User login

What stalking victims need to restore their mental and somatic health

The obsessive pursuit of another has long been described in fiction and the scientific literature, but was conceptualized as “stalking” only relatively recently—first, under the guise of celebrity stalking and, later, as a public health issue recognized as affecting the general population. A useful working definition of stalking is “… the willful, malicious, and repeated following of and harassing of another person that threatens his/her safety.”1

Stalking victims report numerous, severe, life-changing effects from being stalked, including physical, social, and psychological harm. They typically experience mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms that require prompt evaluation and treatment.

Prevalence and other characteristics

Stalking and its subsequent victimization are common. Here are statistics:

• in the United States, approximately 1 million women and 370,000 men are stalked annually

• women are 3 times more likely to be stalked than raped2

• lifetime prevalence of stalking victimization is 20% (women, 23.5%; men, 10.5%)

• 75% of stalking victims are women

• 77% of stalking emerges from a prior acquaintance, including 49% that originated in a romantic relationship

• 33% of stalking encounters eventually lead to physical violence; slightly >10% of encounters lead to sexual violence

• stalking persists for an extended period; on average, almost 2 years.3

Penalties. Stalking can result in intervention by the criminal justice system. Legal sanctions levied on the perpetrator vary, depending on (among other variables) the severity of stalking; type of stalking; motive of the stalker; and the strength of incriminating evidence. Surprisingly, the outcome of the perpetrator’s prosecution (arrest, conviction, length of sentence) is unrelated to whether the victim reported continued stalking at follow-up.4,5

What are the symptoms and the damage? Given the intrusive nature of stalking behaviors and the extended period during which stalking persists, victims typically experience harmful psychological effects that range from subclinical symptoms to overt psychiatric disorders.

Stalking can have a profound impact on the victim and result in numerous psychological symptoms that become the focus of clinical attention. The typically chronic nature of stalking probably plays a significant role in its contributions to its victims’ psychological distress.6 Melton7 found that the most common adverse effect of stalking was related to the emotional impact of being stalked—with victims feeling scared, depressed, humiliated, embarrassed, distrustful of others, and angry or hateful.

Stalking victims report traumatic stress, hypervigilance, excessive fear, and anxiety coupled with disruptions in employment and social interactions.8 Many report having become highly distrustful or suspicious (44%); fearful (42%); nervous (31%); angry (27%); paranoid (36%); and depressed (21%). In general, victims have elevated scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist.9

Stalking in the setting of intimate partner abuse is associated with harmful outcomes for the victim. These include repeat physical violence, psychological distress, and impaired physical or mental health, or both.3,7,10

Stalking victims who are female; had a prior relationship with the stalker; have experienced a greater variety of stalking behaviors; are divorced or separated; and have received government assistance were found to be more likely to experience multiple negative outcomes from stalking.11

Effects on mental health. Stalking victims have a higher incidence of mental disorders and comorbid illnesses compared with the general population,12 with the most robust associations identified between stalking victimization, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder. Stalking contributes to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,13 and there is an association between posttraumatic stress and poor general health.14 Stalking victims report higher current use of psychotropic medications.12

Victims who blame themselves for being stalked report a significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who ruminate more about the stalking experience, or who explicitly emphasize the terror of stalking to a greater extent, also report a significantly higher severity of symptoms.15

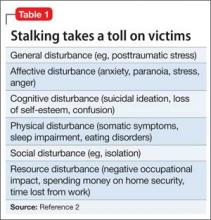

Spitzberg3 reported that stalking victimization has several possible effects on victims (Table 1).

Coping by movement. Victims might attempt to cope with stalking through several means,2 including:

• moving away—trying to avoid contact with the stalker

• moving with—negotiating a more acceptable form of relationship with the stalker

• moving against—attempting to harm, constrain, or punish the stalker

• moving inward—seeking self-control or self-actualization

• moving outward—seeking the assistance of others.

The degree of a victim’s symptoms correlates partially with the severity of stalking. However, other variables play a crucial role in explaining the level of distress among stalking victims15; these include the types of coping strategies adopted by victims. Self-blame, catastrophizing, and rumination are significantly associated with maladjustment; on the other hand, positive reappraisal—thoughts of attaching a positive meaning to the event, in terms of personal growth—is associated with greater psychological adjustment.

The more stalking a victim experiences (and, presumably, experiences greater distress), the greater the variety of coping strategies she (he) employs.16

How should stalking victims be treated?

Stalking victims are an underserved population. Practitioners often are unsure how to address stalking; furthermore, available treatments can be ineffective.

There is a great deal of variability in what professionals who work with stalking victims believe is appropriate practice. Services provided to victims vary widely,17 and the field has not yet come to a consensus on best practices.16

Proceed case by case. Practitioners must understand the nuances of each case to consider what might work at a particular point in time, and information from victims can help guide decision-making.16 Evidence suggests that stalking victims can feel frustrated in their attempt to seek help, particularly from the criminal justice system; it is possible that such bad experiences may dissuade them from seeking help later.5,8,18 It is worth noting that, as the frequency of stalking decreases for any given victim, her (his) perception of safety increases and distress diminishes.16

Few communities have attempted to address systemically the problem of stalking. Existing anti-stalking programs have focused on the criminal justice aspects of intervention,8 with less emphasis on treating victims.

Some stalking victims rely on friends and family for support and assistance, but research shows that most reach out to agencies for assistance and, generally, seek help from multiple sources.18 Typically, stalking victims are served by 2 types of victim service organizations:

• specialized, small, private and nonprofit agencies (eg, domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocacy organizations)

• small units housed in police departments and prosecutors’ offices.17

Note: When victims seek services at criminal justice agencies, they may be feeling particularly unsafe and distressed. This underscores the importance of co-locating victim service providers and criminal justice agencies.16

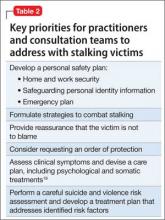

Stalking victims might benefit from multi-disciplinary team consultation, including input from psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and law enforcement or security professionals. Key priorities for practitioners to address with stalking victims are given in Table 2.19

Stalking behavior does not significantly decrease when victims are in contact with victim services.16 Practitioners can integrate this prospect into their understanding of stalking when they work with victims: That is, it is likely that the problem will not go away quickly, even with intervention.

