User login

Letter to the Editor: Therapeutic hypothermia for newborns

“PROTECTING THE NEWBORN BRAIN—THE FINAL FRONTIER IN OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL CARE”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (AUGUST 2016)

Therapeutic hypothermia

I practice in a small community hospital without a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We have always paid attention to warming neonates. Although we cannot start neonatal therapeutic hypothermia, as Dr. Barbieri discusses in his August Editorial, would there be any benefit to avoiding purposefully warming infants who are depressed at birth? NICU care requires a pediatric transport team, which takes at least an hour to arrive.

Jane Dawson, MD

Maryville, Missouri

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Dawson for her observations and query. I agree that at a hospital without a NICU, pending the arrival of a pediatric transport team, clinicians should strive to prevent hyperthermia in a newborn with encephalopathy because hyperthermia might exacerbate the ischemic injury. It may make sense to avoid aggressive warming of the newborn to permit the core temperature to decrease in order to begin the hypothermia process.

“PROTECTING THE NEWBORN BRAIN—THE FINAL FRONTIER IN OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL CARE”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (AUGUST 2016)

Therapeutic hypothermia

I practice in a small community hospital without a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We have always paid attention to warming neonates. Although we cannot start neonatal therapeutic hypothermia, as Dr. Barbieri discusses in his August Editorial, would there be any benefit to avoiding purposefully warming infants who are depressed at birth? NICU care requires a pediatric transport team, which takes at least an hour to arrive.

Jane Dawson, MD

Maryville, Missouri

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Dawson for her observations and query. I agree that at a hospital without a NICU, pending the arrival of a pediatric transport team, clinicians should strive to prevent hyperthermia in a newborn with encephalopathy because hyperthermia might exacerbate the ischemic injury. It may make sense to avoid aggressive warming of the newborn to permit the core temperature to decrease in order to begin the hypothermia process.

“PROTECTING THE NEWBORN BRAIN—THE FINAL FRONTIER IN OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL CARE”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (AUGUST 2016)

Therapeutic hypothermia

I practice in a small community hospital without a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We have always paid attention to warming neonates. Although we cannot start neonatal therapeutic hypothermia, as Dr. Barbieri discusses in his August Editorial, would there be any benefit to avoiding purposefully warming infants who are depressed at birth? NICU care requires a pediatric transport team, which takes at least an hour to arrive.

Jane Dawson, MD

Maryville, Missouri

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Dawson for her observations and query. I agree that at a hospital without a NICU, pending the arrival of a pediatric transport team, clinicians should strive to prevent hyperthermia in a newborn with encephalopathy because hyperthermia might exacerbate the ischemic injury. It may make sense to avoid aggressive warming of the newborn to permit the core temperature to decrease in order to begin the hypothermia process.

Letters to the Editor: Managing impacted fetal head at cesarean

“STOP USING INSTRUMENTS TO ASSIST WITH DELIVERY OF THE HEAD AT CESAREAN; START DISENGAGING THE HEAD PRIOR TO SURGERY”

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA (AUGUST 2016)

Patient positioning helps in managing impacted fetal head

As a general practice ObGyn, I have seen an increasing incidence of difficult cesareans as a result of prolonged second stage of labor. Dr. Norwitz cites this increase in his article. I have found that trying to elevate the fetal head prior to the start of surgery has been remarkably ineffective. In my practice, I place all my patients with second-stage arrest in low lithotomy stirrups (“blue fins”); this allows the nurses easier access to the vagina to elevate the head at surgery while I am reaching down from above. Usually, this facilitates delivery. It also allows better assessment of blood loss through the vagina as the cesarean progresses, and it makes placement of a Bakri balloon easier if necessary. If stirrups are not available, the patient can be placed in frog leg positioning so that my assistant can reach down and elevate the head if necessary. I find that in a patient with a very small pelvis, it is hard to get my hand down to the baby’s head. I have not yet done a breech extraction, but I know it is possible. I would probably try nitroglycerin first.

I think that difficult cesarean delivery is much more common than difficult shoulder dystocia, and we should develop standard procedures for addressing the issue and use simulation models to practice. In my time-out prior to surgery, I discuss my concerns so that everyone is ready for it, including the anesthesiologist/CRNA, and we have nitroglycerin available to relax the uterus if necessary. I hope that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will develop a committee opinion about this very important issue.

