User login

‘Stop Teaching’ Children It’s Their Fault They’re Fat

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has published draft recommendations that 6-year-olds with obesity be lectured to about diet and exercise.

Never mind that there are no reproducible or scalable studies demonstrating durable and clinically meaningful benefits of this for adults let alone children. Never mind that children are not household decision-makers on matters of grocery shopping, cooking, or exercise. Never mind the corollary that many children so lectured who fail to see an impact on their weight will perceive that as their own personal failures. And of course, never mind that we’re privileged to be in an era with safe, effective, pharmacotherapeutic options for obesity. No. We must teach children it’s their fault if they’re fat. Because ultimately that’s what many of them will learn.

That’s not to say there’s no room for counseling. But with children as young as 6, that counseling should be delivered exclusively to their parents and caregivers. That counseling should focus as much if not more so on the impact of weight bias and the biological basis of obesity rather than diet and exercise, while explicitly teaching parents the means to discuss nutrition without risking their children feeling worse about themselves, increasing the risk for conflict over changes, or heightening their children’s chance of developing eating disorders or maladaptive relationships with food.

But back to the USPSTF’s actual recommendation for those 6 years old and up. They’re recommending “at least” 26 hours of lectures over a year-long interprofessional intervention. Putting aside the reality that this isn’t scalable time-wise or cost-wise to reach even a fraction of the roughly 15 million US children with obesity, there is also the issue of service provision. Because when it comes to obesity, if the intervention is purely educational, even if you want to believe there is a syllabus out there that would have a dramatic impact, its impact will vary wildly depending on the skill and approach of the service providers. This inconvenient truth is also the one that makes it impossible to meaningfully compare program outcomes even when they share the same content.

The USPSTF’s draft recommendations also explicitly avoid what the American Academy of Pediatrics has rightly embraced: the use where appropriate of medications or surgery. While opponents of the use of pharmacotherapy for childhood obesity tend to point to a lack of long-term data as rationale for its denial, something that the USPSTF has done, again, we have long-term data demonstrating a lack of scalable, clinically meaningful efficacy for service only based programs.

Childhood obesity is a flood and its ongoing current is relentless. Given its tremendous impact, especially at its extremes, on both physical and mental health, this is yet another example of systemic weight bias in action — it’s as if the USPSTF is recommending a swimming lesson–only approach while actively fearmongering, despite an absence of plausible mechanistic risk, about the long-term use of life jackets.

Dr. Freedhoff is associate professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa; Medical Director, Bariatric Medical Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Dr. Freedhoff has disclosed ties with Bariatric Medical Institute, Constant Health, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has published draft recommendations that 6-year-olds with obesity be lectured to about diet and exercise.

Never mind that there are no reproducible or scalable studies demonstrating durable and clinically meaningful benefits of this for adults let alone children. Never mind that children are not household decision-makers on matters of grocery shopping, cooking, or exercise. Never mind the corollary that many children so lectured who fail to see an impact on their weight will perceive that as their own personal failures. And of course, never mind that we’re privileged to be in an era with safe, effective, pharmacotherapeutic options for obesity. No. We must teach children it’s their fault if they’re fat. Because ultimately that’s what many of them will learn.

That’s not to say there’s no room for counseling. But with children as young as 6, that counseling should be delivered exclusively to their parents and caregivers. That counseling should focus as much if not more so on the impact of weight bias and the biological basis of obesity rather than diet and exercise, while explicitly teaching parents the means to discuss nutrition without risking their children feeling worse about themselves, increasing the risk for conflict over changes, or heightening their children’s chance of developing eating disorders or maladaptive relationships with food.

But back to the USPSTF’s actual recommendation for those 6 years old and up. They’re recommending “at least” 26 hours of lectures over a year-long interprofessional intervention. Putting aside the reality that this isn’t scalable time-wise or cost-wise to reach even a fraction of the roughly 15 million US children with obesity, there is also the issue of service provision. Because when it comes to obesity, if the intervention is purely educational, even if you want to believe there is a syllabus out there that would have a dramatic impact, its impact will vary wildly depending on the skill and approach of the service providers. This inconvenient truth is also the one that makes it impossible to meaningfully compare program outcomes even when they share the same content.

The USPSTF’s draft recommendations also explicitly avoid what the American Academy of Pediatrics has rightly embraced: the use where appropriate of medications or surgery. While opponents of the use of pharmacotherapy for childhood obesity tend to point to a lack of long-term data as rationale for its denial, something that the USPSTF has done, again, we have long-term data demonstrating a lack of scalable, clinically meaningful efficacy for service only based programs.

Childhood obesity is a flood and its ongoing current is relentless. Given its tremendous impact, especially at its extremes, on both physical and mental health, this is yet another example of systemic weight bias in action — it’s as if the USPSTF is recommending a swimming lesson–only approach while actively fearmongering, despite an absence of plausible mechanistic risk, about the long-term use of life jackets.

Dr. Freedhoff is associate professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa; Medical Director, Bariatric Medical Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Dr. Freedhoff has disclosed ties with Bariatric Medical Institute, Constant Health, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has published draft recommendations that 6-year-olds with obesity be lectured to about diet and exercise.

Never mind that there are no reproducible or scalable studies demonstrating durable and clinically meaningful benefits of this for adults let alone children. Never mind that children are not household decision-makers on matters of grocery shopping, cooking, or exercise. Never mind the corollary that many children so lectured who fail to see an impact on their weight will perceive that as their own personal failures. And of course, never mind that we’re privileged to be in an era with safe, effective, pharmacotherapeutic options for obesity. No. We must teach children it’s their fault if they’re fat. Because ultimately that’s what many of them will learn.

That’s not to say there’s no room for counseling. But with children as young as 6, that counseling should be delivered exclusively to their parents and caregivers. That counseling should focus as much if not more so on the impact of weight bias and the biological basis of obesity rather than diet and exercise, while explicitly teaching parents the means to discuss nutrition without risking their children feeling worse about themselves, increasing the risk for conflict over changes, or heightening their children’s chance of developing eating disorders or maladaptive relationships with food.

But back to the USPSTF’s actual recommendation for those 6 years old and up. They’re recommending “at least” 26 hours of lectures over a year-long interprofessional intervention. Putting aside the reality that this isn’t scalable time-wise or cost-wise to reach even a fraction of the roughly 15 million US children with obesity, there is also the issue of service provision. Because when it comes to obesity, if the intervention is purely educational, even if you want to believe there is a syllabus out there that would have a dramatic impact, its impact will vary wildly depending on the skill and approach of the service providers. This inconvenient truth is also the one that makes it impossible to meaningfully compare program outcomes even when they share the same content.

The USPSTF’s draft recommendations also explicitly avoid what the American Academy of Pediatrics has rightly embraced: the use where appropriate of medications or surgery. While opponents of the use of pharmacotherapy for childhood obesity tend to point to a lack of long-term data as rationale for its denial, something that the USPSTF has done, again, we have long-term data demonstrating a lack of scalable, clinically meaningful efficacy for service only based programs.

Childhood obesity is a flood and its ongoing current is relentless. Given its tremendous impact, especially at its extremes, on both physical and mental health, this is yet another example of systemic weight bias in action — it’s as if the USPSTF is recommending a swimming lesson–only approach while actively fearmongering, despite an absence of plausible mechanistic risk, about the long-term use of life jackets.

Dr. Freedhoff is associate professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa; Medical Director, Bariatric Medical Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Dr. Freedhoff has disclosed ties with Bariatric Medical Institute, Constant Health, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Tips and Techniques to Boost Colonoscopy Quality

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When it comes to the use of colonoscopy to reduce the risk for cancer, quality is key.

There are a number of performance improvements we can make in our practices so that we can do better. This is evident in several recently published studies and a recent review article on the topic, which I’d like to profile for you; many of these key quality indicators you can implement now.

Even though it may take more time before they’re supported in the guidelines, you’ll see that the evidence behind these is extraordinarily strong.

Increasing the Adenoma Detection Rate

Certainly, we all do what we can to increase the adenoma detection rate (ADR).

However, at the moment, the nationally recommended benchmark is to achieve an ADR of 25%, which is inordinately low. The ADR rate reported in the GIQuIC registry data is closer to 39%, and in high-level detectors, it’s actually in the greater-than-50% range.

There’s no question that we can do more, and there are a number of ways to do that.

First, This may actually decrease your withdrawal time because you don’t spend so much time trying to face these folds.

In considering tools to aid ADR, don’t forget electronic chromoendoscopy (eg, narrow-band imaging).

There are a number of new artificial intelligence options out there as well, which have been reported to increase the ADR by approximately 10%. Of importance, this improvement even occurs among expert endoscopists.

There’s also important emerging data about ADR in fecal immunochemical test (FIT)–positive patients. FIT-positive status increases the ADR threshold by 15%-20%. This places you in an ADR range of approximately 50%, which is really the norm when screening patients that present for colonoscopy because of FIT positivity.

Adenoma Per Colonoscopy: A Possible ADR Substitute

Growing evidence supports the use of adenoma per colonoscopy (APC) as a substitute to ADR. This would allow you to record every adenoma and attribute it to that index colonoscopy.

A high-quality paper showed that the APC value should be around 0.6 to achieve the current ADR minimum threshold of 25%. Having the APC < 0.6 seems to be associated with an increased risk for residual polyp. Sessile serrated lesions also increased the hazard ratio for interval colorectal cancer. This was evaluated recently with data from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, which Dr Joseph Anderson has led for so long. They showed that 21% of endoscopists had an ADR of 25% or greater but still had APCs < 0.6.

Therefore, when it comes to remedial corrective work, doctors need to be reevaluated, retrained, and educated in the ways that they can incorporate this. The APC in high-level detectors is > 1.0.

APC may be something you want to consider using internally. It does require that you place each polyp into an individual jar, which can increase incremental cost. Nonetheless, there is clear evidence that APC positively changes outcomes.

