User login

Pediatric, adolescent migraine treatment and prevention guidelines are updated

Two new guidelines on the treatment and prevention of migraines in children and adolescents have been released by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.

This update to the previous guidelines released by the American Academy of Neurology in 2004 reflects the expansion in pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches during the last 15 years, Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, director of the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

“There has also been an increase in the number of randomized controlled studies, which have allowed for a more robust statement on acute and preventive treatments to be made,” said Dr. Hershey, who is also a senior author for both guidelines.

The two reports focused on separate issues: One guideline outlined the options for treatment of acute migraine, and the second guideline summarized the available studies on the effectiveness of preventive medications for migraine in children and adolescents.

The guidelines recommend a physical examination and history to establish a specific headache diagnosis and afford a treatment that provides fast and complete pain relief. Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient realizes an attack is occurring. Patients with signs of secondary headache should be evaluated by a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Studies support the use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for pain relief in cases of acute migraine, but only some triptans (such as almotriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan/naproxen, and zolmitriptan nasal spray) are approved for use in adolescents. Specifically, sumatriptan/naproxen was shown to be effective when compared with placebo in studies with adolescents, whose headache symptoms resolved within 2 hours.

It may be necessary to try more than one triptan, the guidelines noted, because patients respond differently to medications. A failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily mean that treatment with another triptan will be unsuccessful.

The guidelines also focused on patient and family education to improve medication safety and adherence. Lifestyle modification, avoidance of migraine triggers, creating good sleep habits, and staying hydrated can help reduce migraines. While no medications improved associated symptoms of migraines such as nausea or vomiting, triptans did show a benefit in reducing phonophobia and photophobia.

Evidence for pharmacologic prevention of migraines in children and adolescents is limited, according to the guidelines. In the 15 studies included in a literature review, there was not sufficient evidence to show preventive treatments, such as divalproex, onabotulinumtoxinA, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and flunarizine, were more effective than placebo at reducing the frequency of headaches. There was some evidence to show propranolol in children and topiramate and cinnarizine in children and adolescents can reduce headache frequency. Children and adolescents who received cognitive-behavioral therapy together with amitriptyline were more likely to have reduced frequency of headaches than were those who received amitriptyline with patient education.

“The consensus conclusion was that a multidisciplinary approach that combines acute treatments, preventive treatments, and healthy habits is likely to have the best outcomes,” said Dr. Hershey.

Dr. Hershey acknowledged the many gaps between what is clinically observed and what the studies in the guidelines demonstrated.

“One of the biggest questions is how to minimize the expectation response in the controlled studies,” he said. “Additionally, we are moving toward a better recognition of the mechanism by which the various treatments work in a genetic-based disease that is polygenic in nature” with up to 38 different gene polymorphisms identified to date.

The guidelines also do not address newer treatments, such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) antibodies, CGRP antagonists, serotonin antagonists, and devices because there are as yet no studies of their effectiveness in children and adolescents.

“They have been studied in adults, so will be prone to the expectation response; but given the large number of diverse therapies, one can hope that many of the gaps can be filled,” said Dr. Hershey.

The American Academy of Neurology provided funding for development of the guidelines and reimbursed authors who served as subcommittee members for travel expenses and in-person meetings. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, grants, honorariums, consultancies, and publishing royalties for pharmaceutical companies and other organizations.

SOURCES: Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105.

Two new guidelines on the treatment and prevention of migraines in children and adolescents have been released by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.

This update to the previous guidelines released by the American Academy of Neurology in 2004 reflects the expansion in pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches during the last 15 years, Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, director of the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

“There has also been an increase in the number of randomized controlled studies, which have allowed for a more robust statement on acute and preventive treatments to be made,” said Dr. Hershey, who is also a senior author for both guidelines.

The two reports focused on separate issues: One guideline outlined the options for treatment of acute migraine, and the second guideline summarized the available studies on the effectiveness of preventive medications for migraine in children and adolescents.

The guidelines recommend a physical examination and history to establish a specific headache diagnosis and afford a treatment that provides fast and complete pain relief. Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient realizes an attack is occurring. Patients with signs of secondary headache should be evaluated by a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Studies support the use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for pain relief in cases of acute migraine, but only some triptans (such as almotriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan/naproxen, and zolmitriptan nasal spray) are approved for use in adolescents. Specifically, sumatriptan/naproxen was shown to be effective when compared with placebo in studies with adolescents, whose headache symptoms resolved within 2 hours.

