User login

Up in the air

I find it scary to travel without my kids, even just to a meeting. I’m not sure what I fear more: that something is going to happen to me (like what, I’ll freeze to death in a conference room?) or that something will happen to one of them (with someone else driving them to school, they really will finally strangle each other). The person I should really be worried about is the sitter left to watch five kids all week! I’ll be relieved if when we get back she still has all her nose rings.

Learning curveball

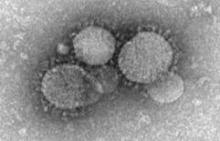

Have you ever kept doing something you knew was stupid, even after the thing everyone told you was going to happen happened? If you’ve ever had a hangover -- twice -- then are you really surprised that a resurgence of vaccine-preventable disease hasn’t done a thing to improve vaccination rates? People don’t make unwise choices accidentally; they work really hard at it.

If you’re like me, then ever since 1998 you’ve been saying, “Just wait until vaccine-preventable diseases make a comeback. Then those vaccine deniers will come to their senses.” Remember how innocent we were back in 1998? Just in case you had some lingering glimmer of hope for humanity, researchers from Seattle Children’s presented new findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ meeting earlier this month regarding a whooping cough outbreak in Washington State in 2011.

A team led by Dr. Elizabeth Wolf compared local pertussis vaccination rates before and during the outbreak, presuming that when people realized that their own babies were threatened by a deadly disease, they would, you know, respond. As it turns out, they did respond, either by denying that there was a threat or by ignoring that there was anything to do about it. I suppose these data don’t bode well for vaccine acceptance or, for that matter, for other problems where science points to an obvious solution that some people don’t want to accept, like gun safety and global warming. It’s enough to make me court a hangover -- my 23rd.

Well rounded

Have you gotten caught up in this fad for “life-hacking,” trying to save time and effort with tricks like using paper clips to organize electrical cables, painting look-alike house keys with colored nail polish, or not having five children? Now a study suggests a new way for pediatricians and parents to simplify: Don’t treat moderate to severe positional plagiocephaly with skull-molding helmets. I know, it’s not as cool as using a sawed-off water bottle to seal your unused chocolate chips, but it’ll save a lot more money, and you’re less likely to need stitches.

A group of Dutch researchers randomized 84 otherwise normal 5- to 6-month-old infants with moderate to severe positional plagiocephaly to 6 months of helmet therapy vs. 6 months of, well, not wearing helmets. (There’s just no feasible way to double-blind a helmet study.) End points involved careful measurements of the skull at 24 months of age as well as secondary findings like ear deviation, facial asymmetry, and whether parents argued over where they were going to find $2,500 for the helmet.

In the end, helmets made no difference whatsoever in outcomes. Helmet makers were swift to point out that the study excluded premature infants younger than 36 weeks and those with dysmorphic features or torticollis. It’s too early to gauge whether this study will actually lead providers and parents to turn to skull molding helmets less often, but think about it: With each helmet not prescribed, we’ll be able to save enough money to paint 10,000 previously indistinguishable keys with nail polish!

Short changed

Have you ever noticed that in every monster movie there’s that one scene where a cop, faced with a scaly creature roughly the size of the Staples Center, unloads the magazine of a handgun at it and then stares in terror to see that the beast is unfazed or, even worse, annoyed? When the American Academy of Pediatrics announced that its latest child health priority is poverty, some of us thought of the new AAP President James Perrin in the role of that ambitious but outgunned officer. (Full disclosure: I’ve met Dr. Perrin and, at the time, he was wearing neither dark blue nor a sidearm.)

For those who wonder why the AAP would take on a leviathan like poverty, there is a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences comparing African American children from severely underprivileged and privileged backgrounds. The investigators found a difference much deeper than whether family members used SAT words around the dinner table or, for that matter, could afford dinner. They discovered that destitution actually shortens children’s telomeres, leading to poorer health and a reduced life expectancy at the genetic level. These findings might lend us some perspective when our kids don’t get accepted to the first choice colleges.

These results make me want to go home at the end of this trip and hug my children, assuming we all survive. I already got them presents, and I even picked up something for the sitter. I hope she loves her new nose ring!

David L. Hill, M.D., FAAP is the author of Dad to Dad: Parenting Like a Pro (AAP Publishing, 2012). He is also vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He serves as Program Director for the AAP Council on Communications and Media and as an executive committee member of the North Carolina Pediatric Society. He has recorded commentaries for NPR's All Things Considered and provided content for various print, television, and Internet outlets.

I find it scary to travel without my kids, even just to a meeting. I’m not sure what I fear more: that something is going to happen to me (like what, I’ll freeze to death in a conference room?) or that something will happen to one of them (with someone else driving them to school, they really will finally strangle each other). The person I should really be worried about is the sitter left to watch five kids all week! I’ll be relieved if when we get back she still has all her nose rings.

Learning curveball

Have you ever kept doing something you knew was stupid, even after the thing everyone told you was going to happen happened? If you’ve ever had a hangover -- twice -- then are you really surprised that a resurgence of vaccine-preventable disease hasn’t done a thing to improve vaccination rates? People don’t make unwise choices accidentally; they work really hard at it.

If you’re like me, then ever since 1998 you’ve been saying, “Just wait until vaccine-preventable diseases make a comeback. Then those vaccine deniers will come to their senses.” Remember how innocent we were back in 1998? Just in case you had some lingering glimmer of hope for humanity, researchers from Seattle Children’s presented new findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ meeting earlier this month regarding a whooping cough outbreak in Washington State in 2011.

A team led by Dr. Elizabeth Wolf compared local pertussis vaccination rates before and during the outbreak, presuming that when people realized that their own babies were threatened by a deadly disease, they would, you know, respond. As it turns out, they did respond, either by denying that there was a threat or by ignoring that there was anything to do about it. I suppose these data don’t bode well for vaccine acceptance or, for that matter, for other problems where science points to an obvious solution that some people don’t want to accept, like gun safety and global warming. It’s enough to make me court a hangover -- my 23rd.

Well rounded

Have you gotten caught up in this fad for “life-hacking,” trying to save time and effort with tricks like using paper clips to organize electrical cables, painting look-alike house keys with colored nail polish, or not having five children? Now a study suggests a new way for pediatricians and parents to simplify: Don’t treat moderate to severe positional plagiocephaly with skull-molding helmets. I know, it’s not as cool as using a sawed-off water bottle to seal your unused chocolate chips, but it’ll save a lot more money, and you’re less likely to need stitches.

A group of Dutch researchers randomized 84 otherwise normal 5- to 6-month-old infants with moderate to severe positional plagiocephaly to 6 months of helmet therapy vs. 6 months of, well, not wearing helmets. (There’s just no feasible way to double-blind a helmet study.) End points involved careful measurements of the skull at 24 months of age as well as secondary findings like ear deviation, facial asymmetry, and whether parents argued over where they were going to find $2,500 for the helmet.

In the end, helmets made no difference whatsoever in outcomes. Helmet makers were swift to point out that the study excluded premature infants younger than 36 weeks and those with dysmorphic features or torticollis. It’s too early to gauge whether this study will actually lead providers and parents to turn to skull molding helmets less often, but think about it: With each helmet not prescribed, we’ll be able to save enough money to paint 10,000 previously indistinguishable keys with nail polish!

