User login

Inaccurate depictions of inpatient psychiatry foster stigma

When it comes to the portrayal of physicians in popular culture, psychiatrists are second only to surgeons.1 Far too often, these portrayals of psychiatry have misrepresented our specialty – and stigmatized our patients. Some of the content produced by entertainment giants Netflix and Marvel is a case in point.

That Netflix-Marvel collaboration has proven fruitful, resulting in six television series spanning seven seasons of entertainment to date. Last year alone saw the release of three Netflix-Marvel productions, including Marvel’s “Iron Fist” in March, “The Defenders” in August, and “The Punisher” in November. Given the popularity and ease of streaming Marvel’s Netflix productions, these series have the potential to entertain and inform a wide audience. Unfortunately, however, part of their influence might be to perpetuate stigma and fear surrounding inpatient psychiatric care. Take the inaccurate portrayal of psychiatry in “Iron Fist” compared with the reality of modern psychiatric care, for example.

While hospitalized, Danny is repeatedly shown in restraints, including four-point restraints, a belt, and a straitjacket. The use of restraints is sometimes portrayed as unprovoked, without evidence of aggression on the part of Danny. In addition, it appears that he is left in restraints for extended periods of time, as he is shown, for example, waking up in the night still restrained. While the use of restraints may be warranted in instances of extreme aggression or violence, the current culture of inpatient psychiatric care has shifted toward safely minimizing the use of restraints and seclusion.2 Straitjackets might be an icon of a bygone era of psychiatric care, but they no longer are a mainstream form of restraint used in the United States. Modern best practices would not result in a nonthreatening patient being placed in restraints and left in them for an extended period of time as shown in “Iron Fist.”

Danny is shown being forcibly administered medications, even in nonthreatening situations. These medications are given via parenteral injection as well as orally, with a psychiatric technician shown roughly inserting a tongue depressor deep in Danny’s mouth, pouring pills into his oral cavity, and manually holding his mouth shut to ensure ingestion. In truth, psychiatric patients are sometimes given intramuscular injections of calming agents when their level of agitation threatens to harm others or themselves. For patients to be given an involuntary injection when not acutely threatening, typically states require some form of legal application for forced medication (a process that does not appear to have been observed in “Iron Fist”). As we know, forced oral medications never should be undertaken given the significant risk to patient (possible choking) as well as staff (bitten fingers).

Staff supervision of patients at the fictional Birch Psychiatric Hospital is extremely poor. At one point, a fellow patient enters Danny’s room dressed in a white coat, pretending to be his doctor. As the conversation progresses, the patient grabs a fork from Danny’s food tray and holds it to his throat, threatening to kill him before being gruffly dragged off by hospital staff. At another point, Danny is shown in four-point restraints, and a patient simply walks into his room and removes the restraints for him. By contrast, in a real, modern inpatient psychiatric facility unit, staff would be routinely providing safety checks on patients throughout the day. If a patient is at risk for violence, sharp metal cutlery would not be included on accessible food trays. Patient attire would be subject to hospital inspection and approval, so it is unclear how or where a patient would have access to a physician’s coat to pull off such an impersonation. And finally, if a patient were sufficiently agitated to require the use of four-point restraints, he or she would be closely supervised and not left alone in an open area where other patients could remove the restraints.

The hospital stays described in “Iron Fist” are very long, and it is strongly implied that psychiatric diagnoses are invented to prolong inpatient care indefinitely. Referring to the duration of his initial involuntary hold, one patient tells Danny: “That what they tell you? Seventy-two hours? (laughs) Me, I had a little incident inside a pharmacy. Seventy-two hours later, I’m a bipolar with mixed affective episodes layered atop a substance abuse disorder. That was 2 years ago. Billy was living under a bridge. Seventy-two hours later, he’s a paranoid personality disorder. That was just over a year ago. And Jimmy was screaming at people in Times Square. Seventy-two hours later, he’s a schizoaffective disorder. He’s been here almost 15 years. Don’t think you’ll be any different.”

Most modern inpatient psychiatric care is designed around short-term hospitalization (days to weeks rather than months to years) with a goal of reintegrating patients back into the community with ongoing outpatient care as soon as they can safely make that transition. In addition, to insinuate that psychiatrists invent diagnoses to keep patients “locked up” insults the integrity of the many dedicated mental health workers who provide care for an ill and often overlooked population.

The most egregious examples of poor psychiatric care portrayed in “Iron Fist” involve illegal or criminal activities. Video cameras placed throughout the hospital transmit a live feed to a shadowy figure who has no role in patient care. A psychiatric technician escorts Danny to a room full of patients hired to kill him. These particular concerns are outlandish enough that perhaps they don’t even need to be directly addressed, but for the sake of completeness it is worth noting that psychiatric hospitals are subject to rigorous oversight from numerous regulatory bodies to ensure that patient care is delivered in a safe and respectable manner and that all protected health information is accessible only by those whose treatment role necessitates such access.

Marvel’s “Iron Fist” seeks to entertain its audience, but it does a poor job of showing viewers a realistic portrayal of inpatient psychiatric care. The show presents a psychiatric hospital as the setting for inappropriate use of restraints, unwarranted use of forced oral and injectable medications, a lack of supervision leading to violence between patients, and even attempted murder accommodated by a hospital employee. Also, the show strongly implies that psychiatric diagnoses are invented for the purpose of continuing inpatient care indefinitely.

In sum, the psychiatric hospital is seen as an inhumane form of imprisonment from which one can only hope to escape with the benefit of a glowing, magical fist. Although this is fiction, these kinds of narratives can have very real consequences in perpetuating stigma against psychiatric care. Ultimately, such storylines undermine the public’s confidence in clinicians seeking to provide caring and compassionate care.

Dr. Weber is psychiatry department chair at Logan (Utah) Regional Hospital with Intermountain Healthcare.

References

1 J Nat Med Assoc. 2002 Jul. 94[7]:635-58.

2 Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;34:139-46.

When it comes to the portrayal of physicians in popular culture, psychiatrists are second only to surgeons.1 Far too often, these portrayals of psychiatry have misrepresented our specialty – and stigmatized our patients. Some of the content produced by entertainment giants Netflix and Marvel is a case in point.

That Netflix-Marvel collaboration has proven fruitful, resulting in six television series spanning seven seasons of entertainment to date. Last year alone saw the release of three Netflix-Marvel productions, including Marvel’s “Iron Fist” in March, “The Defenders” in August, and “The Punisher” in November. Given the popularity and ease of streaming Marvel’s Netflix productions, these series have the potential to entertain and inform a wide audience. Unfortunately, however, part of their influence might be to perpetuate stigma and fear surrounding inpatient psychiatric care. Take the inaccurate portrayal of psychiatry in “Iron Fist” compared with the reality of modern psychiatric care, for example.

