User login

The Right Choice? The importance of sometimes saying “no”

When I was a resident, one of the surgery faculty who often performed big, high-risk operations liked to say, “If the patient can tolerate a haircut, he can tolerate an operation.” By this, he meant that there were not patients who were too sick for surgery if the operation was indicated. However, over the last 2 decades, I have seen a handful of patients for whom the risks of the operation far outweigh the potential benefits and for whom I have said I am not offering surgery as an option.

Recently, I had a chance to discuss troubling ethics cases with group of thoughtful surgical residents. They raised concerns over the common scenario of being consulted in the middle of the night on the critically ill patient in the intensive care unit for whom the risks of surgery are extremely high. These residents asked the question of whether it is ever acceptable for surgeons to simply refuse to take such patients to the operating room if the alternative to surgery is virtually certain death. The overriding concern among the residents was whether saying “no” to a request for operative intervention in a critically ill patient can ever be justified since the surgeon is essentially “playing God” by not offering the possibility of intervention.

There is no question that there can be very sick patients who have a poor prognosis and the decision is appropriately made to recommend surgery even though the risks are very high. I also believe that there are patients for whom the risks of surgery are so high, and the prospects for a good outcome are so low, that surgery should not be recommended. However, it is important to distinguish two different scenarios. In one scenario, the surgical consultant decides that surgery is an option, but then tries to convince the surrogate decision makers (usually the patient’s family) to decline surgery because of the very high risks. In the second scenario, the surgeon decides that the risks to the patient are so high that it would be wrong to even take the patient to the operating room.

In both scenarios, the patient does not get an operation and in the vast majority of such cases, the patient will die in a short period of time. The question remains whether it is better to give families a choice or not. I believe that posing the question in this manner is misleading and presents a false dichotomy.

Although the distinctions can be subtle, it is critical for the surgeon to decide whether each patient has a high enough chance for survival that the operation is medically justifiable. If the answer is “yes,” then the next question will be one for the surrogate decision makers to decide whether to consent to the surgery or not. Based on the importance of respecting the autonomous choices of patients or their surrogates, it is important that surgeons respect the choice not to have an operation even if one is being recommended. If the answer to the question of whether the operation is medically justifiable is “no,” to offer surgery to family and then try to convince them to decline it by overstating the risks is misleading. Although such a strategy would give the family a sense of control over the situation, it would also give the false impression that surgery is truly an option. To act this way would allow the surgeon the ability to avoid “playing God” since the family is “making the decision”. However, I believe that taking that decision away from families when there is not really a reasonable choice for surgery is a better way to eliminate their potential guilt. Not only is it ethically acceptable to decline to offer an operation to an extremely high-risk patient, I would argue that such behavior is actually the ethical responsibility of the surgeon. We should take on the burden of saying “no” when surgery should NOT be performed. Forcing such a decision on families in the name of respecting autonomy is to shirk our responsibility and something that we must avoid doing whenever possible.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

When I was a resident, one of the surgery faculty who often performed big, high-risk operations liked to say, “If the patient can tolerate a haircut, he can tolerate an operation.” By this, he meant that there were not patients who were too sick for surgery if the operation was indicated. However, over the last 2 decades, I have seen a handful of patients for whom the risks of the operation far outweigh the potential benefits and for whom I have said I am not offering surgery as an option.

Recently, I had a chance to discuss troubling ethics cases with group of thoughtful surgical residents. They raised concerns over the common scenario of being consulted in the middle of the night on the critically ill patient in the intensive care unit for whom the risks of surgery are extremely high. These residents asked the question of whether it is ever acceptable for surgeons to simply refuse to take such patients to the operating room if the alternative to surgery is virtually certain death. The overriding concern among the residents was whether saying “no” to a request for operative intervention in a critically ill patient can ever be justified since the surgeon is essentially “playing God” by not offering the possibility of intervention.

There is no question that there can be very sick patients who have a poor prognosis and the decision is appropriately made to recommend surgery even though the risks are very high. I also believe that there are patients for whom the risks of surgery are so high, and the prospects for a good outcome are so low, that surgery should not be recommended. However, it is important to distinguish two different scenarios. In one scenario, the surgical consultant decides that surgery is an option, but then tries to convince the surrogate decision makers (usually the patient’s family) to decline surgery because of the very high risks. In the second scenario, the surgeon decides that the risks to the patient are so high that it would be wrong to even take the patient to the operating room.

In both scenarios, the patient does not get an operation and in the vast majority of such cases, the patient will die in a short period of time. The question remains whether it is better to give families a choice or not. I believe that posing the question in this manner is misleading and presents a false dichotomy.

Although the distinctions can be subtle, it is critical for the surgeon to decide whether each patient has a high enough chance for survival that the operation is medically justifiable. If the answer is “yes,” then the next question will be one for the surrogate decision makers to decide whether to consent to the surgery or not. Based on the importance of respecting the autonomous choices of patients or their surrogates, it is important that surgeons respect the choice not to have an operation even if one is being recommended. If the answer to the question of whether the operation is medically justifiable is “no,” to offer surgery to family and then try to convince them to decline it by overstating the risks is misleading. Although such a strategy would give the family a sense of control over the situation, it would also give the false impression that surgery is truly an option. To act this way would allow the surgeon the ability to avoid “playing God” since the family is “making the decision”. However, I believe that taking that decision away from families when there is not really a reasonable choice for surgery is a better way to eliminate their potential guilt. Not only is it ethically acceptable to decline to offer an operation to an extremely high-risk patient, I would argue that such behavior is actually the ethical responsibility of the surgeon. We should take on the burden of saying “no” when surgery should NOT be performed. Forcing such a decision on families in the name of respecting autonomy is to shirk our responsibility and something that we must avoid doing whenever possible.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

When I was a resident, one of the surgery faculty who often performed big, high-risk operations liked to say, “If the patient can tolerate a haircut, he can tolerate an operation.” By this, he meant that there were not patients who were too sick for surgery if the operation was indicated. However, over the last 2 decades, I have seen a handful of patients for whom the risks of the operation far outweigh the potential benefits and for whom I have said I am not offering surgery as an option.

Recently, I had a chance to discuss troubling ethics cases with group of thoughtful surgical residents. They raised concerns over the common scenario of being consulted in the middle of the night on the critically ill patient in the intensive care unit for whom the risks of surgery are extremely high. These residents asked the question of whether it is ever acceptable for surgeons to simply refuse to take such patients to the operating room if the alternative to surgery is virtually certain death. The overriding concern among the residents was whether saying “no” to a request for operative intervention in a critically ill patient can ever be justified since the surgeon is essentially “playing God” by not offering the possibility of intervention.

There is no question that there can be very sick patients who have a poor prognosis and the decision is appropriately made to recommend surgery even though the risks are very high. I also believe that there are patients for whom the risks of surgery are so high, and the prospects for a good outcome are so low, that surgery should not be recommended. However, it is important to distinguish two different scenarios. In one scenario, the surgical consultant decides that surgery is an option, but then tries to convince the surrogate decision makers (usually the patient’s family) to decline surgery because of the very high risks. In the second scenario, the surgeon decides that the risks to the patient are so high that it would be wrong to even take the patient to the operating room.