Marguerite P. Cohen, MD

Portland, Oregon

Assistant is key in disengaging fetal head

Disengaging the head by an assistant during a cesarean delivery is probably the most successful and useful method for managing an impacted fetal head at cesarean. The disengagement of the head prior to cesarean is practiced routinely in Europe, where forceps delivery is frequently performed. However, the disengagement should be done in the operating room (OR) just prior to or during the cesarean. To perform this in the delivery room, as suggested in Dr. Norwitz’s article, risks the associated fetal bradycardia due to head compression that might compromise an already compromised fetus. In addition, there is a risk of cord prolapse or release of excessive amniotic fluid resulting in cord compression. Also, in many hospitals in the United States, there is some delay to perform the cesarean because the OR is on a different floor from the labor and delivery room and the OR staff come from home.

Vacuum extraction can be safely used for the extraction of the head if it is not possible to deliver it manually. However, the head should be manually disimpacted and rotated to occiput anterior prior to application of the vacuum. But the presence of caput might pose some difficulty with proper application and traction.

It is important to remember that the risk factors for an impacted fetal head are also risk factors for postoperative infection. Therefore, vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution should be considered prior to cesarean delivery for all patients in labor.1

Raymond Michael, MD

Marshall, Minnesota

Reference

- Haas DM, Morgan Al Darei S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD007892.

“STOP USING INSTRUMENTS TO ASSIST WITH DELIVERY OF THE HEAD AT CESAREAN; START DISENGAGING THE HEAD PRIOR TO SURGERY”

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA (AUGUST 2016)

Patient positioning helps in managing impacted fetal head

As a general practice ObGyn, I have seen an increasing incidence of difficult cesareans as a result of prolonged second stage of labor. Dr. Norwitz cites this increase in his article. I have found that trying to elevate the fetal head prior to the start of surgery has been remarkably ineffective. In my practice, I place all my patients with second-stage arrest in low lithotomy stirrups (“blue fins”); this allows the nurses easier access to the vagina to elevate the head at surgery while I am reaching down from above. Usually, this facilitates delivery. It also allows better assessment of blood loss through the vagina as the cesarean progresses, and it makes placement of a Bakri balloon easier if necessary. If stirrups are not available, the patient can be placed in frog leg positioning so that my assistant can reach down and elevate the head if necessary. I find that in a patient with a very small pelvis, it is hard to get my hand down to the baby’s head. I have not yet done a breech extraction, but I know it is possible. I would probably try nitroglycerin first.

I think that difficult cesarean delivery is much more common than difficult shoulder dystocia, and we should develop standard procedures for addressing the issue and use simulation models to practice. In my time-out prior to surgery, I discuss my concerns so that everyone is ready for it, including the anesthesiologist/CRNA, and we have nitroglycerin available to relax the uterus if necessary. I hope that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will develop a committee opinion about this very important issue.

Marguerite P. Cohen, MD

Portland, Oregon

Assistant is key in disengaging fetal head

Disengaging the head by an assistant during a cesarean delivery is probably the most successful and useful method for managing an impacted fetal head at cesarean. The disengagement of the head prior to cesarean is practiced routinely in Europe, where forceps delivery is frequently performed. However, the disengagement should be done in the operating room (OR) just prior to or during the cesarean. To perform this in the delivery room, as suggested in Dr. Norwitz’s article, risks the associated fetal bradycardia due to head compression that might compromise an already compromised fetus. In addition, there is a risk of cord prolapse or release of excessive amniotic fluid resulting in cord compression. Also, in many hospitals in the United States, there is some delay to perform the cesarean because the OR is on a different floor from the labor and delivery room and the OR staff come from home.

Vacuum extraction can be safely used for the extraction of the head if it is not possible to deliver it manually. However, the head should be manually disimpacted and rotated to occiput anterior prior to application of the vacuum. But the presence of caput might pose some difficulty with proper application and traction.

It is important to remember that the risk factors for an impacted fetal head are also risk factors for postoperative infection. Therefore, vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution should be considered prior to cesarean delivery for all patients in labor.1

Raymond Michael, MD

Marshall, Minnesota

Reference

- Haas DM, Morgan Al Darei S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD007892.

