User login

NOACs outpace warfarin for afib anticoagulation

The NOAC revolution has happened.

New oral anticoagulants (NOACs) now claim the majority of the oral anticoagulant market in patients with new atrial fibrillation, wresting the advantage from warfarin in the U.S. and globally. This is the promise NOACs held even while still in development, the potential to whittle warfarin use down to a shadow of what it was. Despite a sputtering reception when the first NOAC, dabigatran (Pradaxa), came onto the U.S. market in late 2010, the four NOACs (also apixaban [Eliquis], edoxaban [Savaysa], and rivaroxaban [Xarelto]) now available in the United States and elsewhere gradually gained traction and today they collectively form the most widely used oral anticoagulant option for patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation.

Data reported in August at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology showed that in Denmark during the first half of 2015, NOACs accounted for 73% of oral anticoagulant prescriptions for patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation, Kasper Gadsboll, MD, reported. He and his associates studied NOAC and warfarin use in a total of 108,410 atrial fibrillation patients newly diagnosed starting in 2005. Through 2010, warfarin was the only option, but starting in early 2011 when the first NOAC became available in Denmark, use of the class rose sharply with a corresponding plummet in warfarin prescriptions. Not only did the NOACs largely supplant warfarin during 2011-2015, but they also powered an overall rise in the percentage of atrial fibrillation patients treated with an oral anticoagulant, boosting the rate by a relative 75% between the end of 2009 and mid-2015.

“People were reluctant to start an oral anticoagulant because they feared bleeding. Now with NOACs they are not as fearful,” said Dr. Gadsboll, a cardiology researcher at Gentofte Hospital in Hellerup, Denmark. He also noted that in Denmark the national health system pays for prescribed drugs, so the increased direct cost for NOAC treatment in place of warfarin is covered by the Danish government.

“NOAC uptake is gathering steam,” commented Stuart J. Connolly, MD, an electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “When the government pays for it, people prescribe it more, but increased NOAC use is happening everywhere,” said Dr. Connolly, who led major trials that assessed dabigatran and apixaban in atrial fibrillation patients. “I’ve seen Canadian data that show warfarin use is falling and NOAC use is increasing. People are more willing to prescribe NOACs because they are safer,” he said in an interview.

The most current U.S. data I found came from the IMS Health National Disease and Therapeutic Index in 2014, based on a survey of a representative sample of about 4,800 U.S. office-based physicians. The results showed that the NOAC share of oral anticoagulant use in patients who had office visits for atrial fibrillation jumped from 6% of patients in early 2011 to roughly half of all atrial fibrillation patients, 48%, during 2014 (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1300-5). That trajectory makes it likely that by now NOACs have a clear lead.

It’s a similar story in several European countries, such as in Belgium where NOACs now account for about 70% of new prescriptions for atrial fibrillation patients, commented Freek W.A. Verheugt, MD. In the Netherlands, however, NOACs have not taken off, in large part because a popular and entrenched thrombosis clinic system exists that employs thousands of Dutch workers, thereby making choice of an anticoagulant drug a social and political question as well as a medical one, he said. “Warfarin is still indicated for patients with an artificial heart valve or poor kidney function,” noted Dr. Verheugt, professor of cardiology at the University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands, “but a majority of atrial fibrillation patients will eventually change to a NOAC. Even when treatment with warfarin has a good time-in-therapeutic-range, NOACs are still better. They are so much safer.”

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The NOAC revolution has happened.

New oral anticoagulants (NOACs) now claim the majority of the oral anticoagulant market in patients with new atrial fibrillation, wresting the advantage from warfarin in the U.S. and globally. This is the promise NOACs held even while still in development, the potential to whittle warfarin use down to a shadow of what it was. Despite a sputtering reception when the first NOAC, dabigatran (Pradaxa), came onto the U.S. market in late 2010, the four NOACs (also apixaban [Eliquis], edoxaban [Savaysa], and rivaroxaban [Xarelto]) now available in the United States and elsewhere gradually gained traction and today they collectively form the most widely used oral anticoagulant option for patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation.

Data reported in August at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology showed that in Denmark during the first half of 2015, NOACs accounted for 73% of oral anticoagulant prescriptions for patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation, Kasper Gadsboll, MD, reported. He and his associates studied NOAC and warfarin use in a total of 108,410 atrial fibrillation patients newly diagnosed starting in 2005. Through 2010, warfarin was the only option, but starting in early 2011 when the first NOAC became available in Denmark, use of the class rose sharply with a corresponding plummet in warfarin prescriptions. Not only did the NOACs largely supplant warfarin during 2011-2015, but they also powered an overall rise in the percentage of atrial fibrillation patients treated with an oral anticoagulant, boosting the rate by a relative 75% between the end of 2009 and mid-2015.

“People were reluctant to start an oral anticoagulant because they feared bleeding. Now with NOACs they are not as fearful,” said Dr. Gadsboll, a cardiology researcher at Gentofte Hospital in Hellerup, Denmark. He also noted that in Denmark the national health system pays for prescribed drugs, so the increased direct cost for NOAC treatment in place of warfarin is covered by the Danish government.

“NOAC uptake is gathering steam,” commented Stuart J. Connolly, MD, an electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “When the government pays for it, people prescribe it more, but increased NOAC use is happening everywhere,” said Dr. Connolly, who led major trials that assessed dabigatran and apixaban in atrial fibrillation patients. “I’ve seen Canadian data that show warfarin use is falling and NOAC use is increasing. People are more willing to prescribe NOACs because they are safer,” he said in an interview.

The most current U.S. data I found came from the IMS Health National Disease and Therapeutic Index in 2014, based on a survey of a representative sample of about 4,800 U.S. office-based physicians. The results showed that the NOAC share of oral anticoagulant use in patients who had office visits for atrial fibrillation jumped from 6% of patients in early 2011 to roughly half of all atrial fibrillation patients, 48%, during 2014 (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1300-5). That trajectory makes it likely that by now NOACs have a clear lead.

It’s a similar story in several European countries, such as in Belgium where NOACs now account for about 70% of new prescriptions for atrial fibrillation patients, commented Freek W.A. Verheugt, MD. In the Netherlands, however, NOACs have not taken off, in large part because a popular and entrenched thrombosis clinic system exists that employs thousands of Dutch workers, thereby making choice of an anticoagulant drug a social and political question as well as a medical one, he said. “Warfarin is still indicated for patients with an artificial heart valve or poor kidney function,” noted Dr. Verheugt, professor of cardiology at the University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands, “but a majority of atrial fibrillation patients will eventually change to a NOAC. Even when treatment with warfarin has a good time-in-therapeutic-range, NOACs are still better. They are so much safer.”

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The NOAC revolution has happened.

New oral anticoagulants (NOACs) now claim the majority of the oral anticoagulant market in patients with new atrial fibrillation, wresting the advantage from warfarin in the U.S. and globally. This is the promise NOACs held even while still in development, the potential to whittle warfarin use down to a shadow of what it was. Despite a sputtering reception when the first NOAC, dabigatran (Pradaxa), came onto the U.S. market in late 2010, the four NOACs (also apixaban [Eliquis], edoxaban [Savaysa], and rivaroxaban [Xarelto]) now available in the United States and elsewhere gradually gained traction and today they collectively form the most widely used oral anticoagulant option for patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation.