Including Sessile Serrated Lesions in ADR Detectors

Unfortunately, some of the high-level ADR detectors aren’t so “high level” when it comes to detecting sessile serrated lesions. It’s not quite as concordant as we had previously thought.

Nonetheless, there are many adjunctive things you can do with sessile serrated lesions, including narrow-band imaging and chromoendoscopy.

When it comes to establishing a discriminant, the numbers should be 5%-6% if we’re going to set a quality ratio and an index. However, this is somewhat dependent on your pathologist because they have to read these correctly. Lesions that are ≥ 6 mm above the sigmoid colon and anything in the right colon should be evaluated really closely as a sessile serrated lesion.

I’ve had indications where the pathologist says the lesion is hyperplastic, to which I say, “I’m going to follow as a sessile serrated lesion.” This is because it’s apparent to me in the endoscopic appearance and the narrow-band imaging appearance that it was characteristic of sessile serrated lesions.

Best Practices in Bowel Preparations

The US Multi-Society Task Force recommends that adequate bowel preparation should occur in 85% or more of outpatients, and for the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, it’s 90% or more.

I’ll pass along a tip I use in my patients undergoing bowel preparation: I make them aware that during this process, they want to see a clear, yellow, urine-like color to their stool. Otherwise, many patients will think if they’ve had some diarrhea, they don’t need to finish prep. Setting that expectation for them upfront is really important.

The nurses also should be aware of this because if there’s a murky brown effluent upon presentation for the colonoscopy, there’s a greater than 50% chance that they’re going to have had an inadequate preparation. In such cases, you would want to preempt the colonoscopy and perhaps send them out for a re-prep that day or bring them back for a rescheduled appointment.

Resection Considerations

There is substantial variation when it comes to lesion resection, which makes it an important quality indicator on which to focus: High-level detectors aren’t always high-level resectors.

There are two validated instruments that you can use to gauge the adequacy of resection. Those aren’t really ready for prime time in every practice, though they may be seen in fellowship programs.

The idea here is that you want to get a ≥ 2 mm margin for cold snare polypectomy in lesions 1-10 mm in size. This has been a challenge, as findings indicate we don’t do this that well.

Joseph Anderson and colleagues recently published a study using a 2-mm resection margin. They reported that this was only possible in approximately 28% of polyps. For a 1-mm margin, the rate was 84%.

We simply need to set clearer margins when setting our snare. Make sure you’re close enough to the polyp, push down on the snare, and get a good margin of tissue.

When the sample contracts are placed into the formalin, it’s not quite so simple to define the margin at the time of the surgical resection. This often requires an audit evaluation by the pathologist.

There are two other considerations regarding resection.

The first is about the referral for surgery. Referral should not occur for any benign lesions ascribed by your endoscopic advanced imaging techniques and classifications that are not thought to have intramucosal carcinoma. These should be referred to an expert endoscopic evaluation. If you can’t do it, then somebody else should. And you shouldn’t attempt it unless you can get it totally because resection of partially resected lesions is much more complicated. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy says this applies to any benign lesion of any size, which I think really is the emerging standard of care. You should consider and offer that to the patient. It may require a referral for outside of your institution.

The second additional consideration is around the minimization of cold forceps for removal of polyps. The US Multi-Society Task Force says cold forceps shouldn’t be used for any lesions > 2 mm, whereas for the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, it is > 3 mm. However, it’s still done very commonly in clinical practice. Nibbling the polyp is not an option. Cold snare is actually quicker, more effective, has better outcomes, and is something that you can bill for when you look at the coding.

In summary, there are a lot of things that we can do now to improve colonoscopy. Quality indicators continue to emerge with a compelling, excellent evidence base that strongly supports their use. Given that, I think most of these are actionable now, and it’s not necessary to wait for the guidelines to begin using them. I’d therefore challenge all of us to incorporate them in our continual efforts to do better.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. His primary focus is the clinical practice of gastroenterology. He has published extensively in the internal medicine/gastroenterology literature, with principal research interests in esophageal and colon disease, and more recently in sleep and microbiome effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. He has disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When it comes to the use of colonoscopy to reduce the risk for cancer, quality is key.

There are a number of performance improvements we can make in our practices so that we can do better. This is evident in several recently published studies and a recent review article on the topic, which I’d like to profile for you; many of these key quality indicators you can implement now.

Even though it may take more time before they’re supported in the guidelines, you’ll see that the evidence behind these is extraordinarily strong.

Increasing the Adenoma Detection Rate

Certainly, we all do what we can to increase the adenoma detection rate (ADR).

However, at the moment, the nationally recommended benchmark is to achieve an ADR of 25%, which is inordinately low. The ADR rate reported in the GIQuIC registry data is closer to 39%, and in high-level detectors, it’s actually in the greater-than-50% range.

There’s no question that we can do more, and there are a number of ways to do that.

First, This may actually decrease your withdrawal time because you don’t spend so much time trying to face these folds.

In considering tools to aid ADR, don’t forget electronic chromoendoscopy (eg, narrow-band imaging).

There are a number of new artificial intelligence options out there as well, which have been reported to increase the ADR by approximately 10%. Of importance, this improvement even occurs among expert endoscopists.

There’s also important emerging data about ADR in fecal immunochemical test (FIT)–positive patients. FIT-positive status increases the ADR threshold by 15%-20%. This places you in an ADR range of approximately 50%, which is really the norm when screening patients that present for colonoscopy because of FIT positivity.

Adenoma Per Colonoscopy: A Possible ADR Substitute

Growing evidence supports the use of adenoma per colonoscopy (APC) as a substitute to ADR. This would allow you to record every adenoma and attribute it to that index colonoscopy.

A high-quality paper showed that the APC value should be around 0.6 to achieve the current ADR minimum threshold of 25%. Having the APC < 0.6 seems to be associated with an increased risk for residual polyp. Sessile serrated lesions also increased the hazard ratio for interval colorectal cancer. This was evaluated recently with data from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, which Dr Joseph Anderson has led for so long. They showed that 21% of endoscopists had an ADR of 25% or greater but still had APCs < 0.6.

Therefore, when it comes to remedial corrective work, doctors need to be reevaluated, retrained, and educated in the ways that they can incorporate this. The APC in high-level detectors is > 1.0.

APC may be something you want to consider using internally. It does require that you place each polyp into an individual jar, which can increase incremental cost. Nonetheless, there is clear evidence that APC positively changes outcomes.

Including Sessile Serrated Lesions in ADR Detectors

Unfortunately, some of the high-level ADR detectors aren’t so “high level” when it comes to detecting sessile serrated lesions. It’s not quite as concordant as we had previously thought.

Nonetheless, there are many adjunctive things you can do with sessile serrated lesions, including narrow-band imaging and chromoendoscopy.

When it comes to establishing a discriminant, the numbers should be 5%-6% if we’re going to set a quality ratio and an index. However, this is somewhat dependent on your pathologist because they have to read these correctly. Lesions that are ≥ 6 mm above the sigmoid colon and anything in the right colon should be evaluated really closely as a sessile serrated lesion.

I’ve had indications where the pathologist says the lesion is hyperplastic, to which I say, “I’m going to follow as a sessile serrated lesion.” This is because it’s apparent to me in the endoscopic appearance and the narrow-band imaging appearance that it was characteristic of sessile serrated lesions.

Best Practices in Bowel Preparations

The US Multi-Society Task Force recommends that adequate bowel preparation should occur in 85% or more of outpatients, and for the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, it’s 90% or more.

I’ll pass along a tip I use in my patients undergoing bowel preparation: I make them aware that during this process, they want to see a clear, yellow, urine-like color to their stool. Otherwise, many patients will think if they’ve had some diarrhea, they don’t need to finish prep. Setting that expectation for them upfront is really important.

The nurses also should be aware of this because if there’s a murky brown effluent upon presentation for the colonoscopy, there’s a greater than 50% chance that they’re going to have had an inadequate preparation. In such cases, you would want to preempt the colonoscopy and perhaps send them out for a re-prep that day or bring them back for a rescheduled appointment.

Resection Considerations

There is substantial variation when it comes to lesion resection, which makes it an important quality indicator on which to focus: High-level detectors aren’t always high-level resectors.

There are two validated instruments that you can use to gauge the adequacy of resection. Those aren’t really ready for prime time in every practice, though they may be seen in fellowship programs.

The idea here is that you want to get a ≥ 2 mm margin for cold snare polypectomy in lesions 1-10 mm in size. This has been a challenge, as findings indicate we don’t do this that well.

Joseph Anderson and colleagues recently published a study using a 2-mm resection margin. They reported that this was only possible in approximately 28% of polyps. For a 1-mm margin, the rate was 84%.

We simply need to set clearer margins when setting our snare. Make sure you’re close enough to the polyp, push down on the snare, and get a good margin of tissue.

When the sample contracts are placed into the formalin, it’s not quite so simple to define the margin at the time of the surgical resection. This often requires an audit evaluation by the pathologist.

There are two other considerations regarding resection.

The first is about the referral for surgery. Referral should not occur for any benign lesions ascribed by your endoscopic advanced imaging techniques and classifications that are not thought to have intramucosal carcinoma. These should be referred to an expert endoscopic evaluation. If you can’t do it, then somebody else should. And you shouldn’t attempt it unless you can get it totally because resection of partially resected lesions is much more complicated. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy says this applies to any benign lesion of any size, which I think really is the emerging standard of care. You should consider and offer that to the patient. It may require a referral for outside of your institution.

The second additional consideration is around the minimization of cold forceps for removal of polyps. The US Multi-Society Task Force says cold forceps shouldn’t be used for any lesions > 2 mm, whereas for the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, it is > 3 mm. However, it’s still done very commonly in clinical practice. Nibbling the polyp is not an option. Cold snare is actually quicker, more effective, has better outcomes, and is something that you can bill for when you look at the coding.

