User login

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - January 2018

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare fibrosing disorder of the skin and the underlying tissue that encompasses a variety of distinct subtypes classified by pattern and depth of lesion involvement. It may involve fat, fascia, muscle, and bone, and rarely, the central nervous system. Morphea is easily differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its primarily cutaneous involvement, although a minority of patients may have associated extracutaneous findings. Systemic sclerosis describes a well-defined disorder of skin sclerosis with a specific pattern of internal organ involvement.

Classification of the different subtypes of morphea are based on clinical presentation of the lesions. The most widely used system characterizes morphea into linear, circumscribed, generalized, pansclerotic, and mixed morphea subtypes.1 Mixed morphea describes the presence of two or more patterns of disease and affects 15% of patients. Morphea lesions initially present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques that eventually become white and sclerotic, with resulting destruction of the surrounding structures.

Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of morphea in children and adolescents, affecting 42%-67% of children with morphea.1 It is characterized by linear plaques, often on the extremities, face, or scalp, that tend to follow Blaschko lines.4 These lesions may extend past the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone, resulting in significant deformities. When on the scalp or face, particularly the forehead, the linear lesion may be referred to as the en coup de sabre variant. Ocular and CNS involvement should be of concern in these patients. When subcutaneous atrophy on the unilateral face is present with unaffected overlaying skin, this is known as the Parry-Romberg syndrome or progressive hemifacial atrophy. Involvement of the extremities is common, and unfortunately, may lead to muscle atrophy of the affected limb, contractures in areas overlying joint spaces, and occasionally limb length discrepancies.

Circumscribed morphea describes three or fewer discrete, oval, or round indurated plaques, with central whitening and a violaceous periphery. They generally are found on the trunk. When lesions have deeper involvement, delving past the dermis to involve the underlying fascia and muscle, the patient may experience a “bound down” sensation. Most lesions soften over 3-5 years.

Generalized morphea is used to describe the presence of at least four plaques, larger than 3 cm, that become confluent in at least two different locations on the body. Patients with generalized morphea have higher rates of systemic symptoms such as arthritis and fatigue.

Pansclerotic morphea, the most severe subtype, is characterized by significant body surface area involvement coupled with deep depth of involvement, often to the bone. The widespread blistering associated with pansclerotic morphea may lead to chronic ulceration and, later on, a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma development. Despite its extensive distribution, pansclerotic morphea does not cause the severe organ and vascular fibrosis that is characteristically seen in systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal nailfold capillaries, and sclerodactyly also will be absent in pansclerotic morphea.

Extracutaneous findings are present in up to 22% of patients with morphea.5 Arthritis is the most common associated finding, and often is correlated with a positive rheumatoid factor. Neurologic involvement most frequently is seen in patients with facial morphea and may present as seizures, as in this patient. MRI abnormalities such as calcifications and white matter changes may be seen. Other common extracutaneous features include fatigue, vascular abnormalities, and ocular findings, such as uveitis.

Morphea and systemic sclerosis appear similar on histology. In early morphea, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates may be seen in the reticular dermis. In late morphea, the inflammatory cells are replaced by an abundance of collagen bundles infiltrating the dermis.

although the instigating factor activating this pathway is unknown. Multiple factors have been associated with the development of morphea, including autoimmunity, trauma, Borrelia and cytomegalovirus infections, radiation, and certain medications in case reports. Patients with morphea have higher rates of concomitant autoimmune diseases than that found in the general population6 and also have higher rates of autoantibody positivity. In a 750-patient, multicenter study of children with morphea, 42% of patients had positive antinuclear antibodies.7

Diagnosis

Morphea is diagnosed clinically, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. A biopsy may be helpful if the presentation is atypical. Although patients with morphea have higher rates of autoantibody positivity, there are no specific laboratory tests that consistently or reliably offer diagnostic value.8 Imaging modalities such as MRI may be utilized to view depth of involvement. Other noninvasive measures, such as thermography and ultrasonography, may be used to determine disease activity.9

Treatment

Treatment for morphea often is multidisciplinary and depends on the severity of involvement and extent to which it impedes functionality and quality of life. Localized plaques that do not restrict movement may be treated with topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus. However, topical corticosteroids should be discontinued if there are no signs of improvement in 2-3 months.

For patients with deforming or functionally significant disease, systemic treatment is advised. Methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids has been frequently studied, and is the most commonly recommended systemic therapy.11 Some experts have recommended treatment for at least 2-3 years, with at least 1 year of disease inactivity, before discontinuing treatment. Despite this duration of treatment, up to one-quarter of patients, especially those with linear morphea, will still experience recurrence of disease. Management of morphea may be aided by rheumatology and/or dermatology consultation.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Han and Dr. Eichenfield had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

1. Fett N et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Feb;64(2):217-28.

2. Condie D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504.

3. Zulian F et al. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):248-51.

4. Weibel L et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jul;159(1):175-81.

5. Zulian F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81.

6. Leitenberger JJ et al. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50.

7. Zulian F et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):614-20.

8. Dharamsi JW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Oct;149(10):1159-65.

9. Zulian F et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;25(5):643-50.

10. Pope E et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):309-19.

11. Strickland N et al. Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr; 72(4): 727-8.

12. Schoch JJ et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. 35(1): 43-6.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare fibrosing disorder of the skin and the underlying tissue that encompasses a variety of distinct subtypes classified by pattern and depth of lesion involvement. It may involve fat, fascia, muscle, and bone, and rarely, the central nervous system. Morphea is easily differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its primarily cutaneous involvement, although a minority of patients may have associated extracutaneous findings. Systemic sclerosis describes a well-defined disorder of skin sclerosis with a specific pattern of internal organ involvement.

Classification of the different subtypes of morphea are based on clinical presentation of the lesions. The most widely used system characterizes morphea into linear, circumscribed, generalized, pansclerotic, and mixed morphea subtypes.1 Mixed morphea describes the presence of two or more patterns of disease and affects 15% of patients. Morphea lesions initially present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques that eventually become white and sclerotic, with resulting destruction of the surrounding structures.

Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of morphea in children and adolescents, affecting 42%-67% of children with morphea.1 It is characterized by linear plaques, often on the extremities, face, or scalp, that tend to follow Blaschko lines.4 These lesions may extend past the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone, resulting in significant deformities. When on the scalp or face, particularly the forehead, the linear lesion may be referred to as the en coup de sabre variant. Ocular and CNS involvement should be of concern in these patients. When subcutaneous atrophy on the unilateral face is present with unaffected overlaying skin, this is known as the Parry-Romberg syndrome or progressive hemifacial atrophy. Involvement of the extremities is common, and unfortunately, may lead to muscle atrophy of the affected limb, contractures in areas overlying joint spaces, and occasionally limb length discrepancies.

Circumscribed morphea describes three or fewer discrete, oval, or round indurated plaques, with central whitening and a violaceous periphery. They generally are found on the trunk. When lesions have deeper involvement, delving past the dermis to involve the underlying fascia and muscle, the patient may experience a “bound down” sensation. Most lesions soften over 3-5 years.

Generalized morphea is used to describe the presence of at least four plaques, larger than 3 cm, that become confluent in at least two different locations on the body. Patients with generalized morphea have higher rates of systemic symptoms such as arthritis and fatigue.

