User login

Guidelines are not cookbooks

For many years I have counseled medical students and residents that half of what I was taught in medical school has since been proven obsolete or frankly wrong. I counsel them that I have no reason to believe that I am any better than my professors were. So I wish them luck sorting out what is true. Earlier in my career, that warning was mild hyperbole, but not anymore.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are the most common reason for an office visit during the winter. Bronchiolitis is the most frequent diagnosis for a winter admission of an infant to a community hospital. Pediatricians have nuanced assessments and many options when treating these diseases. Best practices have changed frequently over the past 3 decades, mostly by eliminating previously espoused treatments as ineffective. In infants and young children, those obsolete treatments include decongestants and cough suppressants for young children with common colds, inhaled beta-agonists and steroids for infants with bronchiolitis, and antibiotics for simple otitis media in older children. In other words, most of what I was originally taught.

There is a discontinuity between guidelines that forbid routine steroids and beta-agonists for bronchiolitis in infants, and guidelines that strongly prescribe steroids, metered dose inhalers, and asthma action plans for all discharged wheezers over age 2 years. When I worked as a hospitalist in the pulmonology department, I frequently diagnosed asthma under age 1 year. As a general pediatric hospitalist, one winter I twice ran afoul of a hospital quality metric that benchmarked 100% compliance with providing steroids, inhaled corticosteroids, and asthma action plans on discharge for all wheezers over age 2. Fortunately for both me and the quality team working on that quality dashboard, my thorough documentation of why I didn’t think a particular wheezer had asthma was detailed enough to satisfy peer review.

Historically, medical knowledge has been dependent upon these types of observation which then are taught to the next generation of physicians and, if confirmed repeatedly, become memes with some degree of reliability. An all-too-typical Cochrane library entry may challenge these memes by looking at 200 articles, finding 20 relevant studies, selecting only 2 underpowered studies as meeting their randomized controlled trial criteria, and then concluding that there is “insufficient evidence” to prove the treatment works. But absence of proof is not proof of absence. Twenty five years after coining the phrase “evidence-based medicine,” our medical knowledge base has not been purified.

In medicine, absolute certainty isn’t possible. Using 95% confidence intervals for a research paper does not even mean it is 95% likely to be right. So part of (which is tainted with confirmation bias.) It is a very imperfect art.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

For many years I have counseled medical students and residents that half of what I was taught in medical school has since been proven obsolete or frankly wrong. I counsel them that I have no reason to believe that I am any better than my professors were. So I wish them luck sorting out what is true. Earlier in my career, that warning was mild hyperbole, but not anymore.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are the most common reason for an office visit during the winter. Bronchiolitis is the most frequent diagnosis for a winter admission of an infant to a community hospital. Pediatricians have nuanced assessments and many options when treating these diseases. Best practices have changed frequently over the past 3 decades, mostly by eliminating previously espoused treatments as ineffective. In infants and young children, those obsolete treatments include decongestants and cough suppressants for young children with common colds, inhaled beta-agonists and steroids for infants with bronchiolitis, and antibiotics for simple otitis media in older children. In other words, most of what I was originally taught.

There is a discontinuity between guidelines that forbid routine steroids and beta-agonists for bronchiolitis in infants, and guidelines that strongly prescribe steroids, metered dose inhalers, and asthma action plans for all discharged wheezers over age 2 years. When I worked as a hospitalist in the pulmonology department, I frequently diagnosed asthma under age 1 year. As a general pediatric hospitalist, one winter I twice ran afoul of a hospital quality metric that benchmarked 100% compliance with providing steroids, inhaled corticosteroids, and asthma action plans on discharge for all wheezers over age 2. Fortunately for both me and the quality team working on that quality dashboard, my thorough documentation of why I didn’t think a particular wheezer had asthma was detailed enough to satisfy peer review.

Historically, medical knowledge has been dependent upon these types of observation which then are taught to the next generation of physicians and, if confirmed repeatedly, become memes with some degree of reliability. An all-too-typical Cochrane library entry may challenge these memes by looking at 200 articles, finding 20 relevant studies, selecting only 2 underpowered studies as meeting their randomized controlled trial criteria, and then concluding that there is “insufficient evidence” to prove the treatment works. But absence of proof is not proof of absence. Twenty five years after coining the phrase “evidence-based medicine,” our medical knowledge base has not been purified.

In medicine, absolute certainty isn’t possible. Using 95% confidence intervals for a research paper does not even mean it is 95% likely to be right. So part of (which is tainted with confirmation bias.) It is a very imperfect art.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

For many years I have counseled medical students and residents that half of what I was taught in medical school has since been proven obsolete or frankly wrong. I counsel them that I have no reason to believe that I am any better than my professors were. So I wish them luck sorting out what is true. Earlier in my career, that warning was mild hyperbole, but not anymore.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are the most common reason for an office visit during the winter. Bronchiolitis is the most frequent diagnosis for a winter admission of an infant to a community hospital. Pediatricians have nuanced assessments and many options when treating these diseases. Best practices have changed frequently over the past 3 decades, mostly by eliminating previously espoused treatments as ineffective. In infants and young children, those obsolete treatments include decongestants and cough suppressants for young children with common colds, inhaled beta-agonists and steroids for infants with bronchiolitis, and antibiotics for simple otitis media in older children. In other words, most of what I was originally taught.

There is a discontinuity between guidelines that forbid routine steroids and beta-agonists for bronchiolitis in infants, and guidelines that strongly prescribe steroids, metered dose inhalers, and asthma action plans for all discharged wheezers over age 2 years. When I worked as a hospitalist in the pulmonology department, I frequently diagnosed asthma under age 1 year. As a general pediatric hospitalist, one winter I twice ran afoul of a hospital quality metric that benchmarked 100% compliance with providing steroids, inhaled corticosteroids, and asthma action plans on discharge for all wheezers over age 2. Fortunately for both me and the quality team working on that quality dashboard, my thorough documentation of why I didn’t think a particular wheezer had asthma was detailed enough to satisfy peer review.

Historically, medical knowledge has been dependent upon these types of observation which then are taught to the next generation of physicians and, if confirmed repeatedly, become memes with some degree of reliability. An all-too-typical Cochrane library entry may challenge these memes by looking at 200 articles, finding 20 relevant studies, selecting only 2 underpowered studies as meeting their randomized controlled trial criteria, and then concluding that there is “insufficient evidence” to prove the treatment works. But absence of proof is not proof of absence. Twenty five years after coining the phrase “evidence-based medicine,” our medical knowledge base has not been purified.