“STOP USING INSTRUMENTS TO ASSIST WITH DELIVERY OF THE HEAD AT CESAREAN; START DISENGAGING THE HEAD PRIOR TO SURGERY”

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA (AUGUST 2016)

Patient positioning helps in managing impacted fetal head

As a general practice ObGyn, I have seen an increasing incidence of difficult cesareans as a result of prolonged second stage of labor. Dr. Norwitz cites this increase in his article. I have found that trying to elevate the fetal head prior to the start of surgery has been remarkably ineffective. In my practice, I place all my patients with second-stage arrest in low lithotomy stirrups (“blue fins”); this allows the nurses easier access to the vagina to elevate the head at surgery while I am reaching down from above. Usually, this facilitates delivery. It also allows better assessment of blood loss through the vagina as the cesarean progresses, and it makes placement of a Bakri balloon easier if necessary. If stirrups are not available, the patient can be placed in frog leg positioning so that my assistant can reach down and elevate the head if necessary. I find that in a patient with a very small pelvis, it is hard to get my hand down to the baby’s head. I have not yet done a breech extraction, but I know it is possible. I would probably try nitroglycerin first.

I think that difficult cesarean delivery is much more common than difficult shoulder dystocia, and we should develop standard procedures for addressing the issue and use simulation models to practice. In my time-out prior to surgery, I discuss my concerns so that everyone is ready for it, including the anesthesiologist/CRNA, and we have nitroglycerin available to relax the uterus if necessary. I hope that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will develop a committee opinion about this very important issue.

Marguerite P. Cohen, MD

Portland, Oregon

Assistant is key in disengaging fetal head

Disengaging the head by an assistant during a cesarean delivery is probably the most successful and useful method for managing an impacted fetal head at cesarean. The disengagement of the head prior to cesarean is practiced routinely in Europe, where forceps delivery is frequently performed. However, the disengagement should be done in the operating room (OR) just prior to or during the cesarean. To perform this in the delivery room, as suggested in Dr. Norwitz’s article, risks the associated fetal bradycardia due to head compression that might compromise an already compromised fetus. In addition, there is a risk of cord prolapse or release of excessive amniotic fluid resulting in cord compression. Also, in many hospitals in the United States, there is some delay to perform the cesarean because the OR is on a different floor from the labor and delivery room and the OR staff come from home.

Vacuum extraction can be safely used for the extraction of the head if it is not possible to deliver it manually. However, the head should be manually disimpacted and rotated to occiput anterior prior to application of the vacuum. But the presence of caput might pose some difficulty with proper application and traction.

It is important to remember that the risk factors for an impacted fetal head are also risk factors for postoperative infection. Therefore, vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution should be considered prior to cesarean delivery for all patients in labor.1

Raymond Michael, MD

Marshall, Minnesota

Reference

- Haas DM, Morgan Al Darei S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD007892.

