User login

Focus on long-COVID: Perimenopause and post-COVID chronic fatigue

Long COVID (postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC) is an emerging syndrome that affects 50% to 70% of people who survive COVID-19 for up to 3 months or longer after acute disease.1 It is a multisystem condition that causes dysfunction of respiratory, cardiac, and nervous tissue, at least in part likely due to alterations in cellular energy metabolism and reduced oxygen supply to tissue.3 Patients who have had SARS-CoV-2 infection report persistent symptoms and signs that affect their quality of life. These may include neurocognitive, cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal symptoms; loss of taste and smell; and constitutional symptoms.2 There is no one test to determine if symptoms are due to COVID-19.3

Acute COVID-19 mortality risk factors include increasing age, chronic comorbidities, and male sex. However, long COVID risk factors are quite different. A meta-analysis and review of 20 articles that met inclusion criteria (n = 13,340 study participants), limited by pooling of crude estimates, found that risk factors were female sex and severity of acute disease.4 A second meta-analysis of 37 studies with 1 preprint found that female sex and comorbidities such as pulmonary disease, diabetes, and obesity were risk factors for long COVID.5 Qualitative analysis of single studies (n = 18 study participants) suggested that older adults can develop more long COVID symptoms than younger adults, but this association between advancing age and long COVID was not supported when data were pooled into a meta-analysis.3 However, both single studies (n = 16 study participants) and the meta-analysis (n = 7 study participants) did support female sex as a risk factor for long COVID, along with single studies suggesting increased risk with medical comorbidities for pulmonary disease, diabetes, and organ transplantation.

Perimenopause

Perimenopause: A temporary disruption to physiologic ovarian steroid hormone production following COVID could acutely exacerbate symptoms of perimenopause and menopause.

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, MSCP

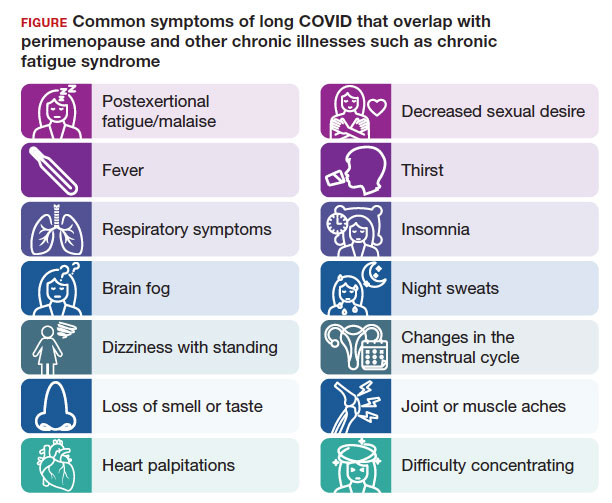

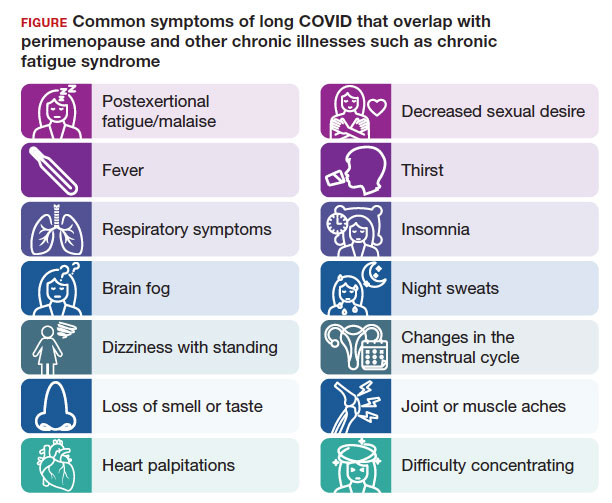

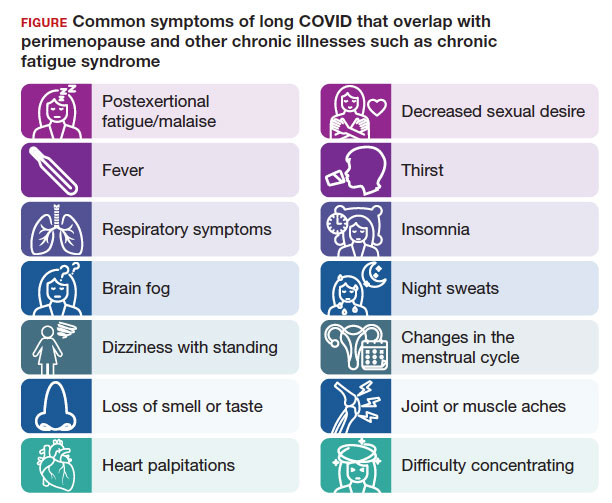

The higher prevalence of long COVID in women younger than 50 years6 supports the overlap that studies have shown between symptoms of long COVID and perimenopause,7 as the median age of natural menopause is 51 years. Thus, health care providers need to differentiate between long COVID and other conditions, such as perimenopause, which share similar symptoms (FIGURE). Perimenopause might be diagnosed as long COVID, or the 2 might affect each other.

Symptoms of long COVID include fatigue, brain fog, and increased heart rate after recovering from COVID-19 and may continue or increase after an initial infection.8 Common symptoms of perimenopause and menopause, which also could be seen with long COVID, include typical menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, or disrupted sleep; changes in mood including dysthymia, depression, anxiety, or emotional lability; cognitive concerns such as brain fog or decreased concentration; and decreased stamina, fatigue, joint and muscle pains, or more frequent headaches. Therefore, women in their 40s or 50s with persistent symptoms after having COVID-19 without an alternative diagnosis, and who present with menstrual irregularity,9hot flashes, or night sweats, could be having an exacerbation of perimenopausal symptoms, or they could be experiencing a combination of long COVID and perimenopausal symptoms.

- Consider long COVID, versus perimenopause, or both, in women aged younger than 50 years

- Estradiol, which has been shown to alleviate perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms, also has been shown to have beneficial effects during acute COVID-19 infection

- Hormone therapy could improve symptoms of perimenopause and long COVID if some of the symptoms are due to changes in ovary function

Continue to: Potential pathophysiology...

Potential pathophysiology

Inflammation is likely to be critical in the pathogenesis of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC. Individuals with long COVID have elevated inflammatory markers for several months.10 The chronic inflammation associated with long COVID could cause disturbances in the ovary and ovarian hormone production.2,10,11

During perimenopause, the ovary is more sensitive to illnesses such as COVID-19and to stress. The current theory is that COVID-19 affects the ovary with declines in ovarian reserve and ovarian function7 and with potential disruptions to the menstrual cycle, gonadal function, and ovarian sufficiency that lead to issues with menopause or fertility, as well as symptom exacerbation around menstruation.12 Another theory is that SARS-CoV-2 infection affects ovary hormone production, as there is an abundance of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptors on ovarian and endometrial tissue.11 Thus, it makes sense that long COVID could bring on symptoms of perimenopause or menopause more acutely or more severely or lengthen the duration of perimenopausal symptoms.

Perimenopause is the transitional period prior to menopause, when the ovaries gradually produce fewer hormones and is associated with erratic hormonal fluctuations. The length of this transitional period varies from 4 to 10 years. Ethnic variations in the duration of hot flashes have been found, noting that Black and Hispanic women have them for an average of 8 to 10 years (longer), White women for an average of 7 years, and Asian, Japanese, and Chinese women for an average of 5 to 6 years (shorter).17

What should health care providers ask?

Distinguishing perimenopause from long COVID. It is important to try to differentiate between perimenopause and long COVID, and it is possible to have both, with long COVID exacerbating the menopausal symptoms.7,8 Health care providers should be alert to consider perimenopause if women present with shorter or longer cycles (21-40 days), missed periods (particularly 60 days or 2 months), or worsening perimenopausal mood, migraines, insomnia, or hot flashes. Clinicians should actively enquire about all of these symptoms.

Moreover, if a perimenopausal woman reports acutely worsening symptoms after COVID-19, health care providers should address the perimenopausal symptoms and determine whether hormone therapy is appropriate and could improve their symptoms. Women do not need to wait until they go 1 year without a period to be treated with hormone therapy to improve perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. If women with long COVID have perimenopause or menopause symptoms, they should have access to evidence-based information and discuss menopausal hormone therapy if appropriate. Hormone therapy could improve both perimenopausal symptoms and the long COVID symptoms if some of the symptoms are due to changes in ovary function. Health care providers could consider progesterone or antidepressants during the second half of the cycle (luteal phase) or estrogen combined with progesterone for the entire cycle.18

For health care providers working in long COVID clinics, in addition to asking when symptoms started, what makes symptoms worse, the frequency of symptoms, and which activities are affected, ask about perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. If a woman has irregular periods, sleep disturbances, fatigue, or mood changes, consider that these could be related to long COVID, perimenopause, or both.8,18 Be able to offer treatment or refer patients to a women’s health specialist who can assess and offer treatment.