Pansclerotic morphea, the most severe subtype, is characterized by significant body surface area involvement coupled with deep depth of involvement, often to the bone. The widespread blistering associated with pansclerotic morphea may lead to chronic ulceration and, later on, a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma development. Despite its extensive distribution, pansclerotic morphea does not cause the severe organ and vascular fibrosis that is characteristically seen in systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal nailfold capillaries, and sclerodactyly also will be absent in pansclerotic morphea.

Extracutaneous findings are present in up to 22% of patients with morphea.5 Arthritis is the most common associated finding, and often is correlated with a positive rheumatoid factor. Neurologic involvement most frequently is seen in patients with facial morphea and may present as seizures, as in this patient. MRI abnormalities such as calcifications and white matter changes may be seen. Other common extracutaneous features include fatigue, vascular abnormalities, and ocular findings, such as uveitis.

Morphea and systemic sclerosis appear similar on histology. In early morphea, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates may be seen in the reticular dermis. In late morphea, the inflammatory cells are replaced by an abundance of collagen bundles infiltrating the dermis.

although the instigating factor activating this pathway is unknown. Multiple factors have been associated with the development of morphea, including autoimmunity, trauma, Borrelia and cytomegalovirus infections, radiation, and certain medications in case reports. Patients with morphea have higher rates of concomitant autoimmune diseases than that found in the general population6 and also have higher rates of autoantibody positivity. In a 750-patient, multicenter study of children with morphea, 42% of patients had positive antinuclear antibodies.7

Diagnosis

Morphea is diagnosed clinically, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. A biopsy may be helpful if the presentation is atypical. Although patients with morphea have higher rates of autoantibody positivity, there are no specific laboratory tests that consistently or reliably offer diagnostic value.8 Imaging modalities such as MRI may be utilized to view depth of involvement. Other noninvasive measures, such as thermography and ultrasonography, may be used to determine disease activity.9

Treatment

Treatment for morphea often is multidisciplinary and depends on the severity of involvement and extent to which it impedes functionality and quality of life. Localized plaques that do not restrict movement may be treated with topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus. However, topical corticosteroids should be discontinued if there are no signs of improvement in 2-3 months.

For patients with deforming or functionally significant disease, systemic treatment is advised. Methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids has been frequently studied, and is the most commonly recommended systemic therapy.11 Some experts have recommended treatment for at least 2-3 years, with at least 1 year of disease inactivity, before discontinuing treatment. Despite this duration of treatment, up to one-quarter of patients, especially those with linear morphea, will still experience recurrence of disease. Management of morphea may be aided by rheumatology and/or dermatology consultation.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Han and Dr. Eichenfield had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

1. Fett N et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Feb;64(2):217-28.

2. Condie D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504.

3. Zulian F et al. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):248-51.

4. Weibel L et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jul;159(1):175-81.

5. Zulian F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81.

6. Leitenberger JJ et al. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50.

7. Zulian F et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):614-20.

8. Dharamsi JW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Oct;149(10):1159-65.

9. Zulian F et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;25(5):643-50.

10. Pope E et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):309-19.

11. Strickland N et al. Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr; 72(4): 727-8.

12. Schoch JJ et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. 35(1): 43-6.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare fibrosing disorder of the skin and the underlying tissue that encompasses a variety of distinct subtypes classified by pattern and depth of lesion involvement. It may involve fat, fascia, muscle, and bone, and rarely, the central nervous system. Morphea is easily differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its primarily cutaneous involvement, although a minority of patients may have associated extracutaneous findings. Systemic sclerosis describes a well-defined disorder of skin sclerosis with a specific pattern of internal organ involvement.

Classification of the different subtypes of morphea are based on clinical presentation of the lesions. The most widely used system characterizes morphea into linear, circumscribed, generalized, pansclerotic, and mixed morphea subtypes.1 Mixed morphea describes the presence of two or more patterns of disease and affects 15% of patients. Morphea lesions initially present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques that eventually become white and sclerotic, with resulting destruction of the surrounding structures.

Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of morphea in children and adolescents, affecting 42%-67% of children with morphea.1 It is characterized by linear plaques, often on the extremities, face, or scalp, that tend to follow Blaschko lines.4 These lesions may extend past the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone, resulting in significant deformities. When on the scalp or face, particularly the forehead, the linear lesion may be referred to as the en coup de sabre variant. Ocular and CNS involvement should be of concern in these patients. When subcutaneous atrophy on the unilateral face is present with unaffected overlaying skin, this is known as the Parry-Romberg syndrome or progressive hemifacial atrophy. Involvement of the extremities is common, and unfortunately, may lead to muscle atrophy of the affected limb, contractures in areas overlying joint spaces, and occasionally limb length discrepancies.

Circumscribed morphea describes three or fewer discrete, oval, or round indurated plaques, with central whitening and a violaceous periphery. They generally are found on the trunk. When lesions have deeper involvement, delving past the dermis to involve the underlying fascia and muscle, the patient may experience a “bound down” sensation. Most lesions soften over 3-5 years.

Generalized morphea is used to describe the presence of at least four plaques, larger than 3 cm, that become confluent in at least two different locations on the body. Patients with generalized morphea have higher rates of systemic symptoms such as arthritis and fatigue.

Pansclerotic morphea, the most severe subtype, is characterized by significant body surface area involvement coupled with deep depth of involvement, often to the bone. The widespread blistering associated with pansclerotic morphea may lead to chronic ulceration and, later on, a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma development. Despite its extensive distribution, pansclerotic morphea does not cause the severe organ and vascular fibrosis that is characteristically seen in systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal nailfold capillaries, and sclerodactyly also will be absent in pansclerotic morphea.

Extracutaneous findings are present in up to 22% of patients with morphea.5 Arthritis is the most common associated finding, and often is correlated with a positive rheumatoid factor. Neurologic involvement most frequently is seen in patients with facial morphea and may present as seizures, as in this patient. MRI abnormalities such as calcifications and white matter changes may be seen. Other common extracutaneous features include fatigue, vascular abnormalities, and ocular findings, such as uveitis.

Morphea and systemic sclerosis appear similar on histology. In early morphea, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates may be seen in the reticular dermis. In late morphea, the inflammatory cells are replaced by an abundance of collagen bundles infiltrating the dermis.

although the instigating factor activating this pathway is unknown. Multiple factors have been associated with the development of morphea, including autoimmunity, trauma, Borrelia and cytomegalovirus infections, radiation, and certain medications in case reports. Patients with morphea have higher rates of concomitant autoimmune diseases than that found in the general population6 and also have higher rates of autoantibody positivity. In a 750-patient, multicenter study of children with morphea, 42% of patients had positive antinuclear antibodies.7

Diagnosis

Morphea is diagnosed clinically, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. A biopsy may be helpful if the presentation is atypical. Although patients with morphea have higher rates of autoantibody positivity, there are no specific laboratory tests that consistently or reliably offer diagnostic value.8 Imaging modalities such as MRI may be utilized to view depth of involvement. Other noninvasive measures, such as thermography and ultrasonography, may be used to determine disease activity.9

Treatment

Treatment for morphea often is multidisciplinary and depends on the severity of involvement and extent to which it impedes functionality and quality of life. Localized plaques that do not restrict movement may be treated with topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus. However, topical corticosteroids should be discontinued if there are no signs of improvement in 2-3 months.