While hospitalized, Danny is repeatedly shown in restraints, including four-point restraints, a belt, and a straitjacket. The use of restraints is sometimes portrayed as unprovoked, without evidence of aggression on the part of Danny. In addition, it appears that he is left in restraints for extended periods of time, as he is shown, for example, waking up in the night still restrained. While the use of restraints may be warranted in instances of extreme aggression or violence, the current culture of inpatient psychiatric care has shifted toward safely minimizing the use of restraints and seclusion.2 Straitjackets might be an icon of a bygone era of psychiatric care, but they no longer are a mainstream form of restraint used in the United States. Modern best practices would not result in a nonthreatening patient being placed in restraints and left in them for an extended period of time as shown in “Iron Fist.”

Danny is shown being forcibly administered medications, even in nonthreatening situations. These medications are given via parenteral injection as well as orally, with a psychiatric technician shown roughly inserting a tongue depressor deep in Danny’s mouth, pouring pills into his oral cavity, and manually holding his mouth shut to ensure ingestion. In truth, psychiatric patients are sometimes given intramuscular injections of calming agents when their level of agitation threatens to harm others or themselves. For patients to be given an involuntary injection when not acutely threatening, typically states require some form of legal application for forced medication (a process that does not appear to have been observed in “Iron Fist”). As we know, forced oral medications never should be undertaken given the significant risk to patient (possible choking) as well as staff (bitten fingers).

Staff supervision of patients at the fictional Birch Psychiatric Hospital is extremely poor. At one point, a fellow patient enters Danny’s room dressed in a white coat, pretending to be his doctor. As the conversation progresses, the patient grabs a fork from Danny’s food tray and holds it to his throat, threatening to kill him before being gruffly dragged off by hospital staff. At another point, Danny is shown in four-point restraints, and a patient simply walks into his room and removes the restraints for him. By contrast, in a real, modern inpatient psychiatric facility unit, staff would be routinely providing safety checks on patients throughout the day. If a patient is at risk for violence, sharp metal cutlery would not be included on accessible food trays. Patient attire would be subject to hospital inspection and approval, so it is unclear how or where a patient would have access to a physician’s coat to pull off such an impersonation. And finally, if a patient were sufficiently agitated to require the use of four-point restraints, he or she would be closely supervised and not left alone in an open area where other patients could remove the restraints.

The hospital stays described in “Iron Fist” are very long, and it is strongly implied that psychiatric diagnoses are invented to prolong inpatient care indefinitely. Referring to the duration of his initial involuntary hold, one patient tells Danny: “That what they tell you? Seventy-two hours? (laughs) Me, I had a little incident inside a pharmacy. Seventy-two hours later, I’m a bipolar with mixed affective episodes layered atop a substance abuse disorder. That was 2 years ago. Billy was living under a bridge. Seventy-two hours later, he’s a paranoid personality disorder. That was just over a year ago. And Jimmy was screaming at people in Times Square. Seventy-two hours later, he’s a schizoaffective disorder. He’s been here almost 15 years. Don’t think you’ll be any different.”

Most modern inpatient psychiatric care is designed around short-term hospitalization (days to weeks rather than months to years) with a goal of reintegrating patients back into the community with ongoing outpatient care as soon as they can safely make that transition. In addition, to insinuate that psychiatrists invent diagnoses to keep patients “locked up” insults the integrity of the many dedicated mental health workers who provide care for an ill and often overlooked population.

The most egregious examples of poor psychiatric care portrayed in “Iron Fist” involve illegal or criminal activities. Video cameras placed throughout the hospital transmit a live feed to a shadowy figure who has no role in patient care. A psychiatric technician escorts Danny to a room full of patients hired to kill him. These particular concerns are outlandish enough that perhaps they don’t even need to be directly addressed, but for the sake of completeness it is worth noting that psychiatric hospitals are subject to rigorous oversight from numerous regulatory bodies to ensure that patient care is delivered in a safe and respectable manner and that all protected health information is accessible only by those whose treatment role necessitates such access.

Marvel’s “Iron Fist” seeks to entertain its audience, but it does a poor job of showing viewers a realistic portrayal of inpatient psychiatric care. The show presents a psychiatric hospital as the setting for inappropriate use of restraints, unwarranted use of forced oral and injectable medications, a lack of supervision leading to violence between patients, and even attempted murder accommodated by a hospital employee. Also, the show strongly implies that psychiatric diagnoses are invented for the purpose of continuing inpatient care indefinitely.

In sum, the psychiatric hospital is seen as an inhumane form of imprisonment from which one can only hope to escape with the benefit of a glowing, magical fist. Although this is fiction, these kinds of narratives can have very real consequences in perpetuating stigma against psychiatric care. Ultimately, such storylines undermine the public’s confidence in clinicians seeking to provide caring and compassionate care.

Dr. Weber is psychiatry department chair at Logan (Utah) Regional Hospital with Intermountain Healthcare.

References

1 J Nat Med Assoc. 2002 Jul. 94[7]:635-58.

2 Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;34:139-46.

When it comes to the portrayal of physicians in popular culture, psychiatrists are second only to surgeons.1 Far too often, these portrayals of psychiatry have misrepresented our specialty – and stigmatized our patients. Some of the content produced by entertainment giants Netflix and Marvel is a case in point.

That Netflix-Marvel collaboration has proven fruitful, resulting in six television series spanning seven seasons of entertainment to date. Last year alone saw the release of three Netflix-Marvel productions, including Marvel’s “Iron Fist” in March, “The Defenders” in August, and “The Punisher” in November. Given the popularity and ease of streaming Marvel’s Netflix productions, these series have the potential to entertain and inform a wide audience. Unfortunately, however, part of their influence might be to perpetuate stigma and fear surrounding inpatient psychiatric care. Take the inaccurate portrayal of psychiatry in “Iron Fist” compared with the reality of modern psychiatric care, for example.

While hospitalized, Danny is repeatedly shown in restraints, including four-point restraints, a belt, and a straitjacket. The use of restraints is sometimes portrayed as unprovoked, without evidence of aggression on the part of Danny. In addition, it appears that he is left in restraints for extended periods of time, as he is shown, for example, waking up in the night still restrained. While the use of restraints may be warranted in instances of extreme aggression or violence, the current culture of inpatient psychiatric care has shifted toward safely minimizing the use of restraints and seclusion.2 Straitjackets might be an icon of a bygone era of psychiatric care, but they no longer are a mainstream form of restraint used in the United States. Modern best practices would not result in a nonthreatening patient being placed in restraints and left in them for an extended period of time as shown in “Iron Fist.”

Danny is shown being forcibly administered medications, even in nonthreatening situations. These medications are given via parenteral injection as well as orally, with a psychiatric technician shown roughly inserting a tongue depressor deep in Danny’s mouth, pouring pills into his oral cavity, and manually holding his mouth shut to ensure ingestion. In truth, psychiatric patients are sometimes given intramuscular injections of calming agents when their level of agitation threatens to harm others or themselves. For patients to be given an involuntary injection when not acutely threatening, typically states require some form of legal application for forced medication (a process that does not appear to have been observed in “Iron Fist”). As we know, forced oral medications never should be undertaken given the significant risk to patient (possible choking) as well as staff (bitten fingers).