It may be necessary to try more than one triptan, the guidelines noted, because patients respond differently to medications. A failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily mean that treatment with another triptan will be unsuccessful.

The guidelines also focused on patient and family education to improve medication safety and adherence. Lifestyle modification, avoidance of migraine triggers, creating good sleep habits, and staying hydrated can help reduce migraines. While no medications improved associated symptoms of migraines such as nausea or vomiting, triptans did show a benefit in reducing phonophobia and photophobia.

Evidence for pharmacologic prevention of migraines in children and adolescents is limited, according to the guidelines. In the 15 studies included in a literature review, there was not sufficient evidence to show preventive treatments, such as divalproex, onabotulinumtoxinA, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and flunarizine, were more effective than placebo at reducing the frequency of headaches. There was some evidence to show propranolol in children and topiramate and cinnarizine in children and adolescents can reduce headache frequency. Children and adolescents who received cognitive-behavioral therapy together with amitriptyline were more likely to have reduced frequency of headaches than were those who received amitriptyline with patient education.

“The consensus conclusion was that a multidisciplinary approach that combines acute treatments, preventive treatments, and healthy habits is likely to have the best outcomes,” said Dr. Hershey.

Dr. Hershey acknowledged the many gaps between what is clinically observed and what the studies in the guidelines demonstrated.

“One of the biggest questions is how to minimize the expectation response in the controlled studies,” he said. “Additionally, we are moving toward a better recognition of the mechanism by which the various treatments work in a genetic-based disease that is polygenic in nature” with up to 38 different gene polymorphisms identified to date.

The guidelines also do not address newer treatments, such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) antibodies, CGRP antagonists, serotonin antagonists, and devices because there are as yet no studies of their effectiveness in children and adolescents.

“They have been studied in adults, so will be prone to the expectation response; but given the large number of diverse therapies, one can hope that many of the gaps can be filled,” said Dr. Hershey.

The American Academy of Neurology provided funding for development of the guidelines and reimbursed authors who served as subcommittee members for travel expenses and in-person meetings. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, grants, honorariums, consultancies, and publishing royalties for pharmaceutical companies and other organizations.

SOURCES: Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105.

Two new guidelines on the treatment and prevention of migraines in children and adolescents have been released by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.

This update to the previous guidelines released by the American Academy of Neurology in 2004 reflects the expansion in pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches during the last 15 years, Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, director of the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

“There has also been an increase in the number of randomized controlled studies, which have allowed for a more robust statement on acute and preventive treatments to be made,” said Dr. Hershey, who is also a senior author for both guidelines.

The two reports focused on separate issues: One guideline outlined the options for treatment of acute migraine, and the second guideline summarized the available studies on the effectiveness of preventive medications for migraine in children and adolescents.

The guidelines recommend a physical examination and history to establish a specific headache diagnosis and afford a treatment that provides fast and complete pain relief. Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient realizes an attack is occurring. Patients with signs of secondary headache should be evaluated by a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Studies support the use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for pain relief in cases of acute migraine, but only some triptans (such as almotriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan/naproxen, and zolmitriptan nasal spray) are approved for use in adolescents. Specifically, sumatriptan/naproxen was shown to be effective when compared with placebo in studies with adolescents, whose headache symptoms resolved within 2 hours.

It may be necessary to try more than one triptan, the guidelines noted, because patients respond differently to medications. A failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily mean that treatment with another triptan will be unsuccessful.

The guidelines also focused on patient and family education to improve medication safety and adherence. Lifestyle modification, avoidance of migraine triggers, creating good sleep habits, and staying hydrated can help reduce migraines. While no medications improved associated symptoms of migraines such as nausea or vomiting, triptans did show a benefit in reducing phonophobia and photophobia.

Evidence for pharmacologic prevention of migraines in children and adolescents is limited, according to the guidelines. In the 15 studies included in a literature review, there was not sufficient evidence to show preventive treatments, such as divalproex, onabotulinumtoxinA, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and flunarizine, were more effective than placebo at reducing the frequency of headaches. There was some evidence to show propranolol in children and topiramate and cinnarizine in children and adolescents can reduce headache frequency. Children and adolescents who received cognitive-behavioral therapy together with amitriptyline were more likely to have reduced frequency of headaches than were those who received amitriptyline with patient education.

