User login

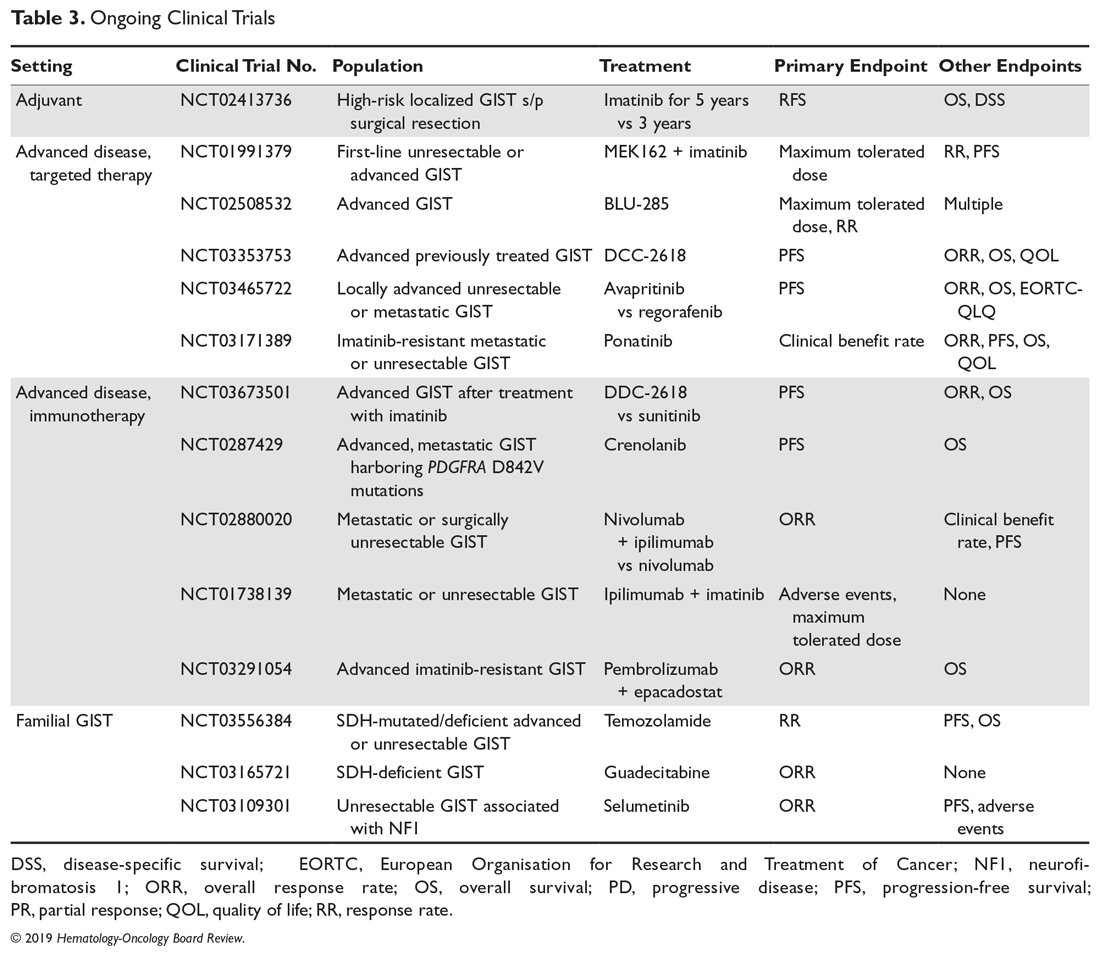

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Management of Localized Disease

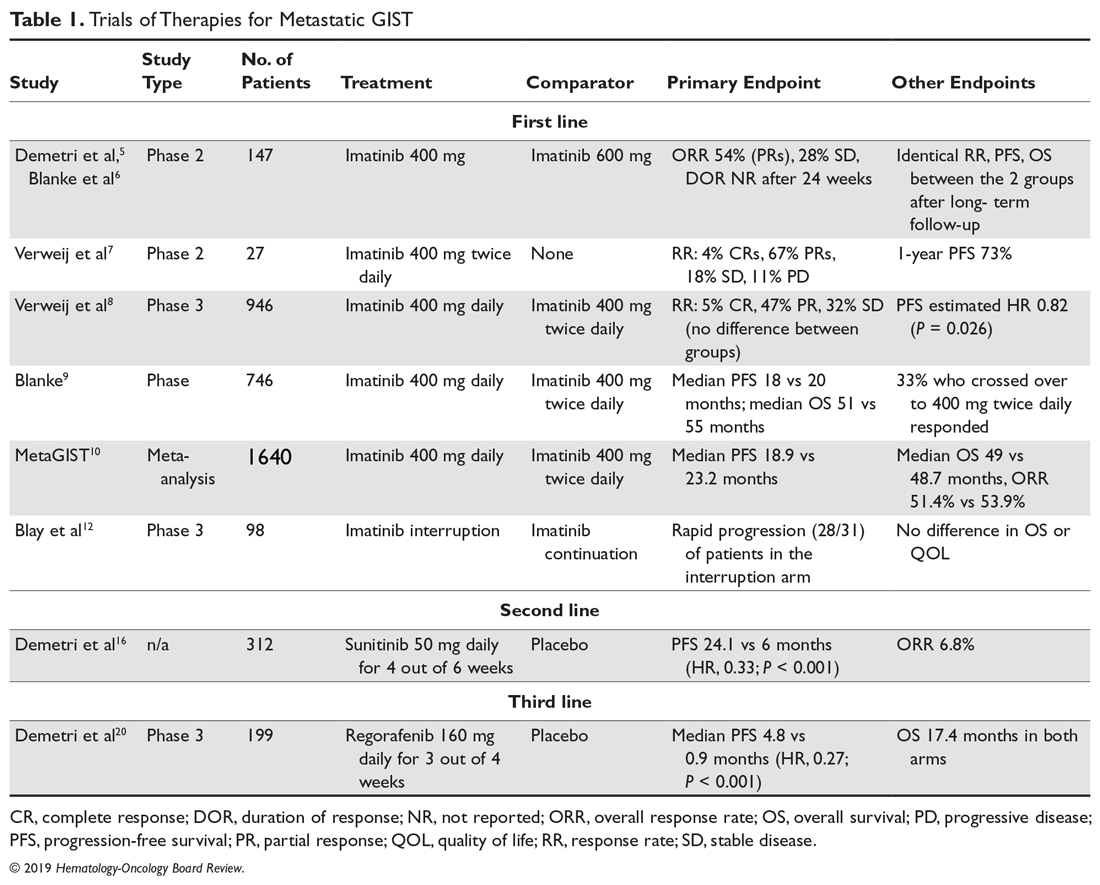

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal of the myenteric plexus. These tumors are rare, with about 1 case per 100,000 persons diagnosed in the United States annually, but may be incidentally discovered in up to 1 in 5 autopsy specimens of older adults.1,2 Epidemiologic risk factors include increasing age, with a peak incidence between age 60 and 65 years, male gender, black race, and non-Hispanic white ethnicity. Germline predisposition can also increase the risk of developing GISTs; molecular drivers of GIST include gain-of-function mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) gene, which both encode structurally similar tyrosine kinase receptors; germline mutations of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunit genes; and mutations associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.

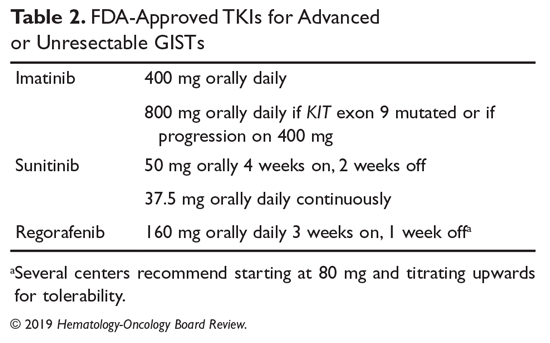

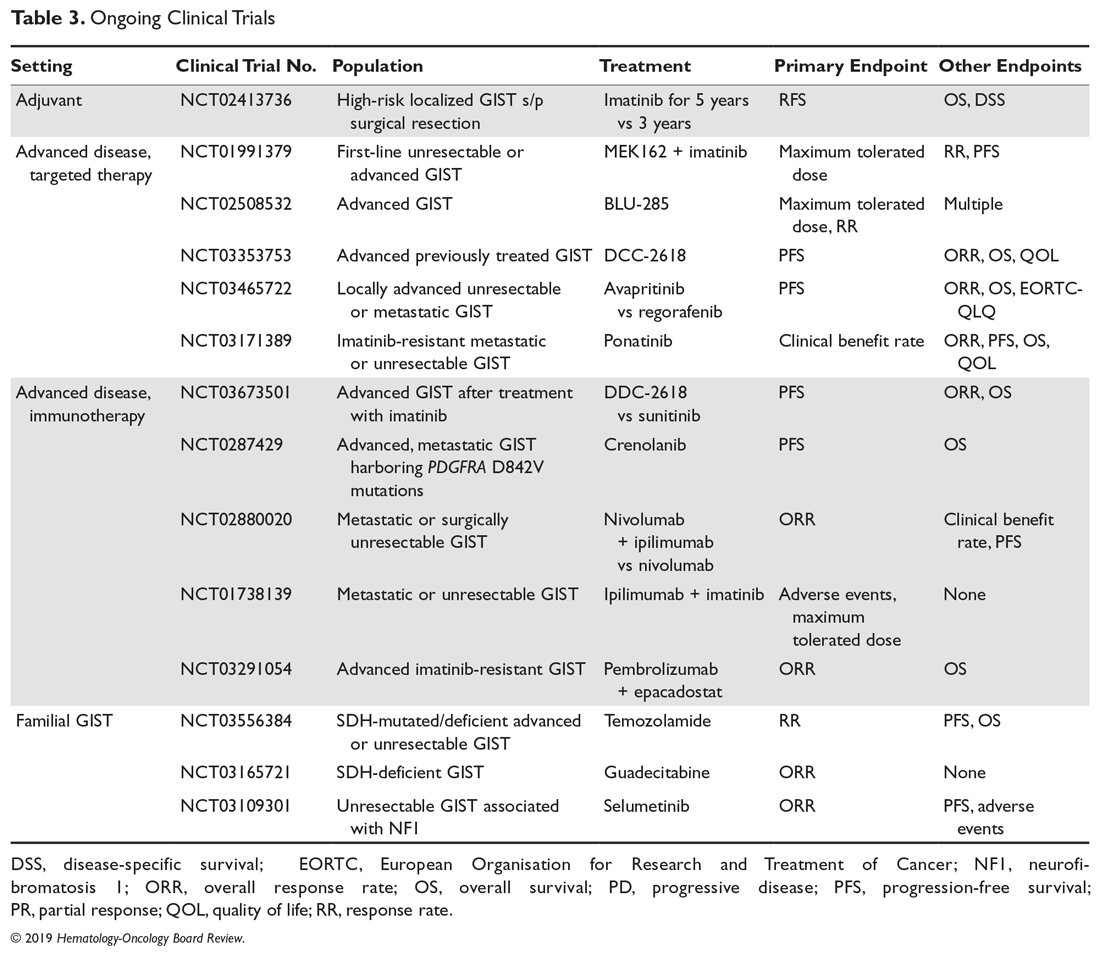

GISTs most commonly involve the stomach, followed by the small intestine, but can arise anywhere within the GI tract (esophagus, colon, rectum, and anus). They can also develop outside the GI tract, arising from the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum. The majority of cases are localized or locoregional, whereas about 20% are metastatic at presentation.1 GISTs can occur in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatric GISTs represent a distinct subset marked by female predominance and gastric origin, are often multifocal, can sometimes have lymph node involvement, and typically lack mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes.