Staff supervision of patients at the fictional Birch Psychiatric Hospital is extremely poor. At one point, a fellow patient enters Danny’s room dressed in a white coat, pretending to be his doctor. As the conversation progresses, the patient grabs a fork from Danny’s food tray and holds it to his throat, threatening to kill him before being gruffly dragged off by hospital staff. At another point, Danny is shown in four-point restraints, and a patient simply walks into his room and removes the restraints for him. By contrast, in a real, modern inpatient psychiatric facility unit, staff would be routinely providing safety checks on patients throughout the day. If a patient is at risk for violence, sharp metal cutlery would not be included on accessible food trays. Patient attire would be subject to hospital inspection and approval, so it is unclear how or where a patient would have access to a physician’s coat to pull off such an impersonation. And finally, if a patient were sufficiently agitated to require the use of four-point restraints, he or she would be closely supervised and not left alone in an open area where other patients could remove the restraints.

The hospital stays described in “Iron Fist” are very long, and it is strongly implied that psychiatric diagnoses are invented to prolong inpatient care indefinitely. Referring to the duration of his initial involuntary hold, one patient tells Danny: “That what they tell you? Seventy-two hours? (laughs) Me, I had a little incident inside a pharmacy. Seventy-two hours later, I’m a bipolar with mixed affective episodes layered atop a substance abuse disorder. That was 2 years ago. Billy was living under a bridge. Seventy-two hours later, he’s a paranoid personality disorder. That was just over a year ago. And Jimmy was screaming at people in Times Square. Seventy-two hours later, he’s a schizoaffective disorder. He’s been here almost 15 years. Don’t think you’ll be any different.”

Most modern inpatient psychiatric care is designed around short-term hospitalization (days to weeks rather than months to years) with a goal of reintegrating patients back into the community with ongoing outpatient care as soon as they can safely make that transition. In addition, to insinuate that psychiatrists invent diagnoses to keep patients “locked up” insults the integrity of the many dedicated mental health workers who provide care for an ill and often overlooked population.

The most egregious examples of poor psychiatric care portrayed in “Iron Fist” involve illegal or criminal activities. Video cameras placed throughout the hospital transmit a live feed to a shadowy figure who has no role in patient care. A psychiatric technician escorts Danny to a room full of patients hired to kill him. These particular concerns are outlandish enough that perhaps they don’t even need to be directly addressed, but for the sake of completeness it is worth noting that psychiatric hospitals are subject to rigorous oversight from numerous regulatory bodies to ensure that patient care is delivered in a safe and respectable manner and that all protected health information is accessible only by those whose treatment role necessitates such access.

Marvel’s “Iron Fist” seeks to entertain its audience, but it does a poor job of showing viewers a realistic portrayal of inpatient psychiatric care. The show presents a psychiatric hospital as the setting for inappropriate use of restraints, unwarranted use of forced oral and injectable medications, a lack of supervision leading to violence between patients, and even attempted murder accommodated by a hospital employee. Also, the show strongly implies that psychiatric diagnoses are invented for the purpose of continuing inpatient care indefinitely.

In sum, the psychiatric hospital is seen as an inhumane form of imprisonment from which one can only hope to escape with the benefit of a glowing, magical fist. Although this is fiction, these kinds of narratives can have very real consequences in perpetuating stigma against psychiatric care. Ultimately, such storylines undermine the public’s confidence in clinicians seeking to provide caring and compassionate care.

Dr. Weber is psychiatry department chair at Logan (Utah) Regional Hospital with Intermountain Healthcare.

References

1 J Nat Med Assoc. 2002 Jul. 94[7]:635-58.

2 Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;34:139-46.

Action to address gun violence is long overdue

On Feb. 14 in Parkland, Florida, 17 students and teachers were murdered in yet another school shooting. Yet another mass killing. More than a dozen others were injured and some are fighting for their lives under the care of physicians and nurses.

The pervasiveness of gun violence and the weapons used in these crimes have changed the way we live. In movie theaters, places of worship, offices, restaurants, night clubs and schools, people today make clear note of escape routes. Schools, including the one attacked yesterday, regularly practice for active shooter situations.

And in emergency departments and trauma centers, we struggle with much more complicated, dangerous injuries inflicted by lethal ammunition fired by military-grade weapons.

At the 2016 AMA Annual Meeting, which began the day after the deadly shooting at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, physicians from across the country and at every stage in their career spoke about treating gunshot victims and the scale of violence we are experiencing today. Their stories resonate as much today as they did nearly two years ago.

The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was the 30th mass shooting – a shooting in which four or more people are killed or injured – of 2018. It was also the 17th time a gun has been fired on the grounds of an American school this year. The problem is getting worse – the regularity of, and death from, mass shootings is increasing. With the shooting in Parkland, three of the 10 deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history have come in the past five months.

Time to act

Gun violence in America today is a public health crisis, one that requires a comprehensive and far-reaching solution. And that is not just my own sentiment; that is the determination of the AMA House of Delegates. With more than 30,000 American men, women and children dying from gun violence and firearm-related accidents each year, the time to act is now.

Today, more than ever before, America’s physicians must lend their voice and their considerable political muscle to force lawmakers to examine this urgent health crisis – through federally funded research – and take appropriate steps to address it. Let me be very clear about this. We are not talking about Second Amendment rights or restricting your ability to own a firearm.

We are talking about a public health crisis that our Congress has failed to address. This must end.

In the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012 – a massacre that left 20 first-graders and six adults dead – the AMA wrote to President Obama and to the leaders in the House and Senate. We expressed our sense of grief and sadness and offered our expertise and experience in finding workable, commonsense solutions to reduce the epidemic of gun violence – indeed the overall culture of violence – in America.

We noted that the relatively easy access to the increased firepower of assault weapons, semiautomatic firearms, high-capacity magazines, and high-velocity ammunition heightens the risk of multiple gunshot wounds and severe penetrating trauma, resulting in more critical injuries and deaths. Even for those who manage to survive gun violence involving these weapons, the severity and lasting impact of their wounds, disabilities and treatment leads to devastating consequences for the families affected and for society as a whole, contributing to high medical costs for treatment and recovery.

We called for renewing and strengthening the assault weapons ban, including banning high-capacity magazines, as a step in the right direction. We also called for more resources for safety education programs that promote more responsible use and storage of firearms, and noted that part of ensuring firearms safety means that physicians need to be able to have frank discussions with their patients and parents of patients about firearm safety issues and risks to help them safeguard their families from accidents.

We also urged the nation to strengthen its commitment and resources to comprehensive access to mental health services, including screening, prevention and treatment. While the overwhelming majority of patients with mental illness are not violent, physicians and other health professionals must be trained to respond to those who have a mental illness that might make them more prone to commit violence.

On an average day, more than 100 Americans die from gun violence and firearm-related accidents. In communities like yours – regardless of where you live or how safe it feels – people are losing their lives to this scourge.

For many Americans, gun violence used to be a distant idea relegated mostly to the nightly news, movies and faraway places. But today, in communities such as Parkland, it is horrifyingly real. The victims are our friends, neighbors and, unfathomably, our children.

As physicians, we have dedicated our lives to public health. And at the AMA, our mission is improving the health of the nation. That mission today must include determining the root causes of this epidemic and turning the tide on gun violence.

