User login

Armed conflict disproportionately affects children

I was asked recently about the trauma of 9/11 by a teen patient who was too young to remember the terrorist attacks. I was surprised that even today I become teary eyed thinking about it. My son was in his first week of college at Georgetown, and in the early confusion about what was going on I was panicked at reports of bombings in Washington. Fortunately, for me and my family at least, none of us were physically harmed. But the mental trauma still is with us. It was a momentary panic for me, but it’s not so fleeting for many families around the world today.

I can’t imagine what it is like today to be a parent in an armed conflict zone, or even in an area with very high levels of criminal violence. At a meeting of the International Society for Social Pediatrics (ISSOP), I learned that an estimated 1.5 billion residents of Earth, or about one in five inhabitants, lived in war zones or in areas of tremendous violence, according to the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report. And I learned that children are disproportionately affected – physically, mentally, and developmentally – from Stella Tsitoura, MD, of the Network for Children’s Rights, Athens, and others at the ISSOP meeting in Beirut, Lebanon, where pediatricians from around the world gathered in Oct. 2019 to consider what we as a profession should be doing in the context of armed conflict’s impact on so many children. The meeting was held in the Middle East because it is an especially hot conflict area, but children in South Asia, central Africa, South America, Central America, even rough inner-city areas in the United States are also affected.

Child soldiers in some parts of the world particularly are affected, sometimes being forced to commit violence on neighbors and kin. One country that I worked in years ago, Yemen, is a horrifying example of the complex impact of war on children and families. In 2017, over 2,100 children had been recruited as soldiers during the 3-year conflict in Yemen, a UNICEF representative reported. The death toll in Yemen was over 17,500 by Nov. 2018, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Samuel Perlo-Freeman, PhD, an expert on the economics of arms trade, noted at the ISSOP meeting that two-thirds of civilian casualties in Yemen are caused by Coalition air strikes, whose members include Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and United Arab Emirates. He also said rebel groups in Yemen and elsewhere acquire their arms by capture, by smuggling, or through the aid of foreign backers. Six countries – the United States, Russia, and several western European countries – account for the majority of war tools used in armed conflict zones. In June 2019, courts in Great Britain ruled that British arms sales to the parties involved in Yemen were illegal without an assessment as to whether any violation of internal humanitarian law had taken place.

Many of us feel impotent when facing the magnitude of this problem, and the lives of despair that affected children lead are sometimes too heart breaking to dwell on. ISSOP, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the International Pediatric Association (IPA) are teaching us differently: Standing up for the human rights of children living in areas of conflict or refugees from those areas is our responsibility, both as individuals and as members of our pediatric associations. At a basic level we need to witness – we need to share what we see with our patients who have immigrated legally or illegally in our practices, our hospitals, and our communities. It’s important to be knowledgeable of current standards of clinical care outlined by both ISSOP and the AAP to ensure our patients affected by conflict and violence get appropriate treatment.

Some of the most lasting health impacts for children in conflict are their mental health needs; the World Health Organization prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings is 22%, according to a 2019 report in the Lancet (2019 Jun;394[10194]:240-8). Not only do mental health conditions last throughout a lifetime, the impact of war can affect generations through epigenetic forces.

Arms manufacturers should be held accountable as the courts are doing in Great Britain. Too often American-made armaments are falling into the wrong hands. More can be done to limit the sale of weapons that go into conflict zones. Chemical weapons, cluster bombs, and biologic weapons are banned by international agreement; shouldn’t we do the same with nuclear weapons?

Some pediatric health care facilities are impacted by the needs of traumatized children more than others. Countries at the front line of conflict – like Lebanon, Jordon, Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Mexico – should be supported in their efforts on behalf of child refugees. We need to share the burden and support entities such as Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children, and the Red Cross/Crescent as they present themselves in crisis zones. We recognize that the fundamental human rights of children are being ignored by warring parties. especially Goal 16, which asks the world community to make real progress in promoting peace and justice by 2030. Pediatricians may not be experts in armed conflict, but we are experts in what warfare does to the health and well-being of young children. It’s time to speak out and act.

I was asked recently about the trauma of 9/11 by a teen patient who was too young to remember the terrorist attacks. I was surprised that even today I become teary eyed thinking about it. My son was in his first week of college at Georgetown, and in the early confusion about what was going on I was panicked at reports of bombings in Washington. Fortunately, for me and my family at least, none of us were physically harmed. But the mental trauma still is with us. It was a momentary panic for me, but it’s not so fleeting for many families around the world today.

I can’t imagine what it is like today to be a parent in an armed conflict zone, or even in an area with very high levels of criminal violence. At a meeting of the International Society for Social Pediatrics (ISSOP), I learned that an estimated 1.5 billion residents of Earth, or about one in five inhabitants, lived in war zones or in areas of tremendous violence, according to the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report. And I learned that children are disproportionately affected – physically, mentally, and developmentally – from Stella Tsitoura, MD, of the Network for Children’s Rights, Athens, and others at the ISSOP meeting in Beirut, Lebanon, where pediatricians from around the world gathered in Oct. 2019 to consider what we as a profession should be doing in the context of armed conflict’s impact on so many children. The meeting was held in the Middle East because it is an especially hot conflict area, but children in South Asia, central Africa, South America, Central America, even rough inner-city areas in the United States are also affected.

Child soldiers in some parts of the world particularly are affected, sometimes being forced to commit violence on neighbors and kin. One country that I worked in years ago, Yemen, is a horrifying example of the complex impact of war on children and families. In 2017, over 2,100 children had been recruited as soldiers during the 3-year conflict in Yemen, a UNICEF representative reported. The death toll in Yemen was over 17,500 by Nov. 2018, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Samuel Perlo-Freeman, PhD, an expert on the economics of arms trade, noted at the ISSOP meeting that two-thirds of civilian casualties in Yemen are caused by Coalition air strikes, whose members include Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and United Arab Emirates. He also said rebel groups in Yemen and elsewhere acquire their arms by capture, by smuggling, or through the aid of foreign backers. Six countries – the United States, Russia, and several western European countries – account for the majority of war tools used in armed conflict zones. In June 2019, courts in Great Britain ruled that British arms sales to the parties involved in Yemen were illegal without an assessment as to whether any violation of internal humanitarian law had taken place.

Many of us feel impotent when facing the magnitude of this problem, and the lives of despair that affected children lead are sometimes too heart breaking to dwell on. ISSOP, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the International Pediatric Association (IPA) are teaching us differently: Standing up for the human rights of children living in areas of conflict or refugees from those areas is our responsibility, both as individuals and as members of our pediatric associations. At a basic level we need to witness – we need to share what we see with our patients who have immigrated legally or illegally in our practices, our hospitals, and our communities. It’s important to be knowledgeable of current standards of clinical care outlined by both ISSOP and the AAP to ensure our patients affected by conflict and violence get appropriate treatment.

Some of the most lasting health impacts for children in conflict are their mental health needs; the World Health Organization prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings is 22%, according to a 2019 report in the Lancet (2019 Jun;394[10194]:240-8). Not only do mental health conditions last throughout a lifetime, the impact of war can affect generations through epigenetic forces.

