User login

Advocating for reality

Our first daughter was born during my last year in medical school, and our second was born as I was finishing my second year in residency. Seeing those two little darlings grow and develop was a critical supplement to my pediatric training. And, watching my wife initially struggle and then succeed with breastfeeding provided a very personal experience and education about lactation that my interactions in the hospital and outpatient clinics didn’t offer.

We considered ourselves lucky because my wife wasn’t facing the additional challenge of returning to an out-of-the-home job. However, our good fortune did not confer immunity against the anxiety, insecurity, discomfort, and sleep deprivation–induced frustrations of breastfeeding. Watching my wife navigate the choppy waters of lactation certainly influenced my approach to counseling new mothers over my subsequent 4 decades of practice. I think I was a more sympathetic and realistic adviser based on my first-hand observations.

In a different survey of American Academy of Pediatrics fellows, more of the 832 pediatricians responding reported having had a personal experience with breastfeeding in 2014 than of the 620 responding in 1995 (68% vs. 42%). However, it is interesting that fewer of the respondents in 2014 felt that any mother can succeed at breastfeeding (predicted value = 70% in 1995, PV = 56% in 2014; P less than .05), and fewer in 2014 believed that the advantages of breastfeeding outweighed the difficulties than among those surveyed in 1995 (PV = 70% in 1995, PV = 50% in 2014; P less than .05) (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140[4]. pii: e20171229). These results suggest that, as more pediatricians gained personal experience with breastfeeding, more may have realized that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for breastfeeding are unrealistic and may contribute to the negative experiences of some women, including pediatric trainees.

An implied assumption in the AAP News article is that a pediatrician who has had a negative breastfeeding experience is less likely to be a strong advocate for breastfeeding. I would argue that a pediatrician who has witnessed or personally experienced difficulties is more likely to be a sympathetic and realistic advocate of breastfeeding.

We must walk that fine line between actively advocating for lactation-friendly hospitals and work environments and supporting mothers who, due to circumstances beyond their control, can’t meet the expectations we have created for them.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Our first daughter was born during my last year in medical school, and our second was born as I was finishing my second year in residency. Seeing those two little darlings grow and develop was a critical supplement to my pediatric training. And, watching my wife initially struggle and then succeed with breastfeeding provided a very personal experience and education about lactation that my interactions in the hospital and outpatient clinics didn’t offer.

We considered ourselves lucky because my wife wasn’t facing the additional challenge of returning to an out-of-the-home job. However, our good fortune did not confer immunity against the anxiety, insecurity, discomfort, and sleep deprivation–induced frustrations of breastfeeding. Watching my wife navigate the choppy waters of lactation certainly influenced my approach to counseling new mothers over my subsequent 4 decades of practice. I think I was a more sympathetic and realistic adviser based on my first-hand observations.

In a different survey of American Academy of Pediatrics fellows, more of the 832 pediatricians responding reported having had a personal experience with breastfeeding in 2014 than of the 620 responding in 1995 (68% vs. 42%). However, it is interesting that fewer of the respondents in 2014 felt that any mother can succeed at breastfeeding (predicted value = 70% in 1995, PV = 56% in 2014; P less than .05), and fewer in 2014 believed that the advantages of breastfeeding outweighed the difficulties than among those surveyed in 1995 (PV = 70% in 1995, PV = 50% in 2014; P less than .05) (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140[4]. pii: e20171229). These results suggest that, as more pediatricians gained personal experience with breastfeeding, more may have realized that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for breastfeeding are unrealistic and may contribute to the negative experiences of some women, including pediatric trainees.

An implied assumption in the AAP News article is that a pediatrician who has had a negative breastfeeding experience is less likely to be a strong advocate for breastfeeding. I would argue that a pediatrician who has witnessed or personally experienced difficulties is more likely to be a sympathetic and realistic advocate of breastfeeding.

We must walk that fine line between actively advocating for lactation-friendly hospitals and work environments and supporting mothers who, due to circumstances beyond their control, can’t meet the expectations we have created for them.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Our first daughter was born during my last year in medical school, and our second was born as I was finishing my second year in residency. Seeing those two little darlings grow and develop was a critical supplement to my pediatric training. And, watching my wife initially struggle and then succeed with breastfeeding provided a very personal experience and education about lactation that my interactions in the hospital and outpatient clinics didn’t offer.

We considered ourselves lucky because my wife wasn’t facing the additional challenge of returning to an out-of-the-home job. However, our good fortune did not confer immunity against the anxiety, insecurity, discomfort, and sleep deprivation–induced frustrations of breastfeeding. Watching my wife navigate the choppy waters of lactation certainly influenced my approach to counseling new mothers over my subsequent 4 decades of practice. I think I was a more sympathetic and realistic adviser based on my first-hand observations.

In a different survey of American Academy of Pediatrics fellows, more of the 832 pediatricians responding reported having had a personal experience with breastfeeding in 2014 than of the 620 responding in 1995 (68% vs. 42%). However, it is interesting that fewer of the respondents in 2014 felt that any mother can succeed at breastfeeding (predicted value = 70% in 1995, PV = 56% in 2014; P less than .05), and fewer in 2014 believed that the advantages of breastfeeding outweighed the difficulties than among those surveyed in 1995 (PV = 70% in 1995, PV = 50% in 2014; P less than .05) (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140[4]. pii: e20171229). These results suggest that, as more pediatricians gained personal experience with breastfeeding, more may have realized that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for breastfeeding are unrealistic and may contribute to the negative experiences of some women, including pediatric trainees.

An implied assumption in the AAP News article is that a pediatrician who has had a negative breastfeeding experience is less likely to be a strong advocate for breastfeeding. I would argue that a pediatrician who has witnessed or personally experienced difficulties is more likely to be a sympathetic and realistic advocate of breastfeeding.

We must walk that fine line between actively advocating for lactation-friendly hospitals and work environments and supporting mothers who, due to circumstances beyond their control, can’t meet the expectations we have created for them.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

… What comes naturally

When we were invited to a family gathering to celebrate a 60th birthday, we expected to hear an abundance of news about grandchildren. They are natural, and seldom controversial, topics of discussion. If there is a child still waiting in utero and destined to be the first grandchild on one or both sides of the family, the impending adventure in parenthood will dominate the conversation.

To our great surprise, despite the presence of one very pregnant young woman, who in 6 weeks would be giving birth to the first grandchild in my nephew’s family, my wife and I can recall only one brief dialogue in which I was asked about how one might go about selecting a pediatrician.

I’m not sure why the blessed event to come was being ignored, but I found the oversight unusual and refreshing. It is possible that there had been so much hype about the pregnancy on her side of the family that the couple relished its absence from the birthday party’s topics for discussion.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must add that, as a result of my frequent claims of ignorance when asked about medically related topics, I am often referred to by the extended family as “Dr. I-Don’t-Know.” It may be that my presence influenced the conversation, but regardless of the reason, I was impressed with the ease at which this couple was approaching the birth of their first child.

I am sure they harbor some anxieties, and I am sure they have listened to some horror stories from their peers about sleep and breastfeeding problems. They are bright people who acknowledge that they are going to encounter some bumps along the road of parenthood. However, they seem to be immune to the epidemic of anxiety that for decades has been sweeping over cohorts of North Americans entering their family-building years.

The young couple my wife and I encountered are just as clueless about what parenthood has in store as their anxiety-driven peers are. The difference is that they are enjoying their pregnancy in blissful ignorance buffered by their refreshing confidence that, however they do it, they will be doing it naturally.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When we were invited to a family gathering to celebrate a 60th birthday, we expected to hear an abundance of news about grandchildren. They are natural, and seldom controversial, topics of discussion. If there is a child still waiting in utero and destined to be the first grandchild on one or both sides of the family, the impending adventure in parenthood will dominate the conversation.

To our great surprise, despite the presence of one very pregnant young woman, who in 6 weeks would be giving birth to the first grandchild in my nephew’s family, my wife and I can recall only one brief dialogue in which I was asked about how one might go about selecting a pediatrician.

I’m not sure why the blessed event to come was being ignored, but I found the oversight unusual and refreshing. It is possible that there had been so much hype about the pregnancy on her side of the family that the couple relished its absence from the birthday party’s topics for discussion.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must add that, as a result of my frequent claims of ignorance when asked about medically related topics, I am often referred to by the extended family as “Dr. I-Don’t-Know.” It may be that my presence influenced the conversation, but regardless of the reason, I was impressed with the ease at which this couple was approaching the birth of their first child.

I am sure they harbor some anxieties, and I am sure they have listened to some horror stories from their peers about sleep and breastfeeding problems. They are bright people who acknowledge that they are going to encounter some bumps along the road of parenthood. However, they seem to be immune to the epidemic of anxiety that for decades has been sweeping over cohorts of North Americans entering their family-building years.

