User login

Odds Are

I’ve always wondered what kind of irresponsible, misguided parent brings children to Las Vegas. Now I have the answer, right in the mirror. Don’t judge: My sister lives there, so if the kids are ever going to see their cousins, they have to share the road with trucks that say, “Girls! Girls! Girls!” (We told the 9-year-old that these were advertisements for clothing, which the women pictured seemed to need.)

It’s true that Las Vegas has become more family friendly...for the Kardashians. We did, however, manage to make the trip educational. In psychology, the kids found that after 10:00 p.m., everyone’s tempers are shorter than a 9-year-old boy lost in a crowd. In chemistry, they discovered that no substance yet synthesized can mask the smell of cigarette smoke. And in meteorology, they learned never to step in a puddle on The Strip; whatever it is, it’s not rain.

Hope falls

Is there anything we wouldn’t do to prevent someone from dying of cancer? We will ride bikes 150 miles, run marathons, and wear endless seas of pink, even though honestly it’s not everyone’s color (you know who you are). So if there were, say, a safe and effective means of preventing up to 4,000 cancer deaths a year, certainly doctors would be first in line to make sure everyone is protected, right?

Sure...between half and two-thirds of the time, according to a new analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s how often providers recommend human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to their eligible female and male patients. Maybe cervical, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers need to get together and claim a color that looks good on everyone: Is cerulean taken?

I know we all get frustrated with vaccine deniers, but why aren’t we at least recommending HPV vaccine to 100% of our patients? Is it because they won’t be our patients by the time they get cancer? Is it because the vaccine is more expensive and more painful than some (both true, but again, y’all, cancer)? Is it because it’s awkward to talk to parents about how their cherubic 11-year-old is one day going to grow up into an adult who is likely to have, you know, S-E-X?

Whatever the reason, I share Assistant Surgeon General Dr. Anne Schuchat’s disappointment that only 37.6% of eligible girls and 13.6% of eligible boys got vaccinated against HPV last year. When poor parental uptake is the problem, we need to work on education. But when we as providers are not even recommending the vaccine, you can color me embarrassed.

Yellow-bellied?

Parents look at me like I’m crazy all the time, which I resent, because I’m only crazy most of the time. For the first 3 months of their baby's life, I tell parents to call me at the first sign of a fever; then I tell them fever is a nothing to worry about. I say that sleeping face-down can be deadly until their baby learns to roll back-to-front; then I tell them not to worry. And for the first 7 days of life, I tell them that newborn jaundice can cause severe brain damage, until I start saying it’s normal, especially in breastfed infants. I flip-flop more than a candidate for Congress.

A new study may reassure some mothers of nursing infants who look a little orange (the infants, that is; orange mothers should still be concerned). We’ve always known that breastfed infants tend to keep high levels of indirect bilirubin in their bloodstreams long after the first week in life, but no one yet had bothered to establish the typical range and time course. Dr. M. Jeffrey Maisels and a team from Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine changed all that with the use of transcutaneous bilirubin (TCB) monitors and 1,044 predominately breastfeeding infants.

Not only did they determine that at age 3-4 weeks between 34% and 43% of these infants still had TCB measurements over 5 mg/dL, they also reaffirmed that we doctors are really bad at guessing bilirubin levels from looking at babies. They asked trained clinicians to guess the “jaundice zone scores” of the infants, which sound like a customer loyalty program at a sporting goods store but are really just an estimate of how far down the infant’s body it looks yellow. The scores were so far off that a baby with a score of 0 could have a bilirubin level as high as 12.8 mg/dL. I can only hope that with his expertise in ferreting out bad human judgment, Dr. Maisels’s next study will investigate candidates for Congress.

Inattention

A complex society cannot function without some degree of trust; there’s all sorts of scary stuff I’d like to know, and I’m happy to pay a few dollars in taxes to make sure someone more qualified than I am is checking. Does this bridge I’m crossing have severe erosion? Is there another plane in our airspace? What was my 14-year-old daughter texting to her “boyfriend” last night? (Thanks, National Security Agency!)

Drug safety is one of those things, especially when many of my patients and one of my own children are taking said drug. A new study from researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital suggests that perhaps when it comes to the long-term safety of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not looked as hard as it might. Paging Dr. Edward Snowden!

One might assume that since up to 10% of U.S. children now carry a diagnosis of ADHD, and since those children start medications as young as age 4 and continue to use them for many years, the safety studies that got these drugs approved would have been especially rigorous. Yeah, no. Only 5 of 32 preapproval trials focused on safety, these trials enrolled an average of 75 patients (as opposed to the recommended 1,500), and few lasted as long as 12 months, with approval sometimes granted after only 8 weeks of study and some older drugs being “grandfathered” in with essentially no safety data whatsoever.

I see one bright spot in this desert of data. Whenever I prescribe a stimulant for ADHD, I’ll understand that I’m taking a gamble, and I’ll fondly remember our family trip to Las Vegas.

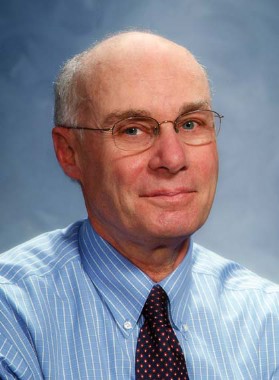

David L. Hill, M.D., FAAP, is the author of Dad to Dad: Parenting Like a Pro (AAP Publishing, 2012). He is also vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He serves as Program Director for the AAP Council on Communications and Media and as an executive committee member of the North Carolina Pediatric Society. He has recorded commentaries for NPR's All Things Considered and provided content for various print, television, and Internet outlets.

I’ve always wondered what kind of irresponsible, misguided parent brings children to Las Vegas. Now I have the answer, right in the mirror. Don’t judge: My sister lives there, so if the kids are ever going to see their cousins, they have to share the road with trucks that say, “Girls! Girls! Girls!” (We told the 9-year-old that these were advertisements for clothing, which the women pictured seemed to need.)

It’s true that Las Vegas has become more family friendly...for the Kardashians. We did, however, manage to make the trip educational. In psychology, the kids found that after 10:00 p.m., everyone’s tempers are shorter than a 9-year-old boy lost in a crowd. In chemistry, they discovered that no substance yet synthesized can mask the smell of cigarette smoke. And in meteorology, they learned never to step in a puddle on The Strip; whatever it is, it’s not rain.

Hope falls

Is there anything we wouldn’t do to prevent someone from dying of cancer? We will ride bikes 150 miles, run marathons, and wear endless seas of pink, even though honestly it’s not everyone’s color (you know who you are). So if there were, say, a safe and effective means of preventing up to 4,000 cancer deaths a year, certainly doctors would be first in line to make sure everyone is protected, right?

Sure...between half and two-thirds of the time, according to a new analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s how often providers recommend human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to their eligible female and male patients. Maybe cervical, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers need to get together and claim a color that looks good on everyone: Is cerulean taken?

I know we all get frustrated with vaccine deniers, but why aren’t we at least recommending HPV vaccine to 100% of our patients? Is it because they won’t be our patients by the time they get cancer? Is it because the vaccine is more expensive and more painful than some (both true, but again, y’all, cancer)? Is it because it’s awkward to talk to parents about how their cherubic 11-year-old is one day going to grow up into an adult who is likely to have, you know, S-E-X?

Whatever the reason, I share Assistant Surgeon General Dr. Anne Schuchat’s disappointment that only 37.6% of eligible girls and 13.6% of eligible boys got vaccinated against HPV last year. When poor parental uptake is the problem, we need to work on education. But when we as providers are not even recommending the vaccine, you can color me embarrassed.

Yellow-bellied?