Forget the myths and help your psychiatric patients quit smoking

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

HPV vaccine and adolescents: What we say really does matter

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

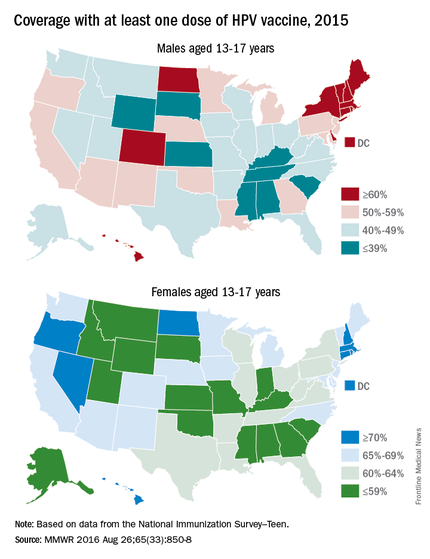

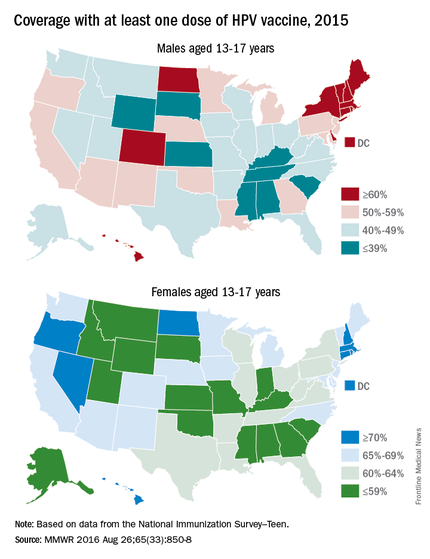

Vaccine coverage

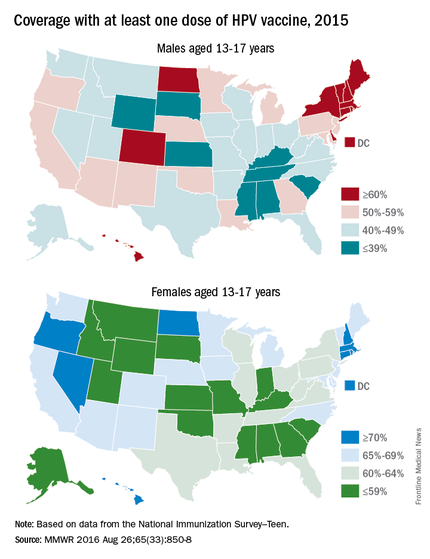

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

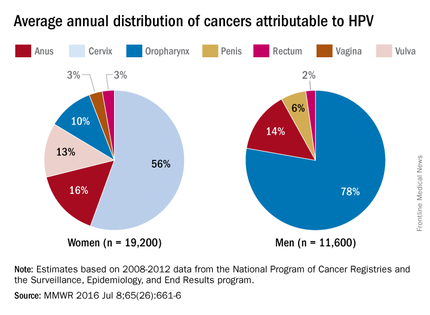

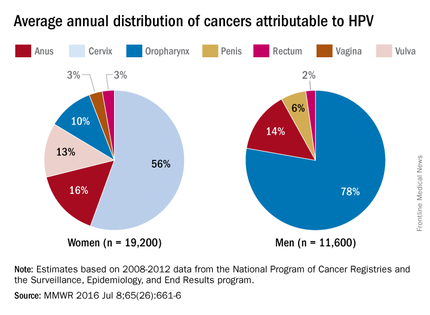

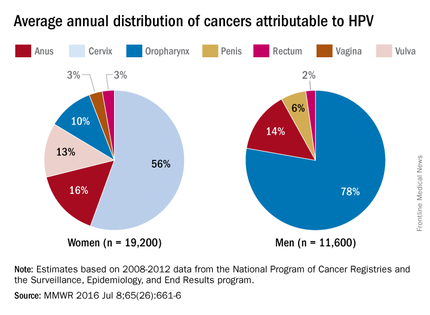

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Miscellany

Many interesting things happen in a medical office, most of which don’t merit a full column. Here are some from my own past few months:

Endocrine Knee? I was hard put to explain the calluses on both my patient’s knees. As I tried to formulate a question, he rescued me by saying, “I’m an endocrinologist. I spend a lot of my time on my knees, trimming the toenails of elderly diabetics.”

Who knew? At least bending the knee to insurers and regulators doesn’t require keratolytics ...

You can get anything online. My patient was about to graduate with a degree in psychoanalysis. “I have to set up my office,” she said, “drapes, analyst couch, and so forth.”

“Where do you buy an analyst couch?” I asked.

“Analyticcouch.com,” she explained. “Available in a variety of colors.”

What a country!

No I’m not, Officer! Many patients consider removing facial red spots that make them self-conscious, but Harriet’s reason was unique. “I got pulled over by a cop for an illegal change of lanes,” she said. “When he saw the red spot under my eye, he assumed I was a drunk. ‘Get over there, punk,’ he said.”

The other bathroom is upstairs. Stan listed his occupation as “muralist.” Picturing him sneaking up to blank walls on street corners in the middle of the night with a can of Benjamin Moore to ply his trade, I asked where he draws his murals.

“Most of my work is residential,” he said. “For instance, last year I did a bathroom in Framingham. The motif they wanted was ancient Egypt. I had to do a lot of research on the 18th dynasty, to get the details exactly right.”

That made sense. You wouldn’t want a dangling hieroglyphic participle in your downstairs lavatory. I asked him how it worked out.

