User login

Age-Friendly Health Systems and Meeting the Principles of High Reliability Organizations in the VHA

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

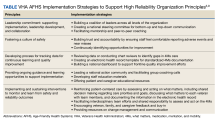

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

Perinatal Psychiatry in 2024: Helping More Patients Access Care

The past year has been a challenging time for many, both at the local level and globally, with divisive undercurrents across many communities. Many times, the end of the year is an opportunity for reflection. As I reflect on the state of perinatal psychiatry in the new year, I see several evolving issues that I’d like to share in this first column of 2024.

In 2023, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published new recommendations meant to enhance the well-being of pregnant and postpartum women and families. A main message from discussion papers borne out of these recommendations was that as a field, we should be doing more than identifying perinatal illness. We should be screening women at risk for postpartum psychiatric illness and see that those suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have access to care and “wrap-around services” from clinicians with varying expertise.

Screening is a primary way we identify patients at risk for psychiatric illness and also those who are suffering at the time of a screen. One problem I see in the near future is our disparate collection and management of data. When we look closely across health care systems, it’s not clear how screening data are captured, let alone managed. What is being done in one hospital system may be very different from what is being done elsewhere. Some clinicians are adopting digital platforms to identify those with postpartum depression, while others are practicing as they always have, either through a paper screening process or with queries as part of a clinical encounter.

Given this amalgam of methods for collecting and storing information, there does not appear to be a systematic way clinicians and researchers are recording whether women are meeting criteria for significant depressive symptoms or frank postpartum psychiatric illness. It is clear a more cohesive method for collection and management is needed to optimize the likelihood that next steps can be taken to get patients the care they need.

However, screening is only one part of the story. Certainly, in our own center, one of our greatest interests, both clinically and on the research side, is what happens after screening. Through our center’s initiation of the Screening and Treatment Enhancement for Postpartum Depression (STEPS for PPD) project funded by the Marriott Foundation, we are evaluating the outcomes of women who are screened at 6 weeks postpartum with significant depressive symptoms, and who are then given an opportunity to engage with a perinatal social worker who can assist with direct psychotherapy, arranging for referrals, and navigating care for a new mother.

What we are learning as we enroll women through the initial stages of STEPS for PPD is that screening and identifying women who likely suffer from PPD simply is not enough. In fact, once identified with a depression screening tool, women who are suffering from postpartum depression can be very challenging to engage clinically. What I am learning decades after starting to work with perinatal patients is that even with a screening system and effective tools for treatment of PPD, optimizing engagement with these depressed women seems a critical and understudied step on the road to optimizing positive clinical outcomes.

A recent study published in the Journal of Women’s Health explored gaps in care for perinatal depression and found that patients without a history of psychiatric illness prior to pregnancy were less likely to be screened for depression and 80% less likely to receive care if they developed depression compared with women with a previous history of psychiatric illness (J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2023 Oct;32[10]:1111-9).

That history may help women navigate to care, while women for whom psychiatric illness is a new experience may be less likely to engage, be referred for care, and receive appropriate treatment. The study indicates that, as a field, we must strive to ensure universal screening for depression in perinatal populations.

While we have always been particularly interested in populations of patients at highest risk for PPD, helping women at risk for PPD in the general population without a history of psychiatric illness is a large public health issue and will be an even larger undertaking. As women’s mental health is gaining more appropriate focus, both at the local level and even in the recent White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, the focus has been on screening and developing new treatments.

We are not lacking in pharmacologic agents nor nonpharmacologic options as treatments for women experiencing PPD. Newer alternative treatments are being explored, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and even psychedelics as a potential therapy for PPD. But perhaps what we’ve learned in 2023 and as we move into a new year, is that the problem of tackling PPD is not only about having the right tools, but is about helping women navigate to the care that they need.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it an explosion of telehealth options that have enhanced the odds women can find support during such a challenging time; as society has returned to some semblance of normal, nearly all support groups for postpartum women have remained online.