Victims’ needs remain great and broad-based. Spence-Diehl et al17 conducted a survey of service providers for stalking victims, evaluating the needs of those victims and the response of their communities. Some of their recommendations for better meeting victims’ needs are in Table 3.16

Keeping victims at the center

Several authors have written about the need to return to a victim-centered model of care. This approach (1) puts the victim’s understanding of her (his) situation at the center of victim assistance work and (2) views service providers as consultants in the decision-making process.20,21 The victim-centered approach to treatment, in which the client has a greater voice and degree of control over interventions, is associated with positive outcomes.22,23

At the heart of a client-centered model of victim assistance is the provider’s ability to listen to a victim’s story and respond in a nonjudgmental manner. This approach honors the victim’s circumstances and her personal understanding of risk.21

Bottom Line

Stalking victims are a distinctive population, experiencing numerous emotional, physical, and social effects of their stalking over an extended period. Services to treat this underserved population need to be further developed. A multifaceted approach to treating victims incorporates psychological, somatic, and practical interventions, and a victim-centered approach is associated with better outcomes.

Related Resources

• Harmon RB, O’Connor M. Forcier A, et al. The impact of anti-stalking training on front line service providers: using the anti-stalking training evaluation protocol (ASTEP). J Forensic Science. 2004;49(5):1050-1055.

• Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12(1):64-86.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Meloy JR, Gothard S. Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):258-263.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/169592.pdf. Published April 1998. Accessed March 25, 2015.

3. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

4. McFarlane J, Willson P, Lemmey D, et al. Women filing assault charges on an intimate partner: criminal justice outcome and future violence experienced. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(4):396-408.

5. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of domestic violence: findings on the criminal justice system. Women & Criminal Justice. 2004;15:33-58.

6. Davies KE, Frieze IH. Research on stalking: what do we know and where do we go? Violence Vict. 2000;15(4):473-487.

7. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of intimate partner abuse: in the victims’ words. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2(4):346-363.

8. Spence-Diehl E. Intensive case management for victims of stalking: a pilot test evaluation. Brief Treatment Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(4):323-341.

9. Brewster MP. An exploration of the experiences and needs of former intimate stalking victims: final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. West Chester, PA: West Chester University; 1997.

10. Logan TK, Shannon L, Cole J, et al. The impact of differential patterns of physical violence and stalking on mental health and help-seeking among women with protective orders. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(9):866-886.

11. Johnson MC, Kercher GA. Identifying predictors of negative psychological reactions to stalking victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(5):866-882.

12. Kuehner C, Gass P, Dressing H. Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking—findings from a community study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):142-145.

13. Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, et al. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. J Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(5):413-421.

14. Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Traumatic distress among support-seeking female victims of stalking. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):795-798.

15. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Garnefski N, et al. The role of cognitive coping in female victims of stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1603-1612.

16. Bennett Cattaneo L, Cho S, Botuck S. Describing intimate partner stalking over time: an effort to inform victim-centered service provision. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(17):3428-3454.

17. Spence-Diehl E, Potocky-Tripodi M. Victims of stalking: a study of service needs as perceived by victim services practitioners. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(1):86-94.

18. Galeazzi GM, Buc˘ar-Ruc˘man A, DeFazio L, et al. Experiences of stalking victims and requests for help in three European countries. A survey. European Journal of Criminal Policy Research. 2009;15:243-260.

19. McEwan T, Purcell R. Assessing and surviving stalkers. Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2014; Chicago IL.

20. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. New directions in IPV risk assessment: an empowerment approach to risk management. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, eds. Intimate partner violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007:1-17.

21. Goodman LA, Epstein D. Listening to battered women: a survivor-centered approach to advocacy, mental health, and justice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

22. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. Through the lens of jurisprudence: the relationship between empowerment in the court system and well-being for intimate partner violence victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(3):481-502.

23. Zweig JM, Burt MR. Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: what matters to program clients? Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1149-1178.

The obsessive pursuit of another has long been described in fiction and the scientific literature, but was conceptualized as “stalking” only relatively recently—first, under the guise of celebrity stalking and, later, as a public health issue recognized as affecting the general population. A useful working definition of stalking is “… the willful, malicious, and repeated following of and harassing of another person that threatens his/her safety.”1

Stalking victims report numerous, severe, life-changing effects from being stalked, including physical, social, and psychological harm. They typically experience mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms that require prompt evaluation and treatment.

Prevalence and other characteristics

Stalking and its subsequent victimization are common. Here are statistics:

• in the United States, approximately 1 million women and 370,000 men are stalked annually

• women are 3 times more likely to be stalked than raped2

• lifetime prevalence of stalking victimization is 20% (women, 23.5%; men, 10.5%)

• 75% of stalking victims are women

• 77% of stalking emerges from a prior acquaintance, including 49% that originated in a romantic relationship

• 33% of stalking encounters eventually lead to physical violence; slightly >10% of encounters lead to sexual violence

• stalking persists for an extended period; on average, almost 2 years.3

Penalties. Stalking can result in intervention by the criminal justice system. Legal sanctions levied on the perpetrator vary, depending on (among other variables) the severity of stalking; type of stalking; motive of the stalker; and the strength of incriminating evidence. Surprisingly, the outcome of the perpetrator’s prosecution (arrest, conviction, length of sentence) is unrelated to whether the victim reported continued stalking at follow-up.4,5

What are the symptoms and the damage? Given the intrusive nature of stalking behaviors and the extended period during which stalking persists, victims typically experience harmful psychological effects that range from subclinical symptoms to overt psychiatric disorders.

Stalking can have a profound impact on the victim and result in numerous psychological symptoms that become the focus of clinical attention. The typically chronic nature of stalking probably plays a significant role in its contributions to its victims’ psychological distress.6 Melton7 found that the most common adverse effect of stalking was related to the emotional impact of being stalked—with victims feeling scared, depressed, humiliated, embarrassed, distrustful of others, and angry or hateful.

Stalking victims report traumatic stress, hypervigilance, excessive fear, and anxiety coupled with disruptions in employment and social interactions.8 Many report having become highly distrustful or suspicious (44%); fearful (42%); nervous (31%); angry (27%); paranoid (36%); and depressed (21%). In general, victims have elevated scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist.9

Stalking in the setting of intimate partner abuse is associated with harmful outcomes for the victim. These include repeat physical violence, psychological distress, and impaired physical or mental health, or both.3,7,10

Stalking victims who are female; had a prior relationship with the stalker; have experienced a greater variety of stalking behaviors; are divorced or separated; and have received government assistance were found to be more likely to experience multiple negative outcomes from stalking.11

Effects on mental health. Stalking victims have a higher incidence of mental disorders and comorbid illnesses compared with the general population,12 with the most robust associations identified between stalking victimization, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder. Stalking contributes to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,13 and there is an association between posttraumatic stress and poor general health.14 Stalking victims report higher current use of psychotropic medications.12

Victims who blame themselves for being stalked report a significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who ruminate more about the stalking experience, or who explicitly emphasize the terror of stalking to a greater extent, also report a significantly higher severity of symptoms.15

Spitzberg3 reported that stalking victimization has several possible effects on victims (Table 1).