A role for vitamin D? A recent retrospective case-matched study found that 6 months after hospital discharge, patients with long COVID had lower levels of 25(OH) vitamin D with the most notable symptom being brain fog.19 Thus, there may be a role for vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy in those being discharged after hospitalization. Vitamin D levels and supplementation have not been otherwise evaluated to date.

Lifestyle strategies for women with perimenopause and long COVID

Lifestyle strategies should be encouraged for women during perimenopause and long COVID. This includes good nutrition (avoiding carbs and sweets, particularly before menses), getting at least 7 hours of sleep and using sleep hygiene (regular bedtimes, sleep regimen, no late screens), getting regular exercise 5 days per week, reducing stress, avoiding excess alcohol, and not smoking. All of these factors can help women and their ovarian function during this period of ovarian fluctuations.

The timing of menopause and COVID may coincide with midlife stressors, including relationship issues (separations or divorce), health issues for the individual or their partner, widowhood, parenting challenges (care of young children, struggles with adolescents, grown children returning home), being childless, concerns about aging parents and caregiving responsibilities, as well as midlife career, community, or education issues—all of which make both long COVID and perimenopause more challenging to navigate.

Need for research

There is a need for future research to understand the epidemiologic basis and underlying biological mechanisms of sex differences seen in women with long COVID. Studying the effects of COVID-19 on ovarian function could lead to a better understanding of perimenopause, what causes ovarian failure to speed up, and possibly ways to slow it down8 since there are health risks of early menopause.16

References

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D, GómezMayordomo V, et al. Defining post-COVID symptoms (postacute COVID, long COVID, persistent post-COVID): an integrative classification. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2621. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052621

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601-615. doi: 10.1038/s41591 -021-01283-z

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

- Maglietta G, Diodati F, Puntoni M, et al. Prognostic factors for post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1541. doi: 10.3390 /jcm11061541

- Notarte KI, de Oliveira MHS, Peligro PJ, et al. Age, sex and previous comorbidities as risk factors not associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection for long COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:7314. doi: 10.3390 /jcm11247314

- Sigfrid L, Drake TM, Pauley E, et al. Long COVID in adults discharged from UK hospitals after COVID-19: a prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;8:100186. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100186

- Pollack B, von Saltza E, McCorkell L, et al. Female reproductive health impacts of long COVID and associated illnesses including ME/CFS, POTS, and connective tissue disorders: a literature review. Front Rehabil Sci. 2023;4:1122673. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1122673

- Stewart S, Newson L, Briggs TA, et al. Long COVID risk - a signal to address sex hormones and women’s health. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;11:100242. doi: 10.1016 /j.lanepe.2021.100242

- Li K, Chen G, Hou H, et al. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:260-267. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2020.09.020

- Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-tomoderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:210216. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x

- Sharp GC, Fraser A, Sawyer G, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the menstrual cycle: research gaps and opportunities. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:691-700. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab239

- Ding T, Wang T, Zhang J, et al. Analysis of ovarian injury associated with COVID-19 disease in reproductive-aged women in Wuhan, China: an observational study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:635255. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.635255

- Huang B, Cai Y, Li N, et al. Sex-based clinical and immunological differences in COVID-19. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:647. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06313-2

- Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113364. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Klein SL, Levin ER. Estradiol, progesterone, immunomodulation, and COVID-19 outcomes. Endocrinology. 2020;161:bqaa127. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqaa127

- The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:531-539. doi:10.1001 /jamainternmed.2014.8063

- Newson L, Lewis R, O’Hara M. Long COVID and menopause - the important role of hormones in long COVID must be considered. Maturitas. 2021;152:74. doi: 10.1016 /j.maturitas.2021.08.026

- di Filippo L, Frara S, Nannipieri F, et al. Low Vitamin D levels are associated with long COVID syndrome in COVID-19 survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:e1106-e1116. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad207

Continue to: Chronic fatigue syndrome...

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome: A large number of patients have “post-COVID conditions” affecting everyday function, including depression/anxiety, insomnia, and chronic fatigue (with a 3:1 female predominance)

Alexandra Kadl, MD

After 3 years battling acute COVID-19 infections, we encounter now a large number of patients with PASC— also known as “long COVID,” “COVID long-hauler syndrome,” and “post-COVID conditions”—a persistent multisystem syndrome that impacts everyday function.1 As of October 2023, there are more than 100 million COVID-19 survivors reported in the United States; 10% to 85% of COVID survivors2-4 may show lingering, life-altering symptoms after recovery. Common reported symptoms include fatigue, depression/ anxiety, insomnia, and brain fog/difficulty concentrating, which are particularly high in women who often had experienced only mild acute COVID-19 disease and were not even hospitalized. More recently, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) has been recognized as major component of PASC5 with a 3:1 female predominance.6 Up to 75% of patients with this diagnosis are not able to maintain their jobs and normal life, and up to 25% are so disabled that they are bedbound.6

Diagnosis

Although illnesses resembling CFS have been reported for more than 200 years,7 the diagnosis of CFS/ME remains difficult to make. There is a likely underreporting due to fear of being labeled as malingering when reaching out to health care providers, and there is a reporting bias toward higher socioeconomic groups due to better access to health care. The current criteria for the diagnosis of CFS/ME include the following 3 components8:

- substantial impairment in the ability to function for more than 6 months, accompanied by profound fatigue, not alleviated by rest

- post-exertional malaise (PEM; prolonged, disabling exacerbation of the patient’s baseline symptoms after exercise)

- non-refreshing sleep, PLUS either cognitive impairment or orthostatic intolerance.

Pathophysiology

Originally found to evolve in a small patient population with Epstein-Barr virus infection and Lyme disease, CFS/ME has moved to centerstage after the COVID-19 pandemic. While the diagnosis of COVID-19–related CFS/ME has advanced in the field, a clear mechanistic explanation of why it occurs is still missing. Certain risk factors have been identified for the development of CFS/ME, including female sex, reactivation of herpesviruses, and presence of connective tissue disorders; however, about one-third of patients with CFS/ME do not have identifiable risk factors.9,10 Persistence of viral particles11 and prolonged inflammatory states are speculated to affect the nervous system and mitochondrial function and metabolism. Interestingly, there is no correlation between severity of initial COVID-19 illness and the development of CFS/ME, similar to observations in non–COVID-19–related CFS/ME.

Proposed therapy

There is currently no proven therapy for CFS/ME. At this time, several immunomodulatory, antiviral, and neuromodulator drugs are being tested in clinical trial networks around the world.12 Usual physical therapy with near maximum intensity has been shown to exacerbate symptoms and often results in PEM, which is described as a “crash” or “full collapse” by patients. The time for recovery after such episodes can be several days.13

Instead, the focus should be on addressing “treatable” concomitant symptoms, such as sleep disorders, anxiety and depression, and chronic pain. Lifestyle changes, avoidance of triggers, and exercise without over exertion are currently recommended to avoid incapacitating PEM.

Gaps in knowledge

There is a large knowledge gap regarding the pathophysiology, prevention, and therapy for CFS/ME. Many health care practitioners are not familiar with the disease and have focused on measurable parameters of exercise limitations and fatigue, such as anemias and lung and cardiac impairments, thus treating CFS/ME as a form of deconditioning. Given the large number of patients who recovered from acute COVID-19 that are now disabled due to CFS/ME, a patient-centered research opportunity has arisen. Biomedical/mechanistic research is ongoing, and well-designed clinical trials evaluating pharmacologic intervention as well as tailored exercise programs are needed.

