User login

Boldly Going (Where No Journal Has Gone Before)

On a recent visit to my daughter’s school, I caught sight of a set of encyclopedias on the shelf. It brought me back to the days where I would open my own set to find out the information I needed to write reports for school. But my sense of nostalgia was short lived as I thought about all of the limitations of the format. If it wasn’t in the encyclopedias, I couldn’t write the report and would need to head to the library. The Internet changed all of that. Now, when I want to know something I don’t look it up in a book anymore. I ask Siri or Alexa or head to the Google home page. When one of my kids asks me a question I can’t answer, like how a tornado forms, I take out my phone and search for the answer on the Internet.

When it comes to medical information, I can’t remember the last time I opened up a journal sitting on my shelf and leafed through the contents to identify the article I needed. I simply go online and search PubMed or download the article from the AJO website. My office is no longer filled with volumes of journals, and I need only my phone to research whatever topic I’m interested in.

The way I prefer to prepare for cases has changed as well. In the past I would simply open a book or technique article and read about the best way to perform the case. Now, I prefer to watch a video or download the technique guide. I find it easier and faster than reading a book chapter or article.

When we began to change the format of the journal, we stated that AJO would be filled with practical information that would be directly impactful to your practice. That’s the number one criteria we utilize when evaluating content. We wanted to make AJO the journal you wanted to read, because it would improve your knowledge, your outcomes, and your bottom line. We have made many changes to AJO in the last 2 years of print issues. But to truly provide the experience our readers demand and deserve, we have to take a huge next step. Right now we are limited by page and word counts, printed media, and advertising pages. We receive hundreds of submissions a month, yet can only print a fraction of the great material we receive.

If you’ve been following the journal for the last 24 months, you’ve noticed that we have been testing the limits of printed media. We’ve included QR codes for videos, companion PDFs, patient information sheets, and downloadable reports to incorporate into your practice.

The way we access the journal is also changing. We’ve looked closely at our web statistics since the redesign. Our website visits have gone up by a factor of 6 with nearly half of our website traffic coming from mobile usage. It became clear that the days of the printed journal are slowly coming to an end. Surgeons don’t have time to read the journal cover to cover, and now most of our traffic comes from our eBlasts. Surgeons find an article that catches their eye and click a link to find out more. We’ve dramatically increased our eBlasts, and our website volume has been increasing exponentially.

While these small steps have been met with great success, it’s now time to make a giant leap. But unlike most journals, where the online version is just an electronic copy of the printed book, we wanted to make the new AJO something vastly different. We wanted to change the way surgeons utilized a journal and interacted with it on a daily basis. We wanted to be the electronic companion to your practice; a trusted, media rich, peer-reviewed source where you and your patients can turn to for the practical day-to-day information you can use to improve your practice.

We’ve built it, and now I’m proud to unveil it. Beginning January 1, AJO will be published exclusively online. All articles will still be PubMed cited, but will contain more photos, videos, handouts and all the information you need to replicate the findings or procedures in your practice. For example, new surgical techniques will be published with the presenting surgeon’s preference cards, rehab protocols, surgical video, and a PowerPoint presentation that can be presented to referral sources or prospective patients.

New features on our web portal will include:

An orthopedic product guide: A database organized by pathology which contains all of the relevant orthopedic products that could be used for treatment. Relevant products will be cross-referenced to articles so you can quickly identify and order equipment for new cases.

Smart article selection: You can filter the articles that match your interests and have them delivered directly to your inbox. For example, foot and ankle surgeons will no longer need to sift through hundreds of pages to find articles relevant to their practice.

A coding and billing section: Discuss and share tips and tricks with your peers and ask questions of the experts. Regular articles will present relevant codes and how to use them appropriately to get the reimbursement you deserve for your services.

Practice management and business strategies: Get advice from, and interact with, the experts in all areas of your practice.

Ask the experts: Present your cases to our editorial board and enjoy a written, peer-reviewed response. Discuss cases and mutual challenges in communities organized by subspecialty and sport. Cover a high school football team? Imagine a place where you can present your football-related injury to the world’s best football doctors and have them review and comment on the case.

These are just some of the changes you will see in the coming months. We will continuously work to improve and welcome your future suggestions as to how we can provide a truly valuable, customized journal.

Looking to the future, it is my opinion that patient-reported outcome scores will be a large part of what we do. By presenting our successful outcomes, we will ultimately justify the procedures which we perform and justify the reimbursement to third party payers. In this issue, we examine the concept of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and how and why to apply them to your practice.

In our lead article, Elizabeth Matzkin and colleagues present a guideline for implementing PROMs in your practice. Patrick Smith and Corey Cook provide a review of available electronic databases, and Patrick Denard and colleagues present data obtained through an electronic PROM database to settle the question “Is knotless labral repair better than conventional anchors in the shoulder?” Alan Hirahara and colleagues present their 2-year data on superior capsular Reconstruction, and Roland Biedert and Philippe Tscholl discuss the management of patella alta.

By now you’ve realized you’re holding the last printed issue of AJO. Enjoy a moment of nostalgia for the old days, and then buckle your seatbelt. We’re taking AJO where no other journal has gone before and it’s going to be one heck of a ride.

On a recent visit to my daughter’s school, I caught sight of a set of encyclopedias on the shelf. It brought me back to the days where I would open my own set to find out the information I needed to write reports for school. But my sense of nostalgia was short lived as I thought about all of the limitations of the format. If it wasn’t in the encyclopedias, I couldn’t write the report and would need to head to the library. The Internet changed all of that. Now, when I want to know something I don’t look it up in a book anymore. I ask Siri or Alexa or head to the Google home page. When one of my kids asks me a question I can’t answer, like how a tornado forms, I take out my phone and search for the answer on the Internet.

When it comes to medical information, I can’t remember the last time I opened up a journal sitting on my shelf and leafed through the contents to identify the article I needed. I simply go online and search PubMed or download the article from the AJO website. My office is no longer filled with volumes of journals, and I need only my phone to research whatever topic I’m interested in.

The way I prefer to prepare for cases has changed as well. In the past I would simply open a book or technique article and read about the best way to perform the case. Now, I prefer to watch a video or download the technique guide. I find it easier and faster than reading a book chapter or article.

When we began to change the format of the journal, we stated that AJO would be filled with practical information that would be directly impactful to your practice. That’s the number one criteria we utilize when evaluating content. We wanted to make AJO the journal you wanted to read, because it would improve your knowledge, your outcomes, and your bottom line. We have made many changes to AJO in the last 2 years of print issues. But to truly provide the experience our readers demand and deserve, we have to take a huge next step. Right now we are limited by page and word counts, printed media, and advertising pages. We receive hundreds of submissions a month, yet can only print a fraction of the great material we receive.

If you’ve been following the journal for the last 24 months, you’ve noticed that we have been testing the limits of printed media. We’ve included QR codes for videos, companion PDFs, patient information sheets, and downloadable reports to incorporate into your practice.

The way we access the journal is also changing. We’ve looked closely at our web statistics since the redesign. Our website visits have gone up by a factor of 6 with nearly half of our website traffic coming from mobile usage. It became clear that the days of the printed journal are slowly coming to an end. Surgeons don’t have time to read the journal cover to cover, and now most of our traffic comes from our eBlasts. Surgeons find an article that catches their eye and click a link to find out more. We’ve dramatically increased our eBlasts, and our website volume has been increasing exponentially.

