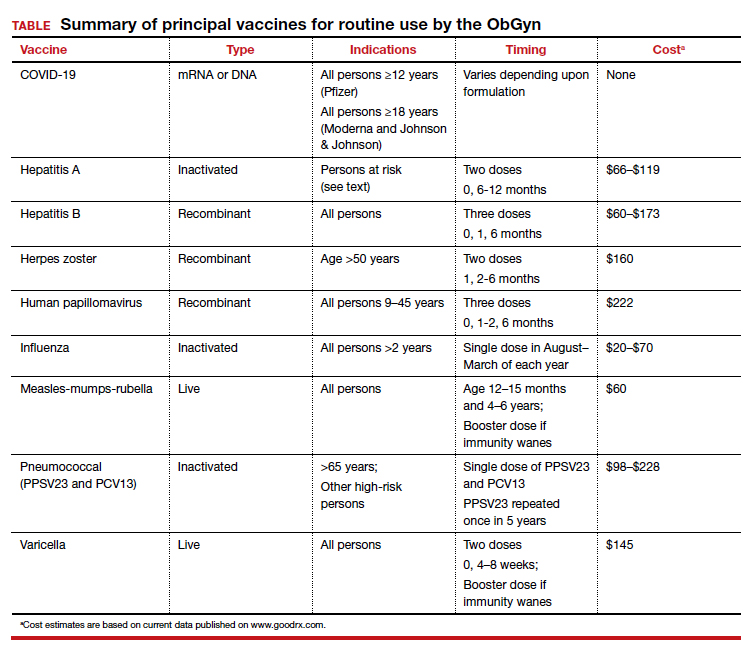

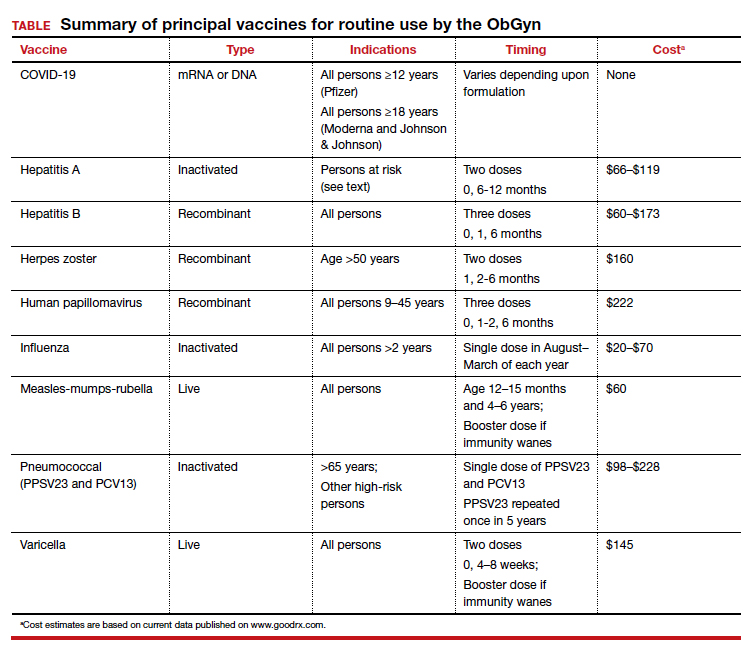

As ObGyns, we serve as the primary care physician for many women throughout their early and middle decades of life. Accordingly, we have an obligation to be well informed about preventive health services such as vaccinations. The purpose of this article is to review the principal vaccines with which ObGyns should be familiar. I will discuss the vaccines in alphabetical order and then focus on the indications and timing for each vaccine and the relative cost of each immunization. Key points are summarized in the TABLE.

COVID-19 vaccine

In the latter part of 2020 and early part of 2021, three COVID-19 vaccines received emergency use authorization (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for individuals 16 years of age and older (Pfizer-BioNTech) and 18 years of age and older (Moderna and Johnson & Johnson).1 The cost of their administration is borne by the federal government. Two of the vaccines are mRNA agents—Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech. Both are administered in a 2-dose series, separated by 4 and 3 weeks, respectively. The efficacy of these vaccines in preventing serious or critical illness approaches 95%. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has now been fully FDA approved for administration to individuals older than age 16, with EUA for those down to age 12. Full approval of the Moderna vaccine will not be far behind. Because of some evidence suggesting waning immunity over time and because of growing concerns about the increased transmissibility of the delta variant of the virus, the FDA has been strongly considering a recommendation for a third (booster) dose of each of these vaccines, administered 8 months after the second dose for all eligible Americans. On September 17, 2021, the FDA advisory committee recommended a booster for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for people older than age 65 and for those over the age of 16 at high risk for severe COVID-19. Several days later, full FDA approval was granted for this recommendation. Subsequently, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) included health care workers and pregnant women in the group for whom the booster is recommended.

The third vaccine formulation is the Johnson & Johnson DNA vaccine, which is prepared with a human adenovirus vector. This vaccine is administered in a single intramuscular dose and has a reported efficacy of 66% to 85%, though it may approach 95% in preventing critical illness. The FDA is expected to announce decisions about booster doses for the Johnson & Johnson and Moderna vaccines in the coming weeks.

Although initial trials of the COVID-19vaccines excluded pregnant and lactating women, the vaccines are safe in pregnancy or postpartum. In fact the vaccines do not contain either a killed or attenuated viral particle that is capable of transmitting infection. Therefore, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine now support routine immunization during pregnancy.

A recent report by Shimabukuro and colleagues2 demonstrated that the risk of vaccine-related complications in pregnant women receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccines was no different than in nonpregnant patients and that there was no evidence of teratogenic effects. The trial included more than 35,000 pregnant women; 2.3% were vaccinated in the periconception period, 28.6% in the first trimester, 43.3% in the second trimester, and 25.7% in the third trimester. Given this, and in light of isolated reports of unusual thromboembolic complications associated with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, I strongly recommend use of either the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in our prenatal and postpartum patients.

Continue to: Hepatitis A vaccine...

Hepatitis A vaccine

The hepatitis A vaccine is an inactivated vaccine and is safe for use in pregnancy. It is available in two monovalent preparations—Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co.) and is administered in a 2-dose intramuscular injection at time zero and 6 to 12 months later.3 The vaccine is also available in a bivalent form with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine—Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline). When administered in this form, the vaccine should be given at time zero, 1 month, and 6 months. The wholesale cost of the monovalent vaccine is $66 to $119, depending upon whether the provider uses a multi-dose or a single-dose vial. The cost of Twinrix is $149.

The hepatitis A vaccine is indicated for select pregnant and nonpregnant patients:

- international travelers

- intravenous drug users

- those with occupational exposure (eg, individuals who work in a primate laboratory)

- residents and staff in chronic care facilities

- individuals with chronic liver disease

- individuals with clotting factor disorders

- residents in endemic areas.

Hepatitis B vaccine

The hepatitis B vaccine is a recombinant vaccine that contains an inactivated portion of the hepatitis B surface antigen. It was originally produced in two monovalent formulations: Engerix B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax-HB (Merck & Co.). These original formulations are given in a 3-dose series at time zero, 1 month, and 6 months. Recently, a new and more potent formulation was introduced into clinical practice. Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies Co.) is also a recombinant vaccine that contains a boosting adjuvant. It is programed to be administered in a 2-dose series at time zero and 1 month.4-6

The wholesale cost of the monovalent vaccines varies from $60 to $173, depending upon use of a multi-dose vial versus a single-use vial. The cost of Heplisav-B varies from $146 to $173, depending upon use of a prefilled syringe versus a single-dose vial.

Although the hepatitis B vaccine should be part of the childhood immunization series, it also should be administered to any pregnant woman who has not been vaccinated previously or who does not already have evidence of immunity as a result of natural infection.

Continue to: Herpes zoster vaccine...

