User login

Should BP Guidelines Be Sex-Specific?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

This is Dr. JoAnn Manson, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Current BP guidelines are sex-agnostic.

This study was done in the large-scale nationally representative NHANES cohort. It included more than 53,000 US men and women. The average age was about 45 years, with an average duration of follow-up of 9.5 years. During that time, about 2400 cardiovascular (CVD) deaths were documented at baseline. The BP was measured three times, and the results were averaged. About 20% of the cohort were taking antihypertensive medications, and 80% were not.

Sex differences were observed in the association between BP and CVD mortality. The systolic BP associated with the lowest risk for CVD death was 110-119 mm Hg in men and 100-109 mm Hg in women. In men, however, compared with a reference category of systolic BP of 100-109 mm Hg, the risk for CVD death began to increase significantly at a systolic BP ≥ 160 mm Hg, at which point, the hazard ratio was 1.76, or 76% higher risk.

In women, the risk for CVD death began to increase significantly at a lower threshold. Compared with a reference category of systolic BP of 100-109 mm Hg, women whose systolic BP was 130-139 mm Hg had a significant 61% increase in CVD death, and among those with a systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg, the risk was increased by 75%. With a systolic BP ≥ 160 mm Hg, CVD deaths among women were more than doubled, with a hazard ratio of 2.13.

Overall, these findings suggest sex differences, with women having an increased risk for CVD death beginning at a lower elevation of their systolic BP. For diastolic BP, both men and women showed the typical U-shaped curve and the diastolic BP associated with the lowest risk for CVD death was 70-80 mm Hg.

If these findings can be replicated with additional research and other large-scale cohort studies, and randomized trials show differences in lowering BP, then sex-specific BP guidelines could have advantages and should be seriously considered. Furthermore, some of the CVD risk scores and risk modeling should perhaps use sex-specific blood pressure thresholds.Dr. Manson received study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

This is Dr. JoAnn Manson, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Current BP guidelines are sex-agnostic.

This study was done in the large-scale nationally representative NHANES cohort. It included more than 53,000 US men and women. The average age was about 45 years, with an average duration of follow-up of 9.5 years. During that time, about 2400 cardiovascular (CVD) deaths were documented at baseline. The BP was measured three times, and the results were averaged. About 20% of the cohort were taking antihypertensive medications, and 80% were not.

Sex differences were observed in the association between BP and CVD mortality. The systolic BP associated with the lowest risk for CVD death was 110-119 mm Hg in men and 100-109 mm Hg in women. In men, however, compared with a reference category of systolic BP of 100-109 mm Hg, the risk for CVD death began to increase significantly at a systolic BP ≥ 160 mm Hg, at which point, the hazard ratio was 1.76, or 76% higher risk.

In women, the risk for CVD death began to increase significantly at a lower threshold. Compared with a reference category of systolic BP of 100-109 mm Hg, women whose systolic BP was 130-139 mm Hg had a significant 61% increase in CVD death, and among those with a systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg, the risk was increased by 75%. With a systolic BP ≥ 160 mm Hg, CVD deaths among women were more than doubled, with a hazard ratio of 2.13.

Overall, these findings suggest sex differences, with women having an increased risk for CVD death beginning at a lower elevation of their systolic BP. For diastolic BP, both men and women showed the typical U-shaped curve and the diastolic BP associated with the lowest risk for CVD death was 70-80 mm Hg.

If these findings can be replicated with additional research and other large-scale cohort studies, and randomized trials show differences in lowering BP, then sex-specific BP guidelines could have advantages and should be seriously considered. Furthermore, some of the CVD risk scores and risk modeling should perhaps use sex-specific blood pressure thresholds.Dr. Manson received study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

This is Dr. JoAnn Manson, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Current BP guidelines are sex-agnostic.

This study was done in the large-scale nationally representative NHANES cohort. It included more than 53,000 US men and women. The average age was about 45 years, with an average duration of follow-up of 9.5 years. During that time, about 2400 cardiovascular (CVD) deaths were documented at baseline. The BP was measured three times, and the results were averaged. About 20% of the cohort were taking antihypertensive medications, and 80% were not.

Sex differences were observed in the association between BP and CVD mortality. The systolic BP associated with the lowest risk for CVD death was 110-119 mm Hg in men and 100-109 mm Hg in women. In men, however, compared with a reference category of systolic BP of 100-109 mm Hg, the risk for CVD death began to increase significantly at a systolic BP ≥ 160 mm Hg, at which point, the hazard ratio was 1.76, or 76% higher risk.

In women, the risk for CVD death began to increase significantly at a lower threshold. Compared with a reference category of systolic BP of 100-109 mm Hg, women whose systolic BP was 130-139 mm Hg had a significant 61% increase in CVD death, and among those with a systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg, the risk was increased by 75%. With a systolic BP ≥ 160 mm Hg, CVD deaths among women were more than doubled, with a hazard ratio of 2.13.

Overall, these findings suggest sex differences, with women having an increased risk for CVD death beginning at a lower elevation of their systolic BP. For diastolic BP, both men and women showed the typical U-shaped curve and the diastolic BP associated with the lowest risk for CVD death was 70-80 mm Hg.

If these findings can be replicated with additional research and other large-scale cohort studies, and randomized trials show differences in lowering BP, then sex-specific BP guidelines could have advantages and should be seriously considered. Furthermore, some of the CVD risk scores and risk modeling should perhaps use sex-specific blood pressure thresholds.Dr. Manson received study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Is It Time to Air Grievances?

‘Twas the night before Festivus and all through the house, everyone was griping.

In case you’ve only been watching Friends reruns lately, Festivus is a holiday that originated 25 years ago in the last season of Seinfeld. George’s father created it as an alternative to Christmas hype. In addition to an aluminum pole, the holiday features the annual airing of grievances, when one is encouraged to voice complaints. Aluminum poles haven’t replaced Christmas trees, but the spirit of Festivus is still with us in the widespread airing of grievances in 2023.

Complaining isn’t just a post-pandemic problem. Hector spends quite a bit of time complaining about Paris in the Iliad. That was a few pandemics ago. And repining is ubiquitous in literature — as human as walking on two limbs it seems. Ostensibly, we complain to effect change: Something is wrong and we expect it to be different. But that’s not the whole story. No one believes the weather will improve or the Patriots will play better because we complain about them. So why do we bother?

Even if nothing changes on the outside, it does seem to alter our internal state, serving a healthy psychological function. Putting to words what is aggravating can have the same benefit of deep breathing. We describe it as “getting something off our chest” because that’s what it feels like. We feel unburdened just by saying it out loud. Think about the last time you complained: Cranky staff, prior auths, Medicare, disrespectful patients, many of your colleagues will nod in agreement, validating your feelings and making you feel less isolated.

There are also maladaptive reasons for whining. It’s obviously an elementary way to get attention or to remove responsibility. It can also be a political weapon (office politics included). It’s such a potent way to connect that it’s used to build alliances and clout. “Washington is doing a great job,” said no candidate ever. No, if you want to get people on your side, find something irritating and complain to everyone how annoying it is. This solidifies “us” versus “them,” which can harm organizations and families alike.