For patients with deforming or functionally significant disease, systemic treatment is advised. Methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids has been frequently studied, and is the most commonly recommended systemic therapy.11 Some experts have recommended treatment for at least 2-3 years, with at least 1 year of disease inactivity, before discontinuing treatment. Despite this duration of treatment, up to one-quarter of patients, especially those with linear morphea, will still experience recurrence of disease. Management of morphea may be aided by rheumatology and/or dermatology consultation.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Han and Dr. Eichenfield had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

1. Fett N et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Feb;64(2):217-28.

2. Condie D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504.

3. Zulian F et al. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):248-51.

4. Weibel L et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jul;159(1):175-81.

5. Zulian F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81.

6. Leitenberger JJ et al. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50.

7. Zulian F et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):614-20.

8. Dharamsi JW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Oct;149(10):1159-65.

9. Zulian F et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;25(5):643-50.

10. Pope E et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):309-19.

11. Strickland N et al. Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr; 72(4): 727-8.

12. Schoch JJ et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. 35(1): 43-6.

A 14-year-old patient presents to a dermatology clinic for a depression on his forehead, which has been there for about 2 years. A few years ago, he used to have a pruritic pink lesion on the forehead where the depression is now. He denies any symptoms.

Anxiety in teens

It seems that every week there is a new headline about the rising rates of anxiety in today’s adolescents. Schools often are asked to address high levels of stress and anxiety in their students, and the pediatrician’s office is often the first place worried parents will call. We will try to help you differentiate between what is normal – even healthy – adolescent stress, and what might represent treatable psychiatric problems. And we will review how to approach stress management with your patients and their parents. For all adolescents, even those with psychiatric diagnoses, learning to manage stress and anxiety is critical to their healthiest development into capable, confident, resilient adults.

Stress is the mental or emotional strain resulting from demanding or adverse circumstances. Anxiety is a feeling of unease about an imminent event with an uncertain outcome. An anxiety disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by a state of excessive unease leading to functional impairment. These distinctions are critical, as both stress and anxiety are normal-but-uncomfortable parts of the adolescent experience. When all of a teenager’s stress and anxiety is medicalized, it promotes avoidance, which in turn may worsen your patient’s functional impairment rather than improving it.

This is not to suggest that there are not real (and common) psychiatric illnesses that can affect the levels of anxiety in your patients. Anxiety disorders start the earliest, with separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia all having a mean onset before puberty. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in youth (30% of youth psychiatric illness), and anxiety also may be related to substance use disorders (25%), disruptive behavior disorders (20%), and mood disorders (17%). Despite the excited news coverage, there is no evidence of a statistically significant increase in the incidence of anxiety or mood disorders in young people over the past decade.

It is not difficult to imagine that the challenges facing adolescents are considerable. Of course, adolescence is a time of major change starting with puberty, in which young people actively develop independence, identity, and a rich array of deep relationships beyond their families. Typically, this is a 5- to 10-year process of risk-taking, new experiences, setbacks, delight, heartbreak, and triumphs all alongside growing autonomy.

These forces may make their parents even more stressed than the adolescents themselves, but there is one dramatically different feature of adolescent life today: the constant presence of smartphones. While these devices can improve connectedness to school, family, and friends, use of smartphones also means that today’s teenagers often have little downtime cognitively or socially. Use of smartphones can facilitate both supportive affirmation from friends and relentless social pressures, and the feeling of being excluded or bullied. Smartphone use can interfere with restful sleep, and some virtual activities may compete with the genuine experimentation and exploration where teenagers discover their interests and abilities and develop meaningful confidence and independence.

Several factors might impair an adolescent’s ability to cope with challenge and stress. Those teenagers who have not had the opportunity to face and manage modest setbacks, difficulties, and discomforts during their elementary and middle school years may be overwhelmed by starting with the higher-stakes strains of adolescence. This can happen when young children have not explored many new activities, have been shielded from the consequences of failures, or have tried only activities that came easily to them. Certainly, teenagers who are managing a depressive or anxiety disorder as well as those with learning disabilities may have limited ability to cope with routine stress, although those who have a well-treated disorder often have robust coping skills.

Perhaps obvious, but still very important, chronic sleep deprivation can leave adolescents irritable, impatient, and distractible, all of which make coping with a challenge very difficult. Likewise, substance use can directly impair coping skills, and can create the habit of trying to escape stress rather than manage it.

So what does this mean for you? If your patient has an anxiety, depressive, or substance use disorder, refer for appropriate therapy. For both those who screen in and those who do not, your next task is to help them improve their coping skills. What specifically has them so stressed?

Are there family stressors or unrealistic expectations that can be addressed? Can they see their situation as a challenge and focus on what is within their control to do in response? Remind your patients that challenges are uncomfortable. Mastery comes with practice and, inevitably, some setbacks and failures. Have they identified personal goals or a transcendent purpose? This can improve motivation and keep a challenge in perspective. They might focus on learning about their coping style: Do they do better with a slow, steady, methodical approach or intense bursts of effort? Talk with them about self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, putting effort into relaxation as well as work, and spending time with their actual (not just virtual) friends all are essential to keeping their batteries charged while doing the intense work of normal adolescence.

For those patients who do not meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders, there are circumstances in which a referral for therapy can be helpful. If they are noticeably disconnected from their parents or their parents seem to be more reactive to the stress and pressures than they are, an outside therapist can be a meaningful support as they build skills. Those patients who are socially isolated and stressed, are using substances regularly, are withdrawing from other interests to manage their source of stress, or are having difficulty telling facts from feelings are at risk for failing to adequately manage their stress and for the development of psychiatric problems. Starting early, helping them to build autonomy as preadolescents, experiencing successes and failures, begins the cultivation of resilience and meaningful confidence they will need during adolescence. Your attention and guidance can help all of your adolescent patients improve their coping and lower both their stress and their anxiety.

It seems that every week there is a new headline about the rising rates of anxiety in today’s adolescents. Schools often are asked to address high levels of stress and anxiety in their students, and the pediatrician’s office is often the first place worried parents will call. We will try to help you differentiate between what is normal – even healthy – adolescent stress, and what might represent treatable psychiatric problems. And we will review how to approach stress management with your patients and their parents. For all adolescents, even those with psychiatric diagnoses, learning to manage stress and anxiety is critical to their healthiest development into capable, confident, resilient adults.

Stress is the mental or emotional strain resulting from demanding or adverse circumstances. Anxiety is a feeling of unease about an imminent event with an uncertain outcome. An anxiety disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by a state of excessive unease leading to functional impairment. These distinctions are critical, as both stress and anxiety are normal-but-uncomfortable parts of the adolescent experience. When all of a teenager’s stress and anxiety is medicalized, it promotes avoidance, which in turn may worsen your patient’s functional impairment rather than improving it.

This is not to suggest that there are not real (and common) psychiatric illnesses that can affect the levels of anxiety in your patients. Anxiety disorders start the earliest, with separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia all having a mean onset before puberty. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in youth (30% of youth psychiatric illness), and anxiety also may be related to substance use disorders (25%), disruptive behavior disorders (20%), and mood disorders (17%). Despite the excited news coverage, there is no evidence of a statistically significant increase in the incidence of anxiety or mood disorders in young people over the past decade.

It is not difficult to imagine that the challenges facing adolescents are considerable. Of course, adolescence is a time of major change starting with puberty, in which young people actively develop independence, identity, and a rich array of deep relationships beyond their families. Typically, this is a 5- to 10-year process of risk-taking, new experiences, setbacks, delight, heartbreak, and triumphs all alongside growing autonomy.

