User login

A 51-year-old woman presented for a routine full body skin exam after vacationing in Hawaii.

Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) results from a dysfunction of the adrenal glands, which may be secondary to autoimmune diseases, genetic conditions, infections, and vasculopathies,or may be drug-induced (e.g. checkpoint inhibitors), among others . In contrast, secondary adrenal insufficiency results from pituitary dysfunction of low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in developed countries is autoimmune adrenalitis, which accounts for upwards of 90% of cases. Typically, 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies are identified and account for destruction of the adrenal cortex through cell-mediated and humoral immune responses.

Palmar creases, subungual surfaces, sites of trauma, and joint spaces (including the knees, spine, elbows, and shoulders) are commonly affected. Hair depletes in the pubic area and axillary vaults. Nevi may also appear darker. In patients with autoimmune adrenalitis, vitiligo may be seen secondary to autoimmune destruction of melanocytes.

Diagnosis may be difficult in the early stages, but historical findings of fatigue and clinical findings of hyperpigmentation in classic areas may prompt appropriate lab screening workup. It is essential to determine whether adrenal insufficiency is primary or secondary. Evaluation of decreased cortisol production, determination of whether production is ACTH-dependent or -independent, and evaluation for the underlying causes of adrenal dysfunction are important. Lab screening includes morning serum cortisol, morning ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test, fasting CBC with differential, and CMP to evaluate for normocytic normochromic anemia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, plasma renin/aldosterone ratio, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies.

Management strategies of primary adrenal insufficiency require corticosteroid supplementation and multidisciplinary collaboration with endocrinology. If untreated, primary adrenal insufficiency can be fatal. Adrenal crisis is a critical condition following a precipitating event, such as GI infection, fever, acute stress, and/or untreated adrenal or pituitary disorders. Clinical findings include acute shock with hypotension, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, back or leg pain, and a change in mental status. In this scenario, increasing the dose of corticosteroid supplementation is essential for reducing mortality.

Upon examining this patient’s new skin findings of hyperpigmentation and discussing her fatigue, primary adrenal insufficiency was suspected. With further prompting, the patient reported an ICU hospitalization several months prior because of sepsis originating from a peritonsillar abscess. With these clinical and historical findings, preliminary workup was conducted by dermatology, which included morning cortisol level, ACTH, CBC with differential, CMP, plasma renin-aldosterone ratio, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. Work up demonstrated a low morning cortisol level of 1.3 mcg/dL, an elevated ACTH of 2,739 pg/mL, and positive 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. The patient was urgently referred to endocrinology and started on oral hydrocortisone. Her fatigue immediately improved, and at 1-year follow-up with dermatology, her mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation had subsided dramatically.

Dermatologists can play a major role in the early diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency, which is essential for reducing patient morbidity and mortality. Skin findings on full body skin exams can clue in dermatologists for ordering preliminary workup to expedite care for these patients.

The case and photos were submitted by Dr. Akhiyat, Scripps Clinic Medical Group, La Jolla, California. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 May;70(5):Supplement 1AB118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.491.

Michels A, Michels N. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Apr 1;89(7):563-568.

Kauzman A et al. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004 Nov;70(10):682-683.

Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) results from a dysfunction of the adrenal glands, which may be secondary to autoimmune diseases, genetic conditions, infections, and vasculopathies,or may be drug-induced (e.g. checkpoint inhibitors), among others . In contrast, secondary adrenal insufficiency results from pituitary dysfunction of low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in developed countries is autoimmune adrenalitis, which accounts for upwards of 90% of cases. Typically, 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies are identified and account for destruction of the adrenal cortex through cell-mediated and humoral immune responses.

Palmar creases, subungual surfaces, sites of trauma, and joint spaces (including the knees, spine, elbows, and shoulders) are commonly affected. Hair depletes in the pubic area and axillary vaults. Nevi may also appear darker. In patients with autoimmune adrenalitis, vitiligo may be seen secondary to autoimmune destruction of melanocytes.

Diagnosis may be difficult in the early stages, but historical findings of fatigue and clinical findings of hyperpigmentation in classic areas may prompt appropriate lab screening workup. It is essential to determine whether adrenal insufficiency is primary or secondary. Evaluation of decreased cortisol production, determination of whether production is ACTH-dependent or -independent, and evaluation for the underlying causes of adrenal dysfunction are important. Lab screening includes morning serum cortisol, morning ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test, fasting CBC with differential, and CMP to evaluate for normocytic normochromic anemia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, plasma renin/aldosterone ratio, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies.

Management strategies of primary adrenal insufficiency require corticosteroid supplementation and multidisciplinary collaboration with endocrinology. If untreated, primary adrenal insufficiency can be fatal. Adrenal crisis is a critical condition following a precipitating event, such as GI infection, fever, acute stress, and/or untreated adrenal or pituitary disorders. Clinical findings include acute shock with hypotension, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, back or leg pain, and a change in mental status. In this scenario, increasing the dose of corticosteroid supplementation is essential for reducing mortality.

Upon examining this patient’s new skin findings of hyperpigmentation and discussing her fatigue, primary adrenal insufficiency was suspected. With further prompting, the patient reported an ICU hospitalization several months prior because of sepsis originating from a peritonsillar abscess. With these clinical and historical findings, preliminary workup was conducted by dermatology, which included morning cortisol level, ACTH, CBC with differential, CMP, plasma renin-aldosterone ratio, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. Work up demonstrated a low morning cortisol level of 1.3 mcg/dL, an elevated ACTH of 2,739 pg/mL, and positive 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. The patient was urgently referred to endocrinology and started on oral hydrocortisone. Her fatigue immediately improved, and at 1-year follow-up with dermatology, her mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation had subsided dramatically.

Dermatologists can play a major role in the early diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency, which is essential for reducing patient morbidity and mortality. Skin findings on full body skin exams can clue in dermatologists for ordering preliminary workup to expedite care for these patients.

The case and photos were submitted by Dr. Akhiyat, Scripps Clinic Medical Group, La Jolla, California. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 May;70(5):Supplement 1AB118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.491.

Michels A, Michels N. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Apr 1;89(7):563-568.

Kauzman A et al. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004 Nov;70(10):682-683.

Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) results from a dysfunction of the adrenal glands, which may be secondary to autoimmune diseases, genetic conditions, infections, and vasculopathies,or may be drug-induced (e.g. checkpoint inhibitors), among others . In contrast, secondary adrenal insufficiency results from pituitary dysfunction of low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in developed countries is autoimmune adrenalitis, which accounts for upwards of 90% of cases. Typically, 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies are identified and account for destruction of the adrenal cortex through cell-mediated and humoral immune responses.

Palmar creases, subungual surfaces, sites of trauma, and joint spaces (including the knees, spine, elbows, and shoulders) are commonly affected. Hair depletes in the pubic area and axillary vaults. Nevi may also appear darker. In patients with autoimmune adrenalitis, vitiligo may be seen secondary to autoimmune destruction of melanocytes.