The young couple my wife and I encountered are just as clueless about what parenthood has in store as their anxiety-driven peers are. The difference is that they are enjoying their pregnancy in blissful ignorance buffered by their refreshing confidence that, however they do it, they will be doing it naturally.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When we were invited to a family gathering to celebrate a 60th birthday, we expected to hear an abundance of news about grandchildren. They are natural, and seldom controversial, topics of discussion. If there is a child still waiting in utero and destined to be the first grandchild on one or both sides of the family, the impending adventure in parenthood will dominate the conversation.

To our great surprise, despite the presence of one very pregnant young woman, who in 6 weeks would be giving birth to the first grandchild in my nephew’s family, my wife and I can recall only one brief dialogue in which I was asked about how one might go about selecting a pediatrician.

I’m not sure why the blessed event to come was being ignored, but I found the oversight unusual and refreshing. It is possible that there had been so much hype about the pregnancy on her side of the family that the couple relished its absence from the birthday party’s topics for discussion.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must add that, as a result of my frequent claims of ignorance when asked about medically related topics, I am often referred to by the extended family as “Dr. I-Don’t-Know.” It may be that my presence influenced the conversation, but regardless of the reason, I was impressed with the ease at which this couple was approaching the birth of their first child.

I am sure they harbor some anxieties, and I am sure they have listened to some horror stories from their peers about sleep and breastfeeding problems. They are bright people who acknowledge that they are going to encounter some bumps along the road of parenthood. However, they seem to be immune to the epidemic of anxiety that for decades has been sweeping over cohorts of North Americans entering their family-building years.

The young couple my wife and I encountered are just as clueless about what parenthood has in store as their anxiety-driven peers are. The difference is that they are enjoying their pregnancy in blissful ignorance buffered by their refreshing confidence that, however they do it, they will be doing it naturally.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Shades of gray

If you were born in or after the 1970s, it is very likely that you have never watched a television show on a black and white set. Although the roots of its technology extend well back into the early 20th century, the first color broadcast on a national television network didn’t occur until 1954 with NBC’s coverage of the Tournament of Roses Parade.

When we compare the popularization of color television with the rapid pace at which we adopt new technology today, the popularization of color TV was glacial. In large part because of their expense, sales of color sets did not surpass black and white sets until 1972. Our family lagged behind the curve and finally caved in and junked our black and white television around 1977.

The observable change in our viewing behavior was dramatic. While programming in black and white was interesting, the color images were magnetic. We were drawn by the visual excitement and stimulation that color offered, and our family’s viewing standards took a precipitous dip. We seemed to watch anything that was colorful and moved. The quality of the content took a back seat. Viewing in color seemed to require much less cognitive effort. Ironically what attracted our attention allowed us to invest less energy in paying attention.

As a regular reader of Letters From Maine, you know that I am convinced that sleep deprivation is a major contributor to the emergence of the ADHD phenomenon. However, I can make a similar argument that the introduction of color television is an equally potent coconspirator or confounder. The magnetism inherent in a moving color image can tempt even the most health conscious among us to stay well past a brain-friendly bedtime. The invention of the electric light may have gotten the ball rolling, but the ubiquity of moving electronic color images has certainly greased what was already a very slippery slope into an abyss of unhealthy sleep habits.

There are those who argue that smartphones and tablets can open a world of creative opportunities for even very young children. And, it is obvious that parents are struggling to find a balance as they try to decide when, where, and how often to allow their infants and toddlers access to handheld electronic devices.

Recently there has been much finger-pointing at the developers and manufacturers of smartphones and tablets. How can any company with a social conscience sell a product with such dangerous attractive potential for children without providing safeguards? Isn’t it like selling a swimming pool without a gated fence?

Of course the answer to this question goes to the heart of how our society views its responsibility to protect its children. Regardless of who makes the rules and how the responsibility is assigned, it is still the child’s parents who must make sure that the gate is locked.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

If you were born in or after the 1970s, it is very likely that you have never watched a television show on a black and white set. Although the roots of its technology extend well back into the early 20th century, the first color broadcast on a national television network didn’t occur until 1954 with NBC’s coverage of the Tournament of Roses Parade.

When we compare the popularization of color television with the rapid pace at which we adopt new technology today, the popularization of color TV was glacial. In large part because of their expense, sales of color sets did not surpass black and white sets until 1972. Our family lagged behind the curve and finally caved in and junked our black and white television around 1977.

The observable change in our viewing behavior was dramatic. While programming in black and white was interesting, the color images were magnetic. We were drawn by the visual excitement and stimulation that color offered, and our family’s viewing standards took a precipitous dip. We seemed to watch anything that was colorful and moved. The quality of the content took a back seat. Viewing in color seemed to require much less cognitive effort. Ironically what attracted our attention allowed us to invest less energy in paying attention.

As a regular reader of Letters From Maine, you know that I am convinced that sleep deprivation is a major contributor to the emergence of the ADHD phenomenon. However, I can make a similar argument that the introduction of color television is an equally potent coconspirator or confounder. The magnetism inherent in a moving color image can tempt even the most health conscious among us to stay well past a brain-friendly bedtime. The invention of the electric light may have gotten the ball rolling, but the ubiquity of moving electronic color images has certainly greased what was already a very slippery slope into an abyss of unhealthy sleep habits.

There are those who argue that smartphones and tablets can open a world of creative opportunities for even very young children. And, it is obvious that parents are struggling to find a balance as they try to decide when, where, and how often to allow their infants and toddlers access to handheld electronic devices.

Recently there has been much finger-pointing at the developers and manufacturers of smartphones and tablets. How can any company with a social conscience sell a product with such dangerous attractive potential for children without providing safeguards? Isn’t it like selling a swimming pool without a gated fence?

Of course the answer to this question goes to the heart of how our society views its responsibility to protect its children. Regardless of who makes the rules and how the responsibility is assigned, it is still the child’s parents who must make sure that the gate is locked.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

If you were born in or after the 1970s, it is very likely that you have never watched a television show on a black and white set. Although the roots of its technology extend well back into the early 20th century, the first color broadcast on a national television network didn’t occur until 1954 with NBC’s coverage of the Tournament of Roses Parade.

When we compare the popularization of color television with the rapid pace at which we adopt new technology today, the popularization of color TV was glacial. In large part because of their expense, sales of color sets did not surpass black and white sets until 1972. Our family lagged behind the curve and finally caved in and junked our black and white television around 1977.

The observable change in our viewing behavior was dramatic. While programming in black and white was interesting, the color images were magnetic. We were drawn by the visual excitement and stimulation that color offered, and our family’s viewing standards took a precipitous dip. We seemed to watch anything that was colorful and moved. The quality of the content took a back seat. Viewing in color seemed to require much less cognitive effort. Ironically what attracted our attention allowed us to invest less energy in paying attention.

As a regular reader of Letters From Maine, you know that I am convinced that sleep deprivation is a major contributor to the emergence of the ADHD phenomenon. However, I can make a similar argument that the introduction of color television is an equally potent coconspirator or confounder. The magnetism inherent in a moving color image can tempt even the most health conscious among us to stay well past a brain-friendly bedtime. The invention of the electric light may have gotten the ball rolling, but the ubiquity of moving electronic color images has certainly greased what was already a very slippery slope into an abyss of unhealthy sleep habits.

There are those who argue that smartphones and tablets can open a world of creative opportunities for even very young children. And, it is obvious that parents are struggling to find a balance as they try to decide when, where, and how often to allow their infants and toddlers access to handheld electronic devices.

Recently there has been much finger-pointing at the developers and manufacturers of smartphones and tablets. How can any company with a social conscience sell a product with such dangerous attractive potential for children without providing safeguards? Isn’t it like selling a swimming pool without a gated fence?

Of course the answer to this question goes to the heart of how our society views its responsibility to protect its children. Regardless of who makes the rules and how the responsibility is assigned, it is still the child’s parents who must make sure that the gate is locked.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Commentary—Serotonin Syndrome and Triptans

Serotonin syndrome (SS) is diagnosed by the clinical triad of dysautonomia (fever, mydriasis, diaphoresis, tachycardia), neuromuscular signs (ataxia, hyperreflexia, tremor, myoclonus), and altered mental status (seizures, delirium). Two validated criteria groups are accepted, the Hunter criteria and the Sternbach criteria. These criteria require a menu-like approach of clinical manifestations of the above signs with known addition or increase of a serotonergic medication and the absence of other possible causes, such as neuroleptics.

In 2006, the FDA issued a clinical warning titled “Potentially Life-Threatening Serotonin Syndrome With Combined Use of SSRIs or SNRIs and Triptan Medications.” Subsequently, Randolph W. Evans, MD, and others conducted a close evaluation of the cases used by the FDA as the basis for their warning. They noted that none of the initial cases met Hunter criteria, only 10 of 29 met Sternbach criteria, and a second set of 11 patients also were questionable in terms of the diagnosis of serotonin toxicity. Serotonin (5-HT) toxicity is mediated by excessive activity of 5-HT2A receptors, and triptans have no action at those receptors, only having activity at 5-HT1B, 1D, and 1F receptors.