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the diagnosis and management of GISTs. Here, we review the evaluation and diagnosis of GISTs along with management of localized disease. Management of advanced disease is reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man with progressive iron deficiency and abdominal discomfort undergoes upper and lower endoscopy and is found to have a bulging mass within his abdominal cavity. He undergoes a computed tomography (CT) evaluation of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast, which reveals the presence of a 10-cm gastric mass, with no other lesions identified. He undergoes surgical resection of the mass and presents for review of his pathology and to discuss his treatment plan.

What histopathologic features are consistent with GIST?

What factors are used for risk stratification and to predict likelihood of recurrence?

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Most patients present with symptoms of overt or occult GI bleeding or abdominal discomfort, but a significant proportion of GISTs are discovered incidentally. Lymph node involvement is not typical, except for GISTs occurring in children and/or with rare syndromes. Most syndromic GISTs are multifocal and multicentric. After surgical resection, GISTs usually recur or metastasize within the abdominal cavity, including the omentum, peritoneum, or liver. These tumors rarely spread to the lungs, brain, or bones; when tumor spread does occur, it tends to be in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced disease who have been on multiple lines of therapy for a long duration of time.

The diagnosis usually can be made by histopathology. Specimens can be obtained by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)– or CT-guided methods, the latter of which carries a very small risk of contamination from percutaneous biopsy. In terms of morphology, GISTs can be spindle cell, epithelioid, or mixed neoplasms. Epithelioid tumors are more commonly seen in the stomach and are often PDGFRA-mutated or SDH-deficient. The differential diagnosis includes other soft-tissue GI wall tumors such as leiomyosarcomas/leiomyomas, germ cell tumors, lymphomas, fibromatosis, and neuroendocrine and neurogenic tumors. A unique feature of GISTs that differentiates them from leiomyomas is near universal expression of CD117 by immunohistochemistry (IHC); this characteristic has allowed pathologists and providers to accurately distinguish true GISTs from other GI mesenchymal tumors.3 Recently, DOG1 (discovered on GIST1) immunoreactivity has been found to be helpful in identifying patients with CD117-negative GISTs. Initially identified through gene expression analysis of GISTs, DOG1 IHC can identify the common mutant c-Kit-driven CD117-positive GISTs as well as the rare CD117-negative GISTs, which are often driven by mutated PDGFRA.4 Importantly, IHC for KIT and DOG1 are not surrogates for mutational status, nor are they predictive of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sensitivity. If IHC of a tumor specimen is CD117- and DOG1-negative, the specimen can be sent for KIT and PDGFRA mutational analysis to confirm the diagnosis. If analysis reveals that these genes are wild-type, then IHC staining for SDH B (SDHB) should follow to assess for an SDH-deficient GIST (negative staining).

Risk Stratification for Recurrence

The clinical behavior of GISTs can be variable. Some are indolent, while others behave more aggressively, with a greater malignant potential and a higher propensity to recur and metastasize. Clinical and pathologic features can provide important prognostic information that allows providers to risk-stratify patients. Various institutions have assessed prognostic variables for GISTs. In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a GIST workshop that proposed an approach to estimating metastatic risk based on tumor size and mitotic index (NIH or Fletcher criteria).5 Joensuu et al later proposed a modification of the NIH risk classification to include tumor location and tumor rupture (modified NIH criteria or Joensuu criteria).6-8 Similarly, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) identified tumor site as a prognostic factor, with gastric GISTs having the best prognosis (AFIP-Miettinen criteria).9-11 Tabular schemes were designed which stratified patients into discrete groups with ranges for mitotic rate and tumor size. Nomograms for ease of use were then constructed utilizing a bimodal mitotic rate and included tumor site and size.12 Finally, contour maps were developed, which have the advantage of evaluating mitotic rate and tumor size as continuous nonlinear variables and also include tumor site and rupture (associated with a high risk of peritoneal metastasis) separately, further improving risk assessment. These contour maps have been validated against pooled data from 10 series (2560 patients).13 High-risk features identified from these studies include tumor location, size, mitotic rate and tumor rupture and are now used for deciding on the use of adjuvant imatinib and as requirements to enter clinical trials assessing adjuvant therapy for resected GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient’s operative and pathology reports indicate that the tumor is a spindle cell neoplasm of the stomach that is positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. Resection margins are negative. There are 10 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPF). Per the operative report, there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. Thus, while his GIST was gastric, which generally has a more favorable prognosis, the tumor harbors high-risk features based on its size and mitotic index.

What further testing should be requested?

Molecular Alterations

It is recommended that a mutational analysis be performed as part of the diagnostic work-up of all GISTs.14 Mutational analysis can provide prognostic and predictive information for sensitivity to imatinib and should be considered standard of care. It may also be useful for confirming a GIST diagnosis, or, if negative, lead to further evaluation with an IHC stain for SDHB. The c-Kit receptor is a member of the tyrosine kinase family and, through direct interactions with stem cell factor (SCF), can upregulate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, and JAK-STAT pathways, resulting in transcription and translation of genes that enhance cell growth and survival.15 The cell of origin of GISTs, the interstitial cells of Cajal, are dependent on the SCF–c-Kit interaction for development.16 Likewise, the large majority of GISTs (about 70%) are driven by upregulation and constitutive activation of c-Kit, which is normally autoinhibited. About 80% of KIT mutations involve exon 11; these GISTs are most often associated with a gastric location and are associated with a favorable recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate with surgery alone.17 KIT exon 9 mutations are much less common, encompassing only about 10% of GIST KIT mutations, and GISTs with these mutations are more likely to arise from the small bowel.17

About 8% of GISTs harbor gain-of-function PDGFRA driver mutations rendering constitutively active PDGFRA.18 PDGFRA mutations are mutually exclusive from KIT mutations, and PDGFRA-mutated tumors most often occur in the stomach. PDGFRA mutations generally are associated with a lower mitotic rate and gastric location. Identification of the PDGFRA D842V mutation on exon 18, which is the most common, is important, as it is associated with imatinib resistance, and these patients should not be offered imatinib.19

Several other mutations associated with GISTs outside of the KIT and PDGFRA spectrum have been identified. About 10% of GISTs are wildtype for KIT and PDGFRA, and not all KIT/PDGFRA-wildtype GISTs are imatinib-sensitive and/or respond to other TKIs.18 These tumors may harbor aberrations in SDH and NF1, or less commonly, BRAF V600E, FGFR, and NTRK.20,21 SDH subunits B, C and D play a role in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain. Germline mutations in these SDH subunits can result in the Carney-Stratakis syndrome characterized by the dyad of multifocal GISTs and multicentric paragangliomas.22 This syndrome is most likely to manifest in the pediatric or young adult population. In contradistinction is the Carney triad, which is associated with acquired loss of function of the SDHC gene due to promoter hypermethylation. This syndrome classically occurs in young women and is characterized by an indolent-behaving triad of multicentric GISTs, non-adrenal paragangliomas, and pulmonary chondromas.23 Like PDGFRA D842V–mutated GISTs, SDH-deficient and NF1-associated GISTs are considered imatinib resistant, and these patients should not be offered imatinib therapy.14

Case Continued

The patient’s GIST is found to harbor a KIT exon 11 single codon deletion. He appears anxious and asks to have everything done to prevent his GIST from coming back and to improve his lifespan.

What are the next steps in the management of this patient?

Management

A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of all GISTs is essential and includes input from radiology, gastroenterology, pathology, medical and surgical oncology, nuclear medicine, and nursing.

Surgical Resection

Small esophagogastric and duodenal GISTs ≤ 2 cm can be asymptomatic and managed with serial endoscopic surveillance, typically every 6 to 12 months, with biopsies if the tumors increase in size. GISTs larger than 2 cm require surgical resection, with resection of the full pseudocapsule and an R0 resection, if possible, since larger GISTs carry a higher risk of growth and recurrence. If an R0 resection would lead to significant morbidity or functional sequelae, an R1 may suffice. Rectal GISTs are an exception, where microscopic margins have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of local failure.24 It is important to explore the abdomen thoroughly for peritoneal, rectovaginal, and vesicular implants and metastasis to the liver. A formal lymph node dissection is not necessary because lymph nodes are rarely involved and should only be removed when clinically suspicious. Tumor rupture must be avoided. A laparoscopic approach should only be considered for smaller tumors, since there is a risk of tumor rupture with larger tumors.14

When is adjuvant imatinib indicated?

Adjuvant Imatinib

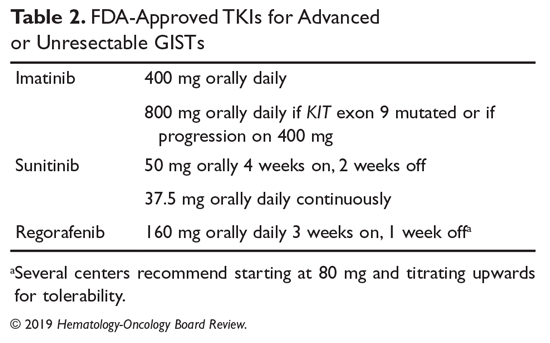

Among patients with local or locally advanced GISTs, the risk of death from recurrence with surgery alone can be high, with a historical 5-year overall survival (OS) of about 35%.25 As a result, multiple studies have assessed the benefit of adjuvant imatinib, which is now considered standard of care for patients with imatinib-sensitive, high-risk GISTs. In addition to inhibiting BCR-ABL, imatinib mesylate inhibits multiple other receptor tyrosine kinases, including PDGFR, SCF and c-Kit. As a result, imatinib has demonstrated in vitro inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis and clinical activity against GISTs expressing CD117.26 Importantly, adjuvant imatinib should only be offered to patients with imatinib-sensitive mutations, such as KIT exon 11 and KIT exon 9 mutations. Adjuvant imatinib should not be offered to patients with imatinib-insensitive mutations such as PDGFR 842V, NF1, or BRAF-related or SDH-deficient GISTs.