Yet, eliminating all complaints is neither feasible, nor probably advisable. You could try to make your office a complaint-free zone, but the likely result would be to push any griping to the remote corners where you can no longer hear them. These criticisms might have uncovered missed opportunities, identify problems, and even improve cohesion if done in a safe and transparent setting. If they are left unaddressed or if the underlying culture isn’t sound, then they can propagate and lead to factions that harm productivity.

Griping is as much part of the holiday season as jingle bells and jelly donuts. I don’t believe complaining is up now because people were grumpier in 2023. Rather I think people just craved connection more than ever. So join in: Traffic after the time change, Tesla service, (super) late patients, prior auths, perioral dermatitis, post-COVID telogen effluvium.

I feel better.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X (formerly Twitter). Write to him at [email protected].

‘Twas the night before Festivus and all through the house, everyone was griping.

In case you’ve only been watching Friends reruns lately, Festivus is a holiday that originated 25 years ago in the last season of Seinfeld. George’s father created it as an alternative to Christmas hype. In addition to an aluminum pole, the holiday features the annual airing of grievances, when one is encouraged to voice complaints. Aluminum poles haven’t replaced Christmas trees, but the spirit of Festivus is still with us in the widespread airing of grievances in 2023.

Complaining isn’t just a post-pandemic problem. Hector spends quite a bit of time complaining about Paris in the Iliad. That was a few pandemics ago. And repining is ubiquitous in literature — as human as walking on two limbs it seems. Ostensibly, we complain to effect change: Something is wrong and we expect it to be different. But that’s not the whole story. No one believes the weather will improve or the Patriots will play better because we complain about them. So why do we bother?

Even if nothing changes on the outside, it does seem to alter our internal state, serving a healthy psychological function. Putting to words what is aggravating can have the same benefit of deep breathing. We describe it as “getting something off our chest” because that’s what it feels like. We feel unburdened just by saying it out loud. Think about the last time you complained: Cranky staff, prior auths, Medicare, disrespectful patients, many of your colleagues will nod in agreement, validating your feelings and making you feel less isolated.

There are also maladaptive reasons for whining. It’s obviously an elementary way to get attention or to remove responsibility. It can also be a political weapon (office politics included). It’s such a potent way to connect that it’s used to build alliances and clout. “Washington is doing a great job,” said no candidate ever. No, if you want to get people on your side, find something irritating and complain to everyone how annoying it is. This solidifies “us” versus “them,” which can harm organizations and families alike.

Yet, eliminating all complaints is neither feasible, nor probably advisable. You could try to make your office a complaint-free zone, but the likely result would be to push any griping to the remote corners where you can no longer hear them. These criticisms might have uncovered missed opportunities, identify problems, and even improve cohesion if done in a safe and transparent setting. If they are left unaddressed or if the underlying culture isn’t sound, then they can propagate and lead to factions that harm productivity.

Griping is as much part of the holiday season as jingle bells and jelly donuts. I don’t believe complaining is up now because people were grumpier in 2023. Rather I think people just craved connection more than ever. So join in: Traffic after the time change, Tesla service, (super) late patients, prior auths, perioral dermatitis, post-COVID telogen effluvium.

I feel better.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X (formerly Twitter). Write to him at [email protected].

‘Twas the night before Festivus and all through the house, everyone was griping.

In case you’ve only been watching Friends reruns lately, Festivus is a holiday that originated 25 years ago in the last season of Seinfeld. George’s father created it as an alternative to Christmas hype. In addition to an aluminum pole, the holiday features the annual airing of grievances, when one is encouraged to voice complaints. Aluminum poles haven’t replaced Christmas trees, but the spirit of Festivus is still with us in the widespread airing of grievances in 2023.

Complaining isn’t just a post-pandemic problem. Hector spends quite a bit of time complaining about Paris in the Iliad. That was a few pandemics ago. And repining is ubiquitous in literature — as human as walking on two limbs it seems. Ostensibly, we complain to effect change: Something is wrong and we expect it to be different. But that’s not the whole story. No one believes the weather will improve or the Patriots will play better because we complain about them. So why do we bother?

Even if nothing changes on the outside, it does seem to alter our internal state, serving a healthy psychological function. Putting to words what is aggravating can have the same benefit of deep breathing. We describe it as “getting something off our chest” because that’s what it feels like. We feel unburdened just by saying it out loud. Think about the last time you complained: Cranky staff, prior auths, Medicare, disrespectful patients, many of your colleagues will nod in agreement, validating your feelings and making you feel less isolated.

There are also maladaptive reasons for whining. It’s obviously an elementary way to get attention or to remove responsibility. It can also be a political weapon (office politics included). It’s such a potent way to connect that it’s used to build alliances and clout. “Washington is doing a great job,” said no candidate ever. No, if you want to get people on your side, find something irritating and complain to everyone how annoying it is. This solidifies “us” versus “them,” which can harm organizations and families alike.

Yet, eliminating all complaints is neither feasible, nor probably advisable. You could try to make your office a complaint-free zone, but the likely result would be to push any griping to the remote corners where you can no longer hear them. These criticisms might have uncovered missed opportunities, identify problems, and even improve cohesion if done in a safe and transparent setting. If they are left unaddressed or if the underlying culture isn’t sound, then they can propagate and lead to factions that harm productivity.

Griping is as much part of the holiday season as jingle bells and jelly donuts. I don’t believe complaining is up now because people were grumpier in 2023. Rather I think people just craved connection more than ever. So join in: Traffic after the time change, Tesla service, (super) late patients, prior auths, perioral dermatitis, post-COVID telogen effluvium.

I feel better.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X (formerly Twitter). Write to him at [email protected].

Sodium deoxycholate and triamcinolone: A good mix?

In September 2023, Goldman et al. published a communication in Dermatologic Surgery describing their use of subcutaneous sodium deoxycholate injection (SDOC), with or without triamcinolone acetonide, for reduction of submental fat..

As they note, “patients experience a variable degree of edema and discomfort following subcutaneous injection,” of SDOC, something that I and others have also observed in our practices.

In their double-blind study of 20 patients with a baseline Clinician-Reported Submental Fat Rating Scale of 2 or 3 out of 4, 5 patients were randomized to receive SDOC as recommended in the label, while 15 received SDOC plus triamcinolone. In the latter group, 2 mL of SDOC was mixed with 0.5 mL of 40 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetate, then administered in up to 50 injections in the submentum spaced 1.0 cm apart at 0.25 mL per injection. Three treatments were administered 1 month apart.

For both groups, volumes between 5 mL and 8 mL per treatment were delivered. There were no significant differences in efficacy 30, 60, and 90 days after the final injection between the two groups. However, at day 180, the group that received only SDOC had a significantly greater reduction in submental fat, which the authors wrote indicated that the addition of triamcinolone “may mildly diminish the fat reduction effects” at that time point.

Subcutaneous SDOC (deoxycholic acid) injections for reduction of submental fullness was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for improving the appearance of moderate to severe convexity or fullness associated with submental fat in adults. (I was involved in the clinical trials.) We found that in the trial, for optimal efficacy, most patients require two to four treatments spread at least a month apart, with patients who had larger treatment areas requiring up to six treatments.