While these small steps have been met with great success, it’s now time to make a giant leap. But unlike most journals, where the online version is just an electronic copy of the printed book, we wanted to make the new AJO something vastly different. We wanted to change the way surgeons utilized a journal and interacted with it on a daily basis. We wanted to be the electronic companion to your practice; a trusted, media rich, peer-reviewed source where you and your patients can turn to for the practical day-to-day information you can use to improve your practice.

We’ve built it, and now I’m proud to unveil it. Beginning January 1, AJO will be published exclusively online. All articles will still be PubMed cited, but will contain more photos, videos, handouts and all the information you need to replicate the findings or procedures in your practice. For example, new surgical techniques will be published with the presenting surgeon’s preference cards, rehab protocols, surgical video, and a PowerPoint presentation that can be presented to referral sources or prospective patients.

New features on our web portal will include:

An orthopedic product guide: A database organized by pathology which contains all of the relevant orthopedic products that could be used for treatment. Relevant products will be cross-referenced to articles so you can quickly identify and order equipment for new cases.

Smart article selection: You can filter the articles that match your interests and have them delivered directly to your inbox. For example, foot and ankle surgeons will no longer need to sift through hundreds of pages to find articles relevant to their practice.

A coding and billing section: Discuss and share tips and tricks with your peers and ask questions of the experts. Regular articles will present relevant codes and how to use them appropriately to get the reimbursement you deserve for your services.

Practice management and business strategies: Get advice from, and interact with, the experts in all areas of your practice.

Ask the experts: Present your cases to our editorial board and enjoy a written, peer-reviewed response. Discuss cases and mutual challenges in communities organized by subspecialty and sport. Cover a high school football team? Imagine a place where you can present your football-related injury to the world’s best football doctors and have them review and comment on the case.

These are just some of the changes you will see in the coming months. We will continuously work to improve and welcome your future suggestions as to how we can provide a truly valuable, customized journal.

Looking to the future, it is my opinion that patient-reported outcome scores will be a large part of what we do. By presenting our successful outcomes, we will ultimately justify the procedures which we perform and justify the reimbursement to third party payers. In this issue, we examine the concept of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and how and why to apply them to your practice.

In our lead article, Elizabeth Matzkin and colleagues present a guideline for implementing PROMs in your practice. Patrick Smith and Corey Cook provide a review of available electronic databases, and Patrick Denard and colleagues present data obtained through an electronic PROM database to settle the question “Is knotless labral repair better than conventional anchors in the shoulder?” Alan Hirahara and colleagues present their 2-year data on superior capsular Reconstruction, and Roland Biedert and Philippe Tscholl discuss the management of patella alta.

By now you’ve realized you’re holding the last printed issue of AJO. Enjoy a moment of nostalgia for the old days, and then buckle your seatbelt. We’re taking AJO where no other journal has gone before and it’s going to be one heck of a ride.

On a recent visit to my daughter’s school, I caught sight of a set of encyclopedias on the shelf. It brought me back to the days where I would open my own set to find out the information I needed to write reports for school. But my sense of nostalgia was short lived as I thought about all of the limitations of the format. If it wasn’t in the encyclopedias, I couldn’t write the report and would need to head to the library. The Internet changed all of that. Now, when I want to know something I don’t look it up in a book anymore. I ask Siri or Alexa or head to the Google home page. When one of my kids asks me a question I can’t answer, like how a tornado forms, I take out my phone and search for the answer on the Internet.

When it comes to medical information, I can’t remember the last time I opened up a journal sitting on my shelf and leafed through the contents to identify the article I needed. I simply go online and search PubMed or download the article from the AJO website. My office is no longer filled with volumes of journals, and I need only my phone to research whatever topic I’m interested in.

The way I prefer to prepare for cases has changed as well. In the past I would simply open a book or technique article and read about the best way to perform the case. Now, I prefer to watch a video or download the technique guide. I find it easier and faster than reading a book chapter or article.

When we began to change the format of the journal, we stated that AJO would be filled with practical information that would be directly impactful to your practice. That’s the number one criteria we utilize when evaluating content. We wanted to make AJO the journal you wanted to read, because it would improve your knowledge, your outcomes, and your bottom line. We have made many changes to AJO in the last 2 years of print issues. But to truly provide the experience our readers demand and deserve, we have to take a huge next step. Right now we are limited by page and word counts, printed media, and advertising pages. We receive hundreds of submissions a month, yet can only print a fraction of the great material we receive.

If you’ve been following the journal for the last 24 months, you’ve noticed that we have been testing the limits of printed media. We’ve included QR codes for videos, companion PDFs, patient information sheets, and downloadable reports to incorporate into your practice.

The way we access the journal is also changing. We’ve looked closely at our web statistics since the redesign. Our website visits have gone up by a factor of 6 with nearly half of our website traffic coming from mobile usage. It became clear that the days of the printed journal are slowly coming to an end. Surgeons don’t have time to read the journal cover to cover, and now most of our traffic comes from our eBlasts. Surgeons find an article that catches their eye and click a link to find out more. We’ve dramatically increased our eBlasts, and our website volume has been increasing exponentially.

While these small steps have been met with great success, it’s now time to make a giant leap. But unlike most journals, where the online version is just an electronic copy of the printed book, we wanted to make the new AJO something vastly different. We wanted to change the way surgeons utilized a journal and interacted with it on a daily basis. We wanted to be the electronic companion to your practice; a trusted, media rich, peer-reviewed source where you and your patients can turn to for the practical day-to-day information you can use to improve your practice.

We’ve built it, and now I’m proud to unveil it. Beginning January 1, AJO will be published exclusively online. All articles will still be PubMed cited, but will contain more photos, videos, handouts and all the information you need to replicate the findings or procedures in your practice. For example, new surgical techniques will be published with the presenting surgeon’s preference cards, rehab protocols, surgical video, and a PowerPoint presentation that can be presented to referral sources or prospective patients.

New features on our web portal will include:

An orthopedic product guide: A database organized by pathology which contains all of the relevant orthopedic products that could be used for treatment. Relevant products will be cross-referenced to articles so you can quickly identify and order equipment for new cases.

Smart article selection: You can filter the articles that match your interests and have them delivered directly to your inbox. For example, foot and ankle surgeons will no longer need to sift through hundreds of pages to find articles relevant to their practice.

A coding and billing section: Discuss and share tips and tricks with your peers and ask questions of the experts. Regular articles will present relevant codes and how to use them appropriately to get the reimbursement you deserve for your services.

Practice management and business strategies: Get advice from, and interact with, the experts in all areas of your practice.

Ask the experts: Present your cases to our editorial board and enjoy a written, peer-reviewed response. Discuss cases and mutual challenges in communities organized by subspecialty and sport. Cover a high school football team? Imagine a place where you can present your football-related injury to the world’s best football doctors and have them review and comment on the case.

These are just some of the changes you will see in the coming months. We will continuously work to improve and welcome your future suggestions as to how we can provide a truly valuable, customized journal.

Looking to the future, it is my opinion that patient-reported outcome scores will be a large part of what we do. By presenting our successful outcomes, we will ultimately justify the procedures which we perform and justify the reimbursement to third party payers. In this issue, we examine the concept of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and how and why to apply them to your practice.