“The client was delighted,” he said, “only there was one problem. Whenever guests came over for a dinner party, there was always a long line, because whoever was in the bathroom wouldn’t come out.”

There are always alternatives. By now I am used to hearing patients extol the virtues of exotic treatments: Vicks VapoRub for toenail tinea, tea tree oil for most anything. Apple cider vinegar for everything else.

Then the other day Marcy surprised me with this:

“I stopped the minocycline,” she said, “Instead I started using celery, which I ground up and boiled and then froze and then applied to the face.”

A little bit of a production, perhaps – grinding, boiling, freezing. As long as it works ...

You need a different kind of doctor. “I see I won’t be able to shower for 3 days,” said the new patient.

My jaw dropped, but no words came out.

“It’s that sign you put up,” he said, “right on the exam room door.”

As I don’t usually read my own signs, I turned to look. The sign read:

“If you have no-showed without notice three times, we reserve the right to reschedule you at our convenience.”

“It says, ‘No-Showed,” I said. Not ‘No Showers.”

I resisted the urge to refer him to an optometrist.

This reminded me of another episode some time ago, when a patient listed his Chief Complaint as, “I want Lasik Surgery.”

“Forgive me,” I said, “but why would you ask a dermatologist for Lasik surgery?”

“Doesn’t the sign on your door say, “Boston Ophthalmology?” he asked.

“Upstairs,” I said. “Seventh floor.”

Negotiating with Father Time. We suspected porphyria, and ordered a 24-hour urine collection. “I’m a busy executive,” said the patient. “I haven’t got time to collect it for that long.”

“But it has to be a whole day ...”

“Fifteen hours,” he said. “I’ll give you 15 hours.”

“But we need ...”

“Eighteen hours. OK?”

“Well, not really. You see, the test has to be a whole day ...”

“All right, 21 hours. That’s my best offer.”

Maybe if I could get him to spend the day in that Egyptian bathroom ...

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass, and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is now available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at [email protected].

Many interesting things happen in a medical office, most of which don’t merit a full column. Here are some from my own past few months:

Endocrine Knee? I was hard put to explain the calluses on both my patient’s knees. As I tried to formulate a question, he rescued me by saying, “I’m an endocrinologist. I spend a lot of my time on my knees, trimming the toenails of elderly diabetics.”

Who knew? At least bending the knee to insurers and regulators doesn’t require keratolytics ...

You can get anything online. My patient was about to graduate with a degree in psychoanalysis. “I have to set up my office,” she said, “drapes, analyst couch, and so forth.”

“Where do you buy an analyst couch?” I asked.

“Analyticcouch.com,” she explained. “Available in a variety of colors.”

What a country!

No I’m not, Officer! Many patients consider removing facial red spots that make them self-conscious, but Harriet’s reason was unique. “I got pulled over by a cop for an illegal change of lanes,” she said. “When he saw the red spot under my eye, he assumed I was a drunk. ‘Get over there, punk,’ he said.”

The other bathroom is upstairs. Stan listed his occupation as “muralist.” Picturing him sneaking up to blank walls on street corners in the middle of the night with a can of Benjamin Moore to ply his trade, I asked where he draws his murals.

“Most of my work is residential,” he said. “For instance, last year I did a bathroom in Framingham. The motif they wanted was ancient Egypt. I had to do a lot of research on the 18th dynasty, to get the details exactly right.”

That made sense. You wouldn’t want a dangling hieroglyphic participle in your downstairs lavatory. I asked him how it worked out.

“The client was delighted,” he said, “only there was one problem. Whenever guests came over for a dinner party, there was always a long line, because whoever was in the bathroom wouldn’t come out.”

There are always alternatives. By now I am used to hearing patients extol the virtues of exotic treatments: Vicks VapoRub for toenail tinea, tea tree oil for most anything. Apple cider vinegar for everything else.

Then the other day Marcy surprised me with this:

“I stopped the minocycline,” she said, “Instead I started using celery, which I ground up and boiled and then froze and then applied to the face.”

A little bit of a production, perhaps – grinding, boiling, freezing. As long as it works ...

You need a different kind of doctor. “I see I won’t be able to shower for 3 days,” said the new patient.

My jaw dropped, but no words came out.

“It’s that sign you put up,” he said, “right on the exam room door.”