While the clinical trial treatments were spaced 4 weeks apart, post approval, we found that patients would sometimes report further efficacy even 2-3 months post injection. Since not everyone wants to go around with edema every month for 2-4 consecutive months, spacing the treatments farther apart allows patients more time to heal and coordinate the recovery appearance around their work and social schedules.

In my practice, very rarely have we seen minimal to moderate prolonged edema, particularly in younger patients, beyond 1 month post injection. Most people have the most noticeable edema — the “bull-frog” appearance — for the first 1-3 days, with some minor fullness that appears to be almost back to baseline at 1 week. In some of these patients with prolonged submental fullness, it looks fuller than it appeared pretreatment even months afterwards.

While rare, like the study authors, I have found intralesional triamcinolone to be helpful at reducing this persistent fullness should it occur. It is likely to be reducing any persistent inflammation or posttreatment fibrosis in these patients.

Unlike the study authors, I do not combine SDOC and triamcinolone injections at the time of treatment. Rather, I consider injecting triamcinolone if submental fullness is greater than at baseline or edema persists after SDOC treatment. It is rare that I’ve had to do this, as most cases self-resolve, but I have used triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, up to 1cc total, injected 6-8 weeks apart one to three times to the affected area and found it to be effective if fullness has persisted beyond 6 months. Liposuction may also be an option, if needed, if fullness/edema persists.

Overall, SDOC is an effective treatment for small pockets of subcutaneous fat. Approved for submental fullness, it is now sometimes used off-label for other parts of the body, such as bra fat, small pockets of the abdomen, and lipomas. While some inflammation after treatment is expected — and desired — to achieve an effective outcome of fat apoptosis, intralesional triamcinolone is an interesting tool to utilize should inflammation or posttreatment fullness persist.

Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, California. Write to her at [email protected]. She was an investigator in clinical trials of Kybella.

In September 2023, Goldman et al. published a communication in Dermatologic Surgery describing their use of subcutaneous sodium deoxycholate injection (SDOC), with or without triamcinolone acetonide, for reduction of submental fat..

As they note, “patients experience a variable degree of edema and discomfort following subcutaneous injection,” of SDOC, something that I and others have also observed in our practices.

In their double-blind study of 20 patients with a baseline Clinician-Reported Submental Fat Rating Scale of 2 or 3 out of 4, 5 patients were randomized to receive SDOC as recommended in the label, while 15 received SDOC plus triamcinolone. In the latter group, 2 mL of SDOC was mixed with 0.5 mL of 40 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetate, then administered in up to 50 injections in the submentum spaced 1.0 cm apart at 0.25 mL per injection. Three treatments were administered 1 month apart.

For both groups, volumes between 5 mL and 8 mL per treatment were delivered. There were no significant differences in efficacy 30, 60, and 90 days after the final injection between the two groups. However, at day 180, the group that received only SDOC had a significantly greater reduction in submental fat, which the authors wrote indicated that the addition of triamcinolone “may mildly diminish the fat reduction effects” at that time point.

Subcutaneous SDOC (deoxycholic acid) injections for reduction of submental fullness was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for improving the appearance of moderate to severe convexity or fullness associated with submental fat in adults. (I was involved in the clinical trials.) We found that in the trial, for optimal efficacy, most patients require two to four treatments spread at least a month apart, with patients who had larger treatment areas requiring up to six treatments.

While the clinical trial treatments were spaced 4 weeks apart, post approval, we found that patients would sometimes report further efficacy even 2-3 months post injection. Since not everyone wants to go around with edema every month for 2-4 consecutive months, spacing the treatments farther apart allows patients more time to heal and coordinate the recovery appearance around their work and social schedules.

In my practice, very rarely have we seen minimal to moderate prolonged edema, particularly in younger patients, beyond 1 month post injection. Most people have the most noticeable edema — the “bull-frog” appearance — for the first 1-3 days, with some minor fullness that appears to be almost back to baseline at 1 week. In some of these patients with prolonged submental fullness, it looks fuller than it appeared pretreatment even months afterwards.

While rare, like the study authors, I have found intralesional triamcinolone to be helpful at reducing this persistent fullness should it occur. It is likely to be reducing any persistent inflammation or posttreatment fibrosis in these patients.

Unlike the study authors, I do not combine SDOC and triamcinolone injections at the time of treatment. Rather, I consider injecting triamcinolone if submental fullness is greater than at baseline or edema persists after SDOC treatment. It is rare that I’ve had to do this, as most cases self-resolve, but I have used triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, up to 1cc total, injected 6-8 weeks apart one to three times to the affected area and found it to be effective if fullness has persisted beyond 6 months. Liposuction may also be an option, if needed, if fullness/edema persists.

Overall, SDOC is an effective treatment for small pockets of subcutaneous fat. Approved for submental fullness, it is now sometimes used off-label for other parts of the body, such as bra fat, small pockets of the abdomen, and lipomas. While some inflammation after treatment is expected — and desired — to achieve an effective outcome of fat apoptosis, intralesional triamcinolone is an interesting tool to utilize should inflammation or posttreatment fullness persist.

Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, California. Write to her at [email protected]. She was an investigator in clinical trials of Kybella.

In September 2023, Goldman et al. published a communication in Dermatologic Surgery describing their use of subcutaneous sodium deoxycholate injection (SDOC), with or without triamcinolone acetonide, for reduction of submental fat..

As they note, “patients experience a variable degree of edema and discomfort following subcutaneous injection,” of SDOC, something that I and others have also observed in our practices.

In their double-blind study of 20 patients with a baseline Clinician-Reported Submental Fat Rating Scale of 2 or 3 out of 4, 5 patients were randomized to receive SDOC as recommended in the label, while 15 received SDOC plus triamcinolone. In the latter group, 2 mL of SDOC was mixed with 0.5 mL of 40 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetate, then administered in up to 50 injections in the submentum spaced 1.0 cm apart at 0.25 mL per injection. Three treatments were administered 1 month apart.

For both groups, volumes between 5 mL and 8 mL per treatment were delivered. There were no significant differences in efficacy 30, 60, and 90 days after the final injection between the two groups. However, at day 180, the group that received only SDOC had a significantly greater reduction in submental fat, which the authors wrote indicated that the addition of triamcinolone “may mildly diminish the fat reduction effects” at that time point.

Subcutaneous SDOC (deoxycholic acid) injections for reduction of submental fullness was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for improving the appearance of moderate to severe convexity or fullness associated with submental fat in adults. (I was involved in the clinical trials.) We found that in the trial, for optimal efficacy, most patients require two to four treatments spread at least a month apart, with patients who had larger treatment areas requiring up to six treatments.

While the clinical trial treatments were spaced 4 weeks apart, post approval, we found that patients would sometimes report further efficacy even 2-3 months post injection. Since not everyone wants to go around with edema every month for 2-4 consecutive months, spacing the treatments farther apart allows patients more time to heal and coordinate the recovery appearance around their work and social schedules.