In summary, there are a lot of things that we can do now to improve colonoscopy. Quality indicators continue to emerge with a compelling, excellent evidence base that strongly supports their use. Given that, I think most of these are actionable now, and it’s not necessary to wait for the guidelines to begin using them. I’d therefore challenge all of us to incorporate them in our continual efforts to do better.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. His primary focus is the clinical practice of gastroenterology. He has published extensively in the internal medicine/gastroenterology literature, with principal research interests in esophageal and colon disease, and more recently in sleep and microbiome effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. He has disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When it comes to the use of colonoscopy to reduce the risk for cancer, quality is key.

There are a number of performance improvements we can make in our practices so that we can do better. This is evident in several recently published studies and a recent review article on the topic, which I’d like to profile for you; many of these key quality indicators you can implement now.

Even though it may take more time before they’re supported in the guidelines, you’ll see that the evidence behind these is extraordinarily strong.

Increasing the Adenoma Detection Rate

Certainly, we all do what we can to increase the adenoma detection rate (ADR).

However, at the moment, the nationally recommended benchmark is to achieve an ADR of 25%, which is inordinately low. The ADR rate reported in the GIQuIC registry data is closer to 39%, and in high-level detectors, it’s actually in the greater-than-50% range.

There’s no question that we can do more, and there are a number of ways to do that.

First, This may actually decrease your withdrawal time because you don’t spend so much time trying to face these folds.

In considering tools to aid ADR, don’t forget electronic chromoendoscopy (eg, narrow-band imaging).

There are a number of new artificial intelligence options out there as well, which have been reported to increase the ADR by approximately 10%. Of importance, this improvement even occurs among expert endoscopists.

There’s also important emerging data about ADR in fecal immunochemical test (FIT)–positive patients. FIT-positive status increases the ADR threshold by 15%-20%. This places you in an ADR range of approximately 50%, which is really the norm when screening patients that present for colonoscopy because of FIT positivity.

Adenoma Per Colonoscopy: A Possible ADR Substitute

Growing evidence supports the use of adenoma per colonoscopy (APC) as a substitute to ADR. This would allow you to record every adenoma and attribute it to that index colonoscopy.

A high-quality paper showed that the APC value should be around 0.6 to achieve the current ADR minimum threshold of 25%. Having the APC < 0.6 seems to be associated with an increased risk for residual polyp. Sessile serrated lesions also increased the hazard ratio for interval colorectal cancer. This was evaluated recently with data from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, which Dr Joseph Anderson has led for so long. They showed that 21% of endoscopists had an ADR of 25% or greater but still had APCs < 0.6.

Therefore, when it comes to remedial corrective work, doctors need to be reevaluated, retrained, and educated in the ways that they can incorporate this. The APC in high-level detectors is > 1.0.

APC may be something you want to consider using internally. It does require that you place each polyp into an individual jar, which can increase incremental cost. Nonetheless, there is clear evidence that APC positively changes outcomes.

Including Sessile Serrated Lesions in ADR Detectors

Unfortunately, some of the high-level ADR detectors aren’t so “high level” when it comes to detecting sessile serrated lesions. It’s not quite as concordant as we had previously thought.

Nonetheless, there are many adjunctive things you can do with sessile serrated lesions, including narrow-band imaging and chromoendoscopy.

When it comes to establishing a discriminant, the numbers should be 5%-6% if we’re going to set a quality ratio and an index. However, this is somewhat dependent on your pathologist because they have to read these correctly. Lesions that are ≥ 6 mm above the sigmoid colon and anything in the right colon should be evaluated really closely as a sessile serrated lesion.

I’ve had indications where the pathologist says the lesion is hyperplastic, to which I say, “I’m going to follow as a sessile serrated lesion.” This is because it’s apparent to me in the endoscopic appearance and the narrow-band imaging appearance that it was characteristic of sessile serrated lesions.

Best Practices in Bowel Preparations

The US Multi-Society Task Force recommends that adequate bowel preparation should occur in 85% or more of outpatients, and for the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, it’s 90% or more.

I’ll pass along a tip I use in my patients undergoing bowel preparation: I make them aware that during this process, they want to see a clear, yellow, urine-like color to their stool. Otherwise, many patients will think if they’ve had some diarrhea, they don’t need to finish prep. Setting that expectation for them upfront is really important.

The nurses also should be aware of this because if there’s a murky brown effluent upon presentation for the colonoscopy, there’s a greater than 50% chance that they’re going to have had an inadequate preparation. In such cases, you would want to preempt the colonoscopy and perhaps send them out for a re-prep that day or bring them back for a rescheduled appointment.

Resection Considerations

There is substantial variation when it comes to lesion resection, which makes it an important quality indicator on which to focus: High-level detectors aren’t always high-level resectors.

There are two validated instruments that you can use to gauge the adequacy of resection. Those aren’t really ready for prime time in every practice, though they may be seen in fellowship programs.

The idea here is that you want to get a ≥ 2 mm margin for cold snare polypectomy in lesions 1-10 mm in size. This has been a challenge, as findings indicate we don’t do this that well.

Joseph Anderson and colleagues recently published a study using a 2-mm resection margin. They reported that this was only possible in approximately 28% of polyps. For a 1-mm margin, the rate was 84%.

We simply need to set clearer margins when setting our snare. Make sure you’re close enough to the polyp, push down on the snare, and get a good margin of tissue.

When the sample contracts are placed into the formalin, it’s not quite so simple to define the margin at the time of the surgical resection. This often requires an audit evaluation by the pathologist.

There are two other considerations regarding resection.

The first is about the referral for surgery. Referral should not occur for any benign lesions ascribed by your endoscopic advanced imaging techniques and classifications that are not thought to have intramucosal carcinoma. These should be referred to an expert endoscopic evaluation. If you can’t do it, then somebody else should. And you shouldn’t attempt it unless you can get it totally because resection of partially resected lesions is much more complicated. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy says this applies to any benign lesion of any size, which I think really is the emerging standard of care. You should consider and offer that to the patient. It may require a referral for outside of your institution.

The second additional consideration is around the minimization of cold forceps for removal of polyps. The US Multi-Society Task Force says cold forceps shouldn’t be used for any lesions > 2 mm, whereas for the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, it is > 3 mm. However, it’s still done very commonly in clinical practice. Nibbling the polyp is not an option. Cold snare is actually quicker, more effective, has better outcomes, and is something that you can bill for when you look at the coding.

In summary, there are a lot of things that we can do now to improve colonoscopy. Quality indicators continue to emerge with a compelling, excellent evidence base that strongly supports their use. Given that, I think most of these are actionable now, and it’s not necessary to wait for the guidelines to begin using them. I’d therefore challenge all of us to incorporate them in our continual efforts to do better.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. His primary focus is the clinical practice of gastroenterology. He has published extensively in the internal medicine/gastroenterology literature, with principal research interests in esophageal and colon disease, and more recently in sleep and microbiome effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. He has disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Biosimilar Business Deals Keep Up ‘Musical Chairs’ Game of Formulary Construction

As the saying goes, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” That is particularly true when it comes to the affordability of drugs for our patients even after the launch of so many Humira biosimilars. And we still have the “musical chairs” game of formulary construction — when the music stops, who knows whether your patient’s drug found a chair to sit on. There seems to be only a few chairs available for the many adalimumab biosimilars playing the game.

Nothing has changed since my testimony before the FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee in July 2016 during the approval hearing of the first Humira biosimilar. Below is a quote from that meeting where I was speaking predominantly about the pharmacy side of drugs.

“I’d like to highlight the term ‘access’ because none of us are really naive enough to believe that just approving a biosimilar gives a patient true, hands-on access to the medication, because even if the biosimilar is offered at a 30% discount, I don’t have any patients that can afford it. This means that access is ultimately controlled by third-party payers.”

My prediction, that approving and launching biosimilars with lower prices would not ensure patient access to the drug unless it is paid for by insurance, is now our reality. Today, a drug with an 85% discount on the price of Humira is still unattainable for patients without a “payer.”

Competition and Lower Prices

Lawmakers and some in the media cry for more competition to lower prices. This is the main reason that there has been such a push to get biosimilars to the market as quickly as possible. It is abundantly clear that competition to get on the formulary is fierce. Placement of a medication on a formulary can make or break a manufacturer’s ability to get a return on the R&D and make a profit on that medication. For a small biotech manufacturer, it can be the difference between “life and death” of the company.

Does anyone remember when the first interchangeable biosimilar for the reference insulin glargine product Lantus (insulin glargine-yfgn; Semglee) came to market in 2021? Janet Woodcock, MD, then acting FDA commissioner, called it a “momentous day” and further said, “Today’s approval of the first interchangeable biosimilar product furthers FDA’s longstanding commitment to support a competitive marketplace for biological products and ultimately empowers patients by helping to increase access to safe, effective and high-quality medications at potentially lower cost.” There was a high-priced interchangeable biosimilar and an identical unbranded low-priced interchangeable biosimilar, and the only one that could get formulary placement was the high-priced drug.

Patients pay their cost share on the list price of the drug, and because most pharmacy benefit managers’ (PBMs’) formularies cover only the high-priced biosimilar, patients never share in the savings. So much for the “competitive marketplace” creating lower costs for patients. This is just one of hundreds of examples in which lower-priced drugs are excluded from the formulary. It is unfortunate that the bidding process from manufacturers to PBMs to “win” preferred formulary placement is like an art auction, where the highest bidder wins.

Biosimilars and Formulary Construction

For those of us who have been looking into PBMs for many years, it is no surprise that PBMs’ formulary construction has become a profit center for them. Now, with so many adalimumab biosimilars having entered the market, it has become the Wild West where only those with the most money to fork over to the PBMs get preferred placement. Unfortunately, many of the choices that make money for the PBM cost employers and patients more.