“The consensus conclusion was that a multidisciplinary approach that combines acute treatments, preventive treatments, and healthy habits is likely to have the best outcomes,” said Dr. Hershey.

Dr. Hershey acknowledged the many gaps between what is clinically observed and what the studies in the guidelines demonstrated.

“One of the biggest questions is how to minimize the expectation response in the controlled studies,” he said. “Additionally, we are moving toward a better recognition of the mechanism by which the various treatments work in a genetic-based disease that is polygenic in nature” with up to 38 different gene polymorphisms identified to date.

The guidelines also do not address newer treatments, such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) antibodies, CGRP antagonists, serotonin antagonists, and devices because there are as yet no studies of their effectiveness in children and adolescents.

“They have been studied in adults, so will be prone to the expectation response; but given the large number of diverse therapies, one can hope that many of the gaps can be filled,” said Dr. Hershey.

The American Academy of Neurology provided funding for development of the guidelines and reimbursed authors who served as subcommittee members for travel expenses and in-person meetings. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, grants, honorariums, consultancies, and publishing royalties for pharmaceutical companies and other organizations.

SOURCES: Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Fatal Drug-Resistant Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus in a 56-Year-Old Immunosuppressed Man (FULL)

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

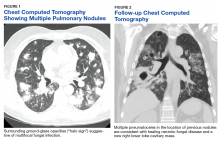

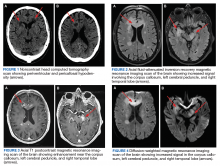

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

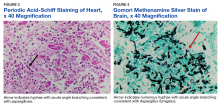

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

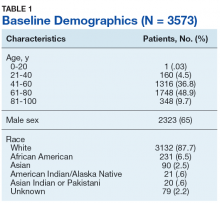

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

Interview with Andrew Pachner, MD, about the molecular processes of multiple sclerosis

Andrew R. Pachner, MD is the Murray B. Bornstein professor of neurology at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and director of the Multiple Sclerosis Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. We spoke to Dr. Pachner about his research into the molecular processes of multiple sclerosis (MS) and the potential impact on patient management.

What do we know about the molecular processes behind relapsing-remitting and progressive MS?

DR. PACHNER: The progress--in terms of molecules--has not been rapid in the field of MS. The only molecular biomarker we use in practice is oligoclonal bands or other measures of immunoglobulin production in the nervous system, and that biomarker was described in 1942. So, it has been a long time since we have seen a relevant molecule that we can use clinically.

But there has been a lot of progress in the general field of neuroinflammation. MS is one of a large number of diseases that results in neuroinflammation and demyelination.

One thing we have learned over time is that there are many different subtypes of MS. They probably have some shared molecular processes, but they also are likely to have divergent molecular processes.

Over the past 5 to 10 years, researchers have been interested in trying to dissect some of the molecular aspects of MS to identify biomarkers that can, in turn, differentiate subtypes of MS. This will help to identify different ways of treating MS that are optimal for individual patients. It is clear that each patient is quite different and unlikely to be standardized in the way they respond to treatment.

The degree to which relapsing-remitting and progressive MS are differentiated on the molecular level is dependent on how much influence there is of the immune system in the periphery. When MS first starts in a patient, the brain has either no or a very primitive immune system, and then over time it changes, and it becomes much more immune-oriented and populated by immune cells and molecules. So, there’s a trend over time of the central nervous system becoming increasingly populated by immune cells and able to make immune molecules.

What has your recent research on murine models representing these disease patterns shown?

DR. PACHNER: Even though in humans there is a continuum from relapsing remitting to progressive, it is not like they are completely separate. Frequently in the middle of relapsing-remitting disease there is some progression over time.

In mouse models, we like things to be very clear and separate. We try to make things as simple as possible because of the complexity of the nervous and immune systems.

The simple model for the relapsing-remitting disease is experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the most commonly studied model of neuroinflammation.

For the progressive form of MS, we use the Theiler’s virus model, which is a type of virus called the picornavirus that is injected into the brain of mice resulting in a slowly progressive, chronic viral infection that looks very much like progressive MS.