In my practice, very rarely have we seen minimal to moderate prolonged edema, particularly in younger patients, beyond 1 month post injection. Most people have the most noticeable edema — the “bull-frog” appearance — for the first 1-3 days, with some minor fullness that appears to be almost back to baseline at 1 week. In some of these patients with prolonged submental fullness, it looks fuller than it appeared pretreatment even months afterwards.

While rare, like the study authors, I have found intralesional triamcinolone to be helpful at reducing this persistent fullness should it occur. It is likely to be reducing any persistent inflammation or posttreatment fibrosis in these patients.

Unlike the study authors, I do not combine SDOC and triamcinolone injections at the time of treatment. Rather, I consider injecting triamcinolone if submental fullness is greater than at baseline or edema persists after SDOC treatment. It is rare that I’ve had to do this, as most cases self-resolve, but I have used triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, up to 1cc total, injected 6-8 weeks apart one to three times to the affected area and found it to be effective if fullness has persisted beyond 6 months. Liposuction may also be an option, if needed, if fullness/edema persists.

Overall, SDOC is an effective treatment for small pockets of subcutaneous fat. Approved for submental fullness, it is now sometimes used off-label for other parts of the body, such as bra fat, small pockets of the abdomen, and lipomas. While some inflammation after treatment is expected — and desired — to achieve an effective outcome of fat apoptosis, intralesional triamcinolone is an interesting tool to utilize should inflammation or posttreatment fullness persist.

Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, California. Write to her at [email protected]. She was an investigator in clinical trials of Kybella.

Deciphering the usefulness of probiotics

The idea of the use of probiotics has a history going back more than a century when Russian scientist, Elie Metchnikoff, theorized that lactic acid bacteria may offer health benefits as well as promote longevity. In the early 1900s, intestinal disorders were frequently treated with nonpathogenic bacteria to replace gut microbes.

Today, the market is flooded with products from foods to prescription medications containing probiotics that extol their health benefits. It has been estimated that the global market for probiotics is more than $32 billion dollars annually and is expected to increase 8% per year.

As family doctors, patients come to us with many questions about the use of probiotics. Look online or on store shelves — there are so many types, doses, and brands of probiotics it is hard to decipher which are worth using. We older doctors never received much education about them.

Earlier this year, the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) developed recommendations around the use of probiotics and defined them as “live microbes that have been shown in controlled human studies to impart a health benefit.” Their recommendation is to use the strains that have been shown to be beneficial for the condition they claim to help and have been shown to do so in controlled studies. The dosage advised should be that shown to be useful in studies.

While this is an easy statement to make, it is much less so in clinical practice. The guidelines do a good job breaking down the conditions they help and the strains that have shown to be beneficial for specific conditions.

There have been claims that probiotics have been shown to be beneficial in colorectal cancer. While there have been some studies to show that they can improve markers associated with colorectal cancer, there are no data that probiotics actually do much in terms of prevention. Eating a healthy diet is more helpful here.

One area where probiotics have been shown to be beneficial is in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. This makes sense since we know that antibiotics can kill the “good bacteria” lining the gut wall and probiotics work to replace them. Other conditions where these agents have been shown to be beneficial include radiation-induced diarrhea, acute diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, and colic in breast-fed infants.

The guideline contains good evidence of where and which types of probiotics are useful and it is good to look at the charts in the paper to see the specific strains recommended. It also contains an extensive reference section, and as primary care physicians, it is imperative that we educate ourselves on these agents.

While probiotics are typically sold as supplements, we should not dismiss them summarily. It is easy to do that when supplemental products are marketed and sold unethically with no clinical evidence of benefit. We need to remember that just because something is a supplement doesn’t necessarily mean that it was not studied.

Family physicians need to be able to educate their patients and answer their questions. When we don’t have the answers, we need to find them. Any time our patient doesn’t get good information from us, they will probably go to the Internet and get bad advice from someone else.

There is much ongoing research about the gut microbiome and the bacteria that can be found in the gut. Researchers are looking into the “gut-brain” axis but there is not much good evidence of this link yet. There is no evidence that probiotics can cure Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinsonism. The future may reveal different stories, but for now, we need to follow the evidence we have available.

There are many outlandish claims about what the gut microbiome is responsible for and can do for health. It is easy to have a knee-jerk reaction when anyone brings it up in conversation. We need to arm ourselves with the evidence. We are stewards of the health and safety of our patients.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. She was paid by Pfizer as a consultant on Paxlovid and is the editor in chief of Physician’s Weekly.

The idea of the use of probiotics has a history going back more than a century when Russian scientist, Elie Metchnikoff, theorized that lactic acid bacteria may offer health benefits as well as promote longevity. In the early 1900s, intestinal disorders were frequently treated with nonpathogenic bacteria to replace gut microbes.

Today, the market is flooded with products from foods to prescription medications containing probiotics that extol their health benefits. It has been estimated that the global market for probiotics is more than $32 billion dollars annually and is expected to increase 8% per year.

As family doctors, patients come to us with many questions about the use of probiotics. Look online or on store shelves — there are so many types, doses, and brands of probiotics it is hard to decipher which are worth using. We older doctors never received much education about them.

Earlier this year, the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) developed recommendations around the use of probiotics and defined them as “live microbes that have been shown in controlled human studies to impart a health benefit.” Their recommendation is to use the strains that have been shown to be beneficial for the condition they claim to help and have been shown to do so in controlled studies. The dosage advised should be that shown to be useful in studies.

While this is an easy statement to make, it is much less so in clinical practice. The guidelines do a good job breaking down the conditions they help and the strains that have shown to be beneficial for specific conditions.

There have been claims that probiotics have been shown to be beneficial in colorectal cancer. While there have been some studies to show that they can improve markers associated with colorectal cancer, there are no data that probiotics actually do much in terms of prevention. Eating a healthy diet is more helpful here.

One area where probiotics have been shown to be beneficial is in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. This makes sense since we know that antibiotics can kill the “good bacteria” lining the gut wall and probiotics work to replace them. Other conditions where these agents have been shown to be beneficial include radiation-induced diarrhea, acute diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, and colic in breast-fed infants.

The guideline contains good evidence of where and which types of probiotics are useful and it is good to look at the charts in the paper to see the specific strains recommended. It also contains an extensive reference section, and as primary care physicians, it is imperative that we educate ourselves on these agents.

While probiotics are typically sold as supplements, we should not dismiss them summarily. It is easy to do that when supplemental products are marketed and sold unethically with no clinical evidence of benefit. We need to remember that just because something is a supplement doesn’t necessarily mean that it was not studied.

Family physicians need to be able to educate their patients and answer their questions. When we don’t have the answers, we need to find them. Any time our patient doesn’t get good information from us, they will probably go to the Internet and get bad advice from someone else.

There is much ongoing research about the gut microbiome and the bacteria that can be found in the gut. Researchers are looking into the “gut-brain” axis but there is not much good evidence of this link yet. There is no evidence that probiotics can cure Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinsonism. The future may reveal different stories, but for now, we need to follow the evidence we have available.