As I don’t usually read my own signs, I turned to look. The sign read:

“If you have no-showed without notice three times, we reserve the right to reschedule you at our convenience.”

“It says, ‘No-Showed,” I said. Not ‘No Showers.”

I resisted the urge to refer him to an optometrist.

This reminded me of another episode some time ago, when a patient listed his Chief Complaint as, “I want Lasik Surgery.”

“Forgive me,” I said, “but why would you ask a dermatologist for Lasik surgery?”

“Doesn’t the sign on your door say, “Boston Ophthalmology?” he asked.

“Upstairs,” I said. “Seventh floor.”

Negotiating with Father Time. We suspected porphyria, and ordered a 24-hour urine collection. “I’m a busy executive,” said the patient. “I haven’t got time to collect it for that long.”

“But it has to be a whole day ...”

“Fifteen hours,” he said. “I’ll give you 15 hours.”

“But we need ...”

“Eighteen hours. OK?”

“Well, not really. You see, the test has to be a whole day ...”

“All right, 21 hours. That’s my best offer.”

Maybe if I could get him to spend the day in that Egyptian bathroom ...

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass, and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is now available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at [email protected].

Many interesting things happen in a medical office, most of which don’t merit a full column. Here are some from my own past few months:

Endocrine Knee? I was hard put to explain the calluses on both my patient’s knees. As I tried to formulate a question, he rescued me by saying, “I’m an endocrinologist. I spend a lot of my time on my knees, trimming the toenails of elderly diabetics.”

Who knew? At least bending the knee to insurers and regulators doesn’t require keratolytics ...

You can get anything online. My patient was about to graduate with a degree in psychoanalysis. “I have to set up my office,” she said, “drapes, analyst couch, and so forth.”

“Where do you buy an analyst couch?” I asked.

“Analyticcouch.com,” she explained. “Available in a variety of colors.”

What a country!

No I’m not, Officer! Many patients consider removing facial red spots that make them self-conscious, but Harriet’s reason was unique. “I got pulled over by a cop for an illegal change of lanes,” she said. “When he saw the red spot under my eye, he assumed I was a drunk. ‘Get over there, punk,’ he said.”

The other bathroom is upstairs. Stan listed his occupation as “muralist.” Picturing him sneaking up to blank walls on street corners in the middle of the night with a can of Benjamin Moore to ply his trade, I asked where he draws his murals.

“Most of my work is residential,” he said. “For instance, last year I did a bathroom in Framingham. The motif they wanted was ancient Egypt. I had to do a lot of research on the 18th dynasty, to get the details exactly right.”

That made sense. You wouldn’t want a dangling hieroglyphic participle in your downstairs lavatory. I asked him how it worked out.

“The client was delighted,” he said, “only there was one problem. Whenever guests came over for a dinner party, there was always a long line, because whoever was in the bathroom wouldn’t come out.”

There are always alternatives. By now I am used to hearing patients extol the virtues of exotic treatments: Vicks VapoRub for toenail tinea, tea tree oil for most anything. Apple cider vinegar for everything else.

Then the other day Marcy surprised me with this:

“I stopped the minocycline,” she said, “Instead I started using celery, which I ground up and boiled and then froze and then applied to the face.”

A little bit of a production, perhaps – grinding, boiling, freezing. As long as it works ...

You need a different kind of doctor. “I see I won’t be able to shower for 3 days,” said the new patient.

My jaw dropped, but no words came out.

“It’s that sign you put up,” he said, “right on the exam room door.”

As I don’t usually read my own signs, I turned to look. The sign read:

“If you have no-showed without notice three times, we reserve the right to reschedule you at our convenience.”

“It says, ‘No-Showed,” I said. Not ‘No Showers.”

I resisted the urge to refer him to an optometrist.

This reminded me of another episode some time ago, when a patient listed his Chief Complaint as, “I want Lasik Surgery.”

“Forgive me,” I said, “but why would you ask a dermatologist for Lasik surgery?”

“Doesn’t the sign on your door say, “Boston Ophthalmology?” he asked.

“Upstairs,” I said. “Seventh floor.”

Negotiating with Father Time. We suspected porphyria, and ordered a 24-hour urine collection. “I’m a busy executive,” said the patient. “I haven’t got time to collect it for that long.”