When we set up Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health at the beginning of the pandemic, I was struck by the community of colleagues at various stages of their careers dedicated to mitigating the suffering associated with perinatal psychiatric illness. As I’ve often said, it takes a village to care for these patients. We need help from colleagues with varying expertise — from lactation consultants, psychiatrists, psychologists, obstetricians, nurse practitioners, support group leaders, and a host of others — who can help reach these women.

At the end of the day, helping depressed women find resources is a challenge that we have not met in this country. We should be excited that we have so many treatment options to offer patients — whether it be a new first-in-class medication, TMS, or digital apps to ensure patients are receiving effective treatment. But there should also be a focus on reaching women who still need treatment, particularly in underserved communities where resources are sparse or nonexistent. Identifying the path to reaching these women where they are and getting them well should be a top priority in 2024.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. STEPS for PPD is funded by the Marriott Foundation. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The past year has been a challenging time for many, both at the local level and globally, with divisive undercurrents across many communities. Many times, the end of the year is an opportunity for reflection. As I reflect on the state of perinatal psychiatry in the new year, I see several evolving issues that I’d like to share in this first column of 2024.

In 2023, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published new recommendations meant to enhance the well-being of pregnant and postpartum women and families. A main message from discussion papers borne out of these recommendations was that as a field, we should be doing more than identifying perinatal illness. We should be screening women at risk for postpartum psychiatric illness and see that those suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have access to care and “wrap-around services” from clinicians with varying expertise.

Screening is a primary way we identify patients at risk for psychiatric illness and also those who are suffering at the time of a screen. One problem I see in the near future is our disparate collection and management of data. When we look closely across health care systems, it’s not clear how screening data are captured, let alone managed. What is being done in one hospital system may be very different from what is being done elsewhere. Some clinicians are adopting digital platforms to identify those with postpartum depression, while others are practicing as they always have, either through a paper screening process or with queries as part of a clinical encounter.

Given this amalgam of methods for collecting and storing information, there does not appear to be a systematic way clinicians and researchers are recording whether women are meeting criteria for significant depressive symptoms or frank postpartum psychiatric illness. It is clear a more cohesive method for collection and management is needed to optimize the likelihood that next steps can be taken to get patients the care they need.

However, screening is only one part of the story. Certainly, in our own center, one of our greatest interests, both clinically and on the research side, is what happens after screening. Through our center’s initiation of the Screening and Treatment Enhancement for Postpartum Depression (STEPS for PPD) project funded by the Marriott Foundation, we are evaluating the outcomes of women who are screened at 6 weeks postpartum with significant depressive symptoms, and who are then given an opportunity to engage with a perinatal social worker who can assist with direct psychotherapy, arranging for referrals, and navigating care for a new mother.

What we are learning as we enroll women through the initial stages of STEPS for PPD is that screening and identifying women who likely suffer from PPD simply is not enough. In fact, once identified with a depression screening tool, women who are suffering from postpartum depression can be very challenging to engage clinically. What I am learning decades after starting to work with perinatal patients is that even with a screening system and effective tools for treatment of PPD, optimizing engagement with these depressed women seems a critical and understudied step on the road to optimizing positive clinical outcomes.

A recent study published in the Journal of Women’s Health explored gaps in care for perinatal depression and found that patients without a history of psychiatric illness prior to pregnancy were less likely to be screened for depression and 80% less likely to receive care if they developed depression compared with women with a previous history of psychiatric illness (J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2023 Oct;32[10]:1111-9).

That history may help women navigate to care, while women for whom psychiatric illness is a new experience may be less likely to engage, be referred for care, and receive appropriate treatment. The study indicates that, as a field, we must strive to ensure universal screening for depression in perinatal populations.

While we have always been particularly interested in populations of patients at highest risk for PPD, helping women at risk for PPD in the general population without a history of psychiatric illness is a large public health issue and will be an even larger undertaking. As women’s mental health is gaining more appropriate focus, both at the local level and even in the recent White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, the focus has been on screening and developing new treatments.