There are many outlandish claims about what the gut microbiome is responsible for and can do for health. It is easy to have a knee-jerk reaction when anyone brings it up in conversation. We need to arm ourselves with the evidence. We are stewards of the health and safety of our patients.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. She was paid by Pfizer as a consultant on Paxlovid and is the editor in chief of Physician’s Weekly.

The idea of the use of probiotics has a history going back more than a century when Russian scientist, Elie Metchnikoff, theorized that lactic acid bacteria may offer health benefits as well as promote longevity. In the early 1900s, intestinal disorders were frequently treated with nonpathogenic bacteria to replace gut microbes.

Today, the market is flooded with products from foods to prescription medications containing probiotics that extol their health benefits. It has been estimated that the global market for probiotics is more than $32 billion dollars annually and is expected to increase 8% per year.

As family doctors, patients come to us with many questions about the use of probiotics. Look online or on store shelves — there are so many types, doses, and brands of probiotics it is hard to decipher which are worth using. We older doctors never received much education about them.

Earlier this year, the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) developed recommendations around the use of probiotics and defined them as “live microbes that have been shown in controlled human studies to impart a health benefit.” Their recommendation is to use the strains that have been shown to be beneficial for the condition they claim to help and have been shown to do so in controlled studies. The dosage advised should be that shown to be useful in studies.

While this is an easy statement to make, it is much less so in clinical practice. The guidelines do a good job breaking down the conditions they help and the strains that have shown to be beneficial for specific conditions.

There have been claims that probiotics have been shown to be beneficial in colorectal cancer. While there have been some studies to show that they can improve markers associated with colorectal cancer, there are no data that probiotics actually do much in terms of prevention. Eating a healthy diet is more helpful here.

One area where probiotics have been shown to be beneficial is in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. This makes sense since we know that antibiotics can kill the “good bacteria” lining the gut wall and probiotics work to replace them. Other conditions where these agents have been shown to be beneficial include radiation-induced diarrhea, acute diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, and colic in breast-fed infants.

The guideline contains good evidence of where and which types of probiotics are useful and it is good to look at the charts in the paper to see the specific strains recommended. It also contains an extensive reference section, and as primary care physicians, it is imperative that we educate ourselves on these agents.

While probiotics are typically sold as supplements, we should not dismiss them summarily. It is easy to do that when supplemental products are marketed and sold unethically with no clinical evidence of benefit. We need to remember that just because something is a supplement doesn’t necessarily mean that it was not studied.

Family physicians need to be able to educate their patients and answer their questions. When we don’t have the answers, we need to find them. Any time our patient doesn’t get good information from us, they will probably go to the Internet and get bad advice from someone else.

There is much ongoing research about the gut microbiome and the bacteria that can be found in the gut. Researchers are looking into the “gut-brain” axis but there is not much good evidence of this link yet. There is no evidence that probiotics can cure Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinsonism. The future may reveal different stories, but for now, we need to follow the evidence we have available.

There are many outlandish claims about what the gut microbiome is responsible for and can do for health. It is easy to have a knee-jerk reaction when anyone brings it up in conversation. We need to arm ourselves with the evidence. We are stewards of the health and safety of our patients.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. She was paid by Pfizer as a consultant on Paxlovid and is the editor in chief of Physician’s Weekly.

Sometimes well-intended mental health treatment hurts

We love psychiatry. We love the idea that someone can come to receive care from a physician to alleviate psychological suffering.

Some people experience such severe anguish that they are unable to relate to others. Some are so despondent that they are unable to make decisions. Some are so distressed that their thoughts become inconsistent with reality. We want all those people, and many more, to have access to effective psychiatric care. However, there are reasonable expectations that one should be able to have that a treatment will help, and that appropriate informed consent is given.

One recent article reminded us of this in a particularly poignant way.

The study in question is a recent publication looking at the universal use of psychotherapy for teenagers.1 At face value, we would have certainly considered this to be a benevolent and well-meaning intervention. Anyone who has been a teenager or has talked to one, is aware of the emotional instability punctuated by episodes of intense anxiety or irritability. It is age appropriate for a teenager to question and explore their identity. Teenagers are notoriously impulsive with a deep desire for validating interpersonal relationships. One could continue to list the symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and find a lot of similarity with the condition of transitioning from a child to an adult.

It is thus common sense to consider applying the most established therapy for BPD, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), to teenagers. The basics of DBT would seem to be helpful to anyone but appear particularly appropriate to this population. Mindfulness, the practice of paying attention to your present experience, allows one to realize that they are trapped in past or hypothetical future moments. Emotional regulation provides the tools that offer a frame for our feelings and involves recognizing feelings and understanding what they mean. Interpersonal work allows one to recognize and adapt to the feelings of others, while learning how to have a healthy voice with others. Distress tolerance is the exercise of learning to experience and contain our feelings.

The study looked at about 1,000 young adolescents, around 13 years old across high schools in Sydney, Australia: 598 adolescents were allocated to the intervention, and 566 to the control. The intervention consisted of eight weekly sessions of DBT lasting about 50 minutes. The results were “contrary to predictions.” Participants who received DBT “reported significantly increased total difficulties,” and “significant increases in depression and anxiety.” The effects were worse in males yet significant in both genders. The study concludes with “a reminder that present enthusiasm for universal dissemination of short-term DBT-based group skills training within schools, specifically in early adolescence, is ahead of the research evidence.”

We can’t help but wonder why the outcomes of the study were this way; here are some ideas:

• Society has natural ways of developing interpersonal skills, emotional regulation, and the ability to appreciate the present. Interpersonal skills are consistently fostered and tested in schools. Navigating high school parties, the process of organizing them, and getting invited to them requires significant social dexterity. Rejection from romantic interest, alienation from peers, rewards for accomplishment, and acceptance by other peers are some of the daily emotional obstacles that teenagers face. Being constantly taught by older individuals and scolded by parents is its own course in mindfulness. Those are few of the many natural processes of interpersonal growth that formalized therapy may impede.

• The universal discussion of psychological terms and psychiatric symptoms may not only destigmatize mental illness, but also normalize and possibly even promote it. While punishing or stigmatizing a child for having mental illness is obviously unacceptable and cruel, we do wonder if the compulsory psychotherapy may provide negative effects. Psychotherapies, especially manualized ones, were developed to alleviate mental suffering. It seems possible that this format normalizes pathology.

In 1961, Erving Goffman described the concept of sane people appearing insane in an asylum as “mortification.” In 2023, we have much improved, but have we done something to internalize patterns of suffering and alienation rather than dispel them? They are given forms that explain what the feeling of depression is when they may have never considered it. They are given tools to handle distress, when distress may not be present.

• Many human beings live on a fairly tight rope of suppression and the less adaptive repression. Suppression is the defense mechanism by which individuals make an effort to put distressing thoughts out of conscious awareness. After a difficult breakup a teenager may ask some friends to go out and watch a movie, making efforts to put negative feelings out of conscious awareness until there is an opportunity to cope adaptively with those stressors.

Repression is the defense mechanism by which individuals make an effort to prevent distressing thoughts from entering conscious awareness in the first place. After a difficult breakup a teenager acts like nothing happened. While not particularly adaptive, many people live with significant repression and without particular anguish. It is possible that uncovering all of those repressed and suppressed feelings through the exploratory work of therapy may destabilize individuals from their tight rope.