Coping by movement. Victims might attempt to cope with stalking through several means,2 including:

• moving away—trying to avoid contact with the stalker

• moving with—negotiating a more acceptable form of relationship with the stalker

• moving against—attempting to harm, constrain, or punish the stalker

• moving inward—seeking self-control or self-actualization

• moving outward—seeking the assistance of others.

The degree of a victim’s symptoms correlates partially with the severity of stalking. However, other variables play a crucial role in explaining the level of distress among stalking victims15; these include the types of coping strategies adopted by victims. Self-blame, catastrophizing, and rumination are significantly associated with maladjustment; on the other hand, positive reappraisal—thoughts of attaching a positive meaning to the event, in terms of personal growth—is associated with greater psychological adjustment.

The more stalking a victim experiences (and, presumably, experiences greater distress), the greater the variety of coping strategies she (he) employs.16

How should stalking victims be treated?

Stalking victims are an underserved population. Practitioners often are unsure how to address stalking; furthermore, available treatments can be ineffective.

There is a great deal of variability in what professionals who work with stalking victims believe is appropriate practice. Services provided to victims vary widely,17 and the field has not yet come to a consensus on best practices.16

Proceed case by case. Practitioners must understand the nuances of each case to consider what might work at a particular point in time, and information from victims can help guide decision-making.16 Evidence suggests that stalking victims can feel frustrated in their attempt to seek help, particularly from the criminal justice system; it is possible that such bad experiences may dissuade them from seeking help later.5,8,18 It is worth noting that, as the frequency of stalking decreases for any given victim, her (his) perception of safety increases and distress diminishes.16

Few communities have attempted to address systemically the problem of stalking. Existing anti-stalking programs have focused on the criminal justice aspects of intervention,8 with less emphasis on treating victims.

Some stalking victims rely on friends and family for support and assistance, but research shows that most reach out to agencies for assistance and, generally, seek help from multiple sources.18 Typically, stalking victims are served by 2 types of victim service organizations:

• specialized, small, private and nonprofit agencies (eg, domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocacy organizations)

• small units housed in police departments and prosecutors’ offices.17

Note: When victims seek services at criminal justice agencies, they may be feeling particularly unsafe and distressed. This underscores the importance of co-locating victim service providers and criminal justice agencies.16

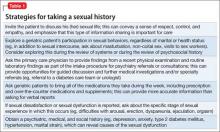

Stalking victims might benefit from multi-disciplinary team consultation, including input from psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and law enforcement or security professionals. Key priorities for practitioners to address with stalking victims are given in Table 2.19

Stalking behavior does not significantly decrease when victims are in contact with victim services.16 Practitioners can integrate this prospect into their understanding of stalking when they work with victims: That is, it is likely that the problem will not go away quickly, even with intervention.

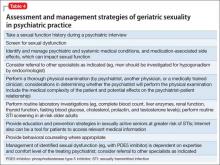

Victims’ needs remain great and broad-based. Spence-Diehl et al17 conducted a survey of service providers for stalking victims, evaluating the needs of those victims and the response of their communities. Some of their recommendations for better meeting victims’ needs are in Table 3.16

Keeping victims at the center

Several authors have written about the need to return to a victim-centered model of care. This approach (1) puts the victim’s understanding of her (his) situation at the center of victim assistance work and (2) views service providers as consultants in the decision-making process.20,21 The victim-centered approach to treatment, in which the client has a greater voice and degree of control over interventions, is associated with positive outcomes.22,23

At the heart of a client-centered model of victim assistance is the provider’s ability to listen to a victim’s story and respond in a nonjudgmental manner. This approach honors the victim’s circumstances and her personal understanding of risk.21

Bottom Line

Stalking victims are a distinctive population, experiencing numerous emotional, physical, and social effects of their stalking over an extended period. Services to treat this underserved population need to be further developed. A multifaceted approach to treating victims incorporates psychological, somatic, and practical interventions, and a victim-centered approach is associated with better outcomes.

Related Resources

• Harmon RB, O’Connor M. Forcier A, et al. The impact of anti-stalking training on front line service providers: using the anti-stalking training evaluation protocol (ASTEP). J Forensic Science. 2004;49(5):1050-1055.

• Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12(1):64-86.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The obsessive pursuit of another has long been described in fiction and the scientific literature, but was conceptualized as “stalking” only relatively recently—first, under the guise of celebrity stalking and, later, as a public health issue recognized as affecting the general population. A useful working definition of stalking is “… the willful, malicious, and repeated following of and harassing of another person that threatens his/her safety.”1

Stalking victims report numerous, severe, life-changing effects from being stalked, including physical, social, and psychological harm. They typically experience mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms that require prompt evaluation and treatment.

Prevalence and other characteristics

Stalking and its subsequent victimization are common. Here are statistics:

• in the United States, approximately 1 million women and 370,000 men are stalked annually

• women are 3 times more likely to be stalked than raped2

• lifetime prevalence of stalking victimization is 20% (women, 23.5%; men, 10.5%)

• 75% of stalking victims are women

• 77% of stalking emerges from a prior acquaintance, including 49% that originated in a romantic relationship

• 33% of stalking encounters eventually lead to physical violence; slightly >10% of encounters lead to sexual violence

• stalking persists for an extended period; on average, almost 2 years.3

Penalties. Stalking can result in intervention by the criminal justice system. Legal sanctions levied on the perpetrator vary, depending on (among other variables) the severity of stalking; type of stalking; motive of the stalker; and the strength of incriminating evidence. Surprisingly, the outcome of the perpetrator’s prosecution (arrest, conviction, length of sentence) is unrelated to whether the victim reported continued stalking at follow-up.4,5

What are the symptoms and the damage? Given the intrusive nature of stalking behaviors and the extended period during which stalking persists, victims typically experience harmful psychological effects that range from subclinical symptoms to overt psychiatric disorders.

Stalking can have a profound impact on the victim and result in numerous psychological symptoms that become the focus of clinical attention. The typically chronic nature of stalking probably plays a significant role in its contributions to its victims’ psychological distress.6 Melton7 found that the most common adverse effect of stalking was related to the emotional impact of being stalked—with victims feeling scared, depressed, humiliated, embarrassed, distrustful of others, and angry or hateful.

Stalking victims report traumatic stress, hypervigilance, excessive fear, and anxiety coupled with disruptions in employment and social interactions.8 Many report having become highly distrustful or suspicious (44%); fearful (42%); nervous (31%); angry (27%); paranoid (36%); and depressed (21%). In general, victims have elevated scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist.9

Stalking in the setting of intimate partner abuse is associated with harmful outcomes for the victim. These include repeat physical violence, psychological distress, and impaired physical or mental health, or both.3,7,10

Stalking victims who are female; had a prior relationship with the stalker; have experienced a greater variety of stalking behaviors; are divorced or separated; and have received government assistance were found to be more likely to experience multiple negative outcomes from stalking.11

Effects on mental health. Stalking victims have a higher incidence of mental disorders and comorbid illnesses compared with the general population,12 with the most robust associations identified between stalking victimization, major depressive disorder, and panic disorder. Stalking contributes to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder,13 and there is an association between posttraumatic stress and poor general health.14 Stalking victims report higher current use of psychotropic medications.12

Victims who blame themselves for being stalked report a significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who ruminate more about the stalking experience, or who explicitly emphasize the terror of stalking to a greater extent, also report a significantly higher severity of symptoms.15

Spitzberg3 reported that stalking victimization has several possible effects on victims (Table 1).

