User login

Is It Possible To Treat Patients You Dislike?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

What do we do if we don’t like patients? We take the Hippocratic Oath as young students in Glasgow. We do that just before our graduation ceremony; we hold our hands up and repeat the Hippocratic Oath: “First, do no harm,” and so on.

I was thinking back over a long career. I’ve been a cancer doctor for 40 years and I quite like saying that.

I can only think genuinely over a couple of times in which I’ve acted reflexively when a patient has done something awful. The couple of times it happened, it was just terrible racist comments to junior doctors who were with me. Extraordinarily dreadful things such as, “I don’t want to be touched by ...” or something of that sort.

Without really thinking about it, you react as a normal citizen and say, “That’s absolutely awful. Apologize immediately or leave the consultation room, and never ever come back again.”

I remember that it happened once in Glasgow and once when I was a young professor in Birmingham, and it’s just an automatic gut reaction. The patient got a fright, and I immediately apologized and groveled around. In that relationship, we hold all the power, don’t we? Rather than being gentle about it, I was genuinely angry because of these ridiculous comments.

Otherwise, I think most of the doctor-patient relationships are predicated on nonromantic love. I think patients want us to love them as one would a son, mother, father, or daughter, because if we do, then we will do better for them and we’ll pull out all the stops. “Placebo” means “I will please.” I think in the vast majority of cases, at least in our National Health Service (NHS), patients come with trust and a sense of wanting to build that relationship. That may be changing, but not for me.

What about putting the boot on the other foot? What if the patients don’t like us rather than vice versa? As part of our accreditation appraisal process, from time to time we have to take patient surveys as to whether the patients felt that, after they had been seen in a consultation, they were treated with dignity, the quality of information given was appropriate, and they were treated with kindness.

It’s an excellent exercise. Without bragging about it, patients objectively, according to these measures, appreciate the service that I give. It’s like getting five-star reviews on Trustpilot, or whatever these things are, that allow you to review car salesmen and so on. I have always had five-star reviews across the board.

That, again, I thought was just a feature of that relationship, of patients wanting to please. These are patients who had been treated, who were in the outpatient department, who were in the midst of battle. Still, the scores are very high. I speak to my colleagues and that’s not uniformly the case. Patients actually do use these feedback forms, I think in a positive rather than negative way, reflecting back on the way that they were treated.

It has caused some of my colleagues to think quite hard about their personal style and approach to patients. That sense of feedback is important.

What about losing trust? If that’s at the heart of everything that we do, then what would be an objective measure of losing trust? Again, in our healthcare system, it has been exceedingly unusual for a patient to request a second opinion. Now, that’s changing. The government is trying to change it. Leaders of the NHS are trying to change it so that patients feel assured that they can seek second opinions.

Again, in all the years I’ve been a cancer doctor, it has been incredibly infrequent that somebody has sought a second opinion after I’ve said something. That may be a measure of trust. Again, I’ve lived through an NHS in which seeking second opinions was something of a rarity.

I’d be really interested to see what you think. In your own sphere of healthcare practice, is it possible for us to look after patients that we don’t like, or should we be honest and say, “I don’t like you. Our relationship has broken down. I want you to be seen by a colleague,” or “I want you to be nursed by somebody else”?

Has that happened? Is that something that you think is common or may become more common? What about when trust breaks down the other way? Can you think of instances in which the relationship, for whatever reason, just didn’t work and the patient had to move on because of that loss of trust and what underpinned it? I’d be really interested to know.

I seek to be informed rather than the other way around. Can we truly look after patients that we don’t like or can we rise above it as Hippocrates might have done?

Thanks for listening, as always. For the time being, over and out.

Dr. Kerr, Professor, Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Science, University of Oxford; Professor of Cancer Medicine, Oxford Cancer Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom, disclosed ties with Celleron Therapeutics, Oxford Cancer Biomarkers, Afrox, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Genomic Health, Merck Serono, and Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

What do we do if we don’t like patients? We take the Hippocratic Oath as young students in Glasgow. We do that just before our graduation ceremony; we hold our hands up and repeat the Hippocratic Oath: “First, do no harm,” and so on.

I was thinking back over a long career. I’ve been a cancer doctor for 40 years and I quite like saying that.

I can only think genuinely over a couple of times in which I’ve acted reflexively when a patient has done something awful. The couple of times it happened, it was just terrible racist comments to junior doctors who were with me. Extraordinarily dreadful things such as, “I don’t want to be touched by ...” or something of that sort.

Without really thinking about it, you react as a normal citizen and say, “That’s absolutely awful. Apologize immediately or leave the consultation room, and never ever come back again.”

I remember that it happened once in Glasgow and once when I was a young professor in Birmingham, and it’s just an automatic gut reaction. The patient got a fright, and I immediately apologized and groveled around. In that relationship, we hold all the power, don’t we? Rather than being gentle about it, I was genuinely angry because of these ridiculous comments.