Short changed

Have you ever noticed that in every monster movie there’s that one scene where a cop, faced with a scaly creature roughly the size of the Staples Center, unloads the magazine of a handgun at it and then stares in terror to see that the beast is unfazed or, even worse, annoyed? When the American Academy of Pediatrics announced that its latest child health priority is poverty, some of us thought of the new AAP President James Perrin in the role of that ambitious but outgunned officer. (Full disclosure: I’ve met Dr. Perrin and, at the time, he was wearing neither dark blue nor a sidearm.)

For those who wonder why the AAP would take on a leviathan like poverty, there is a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences comparing African American children from severely underprivileged and privileged backgrounds. The investigators found a difference much deeper than whether family members used SAT words around the dinner table or, for that matter, could afford dinner. They discovered that destitution actually shortens children’s telomeres, leading to poorer health and a reduced life expectancy at the genetic level. These findings might lend us some perspective when our kids don’t get accepted to the first choice colleges.

These results make me want to go home at the end of this trip and hug my children, assuming we all survive. I already got them presents, and I even picked up something for the sitter. I hope she loves her new nose ring!

David L. Hill, M.D., FAAP is the author of Dad to Dad: Parenting Like a Pro (AAP Publishing, 2012). He is also vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He serves as Program Director for the AAP Council on Communications and Media and as an executive committee member of the North Carolina Pediatric Society. He has recorded commentaries for NPR's All Things Considered and provided content for various print, television, and Internet outlets.

I find it scary to travel without my kids, even just to a meeting. I’m not sure what I fear more: that something is going to happen to me (like what, I’ll freeze to death in a conference room?) or that something will happen to one of them (with someone else driving them to school, they really will finally strangle each other). The person I should really be worried about is the sitter left to watch five kids all week! I’ll be relieved if when we get back she still has all her nose rings.

Learning curveball

Have you ever kept doing something you knew was stupid, even after the thing everyone told you was going to happen happened? If you’ve ever had a hangover -- twice -- then are you really surprised that a resurgence of vaccine-preventable disease hasn’t done a thing to improve vaccination rates? People don’t make unwise choices accidentally; they work really hard at it.

If you’re like me, then ever since 1998 you’ve been saying, “Just wait until vaccine-preventable diseases make a comeback. Then those vaccine deniers will come to their senses.” Remember how innocent we were back in 1998? Just in case you had some lingering glimmer of hope for humanity, researchers from Seattle Children’s presented new findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ meeting earlier this month regarding a whooping cough outbreak in Washington State in 2011.

A team led by Dr. Elizabeth Wolf compared local pertussis vaccination rates before and during the outbreak, presuming that when people realized that their own babies were threatened by a deadly disease, they would, you know, respond. As it turns out, they did respond, either by denying that there was a threat or by ignoring that there was anything to do about it. I suppose these data don’t bode well for vaccine acceptance or, for that matter, for other problems where science points to an obvious solution that some people don’t want to accept, like gun safety and global warming. It’s enough to make me court a hangover -- my 23rd.

Well rounded

Have you gotten caught up in this fad for “life-hacking,” trying to save time and effort with tricks like using paper clips to organize electrical cables, painting look-alike house keys with colored nail polish, or not having five children? Now a study suggests a new way for pediatricians and parents to simplify: Don’t treat moderate to severe positional plagiocephaly with skull-molding helmets. I know, it’s not as cool as using a sawed-off water bottle to seal your unused chocolate chips, but it’ll save a lot more money, and you’re less likely to need stitches.

A group of Dutch researchers randomized 84 otherwise normal 5- to 6-month-old infants with moderate to severe positional plagiocephaly to 6 months of helmet therapy vs. 6 months of, well, not wearing helmets. (There’s just no feasible way to double-blind a helmet study.) End points involved careful measurements of the skull at 24 months of age as well as secondary findings like ear deviation, facial asymmetry, and whether parents argued over where they were going to find $2,500 for the helmet.

In the end, helmets made no difference whatsoever in outcomes. Helmet makers were swift to point out that the study excluded premature infants younger than 36 weeks and those with dysmorphic features or torticollis. It’s too early to gauge whether this study will actually lead providers and parents to turn to skull molding helmets less often, but think about it: With each helmet not prescribed, we’ll be able to save enough money to paint 10,000 previously indistinguishable keys with nail polish!

Short changed

Have you ever noticed that in every monster movie there’s that one scene where a cop, faced with a scaly creature roughly the size of the Staples Center, unloads the magazine of a handgun at it and then stares in terror to see that the beast is unfazed or, even worse, annoyed? When the American Academy of Pediatrics announced that its latest child health priority is poverty, some of us thought of the new AAP President James Perrin in the role of that ambitious but outgunned officer. (Full disclosure: I’ve met Dr. Perrin and, at the time, he was wearing neither dark blue nor a sidearm.)

For those who wonder why the AAP would take on a leviathan like poverty, there is a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences comparing African American children from severely underprivileged and privileged backgrounds. The investigators found a difference much deeper than whether family members used SAT words around the dinner table or, for that matter, could afford dinner. They discovered that destitution actually shortens children’s telomeres, leading to poorer health and a reduced life expectancy at the genetic level. These findings might lend us some perspective when our kids don’t get accepted to the first choice colleges.

These results make me want to go home at the end of this trip and hug my children, assuming we all survive. I already got them presents, and I even picked up something for the sitter. I hope she loves her new nose ring!

David L. Hill, M.D., FAAP is the author of Dad to Dad: Parenting Like a Pro (AAP Publishing, 2012). He is also vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He serves as Program Director for the AAP Council on Communications and Media and as an executive committee member of the North Carolina Pediatric Society. He has recorded commentaries for NPR's All Things Considered and provided content for various print, television, and Internet outlets.

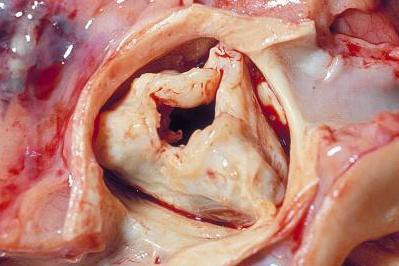

TAVR quickly penetrates to low-risk patients

Have too many low-risk U.S. patients undergone transcatheter aortic-valve replacement since the procedure became available in October 2012 to U.S. patients who are also judged eligible for surgical aortic-valve replacement?

Furthermore, regardless of the answer, are the tools currently available to cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to estimate a patient’s risk for undergoing aortic-valve surgery too limited and flawed to even allow clinicians to reasonably judge who is at high risk for surgical valve replacement and who isn’t?

And finally, have the benefits of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as an alternative to surgery become so compelling that patients, cardiologists, and surgeons are all now willing to ignore the possible downside that still remains to TAVR and the risk-level ground rules that the field set up just a few years ago?

Answering the third question is probably the easiest, and the answer seems to be yes, at least based on U.S. use of TAVR since the first valve system came onto the U.S. market for inoperable patients in November 2011, as well as on what happened in the latest big TAVR trial. Last November, researchers published a report on the first 7,710 U.S. TAVR patients, while results from the latest big trial, the CoreValve pivotal trial, came out in March.

A key finding in the JAMA report last November on nearly 8,000 TAVR recipients, most of whom were operable patients once this indication received U.S. approval in 2012, was that the median Predicted Risk of Operative Mortality score by the formula crafted by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (the STS PROM score) was 7%, and a quarter of all U.S. patients had a score of 5% or less. Those risk levels are quite low relative to the levels in the first TAVR pivotal trial, the PARTNER I trial, and relative to how TAVR developers viewed the role for this technology when it first entered the U.S. market a couple of years ago.