In medicine, absolute certainty isn’t possible. Using 95% confidence intervals for a research paper does not even mean it is 95% likely to be right. So part of (which is tainted with confirmation bias.) It is a very imperfect art.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Vaccine renaissance

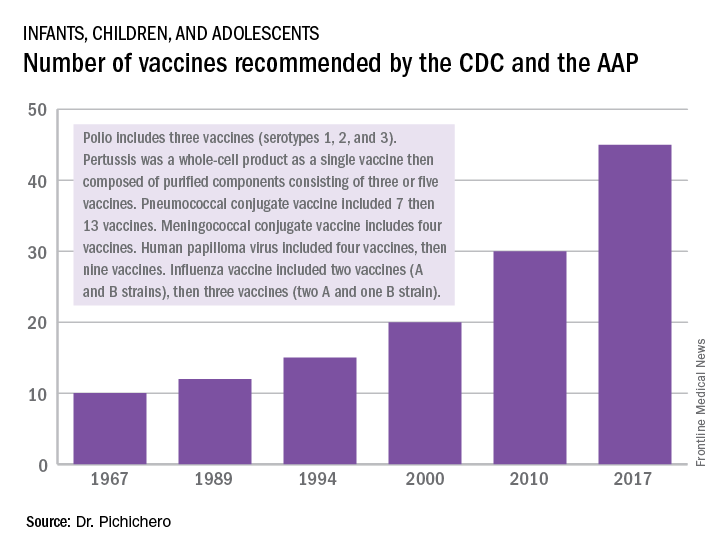

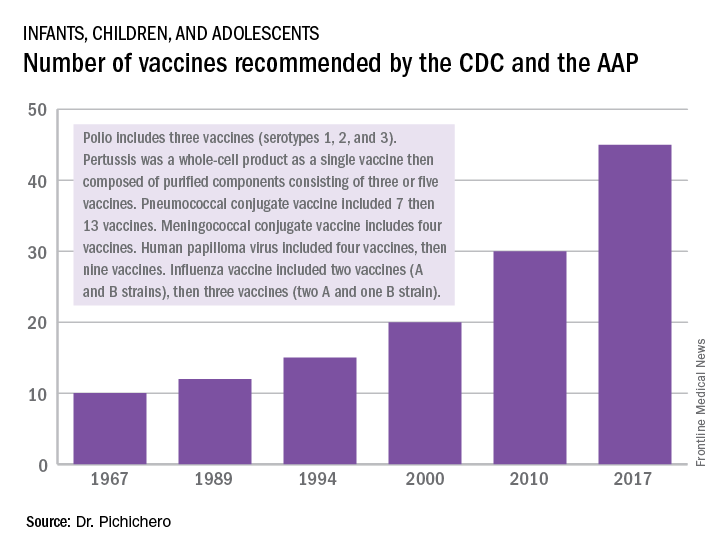

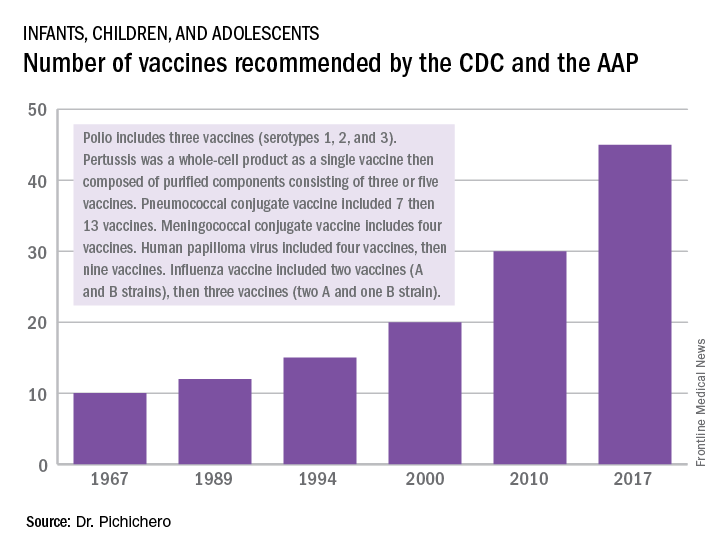

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at [email protected].

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at [email protected].

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at [email protected].

Artemisinin: Its global impact on the treatment of malaria

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Nurse practitioner/pediatrician collaboration: Try a pediatric health care/medical home model

The first nurse practitioner program owes much to Henry K. Silver, MD, a pediatrician, an endocrinologist, and a pioneer who was influential in the development of innovative educational programs for advanced pediatric health care providers. Dr. Silver, then a professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora, with Loretta Ford, EdD, a pediatric nurse and professor at the same university’s School of Nursing, developed that program in 1967 (Pediatrics. 1967;39[5]:756-60). They were responding to a serious shortage of pediatric providers, especially in rural and low socioeconomic areas. Pediatric nurses learned about primary care, office-based practice that included evaluating children with hearing and speech deficits, nutritional needs, vision impairment, and other congenital and acute problems. They made home visits and participated in follow-up of children with medical, surgical, and mental health concerns.

Now, more than 50 years later, an era when health care for children is at the forefront of policy and financial concerns, children are surviving longer with chronic and complex illness, and receive sophisticated therapies for medical and surgical problems. The definition of family is very different from that used in the 1960s, and challenges in health care provision begin with identification of basic needs such as food and shelter. In light of the risks for children today, there are many more opportunities for pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners (PNPs) to collaborate, especially in planning complex care strategies.

One example for collaboration is within the pediatric health care/medical home model (PHC/MHM). Practices, whether primary or subspecialty, can benefit patients and their families by providing a coordinated model of comprehensive care, especially for children who are at greatest identified risk. In addition, the PHC/MHM practice can receive insurance reimbursement benefits, and demonstrate a decrease in hospitalization rates, improved health care quality, and increased patient satisfaction (JAMA. 2014 Dec 24-31;312[24]:2640-8).

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines the medical home as “a model of delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, family centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective to every child and adolescent” (Pediatrics. 2002. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.184). The National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) describes the pediatric health care/medical home as a “model of care that promotes holistic care of children and their families where each patient/family has an ongoing relationship with a health care professional” (J Pediatr Health Care. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.10.010). This is an approach to providing comprehensive pediatric care that facilitates partnerships between patients, providers, and families, which is not contained within the walls of the office or building.