Arms manufacturers should be held accountable as the courts are doing in Great Britain. Too often American-made armaments are falling into the wrong hands. More can be done to limit the sale of weapons that go into conflict zones. Chemical weapons, cluster bombs, and biologic weapons are banned by international agreement; shouldn’t we do the same with nuclear weapons?

Some pediatric health care facilities are impacted by the needs of traumatized children more than others. Countries at the front line of conflict – like Lebanon, Jordon, Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Mexico – should be supported in their efforts on behalf of child refugees. We need to share the burden and support entities such as Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children, and the Red Cross/Crescent as they present themselves in crisis zones. We recognize that the fundamental human rights of children are being ignored by warring parties. especially Goal 16, which asks the world community to make real progress in promoting peace and justice by 2030. Pediatricians may not be experts in armed conflict, but we are experts in what warfare does to the health and well-being of young children. It’s time to speak out and act.

I was asked recently about the trauma of 9/11 by a teen patient who was too young to remember the terrorist attacks. I was surprised that even today I become teary eyed thinking about it. My son was in his first week of college at Georgetown, and in the early confusion about what was going on I was panicked at reports of bombings in Washington. Fortunately, for me and my family at least, none of us were physically harmed. But the mental trauma still is with us. It was a momentary panic for me, but it’s not so fleeting for many families around the world today.

I can’t imagine what it is like today to be a parent in an armed conflict zone, or even in an area with very high levels of criminal violence. At a meeting of the International Society for Social Pediatrics (ISSOP), I learned that an estimated 1.5 billion residents of Earth, or about one in five inhabitants, lived in war zones or in areas of tremendous violence, according to the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report. And I learned that children are disproportionately affected – physically, mentally, and developmentally – from Stella Tsitoura, MD, of the Network for Children’s Rights, Athens, and others at the ISSOP meeting in Beirut, Lebanon, where pediatricians from around the world gathered in Oct. 2019 to consider what we as a profession should be doing in the context of armed conflict’s impact on so many children. The meeting was held in the Middle East because it is an especially hot conflict area, but children in South Asia, central Africa, South America, Central America, even rough inner-city areas in the United States are also affected.

Child soldiers in some parts of the world particularly are affected, sometimes being forced to commit violence on neighbors and kin. One country that I worked in years ago, Yemen, is a horrifying example of the complex impact of war on children and families. In 2017, over 2,100 children had been recruited as soldiers during the 3-year conflict in Yemen, a UNICEF representative reported. The death toll in Yemen was over 17,500 by Nov. 2018, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Samuel Perlo-Freeman, PhD, an expert on the economics of arms trade, noted at the ISSOP meeting that two-thirds of civilian casualties in Yemen are caused by Coalition air strikes, whose members include Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and United Arab Emirates. He also said rebel groups in Yemen and elsewhere acquire their arms by capture, by smuggling, or through the aid of foreign backers. Six countries – the United States, Russia, and several western European countries – account for the majority of war tools used in armed conflict zones. In June 2019, courts in Great Britain ruled that British arms sales to the parties involved in Yemen were illegal without an assessment as to whether any violation of internal humanitarian law had taken place.

Many of us feel impotent when facing the magnitude of this problem, and the lives of despair that affected children lead are sometimes too heart breaking to dwell on. ISSOP, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the International Pediatric Association (IPA) are teaching us differently: Standing up for the human rights of children living in areas of conflict or refugees from those areas is our responsibility, both as individuals and as members of our pediatric associations. At a basic level we need to witness – we need to share what we see with our patients who have immigrated legally or illegally in our practices, our hospitals, and our communities. It’s important to be knowledgeable of current standards of clinical care outlined by both ISSOP and the AAP to ensure our patients affected by conflict and violence get appropriate treatment.

Some of the most lasting health impacts for children in conflict are their mental health needs; the World Health Organization prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings is 22%, according to a 2019 report in the Lancet (2019 Jun;394[10194]:240-8). Not only do mental health conditions last throughout a lifetime, the impact of war can affect generations through epigenetic forces.

Arms manufacturers should be held accountable as the courts are doing in Great Britain. Too often American-made armaments are falling into the wrong hands. More can be done to limit the sale of weapons that go into conflict zones. Chemical weapons, cluster bombs, and biologic weapons are banned by international agreement; shouldn’t we do the same with nuclear weapons?

Some pediatric health care facilities are impacted by the needs of traumatized children more than others. Countries at the front line of conflict – like Lebanon, Jordon, Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Mexico – should be supported in their efforts on behalf of child refugees. We need to share the burden and support entities such as Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children, and the Red Cross/Crescent as they present themselves in crisis zones. We recognize that the fundamental human rights of children are being ignored by warring parties. especially Goal 16, which asks the world community to make real progress in promoting peace and justice by 2030. Pediatricians may not be experts in armed conflict, but we are experts in what warfare does to the health and well-being of young children. It’s time to speak out and act.

Psychiatrists urged to look beyond the ‘monoamine island’

Now that 2019 has passed us by, it is a time for reflection for most of us. We can think about the state of our important relationships, perhaps the growth of our children or other loved ones, the trajectory of our practices, and ideas for the future. Most commonly, I would wager, we likely think about how we might do things differently in the new year.

Applying this lens to our chosen profession, the practice of clinical psychiatry, I hope 2020 brings real, or at least, incremental change. Our profession has evolved markedly over the last several decades, from psychoanalysis to the psychopharmacology revolution, to a now largely multimodal approach. Our treatment of psychiatric illness has evolved and, for the most part, improved the lives of millions across the country and around the world.

However, in so doing, we have, perhaps inadvertently, or maybe out of necessity, found ourselves on an allegorical island that we, as clinical, everyday psychiatrists defend to the death. Surrounded by an ocean of psychiatric disorders, illnesses, and symptomatology, we wave our prescription pads (or e-pads), like wands, hoping to calm the torrents of the psychiatric sea with yet another prescription. However, I’m not writing this to bemoan modern psychopharmacology, for it has saved and improved lives and led to a fruitful practice and livelihood for me and most of my colleagues. As the torrents of illness continue to flare around us, I’m not advocating that we put down our wands and become strictly therapists. What I am advocating for is the use of different wands, as it were.

Our chosen wand is undoubtedly largely composed of monoamine-based remedies – most involving the holy trinity of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. As we stand on our island, trying to quell hurricane-force winds, shark-infested waters, or a tidal wave, we wave the same wand – hoping that a dash of monoamine will slow down winds, scare away sharks, and reduce the destructive capacity of water.

We, more than those in any other medical profession, use the same basic treatments for heterogeneous disorders, whose true underlying physiology, despite important progress over the years, remains elusive and only partly understood. We see improvement and even resolution sometimes, but, for the most part, our treatments keep our patients going, so they can continue to sail, just avoiding being capsized by the psychiatric torrents beneath the surface. When the torrents flare, we wave the same wand again, hoping that another dash of monoamine modulation, this time, maybe in a new wrapper, or with a new name, will keep the ocean calm for a bit longer. Now, this has worked for decades to keep many ships from being capsized and our island still largely habitable, but this strategy is akin to building a shelter out of twigs and leaves and grasses, and never advancing to permanent construction techniques, and just replacing broken branches and leaves that will, undoubtedly, break again.