In both scenarios, the patient does not get an operation and in the vast majority of such cases, the patient will die in a short period of time. The question remains whether it is better to give families a choice or not. I believe that posing the question in this manner is misleading and presents a false dichotomy.

Although the distinctions can be subtle, it is critical for the surgeon to decide whether each patient has a high enough chance for survival that the operation is medically justifiable. If the answer is “yes,” then the next question will be one for the surrogate decision makers to decide whether to consent to the surgery or not. Based on the importance of respecting the autonomous choices of patients or their surrogates, it is important that surgeons respect the choice not to have an operation even if one is being recommended. If the answer to the question of whether the operation is medically justifiable is “no,” to offer surgery to family and then try to convince them to decline it by overstating the risks is misleading. Although such a strategy would give the family a sense of control over the situation, it would also give the false impression that surgery is truly an option. To act this way would allow the surgeon the ability to avoid “playing God” since the family is “making the decision”. However, I believe that taking that decision away from families when there is not really a reasonable choice for surgery is a better way to eliminate their potential guilt. Not only is it ethically acceptable to decline to offer an operation to an extremely high-risk patient, I would argue that such behavior is actually the ethical responsibility of the surgeon. We should take on the burden of saying “no” when surgery should NOT be performed. Forcing such a decision on families in the name of respecting autonomy is to shirk our responsibility and something that we must avoid doing whenever possible.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Has your bread become stale?

Diagnosing and treating illnesses are the bread and butter of hospitalist medicine. Has your bread become stale?

I used to be envious of older physicians who ‘grandfathered in’ and became exempt from the requirement to recertify every 10 years for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Preparing for the boards is extremely time consuming and, at times, incredibly stressful, but it’s what we have to do to prove that our medical knowledge is up to date, right?

Who hasn’t heard of at least one nightmare outcome after a physician treated a patient with out-of-date standards, probably the same ones he learned in medical school a long, long time ago? We may snicker at this scenario, but could we be guilty too? Could we be so set in our ways, so self-confident that we refuse to grow?

I was watching a hospital medicine CME DVD a few months ago and was shocked, as well as embarrassed, to learn that the way I was performing part of my neurological exam was antiquated. There was a new “gold standard” that I had never learned before. After all, I had been doing the exact same thing for years; too many years, it seems. I mistakenly assumed that all the physical examination skills I had learned in medical school were set in stone. But as in all aspects of medicine, even best practices for performing a basic examination have evolved over the years.

Then there is the old habit of ordering multiple blood tests on hospitalized patients every day. That’s just how many of us were trained during residency, but in real life it’s not always necessary. Sure, if there’s a reason to be concerned about specific parameters they should be followed closely, but most inpatients don’t really need chemistries and a CBC each and every day; if they weren’t already anemic, we could make them anemic with excessive blood draws. And how much of that knee-jerk reflex to order daily “routine labs” is really just defensive medicine anyway?

I recently started teaching residents and was a little apprehensive in the very beginning. After all, 2 decades later, I still remember the good (and bad) attendings, and to this very day I incorporate parts of what the good ones taught me into patient encounters. Now I would be the one who could leave a lasting, hopefully positive impression in brilliant young minds. I have found teaching residents to be motivating and eye-opening. I get to see what’s new on their burgeoning, technologically advanced horizons; and I am learning from them, too. It’s invigorating to grow in the field I love so much, to expand my mind and, sometimes, humbly acknowledge I need to switch gears and proceed in a different direction; I suspect many others would benefit from this revelation as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

Diagnosing and treating illnesses are the bread and butter of hospitalist medicine. Has your bread become stale?

I used to be envious of older physicians who ‘grandfathered in’ and became exempt from the requirement to recertify every 10 years for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Preparing for the boards is extremely time consuming and, at times, incredibly stressful, but it’s what we have to do to prove that our medical knowledge is up to date, right?

Who hasn’t heard of at least one nightmare outcome after a physician treated a patient with out-of-date standards, probably the same ones he learned in medical school a long, long time ago? We may snicker at this scenario, but could we be guilty too? Could we be so set in our ways, so self-confident that we refuse to grow?

I was watching a hospital medicine CME DVD a few months ago and was shocked, as well as embarrassed, to learn that the way I was performing part of my neurological exam was antiquated. There was a new “gold standard” that I had never learned before. After all, I had been doing the exact same thing for years; too many years, it seems. I mistakenly assumed that all the physical examination skills I had learned in medical school were set in stone. But as in all aspects of medicine, even best practices for performing a basic examination have evolved over the years.

Then there is the old habit of ordering multiple blood tests on hospitalized patients every day. That’s just how many of us were trained during residency, but in real life it’s not always necessary. Sure, if there’s a reason to be concerned about specific parameters they should be followed closely, but most inpatients don’t really need chemistries and a CBC each and every day; if they weren’t already anemic, we could make them anemic with excessive blood draws. And how much of that knee-jerk reflex to order daily “routine labs” is really just defensive medicine anyway?

I recently started teaching residents and was a little apprehensive in the very beginning. After all, 2 decades later, I still remember the good (and bad) attendings, and to this very day I incorporate parts of what the good ones taught me into patient encounters. Now I would be the one who could leave a lasting, hopefully positive impression in brilliant young minds. I have found teaching residents to be motivating and eye-opening. I get to see what’s new on their burgeoning, technologically advanced horizons; and I am learning from them, too. It’s invigorating to grow in the field I love so much, to expand my mind and, sometimes, humbly acknowledge I need to switch gears and proceed in a different direction; I suspect many others would benefit from this revelation as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

Diagnosing and treating illnesses are the bread and butter of hospitalist medicine. Has your bread become stale?

I used to be envious of older physicians who ‘grandfathered in’ and became exempt from the requirement to recertify every 10 years for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Preparing for the boards is extremely time consuming and, at times, incredibly stressful, but it’s what we have to do to prove that our medical knowledge is up to date, right?

Who hasn’t heard of at least one nightmare outcome after a physician treated a patient with out-of-date standards, probably the same ones he learned in medical school a long, long time ago? We may snicker at this scenario, but could we be guilty too? Could we be so set in our ways, so self-confident that we refuse to grow?

I was watching a hospital medicine CME DVD a few months ago and was shocked, as well as embarrassed, to learn that the way I was performing part of my neurological exam was antiquated. There was a new “gold standard” that I had never learned before. After all, I had been doing the exact same thing for years; too many years, it seems. I mistakenly assumed that all the physical examination skills I had learned in medical school were set in stone. But as in all aspects of medicine, even best practices for performing a basic examination have evolved over the years.

Then there is the old habit of ordering multiple blood tests on hospitalized patients every day. That’s just how many of us were trained during residency, but in real life it’s not always necessary. Sure, if there’s a reason to be concerned about specific parameters they should be followed closely, but most inpatients don’t really need chemistries and a CBC each and every day; if they weren’t already anemic, we could make them anemic with excessive blood draws. And how much of that knee-jerk reflex to order daily “routine labs” is really just defensive medicine anyway?