By virtue of their designation and training, nurses provide care for the patient in a holistic fashion, including physical care, therapeutic treatments, education, and coordination of services. Primary care nurse practitioners are trained in health promotion and prevention. They receive advanced level education in pharmacology, pathophysiology, and physical assessment, diagnosis, and management. The combination of skills between the PNP and the pediatrician are complementary and, as history suggests, can result in improved patient care. In 1967, Dr. Silver and Ms. Ford reported: “It is becoming increasingly clear that competent professional nurses working cooperatively with physicians can make greater contributions to patient care.” The PHC/MHM is an excellent opportunity for collaboration between pediatricians and NPs.

Examples of collaboration in the PHC/MHM

Building the PHC/MHM requires an evidence base, with data obtained from EHRs and current research, but also founded on individual practice culture, type of practice, and patients served. Physician and NP collaboration in collecting, reviewing, and applying this evidence can result in the development of unique guidelines for that specific practice. Patients who are considered at risk for frequent illness and hospitalizations, or who have multisystem problems, including mental health or social issues, are primary candidates who can benefit from the medical home model. The NP, by virtue of leadership training, can assist in coordinating care teams, procedures, and office staff.

Cheryl Samuels, PNP, works at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, McGovern Medical School in the UT Physicians High Risk Clinic, along with two other PNPs and two pediatricians. Their collaboration has resulted in the development of a certified health care home for children with complex illness. This practice has continued to collect data and publish research to document the effectiveness of their program. One recent study was a randomized controlled trial demonstrating cost efficiency and decreased serious illness when children with complex needs are cared for in a medical home (JAMA. 2014 Dec 24-31;312[24]:2640-8). Ms. Samuels and her colleagues published, “Case for the use of a nurse practitioner in the care of children with medical complexity,” in which they described the role of the NP and benefits in utilizing these skills in the multifaceted care of children with chronic and complex illness (Children [Basel]. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.3390/children4040024).

At the University of California, Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital, the pediatric medical home program provides primary care services and care coordination for more than 300 children, adolescents, and young adults with medical complexity. Nurse practitioner Siem Ia oversees the coordination of care for these patients, and collaborates with a team of four attending physicians, resident physicians, care coordinators, and an administrative assistant. These children have multisystem problems requiring multiple specialty services, and frequent hospitalizations. Ms. Ia works with her colleagues to ensure patients and families are provided with care that is aligned with the AAP and NAPNAP medical home principles. This team is now involved in a national collaborative project that aims to improve health outcomes for children with medical complexity, and enhance family partnerships to support the health of the child and promote family well being. She also has provided clinical expertise for the recently completed randomized, controlled trial aimed at reducing utilization for children with medical complexity through care coordination and health education.

These are just a few examples of the possibilities when pediatricians and NPs collaborate to influence and change models of primary patient care. The medical care of any child can be multifaceted, with increasing complexity, and require vigilance and thoughtful planning to be successful. Outcomes from these attempts documented in the literature include opportunities for certification and accreditation, insurance reimbursement at incentive levels, and, most importantly, patient and family satisfaction.

Dr. Haut is a PNP at Beacon Pediatrics, a large primary care practice in Rehoboth Beach, Del. She also works part time for Pediatrix Medical Group, serving the pediatric intensive care unit medical team at the Herman & Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore and as adjunct faculty at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, also in Baltimore.

The first nurse practitioner program owes much to Henry K. Silver, MD, a pediatrician, an endocrinologist, and a pioneer who was influential in the development of innovative educational programs for advanced pediatric health care providers. Dr. Silver, then a professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora, with Loretta Ford, EdD, a pediatric nurse and professor at the same university’s School of Nursing, developed that program in 1967 (Pediatrics. 1967;39[5]:756-60). They were responding to a serious shortage of pediatric providers, especially in rural and low socioeconomic areas. Pediatric nurses learned about primary care, office-based practice that included evaluating children with hearing and speech deficits, nutritional needs, vision impairment, and other congenital and acute problems. They made home visits and participated in follow-up of children with medical, surgical, and mental health concerns.

Now, more than 50 years later, an era when health care for children is at the forefront of policy and financial concerns, children are surviving longer with chronic and complex illness, and receive sophisticated therapies for medical and surgical problems. The definition of family is very different from that used in the 1960s, and challenges in health care provision begin with identification of basic needs such as food and shelter. In light of the risks for children today, there are many more opportunities for pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners (PNPs) to collaborate, especially in planning complex care strategies.

One example for collaboration is within the pediatric health care/medical home model (PHC/MHM). Practices, whether primary or subspecialty, can benefit patients and their families by providing a coordinated model of comprehensive care, especially for children who are at greatest identified risk. In addition, the PHC/MHM practice can receive insurance reimbursement benefits, and demonstrate a decrease in hospitalization rates, improved health care quality, and increased patient satisfaction (JAMA. 2014 Dec 24-31;312[24]:2640-8).

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines the medical home as “a model of delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, family centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective to every child and adolescent” (Pediatrics. 2002. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.184). The National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) describes the pediatric health care/medical home as a “model of care that promotes holistic care of children and their families where each patient/family has an ongoing relationship with a health care professional” (J Pediatr Health Care. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.10.010). This is an approach to providing comprehensive pediatric care that facilitates partnerships between patients, providers, and families, which is not contained within the walls of the office or building.

By virtue of their designation and training, nurses provide care for the patient in a holistic fashion, including physical care, therapeutic treatments, education, and coordination of services. Primary care nurse practitioners are trained in health promotion and prevention. They receive advanced level education in pharmacology, pathophysiology, and physical assessment, diagnosis, and management. The combination of skills between the PNP and the pediatrician are complementary and, as history suggests, can result in improved patient care. In 1967, Dr. Silver and Ms. Ford reported: “It is becoming increasingly clear that competent professional nurses working cooperatively with physicians can make greater contributions to patient care.” The PHC/MHM is an excellent opportunity for collaboration between pediatricians and NPs.

Examples of collaboration in the PHC/MHM

Building the PHC/MHM requires an evidence base, with data obtained from EHRs and current research, but also founded on individual practice culture, type of practice, and patients served. Physician and NP collaboration in collecting, reviewing, and applying this evidence can result in the development of unique guidelines for that specific practice. Patients who are considered at risk for frequent illness and hospitalizations, or who have multisystem problems, including mental health or social issues, are primary candidates who can benefit from the medical home model. The NP, by virtue of leadership training, can assist in coordinating care teams, procedures, and office staff.