Otherwise, I think most of the doctor-patient relationships are predicated on nonromantic love. I think patients want us to love them as one would a son, mother, father, or daughter, because if we do, then we will do better for them and we’ll pull out all the stops. “Placebo” means “I will please.” I think in the vast majority of cases, at least in our National Health Service (NHS), patients come with trust and a sense of wanting to build that relationship. That may be changing, but not for me.

What about putting the boot on the other foot? What if the patients don’t like us rather than vice versa? As part of our accreditation appraisal process, from time to time we have to take patient surveys as to whether the patients felt that, after they had been seen in a consultation, they were treated with dignity, the quality of information given was appropriate, and they were treated with kindness.

It’s an excellent exercise. Without bragging about it, patients objectively, according to these measures, appreciate the service that I give. It’s like getting five-star reviews on Trustpilot, or whatever these things are, that allow you to review car salesmen and so on. I have always had five-star reviews across the board.

That, again, I thought was just a feature of that relationship, of patients wanting to please. These are patients who had been treated, who were in the outpatient department, who were in the midst of battle. Still, the scores are very high. I speak to my colleagues and that’s not uniformly the case. Patients actually do use these feedback forms, I think in a positive rather than negative way, reflecting back on the way that they were treated.

It has caused some of my colleagues to think quite hard about their personal style and approach to patients. That sense of feedback is important.

What about losing trust? If that’s at the heart of everything that we do, then what would be an objective measure of losing trust? Again, in our healthcare system, it has been exceedingly unusual for a patient to request a second opinion. Now, that’s changing. The government is trying to change it. Leaders of the NHS are trying to change it so that patients feel assured that they can seek second opinions.

Again, in all the years I’ve been a cancer doctor, it has been incredibly infrequent that somebody has sought a second opinion after I’ve said something. That may be a measure of trust. Again, I’ve lived through an NHS in which seeking second opinions was something of a rarity.

I’d be really interested to see what you think. In your own sphere of healthcare practice, is it possible for us to look after patients that we don’t like, or should we be honest and say, “I don’t like you. Our relationship has broken down. I want you to be seen by a colleague,” or “I want you to be nursed by somebody else”?

Has that happened? Is that something that you think is common or may become more common? What about when trust breaks down the other way? Can you think of instances in which the relationship, for whatever reason, just didn’t work and the patient had to move on because of that loss of trust and what underpinned it? I’d be really interested to know.

I seek to be informed rather than the other way around. Can we truly look after patients that we don’t like or can we rise above it as Hippocrates might have done?

Thanks for listening, as always. For the time being, over and out.

Dr. Kerr, Professor, Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Science, University of Oxford; Professor of Cancer Medicine, Oxford Cancer Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom, disclosed ties with Celleron Therapeutics, Oxford Cancer Biomarkers, Afrox, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Genomic Health, Merck Serono, and Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

What do we do if we don’t like patients? We take the Hippocratic Oath as young students in Glasgow. We do that just before our graduation ceremony; we hold our hands up and repeat the Hippocratic Oath: “First, do no harm,” and so on.

I was thinking back over a long career. I’ve been a cancer doctor for 40 years and I quite like saying that.

I can only think genuinely over a couple of times in which I’ve acted reflexively when a patient has done something awful. The couple of times it happened, it was just terrible racist comments to junior doctors who were with me. Extraordinarily dreadful things such as, “I don’t want to be touched by ...” or something of that sort.

Without really thinking about it, you react as a normal citizen and say, “That’s absolutely awful. Apologize immediately or leave the consultation room, and never ever come back again.”

I remember that it happened once in Glasgow and once when I was a young professor in Birmingham, and it’s just an automatic gut reaction. The patient got a fright, and I immediately apologized and groveled around. In that relationship, we hold all the power, don’t we? Rather than being gentle about it, I was genuinely angry because of these ridiculous comments.

Otherwise, I think most of the doctor-patient relationships are predicated on nonromantic love. I think patients want us to love them as one would a son, mother, father, or daughter, because if we do, then we will do better for them and we’ll pull out all the stops. “Placebo” means “I will please.” I think in the vast majority of cases, at least in our National Health Service (NHS), patients come with trust and a sense of wanting to build that relationship. That may be changing, but not for me.

What about putting the boot on the other foot? What if the patients don’t like us rather than vice versa? As part of our accreditation appraisal process, from time to time we have to take patient surveys as to whether the patients felt that, after they had been seen in a consultation, they were treated with dignity, the quality of information given was appropriate, and they were treated with kindness.

It’s an excellent exercise. Without bragging about it, patients objectively, according to these measures, appreciate the service that I give. It’s like getting five-star reviews on Trustpilot, or whatever these things are, that allow you to review car salesmen and so on. I have always had five-star reviews across the board.

That, again, I thought was just a feature of that relationship, of patients wanting to please. These are patients who had been treated, who were in the outpatient department, who were in the midst of battle. Still, the scores are very high. I speak to my colleagues and that’s not uniformly the case. Patients actually do use these feedback forms, I think in a positive rather than negative way, reflecting back on the way that they were treated.

It has caused some of my colleagues to think quite hard about their personal style and approach to patients. That sense of feedback is important.