In the first U.S. pivotal trial for TAVR in patients judged operable, a head-to-head comparison of TAVR and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), all enrolled patients had to have an STS PROM score of at least 10%, and the average score of enrolled patients was 11.8%. Labeling for the first U.S. approved TAVR system was for patients with an STS PROM score of at least 8%. The follow-up trial designed to test a second-generation TAVR device, PARTNER II, launched about 3 years ago and not scheduled to finish until the end of 2015, specifically targeted "intermediate-risk" patients with aortic stenosis, those with an STS PROM of 4%-8%. Even this next-generation-device trial, PARTNER II, wasn’t designed to target patients with risk levels of less than 4%, yet patients of that very sort have already received treatment with the first-generation device based on the registry results.

It’s not just the registry that shows a shift toward lower-risk patients. The CoreValve pivotal trial that pitted a different TAVR system head to head against SAVR showed more of the same. The trial was designed to enroll operable patients with a predicted 30-day mortality risk after SAVR of at least 15%, though the study left it up to clinicians to decide how to measure risk and gave them free rein to use parameters in addition to the STS PROM score. The result was that the average STS PROM score of enrolled patients in the CoreValve trial was 7%, and roughly 10% of enrolled patients had a score of less than 4%. The temptation to use TAVR on lower-risk patients seems to have been inescapable, happening in both the CoreValve trial as well as in the registry’s Sapien experience.

Of course, the CoreValve results also showed significant survival benefit from TAVR using the CoreValve system, a game-changing result.

Part of what has been going on with risk assessment is that in the CoreValve study as well as in routine practice, clinicians have been fudging their use of the STS PROM score when sizing up patients for TAVR. I asked several interventional cardiologists about this at the ACC meeting in March, and their answers were all variants of what Dr. James Hermiller told me: "It’s frailty that often gets a patient to TAVR, and frailty is hard to quantify. Frailty can exist even when the STS score is not high." And even though labeling for the first-generation TAVR system that all 7,710 of the first U.S. patients received specified an STS PROM score of at least 8%, Dr. David Holmes told me that for Medicare reimbursement, all that’s needed is for two cardiac surgeons to sign off on saying that the patient’s status warrants TAVR. "That’s what carries the day," he said.

Data from the new CoreValve study underscore how limited the STS PROM score is right now. The average score of the patients enrolled in the surgical arm of this study was 7.5%, which means that 7.5 % of the patients who underwent SAVR were predicted by the scoring system to die during the first 30 days after surgery. But the actual rate was 4.5%, "substantially lower," said the CoreValve report. STS PROM scoring resulted in a substantial overcall on predicted risk.

When TAVR was first introduced, experts had two caveats about its potential to completely replace SAVR. The first was uncertainty about the long-term durability (think 10 or more years) of TAVR. The second was uncertainty about the short- and intermediate-term safety and efficacy of TAVR, especially for the patients for whom conventional SAVR was a reasonable option.

Doubts about short- and intermediate-term efficacy arose with the first-generation TAVR device, Sapien, because of the issue of paravalvular leak and the inability of TAVR to surpass SAVR outcomes in the PARTNER I results, but those doubts have now been mostly swept away from by the CoreValve results, which established CoreValve as superior to SAVR and made it the current standard for essentially all patients who need their aortic valve replaced. Even if paravalvular leak is still an issue for some patients, patients treated with CoreValve, TAVR overall did significantly better after 1 year than SAVR in the CoreValve trial, which means that TAVR was best regardless of whether paravalvular leak was an issue for some patients. And this was in patients who represented a wide range of STS PROM risk, with close to 10% of enrolled patients having a score of less than 4%. A subanalysis showed that the low-risk patients derived as much benefit from CoreValve TAVR, compared with SAVR, as did higher-risk patients.

The long-term durability question still remains for now, but the substantial mortality benefit in the CoreValve trial seen after 1 year probably trumps that.

Researchers designed the TAVR trials to methodically progress through a spectrum of patient risk levels. As recently as a year ago, several experts told me that no way in the near future could TAVR be an option for low-risk patients with STS PROM scores of less than 4%. But that is not how it has worked out. Patients, cardiac surgeons, and cardiologists embraced TAVR way faster and tighter than anyone expected just a few years ago.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Have too many low-risk U.S. patients undergone transcatheter aortic-valve replacement since the procedure became available in October 2012 to U.S. patients who are also judged eligible for surgical aortic-valve replacement?

Furthermore, regardless of the answer, are the tools currently available to cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to estimate a patient’s risk for undergoing aortic-valve surgery too limited and flawed to even allow clinicians to reasonably judge who is at high risk for surgical valve replacement and who isn’t?

And finally, have the benefits of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as an alternative to surgery become so compelling that patients, cardiologists, and surgeons are all now willing to ignore the possible downside that still remains to TAVR and the risk-level ground rules that the field set up just a few years ago?

Answering the third question is probably the easiest, and the answer seems to be yes, at least based on U.S. use of TAVR since the first valve system came onto the U.S. market for inoperable patients in November 2011, as well as on what happened in the latest big TAVR trial. Last November, researchers published a report on the first 7,710 U.S. TAVR patients, while results from the latest big trial, the CoreValve pivotal trial, came out in March.

A key finding in the JAMA report last November on nearly 8,000 TAVR recipients, most of whom were operable patients once this indication received U.S. approval in 2012, was that the median Predicted Risk of Operative Mortality score by the formula crafted by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (the STS PROM score) was 7%, and a quarter of all U.S. patients had a score of 5% or less. Those risk levels are quite low relative to the levels in the first TAVR pivotal trial, the PARTNER I trial, and relative to how TAVR developers viewed the role for this technology when it first entered the U.S. market a couple of years ago.

In the first U.S. pivotal trial for TAVR in patients judged operable, a head-to-head comparison of TAVR and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), all enrolled patients had to have an STS PROM score of at least 10%, and the average score of enrolled patients was 11.8%. Labeling for the first U.S. approved TAVR system was for patients with an STS PROM score of at least 8%. The follow-up trial designed to test a second-generation TAVR device, PARTNER II, launched about 3 years ago and not scheduled to finish until the end of 2015, specifically targeted "intermediate-risk" patients with aortic stenosis, those with an STS PROM of 4%-8%. Even this next-generation-device trial, PARTNER II, wasn’t designed to target patients with risk levels of less than 4%, yet patients of that very sort have already received treatment with the first-generation device based on the registry results.

It’s not just the registry that shows a shift toward lower-risk patients. The CoreValve pivotal trial that pitted a different TAVR system head to head against SAVR showed more of the same. The trial was designed to enroll operable patients with a predicted 30-day mortality risk after SAVR of at least 15%, though the study left it up to clinicians to decide how to measure risk and gave them free rein to use parameters in addition to the STS PROM score. The result was that the average STS PROM score of enrolled patients in the CoreValve trial was 7%, and roughly 10% of enrolled patients had a score of less than 4%. The temptation to use TAVR on lower-risk patients seems to have been inescapable, happening in both the CoreValve trial as well as in the registry’s Sapien experience.

Of course, the CoreValve results also showed significant survival benefit from TAVR using the CoreValve system, a game-changing result.