Diagnosis may be difficult in the early stages, but historical findings of fatigue and clinical findings of hyperpigmentation in classic areas may prompt appropriate lab screening workup. It is essential to determine whether adrenal insufficiency is primary or secondary. Evaluation of decreased cortisol production, determination of whether production is ACTH-dependent or -independent, and evaluation for the underlying causes of adrenal dysfunction are important. Lab screening includes morning serum cortisol, morning ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test, fasting CBC with differential, and CMP to evaluate for normocytic normochromic anemia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, plasma renin/aldosterone ratio, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies.

Management strategies of primary adrenal insufficiency require corticosteroid supplementation and multidisciplinary collaboration with endocrinology. If untreated, primary adrenal insufficiency can be fatal. Adrenal crisis is a critical condition following a precipitating event, such as GI infection, fever, acute stress, and/or untreated adrenal or pituitary disorders. Clinical findings include acute shock with hypotension, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, back or leg pain, and a change in mental status. In this scenario, increasing the dose of corticosteroid supplementation is essential for reducing mortality.

Upon examining this patient’s new skin findings of hyperpigmentation and discussing her fatigue, primary adrenal insufficiency was suspected. With further prompting, the patient reported an ICU hospitalization several months prior because of sepsis originating from a peritonsillar abscess. With these clinical and historical findings, preliminary workup was conducted by dermatology, which included morning cortisol level, ACTH, CBC with differential, CMP, plasma renin-aldosterone ratio, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. Work up demonstrated a low morning cortisol level of 1.3 mcg/dL, an elevated ACTH of 2,739 pg/mL, and positive 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. The patient was urgently referred to endocrinology and started on oral hydrocortisone. Her fatigue immediately improved, and at 1-year follow-up with dermatology, her mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation had subsided dramatically.

Dermatologists can play a major role in the early diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency, which is essential for reducing patient morbidity and mortality. Skin findings on full body skin exams can clue in dermatologists for ordering preliminary workup to expedite care for these patients.

The case and photos were submitted by Dr. Akhiyat, Scripps Clinic Medical Group, La Jolla, California. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 May;70(5):Supplement 1AB118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.491.

Michels A, Michels N. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Apr 1;89(7):563-568.

Kauzman A et al. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004 Nov;70(10):682-683.