Conclusion

General practitioners and women’s health specialists need to be aware of CFS/ME, especially when managing patients with long COVID. They also need to know that typical physical therapy may worsen symptoms. Furthermore, clinicians should shy away from trial drugs with a theoretical benefit outside of a clinical trial. ●

- Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) has been recognized as a major component of PASC

- Typical physical therapy has been shown to exacerbate symptoms of CFS/ME

- Treatment should focus on addressing “treatable” concomitant symptoms, lifestyle changes, avoidance of triggers, and exercise without over exertion

References

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, et al. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102-e107. doi: 10.1016 /S1473-3099(21)00703-9

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, et al. Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1593-1607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022 -00846-2

- Pavli A, Theodoridou M, Maltezou HC. Post-COVID syndrome: incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch Med Res. 2021;52:575-581. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010

- Kedor C, Freitag H, Meyer-Arndt L, et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5104. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32507-6

- Bateman L, Bested AC, Bonilla HF, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: essentials of diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:28612878. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.004

- Wessely S. History of postviral fatigue syndrome. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:919-941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072521

- Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. National Academies Press; 2015. doi: 10.17226/19012

- Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

- Hanson MR. The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19:e1011523. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011523

- Scheibenbogen C, Bellmann-Strobl JT, Heindrich C, et al. Fighting post-COVID and ME/CFS—development of curative therapies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1194754. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1194754

- Stussman B, Williams A, Snow J, et al. Characterization of post-exertional malaise in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Neurol. 2020;11:1025. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01025

Long COVID (postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC) is an emerging syndrome that affects 50% to 70% of people who survive COVID-19 for up to 3 months or longer after acute disease.1 It is a multisystem condition that causes dysfunction of respiratory, cardiac, and nervous tissue, at least in part likely due to alterations in cellular energy metabolism and reduced oxygen supply to tissue.3 Patients who have had SARS-CoV-2 infection report persistent symptoms and signs that affect their quality of life. These may include neurocognitive, cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal symptoms; loss of taste and smell; and constitutional symptoms.2 There is no one test to determine if symptoms are due to COVID-19.3

Acute COVID-19 mortality risk factors include increasing age, chronic comorbidities, and male sex. However, long COVID risk factors are quite different. A meta-analysis and review of 20 articles that met inclusion criteria (n = 13,340 study participants), limited by pooling of crude estimates, found that risk factors were female sex and severity of acute disease.4 A second meta-analysis of 37 studies with 1 preprint found that female sex and comorbidities such as pulmonary disease, diabetes, and obesity were risk factors for long COVID.5 Qualitative analysis of single studies (n = 18 study participants) suggested that older adults can develop more long COVID symptoms than younger adults, but this association between advancing age and long COVID was not supported when data were pooled into a meta-analysis.3 However, both single studies (n = 16 study participants) and the meta-analysis (n = 7 study participants) did support female sex as a risk factor for long COVID, along with single studies suggesting increased risk with medical comorbidities for pulmonary disease, diabetes, and organ transplantation.

Perimenopause

Perimenopause: A temporary disruption to physiologic ovarian steroid hormone production following COVID could acutely exacerbate symptoms of perimenopause and menopause.

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, MSCP

The higher prevalence of long COVID in women younger than 50 years6 supports the overlap that studies have shown between symptoms of long COVID and perimenopause,7 as the median age of natural menopause is 51 years. Thus, health care providers need to differentiate between long COVID and other conditions, such as perimenopause, which share similar symptoms (FIGURE). Perimenopause might be diagnosed as long COVID, or the 2 might affect each other.

Symptoms of long COVID include fatigue, brain fog, and increased heart rate after recovering from COVID-19 and may continue or increase after an initial infection.8 Common symptoms of perimenopause and menopause, which also could be seen with long COVID, include typical menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, or disrupted sleep; changes in mood including dysthymia, depression, anxiety, or emotional lability; cognitive concerns such as brain fog or decreased concentration; and decreased stamina, fatigue, joint and muscle pains, or more frequent headaches. Therefore, women in their 40s or 50s with persistent symptoms after having COVID-19 without an alternative diagnosis, and who present with menstrual irregularity,9hot flashes, or night sweats, could be having an exacerbation of perimenopausal symptoms, or they could be experiencing a combination of long COVID and perimenopausal symptoms.

- Consider long COVID, versus perimenopause, or both, in women aged younger than 50 years

- Estradiol, which has been shown to alleviate perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms, also has been shown to have beneficial effects during acute COVID-19 infection

- Hormone therapy could improve symptoms of perimenopause and long COVID if some of the symptoms are due to changes in ovary function

Continue to: Potential pathophysiology...

Potential pathophysiology

Inflammation is likely to be critical in the pathogenesis of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC. Individuals with long COVID have elevated inflammatory markers for several months.10 The chronic inflammation associated with long COVID could cause disturbances in the ovary and ovarian hormone production.2,10,11

During perimenopause, the ovary is more sensitive to illnesses such as COVID-19and to stress. The current theory is that COVID-19 affects the ovary with declines in ovarian reserve and ovarian function7 and with potential disruptions to the menstrual cycle, gonadal function, and ovarian sufficiency that lead to issues with menopause or fertility, as well as symptom exacerbation around menstruation.12 Another theory is that SARS-CoV-2 infection affects ovary hormone production, as there is an abundance of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptors on ovarian and endometrial tissue.11 Thus, it makes sense that long COVID could bring on symptoms of perimenopause or menopause more acutely or more severely or lengthen the duration of perimenopausal symptoms.

Perimenopause is the transitional period prior to menopause, when the ovaries gradually produce fewer hormones and is associated with erratic hormonal fluctuations. The length of this transitional period varies from 4 to 10 years. Ethnic variations in the duration of hot flashes have been found, noting that Black and Hispanic women have them for an average of 8 to 10 years (longer), White women for an average of 7 years, and Asian, Japanese, and Chinese women for an average of 5 to 6 years (shorter).17

What should health care providers ask?

Distinguishing perimenopause from long COVID. It is important to try to differentiate between perimenopause and long COVID, and it is possible to have both, with long COVID exacerbating the menopausal symptoms.7,8 Health care providers should be alert to consider perimenopause if women present with shorter or longer cycles (21-40 days), missed periods (particularly 60 days or 2 months), or worsening perimenopausal mood, migraines, insomnia, or hot flashes. Clinicians should actively enquire about all of these symptoms.

Moreover, if a perimenopausal woman reports acutely worsening symptoms after COVID-19, health care providers should address the perimenopausal symptoms and determine whether hormone therapy is appropriate and could improve their symptoms. Women do not need to wait until they go 1 year without a period to be treated with hormone therapy to improve perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. If women with long COVID have perimenopause or menopause symptoms, they should have access to evidence-based information and discuss menopausal hormone therapy if appropriate. Hormone therapy could improve both perimenopausal symptoms and the long COVID symptoms if some of the symptoms are due to changes in ovary function. Health care providers could consider progesterone or antidepressants during the second half of the cycle (luteal phase) or estrogen combined with progesterone for the entire cycle.18

For health care providers working in long COVID clinics, in addition to asking when symptoms started, what makes symptoms worse, the frequency of symptoms, and which activities are affected, ask about perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. If a woman has irregular periods, sleep disturbances, fatigue, or mood changes, consider that these could be related to long COVID, perimenopause, or both.8,18 Be able to offer treatment or refer patients to a women’s health specialist who can assess and offer treatment.

A role for vitamin D? A recent retrospective case-matched study found that 6 months after hospital discharge, patients with long COVID had lower levels of 25(OH) vitamin D with the most notable symptom being brain fog.19 Thus, there may be a role for vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy in those being discharged after hospitalization. Vitamin D levels and supplementation have not been otherwise evaluated to date.

Lifestyle strategies for women with perimenopause and long COVID

Lifestyle strategies should be encouraged for women during perimenopause and long COVID. This includes good nutrition (avoiding carbs and sweets, particularly before menses), getting at least 7 hours of sleep and using sleep hygiene (regular bedtimes, sleep regimen, no late screens), getting regular exercise 5 days per week, reducing stress, avoiding excess alcohol, and not smoking. All of these factors can help women and their ovarian function during this period of ovarian fluctuations.

The timing of menopause and COVID may coincide with midlife stressors, including relationship issues (separations or divorce), health issues for the individual or their partner, widowhood, parenting challenges (care of young children, struggles with adolescents, grown children returning home), being childless, concerns about aging parents and caregiving responsibilities, as well as midlife career, community, or education issues—all of which make both long COVID and perimenopause more challenging to navigate.