What about losing trust? If that’s at the heart of everything that we do, then what would be an objective measure of losing trust? Again, in our healthcare system, it has been exceedingly unusual for a patient to request a second opinion. Now, that’s changing. The government is trying to change it. Leaders of the NHS are trying to change it so that patients feel assured that they can seek second opinions.

Again, in all the years I’ve been a cancer doctor, it has been incredibly infrequent that somebody has sought a second opinion after I’ve said something. That may be a measure of trust. Again, I’ve lived through an NHS in which seeking second opinions was something of a rarity.

I’d be really interested to see what you think. In your own sphere of healthcare practice, is it possible for us to look after patients that we don’t like, or should we be honest and say, “I don’t like you. Our relationship has broken down. I want you to be seen by a colleague,” or “I want you to be nursed by somebody else”?

Has that happened? Is that something that you think is common or may become more common? What about when trust breaks down the other way? Can you think of instances in which the relationship, for whatever reason, just didn’t work and the patient had to move on because of that loss of trust and what underpinned it? I’d be really interested to know.

I seek to be informed rather than the other way around. Can we truly look after patients that we don’t like or can we rise above it as Hippocrates might have done?

Thanks for listening, as always. For the time being, over and out.

Dr. Kerr, Professor, Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Science, University of Oxford; Professor of Cancer Medicine, Oxford Cancer Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom, disclosed ties with Celleron Therapeutics, Oxford Cancer Biomarkers, Afrox, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Genomic Health, Merck Serono, and Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ultraprocessed Foods and CVD: Myths vs Facts

I’d like to talk with you about ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and try to separate some of the facts from the myths. I’d like to discuss a recent report in The Lancet Regional Health that looks at this topic comprehensively and in detail.

This report includes three large-scale prospective cohort studies of US female and male health professionals, more than 200,000 participants in total. It also includes a meta-analysis of 22 international cohorts with about 1.2 million participants. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m a co-author of this study.

What are UPFs, and why are they important? Why do we care, and what are the knowledge gaps? UPFs are generally packaged foods that contain ingredients to extend shelf life and improve taste and palatability. It’s important because 60%-70% of the US diet, if not more, is made up of UPFs. So, the relationship between UPFs and CVD and other health outcomes is actually very important.

And the research to date on this subject has been quite limited.

In other studies, these UPFs have been linked to weight gain and dyslipidemia; some tissue glycation has been found, and some changes in the microbiome. Some studies have linked higher UPF intake with type 2 diabetes. A few have looked at certain selected UPF foods and found a higher risk for CVD, but a really comprehensive look at this question hasn’t been done.

So, that’s what we did in this paper and in the meta-analysis with the 22 cohorts, and we saw a very clear and distinct significant increase in coronary heart disease by 23%, total CVD by 17%, and stroke by 9% when comparing the highest vs the lowest category [of UPF intake]. When we drilled down deeply into the types of UPFs in the US health professional cohorts, we saw that there were some major differences in the relationship with CVD depending on the type of UPF.

In comparing the highest quintile vs the lowest quintile [of total UPF intake], we saw that some of the UPFs were associated with significant elevations in risk for CVD. These included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats. But some UPFs were linked with a lower risk for CVD. These included breakfast cereals, yogurt, some dairy desserts, and whole grains.

Overall, it seemed that UPFs are actually quite diverse in their association with health. It’s not one size fits all. They’re not all created equal, and some of these differences matter. Although overall we would recommend that our diets be focused on whole foods, primarily plant based, lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and other whole foods, it seems from this report and the meta-analysis that certain types of UPFs can be incorporated into a healthy diet and don’t need to be avoided entirely.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She reported receiving donations and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and try to separate some of the facts from the myths. I’d like to discuss a recent report in The Lancet Regional Health that looks at this topic comprehensively and in detail.

This report includes three large-scale prospective cohort studies of US female and male health professionals, more than 200,000 participants in total. It also includes a meta-analysis of 22 international cohorts with about 1.2 million participants. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m a co-author of this study.

What are UPFs, and why are they important? Why do we care, and what are the knowledge gaps? UPFs are generally packaged foods that contain ingredients to extend shelf life and improve taste and palatability. It’s important because 60%-70% of the US diet, if not more, is made up of UPFs. So, the relationship between UPFs and CVD and other health outcomes is actually very important.

And the research to date on this subject has been quite limited.

In other studies, these UPFs have been linked to weight gain and dyslipidemia; some tissue glycation has been found, and some changes in the microbiome. Some studies have linked higher UPF intake with type 2 diabetes. A few have looked at certain selected UPF foods and found a higher risk for CVD, but a really comprehensive look at this question hasn’t been done.

So, that’s what we did in this paper and in the meta-analysis with the 22 cohorts, and we saw a very clear and distinct significant increase in coronary heart disease by 23%, total CVD by 17%, and stroke by 9% when comparing the highest vs the lowest category [of UPF intake]. When we drilled down deeply into the types of UPFs in the US health professional cohorts, we saw that there were some major differences in the relationship with CVD depending on the type of UPF.