How Old Are You? Stand on One Leg and I’ll Tell You

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

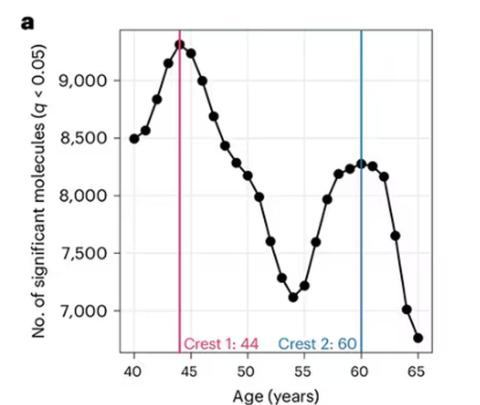

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

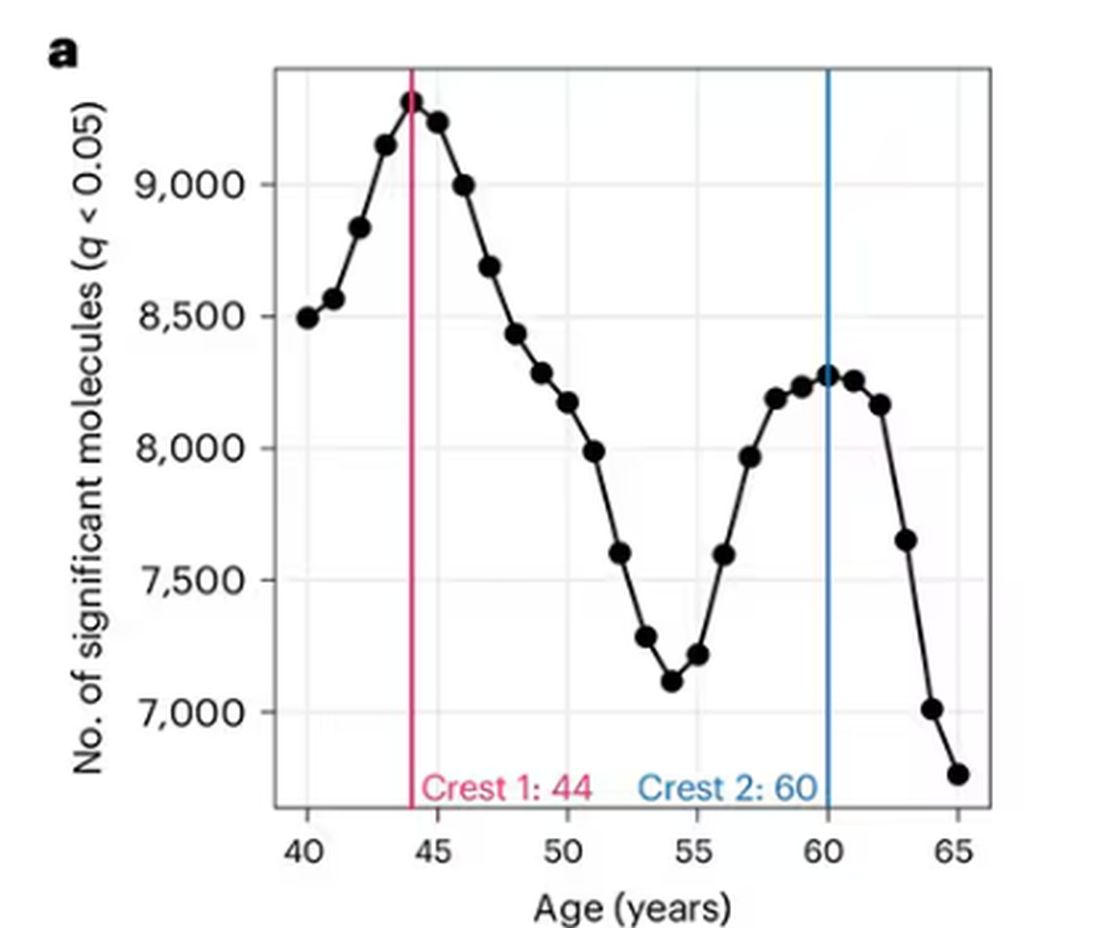

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

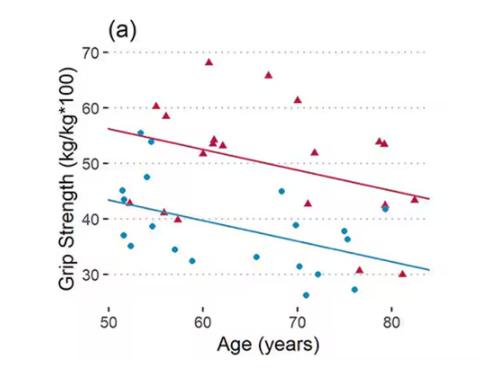

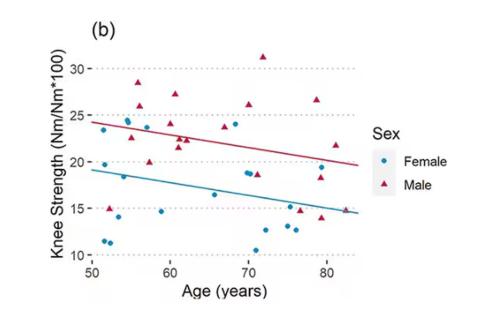

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

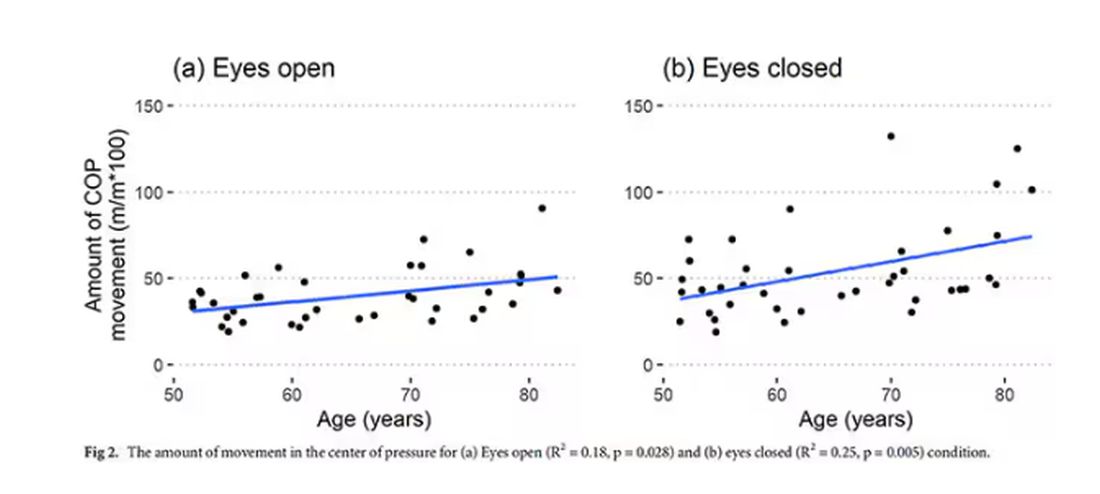

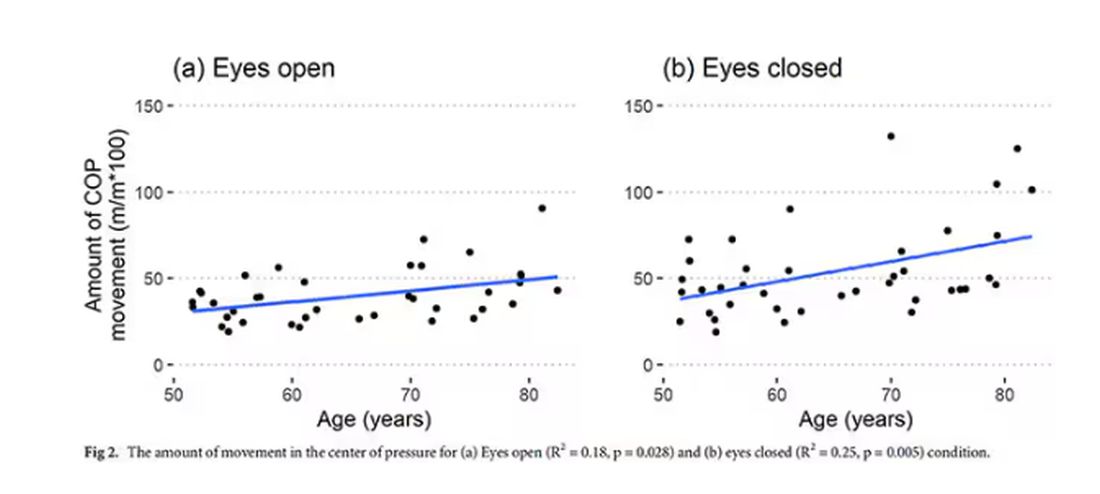

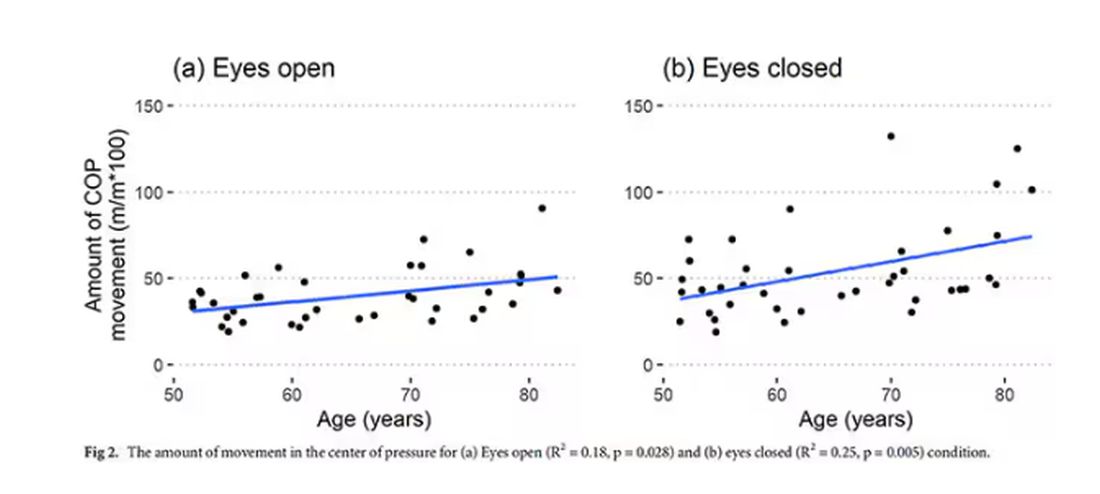

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

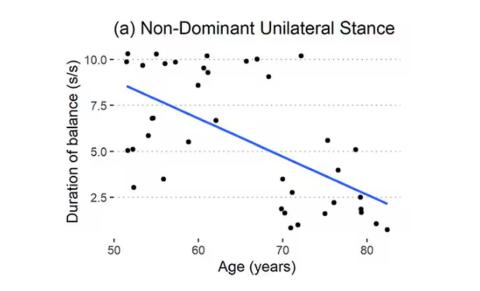

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

H pylori: ACG Guideline Advises New Approaches to Treatment

Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common human bacterial chronic infections globally. Its prevalence has actually decreased in North America in recent years, although its current range of approximately 30%-40% remains substantial given the potential clinical implications of infection.

Standards have changed considerably regarding the testing, treatment, and follow-up of H pylori. This is made clear by the just-published clinical practice guideline from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), which provides several new recommendations based on recent scientific evidence that should change your clinical approach to managing this common infection.

This discussion aims to synthesize and highlight key concepts from the ACG’s comprehensive publication.

Who Should Be Tested and Treated?

The cardinal diseases caused by H pylori have traditionally included peptic ulcer disease, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, and dyspepsia.

Additional associations have been made with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and otherwise unexplained iron deficiency.

New evidence suggests that patients taking long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including low-dose aspirin, are relatively more susceptible to infection.

The ACG’s guideline also recommends testing persons at an increased risk for gastric adenocarcinoma (eg, those with autoimmune gastritis, current or history of premalignant conditions, or first-degree relative with gastric cancer), as well as household members of patients with a positive nonserologic test for H pylori.