Parents look at me like I’m crazy all the time, which I resent, because I’m only crazy most of the time. For the first 3 months of their baby's life, I tell parents to call me at the first sign of a fever; then I tell them fever is a nothing to worry about. I say that sleeping face-down can be deadly until their baby learns to roll back-to-front; then I tell them not to worry. And for the first 7 days of life, I tell them that newborn jaundice can cause severe brain damage, until I start saying it’s normal, especially in breastfed infants. I flip-flop more than a candidate for Congress.

A new study may reassure some mothers of nursing infants who look a little orange (the infants, that is; orange mothers should still be concerned). We’ve always known that breastfed infants tend to keep high levels of indirect bilirubin in their bloodstreams long after the first week in life, but no one yet had bothered to establish the typical range and time course. Dr. M. Jeffrey Maisels and a team from Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine changed all that with the use of transcutaneous bilirubin (TCB) monitors and 1,044 predominately breastfeeding infants.

Not only did they determine that at age 3-4 weeks between 34% and 43% of these infants still had TCB measurements over 5 mg/dL, they also reaffirmed that we doctors are really bad at guessing bilirubin levels from looking at babies. They asked trained clinicians to guess the “jaundice zone scores” of the infants, which sound like a customer loyalty program at a sporting goods store but are really just an estimate of how far down the infant’s body it looks yellow. The scores were so far off that a baby with a score of 0 could have a bilirubin level as high as 12.8 mg/dL. I can only hope that with his expertise in ferreting out bad human judgment, Dr. Maisels’s next study will investigate candidates for Congress.

Inattention

A complex society cannot function without some degree of trust; there’s all sorts of scary stuff I’d like to know, and I’m happy to pay a few dollars in taxes to make sure someone more qualified than I am is checking. Does this bridge I’m crossing have severe erosion? Is there another plane in our airspace? What was my 14-year-old daughter texting to her “boyfriend” last night? (Thanks, National Security Agency!)

Drug safety is one of those things, especially when many of my patients and one of my own children are taking said drug. A new study from researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital suggests that perhaps when it comes to the long-term safety of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not looked as hard as it might. Paging Dr. Edward Snowden!

One might assume that since up to 10% of U.S. children now carry a diagnosis of ADHD, and since those children start medications as young as age 4 and continue to use them for many years, the safety studies that got these drugs approved would have been especially rigorous. Yeah, no. Only 5 of 32 preapproval trials focused on safety, these trials enrolled an average of 75 patients (as opposed to the recommended 1,500), and few lasted as long as 12 months, with approval sometimes granted after only 8 weeks of study and some older drugs being “grandfathered” in with essentially no safety data whatsoever.

I see one bright spot in this desert of data. Whenever I prescribe a stimulant for ADHD, I’ll understand that I’m taking a gamble, and I’ll fondly remember our family trip to Las Vegas.

David L. Hill, M.D., FAAP, is the author of Dad to Dad: Parenting Like a Pro (AAP Publishing, 2012). He is also vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He serves as Program Director for the AAP Council on Communications and Media and as an executive committee member of the North Carolina Pediatric Society. He has recorded commentaries for NPR's All Things Considered and provided content for various print, television, and Internet outlets.

I’ve always wondered what kind of irresponsible, misguided parent brings children to Las Vegas. Now I have the answer, right in the mirror. Don’t judge: My sister lives there, so if the kids are ever going to see their cousins, they have to share the road with trucks that say, “Girls! Girls! Girls!” (We told the 9-year-old that these were advertisements for clothing, which the women pictured seemed to need.)

It’s true that Las Vegas has become more family friendly...for the Kardashians. We did, however, manage to make the trip educational. In psychology, the kids found that after 10:00 p.m., everyone’s tempers are shorter than a 9-year-old boy lost in a crowd. In chemistry, they discovered that no substance yet synthesized can mask the smell of cigarette smoke. And in meteorology, they learned never to step in a puddle on The Strip; whatever it is, it’s not rain.

Hope falls

Is there anything we wouldn’t do to prevent someone from dying of cancer? We will ride bikes 150 miles, run marathons, and wear endless seas of pink, even though honestly it’s not everyone’s color (you know who you are). So if there were, say, a safe and effective means of preventing up to 4,000 cancer deaths a year, certainly doctors would be first in line to make sure everyone is protected, right?

Sure...between half and two-thirds of the time, according to a new analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s how often providers recommend human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to their eligible female and male patients. Maybe cervical, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers need to get together and claim a color that looks good on everyone: Is cerulean taken?

I know we all get frustrated with vaccine deniers, but why aren’t we at least recommending HPV vaccine to 100% of our patients? Is it because they won’t be our patients by the time they get cancer? Is it because the vaccine is more expensive and more painful than some (both true, but again, y’all, cancer)? Is it because it’s awkward to talk to parents about how their cherubic 11-year-old is one day going to grow up into an adult who is likely to have, you know, S-E-X?

Whatever the reason, I share Assistant Surgeon General Dr. Anne Schuchat’s disappointment that only 37.6% of eligible girls and 13.6% of eligible boys got vaccinated against HPV last year. When poor parental uptake is the problem, we need to work on education. But when we as providers are not even recommending the vaccine, you can color me embarrassed.

Yellow-bellied?

Parents look at me like I’m crazy all the time, which I resent, because I’m only crazy most of the time. For the first 3 months of their baby's life, I tell parents to call me at the first sign of a fever; then I tell them fever is a nothing to worry about. I say that sleeping face-down can be deadly until their baby learns to roll back-to-front; then I tell them not to worry. And for the first 7 days of life, I tell them that newborn jaundice can cause severe brain damage, until I start saying it’s normal, especially in breastfed infants. I flip-flop more than a candidate for Congress.

A new study may reassure some mothers of nursing infants who look a little orange (the infants, that is; orange mothers should still be concerned). We’ve always known that breastfed infants tend to keep high levels of indirect bilirubin in their bloodstreams long after the first week in life, but no one yet had bothered to establish the typical range and time course. Dr. M. Jeffrey Maisels and a team from Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine changed all that with the use of transcutaneous bilirubin (TCB) monitors and 1,044 predominately breastfeeding infants.

Not only did they determine that at age 3-4 weeks between 34% and 43% of these infants still had TCB measurements over 5 mg/dL, they also reaffirmed that we doctors are really bad at guessing bilirubin levels from looking at babies. They asked trained clinicians to guess the “jaundice zone scores” of the infants, which sound like a customer loyalty program at a sporting goods store but are really just an estimate of how far down the infant’s body it looks yellow. The scores were so far off that a baby with a score of 0 could have a bilirubin level as high as 12.8 mg/dL. I can only hope that with his expertise in ferreting out bad human judgment, Dr. Maisels’s next study will investigate candidates for Congress.

Inattention

A complex society cannot function without some degree of trust; there’s all sorts of scary stuff I’d like to know, and I’m happy to pay a few dollars in taxes to make sure someone more qualified than I am is checking. Does this bridge I’m crossing have severe erosion? Is there another plane in our airspace? What was my 14-year-old daughter texting to her “boyfriend” last night? (Thanks, National Security Agency!)

Drug safety is one of those things, especially when many of my patients and one of my own children are taking said drug. A new study from researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital suggests that perhaps when it comes to the long-term safety of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not looked as hard as it might. Paging Dr. Edward Snowden!

One might assume that since up to 10% of U.S. children now carry a diagnosis of ADHD, and since those children start medications as young as age 4 and continue to use them for many years, the safety studies that got these drugs approved would have been especially rigorous. Yeah, no. Only 5 of 32 preapproval trials focused on safety, these trials enrolled an average of 75 patients (as opposed to the recommended 1,500), and few lasted as long as 12 months, with approval sometimes granted after only 8 weeks of study and some older drugs being “grandfathered” in with essentially no safety data whatsoever.