In our lead article, Elizabeth Matzkin and colleagues present a guideline for implementing PROMs in your practice. Patrick Smith and Corey Cook provide a review of available electronic databases, and Patrick Denard and colleagues present data obtained through an electronic PROM database to settle the question “Is knotless labral repair better than conventional anchors in the shoulder?” Alan Hirahara and colleagues present their 2-year data on superior capsular Reconstruction, and Roland Biedert and Philippe Tscholl discuss the management of patella alta.

By now you’ve realized you’re holding the last printed issue of AJO. Enjoy a moment of nostalgia for the old days, and then buckle your seatbelt. We’re taking AJO where no other journal has gone before and it’s going to be one heck of a ride.

3 Approaches to PMS

Throughout my 40 years in private psychiatric practice, I have found some treatments for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that were not mentioned in “Etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces” (Evidence-Based Reviews, Current Psychiatry. September 2017, p. 20-28).

This started in 1972 when I was serving in the Army in Oklahoma. A 28-year-old woman with severe PMS had been treated by internal medicine, an OB/GYN, and endocrinology, all to no avail. Three days before her menses began, she would start driving north. When menses commenced, she would find herself in Nebraska and have to call her husband so he could wire her money to come back.

Through my evaluation, I found that she would gain 10 lb before her menses. I prescribed a diuretic and instructed her to start taking it when she began swelling and to stop taking it after her menses began. This alleviated all of her symptoms. If a woman gains more than 3 to 5 lb, her brain also will swell, along with everything else. Because the brain is encapsulated in the skull, the swelling puts pressure on the brain, which might have been the cause of these brief psychotic episodes.

If a woman who develops PMS does not experience significant weight gain, the first thing I try is vitamin B6, 100 mg/d, prior to menses. Vitamin B6 is a cofactor in the production of numerous neurotransmitters. I found that prescribing vitamin B6 would alleviate about 20% of PMS symptoms. If the patient has a personal or family history of affective disorder, I often try antidepressants prior to menses, which alleviate approximately another 20% of her symptoms. If none of the previous 3 factors are present, I often add a low dose of progesterone, which appears to help. If all else fails, I will try a low dose of lithium, 300 mg/d, before menses. This also seems to have some positive effect.

I have not written an article about these approaches to PMS, although I have discussed them with OB/GYNs, who never seem to follow these recommendations. Because I am not university-based, I have not been able to put thes

Throughout my 40 years in private psychiatric practice, I have found some treatments for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that were not mentioned in “Etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces” (Evidence-Based Reviews, Current Psychiatry. September 2017, p. 20-28).

This started in 1972 when I was serving in the Army in Oklahoma. A 28-year-old woman with severe PMS had been treated by internal medicine, an OB/GYN, and endocrinology, all to no avail. Three days before her menses began, she would start driving north. When menses commenced, she would find herself in Nebraska and have to call her husband so he could wire her money to come back.

Through my evaluation, I found that she would gain 10 lb before her menses. I prescribed a diuretic and instructed her to start taking it when she began swelling and to stop taking it after her menses began. This alleviated all of her symptoms. If a woman gains more than 3 to 5 lb, her brain also will swell, along with everything else. Because the brain is encapsulated in the skull, the swelling puts pressure on the brain, which might have been the cause of these brief psychotic episodes.

If a woman who develops PMS does not experience significant weight gain, the first thing I try is vitamin B6, 100 mg/d, prior to menses. Vitamin B6 is a cofactor in the production of numerous neurotransmitters. I found that prescribing vitamin B6 would alleviate about 20% of PMS symptoms. If the patient has a personal or family history of affective disorder, I often try antidepressants prior to menses, which alleviate approximately another 20% of her symptoms. If none of the previous 3 factors are present, I often add a low dose of progesterone, which appears to help. If all else fails, I will try a low dose of lithium, 300 mg/d, before menses. This also seems to have some positive effect.

I have not written an article about these approaches to PMS, although I have discussed them with OB/GYNs, who never seem to follow these recommendations. Because I am not university-based, I have not been able to put thes

Throughout my 40 years in private psychiatric practice, I have found some treatments for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that were not mentioned in “Etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces” (Evidence-Based Reviews, Current Psychiatry. September 2017, p. 20-28).

This started in 1972 when I was serving in the Army in Oklahoma. A 28-year-old woman with severe PMS had been treated by internal medicine, an OB/GYN, and endocrinology, all to no avail. Three days before her menses began, she would start driving north. When menses commenced, she would find herself in Nebraska and have to call her husband so he could wire her money to come back.

Through my evaluation, I found that she would gain 10 lb before her menses. I prescribed a diuretic and instructed her to start taking it when she began swelling and to stop taking it after her menses began. This alleviated all of her symptoms. If a woman gains more than 3 to 5 lb, her brain also will swell, along with everything else. Because the brain is encapsulated in the skull, the swelling puts pressure on the brain, which might have been the cause of these brief psychotic episodes.

If a woman who develops PMS does not experience significant weight gain, the first thing I try is vitamin B6, 100 mg/d, prior to menses. Vitamin B6 is a cofactor in the production of numerous neurotransmitters. I found that prescribing vitamin B6 would alleviate about 20% of PMS symptoms. If the patient has a personal or family history of affective disorder, I often try antidepressants prior to menses, which alleviate approximately another 20% of her symptoms. If none of the previous 3 factors are present, I often add a low dose of progesterone, which appears to help. If all else fails, I will try a low dose of lithium, 300 mg/d, before menses. This also seems to have some positive effect.

I have not written an article about these approaches to PMS, although I have discussed them with OB/GYNs, who never seem to follow these recommendations. Because I am not university-based, I have not been able to put thes

A tribute to David Warfield Stires, JFP’s founding publisher

The recent passing of the founding publisher of The Journal of Family Practice, David Warfield Stires, is an occasion to honor and celebrate his support of, and dedication to, the specialty of family medicine.

David and I began working together in 1970. That was one year after family medicine was recognized as the 20th medical specialty in the United States. It was also a year after I left my solo rural family practice in Mount Shasta, Calif. to convert the general practice residency at Sonoma County Hospital, Santa Rosa, to a 3-year family practice residency affiliated with the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

In 1970, I’d just completed my first book manuscript, “The Modern Family Doctor and Changing Medical Practice,” and I went searching for a publisher for it. After 2 rejections, I approached David, who was the president of Appleton-Century-Crofts, the second largest medical publisher in the country. He grew up in a small town near Canton, Ohio, and his father had been a general practitioner and a real country doctor. David immediately saw the value of my book, and our lifelong friendship began.

There was no academic journal in the field of family medicine at that time. The only thing that came close was the American Academy of Family Physicians’ journal for summary CME articles, American Family Physician. As we got to talking, David saw the need to expand the field’s literature base to articulate its academic discipline and report original research. We soon held an organizational meeting of a new editorial board in San Francisco. And in 1974, The Journal of Family Practice was “born” with Appleton-Century-Crofts as its publisher.

Because we had very little startup funding, we depended on advertising to enable us to send the journal to all general and family physicians in the United States. In those early years, advertising income was sufficient to maintain the journal. But with increasing pressure to bring in more and more ad dollars, JFP was bought and sold over the next 16 years. And in 1990, I left as editor and began my stint as editor of the Journal of the American Board of Family Practice (now Family Medicine).