Part of what has been going on with risk assessment is that in the CoreValve study as well as in routine practice, clinicians have been fudging their use of the STS PROM score when sizing up patients for TAVR. I asked several interventional cardiologists about this at the ACC meeting in March, and their answers were all variants of what Dr. James Hermiller told me: "It’s frailty that often gets a patient to TAVR, and frailty is hard to quantify. Frailty can exist even when the STS score is not high." And even though labeling for the first-generation TAVR system that all 7,710 of the first U.S. patients received specified an STS PROM score of at least 8%, Dr. David Holmes told me that for Medicare reimbursement, all that’s needed is for two cardiac surgeons to sign off on saying that the patient’s status warrants TAVR. "That’s what carries the day," he said.

Data from the new CoreValve study underscore how limited the STS PROM score is right now. The average score of the patients enrolled in the surgical arm of this study was 7.5%, which means that 7.5 % of the patients who underwent SAVR were predicted by the scoring system to die during the first 30 days after surgery. But the actual rate was 4.5%, "substantially lower," said the CoreValve report. STS PROM scoring resulted in a substantial overcall on predicted risk.

When TAVR was first introduced, experts had two caveats about its potential to completely replace SAVR. The first was uncertainty about the long-term durability (think 10 or more years) of TAVR. The second was uncertainty about the short- and intermediate-term safety and efficacy of TAVR, especially for the patients for whom conventional SAVR was a reasonable option.

Doubts about short- and intermediate-term efficacy arose with the first-generation TAVR device, Sapien, because of the issue of paravalvular leak and the inability of TAVR to surpass SAVR outcomes in the PARTNER I results, but those doubts have now been mostly swept away from by the CoreValve results, which established CoreValve as superior to SAVR and made it the current standard for essentially all patients who need their aortic valve replaced. Even if paravalvular leak is still an issue for some patients, patients treated with CoreValve, TAVR overall did significantly better after 1 year than SAVR in the CoreValve trial, which means that TAVR was best regardless of whether paravalvular leak was an issue for some patients. And this was in patients who represented a wide range of STS PROM risk, with close to 10% of enrolled patients having a score of less than 4%. A subanalysis showed that the low-risk patients derived as much benefit from CoreValve TAVR, compared with SAVR, as did higher-risk patients.

The long-term durability question still remains for now, but the substantial mortality benefit in the CoreValve trial seen after 1 year probably trumps that.

Researchers designed the TAVR trials to methodically progress through a spectrum of patient risk levels. As recently as a year ago, several experts told me that no way in the near future could TAVR be an option for low-risk patients with STS PROM scores of less than 4%. But that is not how it has worked out. Patients, cardiac surgeons, and cardiologists embraced TAVR way faster and tighter than anyone expected just a few years ago.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Have too many low-risk U.S. patients undergone transcatheter aortic-valve replacement since the procedure became available in October 2012 to U.S. patients who are also judged eligible for surgical aortic-valve replacement?

Furthermore, regardless of the answer, are the tools currently available to cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to estimate a patient’s risk for undergoing aortic-valve surgery too limited and flawed to even allow clinicians to reasonably judge who is at high risk for surgical valve replacement and who isn’t?

And finally, have the benefits of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as an alternative to surgery become so compelling that patients, cardiologists, and surgeons are all now willing to ignore the possible downside that still remains to TAVR and the risk-level ground rules that the field set up just a few years ago?

Answering the third question is probably the easiest, and the answer seems to be yes, at least based on U.S. use of TAVR since the first valve system came onto the U.S. market for inoperable patients in November 2011, as well as on what happened in the latest big TAVR trial. Last November, researchers published a report on the first 7,710 U.S. TAVR patients, while results from the latest big trial, the CoreValve pivotal trial, came out in March.

A key finding in the JAMA report last November on nearly 8,000 TAVR recipients, most of whom were operable patients once this indication received U.S. approval in 2012, was that the median Predicted Risk of Operative Mortality score by the formula crafted by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (the STS PROM score) was 7%, and a quarter of all U.S. patients had a score of 5% or less. Those risk levels are quite low relative to the levels in the first TAVR pivotal trial, the PARTNER I trial, and relative to how TAVR developers viewed the role for this technology when it first entered the U.S. market a couple of years ago.

In the first U.S. pivotal trial for TAVR in patients judged operable, a head-to-head comparison of TAVR and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), all enrolled patients had to have an STS PROM score of at least 10%, and the average score of enrolled patients was 11.8%. Labeling for the first U.S. approved TAVR system was for patients with an STS PROM score of at least 8%. The follow-up trial designed to test a second-generation TAVR device, PARTNER II, launched about 3 years ago and not scheduled to finish until the end of 2015, specifically targeted "intermediate-risk" patients with aortic stenosis, those with an STS PROM of 4%-8%. Even this next-generation-device trial, PARTNER II, wasn’t designed to target patients with risk levels of less than 4%, yet patients of that very sort have already received treatment with the first-generation device based on the registry results.

It’s not just the registry that shows a shift toward lower-risk patients. The CoreValve pivotal trial that pitted a different TAVR system head to head against SAVR showed more of the same. The trial was designed to enroll operable patients with a predicted 30-day mortality risk after SAVR of at least 15%, though the study left it up to clinicians to decide how to measure risk and gave them free rein to use parameters in addition to the STS PROM score. The result was that the average STS PROM score of enrolled patients in the CoreValve trial was 7%, and roughly 10% of enrolled patients had a score of less than 4%. The temptation to use TAVR on lower-risk patients seems to have been inescapable, happening in both the CoreValve trial as well as in the registry’s Sapien experience.

Of course, the CoreValve results also showed significant survival benefit from TAVR using the CoreValve system, a game-changing result.

Part of what has been going on with risk assessment is that in the CoreValve study as well as in routine practice, clinicians have been fudging their use of the STS PROM score when sizing up patients for TAVR. I asked several interventional cardiologists about this at the ACC meeting in March, and their answers were all variants of what Dr. James Hermiller told me: "It’s frailty that often gets a patient to TAVR, and frailty is hard to quantify. Frailty can exist even when the STS score is not high." And even though labeling for the first-generation TAVR system that all 7,710 of the first U.S. patients received specified an STS PROM score of at least 8%, Dr. David Holmes told me that for Medicare reimbursement, all that’s needed is for two cardiac surgeons to sign off on saying that the patient’s status warrants TAVR. "That’s what carries the day," he said.

Data from the new CoreValve study underscore how limited the STS PROM score is right now. The average score of the patients enrolled in the surgical arm of this study was 7.5%, which means that 7.5 % of the patients who underwent SAVR were predicted by the scoring system to die during the first 30 days after surgery. But the actual rate was 4.5%, "substantially lower," said the CoreValve report. STS PROM scoring resulted in a substantial overcall on predicted risk.

When TAVR was first introduced, experts had two caveats about its potential to completely replace SAVR. The first was uncertainty about the long-term durability (think 10 or more years) of TAVR. The second was uncertainty about the short- and intermediate-term safety and efficacy of TAVR, especially for the patients for whom conventional SAVR was a reasonable option.

Doubts about short- and intermediate-term efficacy arose with the first-generation TAVR device, Sapien, because of the issue of paravalvular leak and the inability of TAVR to surpass SAVR outcomes in the PARTNER I results, but those doubts have now been mostly swept away from by the CoreValve results, which established CoreValve as superior to SAVR and made it the current standard for essentially all patients who need their aortic valve replaced. Even if paravalvular leak is still an issue for some patients, patients treated with CoreValve, TAVR overall did significantly better after 1 year than SAVR in the CoreValve trial, which means that TAVR was best regardless of whether paravalvular leak was an issue for some patients. And this was in patients who represented a wide range of STS PROM risk, with close to 10% of enrolled patients having a score of less than 4%. A subanalysis showed that the low-risk patients derived as much benefit from CoreValve TAVR, compared with SAVR, as did higher-risk patients.