Cheryl Samuels, PNP, works at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, McGovern Medical School in the UT Physicians High Risk Clinic, along with two other PNPs and two pediatricians. Their collaboration has resulted in the development of a certified health care home for children with complex illness. This practice has continued to collect data and publish research to document the effectiveness of their program. One recent study was a randomized controlled trial demonstrating cost efficiency and decreased serious illness when children with complex needs are cared for in a medical home (JAMA. 2014 Dec 24-31;312[24]:2640-8). Ms. Samuels and her colleagues published, “Case for the use of a nurse practitioner in the care of children with medical complexity,” in which they described the role of the NP and benefits in utilizing these skills in the multifaceted care of children with chronic and complex illness (Children [Basel]. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.3390/children4040024).

At the University of California, Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital, the pediatric medical home program provides primary care services and care coordination for more than 300 children, adolescents, and young adults with medical complexity. Nurse practitioner Siem Ia oversees the coordination of care for these patients, and collaborates with a team of four attending physicians, resident physicians, care coordinators, and an administrative assistant. These children have multisystem problems requiring multiple specialty services, and frequent hospitalizations. Ms. Ia works with her colleagues to ensure patients and families are provided with care that is aligned with the AAP and NAPNAP medical home principles. This team is now involved in a national collaborative project that aims to improve health outcomes for children with medical complexity, and enhance family partnerships to support the health of the child and promote family well being. She also has provided clinical expertise for the recently completed randomized, controlled trial aimed at reducing utilization for children with medical complexity through care coordination and health education.

These are just a few examples of the possibilities when pediatricians and NPs collaborate to influence and change models of primary patient care. The medical care of any child can be multifaceted, with increasing complexity, and require vigilance and thoughtful planning to be successful. Outcomes from these attempts documented in the literature include opportunities for certification and accreditation, insurance reimbursement at incentive levels, and, most importantly, patient and family satisfaction.

Dr. Haut is a PNP at Beacon Pediatrics, a large primary care practice in Rehoboth Beach, Del. She also works part time for Pediatrix Medical Group, serving the pediatric intensive care unit medical team at the Herman & Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore and as adjunct faculty at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, also in Baltimore.

The first nurse practitioner program owes much to Henry K. Silver, MD, a pediatrician, an endocrinologist, and a pioneer who was influential in the development of innovative educational programs for advanced pediatric health care providers. Dr. Silver, then a professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora, with Loretta Ford, EdD, a pediatric nurse and professor at the same university’s School of Nursing, developed that program in 1967 (Pediatrics. 1967;39[5]:756-60). They were responding to a serious shortage of pediatric providers, especially in rural and low socioeconomic areas. Pediatric nurses learned about primary care, office-based practice that included evaluating children with hearing and speech deficits, nutritional needs, vision impairment, and other congenital and acute problems. They made home visits and participated in follow-up of children with medical, surgical, and mental health concerns.

Now, more than 50 years later, an era when health care for children is at the forefront of policy and financial concerns, children are surviving longer with chronic and complex illness, and receive sophisticated therapies for medical and surgical problems. The definition of family is very different from that used in the 1960s, and challenges in health care provision begin with identification of basic needs such as food and shelter. In light of the risks for children today, there are many more opportunities for pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners (PNPs) to collaborate, especially in planning complex care strategies.

One example for collaboration is within the pediatric health care/medical home model (PHC/MHM). Practices, whether primary or subspecialty, can benefit patients and their families by providing a coordinated model of comprehensive care, especially for children who are at greatest identified risk. In addition, the PHC/MHM practice can receive insurance reimbursement benefits, and demonstrate a decrease in hospitalization rates, improved health care quality, and increased patient satisfaction (JAMA. 2014 Dec 24-31;312[24]:2640-8).

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines the medical home as “a model of delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, family centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective to every child and adolescent” (Pediatrics. 2002. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.184). The National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) describes the pediatric health care/medical home as a “model of care that promotes holistic care of children and their families where each patient/family has an ongoing relationship with a health care professional” (J Pediatr Health Care. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.10.010). This is an approach to providing comprehensive pediatric care that facilitates partnerships between patients, providers, and families, which is not contained within the walls of the office or building.

By virtue of their designation and training, nurses provide care for the patient in a holistic fashion, including physical care, therapeutic treatments, education, and coordination of services. Primary care nurse practitioners are trained in health promotion and prevention. They receive advanced level education in pharmacology, pathophysiology, and physical assessment, diagnosis, and management. The combination of skills between the PNP and the pediatrician are complementary and, as history suggests, can result in improved patient care. In 1967, Dr. Silver and Ms. Ford reported: “It is becoming increasingly clear that competent professional nurses working cooperatively with physicians can make greater contributions to patient care.” The PHC/MHM is an excellent opportunity for collaboration between pediatricians and NPs.

Examples of collaboration in the PHC/MHM

Building the PHC/MHM requires an evidence base, with data obtained from EHRs and current research, but also founded on individual practice culture, type of practice, and patients served. Physician and NP collaboration in collecting, reviewing, and applying this evidence can result in the development of unique guidelines for that specific practice. Patients who are considered at risk for frequent illness and hospitalizations, or who have multisystem problems, including mental health or social issues, are primary candidates who can benefit from the medical home model. The NP, by virtue of leadership training, can assist in coordinating care teams, procedures, and office staff.

Cheryl Samuels, PNP, works at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, McGovern Medical School in the UT Physicians High Risk Clinic, along with two other PNPs and two pediatricians. Their collaboration has resulted in the development of a certified health care home for children with complex illness. This practice has continued to collect data and publish research to document the effectiveness of their program. One recent study was a randomized controlled trial demonstrating cost efficiency and decreased serious illness when children with complex needs are cared for in a medical home (JAMA. 2014 Dec 24-31;312[24]:2640-8). Ms. Samuels and her colleagues published, “Case for the use of a nurse practitioner in the care of children with medical complexity,” in which they described the role of the NP and benefits in utilizing these skills in the multifaceted care of children with chronic and complex illness (Children [Basel]. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.3390/children4040024).