These forces may make their parents even more stressed than the adolescents themselves, but there is one dramatically different feature of adolescent life today: the constant presence of smartphones. While these devices can improve connectedness to school, family, and friends, use of smartphones also means that today’s teenagers often have little downtime cognitively or socially. Use of smartphones can facilitate both supportive affirmation from friends and relentless social pressures, and the feeling of being excluded or bullied. Smartphone use can interfere with restful sleep, and some virtual activities may compete with the genuine experimentation and exploration where teenagers discover their interests and abilities and develop meaningful confidence and independence.

Several factors might impair an adolescent’s ability to cope with challenge and stress. Those teenagers who have not had the opportunity to face and manage modest setbacks, difficulties, and discomforts during their elementary and middle school years may be overwhelmed by starting with the higher-stakes strains of adolescence. This can happen when young children have not explored many new activities, have been shielded from the consequences of failures, or have tried only activities that came easily to them. Certainly, teenagers who are managing a depressive or anxiety disorder as well as those with learning disabilities may have limited ability to cope with routine stress, although those who have a well-treated disorder often have robust coping skills.

Perhaps obvious, but still very important, chronic sleep deprivation can leave adolescents irritable, impatient, and distractible, all of which make coping with a challenge very difficult. Likewise, substance use can directly impair coping skills, and can create the habit of trying to escape stress rather than manage it.

So what does this mean for you? If your patient has an anxiety, depressive, or substance use disorder, refer for appropriate therapy. For both those who screen in and those who do not, your next task is to help them improve their coping skills. What specifically has them so stressed?

Are there family stressors or unrealistic expectations that can be addressed? Can they see their situation as a challenge and focus on what is within their control to do in response? Remind your patients that challenges are uncomfortable. Mastery comes with practice and, inevitably, some setbacks and failures. Have they identified personal goals or a transcendent purpose? This can improve motivation and keep a challenge in perspective. They might focus on learning about their coping style: Do they do better with a slow, steady, methodical approach or intense bursts of effort? Talk with them about self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, putting effort into relaxation as well as work, and spending time with their actual (not just virtual) friends all are essential to keeping their batteries charged while doing the intense work of normal adolescence.

For those patients who do not meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders, there are circumstances in which a referral for therapy can be helpful. If they are noticeably disconnected from their parents or their parents seem to be more reactive to the stress and pressures than they are, an outside therapist can be a meaningful support as they build skills. Those patients who are socially isolated and stressed, are using substances regularly, are withdrawing from other interests to manage their source of stress, or are having difficulty telling facts from feelings are at risk for failing to adequately manage their stress and for the development of psychiatric problems. Starting early, helping them to build autonomy as preadolescents, experiencing successes and failures, begins the cultivation of resilience and meaningful confidence they will need during adolescence. Your attention and guidance can help all of your adolescent patients improve their coping and lower both their stress and their anxiety.

It seems that every week there is a new headline about the rising rates of anxiety in today’s adolescents. Schools often are asked to address high levels of stress and anxiety in their students, and the pediatrician’s office is often the first place worried parents will call. We will try to help you differentiate between what is normal – even healthy – adolescent stress, and what might represent treatable psychiatric problems. And we will review how to approach stress management with your patients and their parents. For all adolescents, even those with psychiatric diagnoses, learning to manage stress and anxiety is critical to their healthiest development into capable, confident, resilient adults.

Stress is the mental or emotional strain resulting from demanding or adverse circumstances. Anxiety is a feeling of unease about an imminent event with an uncertain outcome. An anxiety disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by a state of excessive unease leading to functional impairment. These distinctions are critical, as both stress and anxiety are normal-but-uncomfortable parts of the adolescent experience. When all of a teenager’s stress and anxiety is medicalized, it promotes avoidance, which in turn may worsen your patient’s functional impairment rather than improving it.

This is not to suggest that there are not real (and common) psychiatric illnesses that can affect the levels of anxiety in your patients. Anxiety disorders start the earliest, with separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia all having a mean onset before puberty. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in youth (30% of youth psychiatric illness), and anxiety also may be related to substance use disorders (25%), disruptive behavior disorders (20%), and mood disorders (17%). Despite the excited news coverage, there is no evidence of a statistically significant increase in the incidence of anxiety or mood disorders in young people over the past decade.

It is not difficult to imagine that the challenges facing adolescents are considerable. Of course, adolescence is a time of major change starting with puberty, in which young people actively develop independence, identity, and a rich array of deep relationships beyond their families. Typically, this is a 5- to 10-year process of risk-taking, new experiences, setbacks, delight, heartbreak, and triumphs all alongside growing autonomy.

These forces may make their parents even more stressed than the adolescents themselves, but there is one dramatically different feature of adolescent life today: the constant presence of smartphones. While these devices can improve connectedness to school, family, and friends, use of smartphones also means that today’s teenagers often have little downtime cognitively or socially. Use of smartphones can facilitate both supportive affirmation from friends and relentless social pressures, and the feeling of being excluded or bullied. Smartphone use can interfere with restful sleep, and some virtual activities may compete with the genuine experimentation and exploration where teenagers discover their interests and abilities and develop meaningful confidence and independence.

Several factors might impair an adolescent’s ability to cope with challenge and stress. Those teenagers who have not had the opportunity to face and manage modest setbacks, difficulties, and discomforts during their elementary and middle school years may be overwhelmed by starting with the higher-stakes strains of adolescence. This can happen when young children have not explored many new activities, have been shielded from the consequences of failures, or have tried only activities that came easily to them. Certainly, teenagers who are managing a depressive or anxiety disorder as well as those with learning disabilities may have limited ability to cope with routine stress, although those who have a well-treated disorder often have robust coping skills.

Perhaps obvious, but still very important, chronic sleep deprivation can leave adolescents irritable, impatient, and distractible, all of which make coping with a challenge very difficult. Likewise, substance use can directly impair coping skills, and can create the habit of trying to escape stress rather than manage it.

So what does this mean for you? If your patient has an anxiety, depressive, or substance use disorder, refer for appropriate therapy. For both those who screen in and those who do not, your next task is to help them improve their coping skills. What specifically has them so stressed?

Are there family stressors or unrealistic expectations that can be addressed? Can they see their situation as a challenge and focus on what is within their control to do in response? Remind your patients that challenges are uncomfortable. Mastery comes with practice and, inevitably, some setbacks and failures. Have they identified personal goals or a transcendent purpose? This can improve motivation and keep a challenge in perspective. They might focus on learning about their coping style: Do they do better with a slow, steady, methodical approach or intense bursts of effort? Talk with them about self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, putting effort into relaxation as well as work, and spending time with their actual (not just virtual) friends all are essential to keeping their batteries charged while doing the intense work of normal adolescence.

For those patients who do not meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders, there are circumstances in which a referral for therapy can be helpful. If they are noticeably disconnected from their parents or their parents seem to be more reactive to the stress and pressures than they are, an outside therapist can be a meaningful support as they build skills. Those patients who are socially isolated and stressed, are using substances regularly, are withdrawing from other interests to manage their source of stress, or are having difficulty telling facts from feelings are at risk for failing to adequately manage their stress and for the development of psychiatric problems. Starting early, helping them to build autonomy as preadolescents, experiencing successes and failures, begins the cultivation of resilience and meaningful confidence they will need during adolescence. Your attention and guidance can help all of your adolescent patients improve their coping and lower both their stress and their anxiety.