How did we get here? In the 1980s and 90s, the price of medications began to increase to the point that many were not affordable without insurance. And who better to construct the list of drugs that would be covered by insurance (formulary) than the PBMs who were already adjudicating the claims for these drugs. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) realized the power inherent in constructing this list of medications known as the formulary. So when the manufacturer Merck acquired the PBM Medco in the mid-1990s, the FTC stepped in. The FTC surmised that making the drugs and deciding which ones will be paid for created a “conflict of interest” with anticompetitive ramifications.

So, in 1998, William J. Baer, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, said, “Our investigation into the PBM industry has revealed that Merck’s acquisition of Medco has reduced competition in the market for pharmaceutical products … We have found that Medco has given favorable treatment to Merck drugs. As a result, in some cases, consumers have been denied access to the drugs of competing manufacturers. In addition, the merger has made it possible for Medco to share with Merck sensitive pricing information it gets from Merck’s competitors, which could foster collusion among drug manufacturers.” Wow!

These anticompetitive behaviors and conflicts of interest resulting from the Medco acquisition led the FTC to propose a consent agreement.

The agreement would require Merck-Medco to maintain an “open formulary” — one that includes drugs selected and approved by an independent Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee regardless of the manufacturer. Medco would have to accept rebates and other price concessions and reflect these in the ranking of the drugs on the formulary. Merck would have to make known the availability of the open formulary to any drug maker with an agreement with Medco.

Let’s hope the FTC of 2024 remembers the stance of the FTC in the 1990s regarding anticompetitive behavior involved in formulary construction.

Conflicts of Interest

But today it is apparent that crafting formularies that pay only for the drugs that make the most money for the PBM is not a conflict of interest. In its policy manual, Cigna directly tells employers and employees that they are collecting and keeping rebates and fees on medical pharmaceuticals, and they are not for the benefit of the employer or the plan.

And now, in August 2023, CVS launched Cordavis, a subsidiary wholly owned by CVS. Cordavis/CVS has partnered with Sandoz, which makes Hyrimoz, an adalimumab biosimilar. There is a high-priced version that is discounted 5% from Humira, a lower-cost unbranded version that is discounted 80% off the list price of Humira, and a co-branded CVS/Sandoz version of Hyrimoz that is lower priced as well.

It isn’t a surprise that CVS’ Standard and Advanced Commercial and Chart formularies are offering only Sandoz adalimumab biosimilar products. While these formularies have excluded Humira, CVS has entered into an agreement with AbbVie to allow Humira on a number of their other formularies. It can be very confusing.

As stated earlier, in the 1990s, the FTC frowned upon manufacturers owning PBMs and allowing them to construct their own formularies. Here we have CVS Health, mothership for the PBM CVS Caremark, owning a company that will be co-producing biosimilars with other manufacturers and then determining which biosimilars are on their formularies. The FTC knew back then that the tendency would be to offer only their own drugs for coverage, thus reducing competition. This is exactly what the CVS-Cordavis-Sandoz partnership has done for their Standard and Advanced Commercial and Chart formularies. It is perhaps anti-competitive but certainly profitable.

Perhaps the FTC should require the same consent agreement that was given to Merck in 1998. CVS Caremark would then have to open their formularies to all competitors of their co-branded, co-produced Sandoz biosimilar.

Summary

It is the same old adage, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” PBMs are still constructing formularies with biosimilars based on their profitability, with huge differences between gross and net cost. Patients still pay their cost share on the list (gross) price. With the CVS-Cordavis-Sandoz partnership, more vertical integration has led to yet another profit river. Self-funded employers are still getting the wool pulled over their eyes by the big three PBMs who threaten to take away rebates if they don’t choose the preferred formularies. The employers don’t realize that sometimes it is less expensive to choose the lower-priced drugs with no rebates, and that holds true for biosimilars as well.

Let’s hope that the FTC investigates the situation of a PBM partnering with a manufacturer and then choosing only that manufacturer’s drugs for many of their formularies.

We need to continue our advocacy for our patients because the medication that has kept them stable for so long may find itself without a chair the next time the music stops.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

As the saying goes, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” That is particularly true when it comes to the affordability of drugs for our patients even after the launch of so many Humira biosimilars. And we still have the “musical chairs” game of formulary construction — when the music stops, who knows whether your patient’s drug found a chair to sit on. There seems to be only a few chairs available for the many adalimumab biosimilars playing the game.

Nothing has changed since my testimony before the FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee in July 2016 during the approval hearing of the first Humira biosimilar. Below is a quote from that meeting where I was speaking predominantly about the pharmacy side of drugs.

“I’d like to highlight the term ‘access’ because none of us are really naive enough to believe that just approving a biosimilar gives a patient true, hands-on access to the medication, because even if the biosimilar is offered at a 30% discount, I don’t have any patients that can afford it. This means that access is ultimately controlled by third-party payers.”

My prediction, that approving and launching biosimilars with lower prices would not ensure patient access to the drug unless it is paid for by insurance, is now our reality. Today, a drug with an 85% discount on the price of Humira is still unattainable for patients without a “payer.”

Competition and Lower Prices

Lawmakers and some in the media cry for more competition to lower prices. This is the main reason that there has been such a push to get biosimilars to the market as quickly as possible. It is abundantly clear that competition to get on the formulary is fierce. Placement of a medication on a formulary can make or break a manufacturer’s ability to get a return on the R&D and make a profit on that medication. For a small biotech manufacturer, it can be the difference between “life and death” of the company.

Does anyone remember when the first interchangeable biosimilar for the reference insulin glargine product Lantus (insulin glargine-yfgn; Semglee) came to market in 2021? Janet Woodcock, MD, then acting FDA commissioner, called it a “momentous day” and further said, “Today’s approval of the first interchangeable biosimilar product furthers FDA’s longstanding commitment to support a competitive marketplace for biological products and ultimately empowers patients by helping to increase access to safe, effective and high-quality medications at potentially lower cost.” There was a high-priced interchangeable biosimilar and an identical unbranded low-priced interchangeable biosimilar, and the only one that could get formulary placement was the high-priced drug.

Patients pay their cost share on the list price of the drug, and because most pharmacy benefit managers’ (PBMs’) formularies cover only the high-priced biosimilar, patients never share in the savings. So much for the “competitive marketplace” creating lower costs for patients. This is just one of hundreds of examples in which lower-priced drugs are excluded from the formulary. It is unfortunate that the bidding process from manufacturers to PBMs to “win” preferred formulary placement is like an art auction, where the highest bidder wins.

Biosimilars and Formulary Construction

For those of us who have been looking into PBMs for many years, it is no surprise that PBMs’ formulary construction has become a profit center for them. Now, with so many adalimumab biosimilars having entered the market, it has become the Wild West where only those with the most money to fork over to the PBMs get preferred placement. Unfortunately, many of the choices that make money for the PBM cost employers and patients more.

How did we get here? In the 1980s and 90s, the price of medications began to increase to the point that many were not affordable without insurance. And who better to construct the list of drugs that would be covered by insurance (formulary) than the PBMs who were already adjudicating the claims for these drugs. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) realized the power inherent in constructing this list of medications known as the formulary. So when the manufacturer Merck acquired the PBM Medco in the mid-1990s, the FTC stepped in. The FTC surmised that making the drugs and deciding which ones will be paid for created a “conflict of interest” with anticompetitive ramifications.

So, in 1998, William J. Baer, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, said, “Our investigation into the PBM industry has revealed that Merck’s acquisition of Medco has reduced competition in the market for pharmaceutical products … We have found that Medco has given favorable treatment to Merck drugs. As a result, in some cases, consumers have been denied access to the drugs of competing manufacturers. In addition, the merger has made it possible for Medco to share with Merck sensitive pricing information it gets from Merck’s competitors, which could foster collusion among drug manufacturers.” Wow!

These anticompetitive behaviors and conflicts of interest resulting from the Medco acquisition led the FTC to propose a consent agreement.

The agreement would require Merck-Medco to maintain an “open formulary” — one that includes drugs selected and approved by an independent Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee regardless of the manufacturer. Medco would have to accept rebates and other price concessions and reflect these in the ranking of the drugs on the formulary. Merck would have to make known the availability of the open formulary to any drug maker with an agreement with Medco.

Let’s hope the FTC of 2024 remembers the stance of the FTC in the 1990s regarding anticompetitive behavior involved in formulary construction.

Conflicts of Interest

But today it is apparent that crafting formularies that pay only for the drugs that make the most money for the PBM is not a conflict of interest. In its policy manual, Cigna directly tells employers and employees that they are collecting and keeping rebates and fees on medical pharmaceuticals, and they are not for the benefit of the employer or the plan.

And now, in August 2023, CVS launched Cordavis, a subsidiary wholly owned by CVS. Cordavis/CVS has partnered with Sandoz, which makes Hyrimoz, an adalimumab biosimilar. There is a high-priced version that is discounted 5% from Humira, a lower-cost unbranded version that is discounted 80% off the list price of Humira, and a co-branded CVS/Sandoz version of Hyrimoz that is lower priced as well.

It isn’t a surprise that CVS’ Standard and Advanced Commercial and Chart formularies are offering only Sandoz adalimumab biosimilar products. While these formularies have excluded Humira, CVS has entered into an agreement with AbbVie to allow Humira on a number of their other formularies. It can be very confusing.

As stated earlier, in the 1990s, the FTC frowned upon manufacturers owning PBMs and allowing them to construct their own formularies. Here we have CVS Health, mothership for the PBM CVS Caremark, owning a company that will be co-producing biosimilars with other manufacturers and then determining which biosimilars are on their formularies. The FTC knew back then that the tendency would be to offer only their own drugs for coverage, thus reducing competition. This is exactly what the CVS-Cordavis-Sandoz partnership has done for their Standard and Advanced Commercial and Chart formularies. It is perhaps anti-competitive but certainly profitable.