As we stand on our island, I say, we use the branches, leaves, and twigs to build a bridge to another island, and, there, we can make new wands.

In 2020, the materials for these new wands are readily available, but we have to be willing to trust these new wands, and yet not completely discard the old wands we have used for so long. These new wands are the nonmonoamine-based treatments, which have shown remarkable efficacy and safety in patients across the country and the world. We must accept that we, as a species, are remarkably complex creatures, and the disorders we try to treat have their origins in the most complex part of our being: the brain. Therefore, considering the complexity, it is only reasonable to think that there is more to our illnesses than modulating monoamines.

In 2020, I challenge every day, clinical psychiatrists to embrace these new treatments and wave these new wands. As someone who has been fortunate enough to prescribe ketamine infusion and nasal sprays in the clinic, I can say we must gravitate toward these new treatments when clinically appropriate. While ketamine treatment is no panacea, its use, and the adoption of other nonmonoamine-based treatments, hopefully will fuel the development, use, and perhaps, most importantly, novel thinking about new biological treatment of psychiatric illness.

Dr. Shroff is board-certified in psychiatry in sleep medicine, and practices in Smyrna, Ga. He is a fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

Now that 2019 has passed us by, it is a time for reflection for most of us. We can think about the state of our important relationships, perhaps the growth of our children or other loved ones, the trajectory of our practices, and ideas for the future. Most commonly, I would wager, we likely think about how we might do things differently in the new year.

Applying this lens to our chosen profession, the practice of clinical psychiatry, I hope 2020 brings real, or at least, incremental change. Our profession has evolved markedly over the last several decades, from psychoanalysis to the psychopharmacology revolution, to a now largely multimodal approach. Our treatment of psychiatric illness has evolved and, for the most part, improved the lives of millions across the country and around the world.

However, in so doing, we have, perhaps inadvertently, or maybe out of necessity, found ourselves on an allegorical island that we, as clinical, everyday psychiatrists defend to the death. Surrounded by an ocean of psychiatric disorders, illnesses, and symptomatology, we wave our prescription pads (or e-pads), like wands, hoping to calm the torrents of the psychiatric sea with yet another prescription. However, I’m not writing this to bemoan modern psychopharmacology, for it has saved and improved lives and led to a fruitful practice and livelihood for me and most of my colleagues. As the torrents of illness continue to flare around us, I’m not advocating that we put down our wands and become strictly therapists. What I am advocating for is the use of different wands, as it were.

Our chosen wand is undoubtedly largely composed of monoamine-based remedies – most involving the holy trinity of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. As we stand on our island, trying to quell hurricane-force winds, shark-infested waters, or a tidal wave, we wave the same wand – hoping that a dash of monoamine will slow down winds, scare away sharks, and reduce the destructive capacity of water.

We, more than those in any other medical profession, use the same basic treatments for heterogeneous disorders, whose true underlying physiology, despite important progress over the years, remains elusive and only partly understood. We see improvement and even resolution sometimes, but, for the most part, our treatments keep our patients going, so they can continue to sail, just avoiding being capsized by the psychiatric torrents beneath the surface. When the torrents flare, we wave the same wand again, hoping that another dash of monoamine modulation, this time, maybe in a new wrapper, or with a new name, will keep the ocean calm for a bit longer. Now, this has worked for decades to keep many ships from being capsized and our island still largely habitable, but this strategy is akin to building a shelter out of twigs and leaves and grasses, and never advancing to permanent construction techniques, and just replacing broken branches and leaves that will, undoubtedly, break again.

As we stand on our island, I say, we use the branches, leaves, and twigs to build a bridge to another island, and, there, we can make new wands.

In 2020, the materials for these new wands are readily available, but we have to be willing to trust these new wands, and yet not completely discard the old wands we have used for so long. These new wands are the nonmonoamine-based treatments, which have shown remarkable efficacy and safety in patients across the country and the world. We must accept that we, as a species, are remarkably complex creatures, and the disorders we try to treat have their origins in the most complex part of our being: the brain. Therefore, considering the complexity, it is only reasonable to think that there is more to our illnesses than modulating monoamines.

In 2020, I challenge every day, clinical psychiatrists to embrace these new treatments and wave these new wands. As someone who has been fortunate enough to prescribe ketamine infusion and nasal sprays in the clinic, I can say we must gravitate toward these new treatments when clinically appropriate. While ketamine treatment is no panacea, its use, and the adoption of other nonmonoamine-based treatments, hopefully will fuel the development, use, and perhaps, most importantly, novel thinking about new biological treatment of psychiatric illness.

Dr. Shroff is board-certified in psychiatry in sleep medicine, and practices in Smyrna, Ga. He is a fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

Now that 2019 has passed us by, it is a time for reflection for most of us. We can think about the state of our important relationships, perhaps the growth of our children or other loved ones, the trajectory of our practices, and ideas for the future. Most commonly, I would wager, we likely think about how we might do things differently in the new year.

Applying this lens to our chosen profession, the practice of clinical psychiatry, I hope 2020 brings real, or at least, incremental change. Our profession has evolved markedly over the last several decades, from psychoanalysis to the psychopharmacology revolution, to a now largely multimodal approach. Our treatment of psychiatric illness has evolved and, for the most part, improved the lives of millions across the country and around the world.

However, in so doing, we have, perhaps inadvertently, or maybe out of necessity, found ourselves on an allegorical island that we, as clinical, everyday psychiatrists defend to the death. Surrounded by an ocean of psychiatric disorders, illnesses, and symptomatology, we wave our prescription pads (or e-pads), like wands, hoping to calm the torrents of the psychiatric sea with yet another prescription. However, I’m not writing this to bemoan modern psychopharmacology, for it has saved and improved lives and led to a fruitful practice and livelihood for me and most of my colleagues. As the torrents of illness continue to flare around us, I’m not advocating that we put down our wands and become strictly therapists. What I am advocating for is the use of different wands, as it were.

Our chosen wand is undoubtedly largely composed of monoamine-based remedies – most involving the holy trinity of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. As we stand on our island, trying to quell hurricane-force winds, shark-infested waters, or a tidal wave, we wave the same wand – hoping that a dash of monoamine will slow down winds, scare away sharks, and reduce the destructive capacity of water.

We, more than those in any other medical profession, use the same basic treatments for heterogeneous disorders, whose true underlying physiology, despite important progress over the years, remains elusive and only partly understood. We see improvement and even resolution sometimes, but, for the most part, our treatments keep our patients going, so they can continue to sail, just avoiding being capsized by the psychiatric torrents beneath the surface. When the torrents flare, we wave the same wand again, hoping that another dash of monoamine modulation, this time, maybe in a new wrapper, or with a new name, will keep the ocean calm for a bit longer. Now, this has worked for decades to keep many ships from being capsized and our island still largely habitable, but this strategy is akin to building a shelter out of twigs and leaves and grasses, and never advancing to permanent construction techniques, and just replacing broken branches and leaves that will, undoubtedly, break again.