The authors note that those with an indication for testing should be offered treatment if determined to have an infection. These patients should also undergo a posttreatment test-of-cure, which should occur at least 4 weeks afterwards using a urea breath test, fecal antigen test, or gastric biopsy.

Caveats to Treatment

Patients with H pylori infections are advised to undergo treatment for a duration of 14 days. Some of the commercial prepackaged H pylori treatment options (eg, Pylera, which contains bismuth subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline) are dispensed in regimens lasting only 10 days and currently are viewed as inadequate.

In the United States, the patterns of antibiotic resistance for the previously used standard drugs in the treatment of H pylori have increased considerably. They range from 32% for clarithromycin, 38% for levofloxacin, and 42% for metronidazole, in contrast to 3% for amoxicillin, 1% for tetracycline, and 0% for rifabutin.

Clarithromycin- and levofloxacin-containing treatments should be avoided in treatment-naive patients unless specifically directed following the results of susceptibility tests with either a phenotypic method (culture-based) or a molecular method (polymerase chain reaction or next-generation sequencing). Notably, the mutations responsible for both clarithromycin and levofloxacin resistance may be detectable by stool-based testing.

Maintenance of intragastric acid suppression is key to H pylori eradication, as elevated intragastric pH promotes active replication of H pylori and makes it more susceptible to bactericidal antibiotics.

Therefore, the use of histamine-2 receptors is not recommended, as they are inadequate for achieving acid suppression. Instead, a dual-based therapy of either the potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan (20 mg) or a high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and amoxicillin, administered twice daily, is effective, although this finding is based on limited evidence.

Treatment-Naive Patients

In treatment-naive patients without penicillin allergy and for whom antibiotic susceptibility testing has not been obtained, the guideline offers its strongest recommendation for bismuth quadruple therapy. This therapy typically consists of a PPI, bismuth subcitrate or subsalicylate, tetracycline, and metronidazole.

Among those with a penicillin allergy, bismuth quadruple therapy is also the primary treatment choice. The authors suggest that patients with a suspected allergy are referred to an allergist for possible penicillin desensitization, given that less than 1% of the population is thought to present with a “true” allergy.

The guideline also presented conditional recommendations, based on low- to moderate-quality evidence, for using a rifabutin-based triple regimen of omeprazole, amoxicillin, and rifabutin (Talicia); a PCAB-based dual regimen of vonoprazan and amoxicillin (Voquezna Dual Pak); and a PCAB-based triple regimen of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (Voquezna Triple Pak). In patients with unknown clarithromycin susceptibility, the PCAB-based triple therapy is preferred over PPI-clarithromycin triple therapy.

Although probiotics have been suggested to possibly lead to increased effectiveness or tolerability for H pylori eradication, this was based on studies with significant heterogeneity in their designs. At present, no high-quality data support probiotic therapy.

Clinicians may substitute doxycycline for tetracycline due to availability or cost, and also may prescribe metronidazole at a lower dose than recommended (1.5-2 g/d) to limit side effects. Both modifications have been associated with lower rates of H pylori eradication and are not recommended.

Treatment-Experienced Patients

Quadruple bismuth therapy is the optimal approach among treatment-experienced patients with persistent H pylori infection who have not previously received this therapy. However, this recommendation was rated as conditional, given that it was based on a low quality of evidence.

The guideline offered other recommendations for treatment-experienced patients with persistent infection who had received bismuth quadruple therapy — also conditionally based on a low quality of evidence.

In such patients, it is recommended to consider the use of a rifabutin-based triple therapy (ie, a PPI standard to double dose, amoxicillin, and rifabutin) and a levofloxacin-based triple therapy (ie, a PPI standard dose, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole).

Although significant evidence gaps prevented the authors from providing formal recommendations, they included a PCAB-based triple therapy of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (Voquezna Triple Pak) and a high-dose dual therapy of either vonoprazan (20 mg) or PPI (double dose) and amoxicillin among their suggested salvage regimens for these patients.

A New Standard

We must recognize, however, that there are still substantial evidence gaps, particularly around the use of a PCAB-based regimen and its relative advantages over a standard or high-dose PPI-based regimen. This may be of particular importance based on the variable prevalence of cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) polymorphisms in the specific patient populations, as PCABs are not metabolized by CYP2C19.

Reviewing the entirety of the ACG’s clinical guideline is encouraged for additional details about the management of H pylori beyond what is highlighted herein.

Dr. Johnson, Professor of Medicine, Chief of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Virginia, disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common human bacterial chronic infections globally. Its prevalence has actually decreased in North America in recent years, although its current range of approximately 30%-40% remains substantial given the potential clinical implications of infection.

Standards have changed considerably regarding the testing, treatment, and follow-up of H pylori. This is made clear by the just-published clinical practice guideline from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), which provides several new recommendations based on recent scientific evidence that should change your clinical approach to managing this common infection.

This discussion aims to synthesize and highlight key concepts from the ACG’s comprehensive publication.

Who Should Be Tested and Treated?

The cardinal diseases caused by H pylori have traditionally included peptic ulcer disease, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, and dyspepsia.

Additional associations have been made with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and otherwise unexplained iron deficiency.

New evidence suggests that patients taking long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including low-dose aspirin, are relatively more susceptible to infection.

The ACG’s guideline also recommends testing persons at an increased risk for gastric adenocarcinoma (eg, those with autoimmune gastritis, current or history of premalignant conditions, or first-degree relative with gastric cancer), as well as household members of patients with a positive nonserologic test for H pylori.

The authors note that those with an indication for testing should be offered treatment if determined to have an infection. These patients should also undergo a posttreatment test-of-cure, which should occur at least 4 weeks afterwards using a urea breath test, fecal antigen test, or gastric biopsy.

Caveats to Treatment

Patients with H pylori infections are advised to undergo treatment for a duration of 14 days. Some of the commercial prepackaged H pylori treatment options (eg, Pylera, which contains bismuth subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline) are dispensed in regimens lasting only 10 days and currently are viewed as inadequate.

In the United States, the patterns of antibiotic resistance for the previously used standard drugs in the treatment of H pylori have increased considerably. They range from 32% for clarithromycin, 38% for levofloxacin, and 42% for metronidazole, in contrast to 3% for amoxicillin, 1% for tetracycline, and 0% for rifabutin.

Clarithromycin- and levofloxacin-containing treatments should be avoided in treatment-naive patients unless specifically directed following the results of susceptibility tests with either a phenotypic method (culture-based) or a molecular method (polymerase chain reaction or next-generation sequencing). Notably, the mutations responsible for both clarithromycin and levofloxacin resistance may be detectable by stool-based testing.

Maintenance of intragastric acid suppression is key to H pylori eradication, as elevated intragastric pH promotes active replication of H pylori and makes it more susceptible to bactericidal antibiotics.

Therefore, the use of histamine-2 receptors is not recommended, as they are inadequate for achieving acid suppression. Instead, a dual-based therapy of either the potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan (20 mg) or a high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and amoxicillin, administered twice daily, is effective, although this finding is based on limited evidence.

Treatment-Naive Patients

In treatment-naive patients without penicillin allergy and for whom antibiotic susceptibility testing has not been obtained, the guideline offers its strongest recommendation for bismuth quadruple therapy. This therapy typically consists of a PPI, bismuth subcitrate or subsalicylate, tetracycline, and metronidazole.