Need for research

There is a need for future research to understand the epidemiologic basis and underlying biological mechanisms of sex differences seen in women with long COVID. Studying the effects of COVID-19 on ovarian function could lead to a better understanding of perimenopause, what causes ovarian failure to speed up, and possibly ways to slow it down8 since there are health risks of early menopause.16

References

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D, GómezMayordomo V, et al. Defining post-COVID symptoms (postacute COVID, long COVID, persistent post-COVID): an integrative classification. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2621. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052621

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601-615. doi: 10.1038/s41591 -021-01283-z

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

- Maglietta G, Diodati F, Puntoni M, et al. Prognostic factors for post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1541. doi: 10.3390 /jcm11061541

- Notarte KI, de Oliveira MHS, Peligro PJ, et al. Age, sex and previous comorbidities as risk factors not associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection for long COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:7314. doi: 10.3390 /jcm11247314

- Sigfrid L, Drake TM, Pauley E, et al. Long COVID in adults discharged from UK hospitals after COVID-19: a prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;8:100186. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100186

- Pollack B, von Saltza E, McCorkell L, et al. Female reproductive health impacts of long COVID and associated illnesses including ME/CFS, POTS, and connective tissue disorders: a literature review. Front Rehabil Sci. 2023;4:1122673. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1122673

- Stewart S, Newson L, Briggs TA, et al. Long COVID risk - a signal to address sex hormones and women’s health. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;11:100242. doi: 10.1016 /j.lanepe.2021.100242

- Li K, Chen G, Hou H, et al. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:260-267. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2020.09.020

- Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-tomoderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:210216. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x

- Sharp GC, Fraser A, Sawyer G, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the menstrual cycle: research gaps and opportunities. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:691-700. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab239

- Ding T, Wang T, Zhang J, et al. Analysis of ovarian injury associated with COVID-19 disease in reproductive-aged women in Wuhan, China: an observational study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:635255. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.635255

- Huang B, Cai Y, Li N, et al. Sex-based clinical and immunological differences in COVID-19. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:647. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06313-2

- Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113364. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Klein SL, Levin ER. Estradiol, progesterone, immunomodulation, and COVID-19 outcomes. Endocrinology. 2020;161:bqaa127. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqaa127

- The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:531-539. doi:10.1001 /jamainternmed.2014.8063

- Newson L, Lewis R, O’Hara M. Long COVID and menopause - the important role of hormones in long COVID must be considered. Maturitas. 2021;152:74. doi: 10.1016 /j.maturitas.2021.08.026

- di Filippo L, Frara S, Nannipieri F, et al. Low Vitamin D levels are associated with long COVID syndrome in COVID-19 survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:e1106-e1116. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad207

Continue to: Chronic fatigue syndrome...

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome: A large number of patients have “post-COVID conditions” affecting everyday function, including depression/anxiety, insomnia, and chronic fatigue (with a 3:1 female predominance)

Alexandra Kadl, MD

After 3 years battling acute COVID-19 infections, we encounter now a large number of patients with PASC— also known as “long COVID,” “COVID long-hauler syndrome,” and “post-COVID conditions”—a persistent multisystem syndrome that impacts everyday function.1 As of October 2023, there are more than 100 million COVID-19 survivors reported in the United States; 10% to 85% of COVID survivors2-4 may show lingering, life-altering symptoms after recovery. Common reported symptoms include fatigue, depression/ anxiety, insomnia, and brain fog/difficulty concentrating, which are particularly high in women who often had experienced only mild acute COVID-19 disease and were not even hospitalized. More recently, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) has been recognized as major component of PASC5 with a 3:1 female predominance.6 Up to 75% of patients with this diagnosis are not able to maintain their jobs and normal life, and up to 25% are so disabled that they are bedbound.6

Diagnosis

Although illnesses resembling CFS have been reported for more than 200 years,7 the diagnosis of CFS/ME remains difficult to make. There is a likely underreporting due to fear of being labeled as malingering when reaching out to health care providers, and there is a reporting bias toward higher socioeconomic groups due to better access to health care. The current criteria for the diagnosis of CFS/ME include the following 3 components8:

- substantial impairment in the ability to function for more than 6 months, accompanied by profound fatigue, not alleviated by rest

- post-exertional malaise (PEM; prolonged, disabling exacerbation of the patient’s baseline symptoms after exercise)

- non-refreshing sleep, PLUS either cognitive impairment or orthostatic intolerance.

Pathophysiology

Originally found to evolve in a small patient population with Epstein-Barr virus infection and Lyme disease, CFS/ME has moved to centerstage after the COVID-19 pandemic. While the diagnosis of COVID-19–related CFS/ME has advanced in the field, a clear mechanistic explanation of why it occurs is still missing. Certain risk factors have been identified for the development of CFS/ME, including female sex, reactivation of herpesviruses, and presence of connective tissue disorders; however, about one-third of patients with CFS/ME do not have identifiable risk factors.9,10 Persistence of viral particles11 and prolonged inflammatory states are speculated to affect the nervous system and mitochondrial function and metabolism. Interestingly, there is no correlation between severity of initial COVID-19 illness and the development of CFS/ME, similar to observations in non–COVID-19–related CFS/ME.

Proposed therapy

There is currently no proven therapy for CFS/ME. At this time, several immunomodulatory, antiviral, and neuromodulator drugs are being tested in clinical trial networks around the world.12 Usual physical therapy with near maximum intensity has been shown to exacerbate symptoms and often results in PEM, which is described as a “crash” or “full collapse” by patients. The time for recovery after such episodes can be several days.13

Instead, the focus should be on addressing “treatable” concomitant symptoms, such as sleep disorders, anxiety and depression, and chronic pain. Lifestyle changes, avoidance of triggers, and exercise without over exertion are currently recommended to avoid incapacitating PEM.

Gaps in knowledge

There is a large knowledge gap regarding the pathophysiology, prevention, and therapy for CFS/ME. Many health care practitioners are not familiar with the disease and have focused on measurable parameters of exercise limitations and fatigue, such as anemias and lung and cardiac impairments, thus treating CFS/ME as a form of deconditioning. Given the large number of patients who recovered from acute COVID-19 that are now disabled due to CFS/ME, a patient-centered research opportunity has arisen. Biomedical/mechanistic research is ongoing, and well-designed clinical trials evaluating pharmacologic intervention as well as tailored exercise programs are needed.

Conclusion

General practitioners and women’s health specialists need to be aware of CFS/ME, especially when managing patients with long COVID. They also need to know that typical physical therapy may worsen symptoms. Furthermore, clinicians should shy away from trial drugs with a theoretical benefit outside of a clinical trial. ●

- Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) has been recognized as a major component of PASC

- Typical physical therapy has been shown to exacerbate symptoms of CFS/ME

- Treatment should focus on addressing “treatable” concomitant symptoms, lifestyle changes, avoidance of triggers, and exercise without over exertion

References

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, et al. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102-e107. doi: 10.1016 /S1473-3099(21)00703-9

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, et al. Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1593-1607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022 -00846-2

- Pavli A, Theodoridou M, Maltezou HC. Post-COVID syndrome: incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch Med Res. 2021;52:575-581. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010

- Kedor C, Freitag H, Meyer-Arndt L, et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5104. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32507-6

- Bateman L, Bested AC, Bonilla HF, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: essentials of diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:28612878. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.004

- Wessely S. History of postviral fatigue syndrome. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:919-941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072521

- Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. National Academies Press; 2015. doi: 10.17226/19012

- Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

- Hanson MR. The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19:e1011523. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011523

- Scheibenbogen C, Bellmann-Strobl JT, Heindrich C, et al. Fighting post-COVID and ME/CFS—development of curative therapies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1194754. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1194754

- Stussman B, Williams A, Snow J, et al. Characterization of post-exertional malaise in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Neurol. 2020;11:1025. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01025

Long COVID (postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC) is an emerging syndrome that affects 50% to 70% of people who survive COVID-19 for up to 3 months or longer after acute disease.1 It is a multisystem condition that causes dysfunction of respiratory, cardiac, and nervous tissue, at least in part likely due to alterations in cellular energy metabolism and reduced oxygen supply to tissue.3 Patients who have had SARS-CoV-2 infection report persistent symptoms and signs that affect their quality of life. These may include neurocognitive, cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal symptoms; loss of taste and smell; and constitutional symptoms.2 There is no one test to determine if symptoms are due to COVID-19.3

Acute COVID-19 mortality risk factors include increasing age, chronic comorbidities, and male sex. However, long COVID risk factors are quite different. A meta-analysis and review of 20 articles that met inclusion criteria (n = 13,340 study participants), limited by pooling of crude estimates, found that risk factors were female sex and severity of acute disease.4 A second meta-analysis of 37 studies with 1 preprint found that female sex and comorbidities such as pulmonary disease, diabetes, and obesity were risk factors for long COVID.5 Qualitative analysis of single studies (n = 18 study participants) suggested that older adults can develop more long COVID symptoms than younger adults, but this association between advancing age and long COVID was not supported when data were pooled into a meta-analysis.3 However, both single studies (n = 16 study participants) and the meta-analysis (n = 7 study participants) did support female sex as a risk factor for long COVID, along with single studies suggesting increased risk with medical comorbidities for pulmonary disease, diabetes, and organ transplantation.