Perhaps the FTC should require the same consent agreement that was given to Merck in 1998. CVS Caremark would then have to open their formularies to all competitors of their co-branded, co-produced Sandoz biosimilar.

Summary

It is the same old adage, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” PBMs are still constructing formularies with biosimilars based on their profitability, with huge differences between gross and net cost. Patients still pay their cost share on the list (gross) price. With the CVS-Cordavis-Sandoz partnership, more vertical integration has led to yet another profit river. Self-funded employers are still getting the wool pulled over their eyes by the big three PBMs who threaten to take away rebates if they don’t choose the preferred formularies. The employers don’t realize that sometimes it is less expensive to choose the lower-priced drugs with no rebates, and that holds true for biosimilars as well.

Let’s hope that the FTC investigates the situation of a PBM partnering with a manufacturer and then choosing only that manufacturer’s drugs for many of their formularies.

We need to continue our advocacy for our patients because the medication that has kept them stable for so long may find itself without a chair the next time the music stops.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

As the saying goes, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” That is particularly true when it comes to the affordability of drugs for our patients even after the launch of so many Humira biosimilars. And we still have the “musical chairs” game of formulary construction — when the music stops, who knows whether your patient’s drug found a chair to sit on. There seems to be only a few chairs available for the many adalimumab biosimilars playing the game.

Nothing has changed since my testimony before the FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee in July 2016 during the approval hearing of the first Humira biosimilar. Below is a quote from that meeting where I was speaking predominantly about the pharmacy side of drugs.

“I’d like to highlight the term ‘access’ because none of us are really naive enough to believe that just approving a biosimilar gives a patient true, hands-on access to the medication, because even if the biosimilar is offered at a 30% discount, I don’t have any patients that can afford it. This means that access is ultimately controlled by third-party payers.”

My prediction, that approving and launching biosimilars with lower prices would not ensure patient access to the drug unless it is paid for by insurance, is now our reality. Today, a drug with an 85% discount on the price of Humira is still unattainable for patients without a “payer.”

Competition and Lower Prices

Lawmakers and some in the media cry for more competition to lower prices. This is the main reason that there has been such a push to get biosimilars to the market as quickly as possible. It is abundantly clear that competition to get on the formulary is fierce. Placement of a medication on a formulary can make or break a manufacturer’s ability to get a return on the R&D and make a profit on that medication. For a small biotech manufacturer, it can be the difference between “life and death” of the company.

Does anyone remember when the first interchangeable biosimilar for the reference insulin glargine product Lantus (insulin glargine-yfgn; Semglee) came to market in 2021? Janet Woodcock, MD, then acting FDA commissioner, called it a “momentous day” and further said, “Today’s approval of the first interchangeable biosimilar product furthers FDA’s longstanding commitment to support a competitive marketplace for biological products and ultimately empowers patients by helping to increase access to safe, effective and high-quality medications at potentially lower cost.” There was a high-priced interchangeable biosimilar and an identical unbranded low-priced interchangeable biosimilar, and the only one that could get formulary placement was the high-priced drug.

Patients pay their cost share on the list price of the drug, and because most pharmacy benefit managers’ (PBMs’) formularies cover only the high-priced biosimilar, patients never share in the savings. So much for the “competitive marketplace” creating lower costs for patients. This is just one of hundreds of examples in which lower-priced drugs are excluded from the formulary. It is unfortunate that the bidding process from manufacturers to PBMs to “win” preferred formulary placement is like an art auction, where the highest bidder wins.

Biosimilars and Formulary Construction

For those of us who have been looking into PBMs for many years, it is no surprise that PBMs’ formulary construction has become a profit center for them. Now, with so many adalimumab biosimilars having entered the market, it has become the Wild West where only those with the most money to fork over to the PBMs get preferred placement. Unfortunately, many of the choices that make money for the PBM cost employers and patients more.

How did we get here? In the 1980s and 90s, the price of medications began to increase to the point that many were not affordable without insurance. And who better to construct the list of drugs that would be covered by insurance (formulary) than the PBMs who were already adjudicating the claims for these drugs. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) realized the power inherent in constructing this list of medications known as the formulary. So when the manufacturer Merck acquired the PBM Medco in the mid-1990s, the FTC stepped in. The FTC surmised that making the drugs and deciding which ones will be paid for created a “conflict of interest” with anticompetitive ramifications.

So, in 1998, William J. Baer, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, said, “Our investigation into the PBM industry has revealed that Merck’s acquisition of Medco has reduced competition in the market for pharmaceutical products … We have found that Medco has given favorable treatment to Merck drugs. As a result, in some cases, consumers have been denied access to the drugs of competing manufacturers. In addition, the merger has made it possible for Medco to share with Merck sensitive pricing information it gets from Merck’s competitors, which could foster collusion among drug manufacturers.” Wow!

These anticompetitive behaviors and conflicts of interest resulting from the Medco acquisition led the FTC to propose a consent agreement.

The agreement would require Merck-Medco to maintain an “open formulary” — one that includes drugs selected and approved by an independent Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee regardless of the manufacturer. Medco would have to accept rebates and other price concessions and reflect these in the ranking of the drugs on the formulary. Merck would have to make known the availability of the open formulary to any drug maker with an agreement with Medco.

Let’s hope the FTC of 2024 remembers the stance of the FTC in the 1990s regarding anticompetitive behavior involved in formulary construction.

Conflicts of Interest

But today it is apparent that crafting formularies that pay only for the drugs that make the most money for the PBM is not a conflict of interest. In its policy manual, Cigna directly tells employers and employees that they are collecting and keeping rebates and fees on medical pharmaceuticals, and they are not for the benefit of the employer or the plan.

And now, in August 2023, CVS launched Cordavis, a subsidiary wholly owned by CVS. Cordavis/CVS has partnered with Sandoz, which makes Hyrimoz, an adalimumab biosimilar. There is a high-priced version that is discounted 5% from Humira, a lower-cost unbranded version that is discounted 80% off the list price of Humira, and a co-branded CVS/Sandoz version of Hyrimoz that is lower priced as well.

It isn’t a surprise that CVS’ Standard and Advanced Commercial and Chart formularies are offering only Sandoz adalimumab biosimilar products. While these formularies have excluded Humira, CVS has entered into an agreement with AbbVie to allow Humira on a number of their other formularies. It can be very confusing.

As stated earlier, in the 1990s, the FTC frowned upon manufacturers owning PBMs and allowing them to construct their own formularies. Here we have CVS Health, mothership for the PBM CVS Caremark, owning a company that will be co-producing biosimilars with other manufacturers and then determining which biosimilars are on their formularies. The FTC knew back then that the tendency would be to offer only their own drugs for coverage, thus reducing competition. This is exactly what the CVS-Cordavis-Sandoz partnership has done for their Standard and Advanced Commercial and Chart formularies. It is perhaps anti-competitive but certainly profitable.

Perhaps the FTC should require the same consent agreement that was given to Merck in 1998. CVS Caremark would then have to open their formularies to all competitors of their co-branded, co-produced Sandoz biosimilar.

Summary

It is the same old adage, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” PBMs are still constructing formularies with biosimilars based on their profitability, with huge differences between gross and net cost. Patients still pay their cost share on the list (gross) price. With the CVS-Cordavis-Sandoz partnership, more vertical integration has led to yet another profit river. Self-funded employers are still getting the wool pulled over their eyes by the big three PBMs who threaten to take away rebates if they don’t choose the preferred formularies. The employers don’t realize that sometimes it is less expensive to choose the lower-priced drugs with no rebates, and that holds true for biosimilars as well.

Let’s hope that the FTC investigates the situation of a PBM partnering with a manufacturer and then choosing only that manufacturer’s drugs for many of their formularies.

We need to continue our advocacy for our patients because the medication that has kept them stable for so long may find itself without a chair the next time the music stops.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

Magnesium Sulfate for Fetal Neuroprotection in Preterm Birth

Introduction: The Many Lanes of Research on Magnesium Sulfate

The research that improves human health in the most expedient and most impactful ways is multitiered, with basic or fundamental research, translational research, interventional studies, and retrospective research often occurring simultaneously. There should be no “single lane” of research and one type of research does not preclude the other.

Too often, we fall short in one of these lanes. While we have achieved many moonshots in obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine, we have tended not to place a high priority on basic research, which can provide a strong understanding of the biology of major diseases and conditions affecting women and their offspring. When conducted with proper commitment and funding, such research can lead to biologically directed therapy.

Within our specialty, research on how we can effectively prevent preterm birth, prematurity, and preeclampsia has taken a long road, with various types of therapies being tried, but none being overwhelmingly effective — with an ongoing need for more basic or fundamental research. Nevertheless, we can benefit and gain great insights from retrospective and interventional studies associated with clinical therapies used to treat premature labor and preeclampsia when these therapies have an unanticipated and important secondary benefit.

This month our Master Class is focused on the neuroprotection of prematurity. Magnesium sulfate is a valuable tool for the treatment of both premature labor and preeclampsia, and more recently, also for neuroprotection of the fetus. Interestingly, this use stemmed from researchers looking retrospectively at outcomes in women who received the compound for other reasons. It took many years for researchers to prove its neuroprotective value through interventional trials, while researchers simultaneously strove to understand on a basic biologic level how magnesium sulfate works to prevent outcomes such as cerebral palsy.

Basic research underway today continues to improve our understanding of its precise mechanisms of action. Combined with other tiers of research — including more interventional studies and more translational research — we can improve its utility for the neuroprotection of prematurity. Alternatively, ongoing research may lead to different, even more effective treatments.

Our guest author is Irina Burd, MD, PhD, Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.* Dr. Burd is also a physician-scientist. She recounts the important story of magnesium sulfate and what is currently known about its biologic plausibility in neuroprotection — including through her own studies – as well as what may be coming in the future.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Magnesium Sulfate for Fetal Neuroprotection in Preterm Birth

Without a doubt, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) given before anticipated preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy. It is a valuable tool for fetal neuroprotection at a time when there are no proven alternatives. Yet without the persistent research that occurred over more than 20 years, it may not have won the endorsement of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists in 2010 and worked its way into routine practice.