Anxiety disorders: Psychopharmacologic treatment update

Anxiety disorders, including separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, are some of the most common psychiatric conditions of childhood and adolescence, affecting up to 20% of youth.1 Patients commonly present with a mix of symptoms that often span multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses. While this pattern can present somewhat of a diagnostic conundrum, it can be reassuring to know that such constellations of symptoms are the rule rather than the exception. Further, given that both the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment strategies don’t change much among the various anxiety disorders, the lack of a definitive single diagnosis should not delay intervention. Be alert to the possibility that anxiety and anxiety disorders can be the engine that drives what on the surface appears to be more disruptive and oppositional behavior.

Although medications can be a useful part of treatment, they are not recommended as a stand-alone intervention. Nonpharmacologic treatments generally should be tried before medications are considered. Among the different types of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support from research trials, although other modalities such as mindfulness-based treatments show some promise. As anxiety disorders often run in families, it also can be very useful to explore the possibility that one or more parents also struggle with an anxiety disorder, which, if untreated, might complicate the child’s course.

With regard to medications, it is being increasingly appreciated that, despite SSRIs being most popularly known as antidepressants, these medications actually may be as efficacious or even more efficacious in the management of anxiety disorders. This class remains the cornerstone of medication treatment, and a brief review of current options follows.

SSRIs and SNRIs

A 2015 meta-analysis that examined nine randomized controlled trials of SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for pediatric anxiety disorders concluded that these agents provided a benefit of modest effect size. No significant increase in treatment-emergent suicidality was found, and the medications were generally well tolerated.2 This analysis also found some evidence that greater efficacy was related to a medication with more specific serotonergic properties, suggesting improved response with “true” SSRIs versus SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. One major study using sertraline found that, at least in the short term, combined use of sertraline with CBT resulted in better efficacy than either treatment alone.3 Dosing of SSRIs should start low: A general rule is to begin at half of the smallest dosage made, depending on the age and size of the patient. One question that often comes up after a successful trial is how long to continue the medications. A recent meta-analysis in adults concluded that there was evidence that stopping medication prior to 1 year resulted in an increased risk of relapse with little to guide clinicians after that 1-year mark.4

Benzodiazepines

Even though benzodiazepines have been around for a long time, data supporting their efficacy and safety in pediatric populations remain extremely limited, and what has been reported has not been particularly positive. Thus, most experts do not suggest using benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders, with the exception of helping children through single or rare events, such as medical procedures or enabling an adolescent who has been fearful of attending school to get to the building on the first day back after a long absence.

Guanfacine

In a recent exploratory trial of guanfacine for children with mixed anxiety disorders,5 the medication was well tolerated overall but did not result in statistically significant improvement relative to placebo on primary anxiety rating scales. However, a higher number of children were rated as improved on a clinician-rated scale. This medication is usually started at 0.5 mg/day and increased as tolerated, while checking vital signs, to a maximum of 4 mg/day.

Atomoxetine

A randomized control trial of pediatric patients with both ADHD and an anxiety disorder showed reductions in both symptom domains with atomoxetine dosed at an average of 1.3 mg/kg per day.6 There is little evidence to suggest its use in primary anxiety disorders without comorbid ADHD.

Buspirone

This 5-hydroxytryptamine 1a agonist has Food and Drug Administration approval for generalized anxiety disorder in adults and is generally well tolerated. Unfortunately, two randomized controlled studies in children and adolescents did not find statistically significant improvement relative to placebo, although some methodological problems may have played a role.7

Antipsychotics

Although sometimes used to augment an SSRI in adult anxiety disorders, there are little data to support the use of antipsychotics in pediatric populations, especially given the antecedent risks of the drugs.

Summary

Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders often includes the advice that, if medications are indicated in conjunction with psychotherapy, to start with an SSRI; and if that is not effective to try a different one.7 An SNRI such as venlafaxine or duloxetine may then be a third-line alternative, although for youth with comorbid ADHD, consideration of either atomoxetine or guanfacine is also reasonable. Beyond that point, there unfortunately are little systematic data to guide pharmacologic decision making, and increased potential risks of other classes of medications suggest the need for caution and consultation.

Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 12th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, on May 4, 2018,organized by the University of Vermont with Dr. Rettew as course director. Go to http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences.

References

1. Merikangas KR et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):980-9.

2. Strawn JR et al. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32(3):149-57.

3. Walkup J et al. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 25;359(26):2753-66.

4. Batelaan N et al. BMJ. 2017 Sep 13;358:j3927.

5. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;27(1): 29-37..

6. Geller D et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;46(9):1119-27.

7. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;28(1): 2-9.

Anxiety disorders, including separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, are some of the most common psychiatric conditions of childhood and adolescence, affecting up to 20% of youth.1 Patients commonly present with a mix of symptoms that often span multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses. While this pattern can present somewhat of a diagnostic conundrum, it can be reassuring to know that such constellations of symptoms are the rule rather than the exception. Further, given that both the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment strategies don’t change much among the various anxiety disorders, the lack of a definitive single diagnosis should not delay intervention. Be alert to the possibility that anxiety and anxiety disorders can be the engine that drives what on the surface appears to be more disruptive and oppositional behavior.

Although medications can be a useful part of treatment, they are not recommended as a stand-alone intervention. Nonpharmacologic treatments generally should be tried before medications are considered. Among the different types of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support from research trials, although other modalities such as mindfulness-based treatments show some promise. As anxiety disorders often run in families, it also can be very useful to explore the possibility that one or more parents also struggle with an anxiety disorder, which, if untreated, might complicate the child’s course.

With regard to medications, it is being increasingly appreciated that, despite SSRIs being most popularly known as antidepressants, these medications actually may be as efficacious or even more efficacious in the management of anxiety disorders. This class remains the cornerstone of medication treatment, and a brief review of current options follows.

SSRIs and SNRIs

A 2015 meta-analysis that examined nine randomized controlled trials of SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for pediatric anxiety disorders concluded that these agents provided a benefit of modest effect size. No significant increase in treatment-emergent suicidality was found, and the medications were generally well tolerated.2 This analysis also found some evidence that greater efficacy was related to a medication with more specific serotonergic properties, suggesting improved response with “true” SSRIs versus SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. One major study using sertraline found that, at least in the short term, combined use of sertraline with CBT resulted in better efficacy than either treatment alone.3 Dosing of SSRIs should start low: A general rule is to begin at half of the smallest dosage made, depending on the age and size of the patient. One question that often comes up after a successful trial is how long to continue the medications. A recent meta-analysis in adults concluded that there was evidence that stopping medication prior to 1 year resulted in an increased risk of relapse with little to guide clinicians after that 1-year mark.4

Benzodiazepines

Even though benzodiazepines have been around for a long time, data supporting their efficacy and safety in pediatric populations remain extremely limited, and what has been reported has not been particularly positive. Thus, most experts do not suggest using benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders, with the exception of helping children through single or rare events, such as medical procedures or enabling an adolescent who has been fearful of attending school to get to the building on the first day back after a long absence.

Guanfacine

In a recent exploratory trial of guanfacine for children with mixed anxiety disorders,5 the medication was well tolerated overall but did not result in statistically significant improvement relative to placebo on primary anxiety rating scales. However, a higher number of children were rated as improved on a clinician-rated scale. This medication is usually started at 0.5 mg/day and increased as tolerated, while checking vital signs, to a maximum of 4 mg/day.