We must do more than pray for families who lost loved ones. It is time to act to prevent future deaths and injuries.

Dr. Barbe is president of the American Medical Association. His commentary originally was published on AMA Wire.

On Feb. 14 in Parkland, Florida, 17 students and teachers were murdered in yet another school shooting. Yet another mass killing. More than a dozen others were injured and some are fighting for their lives under the care of physicians and nurses.

The pervasiveness of gun violence and the weapons used in these crimes have changed the way we live. In movie theaters, places of worship, offices, restaurants, night clubs and schools, people today make clear note of escape routes. Schools, including the one attacked yesterday, regularly practice for active shooter situations.

And in emergency departments and trauma centers, we struggle with much more complicated, dangerous injuries inflicted by lethal ammunition fired by military-grade weapons.

At the 2016 AMA Annual Meeting, which began the day after the deadly shooting at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, physicians from across the country and at every stage in their career spoke about treating gunshot victims and the scale of violence we are experiencing today. Their stories resonate as much today as they did nearly two years ago.

The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was the 30th mass shooting – a shooting in which four or more people are killed or injured – of 2018. It was also the 17th time a gun has been fired on the grounds of an American school this year. The problem is getting worse – the regularity of, and death from, mass shootings is increasing. With the shooting in Parkland, three of the 10 deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history have come in the past five months.

Time to act

Gun violence in America today is a public health crisis, one that requires a comprehensive and far-reaching solution. And that is not just my own sentiment; that is the determination of the AMA House of Delegates. With more than 30,000 American men, women and children dying from gun violence and firearm-related accidents each year, the time to act is now.

Today, more than ever before, America’s physicians must lend their voice and their considerable political muscle to force lawmakers to examine this urgent health crisis – through federally funded research – and take appropriate steps to address it. Let me be very clear about this. We are not talking about Second Amendment rights or restricting your ability to own a firearm.

We are talking about a public health crisis that our Congress has failed to address. This must end.

In the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012 – a massacre that left 20 first-graders and six adults dead – the AMA wrote to President Obama and to the leaders in the House and Senate. We expressed our sense of grief and sadness and offered our expertise and experience in finding workable, commonsense solutions to reduce the epidemic of gun violence – indeed the overall culture of violence – in America.

We noted that the relatively easy access to the increased firepower of assault weapons, semiautomatic firearms, high-capacity magazines, and high-velocity ammunition heightens the risk of multiple gunshot wounds and severe penetrating trauma, resulting in more critical injuries and deaths. Even for those who manage to survive gun violence involving these weapons, the severity and lasting impact of their wounds, disabilities and treatment leads to devastating consequences for the families affected and for society as a whole, contributing to high medical costs for treatment and recovery.

We called for renewing and strengthening the assault weapons ban, including banning high-capacity magazines, as a step in the right direction. We also called for more resources for safety education programs that promote more responsible use and storage of firearms, and noted that part of ensuring firearms safety means that physicians need to be able to have frank discussions with their patients and parents of patients about firearm safety issues and risks to help them safeguard their families from accidents.

We also urged the nation to strengthen its commitment and resources to comprehensive access to mental health services, including screening, prevention and treatment. While the overwhelming majority of patients with mental illness are not violent, physicians and other health professionals must be trained to respond to those who have a mental illness that might make them more prone to commit violence.

On an average day, more than 100 Americans die from gun violence and firearm-related accidents. In communities like yours – regardless of where you live or how safe it feels – people are losing their lives to this scourge.

For many Americans, gun violence used to be a distant idea relegated mostly to the nightly news, movies and faraway places. But today, in communities such as Parkland, it is horrifyingly real. The victims are our friends, neighbors and, unfathomably, our children.

As physicians, we have dedicated our lives to public health. And at the AMA, our mission is improving the health of the nation. That mission today must include determining the root causes of this epidemic and turning the tide on gun violence.

We must do more than pray for families who lost loved ones. It is time to act to prevent future deaths and injuries.

Dr. Barbe is president of the American Medical Association. His commentary originally was published on AMA Wire.

On Feb. 14 in Parkland, Florida, 17 students and teachers were murdered in yet another school shooting. Yet another mass killing. More than a dozen others were injured and some are fighting for their lives under the care of physicians and nurses.

The pervasiveness of gun violence and the weapons used in these crimes have changed the way we live. In movie theaters, places of worship, offices, restaurants, night clubs and schools, people today make clear note of escape routes. Schools, including the one attacked yesterday, regularly practice for active shooter situations.

And in emergency departments and trauma centers, we struggle with much more complicated, dangerous injuries inflicted by lethal ammunition fired by military-grade weapons.

At the 2016 AMA Annual Meeting, which began the day after the deadly shooting at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, physicians from across the country and at every stage in their career spoke about treating gunshot victims and the scale of violence we are experiencing today. Their stories resonate as much today as they did nearly two years ago.

The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was the 30th mass shooting – a shooting in which four or more people are killed or injured – of 2018. It was also the 17th time a gun has been fired on the grounds of an American school this year. The problem is getting worse – the regularity of, and death from, mass shootings is increasing. With the shooting in Parkland, three of the 10 deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history have come in the past five months.

Time to act

Gun violence in America today is a public health crisis, one that requires a comprehensive and far-reaching solution. And that is not just my own sentiment; that is the determination of the AMA House of Delegates. With more than 30,000 American men, women and children dying from gun violence and firearm-related accidents each year, the time to act is now.

Today, more than ever before, America’s physicians must lend their voice and their considerable political muscle to force lawmakers to examine this urgent health crisis – through federally funded research – and take appropriate steps to address it. Let me be very clear about this. We are not talking about Second Amendment rights or restricting your ability to own a firearm.

We are talking about a public health crisis that our Congress has failed to address. This must end.

In the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012 – a massacre that left 20 first-graders and six adults dead – the AMA wrote to President Obama and to the leaders in the House and Senate. We expressed our sense of grief and sadness and offered our expertise and experience in finding workable, commonsense solutions to reduce the epidemic of gun violence – indeed the overall culture of violence – in America.

We noted that the relatively easy access to the increased firepower of assault weapons, semiautomatic firearms, high-capacity magazines, and high-velocity ammunition heightens the risk of multiple gunshot wounds and severe penetrating trauma, resulting in more critical injuries and deaths. Even for those who manage to survive gun violence involving these weapons, the severity and lasting impact of their wounds, disabilities and treatment leads to devastating consequences for the families affected and for society as a whole, contributing to high medical costs for treatment and recovery.

We called for renewing and strengthening the assault weapons ban, including banning high-capacity magazines, as a step in the right direction. We also called for more resources for safety education programs that promote more responsible use and storage of firearms, and noted that part of ensuring firearms safety means that physicians need to be able to have frank discussions with their patients and parents of patients about firearm safety issues and risks to help them safeguard their families from accidents.

We also urged the nation to strengthen its commitment and resources to comprehensive access to mental health services, including screening, prevention and treatment. While the overwhelming majority of patients with mental illness are not violent, physicians and other health professionals must be trained to respond to those who have a mental illness that might make them more prone to commit violence.