Data reported in August at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology showed that in Denmark during the first half of 2015, NOACs accounted for 73% of oral anticoagulant prescriptions for patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation, Kasper Gadsboll, MD, reported. He and his associates studied NOAC and warfarin use in a total of 108,410 atrial fibrillation patients newly diagnosed starting in 2005. Through 2010, warfarin was the only option, but starting in early 2011 when the first NOAC became available in Denmark, use of the class rose sharply with a corresponding plummet in warfarin prescriptions. Not only did the NOACs largely supplant warfarin during 2011-2015, but they also powered an overall rise in the percentage of atrial fibrillation patients treated with an oral anticoagulant, boosting the rate by a relative 75% between the end of 2009 and mid-2015.

“People were reluctant to start an oral anticoagulant because they feared bleeding. Now with NOACs they are not as fearful,” said Dr. Gadsboll, a cardiology researcher at Gentofte Hospital in Hellerup, Denmark. He also noted that in Denmark the national health system pays for prescribed drugs, so the increased direct cost for NOAC treatment in place of warfarin is covered by the Danish government.

“NOAC uptake is gathering steam,” commented Stuart J. Connolly, MD, an electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “When the government pays for it, people prescribe it more, but increased NOAC use is happening everywhere,” said Dr. Connolly, who led major trials that assessed dabigatran and apixaban in atrial fibrillation patients. “I’ve seen Canadian data that show warfarin use is falling and NOAC use is increasing. People are more willing to prescribe NOACs because they are safer,” he said in an interview.

The most current U.S. data I found came from the IMS Health National Disease and Therapeutic Index in 2014, based on a survey of a representative sample of about 4,800 U.S. office-based physicians. The results showed that the NOAC share of oral anticoagulant use in patients who had office visits for atrial fibrillation jumped from 6% of patients in early 2011 to roughly half of all atrial fibrillation patients, 48%, during 2014 (Am J Med. 2015 Dec;128[12]:1300-5). That trajectory makes it likely that by now NOACs have a clear lead.

It’s a similar story in several European countries, such as in Belgium where NOACs now account for about 70% of new prescriptions for atrial fibrillation patients, commented Freek W.A. Verheugt, MD. In the Netherlands, however, NOACs have not taken off, in large part because a popular and entrenched thrombosis clinic system exists that employs thousands of Dutch workers, thereby making choice of an anticoagulant drug a social and political question as well as a medical one, he said. “Warfarin is still indicated for patients with an artificial heart valve or poor kidney function,” noted Dr. Verheugt, professor of cardiology at the University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands, “but a majority of atrial fibrillation patients will eventually change to a NOAC. Even when treatment with warfarin has a good time-in-therapeutic-range, NOACs are still better. They are so much safer.”

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Update on the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock

Sepsis is the primary cause of death from infection. Early identification and treatment of sepsis is important in improving patient outcomes. The consensus conference sought to differentiate sepsis, which is defined as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” from uncomplicated infection.

Sepsis was last classified in a 2001 guideline that based its definition on the presence of two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, which included an elevated temperature, heart rate higher than 90 bpm, respiratory rate higher than 20 breaths per minute, and a white blood cell count greater than greater than 12,000 mcL or less than 4,000 mcL or greater than 10% immature bands.

The problem with the SIRS definition of sepsis is that while it reflects a response to infection, it does not sufficiently distinguish between individuals with infections and those with a dysregulated response that leads to a poor prognosis, which is the definition of sepsis. The current consensus conference redefines sepsis with a more direct emphasis on organ dysfunction, as this is the aspect of sepsis that is most clearly linked to patient outcomes.

In the consensus conference document, sepsis is defined as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.” The guidelines recommend using the quick version of the sequential (sepsis-related) organ failure assessment score (qSOFA) to identify patients with sepsis. In its long form, the SOFA used seven clinical and laboratory data points for completion, and is best suited to use in an intensive care setting where detailed data are available. The qSOFA score has only three criteria and by being easier to use can aid in rapid identification of sepsis and the patients most likely to deteriorate from sepsis.

The qSOFA criteria predict poor outcome in patients with infection who have two or more of the following: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/min, new or worsened altered mentation, or systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg. Unlike the full SOFA score, the qSOFA does not require any laboratory testing and so can be performed in the office or bedside on a hospital floor. The qSOFA does not necessarily define sepsis, rather it identifies patients at a higher risk of hospital death or prolonged ICU stay. The consensus conference suggests that “qSOFA criteria be used to prompt clinicians to further investigate for organ dysfunction, initiate or escalate therapy as appropriate, and consider referral to critical care or increase the frequency of monitoring, if such actions have not already been undertaken.” The task force suggested that the qSOFA score may be a helpful adjunct to best clinical judgment for identifying patients who might benefit from a higher level of care.

Septic shock is defined as a subset of sepsis in which profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk for death than sepsis alone. Septic shock can be identified when, after adequate fluid resuscitation, the patient requires vasopressor therapy to maintain mean arterial pressure of at least 65 mm Hg and has a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L.

Once sepsis is suspected, prompt therapy needs to be started as per the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines. The qSOFA criteria can be used to identify patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Within 3 hours, a lactate level should be obtained as well as blood cultures from two separate sites drawn prior to administration of antibiotics (but do not delay antibiotic administration). Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given within 45 minutes of the identification of sepsis. Antibiotic choice will vary per clinician/institution preference, but should likely include coverage for Pseudomonas and MRSA (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin, for example). Antibiotics should be reassessed daily for de-escalation. Administer 30 mL/kg crystalloid for hypotension or lactate greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L. Within 6 hours, vasopressors should be given for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of at least 65mm Hg. In the event of persistent hypotension after initial fluid administration (MAP under 65 mm Hg) or if initial lactate was greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L, volume status and tissue perfusion should be reassessed and lactate should be rechecked if it was initially elevated.

The bottom line

A 2016 international task force recommended that the definition of sepsis should be changed to emphasize organ dysfunction rather than a systemic inflammatory response. Use of the qSOFA score, which relies only on clinically observable data rather than laboratory evaluation, is recommended to identify patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Early recognition of sepsis and evaluation with qSOFT should facilitate early treatment and improve survival.

References

Singer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) FRCP; JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801-10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287.

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr;31(4):1250-6.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004 Mar;32(3):858-73.

Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine and department of physiology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Botti is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program department of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Sepsis is the primary cause of death from infection. Early identification and treatment of sepsis is important in improving patient outcomes. The consensus conference sought to differentiate sepsis, which is defined as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” from uncomplicated infection.

Sepsis was last classified in a 2001 guideline that based its definition on the presence of two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, which included an elevated temperature, heart rate higher than 90 bpm, respiratory rate higher than 20 breaths per minute, and a white blood cell count greater than greater than 12,000 mcL or less than 4,000 mcL or greater than 10% immature bands.