As we stand on our island, I say, we use the branches, leaves, and twigs to build a bridge to another island, and, there, we can make new wands.

In 2020, the materials for these new wands are readily available, but we have to be willing to trust these new wands, and yet not completely discard the old wands we have used for so long. These new wands are the nonmonoamine-based treatments, which have shown remarkable efficacy and safety in patients across the country and the world. We must accept that we, as a species, are remarkably complex creatures, and the disorders we try to treat have their origins in the most complex part of our being: the brain. Therefore, considering the complexity, it is only reasonable to think that there is more to our illnesses than modulating monoamines.

In 2020, I challenge every day, clinical psychiatrists to embrace these new treatments and wave these new wands. As someone who has been fortunate enough to prescribe ketamine infusion and nasal sprays in the clinic, I can say we must gravitate toward these new treatments when clinically appropriate. While ketamine treatment is no panacea, its use, and the adoption of other nonmonoamine-based treatments, hopefully will fuel the development, use, and perhaps, most importantly, novel thinking about new biological treatment of psychiatric illness.

Dr. Shroff is board-certified in psychiatry in sleep medicine, and practices in Smyrna, Ga. He is a fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

Caution about ‘miracle cures’; more

Caution about ‘miracle cures’

I thank Drs. Katherine Epstein and Helen Farrell for the balanced approach in their article “‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?” (Psychiatry 2.0,

We need to pay serious attention to the small sample sizes and limited criteria for patient selection in trials of ketamine and MDMA, as well as to what sort of “psychotherapy” follows treatment with these agents. Many of us in psychiatric practice for the past 40 years have been humbled by patients’ idiosyncratic reactions to standard medications, let alone novel ones. Those of us who practiced psychiatry in the heyday of “party drugs” have seen many idiosyncratic reactions. Most early research with cannabinoids and lysergic acid diethylamide (and even Strassman’s trials with N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]1-5) highlighted the significance of response by drug-naïve patients vs drug-savvy individuals. Apart from Veterans Affairs trials for posttraumatic stress disorder, many trials of these drugs for treatment-resistant depression or end-of-life care have attracted non-naïve participants.6-8 Private use of entheogens is quite different from medicalizing their use. This requires our best scrutiny. Our earnest interest in improving outcomes must not be influenced by the promise of a quick fix, let alone a miracle cure.

Sara Hartley, MD

Clinical Faculty

Interim Head of Admissions

UC Berkley/UCSF Joint Medical Program

Berkeley, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Strassman RJ. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):121-124.

2. Strassman RJ. DMT: the spirit molecule. A doctor’s revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 2001.

3. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):85-97.

4. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Berg LM. Differential tolerance to biological and subjective effects of four closely spaced doses of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(9):784-795.

5. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):98-108.

6. Albott CS, et al. Improvement in suicidal ideation after repeated ketamine infusions: Relationship to reductions in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and pain. Presented at: The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Annual Conference; Mar. 28-31, 2019; Chicago.

7. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523.

8. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

Continue to: Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

J. Michael Smith’s article “Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs” (Commentary,

There needs to be a multifocal approach to incentivize medical students to choose psychiatry as a specialty. Several factors have discouraged medical students from going into psychiatry. The low reimbursement rates by insurance companies force psychiatrists to not accept insurances or to work for hospital or clinic organizations, where they become a part of the “medication management industry.” This scenario was created by the pharmaceutical industry and often leaves psychotherapy to other types of clinicians. In the not-too-distant future, advances in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence technologies will further reduce the role of medically trained psychiatrists, and might lead to them being replaced by other emerging professions (eg, psychiatric PAs) that are concentrated in urban settings where they are most profitable.

What can possibly be left for the future of the medically trained psychiatrist if a PA can diagnose and treat psychiatric patients? Why would we need more psychiatrists?

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, private practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The author responds

I appreciate Dr. Carpio’s comments, and I agree that the shortage of psychiatrists will not be addressed solely by the addition of other types of clinicians, such as PAs and nurse practitioners. However, the use of well-trained health care providers such as PAs will go a long way towards helping patients receive timely and appropriate access to care. Unfortunately, no single plan or method will be adequate to solve the shortage of psychiatrists in the United States, but that does not negate the need for utilizing all available options to improve access to quality mental health care. Physician assistants are well-trained to support this endeavor.

J. Michael Smith, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, CAQ-Psychiatry

Post-Graduate PA Mental Health Residency Training Director

Physician Assistant, ACCESS Clinic, GMHC

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Houston, Texas

Continue to: Additional anathemas in psychiatry

Additional anathemas in psychiatry

While reading Dr. Nasrallah’s “Anathemas of psychiatric practice” (From the Editor,

- Cash-only suboxone clinics. Suboxone was never intended to be used in “suboxone clinics”; it was meant to be part of an integrated treatment provided in an office-based practice. Nevertheless, this treatment has been used as such in this country. As part of this trend, an anathema has grown: cash-only suboxone clinics. Patients with severe substance use disorders can be found in every socioeconomic layer of our society, but many struggle with significant psychosocial adversity and outright poverty. Cash-only suboxone clinics put many patients in a bind. Patients spend their last dollars on a needed treatment or sell these medications to maintain their addiction, or even to purchase food.

- “Medical” marijuana. There is no credible evidence based upon methodologically sound research that cannabis has benefit for treating any mental illness. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.1 Yet, in many states, physicians—including psychiatrists—are supporting the approval of medical marijuana. I remember taking my Hippocratic Oath when I graduated from medical school, pledging to continue educating myself and my patients about evidenced-based medical science that benefits us all. I have not yet found credible evidence supporting medical marijuana.

Greed in general is a strong anathema in medicine.

Leo Bastiaens, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Radhakrishnan R, Ranganathan M, D'Souza DC. Medical marijuana: what physicians need to know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):45-47.

Caution about ‘miracle cures’

I thank Drs. Katherine Epstein and Helen Farrell for the balanced approach in their article “‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?” (Psychiatry 2.0,

We need to pay serious attention to the small sample sizes and limited criteria for patient selection in trials of ketamine and MDMA, as well as to what sort of “psychotherapy” follows treatment with these agents. Many of us in psychiatric practice for the past 40 years have been humbled by patients’ idiosyncratic reactions to standard medications, let alone novel ones. Those of us who practiced psychiatry in the heyday of “party drugs” have seen many idiosyncratic reactions. Most early research with cannabinoids and lysergic acid diethylamide (and even Strassman’s trials with N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]1-5) highlighted the significance of response by drug-naïve patients vs drug-savvy individuals. Apart from Veterans Affairs trials for posttraumatic stress disorder, many trials of these drugs for treatment-resistant depression or end-of-life care have attracted non-naïve participants.6-8 Private use of entheogens is quite different from medicalizing their use. This requires our best scrutiny. Our earnest interest in improving outcomes must not be influenced by the promise of a quick fix, let alone a miracle cure.