• A less problematic explanation could also be what was previously referred to as therapeutic regression. In psychoanalytic theory, patients are generally thought to have a compromise formation, a psychological strategy used to reconcile conflicting drives. The compromise formation is the way a patient balances their desires against moral expectations and the realities of the external world. In therapy, that compromise formation can be challenged, leading to therapeutic regression.

By uncovering and confronting deeply rooted feelings, a patient may find that their symptoms temporarily intensify. This may not be a problem, but a necessary step to growth in some patients. It is possible that a program longer than 8 weeks would have overcome a temporary worsening in outcome measures.

While it’s easy to highlight the darker moments in psychiatric history, psychiatry has grown into a field which offers well-accepted and uncontroversially promoted forms of treatment. This is evolution, exemplified by the mere consideration of the universal use of psychotherapy for teenagers. But this raises important questions about the potential unintended consequences of normalizing and formalizing therapy. It prompted us to reflect on whether psychiatric treatment is always the best solution and if it might, at times, impede natural processes of growth and coping.

In this context, the study on universal DBT-based group skills training for teenagers challenged our assumptions. The unexpected outcomes suggest that societal and educational systems may naturally foster many of the skills that formalized therapy seeks to provide, and may do so with greater efficacy than that which prescriptive psychiatric treatments have to offer. Moreover, the universal discussion of psychiatric symptoms may not only destigmatize mental illness but also normalize it, potentially leading to unnecessary pathology.

Finally, the study prompted us to consider the fine balance that people find themselves in, questioning whether we should be so certain that our interventions can always provide a better outcome than an individual’s current coping mechanisms. These findings serve as a valuable reminder that our enthusiasm for widespread psychiatric interventions should be tempered by rigorous research and a nuanced understanding of human psychology and development.

This study could be an example of the grandiose stance psychiatry has at times taken of late, suggesting the field has an intervention for all that ails you and can serve as a corrective to society’s maladaptive deviations. Rising rates of mental illness in the community are not interpreted as a failing of the field of psychiatry, but as evidence that we need more psychiatrists. Acts of gun violence, ever increasing rates suicides, and even political disagreements are met with the idea that if only we had more mental health capacity, this could be avoided.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. ZoBell is a fourth-year senior resident at UCSD Psychiatry Residency Program. She is currently serving as the program’s Chief Resident at the VA San Diego on the inpatient psychiatric unit. Dr. ZoBell is interested in outpatient and emergency psychiatry as well as psychotherapy. Dr. Lehman is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is codirector of all acute and intensive psychiatric treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, where he practices clinical psychiatry. He has no conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Harvey, LJ, et al. Investigating the efficacy of a Dialectical behaviour therapy-based universal intervention on adolescent social and emotional well-being outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2023 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2023.104408.

We love psychiatry. We love the idea that someone can come to receive care from a physician to alleviate psychological suffering.

Some people experience such severe anguish that they are unable to relate to others. Some are so despondent that they are unable to make decisions. Some are so distressed that their thoughts become inconsistent with reality. We want all those people, and many more, to have access to effective psychiatric care. However, there are reasonable expectations that one should be able to have that a treatment will help, and that appropriate informed consent is given.

One recent article reminded us of this in a particularly poignant way.

The study in question is a recent publication looking at the universal use of psychotherapy for teenagers.1 At face value, we would have certainly considered this to be a benevolent and well-meaning intervention. Anyone who has been a teenager or has talked to one, is aware of the emotional instability punctuated by episodes of intense anxiety or irritability. It is age appropriate for a teenager to question and explore their identity. Teenagers are notoriously impulsive with a deep desire for validating interpersonal relationships. One could continue to list the symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and find a lot of similarity with the condition of transitioning from a child to an adult.

It is thus common sense to consider applying the most established therapy for BPD, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), to teenagers. The basics of DBT would seem to be helpful to anyone but appear particularly appropriate to this population. Mindfulness, the practice of paying attention to your present experience, allows one to realize that they are trapped in past or hypothetical future moments. Emotional regulation provides the tools that offer a frame for our feelings and involves recognizing feelings and understanding what they mean. Interpersonal work allows one to recognize and adapt to the feelings of others, while learning how to have a healthy voice with others. Distress tolerance is the exercise of learning to experience and contain our feelings.

The study looked at about 1,000 young adolescents, around 13 years old across high schools in Sydney, Australia: 598 adolescents were allocated to the intervention, and 566 to the control. The intervention consisted of eight weekly sessions of DBT lasting about 50 minutes. The results were “contrary to predictions.” Participants who received DBT “reported significantly increased total difficulties,” and “significant increases in depression and anxiety.” The effects were worse in males yet significant in both genders. The study concludes with “a reminder that present enthusiasm for universal dissemination of short-term DBT-based group skills training within schools, specifically in early adolescence, is ahead of the research evidence.”

We can’t help but wonder why the outcomes of the study were this way; here are some ideas:

• Society has natural ways of developing interpersonal skills, emotional regulation, and the ability to appreciate the present. Interpersonal skills are consistently fostered and tested in schools. Navigating high school parties, the process of organizing them, and getting invited to them requires significant social dexterity. Rejection from romantic interest, alienation from peers, rewards for accomplishment, and acceptance by other peers are some of the daily emotional obstacles that teenagers face. Being constantly taught by older individuals and scolded by parents is its own course in mindfulness. Those are few of the many natural processes of interpersonal growth that formalized therapy may impede.

• The universal discussion of psychological terms and psychiatric symptoms may not only destigmatize mental illness, but also normalize and possibly even promote it. While punishing or stigmatizing a child for having mental illness is obviously unacceptable and cruel, we do wonder if the compulsory psychotherapy may provide negative effects. Psychotherapies, especially manualized ones, were developed to alleviate mental suffering. It seems possible that this format normalizes pathology.

In 1961, Erving Goffman described the concept of sane people appearing insane in an asylum as “mortification.” In 2023, we have much improved, but have we done something to internalize patterns of suffering and alienation rather than dispel them? They are given forms that explain what the feeling of depression is when they may have never considered it. They are given tools to handle distress, when distress may not be present.

• Many human beings live on a fairly tight rope of suppression and the less adaptive repression. Suppression is the defense mechanism by which individuals make an effort to put distressing thoughts out of conscious awareness. After a difficult breakup a teenager may ask some friends to go out and watch a movie, making efforts to put negative feelings out of conscious awareness until there is an opportunity to cope adaptively with those stressors.

Repression is the defense mechanism by which individuals make an effort to prevent distressing thoughts from entering conscious awareness in the first place. After a difficult breakup a teenager acts like nothing happened. While not particularly adaptive, many people live with significant repression and without particular anguish. It is possible that uncovering all of those repressed and suppressed feelings through the exploratory work of therapy may destabilize individuals from their tight rope.

• A less problematic explanation could also be what was previously referred to as therapeutic regression. In psychoanalytic theory, patients are generally thought to have a compromise formation, a psychological strategy used to reconcile conflicting drives. The compromise formation is the way a patient balances their desires against moral expectations and the realities of the external world. In therapy, that compromise formation can be challenged, leading to therapeutic regression.