On an average day, more than 100 Americans die from gun violence and firearm-related accidents. In communities like yours – regardless of where you live or how safe it feels – people are losing their lives to this scourge.

For many Americans, gun violence used to be a distant idea relegated mostly to the nightly news, movies and faraway places. But today, in communities such as Parkland, it is horrifyingly real. The victims are our friends, neighbors and, unfathomably, our children.

As physicians, we have dedicated our lives to public health. And at the AMA, our mission is improving the health of the nation. That mission today must include determining the root causes of this epidemic and turning the tide on gun violence.

We must do more than pray for families who lost loved ones. It is time to act to prevent future deaths and injuries.

Dr. Barbe is president of the American Medical Association. His commentary originally was published on AMA Wire.

Allscripts’ charges for sending, refilling prescriptions

How much is $9 worth? Not much. Probably less than most people spend on coffee in a given week.

And yet, that $9 is really irritating to me.

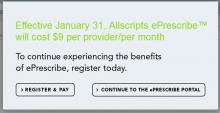

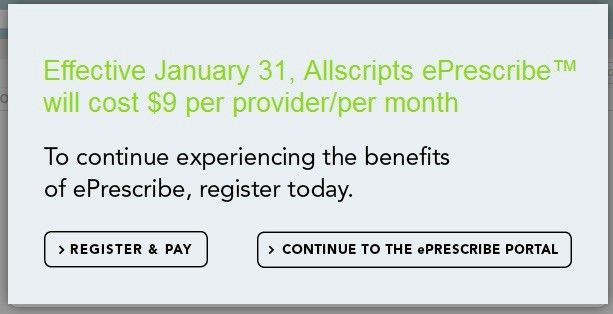

For the last few weeks, when signing into Allscripts to send and refill prescriptions, I’ve encountered this:

I know that $9 a month doesn’t seem like much: It’s $108 a year. But still, it’s irritating.

I understand Allscripts, and every other health care company, is here to make a living. Heck, so am I. Software development isn’t cheap. Neither are the servers hosting it or the security software needed, or the buildings to house them, and a million other things. I get that. None of these things are free.

But, at the same time, it’s part of a general trend of modern health care. Our landlords and vendors can arbitrarily raise prices to keep up with their costs, but we can’t do the same to keep up with ours.

The majority of doctors aren’t in a position to raise our prices to account for these things. We’re stuck with insurance companies and government agencies that tell us to accept a given amount or eat rocks.

There are, of course, concierge practices that can raise their prices, but they’re mostly boutique-level general care with wealthy patients who can afford them. Most small specialists aren’t in that position. We can’t afford to put Keurigs in the lobby.

The few revenue streams most of us have for which we can increase prices, such as legal work and cash patients, are typically not enough of the practice where it would make a difference to overcome it. In fact, the lien company I see patients for recently told me they were lowering their reimbursements to me to compensate for their own higher expenses.

Some people may see the $9 a month as a minor issue and move on. But to a small practice, it’s now another $108 in revenue that I have to bring in each year to cover. And, in a field in which, unlike every other product or service people pay for, I’m not allowed to control my own prices to make up for it.

That doesn’t seem fair, does it?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How much is $9 worth? Not much. Probably less than most people spend on coffee in a given week.

And yet, that $9 is really irritating to me.

For the last few weeks, when signing into Allscripts to send and refill prescriptions, I’ve encountered this:

I know that $9 a month doesn’t seem like much: It’s $108 a year. But still, it’s irritating.

I understand Allscripts, and every other health care company, is here to make a living. Heck, so am I. Software development isn’t cheap. Neither are the servers hosting it or the security software needed, or the buildings to house them, and a million other things. I get that. None of these things are free.

But, at the same time, it’s part of a general trend of modern health care. Our landlords and vendors can arbitrarily raise prices to keep up with their costs, but we can’t do the same to keep up with ours.

The majority of doctors aren’t in a position to raise our prices to account for these things. We’re stuck with insurance companies and government agencies that tell us to accept a given amount or eat rocks.

There are, of course, concierge practices that can raise their prices, but they’re mostly boutique-level general care with wealthy patients who can afford them. Most small specialists aren’t in that position. We can’t afford to put Keurigs in the lobby.

The few revenue streams most of us have for which we can increase prices, such as legal work and cash patients, are typically not enough of the practice where it would make a difference to overcome it. In fact, the lien company I see patients for recently told me they were lowering their reimbursements to me to compensate for their own higher expenses.

Some people may see the $9 a month as a minor issue and move on. But to a small practice, it’s now another $108 in revenue that I have to bring in each year to cover. And, in a field in which, unlike every other product or service people pay for, I’m not allowed to control my own prices to make up for it.

That doesn’t seem fair, does it?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How much is $9 worth? Not much. Probably less than most people spend on coffee in a given week.

And yet, that $9 is really irritating to me.

For the last few weeks, when signing into Allscripts to send and refill prescriptions, I’ve encountered this:

I know that $9 a month doesn’t seem like much: It’s $108 a year. But still, it’s irritating.

I understand Allscripts, and every other health care company, is here to make a living. Heck, so am I. Software development isn’t cheap. Neither are the servers hosting it or the security software needed, or the buildings to house them, and a million other things. I get that. None of these things are free.

But, at the same time, it’s part of a general trend of modern health care. Our landlords and vendors can arbitrarily raise prices to keep up with their costs, but we can’t do the same to keep up with ours.

The majority of doctors aren’t in a position to raise our prices to account for these things. We’re stuck with insurance companies and government agencies that tell us to accept a given amount or eat rocks.

There are, of course, concierge practices that can raise their prices, but they’re mostly boutique-level general care with wealthy patients who can afford them. Most small specialists aren’t in that position. We can’t afford to put Keurigs in the lobby.

The few revenue streams most of us have for which we can increase prices, such as legal work and cash patients, are typically not enough of the practice where it would make a difference to overcome it. In fact, the lien company I see patients for recently told me they were lowering their reimbursements to me to compensate for their own higher expenses.

Some people may see the $9 a month as a minor issue and move on. But to a small practice, it’s now another $108 in revenue that I have to bring in each year to cover. And, in a field in which, unlike every other product or service people pay for, I’m not allowed to control my own prices to make up for it.

That doesn’t seem fair, does it?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

From the ACS President: The joy and privilege of a surgical career

As a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), only you can recall the personal sacrifices you have made to attain the skills and knowledge necessary to enjoy the privilege of being a surgeon – years of missed time with family and friends, sleepless nights, and endless formative hours of deep experiential learning in the hospital. Someone else could have been there instead; you could have made a different career choice. But, no – surgery chose you, and you dove in. Thank you, thank you.

I hope you never lose sight of the lives you touched during those “lost” times – injured people, previously unknown neighbors with deadly diseases, or simply patients needing a little “repair.” People with a surgical disease are experiencing a rare life event: an operation. Never forget that each of those individuals, each patient, came to you – you personally – to help them.