Perimenopause

Perimenopause: A temporary disruption to physiologic ovarian steroid hormone production following COVID could acutely exacerbate symptoms of perimenopause and menopause.

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, MSCP

The higher prevalence of long COVID in women younger than 50 years6 supports the overlap that studies have shown between symptoms of long COVID and perimenopause,7 as the median age of natural menopause is 51 years. Thus, health care providers need to differentiate between long COVID and other conditions, such as perimenopause, which share similar symptoms (FIGURE). Perimenopause might be diagnosed as long COVID, or the 2 might affect each other.

Symptoms of long COVID include fatigue, brain fog, and increased heart rate after recovering from COVID-19 and may continue or increase after an initial infection.8 Common symptoms of perimenopause and menopause, which also could be seen with long COVID, include typical menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, or disrupted sleep; changes in mood including dysthymia, depression, anxiety, or emotional lability; cognitive concerns such as brain fog or decreased concentration; and decreased stamina, fatigue, joint and muscle pains, or more frequent headaches. Therefore, women in their 40s or 50s with persistent symptoms after having COVID-19 without an alternative diagnosis, and who present with menstrual irregularity,9hot flashes, or night sweats, could be having an exacerbation of perimenopausal symptoms, or they could be experiencing a combination of long COVID and perimenopausal symptoms.

- Consider long COVID, versus perimenopause, or both, in women aged younger than 50 years

- Estradiol, which has been shown to alleviate perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms, also has been shown to have beneficial effects during acute COVID-19 infection

- Hormone therapy could improve symptoms of perimenopause and long COVID if some of the symptoms are due to changes in ovary function

Continue to: Potential pathophysiology...

Potential pathophysiology

Inflammation is likely to be critical in the pathogenesis of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or PASC. Individuals with long COVID have elevated inflammatory markers for several months.10 The chronic inflammation associated with long COVID could cause disturbances in the ovary and ovarian hormone production.2,10,11

During perimenopause, the ovary is more sensitive to illnesses such as COVID-19and to stress. The current theory is that COVID-19 affects the ovary with declines in ovarian reserve and ovarian function7 and with potential disruptions to the menstrual cycle, gonadal function, and ovarian sufficiency that lead to issues with menopause or fertility, as well as symptom exacerbation around menstruation.12 Another theory is that SARS-CoV-2 infection affects ovary hormone production, as there is an abundance of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptors on ovarian and endometrial tissue.11 Thus, it makes sense that long COVID could bring on symptoms of perimenopause or menopause more acutely or more severely or lengthen the duration of perimenopausal symptoms.

Perimenopause is the transitional period prior to menopause, when the ovaries gradually produce fewer hormones and is associated with erratic hormonal fluctuations. The length of this transitional period varies from 4 to 10 years. Ethnic variations in the duration of hot flashes have been found, noting that Black and Hispanic women have them for an average of 8 to 10 years (longer), White women for an average of 7 years, and Asian, Japanese, and Chinese women for an average of 5 to 6 years (shorter).17

What should health care providers ask?

Distinguishing perimenopause from long COVID. It is important to try to differentiate between perimenopause and long COVID, and it is possible to have both, with long COVID exacerbating the menopausal symptoms.7,8 Health care providers should be alert to consider perimenopause if women present with shorter or longer cycles (21-40 days), missed periods (particularly 60 days or 2 months), or worsening perimenopausal mood, migraines, insomnia, or hot flashes. Clinicians should actively enquire about all of these symptoms.

Moreover, if a perimenopausal woman reports acutely worsening symptoms after COVID-19, health care providers should address the perimenopausal symptoms and determine whether hormone therapy is appropriate and could improve their symptoms. Women do not need to wait until they go 1 year without a period to be treated with hormone therapy to improve perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. If women with long COVID have perimenopause or menopause symptoms, they should have access to evidence-based information and discuss menopausal hormone therapy if appropriate. Hormone therapy could improve both perimenopausal symptoms and the long COVID symptoms if some of the symptoms are due to changes in ovary function. Health care providers could consider progesterone or antidepressants during the second half of the cycle (luteal phase) or estrogen combined with progesterone for the entire cycle.18

For health care providers working in long COVID clinics, in addition to asking when symptoms started, what makes symptoms worse, the frequency of symptoms, and which activities are affected, ask about perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. If a woman has irregular periods, sleep disturbances, fatigue, or mood changes, consider that these could be related to long COVID, perimenopause, or both.8,18 Be able to offer treatment or refer patients to a women’s health specialist who can assess and offer treatment.

A role for vitamin D? A recent retrospective case-matched study found that 6 months after hospital discharge, patients with long COVID had lower levels of 25(OH) vitamin D with the most notable symptom being brain fog.19 Thus, there may be a role for vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy in those being discharged after hospitalization. Vitamin D levels and supplementation have not been otherwise evaluated to date.

Lifestyle strategies for women with perimenopause and long COVID

Lifestyle strategies should be encouraged for women during perimenopause and long COVID. This includes good nutrition (avoiding carbs and sweets, particularly before menses), getting at least 7 hours of sleep and using sleep hygiene (regular bedtimes, sleep regimen, no late screens), getting regular exercise 5 days per week, reducing stress, avoiding excess alcohol, and not smoking. All of these factors can help women and their ovarian function during this period of ovarian fluctuations.

The timing of menopause and COVID may coincide with midlife stressors, including relationship issues (separations or divorce), health issues for the individual or their partner, widowhood, parenting challenges (care of young children, struggles with adolescents, grown children returning home), being childless, concerns about aging parents and caregiving responsibilities, as well as midlife career, community, or education issues—all of which make both long COVID and perimenopause more challenging to navigate.

Need for research

There is a need for future research to understand the epidemiologic basis and underlying biological mechanisms of sex differences seen in women with long COVID. Studying the effects of COVID-19 on ovarian function could lead to a better understanding of perimenopause, what causes ovarian failure to speed up, and possibly ways to slow it down8 since there are health risks of early menopause.16

References

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D, GómezMayordomo V, et al. Defining post-COVID symptoms (postacute COVID, long COVID, persistent post-COVID): an integrative classification. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2621. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052621

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601-615. doi: 10.1038/s41591 -021-01283-z

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

- Maglietta G, Diodati F, Puntoni M, et al. Prognostic factors for post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1541. doi: 10.3390 /jcm11061541

- Notarte KI, de Oliveira MHS, Peligro PJ, et al. Age, sex and previous comorbidities as risk factors not associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection for long COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:7314. doi: 10.3390 /jcm11247314

- Sigfrid L, Drake TM, Pauley E, et al. Long COVID in adults discharged from UK hospitals after COVID-19: a prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;8:100186. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100186

- Pollack B, von Saltza E, McCorkell L, et al. Female reproductive health impacts of long COVID and associated illnesses including ME/CFS, POTS, and connective tissue disorders: a literature review. Front Rehabil Sci. 2023;4:1122673. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1122673

- Stewart S, Newson L, Briggs TA, et al. Long COVID risk - a signal to address sex hormones and women’s health. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;11:100242. doi: 10.1016 /j.lanepe.2021.100242

- Li K, Chen G, Hou H, et al. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:260-267. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2020.09.020

- Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-tomoderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:210216. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x

- Sharp GC, Fraser A, Sawyer G, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the menstrual cycle: research gaps and opportunities. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:691-700. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab239

- Ding T, Wang T, Zhang J, et al. Analysis of ovarian injury associated with COVID-19 disease in reproductive-aged women in Wuhan, China: an observational study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:635255. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.635255

- Huang B, Cai Y, Li N, et al. Sex-based clinical and immunological differences in COVID-19. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:647. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06313-2

- Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113364. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Klein SL, Levin ER. Estradiol, progesterone, immunomodulation, and COVID-19 outcomes. Endocrinology. 2020;161:bqaa127. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqaa127

- The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:531-539. doi:10.1001 /jamainternmed.2014.8063

- Newson L, Lewis R, O’Hara M. Long COVID and menopause - the important role of hormones in long COVID must be considered. Maturitas. 2021;152:74. doi: 10.1016 /j.maturitas.2021.08.026

- di Filippo L, Frara S, Nannipieri F, et al. Low Vitamin D levels are associated with long COVID syndrome in COVID-19 survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:e1106-e1116. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad207

Continue to: Chronic fatigue syndrome...