After more than 30 years in publishing, David and his wife, Wendy, moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he pursued his lifelong interest in photography, and where his work was regularly shown in galleries. He and I saw each other frequently over the years, often visiting in the Pacific Northwest. Beyond the many books that he published, he was most proud of creating JFP.

Today, 43 years later, David’s legacy lives on in a vibrant journal and medical specialty. Thank you, David, for your lifelong support of family medicine and for your friendship.

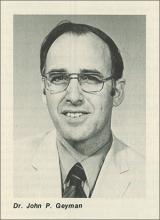

John Geyman, MD

Friday Harbor, Wash.

Editor’s response

Dr. John Geyman’s tribute to The Journal of Family Practice’s founding publisher, David Warfield Stires, provides me with the opportunity to do 2 things.

First, to thank John for his visionary leadership in founding and guiding the successful development of the first research journal for family medicine in the United States. (In 1970, family medicine was called “family practice,” hence our name The Journal of Family Practice—a name we have maintained over the years because of its “recognition factor.”) Much of the original US family medicine research of the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s was published in JFP. I still remember the thrill of having my first research study published in JFP in 1983.1

Second, I want to remind our readers that although our focus has changed to mostly evidence-based clinical reviews, we remain firmly rooted in practical research that informs the everyday practice of family medicine and primary care. We still publish (albeit a limited number) of original research studies that have high practical value to primary care, such as a recent article on the use of medical scribes.2 This is largely due to the foresight and vision of pioneers in this field like David Warfield Stires and Dr. John Geyman.

John Hickner, MD, MSc

1. Messimer S, Hickner J. Oral fluoride supplementation: improving practitioner compliance by using a protocol. J Fam Pract. 1983;17:821-825.

2. Earls ST, Savageau JA, Begley S, et al. Can scribes boost FPs’ efficiency and job satisfaction? J Fam Pract. 2017;66:206-214.

The recent passing of the founding publisher of The Journal of Family Practice, David Warfield Stires, is an occasion to honor and celebrate his support of, and dedication to, the specialty of family medicine.

David and I began working together in 1970. That was one year after family medicine was recognized as the 20th medical specialty in the United States. It was also a year after I left my solo rural family practice in Mount Shasta, Calif. to convert the general practice residency at Sonoma County Hospital, Santa Rosa, to a 3-year family practice residency affiliated with the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

In 1970, I’d just completed my first book manuscript, “The Modern Family Doctor and Changing Medical Practice,” and I went searching for a publisher for it. After 2 rejections, I approached David, who was the president of Appleton-Century-Crofts, the second largest medical publisher in the country. He grew up in a small town near Canton, Ohio, and his father had been a general practitioner and a real country doctor. David immediately saw the value of my book, and our lifelong friendship began.

There was no academic journal in the field of family medicine at that time. The only thing that came close was the American Academy of Family Physicians’ journal for summary CME articles, American Family Physician. As we got to talking, David saw the need to expand the field’s literature base to articulate its academic discipline and report original research. We soon held an organizational meeting of a new editorial board in San Francisco. And in 1974, The Journal of Family Practice was “born” with Appleton-Century-Crofts as its publisher.

Because we had very little startup funding, we depended on advertising to enable us to send the journal to all general and family physicians in the United States. In those early years, advertising income was sufficient to maintain the journal. But with increasing pressure to bring in more and more ad dollars, JFP was bought and sold over the next 16 years. And in 1990, I left as editor and began my stint as editor of the Journal of the American Board of Family Practice (now Family Medicine).

After more than 30 years in publishing, David and his wife, Wendy, moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he pursued his lifelong interest in photography, and where his work was regularly shown in galleries. He and I saw each other frequently over the years, often visiting in the Pacific Northwest. Beyond the many books that he published, he was most proud of creating JFP.

Today, 43 years later, David’s legacy lives on in a vibrant journal and medical specialty. Thank you, David, for your lifelong support of family medicine and for your friendship.

John Geyman, MD

Friday Harbor, Wash.

Editor’s response

Dr. John Geyman’s tribute to The Journal of Family Practice’s founding publisher, David Warfield Stires, provides me with the opportunity to do 2 things.

First, to thank John for his visionary leadership in founding and guiding the successful development of the first research journal for family medicine in the United States. (In 1970, family medicine was called “family practice,” hence our name The Journal of Family Practice—a name we have maintained over the years because of its “recognition factor.”) Much of the original US family medicine research of the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s was published in JFP. I still remember the thrill of having my first research study published in JFP in 1983.1

Second, I want to remind our readers that although our focus has changed to mostly evidence-based clinical reviews, we remain firmly rooted in practical research that informs the everyday practice of family medicine and primary care. We still publish (albeit a limited number) of original research studies that have high practical value to primary care, such as a recent article on the use of medical scribes.2 This is largely due to the foresight and vision of pioneers in this field like David Warfield Stires and Dr. John Geyman.

John Hickner, MD, MSc

The recent passing of the founding publisher of The Journal of Family Practice, David Warfield Stires, is an occasion to honor and celebrate his support of, and dedication to, the specialty of family medicine.

David and I began working together in 1970. That was one year after family medicine was recognized as the 20th medical specialty in the United States. It was also a year after I left my solo rural family practice in Mount Shasta, Calif. to convert the general practice residency at Sonoma County Hospital, Santa Rosa, to a 3-year family practice residency affiliated with the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

In 1970, I’d just completed my first book manuscript, “The Modern Family Doctor and Changing Medical Practice,” and I went searching for a publisher for it. After 2 rejections, I approached David, who was the president of Appleton-Century-Crofts, the second largest medical publisher in the country. He grew up in a small town near Canton, Ohio, and his father had been a general practitioner and a real country doctor. David immediately saw the value of my book, and our lifelong friendship began.

There was no academic journal in the field of family medicine at that time. The only thing that came close was the American Academy of Family Physicians’ journal for summary CME articles, American Family Physician. As we got to talking, David saw the need to expand the field’s literature base to articulate its academic discipline and report original research. We soon held an organizational meeting of a new editorial board in San Francisco. And in 1974, The Journal of Family Practice was “born” with Appleton-Century-Crofts as its publisher.

Because we had very little startup funding, we depended on advertising to enable us to send the journal to all general and family physicians in the United States. In those early years, advertising income was sufficient to maintain the journal. But with increasing pressure to bring in more and more ad dollars, JFP was bought and sold over the next 16 years. And in 1990, I left as editor and began my stint as editor of the Journal of the American Board of Family Practice (now Family Medicine).

After more than 30 years in publishing, David and his wife, Wendy, moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he pursued his lifelong interest in photography, and where his work was regularly shown in galleries. He and I saw each other frequently over the years, often visiting in the Pacific Northwest. Beyond the many books that he published, he was most proud of creating JFP.

Today, 43 years later, David’s legacy lives on in a vibrant journal and medical specialty. Thank you, David, for your lifelong support of family medicine and for your friendship.

John Geyman, MD

Friday Harbor, Wash.

Editor’s response

Dr. John Geyman’s tribute to The Journal of Family Practice’s founding publisher, David Warfield Stires, provides me with the opportunity to do 2 things.