Atomoxetine

A randomized control trial of pediatric patients with both ADHD and an anxiety disorder showed reductions in both symptom domains with atomoxetine dosed at an average of 1.3 mg/kg per day.6 There is little evidence to suggest its use in primary anxiety disorders without comorbid ADHD.

Buspirone

This 5-hydroxytryptamine 1a agonist has Food and Drug Administration approval for generalized anxiety disorder in adults and is generally well tolerated. Unfortunately, two randomized controlled studies in children and adolescents did not find statistically significant improvement relative to placebo, although some methodological problems may have played a role.7

Antipsychotics

Although sometimes used to augment an SSRI in adult anxiety disorders, there are little data to support the use of antipsychotics in pediatric populations, especially given the antecedent risks of the drugs.

Summary

Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders often includes the advice that, if medications are indicated in conjunction with psychotherapy, to start with an SSRI; and if that is not effective to try a different one.7 An SNRI such as venlafaxine or duloxetine may then be a third-line alternative, although for youth with comorbid ADHD, consideration of either atomoxetine or guanfacine is also reasonable. Beyond that point, there unfortunately are little systematic data to guide pharmacologic decision making, and increased potential risks of other classes of medications suggest the need for caution and consultation.

Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 12th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, on May 4, 2018,organized by the University of Vermont with Dr. Rettew as course director. Go to http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences.

References

1. Merikangas KR et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):980-9.

2. Strawn JR et al. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32(3):149-57.

3. Walkup J et al. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 25;359(26):2753-66.

4. Batelaan N et al. BMJ. 2017 Sep 13;358:j3927.

5. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;27(1): 29-37..

6. Geller D et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;46(9):1119-27.

7. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;28(1): 2-9.

Anxiety disorders, including separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, are some of the most common psychiatric conditions of childhood and adolescence, affecting up to 20% of youth.1 Patients commonly present with a mix of symptoms that often span multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses. While this pattern can present somewhat of a diagnostic conundrum, it can be reassuring to know that such constellations of symptoms are the rule rather than the exception. Further, given that both the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment strategies don’t change much among the various anxiety disorders, the lack of a definitive single diagnosis should not delay intervention. Be alert to the possibility that anxiety and anxiety disorders can be the engine that drives what on the surface appears to be more disruptive and oppositional behavior.

Although medications can be a useful part of treatment, they are not recommended as a stand-alone intervention. Nonpharmacologic treatments generally should be tried before medications are considered. Among the different types of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support from research trials, although other modalities such as mindfulness-based treatments show some promise. As anxiety disorders often run in families, it also can be very useful to explore the possibility that one or more parents also struggle with an anxiety disorder, which, if untreated, might complicate the child’s course.

With regard to medications, it is being increasingly appreciated that, despite SSRIs being most popularly known as antidepressants, these medications actually may be as efficacious or even more efficacious in the management of anxiety disorders. This class remains the cornerstone of medication treatment, and a brief review of current options follows.

SSRIs and SNRIs

A 2015 meta-analysis that examined nine randomized controlled trials of SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for pediatric anxiety disorders concluded that these agents provided a benefit of modest effect size. No significant increase in treatment-emergent suicidality was found, and the medications were generally well tolerated.2 This analysis also found some evidence that greater efficacy was related to a medication with more specific serotonergic properties, suggesting improved response with “true” SSRIs versus SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. One major study using sertraline found that, at least in the short term, combined use of sertraline with CBT resulted in better efficacy than either treatment alone.3 Dosing of SSRIs should start low: A general rule is to begin at half of the smallest dosage made, depending on the age and size of the patient. One question that often comes up after a successful trial is how long to continue the medications. A recent meta-analysis in adults concluded that there was evidence that stopping medication prior to 1 year resulted in an increased risk of relapse with little to guide clinicians after that 1-year mark.4

Benzodiazepines

Even though benzodiazepines have been around for a long time, data supporting their efficacy and safety in pediatric populations remain extremely limited, and what has been reported has not been particularly positive. Thus, most experts do not suggest using benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders, with the exception of helping children through single or rare events, such as medical procedures or enabling an adolescent who has been fearful of attending school to get to the building on the first day back after a long absence.

Guanfacine

In a recent exploratory trial of guanfacine for children with mixed anxiety disorders,5 the medication was well tolerated overall but did not result in statistically significant improvement relative to placebo on primary anxiety rating scales. However, a higher number of children were rated as improved on a clinician-rated scale. This medication is usually started at 0.5 mg/day and increased as tolerated, while checking vital signs, to a maximum of 4 mg/day.

Atomoxetine

A randomized control trial of pediatric patients with both ADHD and an anxiety disorder showed reductions in both symptom domains with atomoxetine dosed at an average of 1.3 mg/kg per day.6 There is little evidence to suggest its use in primary anxiety disorders without comorbid ADHD.

Buspirone

This 5-hydroxytryptamine 1a agonist has Food and Drug Administration approval for generalized anxiety disorder in adults and is generally well tolerated. Unfortunately, two randomized controlled studies in children and adolescents did not find statistically significant improvement relative to placebo, although some methodological problems may have played a role.7

Antipsychotics

Although sometimes used to augment an SSRI in adult anxiety disorders, there are little data to support the use of antipsychotics in pediatric populations, especially given the antecedent risks of the drugs.

Summary

Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders often includes the advice that, if medications are indicated in conjunction with psychotherapy, to start with an SSRI; and if that is not effective to try a different one.7 An SNRI such as venlafaxine or duloxetine may then be a third-line alternative, although for youth with comorbid ADHD, consideration of either atomoxetine or guanfacine is also reasonable. Beyond that point, there unfortunately are little systematic data to guide pharmacologic decision making, and increased potential risks of other classes of medications suggest the need for caution and consultation.

Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 12th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington, on May 4, 2018,organized by the University of Vermont with Dr. Rettew as course director. Go to http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences.

References

1. Merikangas KR et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):980-9.

2. Strawn JR et al. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32(3):149-57.

3. Walkup J et al. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 25;359(26):2753-66.

4. Batelaan N et al. BMJ. 2017 Sep 13;358:j3927.

5. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;27(1): 29-37..

6. Geller D et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;46(9):1119-27.

7. Strawn JR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2017 Feb;28(1): 2-9.

How to help children process, overcome horrific traumas

Unfathomable. Unspeakable.

These are among the terms used to describe children’s extreme traumatic experiences such as severe abuse and neglect. It is often most shocking when these acts are perpetrated by the children’s parents – the very ones that children should be able to depend on for their protection and safety.

Many believe that, in addition to the cumulative and serious nature of repetitive interpersonal traumas themselves, this betrayal of trust will result in irreparable psychological damage. Fortunately, this does not have to be the case. Children are more resilient than we realize; with safety, support, and effective treatment, they can recover from even the most extreme traumas and live healthy, productive lives.

and allow them to live in safe, stable, supportive settings while minimizing traumatic separation from siblings or further disruptions in their living situation. Acute medical problems need to be stabilized, and a thorough mental health assessment should be conducted.

Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for addressing pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49[4]:414-30). Several treatments are currently available. A few examples are trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, or TF-CBT, for children aged 3-18 years; child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) for children aged 0-6 years; a group school-based model, cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools (CBITS); and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy for teens (TARGET).