The problem with the SIRS definition of sepsis is that while it reflects a response to infection, it does not sufficiently distinguish between individuals with infections and those with a dysregulated response that leads to a poor prognosis, which is the definition of sepsis. The current consensus conference redefines sepsis with a more direct emphasis on organ dysfunction, as this is the aspect of sepsis that is most clearly linked to patient outcomes.

In the consensus conference document, sepsis is defined as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.” The guidelines recommend using the quick version of the sequential (sepsis-related) organ failure assessment score (qSOFA) to identify patients with sepsis. In its long form, the SOFA used seven clinical and laboratory data points for completion, and is best suited to use in an intensive care setting where detailed data are available. The qSOFA score has only three criteria and by being easier to use can aid in rapid identification of sepsis and the patients most likely to deteriorate from sepsis.

The qSOFA criteria predict poor outcome in patients with infection who have two or more of the following: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/min, new or worsened altered mentation, or systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg. Unlike the full SOFA score, the qSOFA does not require any laboratory testing and so can be performed in the office or bedside on a hospital floor. The qSOFA does not necessarily define sepsis, rather it identifies patients at a higher risk of hospital death or prolonged ICU stay. The consensus conference suggests that “qSOFA criteria be used to prompt clinicians to further investigate for organ dysfunction, initiate or escalate therapy as appropriate, and consider referral to critical care or increase the frequency of monitoring, if such actions have not already been undertaken.” The task force suggested that the qSOFA score may be a helpful adjunct to best clinical judgment for identifying patients who might benefit from a higher level of care.

Septic shock is defined as a subset of sepsis in which profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk for death than sepsis alone. Septic shock can be identified when, after adequate fluid resuscitation, the patient requires vasopressor therapy to maintain mean arterial pressure of at least 65 mm Hg and has a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L.

Once sepsis is suspected, prompt therapy needs to be started as per the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines. The qSOFA criteria can be used to identify patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Within 3 hours, a lactate level should be obtained as well as blood cultures from two separate sites drawn prior to administration of antibiotics (but do not delay antibiotic administration). Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given within 45 minutes of the identification of sepsis. Antibiotic choice will vary per clinician/institution preference, but should likely include coverage for Pseudomonas and MRSA (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin, for example). Antibiotics should be reassessed daily for de-escalation. Administer 30 mL/kg crystalloid for hypotension or lactate greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L. Within 6 hours, vasopressors should be given for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of at least 65mm Hg. In the event of persistent hypotension after initial fluid administration (MAP under 65 mm Hg) or if initial lactate was greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L, volume status and tissue perfusion should be reassessed and lactate should be rechecked if it was initially elevated.

The bottom line

A 2016 international task force recommended that the definition of sepsis should be changed to emphasize organ dysfunction rather than a systemic inflammatory response. Use of the qSOFA score, which relies only on clinically observable data rather than laboratory evaluation, is recommended to identify patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Early recognition of sepsis and evaluation with qSOFT should facilitate early treatment and improve survival.

References

Singer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) FRCP; JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801-10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287.

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr;31(4):1250-6.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004 Mar;32(3):858-73.

Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine and department of physiology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Botti is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program department of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Sepsis is the primary cause of death from infection. Early identification and treatment of sepsis is important in improving patient outcomes. The consensus conference sought to differentiate sepsis, which is defined as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” from uncomplicated infection.

Sepsis was last classified in a 2001 guideline that based its definition on the presence of two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, which included an elevated temperature, heart rate higher than 90 bpm, respiratory rate higher than 20 breaths per minute, and a white blood cell count greater than greater than 12,000 mcL or less than 4,000 mcL or greater than 10% immature bands.

The problem with the SIRS definition of sepsis is that while it reflects a response to infection, it does not sufficiently distinguish between individuals with infections and those with a dysregulated response that leads to a poor prognosis, which is the definition of sepsis. The current consensus conference redefines sepsis with a more direct emphasis on organ dysfunction, as this is the aspect of sepsis that is most clearly linked to patient outcomes.

In the consensus conference document, sepsis is defined as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.” The guidelines recommend using the quick version of the sequential (sepsis-related) organ failure assessment score (qSOFA) to identify patients with sepsis. In its long form, the SOFA used seven clinical and laboratory data points for completion, and is best suited to use in an intensive care setting where detailed data are available. The qSOFA score has only three criteria and by being easier to use can aid in rapid identification of sepsis and the patients most likely to deteriorate from sepsis.

The qSOFA criteria predict poor outcome in patients with infection who have two or more of the following: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/min, new or worsened altered mentation, or systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg. Unlike the full SOFA score, the qSOFA does not require any laboratory testing and so can be performed in the office or bedside on a hospital floor. The qSOFA does not necessarily define sepsis, rather it identifies patients at a higher risk of hospital death or prolonged ICU stay. The consensus conference suggests that “qSOFA criteria be used to prompt clinicians to further investigate for organ dysfunction, initiate or escalate therapy as appropriate, and consider referral to critical care or increase the frequency of monitoring, if such actions have not already been undertaken.” The task force suggested that the qSOFA score may be a helpful adjunct to best clinical judgment for identifying patients who might benefit from a higher level of care.

Septic shock is defined as a subset of sepsis in which profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk for death than sepsis alone. Septic shock can be identified when, after adequate fluid resuscitation, the patient requires vasopressor therapy to maintain mean arterial pressure of at least 65 mm Hg and has a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L.

Once sepsis is suspected, prompt therapy needs to be started as per the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines. The qSOFA criteria can be used to identify patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Within 3 hours, a lactate level should be obtained as well as blood cultures from two separate sites drawn prior to administration of antibiotics (but do not delay antibiotic administration). Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given within 45 minutes of the identification of sepsis. Antibiotic choice will vary per clinician/institution preference, but should likely include coverage for Pseudomonas and MRSA (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin, for example). Antibiotics should be reassessed daily for de-escalation. Administer 30 mL/kg crystalloid for hypotension or lactate greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L. Within 6 hours, vasopressors should be given for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of at least 65mm Hg. In the event of persistent hypotension after initial fluid administration (MAP under 65 mm Hg) or if initial lactate was greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L, volume status and tissue perfusion should be reassessed and lactate should be rechecked if it was initially elevated.

The bottom line

A 2016 international task force recommended that the definition of sepsis should be changed to emphasize organ dysfunction rather than a systemic inflammatory response. Use of the qSOFA score, which relies only on clinically observable data rather than laboratory evaluation, is recommended to identify patients at high risk for morbidity and mortality. Early recognition of sepsis and evaluation with qSOFT should facilitate early treatment and improve survival.

References

Singer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) FRCP; JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801-10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287.

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr;31(4):1250-6.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004 Mar;32(3):858-73.

Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine and department of physiology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Botti is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program department of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Commentary: New treatments for new patients – A call to action for bariatric surgeons

How many common bile duct operations have you done lately? How about laparotomies for bleeding duodenal ulcers? How about central venous access catheters? How many procedures that you as a general surgeon may have done a few decades ago are now done primarily by endoscopists, radiologists, or others using minimal access for their procedures?

Now hold that thought, as we turn to the field of bariatric surgery.