In EAE, the disease is induced by presenting an antigen to the peripheral immune system, allowing cells from the peripheral immune system to enter into the central nervous system. It is a manifestation of inflammation and the immune response is in the periphery. In the Theiler’s model, it is a localized process within the central nervous system because the virus is injected directly into the brain.

We found that in EAE the pattern is very much dominated by what happens in the periphery and the injury is very transient. There are cells that enter the nervous system that cause inflammation and damage, but there are also processes that downregulate those cells and processes and eventually the animal improves--similar to an MS attack.

By contrast, in the Theiler’s model there is progressive injury that is dominated by two molecular processes in the central nervous system that we do not see in relapsing-remitting MS or in EAE, and that is the activation of Type 1 interferons and also a very pronounced immunoglobulin production along with all the molecules that help support plasma cells making immunoglobulin.

These are two different animal models that provide us insight into how the central nervous system can be injured in the course of neuroinflammation and they look to be very different in how they manifest themselves, both in the periphery and in the central nervous system.

How may these new findings impact the future management and treatment of MS?

DR. PACHNER: When I see a patient with MS, I tell them that we absolutely need to focus on your own disease and how it responds, rather than taking too much guidance from MS as a whole. Because each patient with MS is different.

One of the things that we have tried to do is to identify molecular markers that might help us in management and treatment. As an example, we have learned that some patients who present with their first episode of MS do very poorly. These patients have many more attacks and/or have very aggressive progression in terms of their disability so that they potentially could be in a wheelchair within a few years. Other patients have what we call a benign variant MS. These patients may have an initial episode that is not that different than the other patient, but this type of patient may not have anything else for the rest of their life.

We would like to have some differentiation of those two types of patients. In the first example you can try to be very aggressive and minimize the neuroinflammation with powerful immune-suppressing drugs that have a high risk of causing side effects, such as cancer or opportunistic infections, but on the other hand may have a high benefit in preventing future inflammatory events and progressive injury. But that would not be the correct treatment choice for the second patient example.

It would be nice to tailor treatment to a predictive biomarker. That is something we have been working very hard on. Based on some of the animal models, we have identified a molecular signature of inflammatory MS that is very predictive of future events and we are hoping that that will help us differentiate patients. In other words, not just treat every MS patient the same, but identify whether they need a very powerful immunosuppressant drug, or a mildly immunosuppressant drug, or no treatment at all.

If you have a patient who has one attack and never has any other problem with their MS, then they do not need to be on any treatment. Unfortunately, we do not have predictive value at this point for any molecule or any other attribute of the patient at this point in time. We are trying to remedy that.

That is one very practical aspect of our work in trying to understand the biology of the disease better--identifying molecules that are associated with future damage and inflammation and using those in a predictive manner in patients to guide treatment.

Another important aspect is the attempt to understand the biology of neuroinflammation and how it causes both demyelination and progressive injury to neurons.

References:

Pachner AR, DiSano K, Royce DB, Gilli F. Clinical utility of a molecular signature in inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm.2019;6(1):e520.

Andrew R. Pachner, MD is the Murray B. Bornstein professor of neurology at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and director of the Multiple Sclerosis Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. We spoke to Dr. Pachner about his research into the molecular processes of multiple sclerosis (MS) and the potential impact on patient management.

What do we know about the molecular processes behind relapsing-remitting and progressive MS?

DR. PACHNER: The progress--in terms of molecules--has not been rapid in the field of MS. The only molecular biomarker we use in practice is oligoclonal bands or other measures of immunoglobulin production in the nervous system, and that biomarker was described in 1942. So, it has been a long time since we have seen a relevant molecule that we can use clinically.

But there has been a lot of progress in the general field of neuroinflammation. MS is one of a large number of diseases that results in neuroinflammation and demyelination.

One thing we have learned over time is that there are many different subtypes of MS. They probably have some shared molecular processes, but they also are likely to have divergent molecular processes.

Over the past 5 to 10 years, researchers have been interested in trying to dissect some of the molecular aspects of MS to identify biomarkers that can, in turn, differentiate subtypes of MS. This will help to identify different ways of treating MS that are optimal for individual patients. It is clear that each patient is quite different and unlikely to be standardized in the way they respond to treatment.