At the University of California, Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital, the pediatric medical home program provides primary care services and care coordination for more than 300 children, adolescents, and young adults with medical complexity. Nurse practitioner Siem Ia oversees the coordination of care for these patients, and collaborates with a team of four attending physicians, resident physicians, care coordinators, and an administrative assistant. These children have multisystem problems requiring multiple specialty services, and frequent hospitalizations. Ms. Ia works with her colleagues to ensure patients and families are provided with care that is aligned with the AAP and NAPNAP medical home principles. This team is now involved in a national collaborative project that aims to improve health outcomes for children with medical complexity, and enhance family partnerships to support the health of the child and promote family well being. She also has provided clinical expertise for the recently completed randomized, controlled trial aimed at reducing utilization for children with medical complexity through care coordination and health education.

These are just a few examples of the possibilities when pediatricians and NPs collaborate to influence and change models of primary patient care. The medical care of any child can be multifaceted, with increasing complexity, and require vigilance and thoughtful planning to be successful. Outcomes from these attempts documented in the literature include opportunities for certification and accreditation, insurance reimbursement at incentive levels, and, most importantly, patient and family satisfaction.

Dr. Haut is a PNP at Beacon Pediatrics, a large primary care practice in Rehoboth Beach, Del. She also works part time for Pediatrix Medical Group, serving the pediatric intensive care unit medical team at the Herman & Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore and as adjunct faculty at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, also in Baltimore.

You can help with behavior of children with autism spectrum disorder

There are lots of reasons you may be eager to refer children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to specialty agencies. You want the fastest possible entry for the child into intervention and the families into a support system. , as well as the general health care, of their children.

“Wait!” you say, “I do not have the special knowledge to help with behavior of children with autism! There is much you can and should do, however, as the specialist(s) may not provide such guidance, entry into behavioral services may take months, and behavior issues may feel urgent to families.

So pick an example of a behavior that is concerning to the family. One problem might be lack of cooperation with activities of daily living such as eating. In this case, the A is being asked to stop playing and sit at the table; the B may be refusing to eat what is served or even to sit very long, ending in a tantrum that disrupts the family meal; and the C could be the child being sent from the table to play on their iPad. But what is the G?

Lack of social communication skills, restrictive interests, hypersensitivity, lack of coordination, and ADHD all may be playing a role. Lack of communication skills makes the social aspect of meals uninteresting. Giving verbal reasons for joining the family may not be effective. Hypersensitivity often is associated with extremes of food selectivity. Lack of fine motor coordination makes eating soup a challenge. And ADHD makes sitting for a long time difficult!

But what about that tantrum? Tantrums that are reinforced by allowing the child to leave and play on the iPad easily can turn into a chronic escape mechanism. Instead, parents need to watch for increasing restlessness, and allow the child to signal “all done” and be “excused” before any tantrum begins. Use of the iPad (a reward) should not be allowed until the family meal is over for everyone. Such accommodations are best decided on by all caregivers in advance, ideally also involving the higher-functioning child. A caregiver who persists in thinking that the child “should” be able to behave may be in denial or grief, and deserves counseling on ASD.

But he is so rigid, the parents say! The tendency of children with ASD to like sameness can be an asset to easing behavior. The key is to design and stick to routines as much as possible, 7 days per week. If the meal is at the same time each day, in the same seat, with the same plate, with no iPad, and the child is allowed to leave only after requesting to, the entire sequence is likely to be smoother. While flexibility does not come easily, it is acquired from the natural variability in family life, but only gradually and over time.

Creating and rehearsing “social stories” is an evidence-based way to help children with ASD have acceptable behaviors. Books, storyboards, and visual schedulers can be purchased to help. But even taking photos or a video of the components of a task and posting this online (private YouTube channel) or on the refrigerator, to review before, during, and/or after the activity, builds an internal image for the child. Children with ASD often watch the same YouTube videos over and over again, and even memorize and use chunks of the speech or songs at other times. Families can capitalize on this kind of repetition by using routines and songs to improve skills.

What to do when she only cares about her iPad? It is sometimes difficult to identify reinforcers to use to strengthen desired behaviors in a child with ASD. A smile or a hug or even candy may not be valued. Help parents think about an object, song, or touch the child tends to like. Media are a strong reinforcer, but need to be used sparingly, in specific situations, and kept under parental control, or else removing them can become a major source of upsets.

When a child with ASD gets upset or even violent, the behavior may be interpreted as defiance; it may scare or upset the whole family, and is not conducive to problem solving. Siblings may start screaming or begging for the parents to stop the behavior. While this creates a crisis, you can advise parents to first ensure that everyone is safe, take deep breaths, and then think about which gap is being stressed. A subtle change from what the child expected – new furniture, a guest at the table, a day off from school, or being interrupted mid video – can cause panic, especially for anxious children. Children with ASD also may act up when uncomfortable from a headache, tooth pain, constipation, hunger, or lack of sleep, but often are unable to vocalize the reason, even if they are verbal. Having parents make a few notes about the As, Bs, Cs, and Gs of each event (the essence of a functional behavioral assessment) to review with the child, each other, the teacher, or you is key to understanding the child with ASD and successfully shifting his behavior.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

There are lots of reasons you may be eager to refer children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to specialty agencies. You want the fastest possible entry for the child into intervention and the families into a support system. , as well as the general health care, of their children.

“Wait!” you say, “I do not have the special knowledge to help with behavior of children with autism! There is much you can and should do, however, as the specialist(s) may not provide such guidance, entry into behavioral services may take months, and behavior issues may feel urgent to families.

So pick an example of a behavior that is concerning to the family. One problem might be lack of cooperation with activities of daily living such as eating. In this case, the A is being asked to stop playing and sit at the table; the B may be refusing to eat what is served or even to sit very long, ending in a tantrum that disrupts the family meal; and the C could be the child being sent from the table to play on their iPad. But what is the G?

Lack of social communication skills, restrictive interests, hypersensitivity, lack of coordination, and ADHD all may be playing a role. Lack of communication skills makes the social aspect of meals uninteresting. Giving verbal reasons for joining the family may not be effective. Hypersensitivity often is associated with extremes of food selectivity. Lack of fine motor coordination makes eating soup a challenge. And ADHD makes sitting for a long time difficult!

But what about that tantrum? Tantrums that are reinforced by allowing the child to leave and play on the iPad easily can turn into a chronic escape mechanism. Instead, parents need to watch for increasing restlessness, and allow the child to signal “all done” and be “excused” before any tantrum begins. Use of the iPad (a reward) should not be allowed until the family meal is over for everyone. Such accommodations are best decided on by all caregivers in advance, ideally also involving the higher-functioning child. A caregiver who persists in thinking that the child “should” be able to behave may be in denial or grief, and deserves counseling on ASD.