The ACOSOG Z9000 was the first study of adjuvant imatinib in patients with resected GISTs.25 This was a single-arm, phase 2 study involving 106 patients with surgically resected GISTs deemed high-risk for recurrence, defined as size > 10 cm, tumor rupture, or up to 4 peritoneal implants. Patients were treated with imatinib 400 mg daily for 1 year. The primary and secondary endpoints were OS and RFS, respectively. Long-term follow-up of this study demonstrated 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of 99%, 97%, and 83%, and 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS of 96%, 60%, and 40%, which compared favorably with historical controls. In a multivariable analysis, increasing tumor size, small bowel location, KIT exon 9 mutation, high mitotic rate, and older age were independent risk factors for a poor RFS.25 It is important to note that the benefit of adjuvant imatinib waned after discontinuation of therapy, creating a rationale to study adjuvant imatinib for longer periods of time.

As a result of the promising phase 2 data, ACOSOG opened a phase 3 randomized trial (Z9001) comparing 1 year of adjuvant imatinib to placebo among patients with surgically resected GISTs that were > 3 cm in size and that stained positive for CD117 on pathology. The trial accrued 713 patients and was stopped early at a planned interim analysis, which revealed a 1-year RFS of 98% for imatinib versus 83% for placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 0.35; P < 0.001). The 1-year OS did not differ between the 2 arms (92.2% vs 99.7%; HR, 0.66; P = 0.47).27 When comparing the 2 arms, imatinib was associated with a higher RFS among patients with a KIT exon 11 deletion, but not among patients with other KIT mutation types, PDGFRA mutations, or who were KIT/PDGFRA wildtype.28 Imatinib was granted approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the adjuvant treatment of high-risk GISTs based on the results of the ACOSOG Z9001 trial.

The EORTC 62024 study was a randomized placebo-controlled trial assessing the benefit of 2 years of adjuvant imatinib.29 Patients had to be considered intermediate or high risk per the 2002 NIH consensus classification to be eligible. The trial enrolled 918 patients. The 5-year OS rate, the original primary endpoint, did not differ between the 2 groups (100% vs 99%). The 3-year and 5-year RFS rates, secondary endpoints, were significantly longer among patients treated with imatinib (84% vs 66% and 69% vs 63%, respectively). Again, it was noted that the benefit of imatinib waned over time after treatment discontinuation.

The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG XVIII) trial was a prospective randomized phase 3 trial that compared 3 years versus 1 year of adjuvant imatinib.30 Patients had to be enrolled within 12 weeks of the postoperative period and had to have GISTs that were CD117-positive and with a high estimated risk of recurrence, per the modified NIH consensus criteria (size > 10 cm, > 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, diameter > 5 cm with mitotic count > 5, or tumor rupture before or at surgery). Three years of adjuvant imatinib was associated with a 54% reduction in the hazard for recurrence at 5 years (65.6% vs 47.9%; HR, 0.46; P < 0.001) and a 55% reduction in the hazard for death at 5 years (OS 92% vs 81.7%; HR, 0.45; P = 0.02). Based on the results of this study, the FDA granted approval for the use of 3 years of adjuvant imatinib in patients with high-risk resected GISTs.

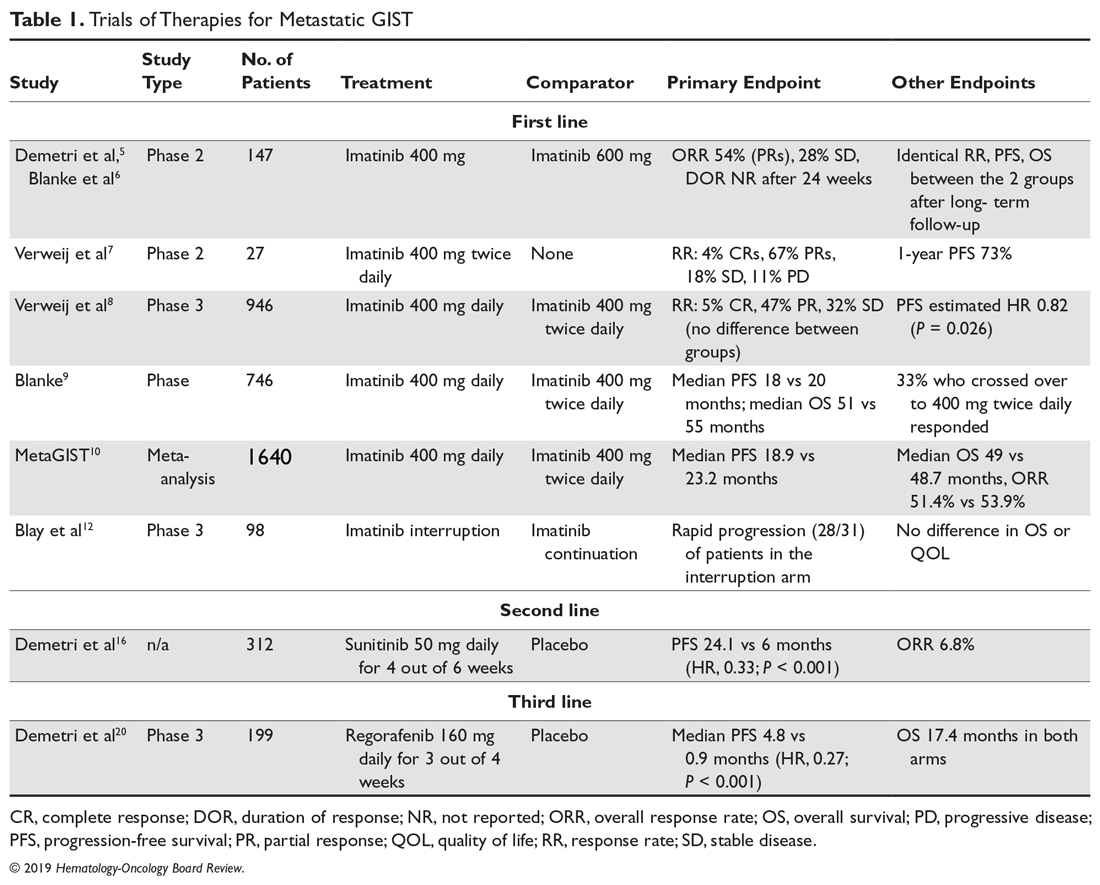

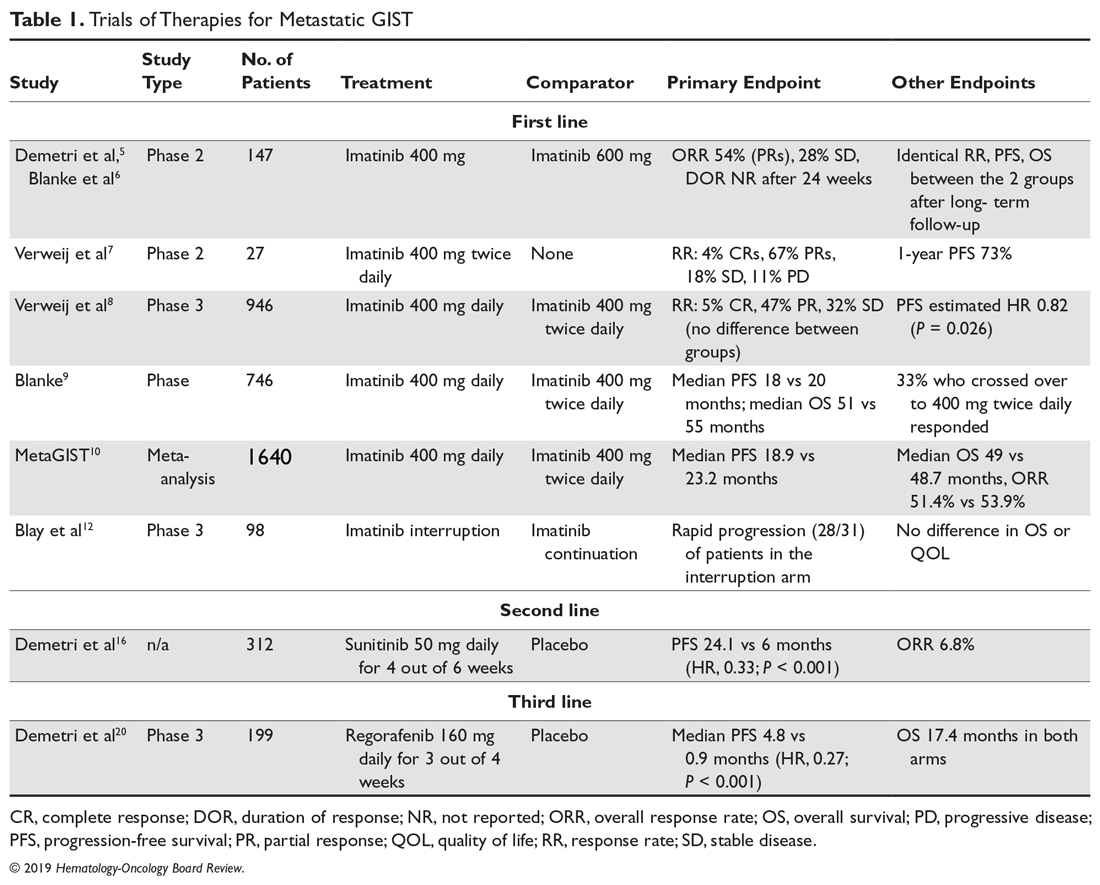

The observation that a longer duration of adjuvant imatinib was associated with superior RFS and OS led to studies to further explore longer durations of adjuvant imatinib. The PERSIST-5 (Postresection Evaluation of Recurrence-free Survival for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors With 5 Years of Adjuvant Imatinib) was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 prospective study of adjuvant imatinib with a primary endpoint of RFS after 5 years.31 Patients had to have an intermediate or high risk of recurrence, which included GISTs at any site > 2 cm with > 5 mitoses per 50 HPF or nongastric GISTs that were ≥ 5 cm. With 91 patients enrolled, the estimated 5-year RFS was 90% and the OS was 95%. Of note, about half of the patients stopped treatment early due to a variety of reasons, including patient choice or adverse events. Importantly, there were no recurrences in patients with imatinib-sensitive mutations while on therapy. We know that in patients at high risk of relapse, adjuvant imatinib delays recurrence and improves survival, but whether any patients are cured, or their survival curves are just shifted to the right, is unknown. Only longer follow-up of existing studies, and the results of newer trials utilizing longer durations of adjuvant treatment, will help to determine the real value of adjuvant therapy for GIST patients.32 Based on this study, it would be reasonable to discuss a longer duration of imatinib with patients deemed to be at very high risk of recurrence and who are tolerating therapy well. We are awaiting the data from the randomized phase 3 Scandinavian Sarcoma Group XII trial comparing 5 years versus 3 years of adjuvant imatinib therapy, and from the French ImadGIST trial of adjuvant imatinib for 3 versus 6 years. A summary of the aforementioned key adjuvant trials is shown in the Table.