Challenges

Regrettably, however, at times the cherished bond between a surgeon and a patient can get lost in our busy, burdened lives. It can get lost in physical fatigue, regulatory hoops, frustrations of the electronic health record, contract negotiations, challenging reimbursement policies, and on and on.

Add to that list other challenges that will surely arise in the course of your career: You will face various forms of threatened obsolescence in knowledge, skills, and technology. You will age. You will suffer personal tragedy and loss. You will become ill. That you may stumble when facing such challenges is not a sign of weakness. It is life.

I believe there is a bit of light ahead as our health care industry begins to recognize that this thing we call burnout is not a personal failing, but rather a function of our flawed work environments – and a significant threat not only to the surgeon, but also to patient safety, quality of care, and institutional financial stability. An active voice and actions in these essential domains of our work environment are mission critical for our College, as are efforts that are pursued on many fronts by Fellows and professionals in the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in Washington, DC, and the Divisions of Research and Optimal Patient Care, Education, and Member Services in Chicago, IL. Fostering an environment to optimally support the care of the surgical patient – and surgeons – is core business in all we do in the ACS.

Let’s tackle a few other challenges. First, consider your personal and society’s investment in surgical training. Getting you to this skilled and knowledgeable point reflects an investment of more than $1 million dollars in costs of medical school and graduate medical education, and inestimable time and effort.

Second, the dire anticipated shortage of surgeons of many disciplines – general surgeons, orthopedists, urologists – appears to be real. If we are to keep our surgical pipeline full, we need to offer careers that are attractive to men and women equally. The U.S. general surgery pathway has entering classes of 40% women; however, other high-demand disciplines, such as neurosurgery, orthopedics, and cardiothoracic surgery, have not yet attracted women to their ranks in sufficient numbers, despite the fact that 50% of our medical school graduates are women. We need to examine the pathways to those surgical disciplines to ensure that gender- and ethnicity-based barriers are receding. Efforts are underway to address these challenges by the leadership in these disciplines that our College can help with.

Although much has changed for women in surgery in recent years, there are still differences in the lives of many female surgeons compared to their male colleagues. They remain at risk for pay inequity, being in aggregate compensated 10-17% less than their male colleagues for equal work. Despite a mature gender pipeline in some surgical specialties, women are still less likely to rise to leadership roles in their group practices, hospital structures, professional organizations, and academic institutions. The ACS can serve as a professional home to develop strategies to highlight and remedy these imbalances.

Parenting, to engage as fully and successfully as one may wish, is a challenge for many who choose our careers, regardless of gender. However, for most female surgeons beginning a family, the first step often comes with pregnancy and infant care, conditions that we have yet to embrace and support as a societal good rather than an individual’s gauntlet to run. Given our long and arduous educational pathways, these women often find themselves starting a family, be it by pregnancy or adoption, at the same moment they are beginning their busy early years of practice. Policies and practices to support surgeons who choose parenthood in the workforce are sorely needed and will, in fact, benefit all in the long run.

Our College, with guidance from the Women in Surgery Committee and the Association of Women Surgeons, has advanced that goal, issuing a statement that acknowledges the need for appropriate pregnancy and parental leave and that clearly articulates that the choice to become a parent in no way diminishes a surgeon’s commitment to career. The next steps will be building the institutional, financial, and community infrastructure to foster success in both career and parenting for all.

Retooling reimagined

Let’s ponder another challenge: the need to add to your repertoire a new, potentially transformative skill. How do we safely retool?

Twenty years ago, in the flawed early adoption of laparoscopic surgery, the ACS Committee on Emerging Surgical Technology Education articulated the principles of new skill acquisition: didactic learning, coupled with simulation-based training, and then proctored early experience, leading to independent practice and assessment of outcomes.

Subsequently, the College took the visionary step of establishing the ACS Accredited Education Institutes (AEI) program to develop a network of centers that would leverage emerging simulation technologies to enhance surgical training. The 96 national and international AEIs now serve as both educational and research centers to teach technical and nontechnical skills to surgeons and other health care professionals. At Houston Methodist Hospital, for example, we have built MITIE (Methodist Institute for Technology Innovation and Education), a comprehensive center with a focus on retooling surgeons in practice. We have hosted more than 13,000 surgeons in practice for retooling hands-on courses, along with more than 30,000 other health care professionals.

To ensure our surgical workforce stays at the top of their performance over a 40-year career, our College has convened a group of stakeholders, including payers, consumers, liability carriers, surgical technology industries, hospital executives, and, of course, surgeons, to define the infrastructure – facilities, faculty, curricula, assessment tools, and finances – needed to incorporate retooling and retraining into our health care system. Work to do.

Shape your future

The retooling reimagined initiative is but one example of how we can shape our professional futures. Remember, the ACS was founded nearly 105 years ago by surgeons who sought to improve the care of the surgical patient. Since then, individual surgeons, banding together within our College, have created some of the most effective systems in the world to improve surgical care – including the formation of the Committee on Trauma and the Commission on Cancer, which have led initiatives that have vastly improved care for their respective patient populations.

The ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, born of the vision of Shukri Khuri, MD, FACS, who, when tasked with resolving a perceived problem in surgical care in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System, launched a research study to measure quality. Soon thereafter, he led an army of surgeons to improve surgical care in their own hospitals, founding a nationwide movement that now flourishes in thousands of hospitals as the world’s most effective surgical quality measurement and improvement system.

We can go on and on. A surgeon identifies a gap and with a good idea, and coupled to abundant College focus and the engagement of our Fellows, a valuable new program is launched. These initiatives were not delivered from on high. They were created by regular surgeons, like you and me, who saw gaps in their professional worlds and took steps to effect meaningful change.

Caring for each other

I have one more request: I want you to be aware of your colleagues. I want you to watch them for signs of stress and disturbances in their forces. And if you see something, ask a supportive question or offer needed assistance. Be aware of help that is available in your institution; know how to move a concern up the chain with sensitivity, but also with efficacy, coupled with compassionate concern for your colleague.

These are not easy discussions and may prove fruitless, but they are worth the effort to try, for we surgeons are a high-risk group for depression, substance abuse, and suicide – and for failing to seek assistance. This situation must change, but doing so will require that we destigmatize these conditions in ourselves and our colleagues, and destigmatize seeking assistance.

But, for now, on a joyful or a challenging day in your surgical life, I hope you are proud of your Fellowship in the ACS and your FACS initials that signify your commitment to the values of our profession. I hope you will draw endless support and friendship from those around you and that you will contribute more than you receive. And I hope that you will forever treasure your opportunity to practice as a surgeon, an exceptional joy and privilege.

Dr. Bass is the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Presidential Endowed Chair, professor of surgery and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, and the President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

As a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), only you can recall the personal sacrifices you have made to attain the skills and knowledge necessary to enjoy the privilege of being a surgeon – years of missed time with family and friends, sleepless nights, and endless formative hours of deep experiential learning in the hospital. Someone else could have been there instead; you could have made a different career choice. But, no – surgery chose you, and you dove in. Thank you, thank you.

I hope you never lose sight of the lives you touched during those “lost” times – injured people, previously unknown neighbors with deadly diseases, or simply patients needing a little “repair.” People with a surgical disease are experiencing a rare life event: an operation. Never forget that each of those individuals, each patient, came to you – you personally – to help them.