But he is so rigid, the parents say! The tendency of children with ASD to like sameness can be an asset to easing behavior. The key is to design and stick to routines as much as possible, 7 days per week. If the meal is at the same time each day, in the same seat, with the same plate, with no iPad, and the child is allowed to leave only after requesting to, the entire sequence is likely to be smoother. While flexibility does not come easily, it is acquired from the natural variability in family life, but only gradually and over time.

Creating and rehearsing “social stories” is an evidence-based way to help children with ASD have acceptable behaviors. Books, storyboards, and visual schedulers can be purchased to help. But even taking photos or a video of the components of a task and posting this online (private YouTube channel) or on the refrigerator, to review before, during, and/or after the activity, builds an internal image for the child. Children with ASD often watch the same YouTube videos over and over again, and even memorize and use chunks of the speech or songs at other times. Families can capitalize on this kind of repetition by using routines and songs to improve skills.

What to do when she only cares about her iPad? It is sometimes difficult to identify reinforcers to use to strengthen desired behaviors in a child with ASD. A smile or a hug or even candy may not be valued. Help parents think about an object, song, or touch the child tends to like. Media are a strong reinforcer, but need to be used sparingly, in specific situations, and kept under parental control, or else removing them can become a major source of upsets.

When a child with ASD gets upset or even violent, the behavior may be interpreted as defiance; it may scare or upset the whole family, and is not conducive to problem solving. Siblings may start screaming or begging for the parents to stop the behavior. While this creates a crisis, you can advise parents to first ensure that everyone is safe, take deep breaths, and then think about which gap is being stressed. A subtle change from what the child expected – new furniture, a guest at the table, a day off from school, or being interrupted mid video – can cause panic, especially for anxious children. Children with ASD also may act up when uncomfortable from a headache, tooth pain, constipation, hunger, or lack of sleep, but often are unable to vocalize the reason, even if they are verbal. Having parents make a few notes about the As, Bs, Cs, and Gs of each event (the essence of a functional behavioral assessment) to review with the child, each other, the teacher, or you is key to understanding the child with ASD and successfully shifting his behavior.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

There are lots of reasons you may be eager to refer children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to specialty agencies. You want the fastest possible entry for the child into intervention and the families into a support system. , as well as the general health care, of their children.

“Wait!” you say, “I do not have the special knowledge to help with behavior of children with autism! There is much you can and should do, however, as the specialist(s) may not provide such guidance, entry into behavioral services may take months, and behavior issues may feel urgent to families.

So pick an example of a behavior that is concerning to the family. One problem might be lack of cooperation with activities of daily living such as eating. In this case, the A is being asked to stop playing and sit at the table; the B may be refusing to eat what is served or even to sit very long, ending in a tantrum that disrupts the family meal; and the C could be the child being sent from the table to play on their iPad. But what is the G?

Lack of social communication skills, restrictive interests, hypersensitivity, lack of coordination, and ADHD all may be playing a role. Lack of communication skills makes the social aspect of meals uninteresting. Giving verbal reasons for joining the family may not be effective. Hypersensitivity often is associated with extremes of food selectivity. Lack of fine motor coordination makes eating soup a challenge. And ADHD makes sitting for a long time difficult!

But what about that tantrum? Tantrums that are reinforced by allowing the child to leave and play on the iPad easily can turn into a chronic escape mechanism. Instead, parents need to watch for increasing restlessness, and allow the child to signal “all done” and be “excused” before any tantrum begins. Use of the iPad (a reward) should not be allowed until the family meal is over for everyone. Such accommodations are best decided on by all caregivers in advance, ideally also involving the higher-functioning child. A caregiver who persists in thinking that the child “should” be able to behave may be in denial or grief, and deserves counseling on ASD.

But he is so rigid, the parents say! The tendency of children with ASD to like sameness can be an asset to easing behavior. The key is to design and stick to routines as much as possible, 7 days per week. If the meal is at the same time each day, in the same seat, with the same plate, with no iPad, and the child is allowed to leave only after requesting to, the entire sequence is likely to be smoother. While flexibility does not come easily, it is acquired from the natural variability in family life, but only gradually and over time.

Creating and rehearsing “social stories” is an evidence-based way to help children with ASD have acceptable behaviors. Books, storyboards, and visual schedulers can be purchased to help. But even taking photos or a video of the components of a task and posting this online (private YouTube channel) or on the refrigerator, to review before, during, and/or after the activity, builds an internal image for the child. Children with ASD often watch the same YouTube videos over and over again, and even memorize and use chunks of the speech or songs at other times. Families can capitalize on this kind of repetition by using routines and songs to improve skills.

What to do when she only cares about her iPad? It is sometimes difficult to identify reinforcers to use to strengthen desired behaviors in a child with ASD. A smile or a hug or even candy may not be valued. Help parents think about an object, song, or touch the child tends to like. Media are a strong reinforcer, but need to be used sparingly, in specific situations, and kept under parental control, or else removing them can become a major source of upsets.

When a child with ASD gets upset or even violent, the behavior may be interpreted as defiance; it may scare or upset the whole family, and is not conducive to problem solving. Siblings may start screaming or begging for the parents to stop the behavior. While this creates a crisis, you can advise parents to first ensure that everyone is safe, take deep breaths, and then think about which gap is being stressed. A subtle change from what the child expected – new furniture, a guest at the table, a day off from school, or being interrupted mid video – can cause panic, especially for anxious children. Children with ASD also may act up when uncomfortable from a headache, tooth pain, constipation, hunger, or lack of sleep, but often are unable to vocalize the reason, even if they are verbal. Having parents make a few notes about the As, Bs, Cs, and Gs of each event (the essence of a functional behavioral assessment) to review with the child, each other, the teacher, or you is key to understanding the child with ASD and successfully shifting his behavior.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - November 2017

The patient was diagnosed with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) based on clinical presentation of the lesions and associated symptoms of arthralgia and abdominal pain. Urinalysis was obtained and found to be unremarkable, at presentation and follow-up, and treatment with naproxen 5 mg/kg divided into two doses per day was started for pain relief. A prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg per day for 3 weeks also was started due to the presence of severe abdominal pain and bullae on exam. The patient was followed with regular urine studies and blood pressure checks for 2 months, and these also were within normal limits.