In comparing the highest quintile vs the lowest quintile [of total UPF intake], we saw that some of the UPFs were associated with significant elevations in risk for CVD. These included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats. But some UPFs were linked with a lower risk for CVD. These included breakfast cereals, yogurt, some dairy desserts, and whole grains.

Overall, it seemed that UPFs are actually quite diverse in their association with health. It’s not one size fits all. They’re not all created equal, and some of these differences matter. Although overall we would recommend that our diets be focused on whole foods, primarily plant based, lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and other whole foods, it seems from this report and the meta-analysis that certain types of UPFs can be incorporated into a healthy diet and don’t need to be avoided entirely.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She reported receiving donations and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and try to separate some of the facts from the myths. I’d like to discuss a recent report in The Lancet Regional Health that looks at this topic comprehensively and in detail.

This report includes three large-scale prospective cohort studies of US female and male health professionals, more than 200,000 participants in total. It also includes a meta-analysis of 22 international cohorts with about 1.2 million participants. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m a co-author of this study.

What are UPFs, and why are they important? Why do we care, and what are the knowledge gaps? UPFs are generally packaged foods that contain ingredients to extend shelf life and improve taste and palatability. It’s important because 60%-70% of the US diet, if not more, is made up of UPFs. So, the relationship between UPFs and CVD and other health outcomes is actually very important.

And the research to date on this subject has been quite limited.

In other studies, these UPFs have been linked to weight gain and dyslipidemia; some tissue glycation has been found, and some changes in the microbiome. Some studies have linked higher UPF intake with type 2 diabetes. A few have looked at certain selected UPF foods and found a higher risk for CVD, but a really comprehensive look at this question hasn’t been done.

So, that’s what we did in this paper and in the meta-analysis with the 22 cohorts, and we saw a very clear and distinct significant increase in coronary heart disease by 23%, total CVD by 17%, and stroke by 9% when comparing the highest vs the lowest category [of UPF intake]. When we drilled down deeply into the types of UPFs in the US health professional cohorts, we saw that there were some major differences in the relationship with CVD depending on the type of UPF.

In comparing the highest quintile vs the lowest quintile [of total UPF intake], we saw that some of the UPFs were associated with significant elevations in risk for CVD. These included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats. But some UPFs were linked with a lower risk for CVD. These included breakfast cereals, yogurt, some dairy desserts, and whole grains.

Overall, it seemed that UPFs are actually quite diverse in their association with health. It’s not one size fits all. They’re not all created equal, and some of these differences matter. Although overall we would recommend that our diets be focused on whole foods, primarily plant based, lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and other whole foods, it seems from this report and the meta-analysis that certain types of UPFs can be incorporated into a healthy diet and don’t need to be avoided entirely.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She reported receiving donations and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The New Cancer Stats Might Look Like a Death Sentence. They Aren’t.

Cancer is becoming more common in younger generations. Data show that people under 50 are experiencing higher rates of cancer than any generation before them. As a genetic counselor, I hoped these upward trends in early-onset malignancies would slow with a better understanding of risk factors and prevention strategies. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. Recent findings from the American Cancer Society reveal that the incidence of at least 17 of 34 cancer types is rising among GenX and Millennials.

These statistics are alarming. I appreciate how easy it is for patients to get lost in the headlines about cancer, which may shape how they approach their healthcare. Each year, millions of Americans miss critical cancer screenings, with many citing fear of a positive test result as a leading reason. Others believe, despite the statistics, that cancer is not something they need to worry about until they are older. And then, of course, getting screened is not as easy as it should be.

In my work, I meet with people from both younger and older generations who have either faced cancer themselves or witnessed a loved one experience the disease. One of the most common sentiments I hear from these patients is the desire to catch cancer earlier. My answer is always this: The first and most important step everyone can take is understanding their risk.

For some, knowing they are at increased risk for cancer means starting screenings earlier — sometimes as early as age 25 — or getting screened with a more sensitive test.

This proactive approach is the right one. It also significantly reduces the burden of total and cancer-specific healthcare costs. While screening may carry some potential risks, clinicians can minimize these risks by adhering to evidence-based guidelines, such as those from the American Cancer Society, and ensuring there is appropriate discussion of treatment options when a diagnosis is made.

Normalizing Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

A detailed cancer risk assessment and education about signs and symptoms should be part of every preventive care visit, regardless of someone’s age. Further, that cancer risk assessment should lead to clear recommendations and support for taking the next steps.

This is where care advocacy and patient navigation come in. Care advocacy can improve outcomes at every stage of the cancer journey, from increasing screening rates to improving quality of life for survivors. I’ve seen first-hand how care advocates help patients overcome hurdles like long wait times for appointments they need, making both screening and diagnostic care easier to access.

Now, with the finalization of a new rule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, providers can bill for oncology navigation services that occur under their supervision. This formal recognition of care navigation affirms the value of these services not just clinically but financially as well. It will be through methods like care navigation, targeted outreach, and engaging educational resources — built into and covered by health plans — that patients will feel more in control over their health and have tools to help minimize the effects of cancer on the rest of their lives.

