User login

Will Testosterone Replacement Therapy Kill Your Patient?

At first it seems to be a fairly straightforward proposition. The older gentleman you are seeing in the clinic reports that he has been running rather low on energy in recent weeks, and he also mentions that there’s not much lead in his pencil these days. As a conscientious clinician, you immediately entertain the possibility that hypogonadism might explain some of his symptoms. You dutifully order up a total testosterone level, and then a free testosterone level when the total comes back low, recognizing that binding protein abnormalities might produce a low total even when the clinically relevant free level is still normal. Both levels do come back well below the age-adjusted lower limits of normal, which gives you some transient level of satisfaction that you have identified a very significant factor contributing to your patient’s difficulties.

You have confirmed a deficiency of a major hormone, and it seems logical that you would want to restore the hormone level to normal in this particular patient. But before you reach for your prescription pad (or your mouse), a fundamental question hangs uneasily in the air. Are you going to be doing more harm than good by prescribing testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) to this rather trusting older fellow? In light of recent studies, might you actually increase this patent’s chances of a heart attack or a stroke? That would not be a nice thing to do to this pleasant older gentleman. (As a newly minted senior citizen, I pray mightily that my own caregivers adhere rigorously to Hippocrates’ hoary admonition to, above all, do no harm.)

I’m not going to be able to resolve this clinical conundrum definitively in this editorial. (Please don’t stop reading just yet!) But maybe a review of the pros and cons for testosterone replacement therapy can help you faithful readers gain just a little bit better sense of the operative risk/benefit considerations at play here.

Let’s look first at the case for prescribing TRT when the laboratory test values show definitive evidence of low testosterone levels. I don’t want to delve into the distracting issue of which form of testosterone replacement to consider, which pits injections vs gels vs patches vs pills (don’t use the potentially hepatotoxic methyltestosterone pills passed out like candy by some urologists). Apart from the possibly relevant issue of peaks and troughs seen with injection therapy, the same risk/benefit considerations pretty much apply to all forms of TRT.

The benefits of TRT clearly include an increase in lean muscle mass, an increase in red blood cell concentration due to the hematopoetic effects of the male hormone, and a reduction in both the total amount and the percentage of body fat. A number of studies have shown that testosterone enhances insulin sensitivity—surely a good thing given the massive number of older patients with either prediabetes or full-blown type 2 diabetes. Some men also report a significant increase in their hard-to-define-but-still important sense of manliness, and sometimes a major improvement in their ability to perform in the sack. The latter effects, though, are often very modest and of considerably less potency (sorry, pun intended) than seen with sildenafil or one of the other PDE-5 inhibitors. In spite of all these seemingly positive effects, the clear majority of men report that they really don’t feel much different after starting on TRT, and many discontinue it on their own after relatively short periods, especially those enduring intramuscular injections every 2 weeks.

So the benefits derived from TRT are not really very impressive in many patients. What about the downside of giving testosterone? Surely there can’t be any problems associated with simply replacing an important hormone that has fallen to low levels? After all, we don’t hesitate to give thyroid hormone to hypothyroid patients, to give growth hormone to children with low levels of this critical hormone, or to give insulin to diabetic patients whose pancreases are not producing enough of that life-saving hormone.

For a very long time the risk/benefit arguments over whether or not to give TRT were almost entirely theoretical. Those in favor cited the several aforementioned benefits, and those in opposition decried replacement therapy as a perverse form of tinkering with nature by trying to alter the natural decline in the levels of certain hormones that were part and parcel of the natural aging process.

Then along came 3 rather worrisome studies in fairly rapid-fire succession, which seamed collectively to deliver a true body blow to TRT. However, a closer examination of these studies reveals that each is so severely flawed that no meaningful conclusions can be derived from any of them.

The Testosterone in Older Men with Sarcopenia (TOM) trial was a randomized trial of TRT vs placebo in older men (mean age 74 years) with mobility limitations (sarcopenia, after all, means decreased muscle bulk) and a high prevalence of chronic disease.1 The trial was stopped early because of a much higher occurrence of self-reported cardiovascular-related adverse events. However, these adverse events were extremely disparate and were all self-reported; none had been prespecified outcomes. Any objective observer would have to conclude that the study was poorly designed and that no meaningful conclusions can be drawn from its premature termination.

The second trial that seemed to cast doubt on the safety of TRT suffered from an even worse design. It was a retrospective cohort study of 8,709 veterans aged 60 to 64 years with low testosterone levels who were undergoing coronary artery angiography. The authors reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that those receiving testosterone therapy had a higher risk of experiencing a composite outcome of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), or cerebrovascular accident than did those who had not received testosterone therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04-1.58).2 Right off the bat, you should be very wary of any HR emanating from a retrospective study that shows a small increase in risk of 29%; it’s only when a HR is 2.0 or more that it’s likely you’re looking at a real phenomenon. But to add insult to injury, the percentage of actual adverse outcomes was actually SMALLER in those taking testosterone than in those who did not get any! The authors had used such an incredibly tortured series of risk adjustments for a variety of comorbidities that they actually managed to stand the raw numbers on their head.

The third study, which had seamed at first blush to demonstrate cardiovascular toxicity of TRT, was a much larger retrospective cohort study of 55,793 men who had received replacement testosterone.3 The authors reported an increase in the relative risk of MI in the first 3 months after starting testosterone compared with the risk of MI in the same men in the prior year (relative risk [RR] = 1.36). However, the much more important absolute risk increase was very, very low, with only an additional 1.25 cases of MI seen over 1,000 patient-years. Apart from the fact that a RR of 1.36 is most unimpressive in a retrospective study, the simple fact that the men were older by a few months after TRT is probably more than adequate to explain this tiny increase in apparent risk.

The FDA has monitored these studies closely and has chosen not to make a determination that there is an increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with TRT. That is not at all the same as saying that it has been proven to be completely free of cardiovascular risk; rather it is a common-sense acknowledgment that there is not any convincing evidence to date of such a risk.

Thus, the conscientious clinician is left to conclude that TRT is a reasonable option in symptomatic patients who have been shown to have low levels of free testosterone. It has not been conclusively demonstrated that TRT will have significant beneficial effects, but neither has it been proven to have any true cardiovascular toxicity. It is a therapy worth trying in those symptomatic patients who understand that they will be receiving therapy of uncertain benefit, if any, and with the possibility of uncertain risk, if any.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, Connolly MJ, et al. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men; A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):639-650.

2. Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1829-1836.

3. Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PloS One. 2014;9(1):e85805 Epub.

At first it seems to be a fairly straightforward proposition. The older gentleman you are seeing in the clinic reports that he has been running rather low on energy in recent weeks, and he also mentions that there’s not much lead in his pencil these days. As a conscientious clinician, you immediately entertain the possibility that hypogonadism might explain some of his symptoms. You dutifully order up a total testosterone level, and then a free testosterone level when the total comes back low, recognizing that binding protein abnormalities might produce a low total even when the clinically relevant free level is still normal. Both levels do come back well below the age-adjusted lower limits of normal, which gives you some transient level of satisfaction that you have identified a very significant factor contributing to your patient’s difficulties.