Herpes zoster vaccine

Herpes zoster infection (shingles) can be a particularly disabling condition in older patients and results from reactivation of a latent varicella-zoster infection. Shingles can cause extremely painful skin lesions, threaten the patient’s vision, and result in long-lasting postherpetic neuralgia. Both cellular and hormonal immunity are essential to protect against recurrent infection.

The original herpes zoster vaccine (Zoster Vaccine Live; ZVL, Zostavax) is no longer produced in the United States because it is not as effective as the newer vaccine—Recombinant Zoster Vaccine (Shingrix, GlaxoSmithKline).7,8 The antigen in the new vaccine is a component of the surface glycoprotein E, and it is combined with an adjuvant to enhance immunoreactivity. The vaccine is given intramuscularly in two doses at time zero and again at 2 to 6 months and is indicated for all individuals >50 years, including those who may have had an episode of shingles. This newer vaccine is 97% effective in patients >50 years and 90% effective in patients >70. The wholesale cost of each injection is about $160.

Human papillomavirus vaccine

The HPV vaccine (Gardasil-9, Merck & Co.) is a recombinant 9-valent vaccine directed against the human papillomavirus. It induces immunity to serotypes 6 and 11 (which cause 90% of genital warts), 16 and 18 (which cause 80% of genital cancers), and 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (viral strains that are responsible for both genital and oropharyngeal cancers). The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in a 3-dose series at time zero, 1-2 months, and 6 months. The principal target groups for the vaccine are males and females, ages 9 to 45 years. Ideally, children of both sexes should receive this vaccine prior to the onset of sexual activity. The wholesale cost of each vaccine injection is approximately $222.9

Influenza vaccine

The inactivated, intramuscular flu vaccine is recommended for anyone over age 2, including pregnant women. Although pregnant women are not more likely to acquire flu compared with those who are not pregnant, if they do become infected, they are likely to become more seriously ill, with higher mortality. Accordingly, all pregnant women should receive, in any trimester, the inactivated flu vaccine beginning in the late summer and early fall of each year and extending through March of the next year.10,11

Multiple formulations of the inactivated vaccine are marketed, all targeting two strains of influenza A and two strains of influenza B. The components of the vaccine vary each year as scientists try to match the new vaccine with the most highly prevalent strains in the previous flu season. The vaccine should be administered in a single intramuscular dose. The cost varies from approximately $20 to $70.

The intranasal influenza vaccine is a live virus vaccine that is intended primarily for children and should not be administered in pregnancy. In addition, there is a higher dose of the inactivated quadrivalent vaccine that is available for administration to patients over age 65. This higher dose is more likely to cause adverse effects and is not indicated in pregnancy.

Continue to: Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (MMR)...

Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (MMR)

The MMR is a standard component of the childhood vaccination series. The trivalent preparation is a live, attenuated vaccine that is typically given subcutaneously in a 2-dose series. The first dose is administered at age 12-15 months, and the second dose at age 4-6 years. The vaccine is highly immunogenic, with vaccine-induced immunity usually life-long. In some patients, however, immunity wanes over time. Accordingly, all pregnant women should be screened for immunity to rubella since, of the 3, this infection poses the greatest risk to the fetus. Women who do not have evidence of immunity should be advised to avoid contact with children who may have a viral exanthem. They should then receive a booster dose of the vaccine immediately postpartum and should practice secure contraception for 1 month. The vaccine cost is approximately $60.

Pneumococcal vaccine

The inactivated pneumococcal vaccine is produced in two forms, both of which are safe for administration in pregnancy.12 The original vaccine, introduced in 1983, was PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23, Merck & Co), a 23-serovalent vaccine that was intended primarily for adults. This vaccine is administered in a single subcutaneous or intramuscular dose. The newest vaccine, introduced in 2010, is PCV13 (Prevnar 13, Pfizer Inc), a 13-serovalent vaccine. It was intended primarily for children, in whom it is administered in a 4-dose series beginning at 6 to 8 weeks of age. The cost of the former is approximately $98 to $120; the cost of the latter is $228.

Vaccination against pneumococcal infection is routinely indicated for those older than the age of 65 and for the following at-risk patients, including those who are pregnant11:

- individuals who have had a splenectomy or who have a medical illness that produces functional asplenia (eg, sickle cell anemia)

- individuals with chronic cardiac, pulmonic, hepatic, or renal disease

- individuals with immunosuppressive conditions such as HIV infection or a disseminated malignancy

- individuals who have a cochlear implant

- individuals who have a chronic leak of cerebrospinal fluid.

The recommendations for timing of these 2 vaccines in adults can initially appear confusing. Put most simply, if a high-risk patient first receives the PCV13 vaccine, she should receive the PPSV23 vaccine in about 8 weeks. The PPSV23 vaccine should be repeated in 5 years. If an at-risk patient initially receives the PPSV23 vaccine, the PCV13 vaccine should be given 1 year later.12

Tdap vaccine

The Tdap vaccine contains tetanus toxoid, reduced diptheria toxoid, and an acellular component of the pertussis bacterium. Although it has long been part of the childhood vaccinations series, immunity to each component, particularly pertussis, tends to wane over time.

Pertussis poses a serious risk to the health of the pregnant woman and the newborn infant. Accordingly, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), CDC, and the ACOG now advise administration of a booster dose of this vaccine in the early third trimester of each pregnancy.13-15 The vaccine should be administered as a single intramuscular injection. The approximate cost of the vaccine is $64 to $71, depending upon whether the provider uses a single-dose vial or a single-dose prefilled syringe. In nonpregnant patients, the ACIP currently recommends administration of a booster dose of the vaccine every 10 years, primarily to provide durable protection against tetanus.

Continue to: Varicella vaccine...

Varicella vaccine

The varicella vaccine is also one of the main components of the childhood immunization series. This live virus vaccine can be administered subcutaneously as a monovalent agent or as a quadrivalent agent in association with the MMR vaccine.

Pregnant women who do not have a well-documented history of natural infection should be tested for IgG antibody to the varicella-zoster virus at the time of their first prenatal appointment. Interestingly, approximately 70% of patients with an uncertain history actually have immunity when tested. If the patient lacks immunity, she should be vaccinated immediately postpartum.16,17 The vaccine should be administered in a 2-dose series at time zero and then 4 to 8 weeks later. Patients should adhere to secure contraception from the time of the first dose until 1 month after the second dose. The cost of each dose of the vaccine is approximately $145.

Adverse effects of vaccination

All vaccines have many of the same side effects. The most common is simply a reaction at the site of injection, characterized by pain, increased warmth, erythema, swelling, and tenderness. Other common side effects include systemic manifestations, such as low-grade fever, nausea and vomiting, malaise, fatigue, headache, lymphadenopathy, myalgias, and arthralgias. Some vaccines, notably varicella, herpes zoster, measles, and rubella may cause a disseminated rash. Most of these minor side effects are easily managed by rest, hydration, and administration of an analgesic such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. More serious side effects include rare complications such as anaphylaxis, Bell palsy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and venous thromboembolism (Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine). Any of the vaccines discussed above should not be given, or given only with extreme caution, to an individual who has experienced any of these reactions with a previous vaccine.

Barriers to vaccination

Although the vaccines reviewed above are highly effective in preventing serious illness in recipients, the medical profession’s “report card” in ensuring adherence with vaccine protocols is not optimal. In fact, it probably merits a grade no higher than C+, with vaccination rates in the range of 50% to 70%.

One of the major barriers to vaccination is lack of detailed information about vaccine efficacy and safety on the part of both provider and patient. Another is the problem of misinformation (eg, the persistent belief on the part of some individuals that vaccines may cause a serious problem, such as autism).18,19 Another important barrier to widespread vaccination is the logistical problem associated with proper scheduling of multidose regimens (such as those for hepatitis A and B, varicella, and COVID-19). A final barrier, and in my own university-based practice, the most important obstacle is the expense of vaccination. Most, but not all, private insurance companies provide coverage for vaccines approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the US Preventive Services Task Force. However, public insurance agencies often provide disappointingly inconsistent coverage for essential vaccines.