I see one bright spot in this desert of data. Whenever I prescribe a stimulant for ADHD, I’ll understand that I’m taking a gamble, and I’ll fondly remember our family trip to Las Vegas.

David L. Hill, M.D., FAAP, is the author of Dad to Dad: Parenting Like a Pro (AAP Publishing, 2012). He is also vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He serves as Program Director for the AAP Council on Communications and Media and as an executive committee member of the North Carolina Pediatric Society. He has recorded commentaries for NPR's All Things Considered and provided content for various print, television, and Internet outlets.

Is it time for telemedicine?

In the constantly advancing world of health information technology, the buzzwords are always changing. In the 90s, HIPAA dominated the literature. In the past few years, meaningful use took over. Most recently, a great deal of attention has been paid to telemedicine. For the uninitiated, telemedicine, a.k.a. telehealth, is not simply returning patient phone calls after hours. Telemedicine is the idea of substituting in-person patient encounters with virtual ones, typically using a secure video interface. In this column, we will explore a general overview of telemedicine and consider how this new medium fits into the ever-changing landscape of patient care.

The patient will ‘see’ you now

As evidenced by the feedback we have received on previous columns, many of our readers are still reeling from the arduous task of implementing an EHR and shudder at the thought of introducing even more technology into their office workflow. Others who enjoy being on the cutting edge of medicine are eager to embrace these virtual visits. We’ve spoken to several early adopters and have learned that it can be a rewarding way to handle certain patient interactions, but telemedicine obviously isn’t right for every patient or condition. Some feel that the lack of physical presence is not conducive to handling personal conversations or conveying sensitive information. Others have met with resistance from patients who just can’t get used to the idea of hands-free care. As with anything else, there will be patients who remain skeptical, but there will also be those who prefer it.

One patient we engaged saw his physician’s choice to offer virtual visits as a huge benefit, saying that "the idea of saving the 30 minutes of driving in each direction to visit the doctor, along with avoiding the hassle of taking time off work, makes [telehealth] a perfect way to handle my blood pressure control." In this case, as with others, patients use information from devices such as home blood pressure monitors or glucometers to supplement the visit and provide objective data. As home technology advances, connected devices are becoming more sophisticated and allowing more complicated diagnostics to be done remotely. Smartphone-connected otoscopes and ECG machines are just two examples of what’s to come, and we plan to highlight some of these in an upcoming column.

Getting started: Is it safe?

There are several things to consider when getting started in telemedicine in your practice. First is hardware. In general, this is fairly straightforward as most practices are now set up with broadband Internet and computers or tablets. Obviously, a good quality webcam is essential to ensure quality communication with patients. Beyond this, it’s critical to think about the security of the video interaction.

Standard consumer video-conferencing software such as Skype and Apple’s FaceTime are not HIPAA-compliant and can’t be used for patient communications. An encrypted video portal is essential to maintain patient privacy and make sure the patient interaction remains secure. The good news is that several easy-to-use software packages exist to allow this, if the functionality is not already built in to your EHR. A quick web search for "HIPAA-compliant video conferencing" returned several low-cost examples – some that are even free for a few interactions per month. This may be a good way to see if there is interest from patients prior to a large outlay of money. But what about the question of liability?

Unfortunately, physicians in the 21st century are wired to always be concerned about the threat of litigation, and there is no question that telemedicine offers a new opportunity for scrutiny of our clinical decisions. In addition, many rightfully fear the idea of diagnosis and treatment without the laying on of hands. As of now, there is little-to-no legal precedent for the malpractice implications of telehealth visits, but Teledoc, the country’s largest purveyor of telemedicine, advertises 7.5 million members and zero malpractice claims. Whether or not this is enough to convince the skeptics remains to be seen, but so far telemedicine has seemingly managed to fly below the radar of the courts. Following the pattern of all areas of medicine, this is likely to change, but it may be prevented if physicians limit the kinds of services offered through virtual visits. Many providers, such as Teledoc, for example, do not prescribe Drug Enforcement Administration–controlled or so-called nontherapeutic medications. (If you’re wondering, Viagra and Cialis are both on this list.) In this way, they are able to avoid becoming confused with illegitimate drug fulfillment warehouses and limit encounters that might raise questions of legality.

Can I get paid for this?

Although there are many conceivable benefits to telemedicine, such as access to patients who are homebound or live in isolated rural areas, it is hard to imagine setting off down the virtual path without the promise of reimbursement. According to the American Telemedicine Association, 21 states and Washington, D.C., require coverage of telemedicine services with reimbursement at a rate on par with in-person visits, while providers in the others are left wanting. Currently, 120 members of the U.S. Congress support various bills to expand the reach and acceptance of telemedicine, according to the telemedicine association, but it’s clear there is a long way to go before telemedicine receives the full support of insurers. In the meantime, its only financial benefit may be as a marketing advantage for practices. Those who leverage this may be able to draw new business from patients seeking more options in the delivery of their care.

Are you ready?

As with all burgeoning areas of health IT, telemedicine in its early stages appears at best like science fiction and at worst like just another headache. Unlike the other buzzwords of the past few years, adoption of telemedicine seems to be less of a requirement and more of an option. It may or may not work in your practice or for your patient population. Most importantly, though, it represents one point on the continuum of care that will take on an increasingly prominent role in the consumer-driven health care market, and it may represent a boon to both patients and providers alike.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

In the constantly advancing world of health information technology, the buzzwords are always changing. In the 90s, HIPAA dominated the literature. In the past few years, meaningful use took over. Most recently, a great deal of attention has been paid to telemedicine. For the uninitiated, telemedicine, a.k.a. telehealth, is not simply returning patient phone calls after hours. Telemedicine is the idea of substituting in-person patient encounters with virtual ones, typically using a secure video interface. In this column, we will explore a general overview of telemedicine and consider how this new medium fits into the ever-changing landscape of patient care.

The patient will ‘see’ you now

As evidenced by the feedback we have received on previous columns, many of our readers are still reeling from the arduous task of implementing an EHR and shudder at the thought of introducing even more technology into their office workflow. Others who enjoy being on the cutting edge of medicine are eager to embrace these virtual visits. We’ve spoken to several early adopters and have learned that it can be a rewarding way to handle certain patient interactions, but telemedicine obviously isn’t right for every patient or condition. Some feel that the lack of physical presence is not conducive to handling personal conversations or conveying sensitive information. Others have met with resistance from patients who just can’t get used to the idea of hands-free care. As with anything else, there will be patients who remain skeptical, but there will also be those who prefer it.

One patient we engaged saw his physician’s choice to offer virtual visits as a huge benefit, saying that "the idea of saving the 30 minutes of driving in each direction to visit the doctor, along with avoiding the hassle of taking time off work, makes [telehealth] a perfect way to handle my blood pressure control." In this case, as with others, patients use information from devices such as home blood pressure monitors or glucometers to supplement the visit and provide objective data. As home technology advances, connected devices are becoming more sophisticated and allowing more complicated diagnostics to be done remotely. Smartphone-connected otoscopes and ECG machines are just two examples of what’s to come, and we plan to highlight some of these in an upcoming column.

Getting started: Is it safe?

There are several things to consider when getting started in telemedicine in your practice. First is hardware. In general, this is fairly straightforward as most practices are now set up with broadband Internet and computers or tablets. Obviously, a good quality webcam is essential to ensure quality communication with patients. Beyond this, it’s critical to think about the security of the video interaction.