Twenty years ago, in 1996, there were approximately 12,000 bariatric operations performed in the United States. From 1998 to 2004, that number increased to almost 136,000 per year (J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:261-6). What was the reason? While other factors likely had some influence, the overwhelming factor was that laparoscopic bariatric surgery became available. Patients perceived this approach as less invasive. Primary care referring physicians did as well.

The rapid rise in laparoscopy boosted the popularity of bariatric surgery but since that bump, the bariatric surgery numbers have remained flat. Currently, less than 2% of eligible patients who are morbidly obese opt for surgical treatment each year – despite the fact that the safety of bariatric surgery has dramatically improved over the past 15 years. Currently the mortality rate for laparoscopic gastric bypass is at 0.15% (Ann Surg. 2014;259:123-30) and sleeve gastrectomy mortality is lower than that. Only appendectomy has a lower mortality rate among major abdominal operations. Despite the safety record, and despite over a decade of publications demonstrating the effectiveness of bariatric surgery in prolonging life, improving or eliminating comorbid medical problems of obesity, improving the quality of life of patients, and decreasing the cost of their medical care, there still has been no major new shift toward surgery by patients who would benefit from it.

What we are offering is not what these patients want. We as bariatric and metabolic surgeons must face the reality of that fact.

While endoscopic bariatric procedures are not new, their use to date has been limited to modifying existing operations, such as narrowing the anastomosis after gastric bypass for patients who are regaining weight. Such procedures have enjoyed at best mild to moderate short-term success, but poor long-term success.

The performance of a successful endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, however, is a different issue. The sleeve gastrectomy has rapidly become the most popular bariatric operation. Its successful performance endoscopically (Endoscopy. 2015;47:164-6) should serve notice to bariatric surgeons that the time has come to learn to do endoscopic bariatric surgery. If effective, it almost certainly will be what patients seek in the future.

Societal stigmas, patient expectations, and our culture all drive the perception that obesity is a problem that individuals should be able to solve on their own. It is this firmly entrenched belief that is the foundation of the multi-billion dollar diet products industry. Yet the concept of having surgery to treat severe obesity is one that most severely obese patients do not easily embrace. A first-hand successful experience of a friend or relative is often needed for these individuals to consider a surgical procedure. While most patients with ultrasound-proven gallstones who are symptomatic will be referred to a surgeon by their primary care physician, how often is this true for the patient with a body mass index over 35?

The appeal of endoscopic procedures for patients and referring physicians is, of course, that these procedures are perceived as not really surgery. They are minimally invasive endoscopic procedures. The risk profile is very low. Why not consider it? patients may ask themselves. After all, you are not really having surgery.

Many of my bariatric colleagues will likely disagree with this recommendation to embrace endoscopic procedures. After all, the track record to date of many of these procedures and devices has not been impressive. All devices to date that have involved endoscopic treatment of obesity have either failed and been removed from the market, or are in their infancy still looking to establish efficacy (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:507-15). I have been vocally critical at symposia and national meetings of the concept of using an endoscopic suturing device to narrow the anastomosis of patients with a gastric bypass who are regaining weight. I have argued that the procedure is doomed to long-term minimal success or more likely flat-out failure. However, such a conservative approach that demands proof of long-term efficacy could predictably place us conservative curmudgeons on the sidelines of treating obesity when successful endoscopic procedures are available and become the sought-after option, just as laparoscopy became the sought-after option 17 years ago. How many surgeons offered primarily open bariatric operations after about 2005?

If we are to reach more than 1%-2% of the eligible patients who would benefit from treatment for morbid obesity and its related medical problems, then we need to take a different approach. We have about maximized how well we can do the surgical approach we now offer. It isn’t gaining in popularity among those who need it most. While we should not abandon the procedures that have been proven so effective, we should embrace new options for our patients.

It is certainly possible that the stigma of having surgery will resolve if a patient has an endoscopic procedure that is successful but only transiently. A more definitive operative procedure then may follow. Is that not ultimately better for that patient than having him or her never pursue a treatment for obesity? While this argument seems appropriate for the long-term overall patient good, the short-term increase in cost may make it a difficult sell to payers. But insurance companies are already doing their very best not to pay for highly medically effective and proven cost-effective bariatric surgery now. Only public pressure will force them to change – perhaps the public pressure of demand for endoscopic procedures.

Bariatric surgeons: It’s time to become bariatric endoscopists. If we want new patients, we need to adopt new treatments.

Dr. Schirmer is the Stephen H. Watts Professor of Surgery at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville.

How many common bile duct operations have you done lately? How about laparotomies for bleeding duodenal ulcers? How about central venous access catheters? How many procedures that you as a general surgeon may have done a few decades ago are now done primarily by endoscopists, radiologists, or others using minimal access for their procedures?

Now hold that thought, as we turn to the field of bariatric surgery.

Twenty years ago, in 1996, there were approximately 12,000 bariatric operations performed in the United States. From 1998 to 2004, that number increased to almost 136,000 per year (J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:261-6). What was the reason? While other factors likely had some influence, the overwhelming factor was that laparoscopic bariatric surgery became available. Patients perceived this approach as less invasive. Primary care referring physicians did as well.

The rapid rise in laparoscopy boosted the popularity of bariatric surgery but since that bump, the bariatric surgery numbers have remained flat. Currently, less than 2% of eligible patients who are morbidly obese opt for surgical treatment each year – despite the fact that the safety of bariatric surgery has dramatically improved over the past 15 years. Currently the mortality rate for laparoscopic gastric bypass is at 0.15% (Ann Surg. 2014;259:123-30) and sleeve gastrectomy mortality is lower than that. Only appendectomy has a lower mortality rate among major abdominal operations. Despite the safety record, and despite over a decade of publications demonstrating the effectiveness of bariatric surgery in prolonging life, improving or eliminating comorbid medical problems of obesity, improving the quality of life of patients, and decreasing the cost of their medical care, there still has been no major new shift toward surgery by patients who would benefit from it.

What we are offering is not what these patients want. We as bariatric and metabolic surgeons must face the reality of that fact.

While endoscopic bariatric procedures are not new, their use to date has been limited to modifying existing operations, such as narrowing the anastomosis after gastric bypass for patients who are regaining weight. Such procedures have enjoyed at best mild to moderate short-term success, but poor long-term success.

The performance of a successful endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, however, is a different issue. The sleeve gastrectomy has rapidly become the most popular bariatric operation. Its successful performance endoscopically (Endoscopy. 2015;47:164-6) should serve notice to bariatric surgeons that the time has come to learn to do endoscopic bariatric surgery. If effective, it almost certainly will be what patients seek in the future.

Societal stigmas, patient expectations, and our culture all drive the perception that obesity is a problem that individuals should be able to solve on their own. It is this firmly entrenched belief that is the foundation of the multi-billion dollar diet products industry. Yet the concept of having surgery to treat severe obesity is one that most severely obese patients do not easily embrace. A first-hand successful experience of a friend or relative is often needed for these individuals to consider a surgical procedure. While most patients with ultrasound-proven gallstones who are symptomatic will be referred to a surgeon by their primary care physician, how often is this true for the patient with a body mass index over 35?