In 2010, the American Headache Society (AHS) published a position paper on this drug-drug interaction. In it, they stated, “with only Class IV evidence available in the literature and available through the FDA registration of adverse events, …the currently available evidence does not support limiting the use of triptans with SSRIs or SNRIs, or the use of triptan monotherapy, due to concerns for serotonin syndrome (Level U).”

Confirming the lack of evidence for an interaction, Dr. Yulia Orlova from the Graham Headache Center in Boston reported from the Partners Healthcare System Research Patient Data Registry on about 48,000 patients prescribed triptans, of whom about 19,000 were also co-prescribed SSRI or SNRI antidepressants. None of the cases met Hunter and Sternbach criteria and one patient who manifested serotonin toxicity had signs that preceded triptan use. A previous trial of a cohort of 240,268 patients receiving pharmacy benefits reported that the frequency of co-prescription of triptans with SSRIs was about 20%. With the size of these reports, the absence of documented cases fulfilling both sets of criteria, and the lack of receptor plausibility as a cause for serotonin toxicity from triptans, the likelihood of the syndrome from triptan use is low, and the warning inappropriate. The co-occurrence of depression, anxiety, and migraine often makes co-prescription of triptans and antidepressants necessary, and the concern for co-prescription excessive.

—Stewart J. Tepper, MD

Professor of Neurology

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

Serotonin syndrome (SS) is diagnosed by the clinical triad of dysautonomia (fever, mydriasis, diaphoresis, tachycardia), neuromuscular signs (ataxia, hyperreflexia, tremor, myoclonus), and altered mental status (seizures, delirium). Two validated criteria groups are accepted, the Hunter criteria and the Sternbach criteria. These criteria require a menu-like approach of clinical manifestations of the above signs with known addition or increase of a serotonergic medication and the absence of other possible causes, such as neuroleptics.

In 2006, the FDA issued a clinical warning titled “Potentially Life-Threatening Serotonin Syndrome With Combined Use of SSRIs or SNRIs and Triptan Medications.” Subsequently, Randolph W. Evans, MD, and others conducted a close evaluation of the cases used by the FDA as the basis for their warning. They noted that none of the initial cases met Hunter criteria, only 10 of 29 met Sternbach criteria, and a second set of 11 patients also were questionable in terms of the diagnosis of serotonin toxicity. Serotonin (5-HT) toxicity is mediated by excessive activity of 5-HT2A receptors, and triptans have no action at those receptors, only having activity at 5-HT1B, 1D, and 1F receptors.

In 2010, the American Headache Society (AHS) published a position paper on this drug-drug interaction. In it, they stated, “with only Class IV evidence available in the literature and available through the FDA registration of adverse events, …the currently available evidence does not support limiting the use of triptans with SSRIs or SNRIs, or the use of triptan monotherapy, due to concerns for serotonin syndrome (Level U).”

Confirming the lack of evidence for an interaction, Dr. Yulia Orlova from the Graham Headache Center in Boston reported from the Partners Healthcare System Research Patient Data Registry on about 48,000 patients prescribed triptans, of whom about 19,000 were also co-prescribed SSRI or SNRI antidepressants. None of the cases met Hunter and Sternbach criteria and one patient who manifested serotonin toxicity had signs that preceded triptan use. A previous trial of a cohort of 240,268 patients receiving pharmacy benefits reported that the frequency of co-prescription of triptans with SSRIs was about 20%. With the size of these reports, the absence of documented cases fulfilling both sets of criteria, and the lack of receptor plausibility as a cause for serotonin toxicity from triptans, the likelihood of the syndrome from triptan use is low, and the warning inappropriate. The co-occurrence of depression, anxiety, and migraine often makes co-prescription of triptans and antidepressants necessary, and the concern for co-prescription excessive.

—Stewart J. Tepper, MD

Professor of Neurology

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

Serotonin syndrome (SS) is diagnosed by the clinical triad of dysautonomia (fever, mydriasis, diaphoresis, tachycardia), neuromuscular signs (ataxia, hyperreflexia, tremor, myoclonus), and altered mental status (seizures, delirium). Two validated criteria groups are accepted, the Hunter criteria and the Sternbach criteria. These criteria require a menu-like approach of clinical manifestations of the above signs with known addition or increase of a serotonergic medication and the absence of other possible causes, such as neuroleptics.

In 2006, the FDA issued a clinical warning titled “Potentially Life-Threatening Serotonin Syndrome With Combined Use of SSRIs or SNRIs and Triptan Medications.” Subsequently, Randolph W. Evans, MD, and others conducted a close evaluation of the cases used by the FDA as the basis for their warning. They noted that none of the initial cases met Hunter criteria, only 10 of 29 met Sternbach criteria, and a second set of 11 patients also were questionable in terms of the diagnosis of serotonin toxicity. Serotonin (5-HT) toxicity is mediated by excessive activity of 5-HT2A receptors, and triptans have no action at those receptors, only having activity at 5-HT1B, 1D, and 1F receptors.

In 2010, the American Headache Society (AHS) published a position paper on this drug-drug interaction. In it, they stated, “with only Class IV evidence available in the literature and available through the FDA registration of adverse events, …the currently available evidence does not support limiting the use of triptans with SSRIs or SNRIs, or the use of triptan monotherapy, due to concerns for serotonin syndrome (Level U).”

Confirming the lack of evidence for an interaction, Dr. Yulia Orlova from the Graham Headache Center in Boston reported from the Partners Healthcare System Research Patient Data Registry on about 48,000 patients prescribed triptans, of whom about 19,000 were also co-prescribed SSRI or SNRI antidepressants. None of the cases met Hunter and Sternbach criteria and one patient who manifested serotonin toxicity had signs that preceded triptan use. A previous trial of a cohort of 240,268 patients receiving pharmacy benefits reported that the frequency of co-prescription of triptans with SSRIs was about 20%. With the size of these reports, the absence of documented cases fulfilling both sets of criteria, and the lack of receptor plausibility as a cause for serotonin toxicity from triptans, the likelihood of the syndrome from triptan use is low, and the warning inappropriate. The co-occurrence of depression, anxiety, and migraine often makes co-prescription of triptans and antidepressants necessary, and the concern for co-prescription excessive.

—Stewart J. Tepper, MD

Professor of Neurology

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

A New Era for Physician-Patient Communication in Dermatology

The physician-patient relationship is an important component of patient care. In the last few years a new paradigm has emerged of instant communication. Because dermatologic diagnosis is visual, many patients feel that making a correct diagnosis is as easy as taking a quick look. The availability of smartphone photography and easy ways to get in touch with dermatologists have created a new reality in physician-patient communication, which sometimes may be abused. We conducted an email survey to assess the attitudes of Chilean dermatologists regarding new methods of communication with their patients.

A survey of 16 questions was distributed to all 343 members of the Chilean Society of Dermatology and Venerology from July 2016 to August 2016. A total of 147 (42.9%) dermatologists completed the survey. When asked if they use personal and direct communication with their patients outside of an office visit, 39% of respondents said always, 41% said sometimes, 17% said only in some circumstances, and 3% said never. Regarding the method of communication, 79% used personal email, 59% used mobile phones, 35% used corporate email, and 34% used text messages. Among respondents who gave their personal email address and phone number to patients, the primary reason stated was to be available for any kind of emergency (67%), for patient follow-up (57%), and for patients to feel close to their dermatologist (28%).

Sixty-nine percent of respondents said patients occasionally have requested to receive a diagnosis via a mobile messaging application, social networks, and email. Of them, 22% said they were very annoyed by these requests. When dermatologists were asked if these instant types of communication improved their relationship with patients, 30% said it does help and 36% said it does not; 30% said they do not know and 4% did not respond. If patients used personal methods of communication to contact their dermatologist that was considered outside of physician-patient boundaries, 63% of physician respondents said they kindly directed patients to formal ways of communication and 15% did not respond to such requests; 22% responded by informal methods of communication. Eighty-one percent of all respondents felt the limits of formal communication between physicians and patients have been surpassed.

To improve the quality of health care, many clinicians use modern methods of communication with their patients. Today, patients can turn to their physicians for medical advice by mobile phone or email. We attempted to characterize the attitudes of Chilean dermatologists regarding new ways of communicating with patients. Our results are similar to other studies. One analysis of primary care physicians in Geneva, Switzerland (N=372), showed that 72% gave their personal email address and 74% gave their mobile phone number to patients. The latter is higher than what was found in our study (59%), which may be explained by the fact that primary care physicians may need to maintain closer contact with their patients.1

In another study performed in primary care physicians in Israel, physicians preferred to provide their mobile phone number rather than their personal email address because they felt that email communication was more likely to lead miscommunication than a phone call.2 There are few reports on this subject in the international literature, and we believe cultural differences may be important when physicians confront these issues.

In general, patient satisfaction is high when patients can contact their physician by phone or email; however, new immediate forms of communication may lead to physician burnout, as patients expect immediate responses and solutions to their requests and healthy physician-patient boundaries may be surpassed. It is important to educate both patients and physicians on how these new tools may be properly used on both sides. New boundaries must be set.