Standard consumer video-conferencing software such as Skype and Apple’s FaceTime are not HIPAA-compliant and can’t be used for patient communications. An encrypted video portal is essential to maintain patient privacy and make sure the patient interaction remains secure. The good news is that several easy-to-use software packages exist to allow this, if the functionality is not already built in to your EHR. A quick web search for "HIPAA-compliant video conferencing" returned several low-cost examples – some that are even free for a few interactions per month. This may be a good way to see if there is interest from patients prior to a large outlay of money. But what about the question of liability?

Unfortunately, physicians in the 21st century are wired to always be concerned about the threat of litigation, and there is no question that telemedicine offers a new opportunity for scrutiny of our clinical decisions. In addition, many rightfully fear the idea of diagnosis and treatment without the laying on of hands. As of now, there is little-to-no legal precedent for the malpractice implications of telehealth visits, but Teledoc, the country’s largest purveyor of telemedicine, advertises 7.5 million members and zero malpractice claims. Whether or not this is enough to convince the skeptics remains to be seen, but so far telemedicine has seemingly managed to fly below the radar of the courts. Following the pattern of all areas of medicine, this is likely to change, but it may be prevented if physicians limit the kinds of services offered through virtual visits. Many providers, such as Teledoc, for example, do not prescribe Drug Enforcement Administration–controlled or so-called nontherapeutic medications. (If you’re wondering, Viagra and Cialis are both on this list.) In this way, they are able to avoid becoming confused with illegitimate drug fulfillment warehouses and limit encounters that might raise questions of legality.

Can I get paid for this?

Although there are many conceivable benefits to telemedicine, such as access to patients who are homebound or live in isolated rural areas, it is hard to imagine setting off down the virtual path without the promise of reimbursement. According to the American Telemedicine Association, 21 states and Washington, D.C., require coverage of telemedicine services with reimbursement at a rate on par with in-person visits, while providers in the others are left wanting. Currently, 120 members of the U.S. Congress support various bills to expand the reach and acceptance of telemedicine, according to the telemedicine association, but it’s clear there is a long way to go before telemedicine receives the full support of insurers. In the meantime, its only financial benefit may be as a marketing advantage for practices. Those who leverage this may be able to draw new business from patients seeking more options in the delivery of their care.

Are you ready?

As with all burgeoning areas of health IT, telemedicine in its early stages appears at best like science fiction and at worst like just another headache. Unlike the other buzzwords of the past few years, adoption of telemedicine seems to be less of a requirement and more of an option. It may or may not work in your practice or for your patient population. Most importantly, though, it represents one point on the continuum of care that will take on an increasingly prominent role in the consumer-driven health care market, and it may represent a boon to both patients and providers alike.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

In the constantly advancing world of health information technology, the buzzwords are always changing. In the 90s, HIPAA dominated the literature. In the past few years, meaningful use took over. Most recently, a great deal of attention has been paid to telemedicine. For the uninitiated, telemedicine, a.k.a. telehealth, is not simply returning patient phone calls after hours. Telemedicine is the idea of substituting in-person patient encounters with virtual ones, typically using a secure video interface. In this column, we will explore a general overview of telemedicine and consider how this new medium fits into the ever-changing landscape of patient care.

The patient will ‘see’ you now

As evidenced by the feedback we have received on previous columns, many of our readers are still reeling from the arduous task of implementing an EHR and shudder at the thought of introducing even more technology into their office workflow. Others who enjoy being on the cutting edge of medicine are eager to embrace these virtual visits. We’ve spoken to several early adopters and have learned that it can be a rewarding way to handle certain patient interactions, but telemedicine obviously isn’t right for every patient or condition. Some feel that the lack of physical presence is not conducive to handling personal conversations or conveying sensitive information. Others have met with resistance from patients who just can’t get used to the idea of hands-free care. As with anything else, there will be patients who remain skeptical, but there will also be those who prefer it.

One patient we engaged saw his physician’s choice to offer virtual visits as a huge benefit, saying that "the idea of saving the 30 minutes of driving in each direction to visit the doctor, along with avoiding the hassle of taking time off work, makes [telehealth] a perfect way to handle my blood pressure control." In this case, as with others, patients use information from devices such as home blood pressure monitors or glucometers to supplement the visit and provide objective data. As home technology advances, connected devices are becoming more sophisticated and allowing more complicated diagnostics to be done remotely. Smartphone-connected otoscopes and ECG machines are just two examples of what’s to come, and we plan to highlight some of these in an upcoming column.

Getting started: Is it safe?

There are several things to consider when getting started in telemedicine in your practice. First is hardware. In general, this is fairly straightforward as most practices are now set up with broadband Internet and computers or tablets. Obviously, a good quality webcam is essential to ensure quality communication with patients. Beyond this, it’s critical to think about the security of the video interaction.

Standard consumer video-conferencing software such as Skype and Apple’s FaceTime are not HIPAA-compliant and can’t be used for patient communications. An encrypted video portal is essential to maintain patient privacy and make sure the patient interaction remains secure. The good news is that several easy-to-use software packages exist to allow this, if the functionality is not already built in to your EHR. A quick web search for "HIPAA-compliant video conferencing" returned several low-cost examples – some that are even free for a few interactions per month. This may be a good way to see if there is interest from patients prior to a large outlay of money. But what about the question of liability?

Unfortunately, physicians in the 21st century are wired to always be concerned about the threat of litigation, and there is no question that telemedicine offers a new opportunity for scrutiny of our clinical decisions. In addition, many rightfully fear the idea of diagnosis and treatment without the laying on of hands. As of now, there is little-to-no legal precedent for the malpractice implications of telehealth visits, but Teledoc, the country’s largest purveyor of telemedicine, advertises 7.5 million members and zero malpractice claims. Whether or not this is enough to convince the skeptics remains to be seen, but so far telemedicine has seemingly managed to fly below the radar of the courts. Following the pattern of all areas of medicine, this is likely to change, but it may be prevented if physicians limit the kinds of services offered through virtual visits. Many providers, such as Teledoc, for example, do not prescribe Drug Enforcement Administration–controlled or so-called nontherapeutic medications. (If you’re wondering, Viagra and Cialis are both on this list.) In this way, they are able to avoid becoming confused with illegitimate drug fulfillment warehouses and limit encounters that might raise questions of legality.

Can I get paid for this?

Although there are many conceivable benefits to telemedicine, such as access to patients who are homebound or live in isolated rural areas, it is hard to imagine setting off down the virtual path without the promise of reimbursement. According to the American Telemedicine Association, 21 states and Washington, D.C., require coverage of telemedicine services with reimbursement at a rate on par with in-person visits, while providers in the others are left wanting. Currently, 120 members of the U.S. Congress support various bills to expand the reach and acceptance of telemedicine, according to the telemedicine association, but it’s clear there is a long way to go before telemedicine receives the full support of insurers. In the meantime, its only financial benefit may be as a marketing advantage for practices. Those who leverage this may be able to draw new business from patients seeking more options in the delivery of their care.

Are you ready?

As with all burgeoning areas of health IT, telemedicine in its early stages appears at best like science fiction and at worst like just another headache. Unlike the other buzzwords of the past few years, adoption of telemedicine seems to be less of a requirement and more of an option. It may or may not work in your practice or for your patient population. Most importantly, though, it represents one point on the continuum of care that will take on an increasingly prominent role in the consumer-driven health care market, and it may represent a boon to both patients and providers alike.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

When ‘normal’ just isn’t normal

As pediatricians, we are constantly evaluating children of all ages. We make determinations of normal and abnormal all the time. But, sometimes determining normal can be a challenge because children come in all shapes, sizes, and complexions, so "normal" can appear in a variety of ways.