First, to thank John for his visionary leadership in founding and guiding the successful development of the first research journal for family medicine in the United States. (In 1970, family medicine was called “family practice,” hence our name The Journal of Family Practice—a name we have maintained over the years because of its “recognition factor.”) Much of the original US family medicine research of the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s was published in JFP. I still remember the thrill of having my first research study published in JFP in 1983.1

Second, I want to remind our readers that although our focus has changed to mostly evidence-based clinical reviews, we remain firmly rooted in practical research that informs the everyday practice of family medicine and primary care. We still publish (albeit a limited number) of original research studies that have high practical value to primary care, such as a recent article on the use of medical scribes.2 This is largely due to the foresight and vision of pioneers in this field like David Warfield Stires and Dr. John Geyman.

John Hickner, MD, MSc

1. Messimer S, Hickner J. Oral fluoride supplementation: improving practitioner compliance by using a protocol. J Fam Pract. 1983;17:821-825.

2. Earls ST, Savageau JA, Begley S, et al. Can scribes boost FPs’ efficiency and job satisfaction? J Fam Pract. 2017;66:206-214.

1. Messimer S, Hickner J. Oral fluoride supplementation: improving practitioner compliance by using a protocol. J Fam Pract. 1983;17:821-825.

2. Earls ST, Savageau JA, Begley S, et al. Can scribes boost FPs’ efficiency and job satisfaction? J Fam Pract. 2017;66:206-214.

Vaping marijuana?

Cannavaping—the inhalation of a cannabis-containing aerosol, created by a battery-driven, heated atomizer in e-cigarettes or similar devices1—is touted as a less expensive and safer alternative to smoking marijuana. It’s also gaining in popularity.2 One study of Connecticut high school students found that 5.4% had used e-cigarettes to vaporize cannabis.3 But what do we know about this new way to get high?

We know that those who wish to cannavape can easily obtain e-cigarettes from gas stations and tobacco shops. They then have to obtain a cartridge, filled with either hash oil or tetrahydrocannabinol-infused wax, to attach to the e-cigarette. These cartridges are available for purchase in states that have legalized the sale of marijuana. They also find their way into states where the sale of marijuana is not legal, and are purchased illegally for the purpose of cannavaping.

And while cannavaping does appear to reduce the cost of smoking marijuana,4 it has not been widely researched, nor determined to be safe.5

In fact, although marijuana has several important therapeutic and medicinal purposes, cannavaping the substance can result in medical concerns.6 The vaping aerosols of some compounds can induce lung pathology and may be carcinogenic, since they often contain a number of dangerous toxins.4

Chronic marijuana use can increase the likelihood of motor vehicles accidents, cognitive impairment, psychoses, and demotivation.4 It may predispose certain individuals to use other drugs and tobacco products and could increase the consumption of marijuana.4,5 Increased consumption could have a detrimental effect on intellect and behavior when used chronically—especially in youngsters, whose nervous systems are not yet fully matured.7-9

Because cannavaping has potentially deleterious effects, more regulations on the manufacture, distribution, access, and use are indicated—at least until research sheds more light on issues surrounding this practice.

Steven Lippman, MD; Devina Singh, MD

Louisville, KY

1. Varlet V, Concha-Lozano N, Berthlet A, et al. Drug vaping applied to cannabis: is “cannavaping” a therapeutic alternative to marijuana? Sci Rep. 2016;6:25599.

2. Giroud C, de Cesare M, Berthet A, et al. E-cigarettes: a review of new trends in cannabis use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:9988-10008.

3. Morean ME, Kong G, Camenga DR, et al. High school students’ use of electronic cigarettes to vaporize cannabis. Pediatrics. 2015;136:611-616.

4. Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction. 2015;110:1699-1704.

5. Cox B. Can the research community respond adequately to the health risks of vaping? Addiction. 2015;110:1709-1709.

6. Rong C, Lee Y, Carmona NE, et al. Cannabidiol in medical marijuana: research vistas and potential opportunities. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:213-218.

7. Schweinsburg AD, Brown SA, Tapert SF. The influence of marijuana use on neurocognitive functioning in adolescents. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:99-111.

8. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2657-2664.

9. Castellanos-Ryan N, Pingault J, Parent S, et al. Adolescent cannabis use, change in neurocognitive function, and high-school graduation: a longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol . 2017;29:1253-1266.

Cannavaping—the inhalation of a cannabis-containing aerosol, created by a battery-driven, heated atomizer in e-cigarettes or similar devices1—is touted as a less expensive and safer alternative to smoking marijuana. It’s also gaining in popularity.2 One study of Connecticut high school students found that 5.4% had used e-cigarettes to vaporize cannabis.3 But what do we know about this new way to get high?

We know that those who wish to cannavape can easily obtain e-cigarettes from gas stations and tobacco shops. They then have to obtain a cartridge, filled with either hash oil or tetrahydrocannabinol-infused wax, to attach to the e-cigarette. These cartridges are available for purchase in states that have legalized the sale of marijuana. They also find their way into states where the sale of marijuana is not legal, and are purchased illegally for the purpose of cannavaping.

And while cannavaping does appear to reduce the cost of smoking marijuana,4 it has not been widely researched, nor determined to be safe.5

In fact, although marijuana has several important therapeutic and medicinal purposes, cannavaping the substance can result in medical concerns.6 The vaping aerosols of some compounds can induce lung pathology and may be carcinogenic, since they often contain a number of dangerous toxins.4

Chronic marijuana use can increase the likelihood of motor vehicles accidents, cognitive impairment, psychoses, and demotivation.4 It may predispose certain individuals to use other drugs and tobacco products and could increase the consumption of marijuana.4,5 Increased consumption could have a detrimental effect on intellect and behavior when used chronically—especially in youngsters, whose nervous systems are not yet fully matured.7-9

Because cannavaping has potentially deleterious effects, more regulations on the manufacture, distribution, access, and use are indicated—at least until research sheds more light on issues surrounding this practice.

Steven Lippman, MD; Devina Singh, MD

Louisville, KY

Cannavaping—the inhalation of a cannabis-containing aerosol, created by a battery-driven, heated atomizer in e-cigarettes or similar devices1—is touted as a less expensive and safer alternative to smoking marijuana. It’s also gaining in popularity.2 One study of Connecticut high school students found that 5.4% had used e-cigarettes to vaporize cannabis.3 But what do we know about this new way to get high?

We know that those who wish to cannavape can easily obtain e-cigarettes from gas stations and tobacco shops. They then have to obtain a cartridge, filled with either hash oil or tetrahydrocannabinol-infused wax, to attach to the e-cigarette. These cartridges are available for purchase in states that have legalized the sale of marijuana. They also find their way into states where the sale of marijuana is not legal, and are purchased illegally for the purpose of cannavaping.

And while cannavaping does appear to reduce the cost of smoking marijuana,4 it has not been widely researched, nor determined to be safe.5

In fact, although marijuana has several important therapeutic and medicinal purposes, cannavaping the substance can result in medical concerns.6 The vaping aerosols of some compounds can induce lung pathology and may be carcinogenic, since they often contain a number of dangerous toxins.4

Chronic marijuana use can increase the likelihood of motor vehicles accidents, cognitive impairment, psychoses, and demotivation.4 It may predispose certain individuals to use other drugs and tobacco products and could increase the consumption of marijuana.4,5 Increased consumption could have a detrimental effect on intellect and behavior when used chronically—especially in youngsters, whose nervous systems are not yet fully matured.7-9

Because cannavaping has potentially deleterious effects, more regulations on the manufacture, distribution, access, and use are indicated—at least until research sheds more light on issues surrounding this practice.