When imatinib is commenced, careful monitoring for treatment toxicities and drug interactions should ensue in order to improve compliance. Dose density should be maintained if possible, as retrospective studies suggest suboptimal plasma levels are associated with a worse outcome.33

When should neoadjuvant imatinib be considered?

Neoadjuvant Imatinib

Neoadjuvant imatinib should be considered for patients requiring total gastrectomy, esophagectomy, or abdominoperineal resection of the rectum in order to reduce tumor size, limit subsequent surgical morbidity, mitigate tumor bleeding and rupture, and aid with organ preservation. Patients with rectal GISTs that may otherwise warrant an abdominoperineal resection should be offered a trial of imatinib in the neoadjuvant setting. There is no evidence for the use of any other TKI aside from imatinib in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. With neoadjuvant imatinib, it is difficult to accurately assess the mitotic rate in the resected tumor specimen.

The RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665 trial was a prospective phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of imatinib 600 mg daily in the perioperative setting.34 The trial enrolled 50 patients, 30 with primary GISTs (group A) and 22 with recurrent metastatic GISTs (group B). Based on data from the metastatic setting revealing a time to treatment response of about 2.5 months, patients were treated with 8 to 12 weeks of preoperative imatinib followed by 2 years of adjuvant imatinib. Imatinib was stopped 24 hours preoperatively and resumed as soon as possible postoperatively. In group A, 7% of patients achieved a partial response (PR), 83% achieved stable disease, and 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were 83% and 93%, respectively. In group B, 4.5% of patients achieved a PR, 91% achieved stable disease, and 4.5% experienced progressive disease in the preoperative period; the 2-year PFS and OS were 77% and 91%, respectively. The results of this trial demonstrated the feasibility of using perioperative imatinib with minimal effects on surgical outcomes and set the rationale to use neoadjuvant imatinib in select patients with borderline resectable or rectal GISTs. Another EORTC pooled analysis from 10 sarcoma centers revealed that after a median of 10 months of neoadjuvant imatinib, 83.2% of patients achieved an R0 resection and only 1% progressed during treatment.35 After a median follow-up of 46 months, the 5-year disease-free survival and OS were 65% and 87%, respectively.

Mutational testing should be performed beforehand to ensure the tumor is imatinib-sensitive. If a KIT exon 9 mutation is identified, then 400 mg twice daily should be considered (given the benefit seen with 800 mg imatinib for advanced GIST patients), although there are no studies to confirm this practice. Neoadjuvant imatinib is recommended for a total of 6 to 12 months to ensure maximal tumor debulking, but with very close monitoring and surgical input for disease resistance and growth.14 Imatinib should be stopped 1 to 2 days preoperatively and resumed once the patient has recovered from surgery for a total of 3 years (pre-/postoperatively combined). Neoadjuvant therapy has been shown to be safe and effective, but there have been no randomized trials to assess survival.

What is appropriate surveillance for resected GISTs?

Surveillance

There have been no randomized studies to guide the management of surveillance after surgical resection and adjuvant therapy. There is no known optimal follow-up schedule, but several have been proposed.13,36 Among high-risk patients, it is suggested to image every 3 to 6 months during adjuvant therapy, followed by every 3 months for 2 years after discontinuing therapy, then every 6 months for another 3 years and annually thereafter for an additional 5 years. High-risk patients usually relapse within 1 to 3 years after finishing adjuvant therapy, while low-risk patients can relapse later given that their disease can be slower growing. It has been recommended that low-risk patients undergo imaging every 6 months for 5 years, with follow-up individualized thereafter. Very-low-risk patients may not require more than annual imaging. Because most relapses occur within the peritoneum or liver, imaging should encompass the abdomen and pelvis. Surveillance imaging usually consists of CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis. MRI scans can be utilized for patients at lower risk or who are out several years in order to avoid excess radiation exposure. MRI is also specifically helpful for rectal and esophageal lesions. Chest CT or chest radiograph and bone scan are not routinely required for follow-up.

Case Conclusion

The patient receives adjuvant imatinib and experiences grade 2 myalgias, periorbital edema, and macrocytic anemia, which result in imatinib discontinuation after 3 years of treatment. He is seen every 3 to 6 months and a contrast CT abdomen and pelvis is obtained every 6 months for 5 years. During this 5-year follow-up period, he does not have any clinical or radiographic evidence of disease recurrence.

Further follow-up of this patient is presented in the second article in this 2-part review of management of GISTs.

Key Points

- GISTs are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the GI tract and can occasionally occur in extragastrointestinal locations as well.

- GISTs encompass a heterogeneous family of tumor subsets with different natural histories, mutations, and TKI responsiveness.

- Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized GISTs, with cure rates greater than 50%.

- For very small (< 2 cm) esophagogastric GISTs, endoscopic ultrasound evaluation and follow-up is recommended.

- For tumors ≥ 2 cm, biopsy and excision is the standard approach.

- For localized GISTs, complete surgical resection (R0) is standard treatment, with no lymphadenectomy for clinically negative lymph nodes.

- Mutational analysis should be considered standard of practice. It can be helpful for confirming the diagnosis and can be predictive and prognostic in determining specific TKI therapy and dose.

- Adjuvant imatinib at a dose of 400 mg for 3 years is standard of care for GISTs that are at high risk of relapse and are imatinib-sensitive, and it is the only TKI approved for adjuvant therapy. Patients with PDGFRA D842V, NF1, BRAF or SDH-deficient GISTs should not receive adjuvant imatinib therapy.

- Neoadjuvant therapy can be utilized for sites where extensive resection would lead to significant morbidity. It should be given for 6 to 12 months, but patients need to be monitored closely for tumor growth.

1. Ma GL, Murphy JD, Martinez ME et al. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of histology codes: results of a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:298-302.

2. Agaimy A, Wunsch PH, Hofstaedter F, et al. Minute gastric sclerosing stromal tumors (GIST tumorlets) are common in adults and frequently show c-KIT mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:113-120.

3. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Sarlomo-Rikala M. Immunohistochemical spectrum of GISTs at different sites and their differential diagnosis with a reference to CD117 (KIT). Mod Pathol. 2000;13:1134-1142.

4. West RB, Corless CL, Chen X, et al. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutational status. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:107-113.

5. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10:81-89.

6. Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419.

7. Hohenberger P, Ronellenfitsch U, Oladeji O, et al. Pattern of recurrence in patients with ruptured primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1854-1859.

8. Holmenbakk T, Bjerkehagen B, Boye K, et al. Definition and clinical significance of tumor rupture in gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the small intestine. Br J Surg. 2016;103:684-691.

9. Emory TS, Sobin LH, Lukes L, et al. Prognosis of gastrointestinal smooth-muscle (stromal) tumors: dependence on anatomic site. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:82-87.

10. Miettinen M, Makhlouf H, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the jejunum and ileum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 906 cases before imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:477-489.

11. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:52-68.

12. Gold JS, Gonen M, Gutierrez A, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence-free survival after complete surgical resection of localized primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1045-1052.

13. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Rihimaki J et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265-274.

14. Casali PG, Abecassis N, Bauer S, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement_4): iv267.

15. Jing L, Yan-Ling W, Bing-Jia C, et al. The c-kit receptor-mediated signal transduction and tumor-related diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:435-443.

16. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577-580.

17. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:634-642.

18. Corless CL, Fletcher JA, Heinrich MC. Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3813-3825.

19. Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342-4349.

20. Huss S, Pasternack H, Ihle MA, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of a large cohort of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and review of the literature: BRAF mutations in KIT/PDGFRA wild-type GISTs are rare events. Hum Pathol. 2017;62:206-214.

21. Shi E, Chmielecki J, Tang CM, et al. FGFR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in “Wild-Type” gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:339.

22. Carney JA, Stratakis CA. Familial paraganglioma and gastric stromal sarcoma: a new syndrome distinct from the Carney triad. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108:132-139.

23. Carney JA. Gastric stromal sarcoma, pulmonary chondroma, and extra-adrenal paraganglioma (Carney Triad): natural history, adrenocortical component, and possible familial occurrence. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:543-552.

24. Jakob J, Mussi C, Ronellenfitsch U, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum: results of surgical and multimodality therapy in the era of imatinib. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:586-592.

25. DeMatteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Long-term results of adjuvant imatinib mesylate in localized, high-risk, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): ACOSOG Z9000 (Alliance) intergroup phase 2 trial. Ann Surg. 2013;258:422-429.

26. Gleevac (imatinib) [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2016.

27. DeMatteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Placebo-controlled randomized trial of adjuvant imatinib mesylate following the resection of localized, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Lancet. 2009;373:1097-1104.

28. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1563-1570.

29. Casali PG, Le Cesne A, Poveda Velasco A, et al. Imatinib failure-free survival (IFS) in patients with localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) treated with adjuvant imatinib (IM): the EORTC/AGITG/FSG/GEIS/ISG randomized controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31. Abstract 10500.

30. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby HK, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265-1272.

31. Raut CP, Espat NJ, Maki RG, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of 5-year adjuvant imatinib treatment for patients with resected intermediate- or high-risk primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor: The PERSIST-5 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018: e184060.

32. Benjamin RS, Casali PG. Adjuvant imatinib for GI stromal tumors: when and for how long? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:215-218.

33. Demetri GD, Wang Y, Wehrle E, et al. Imatinib plasma levels are correlated with clinical benefit in patients with unresectable/metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3141-3147.

34. Eisenberg BL, Harris J, Blanke CD, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate (IM) for advanced primary and metastatic/recurrent operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): early results of RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:42-47.

35. Rutkowski P, Gronchi A, Hohenberger P, et al. Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): the EORTC STBSG experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2937-2943.

36. Joensuu H, Martin-Broto J, Nishida T, et al. Follow-up strategies for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour treated with or without adjuvant imatinib after surgery. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1611-1617.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal of the myenteric plexus. These tumors are rare, with about 1 case per 100,000 persons diagnosed in the United States annually, but may be incidentally discovered in up to 1 in 5 autopsy specimens of older adults.1,2 Epidemiologic risk factors include increasing age, with a peak incidence between age 60 and 65 years, male gender, black race, and non-Hispanic white ethnicity. Germline predisposition can also increase the risk of developing GISTs; molecular drivers of GIST include gain-of-function mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) gene, which both encode structurally similar tyrosine kinase receptors; germline mutations of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunit genes; and mutations associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.

GISTs most commonly involve the stomach, followed by the small intestine, but can arise anywhere within the GI tract (esophagus, colon, rectum, and anus). They can also develop outside the GI tract, arising from the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum. The majority of cases are localized or locoregional, whereas about 20% are metastatic at presentation.1 GISTs can occur in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatric GISTs represent a distinct subset marked by female predominance and gastric origin, are often multifocal, can sometimes have lymph node involvement, and typically lack mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes.