I recently started teaching residents and was a little apprehensive in the very beginning. After all, 2 decades later, I still remember the good (and bad) attendings, and to this very day I incorporate parts of what the good ones taught me into patient encounters. Now I would be the one who could leave a lasting, hopefully positive impression in brilliant young minds. I have found teaching residents to be motivating and eye-opening. I get to see what’s new on their burgeoning, technologically advanced horizons; and I am learning from them, too. It’s invigorating to grow in the field I love so much, to expand my mind and, sometimes, humbly acknowledge I need to switch gears and proceed in a different direction; I suspect many others would benefit from this revelation as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

“If I had a hammer ... ”

Okay, it’s 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Do you know where your reflex hammer is? Do you even own one, or are reflex hammers just one of those things that should be part of the standard doctoring junk in the drawers of some (but, frustratingly not all) of the exam rooms in the clinic where you work? If you do own one, where did you get it? The last time you handled your reflex hammer, had the once-soft head ossified? And, now for the big question: Do you even care where your reflex hammer is hiding?

Several years ago, I wrote you about my long and deeply emotional relationship with tongue depressors. For 40 years, there was scarcely a waking hour that I wasn’t carrying at least one of these indispensable birch beauties over my heart in my shirt pocket. Throat sticks were a badge of my professional status, and I used them as much as a one-piece Leatherman (could be Swiss Army or multitool if you are uncomfortable with brand names) as I did for depressing tongues. Now that I no longer see patients, I always have a throat stick within reach to stir paint or shim the many poorly crafted D.I.Y. projects I have foolishly tackled.

On the other hand, I never grew very fond of my reflex hammer. In fact, I have never had much use for it. When I was a first-year medical student, most of us were short of money and even shorter on concerns about conflict of interest. Drug companies were eager to imprint their names on our pliable minds. We were offered nice black leather bags and stethoscopes. I still have and regularly used my Littman stethoscope. After many tubing replacements, the head no longer swivels to the bell position, which I never found very helpful anyway. In the bag was a reflex hammer with “Lilly” stamped on the silver-colored handle.

I’m not sure how many years of unsuccessfully trying to consistently elicit deep tendon reflexes passed before I finally gave up. But it wasn’t many. In a general outpatient pediatric practice, there are very few situations that I felt I needed to know about the patient’s reflexes. Certainly, I didn’t see that they needed to be included as part of a health maintenance exam of a child with no complaints.

But every now and then a patient would complain, “Hey, you didn’t hit my knee with that hammer thing.” If they pleaded long enough, I would go hunting for one in a drawer. I didn’t want my patients to leave the office feeling that they had been cheated out of a full exam. If I couldn’t find a hammer, which happened more often than not, I would use the edge of my stethoscope as my tendon whacker. Maybe that’s why the old friend stopped rotating. If I had time, I would use the hammer or stethoscope edge to tap on the tendon of the forearm muscle that extends the middle finger. The result was particularly amusing to the preteen boys.

Of course, once every month or 3, I would encounter a clinical situation where knowing the status of the patient’s deep tendon reflexes might, just might, help me make a diagnosis. Obviously, if I had been a hospitalist, neurologist, or emergency department physician, I would have used a reflex hammer often enough to keep one handy. But, for me, the reflex hammer has been relegated to the drawer of miscellaneous stuff that is useful in eliciting memories, but that’s about it. Oh, by the way have you seen your head mirror lately?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping With a Picky Eater.”

Okay, it’s 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Do you know where your reflex hammer is? Do you even own one, or are reflex hammers just one of those things that should be part of the standard doctoring junk in the drawers of some (but, frustratingly not all) of the exam rooms in the clinic where you work? If you do own one, where did you get it? The last time you handled your reflex hammer, had the once-soft head ossified? And, now for the big question: Do you even care where your reflex hammer is hiding?

Several years ago, I wrote you about my long and deeply emotional relationship with tongue depressors. For 40 years, there was scarcely a waking hour that I wasn’t carrying at least one of these indispensable birch beauties over my heart in my shirt pocket. Throat sticks were a badge of my professional status, and I used them as much as a one-piece Leatherman (could be Swiss Army or multitool if you are uncomfortable with brand names) as I did for depressing tongues. Now that I no longer see patients, I always have a throat stick within reach to stir paint or shim the many poorly crafted D.I.Y. projects I have foolishly tackled.

On the other hand, I never grew very fond of my reflex hammer. In fact, I have never had much use for it. When I was a first-year medical student, most of us were short of money and even shorter on concerns about conflict of interest. Drug companies were eager to imprint their names on our pliable minds. We were offered nice black leather bags and stethoscopes. I still have and regularly used my Littman stethoscope. After many tubing replacements, the head no longer swivels to the bell position, which I never found very helpful anyway. In the bag was a reflex hammer with “Lilly” stamped on the silver-colored handle.

I’m not sure how many years of unsuccessfully trying to consistently elicit deep tendon reflexes passed before I finally gave up. But it wasn’t many. In a general outpatient pediatric practice, there are very few situations that I felt I needed to know about the patient’s reflexes. Certainly, I didn’t see that they needed to be included as part of a health maintenance exam of a child with no complaints.

But every now and then a patient would complain, “Hey, you didn’t hit my knee with that hammer thing.” If they pleaded long enough, I would go hunting for one in a drawer. I didn’t want my patients to leave the office feeling that they had been cheated out of a full exam. If I couldn’t find a hammer, which happened more often than not, I would use the edge of my stethoscope as my tendon whacker. Maybe that’s why the old friend stopped rotating. If I had time, I would use the hammer or stethoscope edge to tap on the tendon of the forearm muscle that extends the middle finger. The result was particularly amusing to the preteen boys.

Of course, once every month or 3, I would encounter a clinical situation where knowing the status of the patient’s deep tendon reflexes might, just might, help me make a diagnosis. Obviously, if I had been a hospitalist, neurologist, or emergency department physician, I would have used a reflex hammer often enough to keep one handy. But, for me, the reflex hammer has been relegated to the drawer of miscellaneous stuff that is useful in eliciting memories, but that’s about it. Oh, by the way have you seen your head mirror lately?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping With a Picky Eater.”

Okay, it’s 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Do you know where your reflex hammer is? Do you even own one, or are reflex hammers just one of those things that should be part of the standard doctoring junk in the drawers of some (but, frustratingly not all) of the exam rooms in the clinic where you work? If you do own one, where did you get it? The last time you handled your reflex hammer, had the once-soft head ossified? And, now for the big question: Do you even care where your reflex hammer is hiding?

Several years ago, I wrote you about my long and deeply emotional relationship with tongue depressors. For 40 years, there was scarcely a waking hour that I wasn’t carrying at least one of these indispensable birch beauties over my heart in my shirt pocket. Throat sticks were a badge of my professional status, and I used them as much as a one-piece Leatherman (could be Swiss Army or multitool if you are uncomfortable with brand names) as I did for depressing tongues. Now that I no longer see patients, I always have a throat stick within reach to stir paint or shim the many poorly crafted D.I.Y. projects I have foolishly tackled.