The long-term durability question still remains for now, but the substantial mortality benefit in the CoreValve trial seen after 1 year probably trumps that.

Researchers designed the TAVR trials to methodically progress through a spectrum of patient risk levels. As recently as a year ago, several experts told me that no way in the near future could TAVR be an option for low-risk patients with STS PROM scores of less than 4%. But that is not how it has worked out. Patients, cardiac surgeons, and cardiologists embraced TAVR way faster and tighter than anyone expected just a few years ago.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Mobile health validation efforts in infancy

Hardly a day goes by anymore without an announcement of a new mobile health app, but there are precious few data to show which apps are useful in clinical or financial terms. Lots of people would like to change that, but how?

Three experts offered ideas in a recent opinion article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and some partnerships between academia and industry may be laying the groundwork for greater validation of new mobile health (mHealth) tools.

Of the more than 40,000 health, fitness, and medical apps on the market, reviews "have largely focused on personal impressions, rather than evidence-based, unbiased assessments of clinical performance and data security," Adam C. Powell, Ph.D., Dr. Adam B. Landman, and Dr. David W. Bates wrote in their article, "In Search of a Few Good Apps" (JAMA 2014;311:1851-2).

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) could play a greater role supporting development of mHealth app guidelines and, eventually, commission non-profit or for-profit entities to certify apps, as it does now for electronic health records, they suggested.

Dr. Powell is a Boston-based consultant. Dr. Landman, an emergency medicine specialist, is chief medical information officer for health information innovation and integration at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Bates is chief of general internal medicine and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s. Dr. Landman and Dr. Bates are both at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health mHealth Training Institute is educating an interdisciplinary group of researchers about the potential of mHealth and the need to evaluate these new tools. "If this effort is coupled with increased funding for mHealth research, it may help galvanize a larger body of evidence to inform mHealth app development and certification," the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a new partnership between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and Samsung Electronics aims to validate and commercialize promising digital tools for health care, including apps, in a Digital Health Innovation Lab. A few other universities recently entered into similar partnerships with industry.

Both UCSF and Samsung are making a "significant investment" to fund the lab but are not ready to release financial details, Dr. Michael Blum said in an interview.

The partnership initially will focus on preventive health, said Dr. Blum, who will direct the lab to be located at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. "There is no better way to treat disease than by avoiding it in the first place. [Moe than] 70% of our health care dollars are spent on avoidable disease," said Dr. Blum, a cardiologist who has been leading UCSF’s relatively new Center for Digital Health Innovation.

UCSF already has begun testing medical apps in clinical trials, such as a smoking cessation app, and will pursue clinical testing of tools including health sensors, wearable computing, and cloud-based analytics.

"There are many sites designing medical apps but very few are rigorously validated," Dr. Blum said. "We believe that validation is critical to the success of these apps and products. It is important for health care providers to know that they can trust the data and information which will lead to more consistent use and, hopefully, better outcomes for the users."

In Michigan, the William Davidson Foundation in January 2014 awarded $3 million to the Henry Ford Health System to create the William Davidson Center for Entrepreneurs in Digital Health. The center hopes to attract corporate partners and others to create, clinically validate, and commercialize digital health tools and to create a curriculum integrating health care, digital technologies, and entrepreneurship, according to a statement released by the Henry Ford Innovation Institute.

At the University of Colorado, Denver, the Center for Information Technology Innovation recently launched a Digital Health Consortium to bring its business school faculty together with entrepreneurs, health care providers, researchers, educators, and others to develop and clinically validate the next generation of digital health tools. The Center is funded by its members, which include the university and more than 30 Colorado information technology business leaders.

As each of these initiatives and others like them report results from their validation efforts, we’ll bring you the latest news on medical apps. Watch this space.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Hardly a day goes by anymore without an announcement of a new mobile health app, but there are precious few data to show which apps are useful in clinical or financial terms. Lots of people would like to change that, but how?

Three experts offered ideas in a recent opinion article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and some partnerships between academia and industry may be laying the groundwork for greater validation of new mobile health (mHealth) tools.

Of the more than 40,000 health, fitness, and medical apps on the market, reviews "have largely focused on personal impressions, rather than evidence-based, unbiased assessments of clinical performance and data security," Adam C. Powell, Ph.D., Dr. Adam B. Landman, and Dr. David W. Bates wrote in their article, "In Search of a Few Good Apps" (JAMA 2014;311:1851-2).

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) could play a greater role supporting development of mHealth app guidelines and, eventually, commission non-profit or for-profit entities to certify apps, as it does now for electronic health records, they suggested.

Dr. Powell is a Boston-based consultant. Dr. Landman, an emergency medicine specialist, is chief medical information officer for health information innovation and integration at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Bates is chief of general internal medicine and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s. Dr. Landman and Dr. Bates are both at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health mHealth Training Institute is educating an interdisciplinary group of researchers about the potential of mHealth and the need to evaluate these new tools. "If this effort is coupled with increased funding for mHealth research, it may help galvanize a larger body of evidence to inform mHealth app development and certification," the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a new partnership between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and Samsung Electronics aims to validate and commercialize promising digital tools for health care, including apps, in a Digital Health Innovation Lab. A few other universities recently entered into similar partnerships with industry.

Both UCSF and Samsung are making a "significant investment" to fund the lab but are not ready to release financial details, Dr. Michael Blum said in an interview.

The partnership initially will focus on preventive health, said Dr. Blum, who will direct the lab to be located at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. "There is no better way to treat disease than by avoiding it in the first place. [Moe than] 70% of our health care dollars are spent on avoidable disease," said Dr. Blum, a cardiologist who has been leading UCSF’s relatively new Center for Digital Health Innovation.

UCSF already has begun testing medical apps in clinical trials, such as a smoking cessation app, and will pursue clinical testing of tools including health sensors, wearable computing, and cloud-based analytics.

"There are many sites designing medical apps but very few are rigorously validated," Dr. Blum said. "We believe that validation is critical to the success of these apps and products. It is important for health care providers to know that they can trust the data and information which will lead to more consistent use and, hopefully, better outcomes for the users."

In Michigan, the William Davidson Foundation in January 2014 awarded $3 million to the Henry Ford Health System to create the William Davidson Center for Entrepreneurs in Digital Health. The center hopes to attract corporate partners and others to create, clinically validate, and commercialize digital health tools and to create a curriculum integrating health care, digital technologies, and entrepreneurship, according to a statement released by the Henry Ford Innovation Institute.

At the University of Colorado, Denver, the Center for Information Technology Innovation recently launched a Digital Health Consortium to bring its business school faculty together with entrepreneurs, health care providers, researchers, educators, and others to develop and clinically validate the next generation of digital health tools. The Center is funded by its members, which include the university and more than 30 Colorado information technology business leaders.

As each of these initiatives and others like them report results from their validation efforts, we’ll bring you the latest news on medical apps. Watch this space.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Hardly a day goes by anymore without an announcement of a new mobile health app, but there are precious few data to show which apps are useful in clinical or financial terms. Lots of people would like to change that, but how?

Three experts offered ideas in a recent opinion article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and some partnerships between academia and industry may be laying the groundwork for greater validation of new mobile health (mHealth) tools.