Its history is worthy of reflection. It took years of observational trials (not all of which showed neuroprotective effects), six randomized controlled trials (none of which met their primary endpoint), three meta-analyses, and a Cochrane Database Systematic Review to arrive at the conclusion that antenatal magnesium sulfate therapy given to women at risk of preterm birth has definitive neuroprotective benefit.

This history also holds lessons for our specialty given the dearth of drugs approved for use in pregnancy and the recent withdrawal from the market of Makena — one of only nine drugs to ever be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in pregnancy — after a second trial showed lack of benefit in preventing recurrent preterm birth. The story of MgSO4 tells us it’s acceptable to have major stumbling blocks: At one point, MgSO4 was considered to be not only not helpful, but harmful, causing neonatal death. Further research disproved this initial finding.

Moreover, the MgSO4 story is one that remains unfinished, as my laboratory and other researchers work to better understand its biologic plausibility and to discover additional neuroprotective agents for anticipated preterm birth that may further reduce the risk of cerebral palsy. This leading cause of chronic childhood disability is estimated by the United Cerebral Palsy Foundation to affect approximately 800,000 people in the United States.

Origins and Biologic Plausibility

The MgSO4 story is rooted in the late seventeenth century discovery by physician Nehemiah Grew that the compound was the key component of the then-famous medicinal spring waters in Epsom, England.1 MgSO4 was first used for eclampsia in 1906,2 and was first reported in the American literature for eclampsia in 1925.3 In 1959, its effect as a tocolytic agent was reported.4

More than 30 years later, in 1995, an observational study coauthored by Karin B. Nelson, MD, and Judith K. Grether, PhD of the National Institutes of Health, showed a reduced risk of cerebral palsy in very-low-birth-weight infants (VLBW).5 The report marked a turning point in research interest on neuroprotection for anticipated preterm birth.

The precise molecular mechanisms of action of MgSO4 for neuroprotection are still not well understood. However, research findings from the University of Maryland and other institutions have provided biologic plausibility for its use to prevent cerebral palsy. Our current thinking is that it involves the prevention of periventricular white matter injury and/or the prevention of oxidative stress and a neuronal injury mechanism called excitotoxicity.

Periventricular white matter injury involving injury to preoligodendrocytes before 32 weeks’ gestation is the most prevalent injury seen in cerebral palsy; preoligodendrocytes are precursors of myelinating oligodendrocytes, which constitute a major glial population in the white matter. Our research in a mouse model demonstrated that the intrauterine inflammation frequently associated with preterm birth can lead to neuronal injury as well as white matter damage, and that MgSO4 may ameliorate both.6,7