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the diagnosis and management of GISTs. Here, we review the evaluation and diagnosis of GISTs along with management of localized disease. Management of advanced disease is reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man with progressive iron deficiency and abdominal discomfort undergoes upper and lower endoscopy and is found to have a bulging mass within his abdominal cavity. He undergoes a computed tomography (CT) evaluation of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast, which reveals the presence of a 10-cm gastric mass, with no other lesions identified. He undergoes surgical resection of the mass and presents for review of his pathology and to discuss his treatment plan.

What histopathologic features are consistent with GIST?

What factors are used for risk stratification and to predict likelihood of recurrence?

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Most patients present with symptoms of overt or occult GI bleeding or abdominal discomfort, but a significant proportion of GISTs are discovered incidentally. Lymph node involvement is not typical, except for GISTs occurring in children and/or with rare syndromes. Most syndromic GISTs are multifocal and multicentric. After surgical resection, GISTs usually recur or metastasize within the abdominal cavity, including the omentum, peritoneum, or liver. These tumors rarely spread to the lungs, brain, or bones; when tumor spread does occur, it tends to be in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced disease who have been on multiple lines of therapy for a long duration of time.

The diagnosis usually can be made by histopathology. Specimens can be obtained by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)– or CT-guided methods, the latter of which carries a very small risk of contamination from percutaneous biopsy. In terms of morphology, GISTs can be spindle cell, epithelioid, or mixed neoplasms. Epithelioid tumors are more commonly seen in the stomach and are often PDGFRA-mutated or SDH-deficient. The differential diagnosis includes other soft-tissue GI wall tumors such as leiomyosarcomas/leiomyomas, germ cell tumors, lymphomas, fibromatosis, and neuroendocrine and neurogenic tumors. A unique feature of GISTs that differentiates them from leiomyomas is near universal expression of CD117 by immunohistochemistry (IHC); this characteristic has allowed pathologists and providers to accurately distinguish true GISTs from other GI mesenchymal tumors.3 Recently, DOG1 (discovered on GIST1) immunoreactivity has been found to be helpful in identifying patients with CD117-negative GISTs. Initially identified through gene expression analysis of GISTs, DOG1 IHC can identify the common mutant c-Kit-driven CD117-positive GISTs as well as the rare CD117-negative GISTs, which are often driven by mutated PDGFRA.4 Importantly, IHC for KIT and DOG1 are not surrogates for mutational status, nor are they predictive of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sensitivity. If IHC of a tumor specimen is CD117- and DOG1-negative, the specimen can be sent for KIT and PDGFRA mutational analysis to confirm the diagnosis. If analysis reveals that these genes are wild-type, then IHC staining for SDH B (SDHB) should follow to assess for an SDH-deficient GIST (negative staining).

Risk Stratification for Recurrence

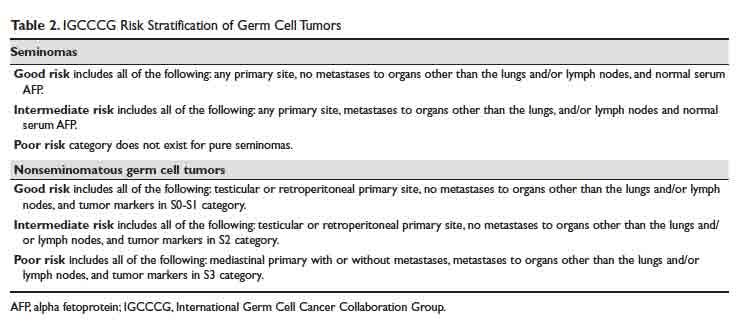

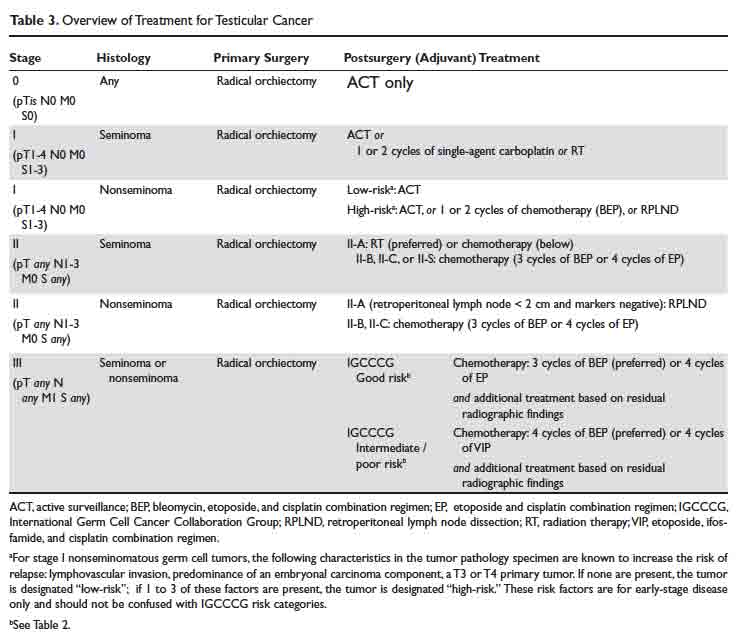

The clinical behavior of GISTs can be variable. Some are indolent, while others behave more aggressively, with a greater malignant potential and a higher propensity to recur and metastasize. Clinical and pathologic features can provide important prognostic information that allows providers to risk-stratify patients. Various institutions have assessed prognostic variables for GISTs. In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a GIST workshop that proposed an approach to estimating metastatic risk based on tumor size and mitotic index (NIH or Fletcher criteria).5 Joensuu et al later proposed a modification of the NIH risk classification to include tumor location and tumor rupture (modified NIH criteria or Joensuu criteria).6-8 Similarly, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) identified tumor site as a prognostic factor, with gastric GISTs having the best prognosis (AFIP-Miettinen criteria).9-11 Tabular schemes were designed which stratified patients into discrete groups with ranges for mitotic rate and tumor size. Nomograms for ease of use were then constructed utilizing a bimodal mitotic rate and included tumor site and size.12 Finally, contour maps were developed, which have the advantage of evaluating mitotic rate and tumor size as continuous nonlinear variables and also include tumor site and rupture (associated with a high risk of peritoneal metastasis) separately, further improving risk assessment. These contour maps have been validated against pooled data from 10 series (2560 patients).13 High-risk features identified from these studies include tumor location, size, mitotic rate and tumor rupture and are now used for deciding on the use of adjuvant imatinib and as requirements to enter clinical trials assessing adjuvant therapy for resected GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient’s operative and pathology reports indicate that the tumor is a spindle cell neoplasm of the stomach that is positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. Resection margins are negative. There are 10 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPF). Per the operative report, there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. Thus, while his GIST was gastric, which generally has a more favorable prognosis, the tumor harbors high-risk features based on its size and mitotic index.

What further testing should be requested?

Molecular Alterations

It is recommended that a mutational analysis be performed as part of the diagnostic work-up of all GISTs.14 Mutational analysis can provide prognostic and predictive information for sensitivity to imatinib and should be considered standard of care. It may also be useful for confirming a GIST diagnosis, or, if negative, lead to further evaluation with an IHC stain for SDHB. The c-Kit receptor is a member of the tyrosine kinase family and, through direct interactions with stem cell factor (SCF), can upregulate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, and JAK-STAT pathways, resulting in transcription and translation of genes that enhance cell growth and survival.15 The cell of origin of GISTs, the interstitial cells of Cajal, are dependent on the SCF–c-Kit interaction for development.16 Likewise, the large majority of GISTs (about 70%) are driven by upregulation and constitutive activation of c-Kit, which is normally autoinhibited. About 80% of KIT mutations involve exon 11; these GISTs are most often associated with a gastric location and are associated with a favorable recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate with surgery alone.17 KIT exon 9 mutations are much less common, encompassing only about 10% of GIST KIT mutations, and GISTs with these mutations are more likely to arise from the small bowel.17

About 8% of GISTs harbor gain-of-function PDGFRA driver mutations rendering constitutively active PDGFRA.18 PDGFRA mutations are mutually exclusive from KIT mutations, and PDGFRA-mutated tumors most often occur in the stomach. PDGFRA mutations generally are associated with a lower mitotic rate and gastric location. Identification of the PDGFRA D842V mutation on exon 18, which is the most common, is important, as it is associated with imatinib resistance, and these patients should not be offered imatinib.19

Several other mutations associated with GISTs outside of the KIT and PDGFRA spectrum have been identified. About 10% of GISTs are wildtype for KIT and PDGFRA, and not all KIT/PDGFRA-wildtype GISTs are imatinib-sensitive and/or respond to other TKIs.18 These tumors may harbor aberrations in SDH and NF1, or less commonly, BRAF V600E, FGFR, and NTRK.20,21 SDH subunits B, C and D play a role in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain. Germline mutations in these SDH subunits can result in the Carney-Stratakis syndrome characterized by the dyad of multifocal GISTs and multicentric paragangliomas.22 This syndrome is most likely to manifest in the pediatric or young adult population. In contradistinction is the Carney triad, which is associated with acquired loss of function of the SDHC gene due to promoter hypermethylation. This syndrome classically occurs in young women and is characterized by an indolent-behaving triad of multicentric GISTs, non-adrenal paragangliomas, and pulmonary chondromas.23 Like PDGFRA D842V–mutated GISTs, SDH-deficient and NF1-associated GISTs are considered imatinib resistant, and these patients should not be offered imatinib therapy.14

Case Continued

The patient’s GIST is found to harbor a KIT exon 11 single codon deletion. He appears anxious and asks to have everything done to prevent his GIST from coming back and to improve his lifespan.

What are the next steps in the management of this patient?

Management

A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of all GISTs is essential and includes input from radiology, gastroenterology, pathology, medical and surgical oncology, nuclear medicine, and nursing.

Surgical Resection

Small esophagogastric and duodenal GISTs ≤ 2 cm can be asymptomatic and managed with serial endoscopic surveillance, typically every 6 to 12 months, with biopsies if the tumors increase in size. GISTs larger than 2 cm require surgical resection, with resection of the full pseudocapsule and an R0 resection, if possible, since larger GISTs carry a higher risk of growth and recurrence. If an R0 resection would lead to significant morbidity or functional sequelae, an R1 may suffice. Rectal GISTs are an exception, where microscopic margins have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of local failure.24 It is important to explore the abdomen thoroughly for peritoneal, rectovaginal, and vesicular implants and metastasis to the liver. A formal lymph node dissection is not necessary because lymph nodes are rarely involved and should only be removed when clinically suspicious. Tumor rupture must be avoided. A laparoscopic approach should only be considered for smaller tumors, since there is a risk of tumor rupture with larger tumors.14

When is adjuvant imatinib indicated?