You have confirmed a deficiency of a major hormone, and it seems logical that you would want to restore the hormone level to normal in this particular patient. But before you reach for your prescription pad (or your mouse), a fundamental question hangs uneasily in the air. Are you going to be doing more harm than good by prescribing testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) to this rather trusting older fellow? In light of recent studies, might you actually increase this patent’s chances of a heart attack or a stroke? That would not be a nice thing to do to this pleasant older gentleman. (As a newly minted senior citizen, I pray mightily that my own caregivers adhere rigorously to Hippocrates’ hoary admonition to, above all, do no harm.)

I’m not going to be able to resolve this clinical conundrum definitively in this editorial. (Please don’t stop reading just yet!) But maybe a review of the pros and cons for testosterone replacement therapy can help you faithful readers gain just a little bit better sense of the operative risk/benefit considerations at play here.

Let’s look first at the case for prescribing TRT when the laboratory test values show definitive evidence of low testosterone levels. I don’t want to delve into the distracting issue of which form of testosterone replacement to consider, which pits injections vs gels vs patches vs pills (don’t use the potentially hepatotoxic methyltestosterone pills passed out like candy by some urologists). Apart from the possibly relevant issue of peaks and troughs seen with injection therapy, the same risk/benefit considerations pretty much apply to all forms of TRT.

The benefits of TRT clearly include an increase in lean muscle mass, an increase in red blood cell concentration due to the hematopoetic effects of the male hormone, and a reduction in both the total amount and the percentage of body fat. A number of studies have shown that testosterone enhances insulin sensitivity—surely a good thing given the massive number of older patients with either prediabetes or full-blown type 2 diabetes. Some men also report a significant increase in their hard-to-define-but-still important sense of manliness, and sometimes a major improvement in their ability to perform in the sack. The latter effects, though, are often very modest and of considerably less potency (sorry, pun intended) than seen with sildenafil or one of the other PDE-5 inhibitors. In spite of all these seemingly positive effects, the clear majority of men report that they really don’t feel much different after starting on TRT, and many discontinue it on their own after relatively short periods, especially those enduring intramuscular injections every 2 weeks.

So the benefits derived from TRT are not really very impressive in many patients. What about the downside of giving testosterone? Surely there can’t be any problems associated with simply replacing an important hormone that has fallen to low levels? After all, we don’t hesitate to give thyroid hormone to hypothyroid patients, to give growth hormone to children with low levels of this critical hormone, or to give insulin to diabetic patients whose pancreases are not producing enough of that life-saving hormone.

For a very long time the risk/benefit arguments over whether or not to give TRT were almost entirely theoretical. Those in favor cited the several aforementioned benefits, and those in opposition decried replacement therapy as a perverse form of tinkering with nature by trying to alter the natural decline in the levels of certain hormones that were part and parcel of the natural aging process.

Then along came 3 rather worrisome studies in fairly rapid-fire succession, which seamed collectively to deliver a true body blow to TRT. However, a closer examination of these studies reveals that each is so severely flawed that no meaningful conclusions can be derived from any of them.

The Testosterone in Older Men with Sarcopenia (TOM) trial was a randomized trial of TRT vs placebo in older men (mean age 74 years) with mobility limitations (sarcopenia, after all, means decreased muscle bulk) and a high prevalence of chronic disease.1 The trial was stopped early because of a much higher occurrence of self-reported cardiovascular-related adverse events. However, these adverse events were extremely disparate and were all self-reported; none had been prespecified outcomes. Any objective observer would have to conclude that the study was poorly designed and that no meaningful conclusions can be drawn from its premature termination.

The second trial that seemed to cast doubt on the safety of TRT suffered from an even worse design. It was a retrospective cohort study of 8,709 veterans aged 60 to 64 years with low testosterone levels who were undergoing coronary artery angiography. The authors reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that those receiving testosterone therapy had a higher risk of experiencing a composite outcome of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), or cerebrovascular accident than did those who had not received testosterone therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04-1.58).2 Right off the bat, you should be very wary of any HR emanating from a retrospective study that shows a small increase in risk of 29%; it’s only when a HR is 2.0 or more that it’s likely you’re looking at a real phenomenon. But to add insult to injury, the percentage of actual adverse outcomes was actually SMALLER in those taking testosterone than in those who did not get any! The authors had used such an incredibly tortured series of risk adjustments for a variety of comorbidities that they actually managed to stand the raw numbers on their head.

The third study, which had seamed at first blush to demonstrate cardiovascular toxicity of TRT, was a much larger retrospective cohort study of 55,793 men who had received replacement testosterone.3 The authors reported an increase in the relative risk of MI in the first 3 months after starting testosterone compared with the risk of MI in the same men in the prior year (relative risk [RR] = 1.36). However, the much more important absolute risk increase was very, very low, with only an additional 1.25 cases of MI seen over 1,000 patient-years. Apart from the fact that a RR of 1.36 is most unimpressive in a retrospective study, the simple fact that the men were older by a few months after TRT is probably more than adequate to explain this tiny increase in apparent risk.

The FDA has monitored these studies closely and has chosen not to make a determination that there is an increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with TRT. That is not at all the same as saying that it has been proven to be completely free of cardiovascular risk; rather it is a common-sense acknowledgment that there is not any convincing evidence to date of such a risk.

Thus, the conscientious clinician is left to conclude that TRT is a reasonable option in symptomatic patients who have been shown to have low levels of free testosterone. It has not been conclusively demonstrated that TRT will have significant beneficial effects, but neither has it been proven to have any true cardiovascular toxicity. It is a therapy worth trying in those symptomatic patients who understand that they will be receiving therapy of uncertain benefit, if any, and with the possibility of uncertain risk, if any.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

At first it seems to be a fairly straightforward proposition. The older gentleman you are seeing in the clinic reports that he has been running rather low on energy in recent weeks, and he also mentions that there’s not much lead in his pencil these days. As a conscientious clinician, you immediately entertain the possibility that hypogonadism might explain some of his symptoms. You dutifully order up a total testosterone level, and then a free testosterone level when the total comes back low, recognizing that binding protein abnormalities might produce a low total even when the clinically relevant free level is still normal. Both levels do come back well below the age-adjusted lower limits of normal, which gives you some transient level of satisfaction that you have identified a very significant factor contributing to your patient’s difficulties.

You have confirmed a deficiency of a major hormone, and it seems logical that you would want to restore the hormone level to normal in this particular patient. But before you reach for your prescription pad (or your mouse), a fundamental question hangs uneasily in the air. Are you going to be doing more harm than good by prescribing testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) to this rather trusting older fellow? In light of recent studies, might you actually increase this patent’s chances of a heart attack or a stroke? That would not be a nice thing to do to this pleasant older gentleman. (As a newly minted senior citizen, I pray mightily that my own caregivers adhere rigorously to Hippocrates’ hoary admonition to, above all, do no harm.)