Challenges

Regrettably, however, at times the cherished bond between a surgeon and a patient can get lost in our busy, burdened lives. It can get lost in physical fatigue, regulatory hoops, frustrations of the electronic health record, contract negotiations, challenging reimbursement policies, and on and on.

Add to that list other challenges that will surely arise in the course of your career: You will face various forms of threatened obsolescence in knowledge, skills, and technology. You will age. You will suffer personal tragedy and loss. You will become ill. That you may stumble when facing such challenges is not a sign of weakness. It is life.

I believe there is a bit of light ahead as our health care industry begins to recognize that this thing we call burnout is not a personal failing, but rather a function of our flawed work environments – and a significant threat not only to the surgeon, but also to patient safety, quality of care, and institutional financial stability. An active voice and actions in these essential domains of our work environment are mission critical for our College, as are efforts that are pursued on many fronts by Fellows and professionals in the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in Washington, DC, and the Divisions of Research and Optimal Patient Care, Education, and Member Services in Chicago, IL. Fostering an environment to optimally support the care of the surgical patient – and surgeons – is core business in all we do in the ACS.

Let’s tackle a few other challenges. First, consider your personal and society’s investment in surgical training. Getting you to this skilled and knowledgeable point reflects an investment of more than $1 million dollars in costs of medical school and graduate medical education, and inestimable time and effort.

Second, the dire anticipated shortage of surgeons of many disciplines – general surgeons, orthopedists, urologists – appears to be real. If we are to keep our surgical pipeline full, we need to offer careers that are attractive to men and women equally. The U.S. general surgery pathway has entering classes of 40% women; however, other high-demand disciplines, such as neurosurgery, orthopedics, and cardiothoracic surgery, have not yet attracted women to their ranks in sufficient numbers, despite the fact that 50% of our medical school graduates are women. We need to examine the pathways to those surgical disciplines to ensure that gender- and ethnicity-based barriers are receding. Efforts are underway to address these challenges by the leadership in these disciplines that our College can help with.

Although much has changed for women in surgery in recent years, there are still differences in the lives of many female surgeons compared to their male colleagues. They remain at risk for pay inequity, being in aggregate compensated 10-17% less than their male colleagues for equal work. Despite a mature gender pipeline in some surgical specialties, women are still less likely to rise to leadership roles in their group practices, hospital structures, professional organizations, and academic institutions. The ACS can serve as a professional home to develop strategies to highlight and remedy these imbalances.

Parenting, to engage as fully and successfully as one may wish, is a challenge for many who choose our careers, regardless of gender. However, for most female surgeons beginning a family, the first step often comes with pregnancy and infant care, conditions that we have yet to embrace and support as a societal good rather than an individual’s gauntlet to run. Given our long and arduous educational pathways, these women often find themselves starting a family, be it by pregnancy or adoption, at the same moment they are beginning their busy early years of practice. Policies and practices to support surgeons who choose parenthood in the workforce are sorely needed and will, in fact, benefit all in the long run.

Our College, with guidance from the Women in Surgery Committee and the Association of Women Surgeons, has advanced that goal, issuing a statement that acknowledges the need for appropriate pregnancy and parental leave and that clearly articulates that the choice to become a parent in no way diminishes a surgeon’s commitment to career. The next steps will be building the institutional, financial, and community infrastructure to foster success in both career and parenting for all.

Retooling reimagined

Let’s ponder another challenge: the need to add to your repertoire a new, potentially transformative skill. How do we safely retool?

Twenty years ago, in the flawed early adoption of laparoscopic surgery, the ACS Committee on Emerging Surgical Technology Education articulated the principles of new skill acquisition: didactic learning, coupled with simulation-based training, and then proctored early experience, leading to independent practice and assessment of outcomes.

Subsequently, the College took the visionary step of establishing the ACS Accredited Education Institutes (AEI) program to develop a network of centers that would leverage emerging simulation technologies to enhance surgical training. The 96 national and international AEIs now serve as both educational and research centers to teach technical and nontechnical skills to surgeons and other health care professionals. At Houston Methodist Hospital, for example, we have built MITIE (Methodist Institute for Technology Innovation and Education), a comprehensive center with a focus on retooling surgeons in practice. We have hosted more than 13,000 surgeons in practice for retooling hands-on courses, along with more than 30,000 other health care professionals.

To ensure our surgical workforce stays at the top of their performance over a 40-year career, our College has convened a group of stakeholders, including payers, consumers, liability carriers, surgical technology industries, hospital executives, and, of course, surgeons, to define the infrastructure – facilities, faculty, curricula, assessment tools, and finances – needed to incorporate retooling and retraining into our health care system. Work to do.

Shape your future

The retooling reimagined initiative is but one example of how we can shape our professional futures. Remember, the ACS was founded nearly 105 years ago by surgeons who sought to improve the care of the surgical patient. Since then, individual surgeons, banding together within our College, have created some of the most effective systems in the world to improve surgical care – including the formation of the Committee on Trauma and the Commission on Cancer, which have led initiatives that have vastly improved care for their respective patient populations.

The ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, born of the vision of Shukri Khuri, MD, FACS, who, when tasked with resolving a perceived problem in surgical care in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System, launched a research study to measure quality. Soon thereafter, he led an army of surgeons to improve surgical care in their own hospitals, founding a nationwide movement that now flourishes in thousands of hospitals as the world’s most effective surgical quality measurement and improvement system.

We can go on and on. A surgeon identifies a gap and with a good idea, and coupled to abundant College focus and the engagement of our Fellows, a valuable new program is launched. These initiatives were not delivered from on high. They were created by regular surgeons, like you and me, who saw gaps in their professional worlds and took steps to effect meaningful change.

Caring for each other

I have one more request: I want you to be aware of your colleagues. I want you to watch them for signs of stress and disturbances in their forces. And if you see something, ask a supportive question or offer needed assistance. Be aware of help that is available in your institution; know how to move a concern up the chain with sensitivity, but also with efficacy, coupled with compassionate concern for your colleague.

These are not easy discussions and may prove fruitless, but they are worth the effort to try, for we surgeons are a high-risk group for depression, substance abuse, and suicide – and for failing to seek assistance. This situation must change, but doing so will require that we destigmatize these conditions in ourselves and our colleagues, and destigmatize seeking assistance.

But, for now, on a joyful or a challenging day in your surgical life, I hope you are proud of your Fellowship in the ACS and your FACS initials that signify your commitment to the values of our profession. I hope you will draw endless support and friendship from those around you and that you will contribute more than you receive. And I hope that you will forever treasure your opportunity to practice as a surgeon, an exceptional joy and privilege.

Dr. Bass is the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Presidential Endowed Chair, professor of surgery and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, and the President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

As a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), only you can recall the personal sacrifices you have made to attain the skills and knowledge necessary to enjoy the privilege of being a surgeon – years of missed time with family and friends, sleepless nights, and endless formative hours of deep experiential learning in the hospital. Someone else could have been there instead; you could have made a different career choice. But, no – surgery chose you, and you dove in. Thank you, thank you.