The appeal of endoscopic procedures for patients and referring physicians is, of course, that these procedures are perceived as not really surgery. They are minimally invasive endoscopic procedures. The risk profile is very low. Why not consider it? patients may ask themselves. After all, you are not really having surgery.

Many of my bariatric colleagues will likely disagree with this recommendation to embrace endoscopic procedures. After all, the track record to date of many of these procedures and devices has not been impressive. All devices to date that have involved endoscopic treatment of obesity have either failed and been removed from the market, or are in their infancy still looking to establish efficacy (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:507-15). I have been vocally critical at symposia and national meetings of the concept of using an endoscopic suturing device to narrow the anastomosis of patients with a gastric bypass who are regaining weight. I have argued that the procedure is doomed to long-term minimal success or more likely flat-out failure. However, such a conservative approach that demands proof of long-term efficacy could predictably place us conservative curmudgeons on the sidelines of treating obesity when successful endoscopic procedures are available and become the sought-after option, just as laparoscopy became the sought-after option 17 years ago. How many surgeons offered primarily open bariatric operations after about 2005?

If we are to reach more than 1%-2% of the eligible patients who would benefit from treatment for morbid obesity and its related medical problems, then we need to take a different approach. We have about maximized how well we can do the surgical approach we now offer. It isn’t gaining in popularity among those who need it most. While we should not abandon the procedures that have been proven so effective, we should embrace new options for our patients.

It is certainly possible that the stigma of having surgery will resolve if a patient has an endoscopic procedure that is successful but only transiently. A more definitive operative procedure then may follow. Is that not ultimately better for that patient than having him or her never pursue a treatment for obesity? While this argument seems appropriate for the long-term overall patient good, the short-term increase in cost may make it a difficult sell to payers. But insurance companies are already doing their very best not to pay for highly medically effective and proven cost-effective bariatric surgery now. Only public pressure will force them to change – perhaps the public pressure of demand for endoscopic procedures.

Bariatric surgeons: It’s time to become bariatric endoscopists. If we want new patients, we need to adopt new treatments.

Dr. Schirmer is the Stephen H. Watts Professor of Surgery at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville.

How many common bile duct operations have you done lately? How about laparotomies for bleeding duodenal ulcers? How about central venous access catheters? How many procedures that you as a general surgeon may have done a few decades ago are now done primarily by endoscopists, radiologists, or others using minimal access for their procedures?

Now hold that thought, as we turn to the field of bariatric surgery.

Twenty years ago, in 1996, there were approximately 12,000 bariatric operations performed in the United States. From 1998 to 2004, that number increased to almost 136,000 per year (J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:261-6). What was the reason? While other factors likely had some influence, the overwhelming factor was that laparoscopic bariatric surgery became available. Patients perceived this approach as less invasive. Primary care referring physicians did as well.

The rapid rise in laparoscopy boosted the popularity of bariatric surgery but since that bump, the bariatric surgery numbers have remained flat. Currently, less than 2% of eligible patients who are morbidly obese opt for surgical treatment each year – despite the fact that the safety of bariatric surgery has dramatically improved over the past 15 years. Currently the mortality rate for laparoscopic gastric bypass is at 0.15% (Ann Surg. 2014;259:123-30) and sleeve gastrectomy mortality is lower than that. Only appendectomy has a lower mortality rate among major abdominal operations. Despite the safety record, and despite over a decade of publications demonstrating the effectiveness of bariatric surgery in prolonging life, improving or eliminating comorbid medical problems of obesity, improving the quality of life of patients, and decreasing the cost of their medical care, there still has been no major new shift toward surgery by patients who would benefit from it.

What we are offering is not what these patients want. We as bariatric and metabolic surgeons must face the reality of that fact.

While endoscopic bariatric procedures are not new, their use to date has been limited to modifying existing operations, such as narrowing the anastomosis after gastric bypass for patients who are regaining weight. Such procedures have enjoyed at best mild to moderate short-term success, but poor long-term success.

The performance of a successful endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, however, is a different issue. The sleeve gastrectomy has rapidly become the most popular bariatric operation. Its successful performance endoscopically (Endoscopy. 2015;47:164-6) should serve notice to bariatric surgeons that the time has come to learn to do endoscopic bariatric surgery. If effective, it almost certainly will be what patients seek in the future.

Societal stigmas, patient expectations, and our culture all drive the perception that obesity is a problem that individuals should be able to solve on their own. It is this firmly entrenched belief that is the foundation of the multi-billion dollar diet products industry. Yet the concept of having surgery to treat severe obesity is one that most severely obese patients do not easily embrace. A first-hand successful experience of a friend or relative is often needed for these individuals to consider a surgical procedure. While most patients with ultrasound-proven gallstones who are symptomatic will be referred to a surgeon by their primary care physician, how often is this true for the patient with a body mass index over 35?

The appeal of endoscopic procedures for patients and referring physicians is, of course, that these procedures are perceived as not really surgery. They are minimally invasive endoscopic procedures. The risk profile is very low. Why not consider it? patients may ask themselves. After all, you are not really having surgery.

Many of my bariatric colleagues will likely disagree with this recommendation to embrace endoscopic procedures. After all, the track record to date of many of these procedures and devices has not been impressive. All devices to date that have involved endoscopic treatment of obesity have either failed and been removed from the market, or are in their infancy still looking to establish efficacy (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:507-15). I have been vocally critical at symposia and national meetings of the concept of using an endoscopic suturing device to narrow the anastomosis of patients with a gastric bypass who are regaining weight. I have argued that the procedure is doomed to long-term minimal success or more likely flat-out failure. However, such a conservative approach that demands proof of long-term efficacy could predictably place us conservative curmudgeons on the sidelines of treating obesity when successful endoscopic procedures are available and become the sought-after option, just as laparoscopy became the sought-after option 17 years ago. How many surgeons offered primarily open bariatric operations after about 2005?

If we are to reach more than 1%-2% of the eligible patients who would benefit from treatment for morbid obesity and its related medical problems, then we need to take a different approach. We have about maximized how well we can do the surgical approach we now offer. It isn’t gaining in popularity among those who need it most. While we should not abandon the procedures that have been proven so effective, we should embrace new options for our patients.

It is certainly possible that the stigma of having surgery will resolve if a patient has an endoscopic procedure that is successful but only transiently. A more definitive operative procedure then may follow. Is that not ultimately better for that patient than having him or her never pursue a treatment for obesity? While this argument seems appropriate for the long-term overall patient good, the short-term increase in cost may make it a difficult sell to payers. But insurance companies are already doing their very best not to pay for highly medically effective and proven cost-effective bariatric surgery now. Only public pressure will force them to change – perhaps the public pressure of demand for endoscopic procedures.

Bariatric surgeons: It’s time to become bariatric endoscopists. If we want new patients, we need to adopt new treatments.

Dr. Schirmer is the Stephen H. Watts Professor of Surgery at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville.

The future of surgery

Predicting the future has been a favorite topic of surgeons through the ages for addresses to august surgical societies.