- Dash J, Haller DM, Sommer J, et al. Use of email, cell phone and text message between patients and primary-care physicians: cross-sectional study in a French-speaking part of Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:549.

- Peleg R, Avdalimov A, Freud T. Providing cell phone numbers and email addresses to patients: the physician’s perspective. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:76.

The physician-patient relationship is an important component of patient care. In the last few years a new paradigm has emerged of instant communication. Because dermatologic diagnosis is visual, many patients feel that making a correct diagnosis is as easy as taking a quick look. The availability of smartphone photography and easy ways to get in touch with dermatologists have created a new reality in physician-patient communication, which sometimes may be abused. We conducted an email survey to assess the attitudes of Chilean dermatologists regarding new methods of communication with their patients.

A survey of 16 questions was distributed to all 343 members of the Chilean Society of Dermatology and Venerology from July 2016 to August 2016. A total of 147 (42.9%) dermatologists completed the survey. When asked if they use personal and direct communication with their patients outside of an office visit, 39% of respondents said always, 41% said sometimes, 17% said only in some circumstances, and 3% said never. Regarding the method of communication, 79% used personal email, 59% used mobile phones, 35% used corporate email, and 34% used text messages. Among respondents who gave their personal email address and phone number to patients, the primary reason stated was to be available for any kind of emergency (67%), for patient follow-up (57%), and for patients to feel close to their dermatologist (28%).

Sixty-nine percent of respondents said patients occasionally have requested to receive a diagnosis via a mobile messaging application, social networks, and email. Of them, 22% said they were very annoyed by these requests. When dermatologists were asked if these instant types of communication improved their relationship with patients, 30% said it does help and 36% said it does not; 30% said they do not know and 4% did not respond. If patients used personal methods of communication to contact their dermatologist that was considered outside of physician-patient boundaries, 63% of physician respondents said they kindly directed patients to formal ways of communication and 15% did not respond to such requests; 22% responded by informal methods of communication. Eighty-one percent of all respondents felt the limits of formal communication between physicians and patients have been surpassed.

To improve the quality of health care, many clinicians use modern methods of communication with their patients. Today, patients can turn to their physicians for medical advice by mobile phone or email. We attempted to characterize the attitudes of Chilean dermatologists regarding new ways of communicating with patients. Our results are similar to other studies. One analysis of primary care physicians in Geneva, Switzerland (N=372), showed that 72% gave their personal email address and 74% gave their mobile phone number to patients. The latter is higher than what was found in our study (59%), which may be explained by the fact that primary care physicians may need to maintain closer contact with their patients.1

In another study performed in primary care physicians in Israel, physicians preferred to provide their mobile phone number rather than their personal email address because they felt that email communication was more likely to lead miscommunication than a phone call.2 There are few reports on this subject in the international literature, and we believe cultural differences may be important when physicians confront these issues.

In general, patient satisfaction is high when patients can contact their physician by phone or email; however, new immediate forms of communication may lead to physician burnout, as patients expect immediate responses and solutions to their requests and healthy physician-patient boundaries may be surpassed. It is important to educate both patients and physicians on how these new tools may be properly used on both sides. New boundaries must be set.

The physician-patient relationship is an important component of patient care. In the last few years a new paradigm has emerged of instant communication. Because dermatologic diagnosis is visual, many patients feel that making a correct diagnosis is as easy as taking a quick look. The availability of smartphone photography and easy ways to get in touch with dermatologists have created a new reality in physician-patient communication, which sometimes may be abused. We conducted an email survey to assess the attitudes of Chilean dermatologists regarding new methods of communication with their patients.

A survey of 16 questions was distributed to all 343 members of the Chilean Society of Dermatology and Venerology from July 2016 to August 2016. A total of 147 (42.9%) dermatologists completed the survey. When asked if they use personal and direct communication with their patients outside of an office visit, 39% of respondents said always, 41% said sometimes, 17% said only in some circumstances, and 3% said never. Regarding the method of communication, 79% used personal email, 59% used mobile phones, 35% used corporate email, and 34% used text messages. Among respondents who gave their personal email address and phone number to patients, the primary reason stated was to be available for any kind of emergency (67%), for patient follow-up (57%), and for patients to feel close to their dermatologist (28%).

Sixty-nine percent of respondents said patients occasionally have requested to receive a diagnosis via a mobile messaging application, social networks, and email. Of them, 22% said they were very annoyed by these requests. When dermatologists were asked if these instant types of communication improved their relationship with patients, 30% said it does help and 36% said it does not; 30% said they do not know and 4% did not respond. If patients used personal methods of communication to contact their dermatologist that was considered outside of physician-patient boundaries, 63% of physician respondents said they kindly directed patients to formal ways of communication and 15% did not respond to such requests; 22% responded by informal methods of communication. Eighty-one percent of all respondents felt the limits of formal communication between physicians and patients have been surpassed.

To improve the quality of health care, many clinicians use modern methods of communication with their patients. Today, patients can turn to their physicians for medical advice by mobile phone or email. We attempted to characterize the attitudes of Chilean dermatologists regarding new ways of communicating with patients. Our results are similar to other studies. One analysis of primary care physicians in Geneva, Switzerland (N=372), showed that 72% gave their personal email address and 74% gave their mobile phone number to patients. The latter is higher than what was found in our study (59%), which may be explained by the fact that primary care physicians may need to maintain closer contact with their patients.1

In another study performed in primary care physicians in Israel, physicians preferred to provide their mobile phone number rather than their personal email address because they felt that email communication was more likely to lead miscommunication than a phone call.2 There are few reports on this subject in the international literature, and we believe cultural differences may be important when physicians confront these issues.

In general, patient satisfaction is high when patients can contact their physician by phone or email; however, new immediate forms of communication may lead to physician burnout, as patients expect immediate responses and solutions to their requests and healthy physician-patient boundaries may be surpassed. It is important to educate both patients and physicians on how these new tools may be properly used on both sides. New boundaries must be set.

- Dash J, Haller DM, Sommer J, et al. Use of email, cell phone and text message between patients and primary-care physicians: cross-sectional study in a French-speaking part of Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:549.

- Peleg R, Avdalimov A, Freud T. Providing cell phone numbers and email addresses to patients: the physician’s perspective. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:76.

- Dash J, Haller DM, Sommer J, et al. Use of email, cell phone and text message between patients and primary-care physicians: cross-sectional study in a French-speaking part of Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:549.

- Peleg R, Avdalimov A, Freud T. Providing cell phone numbers and email addresses to patients: the physician’s perspective. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:76.

Pain-Minimizing Strategies for Nail Surgery

Nail surgery is an important part of dermatologic training and clinical practice, both for diagnosis and treatment of nail disorders as well as benign and malignant nail tumors. Patient comfort is essential prior to the procedure and while administering local anesthetics. Effective anesthesia facilitates nail unit biopsies, excisions, and other surgical nail procedures. Pain management immediately following the procedure and during the postoperative period are equally important.

Patients who undergo nail surgery may experience anxiety due to fear of a cancer diagnosis, pain during the surgery, or disfigurement from the procedure. This anxiety may lead to increased blood pressure, a decreased pain threshold, and mental and physical discomfort.1 A detailed explanation of the procedure itself as well as expectations following the surgery are helpful in diminishing these fears. Administration of a fast-acting benzodiazepine also may be helpful in these patients to decrease anxiety prior to the procedure.2

Attaining adequate anesthesia requires an understanding of digital anatomy, particularly innervation. Innervation of the digits is supplied by the volar and dorsal nerves, which divide into 3 branches at the distal interphalangeal joint, innervating the nail bed, the digital tip, and the pulp.3 Pacinian and Ruffini corpuscles and free-ended nociceptors activate nerve fibers that transmit pain impulses.4,5 Local anesthetics block pain transmission by impeding voltage-gated sodium channels located at free nerve endings. Pain from anesthesia may be due to both needle insertion and fluid infiltration.