On the other hand, I never grew very fond of my reflex hammer. In fact, I have never had much use for it. When I was a first-year medical student, most of us were short of money and even shorter on concerns about conflict of interest. Drug companies were eager to imprint their names on our pliable minds. We were offered nice black leather bags and stethoscopes. I still have and regularly used my Littman stethoscope. After many tubing replacements, the head no longer swivels to the bell position, which I never found very helpful anyway. In the bag was a reflex hammer with “Lilly” stamped on the silver-colored handle.

I’m not sure how many years of unsuccessfully trying to consistently elicit deep tendon reflexes passed before I finally gave up. But it wasn’t many. In a general outpatient pediatric practice, there are very few situations that I felt I needed to know about the patient’s reflexes. Certainly, I didn’t see that they needed to be included as part of a health maintenance exam of a child with no complaints.

But every now and then a patient would complain, “Hey, you didn’t hit my knee with that hammer thing.” If they pleaded long enough, I would go hunting for one in a drawer. I didn’t want my patients to leave the office feeling that they had been cheated out of a full exam. If I couldn’t find a hammer, which happened more often than not, I would use the edge of my stethoscope as my tendon whacker. Maybe that’s why the old friend stopped rotating. If I had time, I would use the hammer or stethoscope edge to tap on the tendon of the forearm muscle that extends the middle finger. The result was particularly amusing to the preteen boys.

Of course, once every month or 3, I would encounter a clinical situation where knowing the status of the patient’s deep tendon reflexes might, just might, help me make a diagnosis. Obviously, if I had been a hospitalist, neurologist, or emergency department physician, I would have used a reflex hammer often enough to keep one handy. But, for me, the reflex hammer has been relegated to the drawer of miscellaneous stuff that is useful in eliciting memories, but that’s about it. Oh, by the way have you seen your head mirror lately?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping With a Picky Eater.”

Shyness vs. social anxiety

Many advocating for more attention to psychosocial issues by primary care pediatricians focus on serious conditions and the value of early recognition. For example, early recognition of autism spectrum disorder could lead to earlier intensive treatment that might impact the long-term course. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder very likely will lessen symptoms and also maintain self-esteem under the withering ordeal – often punctuated by teacher comments – of trying to pay attention hour after hour in school

Are there seemingly less serious conditions very likely worthy of early diagnosis, even those on the edge of normal developmental hurdles? One of the essential tasks of childhood is mastering the anxiety that emerges as children face the new challenges of each developmental stage, so parents, teachers, and clinicians are (or need to be) used to bearing anxiety in the children with whom they work. Intense shyness and anxiety around separation from parents are routine and healthy in infants and toddlers from 6-18 months. Anxiety in new social situations, such as the first day of preschool, is the rule, not the exception. School-age children commonly experience a surge of anxiety around performance and independence, as they are managing and mastering new skills in these domains every day. This anxiety can cause distress, but it should get better every time a child faces it, as they become better at managing the situation. When a child has an anxious temperament, poor coping skills, or parents who struggle to manage their own anxiety, children may have a harder time mastering new, anxiety-provoking challenges across settings. But, with time, and even just one adult who patiently models good coping, they will face and manage challenges. Social anxiety disorder is present when specific social or performance situations provoke the same intense anxiety and avoidance over and over, and for more than 6 months.

Most infants and young children who are more timid and fearful seem to grow into a normal range of social behavior, although few become extroverts. Some of these shy children are cautious in new situations for a period of time measured in minutes, but once the situations are familiar, these children are indistinguishable from their peers. However, some of these temperamentally timid children emerge consistently more anxious with greater likelihood to have phobias and to have social anxiety that can seriously impact long term happiness, achievement, and increase risk taking behaviors. A pediatrician should watch and note the emerging pattern of a timid toddler to see if the shyness eases or impacts social functioning; by bending the course of social interactions, social anxiety disorder critically affects developing social skills, self-regulation, affect tolerance, emerging identity, and confidence. Recognition and effective treatment of social anxiety will keep a child on the optimal developmental trajectory.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric illnesses in the United States, and social anxiety disorder (previously labeled as social phobia) is the third most common psychiatric disorder in U.S. adults (after depression and alcohol dependence). Most persistent anxiety disorders begin in childhood, and social anxiety is no exception. The mean age of onset for social anxiety is 13 years old, and it rarely begins after the age of 25, with an annual prevalence around 7% in childhood and adolescence (Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2009;32;483-524).The DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety disorder include, “a marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations in which the person is exposed to unfamiliar people or to possible scrutiny by others,” and exposure to those situations provokes intense anxiety, which in children can be marked by severe or prolonged crying, freezing, tantrums, shrinking from social situations, refusing to speak, or clinging to parents. In adolescents, it may trigger panic attacks. The avoidance and distress interfere with the child’s function in school, social activities, or relationships, and must have lasted for at least 6 months. To ensure that there is not another problem of social relatedness, the child should have shown some capacity to have normal peer relationships.

Will social anxiety disorder be vividly apparent to teachers, parents, and clinicians? No. The feeling of anxiety is an internal experience, not easily observed, and anxious children and teens are rarely eager or comfortable communicators about their own anxiety. Indeed, in a 2007 survey of patients in treatment for anxiety, 36% of people with social anxiety disorder reported experiencing symptoms for 10 or more years before seeking help. It’s true that the distress children experience when feeling intensely anxious will probably be observable, but all of those behaviors (clinging, crying, tantrums) are common and normal expressions of distress in childhood. Even in adolescence, while having a panic attack may prompt the teenager to seek care, she may not connect it with the anxiety she was feeling about being called on in class or talking to peers, especially if that is an anxiety she has experienced for a long time as a daily part of her lives and routines.

Social anxiety disorder is treatable. The first-line treatment in mild to moderate cases, particularly with younger children, is cognitive-behavioral therapy. This is a practical variant of psychotherapy in which children develop and practice skills at recognizing and labeling their own feelings of anxiety, identifying the situations that trigger them, and practicing relaxation strategies that help them to face and manage the anxiety-provoking situations rather than avoiding them.

When symptoms or the degree of impairment are more severe, medications can become an important part of treatment. SSRIs are the first-line medications used to treat social anxiety disorder, and the effective doses are often higher than effective antidepressant doses, although we often titrate toward those doses more slowly with anxious patients to avoid side effects that might increase or exacerbate their anxiety.

Even with effective medication treatment, though, psychotherapy will be an essential part of treatment. These young patients need to build the essential skills of anxiety management, although it is in the nature of anxiety that such patients often wish to dissolve their anxiety by simply using a pill.

Anxiety disorders are typically chronic and will persist without effective treatment. Failure to recognize and treat social anxiety disorder can distort or even derail healthy development and may result in major psychiatric complications. As a pediatrician, you are trying to stop or modify a chain of potential events. Imagine a socially anxious young woman who enters puberty in high school. Will she withdraw from social activities? Will she avoid new opportunities or interests? Will alcohol become a necessary social lubricant? Will she be at increased risk for sexual assault at a party or poor grades in school? Will social anxiety affect her choice of college, fearful of leaving home? The incidence of secondary depression and substance abuse disorders is substantially higher in adolescents with untreated anxiety disorders. Although a depressed, alcohol-dependent teenager is more likely to be recognized as needing treatment, once they have developed those complications, effective treatment of the underlying anxiety will be much more complicated and slow to treat. Prevention starting before puberty is a much more desirable approach.