By keeping well informed about the most recent public health recommendations for vaccinations for adults and by leading important initiatives within our own practices, we should be able to overcome the first 3 barriers listed above. For example, Morgan and colleagues20 recently achieved a 97% success rate with Tdap administration in pregnancy by placing a best-practice alert in the patients’ electronic medical records. Surmounting the final barrier will require intense effort on the part of individual practitioners and professional organizations to advocate for coverage for essential vaccinations for our patients.

CASE Resolved

This patient was raised in an area of the world where her family did not have easy access to medical care. Accordingly, she did not receive the usual childhood vaccines, such as measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, hepatitis B, and almost certainly, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap), and the HPV vaccine. The MMR vaccine and the varicella vaccine are live virus vaccines and should not be given during pregnancy. However, these vaccines should be administered postpartum, and the patient should be instructed to practice secure contraception for a minimum of 1 month following vaccination. She also should be offered the HPV vaccine postpartum. During pregnancy, she definitely should receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine series, the influenza vaccine, and Tdap. If her present living conditions place her at risk for hepatitis A, she also should be vaccinated against this illness. ●

- Rasmussen SA, Kelley CF, Horton JP, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines and pregnancy. What obstetricians need to know. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:408-414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004290.

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers RT, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2273-2282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00669-8.

- Omer SB. Maternal immunization. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1256-1267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1509044.

- Dionne-Odom J, Tita AT, Silverman NS. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series: #38: hepatitis B in pregnancy screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.100.

- Yawetz S. Immunizations during pregnancy. UpToDate, January 15, 2021.

- Cunningham Al, Lal H, Kovac M, et al. Efficacy of the herpes zoster subunit vaccine in adults 70 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2016:375:1019-1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603800.

- Albrecht MA, Levin MJ. Vaccination for the prevention of shingles (herpes zoster). UpToDate, July 6, 2020.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Human papillomavirus vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:699-705. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200609000-00047.

- Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy-related mortality resulting from influenza in the United States during the 2009-2010 pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:486-490. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000996.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:648-651. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000453599.11566.11.

- Scheller NM, Pasternak B, Molgaard-Nielsen D, et al. Quadrivalent HPV vaccination and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1223-1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612296.

- Moumne O, Duff P. Treatment and prevention of pneumococcal infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:781-789. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000451.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Update on immunization and pregnancy: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:668-669. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002293.

- Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, et al. Safety of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis and influenza vaccinations in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1069-1074. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001066.

- Duff P. Varicella in pregnancy: five priorities for clinicians. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;1:163-165. doi: 10.1155/S1064744994000013.

- Duff P. Varicella vaccine. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1996;4:63-65. doi: 10.1155/S1064744996000142.

- Desmond A, Offit PA. On the shoulders of giants--from Jenner's cowpox to mRNA COVID vaccines. N Engl. J Med. 2021;384:1081-1083. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2034334.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM. The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010594.

- Morgan JL, Baggari SR, Chung W, et al. Association of a best-practice alert and prenatal administration with tetanus toxoid, reduced diptheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccination rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:333-337. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000975.

CASE 1st prenatal appointment for young, pregnant migrant

A 21-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks’ gestation recently immigrated to the United States from an impoverished rural area of Southeast Asia. On the first prenatal appointment, she is noted to have no evidence of immunity to rubella, measles, or varicella. Her hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody tests are negative. She also has negative test results for gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV infection. Her pap test is negative.

- What vaccinations should this patient receive during her pregnancy?

- What additional vaccinations are indicated postpartum?

Preventive vaccinations: What to know

As ObGyns, we serve as the primary care physician for many women throughout their early and middle decades of life. Accordingly, we have an obligation to be well informed about preventive health services such as vaccinations. The purpose of this article is to review the principal vaccines with which ObGyns should be familiar. I will discuss the vaccines in alphabetical order and then focus on the indications and timing for each vaccine and the relative cost of each immunization. Key points are summarized in the TABLE.

COVID-19 vaccine

In the latter part of 2020 and early part of 2021, three COVID-19 vaccines received emergency use authorization (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for individuals 16 years of age and older (Pfizer-BioNTech) and 18 years of age and older (Moderna and Johnson & Johnson).1 The cost of their administration is borne by the federal government. Two of the vaccines are mRNA agents—Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech. Both are administered in a 2-dose series, separated by 4 and 3 weeks, respectively. The efficacy of these vaccines in preventing serious or critical illness approaches 95%. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has now been fully FDA approved for administration to individuals older than age 16, with EUA for those down to age 12. Full approval of the Moderna vaccine will not be far behind. Because of some evidence suggesting waning immunity over time and because of growing concerns about the increased transmissibility of the delta variant of the virus, the FDA has been strongly considering a recommendation for a third (booster) dose of each of these vaccines, administered 8 months after the second dose for all eligible Americans. On September 17, 2021, the FDA advisory committee recommended a booster for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for people older than age 65 and for those over the age of 16 at high risk for severe COVID-19. Several days later, full FDA approval was granted for this recommendation. Subsequently, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) included health care workers and pregnant women in the group for whom the booster is recommended.

The third vaccine formulation is the Johnson & Johnson DNA vaccine, which is prepared with a human adenovirus vector. This vaccine is administered in a single intramuscular dose and has a reported efficacy of 66% to 85%, though it may approach 95% in preventing critical illness. The FDA is expected to announce decisions about booster doses for the Johnson & Johnson and Moderna vaccines in the coming weeks.

Although initial trials of the COVID-19vaccines excluded pregnant and lactating women, the vaccines are safe in pregnancy or postpartum. In fact the vaccines do not contain either a killed or attenuated viral particle that is capable of transmitting infection. Therefore, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine now support routine immunization during pregnancy.

A recent report by Shimabukuro and colleagues2 demonstrated that the risk of vaccine-related complications in pregnant women receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccines was no different than in nonpregnant patients and that there was no evidence of teratogenic effects. The trial included more than 35,000 pregnant women; 2.3% were vaccinated in the periconception period, 28.6% in the first trimester, 43.3% in the second trimester, and 25.7% in the third trimester. Given this, and in light of isolated reports of unusual thromboembolic complications associated with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, I strongly recommend use of either the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in our prenatal and postpartum patients.

Continue to: Hepatitis A vaccine...

Hepatitis A vaccine

The hepatitis A vaccine is an inactivated vaccine and is safe for use in pregnancy. It is available in two monovalent preparations—Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co.) and is administered in a 2-dose intramuscular injection at time zero and 6 to 12 months later.3 The vaccine is also available in a bivalent form with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine—Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline). When administered in this form, the vaccine should be given at time zero, 1 month, and 6 months. The wholesale cost of the monovalent vaccine is $66 to $119, depending upon whether the provider uses a multi-dose or a single-dose vial. The cost of Twinrix is $149.

The hepatitis A vaccine is indicated for select pregnant and nonpregnant patients:

- international travelers

- intravenous drug users

- those with occupational exposure (eg, individuals who work in a primate laboratory)

- residents and staff in chronic care facilities

- individuals with chronic liver disease

- individuals with clotting factor disorders

- residents in endemic areas.

Hepatitis B vaccine

The hepatitis B vaccine is a recombinant vaccine that contains an inactivated portion of the hepatitis B surface antigen. It was originally produced in two monovalent formulations: Engerix B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax-HB (Merck & Co.). These original formulations are given in a 3-dose series at time zero, 1 month, and 6 months. Recently, a new and more potent formulation was introduced into clinical practice. Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies Co.) is also a recombinant vaccine that contains a boosting adjuvant. It is programed to be administered in a 2-dose series at time zero and 1 month.4-6

The wholesale cost of the monovalent vaccines varies from $60 to $173, depending upon use of a multi-dose vial versus a single-use vial. The cost of Heplisav-B varies from $146 to $173, depending upon use of a prefilled syringe versus a single-dose vial.