We are not lacking in pharmacologic agents nor nonpharmacologic options as treatments for women experiencing PPD. Newer alternative treatments are being explored, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and even psychedelics as a potential therapy for PPD. But perhaps what we’ve learned in 2023 and as we move into a new year, is that the problem of tackling PPD is not only about having the right tools, but is about helping women navigate to the care that they need.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it an explosion of telehealth options that have enhanced the odds women can find support during such a challenging time; as society has returned to some semblance of normal, nearly all support groups for postpartum women have remained online.

When we set up Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health at the beginning of the pandemic, I was struck by the community of colleagues at various stages of their careers dedicated to mitigating the suffering associated with perinatal psychiatric illness. As I’ve often said, it takes a village to care for these patients. We need help from colleagues with varying expertise — from lactation consultants, psychiatrists, psychologists, obstetricians, nurse practitioners, support group leaders, and a host of others — who can help reach these women.

At the end of the day, helping depressed women find resources is a challenge that we have not met in this country. We should be excited that we have so many treatment options to offer patients — whether it be a new first-in-class medication, TMS, or digital apps to ensure patients are receiving effective treatment. But there should also be a focus on reaching women who still need treatment, particularly in underserved communities where resources are sparse or nonexistent. Identifying the path to reaching these women where they are and getting them well should be a top priority in 2024.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. STEPS for PPD is funded by the Marriott Foundation. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The past year has been a challenging time for many, both at the local level and globally, with divisive undercurrents across many communities. Many times, the end of the year is an opportunity for reflection. As I reflect on the state of perinatal psychiatry in the new year, I see several evolving issues that I’d like to share in this first column of 2024.

In 2023, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published new recommendations meant to enhance the well-being of pregnant and postpartum women and families. A main message from discussion papers borne out of these recommendations was that as a field, we should be doing more than identifying perinatal illness. We should be screening women at risk for postpartum psychiatric illness and see that those suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have access to care and “wrap-around services” from clinicians with varying expertise.

Screening is a primary way we identify patients at risk for psychiatric illness and also those who are suffering at the time of a screen. One problem I see in the near future is our disparate collection and management of data. When we look closely across health care systems, it’s not clear how screening data are captured, let alone managed. What is being done in one hospital system may be very different from what is being done elsewhere. Some clinicians are adopting digital platforms to identify those with postpartum depression, while others are practicing as they always have, either through a paper screening process or with queries as part of a clinical encounter.

Given this amalgam of methods for collecting and storing information, there does not appear to be a systematic way clinicians and researchers are recording whether women are meeting criteria for significant depressive symptoms or frank postpartum psychiatric illness. It is clear a more cohesive method for collection and management is needed to optimize the likelihood that next steps can be taken to get patients the care they need.

However, screening is only one part of the story. Certainly, in our own center, one of our greatest interests, both clinically and on the research side, is what happens after screening. Through our center’s initiation of the Screening and Treatment Enhancement for Postpartum Depression (STEPS for PPD) project funded by the Marriott Foundation, we are evaluating the outcomes of women who are screened at 6 weeks postpartum with significant depressive symptoms, and who are then given an opportunity to engage with a perinatal social worker who can assist with direct psychotherapy, arranging for referrals, and navigating care for a new mother.

What we are learning as we enroll women through the initial stages of STEPS for PPD is that screening and identifying women who likely suffer from PPD simply is not enough. In fact, once identified with a depression screening tool, women who are suffering from postpartum depression can be very challenging to engage clinically. What I am learning decades after starting to work with perinatal patients is that even with a screening system and effective tools for treatment of PPD, optimizing engagement with these depressed women seems a critical and understudied step on the road to optimizing positive clinical outcomes.