When it comes to the adolescent, this is an even greater challenge because the onset of puberty is so varied that children of the same age can look vastly different, and pubertal changes only widen the variety. Obesity also has impacted the appearance of normal because it makes children look older, pubertal changes more advanced, and a thorough exam more difficult. So when is it okay to say, "They will just grow out of it?" Well, the best answer is when all the serious illnesses have been considered and ruled out.

Gynecomastia is a common finding in the adolescent wellness exam; 50%-60% of adolescent males experience some degree of breast enlargement starting at the age of 10 years. This peaks at ages 13-14, then regresses over a period of 18 months (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1229-37). For approximately 25% of children, the breast tissue persists, which leads to significant anxiety and insecurities among adolescent males. Even when asked if they have concerns, few will admit to it because the thought of the evaluation is more than they can handle.

Gynecomastia is caused from the increased ratio of estrogen to androgen. Antiandrogens, drugs, and weight gain have all been implicated. But in the evaluation of increased breast tissue, normal as well as abnormal causes have to be considered.

Exogenous causes include herbal products, such as tea tree oil, or medications. The most common drugs are cimetidine, ranitidine, and omeprazole, as well spirolactone and ketoconazole. With the exception of spirolactone, these are all drugs that are used commonly for minor illness in children, but have been identified as a cause for gynecomastia. Discontinuation of these products usually resolves the issue within a few months (Pharmacotherapy 1993;13:37-45).

Obesity can cause a pseudogynecomastia as well as a true gynecomastia because aromatase enzyme increases with the increase in fat tissue, which converts testosterone to estradiol. Clinically, pseudogynecomastia can be distinguished from true gynecomastia by doing a breast exam. True gynecomastia is a concentric, rubbery firm mass greater than 0.5cm, and directly below the areola, where pseudogynecomastia has diffuse enlargement and no discernable glandular tissue.

Abnormal causes of gynecomastia are much less common, but do occur. A careful physical examination and a detailed review of systems can be very helpful in ruling in or out serious causes.

An imbalance of estrogen and testosterone can result from estrogen or testosterone going up or down. These changes can be caused by other hormonal stimulation. Human chorionic gonadotropin (HGC) is increased with germ cell tumors, which can be found in abdominal or testicular masses, resulting in secondary hypogonadism. Elevated estradiol is found with testicular tumors and adrenal tumors.

Hyperthyroidism can cause gynecomastia. Additional symptoms include palpitations, weight loss, and anxiety. Physical findings include a goiter, exophthalmoses, and tremors.

Klinefelter’s syndrome, a condition that occurs in men who have an extra X chromosome, includes gynecomastia and hypogonadism. There is a 20%-60% increased risk of breast cancer in these patients, who tend to have less facial and body hair, reduced muscle tone, and narrower shoulders and wider hips (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1229-37). Suspicion of breast cancer should increase if the mass is unilateral, nontender, and eccentric to the areola.

Although the vast majority of patients with gynecomastia will resolve spontaneously, careful evaluation and consideration of abnormal causes can lead to early diagnosis and treatment.

Experienced pediatricians know it’s never "nothing" unless all the possible "somethings" have been ruled out!

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. E-mail her at [email protected].

As pediatricians, we are constantly evaluating children of all ages. We make determinations of normal and abnormal all the time. But, sometimes determining normal can be a challenge because children come in all shapes, sizes, and complexions, so "normal" can appear in a variety of ways.

When it comes to the adolescent, this is an even greater challenge because the onset of puberty is so varied that children of the same age can look vastly different, and pubertal changes only widen the variety. Obesity also has impacted the appearance of normal because it makes children look older, pubertal changes more advanced, and a thorough exam more difficult. So when is it okay to say, "They will just grow out of it?" Well, the best answer is when all the serious illnesses have been considered and ruled out.

Gynecomastia is a common finding in the adolescent wellness exam; 50%-60% of adolescent males experience some degree of breast enlargement starting at the age of 10 years. This peaks at ages 13-14, then regresses over a period of 18 months (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1229-37). For approximately 25% of children, the breast tissue persists, which leads to significant anxiety and insecurities among adolescent males. Even when asked if they have concerns, few will admit to it because the thought of the evaluation is more than they can handle.

Gynecomastia is caused from the increased ratio of estrogen to androgen. Antiandrogens, drugs, and weight gain have all been implicated. But in the evaluation of increased breast tissue, normal as well as abnormal causes have to be considered.

Exogenous causes include herbal products, such as tea tree oil, or medications. The most common drugs are cimetidine, ranitidine, and omeprazole, as well spirolactone and ketoconazole. With the exception of spirolactone, these are all drugs that are used commonly for minor illness in children, but have been identified as a cause for gynecomastia. Discontinuation of these products usually resolves the issue within a few months (Pharmacotherapy 1993;13:37-45).

Obesity can cause a pseudogynecomastia as well as a true gynecomastia because aromatase enzyme increases with the increase in fat tissue, which converts testosterone to estradiol. Clinically, pseudogynecomastia can be distinguished from true gynecomastia by doing a breast exam. True gynecomastia is a concentric, rubbery firm mass greater than 0.5cm, and directly below the areola, where pseudogynecomastia has diffuse enlargement and no discernable glandular tissue.

Abnormal causes of gynecomastia are much less common, but do occur. A careful physical examination and a detailed review of systems can be very helpful in ruling in or out serious causes.

An imbalance of estrogen and testosterone can result from estrogen or testosterone going up or down. These changes can be caused by other hormonal stimulation. Human chorionic gonadotropin (HGC) is increased with germ cell tumors, which can be found in abdominal or testicular masses, resulting in secondary hypogonadism. Elevated estradiol is found with testicular tumors and adrenal tumors.

Hyperthyroidism can cause gynecomastia. Additional symptoms include palpitations, weight loss, and anxiety. Physical findings include a goiter, exophthalmoses, and tremors.

Klinefelter’s syndrome, a condition that occurs in men who have an extra X chromosome, includes gynecomastia and hypogonadism. There is a 20%-60% increased risk of breast cancer in these patients, who tend to have less facial and body hair, reduced muscle tone, and narrower shoulders and wider hips (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1229-37). Suspicion of breast cancer should increase if the mass is unilateral, nontender, and eccentric to the areola.

Although the vast majority of patients with gynecomastia will resolve spontaneously, careful evaluation and consideration of abnormal causes can lead to early diagnosis and treatment.

Experienced pediatricians know it’s never "nothing" unless all the possible "somethings" have been ruled out!

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. E-mail her at [email protected].

As pediatricians, we are constantly evaluating children of all ages. We make determinations of normal and abnormal all the time. But, sometimes determining normal can be a challenge because children come in all shapes, sizes, and complexions, so "normal" can appear in a variety of ways.

When it comes to the adolescent, this is an even greater challenge because the onset of puberty is so varied that children of the same age can look vastly different, and pubertal changes only widen the variety. Obesity also has impacted the appearance of normal because it makes children look older, pubertal changes more advanced, and a thorough exam more difficult. So when is it okay to say, "They will just grow out of it?" Well, the best answer is when all the serious illnesses have been considered and ruled out.

Gynecomastia is a common finding in the adolescent wellness exam; 50%-60% of adolescent males experience some degree of breast enlargement starting at the age of 10 years. This peaks at ages 13-14, then regresses over a period of 18 months (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1229-37). For approximately 25% of children, the breast tissue persists, which leads to significant anxiety and insecurities among adolescent males. Even when asked if they have concerns, few will admit to it because the thought of the evaluation is more than they can handle.