I’m not going to be able to resolve this clinical conundrum definitively in this editorial. (Please don’t stop reading just yet!) But maybe a review of the pros and cons for testosterone replacement therapy can help you faithful readers gain just a little bit better sense of the operative risk/benefit considerations at play here.

Let’s look first at the case for prescribing TRT when the laboratory test values show definitive evidence of low testosterone levels. I don’t want to delve into the distracting issue of which form of testosterone replacement to consider, which pits injections vs gels vs patches vs pills (don’t use the potentially hepatotoxic methyltestosterone pills passed out like candy by some urologists). Apart from the possibly relevant issue of peaks and troughs seen with injection therapy, the same risk/benefit considerations pretty much apply to all forms of TRT.

The benefits of TRT clearly include an increase in lean muscle mass, an increase in red blood cell concentration due to the hematopoetic effects of the male hormone, and a reduction in both the total amount and the percentage of body fat. A number of studies have shown that testosterone enhances insulin sensitivity—surely a good thing given the massive number of older patients with either prediabetes or full-blown type 2 diabetes. Some men also report a significant increase in their hard-to-define-but-still important sense of manliness, and sometimes a major improvement in their ability to perform in the sack. The latter effects, though, are often very modest and of considerably less potency (sorry, pun intended) than seen with sildenafil or one of the other PDE-5 inhibitors. In spite of all these seemingly positive effects, the clear majority of men report that they really don’t feel much different after starting on TRT, and many discontinue it on their own after relatively short periods, especially those enduring intramuscular injections every 2 weeks.

So the benefits derived from TRT are not really very impressive in many patients. What about the downside of giving testosterone? Surely there can’t be any problems associated with simply replacing an important hormone that has fallen to low levels? After all, we don’t hesitate to give thyroid hormone to hypothyroid patients, to give growth hormone to children with low levels of this critical hormone, or to give insulin to diabetic patients whose pancreases are not producing enough of that life-saving hormone.

For a very long time the risk/benefit arguments over whether or not to give TRT were almost entirely theoretical. Those in favor cited the several aforementioned benefits, and those in opposition decried replacement therapy as a perverse form of tinkering with nature by trying to alter the natural decline in the levels of certain hormones that were part and parcel of the natural aging process.

Then along came 3 rather worrisome studies in fairly rapid-fire succession, which seamed collectively to deliver a true body blow to TRT. However, a closer examination of these studies reveals that each is so severely flawed that no meaningful conclusions can be derived from any of them.

The Testosterone in Older Men with Sarcopenia (TOM) trial was a randomized trial of TRT vs placebo in older men (mean age 74 years) with mobility limitations (sarcopenia, after all, means decreased muscle bulk) and a high prevalence of chronic disease.1 The trial was stopped early because of a much higher occurrence of self-reported cardiovascular-related adverse events. However, these adverse events were extremely disparate and were all self-reported; none had been prespecified outcomes. Any objective observer would have to conclude that the study was poorly designed and that no meaningful conclusions can be drawn from its premature termination.

The second trial that seemed to cast doubt on the safety of TRT suffered from an even worse design. It was a retrospective cohort study of 8,709 veterans aged 60 to 64 years with low testosterone levels who were undergoing coronary artery angiography. The authors reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that those receiving testosterone therapy had a higher risk of experiencing a composite outcome of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), or cerebrovascular accident than did those who had not received testosterone therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04-1.58).2 Right off the bat, you should be very wary of any HR emanating from a retrospective study that shows a small increase in risk of 29%; it’s only when a HR is 2.0 or more that it’s likely you’re looking at a real phenomenon. But to add insult to injury, the percentage of actual adverse outcomes was actually SMALLER in those taking testosterone than in those who did not get any! The authors had used such an incredibly tortured series of risk adjustments for a variety of comorbidities that they actually managed to stand the raw numbers on their head.

The third study, which had seamed at first blush to demonstrate cardiovascular toxicity of TRT, was a much larger retrospective cohort study of 55,793 men who had received replacement testosterone.3 The authors reported an increase in the relative risk of MI in the first 3 months after starting testosterone compared with the risk of MI in the same men in the prior year (relative risk [RR] = 1.36). However, the much more important absolute risk increase was very, very low, with only an additional 1.25 cases of MI seen over 1,000 patient-years. Apart from the fact that a RR of 1.36 is most unimpressive in a retrospective study, the simple fact that the men were older by a few months after TRT is probably more than adequate to explain this tiny increase in apparent risk.

The FDA has monitored these studies closely and has chosen not to make a determination that there is an increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with TRT. That is not at all the same as saying that it has been proven to be completely free of cardiovascular risk; rather it is a common-sense acknowledgment that there is not any convincing evidence to date of such a risk.

Thus, the conscientious clinician is left to conclude that TRT is a reasonable option in symptomatic patients who have been shown to have low levels of free testosterone. It has not been conclusively demonstrated that TRT will have significant beneficial effects, but neither has it been proven to have any true cardiovascular toxicity. It is a therapy worth trying in those symptomatic patients who understand that they will be receiving therapy of uncertain benefit, if any, and with the possibility of uncertain risk, if any.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, Connolly MJ, et al. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men; A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):639-650.

2. Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1829-1836.

3. Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PloS One. 2014;9(1):e85805 Epub.

1. Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, Connolly MJ, et al. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men; A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):639-650.

2. Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1829-1836.

3. Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PloS One. 2014;9(1):e85805 Epub.

Acting Surgeon General Confident in the Battle Against Tobacco, Ebola, and Preventable Diseases

Not many health care leaders can transition smoothly from discussing the importance of walking 30 minutes per day to the need to send PHS officers to help control the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. The Surgeon General has to. As the most prominent public health official, the Surgeon General must offer a reassuring voice on health care issues big and small. With over 26 years at the PHS, Rear Admiral (RADM) Boris D. Lushniak, MD, MPH, is well equipped to handle the challenging role.

A year after assuming the role and just before delivering a plenary address at the 2014 AMSUS meeting, RADM Lushniak agreed to a wide-ranging conversation with Federal Practitioner. The following is condensed and edited, but the complete interview can be found at http://www.fedprac.com.

The 50th anniversary of the Surgeon General’s report on smoking

RADM Boris D. Lushniak, Acting Surgeon General. Go back to January 1964 and realize what a different world we lived in back then. In fact, that report, which came out after a year and a half of scientific deliberations, of looking at facts, of searching through the literature, came up with a very important conclusion. That conclusion, simply put was: Smoking is bad for you.

Now it really was a landmark report from that perspective, but when we look back 50 years, what did it prove? It proved that cigarette smoking was directly associated with only 1 cancer at that point, specifically lung cancer in men. The report had a very simple but beautiful conclusion. It said that cigarette smoking is a health hazard of significant importance in the U.S. to warrant appropriate remedial action....

A half-century later, the social norms of our society have changed. We don’t have ashtrays all around. We don’t smoke on airplanes anymore. We oftentimes can’t smoke in bars and restaurants and establishments like that. We’ve moved from 43% of our population that smoked in 1964 to 18% currently.