By uncovering and confronting deeply rooted feelings, a patient may find that their symptoms temporarily intensify. This may not be a problem, but a necessary step to growth in some patients. It is possible that a program longer than 8 weeks would have overcome a temporary worsening in outcome measures.

While it’s easy to highlight the darker moments in psychiatric history, psychiatry has grown into a field which offers well-accepted and uncontroversially promoted forms of treatment. This is evolution, exemplified by the mere consideration of the universal use of psychotherapy for teenagers. But this raises important questions about the potential unintended consequences of normalizing and formalizing therapy. It prompted us to reflect on whether psychiatric treatment is always the best solution and if it might, at times, impede natural processes of growth and coping.

In this context, the study on universal DBT-based group skills training for teenagers challenged our assumptions. The unexpected outcomes suggest that societal and educational systems may naturally foster many of the skills that formalized therapy seeks to provide, and may do so with greater efficacy than that which prescriptive psychiatric treatments have to offer. Moreover, the universal discussion of psychiatric symptoms may not only destigmatize mental illness but also normalize it, potentially leading to unnecessary pathology.

Finally, the study prompted us to consider the fine balance that people find themselves in, questioning whether we should be so certain that our interventions can always provide a better outcome than an individual’s current coping mechanisms. These findings serve as a valuable reminder that our enthusiasm for widespread psychiatric interventions should be tempered by rigorous research and a nuanced understanding of human psychology and development.

This study could be an example of the grandiose stance psychiatry has at times taken of late, suggesting the field has an intervention for all that ails you and can serve as a corrective to society’s maladaptive deviations. Rising rates of mental illness in the community are not interpreted as a failing of the field of psychiatry, but as evidence that we need more psychiatrists. Acts of gun violence, ever increasing rates suicides, and even political disagreements are met with the idea that if only we had more mental health capacity, this could be avoided.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. ZoBell is a fourth-year senior resident at UCSD Psychiatry Residency Program. She is currently serving as the program’s Chief Resident at the VA San Diego on the inpatient psychiatric unit. Dr. ZoBell is interested in outpatient and emergency psychiatry as well as psychotherapy. Dr. Lehman is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is codirector of all acute and intensive psychiatric treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, where he practices clinical psychiatry. He has no conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Harvey, LJ, et al. Investigating the efficacy of a Dialectical behaviour therapy-based universal intervention on adolescent social and emotional well-being outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2023 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2023.104408.

We love psychiatry. We love the idea that someone can come to receive care from a physician to alleviate psychological suffering.

Some people experience such severe anguish that they are unable to relate to others. Some are so despondent that they are unable to make decisions. Some are so distressed that their thoughts become inconsistent with reality. We want all those people, and many more, to have access to effective psychiatric care. However, there are reasonable expectations that one should be able to have that a treatment will help, and that appropriate informed consent is given.

One recent article reminded us of this in a particularly poignant way.

The study in question is a recent publication looking at the universal use of psychotherapy for teenagers.1 At face value, we would have certainly considered this to be a benevolent and well-meaning intervention. Anyone who has been a teenager or has talked to one, is aware of the emotional instability punctuated by episodes of intense anxiety or irritability. It is age appropriate for a teenager to question and explore their identity. Teenagers are notoriously impulsive with a deep desire for validating interpersonal relationships. One could continue to list the symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and find a lot of similarity with the condition of transitioning from a child to an adult.

It is thus common sense to consider applying the most established therapy for BPD, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), to teenagers. The basics of DBT would seem to be helpful to anyone but appear particularly appropriate to this population. Mindfulness, the practice of paying attention to your present experience, allows one to realize that they are trapped in past or hypothetical future moments. Emotional regulation provides the tools that offer a frame for our feelings and involves recognizing feelings and understanding what they mean. Interpersonal work allows one to recognize and adapt to the feelings of others, while learning how to have a healthy voice with others. Distress tolerance is the exercise of learning to experience and contain our feelings.

The study looked at about 1,000 young adolescents, around 13 years old across high schools in Sydney, Australia: 598 adolescents were allocated to the intervention, and 566 to the control. The intervention consisted of eight weekly sessions of DBT lasting about 50 minutes. The results were “contrary to predictions.” Participants who received DBT “reported significantly increased total difficulties,” and “significant increases in depression and anxiety.” The effects were worse in males yet significant in both genders. The study concludes with “a reminder that present enthusiasm for universal dissemination of short-term DBT-based group skills training within schools, specifically in early adolescence, is ahead of the research evidence.”

We can’t help but wonder why the outcomes of the study were this way; here are some ideas:

• Society has natural ways of developing interpersonal skills, emotional regulation, and the ability to appreciate the present. Interpersonal skills are consistently fostered and tested in schools. Navigating high school parties, the process of organizing them, and getting invited to them requires significant social dexterity. Rejection from romantic interest, alienation from peers, rewards for accomplishment, and acceptance by other peers are some of the daily emotional obstacles that teenagers face. Being constantly taught by older individuals and scolded by parents is its own course in mindfulness. Those are few of the many natural processes of interpersonal growth that formalized therapy may impede.

• The universal discussion of psychological terms and psychiatric symptoms may not only destigmatize mental illness, but also normalize and possibly even promote it. While punishing or stigmatizing a child for having mental illness is obviously unacceptable and cruel, we do wonder if the compulsory psychotherapy may provide negative effects. Psychotherapies, especially manualized ones, were developed to alleviate mental suffering. It seems possible that this format normalizes pathology.

In 1961, Erving Goffman described the concept of sane people appearing insane in an asylum as “mortification.” In 2023, we have much improved, but have we done something to internalize patterns of suffering and alienation rather than dispel them? They are given forms that explain what the feeling of depression is when they may have never considered it. They are given tools to handle distress, when distress may not be present.

• Many human beings live on a fairly tight rope of suppression and the less adaptive repression. Suppression is the defense mechanism by which individuals make an effort to put distressing thoughts out of conscious awareness. After a difficult breakup a teenager may ask some friends to go out and watch a movie, making efforts to put negative feelings out of conscious awareness until there is an opportunity to cope adaptively with those stressors.

Repression is the defense mechanism by which individuals make an effort to prevent distressing thoughts from entering conscious awareness in the first place. After a difficult breakup a teenager acts like nothing happened. While not particularly adaptive, many people live with significant repression and without particular anguish. It is possible that uncovering all of those repressed and suppressed feelings through the exploratory work of therapy may destabilize individuals from their tight rope.

• A less problematic explanation could also be what was previously referred to as therapeutic regression. In psychoanalytic theory, patients are generally thought to have a compromise formation, a psychological strategy used to reconcile conflicting drives. The compromise formation is the way a patient balances their desires against moral expectations and the realities of the external world. In therapy, that compromise formation can be challenged, leading to therapeutic regression.

By uncovering and confronting deeply rooted feelings, a patient may find that their symptoms temporarily intensify. This may not be a problem, but a necessary step to growth in some patients. It is possible that a program longer than 8 weeks would have overcome a temporary worsening in outcome measures.