Confident predictions of the future of surgery, however, have not always stood the test of time. Speaking at the University of Manchester’s Centenary celebration in 1973 at an international symposium on “Medicine in the 21st Century,” the noted surgeon J. Englebert Dunphy correctly predicted the prominence of joint-replacement procedures, but incorrectly asserted that medical advances would virtually eliminate the need for cholecystectomy through dissolution of gallstones and the need for surgical approaches to atherosclerosis through plaque prevention and dissolution. He accurately predicted that infections and sepsis would remain serious problems. But he missed the mark when he predicted that surgical pain would be eliminated by a pill that would block somatic nerve impulses without any respiratory or circulatory effects (Surgery. 1974 Mar;75:332-7). Technologic advances such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which emerged less than 20 years into the future, were not on his radar screen.

Change and disruptive technology

To be sure, the surgical procedures and methods have changed markedly since the time I trained in surgery in the 1970s. The most obvious change is the shift from large incisions to small ones, with the commensurate quick recovery and short hospital stays. This change is primarily because of the emergence of disruptive technology, a concept that has pervaded every avenue of our current lives, not just surgery: Think Uber, robotics in industry, the Internet, smartphones, and the miniaturization of just about every communication means. In medicine, these disruptive technologies have led to the emergence of the electronic health record, new imaging modalities, percutaneous interventional techniques, fiber optic endoscopy, laparoscopy, and endovascular surgery.

Maintaining capacity to do infrequent operations

During my training, H2 receptor antagonists and Helicobacter pylori came on the scene, with the result that ulcer operations almost disappeared from our surgical armamentarium; one of my most frequent operations as a senior and chief resident has become a rarity 40 years later for our trainees. And yet, a general surgeon must know how to perform an ulcer operation and which type is the best for a given circumstance, since perforated and bleeding ulcers are still seen, if infrequently. The perforated ulcer is seen most often in patients with multiple comorbidities who can least tolerate a complication and need one effective and well-executed operation if they are going to survive. How do we continue to teach residents these procedures when they have become infrequent?

There is perhaps some utility in keeping some aging surgeons around to teach residents on fresh cadavers, or to call them out of their assisted living facilities when needed for consultation! Now that the majority of operations in most places are being performed by minimally invasive surgical (MIS) methods, we may not need MIS fellowships or training much longer for trainees to become proficient in these skills, because it is the open operations that are less frequent. Our chief residents are much less secure about performing an open cholecystectomy, of which they have performed perhaps 5, than they are about performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, of which they have performed 105.

Technologies on the verge of disrupting

Mark Aeder, MD, FACS, recently asked an important question in the ACS Communities thread on the future of surgery: What will the future disruptive innovations be? Which areas of surgery will bloom next?

There are many game-changing emerging technologies that could well turn out to be future “disruptors” of surgery as we know it. Cancer surgery is on track to be transformed by the development of genomics and personalized medicine and immunotherapy for melanoma and lung cancer.

The areas most likely to remain in the surgical realm are trauma, infections, and inflammation. Though safer cars, seatbelt laws, and helmet laws for motorcyclists have already decreased motor vehicle accidents and injury severity, we have still not produced a cure for stupidity or bad luck. Traumatic injuries will always be with us, and surgeons well trained in trauma management will continue to be needed. Appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis will continue to require operations, even though inroads have begun with the studies showing success of antibiotic treatment for appendicitis and diverticulitis.

Keep current, avoid bandwagons

The key lesson, not only for our young surgeons-in-training but also for our seasoned surgeons, is to keep learning, keep networking, and keep adopting new techniques as soon as they show true evidence of success.

The best way for surgeons to remain prepared for whatever the future will bring is to stay current with innovations coming on the scene but not jump on the bandwagon too early and adopt new fads without substantial evidence of their soundness. A few retrospective case series reporting success with a new operation is insufficient evidence to try it out on the unsuspecting public. Although the completion of well-designed randomized trials with adequate follow-up takes time, it is better to stick with well-established and evidence-based techniques than rush to embrace an inadequately vetted procedure that may end up harming a patient.

Not all innovative devices or procedures rise to the level of being so truly “experimental” that they would require an institutional review board, and this ought to prompt an extra measure of caution by surgeons. Some “innovations,” such as the endobariatric devices reported elsewhere in this issue, represent novel variations of previous procedures but are as yet unvalidated by long-term studies. Responsible adoption of these novel procedures requires a full disclosure to the patient that the procedure or device is novel, without long-term evidence of success, and may entail unknown risks. Don’t let your enthusiasm to be an early adopter overcome your scientific and historic obligation to prevent harm to the patient.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Predicting the future has been a favorite topic of surgeons through the ages for addresses to august surgical societies.

Confident predictions of the future of surgery, however, have not always stood the test of time. Speaking at the University of Manchester’s Centenary celebration in 1973 at an international symposium on “Medicine in the 21st Century,” the noted surgeon J. Englebert Dunphy correctly predicted the prominence of joint-replacement procedures, but incorrectly asserted that medical advances would virtually eliminate the need for cholecystectomy through dissolution of gallstones and the need for surgical approaches to atherosclerosis through plaque prevention and dissolution. He accurately predicted that infections and sepsis would remain serious problems. But he missed the mark when he predicted that surgical pain would be eliminated by a pill that would block somatic nerve impulses without any respiratory or circulatory effects (Surgery. 1974 Mar;75:332-7). Technologic advances such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which emerged less than 20 years into the future, were not on his radar screen.

Change and disruptive technology

To be sure, the surgical procedures and methods have changed markedly since the time I trained in surgery in the 1970s. The most obvious change is the shift from large incisions to small ones, with the commensurate quick recovery and short hospital stays. This change is primarily because of the emergence of disruptive technology, a concept that has pervaded every avenue of our current lives, not just surgery: Think Uber, robotics in industry, the Internet, smartphones, and the miniaturization of just about every communication means. In medicine, these disruptive technologies have led to the emergence of the electronic health record, new imaging modalities, percutaneous interventional techniques, fiber optic endoscopy, laparoscopy, and endovascular surgery.

Maintaining capacity to do infrequent operations

During my training, H2 receptor antagonists and Helicobacter pylori came on the scene, with the result that ulcer operations almost disappeared from our surgical armamentarium; one of my most frequent operations as a senior and chief resident has become a rarity 40 years later for our trainees. And yet, a general surgeon must know how to perform an ulcer operation and which type is the best for a given circumstance, since perforated and bleeding ulcers are still seen, if infrequently. The perforated ulcer is seen most often in patients with multiple comorbidities who can least tolerate a complication and need one effective and well-executed operation if they are going to survive. How do we continue to teach residents these procedures when they have become infrequent?

There is perhaps some utility in keeping some aging surgeons around to teach residents on fresh cadavers, or to call them out of their assisted living facilities when needed for consultation! Now that the majority of operations in most places are being performed by minimally invasive surgical (MIS) methods, we may not need MIS fellowships or training much longer for trainees to become proficient in these skills, because it is the open operations that are less frequent. Our chief residents are much less secure about performing an open cholecystectomy, of which they have performed perhaps 5, than they are about performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, of which they have performed 105.

Technologies on the verge of disrupting

Mark Aeder, MD, FACS, recently asked an important question in the ACS Communities thread on the future of surgery: What will the future disruptive innovations be? Which areas of surgery will bloom next?