We’ve had 32 Surgeons’ General reports since that first one....We brought up the issue of secondhand smoke 25 years ago. We talked about the successes and failures over these years, but 50 years later smoking remains a major public health problem in this country....

When we look to the future, what’s the goal? Well we really want to get to a zero point. We reannounced with the 50th anniversary report, which was released in January 2014, that this is an endgame strategy. At some point we have to realize that it’s not good enough to get down to 18% because of the health impact. Cigarettes and tobacco use in this country bring no good; no good to the individual, no good to the individual who has to deal with secondhand smoke, and no good for the future of our nation. So we’re really talking about an endgame strategy....

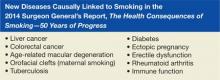

Our 50th anniversary report wasn’t just looking backward....It contains current data that now show us that we’re up to 13 different cancers caused by tobacco use. We know the impact on the whole human body. In essence, it affects almost every single system of the human body now. Brand-new diseases, formerly not associated with smoking, are still being discovered.

Most recently, we’ve seen diabetes and colon and rectal cancers as some of those diseases. We’re talking about blindness associated with smoking. We’re talking about diseases such as erectile dysfunction, which are associated with smoking. This product has brought nothing but grief and sorrow into our society and continues to do so.

Now it’s not only an impact on the United States for the Office of the Surgeon General’s to speak, but also in essence we know that internationally people look at the Surgeon General reports that come out of this office as that stellar scientific information that then can be translated worldwide.

Not only do we see leadership of public health here within the United States, but we also see leadership on an international level by profiling some of the major public health issues.

The PHS response to Ebola in the U.S. and Africa

RADM Lushniak. As many of the readers may know, the Surgeon General is the commander of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. We have 6,800 public health professionals. These are officers working in 11 different categories working across the government, to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of the nation.

[In October] I was in Anniston, Alabama, seeing about 70 of my officers being trained for deployment to Liberia. And in fact, in the next weeks, we will have a full team in Liberia who will be serving in the Monrovia Medical Unit and providing health care to both Liberian as well as foreign health care workers. I want to get that message out, because this battle against Ebola is occurring here in the U.S. and being done very well by the CDC and the NIH and elements of the Commissioned Corps who are working with the CDC.

At the same time, we know that the real success of eliminating Ebola and stopping the epidemic lies in Western Africa. Dr. Frieden has said that. We’re confident that there will not be an Ebola outbreak on U.S. soil; however, we need to be able to stop this outbreak. Therefore, I’m very proud of my officers who are heading off to Western Africa.

The role of the PHS Commissioned Corps

RADM Lushniak. Most of my officers are dedicated to who? To serving the underserved and vulnerable populations. Many of my clinical officers are assigned, for example, to the Indian Health Service and are providing care to that important population of our nation. They’re assigned to the Federal Bureau of Prisons and, therefore, working with the Department of Justice in getting health care to, again, a vulnerable and underserved population. They’re working at the NIH in a clinical perspective. They’re treating the Coast Guard as the main medical and dental and environment health officers. So I have officers scattered all around, and in essence, they see everything that any other practitioner sees in this country.

The emphasis certainly from the Office of the Surgeon General has been on prevention. It’s prevention of preventable diseases; many of them are chronic diseases. And certainly, my officers not only are out there treating those individual patients, but at the same time are implementing and taking to task on the importance of prevention as a general theme. We make sure that the word of the Surgeon General’s office gets spread to local communities through our practitioners.

Raising the Commissioned Corps profile

RADM Lushniak. We need to get the word out. Part of our issue, I’ll be honest with you, is that oftentimes people don’t even know the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps exists. Therefore, even when my officers are part of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention response, they’re embedded with other facets of CDC.

What I want to proudly say is that right now this Monrovia Medical Unit will be run by U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. This is the only entity of the U.S. government that will actually have direct patient care responsibilities in Western Africa. That being said, we’re also proud that this year is the 125th anniversary of the Commissioned Corps as a uniformed service in this country. So 125 years ago an act was passed by Congress to be able to establish this uniformed service.

Finally, I’d like to say that no other nation has a uniformed service like this. I keep saying that I love my sister services. I love the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Marines, the Coast Guard; but many other nations have similar type entities.

The reality of the situation is that no other nation on this planet has a uniformed service purely dedicated to public health. We are an unarmed service, and we are part of the Department of Health and Human Services, but we are just as proud to be officers. We are just as proud to be serving our nation in uniform on a slightly different mission but one that has, again, a noble cause associated with it.

Reaching the top of the PHS

RADM Lushniak. I’m honored and humbled to be in this position at this stage of my career. I came in 26, almost 27 years ago into the United States Public Health Service as a young lieutenant. My goal at that time was to be an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s how I started my career, doing what’s deemed to be shoe leather epidemiology, going out there and getting my hands dirty and being able to try to make this nation a better place and to protect the public’s health.

It’s been a great ride from the CDC to the FDA, and then ultimately, to the Office of the Secretary here within the Office of the Surgeon General as the Deputy and now as the Acting Surgeon General. The message is everyone should, first of all, acknowledge the fact that we have an incredible mission to undertake. The mission of the Commissioned Corps of the PHS is to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of our nation. And I dare say although we captured that as our mission, that mission is translatable to almost every federal practitioner that is out there.

The burden of that is apparent—to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of our nation. And yet it’s a bold and noble mission, one that is achievable. We’ve had incredible successes. We still have a lot of work ahead of us.

So first and foremost, I tell my young officers and I tell everyone who may be exposed to this conversation is the sense that do your job and do it well. That’s really the prime thing I’m asking my officers to do: Be dedicated to the mission and realize that incredible things are still achievable.

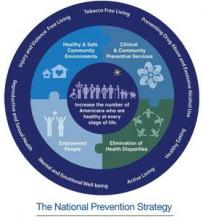

The National Prevention Strategy

The goal is for us to have a healthy population at every stage of life. And so 20 federal partners...came up with a National Prevention Strategy, which is a focus of priming our nation towards prevention and wellness. It’s based on 4 strategic aims, which includes the importance of healthy and safe communities. It also entails the idea of clinical community preventive services. It talks about the empowerment of people, which is a key component of change in this nation, and the elimination of health disparities throughout the nation. It focuses on the really important preventable diseases. And among them, include the elimination of tobacco use, the importance of our really looking at alcohol and substance use in general. It’s looking at the concept of active living, the importance that we move our bodies, and the importance of healthy eating.

Office of the Surgeon General initiatives

RADM Lushniak. First and foremost, the smoking issue still continues, and there will be more on tobacco use and smoking from us. We won’t give up that fight until we’re zeroed out.

In addition, recently we released a call to action on skin cancer prevention. That’s, I think, an important issue as well because we have over 5 million people in the United States each and every year who are treated for skin cancers. We have over 60,000 people who are diagnosed with the most deadly form of skin cancer, melanoma, and 9,000 people, that’s 1 person every hour, dying of melanoma. It has an incredible impact on our country, and it is, again, one of those preventable diseases. So we look at the idea of getting the message out that we, in the Office of Surgeon General, want people to live an active lifestyle. That’s an important part of the National Prevention Strategy.