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome: A large number of patients have “post-COVID conditions” affecting everyday function, including depression/anxiety, insomnia, and chronic fatigue (with a 3:1 female predominance)

Alexandra Kadl, MD

After 3 years battling acute COVID-19 infections, we encounter now a large number of patients with PASC— also known as “long COVID,” “COVID long-hauler syndrome,” and “post-COVID conditions”—a persistent multisystem syndrome that impacts everyday function.1 As of October 2023, there are more than 100 million COVID-19 survivors reported in the United States; 10% to 85% of COVID survivors2-4 may show lingering, life-altering symptoms after recovery. Common reported symptoms include fatigue, depression/ anxiety, insomnia, and brain fog/difficulty concentrating, which are particularly high in women who often had experienced only mild acute COVID-19 disease and were not even hospitalized. More recently, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) has been recognized as major component of PASC5 with a 3:1 female predominance.6 Up to 75% of patients with this diagnosis are not able to maintain their jobs and normal life, and up to 25% are so disabled that they are bedbound.6

Diagnosis

Although illnesses resembling CFS have been reported for more than 200 years,7 the diagnosis of CFS/ME remains difficult to make. There is a likely underreporting due to fear of being labeled as malingering when reaching out to health care providers, and there is a reporting bias toward higher socioeconomic groups due to better access to health care. The current criteria for the diagnosis of CFS/ME include the following 3 components8:

- substantial impairment in the ability to function for more than 6 months, accompanied by profound fatigue, not alleviated by rest

- post-exertional malaise (PEM; prolonged, disabling exacerbation of the patient’s baseline symptoms after exercise)

- non-refreshing sleep, PLUS either cognitive impairment or orthostatic intolerance.

Pathophysiology

Originally found to evolve in a small patient population with Epstein-Barr virus infection and Lyme disease, CFS/ME has moved to centerstage after the COVID-19 pandemic. While the diagnosis of COVID-19–related CFS/ME has advanced in the field, a clear mechanistic explanation of why it occurs is still missing. Certain risk factors have been identified for the development of CFS/ME, including female sex, reactivation of herpesviruses, and presence of connective tissue disorders; however, about one-third of patients with CFS/ME do not have identifiable risk factors.9,10 Persistence of viral particles11 and prolonged inflammatory states are speculated to affect the nervous system and mitochondrial function and metabolism. Interestingly, there is no correlation between severity of initial COVID-19 illness and the development of CFS/ME, similar to observations in non–COVID-19–related CFS/ME.

Proposed therapy

There is currently no proven therapy for CFS/ME. At this time, several immunomodulatory, antiviral, and neuromodulator drugs are being tested in clinical trial networks around the world.12 Usual physical therapy with near maximum intensity has been shown to exacerbate symptoms and often results in PEM, which is described as a “crash” or “full collapse” by patients. The time for recovery after such episodes can be several days.13

Instead, the focus should be on addressing “treatable” concomitant symptoms, such as sleep disorders, anxiety and depression, and chronic pain. Lifestyle changes, avoidance of triggers, and exercise without over exertion are currently recommended to avoid incapacitating PEM.

Gaps in knowledge

There is a large knowledge gap regarding the pathophysiology, prevention, and therapy for CFS/ME. Many health care practitioners are not familiar with the disease and have focused on measurable parameters of exercise limitations and fatigue, such as anemias and lung and cardiac impairments, thus treating CFS/ME as a form of deconditioning. Given the large number of patients who recovered from acute COVID-19 that are now disabled due to CFS/ME, a patient-centered research opportunity has arisen. Biomedical/mechanistic research is ongoing, and well-designed clinical trials evaluating pharmacologic intervention as well as tailored exercise programs are needed.

Conclusion

General practitioners and women’s health specialists need to be aware of CFS/ME, especially when managing patients with long COVID. They also need to know that typical physical therapy may worsen symptoms. Furthermore, clinicians should shy away from trial drugs with a theoretical benefit outside of a clinical trial. ●

- Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) has been recognized as a major component of PASC

- Typical physical therapy has been shown to exacerbate symptoms of CFS/ME

- Treatment should focus on addressing “treatable” concomitant symptoms, lifestyle changes, avoidance of triggers, and exercise without over exertion

References

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, et al. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102-e107. doi: 10.1016 /S1473-3099(21)00703-9

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, et al. Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1593-1607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022 -00846-2

- Pavli A, Theodoridou M, Maltezou HC. Post-COVID syndrome: incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch Med Res. 2021;52:575-581. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010

- Kedor C, Freitag H, Meyer-Arndt L, et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5104. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32507-6

- Bateman L, Bested AC, Bonilla HF, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: essentials of diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:28612878. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.004

- Wessely S. History of postviral fatigue syndrome. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:919-941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072521

- Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. National Academies Press; 2015. doi: 10.17226/19012

- Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

- Hanson MR. The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19:e1011523. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011523

- Scheibenbogen C, Bellmann-Strobl JT, Heindrich C, et al. Fighting post-COVID and ME/CFS—development of curative therapies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1194754. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1194754

- Stussman B, Williams A, Snow J, et al. Characterization of post-exertional malaise in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Neurol. 2020;11:1025. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01025

Time to rethink endometrial ablation: A gyn oncology perspective on the sequelae of an overused procedure

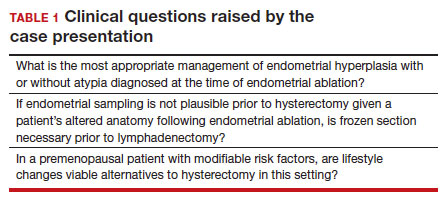

CASE New patient presents with a history of endometrial hyperplasia

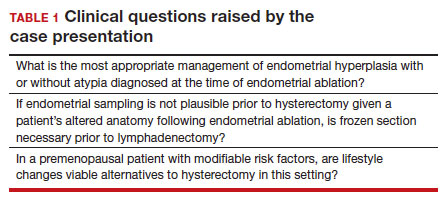

A 51-year-old patient (G2P2002) presents to a new gynecologist’s office after moving from a different state. In her medical history, the gynecologist notes that 5 years ago she underwent dilation and curettage and endometrial ablation procedures for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Ultrasonography performed prior to those procedures showed a slightly enlarged uterus, a simple left ovarian cyst, and a non ̶ visualized right ovary. The patient had declined a 2-step procedure due to concerns with anesthesia, and surgical pathology at the time of ablation revealed hyperplasia without atypia. The patient’s medical history was otherwise notable for prediabetes (recent hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] measurement, 6.0%) and obesity (body mass index, 43 kg/m2). Pertinent family history included her mother’s diagnosis of endometrial cancer at age 36. Given the patient’s diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, she was referred to gynecologic oncology, but she ultimately declined hysterectomy, stating that she was happy with the resolution of her abnormal bleeding. At the time of her initial gynecologic oncology consultation, the consultant suggested lifestyle changes to combat prediabetes and obesity to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, as future signs of cancer, namely bleeding, may be masked by the endometrial ablation. The patient was prescribed metformin given these medical comorbidities.

At today’s appointment, the patient notes continued resolution of bleeding since the procedure. She does, however, note a 6-month history of vasomotor symptoms and one episode of spotting 3 months ago. Three years ago she was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and her current HbA1c is 6.9%. She has gained 10 lb since being diagnosed with endometrial cancer 5 years ago, and she has continued to take metformin.