I hope you never lose sight of the lives you touched during those “lost” times – injured people, previously unknown neighbors with deadly diseases, or simply patients needing a little “repair.” People with a surgical disease are experiencing a rare life event: an operation. Never forget that each of those individuals, each patient, came to you – you personally – to help them.

Challenges

Regrettably, however, at times the cherished bond between a surgeon and a patient can get lost in our busy, burdened lives. It can get lost in physical fatigue, regulatory hoops, frustrations of the electronic health record, contract negotiations, challenging reimbursement policies, and on and on.

Add to that list other challenges that will surely arise in the course of your career: You will face various forms of threatened obsolescence in knowledge, skills, and technology. You will age. You will suffer personal tragedy and loss. You will become ill. That you may stumble when facing such challenges is not a sign of weakness. It is life.

I believe there is a bit of light ahead as our health care industry begins to recognize that this thing we call burnout is not a personal failing, but rather a function of our flawed work environments – and a significant threat not only to the surgeon, but also to patient safety, quality of care, and institutional financial stability. An active voice and actions in these essential domains of our work environment are mission critical for our College, as are efforts that are pursued on many fronts by Fellows and professionals in the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in Washington, DC, and the Divisions of Research and Optimal Patient Care, Education, and Member Services in Chicago, IL. Fostering an environment to optimally support the care of the surgical patient – and surgeons – is core business in all we do in the ACS.

Let’s tackle a few other challenges. First, consider your personal and society’s investment in surgical training. Getting you to this skilled and knowledgeable point reflects an investment of more than $1 million dollars in costs of medical school and graduate medical education, and inestimable time and effort.

Second, the dire anticipated shortage of surgeons of many disciplines – general surgeons, orthopedists, urologists – appears to be real. If we are to keep our surgical pipeline full, we need to offer careers that are attractive to men and women equally. The U.S. general surgery pathway has entering classes of 40% women; however, other high-demand disciplines, such as neurosurgery, orthopedics, and cardiothoracic surgery, have not yet attracted women to their ranks in sufficient numbers, despite the fact that 50% of our medical school graduates are women. We need to examine the pathways to those surgical disciplines to ensure that gender- and ethnicity-based barriers are receding. Efforts are underway to address these challenges by the leadership in these disciplines that our College can help with.

Although much has changed for women in surgery in recent years, there are still differences in the lives of many female surgeons compared to their male colleagues. They remain at risk for pay inequity, being in aggregate compensated 10-17% less than their male colleagues for equal work. Despite a mature gender pipeline in some surgical specialties, women are still less likely to rise to leadership roles in their group practices, hospital structures, professional organizations, and academic institutions. The ACS can serve as a professional home to develop strategies to highlight and remedy these imbalances.

Parenting, to engage as fully and successfully as one may wish, is a challenge for many who choose our careers, regardless of gender. However, for most female surgeons beginning a family, the first step often comes with pregnancy and infant care, conditions that we have yet to embrace and support as a societal good rather than an individual’s gauntlet to run. Given our long and arduous educational pathways, these women often find themselves starting a family, be it by pregnancy or adoption, at the same moment they are beginning their busy early years of practice. Policies and practices to support surgeons who choose parenthood in the workforce are sorely needed and will, in fact, benefit all in the long run.

Our College, with guidance from the Women in Surgery Committee and the Association of Women Surgeons, has advanced that goal, issuing a statement that acknowledges the need for appropriate pregnancy and parental leave and that clearly articulates that the choice to become a parent in no way diminishes a surgeon’s commitment to career. The next steps will be building the institutional, financial, and community infrastructure to foster success in both career and parenting for all.

Retooling reimagined

Let’s ponder another challenge: the need to add to your repertoire a new, potentially transformative skill. How do we safely retool?

Twenty years ago, in the flawed early adoption of laparoscopic surgery, the ACS Committee on Emerging Surgical Technology Education articulated the principles of new skill acquisition: didactic learning, coupled with simulation-based training, and then proctored early experience, leading to independent practice and assessment of outcomes.

Subsequently, the College took the visionary step of establishing the ACS Accredited Education Institutes (AEI) program to develop a network of centers that would leverage emerging simulation technologies to enhance surgical training. The 96 national and international AEIs now serve as both educational and research centers to teach technical and nontechnical skills to surgeons and other health care professionals. At Houston Methodist Hospital, for example, we have built MITIE (Methodist Institute for Technology Innovation and Education), a comprehensive center with a focus on retooling surgeons in practice. We have hosted more than 13,000 surgeons in practice for retooling hands-on courses, along with more than 30,000 other health care professionals.

To ensure our surgical workforce stays at the top of their performance over a 40-year career, our College has convened a group of stakeholders, including payers, consumers, liability carriers, surgical technology industries, hospital executives, and, of course, surgeons, to define the infrastructure – facilities, faculty, curricula, assessment tools, and finances – needed to incorporate retooling and retraining into our health care system. Work to do.

Shape your future

The retooling reimagined initiative is but one example of how we can shape our professional futures. Remember, the ACS was founded nearly 105 years ago by surgeons who sought to improve the care of the surgical patient. Since then, individual surgeons, banding together within our College, have created some of the most effective systems in the world to improve surgical care – including the formation of the Committee on Trauma and the Commission on Cancer, which have led initiatives that have vastly improved care for their respective patient populations.

The ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, born of the vision of Shukri Khuri, MD, FACS, who, when tasked with resolving a perceived problem in surgical care in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System, launched a research study to measure quality. Soon thereafter, he led an army of surgeons to improve surgical care in their own hospitals, founding a nationwide movement that now flourishes in thousands of hospitals as the world’s most effective surgical quality measurement and improvement system.

We can go on and on. A surgeon identifies a gap and with a good idea, and coupled to abundant College focus and the engagement of our Fellows, a valuable new program is launched. These initiatives were not delivered from on high. They were created by regular surgeons, like you and me, who saw gaps in their professional worlds and took steps to effect meaningful change.

Caring for each other

I have one more request: I want you to be aware of your colleagues. I want you to watch them for signs of stress and disturbances in their forces. And if you see something, ask a supportive question or offer needed assistance. Be aware of help that is available in your institution; know how to move a concern up the chain with sensitivity, but also with efficacy, coupled with compassionate concern for your colleague.

These are not easy discussions and may prove fruitless, but they are worth the effort to try, for we surgeons are a high-risk group for depression, substance abuse, and suicide – and for failing to seek assistance. This situation must change, but doing so will require that we destigmatize these conditions in ourselves and our colleagues, and destigmatize seeking assistance.

But, for now, on a joyful or a challenging day in your surgical life, I hope you are proud of your Fellowship in the ACS and your FACS initials that signify your commitment to the values of our profession. I hope you will draw endless support and friendship from those around you and that you will contribute more than you receive. And I hope that you will forever treasure your opportunity to practice as a surgeon, an exceptional joy and privilege.

Dr. Bass is the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Presidential Endowed Chair, professor of surgery and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, and the President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

Consent and DNR orders

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?