Among those with a penicillin allergy, bismuth quadruple therapy is also the primary treatment choice. The authors suggest that patients with a suspected allergy are referred to an allergist for possible penicillin desensitization, given that less than 1% of the population is thought to present with a “true” allergy.

The guideline also presented conditional recommendations, based on low- to moderate-quality evidence, for using a rifabutin-based triple regimen of omeprazole, amoxicillin, and rifabutin (Talicia); a PCAB-based dual regimen of vonoprazan and amoxicillin (Voquezna Dual Pak); and a PCAB-based triple regimen of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (Voquezna Triple Pak). In patients with unknown clarithromycin susceptibility, the PCAB-based triple therapy is preferred over PPI-clarithromycin triple therapy.

Although probiotics have been suggested to possibly lead to increased effectiveness or tolerability for H pylori eradication, this was based on studies with significant heterogeneity in their designs. At present, no high-quality data support probiotic therapy.

Clinicians may substitute doxycycline for tetracycline due to availability or cost, and also may prescribe metronidazole at a lower dose than recommended (1.5-2 g/d) to limit side effects. Both modifications have been associated with lower rates of H pylori eradication and are not recommended.

Treatment-Experienced Patients

Quadruple bismuth therapy is the optimal approach among treatment-experienced patients with persistent H pylori infection who have not previously received this therapy. However, this recommendation was rated as conditional, given that it was based on a low quality of evidence.

The guideline offered other recommendations for treatment-experienced patients with persistent infection who had received bismuth quadruple therapy — also conditionally based on a low quality of evidence.

In such patients, it is recommended to consider the use of a rifabutin-based triple therapy (ie, a PPI standard to double dose, amoxicillin, and rifabutin) and a levofloxacin-based triple therapy (ie, a PPI standard dose, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole).

Although significant evidence gaps prevented the authors from providing formal recommendations, they included a PCAB-based triple therapy of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (Voquezna Triple Pak) and a high-dose dual therapy of either vonoprazan (20 mg) or PPI (double dose) and amoxicillin among their suggested salvage regimens for these patients.

A New Standard

We must recognize, however, that there are still substantial evidence gaps, particularly around the use of a PCAB-based regimen and its relative advantages over a standard or high-dose PPI-based regimen. This may be of particular importance based on the variable prevalence of cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) polymorphisms in the specific patient populations, as PCABs are not metabolized by CYP2C19.

Reviewing the entirety of the ACG’s clinical guideline is encouraged for additional details about the management of H pylori beyond what is highlighted herein.

Dr. Johnson, Professor of Medicine, Chief of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Virginia, disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common human bacterial chronic infections globally. Its prevalence has actually decreased in North America in recent years, although its current range of approximately 30%-40% remains substantial given the potential clinical implications of infection.

Standards have changed considerably regarding the testing, treatment, and follow-up of H pylori. This is made clear by the just-published clinical practice guideline from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), which provides several new recommendations based on recent scientific evidence that should change your clinical approach to managing this common infection.

This discussion aims to synthesize and highlight key concepts from the ACG’s comprehensive publication.

Who Should Be Tested and Treated?

The cardinal diseases caused by H pylori have traditionally included peptic ulcer disease, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, and dyspepsia.

Additional associations have been made with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and otherwise unexplained iron deficiency.

New evidence suggests that patients taking long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including low-dose aspirin, are relatively more susceptible to infection.

The ACG’s guideline also recommends testing persons at an increased risk for gastric adenocarcinoma (eg, those with autoimmune gastritis, current or history of premalignant conditions, or first-degree relative with gastric cancer), as well as household members of patients with a positive nonserologic test for H pylori.

The authors note that those with an indication for testing should be offered treatment if determined to have an infection. These patients should also undergo a posttreatment test-of-cure, which should occur at least 4 weeks afterwards using a urea breath test, fecal antigen test, or gastric biopsy.

Caveats to Treatment

Patients with H pylori infections are advised to undergo treatment for a duration of 14 days. Some of the commercial prepackaged H pylori treatment options (eg, Pylera, which contains bismuth subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline) are dispensed in regimens lasting only 10 days and currently are viewed as inadequate.

In the United States, the patterns of antibiotic resistance for the previously used standard drugs in the treatment of H pylori have increased considerably. They range from 32% for clarithromycin, 38% for levofloxacin, and 42% for metronidazole, in contrast to 3% for amoxicillin, 1% for tetracycline, and 0% for rifabutin.

Clarithromycin- and levofloxacin-containing treatments should be avoided in treatment-naive patients unless specifically directed following the results of susceptibility tests with either a phenotypic method (culture-based) or a molecular method (polymerase chain reaction or next-generation sequencing). Notably, the mutations responsible for both clarithromycin and levofloxacin resistance may be detectable by stool-based testing.

Maintenance of intragastric acid suppression is key to H pylori eradication, as elevated intragastric pH promotes active replication of H pylori and makes it more susceptible to bactericidal antibiotics.

Therefore, the use of histamine-2 receptors is not recommended, as they are inadequate for achieving acid suppression. Instead, a dual-based therapy of either the potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan (20 mg) or a high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and amoxicillin, administered twice daily, is effective, although this finding is based on limited evidence.

Treatment-Naive Patients

In treatment-naive patients without penicillin allergy and for whom antibiotic susceptibility testing has not been obtained, the guideline offers its strongest recommendation for bismuth quadruple therapy. This therapy typically consists of a PPI, bismuth subcitrate or subsalicylate, tetracycline, and metronidazole.

Among those with a penicillin allergy, bismuth quadruple therapy is also the primary treatment choice. The authors suggest that patients with a suspected allergy are referred to an allergist for possible penicillin desensitization, given that less than 1% of the population is thought to present with a “true” allergy.

The guideline also presented conditional recommendations, based on low- to moderate-quality evidence, for using a rifabutin-based triple regimen of omeprazole, amoxicillin, and rifabutin (Talicia); a PCAB-based dual regimen of vonoprazan and amoxicillin (Voquezna Dual Pak); and a PCAB-based triple regimen of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (Voquezna Triple Pak). In patients with unknown clarithromycin susceptibility, the PCAB-based triple therapy is preferred over PPI-clarithromycin triple therapy.

Although probiotics have been suggested to possibly lead to increased effectiveness or tolerability for H pylori eradication, this was based on studies with significant heterogeneity in their designs. At present, no high-quality data support probiotic therapy.

Clinicians may substitute doxycycline for tetracycline due to availability or cost, and also may prescribe metronidazole at a lower dose than recommended (1.5-2 g/d) to limit side effects. Both modifications have been associated with lower rates of H pylori eradication and are not recommended.

Treatment-Experienced Patients

Quadruple bismuth therapy is the optimal approach among treatment-experienced patients with persistent H pylori infection who have not previously received this therapy. However, this recommendation was rated as conditional, given that it was based on a low quality of evidence.

The guideline offered other recommendations for treatment-experienced patients with persistent infection who had received bismuth quadruple therapy — also conditionally based on a low quality of evidence.

In such patients, it is recommended to consider the use of a rifabutin-based triple therapy (ie, a PPI standard to double dose, amoxicillin, and rifabutin) and a levofloxacin-based triple therapy (ie, a PPI standard dose, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole).