Coping by movement. Victims might attempt to cope with stalking through several means,2 including:

• moving away—trying to avoid contact with the stalker

• moving with—negotiating a more acceptable form of relationship with the stalker

• moving against—attempting to harm, constrain, or punish the stalker

• moving inward—seeking self-control or self-actualization

• moving outward—seeking the assistance of others.

The degree of a victim’s symptoms correlates partially with the severity of stalking. However, other variables play a crucial role in explaining the level of distress among stalking victims15; these include the types of coping strategies adopted by victims. Self-blame, catastrophizing, and rumination are significantly associated with maladjustment; on the other hand, positive reappraisal—thoughts of attaching a positive meaning to the event, in terms of personal growth—is associated with greater psychological adjustment.

The more stalking a victim experiences (and, presumably, experiences greater distress), the greater the variety of coping strategies she (he) employs.16

How should stalking victims be treated?

Stalking victims are an underserved population. Practitioners often are unsure how to address stalking; furthermore, available treatments can be ineffective.

There is a great deal of variability in what professionals who work with stalking victims believe is appropriate practice. Services provided to victims vary widely,17 and the field has not yet come to a consensus on best practices.16

Proceed case by case. Practitioners must understand the nuances of each case to consider what might work at a particular point in time, and information from victims can help guide decision-making.16 Evidence suggests that stalking victims can feel frustrated in their attempt to seek help, particularly from the criminal justice system; it is possible that such bad experiences may dissuade them from seeking help later.5,8,18 It is worth noting that, as the frequency of stalking decreases for any given victim, her (his) perception of safety increases and distress diminishes.16

Few communities have attempted to address systemically the problem of stalking. Existing anti-stalking programs have focused on the criminal justice aspects of intervention,8 with less emphasis on treating victims.

Some stalking victims rely on friends and family for support and assistance, but research shows that most reach out to agencies for assistance and, generally, seek help from multiple sources.18 Typically, stalking victims are served by 2 types of victim service organizations:

• specialized, small, private and nonprofit agencies (eg, domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocacy organizations)

• small units housed in police departments and prosecutors’ offices.17

Note: When victims seek services at criminal justice agencies, they may be feeling particularly unsafe and distressed. This underscores the importance of co-locating victim service providers and criminal justice agencies.16

Stalking victims might benefit from multi-disciplinary team consultation, including input from psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and law enforcement or security professionals. Key priorities for practitioners to address with stalking victims are given in Table 2.19

Stalking behavior does not significantly decrease when victims are in contact with victim services.16 Practitioners can integrate this prospect into their understanding of stalking when they work with victims: That is, it is likely that the problem will not go away quickly, even with intervention.

Victims’ needs remain great and broad-based. Spence-Diehl et al17 conducted a survey of service providers for stalking victims, evaluating the needs of those victims and the response of their communities. Some of their recommendations for better meeting victims’ needs are in Table 3.16

Keeping victims at the center

Several authors have written about the need to return to a victim-centered model of care. This approach (1) puts the victim’s understanding of her (his) situation at the center of victim assistance work and (2) views service providers as consultants in the decision-making process.20,21 The victim-centered approach to treatment, in which the client has a greater voice and degree of control over interventions, is associated with positive outcomes.22,23

At the heart of a client-centered model of victim assistance is the provider’s ability to listen to a victim’s story and respond in a nonjudgmental manner. This approach honors the victim’s circumstances and her personal understanding of risk.21

Bottom Line

Stalking victims are a distinctive population, experiencing numerous emotional, physical, and social effects of their stalking over an extended period. Services to treat this underserved population need to be further developed. A multifaceted approach to treating victims incorporates psychological, somatic, and practical interventions, and a victim-centered approach is associated with better outcomes.

Related Resources

• Harmon RB, O’Connor M. Forcier A, et al. The impact of anti-stalking training on front line service providers: using the anti-stalking training evaluation protocol (ASTEP). J Forensic Science. 2004;49(5):1050-1055.

• Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12(1):64-86.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Meloy JR, Gothard S. Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):258-263.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/169592.pdf. Published April 1998. Accessed March 25, 2015.

3. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

4. McFarlane J, Willson P, Lemmey D, et al. Women filing assault charges on an intimate partner: criminal justice outcome and future violence experienced. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(4):396-408.

5. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of domestic violence: findings on the criminal justice system. Women & Criminal Justice. 2004;15:33-58.

6. Davies KE, Frieze IH. Research on stalking: what do we know and where do we go? Violence Vict. 2000;15(4):473-487.

7. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of intimate partner abuse: in the victims’ words. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2(4):346-363.

8. Spence-Diehl E. Intensive case management for victims of stalking: a pilot test evaluation. Brief Treatment Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(4):323-341.

9. Brewster MP. An exploration of the experiences and needs of former intimate stalking victims: final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. West Chester, PA: West Chester University; 1997.

10. Logan TK, Shannon L, Cole J, et al. The impact of differential patterns of physical violence and stalking on mental health and help-seeking among women with protective orders. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(9):866-886.

11. Johnson MC, Kercher GA. Identifying predictors of negative psychological reactions to stalking victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(5):866-882.

12. Kuehner C, Gass P, Dressing H. Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking—findings from a community study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):142-145.

13. Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, et al. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. J Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(5):413-421.

14. Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Traumatic distress among support-seeking female victims of stalking. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):795-798.

15. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Garnefski N, et al. The role of cognitive coping in female victims of stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1603-1612.

16. Bennett Cattaneo L, Cho S, Botuck S. Describing intimate partner stalking over time: an effort to inform victim-centered service provision. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(17):3428-3454.

17. Spence-Diehl E, Potocky-Tripodi M. Victims of stalking: a study of service needs as perceived by victim services practitioners. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(1):86-94.

18. Galeazzi GM, Buc˘ar-Ruc˘man A, DeFazio L, et al. Experiences of stalking victims and requests for help in three European countries. A survey. European Journal of Criminal Policy Research. 2009;15:243-260.

19. McEwan T, Purcell R. Assessing and surviving stalkers. Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2014; Chicago IL.

20. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. New directions in IPV risk assessment: an empowerment approach to risk management. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, eds. Intimate partner violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007:1-17.