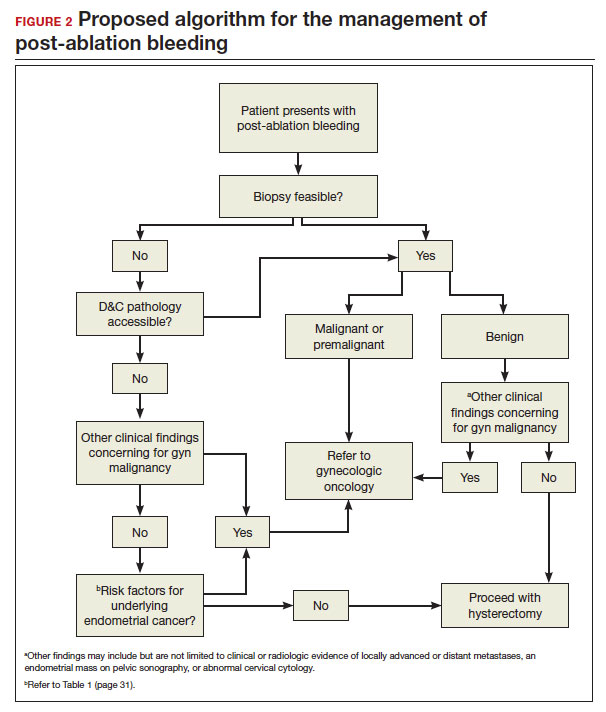

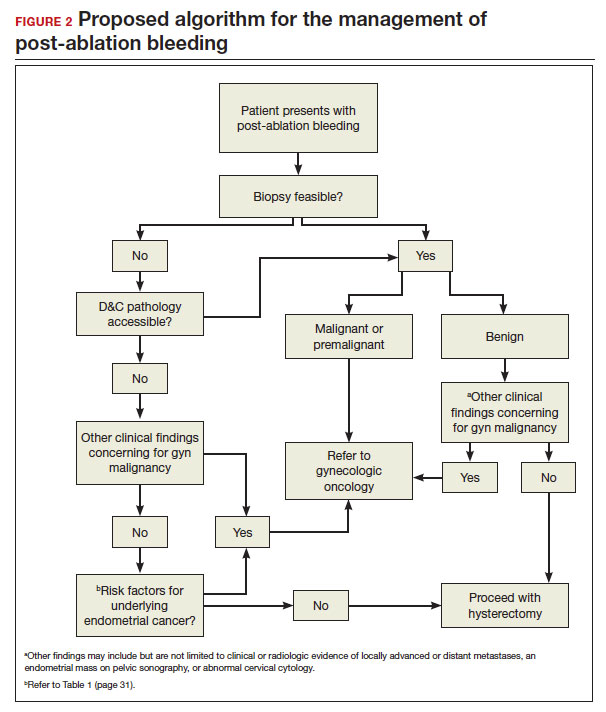

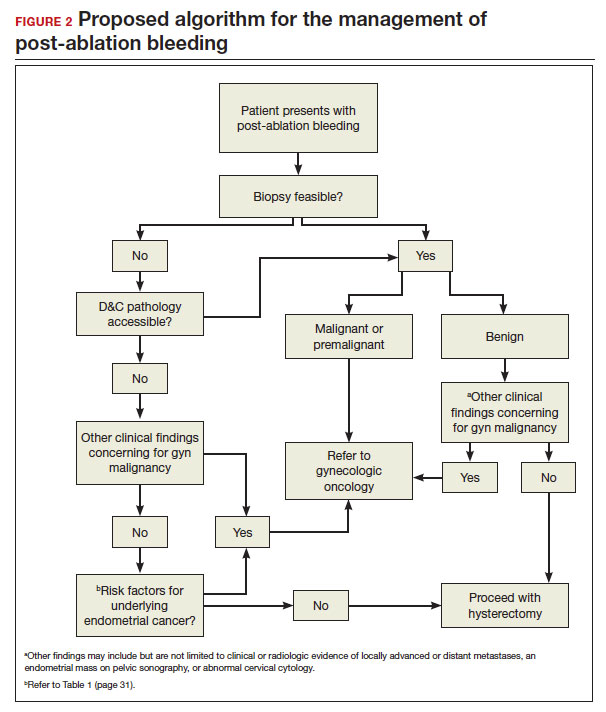

An in-office endometrial biopsy is unsuccessful due to cervical stenosis. The treating gynecologist orders a transvaginal ultrasound, which reveals a small left ovarian cyst and a thickened endometrium (measuring 10 mm). Concerned that these findings could represent endometrial cancer, the gynecologist refers the patient to gynecologic oncology for further evaluation.

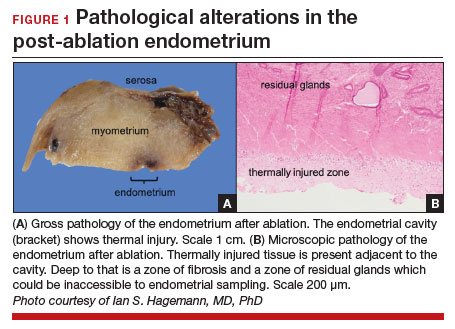

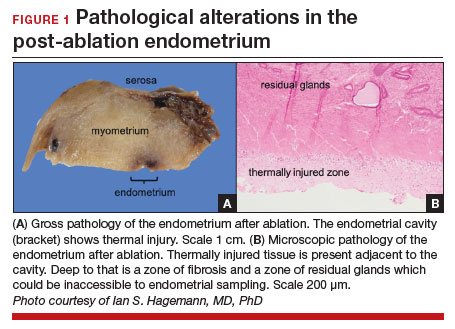

Sequelae and complications following endometrial ablation are often managed by a gynecologic oncologist. Indeed, a 2018 poll of Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) members revealed that 93.8% of respondents had received such a referral, and almost 20% of respondents were managing more than 20 patients with post-ablation complications in their practices.1 These complications, including hematometra, post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome, other pain syndromes associated with retrograde menstruation, and thickened endometrium with scarring leading to an inability to sample the endometrium to investigate post-ablation bleeding are symptoms and findings that often lead to further surgery, including hysterectomy.2 General gynecologists faced with these complications may refer patients to gynecologic oncology given an inability to sample the post-ablation endometrium or anticipated difficulties with hysterectomy. A recent meta-analysis revealed a 12.4% hysterectomy rate 5 years after endometrial ablation. Among these patients, the incidence of endometrial cancer ranged from 0% to 1.6%.3

In 2023, endometrial cancer incidence continues to increase, as does the incidence of obesity in women of all ages. Endometrial cancer mortality rates are also increasing, and these trends disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women.4 As providers and advocates work to narrow these disparities, gynecologic oncologists are simultaneously noting increased referrals for very likely benign conditions.5 Patients referred for post-ablation bleeding are a subset of these, as most patients who undergo endometrial ablation will not develop cancer. Considering the potential bottlenecks created en route to a gynecologic oncology evaluation, it seems prudent to minimize practices, like endometrial ablation, that may directly or indirectly prevent timely referral of patients with cancer to a gynecologic oncologist.

In this review we focus on the current use of endometrial ablation, associated complications, the incidence of treatment failure, and patient selection. Considering these issues in the context of the current endometrial cancer landscape, we posit best practices aimed at optimizing patient outcomes, and empowering general gynecologists to practice cancer prevention and to triage their surgical patients.

- Before performing endometrial ablation, consider whether alternatives such as hysterectomy or insertion of a progestin-containing IUD would be appropriate.

- Clinical management of patients with abnormal bleeding with indications for endometrial ablation should be guidelinedriven.

- Post-ablation bleeding or pain does not inherently require referral to oncology.

- General gynecologists can perform hysterectomy in this setting if appropriate.

- Patients with endometrial hyperplasia at endometrial ablation should be promptly offered hysterectomy. If atypia is not present, this hysterectomy, too, can be performed by a general gynecologist if appropriate, as the chance for malignancy is minimal.

Continue to: Current use of endometrial ablation in the US...

Current use of endometrial ablation in the US

In 2015, more than 500,000 endometrial ablations were performed in the United States.Given the ability to perform in-office ablation, this number is growing and potentially underestimated each year.6 In 2022, the global endometrial ablation market was valued at $3.4 billion, a figure projected to double in 10 years.7 The procedure has evolved as different devices and approaches have developed, offering patients different means to manage bleeding without hysterectomy. The minimally invasive procedure, performed in premenopausal patients with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) due to benign causes who have completed childbearing, has been associated with faster recovery times and fewer short-term complications compared with more invasive surgery.8 There are several non-resectoscope ablative devices approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and each work to destroy the endometrial lining via thermal or cryoablation. Endometrial ablation can be performed in premenopausal patients with HMB due to benign causes who have completed childbearing.

Recently, promotional literature has begun to report on so-called overuse of hysterectomy, despite decreasing overall hysterectomy rates. This reporting proposes and applies “appropriateness criteria,” accounting for the rate of preoperative counseling regarding alternatives to hysterectomy, as well as the rate of “unsupportive” final pathology.9 The adoption of endometrial ablation and increasing market value of such vendors suggest that this campaign is having its desired effect. From the oncology perspective, we are concerned the pendulum could swing too far away from hysterectomy, a procedure that definitively cures abnormal uterine bleeding, toward endometrial ablation without explicit acknowledgement of the trade-offs involved.