Sara Hartley, MD

Clinical Faculty

Interim Head of Admissions

UC Berkley/UCSF Joint Medical Program

Berkeley, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Strassman RJ. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):121-124.

2. Strassman RJ. DMT: the spirit molecule. A doctor’s revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 2001.

3. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):85-97.

4. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Berg LM. Differential tolerance to biological and subjective effects of four closely spaced doses of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(9):784-795.

5. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):98-108.

6. Albott CS, et al. Improvement in suicidal ideation after repeated ketamine infusions: Relationship to reductions in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and pain. Presented at: The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Annual Conference; Mar. 28-31, 2019; Chicago.

7. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523.

8. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

Continue to: Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

J. Michael Smith’s article “Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs” (Commentary,

There needs to be a multifocal approach to incentivize medical students to choose psychiatry as a specialty. Several factors have discouraged medical students from going into psychiatry. The low reimbursement rates by insurance companies force psychiatrists to not accept insurances or to work for hospital or clinic organizations, where they become a part of the “medication management industry.” This scenario was created by the pharmaceutical industry and often leaves psychotherapy to other types of clinicians. In the not-too-distant future, advances in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence technologies will further reduce the role of medically trained psychiatrists, and might lead to them being replaced by other emerging professions (eg, psychiatric PAs) that are concentrated in urban settings where they are most profitable.

What can possibly be left for the future of the medically trained psychiatrist if a PA can diagnose and treat psychiatric patients? Why would we need more psychiatrists?

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, private practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The author responds

I appreciate Dr. Carpio’s comments, and I agree that the shortage of psychiatrists will not be addressed solely by the addition of other types of clinicians, such as PAs and nurse practitioners. However, the use of well-trained health care providers such as PAs will go a long way towards helping patients receive timely and appropriate access to care. Unfortunately, no single plan or method will be adequate to solve the shortage of psychiatrists in the United States, but that does not negate the need for utilizing all available options to improve access to quality mental health care. Physician assistants are well-trained to support this endeavor.

J. Michael Smith, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, CAQ-Psychiatry

Post-Graduate PA Mental Health Residency Training Director

Physician Assistant, ACCESS Clinic, GMHC

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Houston, Texas

Continue to: Additional anathemas in psychiatry

Additional anathemas in psychiatry

While reading Dr. Nasrallah’s “Anathemas of psychiatric practice” (From the Editor,

- Cash-only suboxone clinics. Suboxone was never intended to be used in “suboxone clinics”; it was meant to be part of an integrated treatment provided in an office-based practice. Nevertheless, this treatment has been used as such in this country. As part of this trend, an anathema has grown: cash-only suboxone clinics. Patients with severe substance use disorders can be found in every socioeconomic layer of our society, but many struggle with significant psychosocial adversity and outright poverty. Cash-only suboxone clinics put many patients in a bind. Patients spend their last dollars on a needed treatment or sell these medications to maintain their addiction, or even to purchase food.

- “Medical” marijuana. There is no credible evidence based upon methodologically sound research that cannabis has benefit for treating any mental illness. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.1 Yet, in many states, physicians—including psychiatrists—are supporting the approval of medical marijuana. I remember taking my Hippocratic Oath when I graduated from medical school, pledging to continue educating myself and my patients about evidenced-based medical science that benefits us all. I have not yet found credible evidence supporting medical marijuana.

Greed in general is a strong anathema in medicine.

Leo Bastiaens, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Radhakrishnan R, Ranganathan M, D'Souza DC. Medical marijuana: what physicians need to know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):45-47.

Caution about ‘miracle cures’

I thank Drs. Katherine Epstein and Helen Farrell for the balanced approach in their article “‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?” (Psychiatry 2.0,

We need to pay serious attention to the small sample sizes and limited criteria for patient selection in trials of ketamine and MDMA, as well as to what sort of “psychotherapy” follows treatment with these agents. Many of us in psychiatric practice for the past 40 years have been humbled by patients’ idiosyncratic reactions to standard medications, let alone novel ones. Those of us who practiced psychiatry in the heyday of “party drugs” have seen many idiosyncratic reactions. Most early research with cannabinoids and lysergic acid diethylamide (and even Strassman’s trials with N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]1-5) highlighted the significance of response by drug-naïve patients vs drug-savvy individuals. Apart from Veterans Affairs trials for posttraumatic stress disorder, many trials of these drugs for treatment-resistant depression or end-of-life care have attracted non-naïve participants.6-8 Private use of entheogens is quite different from medicalizing their use. This requires our best scrutiny. Our earnest interest in improving outcomes must not be influenced by the promise of a quick fix, let alone a miracle cure.

Sara Hartley, MD

Clinical Faculty

Interim Head of Admissions

UC Berkley/UCSF Joint Medical Program

Berkeley, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Strassman RJ. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):121-124.

2. Strassman RJ. DMT: the spirit molecule. A doctor’s revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 2001.

3. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):85-97.

4. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Berg LM. Differential tolerance to biological and subjective effects of four closely spaced doses of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(9):784-795.

5. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):98-108.

6. Albott CS, et al. Improvement in suicidal ideation after repeated ketamine infusions: Relationship to reductions in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and pain. Presented at: The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Annual Conference; Mar. 28-31, 2019; Chicago.

7. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523.

8. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

Continue to: Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

J. Michael Smith’s article “Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs” (Commentary,

There needs to be a multifocal approach to incentivize medical students to choose psychiatry as a specialty. Several factors have discouraged medical students from going into psychiatry. The low reimbursement rates by insurance companies force psychiatrists to not accept insurances or to work for hospital or clinic organizations, where they become a part of the “medication management industry.” This scenario was created by the pharmaceutical industry and often leaves psychotherapy to other types of clinicians. In the not-too-distant future, advances in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence technologies will further reduce the role of medically trained psychiatrists, and might lead to them being replaced by other emerging professions (eg, psychiatric PAs) that are concentrated in urban settings where they are most profitable.

What can possibly be left for the future of the medically trained psychiatrist if a PA can diagnose and treat psychiatric patients? Why would we need more psychiatrists?

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, private practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The author responds

I appreciate Dr. Carpio’s comments, and I agree that the shortage of psychiatrists will not be addressed solely by the addition of other types of clinicians, such as PAs and nurse practitioners. However, the use of well-trained health care providers such as PAs will go a long way towards helping patients receive timely and appropriate access to care. Unfortunately, no single plan or method will be adequate to solve the shortage of psychiatrists in the United States, but that does not negate the need for utilizing all available options to improve access to quality mental health care. Physician assistants are well-trained to support this endeavor.