I want people to be outdoors, I want them to be runners and walkers and enjoying nature; but at the same time, I need to get the message out that we need to be wary of ultraviolet radiation from sunlight, that we can protect ourselves, seek shade when possible, put on a big hat that produces shade on your face and neck and ears. Wear glasses, put on protective clothing, and then use sunscreens, broad-spectrum sunscreens of a UV protective factor of at least 15. That’s one of the initiatives that we recently released.

In the future, where we’re priming, we’re really getting back into the fitness mode. One of the things that we’re working on, and it really simplifies, I think, what has become too complex a message—the idea of how do we have a healthy and fit nation?...

I want people to start walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week. Do you realize just by that simple act of walking how good our nation could do in the future? How healthy we can be as a people. So we’re really looking at an emphasis on walking and walkable communities, because not every community is walkable at this stage.

Speaking at the AMSUS Continuing Education Meeting in Washington, D.C.

RADM Lushniak. AMSUS has always provided an excellent forum for the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, of which I am the commander, to be able to share our information with other federal practitioners, with other parties within the federal family that are interested in health care, in public health, in contact with patients on the clinical side and the scientific side....

I’ve been a member over many years, and I’ve been a regular attendee at the meetings. It allows us to cross-fertilize, to have that ability to sit down with our sister services, to be able to sit down with nonuniformed professionals who serve in the federal system under the flag of health care or under the flag of medical care or under the big flag of science, medical science.

Not many health care leaders can transition smoothly from discussing the importance of walking 30 minutes per day to the need to send PHS officers to help control the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. The Surgeon General has to. As the most prominent public health official, the Surgeon General must offer a reassuring voice on health care issues big and small. With over 26 years at the PHS, Rear Admiral (RADM) Boris D. Lushniak, MD, MPH, is well equipped to handle the challenging role.

A year after assuming the role and just before delivering a plenary address at the 2014 AMSUS meeting, RADM Lushniak agreed to a wide-ranging conversation with Federal Practitioner. The following is condensed and edited, but the complete interview can be found at http://www.fedprac.com.

The 50th anniversary of the Surgeon General’s report on smoking

RADM Boris D. Lushniak, Acting Surgeon General. Go back to January 1964 and realize what a different world we lived in back then. In fact, that report, which came out after a year and a half of scientific deliberations, of looking at facts, of searching through the literature, came up with a very important conclusion. That conclusion, simply put was: Smoking is bad for you.

Now it really was a landmark report from that perspective, but when we look back 50 years, what did it prove? It proved that cigarette smoking was directly associated with only 1 cancer at that point, specifically lung cancer in men. The report had a very simple but beautiful conclusion. It said that cigarette smoking is a health hazard of significant importance in the U.S. to warrant appropriate remedial action....

A half-century later, the social norms of our society have changed. We don’t have ashtrays all around. We don’t smoke on airplanes anymore. We oftentimes can’t smoke in bars and restaurants and establishments like that. We’ve moved from 43% of our population that smoked in 1964 to 18% currently.

We’ve had 32 Surgeons’ General reports since that first one....We brought up the issue of secondhand smoke 25 years ago. We talked about the successes and failures over these years, but 50 years later smoking remains a major public health problem in this country....

When we look to the future, what’s the goal? Well we really want to get to a zero point. We reannounced with the 50th anniversary report, which was released in January 2014, that this is an endgame strategy. At some point we have to realize that it’s not good enough to get down to 18% because of the health impact. Cigarettes and tobacco use in this country bring no good; no good to the individual, no good to the individual who has to deal with secondhand smoke, and no good for the future of our nation. So we’re really talking about an endgame strategy....

Our 50th anniversary report wasn’t just looking backward....It contains current data that now show us that we’re up to 13 different cancers caused by tobacco use. We know the impact on the whole human body. In essence, it affects almost every single system of the human body now. Brand-new diseases, formerly not associated with smoking, are still being discovered.

Most recently, we’ve seen diabetes and colon and rectal cancers as some of those diseases. We’re talking about blindness associated with smoking. We’re talking about diseases such as erectile dysfunction, which are associated with smoking. This product has brought nothing but grief and sorrow into our society and continues to do so.

Now it’s not only an impact on the United States for the Office of the Surgeon General’s to speak, but also in essence we know that internationally people look at the Surgeon General reports that come out of this office as that stellar scientific information that then can be translated worldwide.

Not only do we see leadership of public health here within the United States, but we also see leadership on an international level by profiling some of the major public health issues.

The PHS response to Ebola in the U.S. and Africa

RADM Lushniak. As many of the readers may know, the Surgeon General is the commander of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. We have 6,800 public health professionals. These are officers working in 11 different categories working across the government, to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of the nation.

[In October] I was in Anniston, Alabama, seeing about 70 of my officers being trained for deployment to Liberia. And in fact, in the next weeks, we will have a full team in Liberia who will be serving in the Monrovia Medical Unit and providing health care to both Liberian as well as foreign health care workers. I want to get that message out, because this battle against Ebola is occurring here in the U.S. and being done very well by the CDC and the NIH and elements of the Commissioned Corps who are working with the CDC.

At the same time, we know that the real success of eliminating Ebola and stopping the epidemic lies in Western Africa. Dr. Frieden has said that. We’re confident that there will not be an Ebola outbreak on U.S. soil; however, we need to be able to stop this outbreak. Therefore, I’m very proud of my officers who are heading off to Western Africa.

The role of the PHS Commissioned Corps

RADM Lushniak. Most of my officers are dedicated to who? To serving the underserved and vulnerable populations. Many of my clinical officers are assigned, for example, to the Indian Health Service and are providing care to that important population of our nation. They’re assigned to the Federal Bureau of Prisons and, therefore, working with the Department of Justice in getting health care to, again, a vulnerable and underserved population. They’re working at the NIH in a clinical perspective. They’re treating the Coast Guard as the main medical and dental and environment health officers. So I have officers scattered all around, and in essence, they see everything that any other practitioner sees in this country.

The emphasis certainly from the Office of the Surgeon General has been on prevention. It’s prevention of preventable diseases; many of them are chronic diseases. And certainly, my officers not only are out there treating those individual patients, but at the same time are implementing and taking to task on the importance of prevention as a general theme. We make sure that the word of the Surgeon General’s office gets spread to local communities through our practitioners.

Raising the Commissioned Corps profile

RADM Lushniak. We need to get the word out. Part of our issue, I’ll be honest with you, is that oftentimes people don’t even know the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps exists. Therefore, even when my officers are part of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention response, they’re embedded with other facets of CDC.

What I want to proudly say is that right now this Monrovia Medical Unit will be run by U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. This is the only entity of the U.S. government that will actually have direct patient care responsibilities in Western Africa. That being said, we’re also proud that this year is the 125th anniversary of the Commissioned Corps as a uniformed service in this country. So 125 years ago an act was passed by Congress to be able to establish this uniformed service.