These services benefit healthcare providers as well. Care navigation supports clinical care teams, from primary care providers to oncologists, by ensuring patients are seen before their cancer progresses to a more advanced stage. And even if patients follow screening recommendations for the rest of their lives and never get a positive result, they’ve still gained something invaluable: peace of mind, knowing they’ve taken an active role in their health.

Fighting Fear With Routine

Treating cancer as a normal part of young people’s healthcare means helping them envision the disease as a condition that can be treated, much like a diagnosis of diabetes or high cholesterol. This mindset shift means quickly following up on a concerning symptom or screening result and reducing the time to start treatment if needed. And with treatment options and success rates for some cancers being better than ever, survivorship support must be built into every treatment plan from the start. Before treatment begins, healthcare providers should make time to talk about sometimes-overlooked key topics, such as reproductive options for people whose fertility may be affected by their cancer treatment, about plans for returning to work during or after treatment, and finding the right mental health support.

Where we can’t prevent cancer, both primary care providers and oncologists can work together to help patients receive the right diagnosis and treatment as quickly as possible. Knowing insurance coverage has a direct effect on how early cancer is caught, for example, younger people need support in understanding and accessing benefits and resources that may be available through their existing healthcare channels, like some employer-sponsored health plans. Even if getting treated for cancer is inevitable for some, taking immediate action to get screened when it’s appropriate is the best thing we can do to lessen the impact of these rising cancer incidences across the country. At the end of the day, being afraid of cancer doesn’t decrease the chances of getting sick or dying from it. Proactive screening and early detection do.

Brockman, Genetic Counselor, Color Health, Buffalo, New York, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer is becoming more common in younger generations. Data show that people under 50 are experiencing higher rates of cancer than any generation before them. As a genetic counselor, I hoped these upward trends in early-onset malignancies would slow with a better understanding of risk factors and prevention strategies. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. Recent findings from the American Cancer Society reveal that the incidence of at least 17 of 34 cancer types is rising among GenX and Millennials.

These statistics are alarming. I appreciate how easy it is for patients to get lost in the headlines about cancer, which may shape how they approach their healthcare. Each year, millions of Americans miss critical cancer screenings, with many citing fear of a positive test result as a leading reason. Others believe, despite the statistics, that cancer is not something they need to worry about until they are older. And then, of course, getting screened is not as easy as it should be.

In my work, I meet with people from both younger and older generations who have either faced cancer themselves or witnessed a loved one experience the disease. One of the most common sentiments I hear from these patients is the desire to catch cancer earlier. My answer is always this: The first and most important step everyone can take is understanding their risk.

For some, knowing they are at increased risk for cancer means starting screenings earlier — sometimes as early as age 25 — or getting screened with a more sensitive test.

This proactive approach is the right one. It also significantly reduces the burden of total and cancer-specific healthcare costs. While screening may carry some potential risks, clinicians can minimize these risks by adhering to evidence-based guidelines, such as those from the American Cancer Society, and ensuring there is appropriate discussion of treatment options when a diagnosis is made.

Normalizing Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

A detailed cancer risk assessment and education about signs and symptoms should be part of every preventive care visit, regardless of someone’s age. Further, that cancer risk assessment should lead to clear recommendations and support for taking the next steps.

This is where care advocacy and patient navigation come in. Care advocacy can improve outcomes at every stage of the cancer journey, from increasing screening rates to improving quality of life for survivors. I’ve seen first-hand how care advocates help patients overcome hurdles like long wait times for appointments they need, making both screening and diagnostic care easier to access.

Now, with the finalization of a new rule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, providers can bill for oncology navigation services that occur under their supervision. This formal recognition of care navigation affirms the value of these services not just clinically but financially as well. It will be through methods like care navigation, targeted outreach, and engaging educational resources — built into and covered by health plans — that patients will feel more in control over their health and have tools to help minimize the effects of cancer on the rest of their lives.

These services benefit healthcare providers as well. Care navigation supports clinical care teams, from primary care providers to oncologists, by ensuring patients are seen before their cancer progresses to a more advanced stage. And even if patients follow screening recommendations for the rest of their lives and never get a positive result, they’ve still gained something invaluable: peace of mind, knowing they’ve taken an active role in their health.

Fighting Fear With Routine

Treating cancer as a normal part of young people’s healthcare means helping them envision the disease as a condition that can be treated, much like a diagnosis of diabetes or high cholesterol. This mindset shift means quickly following up on a concerning symptom or screening result and reducing the time to start treatment if needed. And with treatment options and success rates for some cancers being better than ever, survivorship support must be built into every treatment plan from the start. Before treatment begins, healthcare providers should make time to talk about sometimes-overlooked key topics, such as reproductive options for people whose fertility may be affected by their cancer treatment, about plans for returning to work during or after treatment, and finding the right mental health support.

Where we can’t prevent cancer, both primary care providers and oncologists can work together to help patients receive the right diagnosis and treatment as quickly as possible. Knowing insurance coverage has a direct effect on how early cancer is caught, for example, younger people need support in understanding and accessing benefits and resources that may be available through their existing healthcare channels, like some employer-sponsored health plans. Even if getting treated for cancer is inevitable for some, taking immediate action to get screened when it’s appropriate is the best thing we can do to lessen the impact of these rising cancer incidences across the country. At the end of the day, being afraid of cancer doesn’t decrease the chances of getting sick or dying from it. Proactive screening and early detection do.