J. Michael Smith, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, CAQ-Psychiatry

Post-Graduate PA Mental Health Residency Training Director

Physician Assistant, ACCESS Clinic, GMHC

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Houston, Texas

Continue to: Additional anathemas in psychiatry

Additional anathemas in psychiatry

While reading Dr. Nasrallah’s “Anathemas of psychiatric practice” (From the Editor,

- Cash-only suboxone clinics. Suboxone was never intended to be used in “suboxone clinics”; it was meant to be part of an integrated treatment provided in an office-based practice. Nevertheless, this treatment has been used as such in this country. As part of this trend, an anathema has grown: cash-only suboxone clinics. Patients with severe substance use disorders can be found in every socioeconomic layer of our society, but many struggle with significant psychosocial adversity and outright poverty. Cash-only suboxone clinics put many patients in a bind. Patients spend their last dollars on a needed treatment or sell these medications to maintain their addiction, or even to purchase food.

- “Medical” marijuana. There is no credible evidence based upon methodologically sound research that cannabis has benefit for treating any mental illness. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.1 Yet, in many states, physicians—including psychiatrists—are supporting the approval of medical marijuana. I remember taking my Hippocratic Oath when I graduated from medical school, pledging to continue educating myself and my patients about evidenced-based medical science that benefits us all. I have not yet found credible evidence supporting medical marijuana.

Greed in general is a strong anathema in medicine.

Leo Bastiaens, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Radhakrishnan R, Ranganathan M, D'Souza DC. Medical marijuana: what physicians need to know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):45-47.

Tectonic shift

Every community practice gastroenterologist knows that private equity is making an aggressive push into our specialty. This is a tectonic shift in GI practice and the implications for private practice, academic training programs, and our GI societies are substantial. Gastro Health (Florida), Atlanta Gastro (Georgia), and GI Alliance (Texas) all closed deals with private equity in 2018 and there are reported to be 16-20 deals completed or in process currently. The three “first movers” formed practice management companies that now have acquired numerous large and small practices around the country. We have one practice with more than 200 physicians and we will see single groups of 500-1000 in the near future.

Imagine what a digestive health multi-state practice of 500 physicians (gastroenterologists, pathologists, surgeons), 200 advance practice providers (APPs) plus other ancillary professionals (psychology, nutrition) could accomplish. Gross revenues could top $1 billion. All back-office operations would be consolidated and managed professionally. Each provider would work top of license so much routine care would be shifted away from MDs. Negotiating power with payers, vendors, hospital systems, and referring providers would be immense (care would be taken to avoid the appearance of a monopoly, but Department of Justice scrutiny has already been evident). Referral sources (CVS, Optum, health systems, and a few remaining independent practices) would be secured by contract or favored reimbursement rates. Academic health systems will find competition challenging save for high tertiary and quaternary care, but even these complex procedures often will have been consolidated (and contained within risk-bundles) to a half dozen health systems by direct-to-employer contracting. Current society offerings such as meetings, journals, and clinical guidelines will become obsolete because of practice-distributed virtual education, open publishing, and internal outcomes measurement. The vast provider network will be on a single data platform so it can generate true outcomes based on a payer’s patient base (not guideline-restricted process measures), and these outcomes will be used for negotiating restricted networks.

I hope these trends will be a clarion call for our societies and training programs to awaken to a new world order and adapt their efforts to meet demands from our patients and the critical (and changing) needs of current and future digestive health professionals.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Every community practice gastroenterologist knows that private equity is making an aggressive push into our specialty. This is a tectonic shift in GI practice and the implications for private practice, academic training programs, and our GI societies are substantial. Gastro Health (Florida), Atlanta Gastro (Georgia), and GI Alliance (Texas) all closed deals with private equity in 2018 and there are reported to be 16-20 deals completed or in process currently. The three “first movers” formed practice management companies that now have acquired numerous large and small practices around the country. We have one practice with more than 200 physicians and we will see single groups of 500-1000 in the near future.

Imagine what a digestive health multi-state practice of 500 physicians (gastroenterologists, pathologists, surgeons), 200 advance practice providers (APPs) plus other ancillary professionals (psychology, nutrition) could accomplish. Gross revenues could top $1 billion. All back-office operations would be consolidated and managed professionally. Each provider would work top of license so much routine care would be shifted away from MDs. Negotiating power with payers, vendors, hospital systems, and referring providers would be immense (care would be taken to avoid the appearance of a monopoly, but Department of Justice scrutiny has already been evident). Referral sources (CVS, Optum, health systems, and a few remaining independent practices) would be secured by contract or favored reimbursement rates. Academic health systems will find competition challenging save for high tertiary and quaternary care, but even these complex procedures often will have been consolidated (and contained within risk-bundles) to a half dozen health systems by direct-to-employer contracting. Current society offerings such as meetings, journals, and clinical guidelines will become obsolete because of practice-distributed virtual education, open publishing, and internal outcomes measurement. The vast provider network will be on a single data platform so it can generate true outcomes based on a payer’s patient base (not guideline-restricted process measures), and these outcomes will be used for negotiating restricted networks.

I hope these trends will be a clarion call for our societies and training programs to awaken to a new world order and adapt their efforts to meet demands from our patients and the critical (and changing) needs of current and future digestive health professionals.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Every community practice gastroenterologist knows that private equity is making an aggressive push into our specialty. This is a tectonic shift in GI practice and the implications for private practice, academic training programs, and our GI societies are substantial. Gastro Health (Florida), Atlanta Gastro (Georgia), and GI Alliance (Texas) all closed deals with private equity in 2018 and there are reported to be 16-20 deals completed or in process currently. The three “first movers” formed practice management companies that now have acquired numerous large and small practices around the country. We have one practice with more than 200 physicians and we will see single groups of 500-1000 in the near future.

Imagine what a digestive health multi-state practice of 500 physicians (gastroenterologists, pathologists, surgeons), 200 advance practice providers (APPs) plus other ancillary professionals (psychology, nutrition) could accomplish. Gross revenues could top $1 billion. All back-office operations would be consolidated and managed professionally. Each provider would work top of license so much routine care would be shifted away from MDs. Negotiating power with payers, vendors, hospital systems, and referring providers would be immense (care would be taken to avoid the appearance of a monopoly, but Department of Justice scrutiny has already been evident). Referral sources (CVS, Optum, health systems, and a few remaining independent practices) would be secured by contract or favored reimbursement rates. Academic health systems will find competition challenging save for high tertiary and quaternary care, but even these complex procedures often will have been consolidated (and contained within risk-bundles) to a half dozen health systems by direct-to-employer contracting. Current society offerings such as meetings, journals, and clinical guidelines will become obsolete because of practice-distributed virtual education, open publishing, and internal outcomes measurement. The vast provider network will be on a single data platform so it can generate true outcomes based on a payer’s patient base (not guideline-restricted process measures), and these outcomes will be used for negotiating restricted networks.

I hope these trends will be a clarion call for our societies and training programs to awaken to a new world order and adapt their efforts to meet demands from our patients and the critical (and changing) needs of current and future digestive health professionals.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the largest psychiatric organization in the world, with >38,500 members across 100 countries. At 175 yea

I am truly honored to be nominated as the next APA President-Elect (Note: Dr. Nasrallah has withdrawn his candidacy for APA President-Elect. For a statement of explanation, click here), which prompted me to delve into the history of this great association that unifies us, empowers us, and gives us a loud voice to advocate for our patients, for our noble medical profession, and for advancing the mental health of society at large.