Pediatricians truly do have the opportunity to improve outcomes for these patients, by learning to recognize this sometimes-invisible disorder. Children suffering from anxiety disorders are more likely to identify a physical concern than a psychological one. (They have a lot of headaches and tummy aches!) When you are seeing a “shy” school-age child who has persistent crying spells around attending school on test days or before each sporting event despite loving practice, it is useful to gather more history. Is there a family history of anxiety or depression? What are the circumstances of their crying jags or persistent tantrums? Ask teenagers about episodes of shortness of breath, tachycardia, dizziness or sweating that leave them feeling like they are going to die (panic attacks). See if they can rank their anxiety on a scale from 1-10, and find out of there are consistent situations where their anxiety seems disproportionate. Children or teens may recognize that their anxiety is not merited, or they may not. If their parent also suffers from anxiety, they are less likely to recognize that this intense, persistent “shyness” in their child represents a treatable symptom. When you simply have a high index of suspicion, it is worth a referral to a mental health expert to evaluate their anxiety.

Reassuring parents and children that this is a common, treatable problem in childhood will go a long way to diminishing the secrecy and shame that can accompany paralyzing anxiety, and help your patients toward a track that optimizes their psychosocial development.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Many advocating for more attention to psychosocial issues by primary care pediatricians focus on serious conditions and the value of early recognition. For example, early recognition of autism spectrum disorder could lead to earlier intensive treatment that might impact the long-term course. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder very likely will lessen symptoms and also maintain self-esteem under the withering ordeal – often punctuated by teacher comments – of trying to pay attention hour after hour in school

Are there seemingly less serious conditions very likely worthy of early diagnosis, even those on the edge of normal developmental hurdles? One of the essential tasks of childhood is mastering the anxiety that emerges as children face the new challenges of each developmental stage, so parents, teachers, and clinicians are (or need to be) used to bearing anxiety in the children with whom they work. Intense shyness and anxiety around separation from parents are routine and healthy in infants and toddlers from 6-18 months. Anxiety in new social situations, such as the first day of preschool, is the rule, not the exception. School-age children commonly experience a surge of anxiety around performance and independence, as they are managing and mastering new skills in these domains every day. This anxiety can cause distress, but it should get better every time a child faces it, as they become better at managing the situation. When a child has an anxious temperament, poor coping skills, or parents who struggle to manage their own anxiety, children may have a harder time mastering new, anxiety-provoking challenges across settings. But, with time, and even just one adult who patiently models good coping, they will face and manage challenges. Social anxiety disorder is present when specific social or performance situations provoke the same intense anxiety and avoidance over and over, and for more than 6 months.

Most infants and young children who are more timid and fearful seem to grow into a normal range of social behavior, although few become extroverts. Some of these shy children are cautious in new situations for a period of time measured in minutes, but once the situations are familiar, these children are indistinguishable from their peers. However, some of these temperamentally timid children emerge consistently more anxious with greater likelihood to have phobias and to have social anxiety that can seriously impact long term happiness, achievement, and increase risk taking behaviors. A pediatrician should watch and note the emerging pattern of a timid toddler to see if the shyness eases or impacts social functioning; by bending the course of social interactions, social anxiety disorder critically affects developing social skills, self-regulation, affect tolerance, emerging identity, and confidence. Recognition and effective treatment of social anxiety will keep a child on the optimal developmental trajectory.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric illnesses in the United States, and social anxiety disorder (previously labeled as social phobia) is the third most common psychiatric disorder in U.S. adults (after depression and alcohol dependence). Most persistent anxiety disorders begin in childhood, and social anxiety is no exception. The mean age of onset for social anxiety is 13 years old, and it rarely begins after the age of 25, with an annual prevalence around 7% in childhood and adolescence (Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2009;32;483-524).The DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety disorder include, “a marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations in which the person is exposed to unfamiliar people or to possible scrutiny by others,” and exposure to those situations provokes intense anxiety, which in children can be marked by severe or prolonged crying, freezing, tantrums, shrinking from social situations, refusing to speak, or clinging to parents. In adolescents, it may trigger panic attacks. The avoidance and distress interfere with the child’s function in school, social activities, or relationships, and must have lasted for at least 6 months. To ensure that there is not another problem of social relatedness, the child should have shown some capacity to have normal peer relationships.

Will social anxiety disorder be vividly apparent to teachers, parents, and clinicians? No. The feeling of anxiety is an internal experience, not easily observed, and anxious children and teens are rarely eager or comfortable communicators about their own anxiety. Indeed, in a 2007 survey of patients in treatment for anxiety, 36% of people with social anxiety disorder reported experiencing symptoms for 10 or more years before seeking help. It’s true that the distress children experience when feeling intensely anxious will probably be observable, but all of those behaviors (clinging, crying, tantrums) are common and normal expressions of distress in childhood. Even in adolescence, while having a panic attack may prompt the teenager to seek care, she may not connect it with the anxiety she was feeling about being called on in class or talking to peers, especially if that is an anxiety she has experienced for a long time as a daily part of her lives and routines.

Social anxiety disorder is treatable. The first-line treatment in mild to moderate cases, particularly with younger children, is cognitive-behavioral therapy. This is a practical variant of psychotherapy in which children develop and practice skills at recognizing and labeling their own feelings of anxiety, identifying the situations that trigger them, and practicing relaxation strategies that help them to face and manage the anxiety-provoking situations rather than avoiding them.

When symptoms or the degree of impairment are more severe, medications can become an important part of treatment. SSRIs are the first-line medications used to treat social anxiety disorder, and the effective doses are often higher than effective antidepressant doses, although we often titrate toward those doses more slowly with anxious patients to avoid side effects that might increase or exacerbate their anxiety.

Even with effective medication treatment, though, psychotherapy will be an essential part of treatment. These young patients need to build the essential skills of anxiety management, although it is in the nature of anxiety that such patients often wish to dissolve their anxiety by simply using a pill.

Anxiety disorders are typically chronic and will persist without effective treatment. Failure to recognize and treat social anxiety disorder can distort or even derail healthy development and may result in major psychiatric complications. As a pediatrician, you are trying to stop or modify a chain of potential events. Imagine a socially anxious young woman who enters puberty in high school. Will she withdraw from social activities? Will she avoid new opportunities or interests? Will alcohol become a necessary social lubricant? Will she be at increased risk for sexual assault at a party or poor grades in school? Will social anxiety affect her choice of college, fearful of leaving home? The incidence of secondary depression and substance abuse disorders is substantially higher in adolescents with untreated anxiety disorders. Although a depressed, alcohol-dependent teenager is more likely to be recognized as needing treatment, once they have developed those complications, effective treatment of the underlying anxiety will be much more complicated and slow to treat. Prevention starting before puberty is a much more desirable approach.