HSP, also known as anaphylactoid purpura and immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is a small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by the perivascular deposition of IgA1-based immune complexes in the walls of arterioles and postcapillary venules.1 In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves spontaneously in 4-6 weeks and does not require any specific treatment,2 although NSAIDs and systemic corticosteroids can be used for mild-to-moderate and severe pain, respectively.3

HSP is the most common vasculitis in children, with a peak incidence in boys under the age of 5 years. It occurs worldwide, more commonly among whites and Asians, less commonly among blacks, and recent studies from the Czech Republic,4 Taiwan,5 Spain,6 France,7 South Korea,8 and the United Kingdom9 have shown similar incidence rates of 10-20 per 100,000 children. HSP does occur in adults, but is less common, and is known to carry a worse prognosis – in particular, a higher risk of progression to chronic kidney disease. The disease is more commonly seen in winter months,1 unsurprisingly as upper respiratory tract infections also are more common in these months.10

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of HSP is the subject of ongoing investigation and continued controversy. Mutations and polymorphisms in mannose-binding lectin, interleukins 1 and 8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and alpha-1-antitrypsin have been associated with HSP.3 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) normally exists in two heavily glycosylated forms – IgA1 and IgA2. Abnormal glycosylation, particularly undergalactosylation, of IgA1, the predominant form of IgA in serum and mucosal secretions, has been linked to HSP.11 HSP has been associated with group A streptococcal infections, Bartonella henselae (cat scratch fever) and numerous drugs,12 although no definitive causal or mechanistic explanation has been identified.

Diagnosis

Two major diagnostic criteria for HSP are widely in use, one developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 199013 and the other by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2005.14 Both the ACR and EULAR criteria include acute abdominal pain, purpura, and microscopic evidence of vasculitis. Almost all patients with HSP have cutaneous purpura, and many of these patients have palpable purpura, which is pathognomonic of a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, but palpable purpura is not needed for diagnosis. The ACR criteria additionally include age of 20 years or younger, while the EULAR criteria include arthralgias and the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Ancillary testing usually is not required to make the diagnosis, but when the diagnosis is not clear histopathologic analysis of a skin sample can identify leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Other laboratory studies that may be needed to rule out other conditions, as well as other organ involvement, include a complete blood count, which can be done to rule out thrombocytopenia as a cause of purpura, a metabolic panel, coagulation studies, occult blood test of stool, abdominal imaging, and urinalysis (UA), which can identify proteinuria or hematuria.

Abdominal pain in HSP is believed to be a result of vasculitis of the gastric, mesenteric, and/or colic vasculature. Bleeding from the inflamed vasculature rarely can lead to gross hematochezia, frank melena, or hematemesis. One serious, potential complication of HSP-related mesenteric vasculitis is intussusception, which is otherwise rare in children older than 2 years. Intussusception should be suspected if features of the classic triad of episodic abdominal pain, sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stool are present. Abdominal ultrasound can help to determine whether intussusception is present.

The purpura in HSP presents in waves or crops, and crops last 5-10 days each. Complete resolution takes 4-6 weeks. If biopsy is desired to confirm the diagnosis, it should be done on a lesion less than 24 hours old. This allows for identification of perivascular IgA on histopathology: beyond 24 hours, IgG and IgM also leak out, contributing to a less specific histopathologic picture.

Accurate diagnosis of HSP is important to guide therapy and anticipate potential complications. Wegener’s granulomatosis (A), also known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, classically involves the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys, leading to a presentation of epistaxis, cough, and hypertension. It occurs more commonly in adults than children. Finkelstein disease (B), also known as acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), is characterized by the development of petechial, urticarial, or targetoid plaques over 24-48 hours with tender edema and fever in children aged less than 2 years. Unlike HSP, AHEI typically does not involve the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, or joints. Biopsy of skin lesions of AHEI reveals IgA deposition and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, leading some authors to consider it a closely related entity to HSP. Microscopic polyangiitis (D) is an uncommon pauci-immune vasculitis similar to Wegener’s granulomatosis, but lacking granulomas. It presents typically in the 5th decade of life with fever, fatigue, weight loss, and renal involvement. IgA nephropathy (E), also known as synpharyngitic nephritis and Berger disease, is less likely than HSP to cause a rash, joint pain, or abdominal pain. The nomenclature of HSP (whose alternate name is IgA vasculitis) reflects the multi-organ nature of HSP in comparison to IgA nephropathy, which is more likely to be limited to the kidneys.

Treatment

Aside from intussusception and renal disease, which may result from HSP, treatment is not typically required for HSP as it resolves spontaneously. Patients with significant arthralgias are likely to benefit from NSAIDs such as naproxen 5-20 mg/kg per day, although NSAIDs should be avoided if there is significant renal dysfunction or GI bleeding. Patients with severe abdominal pain or joint pain may be more likely to benefit from oral corticosteroids, particularly prednisone 1-2 mg/kg per day. A meta-analysis showed that corticosteroids significantly reduce the duration of symptoms if given early in the course of disease.15

The prognosis is usually excellent, except for a very small sample of the population (5%) that can develop end-stage renal disease. It is recommended that all children with HSP continue monitoring blood pressure and UA either weekly or biweekly for the first 2 months and then once a month for 6-12 months.16

First described in 1801 by a British physician, HSP is a common and usually self-limited disease for which our understanding has advanced greatly over the past 2 centuries, yet for which many important questions regarding pathophysiology remain unanswered. No diagnostic tests or treatments are needed for the majority of patients. Providers should include HSP in the differential diagnosis for the child with unexplained abdominal pain, renal dysfunction, or nonthrombocytopenic purpura.

Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a practicing dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group in La Mesa, California. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. “Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence”, 5th ed. (New York: Elsevier, 2016).

2. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):976-8.

3. “Dermatology”, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012).

4. J Rheumatol. 2004 Nov;31(11):2295-9.

5. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 May;44(5):618-22.

6. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014 Mar;93(2):106-13.

7. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(8):1358-66.

8. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Feb;29(2):198-203.

9. Lancet. 2002 Oct 19;360(9341):1197-202.

10. Rhinology. 2015 Jun;53(2):99-106.

11. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 21;11(11):e0166700.

12. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Jan;21(1):28-31.

13. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1114-21.

14. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):936-41.

15. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1079-87.

16. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Nov;95(11):877-82.

The patient was diagnosed with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) based on clinical presentation of the lesions and associated symptoms of arthralgia and abdominal pain. Urinalysis was obtained and found to be unremarkable, at presentation and follow-up, and treatment with naproxen 5 mg/kg divided into two doses per day was started for pain relief. A prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg per day for 3 weeks also was started due to the presence of severe abdominal pain and bullae on exam. The patient was followed with regular urine studies and blood pressure checks for 2 months, and these also were within normal limits.