Brockman, Genetic Counselor, Color Health, Buffalo, New York, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer is becoming more common in younger generations. Data show that people under 50 are experiencing higher rates of cancer than any generation before them. As a genetic counselor, I hoped these upward trends in early-onset malignancies would slow with a better understanding of risk factors and prevention strategies. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. Recent findings from the American Cancer Society reveal that the incidence of at least 17 of 34 cancer types is rising among GenX and Millennials.

These statistics are alarming. I appreciate how easy it is for patients to get lost in the headlines about cancer, which may shape how they approach their healthcare. Each year, millions of Americans miss critical cancer screenings, with many citing fear of a positive test result as a leading reason. Others believe, despite the statistics, that cancer is not something they need to worry about until they are older. And then, of course, getting screened is not as easy as it should be.

In my work, I meet with people from both younger and older generations who have either faced cancer themselves or witnessed a loved one experience the disease. One of the most common sentiments I hear from these patients is the desire to catch cancer earlier. My answer is always this: The first and most important step everyone can take is understanding their risk.

For some, knowing they are at increased risk for cancer means starting screenings earlier — sometimes as early as age 25 — or getting screened with a more sensitive test.

This proactive approach is the right one. It also significantly reduces the burden of total and cancer-specific healthcare costs. While screening may carry some potential risks, clinicians can minimize these risks by adhering to evidence-based guidelines, such as those from the American Cancer Society, and ensuring there is appropriate discussion of treatment options when a diagnosis is made.

Normalizing Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

A detailed cancer risk assessment and education about signs and symptoms should be part of every preventive care visit, regardless of someone’s age. Further, that cancer risk assessment should lead to clear recommendations and support for taking the next steps.

This is where care advocacy and patient navigation come in. Care advocacy can improve outcomes at every stage of the cancer journey, from increasing screening rates to improving quality of life for survivors. I’ve seen first-hand how care advocates help patients overcome hurdles like long wait times for appointments they need, making both screening and diagnostic care easier to access.

Now, with the finalization of a new rule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, providers can bill for oncology navigation services that occur under their supervision. This formal recognition of care navigation affirms the value of these services not just clinically but financially as well. It will be through methods like care navigation, targeted outreach, and engaging educational resources — built into and covered by health plans — that patients will feel more in control over their health and have tools to help minimize the effects of cancer on the rest of their lives.

These services benefit healthcare providers as well. Care navigation supports clinical care teams, from primary care providers to oncologists, by ensuring patients are seen before their cancer progresses to a more advanced stage. And even if patients follow screening recommendations for the rest of their lives and never get a positive result, they’ve still gained something invaluable: peace of mind, knowing they’ve taken an active role in their health.

Fighting Fear With Routine

Treating cancer as a normal part of young people’s healthcare means helping them envision the disease as a condition that can be treated, much like a diagnosis of diabetes or high cholesterol. This mindset shift means quickly following up on a concerning symptom or screening result and reducing the time to start treatment if needed. And with treatment options and success rates for some cancers being better than ever, survivorship support must be built into every treatment plan from the start. Before treatment begins, healthcare providers should make time to talk about sometimes-overlooked key topics, such as reproductive options for people whose fertility may be affected by their cancer treatment, about plans for returning to work during or after treatment, and finding the right mental health support.

Where we can’t prevent cancer, both primary care providers and oncologists can work together to help patients receive the right diagnosis and treatment as quickly as possible. Knowing insurance coverage has a direct effect on how early cancer is caught, for example, younger people need support in understanding and accessing benefits and resources that may be available through their existing healthcare channels, like some employer-sponsored health plans. Even if getting treated for cancer is inevitable for some, taking immediate action to get screened when it’s appropriate is the best thing we can do to lessen the impact of these rising cancer incidences across the country. At the end of the day, being afraid of cancer doesn’t decrease the chances of getting sick or dying from it. Proactive screening and early detection do.

Brockman, Genetic Counselor, Color Health, Buffalo, New York, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Unseen Cost of Weight Loss and Aging: Tackling Sarcopenia

Losses of muscle and strength are inescapable effects of the aging process. Left unchecked, these progressive losses will start to impair physical function.

Once a certain level of impairment occurs, an individual can be diagnosed with sarcopenia, which comes from the Greek words “sarco” (flesh) and “penia” (poverty).

Muscle mass losses generally occur with weight loss, and the increasing use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) medications may lead to greater incidence and prevalence of sarcopenia in the years to come.

A recent meta-analysis of 56 studies (mean participant age, 50 years) found a twofold greater risk for mortality in those with sarcopenia vs those without. Despite its health consequences, sarcopenia tends to be underdiagnosed and, consequently, undertreated at a population and individual level. Part of the reason probably stems from the lack of health insurance reimbursement for individual clinicians and hospital systems to perform sarcopenia screening assessments.