The degree to which relapsing-remitting and progressive MS are differentiated on the molecular level is dependent on how much influence there is of the immune system in the periphery. When MS first starts in a patient, the brain has either no or a very primitive immune system, and then over time it changes, and it becomes much more immune-oriented and populated by immune cells and molecules. So, there’s a trend over time of the central nervous system becoming increasingly populated by immune cells and able to make immune molecules.

What has your recent research on murine models representing these disease patterns shown?

DR. PACHNER: Even though in humans there is a continuum from relapsing remitting to progressive, it is not like they are completely separate. Frequently in the middle of relapsing-remitting disease there is some progression over time.

In mouse models, we like things to be very clear and separate. We try to make things as simple as possible because of the complexity of the nervous and immune systems.

The simple model for the relapsing-remitting disease is experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the most commonly studied model of neuroinflammation.

For the progressive form of MS, we use the Theiler’s virus model, which is a type of virus called the picornavirus that is injected into the brain of mice resulting in a slowly progressive, chronic viral infection that looks very much like progressive MS.

In EAE, the disease is induced by presenting an antigen to the peripheral immune system, allowing cells from the peripheral immune system to enter into the central nervous system. It is a manifestation of inflammation and the immune response is in the periphery. In the Theiler’s model, it is a localized process within the central nervous system because the virus is injected directly into the brain.

We found that in EAE the pattern is very much dominated by what happens in the periphery and the injury is very transient. There are cells that enter the nervous system that cause inflammation and damage, but there are also processes that downregulate those cells and processes and eventually the animal improves--similar to an MS attack.

By contrast, in the Theiler’s model there is progressive injury that is dominated by two molecular processes in the central nervous system that we do not see in relapsing-remitting MS or in EAE, and that is the activation of Type 1 interferons and also a very pronounced immunoglobulin production along with all the molecules that help support plasma cells making immunoglobulin.

These are two different animal models that provide us insight into how the central nervous system can be injured in the course of neuroinflammation and they look to be very different in how they manifest themselves, both in the periphery and in the central nervous system.

How may these new findings impact the future management and treatment of MS?

DR. PACHNER: When I see a patient with MS, I tell them that we absolutely need to focus on your own disease and how it responds, rather than taking too much guidance from MS as a whole. Because each patient with MS is different.

One of the things that we have tried to do is to identify molecular markers that might help us in management and treatment. As an example, we have learned that some patients who present with their first episode of MS do very poorly. These patients have many more attacks and/or have very aggressive progression in terms of their disability so that they potentially could be in a wheelchair within a few years. Other patients have what we call a benign variant MS. These patients may have an initial episode that is not that different than the other patient, but this type of patient may not have anything else for the rest of their life.

We would like to have some differentiation of those two types of patients. In the first example you can try to be very aggressive and minimize the neuroinflammation with powerful immune-suppressing drugs that have a high risk of causing side effects, such as cancer or opportunistic infections, but on the other hand may have a high benefit in preventing future inflammatory events and progressive injury. But that would not be the correct treatment choice for the second patient example.

It would be nice to tailor treatment to a predictive biomarker. That is something we have been working very hard on. Based on some of the animal models, we have identified a molecular signature of inflammatory MS that is very predictive of future events and we are hoping that that will help us differentiate patients. In other words, not just treat every MS patient the same, but identify whether they need a very powerful immunosuppressant drug, or a mildly immunosuppressant drug, or no treatment at all.

If you have a patient who has one attack and never has any other problem with their MS, then they do not need to be on any treatment. Unfortunately, we do not have predictive value at this point for any molecule or any other attribute of the patient at this point in time. We are trying to remedy that.

That is one very practical aspect of our work in trying to understand the biology of the disease better--identifying molecules that are associated with future damage and inflammation and using those in a predictive manner in patients to guide treatment.

Another important aspect is the attempt to understand the biology of neuroinflammation and how it causes both demyelination and progressive injury to neurons.

References:

Pachner AR, DiSano K, Royce DB, Gilli F. Clinical utility of a molecular signature in inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm.2019;6(1):e520.

Andrew R. Pachner, MD is the Murray B. Bornstein professor of neurology at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and director of the Multiple Sclerosis Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. We spoke to Dr. Pachner about his research into the molecular processes of multiple sclerosis (MS) and the potential impact on patient management.