21. Goodman LA, Epstein D. Listening to battered women: a survivor-centered approach to advocacy, mental health, and justice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

22. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. Through the lens of jurisprudence: the relationship between empowerment in the court system and well-being for intimate partner violence victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(3):481-502.

23. Zweig JM, Burt MR. Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: what matters to program clients? Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1149-1178.

1. Meloy JR, Gothard S. Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):258-263.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/169592.pdf. Published April 1998. Accessed March 25, 2015.

3. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

4. McFarlane J, Willson P, Lemmey D, et al. Women filing assault charges on an intimate partner: criminal justice outcome and future violence experienced. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(4):396-408.

5. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of domestic violence: findings on the criminal justice system. Women & Criminal Justice. 2004;15:33-58.

6. Davies KE, Frieze IH. Research on stalking: what do we know and where do we go? Violence Vict. 2000;15(4):473-487.

7. Melton HC. Stalking in the context of intimate partner abuse: in the victims’ words. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2(4):346-363.

8. Spence-Diehl E. Intensive case management for victims of stalking: a pilot test evaluation. Brief Treatment Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(4):323-341.

9. Brewster MP. An exploration of the experiences and needs of former intimate stalking victims: final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. West Chester, PA: West Chester University; 1997.

10. Logan TK, Shannon L, Cole J, et al. The impact of differential patterns of physical violence and stalking on mental health and help-seeking among women with protective orders. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(9):866-886.

11. Johnson MC, Kercher GA. Identifying predictors of negative psychological reactions to stalking victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(5):866-882.

12. Kuehner C, Gass P, Dressing H. Increased risk of mental disorders among lifetime victims of stalking—findings from a community study. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):142-145.

13. Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, et al. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. J Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(5):413-421.

14. Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Traumatic distress among support-seeking female victims of stalking. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):795-798.

15. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Garnefski N, et al. The role of cognitive coping in female victims of stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(12):1603-1612.

16. Bennett Cattaneo L, Cho S, Botuck S. Describing intimate partner stalking over time: an effort to inform victim-centered service provision. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(17):3428-3454.

17. Spence-Diehl E, Potocky-Tripodi M. Victims of stalking: a study of service needs as perceived by victim services practitioners. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(1):86-94.

18. Galeazzi GM, Buc˘ar-Ruc˘man A, DeFazio L, et al. Experiences of stalking victims and requests for help in three European countries. A survey. European Journal of Criminal Policy Research. 2009;15:243-260.

19. McEwan T, Purcell R. Assessing and surviving stalkers. Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2014; Chicago IL.

20. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. New directions in IPV risk assessment: an empowerment approach to risk management. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, eds. Intimate partner violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2007:1-17.

21. Goodman LA, Epstein D. Listening to battered women: a survivor-centered approach to advocacy, mental health, and justice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

22. Cattaneo LB, Goodman LA. Through the lens of jurisprudence: the relationship between empowerment in the court system and well-being for intimate partner violence victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(3):481-502.

23. Zweig JM, Burt MR. Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: what matters to program clients? Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1149-1178.

Fatigue after depression responds to therapy. What are the next steps?

Fatigue and depression can be viewed as a “vicious cycle”: Fatigue can be a symptom of major depression, and fatigue can be a risk factor for depression.1 For example, fatigue associated with a general medical condition or traumatic brain injury can be a risk factor for developing major depressive disorder (MDD).1-3 It isn’t surprising that fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD.

Despite the observed association between fatigue and depression, their underlying relationship often is unclear. The literature does not differentiate among fatigue associated with depression, fatigue as a treatment-emergent adverse effect, and fatigue as a residual symptom of depression that is partially responsive to treatment.4,5 To complicate the situation, many medications used to treat MDD can cause fatigue.

Patients often describe fatigue as (1) feeling tired, exhausted, or drained and (2) lacking energy and motivation. Fatigue can be related to impaired wakefulness but is believed to be a different entity than sleepiness.6 Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health.

We reviewed the literature about fatigue as a symptom of MDD by conducting a search of Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using keywords depression, fatigue, residual symptoms, and treatment. We chose the papers cited in this article based on our consensus and because these publications represent expert opinion or the highest quality evidence available.

Residual fatigue has an effect on prognosis

Fatigue is a common symptom of MDD that persists in 20% to 30% of patients whose symptoms of depression otherwise remit.4,7-9 Several studies have linked residual fatigue with the overall prognosis of MDD.5 Data from a prospective study demonstrate that depressed patients have a higher risk of relapse when they continue to report symptoms of fatigue after their symptoms of depression have otherwise entered partial remission.10 Another study demonstrated that the severity of residual symptoms of depression is a strong predictor of another major depressive episode.11

In a large-scale study, the prevalence of residual fatigue after adequate treatment of MDD in both partial responders and remitters was 84.6%.12 The same study showed that one-third of patients who had been treated for MDD had persistent and clinically significant fatigue, which could suggest a relationship between fatigue and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants.

Another study demonstrated that 64.6% of patients who responded to antidepressant treatment and who had baseline fatigue continued to exhibit symptoms of fatigue after an adequate trial of an antidepressant.13

Neurobiological considerations

Studies have shown that the neuronal circuits that malfunction in fatigue are different from those that malfunction in depression.14 Although the neurobiology of fatigue has not been determined, decreased neuronal activity in the prefrontal circuits has been associated with symptoms of fatigue.15

In addition, evidence from the literature shows a decrease in hormone secretion16 and cognitive abilities in patients exhibiting symptoms of fatigue.17 These findings have led some experts to hypothesize that symptoms of fatigue associated with depression could be the result of (1) immune dysregulation18 and (2) an inability of available antidepressants to target the underlying biology of the disorder.2

Despite the hypothesis that fatigue associated with depression might be biologically related to immune dysregulation, some authors continue to point to an imbalance in neurotransmitters—norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, acetylcholine—as being associated with fatigue.14 For example, a study demonstrated that drugs targeting noradrenergic reuptake inhibition were more effective at preventing a relapse of fatigue compared with serotonergic drugs.19 Another study showed improvement in energy with an increase in the plasma level of desipramine, which affects noradrenergic neurotransmission.20

Inflammatory cytokines also have been explored in the search for an understanding of the etiology of fatigue and depression.21 Physical and mental stress promote the release of cytokines, which activate the immune system by inducing an inflammatory response; this response has been etiologically linked to depressive disorders.22 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated an elevated level of inflammatory cytokines in patients who have MDD— suggesting that MDD is associated with a chronic low level of inflammation that crosses the blood−brain barrier.23

Clinical considerations: A role for rating scales?