In aging and obesity, it appears justified to include and emphasize a recommendation for sarcopenia screening in medical society guidelines; however, individual patients and clinicians do not need to wait for updated guidelines to implement sarcopenia screening, treatment, and prevention strategies in their own lives and/or clinical practice.

Simple Prevention and Treatment Strategy

Much can be done to help prevent sarcopenia. The primary strategy, unsurprisingly, is engaging in frequent strength training. But that doesn’t mean hours in the gym every week.

With just one session per week over 10 weeks, lean body mass (LBM), a common proxy for muscle mass, increased by 0.33 kg, according to a study which evaluated LBM improvements across different strength training frequencies. Adding a second weekly session was significantly better. In the twice-weekly group, LBM increased by 1.4 kg over 10 weeks, resulting in an increase in LBM more than four times greater than the once-a-week group. (There was no greater improvement in LBM by adding a third weekly session vs two weekly sessions.)

Although that particular study didn’t identify greater benefit at three times a week, compared with twice a week, the specific training routines and lack of a protein consumption assessment may have played a role in that finding.

Underlying the diminishing benefits, a different study found a marginally greater benefit in favor of performing ≥ five sets per major muscle group per week, compared with < five sets per week for increasing muscle in the legs, arms, back, chest, and shoulders.

Expensive gym memberships and fancy equipment are not necessary. While the use of strength training machines and free weights have been viewed by many as the optimal approach, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that comparable improvements to strength can be achieved with workouts using resistance bands. For those who struggle to find the time to go to a gym, or for whom gym fees are not financially affordable, resistance bands are a cheaper and more convenient alternative.

Lucas, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City, disclosed ties with Measured (Better Health Labs).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Losses of muscle and strength are inescapable effects of the aging process. Left unchecked, these progressive losses will start to impair physical function.

Once a certain level of impairment occurs, an individual can be diagnosed with sarcopenia, which comes from the Greek words “sarco” (flesh) and “penia” (poverty).

Muscle mass losses generally occur with weight loss, and the increasing use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) medications may lead to greater incidence and prevalence of sarcopenia in the years to come.

A recent meta-analysis of 56 studies (mean participant age, 50 years) found a twofold greater risk for mortality in those with sarcopenia vs those without. Despite its health consequences, sarcopenia tends to be underdiagnosed and, consequently, undertreated at a population and individual level. Part of the reason probably stems from the lack of health insurance reimbursement for individual clinicians and hospital systems to perform sarcopenia screening assessments.

In aging and obesity, it appears justified to include and emphasize a recommendation for sarcopenia screening in medical society guidelines; however, individual patients and clinicians do not need to wait for updated guidelines to implement sarcopenia screening, treatment, and prevention strategies in their own lives and/or clinical practice.

Simple Prevention and Treatment Strategy

Much can be done to help prevent sarcopenia. The primary strategy, unsurprisingly, is engaging in frequent strength training. But that doesn’t mean hours in the gym every week.

With just one session per week over 10 weeks, lean body mass (LBM), a common proxy for muscle mass, increased by 0.33 kg, according to a study which evaluated LBM improvements across different strength training frequencies. Adding a second weekly session was significantly better. In the twice-weekly group, LBM increased by 1.4 kg over 10 weeks, resulting in an increase in LBM more than four times greater than the once-a-week group. (There was no greater improvement in LBM by adding a third weekly session vs two weekly sessions.)

Although that particular study didn’t identify greater benefit at three times a week, compared with twice a week, the specific training routines and lack of a protein consumption assessment may have played a role in that finding.

Underlying the diminishing benefits, a different study found a marginally greater benefit in favor of performing ≥ five sets per major muscle group per week, compared with < five sets per week for increasing muscle in the legs, arms, back, chest, and shoulders.

Expensive gym memberships and fancy equipment are not necessary. While the use of strength training machines and free weights have been viewed by many as the optimal approach, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that comparable improvements to strength can be achieved with workouts using resistance bands. For those who struggle to find the time to go to a gym, or for whom gym fees are not financially affordable, resistance bands are a cheaper and more convenient alternative.

Lucas, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City, disclosed ties with Measured (Better Health Labs).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Losses of muscle and strength are inescapable effects of the aging process. Left unchecked, these progressive losses will start to impair physical function.

Once a certain level of impairment occurs, an individual can be diagnosed with sarcopenia, which comes from the Greek words “sarco” (flesh) and “penia” (poverty).

Muscle mass losses generally occur with weight loss, and the increasing use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) medications may lead to greater incidence and prevalence of sarcopenia in the years to come.

A recent meta-analysis of 56 studies (mean participant age, 50 years) found a twofold greater risk for mortality in those with sarcopenia vs those without. Despite its health consequences, sarcopenia tends to be underdiagnosed and, consequently, undertreated at a population and individual level. Part of the reason probably stems from the lack of health insurance reimbursement for individual clinicians and hospital systems to perform sarcopenia screening assessments.