Gynecomastia is caused from the increased ratio of estrogen to androgen. Antiandrogens, drugs, and weight gain have all been implicated. But in the evaluation of increased breast tissue, normal as well as abnormal causes have to be considered.

Exogenous causes include herbal products, such as tea tree oil, or medications. The most common drugs are cimetidine, ranitidine, and omeprazole, as well spirolactone and ketoconazole. With the exception of spirolactone, these are all drugs that are used commonly for minor illness in children, but have been identified as a cause for gynecomastia. Discontinuation of these products usually resolves the issue within a few months (Pharmacotherapy 1993;13:37-45).

Obesity can cause a pseudogynecomastia as well as a true gynecomastia because aromatase enzyme increases with the increase in fat tissue, which converts testosterone to estradiol. Clinically, pseudogynecomastia can be distinguished from true gynecomastia by doing a breast exam. True gynecomastia is a concentric, rubbery firm mass greater than 0.5cm, and directly below the areola, where pseudogynecomastia has diffuse enlargement and no discernable glandular tissue.

Abnormal causes of gynecomastia are much less common, but do occur. A careful physical examination and a detailed review of systems can be very helpful in ruling in or out serious causes.

An imbalance of estrogen and testosterone can result from estrogen or testosterone going up or down. These changes can be caused by other hormonal stimulation. Human chorionic gonadotropin (HGC) is increased with germ cell tumors, which can be found in abdominal or testicular masses, resulting in secondary hypogonadism. Elevated estradiol is found with testicular tumors and adrenal tumors.

Hyperthyroidism can cause gynecomastia. Additional symptoms include palpitations, weight loss, and anxiety. Physical findings include a goiter, exophthalmoses, and tremors.

Klinefelter’s syndrome, a condition that occurs in men who have an extra X chromosome, includes gynecomastia and hypogonadism. There is a 20%-60% increased risk of breast cancer in these patients, who tend to have less facial and body hair, reduced muscle tone, and narrower shoulders and wider hips (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1229-37). Suspicion of breast cancer should increase if the mass is unilateral, nontender, and eccentric to the areola.

Although the vast majority of patients with gynecomastia will resolve spontaneously, careful evaluation and consideration of abnormal causes can lead to early diagnosis and treatment.

Experienced pediatricians know it’s never "nothing" unless all the possible "somethings" have been ruled out!

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. E-mail her at [email protected].

The Medical Roundtable: Pathophysiology of Headache Progression

DR. BURSTEIN: I am Rami Burstein. I am the academic director of the Headache Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Vice Chairman of Research in the Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care; and Professor of Anesthesia and Neuroscience at Harvard Medical School.

DR. CHARLES: I am Andrew Charles. I am a professor in the Department of Neurology at the UCLA School of Medicine and Director of the Headache Research and Treatment Program here.

DR. SCHOENEN: I’m Jean Schoenen. I’m a neurologist and professor at the University of Liege in Belgium and Director of the Headache Research Unit at the University hospital.

DR. GOADSBY: We are talking about the pathophysiology of headache progression, and in order to so, we should define at the start what we mean by “headache progression” so we’re all starting from the same point. Dr. Charles, when we talk about headache progression, what does it make you think about?

DR. CHARLES: It makes me think about a patient who has episodic migraine that occurs infrequently, let’s say once a month or once every other month, who at some point in the course of their life begins having headaches much more frequently, let’s say 2 or 3 or 4 times per week. Accompanying that, there may be a change in the quality of the headache, where it becomes somewhat less classic for episodic migraine and has fewer of the typical features that we consider associated with migraines.

DR. GOADSBY: That’s very helpful. What we’re really talking about and what we’re going to narrow ourselves down to is talking about the pathophysiology of migraine progression because we wouldn’t be able to cover all of the types of headaches. Dr. Schoenen, what is your comment on headache progression?

DR. SCHOENEN: I agree with what Dr. Charles said, although, clinically, I think that this disorder is quite heterogeneous between patients. Any migraineur has experienced, at some time in his life, progression of the disorder, where it becomes more frequent and then drops back again to its former frequency, but there seems to be a small population of patients in whom the disorder sometimes progress and then tips over into chronic migraine. That’s not the case for all migraineurs who progress, and many patients progress for some time and then do not progress up to what we call chronic migraines. So that may be something we have to consider from the pathophysiological point of view: What differs between those who progress to chronic migraine from those who do not?

DR. GOADSBY: Yes, you make a good point. Dr. Burstein?

DR. BURSTEIN: Maybe another aspect of the progression of headache is defined by treatment. When younger patients get a migraine, they go to sleep. When they wake up, their migraine is gone. They then progress to a point where they are unable to sleep off the migraine. They combine sleep with over-the-counter drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in order to abort the migraine. As the disease progresses, they need something stronger than sleep and NSAIDs. As the disease continues to progress and they develop symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and fatigue, they benefit less from sleep and NSAIDs and seek alternative therapies, such as triptans.

Eventually, some aspects of the progression make them more and more resistant to conventional treatment and clearly define a pathophysiological or pathological change that makes it more difficult for them to become pain-free or respond to medication.

DR. GOADSBY: I think the other aspect of this, which is not often stated but may be incredibly informative if we understood it, is the basis for the regression of this progression. It seems that the population estimates for chronic migraine are stable, and that there’s clearly a group of people for whom the frequency of headaches can increase each year. There must be, clearly, a group of people in equal size who go from having more headache to less headache, and I wish I thought that was because we treated them properly, but I don’t think that’s the case on a population basis.

The resolution is almost as interesting as the induction. When we talk about progression, we’re talking about addition of burden, whether in terms of frequency, change in the type of headache, or, as Dr. Burstein just said, treatment. The other aspect of progression that’s discussed is whether there’s any progression of a consequent nature: Progression to acquisition of brain changes and, what have been, I think, erroneously been called brain lesions, progression in cognitive function. Dr. Schoenen, do you have a view about any of those things?

DR. SCHOENEN: I do not really believe that the majority of migraine patients accumulate brain lesions over their lifetime, even when they progress. Most patients who progress and experience chronic migraines have migraines without aura, very few or no white-matter lesions, and very little or no increased risk for stroke.1 Brain lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were mainly reported in migraine-with-aura patients, and predominantly in females. The nature of these lesions is not known. In some studies, their prevalence was somewhat correlated with attack frequency, but the majority of subjects in the general population who suffer from migraine with aura experience low frequency of attacks. So, I do not believe that migraine without aura causes lesions in the brain, but I do believe that migraine without aura impairs, to some extent, cognitive performance, but that’s not related to the frequency of attacks, but likely due to the abnormal information processing that can be recorded in the brain of migraineurs between attacks.

DR. GOADSBY: Yes, exactly. Dr. Charles?

DR. CHARLES: The other imaging modalities that have shown changes are morphometric studies with MRI and functional MRI scans that show chronic changes in brain structure and function, particularly in areas related to pain processing, in patients with migraine. That is, I believe, something that may be occurring in patients who have progression of migraine, that there’s a plasticity of the brain that results in these structural and functional changes over time. I think that’s an area of great interest in terms of trying to understand how to reverse that process of progression.

DR. SCHOENEN: I agree completely with that. The problem is that many of these changes do not seem to be very specific to migraine. They are merely a consequence of the recurring head pain and also found in other pain disorders. Very few are specific to migraine. When patients develop chronic migraine, central sensitization occurs, and plastic changes appear in brain areas involved in pain processing and control. These areas are not specific to migraine. Taken together, I think brain changes seen in episodic migraine interictally are, for most cases, causally related to the disorder. In chronic migraine, these migraine-specific changes become overwhelmed by other brain modifications related to chronic pain, which have therapeutic implications.

DR. CHARLES: Yes, I agree.