Although significant evidence gaps prevented the authors from providing formal recommendations, they included a PCAB-based triple therapy of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (Voquezna Triple Pak) and a high-dose dual therapy of either vonoprazan (20 mg) or PPI (double dose) and amoxicillin among their suggested salvage regimens for these patients.

A New Standard

We must recognize, however, that there are still substantial evidence gaps, particularly around the use of a PCAB-based regimen and its relative advantages over a standard or high-dose PPI-based regimen. This may be of particular importance based on the variable prevalence of cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) polymorphisms in the specific patient populations, as PCABs are not metabolized by CYP2C19.

Reviewing the entirety of the ACG’s clinical guideline is encouraged for additional details about the management of H pylori beyond what is highlighted herein.

Dr. Johnson, Professor of Medicine, Chief of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Virginia, disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Help Your Patients Reap the Benefits of Plant-Based Diets

Research pooled from nearly 100 studies has indicated that people who adhere to a vegan diet (ie, completely devoid of animal products) or a vegetarian diet (ie, devoid of meat, but may include dairy and eggs) are able to ward off some chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, optimize glycemic control, and decrease their risk for cancer compared with those who consume omnivorous diets.

Vegan and vegetarian diets, or flexitarian diets — which are less reliant on animal protein than the standard US diet but do not completely exclude meat, fish, eggs, or dairy — may promote homeostasis and decrease inflammation by providing more fiber, antioxidants, and unsaturated fatty acids than the typical Western diet.

Inflammation and Obesity

Adipose tissue is a major producer of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-6, whose presence then triggers a rush of acute-phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) by the liver. This process develops into chronic low-grade inflammation that can increase a person’s chances of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and related complications.

Adopting a plant-based diet can improve markers of chronic low-grade inflammation that can lead to chronic disease and worsen existent chronic disease. A meta-analysis of 29 studies encompassing nearly 2700 participants found that initiation of a plant-based diet showed significant improvement in CRP, IL-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1.

If we want to prevent these inflammatory disease states and their complications, the obvious response is to counsel patients to avoid excessive weight gain or to lose weight if obesity is their baseline. This can be tough for some patients, but it is nonetheless an important step in chronic disease prevention and management.

Plant-Based Diet for Type 2 Diabetes

According to a review of nine studies of patients living with type 2 diabetes who adhered to a plant-based diet, all but one found that this approach led to significantly lower A1c values than those seen in control groups. Six of the included studies reported that participants were able to decrease or discontinue medications for the management of diabetes. Researchers across all included studies also noted a decrease in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, as well as increased weight loss in participants in each intervention group.

Such improvements are probably the result of the increase in fiber intake that occurs with a plant-based diet. A high-fiber diet is known to promote improved glucose and lipid metabolism as well as weight loss.

It is also worth noting that participants in the intervention groups also experienced improvements in depression and less chronic pain than did those in the control groups.

Plant-Based Diet for Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Although the use of a plant-based diet in the prevention of CKD is well documented, adopting such diets for the treatment of CKD may intimidate both patients and practitioners owing to the high potassium and phosphorus content of many fruits and vegetables.

However, research indicates that the bioavailability of both potassium and phosphorus is lower in plant-based, whole foods than in preservatives and the highly processed food items that incorporate them. This makes a plant-based diet more viable than previously thought.

Diets rich in vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and legumes have been shown to decrease dietary acid load, both preventing and treating metabolic acidosis. Such diets have also been shown to decrease blood pressure and the risk for a decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate. This type of diet would also prioritize the unsaturated fatty acids and fiber-rich proteins such as avocados, beans, and nuts shown to improve dyslipidemia, which may occur alongside CKD.

Realistic Options for Patients on Medical Diets

There is one question that I always seem to get from when recommending a plant-based diet: “These patients already have so many restrictions. Why would you add more?” And my answer is also always the same: I don’t.

I rarely, if ever, recommend completely cutting out any food item or food group. Instead, I ask the patient to increase their intake of plant-based foods and only limit highly processed foods and fatty meats. By shifting a patient’s focus to beans; nuts; and low-carbohydrate, high-fiber fruits and vegetables, I am often opening up a whole new world of possibilities.

Instead of a sandwich with low-sodium turkey and cheese on white bread with a side of unsalted pretzels, I recommend a caprese salad with blueberries and almonds or a Southwest salad with black beans, corn, and avocado. I don’t encourage my patients to skip the foods that they love, but instead to only think about all the delicious plant-based options that will provide them with more than just calories.

Meat, dairy, seafood, and eggs can certainly be a part of a healthy diet, but what if our chronically ill patients, especially those with diabetes, had more options than just grilled chicken and green beans for every meal? What if we focus on decreasing dietary restrictions, incorporating a variety of nourishing foods, and educating our patients, instead of on portion control and moderation?

This is how I choose to incorporate plant-based diets into my practice to treat and prevent these chronic inflammatory conditions and promote sustainable, realistic change in my clients’ health.

Brandy Winfree Root, a renal dietitian in private practice in Mary Esther, Florida, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Research pooled from nearly 100 studies has indicated that people who adhere to a vegan diet (ie, completely devoid of animal products) or a vegetarian diet (ie, devoid of meat, but may include dairy and eggs) are able to ward off some chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, optimize glycemic control, and decrease their risk for cancer compared with those who consume omnivorous diets.

Vegan and vegetarian diets, or flexitarian diets — which are less reliant on animal protein than the standard US diet but do not completely exclude meat, fish, eggs, or dairy — may promote homeostasis and decrease inflammation by providing more fiber, antioxidants, and unsaturated fatty acids than the typical Western diet.

Inflammation and Obesity

Adipose tissue is a major producer of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-6, whose presence then triggers a rush of acute-phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) by the liver. This process develops into chronic low-grade inflammation that can increase a person’s chances of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and related complications.

Adopting a plant-based diet can improve markers of chronic low-grade inflammation that can lead to chronic disease and worsen existent chronic disease. A meta-analysis of 29 studies encompassing nearly 2700 participants found that initiation of a plant-based diet showed significant improvement in CRP, IL-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1.

If we want to prevent these inflammatory disease states and their complications, the obvious response is to counsel patients to avoid excessive weight gain or to lose weight if obesity is their baseline. This can be tough for some patients, but it is nonetheless an important step in chronic disease prevention and management.

Plant-Based Diet for Type 2 Diabetes

According to a review of nine studies of patients living with type 2 diabetes who adhered to a plant-based diet, all but one found that this approach led to significantly lower A1c values than those seen in control groups. Six of the included studies reported that participants were able to decrease or discontinue medications for the management of diabetes. Researchers across all included studies also noted a decrease in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, as well as increased weight loss in participants in each intervention group.

Such improvements are probably the result of the increase in fiber intake that occurs with a plant-based diet. A high-fiber diet is known to promote improved glucose and lipid metabolism as well as weight loss.

It is also worth noting that participants in the intervention groups also experienced improvements in depression and less chronic pain than did those in the control groups.

Plant-Based Diet for Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Although the use of a plant-based diet in the prevention of CKD is well documented, adopting such diets for the treatment of CKD may intimidate both patients and practitioners owing to the high potassium and phosphorus content of many fruits and vegetables.