Although the hepatitis B vaccine should be part of the childhood immunization series, it also should be administered to any pregnant woman who has not been vaccinated previously or who does not already have evidence of immunity as a result of natural infection.

Continue to: Herpes zoster vaccine...

Herpes zoster vaccine

Herpes zoster infection (shingles) can be a particularly disabling condition in older patients and results from reactivation of a latent varicella-zoster infection. Shingles can cause extremely painful skin lesions, threaten the patient’s vision, and result in long-lasting postherpetic neuralgia. Both cellular and hormonal immunity are essential to protect against recurrent infection.

The original herpes zoster vaccine (Zoster Vaccine Live; ZVL, Zostavax) is no longer produced in the United States because it is not as effective as the newer vaccine—Recombinant Zoster Vaccine (Shingrix, GlaxoSmithKline).7,8 The antigen in the new vaccine is a component of the surface glycoprotein E, and it is combined with an adjuvant to enhance immunoreactivity. The vaccine is given intramuscularly in two doses at time zero and again at 2 to 6 months and is indicated for all individuals >50 years, including those who may have had an episode of shingles. This newer vaccine is 97% effective in patients >50 years and 90% effective in patients >70. The wholesale cost of each injection is about $160.

Human papillomavirus vaccine

The HPV vaccine (Gardasil-9, Merck & Co.) is a recombinant 9-valent vaccine directed against the human papillomavirus. It induces immunity to serotypes 6 and 11 (which cause 90% of genital warts), 16 and 18 (which cause 80% of genital cancers), and 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (viral strains that are responsible for both genital and oropharyngeal cancers). The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in a 3-dose series at time zero, 1-2 months, and 6 months. The principal target groups for the vaccine are males and females, ages 9 to 45 years. Ideally, children of both sexes should receive this vaccine prior to the onset of sexual activity. The wholesale cost of each vaccine injection is approximately $222.9

Influenza vaccine

The inactivated, intramuscular flu vaccine is recommended for anyone over age 2, including pregnant women. Although pregnant women are not more likely to acquire flu compared with those who are not pregnant, if they do become infected, they are likely to become more seriously ill, with higher mortality. Accordingly, all pregnant women should receive, in any trimester, the inactivated flu vaccine beginning in the late summer and early fall of each year and extending through March of the next year.10,11

Multiple formulations of the inactivated vaccine are marketed, all targeting two strains of influenza A and two strains of influenza B. The components of the vaccine vary each year as scientists try to match the new vaccine with the most highly prevalent strains in the previous flu season. The vaccine should be administered in a single intramuscular dose. The cost varies from approximately $20 to $70.

The intranasal influenza vaccine is a live virus vaccine that is intended primarily for children and should not be administered in pregnancy. In addition, there is a higher dose of the inactivated quadrivalent vaccine that is available for administration to patients over age 65. This higher dose is more likely to cause adverse effects and is not indicated in pregnancy.

Continue to: Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (MMR)...

Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (MMR)

The MMR is a standard component of the childhood vaccination series. The trivalent preparation is a live, attenuated vaccine that is typically given subcutaneously in a 2-dose series. The first dose is administered at age 12-15 months, and the second dose at age 4-6 years. The vaccine is highly immunogenic, with vaccine-induced immunity usually life-long. In some patients, however, immunity wanes over time. Accordingly, all pregnant women should be screened for immunity to rubella since, of the 3, this infection poses the greatest risk to the fetus. Women who do not have evidence of immunity should be advised to avoid contact with children who may have a viral exanthem. They should then receive a booster dose of the vaccine immediately postpartum and should practice secure contraception for 1 month. The vaccine cost is approximately $60.

Pneumococcal vaccine

The inactivated pneumococcal vaccine is produced in two forms, both of which are safe for administration in pregnancy.12 The original vaccine, introduced in 1983, was PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23, Merck & Co), a 23-serovalent vaccine that was intended primarily for adults. This vaccine is administered in a single subcutaneous or intramuscular dose. The newest vaccine, introduced in 2010, is PCV13 (Prevnar 13, Pfizer Inc), a 13-serovalent vaccine. It was intended primarily for children, in whom it is administered in a 4-dose series beginning at 6 to 8 weeks of age. The cost of the former is approximately $98 to $120; the cost of the latter is $228.

Vaccination against pneumococcal infection is routinely indicated for those older than the age of 65 and for the following at-risk patients, including those who are pregnant11:

- individuals who have had a splenectomy or who have a medical illness that produces functional asplenia (eg, sickle cell anemia)

- individuals with chronic cardiac, pulmonic, hepatic, or renal disease

- individuals with immunosuppressive conditions such as HIV infection or a disseminated malignancy

- individuals who have a cochlear implant

- individuals who have a chronic leak of cerebrospinal fluid.

The recommendations for timing of these 2 vaccines in adults can initially appear confusing. Put most simply, if a high-risk patient first receives the PCV13 vaccine, she should receive the PPSV23 vaccine in about 8 weeks. The PPSV23 vaccine should be repeated in 5 years. If an at-risk patient initially receives the PPSV23 vaccine, the PCV13 vaccine should be given 1 year later.12

Tdap vaccine

The Tdap vaccine contains tetanus toxoid, reduced diptheria toxoid, and an acellular component of the pertussis bacterium. Although it has long been part of the childhood vaccinations series, immunity to each component, particularly pertussis, tends to wane over time.

Pertussis poses a serious risk to the health of the pregnant woman and the newborn infant. Accordingly, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), CDC, and the ACOG now advise administration of a booster dose of this vaccine in the early third trimester of each pregnancy.13-15 The vaccine should be administered as a single intramuscular injection. The approximate cost of the vaccine is $64 to $71, depending upon whether the provider uses a single-dose vial or a single-dose prefilled syringe. In nonpregnant patients, the ACIP currently recommends administration of a booster dose of the vaccine every 10 years, primarily to provide durable protection against tetanus.

Continue to: Varicella vaccine...

Varicella vaccine

The varicella vaccine is also one of the main components of the childhood immunization series. This live virus vaccine can be administered subcutaneously as a monovalent agent or as a quadrivalent agent in association with the MMR vaccine.

Pregnant women who do not have a well-documented history of natural infection should be tested for IgG antibody to the varicella-zoster virus at the time of their first prenatal appointment. Interestingly, approximately 70% of patients with an uncertain history actually have immunity when tested. If the patient lacks immunity, she should be vaccinated immediately postpartum.16,17 The vaccine should be administered in a 2-dose series at time zero and then 4 to 8 weeks later. Patients should adhere to secure contraception from the time of the first dose until 1 month after the second dose. The cost of each dose of the vaccine is approximately $145.

Adverse effects of vaccination

All vaccines have many of the same side effects. The most common is simply a reaction at the site of injection, characterized by pain, increased warmth, erythema, swelling, and tenderness. Other common side effects include systemic manifestations, such as low-grade fever, nausea and vomiting, malaise, fatigue, headache, lymphadenopathy, myalgias, and arthralgias. Some vaccines, notably varicella, herpes zoster, measles, and rubella may cause a disseminated rash. Most of these minor side effects are easily managed by rest, hydration, and administration of an analgesic such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. More serious side effects include rare complications such as anaphylaxis, Bell palsy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and venous thromboembolism (Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine). Any of the vaccines discussed above should not be given, or given only with extreme caution, to an individual who has experienced any of these reactions with a previous vaccine.

Barriers to vaccination

Although the vaccines reviewed above are highly effective in preventing serious illness in recipients, the medical profession’s “report card” in ensuring adherence with vaccine protocols is not optimal. In fact, it probably merits a grade no higher than C+, with vaccination rates in the range of 50% to 70%.