Our APA was established by 13 superintendents of the “Insane Asylums and Hospitals” in 1844. Its first name was a mouthful—the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions of the Insane, a term now regarded as pejorative and unscientific. Thankfully, the name was changed almost 50 years later (in 1893) to the American Medico-Psychological Association, which was refined 28 years later in 1921 to the American Psychiatric Association, a name that has lasted for the past 99 years. If I am fortunate enough to be elected by my peers this month as President-Elect, and assume the APA Presidency in May 2021, a full century after the name of APA was adopted in 1921 (the era of Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Freud), I will propose and ask the APA members to approve inserting “physicians” in the APA name so it will become the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This will clearly reflect our medical training and identity, and underscore the remarkable progress achieved by the inspiring and diligent work of countless psychiatric physicians over the past century.

By the way, per a Google search, the term “physician” came about in the 13th century, when the Anglo-Normans used the French term “physique” or remedy, to coin the English word “physic” or medicine. Science historian Howard Markel discussed how “physic” became “physician.” As for the term “psychiatrist,” it was coined in 1808 by the German physician Johann Christian Reil, and it essentially means “medical treatment of the soul.”

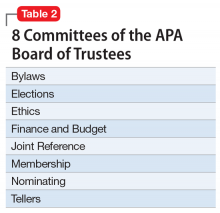

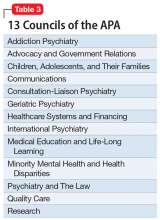

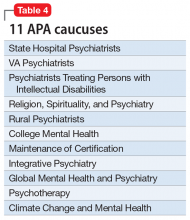

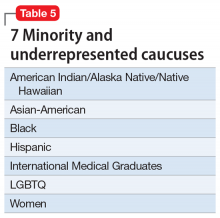

The APA has an amazing structure that is very democratic, enabling members to elect their leaders as well as their representatives on the Assembly. It has a Board of Trustees (Table 1) comprised of 22 members, 7 of whom comprise the Executive Committee, plus 3 attendees. Eight standing committees (Table 2) report to the Board. There are also 13 councils (Table 3), 11 caucuses (Table 4), and 7 minority and underrepresented caucuses (Table 5). The APA has a national network of 76 District Branches (DBs), each usually representing one state, except for large states that have several DBs (California has 5, and New York has 13). The District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Western Canada, and Quebec/Eastern Canada each have DBs as well. The DBs have their own bylaws, governance structures, and annual dues, and within them, they may have local “societies” in large cities. Finally, each DB elects representatives to the Assembly, which is comprised of 7 Areas, each of which contains several states.

I am glad to have been a member of the APA for more than 4 decades, since my residency days. Although most psychiatrists in the United States and Canada belong to the APA, some do not, either because they never joined, or they dropped out because they think the dues are high (although dues are less than half of 1% of the average psychiatrist’s annual income, which is a great bargain). So, for my colleagues who do belong, and especially for those who do not, I provide 20 reasons why being an APA member offers so many advantages, professionally and personally, and has a tremendous benefit to us individually and collectively:

1. It makes eminent sense to unify as members of a medical profession to enable us to be strong and influential, to overcome our challenges, and to achieve our goals.

Continue to: #2

2. The APA’s main objectives are to advocate for our patients, for member psychiatrists, and for the growth and success of the discipline of psychiatric medicine.

3. Being an APA member helps fight the hurtful stigma and disparity of parity, which we must all strive for together every day for our psychiatric patients.

4. A strong APA will fight for us to eliminate practice hassles such as outrageous pre-authorizations, complicated maintenance of certification process, cumbersome and time-consuming electronic medical records, and medico-legal constraints.

5. Unity affords our Association moral authority and social gravitas so that we become more credible when we educate the public to dispel the many myths and misconceptions about mental illness.

6. The APA provides us with the necessary political power and influence because medical care can be significantly impacted by good or bad legislation.

Continue to: #7

7. Our economic welfare needs a strong APA to which we all belong.

8. The antipsychiatry movement is a malignant antiscientific ideology that must be countered by all of us through a robust APA to which we all must belong.

9. The APA provides an enormous array of services and resources to all of us, individually or as groups. Many members don’t know that because they never ask.

10. While it is good to have subspecialty societies within the APA, we are all psychiatric physicians who have the same medical and psychiatric training and share the same core values. By joining the APA as our Mother Organization, we avoid Balkanization of our profession, which weakens all of us if we are divided into smaller groups.

11. The APA helps cultivate and recruit more medical students to choose psychiatry as a career. This is vital for the health of our field.

Continue to: #12

12. Mentoring residents about the professional issues of our specialty and involving them in committees is one of the priorities of the APA, which extends into the post-residency phase (early career psychiatrists).

13. The APA provides a “Big Tent” of diverse groups of colleagues across a rich mosaic of racial and ethnic groups, genders, national origins, sexual orientations, and practice settings. Our patients are diverse, and so are we.

14. Education is a top priority for the APA, providing its members with a wide array of opportunities for ongoing and life-long learning. This includes the spectacular annual meeting with its cornucopia of educational offers and newsletters, as well as many initiatives throughout the year.

15. The APA journals, especially its flagship American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP), are among the most cited publications in the world. We get them for free, even though the cost of a personal subscription to the AJP alone for non-APA members is equivalent to the entire annual dues!

16. The APA has many top researchers among its members, spread across more than 150 medical schools. Those members generate new knowledge that continuously advances the field of psychiatry and provides new evidence-based tools for psychiatric practitioners.

Continue to: #17

17. The APA is our community, an ecosystem that sustains us as psychiatrists, and connects us in many gratifying ways that keep us rejuvenated and helps us avoid burnout that may occur in absence of a supportive network of supportive peers.

18. The APA provides us discounts on malpractice insurance and other products.

19. Opportunities for personal and professional growth are available within the APA. This includes leadership skills via participation in the DBs or at the national level via committees, councils, caucuses, and the Assembly.

20. Last but not least, the APA represents all of us in The House of Medicine. It has very productive partnerships and collaborations with many other medical organizations that support us and help us achieve our cherished mission. Besides adding “Physicians” to the APA name, working closely with other physicians across many specialties (especially primary care) will consolidate our medical identity and lead to better outcomes for our patients through collaborative care initiatives.

I thank all my colleagues who are APA members or Fellows, and urge all the readers of

PS. Please VOTE in this month’s APA election! It’s our sacred duty.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the largest psychiatric organization in the world, with >38,500 members across 100 countries. At 175 yea

I am truly honored to be nominated as the next APA President-Elect (Note: Dr. Nasrallah has withdrawn his candidacy for APA President-Elect. For a statement of explanation, click here), which prompted me to delve into the history of this great association that unifies us, empowers us, and gives us a loud voice to advocate for our patients, for our noble medical profession, and for advancing the mental health of society at large.