HSP, also known as anaphylactoid purpura and immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is a small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by the perivascular deposition of IgA1-based immune complexes in the walls of arterioles and postcapillary venules.1 In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves spontaneously in 4-6 weeks and does not require any specific treatment,2 although NSAIDs and systemic corticosteroids can be used for mild-to-moderate and severe pain, respectively.3

HSP is the most common vasculitis in children, with a peak incidence in boys under the age of 5 years. It occurs worldwide, more commonly among whites and Asians, less commonly among blacks, and recent studies from the Czech Republic,4 Taiwan,5 Spain,6 France,7 South Korea,8 and the United Kingdom9 have shown similar incidence rates of 10-20 per 100,000 children. HSP does occur in adults, but is less common, and is known to carry a worse prognosis – in particular, a higher risk of progression to chronic kidney disease. The disease is more commonly seen in winter months,1 unsurprisingly as upper respiratory tract infections also are more common in these months.10

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of HSP is the subject of ongoing investigation and continued controversy. Mutations and polymorphisms in mannose-binding lectin, interleukins 1 and 8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and alpha-1-antitrypsin have been associated with HSP.3 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) normally exists in two heavily glycosylated forms – IgA1 and IgA2. Abnormal glycosylation, particularly undergalactosylation, of IgA1, the predominant form of IgA in serum and mucosal secretions, has been linked to HSP.11 HSP has been associated with group A streptococcal infections, Bartonella henselae (cat scratch fever) and numerous drugs,12 although no definitive causal or mechanistic explanation has been identified.

Diagnosis

Two major diagnostic criteria for HSP are widely in use, one developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 199013 and the other by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2005.14 Both the ACR and EULAR criteria include acute abdominal pain, purpura, and microscopic evidence of vasculitis. Almost all patients with HSP have cutaneous purpura, and many of these patients have palpable purpura, which is pathognomonic of a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, but palpable purpura is not needed for diagnosis. The ACR criteria additionally include age of 20 years or younger, while the EULAR criteria include arthralgias and the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Ancillary testing usually is not required to make the diagnosis, but when the diagnosis is not clear histopathologic analysis of a skin sample can identify leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Other laboratory studies that may be needed to rule out other conditions, as well as other organ involvement, include a complete blood count, which can be done to rule out thrombocytopenia as a cause of purpura, a metabolic panel, coagulation studies, occult blood test of stool, abdominal imaging, and urinalysis (UA), which can identify proteinuria or hematuria.

Abdominal pain in HSP is believed to be a result of vasculitis of the gastric, mesenteric, and/or colic vasculature. Bleeding from the inflamed vasculature rarely can lead to gross hematochezia, frank melena, or hematemesis. One serious, potential complication of HSP-related mesenteric vasculitis is intussusception, which is otherwise rare in children older than 2 years. Intussusception should be suspected if features of the classic triad of episodic abdominal pain, sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stool are present. Abdominal ultrasound can help to determine whether intussusception is present.

The purpura in HSP presents in waves or crops, and crops last 5-10 days each. Complete resolution takes 4-6 weeks. If biopsy is desired to confirm the diagnosis, it should be done on a lesion less than 24 hours old. This allows for identification of perivascular IgA on histopathology: beyond 24 hours, IgG and IgM also leak out, contributing to a less specific histopathologic picture.

Accurate diagnosis of HSP is important to guide therapy and anticipate potential complications. Wegener’s granulomatosis (A), also known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, classically involves the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys, leading to a presentation of epistaxis, cough, and hypertension. It occurs more commonly in adults than children. Finkelstein disease (B), also known as acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), is characterized by the development of petechial, urticarial, or targetoid plaques over 24-48 hours with tender edema and fever in children aged less than 2 years. Unlike HSP, AHEI typically does not involve the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, or joints. Biopsy of skin lesions of AHEI reveals IgA deposition and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, leading some authors to consider it a closely related entity to HSP. Microscopic polyangiitis (D) is an uncommon pauci-immune vasculitis similar to Wegener’s granulomatosis, but lacking granulomas. It presents typically in the 5th decade of life with fever, fatigue, weight loss, and renal involvement. IgA nephropathy (E), also known as synpharyngitic nephritis and Berger disease, is less likely than HSP to cause a rash, joint pain, or abdominal pain. The nomenclature of HSP (whose alternate name is IgA vasculitis) reflects the multi-organ nature of HSP in comparison to IgA nephropathy, which is more likely to be limited to the kidneys.

Treatment

Aside from intussusception and renal disease, which may result from HSP, treatment is not typically required for HSP as it resolves spontaneously. Patients with significant arthralgias are likely to benefit from NSAIDs such as naproxen 5-20 mg/kg per day, although NSAIDs should be avoided if there is significant renal dysfunction or GI bleeding. Patients with severe abdominal pain or joint pain may be more likely to benefit from oral corticosteroids, particularly prednisone 1-2 mg/kg per day. A meta-analysis showed that corticosteroids significantly reduce the duration of symptoms if given early in the course of disease.15

The prognosis is usually excellent, except for a very small sample of the population (5%) that can develop end-stage renal disease. It is recommended that all children with HSP continue monitoring blood pressure and UA either weekly or biweekly for the first 2 months and then once a month for 6-12 months.16

First described in 1801 by a British physician, HSP is a common and usually self-limited disease for which our understanding has advanced greatly over the past 2 centuries, yet for which many important questions regarding pathophysiology remain unanswered. No diagnostic tests or treatments are needed for the majority of patients. Providers should include HSP in the differential diagnosis for the child with unexplained abdominal pain, renal dysfunction, or nonthrombocytopenic purpura.

Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a practicing dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group in La Mesa, California. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. “Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence”, 5th ed. (New York: Elsevier, 2016).

2. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):976-8.

3. “Dermatology”, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012).

4. J Rheumatol. 2004 Nov;31(11):2295-9.

5. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 May;44(5):618-22.

6. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014 Mar;93(2):106-13.

7. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(8):1358-66.

8. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Feb;29(2):198-203.

9. Lancet. 2002 Oct 19;360(9341):1197-202.

10. Rhinology. 2015 Jun;53(2):99-106.

11. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 21;11(11):e0166700.

12. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Jan;21(1):28-31.

13. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1114-21.

14. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):936-41.

15. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1079-87.