One of the major barriers to vaccination is lack of detailed information about vaccine efficacy and safety on the part of both provider and patient. Another is the problem of misinformation (eg, the persistent belief on the part of some individuals that vaccines may cause a serious problem, such as autism).18,19 Another important barrier to widespread vaccination is the logistical problem associated with proper scheduling of multidose regimens (such as those for hepatitis A and B, varicella, and COVID-19). A final barrier, and in my own university-based practice, the most important obstacle is the expense of vaccination. Most, but not all, private insurance companies provide coverage for vaccines approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the US Preventive Services Task Force. However, public insurance agencies often provide disappointingly inconsistent coverage for essential vaccines.

By keeping well informed about the most recent public health recommendations for vaccinations for adults and by leading important initiatives within our own practices, we should be able to overcome the first 3 barriers listed above. For example, Morgan and colleagues20 recently achieved a 97% success rate with Tdap administration in pregnancy by placing a best-practice alert in the patients’ electronic medical records. Surmounting the final barrier will require intense effort on the part of individual practitioners and professional organizations to advocate for coverage for essential vaccinations for our patients.

CASE Resolved

This patient was raised in an area of the world where her family did not have easy access to medical care. Accordingly, she did not receive the usual childhood vaccines, such as measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, hepatitis B, and almost certainly, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap), and the HPV vaccine. The MMR vaccine and the varicella vaccine are live virus vaccines and should not be given during pregnancy. However, these vaccines should be administered postpartum, and the patient should be instructed to practice secure contraception for a minimum of 1 month following vaccination. She also should be offered the HPV vaccine postpartum. During pregnancy, she definitely should receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine series, the influenza vaccine, and Tdap. If her present living conditions place her at risk for hepatitis A, she also should be vaccinated against this illness. ●

CASE 1st prenatal appointment for young, pregnant migrant

A 21-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks’ gestation recently immigrated to the United States from an impoverished rural area of Southeast Asia. On the first prenatal appointment, she is noted to have no evidence of immunity to rubella, measles, or varicella. Her hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody tests are negative. She also has negative test results for gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV infection. Her pap test is negative.

- What vaccinations should this patient receive during her pregnancy?

- What additional vaccinations are indicated postpartum?

Preventive vaccinations: What to know

As ObGyns, we serve as the primary care physician for many women throughout their early and middle decades of life. Accordingly, we have an obligation to be well informed about preventive health services such as vaccinations. The purpose of this article is to review the principal vaccines with which ObGyns should be familiar. I will discuss the vaccines in alphabetical order and then focus on the indications and timing for each vaccine and the relative cost of each immunization. Key points are summarized in the TABLE.

COVID-19 vaccine

In the latter part of 2020 and early part of 2021, three COVID-19 vaccines received emergency use authorization (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for individuals 16 years of age and older (Pfizer-BioNTech) and 18 years of age and older (Moderna and Johnson & Johnson).1 The cost of their administration is borne by the federal government. Two of the vaccines are mRNA agents—Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech. Both are administered in a 2-dose series, separated by 4 and 3 weeks, respectively. The efficacy of these vaccines in preventing serious or critical illness approaches 95%. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has now been fully FDA approved for administration to individuals older than age 16, with EUA for those down to age 12. Full approval of the Moderna vaccine will not be far behind. Because of some evidence suggesting waning immunity over time and because of growing concerns about the increased transmissibility of the delta variant of the virus, the FDA has been strongly considering a recommendation for a third (booster) dose of each of these vaccines, administered 8 months after the second dose for all eligible Americans. On September 17, 2021, the FDA advisory committee recommended a booster for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for people older than age 65 and for those over the age of 16 at high risk for severe COVID-19. Several days later, full FDA approval was granted for this recommendation. Subsequently, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) included health care workers and pregnant women in the group for whom the booster is recommended.

The third vaccine formulation is the Johnson & Johnson DNA vaccine, which is prepared with a human adenovirus vector. This vaccine is administered in a single intramuscular dose and has a reported efficacy of 66% to 85%, though it may approach 95% in preventing critical illness. The FDA is expected to announce decisions about booster doses for the Johnson & Johnson and Moderna vaccines in the coming weeks.

Although initial trials of the COVID-19vaccines excluded pregnant and lactating women, the vaccines are safe in pregnancy or postpartum. In fact the vaccines do not contain either a killed or attenuated viral particle that is capable of transmitting infection. Therefore, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine now support routine immunization during pregnancy.

A recent report by Shimabukuro and colleagues2 demonstrated that the risk of vaccine-related complications in pregnant women receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccines was no different than in nonpregnant patients and that there was no evidence of teratogenic effects. The trial included more than 35,000 pregnant women; 2.3% were vaccinated in the periconception period, 28.6% in the first trimester, 43.3% in the second trimester, and 25.7% in the third trimester. Given this, and in light of isolated reports of unusual thromboembolic complications associated with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, I strongly recommend use of either the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in our prenatal and postpartum patients.

Continue to: Hepatitis A vaccine...

Hepatitis A vaccine

The hepatitis A vaccine is an inactivated vaccine and is safe for use in pregnancy. It is available in two monovalent preparations—Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co.) and is administered in a 2-dose intramuscular injection at time zero and 6 to 12 months later.3 The vaccine is also available in a bivalent form with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine—Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline). When administered in this form, the vaccine should be given at time zero, 1 month, and 6 months. The wholesale cost of the monovalent vaccine is $66 to $119, depending upon whether the provider uses a multi-dose or a single-dose vial. The cost of Twinrix is $149.

The hepatitis A vaccine is indicated for select pregnant and nonpregnant patients:

- international travelers

- intravenous drug users

- those with occupational exposure (eg, individuals who work in a primate laboratory)

- residents and staff in chronic care facilities

- individuals with chronic liver disease

- individuals with clotting factor disorders

- residents in endemic areas.

Hepatitis B vaccine

The hepatitis B vaccine is a recombinant vaccine that contains an inactivated portion of the hepatitis B surface antigen. It was originally produced in two monovalent formulations: Engerix B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax-HB (Merck & Co.). These original formulations are given in a 3-dose series at time zero, 1 month, and 6 months. Recently, a new and more potent formulation was introduced into clinical practice. Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies Co.) is also a recombinant vaccine that contains a boosting adjuvant. It is programed to be administered in a 2-dose series at time zero and 1 month.4-6

The wholesale cost of the monovalent vaccines varies from $60 to $173, depending upon use of a multi-dose vial versus a single-use vial. The cost of Heplisav-B varies from $146 to $173, depending upon use of a prefilled syringe versus a single-dose vial.

Although the hepatitis B vaccine should be part of the childhood immunization series, it also should be administered to any pregnant woman who has not been vaccinated previously or who does not already have evidence of immunity as a result of natural infection.

Continue to: Herpes zoster vaccine...

Herpes zoster vaccine

Herpes zoster infection (shingles) can be a particularly disabling condition in older patients and results from reactivation of a latent varicella-zoster infection. Shingles can cause extremely painful skin lesions, threaten the patient’s vision, and result in long-lasting postherpetic neuralgia. Both cellular and hormonal immunity are essential to protect against recurrent infection.

The original herpes zoster vaccine (Zoster Vaccine Live; ZVL, Zostavax) is no longer produced in the United States because it is not as effective as the newer vaccine—Recombinant Zoster Vaccine (Shingrix, GlaxoSmithKline).7,8 The antigen in the new vaccine is a component of the surface glycoprotein E, and it is combined with an adjuvant to enhance immunoreactivity. The vaccine is given intramuscularly in two doses at time zero and again at 2 to 6 months and is indicated for all individuals >50 years, including those who may have had an episode of shingles. This newer vaccine is 97% effective in patients >50 years and 90% effective in patients >70. The wholesale cost of each injection is about $160.