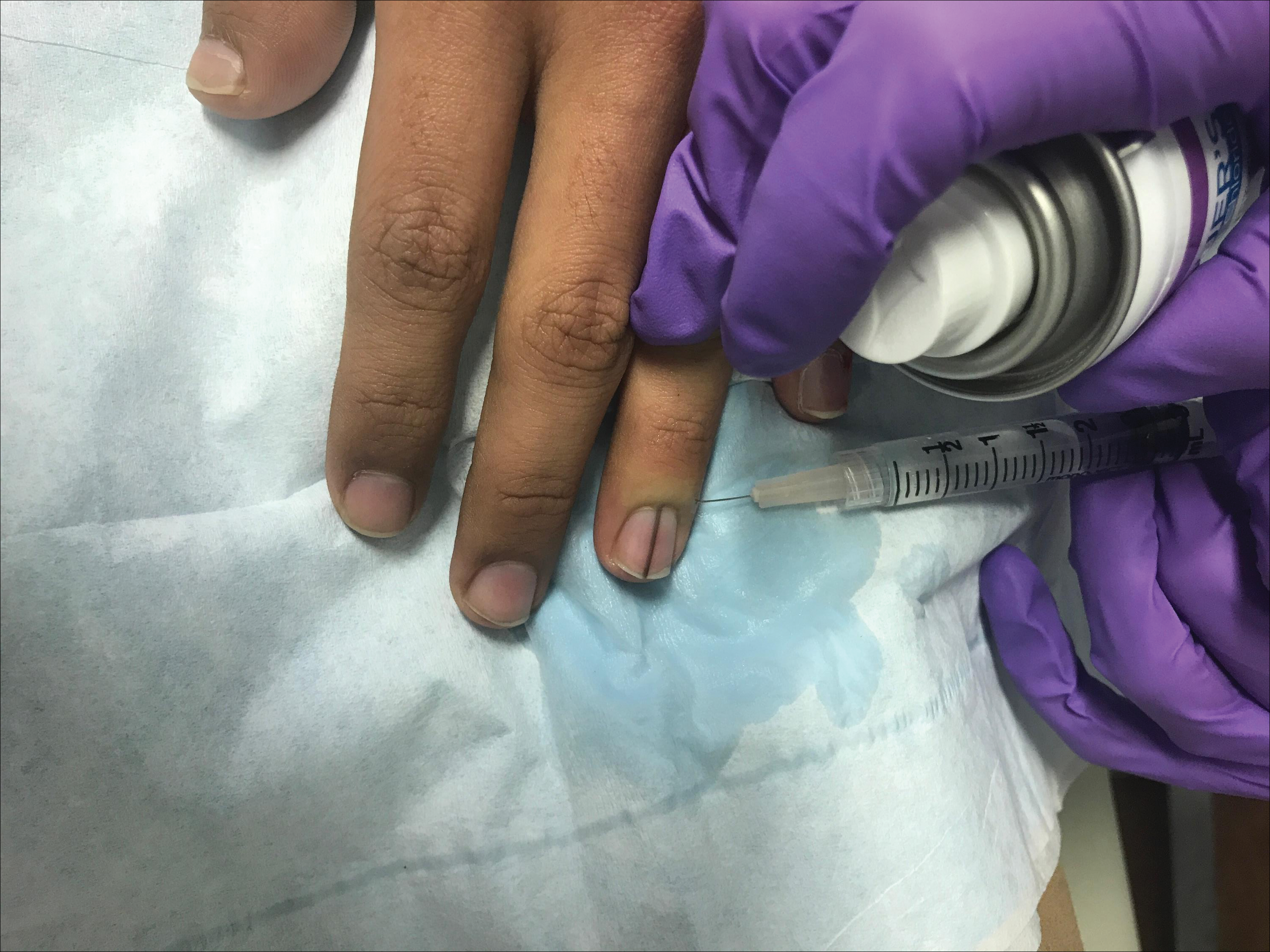

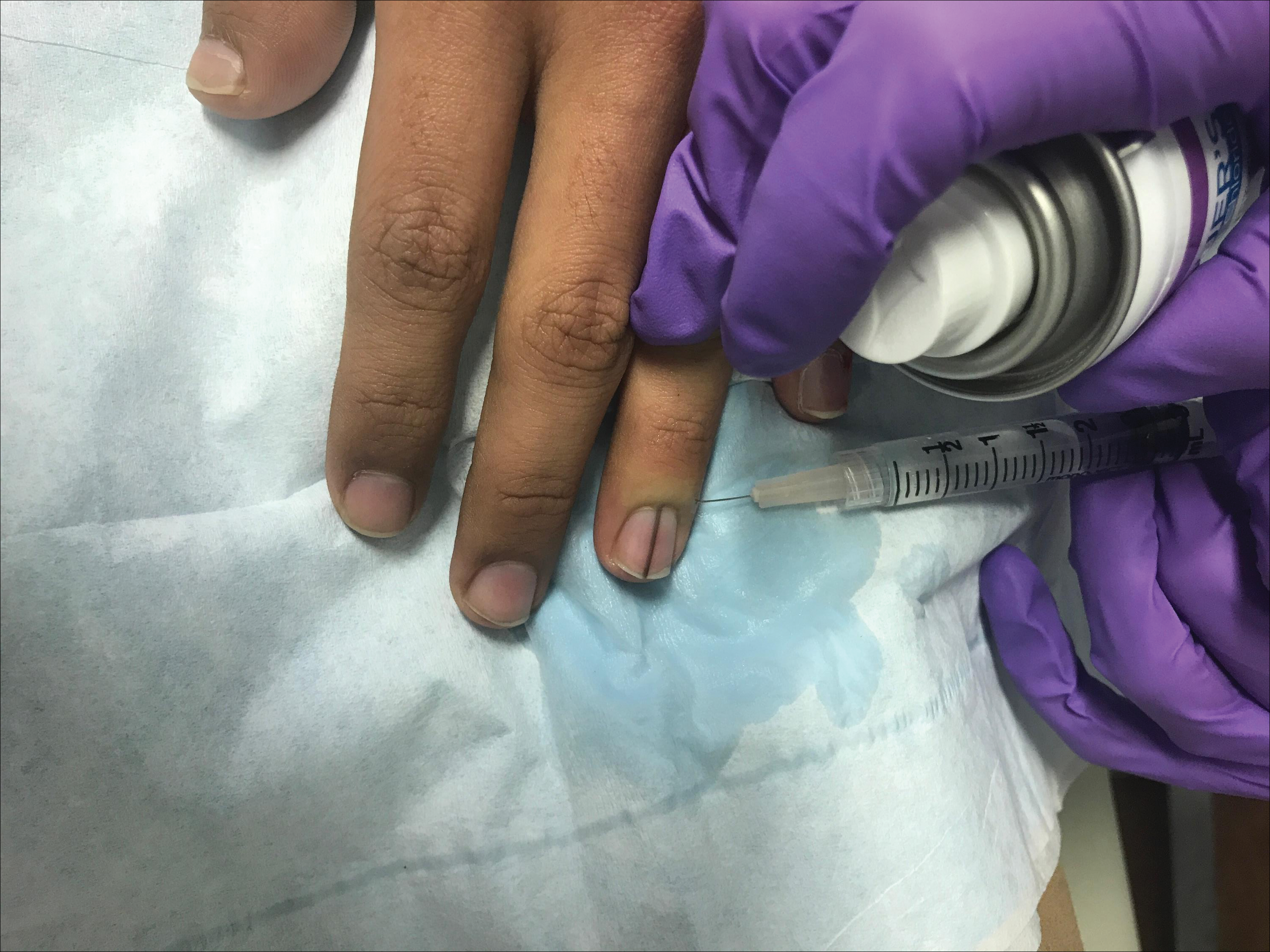

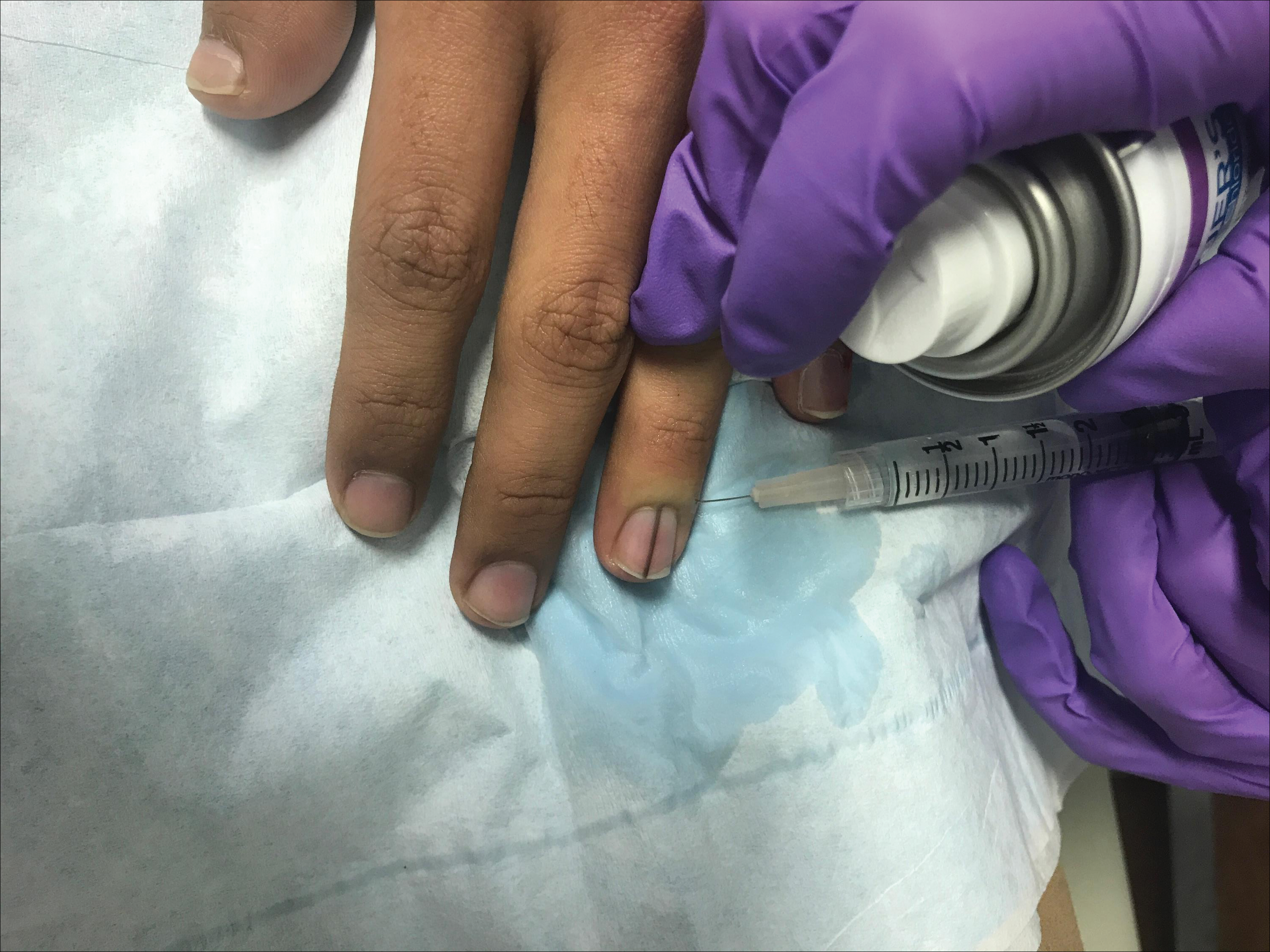

Simple measures can maximize patient comfort during digital anesthesia. Both audiovisual distraction and interpersonal interaction can help to put the patient at ease.6,7 Application of topical anesthetic cream (1–2 hours prior to the procedure under occlusion),8 ice (at least 6 minutes),9 or an ethyl chloride spray can be applied to the nail folds prior to needle insertion to alleviate injection pain, but these methods do little for infiltration pain. Use of an ethyl chloride spray may be the preferred technique due to the rapidity of the analgesic effects (Figure).10 A vibrating massager also can be applied in close proximity to the site of needle insertion.11

Proper anesthetic preparation and technique also can minimize pain during injection. Because lidocaine 1% is acidic (pH, 6.09), buffering with sodium bicarbonate 8.4% can result in decreased injection pain and faster onset of action.6,12 Warming the anesthetic using a water bath, incubator, or autoclave can decrease pain without degradation of lidocaine or epinephrine.13 At a minimum, 30-gauge needles are preferred to minimize pain from needle insertion. Use of 33-gauge needles has shown benefit for injecting the face and scalp and may prove to be helpful injecting sensitive areas such as the digits.14 A slow injection technique is more comfortable for the patient, as rapid injection causes tissue distention.11

The ideal anesthetic for nail surgery would have a fast onset and a long duration of action, which would allow for shorter operation time as well as alleviation of pain postprocedure and some degree of vasoconstriction to help maintain a bloodless field. Lidocaine has the fastest time of onset (<1–3 minutes) but a short duration of action (30–120 minutes) and a vasodilatory effect. Bupivacaine takes 2 to 5 minutes to take effect and has a long duration of action (120–240 minutes) but a risk for cardiotoxicity. Ropivacaine is the preferred anesthetic by some nail surgeons because of its intermediate time of onset (1–15 minutes), long duration of action (120–360 minutes), and the benefit of some vasoconstriction.5,15 The addition of epinephrine has 2 main advantages: vasoconstriction and prolongation of anesthetic effects; the latter may help to alleviate postoperative pain. If there are no contraindications to its use (ie, severe hypertension, Raynaud phenomenon), it can be used safely in digital anesthesia without risk for ischemia or infarction.11

Digital anesthesia can be achieved by infiltration or using nerve blocks. One major difference between these 2 approaches is the time of onset of anesthesia, with the former being nearly instantaneous and the latter taking up to 15 minutes.16 There also usually is more prolonged pain at the site of needle insertion with nerve blocks compared to infiltration. The type of nail surgery being performed, the digit involved, and surgeon preference will determine the anesthetic method of choice.17

Pain management immediately following the procedure and for several days after is essential. Use of a longer-acting anesthetic, such as bupivacaine or ropivacaine, will provide anesthesia for several hours. A well-padded dressing serves to absorb blood and protect the nail and distal digit from trauma, as even minor trauma can exacerbate pain and bleeding. The patient should be instructed to apply ice to the surgical site and keep the ipsilateral extremity elevated for the next 2 days to reduce edema and pain.15 Written instructions are helpful, as anxiety during and after the procedure may limit the patient’s understanding and recollection of the verbal postoperative instructions. To maximize readability of the information, the National Institutes of Health and American Medical Association recommend that the instructions be written at a fourth- to sixth-grade reading level.18,19

A single dose of ibuprofen (400 mg) or acetaminophen (500 mg to 1 g) immediately before or after the procedure can reduce opioid use and postoperative pain.20 Gabapentin (300–1200 mg) given 1 to 2 hours before surgery may be considered in patients who are at high risk for postsurgical pain.21 Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, ibuprofen [200–400 mg]) administered every 4 to 6 hours provides considerable pain reduction postprocedure. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be superior to acetaminophen for pain control22 and carry a low risk for postoperative bleeding.23 Additionally, a combination of acetaminophen with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for 3 doses may be more effective than either drug alone.24 Some patients may require an opioid combination, such as codeine plus acetaminophen, for a short time (up to 3 days) for pain relief following surgery. Excessive pain or pain lasting than more than 3 days is not normal or expected; in these cases, patients should return to the office to rule out ischemia or infection.