Adjuvant Imatinib

Among patients with local or locally advanced GISTs, the risk of death from recurrence with surgery alone can be high, with a historical 5-year overall survival (OS) of about 35%.25 As a result, multiple studies have assessed the benefit of adjuvant imatinib, which is now considered standard of care for patients with imatinib-sensitive, high-risk GISTs. In addition to inhibiting BCR-ABL, imatinib mesylate inhibits multiple other receptor tyrosine kinases, including PDGFR, SCF and c-Kit. As a result, imatinib has demonstrated in vitro inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis and clinical activity against GISTs expressing CD117.26 Importantly, adjuvant imatinib should only be offered to patients with imatinib-sensitive mutations, such as KIT exon 11 and KIT exon 9 mutations. Adjuvant imatinib should not be offered to patients with imatinib-insensitive mutations such as PDGFR 842V, NF1, or BRAF-related or SDH-deficient GISTs.

The ACOSOG Z9000 was the first study of adjuvant imatinib in patients with resected GISTs.25 This was a single-arm, phase 2 study involving 106 patients with surgically resected GISTs deemed high-risk for recurrence, defined as size > 10 cm, tumor rupture, or up to 4 peritoneal implants. Patients were treated with imatinib 400 mg daily for 1 year. The primary and secondary endpoints were OS and RFS, respectively. Long-term follow-up of this study demonstrated 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of 99%, 97%, and 83%, and 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS of 96%, 60%, and 40%, which compared favorably with historical controls. In a multivariable analysis, increasing tumor size, small bowel location, KIT exon 9 mutation, high mitotic rate, and older age were independent risk factors for a poor RFS.25 It is important to note that the benefit of adjuvant imatinib waned after discontinuation of therapy, creating a rationale to study adjuvant imatinib for longer periods of time.

As a result of the promising phase 2 data, ACOSOG opened a phase 3 randomized trial (Z9001) comparing 1 year of adjuvant imatinib to placebo among patients with surgically resected GISTs that were > 3 cm in size and that stained positive for CD117 on pathology. The trial accrued 713 patients and was stopped early at a planned interim analysis, which revealed a 1-year RFS of 98% for imatinib versus 83% for placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 0.35; P < 0.001). The 1-year OS did not differ between the 2 arms (92.2% vs 99.7%; HR, 0.66; P = 0.47).27 When comparing the 2 arms, imatinib was associated with a higher RFS among patients with a KIT exon 11 deletion, but not among patients with other KIT mutation types, PDGFRA mutations, or who were KIT/PDGFRA wildtype.28 Imatinib was granted approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the adjuvant treatment of high-risk GISTs based on the results of the ACOSOG Z9001 trial.

The EORTC 62024 study was a randomized placebo-controlled trial assessing the benefit of 2 years of adjuvant imatinib.29 Patients had to be considered intermediate or high risk per the 2002 NIH consensus classification to be eligible. The trial enrolled 918 patients. The 5-year OS rate, the original primary endpoint, did not differ between the 2 groups (100% vs 99%). The 3-year and 5-year RFS rates, secondary endpoints, were significantly longer among patients treated with imatinib (84% vs 66% and 69% vs 63%, respectively). Again, it was noted that the benefit of imatinib waned over time after treatment discontinuation.

The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG XVIII) trial was a prospective randomized phase 3 trial that compared 3 years versus 1 year of adjuvant imatinib.30 Patients had to be enrolled within 12 weeks of the postoperative period and had to have GISTs that were CD117-positive and with a high estimated risk of recurrence, per the modified NIH consensus criteria (size > 10 cm, > 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, diameter > 5 cm with mitotic count > 5, or tumor rupture before or at surgery). Three years of adjuvant imatinib was associated with a 54% reduction in the hazard for recurrence at 5 years (65.6% vs 47.9%; HR, 0.46; P < 0.001) and a 55% reduction in the hazard for death at 5 years (OS 92% vs 81.7%; HR, 0.45; P = 0.02). Based on the results of this study, the FDA granted approval for the use of 3 years of adjuvant imatinib in patients with high-risk resected GISTs.

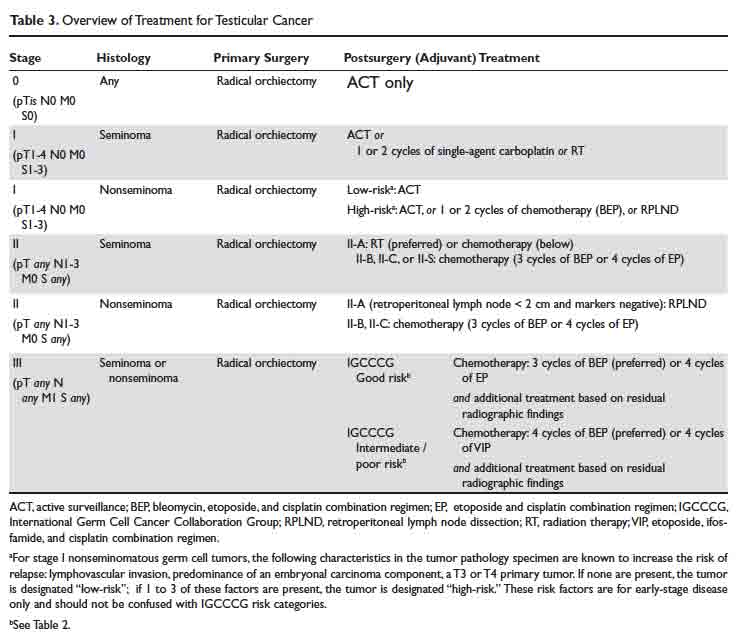

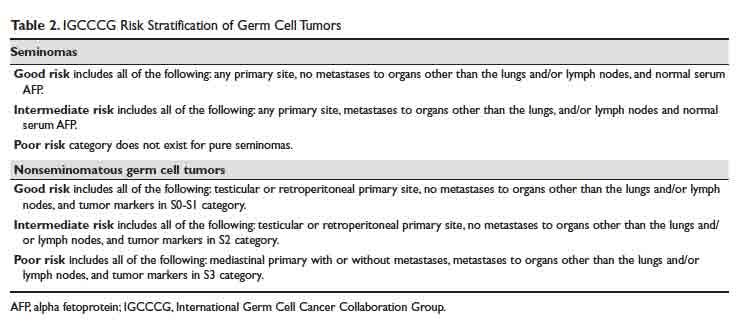

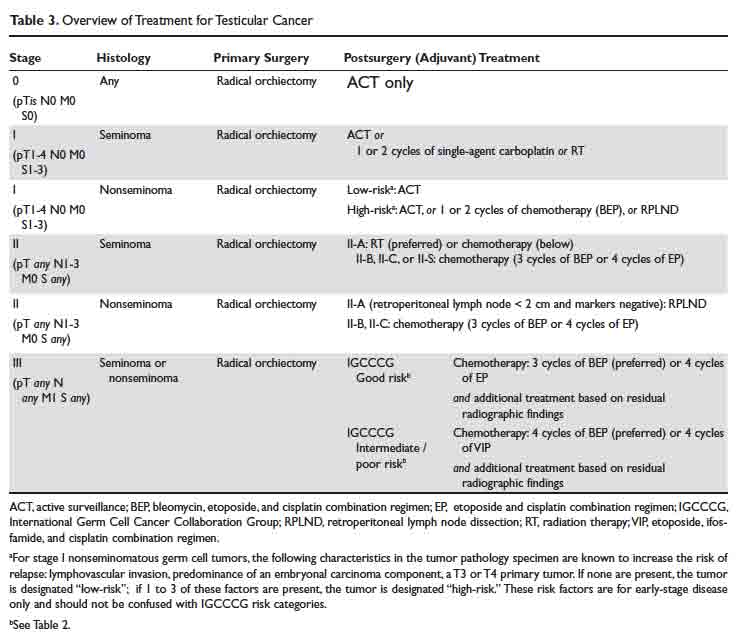

The observation that a longer duration of adjuvant imatinib was associated with superior RFS and OS led to studies to further explore longer durations of adjuvant imatinib. The PERSIST-5 (Postresection Evaluation of Recurrence-free Survival for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors With 5 Years of Adjuvant Imatinib) was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 prospective study of adjuvant imatinib with a primary endpoint of RFS after 5 years.31 Patients had to have an intermediate or high risk of recurrence, which included GISTs at any site > 2 cm with > 5 mitoses per 50 HPF or nongastric GISTs that were ≥ 5 cm. With 91 patients enrolled, the estimated 5-year RFS was 90% and the OS was 95%. Of note, about half of the patients stopped treatment early due to a variety of reasons, including patient choice or adverse events. Importantly, there were no recurrences in patients with imatinib-sensitive mutations while on therapy. We know that in patients at high risk of relapse, adjuvant imatinib delays recurrence and improves survival, but whether any patients are cured, or their survival curves are just shifted to the right, is unknown. Only longer follow-up of existing studies, and the results of newer trials utilizing longer durations of adjuvant treatment, will help to determine the real value of adjuvant therapy for GIST patients.32 Based on this study, it would be reasonable to discuss a longer duration of imatinib with patients deemed to be at very high risk of recurrence and who are tolerating therapy well. We are awaiting the data from the randomized phase 3 Scandinavian Sarcoma Group XII trial comparing 5 years versus 3 years of adjuvant imatinib therapy, and from the French ImadGIST trial of adjuvant imatinib for 3 versus 6 years. A summary of the aforementioned key adjuvant trials is shown in the Table.

When imatinib is commenced, careful monitoring for treatment toxicities and drug interactions should ensue in order to improve compliance. Dose density should be maintained if possible, as retrospective studies suggest suboptimal plasma levels are associated with a worse outcome.33

When should neoadjuvant imatinib be considered?

Neoadjuvant Imatinib

Neoadjuvant imatinib should be considered for patients requiring total gastrectomy, esophagectomy, or abdominoperineal resection of the rectum in order to reduce tumor size, limit subsequent surgical morbidity, mitigate tumor bleeding and rupture, and aid with organ preservation. Patients with rectal GISTs that may otherwise warrant an abdominoperineal resection should be offered a trial of imatinib in the neoadjuvant setting. There is no evidence for the use of any other TKI aside from imatinib in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. With neoadjuvant imatinib, it is difficult to accurately assess the mitotic rate in the resected tumor specimen.

The RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665 trial was a prospective phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of imatinib 600 mg daily in the perioperative setting.34 The trial enrolled 50 patients, 30 with primary GISTs (group A) and 22 with recurrent metastatic GISTs (group B). Based on data from the metastatic setting revealing a time to treatment response of about 2.5 months, patients were treated with 8 to 12 weeks of preoperative imatinib followed by 2 years of adjuvant imatinib. Imatinib was stopped 24 hours preoperatively and resumed as soon as possible postoperatively. In group A, 7% of patients achieved a partial response (PR), 83% achieved stable disease, and 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were 83% and 93%, respectively. In group B, 4.5% of patients achieved a PR, 91% achieved stable disease, and 4.5% experienced progressive disease in the preoperative period; the 2-year PFS and OS were 77% and 91%, respectively. The results of this trial demonstrated the feasibility of using perioperative imatinib with minimal effects on surgical outcomes and set the rationale to use neoadjuvant imatinib in select patients with borderline resectable or rectal GISTs. Another EORTC pooled analysis from 10 sarcoma centers revealed that after a median of 10 months of neoadjuvant imatinib, 83.2% of patients achieved an R0 resection and only 1% progressed during treatment.35 After a median follow-up of 46 months, the 5-year disease-free survival and OS were 65% and 87%, respectively.