A recent study published in the Journal of Women’s Health explored gaps in care for perinatal depression and found that patients without a history of psychiatric illness prior to pregnancy were less likely to be screened for depression and 80% less likely to receive care if they developed depression compared with women with a previous history of psychiatric illness (J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2023 Oct;32[10]:1111-9).

That history may help women navigate to care, while women for whom psychiatric illness is a new experience may be less likely to engage, be referred for care, and receive appropriate treatment. The study indicates that, as a field, we must strive to ensure universal screening for depression in perinatal populations.

While we have always been particularly interested in populations of patients at highest risk for PPD, helping women at risk for PPD in the general population without a history of psychiatric illness is a large public health issue and will be an even larger undertaking. As women’s mental health is gaining more appropriate focus, both at the local level and even in the recent White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, the focus has been on screening and developing new treatments.

We are not lacking in pharmacologic agents nor nonpharmacologic options as treatments for women experiencing PPD. Newer alternative treatments are being explored, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and even psychedelics as a potential therapy for PPD. But perhaps what we’ve learned in 2023 and as we move into a new year, is that the problem of tackling PPD is not only about having the right tools, but is about helping women navigate to the care that they need.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it an explosion of telehealth options that have enhanced the odds women can find support during such a challenging time; as society has returned to some semblance of normal, nearly all support groups for postpartum women have remained online.

When we set up Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health at the beginning of the pandemic, I was struck by the community of colleagues at various stages of their careers dedicated to mitigating the suffering associated with perinatal psychiatric illness. As I’ve often said, it takes a village to care for these patients. We need help from colleagues with varying expertise — from lactation consultants, psychiatrists, psychologists, obstetricians, nurse practitioners, support group leaders, and a host of others — who can help reach these women.

At the end of the day, helping depressed women find resources is a challenge that we have not met in this country. We should be excited that we have so many treatment options to offer patients — whether it be a new first-in-class medication, TMS, or digital apps to ensure patients are receiving effective treatment. But there should also be a focus on reaching women who still need treatment, particularly in underserved communities where resources are sparse or nonexistent. Identifying the path to reaching these women where they are and getting them well should be a top priority in 2024.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. STEPS for PPD is funded by the Marriott Foundation. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Nasal Tanning Sprays: Illuminating the Risks of a Popular TikTok Trend