DR. BURSTEIN: I think the biggest question that keeps coming up from all the imaging studies that show differences between migraine and non-migraine patients or migraine patients that progress and migraine patients that do not progress is what comes first: the changes that we see, which are responsible for the patient’s symptoms in the migraine, or the progression of the headache, which is causing the brain changes. For this, at least now, we don’t have a clear answer, although I think that most believe that progression of the migraine results in progressive changes and the beginning of brain malfunction. But the answer is not clear, and this belief somewhat conflicts with the concept of genetics, because if migraine patients do have genetic defects, you expect all changes to be there all along.

DR. GOADSBY: We currently have no clear data on what happens to migraineurs’ brains over time. Various changes in structure have been reported, but we do not know what happens, for example, if the migraine is controlled, do the brain changes revert? First, we must consider whether brain changes over time are linked with anything related to the headache. For example, if there’s high headache frequency or severity and then resolution, did changes occur? There don’t seem to be any long-term consequences of migraines. All the work done studying French people over the age of 70 on a population basis points to no untoward effect of a migraine on cognitive status,2 as do the data from the Women’s Health Study.3 Prospective examination of cognitive functions in that cohort identified absolutely no cognitive death attributable to migraine status. Whatever is happening in the brain can’t be all bad, since it doesn’t seem to have palpable consequences. I find that reassuring for patients.

DR. GOADSBY: I find the cognitive facts very reassuring for patients. I also find it reassuring to be able to tell them, even those with small changes, that as long as they live to even 75, they won’t have any particular problems.

I think we’ve probably come to the broad brush, that is, a group of migraineurs who have increased frequency and some change in quality. The treatment effects are perhaps most important for them. Before we go into the details of the pathophysiology, we should get some comments about the role of analgesic use, or the use of it in, as it is sometimes described, the evolution of migraines. Does analgesic use drive or follow the problem? I’ll start with Dr. Burstein.

DR. BURSTEIN: I belong to the group of people who believe that analgesics are overused, especially opiates and barbiturates, and contribute tremendously and significantly to the transition from acute to chronic pain, and from treatment that works to treatment that doesn’t work. They contribute on a molecular basis to sensitization; increase hyperexcitability; and add to the molecular aspects of the pathophysiology of increased excitability along the pain pathways in general, and in this case along the active trigeminovascular pain pathway.

DR. GOADSBY: We probably all agree that opioids are a problem, however, it’s how you look at it. Do you have in mind a particular site in the brain or particular pathways when you think about this process, or do you think “outside the brain” when you think about opioids and their role in this problem?

DR. BURSTEIN: I think that it will be in the first synapse between the peripheral and the central neuron. I think that the opioid’s ability to virtually bring to almost a complete stop the glutamate transporter and the inability of glutamate to clear itself out of the synapse contribute a lot to accessibility to susceptible pain neurons in the spinal cord, which is not where they eliminate pain. They eliminate pain in the brain stem, the rostral ventral inner medulla, the periaqueductal gray, and basal ganglia. When you eliminate the “off switch” by stopping medication, you’re left with a hyperexcitable spinal cord that has spinal glia that has a significantly reduced ability to clear glutamate from the synapse in the spinal cord.

DR. SCHOENEN: You’re right, but is that specific to migraine or not? Do you think that chronification due to medication overuse exists in other pain disorders?

DR. BURSTEIN: Yes, I think we have known that since 1988, when it first became clear in animal studies and then in human studies that opioids produced allodynia, hyperalgesia, and central sensitization.4

DR. SCHOENEN: I agree, but opioids are not a problem in Europe. Opioids are a problem in the United States. Analgesics containing opioids are very rarely overused in Europe right now because there are stricter limitations in their availability. The only one that still exists on the market is codeine combined with paracetamol. The most frequently overused preparations are non-opioid analgesics or NSAIDs combined with caffeine or triptans. The underlying process may be different between these molecules. Do you agree that it is possible that the daily intake of analgesics or NSAIDs by fibromyalgia patients, for instance, may play a role in chronifying their pain?

DR. BURSTEIN: Yes, I do. I think that whenever we prescribe opioids we make a big mistake, especially in the field of headache.

DR. GOADSBY: I will say one thing about Europe, when I was practicing there, the single biggest problem with overuse was codeine because codeine was available in the supermarkets. Medication overuse has regional and cultural dimensions, depending on what you have access to. Dr. Charles?

DR. CHARLES: I think with regard to the opioids, the other thing to keep in mind is that while they’re commonly viewed as having depressant or inhibitory actions, they in fact are excitatory in many areas of the brain, as well as the spinal cord. For example, most of the commonly used opioids can in fact cause seizures, and clearly have excitatory effects in the cortex. So it’s quite possible that in an episodic disorder of brain excitability, like migraine, they’re actually working not simply by changing pain, but also by changing some of the basic mechanisms until they reach a threshold that triggers migraine in the brain, even before the pain starts.

DR. GOADSBY: From that hypothesis, you might predict that patients with migraine with aura and opioid overuse would have more aura. You see where I’m headed with that?

DR. CHARLES: Sure. I wasn’t necessarily specifically referring to the visual cortex, but, in general, making the point that opioids have excitatory effects in the brain and using seizures as an example of a phenomenon, but not necessarily saying that it’s the cortex itself. Maybe it’s the hypothalamus or the thalamus or some other area of the brain in which they’re exerting excitatory effects.

DR. BURSTEIN: It can be the peripheral nervous system. Look, they produce itch, suggesting they are excitatory to certain classes of peripheral receptors.

DR. GOADSBY: Dr. Charles, do you agree that opioid-induced medication overuse problems precede as opposed to follow increased headache frequency, because there is this possibility that some medication overuse is simply because headache gets worse and patients just do what they need to do? I’m not sure lumping everyone together and saying everyone who overuses actually produces headache with the overuse so much as there’s more than one group.

DR. CHARLES: That’s right. Broadening the discussion to other medications, I think that it’s important to not lump all the acute medications for migraine into the same categories because they have such pharmacologically distinct properties that it isn’t plausible that they could all have the same effects. I think, as Dr. Schoenen mentioned, the combination analgesics, particularly those with caffeine, are particularly problematic. Recently in the United States, we’ve had a big uproar because of a shortage of one of the aspirin-and-caffeine-containing preparations. That, I think, is an example of how caffeine-containing preparations can be particularly problematic as a cause of medication-overuse headache.

DR. GOADSBY: Yes, I think the other component of this must be that there is some predisposition to it. The two studies that I’m aware of, the one that we were involved in in the rheumatology clinic and the one that Becker did in the gastro clinic, clearly show that there are people who overuse opioids by any standard definition who don’t have headache at all as a problem. So, there’s an important interaction, I think, between a genetic predisposition and these medicines. It’s something that would be wonderful to get at so we could be able to understand who are at risk and who aren’t at risk. One day I hope that we’ll be able to do that. Do you think that people who are at risk for one type of overuse are at risk for all? Let me ask Dr. Schoenen.

DR. SCHOENEN: I don’t know. I can only say that I see patients in whom overuse recurs and with a different drug. There are patients with overuse of a combined analgesic who return to an episodic form of migraine after drug withdrawal, but come back to my office 6 months or 1 year later with daily headache and daily use of a simple NSAID or analgesic. There may be a genetic predisposition to chronification by overuse of any anti-migraine drug, despite the fact that in practice simple NSAIDs are less likely to chronify the disorder.

Just to pick up what Andrew said, there is clearly a difference between the drugs and their effect on the brain. For example, looking at sensitivity in the somatosensory cortex with evoked potentials, there’s clearly a difference between patients overusing triptans and those taking NSAIDs, although their clinical phenotype is the same.