Mutational testing should be performed beforehand to ensure the tumor is imatinib-sensitive. If a KIT exon 9 mutation is identified, then 400 mg twice daily should be considered (given the benefit seen with 800 mg imatinib for advanced GIST patients), although there are no studies to confirm this practice. Neoadjuvant imatinib is recommended for a total of 6 to 12 months to ensure maximal tumor debulking, but with very close monitoring and surgical input for disease resistance and growth.14 Imatinib should be stopped 1 to 2 days preoperatively and resumed once the patient has recovered from surgery for a total of 3 years (pre-/postoperatively combined). Neoadjuvant therapy has been shown to be safe and effective, but there have been no randomized trials to assess survival.

What is appropriate surveillance for resected GISTs?

Surveillance

There have been no randomized studies to guide the management of surveillance after surgical resection and adjuvant therapy. There is no known optimal follow-up schedule, but several have been proposed.13,36 Among high-risk patients, it is suggested to image every 3 to 6 months during adjuvant therapy, followed by every 3 months for 2 years after discontinuing therapy, then every 6 months for another 3 years and annually thereafter for an additional 5 years. High-risk patients usually relapse within 1 to 3 years after finishing adjuvant therapy, while low-risk patients can relapse later given that their disease can be slower growing. It has been recommended that low-risk patients undergo imaging every 6 months for 5 years, with follow-up individualized thereafter. Very-low-risk patients may not require more than annual imaging. Because most relapses occur within the peritoneum or liver, imaging should encompass the abdomen and pelvis. Surveillance imaging usually consists of CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis. MRI scans can be utilized for patients at lower risk or who are out several years in order to avoid excess radiation exposure. MRI is also specifically helpful for rectal and esophageal lesions. Chest CT or chest radiograph and bone scan are not routinely required for follow-up.

Case Conclusion

The patient receives adjuvant imatinib and experiences grade 2 myalgias, periorbital edema, and macrocytic anemia, which result in imatinib discontinuation after 3 years of treatment. He is seen every 3 to 6 months and a contrast CT abdomen and pelvis is obtained every 6 months for 5 years. During this 5-year follow-up period, he does not have any clinical or radiographic evidence of disease recurrence.

Further follow-up of this patient is presented in the second article in this 2-part review of management of GISTs.

Key Points

- GISTs are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the GI tract and can occasionally occur in extragastrointestinal locations as well.

- GISTs encompass a heterogeneous family of tumor subsets with different natural histories, mutations, and TKI responsiveness.

- Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized GISTs, with cure rates greater than 50%.

- For very small (< 2 cm) esophagogastric GISTs, endoscopic ultrasound evaluation and follow-up is recommended.

- For tumors ≥ 2 cm, biopsy and excision is the standard approach.

- For localized GISTs, complete surgical resection (R0) is standard treatment, with no lymphadenectomy for clinically negative lymph nodes.

- Mutational analysis should be considered standard of practice. It can be helpful for confirming the diagnosis and can be predictive and prognostic in determining specific TKI therapy and dose.

- Adjuvant imatinib at a dose of 400 mg for 3 years is standard of care for GISTs that are at high risk of relapse and are imatinib-sensitive, and it is the only TKI approved for adjuvant therapy. Patients with PDGFRA D842V, NF1, BRAF or SDH-deficient GISTs should not receive adjuvant imatinib therapy.

- Neoadjuvant therapy can be utilized for sites where extensive resection would lead to significant morbidity. It should be given for 6 to 12 months, but patients need to be monitored closely for tumor growth.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal of the myenteric plexus. These tumors are rare, with about 1 case per 100,000 persons diagnosed in the United States annually, but may be incidentally discovered in up to 1 in 5 autopsy specimens of older adults.1,2 Epidemiologic risk factors include increasing age, with a peak incidence between age 60 and 65 years, male gender, black race, and non-Hispanic white ethnicity. Germline predisposition can also increase the risk of developing GISTs; molecular drivers of GIST include gain-of-function mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) gene, which both encode structurally similar tyrosine kinase receptors; germline mutations of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunit genes; and mutations associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.

GISTs most commonly involve the stomach, followed by the small intestine, but can arise anywhere within the GI tract (esophagus, colon, rectum, and anus). They can also develop outside the GI tract, arising from the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum. The majority of cases are localized or locoregional, whereas about 20% are metastatic at presentation.1 GISTs can occur in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatric GISTs represent a distinct subset marked by female predominance and gastric origin, are often multifocal, can sometimes have lymph node involvement, and typically lack mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes.

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the diagnosis and management of GISTs. Here, we review the evaluation and diagnosis of GISTs along with management of localized disease. Management of advanced disease is reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man with progressive iron deficiency and abdominal discomfort undergoes upper and lower endoscopy and is found to have a bulging mass within his abdominal cavity. He undergoes a computed tomography (CT) evaluation of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast, which reveals the presence of a 10-cm gastric mass, with no other lesions identified. He undergoes surgical resection of the mass and presents for review of his pathology and to discuss his treatment plan.

What histopathologic features are consistent with GIST?

What factors are used for risk stratification and to predict likelihood of recurrence?

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Most patients present with symptoms of overt or occult GI bleeding or abdominal discomfort, but a significant proportion of GISTs are discovered incidentally. Lymph node involvement is not typical, except for GISTs occurring in children and/or with rare syndromes. Most syndromic GISTs are multifocal and multicentric. After surgical resection, GISTs usually recur or metastasize within the abdominal cavity, including the omentum, peritoneum, or liver. These tumors rarely spread to the lungs, brain, or bones; when tumor spread does occur, it tends to be in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced disease who have been on multiple lines of therapy for a long duration of time.

The diagnosis usually can be made by histopathology. Specimens can be obtained by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)– or CT-guided methods, the latter of which carries a very small risk of contamination from percutaneous biopsy. In terms of morphology, GISTs can be spindle cell, epithelioid, or mixed neoplasms. Epithelioid tumors are more commonly seen in the stomach and are often PDGFRA-mutated or SDH-deficient. The differential diagnosis includes other soft-tissue GI wall tumors such as leiomyosarcomas/leiomyomas, germ cell tumors, lymphomas, fibromatosis, and neuroendocrine and neurogenic tumors. A unique feature of GISTs that differentiates them from leiomyomas is near universal expression of CD117 by immunohistochemistry (IHC); this characteristic has allowed pathologists and providers to accurately distinguish true GISTs from other GI mesenchymal tumors.3 Recently, DOG1 (discovered on GIST1) immunoreactivity has been found to be helpful in identifying patients with CD117-negative GISTs. Initially identified through gene expression analysis of GISTs, DOG1 IHC can identify the common mutant c-Kit-driven CD117-positive GISTs as well as the rare CD117-negative GISTs, which are often driven by mutated PDGFRA.4 Importantly, IHC for KIT and DOG1 are not surrogates for mutational status, nor are they predictive of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sensitivity. If IHC of a tumor specimen is CD117- and DOG1-negative, the specimen can be sent for KIT and PDGFRA mutational analysis to confirm the diagnosis. If analysis reveals that these genes are wild-type, then IHC staining for SDH B (SDHB) should follow to assess for an SDH-deficient GIST (negative staining).

Risk Stratification for Recurrence

The clinical behavior of GISTs can be variable. Some are indolent, while others behave more aggressively, with a greater malignant potential and a higher propensity to recur and metastasize. Clinical and pathologic features can provide important prognostic information that allows providers to risk-stratify patients. Various institutions have assessed prognostic variables for GISTs. In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a GIST workshop that proposed an approach to estimating metastatic risk based on tumor size and mitotic index (NIH or Fletcher criteria).5 Joensuu et al later proposed a modification of the NIH risk classification to include tumor location and tumor rupture (modified NIH criteria or Joensuu criteria).6-8 Similarly, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) identified tumor site as a prognostic factor, with gastric GISTs having the best prognosis (AFIP-Miettinen criteria).9-11 Tabular schemes were designed which stratified patients into discrete groups with ranges for mitotic rate and tumor size. Nomograms for ease of use were then constructed utilizing a bimodal mitotic rate and included tumor site and size.12 Finally, contour maps were developed, which have the advantage of evaluating mitotic rate and tumor size as continuous nonlinear variables and also include tumor site and rupture (associated with a high risk of peritoneal metastasis) separately, further improving risk assessment. These contour maps have been validated against pooled data from 10 series (2560 patients).13 High-risk features identified from these studies include tumor location, size, mitotic rate and tumor rupture and are now used for deciding on the use of adjuvant imatinib and as requirements to enter clinical trials assessing adjuvant therapy for resected GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient’s operative and pathology reports indicate that the tumor is a spindle cell neoplasm of the stomach that is positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. Resection margins are negative. There are 10 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPF). Per the operative report, there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. Thus, while his GIST was gastric, which generally has a more favorable prognosis, the tumor harbors high-risk features based on its size and mitotic index.

What further testing should be requested?

Molecular Alterations

It is recommended that a mutational analysis be performed as part of the diagnostic work-up of all GISTs.14 Mutational analysis can provide prognostic and predictive information for sensitivity to imatinib and should be considered standard of care. It may also be useful for confirming a GIST diagnosis, or, if negative, lead to further evaluation with an IHC stain for SDHB. The c-Kit receptor is a member of the tyrosine kinase family and, through direct interactions with stem cell factor (SCF), can upregulate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, and JAK-STAT pathways, resulting in transcription and translation of genes that enhance cell growth and survival.15 The cell of origin of GISTs, the interstitial cells of Cajal, are dependent on the SCF–c-Kit interaction for development.16 Likewise, the large majority of GISTs (about 70%) are driven by upregulation and constitutive activation of c-Kit, which is normally autoinhibited. About 80% of KIT mutations involve exon 11; these GISTs are most often associated with a gastric location and are associated with a favorable recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate with surgery alone.17 KIT exon 9 mutations are much less common, encompassing only about 10% of GIST KIT mutations, and GISTs with these mutations are more likely to arise from the small bowel.17

About 8% of GISTs harbor gain-of-function PDGFRA driver mutations rendering constitutively active PDGFRA.18 PDGFRA mutations are mutually exclusive from KIT mutations, and PDGFRA-mutated tumors most often occur in the stomach. PDGFRA mutations generally are associated with a lower mitotic rate and gastric location. Identification of the PDGFRA D842V mutation on exon 18, which is the most common, is important, as it is associated with imatinib resistance, and these patients should not be offered imatinib.19

Several other mutations associated with GISTs outside of the KIT and PDGFRA spectrum have been identified. About 10% of GISTs are wildtype for KIT and PDGFRA, and not all KIT/PDGFRA-wildtype GISTs are imatinib-sensitive and/or respond to other TKIs.18 These tumors may harbor aberrations in SDH and NF1, or less commonly, BRAF V600E, FGFR, and NTRK.20,21 SDH subunits B, C and D play a role in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain. Germline mutations in these SDH subunits can result in the Carney-Stratakis syndrome characterized by the dyad of multifocal GISTs and multicentric paragangliomas.22 This syndrome is most likely to manifest in the pediatric or young adult population. In contradistinction is the Carney triad, which is associated with acquired loss of function of the SDHC gene due to promoter hypermethylation. This syndrome classically occurs in young women and is characterized by an indolent-behaving triad of multicentric GISTs, non-adrenal paragangliomas, and pulmonary chondromas.23 Like PDGFRA D842V–mutated GISTs, SDH-deficient and NF1-associated GISTs are considered imatinib resistant, and these patients should not be offered imatinib therapy.14

Case Continued

The patient’s GIST is found to harbor a KIT exon 11 single codon deletion. He appears anxious and asks to have everything done to prevent his GIST from coming back and to improve his lifespan.