It is important to implement pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgeries. Because many of these approaches are derived from other surgical specialties, well-controlled clinical trials in patients undergoing nail surgery will be necessary to improve outcomes.

- Goktay F, Altan ZM, Talas A, et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing nail surgery and skin punch biopsy: effects of age, gender, educational status, and previous experience. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:35-39.

- Ravitskiy L, Phillips PK, Roenigk RK, et al. The use of oral midazolam for perioperative anxiolysis of healthy patients undergoing Mohs surgery: conclusions from randomized controlled and prospective studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:310-322.

- Richert B. Anesthesia of the nail apparatus. In: Richert B, Di Chiacchio N, Haneke E, eds. Nail Surgery. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2010:24-30.

- Egekvist H, Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Pain and mechanical injury of human skin following needle insertions. Eur J Pain. 1999;3:41-49.

- Soriano TT, Beynet DP. Anesthesia and analgesia. In: Robinson J, Hanke CW, Siegel D, et al, eds. Surgery of the Skin. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2010:43-63.

- Strazar AR, Leynes PG, Lalonde DH. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:675-684.

- Drahota A, Galloway E, Stores R, et al. Audiovisual distraction as an adjunct to pain and anxiety relief during minor surgery. Foot (Edinb). 2008;18:211-219.

- Browne J, Fung M, Donnelly M, et al. The use of EMLA reduces the pain associated with digital ring block for ingrowing toenail correction. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000;17:182-184.

- Hayward SC, Landorf KB, Redmond AC. Ice reduces needle-stick pain associated with a digital nerve block of the hallux. Foot. 2006;16:145-148.

- Kose O, Saylan S, Ediz N, et al. Effects of topical alkane vapocoolant spray on pain intensity prior to digital nerve block for ingrown nail surgery. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010;3:73-75.

- Jellinek NJ, Velez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:265-271.

- Strazar R, Lalonde D. Minimizing injection pain in local anesthesia. CMAJ. 2012;184:2016.

- Hogan ME, vanderVaart S, Perampaladas K, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of warming local anesthetics on injection pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:86-98.e1.

- Zelickson BR, Goldberg LH, Rubenzik MK, et al. Finer needles reduce pain associated with injection of local anesthetic using a minimal insertion injection technique [published online October 6, 2017]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001279.

- Haneke E. Nail surgery. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:516-525.

- Vinycomb TI, Sahhar LJ. Comparison of local anesthetics for digital nerve blocks: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:744-51.e5.

- Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: practical tips and treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:68-74.

- How to write easy-to-read health materials. Medline Plus website. https://medlineplus.gov/etr.html. Updated June 28, 2017.

Accessed January 29, 2018. - Weis BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Foundation, American Medical Association; 2003.

- Rosero EB, Joshi GP. Preemptive, preventive, multimodal analgesia: what do they really mean? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4 suppl 2):85S-93S.

- Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults [published online May 12 2010]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008183.pub2.

- Bailey E, Worthington H, Coulthard P. Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth, a Cochrane systematic review. Br Dent J. 2014;216:451-455.

- Glass JS, Hardy CL, Meeks NM, et al. Acute pain management in dermatology: risk assessment and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:543-560; quiz 561-562.

- Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-1013.