In aging and obesity, it appears justified to include and emphasize a recommendation for sarcopenia screening in medical society guidelines; however, individual patients and clinicians do not need to wait for updated guidelines to implement sarcopenia screening, treatment, and prevention strategies in their own lives and/or clinical practice.

Simple Prevention and Treatment Strategy

Much can be done to help prevent sarcopenia. The primary strategy, unsurprisingly, is engaging in frequent strength training. But that doesn’t mean hours in the gym every week.

With just one session per week over 10 weeks, lean body mass (LBM), a common proxy for muscle mass, increased by 0.33 kg, according to a study which evaluated LBM improvements across different strength training frequencies. Adding a second weekly session was significantly better. In the twice-weekly group, LBM increased by 1.4 kg over 10 weeks, resulting in an increase in LBM more than four times greater than the once-a-week group. (There was no greater improvement in LBM by adding a third weekly session vs two weekly sessions.)

Although that particular study didn’t identify greater benefit at three times a week, compared with twice a week, the specific training routines and lack of a protein consumption assessment may have played a role in that finding.

Underlying the diminishing benefits, a different study found a marginally greater benefit in favor of performing ≥ five sets per major muscle group per week, compared with < five sets per week for increasing muscle in the legs, arms, back, chest, and shoulders.

Expensive gym memberships and fancy equipment are not necessary. While the use of strength training machines and free weights have been viewed by many as the optimal approach, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that comparable improvements to strength can be achieved with workouts using resistance bands. For those who struggle to find the time to go to a gym, or for whom gym fees are not financially affordable, resistance bands are a cheaper and more convenient alternative.

Lucas, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City, disclosed ties with Measured (Better Health Labs).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Heard of ApoB Testing? New Guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

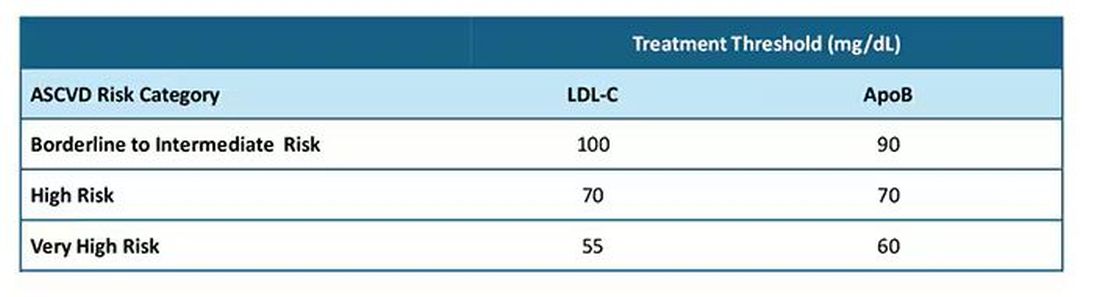

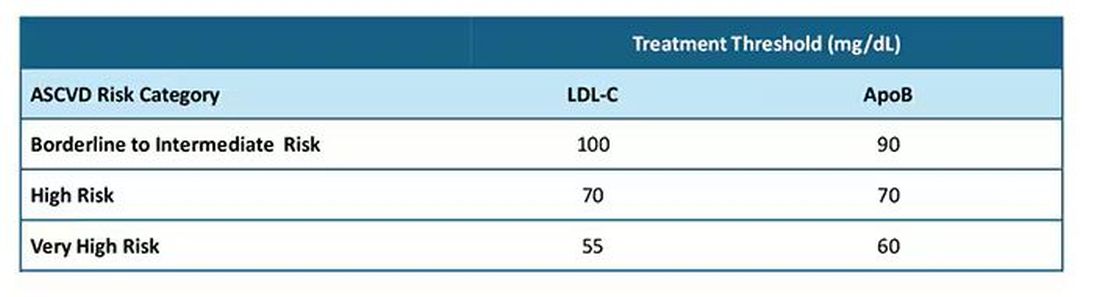

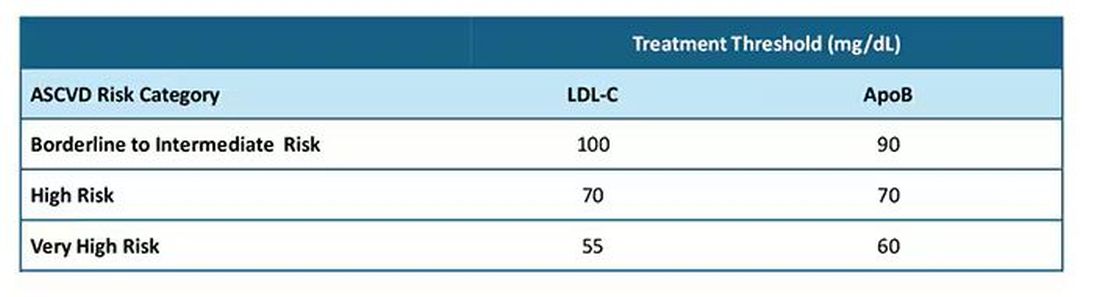

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What Should You Do When a Patient Asks for a PSA Test?

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Maternal Immunization to Prevent Serious Respiratory Illness

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.