What do we know about the molecular processes behind relapsing-remitting and progressive MS?

DR. PACHNER: The progress--in terms of molecules--has not been rapid in the field of MS. The only molecular biomarker we use in practice is oligoclonal bands or other measures of immunoglobulin production in the nervous system, and that biomarker was described in 1942. So, it has been a long time since we have seen a relevant molecule that we can use clinically.

But there has been a lot of progress in the general field of neuroinflammation. MS is one of a large number of diseases that results in neuroinflammation and demyelination.

One thing we have learned over time is that there are many different subtypes of MS. They probably have some shared molecular processes, but they also are likely to have divergent molecular processes.

Over the past 5 to 10 years, researchers have been interested in trying to dissect some of the molecular aspects of MS to identify biomarkers that can, in turn, differentiate subtypes of MS. This will help to identify different ways of treating MS that are optimal for individual patients. It is clear that each patient is quite different and unlikely to be standardized in the way they respond to treatment.

The degree to which relapsing-remitting and progressive MS are differentiated on the molecular level is dependent on how much influence there is of the immune system in the periphery. When MS first starts in a patient, the brain has either no or a very primitive immune system, and then over time it changes, and it becomes much more immune-oriented and populated by immune cells and molecules. So, there’s a trend over time of the central nervous system becoming increasingly populated by immune cells and able to make immune molecules.

What has your recent research on murine models representing these disease patterns shown?

DR. PACHNER: Even though in humans there is a continuum from relapsing remitting to progressive, it is not like they are completely separate. Frequently in the middle of relapsing-remitting disease there is some progression over time.

In mouse models, we like things to be very clear and separate. We try to make things as simple as possible because of the complexity of the nervous and immune systems.

The simple model for the relapsing-remitting disease is experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the most commonly studied model of neuroinflammation.

For the progressive form of MS, we use the Theiler’s virus model, which is a type of virus called the picornavirus that is injected into the brain of mice resulting in a slowly progressive, chronic viral infection that looks very much like progressive MS.

In EAE, the disease is induced by presenting an antigen to the peripheral immune system, allowing cells from the peripheral immune system to enter into the central nervous system. It is a manifestation of inflammation and the immune response is in the periphery. In the Theiler’s model, it is a localized process within the central nervous system because the virus is injected directly into the brain.

We found that in EAE the pattern is very much dominated by what happens in the periphery and the injury is very transient. There are cells that enter the nervous system that cause inflammation and damage, but there are also processes that downregulate those cells and processes and eventually the animal improves--similar to an MS attack.

By contrast, in the Theiler’s model there is progressive injury that is dominated by two molecular processes in the central nervous system that we do not see in relapsing-remitting MS or in EAE, and that is the activation of Type 1 interferons and also a very pronounced immunoglobulin production along with all the molecules that help support plasma cells making immunoglobulin.

These are two different animal models that provide us insight into how the central nervous system can be injured in the course of neuroinflammation and they look to be very different in how they manifest themselves, both in the periphery and in the central nervous system.

How may these new findings impact the future management and treatment of MS?

DR. PACHNER: When I see a patient with MS, I tell them that we absolutely need to focus on your own disease and how it responds, rather than taking too much guidance from MS as a whole. Because each patient with MS is different.

One of the things that we have tried to do is to identify molecular markers that might help us in management and treatment. As an example, we have learned that some patients who present with their first episode of MS do very poorly. These patients have many more attacks and/or have very aggressive progression in terms of their disability so that they potentially could be in a wheelchair within a few years. Other patients have what we call a benign variant MS. These patients may have an initial episode that is not that different than the other patient, but this type of patient may not have anything else for the rest of their life.

We would like to have some differentiation of those two types of patients. In the first example you can try to be very aggressive and minimize the neuroinflammation with powerful immune-suppressing drugs that have a high risk of causing side effects, such as cancer or opportunistic infections, but on the other hand may have a high benefit in preventing future inflammatory events and progressive injury. But that would not be the correct treatment choice for the second patient example.

It would be nice to tailor treatment to a predictive biomarker. That is something we have been working very hard on. Based on some of the animal models, we have identified a molecular signature of inflammatory MS that is very predictive of future events and we are hoping that that will help us differentiate patients. In other words, not just treat every MS patient the same, but identify whether they need a very powerful immunosuppressant drug, or a mildly immunosuppressant drug, or no treatment at all.