Nail surgery is an important part of dermatologic training and clinical practice, both for diagnosis and treatment of nail disorders as well as benign and malignant nail tumors. Patient comfort is essential prior to the procedure and while administering local anesthetics. Effective anesthesia facilitates nail unit biopsies, excisions, and other surgical nail procedures. Pain management immediately following the procedure and during the postoperative period are equally important.

Patients who undergo nail surgery may experience anxiety due to fear of a cancer diagnosis, pain during the surgery, or disfigurement from the procedure. This anxiety may lead to increased blood pressure, a decreased pain threshold, and mental and physical discomfort.1 A detailed explanation of the procedure itself as well as expectations following the surgery are helpful in diminishing these fears. Administration of a fast-acting benzodiazepine also may be helpful in these patients to decrease anxiety prior to the procedure.2

Attaining adequate anesthesia requires an understanding of digital anatomy, particularly innervation. Innervation of the digits is supplied by the volar and dorsal nerves, which divide into 3 branches at the distal interphalangeal joint, innervating the nail bed, the digital tip, and the pulp.3 Pacinian and Ruffini corpuscles and free-ended nociceptors activate nerve fibers that transmit pain impulses.4,5 Local anesthetics block pain transmission by impeding voltage-gated sodium channels located at free nerve endings. Pain from anesthesia may be due to both needle insertion and fluid infiltration.

Simple measures can maximize patient comfort during digital anesthesia. Both audiovisual distraction and interpersonal interaction can help to put the patient at ease.6,7 Application of topical anesthetic cream (1–2 hours prior to the procedure under occlusion),8 ice (at least 6 minutes),9 or an ethyl chloride spray can be applied to the nail folds prior to needle insertion to alleviate injection pain, but these methods do little for infiltration pain. Use of an ethyl chloride spray may be the preferred technique due to the rapidity of the analgesic effects (Figure).10 A vibrating massager also can be applied in close proximity to the site of needle insertion.11

Proper anesthetic preparation and technique also can minimize pain during injection. Because lidocaine 1% is acidic (pH, 6.09), buffering with sodium bicarbonate 8.4% can result in decreased injection pain and faster onset of action.6,12 Warming the anesthetic using a water bath, incubator, or autoclave can decrease pain without degradation of lidocaine or epinephrine.13 At a minimum, 30-gauge needles are preferred to minimize pain from needle insertion. Use of 33-gauge needles has shown benefit for injecting the face and scalp and may prove to be helpful injecting sensitive areas such as the digits.14 A slow injection technique is more comfortable for the patient, as rapid injection causes tissue distention.11

The ideal anesthetic for nail surgery would have a fast onset and a long duration of action, which would allow for shorter operation time as well as alleviation of pain postprocedure and some degree of vasoconstriction to help maintain a bloodless field. Lidocaine has the fastest time of onset (<1–3 minutes) but a short duration of action (30–120 minutes) and a vasodilatory effect. Bupivacaine takes 2 to 5 minutes to take effect and has a long duration of action (120–240 minutes) but a risk for cardiotoxicity. Ropivacaine is the preferred anesthetic by some nail surgeons because of its intermediate time of onset (1–15 minutes), long duration of action (120–360 minutes), and the benefit of some vasoconstriction.5,15 The addition of epinephrine has 2 main advantages: vasoconstriction and prolongation of anesthetic effects; the latter may help to alleviate postoperative pain. If there are no contraindications to its use (ie, severe hypertension, Raynaud phenomenon), it can be used safely in digital anesthesia without risk for ischemia or infarction.11

Digital anesthesia can be achieved by infiltration or using nerve blocks. One major difference between these 2 approaches is the time of onset of anesthesia, with the former being nearly instantaneous and the latter taking up to 15 minutes.16 There also usually is more prolonged pain at the site of needle insertion with nerve blocks compared to infiltration. The type of nail surgery being performed, the digit involved, and surgeon preference will determine the anesthetic method of choice.17

Pain management immediately following the procedure and for several days after is essential. Use of a longer-acting anesthetic, such as bupivacaine or ropivacaine, will provide anesthesia for several hours. A well-padded dressing serves to absorb blood and protect the nail and distal digit from trauma, as even minor trauma can exacerbate pain and bleeding. The patient should be instructed to apply ice to the surgical site and keep the ipsilateral extremity elevated for the next 2 days to reduce edema and pain.15 Written instructions are helpful, as anxiety during and after the procedure may limit the patient’s understanding and recollection of the verbal postoperative instructions. To maximize readability of the information, the National Institutes of Health and American Medical Association recommend that the instructions be written at a fourth- to sixth-grade reading level.18,19

A single dose of ibuprofen (400 mg) or acetaminophen (500 mg to 1 g) immediately before or after the procedure can reduce opioid use and postoperative pain.20 Gabapentin (300–1200 mg) given 1 to 2 hours before surgery may be considered in patients who are at high risk for postsurgical pain.21 Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, ibuprofen [200–400 mg]) administered every 4 to 6 hours provides considerable pain reduction postprocedure. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be superior to acetaminophen for pain control22 and carry a low risk for postoperative bleeding.23 Additionally, a combination of acetaminophen with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for 3 doses may be more effective than either drug alone.24 Some patients may require an opioid combination, such as codeine plus acetaminophen, for a short time (up to 3 days) for pain relief following surgery. Excessive pain or pain lasting than more than 3 days is not normal or expected; in these cases, patients should return to the office to rule out ischemia or infection.

It is important to implement pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgeries. Because many of these approaches are derived from other surgical specialties, well-controlled clinical trials in patients undergoing nail surgery will be necessary to improve outcomes.

Nail surgery is an important part of dermatologic training and clinical practice, both for diagnosis and treatment of nail disorders as well as benign and malignant nail tumors. Patient comfort is essential prior to the procedure and while administering local anesthetics. Effective anesthesia facilitates nail unit biopsies, excisions, and other surgical nail procedures. Pain management immediately following the procedure and during the postoperative period are equally important.

Patients who undergo nail surgery may experience anxiety due to fear of a cancer diagnosis, pain during the surgery, or disfigurement from the procedure. This anxiety may lead to increased blood pressure, a decreased pain threshold, and mental and physical discomfort.1 A detailed explanation of the procedure itself as well as expectations following the surgery are helpful in diminishing these fears. Administration of a fast-acting benzodiazepine also may be helpful in these patients to decrease anxiety prior to the procedure.2

Attaining adequate anesthesia requires an understanding of digital anatomy, particularly innervation. Innervation of the digits is supplied by the volar and dorsal nerves, which divide into 3 branches at the distal interphalangeal joint, innervating the nail bed, the digital tip, and the pulp.3 Pacinian and Ruffini corpuscles and free-ended nociceptors activate nerve fibers that transmit pain impulses.4,5 Local anesthetics block pain transmission by impeding voltage-gated sodium channels located at free nerve endings. Pain from anesthesia may be due to both needle insertion and fluid infiltration.

Simple measures can maximize patient comfort during digital anesthesia. Both audiovisual distraction and interpersonal interaction can help to put the patient at ease.6,7 Application of topical anesthetic cream (1–2 hours prior to the procedure under occlusion),8 ice (at least 6 minutes),9 or an ethyl chloride spray can be applied to the nail folds prior to needle insertion to alleviate injection pain, but these methods do little for infiltration pain. Use of an ethyl chloride spray may be the preferred technique due to the rapidity of the analgesic effects (Figure).10 A vibrating massager also can be applied in close proximity to the site of needle insertion.11

Proper anesthetic preparation and technique also can minimize pain during injection. Because lidocaine 1% is acidic (pH, 6.09), buffering with sodium bicarbonate 8.4% can result in decreased injection pain and faster onset of action.6,12 Warming the anesthetic using a water bath, incubator, or autoclave can decrease pain without degradation of lidocaine or epinephrine.13 At a minimum, 30-gauge needles are preferred to minimize pain from needle insertion. Use of 33-gauge needles has shown benefit for injecting the face and scalp and may prove to be helpful injecting sensitive areas such as the digits.14 A slow injection technique is more comfortable for the patient, as rapid injection causes tissue distention.11

The ideal anesthetic for nail surgery would have a fast onset and a long duration of action, which would allow for shorter operation time as well as alleviation of pain postprocedure and some degree of vasoconstriction to help maintain a bloodless field. Lidocaine has the fastest time of onset (<1–3 minutes) but a short duration of action (30–120 minutes) and a vasodilatory effect. Bupivacaine takes 2 to 5 minutes to take effect and has a long duration of action (120–240 minutes) but a risk for cardiotoxicity. Ropivacaine is the preferred anesthetic by some nail surgeons because of its intermediate time of onset (1–15 minutes), long duration of action (120–360 minutes), and the benefit of some vasoconstriction.5,15 The addition of epinephrine has 2 main advantages: vasoconstriction and prolongation of anesthetic effects; the latter may help to alleviate postoperative pain. If there are no contraindications to its use (ie, severe hypertension, Raynaud phenomenon), it can be used safely in digital anesthesia without risk for ischemia or infarction.11