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

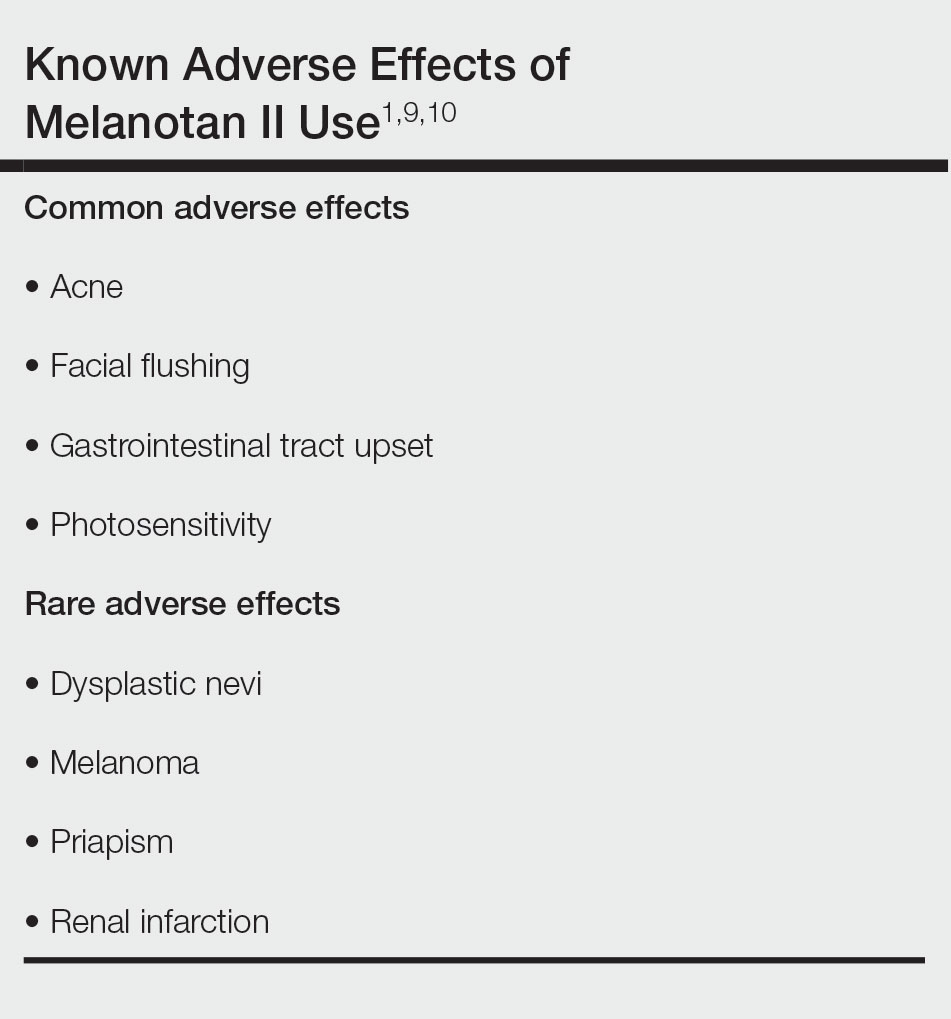

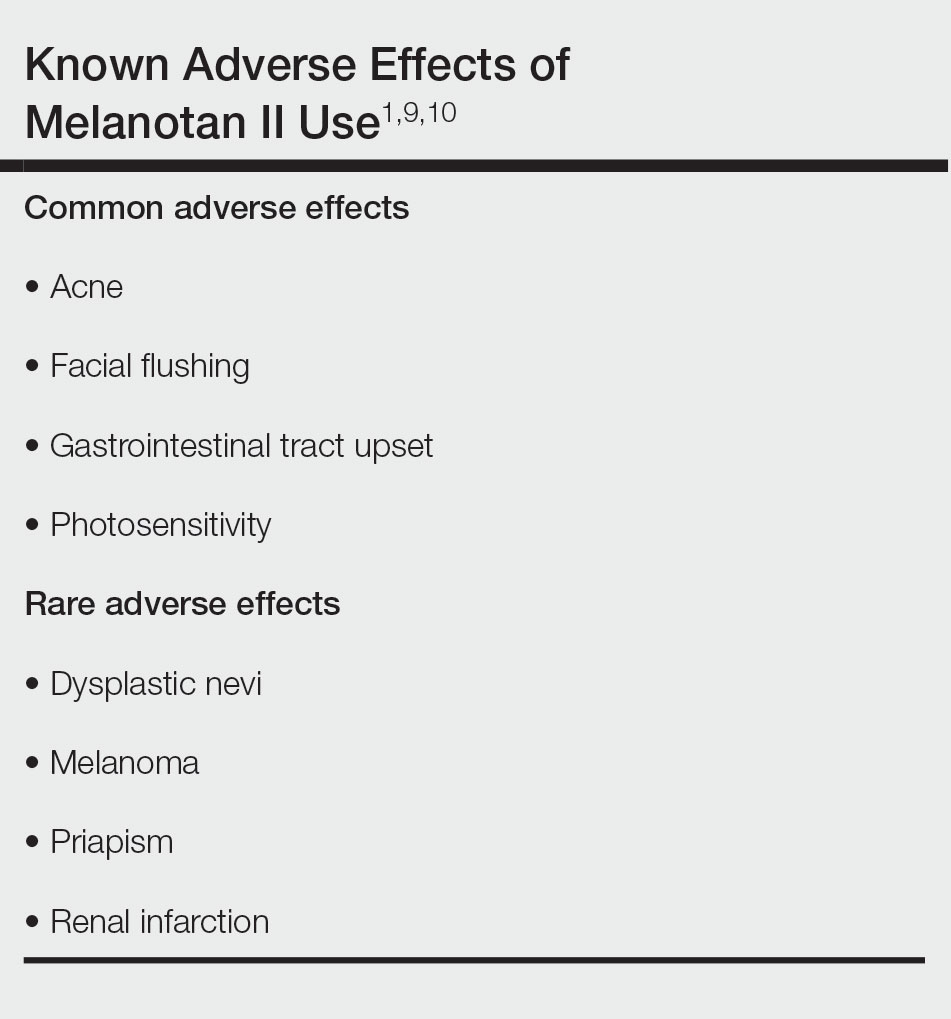