However, research indicates that the bioavailability of both potassium and phosphorus is lower in plant-based, whole foods than in preservatives and the highly processed food items that incorporate them. This makes a plant-based diet more viable than previously thought.

Diets rich in vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and legumes have been shown to decrease dietary acid load, both preventing and treating metabolic acidosis. Such diets have also been shown to decrease blood pressure and the risk for a decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate. This type of diet would also prioritize the unsaturated fatty acids and fiber-rich proteins such as avocados, beans, and nuts shown to improve dyslipidemia, which may occur alongside CKD.

Realistic Options for Patients on Medical Diets

There is one question that I always seem to get from when recommending a plant-based diet: “These patients already have so many restrictions. Why would you add more?” And my answer is also always the same: I don’t.

I rarely, if ever, recommend completely cutting out any food item or food group. Instead, I ask the patient to increase their intake of plant-based foods and only limit highly processed foods and fatty meats. By shifting a patient’s focus to beans; nuts; and low-carbohydrate, high-fiber fruits and vegetables, I am often opening up a whole new world of possibilities.

Instead of a sandwich with low-sodium turkey and cheese on white bread with a side of unsalted pretzels, I recommend a caprese salad with blueberries and almonds or a Southwest salad with black beans, corn, and avocado. I don’t encourage my patients to skip the foods that they love, but instead to only think about all the delicious plant-based options that will provide them with more than just calories.

Meat, dairy, seafood, and eggs can certainly be a part of a healthy diet, but what if our chronically ill patients, especially those with diabetes, had more options than just grilled chicken and green beans for every meal? What if we focus on decreasing dietary restrictions, incorporating a variety of nourishing foods, and educating our patients, instead of on portion control and moderation?

This is how I choose to incorporate plant-based diets into my practice to treat and prevent these chronic inflammatory conditions and promote sustainable, realistic change in my clients’ health.

Brandy Winfree Root, a renal dietitian in private practice in Mary Esther, Florida, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Research pooled from nearly 100 studies has indicated that people who adhere to a vegan diet (ie, completely devoid of animal products) or a vegetarian diet (ie, devoid of meat, but may include dairy and eggs) are able to ward off some chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, optimize glycemic control, and decrease their risk for cancer compared with those who consume omnivorous diets.

Vegan and vegetarian diets, or flexitarian diets — which are less reliant on animal protein than the standard US diet but do not completely exclude meat, fish, eggs, or dairy — may promote homeostasis and decrease inflammation by providing more fiber, antioxidants, and unsaturated fatty acids than the typical Western diet.

Inflammation and Obesity

Adipose tissue is a major producer of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-6, whose presence then triggers a rush of acute-phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) by the liver. This process develops into chronic low-grade inflammation that can increase a person’s chances of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and related complications.

Adopting a plant-based diet can improve markers of chronic low-grade inflammation that can lead to chronic disease and worsen existent chronic disease. A meta-analysis of 29 studies encompassing nearly 2700 participants found that initiation of a plant-based diet showed significant improvement in CRP, IL-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1.

If we want to prevent these inflammatory disease states and their complications, the obvious response is to counsel patients to avoid excessive weight gain or to lose weight if obesity is their baseline. This can be tough for some patients, but it is nonetheless an important step in chronic disease prevention and management.

Plant-Based Diet for Type 2 Diabetes

According to a review of nine studies of patients living with type 2 diabetes who adhered to a plant-based diet, all but one found that this approach led to significantly lower A1c values than those seen in control groups. Six of the included studies reported that participants were able to decrease or discontinue medications for the management of diabetes. Researchers across all included studies also noted a decrease in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, as well as increased weight loss in participants in each intervention group.

Such improvements are probably the result of the increase in fiber intake that occurs with a plant-based diet. A high-fiber diet is known to promote improved glucose and lipid metabolism as well as weight loss.

It is also worth noting that participants in the intervention groups also experienced improvements in depression and less chronic pain than did those in the control groups.

Plant-Based Diet for Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Although the use of a plant-based diet in the prevention of CKD is well documented, adopting such diets for the treatment of CKD may intimidate both patients and practitioners owing to the high potassium and phosphorus content of many fruits and vegetables.

However, research indicates that the bioavailability of both potassium and phosphorus is lower in plant-based, whole foods than in preservatives and the highly processed food items that incorporate them. This makes a plant-based diet more viable than previously thought.

Diets rich in vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and legumes have been shown to decrease dietary acid load, both preventing and treating metabolic acidosis. Such diets have also been shown to decrease blood pressure and the risk for a decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate. This type of diet would also prioritize the unsaturated fatty acids and fiber-rich proteins such as avocados, beans, and nuts shown to improve dyslipidemia, which may occur alongside CKD.

Realistic Options for Patients on Medical Diets

There is one question that I always seem to get from when recommending a plant-based diet: “These patients already have so many restrictions. Why would you add more?” And my answer is also always the same: I don’t.

I rarely, if ever, recommend completely cutting out any food item or food group. Instead, I ask the patient to increase their intake of plant-based foods and only limit highly processed foods and fatty meats. By shifting a patient’s focus to beans; nuts; and low-carbohydrate, high-fiber fruits and vegetables, I am often opening up a whole new world of possibilities.

Instead of a sandwich with low-sodium turkey and cheese on white bread with a side of unsalted pretzels, I recommend a caprese salad with blueberries and almonds or a Southwest salad with black beans, corn, and avocado. I don’t encourage my patients to skip the foods that they love, but instead to only think about all the delicious plant-based options that will provide them with more than just calories.

Meat, dairy, seafood, and eggs can certainly be a part of a healthy diet, but what if our chronically ill patients, especially those with diabetes, had more options than just grilled chicken and green beans for every meal? What if we focus on decreasing dietary restrictions, incorporating a variety of nourishing foods, and educating our patients, instead of on portion control and moderation?

This is how I choose to incorporate plant-based diets into my practice to treat and prevent these chronic inflammatory conditions and promote sustainable, realistic change in my clients’ health.

Brandy Winfree Root, a renal dietitian in private practice in Mary Esther, Florida, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Game We Play Every Day

Words do have power. Names have power. Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer ... They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it. — Ursula K. Le Guin

Every medical student should have a class in linguistics. I’m just unsure what it might replace. Maybe physiology? (When was the last time you used Fick’s or Fourier’s Laws anyway?). Even if we don’t supplant any core curriculum, it’s worth noting that we spend more time in our daily work calculating how to communicate things than calculating cardiac outputs. That we can convey so much so consistently and without specific training is a marvel. Making the diagnosis or a plan is often the easy part.

Linguistics is a broad field. At its essence, it studies how we communicate. It’s fascinating how we use tone, word choice, gestures, syntax, and grammar to explain, reassure, instruct or implore patients. Medical appointments are sometimes high stakes and occur within a huge variety of circumstances. In a single day of clinic, I had a patient with dementia, and one pursuing a PhD in P-Chem. I had English speakers, second language English speakers, and a Vietnamese patient who knew no English. In just one day, I explained things to toddlers and adults, a Black woman from Oklahoma and a Jewish woman from New York. For a brief few minutes, each of them was my partner in a game of medical charades. For each one, I had to figure out how to get them to know what I’m thinking.