Human papillomavirus vaccine

The HPV vaccine (Gardasil-9, Merck & Co.) is a recombinant 9-valent vaccine directed against the human papillomavirus. It induces immunity to serotypes 6 and 11 (which cause 90% of genital warts), 16 and 18 (which cause 80% of genital cancers), and 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (viral strains that are responsible for both genital and oropharyngeal cancers). The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in a 3-dose series at time zero, 1-2 months, and 6 months. The principal target groups for the vaccine are males and females, ages 9 to 45 years. Ideally, children of both sexes should receive this vaccine prior to the onset of sexual activity. The wholesale cost of each vaccine injection is approximately $222.9

Influenza vaccine

The inactivated, intramuscular flu vaccine is recommended for anyone over age 2, including pregnant women. Although pregnant women are not more likely to acquire flu compared with those who are not pregnant, if they do become infected, they are likely to become more seriously ill, with higher mortality. Accordingly, all pregnant women should receive, in any trimester, the inactivated flu vaccine beginning in the late summer and early fall of each year and extending through March of the next year.10,11

Multiple formulations of the inactivated vaccine are marketed, all targeting two strains of influenza A and two strains of influenza B. The components of the vaccine vary each year as scientists try to match the new vaccine with the most highly prevalent strains in the previous flu season. The vaccine should be administered in a single intramuscular dose. The cost varies from approximately $20 to $70.

The intranasal influenza vaccine is a live virus vaccine that is intended primarily for children and should not be administered in pregnancy. In addition, there is a higher dose of the inactivated quadrivalent vaccine that is available for administration to patients over age 65. This higher dose is more likely to cause adverse effects and is not indicated in pregnancy.

Continue to: Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (MMR)...

Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (MMR)

The MMR is a standard component of the childhood vaccination series. The trivalent preparation is a live, attenuated vaccine that is typically given subcutaneously in a 2-dose series. The first dose is administered at age 12-15 months, and the second dose at age 4-6 years. The vaccine is highly immunogenic, with vaccine-induced immunity usually life-long. In some patients, however, immunity wanes over time. Accordingly, all pregnant women should be screened for immunity to rubella since, of the 3, this infection poses the greatest risk to the fetus. Women who do not have evidence of immunity should be advised to avoid contact with children who may have a viral exanthem. They should then receive a booster dose of the vaccine immediately postpartum and should practice secure contraception for 1 month. The vaccine cost is approximately $60.

Pneumococcal vaccine

The inactivated pneumococcal vaccine is produced in two forms, both of which are safe for administration in pregnancy.12 The original vaccine, introduced in 1983, was PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23, Merck & Co), a 23-serovalent vaccine that was intended primarily for adults. This vaccine is administered in a single subcutaneous or intramuscular dose. The newest vaccine, introduced in 2010, is PCV13 (Prevnar 13, Pfizer Inc), a 13-serovalent vaccine. It was intended primarily for children, in whom it is administered in a 4-dose series beginning at 6 to 8 weeks of age. The cost of the former is approximately $98 to $120; the cost of the latter is $228.

Vaccination against pneumococcal infection is routinely indicated for those older than the age of 65 and for the following at-risk patients, including those who are pregnant11:

- individuals who have had a splenectomy or who have a medical illness that produces functional asplenia (eg, sickle cell anemia)

- individuals with chronic cardiac, pulmonic, hepatic, or renal disease

- individuals with immunosuppressive conditions such as HIV infection or a disseminated malignancy

- individuals who have a cochlear implant

- individuals who have a chronic leak of cerebrospinal fluid.

The recommendations for timing of these 2 vaccines in adults can initially appear confusing. Put most simply, if a high-risk patient first receives the PCV13 vaccine, she should receive the PPSV23 vaccine in about 8 weeks. The PPSV23 vaccine should be repeated in 5 years. If an at-risk patient initially receives the PPSV23 vaccine, the PCV13 vaccine should be given 1 year later.12

Tdap vaccine

The Tdap vaccine contains tetanus toxoid, reduced diptheria toxoid, and an acellular component of the pertussis bacterium. Although it has long been part of the childhood vaccinations series, immunity to each component, particularly pertussis, tends to wane over time.

Pertussis poses a serious risk to the health of the pregnant woman and the newborn infant. Accordingly, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), CDC, and the ACOG now advise administration of a booster dose of this vaccine in the early third trimester of each pregnancy.13-15 The vaccine should be administered as a single intramuscular injection. The approximate cost of the vaccine is $64 to $71, depending upon whether the provider uses a single-dose vial or a single-dose prefilled syringe. In nonpregnant patients, the ACIP currently recommends administration of a booster dose of the vaccine every 10 years, primarily to provide durable protection against tetanus.

Continue to: Varicella vaccine...

Varicella vaccine

The varicella vaccine is also one of the main components of the childhood immunization series. This live virus vaccine can be administered subcutaneously as a monovalent agent or as a quadrivalent agent in association with the MMR vaccine.

Pregnant women who do not have a well-documented history of natural infection should be tested for IgG antibody to the varicella-zoster virus at the time of their first prenatal appointment. Interestingly, approximately 70% of patients with an uncertain history actually have immunity when tested. If the patient lacks immunity, she should be vaccinated immediately postpartum.16,17 The vaccine should be administered in a 2-dose series at time zero and then 4 to 8 weeks later. Patients should adhere to secure contraception from the time of the first dose until 1 month after the second dose. The cost of each dose of the vaccine is approximately $145.

Adverse effects of vaccination

All vaccines have many of the same side effects. The most common is simply a reaction at the site of injection, characterized by pain, increased warmth, erythema, swelling, and tenderness. Other common side effects include systemic manifestations, such as low-grade fever, nausea and vomiting, malaise, fatigue, headache, lymphadenopathy, myalgias, and arthralgias. Some vaccines, notably varicella, herpes zoster, measles, and rubella may cause a disseminated rash. Most of these minor side effects are easily managed by rest, hydration, and administration of an analgesic such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. More serious side effects include rare complications such as anaphylaxis, Bell palsy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and venous thromboembolism (Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine). Any of the vaccines discussed above should not be given, or given only with extreme caution, to an individual who has experienced any of these reactions with a previous vaccine.

Barriers to vaccination

Although the vaccines reviewed above are highly effective in preventing serious illness in recipients, the medical profession’s “report card” in ensuring adherence with vaccine protocols is not optimal. In fact, it probably merits a grade no higher than C+, with vaccination rates in the range of 50% to 70%.

One of the major barriers to vaccination is lack of detailed information about vaccine efficacy and safety on the part of both provider and patient. Another is the problem of misinformation (eg, the persistent belief on the part of some individuals that vaccines may cause a serious problem, such as autism).18,19 Another important barrier to widespread vaccination is the logistical problem associated with proper scheduling of multidose regimens (such as those for hepatitis A and B, varicella, and COVID-19). A final barrier, and in my own university-based practice, the most important obstacle is the expense of vaccination. Most, but not all, private insurance companies provide coverage for vaccines approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the US Preventive Services Task Force. However, public insurance agencies often provide disappointingly inconsistent coverage for essential vaccines.

By keeping well informed about the most recent public health recommendations for vaccinations for adults and by leading important initiatives within our own practices, we should be able to overcome the first 3 barriers listed above. For example, Morgan and colleagues20 recently achieved a 97% success rate with Tdap administration in pregnancy by placing a best-practice alert in the patients’ electronic medical records. Surmounting the final barrier will require intense effort on the part of individual practitioners and professional organizations to advocate for coverage for essential vaccinations for our patients.