Pediatricians truly do have the opportunity to improve outcomes for these patients, by learning to recognize this sometimes-invisible disorder. Children suffering from anxiety disorders are more likely to identify a physical concern than a psychological one. (They have a lot of headaches and tummy aches!) When you are seeing a “shy” school-age child who has persistent crying spells around attending school on test days or before each sporting event despite loving practice, it is useful to gather more history. Is there a family history of anxiety or depression? What are the circumstances of their crying jags or persistent tantrums? Ask teenagers about episodes of shortness of breath, tachycardia, dizziness or sweating that leave them feeling like they are going to die (panic attacks). See if they can rank their anxiety on a scale from 1-10, and find out of there are consistent situations where their anxiety seems disproportionate. Children or teens may recognize that their anxiety is not merited, or they may not. If their parent also suffers from anxiety, they are less likely to recognize that this intense, persistent “shyness” in their child represents a treatable symptom. When you simply have a high index of suspicion, it is worth a referral to a mental health expert to evaluate their anxiety.

Reassuring parents and children that this is a common, treatable problem in childhood will go a long way to diminishing the secrecy and shame that can accompany paralyzing anxiety, and help your patients toward a track that optimizes their psychosocial development.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Many advocating for more attention to psychosocial issues by primary care pediatricians focus on serious conditions and the value of early recognition. For example, early recognition of autism spectrum disorder could lead to earlier intensive treatment that might impact the long-term course. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder very likely will lessen symptoms and also maintain self-esteem under the withering ordeal – often punctuated by teacher comments – of trying to pay attention hour after hour in school

Are there seemingly less serious conditions very likely worthy of early diagnosis, even those on the edge of normal developmental hurdles? One of the essential tasks of childhood is mastering the anxiety that emerges as children face the new challenges of each developmental stage, so parents, teachers, and clinicians are (or need to be) used to bearing anxiety in the children with whom they work. Intense shyness and anxiety around separation from parents are routine and healthy in infants and toddlers from 6-18 months. Anxiety in new social situations, such as the first day of preschool, is the rule, not the exception. School-age children commonly experience a surge of anxiety around performance and independence, as they are managing and mastering new skills in these domains every day. This anxiety can cause distress, but it should get better every time a child faces it, as they become better at managing the situation. When a child has an anxious temperament, poor coping skills, or parents who struggle to manage their own anxiety, children may have a harder time mastering new, anxiety-provoking challenges across settings. But, with time, and even just one adult who patiently models good coping, they will face and manage challenges. Social anxiety disorder is present when specific social or performance situations provoke the same intense anxiety and avoidance over and over, and for more than 6 months.

Most infants and young children who are more timid and fearful seem to grow into a normal range of social behavior, although few become extroverts. Some of these shy children are cautious in new situations for a period of time measured in minutes, but once the situations are familiar, these children are indistinguishable from their peers. However, some of these temperamentally timid children emerge consistently more anxious with greater likelihood to have phobias and to have social anxiety that can seriously impact long term happiness, achievement, and increase risk taking behaviors. A pediatrician should watch and note the emerging pattern of a timid toddler to see if the shyness eases or impacts social functioning; by bending the course of social interactions, social anxiety disorder critically affects developing social skills, self-regulation, affect tolerance, emerging identity, and confidence. Recognition and effective treatment of social anxiety will keep a child on the optimal developmental trajectory.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric illnesses in the United States, and social anxiety disorder (previously labeled as social phobia) is the third most common psychiatric disorder in U.S. adults (after depression and alcohol dependence). Most persistent anxiety disorders begin in childhood, and social anxiety is no exception. The mean age of onset for social anxiety is 13 years old, and it rarely begins after the age of 25, with an annual prevalence around 7% in childhood and adolescence (Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2009;32;483-524).The DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety disorder include, “a marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations in which the person is exposed to unfamiliar people or to possible scrutiny by others,” and exposure to those situations provokes intense anxiety, which in children can be marked by severe or prolonged crying, freezing, tantrums, shrinking from social situations, refusing to speak, or clinging to parents. In adolescents, it may trigger panic attacks. The avoidance and distress interfere with the child’s function in school, social activities, or relationships, and must have lasted for at least 6 months. To ensure that there is not another problem of social relatedness, the child should have shown some capacity to have normal peer relationships.

Will social anxiety disorder be vividly apparent to teachers, parents, and clinicians? No. The feeling of anxiety is an internal experience, not easily observed, and anxious children and teens are rarely eager or comfortable communicators about their own anxiety. Indeed, in a 2007 survey of patients in treatment for anxiety, 36% of people with social anxiety disorder reported experiencing symptoms for 10 or more years before seeking help. It’s true that the distress children experience when feeling intensely anxious will probably be observable, but all of those behaviors (clinging, crying, tantrums) are common and normal expressions of distress in childhood. Even in adolescence, while having a panic attack may prompt the teenager to seek care, she may not connect it with the anxiety she was feeling about being called on in class or talking to peers, especially if that is an anxiety she has experienced for a long time as a daily part of her lives and routines.

Social anxiety disorder is treatable. The first-line treatment in mild to moderate cases, particularly with younger children, is cognitive-behavioral therapy. This is a practical variant of psychotherapy in which children develop and practice skills at recognizing and labeling their own feelings of anxiety, identifying the situations that trigger them, and practicing relaxation strategies that help them to face and manage the anxiety-provoking situations rather than avoiding them.

When symptoms or the degree of impairment are more severe, medications can become an important part of treatment. SSRIs are the first-line medications used to treat social anxiety disorder, and the effective doses are often higher than effective antidepressant doses, although we often titrate toward those doses more slowly with anxious patients to avoid side effects that might increase or exacerbate their anxiety.

Even with effective medication treatment, though, psychotherapy will be an essential part of treatment. These young patients need to build the essential skills of anxiety management, although it is in the nature of anxiety that such patients often wish to dissolve their anxiety by simply using a pill.

Anxiety disorders are typically chronic and will persist without effective treatment. Failure to recognize and treat social anxiety disorder can distort or even derail healthy development and may result in major psychiatric complications. As a pediatrician, you are trying to stop or modify a chain of potential events. Imagine a socially anxious young woman who enters puberty in high school. Will she withdraw from social activities? Will she avoid new opportunities or interests? Will alcohol become a necessary social lubricant? Will she be at increased risk for sexual assault at a party or poor grades in school? Will social anxiety affect her choice of college, fearful of leaving home? The incidence of secondary depression and substance abuse disorders is substantially higher in adolescents with untreated anxiety disorders. Although a depressed, alcohol-dependent teenager is more likely to be recognized as needing treatment, once they have developed those complications, effective treatment of the underlying anxiety will be much more complicated and slow to treat. Prevention starting before puberty is a much more desirable approach.

Pediatricians truly do have the opportunity to improve outcomes for these patients, by learning to recognize this sometimes-invisible disorder. Children suffering from anxiety disorders are more likely to identify a physical concern than a psychological one. (They have a lot of headaches and tummy aches!) When you are seeing a “shy” school-age child who has persistent crying spells around attending school on test days or before each sporting event despite loving practice, it is useful to gather more history. Is there a family history of anxiety or depression? What are the circumstances of their crying jags or persistent tantrums? Ask teenagers about episodes of shortness of breath, tachycardia, dizziness or sweating that leave them feeling like they are going to die (panic attacks). See if they can rank their anxiety on a scale from 1-10, and find out of there are consistent situations where their anxiety seems disproportionate. Children or teens may recognize that their anxiety is not merited, or they may not. If their parent also suffers from anxiety, they are less likely to recognize that this intense, persistent “shyness” in their child represents a treatable symptom. When you simply have a high index of suspicion, it is worth a referral to a mental health expert to evaluate their anxiety.