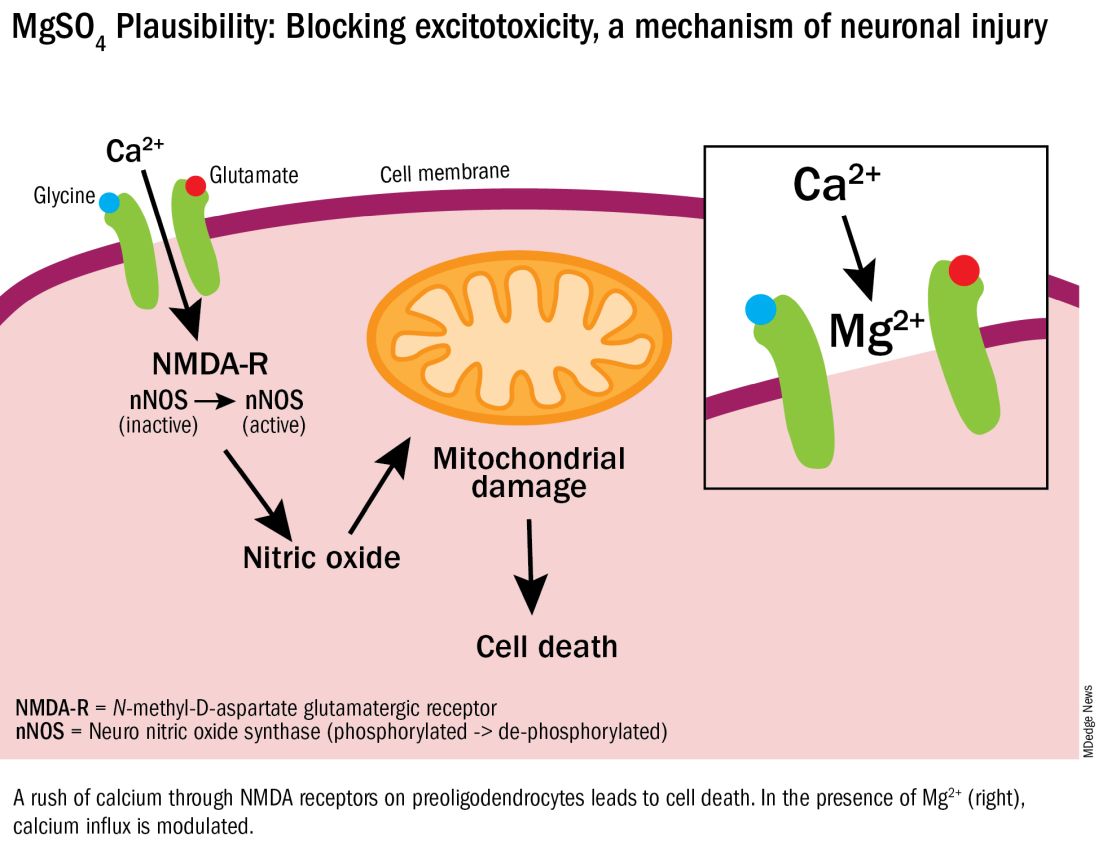

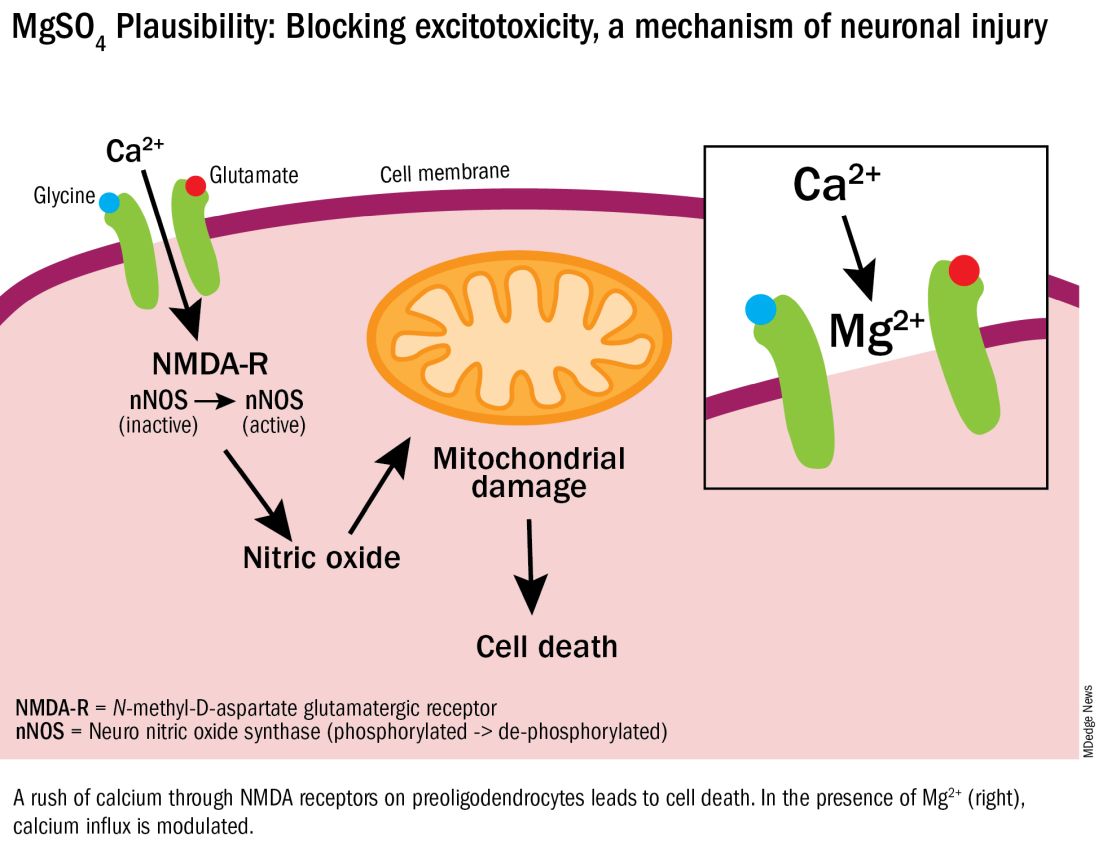

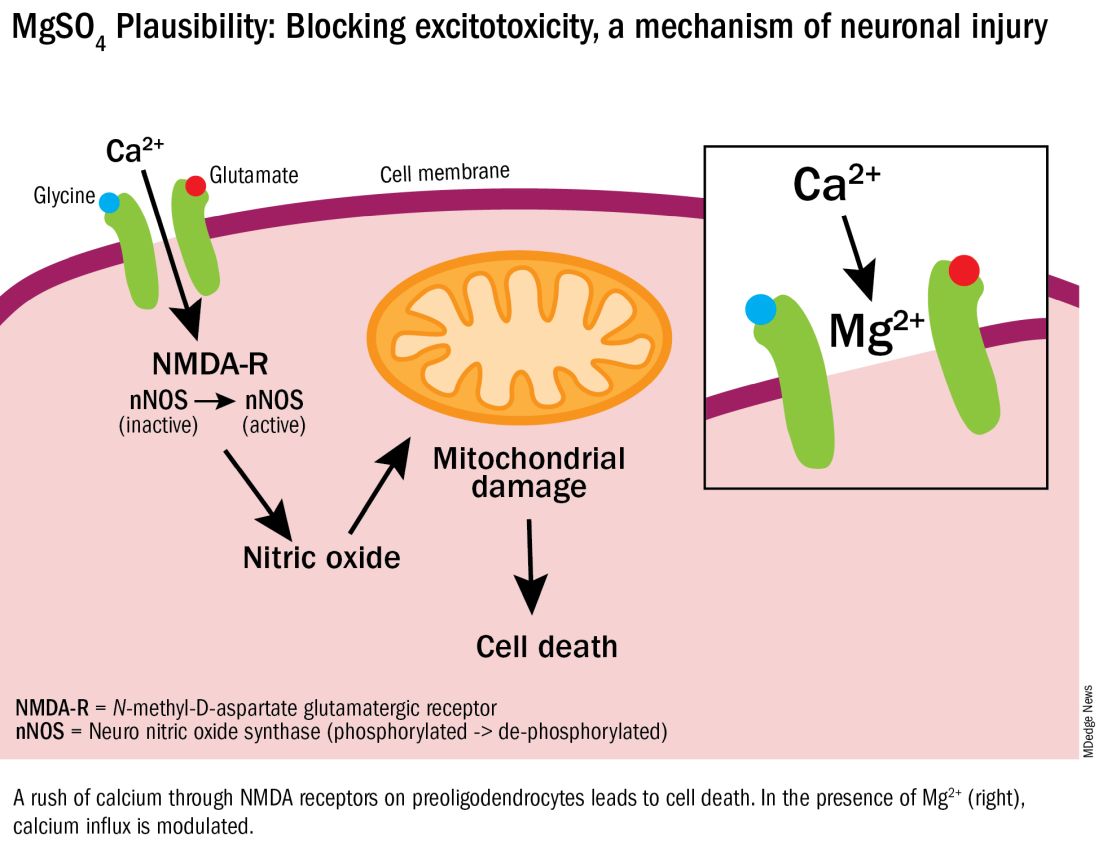

Excitotoxicity results from excessive stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptors on preoligodendrocytes and a rush of calcium through the voltage-gated channels. This calcium influx leads to the production of nitric oxide, oxidative stress, and subsequent mitochondrial damage and cell death. As a bivalent ion, MgSO4 sits in the voltage-gated channels of the NMDA receptors and reduces glutamatergic signaling, thus serving as a calcium antagonist and modulating calcium influx (See Figure).

In vitro research in our laboratory has also shown that MgSO4 may dampen inflammatory reactions driven by intrauterine infections, which, like preterm birth, increase the risk of cerebral palsy and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.8 MgSO4 appears to do so by blocking the voltage-gated P2X7 receptor in umbilical vein endothelial cells, thus blocking endothelial secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)–1beta. Much more research is needed to determine whether MgSO4 could help prevent cerebral palsy through this mechanism.

The Long Route of Research

The 1995 Nelson-Grether study compared VLBW (< 1500 g) infants who survived and developed moderate/severe cerebral palsy within 3 years to randomly selected VLBW controls with respect to whether their mothers had received MgSO4 to prevent seizures in preeclampsia or as a tocolytic agent.5 In a population of more than 155,000 children born between 1983 and 1985, in utero exposure to MgSO4 was reported in 7.1% of 42 VLBW infants with cerebral palsy and 36% of 75 VLBW controls (odds ratio [OR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.05-0.51). In women without preeclampsia the OR increased to 0.25.

This motivating study had been preceded by several observational studies showing that infants born to women with preeclampsia who received MgSO4 had significantly lower risks of developing intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH). In one of these studies, published in 1992, Karl C. Kuban, MD, and coauthors reported that “maternal receipt of magnesium sulfate was associated with diminished risk of GMH-IVH even in those babies born to mothers who apparently did not have preeclampsia.”9

In the several years following the 1995 Nelson-Grether study, several other case-control/observational studies were reported, with conflicting conclusions, and investigators around the world began designing and conducting needed randomized controlled trials.