There are many game-changing emerging technologies that could well turn out to be future “disruptors” of surgery as we know it. Cancer surgery is on track to be transformed by the development of genomics and personalized medicine and immunotherapy for melanoma and lung cancer.

The areas most likely to remain in the surgical realm are trauma, infections, and inflammation. Though safer cars, seatbelt laws, and helmet laws for motorcyclists have already decreased motor vehicle accidents and injury severity, we have still not produced a cure for stupidity or bad luck. Traumatic injuries will always be with us, and surgeons well trained in trauma management will continue to be needed. Appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis will continue to require operations, even though inroads have begun with the studies showing success of antibiotic treatment for appendicitis and diverticulitis.

Keep current, avoid bandwagons

The key lesson, not only for our young surgeons-in-training but also for our seasoned surgeons, is to keep learning, keep networking, and keep adopting new techniques as soon as they show true evidence of success.

The best way for surgeons to remain prepared for whatever the future will bring is to stay current with innovations coming on the scene but not jump on the bandwagon too early and adopt new fads without substantial evidence of their soundness. A few retrospective case series reporting success with a new operation is insufficient evidence to try it out on the unsuspecting public. Although the completion of well-designed randomized trials with adequate follow-up takes time, it is better to stick with well-established and evidence-based techniques than rush to embrace an inadequately vetted procedure that may end up harming a patient.

Not all innovative devices or procedures rise to the level of being so truly “experimental” that they would require an institutional review board, and this ought to prompt an extra measure of caution by surgeons. Some “innovations,” such as the endobariatric devices reported elsewhere in this issue, represent novel variations of previous procedures but are as yet unvalidated by long-term studies. Responsible adoption of these novel procedures requires a full disclosure to the patient that the procedure or device is novel, without long-term evidence of success, and may entail unknown risks. Don’t let your enthusiasm to be an early adopter overcome your scientific and historic obligation to prevent harm to the patient.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Predicting the future has been a favorite topic of surgeons through the ages for addresses to august surgical societies.

Confident predictions of the future of surgery, however, have not always stood the test of time. Speaking at the University of Manchester’s Centenary celebration in 1973 at an international symposium on “Medicine in the 21st Century,” the noted surgeon J. Englebert Dunphy correctly predicted the prominence of joint-replacement procedures, but incorrectly asserted that medical advances would virtually eliminate the need for cholecystectomy through dissolution of gallstones and the need for surgical approaches to atherosclerosis through plaque prevention and dissolution. He accurately predicted that infections and sepsis would remain serious problems. But he missed the mark when he predicted that surgical pain would be eliminated by a pill that would block somatic nerve impulses without any respiratory or circulatory effects (Surgery. 1974 Mar;75:332-7). Technologic advances such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which emerged less than 20 years into the future, were not on his radar screen.

Change and disruptive technology

To be sure, the surgical procedures and methods have changed markedly since the time I trained in surgery in the 1970s. The most obvious change is the shift from large incisions to small ones, with the commensurate quick recovery and short hospital stays. This change is primarily because of the emergence of disruptive technology, a concept that has pervaded every avenue of our current lives, not just surgery: Think Uber, robotics in industry, the Internet, smartphones, and the miniaturization of just about every communication means. In medicine, these disruptive technologies have led to the emergence of the electronic health record, new imaging modalities, percutaneous interventional techniques, fiber optic endoscopy, laparoscopy, and endovascular surgery.

Maintaining capacity to do infrequent operations

During my training, H2 receptor antagonists and Helicobacter pylori came on the scene, with the result that ulcer operations almost disappeared from our surgical armamentarium; one of my most frequent operations as a senior and chief resident has become a rarity 40 years later for our trainees. And yet, a general surgeon must know how to perform an ulcer operation and which type is the best for a given circumstance, since perforated and bleeding ulcers are still seen, if infrequently. The perforated ulcer is seen most often in patients with multiple comorbidities who can least tolerate a complication and need one effective and well-executed operation if they are going to survive. How do we continue to teach residents these procedures when they have become infrequent?

There is perhaps some utility in keeping some aging surgeons around to teach residents on fresh cadavers, or to call them out of their assisted living facilities when needed for consultation! Now that the majority of operations in most places are being performed by minimally invasive surgical (MIS) methods, we may not need MIS fellowships or training much longer for trainees to become proficient in these skills, because it is the open operations that are less frequent. Our chief residents are much less secure about performing an open cholecystectomy, of which they have performed perhaps 5, than they are about performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, of which they have performed 105.

Technologies on the verge of disrupting

Mark Aeder, MD, FACS, recently asked an important question in the ACS Communities thread on the future of surgery: What will the future disruptive innovations be? Which areas of surgery will bloom next?

There are many game-changing emerging technologies that could well turn out to be future “disruptors” of surgery as we know it. Cancer surgery is on track to be transformed by the development of genomics and personalized medicine and immunotherapy for melanoma and lung cancer.

The areas most likely to remain in the surgical realm are trauma, infections, and inflammation. Though safer cars, seatbelt laws, and helmet laws for motorcyclists have already decreased motor vehicle accidents and injury severity, we have still not produced a cure for stupidity or bad luck. Traumatic injuries will always be with us, and surgeons well trained in trauma management will continue to be needed. Appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis will continue to require operations, even though inroads have begun with the studies showing success of antibiotic treatment for appendicitis and diverticulitis.

Keep current, avoid bandwagons

The key lesson, not only for our young surgeons-in-training but also for our seasoned surgeons, is to keep learning, keep networking, and keep adopting new techniques as soon as they show true evidence of success.

The best way for surgeons to remain prepared for whatever the future will bring is to stay current with innovations coming on the scene but not jump on the bandwagon too early and adopt new fads without substantial evidence of their soundness. A few retrospective case series reporting success with a new operation is insufficient evidence to try it out on the unsuspecting public. Although the completion of well-designed randomized trials with adequate follow-up takes time, it is better to stick with well-established and evidence-based techniques than rush to embrace an inadequately vetted procedure that may end up harming a patient.

Not all innovative devices or procedures rise to the level of being so truly “experimental” that they would require an institutional review board, and this ought to prompt an extra measure of caution by surgeons. Some “innovations,” such as the endobariatric devices reported elsewhere in this issue, represent novel variations of previous procedures but are as yet unvalidated by long-term studies. Responsible adoption of these novel procedures requires a full disclosure to the patient that the procedure or device is novel, without long-term evidence of success, and may entail unknown risks. Don’t let your enthusiasm to be an early adopter overcome your scientific and historic obligation to prevent harm to the patient.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Coming your way ... MIPS

In this column, I will return to the topic of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new payment program, currently scheduled to go into effect January 2017. The QPP has two tracks, the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Again, it is widely expected that for the first several years of the program, the vast majority of surgeons will participate in the QPP via the MIPS track.

To briefly review from the July edition of this column, MIPS consists of four components:

1) Quality.

2) Resource Use.

3) Advancing Care Information (ACI).

4) Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA).

The Quality component replaces the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Resource Use component replaces the Value-Based Modifier (VBM), the Advancing Care Information (ACI) component replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program and is proposed to simplify the program by modifying requirements. The fourth component of MIPS, the Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA), is new.