Endometrial ablation complications: Late-onset procedure failure

A number of post-ablation syndromes may present at least 1 month following the procedure. Collectively known as late-onset endometrial ablation failure (LOEAF), these syndromes are characterized by recurrent vaginal bleeding, and/or new cyclic pelvic pain.10 It is difficult to measure the true incidence of LOEAF. Thomassee and colleagues examined a Canadian retrospective cohort of 437 patients who underwent endometrial ablation; 20.8% reported post-ablation pelvic pain after a median 301 days.11 The subsequent need for surgical intervention, often hysterectomy, is a surrogate for LOEAF.

It should be noted that LOEAF is distinct from post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS), which describes cornual menstrual bleeding impeded by the ligated proximal fallopian tube.12 Increased awareness of PATSS, along with the discontinuation of Essure (a permanent hysteroscopic sterilization device) in 2018, has led some surgeons to advocate for concomitant salpingectomy at the time of endometrial ablation.13 The role of opportunistic salpingectomy in primary prevention of epithelial ovarian cancer is well described, and while we strongly support this practice at the time of endometrial ablation, we do not feel that it effectively prevents LOEAF.14

The post-ablation inability to adequately sample the endometrium is also considered a LOEAF. A prospective study of 57 women who underwent endometrial ablation assessed post-ablation sampling feasibility via transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), and in-office endometrial biopsies. In 23% of the cohort, endometrial sampling failed, and the authors noted decreased reliability of pathologic assessment.15 One systematic review, in which authors examined the incidence of endometrial cancer following endometrial ablation, characterized 38 cases of endometrial cancer and reported a post-ablation endometrial sampling success rate of 89%. This figure was based on a self-selected sample of 18 patients; cases in which endometrial sampling was thought to be impossible were excluded. The study also had a 30% missing data rate and several other biases.16

In the previously mentioned poll of SGO members,1 84% of the surveyed gynecologic oncologists managing post-ablation patients reported that endometrial sampling following endometrial ablation was “moderately” or “extremely” difficult. More than half of the survey respondents believed that hysterectomy was required for accurate diagnosis.1 While we acknowledge the likely sampling bias affecting the survey results, we are not comforted by any data that minimizes this diagnostic challenge.

Appropriate patient selection and contraindications

The ideal candidate for endometrial ablation is a premenopausal patient with HMB who does not desire future fertility. According to the FDA, absolute contraindications include pregnancy or desired fertility, prior ablation, current IUD in place, inadequate preoperative endometrial assessment, known or suspected malignancy, active infection, or unfavorable anatomy.17

What about patients who may be at increased risk for endometrial cancer?

There is a paucity of data regarding the safety of endometrial ablation in patients at increased risk for developing endometrial cancer in the future. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2007 practice bulletin on endometrial ablation (no longer accessible online) alludes to this concern and other contraindications,18 but there are no established guidelines. Currently, no ACOG practice bulletin or committee opinion lists relative contraindications to endometrial ablation, long-term complications (except risks associated with future pregnancy), or risk of subsequent hysterectomy. The risk that “it may be harder to detect endometrial cancer after ablation” is noted on ACOG’s web page dedicated to frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding abnormal uterine bleeding.19 It is not mentioned on their web page dedicated to the FAQs regarding endometrial ablation.20

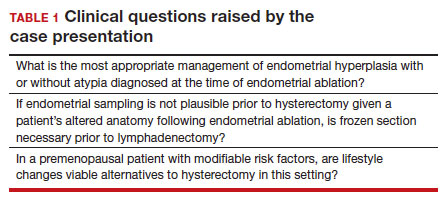

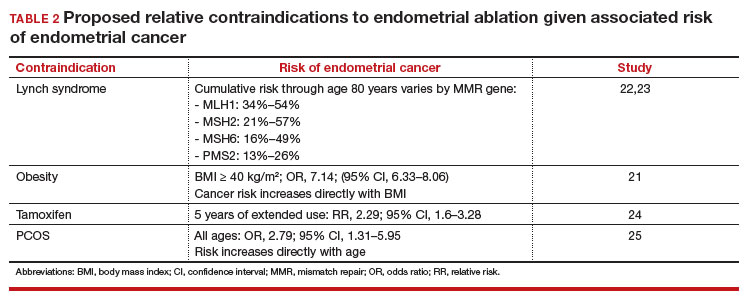

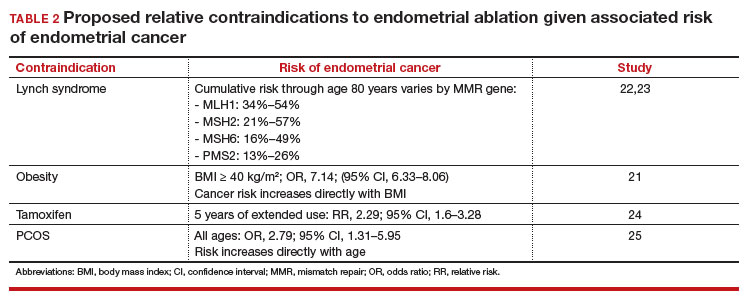

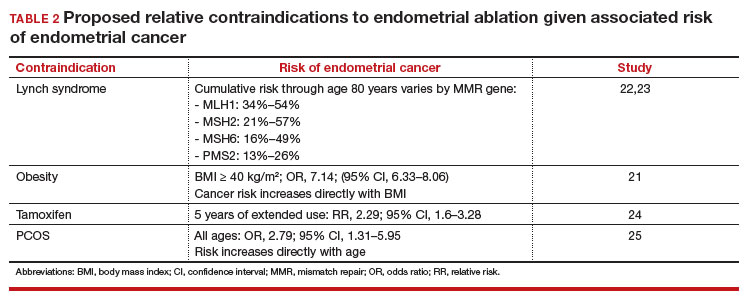

In the absence of high-quality published data on established contraindications for endometrial ablation, we advocate for the increased awareness of possible relative contraindications—namely well-established risk factors for endometrial cancer (TABLE 1).For example, in a pooled analysis of 24 epidemiologic studies, authors found that the odds of developing endometrial cancer was 7 times higher among patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2, compared with controls (odds ratio [OR], 7.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.33–8.06).21 Additionally, patients with Lynch syndrome, a history of extended tamoxifen use, or those with a history of chronic anovulation or polycystic ovary syndrome are at increased risk for endometrial cancer.22-24 If the presence of one or more of these factors does not dissuade general gynecologists from performing an endometrial ablation (even armed with a negative preoperative endometrial biopsy), we feel they should at least prompt thoughtful guideline-driven pause.

Continue to: Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option...

Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option

The annual number of hysterectomies performed by general gynecologists has declined over time. One study by Cadish and colleagues revealed that recent residency graduates performed only 3 to 4 annually.25 These numbers partly reflect the decreasing number of hysterectomies performed during residency training. Furthermore, other factors—including the increasing rate of placenta accreta spectrum, the focus on risk stratification of adnexal masses via the ovarian-adnexal reporting and data classification system (O-RADs), and the emphasis on minimally invasive approaches often acquired in subspecialty training—have likely contributed to referral patterns to such specialists as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and gynecologic oncologists.26 This trend is self-actualizing, as quality metrics funnel patients to high-volume surgeons, and general gynecologists risk losing hysterectomy privileges.

These factors lend themselves to a growing emphasis on endometrial ablation. Endometrial ablations can be performed in several settings, including in the hospital, in outpatient clinics, and more and more commonly, in ambulatory surgery centers. This increased access to endometrial ablation in the ambulatory surgery setting has corresponded with an annual endometrial ablation market value growth rate of 5% to 7%.27 These rates are likely compounded by payer reimbursement policies that promote endometrial ablation and other alternatives to hysterectomy that are cost savings in the short term.28 While the actual payer models are unavailable to review, they may not consider the costs of LOEAFs, including subsequent hysterectomy up to 5 years after initial ablation procedures. Provocatively, they almost certainly do not consider the costs of delayed care of patients with endometrial cancer vying for gynecologic oncology appointment slots occupied by post-ablation patients.

We urge providers, patients, and advocates to question who benefits from the uptake of ablation procedures: Patients? Payors? Providers? And how will the field of gynecology fare if hysterectomy skills and privileges are supplanted by ablation?

Post-ablation bleeding: Management by the gyn oncologist