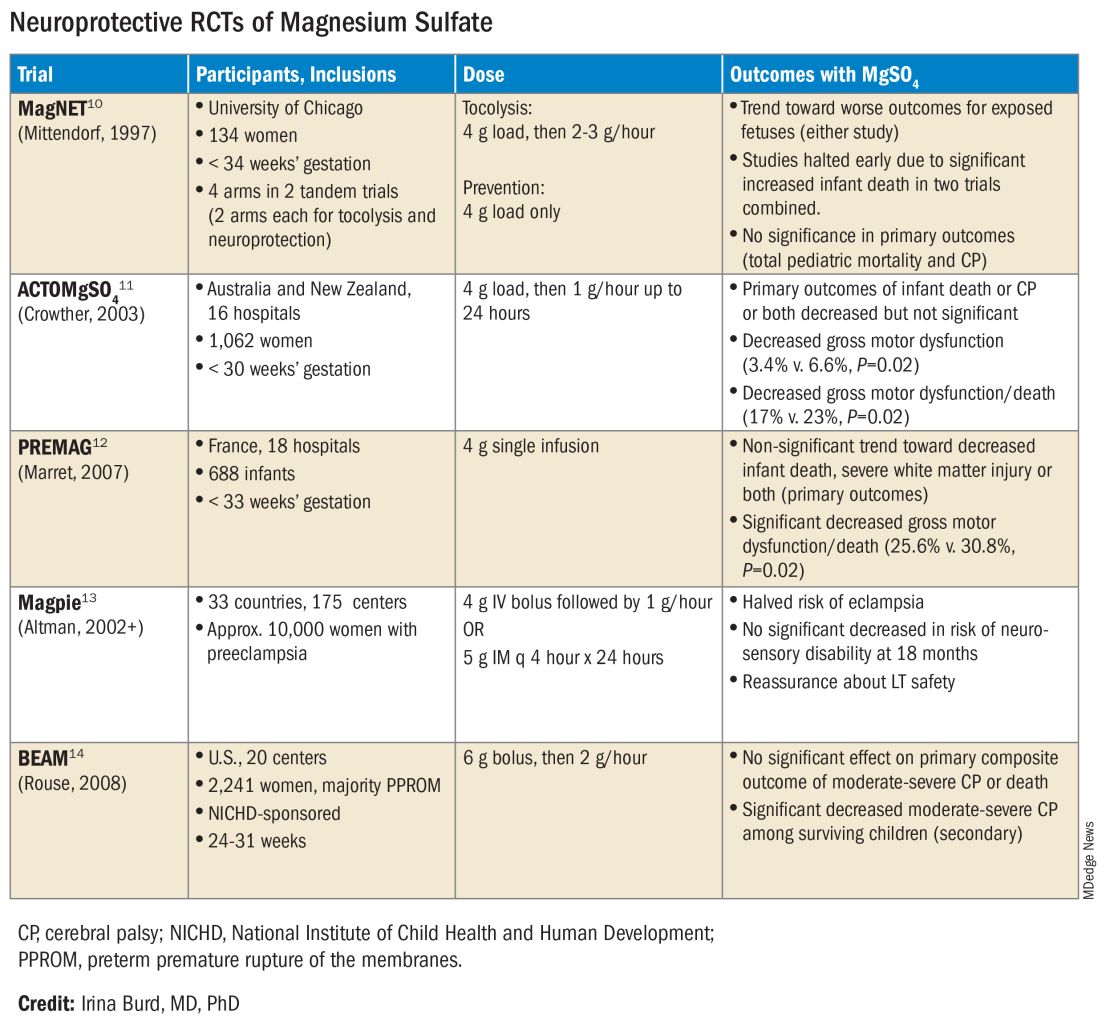

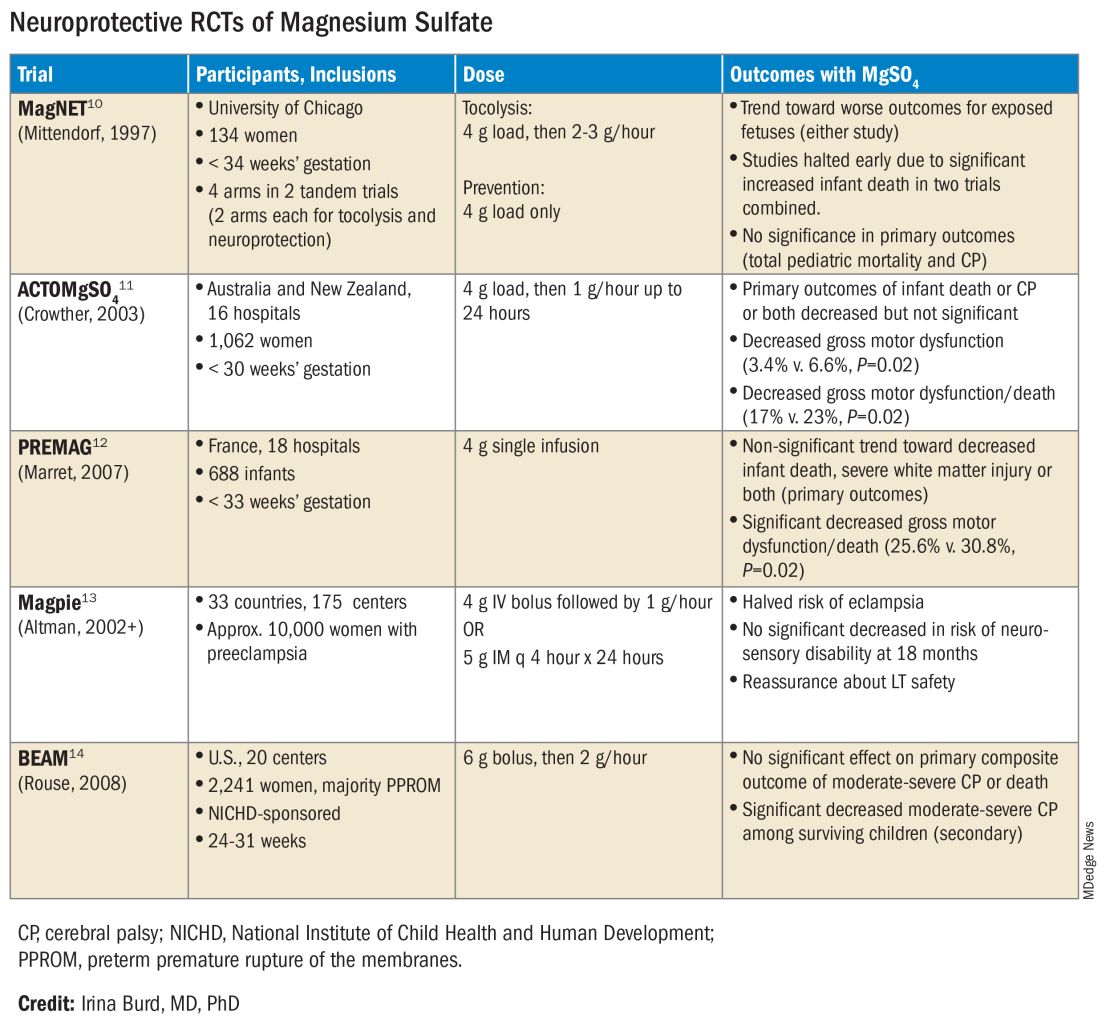

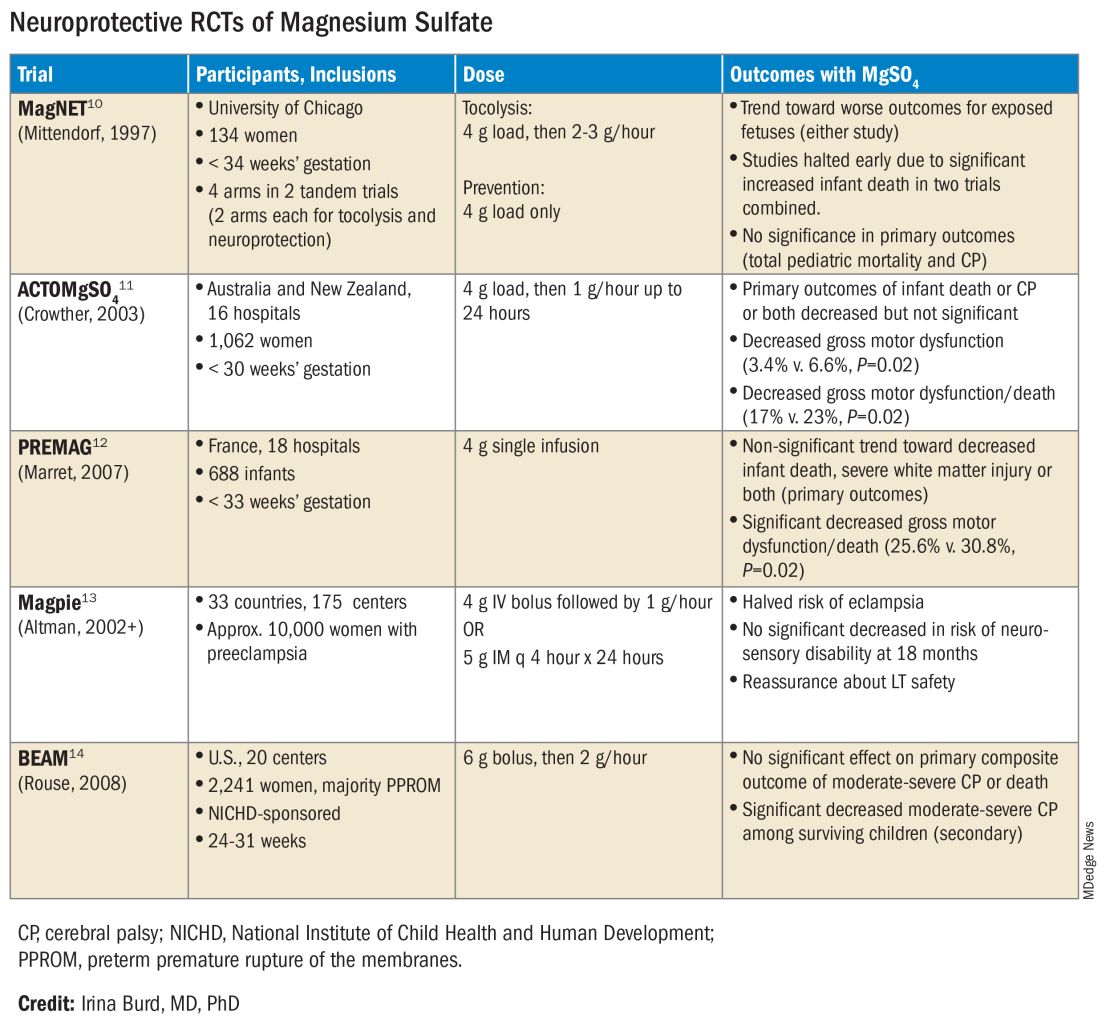

The six published randomized controlled trials looking at MgSO4 and neuroprotection varied in their inclusion and exclusion criteria, their recruitment and enrollment style, the gestational ages for MgSO4 administration, loading and maintenance doses, how cerebral palsy or neuroprotection was assessed, and other factors (See Table for RCT characteristics and main outcomes).10-14 One of the trials aimed primarily at evaluating the efficacy of MgSO4 for preventing preeclampsia.

Again, none of the randomized controlled trials demonstrated statistical significance for their primary outcomes or concluded that there was a significant neuroprotective effect for cerebral palsy. Rather, most suggested benefit through secondary analyses. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, research that proceeded after the first published randomized controlled trial — the Magnesium and Neurologic Endpoints (MAGnet) trial — was suspended early when an interim analysis showed a significantly increased risk of mortality in MgSO4-exposed fetuses. All told, it wasn’t until researchers obtained unpublished data and conducted meta-analyses and systematic reviews that a significant effect of MgSO4 on cerebral palsy could be seen.

The three systematic reviews and the Cochrane review, each of which used slightly different methodologies, were published in rapid succession in 2009. One review calculated a relative risk of cerebral palsy of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.55-0.91) — and a relative risk for the combined outcome of death and cerebral palsy at 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98) — when women at risk of preterm birth were given MgSO4.15 The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of cerebral palsy was 63, investigators determined, and the NNT to prevent one case of cerebral palsy or infant death was 44.

Another review estimated the NNT for prevention of one case of cerebral palsy at 52 when MgSO4 is given at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, and similarly concluded that MgSO4 is associated with a significantly “reduced risk of moderate/severe CP and substantial gross motor dysfunction without any statistically significant effect on the risk of total pediatric mortality.”16

A third review, from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU), estimated an NNT of 46 to prevent one case of cerebral palsy in infants exposed to MgSO4 before 30 weeks, and an NNT of 56 when exposure occurs before 32-34 weeks.17

The Cochrane Review, meanwhile, reported a relative reduction in the risk of cerebral palsy of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.54-0.87) when antenatal MgSO4 is given at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, as well as a significant reduction in the rate of substantial gross motor dysfunction (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44-0.85).18 The NNT to avoid one case of cerebral palsy, researchers reported, was 63.

Moving Forward

The NNTs calculated in these reviews — ranging from 44 to 63 — are convincing, and are comparable with evidence-based medicine data for prevention of other common diseases.19 For instance, the NNT for a life saved when aspirin is given immediately after a heart attack is 42. Statins given for 5 years in people with known heart disease have an NNT of 83 to save one life, an NNT of 39 to prevent one nonfatal heart attack, and an NNT of 125 to prevent one stroke. For oral anticoagulants used in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation for primary stroke prevention, the NNTs to prevent one stroke, and one death, are 22 and 42, respectively.19

In its 2010 Committee Opinion on Magnesium Sulfate Before Anticipated Preterm Birth for Neuroprotection (reaffirmed in 2020), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists left it to institutions to develop their own guidelines “regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in accordance with one of the larger trials.”20

Not surprisingly, most if not all hospitals have chosen a higher dose of MgSO4 administered up to 31 weeks’ gestation in keeping with the protocols employed in the NICHD-sponsored BEAM trial (See Table).

The hope moving forward is to expand treatment options for neuroprotection in cases of imminent preterm birth. Researchers have been assessing the ability of melatonin to provide neuroprotection in cases of growth restriction and neonatal asphyxia. Melatonin has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and is known to mediate neuronal generation and synaptic plasticity.21

N-acetyl-L-cysteine is another potential neuroprotective agent. It acts as an antioxidant, a precursor to glutathione, and a modulator of the glutamate system and has been studied as a neuroprotective agent in cases of maternal chorioamnionitis.21 Both melatonin and N-acetyl-L-cysteine are regarded as safe in pregnancy, but much more clinical study is needed to prove their neuroprotective potential when given shortly before birth or earlier.

Dr. Burd is the Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Clio Med. 1984;19(1-2):1-21.

2. Medicinsk Rev. (Bergen) 1906;32:264-272.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1390-1391.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78(1):27-32.

5. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):263-269.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):279.e1-279.e8.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):292.e1-292.e9.

8. Pediatr Res. 2020;87(3):463-471.

9. J Child Neurol. 1992;7(1):70-76.

10. Lancet. 1997;350:1517-1518.

11. JAMA. 2003;290:2669-2676.

12. BJOG. 2007;114(3):310-318.

13. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1877-1890.

14. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:895-905.

15. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1327-1333.

16. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):595-609.

17. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:354-364.