Steven Lippman, MD; Devina Singh, MD

Louisville, KY

1. Varlet V, Concha-Lozano N, Berthlet A, et al. Drug vaping applied to cannabis: is “cannavaping” a therapeutic alternative to marijuana? Sci Rep. 2016;6:25599.

2. Giroud C, de Cesare M, Berthet A, et al. E-cigarettes: a review of new trends in cannabis use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:9988-10008.

3. Morean ME, Kong G, Camenga DR, et al. High school students’ use of electronic cigarettes to vaporize cannabis. Pediatrics. 2015;136:611-616.

4. Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction. 2015;110:1699-1704.

5. Cox B. Can the research community respond adequately to the health risks of vaping? Addiction. 2015;110:1709-1709.

6. Rong C, Lee Y, Carmona NE, et al. Cannabidiol in medical marijuana: research vistas and potential opportunities. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:213-218.

7. Schweinsburg AD, Brown SA, Tapert SF. The influence of marijuana use on neurocognitive functioning in adolescents. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:99-111.

8. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2657-2664.

9. Castellanos-Ryan N, Pingault J, Parent S, et al. Adolescent cannabis use, change in neurocognitive function, and high-school graduation: a longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol . 2017;29:1253-1266.

1. Varlet V, Concha-Lozano N, Berthlet A, et al. Drug vaping applied to cannabis: is “cannavaping” a therapeutic alternative to marijuana? Sci Rep. 2016;6:25599.

2. Giroud C, de Cesare M, Berthet A, et al. E-cigarettes: a review of new trends in cannabis use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:9988-10008.

3. Morean ME, Kong G, Camenga DR, et al. High school students’ use of electronic cigarettes to vaporize cannabis. Pediatrics. 2015;136:611-616.

4. Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction. 2015;110:1699-1704.

5. Cox B. Can the research community respond adequately to the health risks of vaping? Addiction. 2015;110:1709-1709.

6. Rong C, Lee Y, Carmona NE, et al. Cannabidiol in medical marijuana: research vistas and potential opportunities. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:213-218.

7. Schweinsburg AD, Brown SA, Tapert SF. The influence of marijuana use on neurocognitive functioning in adolescents. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:99-111.

8. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2657-2664.

9. Castellanos-Ryan N, Pingault J, Parent S, et al. Adolescent cannabis use, change in neurocognitive function, and high-school graduation: a longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol . 2017;29:1253-1266.

Treat gun violence like the public health crisis it is

Last month’s mass shooting in Las Vegas, which killed 59 people and wounded 500, was committed by a single individual who legally purchased an arsenal that allowed him to fire hundreds of high-caliber bullets within minutes into a large crowd. This is just the latest in a series of high-profile mass killings that appear to be increasing in frequency.1

As terrifying as mass murders are, they account for only a small fraction of gun-related mortality. Everyday about 80 people in the United States are killed by a gun, usually by someone they know or by themselves (almost two-thirds of gun-related mortality involves suicide).2 No other developed country even comes close to our rate of gun-related violence.2

What to do? Recall anti-smoking efforts. Gun violence is a public health issue that should be addressed with tried and proven public health methods. A couple of examples from history hold valuable lessons. While tobacco-related mortality and morbidity remain public health concerns, we have made marked improvements and saved many lives through a series of public health interventions including increasing the price of tobacco products, restricting advertising and sales to minors, and prohibiting smoking in public areas, to name a few.3

These interventions occurred because the public recognized the threat of tobacco and was willing to adopt them. This was not always the case. During the first half of my life, smoking in public, including indoors at public events and even on airplanes, was accepted, and the “rights of smokers” were respected. This now seems inconceivable. Public health interventions work, and public perceptions and attitudes can change.

Consider inroads made in driver safety, too. We have also made marked improvements in motor vehicle crash-related deaths and injuries.4 For decades, we have recorded hundreds of data points on every car crash resulting in a death in a comprehensive database—the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). These data have been used by researchers to identify causes of crashes and crash-related deaths and have led to improvements in car design and road safety. Additional factors leading to improved road safety include restrictions on the age at which one can drive and on drinking alcohol and driving.

We can achieve similar improvements in gun-related mortality if we establish and maintain a comprehensive database, encourage and fund research, and are willing to adopt some commonsense product improvements and ownership restrictions that, nevertheless, preserve the right for most to responsibly own a firearm.

Don’t you think it’s time?

1. Blair JP, Schweit KW. A study of active shooter incidents in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Texas State University and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice, Washington, DC. 2014. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-study-2000-2013-1.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2017.

2. Wintemute GJ. The epidemiology of firearm violence in the twenty-first century United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:5-19.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:986-993.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 motor-vehicle safety: a 20th century public health achievement. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:369-374.

Last month’s mass shooting in Las Vegas, which killed 59 people and wounded 500, was committed by a single individual who legally purchased an arsenal that allowed him to fire hundreds of high-caliber bullets within minutes into a large crowd. This is just the latest in a series of high-profile mass killings that appear to be increasing in frequency.1

As terrifying as mass murders are, they account for only a small fraction of gun-related mortality. Everyday about 80 people in the United States are killed by a gun, usually by someone they know or by themselves (almost two-thirds of gun-related mortality involves suicide).2 No other developed country even comes close to our rate of gun-related violence.2

What to do? Recall anti-smoking efforts. Gun violence is a public health issue that should be addressed with tried and proven public health methods. A couple of examples from history hold valuable lessons. While tobacco-related mortality and morbidity remain public health concerns, we have made marked improvements and saved many lives through a series of public health interventions including increasing the price of tobacco products, restricting advertising and sales to minors, and prohibiting smoking in public areas, to name a few.3

These interventions occurred because the public recognized the threat of tobacco and was willing to adopt them. This was not always the case. During the first half of my life, smoking in public, including indoors at public events and even on airplanes, was accepted, and the “rights of smokers” were respected. This now seems inconceivable. Public health interventions work, and public perceptions and attitudes can change.

Consider inroads made in driver safety, too. We have also made marked improvements in motor vehicle crash-related deaths and injuries.4 For decades, we have recorded hundreds of data points on every car crash resulting in a death in a comprehensive database—the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). These data have been used by researchers to identify causes of crashes and crash-related deaths and have led to improvements in car design and road safety. Additional factors leading to improved road safety include restrictions on the age at which one can drive and on drinking alcohol and driving.

We can achieve similar improvements in gun-related mortality if we establish and maintain a comprehensive database, encourage and fund research, and are willing to adopt some commonsense product improvements and ownership restrictions that, nevertheless, preserve the right for most to responsibly own a firearm.

Don’t you think it’s time?

Last month’s mass shooting in Las Vegas, which killed 59 people and wounded 500, was committed by a single individual who legally purchased an arsenal that allowed him to fire hundreds of high-caliber bullets within minutes into a large crowd. This is just the latest in a series of high-profile mass killings that appear to be increasing in frequency.1

As terrifying as mass murders are, they account for only a small fraction of gun-related mortality. Everyday about 80 people in the United States are killed by a gun, usually by someone they know or by themselves (almost two-thirds of gun-related mortality involves suicide).2 No other developed country even comes close to our rate of gun-related violence.2

What to do? Recall anti-smoking efforts. Gun violence is a public health issue that should be addressed with tried and proven public health methods. A couple of examples from history hold valuable lessons. While tobacco-related mortality and morbidity remain public health concerns, we have made marked improvements and saved many lives through a series of public health interventions including increasing the price of tobacco products, restricting advertising and sales to minors, and prohibiting smoking in public areas, to name a few.3

These interventions occurred because the public recognized the threat of tobacco and was willing to adopt them. This was not always the case. During the first half of my life, smoking in public, including indoors at public events and even on airplanes, was accepted, and the “rights of smokers” were respected. This now seems inconceivable. Public health interventions work, and public perceptions and attitudes can change.