Reassuring parents and children that this is a common, treatable problem in childhood will go a long way to diminishing the secrecy and shame that can accompany paralyzing anxiety, and help your patients toward a track that optimizes their psychosocial development.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Retire, Who Me?

Okay, so I didn’t last long as a VA retiree. My original plan was to hang it up entirely when I stepped down from my longstanding (27 years!) position as chief of medicine at the Phoenix VA Health Care System (VAHCS) at the end of June 2014. As some longtime readers may recall, my wife, Susan, has had a severe case of Sjögren’s syndrome for many years, and her symptoms have worsened progressively recently.

Our vacation home seemed a logical place to retire to, since it is in a more humid and oceanside California climate, and my wife could have some hope of breathing easier. As long as our youngest son was in high school in Phoenix, I had an excuse to stay in Arizona, but he graduated at the end of June.

Related: What's Wrong With My Wife?

Thus, all the stars aligned and I made my formal e-mail announcement to my troops in the Department of Medicine on February 14. The access scandal whose epicenter was the Phoenix VAHCS hit a couple of months later in April, and the horrendous press that ensued seemed to confirm that I should retire.

I mention these dates to counter the suspicion that I got out of Dodge because things got rough. Nothing could be further from the truth: I had to be practically dragged kicking and screaming from my office when the time arrived. I was not an enthusiastic retiree.

By early May I was already worrying about the idleness and boredom I assumed would be the hallmarks of true retirement. So I began to search frantically online for employment opportunities near our home. As it turned out, the best employment opportunity in the area was at a VA contract clinic in Oxnard. The clinic is a fully integrated part of the Greater Los Angeles VAHCS operated by Humana Government Services, not the VA.

I surprised myself by jumping at the opportunity to continue to work in a medical setting, especially one with a strong VA flavor. But I became increasingly apprehensive as the planned start date of August 4 approached. After all, for years I had had a vast array of hardworking medical helpers standing between me and the patients, including medical students, interns, residents, endocrine fellows, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who would do almost all the direct patient care. I would occasionally visit with the patient who was not content to interact exclusively with my designated assistant or when an earnest trainee felt that I needed to assess a patient’s unique situation or concern.

Related: Keeping an Open Mind on HRT

But a small miracle has enveloped me since I began working at the Oxnard clinic. I have found that I enjoy taking care of the nonstop parade of dyslipidemic hypertensive diabetic patients who constitute the huge majority of those I see. Yes, there are many times when I wish I could sit back in my chair and unravel knotty organizational problems as I did at my previous job. And I also have persistent fantasies of sitting in my beach chair, drinking strong martinis while staring at the ever-fascinating waves of the nearby Pacific.

However, I have come to realize that I am truly a restless person. As long as there is some potential medical good to be achieved, I am hell- bent on making it happen if I can. While not all physicians share this philosophy, I strongly believe that the practice of medicine is a lifelong professional commitment that can be very difficult for many of us to walk away from. I certainly don’t know how long I’ll last in my new post. What could well drive me away is the almost-frantic pace of modern health care delivery, a pace that is largely determined by the tyranny of the electronic medical record, a monster who must be fed at all costs (more on this in the future). But for now, the need to contribute to the medical endeavor has proven considerably stronger than the countervailing desire for a quiet and comfortable retirement.

Related: Landmark Initiative Signed for Homeless Veterans

Don’t call me crazy just yet; instead, please follow the lead of my mostly grateful patients and call me doctor. That’s an honorific that’s still meaningful to me, and it keeps me slogging onward in spite of the many obstacles.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies.

Okay, so I didn’t last long as a VA retiree. My original plan was to hang it up entirely when I stepped down from my longstanding (27 years!) position as chief of medicine at the Phoenix VA Health Care System (VAHCS) at the end of June 2014. As some longtime readers may recall, my wife, Susan, has had a severe case of Sjögren’s syndrome for many years, and her symptoms have worsened progressively recently.

Our vacation home seemed a logical place to retire to, since it is in a more humid and oceanside California climate, and my wife could have some hope of breathing easier. As long as our youngest son was in high school in Phoenix, I had an excuse to stay in Arizona, but he graduated at the end of June.

Related: What's Wrong With My Wife?

Thus, all the stars aligned and I made my formal e-mail announcement to my troops in the Department of Medicine on February 14. The access scandal whose epicenter was the Phoenix VAHCS hit a couple of months later in April, and the horrendous press that ensued seemed to confirm that I should retire.

I mention these dates to counter the suspicion that I got out of Dodge because things got rough. Nothing could be further from the truth: I had to be practically dragged kicking and screaming from my office when the time arrived. I was not an enthusiastic retiree.

By early May I was already worrying about the idleness and boredom I assumed would be the hallmarks of true retirement. So I began to search frantically online for employment opportunities near our home. As it turned out, the best employment opportunity in the area was at a VA contract clinic in Oxnard. The clinic is a fully integrated part of the Greater Los Angeles VAHCS operated by Humana Government Services, not the VA.

I surprised myself by jumping at the opportunity to continue to work in a medical setting, especially one with a strong VA flavor. But I became increasingly apprehensive as the planned start date of August 4 approached. After all, for years I had had a vast array of hardworking medical helpers standing between me and the patients, including medical students, interns, residents, endocrine fellows, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who would do almost all the direct patient care. I would occasionally visit with the patient who was not content to interact exclusively with my designated assistant or when an earnest trainee felt that I needed to assess a patient’s unique situation or concern.

Related: Keeping an Open Mind on HRT

But a small miracle has enveloped me since I began working at the Oxnard clinic. I have found that I enjoy taking care of the nonstop parade of dyslipidemic hypertensive diabetic patients who constitute the huge majority of those I see. Yes, there are many times when I wish I could sit back in my chair and unravel knotty organizational problems as I did at my previous job. And I also have persistent fantasies of sitting in my beach chair, drinking strong martinis while staring at the ever-fascinating waves of the nearby Pacific.

However, I have come to realize that I am truly a restless person. As long as there is some potential medical good to be achieved, I am hell- bent on making it happen if I can. While not all physicians share this philosophy, I strongly believe that the practice of medicine is a lifelong professional commitment that can be very difficult for many of us to walk away from. I certainly don’t know how long I’ll last in my new post. What could well drive me away is the almost-frantic pace of modern health care delivery, a pace that is largely determined by the tyranny of the electronic medical record, a monster who must be fed at all costs (more on this in the future). But for now, the need to contribute to the medical endeavor has proven considerably stronger than the countervailing desire for a quiet and comfortable retirement.

Related: Landmark Initiative Signed for Homeless Veterans

Don’t call me crazy just yet; instead, please follow the lead of my mostly grateful patients and call me doctor. That’s an honorific that’s still meaningful to me, and it keeps me slogging onward in spite of the many obstacles.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies.