While it’s easy to highlight the darker moments in psychiatric history, psychiatry has grown into a field which offers well-accepted and uncontroversially promoted forms of treatment. This is evolution, exemplified by the mere consideration of the universal use of psychotherapy for teenagers. But this raises important questions about the potential unintended consequences of normalizing and formalizing therapy. It prompted us to reflect on whether psychiatric treatment is always the best solution and if it might, at times, impede natural processes of growth and coping.

In this context, the study on universal DBT-based group skills training for teenagers challenged our assumptions. The unexpected outcomes suggest that societal and educational systems may naturally foster many of the skills that formalized therapy seeks to provide, and may do so with greater efficacy than that which prescriptive psychiatric treatments have to offer. Moreover, the universal discussion of psychiatric symptoms may not only destigmatize mental illness but also normalize it, potentially leading to unnecessary pathology.

Finally, the study prompted us to consider the fine balance that people find themselves in, questioning whether we should be so certain that our interventions can always provide a better outcome than an individual’s current coping mechanisms. These findings serve as a valuable reminder that our enthusiasm for widespread psychiatric interventions should be tempered by rigorous research and a nuanced understanding of human psychology and development.

This study could be an example of the grandiose stance psychiatry has at times taken of late, suggesting the field has an intervention for all that ails you and can serve as a corrective to society’s maladaptive deviations. Rising rates of mental illness in the community are not interpreted as a failing of the field of psychiatry, but as evidence that we need more psychiatrists. Acts of gun violence, ever increasing rates suicides, and even political disagreements are met with the idea that if only we had more mental health capacity, this could be avoided.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. ZoBell is a fourth-year senior resident at UCSD Psychiatry Residency Program. She is currently serving as the program’s Chief Resident at the VA San Diego on the inpatient psychiatric unit. Dr. ZoBell is interested in outpatient and emergency psychiatry as well as psychotherapy. Dr. Lehman is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is codirector of all acute and intensive psychiatric treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, where he practices clinical psychiatry. He has no conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Harvey, LJ, et al. Investigating the efficacy of a Dialectical behaviour therapy-based universal intervention on adolescent social and emotional well-being outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2023 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2023.104408.

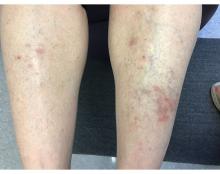

A 55-year-old female presented a with few years' history of pruritic plaques on her shins and wrists

. Lesions may have a covering of scale. HLP commonly affects middle aged men and women. Lesions are most commonly located bilaterally on the shins and ankles and can be painful or pruritic. The differential diagnosis for the condition includes lichen simplex chronicus, connective tissue disease, and other skin disorders that cause hyperkeratosis. This wide differential makes histopathological analysis a useful tool in confirming the diagnosis of HLP.

A definitive diagnosis can be made via skin biopsy. Histopathology reveals hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. An eosinophilic infiltrate may be present. Other common features include saw tooth rete ridges and Civatte bodies, which are apoptotic keratinocytes. The lymphocytic infiltrate may indicate an autoimmune etiology in which the body’s immune system erroneously attacks itself. However, the exact cause is not known and genetic and environmental factors may play a role.

The treatment of HLP includes symptomatic management and control of inflammation. Topical steroids can be prescribed to manage the inflammation and associated pruritus, and emollient creams and moisturizers are helpful in controlling the dryness. Oral steroids, immunosuppressant medications, or retinoids may be necessary in more severe cases. In addition, psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) light therapy has been found to be beneficial in some cases. Squamous cell carcinoma may arise in lesions.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD, Aventura, Florida. The column was edited by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen Planus. [Updated 2023 Jun 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

Jaime TJ et al. An Bras Dermatol. 2011 Jul-Aug;86(4 Suppl 1):S96-9.

Mirchandani S et al. Med Pharm Rep. 2020 Apr;93(2):210-2. .

Whittington CP et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2023 Jun 19. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2022-0515-RA.

. Lesions may have a covering of scale. HLP commonly affects middle aged men and women. Lesions are most commonly located bilaterally on the shins and ankles and can be painful or pruritic. The differential diagnosis for the condition includes lichen simplex chronicus, connective tissue disease, and other skin disorders that cause hyperkeratosis. This wide differential makes histopathological analysis a useful tool in confirming the diagnosis of HLP.

A definitive diagnosis can be made via skin biopsy. Histopathology reveals hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. An eosinophilic infiltrate may be present. Other common features include saw tooth rete ridges and Civatte bodies, which are apoptotic keratinocytes. The lymphocytic infiltrate may indicate an autoimmune etiology in which the body’s immune system erroneously attacks itself. However, the exact cause is not known and genetic and environmental factors may play a role.

The treatment of HLP includes symptomatic management and control of inflammation. Topical steroids can be prescribed to manage the inflammation and associated pruritus, and emollient creams and moisturizers are helpful in controlling the dryness. Oral steroids, immunosuppressant medications, or retinoids may be necessary in more severe cases. In addition, psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) light therapy has been found to be beneficial in some cases. Squamous cell carcinoma may arise in lesions.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD, Aventura, Florida. The column was edited by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen Planus. [Updated 2023 Jun 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

Jaime TJ et al. An Bras Dermatol. 2011 Jul-Aug;86(4 Suppl 1):S96-9.

Mirchandani S et al. Med Pharm Rep. 2020 Apr;93(2):210-2. .

Whittington CP et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2023 Jun 19. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2022-0515-RA.

. Lesions may have a covering of scale. HLP commonly affects middle aged men and women. Lesions are most commonly located bilaterally on the shins and ankles and can be painful or pruritic. The differential diagnosis for the condition includes lichen simplex chronicus, connective tissue disease, and other skin disorders that cause hyperkeratosis. This wide differential makes histopathological analysis a useful tool in confirming the diagnosis of HLP.

A definitive diagnosis can be made via skin biopsy. Histopathology reveals hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. An eosinophilic infiltrate may be present. Other common features include saw tooth rete ridges and Civatte bodies, which are apoptotic keratinocytes. The lymphocytic infiltrate may indicate an autoimmune etiology in which the body’s immune system erroneously attacks itself. However, the exact cause is not known and genetic and environmental factors may play a role.

The treatment of HLP includes symptomatic management and control of inflammation. Topical steroids can be prescribed to manage the inflammation and associated pruritus, and emollient creams and moisturizers are helpful in controlling the dryness. Oral steroids, immunosuppressant medications, or retinoids may be necessary in more severe cases. In addition, psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) light therapy has been found to be beneficial in some cases. Squamous cell carcinoma may arise in lesions.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD, Aventura, Florida. The column was edited by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen Planus. [Updated 2023 Jun 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

Jaime TJ et al. An Bras Dermatol. 2011 Jul-Aug;86(4 Suppl 1):S96-9.

Mirchandani S et al. Med Pharm Rep. 2020 Apr;93(2):210-2. .

Whittington CP et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2023 Jun 19. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2022-0515-RA.

Erectile Dysfunction Rx: Give It a Shot

This transcript has been edited for clarity.