Of the more than 40,000 health, fitness, and medical apps on the market, reviews "have largely focused on personal impressions, rather than evidence-based, unbiased assessments of clinical performance and data security," Adam C. Powell, Ph.D., Dr. Adam B. Landman, and Dr. David W. Bates wrote in their article, "In Search of a Few Good Apps" (JAMA 2014;311:1851-2).

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) could play a greater role supporting development of mHealth app guidelines and, eventually, commission non-profit or for-profit entities to certify apps, as it does now for electronic health records, they suggested.

Dr. Powell is a Boston-based consultant. Dr. Landman, an emergency medicine specialist, is chief medical information officer for health information innovation and integration at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Bates is chief of general internal medicine and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s. Dr. Landman and Dr. Bates are both at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health mHealth Training Institute is educating an interdisciplinary group of researchers about the potential of mHealth and the need to evaluate these new tools. "If this effort is coupled with increased funding for mHealth research, it may help galvanize a larger body of evidence to inform mHealth app development and certification," the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a new partnership between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and Samsung Electronics aims to validate and commercialize promising digital tools for health care, including apps, in a Digital Health Innovation Lab. A few other universities recently entered into similar partnerships with industry.

Both UCSF and Samsung are making a "significant investment" to fund the lab but are not ready to release financial details, Dr. Michael Blum said in an interview.

The partnership initially will focus on preventive health, said Dr. Blum, who will direct the lab to be located at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. "There is no better way to treat disease than by avoiding it in the first place. [Moe than] 70% of our health care dollars are spent on avoidable disease," said Dr. Blum, a cardiologist who has been leading UCSF’s relatively new Center for Digital Health Innovation.

UCSF already has begun testing medical apps in clinical trials, such as a smoking cessation app, and will pursue clinical testing of tools including health sensors, wearable computing, and cloud-based analytics.

"There are many sites designing medical apps but very few are rigorously validated," Dr. Blum said. "We believe that validation is critical to the success of these apps and products. It is important for health care providers to know that they can trust the data and information which will lead to more consistent use and, hopefully, better outcomes for the users."

In Michigan, the William Davidson Foundation in January 2014 awarded $3 million to the Henry Ford Health System to create the William Davidson Center for Entrepreneurs in Digital Health. The center hopes to attract corporate partners and others to create, clinically validate, and commercialize digital health tools and to create a curriculum integrating health care, digital technologies, and entrepreneurship, according to a statement released by the Henry Ford Innovation Institute.

At the University of Colorado, Denver, the Center for Information Technology Innovation recently launched a Digital Health Consortium to bring its business school faculty together with entrepreneurs, health care providers, researchers, educators, and others to develop and clinically validate the next generation of digital health tools. The Center is funded by its members, which include the university and more than 30 Colorado information technology business leaders.

As each of these initiatives and others like them report results from their validation efforts, we’ll bring you the latest news on medical apps. Watch this space.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

RealSelf

If you have patients who express interest in cosmetic procedures, and especially if you are a cosmetic dermatologist or a plastic surgeon, you might want to familiarize yourself with RealSelf.com. Founded in 2006, RealSelf is an online community for learning and sharing information about cosmetic surgery, dermatology, dentistry, and other elective treatments. In 2013, the site had 36 million unique visitors, and it is expected to grow.

Why might RealSelf be relevant for you? Simply put, it’s another channel to market you and your practice. It works by allowing physicians to answer users’ questions about cosmetic procedures ranging from rhinoplasty and liposuction to tattoo removal and Botox. Over time, your participation can lead to new consultations at your practice.

To ensure credibility, physicians must be board-certified in order to join RealSelf’s physician community. There is an element of game mechanics: The more active the physician, the more exposure his or her profile and practice receives. Similarly, paid subscriptions lead to more exposure than free subscriptions (more on this later.) Although this model does not appeal to some physicians, many of them do like the platform, and see it as a way to build a reputation as an expert and to market their practices.

Unlike doctor review sites that focus on the physician, RealSelf focuses on the procedure. For each procedure, users will find actual patient reviews and before and after photos, as well as Q&A’s with board-certified physicians. Users will also find licensed physicians in their area as well as the average cost for the procedure. RealSelf believes that patients value transparency, and including prices creates transparency.

Since most patients genuinely want to help other patients make informed medical decisions, the reviews tend to be thoughtful and thorough, and many of them contain multiple before-and-after photos. As a physician perusing the patient reviews, you’ll start to notice that most of them are reasonable. For example, customer satisfaction with laser treatment for melasma was 51%, whereas satisfaction for laser treatment for rosacea was 80%.

Patients and prospective patients are flocking to the site because it allows them to share their experiences, interact with other patients, and gain access to physician experts in the field. Many patients have difficulty making decisions about cosmetic procedures; RealSelf aims to alleviate their fears and help them "make confident health and beauty decisions." If a prospective patient wants to see a video of tattoo removal or Botox injections, he or she can. If a patient wants to ask physicians their opinions, he or she can. According to RealSelf, physicians have answered over 500,000 questions on the site.

Of course, all this isn’t free for physicians. RealSelf is a business. They have a tiered membership – free, pro, and spotlight. To obtain free membership, you simply visit the site and follow the prompts to "claim your profile." Once your profile is completed, you will have access to a "doctor advisor" who can help you "optimize your visibility on the site." Both "pro" and "spotlight" offer additional benefits, such as integrating patient reviews on your practice website, promotions on Facebook and Twitter, extended directory listings, and exposure in your local area. RealSelf does not discuss costs of membership until you have claimed your profile.

Only you can determine if RealSelf is beneficial to you and your practice. If, for example, you’re not looking for new patients, then you might find it unnecessary. But at the very least, you’ll know what RealSelf is the next time a fellow cosmetic physician brings it up at a conference. And it’s never a bad idea to be familiar with current social technologies that may affect your livelihood.

If you’ve used RealSelf, let us know what you think. For more information, visit RealSelf.com.

Disclaimer: I have no financial interest in RealSelf and am not an active member.

Dr. Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

If you have patients who express interest in cosmetic procedures, and especially if you are a cosmetic dermatologist or a plastic surgeon, you might want to familiarize yourself with RealSelf.com. Founded in 2006, RealSelf is an online community for learning and sharing information about cosmetic surgery, dermatology, dentistry, and other elective treatments. In 2013, the site had 36 million unique visitors, and it is expected to grow.

Why might RealSelf be relevant for you? Simply put, it’s another channel to market you and your practice. It works by allowing physicians to answer users’ questions about cosmetic procedures ranging from rhinoplasty and liposuction to tattoo removal and Botox. Over time, your participation can lead to new consultations at your practice.

To ensure credibility, physicians must be board-certified in order to join RealSelf’s physician community. There is an element of game mechanics: The more active the physician, the more exposure his or her profile and practice receives. Similarly, paid subscriptions lead to more exposure than free subscriptions (more on this later.) Although this model does not appeal to some physicians, many of them do like the platform, and see it as a way to build a reputation as an expert and to market their practices.

Unlike doctor review sites that focus on the physician, RealSelf focuses on the procedure. For each procedure, users will find actual patient reviews and before and after photos, as well as Q&A’s with board-certified physicians. Users will also find licensed physicians in their area as well as the average cost for the procedure. RealSelf believes that patients value transparency, and including prices creates transparency.