Despite the significance of residual fatigue on the quality of life of patients who have MDD, most common rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale24 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,25 have limited sensitivity for measuring fatigue.26 The Fatigue Associated with Depression (FAsD)27 questionnaire, designed according to FDA guidelines,28 is used to assess fatigue associated with depression. The final version of the FAsD includes 13 items: a 6-item experience subscale and a 7-item impact subscale.

Is the FAsD helpful? The experience subscale of the FAsD assesses how often the patient experiences different aspects of fatigue (tiredness, exhaustion, lack of energy, physical weakness, and a feeling that everything requires too much effort). The impact subscale of the FAsD assesses the effect of fatigue on daily life.

The overall FAsD score is calculated by taking the mean of each subscale; a change of 0.67 on the experience subscale and 0.57 on the impact subscale are considered clinically meaningful.27 The measurement properties of the questionnaire showed internal consistency, reliability, and validity in testing. Researchers note, however, that FAsD does not include items to assess the impact of fatigue on cognition. This means that the FAsD might not distinguish between physical and mental aspects of fatigue.

Treatment

It isn’t surprising that residual depression can increase health care utilization and economic burden, including such indirect costs as lost productivity and wages.29 Despite these impacts, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the relationship between residual symptoms, such as fatigue, and work productivity. It has been established that improving a depressed patient’s level of energy correlates with improved performance at work.

Treating fatigue as a residual symptom of MDD can be complicated because symptoms of fatigue might be:

• a discrete symptom of MDD

• a prodromal symptom of another disorder

• an adverse effect of an antidepressant.2,30

It is a major clinical problem, therefore, that antidepressants can alleviate and cause symptoms of fatigue.31 Treatment strategy should focus on identifying antidepressants that are less likely to cause fatigue (ie, noradrenergic or dopaminergic drugs, or both). Adjunctive treatments to target residual fatigue also can be used.32

There are limited published data on the effective treatment of residual fatigue in patients with MDD. Given the absence of sufficient evidence, agents that promote noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission have been the treatment of choice when targeting fatigue in depressed patients.2,14,21,33

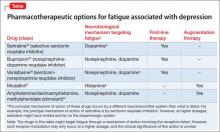

The Table34-37 lists potential treatment options often used to treat fatigue associated with depression.

SSRIs. Treatment with SSRIs has been associated with a low probability of achieving remission when targeting fatigue as a symptom of MDD.21

One study reported that, after 8 weeks of treatment with an SSRI, treatment-emergent adverse events, such as worsening fatigue and weakness, were observed—along with an overall lack of efficacy in targeting all symptoms of depression.38

Another study demonstrated positive effects when a noradrenergic agent was added to an SSRI in partial responders who continued to complain of residual fatigue.33

However, studies that compared the effects of SSRIs with those of antidepressants that have pronoradrenergic effects showed that the 2 mechanisms of action were not significantly different from each other in their ability to resolve residual symptoms of fatigue.21 A limiting factor might be that these studies were retrospective and did not analyze the efficacy of a noradrenergic agent as an adjunct for alleviating symptoms of fatigue.39

Bupropion. This commonly used medication for fatigue is believed to cause a significantly lower level of fatigue compared with SSRIs.40 The potential utility of bupropion in this area could be a reflection of its mechanism of action—ie, the drug targets both noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.41

A study comparing bupropion with SSRIs in targeting somatic symptoms of depression reported a small but statistically significant difference in favor of the bupropion-treated group. However, this finding was confounded by the small effect size and difficulty quantifying somatic symptoms.40

Stimulants and modafinil. Psycho-stimulants have been shown to be efficacious for depression and fatigue, both as monotherapy and adjunctively.39,42

Modafinil has demonstrated efficacy in open-label trials for improving residual fatigue, but failed to separate from placebo in controlled trials.43 At least 1 other failed study has been published examining modafinil as a treatment for fatigue associated with depression.43

Adjunctive therapy with CNS stimulants, such as amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, has been used to treat fatigue, with positive results.16 Modafinil and stimulants also could be tried as an augmentation strategy to other antidepressants; such use is off-label and should be attempted only after careful consideration.16

Exercise might be a nonpharmacotherapeutic modality that targets the underlying physiology associated with fatigue. Exercise releases endorphins, which can affect overall brain chemistry and which have been theorized to diminish symptoms of fatigue and depression.44 Consider exercise in addition to treatment with an antidepressant in selected patients.45

To sum up

In general, the literature does not recommend one medication as superior to any other for treating fatigue that is a residual symptom of depression. Such hesitation suggests that more empirical studies are needed to determine what is the best and proper management of treating fatigue associated with depression.

Bottom LinE

Fatigue can be a symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) or a risk factor for depression. Fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD. Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health and can result in increased utilization of health care services. A number of treatment options are available; none has been shown to be superior to the others.

Related Resources

• Leone SS. A disabling combination: fatigue and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):86-87.

• Targum SD, Fava M. Fatigue as a residual symptom of depression. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):40-43.

• Illiades C. How to fight depression fatigue. Everyday Health. http://www.everydayhealth.com/health-report/major-depression-living-well/fight-depression-fatigue.aspx.

• Kerr M. Depression and fatigue: a vicious cycle. Healthline. http://www.healthline.com/health/depression/fatigue.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Desipramine • Norpramin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Modafinil • Provigil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Sohail reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Macaluso has conducted clinical trials research as principal investigator for the following pharmaceutical manufacturers in the past 12 months: AbbVie, Inc.; Alkermes; AssureRx Health, Inc.; Eisai Co., Ltd.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Naurex Inc. All clinical trial and study contracts were with, and payments were made to, University of Kansas Medical Center Research Institute, Kansas City, Kansas, a research institute affiliated with University of Kansas School of Medicine−Wichita.

1. Schönberger M, Herrberg M, Ponsford J. Fatigue as a cause, not a consequence of depression and daytime sleepiness: a cross-lagged analysis. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(5):427-431.

2. Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J, Stahl, SM. The many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):93-105.

3. Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Temporal relations between unexplained fatigue and depression: longitudinal data from an international study in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):330-335.

4. Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41-50.

5. Kennedy N, Paykel ES. Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):135-144.

6. Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM. Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:63-76.

7. Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221-225.

8. Tylee A, Gastpar M, Lépine JP, et al. DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): a patient survey of the symptoms, disability and current management of depression in the community. DEPRES Steering Committee. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(3):139-151.

9. Marcus SM, Young EA, Kerber KB, et al. Gender differences in depression: findings from the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):141-150.

10. Paykel ES, Ramana, R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1171-1180.

11. Bockting CL, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, et al; Depression Evaluation Longitudinal Therapy Assessment Study Group. Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression and the influence of consecutive episodes on vulnerability for depression: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):747-755.

12. Greco T, Eckert G, Kroenke K. The outcome of physical symptoms with treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):813-818.

13. McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):180-186.

14. Stahl SM, Zhang L, Damatarca C, et al. Brain circuits determine destiny in depression: a novel approach to the psychopharmacology of wakefulness, fatigue, and executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):6-17.

15. MacHale SM, Law´rie SM, Cavanagh JT, et al. Cerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:550-556.

16. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

17. van den Heuvel OA, Groenewegen HJ, Barkhof F, et al. Frontostriatal system in planning complexity: a parametric functional magnetic resonance version of Tower of London task. Neuroimage. 2003;18(2):367-374.

18. Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, et al. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1310-1317.

19. Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):411-418.

20. Nelson JC, Mazure C, Quinlan DM, et al. Drug-responsive symptoms in melancholia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(7):663-668.

21. Fava M, Ball S, Nelson, JC, et al. Clinical relevance of fatigue as a residual symptom in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(3):250-257.

22. Anisman H, Merali Z, Poulter MO, et al. Cytokines as a precipitant of depressive illness: animal and human studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(8):963-972.

23. Simon NM, McNamara K, Chow CW, et al. A detailed examination of cytokine abnormalities in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(3):230-233.

24. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

25. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382-389.

26. Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, et al. Development and validation of a patient-report measure of fatigue associated with depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):294-303.

27. Matza LS, Wyrwich KW, Phillips GA, et al. The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD): responsiveness and responder definition. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):351-360.

28. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda. gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed May 7, 2015.

29. Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, et al. Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):e188-e196.

30. Fava M. Symptoms of fatigue and cognitive/executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder before and after antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):30-34.

31. Chang T, Fava M. The future of psychopharmacology of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(8):971-975.

32. Baldwin DS, Papakostas GI. Symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):9-15.

33. Ball SG, Dellva MA, D’Souza D, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of augmentation with LY2216684 for major depressive disorder patients who are partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [abstract P 05]. Int J Psych Clin Pract. 2010;14(suppl 1):19.

34. Stahl SM. Using secondary binding properties to select a not so elective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(12):642-643.

35. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

36. Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):699-711.

37. Scammell TE, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, et al. Hypothalamic arousal regions are activated during modafinil-induced wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2000;20(22):8620-8628.

38. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, et al. The relationship between adverse events during selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for major depressive disorder and nonremission in the suicide assessment methodology study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):31-38.

39. Nelson JC. A review of the efficacy of serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors for treatment of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1301-1308.

40. Papakostas GI, Nutt DJ, Hallett LA, et al. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1350-1355.

41. Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106-113.

42. Candy M, Jones CB, Williams R, et al. Psychostimulants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006722.pub2.

43. Lam JY, Freeman MK, Cates ME. Modafinil augmentation for residual symptoms of fatigue in patients with a partial response to antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(6):1005-1012.

44. Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clinical Psychol Rev. 2001;21(1):33-61.

45. Trivedi MH, Greer TL, Grannemann BD, et al. Exercise as an augmentation strategy for treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):205-213.

Fatigue and depression can be viewed as a “vicious cycle”: Fatigue can be a symptom of major depression, and fatigue can be a risk factor for depression.1 For example, fatigue associated with a general medical condition or traumatic brain injury can be a risk factor for developing major depressive disorder (MDD).1-3 It isn’t surprising that fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD.

Despite the observed association between fatigue and depression, their underlying relationship often is unclear. The literature does not differentiate among fatigue associated with depression, fatigue as a treatment-emergent adverse effect, and fatigue as a residual symptom of depression that is partially responsive to treatment.4,5 To complicate the situation, many medications used to treat MDD can cause fatigue.

Patients often describe fatigue as (1) feeling tired, exhausted, or drained and (2) lacking energy and motivation. Fatigue can be related to impaired wakefulness but is believed to be a different entity than sleepiness.6 Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health.

We reviewed the literature about fatigue as a symptom of MDD by conducting a search of Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using keywords depression, fatigue, residual symptoms, and treatment. We chose the papers cited in this article based on our consensus and because these publications represent expert opinion or the highest quality evidence available.

Residual fatigue has an effect on prognosis

Fatigue is a common symptom of MDD that persists in 20% to 30% of patients whose symptoms of depression otherwise remit.4,7-9 Several studies have linked residual fatigue with the overall prognosis of MDD.5 Data from a prospective study demonstrate that depressed patients have a higher risk of relapse when they continue to report symptoms of fatigue after their symptoms of depression have otherwise entered partial remission.10 Another study demonstrated that the severity of residual symptoms of depression is a strong predictor of another major depressive episode.11

In a large-scale study, the prevalence of residual fatigue after adequate treatment of MDD in both partial responders and remitters was 84.6%.12 The same study showed that one-third of patients who had been treated for MDD had persistent and clinically significant fatigue, which could suggest a relationship between fatigue and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants.

Another study demonstrated that 64.6% of patients who responded to antidepressant treatment and who had baseline fatigue continued to exhibit symptoms of fatigue after an adequate trial of an antidepressant.13

Neurobiological considerations

Studies have shown that the neuronal circuits that malfunction in fatigue are different from those that malfunction in depression.14 Although the neurobiology of fatigue has not been determined, decreased neuronal activity in the prefrontal circuits has been associated with symptoms of fatigue.15

In addition, evidence from the literature shows a decrease in hormone secretion16 and cognitive abilities in patients exhibiting symptoms of fatigue.17 These findings have led some experts to hypothesize that symptoms of fatigue associated with depression could be the result of (1) immune dysregulation18 and (2) an inability of available antidepressants to target the underlying biology of the disorder.2

Despite the hypothesis that fatigue associated with depression might be biologically related to immune dysregulation, some authors continue to point to an imbalance in neurotransmitters—norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, acetylcholine—as being associated with fatigue.14 For example, a study demonstrated that drugs targeting noradrenergic reuptake inhibition were more effective at preventing a relapse of fatigue compared with serotonergic drugs.19 Another study showed improvement in energy with an increase in the plasma level of desipramine, which affects noradrenergic neurotransmission.20

Inflammatory cytokines also have been explored in the search for an understanding of the etiology of fatigue and depression.21 Physical and mental stress promote the release of cytokines, which activate the immune system by inducing an inflammatory response; this response has been etiologically linked to depressive disorders.22 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated an elevated level of inflammatory cytokines in patients who have MDD— suggesting that MDD is associated with a chronic low level of inflammation that crosses the blood−brain barrier.23

Clinical considerations: A role for rating scales?

Despite the significance of residual fatigue on the quality of life of patients who have MDD, most common rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale24 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,25 have limited sensitivity for measuring fatigue.26 The Fatigue Associated with Depression (FAsD)27 questionnaire, designed according to FDA guidelines,28 is used to assess fatigue associated with depression. The final version of the FAsD includes 13 items: a 6-item experience subscale and a 7-item impact subscale.