If you have a patient who has one attack and never has any other problem with their MS, then they do not need to be on any treatment. Unfortunately, we do not have predictive value at this point for any molecule or any other attribute of the patient at this point in time. We are trying to remedy that.

That is one very practical aspect of our work in trying to understand the biology of the disease better--identifying molecules that are associated with future damage and inflammation and using those in a predictive manner in patients to guide treatment.

Another important aspect is the attempt to understand the biology of neuroinflammation and how it causes both demyelination and progressive injury to neurons.

References:

Pachner AR, DiSano K, Royce DB, Gilli F. Clinical utility of a molecular signature in inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm.2019;6(1):e520.

Treatment Facility: An Important Prognostic Factor for Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma Survival (FULL)

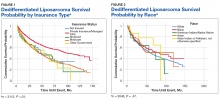

Approximately 17% to 25% of all softtissue sarcomas (STS) are liposarcomas, making liposarcoma the most common type of STS.1 The 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) classification separates liposarcoma into 4 histologic subtypes: atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated (ALT/ WDLPS), dedifferentiated (DDLPS), myxoid, and pleomorphic.2 Each subtype has unique histology, morphology, and natural history. WDLPS and DDLPS are the most common histologic subtypes, comprising approximately 50% of all sarcomas that arise in the retroperitoneum.3 DDLPS represents 18% of all liposarcomas, making it the second most common subtype of liposarcoma.4

In 1979, DDLPS was first characterized.5 Most (90%) cases of DDLPS present de novo, whereas the other 10% transform from preexisting low-grade WDLPS.2 DDLPSs are formed by an amplification of 12q14-15 involving the MDM2 gene.4 These malignancies most commonly present in the retroperitoneum as a large painless mass, consisting of both fatty and nonfatty components.2 Primary site has been previously reported as a major prognostic factor for DDLPSs, with retroperitoneal DDLPSs demonstrating the worst prognosis.6 DDLPSs have a high risk of local recurrence, with some reports estimating recurrence rates approaching 40%.2 Overall mortality at 5 years for DDLPS is estimated to be between 30% and 40%.4

Previous literature has determined that median income, race, health insurance, and facility type are related to survival outcomes for patients with DDLPS.7-9 When comparing the most common types of cancers, residents of poorer US counties consistently had a higher risk of mortality than residents in affluent US counties, and all racial minorities showed worse survival outcomes when compared with white patients.7 Differences in survival outcomes have been reported in patients attending different treatment facilities for other cancers including pancreatic cancers, glioblastomas, and oral cancers, with multiple studies concluding that academic and research programs are associated with the longest survival outcomes.10-12 For many cancers, insurance status has been shown to be a significant prognostic factor, with private insurance typically resulting in the best prognosis.8,9

The goal of this retrospective study was to assess the prognostic effects of socioeconomic variables on the overall survival (OS) probabilities in a large cohort of DDLPS patients in order to inform clinicians about a potentially at-risk population.

Method

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was created by the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The NCDB is the largest cancer database in the US and includes data on almost 70% of US patients with cancer. CoC-accredited cancer programs add data on patients with cancer to the NCDB. The authors accessed the NCDB data through the use of the NCDB Participant Use File program.

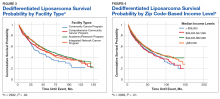

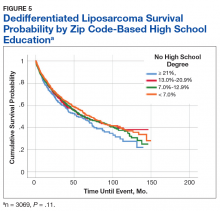

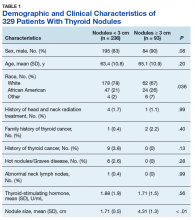

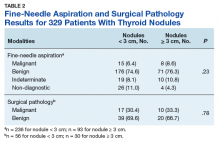

Patients’ data from 2004 through 2015 were abstracted. Only patients with the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology histology code 8858, corresponding to DDLPS, were analyzed. Patients with other comorbid malignant tumors were excluded to accurately capture the true survival rates for DDLPS. Variables analyzed included age, sex, race, insurance status, treatment facility type, median household income by zip code, and percentage of adults in the patient’s zip code with no high school (HS) education.