Okay, so I didn’t last long as a VA retiree. My original plan was to hang it up entirely when I stepped down from my longstanding (27 years!) position as chief of medicine at the Phoenix VA Health Care System (VAHCS) at the end of June 2014. As some longtime readers may recall, my wife, Susan, has had a severe case of Sjögren’s syndrome for many years, and her symptoms have worsened progressively recently.

Our vacation home seemed a logical place to retire to, since it is in a more humid and oceanside California climate, and my wife could have some hope of breathing easier. As long as our youngest son was in high school in Phoenix, I had an excuse to stay in Arizona, but he graduated at the end of June.

Related: What's Wrong With My Wife?

Thus, all the stars aligned and I made my formal e-mail announcement to my troops in the Department of Medicine on February 14. The access scandal whose epicenter was the Phoenix VAHCS hit a couple of months later in April, and the horrendous press that ensued seemed to confirm that I should retire.

I mention these dates to counter the suspicion that I got out of Dodge because things got rough. Nothing could be further from the truth: I had to be practically dragged kicking and screaming from my office when the time arrived. I was not an enthusiastic retiree.

By early May I was already worrying about the idleness and boredom I assumed would be the hallmarks of true retirement. So I began to search frantically online for employment opportunities near our home. As it turned out, the best employment opportunity in the area was at a VA contract clinic in Oxnard. The clinic is a fully integrated part of the Greater Los Angeles VAHCS operated by Humana Government Services, not the VA.

I surprised myself by jumping at the opportunity to continue to work in a medical setting, especially one with a strong VA flavor. But I became increasingly apprehensive as the planned start date of August 4 approached. After all, for years I had had a vast array of hardworking medical helpers standing between me and the patients, including medical students, interns, residents, endocrine fellows, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who would do almost all the direct patient care. I would occasionally visit with the patient who was not content to interact exclusively with my designated assistant or when an earnest trainee felt that I needed to assess a patient’s unique situation or concern.

Related: Keeping an Open Mind on HRT

But a small miracle has enveloped me since I began working at the Oxnard clinic. I have found that I enjoy taking care of the nonstop parade of dyslipidemic hypertensive diabetic patients who constitute the huge majority of those I see. Yes, there are many times when I wish I could sit back in my chair and unravel knotty organizational problems as I did at my previous job. And I also have persistent fantasies of sitting in my beach chair, drinking strong martinis while staring at the ever-fascinating waves of the nearby Pacific.

However, I have come to realize that I am truly a restless person. As long as there is some potential medical good to be achieved, I am hell- bent on making it happen if I can. While not all physicians share this philosophy, I strongly believe that the practice of medicine is a lifelong professional commitment that can be very difficult for many of us to walk away from. I certainly don’t know how long I’ll last in my new post. What could well drive me away is the almost-frantic pace of modern health care delivery, a pace that is largely determined by the tyranny of the electronic medical record, a monster who must be fed at all costs (more on this in the future). But for now, the need to contribute to the medical endeavor has proven considerably stronger than the countervailing desire for a quiet and comfortable retirement.

Related: Landmark Initiative Signed for Homeless Veterans

Don’t call me crazy just yet; instead, please follow the lead of my mostly grateful patients and call me doctor. That’s an honorific that’s still meaningful to me, and it keeps me slogging onward in spite of the many obstacles.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies.

Committed to Showing Results at the VA

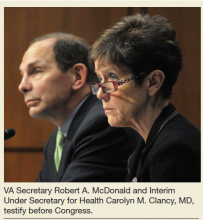

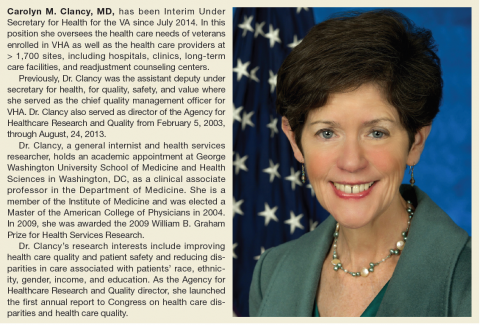

Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, was named Interim Under Secretary for Health for the VA on July 2, 2014, just as the wait time crisis seemed to be spinning out of control. Her appointment and the confirmation of Secretary Robert A. McDonald less than a month later proved essential to calming the furor but were admittedly just the first steps in a long-term process to increase veterans’ access to care and develop better systems and procedures across the agency.

Six months after her appointment, Federal Practitioner talked with Dr. Clancy about the pace of change and the role of health care providers in improving care for veterans. In the interview, Dr. Clancy clearly noted that many VA facilities already represent the best of U.S. health care and that the path forward requires sharing of best practices. Many other facilities, of course, will have to change, but Dr. Clancy insisted it is “an incredible opportunity” for the VA to learn as a system. Perhaps most heartening to VA practitioners, Dr. Clancy also recognized that “you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best.”

To be sure, any successful change in VA procedures and culture will require buy-in not only from across the agency, but also from veterans and Congress. Dr. Clancy has already received 2 votes of confidence: The Paralyzed Veterans of America and the Vietnam Veterans of America jointly called on President Obama to make Dr. Clancy’s appointment permanent. The White House and congressional leaders, however, have yet to schedule hearings or comment publicly.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, including an in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Taking Measure of VA Strengths

Interim Under Secretary for Health Carolyn M. Clancy, MD. I came to this system in August of 2013 after more than 20 years at HHS, all working for an agency that had the lead charge for funding research to improve quality and safety in health care; and I had spent the last 10 years prior to coming here as the director of that agency. I came to VHA because I thought this system was unique among all systems, public and private, in this country and had the strongest foundation in place to deliver 21st century health care. And at least as important—probably more so—was the sense of mission among all of the employees I met. These were people I’ve known in academia, people I met on the interviews, people I’ve intersected with for a number of years in the research community. You can’t replicate it, and you can’t buy it; and I figured the combination of a strong foundation and mission meant that this was one of the best systems to work for.

I still think that. Some of our best facilities could compete head to head with any facilities in the private sector. There is no question about that. We have some systems, facilities, and clinics that are struggling as well, which is also very typical of the private sector.

What we have is an incredible opportunity, first, because we have a fabulous mission. We have highly committed and dedicated employees. We have an incredible opportunity to actually learn as a system. There has been a lot of discussion at a number of levels about how health care in the new century needs to be a learning health care system. We actually have the capability of delivering on that promise. So I’m very, very excited.

VA Clinical Staff and Recruitment

Dr. Clancy. I have often observed that change can be scary, but it’s also incredibly liberating. Some of our most dedicated employees, I know, can be frustrated, because they feel like they’re doing their part; but they aren’t always sure that the members of the team are as dedicated as they are or are going to catch the ball. And there’s no question that you don’t get to high-quality care without a good team. In other words, superb health care and exceptional veteran experience is a team sport by definition.

So I think it will actually help the vast majority of our frontline clinicians. It’ll be much, much easier for them to deliver the kind of care they want to deliver every single day but sometimes feel like they get stuck in workarounds.