CASE Resolved

This patient was raised in an area of the world where her family did not have easy access to medical care. Accordingly, she did not receive the usual childhood vaccines, such as measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, hepatitis B, and almost certainly, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap), and the HPV vaccine. The MMR vaccine and the varicella vaccine are live virus vaccines and should not be given during pregnancy. However, these vaccines should be administered postpartum, and the patient should be instructed to practice secure contraception for a minimum of 1 month following vaccination. She also should be offered the HPV vaccine postpartum. During pregnancy, she definitely should receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine series, the influenza vaccine, and Tdap. If her present living conditions place her at risk for hepatitis A, she also should be vaccinated against this illness. ●

- Rasmussen SA, Kelley CF, Horton JP, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines and pregnancy. What obstetricians need to know. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:408-414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004290.

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers RT, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2273-2282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00669-8.

- Omer SB. Maternal immunization. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1256-1267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1509044.

- Dionne-Odom J, Tita AT, Silverman NS. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series: #38: hepatitis B in pregnancy screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.100.

- Yawetz S. Immunizations during pregnancy. UpToDate, January 15, 2021.

- Cunningham Al, Lal H, Kovac M, et al. Efficacy of the herpes zoster subunit vaccine in adults 70 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2016:375:1019-1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603800.

- Albrecht MA, Levin MJ. Vaccination for the prevention of shingles (herpes zoster). UpToDate, July 6, 2020.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Human papillomavirus vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:699-705. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200609000-00047.

- Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy-related mortality resulting from influenza in the United States during the 2009-2010 pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:486-490. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000996.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:648-651. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000453599.11566.11.

- Scheller NM, Pasternak B, Molgaard-Nielsen D, et al. Quadrivalent HPV vaccination and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1223-1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612296.

- Moumne O, Duff P. Treatment and prevention of pneumococcal infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:781-789. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000451.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Update on immunization and pregnancy: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:668-669. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002293.

- Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, et al. Safety of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis and influenza vaccinations in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1069-1074. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001066.

- Duff P. Varicella in pregnancy: five priorities for clinicians. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;1:163-165. doi: 10.1155/S1064744994000013.

- Duff P. Varicella vaccine. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1996;4:63-65. doi: 10.1155/S1064744996000142.

- Desmond A, Offit PA. On the shoulders of giants--from Jenner's cowpox to mRNA COVID vaccines. N Engl. J Med. 2021;384:1081-1083. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2034334.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM. The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010594.

- Morgan JL, Baggari SR, Chung W, et al. Association of a best-practice alert and prenatal administration with tetanus toxoid, reduced diptheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccination rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:333-337. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000975.

- Rasmussen SA, Kelley CF, Horton JP, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines and pregnancy. What obstetricians need to know. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:408-414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004290.

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers RT, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2273-2282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00669-8.

- Omer SB. Maternal immunization. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1256-1267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1509044.

- Dionne-Odom J, Tita AT, Silverman NS. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series: #38: hepatitis B in pregnancy screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.100.

- Yawetz S. Immunizations during pregnancy. UpToDate, January 15, 2021.

- Cunningham Al, Lal H, Kovac M, et al. Efficacy of the herpes zoster subunit vaccine in adults 70 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2016:375:1019-1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603800.

- Albrecht MA, Levin MJ. Vaccination for the prevention of shingles (herpes zoster). UpToDate, July 6, 2020.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Human papillomavirus vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:699-705. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200609000-00047.

- Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy-related mortality resulting from influenza in the United States during the 2009-2010 pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:486-490. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000996.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:648-651. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000453599.11566.11.

- Scheller NM, Pasternak B, Molgaard-Nielsen D, et al. Quadrivalent HPV vaccination and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1223-1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612296.

- Moumne O, Duff P. Treatment and prevention of pneumococcal infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:781-789. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000451.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Update on immunization and pregnancy: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:668-669. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002293.

- Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, et al. Safety of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis and influenza vaccinations in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1069-1074. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001066.

- Duff P. Varicella in pregnancy: five priorities for clinicians. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;1:163-165. doi: 10.1155/S1064744994000013.

- Duff P. Varicella vaccine. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1996;4:63-65. doi: 10.1155/S1064744996000142.

- Desmond A, Offit PA. On the shoulders of giants--from Jenner's cowpox to mRNA COVID vaccines. N Engl. J Med. 2021;384:1081-1083. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2034334.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM. The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010594.

- Morgan JL, Baggari SR, Chung W, et al. Association of a best-practice alert and prenatal administration with tetanus toxoid, reduced diptheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccination rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:333-337. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000975.

Novel and Alternative Strategies for Management of Panitumumab-Induced Hypomagnesemia

Background

Panitumumab is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibiting monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), which has an incidence of hypomagnesemia of approximately 35%. Grade 3 or 4 hypomagnesemia occurs in roughly 7% of patients, which can lead to serious complications such as seizures and arrhythmias. In one study, hypomagnesemia led to discontinuation of targeted therapy in 3% of patients. Currently, there is no standardized prophylactic strategy or treatment protocol for panitumumab-induced hypomagnesemia. In cases of refractory hypomagnesemia, it is recommended to discontinue panitumumab, even if the patient is deriving clinical benefit.

Case Report

This 59-year-old male was diagnosed with RAS wild-type mCRC and had already progressed through multiple lines of treatment. Panitumumab was initiated with good response; however, the drug was discontinued due to grade 4 hypomagnesemia, despite intravenous and oral supplementation. As the patient progressed through further lines of treatment, the decision was made to retry panitumumab. Grade 2-3 hypomagnesemia persisted throughout treatment, requiring frequent magnesium infusions. Innovative and alternative treatment options were investigated in an effort to improve his quality of life. In addition to oral and intravenous magnesium replacement, an ambulatory elastomeric pump, traditionally used for fluorouracil administration, was repurposed to deliver between 6 and 24 grams of magnesium sulfate over 24 to 72 hours. The pump was generally well tolerated with the exception of mild skin irritation around the port site, which prevented a transition to longer infusion times. The ambulatory elastomeric pump decreased the frequency of healthcare visits and improved the hypomagnesemia sufficiently to continue treatment with panitumumab, although levels did not fully normalize. A two-week trial of amiloride was also attempted to decrease renal magnesium wasting. Amiloride normalized magnesium levels but had to be discontinued due to asymptomatic hyperkalemia. This case report suggests that amiloride and magnesium replacement via ambulatory elastomeric pumps may be safe and effective treatment options for panitumumab-induced refractory hypomagnesemia in mCRC, potentially improving quality of life and allowing beneficial anti-cancer treatments to continue. Future studies should further evaluate optimization of amiloride and intravenous magnesium replacement via ambulatory elastomeric pump.

Background

Panitumumab is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibiting monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), which has an incidence of hypomagnesemia of approximately 35%. Grade 3 or 4 hypomagnesemia occurs in roughly 7% of patients, which can lead to serious complications such as seizures and arrhythmias. In one study, hypomagnesemia led to discontinuation of targeted therapy in 3% of patients. Currently, there is no standardized prophylactic strategy or treatment protocol for panitumumab-induced hypomagnesemia. In cases of refractory hypomagnesemia, it is recommended to discontinue panitumumab, even if the patient is deriving clinical benefit.