Our APA was established by 13 superintendents of the “Insane Asylums and Hospitals” in 1844. Its first name was a mouthful—the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions of the Insane, a term now regarded as pejorative and unscientific. Thankfully, the name was changed almost 50 years later (in 1893) to the American Medico-Psychological Association, which was refined 28 years later in 1921 to the American Psychiatric Association, a name that has lasted for the past 99 years. If I am fortunate enough to be elected by my peers this month as President-Elect, and assume the APA Presidency in May 2021, a full century after the name of APA was adopted in 1921 (the era of Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Freud), I will propose and ask the APA members to approve inserting “physicians” in the APA name so it will become the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This will clearly reflect our medical training and identity, and underscore the remarkable progress achieved by the inspiring and diligent work of countless psychiatric physicians over the past century.

By the way, per a Google search, the term “physician” came about in the 13th century, when the Anglo-Normans used the French term “physique” or remedy, to coin the English word “physic” or medicine. Science historian Howard Markel discussed how “physic” became “physician.” As for the term “psychiatrist,” it was coined in 1808 by the German physician Johann Christian Reil, and it essentially means “medical treatment of the soul.”

The APA has an amazing structure that is very democratic, enabling members to elect their leaders as well as their representatives on the Assembly. It has a Board of Trustees (Table 1) comprised of 22 members, 7 of whom comprise the Executive Committee, plus 3 attendees. Eight standing committees (Table 2) report to the Board. There are also 13 councils (Table 3), 11 caucuses (Table 4), and 7 minority and underrepresented caucuses (Table 5). The APA has a national network of 76 District Branches (DBs), each usually representing one state, except for large states that have several DBs (California has 5, and New York has 13). The District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Western Canada, and Quebec/Eastern Canada each have DBs as well. The DBs have their own bylaws, governance structures, and annual dues, and within them, they may have local “societies” in large cities. Finally, each DB elects representatives to the Assembly, which is comprised of 7 Areas, each of which contains several states.

I am glad to have been a member of the APA for more than 4 decades, since my residency days. Although most psychiatrists in the United States and Canada belong to the APA, some do not, either because they never joined, or they dropped out because they think the dues are high (although dues are less than half of 1% of the average psychiatrist’s annual income, which is a great bargain). So, for my colleagues who do belong, and especially for those who do not, I provide 20 reasons why being an APA member offers so many advantages, professionally and personally, and has a tremendous benefit to us individually and collectively:

1. It makes eminent sense to unify as members of a medical profession to enable us to be strong and influential, to overcome our challenges, and to achieve our goals.

Continue to: #2

2. The APA’s main objectives are to advocate for our patients, for member psychiatrists, and for the growth and success of the discipline of psychiatric medicine.

3. Being an APA member helps fight the hurtful stigma and disparity of parity, which we must all strive for together every day for our psychiatric patients.

4. A strong APA will fight for us to eliminate practice hassles such as outrageous pre-authorizations, complicated maintenance of certification process, cumbersome and time-consuming electronic medical records, and medico-legal constraints.

5. Unity affords our Association moral authority and social gravitas so that we become more credible when we educate the public to dispel the many myths and misconceptions about mental illness.

6. The APA provides us with the necessary political power and influence because medical care can be significantly impacted by good or bad legislation.

Continue to: #7

7. Our economic welfare needs a strong APA to which we all belong.

8. The antipsychiatry movement is a malignant antiscientific ideology that must be countered by all of us through a robust APA to which we all must belong.

9. The APA provides an enormous array of services and resources to all of us, individually or as groups. Many members don’t know that because they never ask.

10. While it is good to have subspecialty societies within the APA, we are all psychiatric physicians who have the same medical and psychiatric training and share the same core values. By joining the APA as our Mother Organization, we avoid Balkanization of our profession, which weakens all of us if we are divided into smaller groups.

11. The APA helps cultivate and recruit more medical students to choose psychiatry as a career. This is vital for the health of our field.

Continue to: #12

12. Mentoring residents about the professional issues of our specialty and involving them in committees is one of the priorities of the APA, which extends into the post-residency phase (early career psychiatrists).

13. The APA provides a “Big Tent” of diverse groups of colleagues across a rich mosaic of racial and ethnic groups, genders, national origins, sexual orientations, and practice settings. Our patients are diverse, and so are we.

14. Education is a top priority for the APA, providing its members with a wide array of opportunities for ongoing and life-long learning. This includes the spectacular annual meeting with its cornucopia of educational offers and newsletters, as well as many initiatives throughout the year.

15. The APA journals, especially its flagship American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP), are among the most cited publications in the world. We get them for free, even though the cost of a personal subscription to the AJP alone for non-APA members is equivalent to the entire annual dues!

16. The APA has many top researchers among its members, spread across more than 150 medical schools. Those members generate new knowledge that continuously advances the field of psychiatry and provides new evidence-based tools for psychiatric practitioners.

Continue to: #17

17. The APA is our community, an ecosystem that sustains us as psychiatrists, and connects us in many gratifying ways that keep us rejuvenated and helps us avoid burnout that may occur in absence of a supportive network of supportive peers.

18. The APA provides us discounts on malpractice insurance and other products.

19. Opportunities for personal and professional growth are available within the APA. This includes leadership skills via participation in the DBs or at the national level via committees, councils, caucuses, and the Assembly.

20. Last but not least, the APA represents all of us in The House of Medicine. It has very productive partnerships and collaborations with many other medical organizations that support us and help us achieve our cherished mission. Besides adding “Physicians” to the APA name, working closely with other physicians across many specialties (especially primary care) will consolidate our medical identity and lead to better outcomes for our patients through collaborative care initiatives.

I thank all my colleagues who are APA members or Fellows, and urge all the readers of

PS. Please VOTE in this month’s APA election! It’s our sacred duty.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the largest psychiatric organization in the world, with >38,500 members across 100 countries. At 175 yea

I am truly honored to be nominated as the next APA President-Elect (Note: Dr. Nasrallah has withdrawn his candidacy for APA President-Elect. For a statement of explanation, click here), which prompted me to delve into the history of this great association that unifies us, empowers us, and gives us a loud voice to advocate for our patients, for our noble medical profession, and for advancing the mental health of society at large.

Our APA was established by 13 superintendents of the “Insane Asylums and Hospitals” in 1844. Its first name was a mouthful—the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions of the Insane, a term now regarded as pejorative and unscientific. Thankfully, the name was changed almost 50 years later (in 1893) to the American Medico-Psychological Association, which was refined 28 years later in 1921 to the American Psychiatric Association, a name that has lasted for the past 99 years. If I am fortunate enough to be elected by my peers this month as President-Elect, and assume the APA Presidency in May 2021, a full century after the name of APA was adopted in 1921 (the era of Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Freud), I will propose and ask the APA members to approve inserting “physicians” in the APA name so it will become the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This will clearly reflect our medical training and identity, and underscore the remarkable progress achieved by the inspiring and diligent work of countless psychiatric physicians over the past century.