Finally, I’d like to say that no other nation has a uniformed service like this. I keep saying that I love my sister services. I love the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Marines, the Coast Guard; but many other nations have similar type entities.

The reality of the situation is that no other nation on this planet has a uniformed service purely dedicated to public health. We are an unarmed service, and we are part of the Department of Health and Human Services, but we are just as proud to be officers. We are just as proud to be serving our nation in uniform on a slightly different mission but one that has, again, a noble cause associated with it.

Reaching the top of the PHS

RADM Lushniak. I’m honored and humbled to be in this position at this stage of my career. I came in 26, almost 27 years ago into the United States Public Health Service as a young lieutenant. My goal at that time was to be an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s how I started my career, doing what’s deemed to be shoe leather epidemiology, going out there and getting my hands dirty and being able to try to make this nation a better place and to protect the public’s health.

It’s been a great ride from the CDC to the FDA, and then ultimately, to the Office of the Secretary here within the Office of the Surgeon General as the Deputy and now as the Acting Surgeon General. The message is everyone should, first of all, acknowledge the fact that we have an incredible mission to undertake. The mission of the Commissioned Corps of the PHS is to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of our nation. And I dare say although we captured that as our mission, that mission is translatable to almost every federal practitioner that is out there.

The burden of that is apparent—to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of our nation. And yet it’s a bold and noble mission, one that is achievable. We’ve had incredible successes. We still have a lot of work ahead of us.

So first and foremost, I tell my young officers and I tell everyone who may be exposed to this conversation is the sense that do your job and do it well. That’s really the prime thing I’m asking my officers to do: Be dedicated to the mission and realize that incredible things are still achievable.

The National Prevention Strategy

The goal is for us to have a healthy population at every stage of life. And so 20 federal partners...came up with a National Prevention Strategy, which is a focus of priming our nation towards prevention and wellness. It’s based on 4 strategic aims, which includes the importance of healthy and safe communities. It also entails the idea of clinical community preventive services. It talks about the empowerment of people, which is a key component of change in this nation, and the elimination of health disparities throughout the nation. It focuses on the really important preventable diseases. And among them, include the elimination of tobacco use, the importance of our really looking at alcohol and substance use in general. It’s looking at the concept of active living, the importance that we move our bodies, and the importance of healthy eating.

Office of the Surgeon General initiatives

RADM Lushniak. First and foremost, the smoking issue still continues, and there will be more on tobacco use and smoking from us. We won’t give up that fight until we’re zeroed out.

In addition, recently we released a call to action on skin cancer prevention. That’s, I think, an important issue as well because we have over 5 million people in the United States each and every year who are treated for skin cancers. We have over 60,000 people who are diagnosed with the most deadly form of skin cancer, melanoma, and 9,000 people, that’s 1 person every hour, dying of melanoma. It has an incredible impact on our country, and it is, again, one of those preventable diseases. So we look at the idea of getting the message out that we, in the Office of Surgeon General, want people to live an active lifestyle. That’s an important part of the National Prevention Strategy.

I want people to be outdoors, I want them to be runners and walkers and enjoying nature; but at the same time, I need to get the message out that we need to be wary of ultraviolet radiation from sunlight, that we can protect ourselves, seek shade when possible, put on a big hat that produces shade on your face and neck and ears. Wear glasses, put on protective clothing, and then use sunscreens, broad-spectrum sunscreens of a UV protective factor of at least 15. That’s one of the initiatives that we recently released.

In the future, where we’re priming, we’re really getting back into the fitness mode. One of the things that we’re working on, and it really simplifies, I think, what has become too complex a message—the idea of how do we have a healthy and fit nation?...

I want people to start walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week. Do you realize just by that simple act of walking how good our nation could do in the future? How healthy we can be as a people. So we’re really looking at an emphasis on walking and walkable communities, because not every community is walkable at this stage.

Speaking at the AMSUS Continuing Education Meeting in Washington, D.C.

RADM Lushniak. AMSUS has always provided an excellent forum for the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, of which I am the commander, to be able to share our information with other federal practitioners, with other parties within the federal family that are interested in health care, in public health, in contact with patients on the clinical side and the scientific side....

I’ve been a member over many years, and I’ve been a regular attendee at the meetings. It allows us to cross-fertilize, to have that ability to sit down with our sister services, to be able to sit down with nonuniformed professionals who serve in the federal system under the flag of health care or under the flag of medical care or under the big flag of science, medical science.

Not many health care leaders can transition smoothly from discussing the importance of walking 30 minutes per day to the need to send PHS officers to help control the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. The Surgeon General has to. As the most prominent public health official, the Surgeon General must offer a reassuring voice on health care issues big and small. With over 26 years at the PHS, Rear Admiral (RADM) Boris D. Lushniak, MD, MPH, is well equipped to handle the challenging role.

A year after assuming the role and just before delivering a plenary address at the 2014 AMSUS meeting, RADM Lushniak agreed to a wide-ranging conversation with Federal Practitioner. The following is condensed and edited, but the complete interview can be found at http://www.fedprac.com.

The 50th anniversary of the Surgeon General’s report on smoking

RADM Boris D. Lushniak, Acting Surgeon General. Go back to January 1964 and realize what a different world we lived in back then. In fact, that report, which came out after a year and a half of scientific deliberations, of looking at facts, of searching through the literature, came up with a very important conclusion. That conclusion, simply put was: Smoking is bad for you.

Now it really was a landmark report from that perspective, but when we look back 50 years, what did it prove? It proved that cigarette smoking was directly associated with only 1 cancer at that point, specifically lung cancer in men. The report had a very simple but beautiful conclusion. It said that cigarette smoking is a health hazard of significant importance in the U.S. to warrant appropriate remedial action....

A half-century later, the social norms of our society have changed. We don’t have ashtrays all around. We don’t smoke on airplanes anymore. We oftentimes can’t smoke in bars and restaurants and establishments like that. We’ve moved from 43% of our population that smoked in 1964 to 18% currently.

We’ve had 32 Surgeons’ General reports since that first one....We brought up the issue of secondhand smoke 25 years ago. We talked about the successes and failures over these years, but 50 years later smoking remains a major public health problem in this country....

When we look to the future, what’s the goal? Well we really want to get to a zero point. We reannounced with the 50th anniversary report, which was released in January 2014, that this is an endgame strategy. At some point we have to realize that it’s not good enough to get down to 18% because of the health impact. Cigarettes and tobacco use in this country bring no good; no good to the individual, no good to the individual who has to deal with secondhand smoke, and no good for the future of our nation. So we’re really talking about an endgame strategy....

Our 50th anniversary report wasn’t just looking backward....It contains current data that now show us that we’re up to 13 different cancers caused by tobacco use. We know the impact on the whole human body. In essence, it affects almost every single system of the human body now. Brand-new diseases, formerly not associated with smoking, are still being discovered.

Most recently, we’ve seen diabetes and colon and rectal cancers as some of those diseases. We’re talking about blindness associated with smoking. We’re talking about diseases such as erectile dysfunction, which are associated with smoking. This product has brought nothing but grief and sorrow into our society and continues to do so.