Case Report

This 59-year-old male was diagnosed with RAS wild-type mCRC and had already progressed through multiple lines of treatment. Panitumumab was initiated with good response; however, the drug was discontinued due to grade 4 hypomagnesemia, despite intravenous and oral supplementation. As the patient progressed through further lines of treatment, the decision was made to retry panitumumab. Grade 2-3 hypomagnesemia persisted throughout treatment, requiring frequent magnesium infusions. Innovative and alternative treatment options were investigated in an effort to improve his quality of life. In addition to oral and intravenous magnesium replacement, an ambulatory elastomeric pump, traditionally used for fluorouracil administration, was repurposed to deliver between 6 and 24 grams of magnesium sulfate over 24 to 72 hours. The pump was generally well tolerated with the exception of mild skin irritation around the port site, which prevented a transition to longer infusion times. The ambulatory elastomeric pump decreased the frequency of healthcare visits and improved the hypomagnesemia sufficiently to continue treatment with panitumumab, although levels did not fully normalize. A two-week trial of amiloride was also attempted to decrease renal magnesium wasting. Amiloride normalized magnesium levels but had to be discontinued due to asymptomatic hyperkalemia. This case report suggests that amiloride and magnesium replacement via ambulatory elastomeric pumps may be safe and effective treatment options for panitumumab-induced refractory hypomagnesemia in mCRC, potentially improving quality of life and allowing beneficial anti-cancer treatments to continue. Future studies should further evaluate optimization of amiloride and intravenous magnesium replacement via ambulatory elastomeric pump.

Background

Panitumumab is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibiting monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), which has an incidence of hypomagnesemia of approximately 35%. Grade 3 or 4 hypomagnesemia occurs in roughly 7% of patients, which can lead to serious complications such as seizures and arrhythmias. In one study, hypomagnesemia led to discontinuation of targeted therapy in 3% of patients. Currently, there is no standardized prophylactic strategy or treatment protocol for panitumumab-induced hypomagnesemia. In cases of refractory hypomagnesemia, it is recommended to discontinue panitumumab, even if the patient is deriving clinical benefit.

Case Report

This 59-year-old male was diagnosed with RAS wild-type mCRC and had already progressed through multiple lines of treatment. Panitumumab was initiated with good response; however, the drug was discontinued due to grade 4 hypomagnesemia, despite intravenous and oral supplementation. As the patient progressed through further lines of treatment, the decision was made to retry panitumumab. Grade 2-3 hypomagnesemia persisted throughout treatment, requiring frequent magnesium infusions. Innovative and alternative treatment options were investigated in an effort to improve his quality of life. In addition to oral and intravenous magnesium replacement, an ambulatory elastomeric pump, traditionally used for fluorouracil administration, was repurposed to deliver between 6 and 24 grams of magnesium sulfate over 24 to 72 hours. The pump was generally well tolerated with the exception of mild skin irritation around the port site, which prevented a transition to longer infusion times. The ambulatory elastomeric pump decreased the frequency of healthcare visits and improved the hypomagnesemia sufficiently to continue treatment with panitumumab, although levels did not fully normalize. A two-week trial of amiloride was also attempted to decrease renal magnesium wasting. Amiloride normalized magnesium levels but had to be discontinued due to asymptomatic hyperkalemia. This case report suggests that amiloride and magnesium replacement via ambulatory elastomeric pumps may be safe and effective treatment options for panitumumab-induced refractory hypomagnesemia in mCRC, potentially improving quality of life and allowing beneficial anti-cancer treatments to continue. Future studies should further evaluate optimization of amiloride and intravenous magnesium replacement via ambulatory elastomeric pump.

The new transdermal contraceptive patch expands available contraceptive options: Does it offer protection with less VTE risk?

The first transdermal contraceptive patch was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001.1 A 2018 survey revealed that 5% of women in the United States between the ages of 15 and 49 years reported the use of a short-acting hormonal contraceptive method (ie, vaginal ring, transdermal patch, injectable) within the past month, with just 0.3% reporting the use of a transdermal patch.2 Transdermal contraceptive patches are an effective form of birth control that may be a convenient option for patients who do not want to take a daily oral contraceptive pill but want similar efficacy and tolerability. Typical failure rates of patches are similar to that of combined oral contraceptives (COCs).1,3

While transdermal hormone delivery results in less peaks and troughs of estrogen compared with COCs, the total estrogen exposure is higher than with COCs; therefore, the risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) with previously available patches is about twice as high.1 Twirla (Agile), an ethinyl estradiol (EE)/levonorgestrel (LNG) patch, delivers a low and consistent daily dose of hormones over 3 patches replaced once weekly, with no patch on the fourth week.3 Twirla contains 120 μg/day LNG and 30 μg/day EE. OrthoEvra, FDA approved in 2001 as mentioned, contains 150 μg/day norelgestromin and 35 μg/day EE.1 A reduction of the EE dose in COCs has been associated with lower risk for VTE.4

The addition of Twirla to the market offers another contraceptive option for patients who opt for a weekly, self-administered method.

How much lower is the VTE risk?

OBG

Barbara Levy, MD: The reality is we can’t designate a reduction of risk, except, in general, when the dose of ethinyl estradiol is lower, we think that the VTE risk is lower. There has not been a head-to-head comparison in a large enough population to be able to say that the risk is reduced by a certain factor. We just look at the overall exposure to estrogen and say, “In general, for VTE risk, a lower dose is a better thing for women.”

That being said, look at birth control pills, like COCs. We don’t have actual numbers to say that a 30-μg pill is this much less risky than a 35-μg pill. We just put it into a hierarchy, and that’s what we can do with the patch. We can say that, in general, lower is better for VTE risk, but no one can provide absolute numbers.

Continue to: Efficacy...

Efficacy

OBG

Dr. Levy: You have to look at the pivotal trials and look at what the efficacy was in a trial setting. In the real-world setting, the effectiveness is never quite as good as it is in a clinical trial. I think the bottom line for all of us is that combined oral contraception, meaning estrogen with progestin, is equivalently effective across the different options that are available for women. Efficacy really isn’t the factor to use to distinguish which one I’m going to pick. It is about the patient’s convenience and many other factors. But in terms of its clinical effectiveness in preventing pregnancy, from a very practical standpoint, I think we consider them all the same.

Considering route of administration

OBG

Dr. Levy: I think there’s always a benefit in having lots of choices. And for some women, being able to put a patch on once a week is much more convenient, easier to remember, and delivers a very consistent dose of hormone absorbed through the skin, which is different than taking a pill in the morning when your levels go up quickly then diminish over the day. The hormones are higher at a certain time, and then they drop off, so there might be some advantages for people who are very sensitive to swings in hormonal levels. There’s also a convenience factor, where for some people they will choose that. Other people might really dislike having a relatively large patch on their skin somewhere, or they may have skin sensitivity to the adhesive. Overall, I always think that having more options is better and individual girls/women will choose what works best for them.

Counseling tips

OBG

Dr. Levy: Like other patches that are available on the market, these are a once-a-week patch. The patch should be placed on clean, dry skin. No lotions, perfumes, or anything on the skin because you really want them to stick for the whole week, and it’s not going to stick if there’s anything oily on the skin. The first patch is placed on day 1 of a menstrual cycle, the first day of bleeding, and then changed weekly for 3 weeks. Then there’s a 7-day patch-free time in which one would expect to have a period.

In general, breakthrough bleeding was not a significant problem with the patch, but some women will have some irregular spotting and bleeding with any sort of hormonal treatment; some women may have no periods at all. In other words, the estrogen dose and progestin may be of a balance that allows the patient not to have periods. But, in general, most of the women in the trial had regular light menstrual flow during the week when their patch was not on.5

Continue to: Pricing...

Pricing

OBG

Dr. Levy: That’s a tricky question. Insurance plans through Obamacare, the Affordable Care Act, are required to cover every form of contraception. That means they must cover a patch. It doesn’t mean that they have to cover this patch. And because there are generics available of the other patch formulation, it is likely that this would be a higher tier, meaning that there may be a higher copay for someone who wanted to use Twirla versus one of the generic patches.

I can’t say that that’s universally the case, but my experience with most of the health insurance plans is that they tend to put barriers in the way for any of us to prescribe, and for women to use, brand-name products. So Twirla is new on the market; it’s a brand-name product. It may work much better for some people; and in those cases, the health care provider might have to send a letter to the insurance company saying why this one is medically necessary for a patient. There probably will be some hoops to go through for coverage without a copay. I think coverage will be there, but there may be a substantial copay because of the tier level.

OBG