Since most patients genuinely want to help other patients make informed medical decisions, the reviews tend to be thoughtful and thorough, and many of them contain multiple before-and-after photos. As a physician perusing the patient reviews, you’ll start to notice that most of them are reasonable. For example, customer satisfaction with laser treatment for melasma was 51%, whereas satisfaction for laser treatment for rosacea was 80%.

Patients and prospective patients are flocking to the site because it allows them to share their experiences, interact with other patients, and gain access to physician experts in the field. Many patients have difficulty making decisions about cosmetic procedures; RealSelf aims to alleviate their fears and help them "make confident health and beauty decisions." If a prospective patient wants to see a video of tattoo removal or Botox injections, he or she can. If a patient wants to ask physicians their opinions, he or she can. According to RealSelf, physicians have answered over 500,000 questions on the site.

Of course, all this isn’t free for physicians. RealSelf is a business. They have a tiered membership – free, pro, and spotlight. To obtain free membership, you simply visit the site and follow the prompts to "claim your profile." Once your profile is completed, you will have access to a "doctor advisor" who can help you "optimize your visibility on the site." Both "pro" and "spotlight" offer additional benefits, such as integrating patient reviews on your practice website, promotions on Facebook and Twitter, extended directory listings, and exposure in your local area. RealSelf does not discuss costs of membership until you have claimed your profile.

Only you can determine if RealSelf is beneficial to you and your practice. If, for example, you’re not looking for new patients, then you might find it unnecessary. But at the very least, you’ll know what RealSelf is the next time a fellow cosmetic physician brings it up at a conference. And it’s never a bad idea to be familiar with current social technologies that may affect your livelihood.

If you’ve used RealSelf, let us know what you think. For more information, visit RealSelf.com.

Disclaimer: I have no financial interest in RealSelf and am not an active member.

Dr. Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

If you have patients who express interest in cosmetic procedures, and especially if you are a cosmetic dermatologist or a plastic surgeon, you might want to familiarize yourself with RealSelf.com. Founded in 2006, RealSelf is an online community for learning and sharing information about cosmetic surgery, dermatology, dentistry, and other elective treatments. In 2013, the site had 36 million unique visitors, and it is expected to grow.

Why might RealSelf be relevant for you? Simply put, it’s another channel to market you and your practice. It works by allowing physicians to answer users’ questions about cosmetic procedures ranging from rhinoplasty and liposuction to tattoo removal and Botox. Over time, your participation can lead to new consultations at your practice.

To ensure credibility, physicians must be board-certified in order to join RealSelf’s physician community. There is an element of game mechanics: The more active the physician, the more exposure his or her profile and practice receives. Similarly, paid subscriptions lead to more exposure than free subscriptions (more on this later.) Although this model does not appeal to some physicians, many of them do like the platform, and see it as a way to build a reputation as an expert and to market their practices.

Unlike doctor review sites that focus on the physician, RealSelf focuses on the procedure. For each procedure, users will find actual patient reviews and before and after photos, as well as Q&A’s with board-certified physicians. Users will also find licensed physicians in their area as well as the average cost for the procedure. RealSelf believes that patients value transparency, and including prices creates transparency.

Since most patients genuinely want to help other patients make informed medical decisions, the reviews tend to be thoughtful and thorough, and many of them contain multiple before-and-after photos. As a physician perusing the patient reviews, you’ll start to notice that most of them are reasonable. For example, customer satisfaction with laser treatment for melasma was 51%, whereas satisfaction for laser treatment for rosacea was 80%.

Patients and prospective patients are flocking to the site because it allows them to share their experiences, interact with other patients, and gain access to physician experts in the field. Many patients have difficulty making decisions about cosmetic procedures; RealSelf aims to alleviate their fears and help them "make confident health and beauty decisions." If a prospective patient wants to see a video of tattoo removal or Botox injections, he or she can. If a patient wants to ask physicians their opinions, he or she can. According to RealSelf, physicians have answered over 500,000 questions on the site.

Of course, all this isn’t free for physicians. RealSelf is a business. They have a tiered membership – free, pro, and spotlight. To obtain free membership, you simply visit the site and follow the prompts to "claim your profile." Once your profile is completed, you will have access to a "doctor advisor" who can help you "optimize your visibility on the site." Both "pro" and "spotlight" offer additional benefits, such as integrating patient reviews on your practice website, promotions on Facebook and Twitter, extended directory listings, and exposure in your local area. RealSelf does not discuss costs of membership until you have claimed your profile.

Only you can determine if RealSelf is beneficial to you and your practice. If, for example, you’re not looking for new patients, then you might find it unnecessary. But at the very least, you’ll know what RealSelf is the next time a fellow cosmetic physician brings it up at a conference. And it’s never a bad idea to be familiar with current social technologies that may affect your livelihood.

If you’ve used RealSelf, let us know what you think. For more information, visit RealSelf.com.

Disclaimer: I have no financial interest in RealSelf and am not an active member.

Dr. Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

Law & Medicine: Antitrust issues in health care, part 2

Question: On antitrust, the U.S. courts have made the following statements, except:

A. To agree to prices is to fix them.

B. There is no learned profession exception to the antitrust laws.

C. To fix maximum price may amount to a fix of minimum price.

D. A group boycott of chiropractors violates the Sherman Act.

E. Tying arrangement in the health care industry is per se illegal.

Answer: E (see Jefferson Parish Hospital below). In the second part of the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court and other appellate courts began issuing a number of landmark opinions regarding health care economics and antitrust. Group boycotts were a major target, as was price fixing. This article briefly reviews a few of these decisions to impart a sense of how the judicial system views free market competition in health care.

In AMA v. United States (317 U.S. 519 [1943]), the issue was whether the medical profession’s leading organization, the American Medical Association, could be allowed to expel its salaried doctors or those who associated professionally with salaried doctors. Those who were denied AMA membership were naturally less able to compete (hospital privileges, consultations, etc.).

The U.S. Supreme Court held that such a group boycott of all salaried doctors was illegal because of its anticompetitive purpose, even if it allegedly promoted professional competence and public welfare.

Wilk v. AMA (895 F.2d 352 [1990]) was the culmination of a number of lawsuits surrounding the AMA and chiropractic. In 1963, the AMA had formed a Committee on Quackery aimed at eliminating chiropractic as a profession. The AMA Code of Ethics, Principle 3, opined that it was unethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors. In 1976, Dr. Wilk and four other licensed chiropractors filed suit against the AMA, and a jury trial found that the purpose of the boycott was to eliminate substantial competition without corresponding procompetitive benefits.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit subsequently affirmed the lower court’s finding that the AMA violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act in its illegal boycott of chiropractors, although the court did not answer the question as to whether chiropractic theory was in fact scientific. The court inquired into whether there was a genuine reasonable concern for the use of the scientific method in the doctor-patient relationship, and whether that concern was the dominating, motivating factor in the boycott, and if so, whether it could have been satisfied without restraining competition.

The court found that the AMA’s motive for the boycott was anticompetitive, believing that concern for patient care could be expressed, for example, through public-education campaigns. Although the AMA had formally removed Principle 3 in 1980, it nonetheless appealed this adverse decision to the U.S. Supreme Court on three separate occasions, but the latter declined to hear the case.

In Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar (421 U.S. 773 [1975]), the Virginia State Bar enforced an "advisory" minimum fee schedule for legal services. The U.S. Supreme Court found that this was an agreement to fix prices, holding, "This is not merely a case of an agreement that may be inferred from an exchange of price information ... for here a naked agreement was clearly shown, and the effect on prices is plain."