MIPS participants will be assigned a Composite Performance Score based on their performance in all four components. As proposed for 2017, 50% of the MIPS Composite Performance Score will be based on performance in the Quality component, 25% will be based on the ACI component, 15% will be based on the CPIA, and 10% will be based on Resource Use. Thus, 75% of one’s score will be determined by performance in the Quality and ACI components. With that in mind, the remainder of this month’s column will be dedicated to the ACI with next month’s column focusing on the Quality component.

The Advancing Care Component (ACI)

As discussed above, the ACI component modifies and replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. As currently proposed, (and subject to change with release of the final rule in early November 2016), the score for ACI will be derived in two parts: a base score (50 points) and a performance score.

The threshold for achieving the base score remains an “all or nothing” proposition. Achieving the threshold is based upon reporting a yes/no statement OR the appropriate numerator and denominator for each measure, as required, for the following six objectives:

1) Protect Patient Health Information.

2) Electronic Prescribing.

3) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

4) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

5) Health Information Exchange.

6) Public Health and Clinical Data Reporting.

Only after meeting the requirements for the base score is one eligible to receive additional performance score credit based on the level of performance on a subset of three of the objectives required to achieve the base score. Those three are:

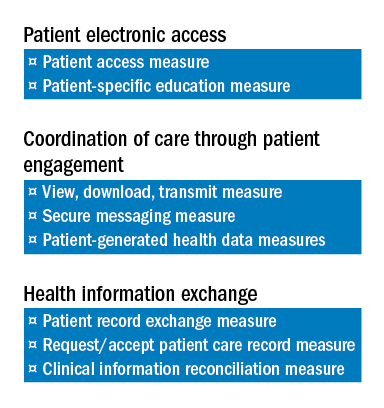

1) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

2) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

3) Health Information Exchange

There are a total of eight measures for these three objectives.

The two measures specific to the Patient Electronic Access objective are:

a) Patient Access Measure.

b) Patient-Specific Education Measure.

Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement is assessed based upon the following three measures:

a) View, Download, Transmit Measure.

b) Secure Messaging Measure.

c) Patient-Generated Health Data Measures.

For the Health Information Exchange objective, assessment is also based on three measures. They are:

a) Patient Record Exchange Measure.

b) Request/Accept Patient Care Record Measure.

c) Clinical Information Reconciliation Measure.

Scoring for each of these eight measures is based upon reporting both a numerator and denominator, thus facilitating the calculation of percentage score to which a point value is assigned. For example, a performance rate of 85 on one of the listed measures would earn 8.5 points toward the performance score. The sum of the points accumulated for these eight measures is added to Threshold Score to determine the final score for ACI. Again, 25% of one’s MIPS Composite Score is derived from performance in the ACI component.

It warrants repeating and re-emphasis that the above information is subject to modification pending the release of the MIPS Final Rule, expected in early November.

As mentioned above, the Quality component of MIPS replaces the PQRS. Quality assessment will comprise 50% of the MIPS Composite Score. In next month’s column, I will provide an outline of the changes CMS is proposing for the Quality assessment. As a preview, some good news can be found in the fact that the current MIPS Quality component proposal will require providers to report on a total of six measures as opposed to the previous PQRS requirement to report on nine.

Until next month …

In this column, I will return to the topic of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new payment program, currently scheduled to go into effect January 2017. The QPP has two tracks, the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Again, it is widely expected that for the first several years of the program, the vast majority of surgeons will participate in the QPP via the MIPS track.

To briefly review from the July edition of this column, MIPS consists of four components:

1) Quality.

2) Resource Use.

3) Advancing Care Information (ACI).

4) Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA).

The Quality component replaces the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Resource Use component replaces the Value-Based Modifier (VBM), the Advancing Care Information (ACI) component replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program and is proposed to simplify the program by modifying requirements. The fourth component of MIPS, the Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA), is new.

MIPS participants will be assigned a Composite Performance Score based on their performance in all four components. As proposed for 2017, 50% of the MIPS Composite Performance Score will be based on performance in the Quality component, 25% will be based on the ACI component, 15% will be based on the CPIA, and 10% will be based on Resource Use. Thus, 75% of one’s score will be determined by performance in the Quality and ACI components. With that in mind, the remainder of this month’s column will be dedicated to the ACI with next month’s column focusing on the Quality component.

The Advancing Care Component (ACI)

As discussed above, the ACI component modifies and replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. As currently proposed, (and subject to change with release of the final rule in early November 2016), the score for ACI will be derived in two parts: a base score (50 points) and a performance score.

The threshold for achieving the base score remains an “all or nothing” proposition. Achieving the threshold is based upon reporting a yes/no statement OR the appropriate numerator and denominator for each measure, as required, for the following six objectives:

1) Protect Patient Health Information.

2) Electronic Prescribing.

3) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

4) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

5) Health Information Exchange.

6) Public Health and Clinical Data Reporting.

Only after meeting the requirements for the base score is one eligible to receive additional performance score credit based on the level of performance on a subset of three of the objectives required to achieve the base score. Those three are:

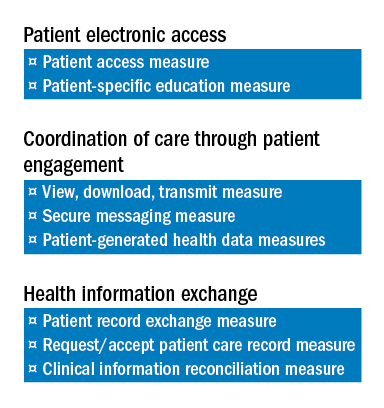

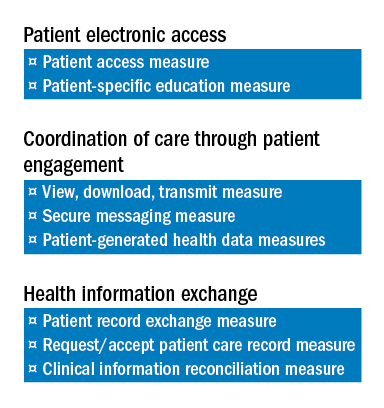

1) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

2) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

3) Health Information Exchange

There are a total of eight measures for these three objectives.

The two measures specific to the Patient Electronic Access objective are:

a) Patient Access Measure.

b) Patient-Specific Education Measure.

Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement is assessed based upon the following three measures:

a) View, Download, Transmit Measure.

b) Secure Messaging Measure.

c) Patient-Generated Health Data Measures.

For the Health Information Exchange objective, assessment is also based on three measures. They are:

a) Patient Record Exchange Measure.

b) Request/Accept Patient Care Record Measure.

c) Clinical Information Reconciliation Measure.

Scoring for each of these eight measures is based upon reporting both a numerator and denominator, thus facilitating the calculation of percentage score to which a point value is assigned. For example, a performance rate of 85 on one of the listed measures would earn 8.5 points toward the performance score. The sum of the points accumulated for these eight measures is added to Threshold Score to determine the final score for ACI. Again, 25% of one’s MIPS Composite Score is derived from performance in the ACI component.