Common elements of evidence-based trauma-focused treatments are: 1) nonperpetrating caregivers are included in therapy to enhance support and understanding of the child’s trauma responses, and to address trauma-related behavioral problems; 2) skills are provided to the youth and caregiver for coping with negative trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and 3) children are supported to directly talk about and make meaning of their trauma experiences.

Through trauma-focused treatment, children become able to cope with their traumatic experiences and memories – make sense out of them. These traumas are no longer “unfathomable or “unspeakable,” but rather, manageable memories of bad experiences that the children have had the courage to face and master.

Children can recover from even extreme trauma experiences when they receive effective trauma-focused treatment in the context of a supportive environment. More information about evidence-based treatments is available from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network at www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

Unfathomable. Unspeakable.

These are among the terms used to describe children’s extreme traumatic experiences such as severe abuse and neglect. It is often most shocking when these acts are perpetrated by the children’s parents – the very ones that children should be able to depend on for their protection and safety.

Many believe that, in addition to the cumulative and serious nature of repetitive interpersonal traumas themselves, this betrayal of trust will result in irreparable psychological damage. Fortunately, this does not have to be the case. Children are more resilient than we realize; with safety, support, and effective treatment, they can recover from even the most extreme traumas and live healthy, productive lives.

and allow them to live in safe, stable, supportive settings while minimizing traumatic separation from siblings or further disruptions in their living situation. Acute medical problems need to be stabilized, and a thorough mental health assessment should be conducted.

Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for addressing pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49[4]:414-30). Several treatments are currently available. A few examples are trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, or TF-CBT, for children aged 3-18 years; child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) for children aged 0-6 years; a group school-based model, cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools (CBITS); and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy for teens (TARGET).

Common elements of evidence-based trauma-focused treatments are: 1) nonperpetrating caregivers are included in therapy to enhance support and understanding of the child’s trauma responses, and to address trauma-related behavioral problems; 2) skills are provided to the youth and caregiver for coping with negative trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and 3) children are supported to directly talk about and make meaning of their trauma experiences.

Through trauma-focused treatment, children become able to cope with their traumatic experiences and memories – make sense out of them. These traumas are no longer “unfathomable or “unspeakable,” but rather, manageable memories of bad experiences that the children have had the courage to face and master.

Children can recover from even extreme trauma experiences when they receive effective trauma-focused treatment in the context of a supportive environment. More information about evidence-based treatments is available from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network at www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

Unfathomable. Unspeakable.

These are among the terms used to describe children’s extreme traumatic experiences such as severe abuse and neglect. It is often most shocking when these acts are perpetrated by the children’s parents – the very ones that children should be able to depend on for their protection and safety.

Many believe that, in addition to the cumulative and serious nature of repetitive interpersonal traumas themselves, this betrayal of trust will result in irreparable psychological damage. Fortunately, this does not have to be the case. Children are more resilient than we realize; with safety, support, and effective treatment, they can recover from even the most extreme traumas and live healthy, productive lives.

and allow them to live in safe, stable, supportive settings while minimizing traumatic separation from siblings or further disruptions in their living situation. Acute medical problems need to be stabilized, and a thorough mental health assessment should be conducted.

Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for addressing pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49[4]:414-30). Several treatments are currently available. A few examples are trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, or TF-CBT, for children aged 3-18 years; child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) for children aged 0-6 years; a group school-based model, cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools (CBITS); and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy for teens (TARGET).

Common elements of evidence-based trauma-focused treatments are: 1) nonperpetrating caregivers are included in therapy to enhance support and understanding of the child’s trauma responses, and to address trauma-related behavioral problems; 2) skills are provided to the youth and caregiver for coping with negative trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and 3) children are supported to directly talk about and make meaning of their trauma experiences.

Through trauma-focused treatment, children become able to cope with their traumatic experiences and memories – make sense out of them. These traumas are no longer “unfathomable or “unspeakable,” but rather, manageable memories of bad experiences that the children have had the courage to face and master.

Children can recover from even extreme trauma experiences when they receive effective trauma-focused treatment in the context of a supportive environment. More information about evidence-based treatments is available from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network at www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

Antibiotic choice for acute otitis media 2018

It’s a new year and a new respiratory season so my thoughts turn to the most common infection in pediatrics where an antibiotic might appropriately be prescribed – acute otitis media (AOM). The guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics were finalized in 2012 and published in 2013 and based on data that the AAP subcommittee considered. A recommendation emerged for amoxicillin to remain the treatment of choice if an antibiotic was to be prescribed at all, leaving the observation option as a continued consideration under defined clinical circumstances. The oral alternative antibiotics recommended were amoxicillin/clavulanate and cefdinir (Pediatrics. 2013. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3488).

Since the AAP subcommittee deliberated, changes have occurred in AOM etiology and the frequency of antibiotic resistance among the common bacteria that cause the infection. Our group in Rochester (N.Y.) continues to be the only site in the United States conducting a prospective assessment of AOM; we hope our data are generalizable to the entire country, but that is not certain. In Rochester, we saw an overall drop in AOM incidence after introduction of Prevnar 7 of about 10%-15% overall and that corresponded reasonably well with the frequency of AOM caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae involving the seven serotypes in the PCV7 vaccine. We then had a rebound in AOM infections, largely caused by serotype 19A, such that the overall incidence of AOM returned back to levels nearly the same as before PCV7 by 2010. With the introduction of Prevnar 13, and the dramatic reduction of serotype 19A nasal colonization – a necessary precursor of AOM – the incidence of AOM overall fell again, and compared with the pre-PCV7 era, I estimate that we are seeing about 20%-25% less AOM today.