The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the practice of law was not a trade or commerce intended to be under Sherman Act scrutiny, declaring there was to be no "learned profession" exemption.

However, it noted that special considerations might apply, holding that "It would be unrealistic to view the practice of professions as interchangeable with other business activities, and automatically to apply to the professions antitrust concepts, which originated in other areas. The public service aspect, and other features of the professions, may require that a particular practice, which could properly be viewed as a violation of the Sherman Act in another context, be treated differently."

Following Goldfarb, there remains no doubt that professional services – legal, medical, and other services – are all to be governed by the antitrust laws.

A flurry of health care–related antitrust cases, including Patrick v. Burget (to be discussed in part 3), reached the courts in the 1980s. In Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Society (457 U.S. 332 [1982]), the county medical society set maximum allowable fees that member physicians could charge their patients, presumably to guard against price gouging. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, using the tough illegal per se standard, characterized the agreement as price fixing, despite it being for maximum rather than minimum fees.

The court ruled, "Maximum and minimum price fixing may have different consequences in many situations. But schemes to fix maximum prices, by substituting perhaps the erroneous judgment of a seller for the forces of the competitive market, may severely intrude upon the ability of buyers to compete and survive in that market. ... Maximum prices may be fixed too low ... may channel distribution through a few large or specifically advantaged dealers. ... Moreover, if the actual price charged under a maximum price scheme is nearly always the fixed maximum price, which is increasingly likely as the maximum price approaches the actual cost of the dealer, the scheme tends to acquire all the attributes of an arrangement fixing minimum prices."

At issue in Jefferson Parish Hospital District No. 2 v. Hyde (466 U.S. 2 [1984]) was an exclusive contract between a group of four anesthesiologists and Jefferson Parish Hospital in the New Orleans area. Dr. Hyde was an independent board-certified anesthesiologist who was denied medical staff privileges at the hospital because of this exclusive contract. The exclusive arrangement in effect required patients at the hospital to use the services of the four anesthesiologists and none others, raising the issue of unlawful "tying," where a seller requires a customer to purchase one product or service as a condition of being allowed to purchase another.

In a rare unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court, while agreeing that the contract was a tying arrangement, nonetheless rejected the argument that it was per se illegal or that it unreasonably restrained competition among anesthesiologists. The court reasoned that the hospital’s 30% share of the market did not amount to sufficient market power in the provision of hospital services in the Jefferson Parish area. Pointing out that every patient undergoing surgery needed anesthesia, the court found no evidence that any patient received unnecessary services, and it noted that the tying arrangement that was generally employed in the health care industry improved patient care and promoted hospital efficiency.

Tying arrangements in health care are frequently analyzed under a rule of reason standard instead of the strict per se standard, and the favorable decision in this specific case depended heavily on the hospitals’ relatively small market power.

Finally, consider a case on insurance reimbursement and a group boycott against a third-party payer. In Federal Trade Commission v. Indiana Federation of Dentists (476 U.S. 447 [1986]), dental health insurers in Indiana attempted to contain the cost of dental treatment by limiting payments to the least expensive yet adequate treatment suitable to the needs of the patient. The insurers required the submission of x-rays by treating dentists for review of their insurance claims.

Viewing such review of diagnostic and treatment decisions as a threat to their professional independence and economic well-being, members of the Indiana Dental Association and later the Indiana Federation of Dentists agreed collectively to refuse to submit the requested x-rays. These concerted activities resulted in the denial of information that dental customers had requested and had a right to know, and forced them to choose between acquiring the information in a more costly manner or forgoing it altogether.

The lower court had ruled in favor of the dentists, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed. It agreed that in the absence of concerted behavior, an individual dentist would have been subject to market forces of competition, creating incentives for him or her to comply with the requests of patients’ third-party insurers. But the conduct of the federation was tantamount to a group boycott, which unreasonably restrained trade. The court noted that while this was not price fixing as such, no elaborate industry analysis was required to demonstrate the anticompetitive character of such an agreement.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk", and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: On antitrust, the U.S. courts have made the following statements, except:

A. To agree to prices is to fix them.

B. There is no learned profession exception to the antitrust laws.

C. To fix maximum price may amount to a fix of minimum price.

D. A group boycott of chiropractors violates the Sherman Act.

E. Tying arrangement in the health care industry is per se illegal.

Answer: E (see Jefferson Parish Hospital below). In the second part of the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court and other appellate courts began issuing a number of landmark opinions regarding health care economics and antitrust. Group boycotts were a major target, as was price fixing. This article briefly reviews a few of these decisions to impart a sense of how the judicial system views free market competition in health care.

In AMA v. United States (317 U.S. 519 [1943]), the issue was whether the medical profession’s leading organization, the American Medical Association, could be allowed to expel its salaried doctors or those who associated professionally with salaried doctors. Those who were denied AMA membership were naturally less able to compete (hospital privileges, consultations, etc.).

The U.S. Supreme Court held that such a group boycott of all salaried doctors was illegal because of its anticompetitive purpose, even if it allegedly promoted professional competence and public welfare.

Wilk v. AMA (895 F.2d 352 [1990]) was the culmination of a number of lawsuits surrounding the AMA and chiropractic. In 1963, the AMA had formed a Committee on Quackery aimed at eliminating chiropractic as a profession. The AMA Code of Ethics, Principle 3, opined that it was unethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors. In 1976, Dr. Wilk and four other licensed chiropractors filed suit against the AMA, and a jury trial found that the purpose of the boycott was to eliminate substantial competition without corresponding procompetitive benefits.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit subsequently affirmed the lower court’s finding that the AMA violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act in its illegal boycott of chiropractors, although the court did not answer the question as to whether chiropractic theory was in fact scientific. The court inquired into whether there was a genuine reasonable concern for the use of the scientific method in the doctor-patient relationship, and whether that concern was the dominating, motivating factor in the boycott, and if so, whether it could have been satisfied without restraining competition.

The court found that the AMA’s motive for the boycott was anticompetitive, believing that concern for patient care could be expressed, for example, through public-education campaigns. Although the AMA had formally removed Principle 3 in 1980, it nonetheless appealed this adverse decision to the U.S. Supreme Court on three separate occasions, but the latter declined to hear the case.

In Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar (421 U.S. 773 [1975]), the Virginia State Bar enforced an "advisory" minimum fee schedule for legal services. The U.S. Supreme Court found that this was an agreement to fix prices, holding, "This is not merely a case of an agreement that may be inferred from an exchange of price information ... for here a naked agreement was clearly shown, and the effect on prices is plain."

The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the practice of law was not a trade or commerce intended to be under Sherman Act scrutiny, declaring there was to be no "learned profession" exemption.

However, it noted that special considerations might apply, holding that "It would be unrealistic to view the practice of professions as interchangeable with other business activities, and automatically to apply to the professions antitrust concepts, which originated in other areas. The public service aspect, and other features of the professions, may require that a particular practice, which could properly be viewed as a violation of the Sherman Act in another context, be treated differently."

Following Goldfarb, there remains no doubt that professional services – legal, medical, and other services – are all to be governed by the antitrust laws.

A flurry of health care–related antitrust cases, including Patrick v. Burget (to be discussed in part 3), reached the courts in the 1980s. In Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Society (457 U.S. 332 [1982]), the county medical society set maximum allowable fees that member physicians could charge their patients, presumably to guard against price gouging. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, using the tough illegal per se standard, characterized the agreement as price fixing, despite it being for maximum rather than minimum fees.