Now it’s not only an impact on the United States for the Office of the Surgeon General’s to speak, but also in essence we know that internationally people look at the Surgeon General reports that come out of this office as that stellar scientific information that then can be translated worldwide.

Not only do we see leadership of public health here within the United States, but we also see leadership on an international level by profiling some of the major public health issues.

The PHS response to Ebola in the U.S. and Africa

RADM Lushniak. As many of the readers may know, the Surgeon General is the commander of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. We have 6,800 public health professionals. These are officers working in 11 different categories working across the government, to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of the nation.

[In October] I was in Anniston, Alabama, seeing about 70 of my officers being trained for deployment to Liberia. And in fact, in the next weeks, we will have a full team in Liberia who will be serving in the Monrovia Medical Unit and providing health care to both Liberian as well as foreign health care workers. I want to get that message out, because this battle against Ebola is occurring here in the U.S. and being done very well by the CDC and the NIH and elements of the Commissioned Corps who are working with the CDC.

At the same time, we know that the real success of eliminating Ebola and stopping the epidemic lies in Western Africa. Dr. Frieden has said that. We’re confident that there will not be an Ebola outbreak on U.S. soil; however, we need to be able to stop this outbreak. Therefore, I’m very proud of my officers who are heading off to Western Africa.

The role of the PHS Commissioned Corps

RADM Lushniak. Most of my officers are dedicated to who? To serving the underserved and vulnerable populations. Many of my clinical officers are assigned, for example, to the Indian Health Service and are providing care to that important population of our nation. They’re assigned to the Federal Bureau of Prisons and, therefore, working with the Department of Justice in getting health care to, again, a vulnerable and underserved population. They’re working at the NIH in a clinical perspective. They’re treating the Coast Guard as the main medical and dental and environment health officers. So I have officers scattered all around, and in essence, they see everything that any other practitioner sees in this country.

The emphasis certainly from the Office of the Surgeon General has been on prevention. It’s prevention of preventable diseases; many of them are chronic diseases. And certainly, my officers not only are out there treating those individual patients, but at the same time are implementing and taking to task on the importance of prevention as a general theme. We make sure that the word of the Surgeon General’s office gets spread to local communities through our practitioners.

Raising the Commissioned Corps profile

RADM Lushniak. We need to get the word out. Part of our issue, I’ll be honest with you, is that oftentimes people don’t even know the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps exists. Therefore, even when my officers are part of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention response, they’re embedded with other facets of CDC.

What I want to proudly say is that right now this Monrovia Medical Unit will be run by U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. This is the only entity of the U.S. government that will actually have direct patient care responsibilities in Western Africa. That being said, we’re also proud that this year is the 125th anniversary of the Commissioned Corps as a uniformed service in this country. So 125 years ago an act was passed by Congress to be able to establish this uniformed service.

Finally, I’d like to say that no other nation has a uniformed service like this. I keep saying that I love my sister services. I love the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Marines, the Coast Guard; but many other nations have similar type entities.

The reality of the situation is that no other nation on this planet has a uniformed service purely dedicated to public health. We are an unarmed service, and we are part of the Department of Health and Human Services, but we are just as proud to be officers. We are just as proud to be serving our nation in uniform on a slightly different mission but one that has, again, a noble cause associated with it.

Reaching the top of the PHS

RADM Lushniak. I’m honored and humbled to be in this position at this stage of my career. I came in 26, almost 27 years ago into the United States Public Health Service as a young lieutenant. My goal at that time was to be an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s how I started my career, doing what’s deemed to be shoe leather epidemiology, going out there and getting my hands dirty and being able to try to make this nation a better place and to protect the public’s health.

It’s been a great ride from the CDC to the FDA, and then ultimately, to the Office of the Secretary here within the Office of the Surgeon General as the Deputy and now as the Acting Surgeon General. The message is everyone should, first of all, acknowledge the fact that we have an incredible mission to undertake. The mission of the Commissioned Corps of the PHS is to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of our nation. And I dare say although we captured that as our mission, that mission is translatable to almost every federal practitioner that is out there.

The burden of that is apparent—to protect, promote, and advance the health and safety of our nation. And yet it’s a bold and noble mission, one that is achievable. We’ve had incredible successes. We still have a lot of work ahead of us.

So first and foremost, I tell my young officers and I tell everyone who may be exposed to this conversation is the sense that do your job and do it well. That’s really the prime thing I’m asking my officers to do: Be dedicated to the mission and realize that incredible things are still achievable.

The National Prevention Strategy

The goal is for us to have a healthy population at every stage of life. And so 20 federal partners...came up with a National Prevention Strategy, which is a focus of priming our nation towards prevention and wellness. It’s based on 4 strategic aims, which includes the importance of healthy and safe communities. It also entails the idea of clinical community preventive services. It talks about the empowerment of people, which is a key component of change in this nation, and the elimination of health disparities throughout the nation. It focuses on the really important preventable diseases. And among them, include the elimination of tobacco use, the importance of our really looking at alcohol and substance use in general. It’s looking at the concept of active living, the importance that we move our bodies, and the importance of healthy eating.

Office of the Surgeon General initiatives

RADM Lushniak. First and foremost, the smoking issue still continues, and there will be more on tobacco use and smoking from us. We won’t give up that fight until we’re zeroed out.

In addition, recently we released a call to action on skin cancer prevention. That’s, I think, an important issue as well because we have over 5 million people in the United States each and every year who are treated for skin cancers. We have over 60,000 people who are diagnosed with the most deadly form of skin cancer, melanoma, and 9,000 people, that’s 1 person every hour, dying of melanoma. It has an incredible impact on our country, and it is, again, one of those preventable diseases. So we look at the idea of getting the message out that we, in the Office of Surgeon General, want people to live an active lifestyle. That’s an important part of the National Prevention Strategy.

I want people to be outdoors, I want them to be runners and walkers and enjoying nature; but at the same time, I need to get the message out that we need to be wary of ultraviolet radiation from sunlight, that we can protect ourselves, seek shade when possible, put on a big hat that produces shade on your face and neck and ears. Wear glasses, put on protective clothing, and then use sunscreens, broad-spectrum sunscreens of a UV protective factor of at least 15. That’s one of the initiatives that we recently released.

In the future, where we’re priming, we’re really getting back into the fitness mode. One of the things that we’re working on, and it really simplifies, I think, what has become too complex a message—the idea of how do we have a healthy and fit nation?...

I want people to start walking 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week. Do you realize just by that simple act of walking how good our nation could do in the future? How healthy we can be as a people. So we’re really looking at an emphasis on walking and walkable communities, because not every community is walkable at this stage.

Speaking at the AMSUS Continuing Education Meeting in Washington, D.C.

RADM Lushniak. AMSUS has always provided an excellent forum for the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, of which I am the commander, to be able to share our information with other federal practitioners, with other parties within the federal family that are interested in health care, in public health, in contact with patients on the clinical side and the scientific side....