Consider inroads made in driver safety, too. We have also made marked improvements in motor vehicle crash-related deaths and injuries.4 For decades, we have recorded hundreds of data points on every car crash resulting in a death in a comprehensive database—the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). These data have been used by researchers to identify causes of crashes and crash-related deaths and have led to improvements in car design and road safety. Additional factors leading to improved road safety include restrictions on the age at which one can drive and on drinking alcohol and driving.

We can achieve similar improvements in gun-related mortality if we establish and maintain a comprehensive database, encourage and fund research, and are willing to adopt some commonsense product improvements and ownership restrictions that, nevertheless, preserve the right for most to responsibly own a firearm.

Don’t you think it’s time?

1. Blair JP, Schweit KW. A study of active shooter incidents in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Texas State University and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice, Washington, DC. 2014. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-study-2000-2013-1.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2017.

2. Wintemute GJ. The epidemiology of firearm violence in the twenty-first century United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:5-19.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:986-993.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 motor-vehicle safety: a 20th century public health achievement. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:369-374.

1. Blair JP, Schweit KW. A study of active shooter incidents in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Texas State University and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice, Washington, DC. 2014. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-study-2000-2013-1.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2017.

2. Wintemute GJ. The epidemiology of firearm violence in the twenty-first century United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:5-19.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:986-993.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 motor-vehicle safety: a 20th century public health achievement. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:369-374.

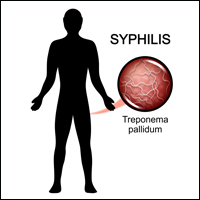

Syphilis and the Dermatologist

Once upon a time, and long ago, dermatology journals included “syphilology” in their names. The first dermatologic journal published in the United States was the American Journal of Syphilology and Dermatology.1 In October 1882 the Journal of Cutaneous and Venereal Diseases appeared and subsequently renamed several times from 1882 to 1919: Journal of Cutaneous Diseases and Genitourinary Diseases and the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases, Including Syphilis. When the American Medical Association (AMA) assumed control, this publication obtained a new name: Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology; in January 1955 syphilology was deleted from the title. According to an editorial in that issue, the rationale for dropping the word syphilology was as follows: “The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. . . . Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, ‘Syphilology,’ on this publication seems no longer warranted.”1 Needless to say, this decision ignored the obvious fact that the majority of dermatologists traditionally were well trained in and clinically practiced venereology, particularly the management of syphilis,2,3 which makes sense, considering that many of the clinical manifestations of syphilis involve the skin, hair, and oral mucosa. My own mentor and former Baylor College of Medicine dermatology department chair, Dr. John Knox, authored 3 dozen major publications regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and immunology of syphilis. During his chairmanship, all residents were required to rotate in the Harris County sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic on a weekly basis.

I am confident that the decision to drop “syphilology” from the journal title also was based on the unduly optimistic assumption that syphilis would soon become a rare disease due to the availability of penicillin. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has periodically announced strategic programs designed to eradicate syphilis!4 This rosy outlook reached a fever pitch in 2000 when the number of cases (5979) and the incidence (2.1 cases per 100,000 population) of primary and secondary syphilis reached an all-time low in the United States.5

Unfortunately, no one could accurately predict the future. Although the number of cases and incidence of early infectious syphilis have fluctuated widely since the 1940s, we currently are in a dire period of syphilis resurgence; the largest number of cases (27,814) and the highest incidence rate of primary and secondary syphilis (8.7 cases per 100,000 population) since 1994 were reported in 2016,6 which illustrates the inability of public health initiatives to eliminate syphilis, largely due to the inability of health authorities, health care providers, teachers, parents, clergy, and peer groups to alter sexual behaviors or modify other socioeconomic factors.7 Thus, syphilis lives on! Nobody could have predicted the easy availability of oral contraceptives and the ensuing sexual revolution of the 1960s or the advent of erectile dysfunction drugs decades later that led to increasing STDs among older patients.8 Nobody could have predicted the wholesale acceptance of casual sexual intercourse as popularized on television and in the movies or the pervasive use of sexual images in advertising. Nobody could have predicted the modern phenomena of “booty-call relationships,” “friends with benefits,” and “sexting,” or the nearly ubiquitous and increasingly legal use of noninjectable mind-altering drugs, all of which facilitate the perpetuation of STDs.9-11 Finally, those who removed “syphilology” from that journal title certainly did not foresee the worldwide epidemic now known as human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, which has most assuredly helped keep syphilis a modern day menace.12-14

How have dermatologists been impacted? Our journals and our teachers have deemphasized STDs, including syphilis, in modern times, yet we are faced with a disease carrying serious, if not often fatal, consequences that is simply refusing to disappear (contrary to wishful thinking). Dermatologists are, however, in a perfect epidemiological position to help in the war against Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. We frequently see adolescent patients for warts and acne, and we often diagnose and help care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus. We obliterate actinic keratoses and perform cosmetic procedures on those who rely on erectile dysfunction drugs (or their partners do). Who better than a dermatologist to recognize in these high-risk constituencies, and others, that patchy hair loss may represent syphilitic alopecia and that extragenital chancres can mimic nonmelanoma skin cancer? Who better than the dermatologist to distinguish between oral mucous patches and orolabial herpes? Who better than the dermatologist to diagnose the annular syphilid of the face, or ostraceous, florid nodular, or ulceronecrotic lesions of lues maligna? Who better than the dermatologist to differentiate condylomata lata from external genital warts?

I would suggest that the responsible dermatologist become reacquainted with syphilis, in all its various manifestations. I would further suggest that our dermatology training centers spend more time diligently teaching residents about syphilis and other STDs. In conclusion, I fervently hope that organized dermatology will once again dutifully consider venereal disease to be a critical part of our specialty’s skill set.

- Editorial. AMA Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:1.

- Shelley WB. Major contributors to American dermatology—1876 to 1926. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1642-1646.

- Lobitz WC Jr. Major contributions of American dermatologists—1926 to 1976. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1646-1650.

- Hook EW 3rd. Elimination of syphilis transmission in the United States: historic perspectives and practical considerations. Trans Am ClinClimatol Assoc. 1999;110:195-203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2000. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 2016 Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance: syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/syphilis.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 20, 2017.

- Shockman S, Buescher LS, Stone SP. Syphilis in the United States. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:213-218.

- Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

- Jonason PK, Li NP, Richardson J. Positioning the booty-call relationship on the spectrum of relationships: sexual but more emotional than one-night stands. J Sex Res. 2011;48:486-495.

- Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134:E1287-E1292.

- Regan R, Dyer TP, Gooding T, et al. Associations between drug use and sexual risks among heterosexual men in the Philippines [published online July 22, 2013]. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:969-976.

- Flagg EW, Weinstock HS, Frazier EL, et al. Bacterial sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected patients in the United States: estimates from the Medical Monitoring Project. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:171-179.