“But it has to be a whole day ...”

“Fifteen hours,” he said. “I’ll give you 15 hours.”

“But we need ...”

“Eighteen hours. OK?”

“Well, not really. You see, the test has to be a whole day ...”

“All right, 21 hours. That’s my best offer.”

Maybe if I could get him to spend the day in that Egyptian bathroom ...

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass, and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is now available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at [email protected].

Do as I say, not as I do! A futile plea

I am constantly amazed when parents come in complaining about their child’s nail biting or irritable attitude “no matter how many times I tell her” as they do these same things in front of me!

We have not evolved that far from our nonverbal ancestors to expect that words will speak louder than actions. Looking closely, you can see even very young infants gazing closely at their parents, then mirroring their facial expressions a few minutes later (because of slower processing). Mirroring is probably the correct word for this as the mirror neuron system of the brain has as its primary and crucial function allowing humans to copy what they see in others.

Children look to model, especially those who are slightly older and more adept than they are. Older siblings bask in this adoration at times and squeal in frustration at other times that their younger sister is “mocking” them by copying their speech and actions. When children are picking up serious negative behaviors from siblings or peers, particularly in adolescence, we need to coach parents to take action.

But watching parents is the most powerful or “salient” stimulus for learning. Some theorize that the long period of childhood evolved to allow children to learn the incredible amount of information necessary to live independently in our complex culture. This learning begins very early and requires close contact and careful observation of the minute details of how the parent survives every day.

Eating is a great primitive example of why children must model their parents. How do animals know which plants are poisonous? By watching others eat and spit, choke, or vomit. Entire families have nonpreferred foods passed on by modeling refusal as well as lack of exposure on the table. Conversely, picky eaters need to observe others, preferably admired peers and parents, eating those vegetables. (Tasting is also necessary, but that’s a topic for another day!) It is worth asking about family meals, without the distraction of a TV, as they are key moments to model nutritious eating for their lifetime.

In “underdeveloped” countries, infants are naturally carried everywhere and observing constantly. In our “developed” country, many infants spend hours each day at day care, modeling their caregivers or watching media examples of people interacting, which may not be the models parents would consciously choose. Parents often ask us about childcare, anxious about the extremely rare threat of abduction, when we should instead be advising them about what models they want for their children during this critical learning period.

Emotion cueing is a crucial component of modeling and an untaught constant of typical parent-child interaction. Crawling infants placed on a clear surface over a “visual cliff” that appeared to be a sudden precipice look to the parent’s affect to decide how to act. The mother was instructed to show fear or joy when her baby reached the apparent danger and looked up for a warning. When fear was shown, the infants backed off and cried. When joy was shown, the baby crawled gaily across the “cliff.” For parents who do not come by signaling confidence naturally but want to model this for their children, I advise they “fake it until you make it!”

Parents are instructing their progeny in how to feel and act in every situation, whether they know it or not. Confident parents model bravery; kind parents model compassion; flexible parents model resilience; patient parents model tolerance; anxious parents model caution; angry parents model aggression. Ignoring parents (think: on their cellphone, distracted, depressed, inebriated, or high) leave their children to feel confused and insecure. An adaptive child of an ignoring parent may demand information by crying, clinging, fighting with siblings, or hitting the parent. They are desperate for the parental attention to teach them and keep them safe. A more passive child may become increasingly inhibited in their exploration of the world. We need to consider possible modeling failures when such child reaction patterns are the complaint, and remember that the adverse model may not be in the room, requiring us to ask, “What other adult models does he see?”

Studies have shown that infants learn resilience when experiencing “mistakes” in parent-infant interaction; learning how to tolerate and repair an interaction that is not perfect. This is really good news for parents who feel that they must be perfect models for their children! For parents of anxious or obsessive children, I sometimes prescribe making mistakes and saying “Oh well,” as well as rewarding the child when they can say “Oh well” themselves. No child is too old to benefit from observing a parent apologize sincerely for a mistake.

Language is modeled, right down to accent. But when parents complain about their child cussing, raising their voice in anger, having an “attitude,” or “talking back,” it is worth asking (parent and child) “Where do you think they/you have heard talk like that?” It may be childcare providers, peers, TV, video games or online media (all of which may warrant a change), but it also may reflect interactions at home.