I’ve been a member over many years, and I’ve been a regular attendee at the meetings. It allows us to cross-fertilize, to have that ability to sit down with our sister services, to be able to sit down with nonuniformed professionals who serve in the federal system under the flag of health care or under the flag of medical care or under the big flag of science, medical science.

The 'Spidey Sense' of doctors

Of all the things you learn in training, one of the most nebulous, but useful, is “Spidey Sense.”

In comics, Spider-Man had a power called Spidey Sense, which caused a skull-base tingling when danger was present. It was a prescient, clairvoyant ability that allowed him to take action to protect himself.

Somewhere along the line, most doctors I know get a similar ability, but it warns us when something is seriously wrong with a patient. Often, it fires before you even have a rational reason to be worried, and it’s almost never wrong.

As a senior in medical school, I heard a conversation between a resident and an attending. The resident was talking about how she’d seen a patient in the emergency department who she sent to the ICU without a concrete reason. An hour after arriving, the patient suffered a cardiac arrest and was successfully resuscitated. The attending told her that this was one of the most critical skills to develop: knowing when patients are really sick, even before you have any obvious reason to think they are.

I have no idea when I learned it. At some point it was just there. I assume it’s a result of years of medical training making you subconsciously recognize a bad situation. It doesn’t fire very often, but when it does it can’t be ignored. Sometimes even a few words typed on my schedule will set it off.

My staff knows when it’s hit me because I’ll bring an MRI order up to the front desk before I’ve completed the appointment and tell them to start working on it.

Not every sick patient sets it off. In fact, obviously sick people never do. In those cases, it’s not needed. But when the tingling starts when you first start talking to someone … don’t ignore it.

There are a lot of intangibles in medicine, and this is one of them. I can’t explain it, but it’s one of the most important skills I’ve learned, although I have no idea when I did. I’m just glad it’s there.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Of all the things you learn in training, one of the most nebulous, but useful, is “Spidey Sense.”

In comics, Spider-Man had a power called Spidey Sense, which caused a skull-base tingling when danger was present. It was a prescient, clairvoyant ability that allowed him to take action to protect himself.

Somewhere along the line, most doctors I know get a similar ability, but it warns us when something is seriously wrong with a patient. Often, it fires before you even have a rational reason to be worried, and it’s almost never wrong.

As a senior in medical school, I heard a conversation between a resident and an attending. The resident was talking about how she’d seen a patient in the emergency department who she sent to the ICU without a concrete reason. An hour after arriving, the patient suffered a cardiac arrest and was successfully resuscitated. The attending told her that this was one of the most critical skills to develop: knowing when patients are really sick, even before you have any obvious reason to think they are.

I have no idea when I learned it. At some point it was just there. I assume it’s a result of years of medical training making you subconsciously recognize a bad situation. It doesn’t fire very often, but when it does it can’t be ignored. Sometimes even a few words typed on my schedule will set it off.

My staff knows when it’s hit me because I’ll bring an MRI order up to the front desk before I’ve completed the appointment and tell them to start working on it.

Not every sick patient sets it off. In fact, obviously sick people never do. In those cases, it’s not needed. But when the tingling starts when you first start talking to someone … don’t ignore it.

There are a lot of intangibles in medicine, and this is one of them. I can’t explain it, but it’s one of the most important skills I’ve learned, although I have no idea when I did. I’m just glad it’s there.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Of all the things you learn in training, one of the most nebulous, but useful, is “Spidey Sense.”

In comics, Spider-Man had a power called Spidey Sense, which caused a skull-base tingling when danger was present. It was a prescient, clairvoyant ability that allowed him to take action to protect himself.

Somewhere along the line, most doctors I know get a similar ability, but it warns us when something is seriously wrong with a patient. Often, it fires before you even have a rational reason to be worried, and it’s almost never wrong.

As a senior in medical school, I heard a conversation between a resident and an attending. The resident was talking about how she’d seen a patient in the emergency department who she sent to the ICU without a concrete reason. An hour after arriving, the patient suffered a cardiac arrest and was successfully resuscitated. The attending told her that this was one of the most critical skills to develop: knowing when patients are really sick, even before you have any obvious reason to think they are.

I have no idea when I learned it. At some point it was just there. I assume it’s a result of years of medical training making you subconsciously recognize a bad situation. It doesn’t fire very often, but when it does it can’t be ignored. Sometimes even a few words typed on my schedule will set it off.

My staff knows when it’s hit me because I’ll bring an MRI order up to the front desk before I’ve completed the appointment and tell them to start working on it.

Not every sick patient sets it off. In fact, obviously sick people never do. In those cases, it’s not needed. But when the tingling starts when you first start talking to someone … don’t ignore it.

There are a lot of intangibles in medicine, and this is one of them. I can’t explain it, but it’s one of the most important skills I’ve learned, although I have no idea when I did. I’m just glad it’s there.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Laser treatments for men

In our final segment on male dermatology, we will be focusing on laser treatments in men. There has been a steady increase in cosmetic procedures in men over the last decade, and laser procedures tend to be some of the most popular. In general, laser treatments provide faster results than topical or oral treatments and offer subtle aesthetic improvements with little to no downtime depending on the procedure. These factors appeal to male patients, who generally are generally less risk tolerant than women, and want masculinizing treatments with little downtime and natural results.

• Hair growth. Men tend to have highly pigmented, thicker hair in contrast to women, and often seek laser hair removal for excess body hair. Common sites include the back, upper arms, posterior hairline, lower beardline, and chest. Similar precautions apply to both men and women, such as proper cooling of the skin and avoidance of tanned skin. However, laser settings for male patients may need to be adjusted given the thicker, darkly pigmented hairs and often lower pain threshold. In addition, proper counseling of men is necessary with laser hair removal, because men often need more treatments than women and may need a topical anesthetic for highly sensitive areas.

• Body contouring. Men tend to deposit fat in hard-to-lose areas, such as the central abdomen and flanks. The expanding array of noninvasive devices using cold temperatures to freeze the fat, or ultrasound and radiofrequency devices to heat and thereby tighten the subcutaneous tissue have made body contouring one of the fastest growing cosmetic markets for men. Men are great candidates for these procedures given the fast results, minor discomfort, and noninvasive nature. Although many men have visceral abdominal fat that does not respond to these treatments, areas often treated with great long-term results include the upper and lower abdomen, flanks, arms, chest, and back.

• Rosacea. Men have a higher density of facial blood vessels than women, and they often seek treatment for telangiectasias and overall facial erythema. For noninflammatory erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, vascular laser treatments are the most effective treatments. Pulsed dye laser is often the best laser to target both large and small facial blood vessels and flushing erythema. Intense pulsed light (IPL) lasers are often a more popular choice for men because they involve less downtime and can treat brown spots as well. However, IPL must be used with caution in skin of color and tanned skin because of the risks of scarring and hyperpigmentation. Men may need more treatments and higher energy settings than women. Men also prefer minimal downtime and thus more frequent nonpurpuric settings are often preferred with any vascular laser. In addition, with IPL, men should be warned of the possibility of the laser temporarily stunting hair growth or causing hair to grow in patchy temporarily when using the device in the beard or mustache area.