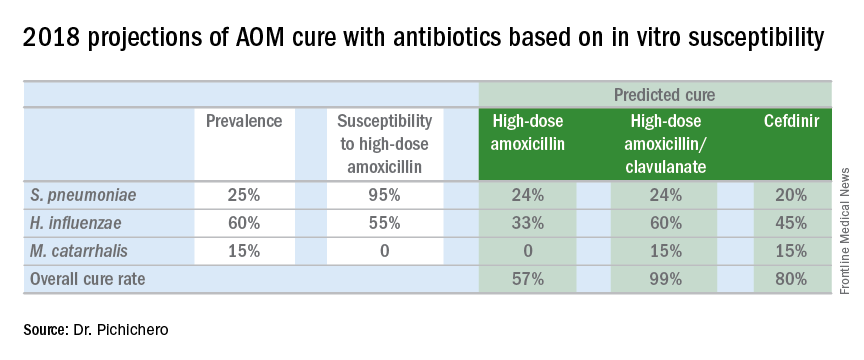

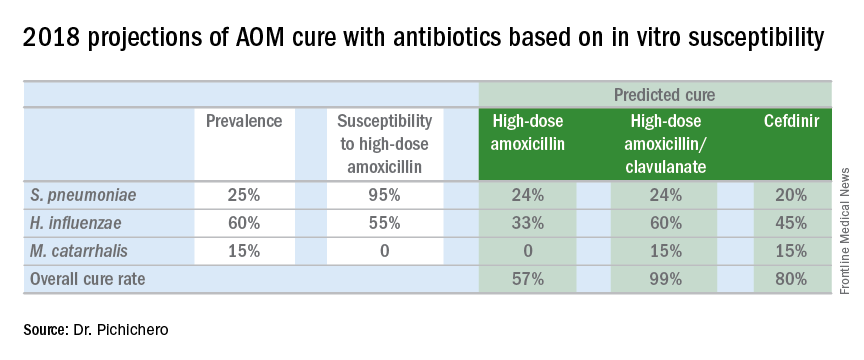

In late 2017, we published an article describing the epidemiology of AOM in the PCV era (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0181), in which we described changes in otopathogen distribution over time from 1996 through 2016. It showed that by end of 2016, the predominant bacteria causing AOM were Haemophilus influenzae, accounting for 60% of all AOM (52% detected by culture from tympanocentesis and another 8% detected by polymerase chain reaction). Among the H. influenzae from middle ear fluid, beta-lactamase production occurred in 45%. Therefore, according to principles of infectious disease antibiotic efficacy predictions, use of amoxicillin in standard dose or high dose would not eradicate about half of the H. influenzae causing AOM. In the table included in this column, I show calculations of predicted outcomes from amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and cefdinir treatment based on the projected otopathogen mix and resistance frequencies of 2016. Added to the data on H. influenzae I have included results of S. pneumoniae high nonsusceptibility at 5% of strains and beta-lactamase production by Moraxella catarrhalis at 100% of strains.

Strictly based on in vitro susceptibility and the known otopathogen mix, the calculations show that amoxicillin could result in a maximum cure of 57%, amoxicillin/clavulanate of 99%, and cefdinir of 80% of treated children.

In vitro susceptibility has its limitations. Pharmacodynamic calculations would drop the predicted success of all three antibiotics because suboptimal absorption after oral dosing occurs with amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate more so than with cefdinir, thereby resulting in lower than predicted levels of antibiotic at the site of infection within the middle ear, whereas the achievable level of cefdinir with recommended dosing sometimes is below the desired in vitro cut point.

To balance that lowered predicted efficacy, each of the otopathogens has an associated “spontaneous cure rate” that is often quoted as being 20% for S. pneumoniae, 50% for H. influenzae, and 80% for M. catarrhalis. However, to be clear, those rates were derived largely from assessments about 5 days after antibiotic treatment was started with ineffective drugs or with placebos and do not account for the true spontaneous clinical cure rate of AOM if assessed in the first few days after onset (when pain and fever are at their peak) nor if assessed 14-30 days later when almost all children have been cured by their immune systems.

The calculations also do not account for overdiagnosis in clinical practice. Indeed, if the child does not have AOM, then the child will have a cure regardless of which antibiotic is selected. Rates of overdiagnosis of AOM have been assessed with various methods and are subject to limitations. But overall the data and most experts agree that overdiagnosis by pediatricians, family physicians, urgent care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants is in the range of 30%-50%.

Before the reader leaps to the conclusion that I am endorsing any particular antibiotic strictly based on predicted in vitro efficacy, I would state that many considerations must be given to whether to use an antibiotic for AOM, and which antibiotic to use, at what dose, and for what duration. This column is just pointing out a few key up-to-date facts for your consideration.

It’s a new year and a new respiratory season so my thoughts turn to the most common infection in pediatrics where an antibiotic might appropriately be prescribed – acute otitis media (AOM). The guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics were finalized in 2012 and published in 2013 and based on data that the AAP subcommittee considered. A recommendation emerged for amoxicillin to remain the treatment of choice if an antibiotic was to be prescribed at all, leaving the observation option as a continued consideration under defined clinical circumstances. The oral alternative antibiotics recommended were amoxicillin/clavulanate and cefdinir (Pediatrics. 2013. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3488).

Since the AAP subcommittee deliberated, changes have occurred in AOM etiology and the frequency of antibiotic resistance among the common bacteria that cause the infection. Our group in Rochester (N.Y.) continues to be the only site in the United States conducting a prospective assessment of AOM; we hope our data are generalizable to the entire country, but that is not certain. In Rochester, we saw an overall drop in AOM incidence after introduction of Prevnar 7 of about 10%-15% overall and that corresponded reasonably well with the frequency of AOM caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae involving the seven serotypes in the PCV7 vaccine. We then had a rebound in AOM infections, largely caused by serotype 19A, such that the overall incidence of AOM returned back to levels nearly the same as before PCV7 by 2010. With the introduction of Prevnar 13, and the dramatic reduction of serotype 19A nasal colonization – a necessary precursor of AOM – the incidence of AOM overall fell again, and compared with the pre-PCV7 era, I estimate that we are seeing about 20%-25% less AOM today.

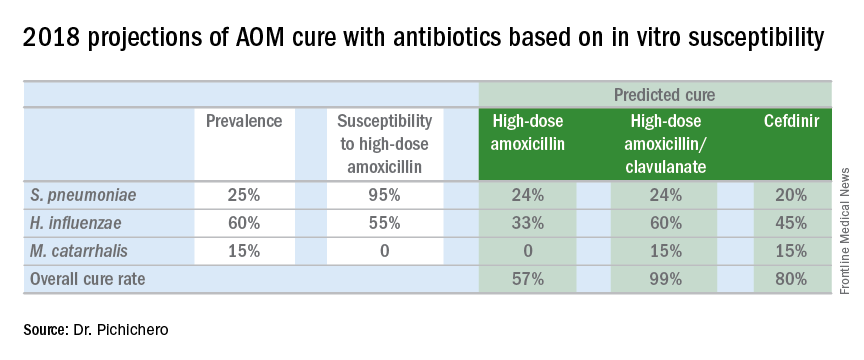

In late 2017, we published an article describing the epidemiology of AOM in the PCV era (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0181), in which we described changes in otopathogen distribution over time from 1996 through 2016. It showed that by end of 2016, the predominant bacteria causing AOM were Haemophilus influenzae, accounting for 60% of all AOM (52% detected by culture from tympanocentesis and another 8% detected by polymerase chain reaction). Among the H. influenzae from middle ear fluid, beta-lactamase production occurred in 45%. Therefore, according to principles of infectious disease antibiotic efficacy predictions, use of amoxicillin in standard dose or high dose would not eradicate about half of the H. influenzae causing AOM. In the table included in this column, I show calculations of predicted outcomes from amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and cefdinir treatment based on the projected otopathogen mix and resistance frequencies of 2016. Added to the data on H. influenzae I have included results of S. pneumoniae high nonsusceptibility at 5% of strains and beta-lactamase production by Moraxella catarrhalis at 100% of strains.

Strictly based on in vitro susceptibility and the known otopathogen mix, the calculations show that amoxicillin could result in a maximum cure of 57%, amoxicillin/clavulanate of 99%, and cefdinir of 80% of treated children.

In vitro susceptibility has its limitations. Pharmacodynamic calculations would drop the predicted success of all three antibiotics because suboptimal absorption after oral dosing occurs with amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate more so than with cefdinir, thereby resulting in lower than predicted levels of antibiotic at the site of infection within the middle ear, whereas the achievable level of cefdinir with recommended dosing sometimes is below the desired in vitro cut point.

To balance that lowered predicted efficacy, each of the otopathogens has an associated “spontaneous cure rate” that is often quoted as being 20% for S. pneumoniae, 50% for H. influenzae, and 80% for M. catarrhalis. However, to be clear, those rates were derived largely from assessments about 5 days after antibiotic treatment was started with ineffective drugs or with placebos and do not account for the true spontaneous clinical cure rate of AOM if assessed in the first few days after onset (when pain and fever are at their peak) nor if assessed 14-30 days later when almost all children have been cured by their immune systems.