I learned of this game of charades concept from a podcast featuring Morten Christiansen, professor of psychology at Cornell University, and professor in Cognitive Science of Language, at Aarhus University, Denmark. The idea is that language can be thought of as a game where speakers constantly improvise based on the topic, each one’s expertise, and the shared understanding. I found this intriguing. In his explanation, grammar and definitions are less important than the mutual understanding of what is being communicated. It helps explain the wide variations of speech even among those speaking the same language. It also flips the idea that brains are designed for language, a concept proposed by linguistic greats such as Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker. Rather, what we call language is just the best solution our brains could create to convey information.

I thought about how each of us instinctively varies the complexity of sentences and tone of voice based on the ability of each patient to understand. Gestures, storytelling and analogies are linguistic tools we use without thinking about them. We’ve a unique communications conundrum in that we often need patients to understand a complex idea, but only have minutes to get them there. We don’t want them to panic. We also don’t want them to be so dispassionate as to not act. To speed things up, we often use a technique known as chunking, short phrases that capture an idea in one bite. For example, “soak and smear” to get atopic patients to moisturize or “scrape and burn” to describe a curettage and electrodesiccation of a basal cell carcinoma or “a stick and a burn” before injecting them (I never liked that one). These are pithy, efficient. But they don’t always work.

One afternoon I had a 93-year-old woman with glossodynia. She had dementia and her 96-year-old husband was helping. When I explained how she’d “swish and spit” her magic mouthwash, he looked perplexed. Is she swishing a wand or something? I shook my head, “No” and gestured with my hands palms down, waving back and forth. It is just a mouthwash. She should rinse, then spit it out. I lost that round.

Then a 64-year-old woman whom I had to advise that the pink bump on her arm was a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor. Do I call it a Merkel cell carcinoma? Do I say, “You know, like the one Jimmy Buffett had?” (Nope, not a good use of storytelling). She wanted to know how she got it. Sun exposure, we think. Or, perhaps a virus. Just how does one explain a virus called MCPyV that is ubiquitous but somehow caused cancer just for you? How do you convey, “This is serious, but you might not die like Jimmy Buffett?” I had to use all my language skills to get this right.

Then there is the Henderson-Hasselbalch problem of linguistics: communicating through a translator. When doing so, I’m cognizant of choosing short, simple sentences. Subject, verb, object. First this, then that. This mitigates what’s lost in translation and reduces waiting for translations (especially when your patient is storytelling in paragraphs). But try doing this with an emotionally wrought condition like alopecia. Finding the fewest words to convey that your FSH and estrogen levels are irrelevant to your telogen effluvium to a Vietnamese speaker is tricky. “Yes, I see your primary care physician ordered these tests. No, the numbers do not matter.” Did that translate as they are normal? Or that they don’t matter because she is 54? Or that they don’t matter to me because I didn’t order them?

When you find yourself exhausted at the day’s end, perhaps you’ll better appreciate how it was not only the graduate level medicine you did today; you’ve practically got a PhD in linguistics as well. You just didn’t realize it.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Words do have power. Names have power. Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer ... They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it. — Ursula K. Le Guin

Every medical student should have a class in linguistics. I’m just unsure what it might replace. Maybe physiology? (When was the last time you used Fick’s or Fourier’s Laws anyway?). Even if we don’t supplant any core curriculum, it’s worth noting that we spend more time in our daily work calculating how to communicate things than calculating cardiac outputs. That we can convey so much so consistently and without specific training is a marvel. Making the diagnosis or a plan is often the easy part.

Linguistics is a broad field. At its essence, it studies how we communicate. It’s fascinating how we use tone, word choice, gestures, syntax, and grammar to explain, reassure, instruct or implore patients. Medical appointments are sometimes high stakes and occur within a huge variety of circumstances. In a single day of clinic, I had a patient with dementia, and one pursuing a PhD in P-Chem. I had English speakers, second language English speakers, and a Vietnamese patient who knew no English. In just one day, I explained things to toddlers and adults, a Black woman from Oklahoma and a Jewish woman from New York. For a brief few minutes, each of them was my partner in a game of medical charades. For each one, I had to figure out how to get them to know what I’m thinking.

I learned of this game of charades concept from a podcast featuring Morten Christiansen, professor of psychology at Cornell University, and professor in Cognitive Science of Language, at Aarhus University, Denmark. The idea is that language can be thought of as a game where speakers constantly improvise based on the topic, each one’s expertise, and the shared understanding. I found this intriguing. In his explanation, grammar and definitions are less important than the mutual understanding of what is being communicated. It helps explain the wide variations of speech even among those speaking the same language. It also flips the idea that brains are designed for language, a concept proposed by linguistic greats such as Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker. Rather, what we call language is just the best solution our brains could create to convey information.

I thought about how each of us instinctively varies the complexity of sentences and tone of voice based on the ability of each patient to understand. Gestures, storytelling and analogies are linguistic tools we use without thinking about them. We’ve a unique communications conundrum in that we often need patients to understand a complex idea, but only have minutes to get them there. We don’t want them to panic. We also don’t want them to be so dispassionate as to not act. To speed things up, we often use a technique known as chunking, short phrases that capture an idea in one bite. For example, “soak and smear” to get atopic patients to moisturize or “scrape and burn” to describe a curettage and electrodesiccation of a basal cell carcinoma or “a stick and a burn” before injecting them (I never liked that one). These are pithy, efficient. But they don’t always work.

One afternoon I had a 93-year-old woman with glossodynia. She had dementia and her 96-year-old husband was helping. When I explained how she’d “swish and spit” her magic mouthwash, he looked perplexed. Is she swishing a wand or something? I shook my head, “No” and gestured with my hands palms down, waving back and forth. It is just a mouthwash. She should rinse, then spit it out. I lost that round.

Then a 64-year-old woman whom I had to advise that the pink bump on her arm was a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor. Do I call it a Merkel cell carcinoma? Do I say, “You know, like the one Jimmy Buffett had?” (Nope, not a good use of storytelling). She wanted to know how she got it. Sun exposure, we think. Or, perhaps a virus. Just how does one explain a virus called MCPyV that is ubiquitous but somehow caused cancer just for you? How do you convey, “This is serious, but you might not die like Jimmy Buffett?” I had to use all my language skills to get this right.

Then there is the Henderson-Hasselbalch problem of linguistics: communicating through a translator. When doing so, I’m cognizant of choosing short, simple sentences. Subject, verb, object. First this, then that. This mitigates what’s lost in translation and reduces waiting for translations (especially when your patient is storytelling in paragraphs). But try doing this with an emotionally wrought condition like alopecia. Finding the fewest words to convey that your FSH and estrogen levels are irrelevant to your telogen effluvium to a Vietnamese speaker is tricky. “Yes, I see your primary care physician ordered these tests. No, the numbers do not matter.” Did that translate as they are normal? Or that they don’t matter because she is 54? Or that they don’t matter to me because I didn’t order them?

When you find yourself exhausted at the day’s end, perhaps you’ll better appreciate how it was not only the graduate level medicine you did today; you’ve practically got a PhD in linguistics as well. You just didn’t realize it.