Is the FAsD helpful? The experience subscale of the FAsD assesses how often the patient experiences different aspects of fatigue (tiredness, exhaustion, lack of energy, physical weakness, and a feeling that everything requires too much effort). The impact subscale of the FAsD assesses the effect of fatigue on daily life.

The overall FAsD score is calculated by taking the mean of each subscale; a change of 0.67 on the experience subscale and 0.57 on the impact subscale are considered clinically meaningful.27 The measurement properties of the questionnaire showed internal consistency, reliability, and validity in testing. Researchers note, however, that FAsD does not include items to assess the impact of fatigue on cognition. This means that the FAsD might not distinguish between physical and mental aspects of fatigue.

Treatment

It isn’t surprising that residual depression can increase health care utilization and economic burden, including such indirect costs as lost productivity and wages.29 Despite these impacts, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the relationship between residual symptoms, such as fatigue, and work productivity. It has been established that improving a depressed patient’s level of energy correlates with improved performance at work.

Treating fatigue as a residual symptom of MDD can be complicated because symptoms of fatigue might be:

• a discrete symptom of MDD

• a prodromal symptom of another disorder

• an adverse effect of an antidepressant.2,30

It is a major clinical problem, therefore, that antidepressants can alleviate and cause symptoms of fatigue.31 Treatment strategy should focus on identifying antidepressants that are less likely to cause fatigue (ie, noradrenergic or dopaminergic drugs, or both). Adjunctive treatments to target residual fatigue also can be used.32

There are limited published data on the effective treatment of residual fatigue in patients with MDD. Given the absence of sufficient evidence, agents that promote noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission have been the treatment of choice when targeting fatigue in depressed patients.2,14,21,33

The Table34-37 lists potential treatment options often used to treat fatigue associated with depression.

SSRIs. Treatment with SSRIs has been associated with a low probability of achieving remission when targeting fatigue as a symptom of MDD.21

One study reported that, after 8 weeks of treatment with an SSRI, treatment-emergent adverse events, such as worsening fatigue and weakness, were observed—along with an overall lack of efficacy in targeting all symptoms of depression.38

Another study demonstrated positive effects when a noradrenergic agent was added to an SSRI in partial responders who continued to complain of residual fatigue.33

However, studies that compared the effects of SSRIs with those of antidepressants that have pronoradrenergic effects showed that the 2 mechanisms of action were not significantly different from each other in their ability to resolve residual symptoms of fatigue.21 A limiting factor might be that these studies were retrospective and did not analyze the efficacy of a noradrenergic agent as an adjunct for alleviating symptoms of fatigue.39

Bupropion. This commonly used medication for fatigue is believed to cause a significantly lower level of fatigue compared with SSRIs.40 The potential utility of bupropion in this area could be a reflection of its mechanism of action—ie, the drug targets both noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.41

A study comparing bupropion with SSRIs in targeting somatic symptoms of depression reported a small but statistically significant difference in favor of the bupropion-treated group. However, this finding was confounded by the small effect size and difficulty quantifying somatic symptoms.40

Stimulants and modafinil. Psycho-stimulants have been shown to be efficacious for depression and fatigue, both as monotherapy and adjunctively.39,42

Modafinil has demonstrated efficacy in open-label trials for improving residual fatigue, but failed to separate from placebo in controlled trials.43 At least 1 other failed study has been published examining modafinil as a treatment for fatigue associated with depression.43

Adjunctive therapy with CNS stimulants, such as amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, has been used to treat fatigue, with positive results.16 Modafinil and stimulants also could be tried as an augmentation strategy to other antidepressants; such use is off-label and should be attempted only after careful consideration.16

Exercise might be a nonpharmacotherapeutic modality that targets the underlying physiology associated with fatigue. Exercise releases endorphins, which can affect overall brain chemistry and which have been theorized to diminish symptoms of fatigue and depression.44 Consider exercise in addition to treatment with an antidepressant in selected patients.45

To sum up

In general, the literature does not recommend one medication as superior to any other for treating fatigue that is a residual symptom of depression. Such hesitation suggests that more empirical studies are needed to determine what is the best and proper management of treating fatigue associated with depression.

Bottom LinE

Fatigue can be a symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) or a risk factor for depression. Fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD. Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health and can result in increased utilization of health care services. A number of treatment options are available; none has been shown to be superior to the others.

Related Resources

• Leone SS. A disabling combination: fatigue and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):86-87.

• Targum SD, Fava M. Fatigue as a residual symptom of depression. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):40-43.

• Illiades C. How to fight depression fatigue. Everyday Health. http://www.everydayhealth.com/health-report/major-depression-living-well/fight-depression-fatigue.aspx.

• Kerr M. Depression and fatigue: a vicious cycle. Healthline. http://www.healthline.com/health/depression/fatigue.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Desipramine • Norpramin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Modafinil • Provigil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Sohail reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Macaluso has conducted clinical trials research as principal investigator for the following pharmaceutical manufacturers in the past 12 months: AbbVie, Inc.; Alkermes; AssureRx Health, Inc.; Eisai Co., Ltd.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Naurex Inc. All clinical trial and study contracts were with, and payments were made to, University of Kansas Medical Center Research Institute, Kansas City, Kansas, a research institute affiliated with University of Kansas School of Medicine−Wichita.

Fatigue and depression can be viewed as a “vicious cycle”: Fatigue can be a symptom of major depression, and fatigue can be a risk factor for depression.1 For example, fatigue associated with a general medical condition or traumatic brain injury can be a risk factor for developing major depressive disorder (MDD).1-3 It isn’t surprising that fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD.

Despite the observed association between fatigue and depression, their underlying relationship often is unclear. The literature does not differentiate among fatigue associated with depression, fatigue as a treatment-emergent adverse effect, and fatigue as a residual symptom of depression that is partially responsive to treatment.4,5 To complicate the situation, many medications used to treat MDD can cause fatigue.

Patients often describe fatigue as (1) feeling tired, exhausted, or drained and (2) lacking energy and motivation. Fatigue can be related to impaired wakefulness but is believed to be a different entity than sleepiness.6 Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health.

We reviewed the literature about fatigue as a symptom of MDD by conducting a search of Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using keywords depression, fatigue, residual symptoms, and treatment. We chose the papers cited in this article based on our consensus and because these publications represent expert opinion or the highest quality evidence available.

Residual fatigue has an effect on prognosis

Fatigue is a common symptom of MDD that persists in 20% to 30% of patients whose symptoms of depression otherwise remit.4,7-9 Several studies have linked residual fatigue with the overall prognosis of MDD.5 Data from a prospective study demonstrate that depressed patients have a higher risk of relapse when they continue to report symptoms of fatigue after their symptoms of depression have otherwise entered partial remission.10 Another study demonstrated that the severity of residual symptoms of depression is a strong predictor of another major depressive episode.11