- Shilaih M, Marzel A, Braun DL, et al; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Factors associated with syphilis incidence in the HIV-infected in the era of highly active antiretrovirals. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E5849.

- Salado-Rasmussen K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. epidemiology, treatment and molecular typing of Treponema pallidum. Dan Med J. 2015;62:B5176.

Once upon a time, and long ago, dermatology journals included “syphilology” in their names. The first dermatologic journal published in the United States was the American Journal of Syphilology and Dermatology.1 In October 1882 the Journal of Cutaneous and Venereal Diseases appeared and subsequently renamed several times from 1882 to 1919: Journal of Cutaneous Diseases and Genitourinary Diseases and the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases, Including Syphilis. When the American Medical Association (AMA) assumed control, this publication obtained a new name: Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology; in January 1955 syphilology was deleted from the title. According to an editorial in that issue, the rationale for dropping the word syphilology was as follows: “The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. . . . Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, ‘Syphilology,’ on this publication seems no longer warranted.”1 Needless to say, this decision ignored the obvious fact that the majority of dermatologists traditionally were well trained in and clinically practiced venereology, particularly the management of syphilis,2,3 which makes sense, considering that many of the clinical manifestations of syphilis involve the skin, hair, and oral mucosa. My own mentor and former Baylor College of Medicine dermatology department chair, Dr. John Knox, authored 3 dozen major publications regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and immunology of syphilis. During his chairmanship, all residents were required to rotate in the Harris County sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic on a weekly basis.

I am confident that the decision to drop “syphilology” from the journal title also was based on the unduly optimistic assumption that syphilis would soon become a rare disease due to the availability of penicillin. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has periodically announced strategic programs designed to eradicate syphilis!4 This rosy outlook reached a fever pitch in 2000 when the number of cases (5979) and the incidence (2.1 cases per 100,000 population) of primary and secondary syphilis reached an all-time low in the United States.5

Unfortunately, no one could accurately predict the future. Although the number of cases and incidence of early infectious syphilis have fluctuated widely since the 1940s, we currently are in a dire period of syphilis resurgence; the largest number of cases (27,814) and the highest incidence rate of primary and secondary syphilis (8.7 cases per 100,000 population) since 1994 were reported in 2016,6 which illustrates the inability of public health initiatives to eliminate syphilis, largely due to the inability of health authorities, health care providers, teachers, parents, clergy, and peer groups to alter sexual behaviors or modify other socioeconomic factors.7 Thus, syphilis lives on! Nobody could have predicted the easy availability of oral contraceptives and the ensuing sexual revolution of the 1960s or the advent of erectile dysfunction drugs decades later that led to increasing STDs among older patients.8 Nobody could have predicted the wholesale acceptance of casual sexual intercourse as popularized on television and in the movies or the pervasive use of sexual images in advertising. Nobody could have predicted the modern phenomena of “booty-call relationships,” “friends with benefits,” and “sexting,” or the nearly ubiquitous and increasingly legal use of noninjectable mind-altering drugs, all of which facilitate the perpetuation of STDs.9-11 Finally, those who removed “syphilology” from that journal title certainly did not foresee the worldwide epidemic now known as human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, which has most assuredly helped keep syphilis a modern day menace.12-14

How have dermatologists been impacted? Our journals and our teachers have deemphasized STDs, including syphilis, in modern times, yet we are faced with a disease carrying serious, if not often fatal, consequences that is simply refusing to disappear (contrary to wishful thinking). Dermatologists are, however, in a perfect epidemiological position to help in the war against Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. We frequently see adolescent patients for warts and acne, and we often diagnose and help care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus. We obliterate actinic keratoses and perform cosmetic procedures on those who rely on erectile dysfunction drugs (or their partners do). Who better than a dermatologist to recognize in these high-risk constituencies, and others, that patchy hair loss may represent syphilitic alopecia and that extragenital chancres can mimic nonmelanoma skin cancer? Who better than the dermatologist to distinguish between oral mucous patches and orolabial herpes? Who better than the dermatologist to diagnose the annular syphilid of the face, or ostraceous, florid nodular, or ulceronecrotic lesions of lues maligna? Who better than the dermatologist to differentiate condylomata lata from external genital warts?

I would suggest that the responsible dermatologist become reacquainted with syphilis, in all its various manifestations. I would further suggest that our dermatology training centers spend more time diligently teaching residents about syphilis and other STDs. In conclusion, I fervently hope that organized dermatology will once again dutifully consider venereal disease to be a critical part of our specialty’s skill set.

Once upon a time, and long ago, dermatology journals included “syphilology” in their names. The first dermatologic journal published in the United States was the American Journal of Syphilology and Dermatology.1 In October 1882 the Journal of Cutaneous and Venereal Diseases appeared and subsequently renamed several times from 1882 to 1919: Journal of Cutaneous Diseases and Genitourinary Diseases and the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases, Including Syphilis. When the American Medical Association (AMA) assumed control, this publication obtained a new name: Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology; in January 1955 syphilology was deleted from the title. According to an editorial in that issue, the rationale for dropping the word syphilology was as follows: “The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. . . . Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, ‘Syphilology,’ on this publication seems no longer warranted.”1 Needless to say, this decision ignored the obvious fact that the majority of dermatologists traditionally were well trained in and clinically practiced venereology, particularly the management of syphilis,2,3 which makes sense, considering that many of the clinical manifestations of syphilis involve the skin, hair, and oral mucosa. My own mentor and former Baylor College of Medicine dermatology department chair, Dr. John Knox, authored 3 dozen major publications regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and immunology of syphilis. During his chairmanship, all residents were required to rotate in the Harris County sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic on a weekly basis.

I am confident that the decision to drop “syphilology” from the journal title also was based on the unduly optimistic assumption that syphilis would soon become a rare disease due to the availability of penicillin. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has periodically announced strategic programs designed to eradicate syphilis!4 This rosy outlook reached a fever pitch in 2000 when the number of cases (5979) and the incidence (2.1 cases per 100,000 population) of primary and secondary syphilis reached an all-time low in the United States.5

Unfortunately, no one could accurately predict the future. Although the number of cases and incidence of early infectious syphilis have fluctuated widely since the 1940s, we currently are in a dire period of syphilis resurgence; the largest number of cases (27,814) and the highest incidence rate of primary and secondary syphilis (8.7 cases per 100,000 population) since 1994 were reported in 2016,6 which illustrates the inability of public health initiatives to eliminate syphilis, largely due to the inability of health authorities, health care providers, teachers, parents, clergy, and peer groups to alter sexual behaviors or modify other socioeconomic factors.7 Thus, syphilis lives on! Nobody could have predicted the easy availability of oral contraceptives and the ensuing sexual revolution of the 1960s or the advent of erectile dysfunction drugs decades later that led to increasing STDs among older patients.8 Nobody could have predicted the wholesale acceptance of casual sexual intercourse as popularized on television and in the movies or the pervasive use of sexual images in advertising. Nobody could have predicted the modern phenomena of “booty-call relationships,” “friends with benefits,” and “sexting,” or the nearly ubiquitous and increasingly legal use of noninjectable mind-altering drugs, all of which facilitate the perpetuation of STDs.9-11 Finally, those who removed “syphilology” from that journal title certainly did not foresee the worldwide epidemic now known as human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, which has most assuredly helped keep syphilis a modern day menace.12-14