DR. SCHOENEN: Oh, yes. Well that was a study where we looked at metabolic changes with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in brain areas that belong to the so-called pain matrix, but also in areas that are known to be involved in substance abuse.5 What we found was that metabolism was clearly decreased in several areas that are thought to belong to the pain matrix, but these changes were reversible after withdrawal of the drug 3 weeks later. The only area where hypometabolism was not reversible after drug withdrawal was the orbitofrontal cortex. The orbitofrontal hypoactivity was even worse after withdrawal, and it was more pronounced in those patients who were overusing combined analgesics. The orbitofrontal cortex has been shown to play a crucial role in substance dependence. Its hypofunction could predispose patients to recurrence of medication-overuse headache. To prove this, we’re completing a long-term follow-up study.

DR. GOADSBY: That is interesting because I think that’s one of the important contributions to the pathophysiological understanding in humans.

DR. SCHOENEN: A Swiss group just published similar results measuring the amount of brain tissue with MRI.6 They found decreased tissue density in the orbitofrontal cortex, as well as in the dorsal pons, where abnormal activity is known to occur during migraine attacks.

DR. GOADSBY: You brought up nonsteroidals, a slightly more vexed issue. I’ll start with Dr. Charles. Do you think nonsteroidals, and you don’t have to lump them all together if you don’t want to, have a role in medication overuse in terms of inducing headache?

DR. CHARLES: My own view is no. It’s only the nonsteroidals in combination with caffeine that are the cause of medication overuse. I think that view is supported by the study by Bigal and Lipton,7 which basically suggests that, at a population level, frequent use of nonsteroidals is not associated with progression of headache. In fact, there’s a slight trend in the opposite direction, which has led them to suggest that it may possibly be protective. So, no, I do not put nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the same category as a cause, but I see them more as a consequence, or frequent use as a consequence of frequent headache rather than as a cause.

DR. GOADSBY: How do you see the difference in a mechanistic sense? I’ll give everyone a chance to weigh in on this.

DR. CHARLES: This is something that may have to do with agonism versus antagonism of receptors and specific mechanisms of analgesia. I think the things that we think about that are the significant players in terms of causing medication overuse are ones that are working on neurotransmitter receptors, like γ-aminobutyric acid receptors and opioid receptors, and, in the case of caffeine, maybe adenosine receptors. I think the issue with the nonsteroidals is harder to understand, particularly how they might pharmacologically actually cause medication overuse. So, I think that mechanistically, those are the questions that are before us now.

DR. GOADSBY: Dr. Burstein, you published on nonsteroidals and triptans in the context of sensitization.8 What’s your view about this, particularly at a mechanistic level?

DR. BURSTEIN: Mechanistically, the data suggest that triptans disrupt communication between peripheral and central trigeminovascular neurons and that NSAIDs inhibit both the peripheral and the central neurons.

Accordingly, it is reasonable to suggest that triptans do not reverse central sensitization because they do not inhibit central trigeminovascular neurons directly, not at the level of the spinal cord at least, and that NSAIDs reverse central sensitization indirectly, through their anti-inflammatory action in the spinal cord (mostly unknown mechanism).

I think, again, that in the context of the opioid treatment, it became apparent both in the animal data and in patient data that opioid treatment makes patients resistant to successful NSAID treatment. NSAIDs work much better in patients who do not have a history of favoring opioids. Once patients begin to use opioids, however, they see a noticeable decline in the potential benefit of NSAIDs or triptan treatments. Again, I think that the key to that is the spinal cord inability to clear glutamate from the synapse, although I don’t think that the NSAIDs target glutamate release in any way.

DR. SCHOENEN: I do partially agree with what has been said. I think clinically, we clearly see patients who with overuse of simple analgesics, like paracetamol or a single NSAID like ibuprofen, enter the vicious circle of chronification and reverse to episodic migraine after reducing intake of these drugs.

The second point is that in the electrophysiological studies of patients overusing simple NSAIDs, there is clearly indication of sensitization in sensory cortices. Thirdly, Dr. Charles was alluding to the Bigal et al. study showing that NSAIDs protect against migraine chronification contrary to triptans.6 In this study, however, the protective effect of NSAIDs was only seen with patients who had low frequency of headaches. In patients with high frequency of headaches at baseline, NSAIDs also had a deleterious effect.

DR. GOADSBY: In the last few minutes that we have, I’d like to get some views about whether you think that more aggressive treatment with preventives would be helpful in terms of restricting headache progression. When medical practitioners see people who experience 6 or 8 headaches a month, and a couple months later they have 10 or maybe 12 or 14, they want to help them get better before they get worse. So if we intervened earlier, do we think that we could do a better job? Is that mechanistically plausible? I’ll start with you, Dr. Charles.

DR. CHARLES: I think it’s an appealing concept, but unfortunately I think that in practice we don’t see that concept being realized. Taking a cynical view, I think in many cases, even with preventative therapy, migraine finds its way around them, and even patients on preventative therapy end up having progression. So I think until we better understand the process, we can’t really say with confidence that early preventive therapy is something that is going to prevent the progression of the disorder.

DR. GOADSBY: Dr. Schoenen?

DR. SCHOENEN: I fundamentally agree with that. I think we are very lousy in the prevention of migraine. Most of the drugs don’t reach 50% efficacy. The patients who respond to these drugs may be those who have a peculiar pathophysiological, possibly genetic, profile, and do not progress. Those who do not respond are probably those who are most prone to chronification of migraine and at last fail on all available preventative drugs. So, in addition to much better preventative treatments, we also really need many more treatments.

DR. GOADSBY: Yes. Dr. Burstein?

DR. BURSTEIN: Well, I want to take it in a slightly different direction. I am aware of the fact that there is no evidence for it because nobody has done the study, but the question that I would like to answer is whether migraine progression would look completely different in a group of patients whose migraine attacks were treated early from the first migraine attack in their life (ie, they didn’t let their migraine last more than a few hours). Comparing this "early-treatment" group to a group of patients who treat late (ie, they let themselves have a migraine for 8, 10, or 12 hours before it goes away by itself or before they treat it).

DR. GOADSBY: Well, that would be an interesting study, very expensive as well. But as you say, one of the things we lack very much in longitudinal study is what’s really a dreadful problem, because whatever we think about the pathophysiology of headache progression, we’d all agree it’s bad to have more headache, it’s bad to have worse headache, and it’s bad to have headaches that don’t respond to therapy. It’s a subject which deserves study.

FoxP2 Media LLC is the publisher of The Medical Roundtable.

DR. BURSTEIN: I am Rami Burstein. I am the academic director of the Headache Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Vice Chairman of Research in the Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care; and Professor of Anesthesia and Neuroscience at Harvard Medical School.

DR. CHARLES: I am Andrew Charles. I am a professor in the Department of Neurology at the UCLA School of Medicine and Director of the Headache Research and Treatment Program here.

DR. SCHOENEN: I’m Jean Schoenen. I’m a neurologist and professor at the University of Liege in Belgium and Director of the Headache Research Unit at the University hospital.

DR. GOADSBY: We are talking about the pathophysiology of headache progression, and in order to so, we should define at the start what we mean by “headache progression” so we’re all starting from the same point. Dr. Charles, when we talk about headache progression, what does it make you think about?

DR. CHARLES: It makes me think about a patient who has episodic migraine that occurs infrequently, let’s say once a month or once every other month, who at some point in the course of their life begins having headaches much more frequently, let’s say 2 or 3 or 4 times per week. Accompanying that, there may be a change in the quality of the headache, where it becomes somewhat less classic for episodic migraine and has fewer of the typical features that we consider associated with migraines.