Digital anesthesia can be achieved by infiltration or using nerve blocks. One major difference between these 2 approaches is the time of onset of anesthesia, with the former being nearly instantaneous and the latter taking up to 15 minutes.16 There also usually is more prolonged pain at the site of needle insertion with nerve blocks compared to infiltration. The type of nail surgery being performed, the digit involved, and surgeon preference will determine the anesthetic method of choice.17

Pain management immediately following the procedure and for several days after is essential. Use of a longer-acting anesthetic, such as bupivacaine or ropivacaine, will provide anesthesia for several hours. A well-padded dressing serves to absorb blood and protect the nail and distal digit from trauma, as even minor trauma can exacerbate pain and bleeding. The patient should be instructed to apply ice to the surgical site and keep the ipsilateral extremity elevated for the next 2 days to reduce edema and pain.15 Written instructions are helpful, as anxiety during and after the procedure may limit the patient’s understanding and recollection of the verbal postoperative instructions. To maximize readability of the information, the National Institutes of Health and American Medical Association recommend that the instructions be written at a fourth- to sixth-grade reading level.18,19

A single dose of ibuprofen (400 mg) or acetaminophen (500 mg to 1 g) immediately before or after the procedure can reduce opioid use and postoperative pain.20 Gabapentin (300–1200 mg) given 1 to 2 hours before surgery may be considered in patients who are at high risk for postsurgical pain.21 Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, ibuprofen [200–400 mg]) administered every 4 to 6 hours provides considerable pain reduction postprocedure. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be superior to acetaminophen for pain control22 and carry a low risk for postoperative bleeding.23 Additionally, a combination of acetaminophen with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for 3 doses may be more effective than either drug alone.24 Some patients may require an opioid combination, such as codeine plus acetaminophen, for a short time (up to 3 days) for pain relief following surgery. Excessive pain or pain lasting than more than 3 days is not normal or expected; in these cases, patients should return to the office to rule out ischemia or infection.

It is important to implement pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgeries. Because many of these approaches are derived from other surgical specialties, well-controlled clinical trials in patients undergoing nail surgery will be necessary to improve outcomes.

- Goktay F, Altan ZM, Talas A, et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing nail surgery and skin punch biopsy: effects of age, gender, educational status, and previous experience. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:35-39.

- Ravitskiy L, Phillips PK, Roenigk RK, et al. The use of oral midazolam for perioperative anxiolysis of healthy patients undergoing Mohs surgery: conclusions from randomized controlled and prospective studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:310-322.

- Richert B. Anesthesia of the nail apparatus. In: Richert B, Di Chiacchio N, Haneke E, eds. Nail Surgery. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2010:24-30.

- Egekvist H, Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Pain and mechanical injury of human skin following needle insertions. Eur J Pain. 1999;3:41-49.

- Soriano TT, Beynet DP. Anesthesia and analgesia. In: Robinson J, Hanke CW, Siegel D, et al, eds. Surgery of the Skin. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2010:43-63.

- Strazar AR, Leynes PG, Lalonde DH. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:675-684.

- Drahota A, Galloway E, Stores R, et al. Audiovisual distraction as an adjunct to pain and anxiety relief during minor surgery. Foot (Edinb). 2008;18:211-219.

- Browne J, Fung M, Donnelly M, et al. The use of EMLA reduces the pain associated with digital ring block for ingrowing toenail correction. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000;17:182-184.

- Hayward SC, Landorf KB, Redmond AC. Ice reduces needle-stick pain associated with a digital nerve block of the hallux. Foot. 2006;16:145-148.

- Kose O, Saylan S, Ediz N, et al. Effects of topical alkane vapocoolant spray on pain intensity prior to digital nerve block for ingrown nail surgery. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010;3:73-75.

- Jellinek NJ, Velez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:265-271.

- Strazar R, Lalonde D. Minimizing injection pain in local anesthesia. CMAJ. 2012;184:2016.

- Hogan ME, vanderVaart S, Perampaladas K, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of warming local anesthetics on injection pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:86-98.e1.

- Zelickson BR, Goldberg LH, Rubenzik MK, et al. Finer needles reduce pain associated with injection of local anesthetic using a minimal insertion injection technique [published online October 6, 2017]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001279.

- Haneke E. Nail surgery. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:516-525.

- Vinycomb TI, Sahhar LJ. Comparison of local anesthetics for digital nerve blocks: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:744-51.e5.

- Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: practical tips and treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:68-74.

- How to write easy-to-read health materials. Medline Plus website. https://medlineplus.gov/etr.html. Updated June 28, 2017.

Accessed January 29, 2018. - Weis BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Foundation, American Medical Association; 2003.

- Rosero EB, Joshi GP. Preemptive, preventive, multimodal analgesia: what do they really mean? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4 suppl 2):85S-93S.

- Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults [published online May 12 2010]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008183.pub2.

- Bailey E, Worthington H, Coulthard P. Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth, a Cochrane systematic review. Br Dent J. 2014;216:451-455.

- Glass JS, Hardy CL, Meeks NM, et al. Acute pain management in dermatology: risk assessment and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:543-560; quiz 561-562.

- Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-1013.

- Goktay F, Altan ZM, Talas A, et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing nail surgery and skin punch biopsy: effects of age, gender, educational status, and previous experience. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:35-39.

- Ravitskiy L, Phillips PK, Roenigk RK, et al. The use of oral midazolam for perioperative anxiolysis of healthy patients undergoing Mohs surgery: conclusions from randomized controlled and prospective studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:310-322.

- Richert B. Anesthesia of the nail apparatus. In: Richert B, Di Chiacchio N, Haneke E, eds. Nail Surgery. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2010:24-30.

- Egekvist H, Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Pain and mechanical injury of human skin following needle insertions. Eur J Pain. 1999;3:41-49.

- Soriano TT, Beynet DP. Anesthesia and analgesia. In: Robinson J, Hanke CW, Siegel D, et al, eds. Surgery of the Skin. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2010:43-63.

- Strazar AR, Leynes PG, Lalonde DH. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:675-684.

- Drahota A, Galloway E, Stores R, et al. Audiovisual distraction as an adjunct to pain and anxiety relief during minor surgery. Foot (Edinb). 2008;18:211-219.

- Browne J, Fung M, Donnelly M, et al. The use of EMLA reduces the pain associated with digital ring block for ingrowing toenail correction. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000;17:182-184.

- Hayward SC, Landorf KB, Redmond AC. Ice reduces needle-stick pain associated with a digital nerve block of the hallux. Foot. 2006;16:145-148.

- Kose O, Saylan S, Ediz N, et al. Effects of topical alkane vapocoolant spray on pain intensity prior to digital nerve block for ingrown nail surgery. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010;3:73-75.

- Jellinek NJ, Velez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:265-271.

- Strazar R, Lalonde D. Minimizing injection pain in local anesthesia. CMAJ. 2012;184:2016.

- Hogan ME, vanderVaart S, Perampaladas K, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of warming local anesthetics on injection pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:86-98.e1.

- Zelickson BR, Goldberg LH, Rubenzik MK, et al. Finer needles reduce pain associated with injection of local anesthetic using a minimal insertion injection technique [published online October 6, 2017]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001279.

- Haneke E. Nail surgery. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:516-525.

- Vinycomb TI, Sahhar LJ. Comparison of local anesthetics for digital nerve blocks: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:744-51.e5.

- Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: practical tips and treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:68-74.

- How to write easy-to-read health materials. Medline Plus website. https://medlineplus.gov/etr.html. Updated June 28, 2017.

Accessed January 29, 2018. - Weis BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Foundation, American Medical Association; 2003.

- Rosero EB, Joshi GP. Preemptive, preventive, multimodal analgesia: what do they really mean? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4 suppl 2):85S-93S.

- Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults [published online May 12 2010]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008183.pub2.

- Bailey E, Worthington H, Coulthard P. Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth, a Cochrane systematic review. Br Dent J. 2014;216:451-455.

- Glass JS, Hardy CL, Meeks NM, et al. Acute pain management in dermatology: risk assessment and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:543-560; quiz 561-562.

- Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-1013.

MS: Past, Present, and Future

Stuart D. Cook, MD, and Abdul Rahman Alchaki

Dr. Cook is the Ruth Dunietz Kushner and Michael Jay Serwitz Professor of Neurology/Neurosciences at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Newark. Dr. Alchaki is a resident in the Deptartment of Neurology/Neurosciences at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Newark.

Disclosure: Stuart Cook has received honoraria for lectures from Bayer HealthCare and Merck Serono. He has served as a consultant for Merck Serono, Bayer HealthCare, Teva, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Biogen Idec, and Actinobac Biomed. He has served on steering committees for the BEYOND and CLARITY Studies and as a member of Advisory Boards for Merck Serono, Bayer HealthCare, Teva, Biogen Idec, Sanofi Aventis, and Actinobac Biomed.

The Initial Years (1838 to 1930s)