What are the next steps in the management of this patient?

Management

A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of all GISTs is essential and includes input from radiology, gastroenterology, pathology, medical and surgical oncology, nuclear medicine, and nursing.

Surgical Resection

Small esophagogastric and duodenal GISTs ≤ 2 cm can be asymptomatic and managed with serial endoscopic surveillance, typically every 6 to 12 months, with biopsies if the tumors increase in size. GISTs larger than 2 cm require surgical resection, with resection of the full pseudocapsule and an R0 resection, if possible, since larger GISTs carry a higher risk of growth and recurrence. If an R0 resection would lead to significant morbidity or functional sequelae, an R1 may suffice. Rectal GISTs are an exception, where microscopic margins have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of local failure.24 It is important to explore the abdomen thoroughly for peritoneal, rectovaginal, and vesicular implants and metastasis to the liver. A formal lymph node dissection is not necessary because lymph nodes are rarely involved and should only be removed when clinically suspicious. Tumor rupture must be avoided. A laparoscopic approach should only be considered for smaller tumors, since there is a risk of tumor rupture with larger tumors.14

When is adjuvant imatinib indicated?

Adjuvant Imatinib

Among patients with local or locally advanced GISTs, the risk of death from recurrence with surgery alone can be high, with a historical 5-year overall survival (OS) of about 35%.25 As a result, multiple studies have assessed the benefit of adjuvant imatinib, which is now considered standard of care for patients with imatinib-sensitive, high-risk GISTs. In addition to inhibiting BCR-ABL, imatinib mesylate inhibits multiple other receptor tyrosine kinases, including PDGFR, SCF and c-Kit. As a result, imatinib has demonstrated in vitro inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis and clinical activity against GISTs expressing CD117.26 Importantly, adjuvant imatinib should only be offered to patients with imatinib-sensitive mutations, such as KIT exon 11 and KIT exon 9 mutations. Adjuvant imatinib should not be offered to patients with imatinib-insensitive mutations such as PDGFR 842V, NF1, or BRAF-related or SDH-deficient GISTs.

The ACOSOG Z9000 was the first study of adjuvant imatinib in patients with resected GISTs.25 This was a single-arm, phase 2 study involving 106 patients with surgically resected GISTs deemed high-risk for recurrence, defined as size > 10 cm, tumor rupture, or up to 4 peritoneal implants. Patients were treated with imatinib 400 mg daily for 1 year. The primary and secondary endpoints were OS and RFS, respectively. Long-term follow-up of this study demonstrated 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of 99%, 97%, and 83%, and 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS of 96%, 60%, and 40%, which compared favorably with historical controls. In a multivariable analysis, increasing tumor size, small bowel location, KIT exon 9 mutation, high mitotic rate, and older age were independent risk factors for a poor RFS.25 It is important to note that the benefit of adjuvant imatinib waned after discontinuation of therapy, creating a rationale to study adjuvant imatinib for longer periods of time.

As a result of the promising phase 2 data, ACOSOG opened a phase 3 randomized trial (Z9001) comparing 1 year of adjuvant imatinib to placebo among patients with surgically resected GISTs that were > 3 cm in size and that stained positive for CD117 on pathology. The trial accrued 713 patients and was stopped early at a planned interim analysis, which revealed a 1-year RFS of 98% for imatinib versus 83% for placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 0.35; P < 0.001). The 1-year OS did not differ between the 2 arms (92.2% vs 99.7%; HR, 0.66; P = 0.47).27 When comparing the 2 arms, imatinib was associated with a higher RFS among patients with a KIT exon 11 deletion, but not among patients with other KIT mutation types, PDGFRA mutations, or who were KIT/PDGFRA wildtype.28 Imatinib was granted approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the adjuvant treatment of high-risk GISTs based on the results of the ACOSOG Z9001 trial.

The EORTC 62024 study was a randomized placebo-controlled trial assessing the benefit of 2 years of adjuvant imatinib.29 Patients had to be considered intermediate or high risk per the 2002 NIH consensus classification to be eligible. The trial enrolled 918 patients. The 5-year OS rate, the original primary endpoint, did not differ between the 2 groups (100% vs 99%). The 3-year and 5-year RFS rates, secondary endpoints, were significantly longer among patients treated with imatinib (84% vs 66% and 69% vs 63%, respectively). Again, it was noted that the benefit of imatinib waned over time after treatment discontinuation.

The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG XVIII) trial was a prospective randomized phase 3 trial that compared 3 years versus 1 year of adjuvant imatinib.30 Patients had to be enrolled within 12 weeks of the postoperative period and had to have GISTs that were CD117-positive and with a high estimated risk of recurrence, per the modified NIH consensus criteria (size > 10 cm, > 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, diameter > 5 cm with mitotic count > 5, or tumor rupture before or at surgery). Three years of adjuvant imatinib was associated with a 54% reduction in the hazard for recurrence at 5 years (65.6% vs 47.9%; HR, 0.46; P < 0.001) and a 55% reduction in the hazard for death at 5 years (OS 92% vs 81.7%; HR, 0.45; P = 0.02). Based on the results of this study, the FDA granted approval for the use of 3 years of adjuvant imatinib in patients with high-risk resected GISTs.

The observation that a longer duration of adjuvant imatinib was associated with superior RFS and OS led to studies to further explore longer durations of adjuvant imatinib. The PERSIST-5 (Postresection Evaluation of Recurrence-free Survival for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors With 5 Years of Adjuvant Imatinib) was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 prospective study of adjuvant imatinib with a primary endpoint of RFS after 5 years.31 Patients had to have an intermediate or high risk of recurrence, which included GISTs at any site > 2 cm with > 5 mitoses per 50 HPF or nongastric GISTs that were ≥ 5 cm. With 91 patients enrolled, the estimated 5-year RFS was 90% and the OS was 95%. Of note, about half of the patients stopped treatment early due to a variety of reasons, including patient choice or adverse events. Importantly, there were no recurrences in patients with imatinib-sensitive mutations while on therapy. We know that in patients at high risk of relapse, adjuvant imatinib delays recurrence and improves survival, but whether any patients are cured, or their survival curves are just shifted to the right, is unknown. Only longer follow-up of existing studies, and the results of newer trials utilizing longer durations of adjuvant treatment, will help to determine the real value of adjuvant therapy for GIST patients.32 Based on this study, it would be reasonable to discuss a longer duration of imatinib with patients deemed to be at very high risk of recurrence and who are tolerating therapy well. We are awaiting the data from the randomized phase 3 Scandinavian Sarcoma Group XII trial comparing 5 years versus 3 years of adjuvant imatinib therapy, and from the French ImadGIST trial of adjuvant imatinib for 3 versus 6 years. A summary of the aforementioned key adjuvant trials is shown in the Table.

When imatinib is commenced, careful monitoring for treatment toxicities and drug interactions should ensue in order to improve compliance. Dose density should be maintained if possible, as retrospective studies suggest suboptimal plasma levels are associated with a worse outcome.33

When should neoadjuvant imatinib be considered?

Neoadjuvant Imatinib

Neoadjuvant imatinib should be considered for patients requiring total gastrectomy, esophagectomy, or abdominoperineal resection of the rectum in order to reduce tumor size, limit subsequent surgical morbidity, mitigate tumor bleeding and rupture, and aid with organ preservation. Patients with rectal GISTs that may otherwise warrant an abdominoperineal resection should be offered a trial of imatinib in the neoadjuvant setting. There is no evidence for the use of any other TKI aside from imatinib in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. With neoadjuvant imatinib, it is difficult to accurately assess the mitotic rate in the resected tumor specimen.

The RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665 trial was a prospective phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of imatinib 600 mg daily in the perioperative setting.34 The trial enrolled 50 patients, 30 with primary GISTs (group A) and 22 with recurrent metastatic GISTs (group B). Based on data from the metastatic setting revealing a time to treatment response of about 2.5 months, patients were treated with 8 to 12 weeks of preoperative imatinib followed by 2 years of adjuvant imatinib. Imatinib was stopped 24 hours preoperatively and resumed as soon as possible postoperatively. In group A, 7% of patients achieved a partial response (PR), 83% achieved stable disease, and 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were 83% and 93%, respectively. In group B, 4.5% of patients achieved a PR, 91% achieved stable disease, and 4.5% experienced progressive disease in the preoperative period; the 2-year PFS and OS were 77% and 91%, respectively. The results of this trial demonstrated the feasibility of using perioperative imatinib with minimal effects on surgical outcomes and set the rationale to use neoadjuvant imatinib in select patients with borderline resectable or rectal GISTs. Another EORTC pooled analysis from 10 sarcoma centers revealed that after a median of 10 months of neoadjuvant imatinib, 83.2% of patients achieved an R0 resection and only 1% progressed during treatment.35 After a median follow-up of 46 months, the 5-year disease-free survival and OS were 65% and 87%, respectively.

Mutational testing should be performed beforehand to ensure the tumor is imatinib-sensitive. If a KIT exon 9 mutation is identified, then 400 mg twice daily should be considered (given the benefit seen with 800 mg imatinib for advanced GIST patients), although there are no studies to confirm this practice. Neoadjuvant imatinib is recommended for a total of 6 to 12 months to ensure maximal tumor debulking, but with very close monitoring and surgical input for disease resistance and growth.14 Imatinib should be stopped 1 to 2 days preoperatively and resumed once the patient has recovered from surgery for a total of 3 years (pre-/postoperatively combined). Neoadjuvant therapy has been shown to be safe and effective, but there have been no randomized trials to assess survival.

What is appropriate surveillance for resected GISTs?

Surveillance