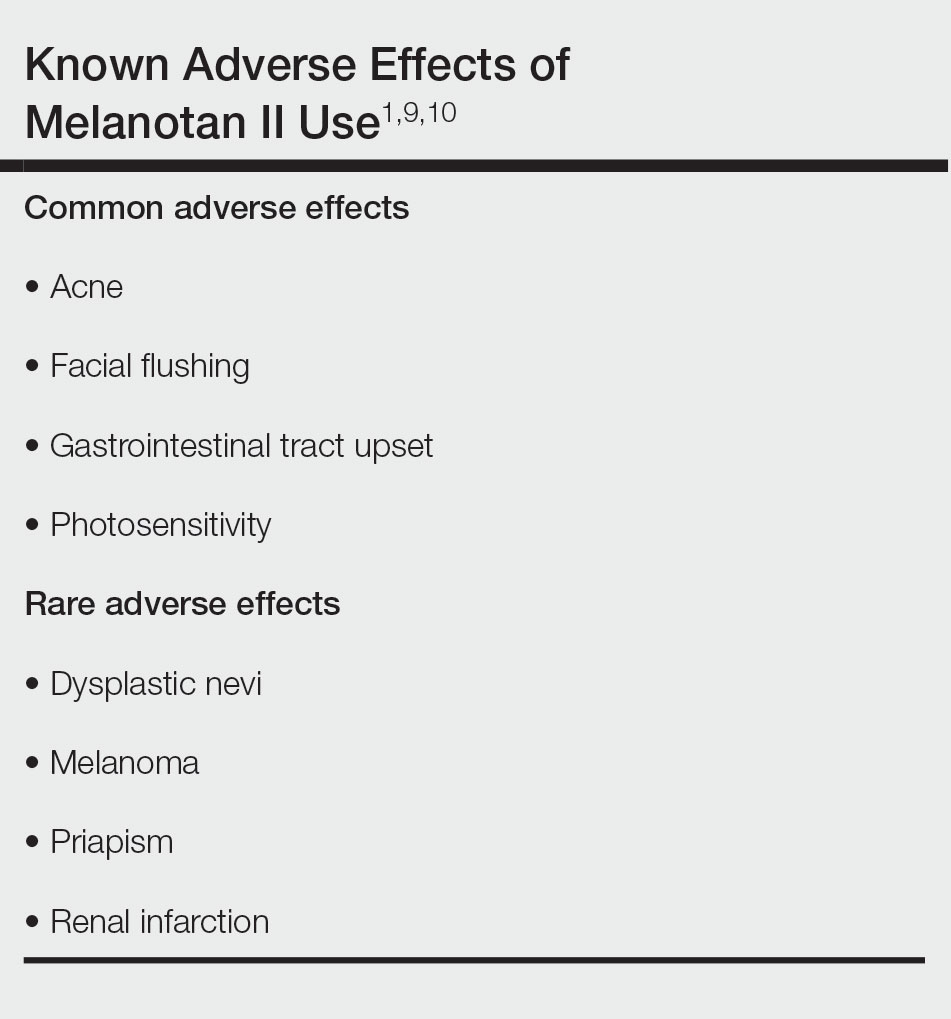

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.