User login

Managing gynecologic cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic

To manage patients with gynecologic cancers, oncologists in the United States and Europe are recommending reducing outpatient visits, delaying surgeries, prolonging chemotherapy regimens, and generally trying to keep cancer patients away from those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

“We recognize that, in this special situation, we must continue to provide our gynecologic oncology patients with the highest quality of medical services,” Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and associates wrote in an editorial published in the International Journal of Gynecological Cancer.

At the same time, the authors added, the safety of patients, their families, and medical staff needs to be assured.

Dr. Ramirez and colleagues’ editorial includes recommendations on how to optimize the care of patients with gynecologic cancers while prioritizing safety and minimizing the burden to the healthcare system. The group’s recommendations outline when surgery, radiotherapy, and other treatments might be safely postponed and when they need to proceed out of urgency.

Some authors of the editorial also described their experiences with COVID-19 during a webinar on managing patients with advanced ovarian cancer, which was hosted by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO).

A lack of resources

In Spain, health resources “are collapsed” by the pandemic, editorial author Luis Chiva, MD, said during the webinar.

At his institution, the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, 98% of the 1,500 intensive care beds were occupied by COVID-19 patients at the end of March. So the hope was to be able to refer their patients to other communities where there may still be some capacity.

Another problem in Spain is the high percentage of health workers infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. More than 15,000 health workers were recently reported to be sick or self-isolating, which is around 14% of the health care workforce in the country.

Dr. Chiva noted that this puts those treating gynecologic cancers in a difficult position. On the one hand, surgery to remove a high-risk ovarian mass should not be delayed, but the majority of hospitals in Spain simply cannot perform this type of surgery during the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, due to this specific situation, almost, I would say in 80%-90% of hospitals, we are only able to carry out emergency surgical procedures,” Dr. Chiva said. That’s general emergency procedures such as appendectomies, removing blockages, and dealing with hemorrhages, not gynecologic surgeries. “It’s almost impossible to schedule the typical oncological cases,” he said.

Even with the Hospital IFEMA now set up at the Feria de Madrid, which is usually used to host large-scale events, there are “minimal options for performing standard oncological surgery,” Dr. Chiva said. He estimated that just 5% of hospitals in Spain are able to perform oncologic surgeries as normal, with maybe 15% able to offer surgery without the backup of postsurgical intensive care.

‘Ring-fencing’

“This is really an unusual time for us,” commented Jonathan Ledermann, MD, vice president of ESGO and a professor of medical oncology at University College London, who moderated the webinar.

“This is affecting the way in which we diagnose our patients and have access to care,” he said. “It compromises the way in which we treat patients. We have to adjust our treatment pathways. We have to look at the risks of coronavirus infection in cancer patients and how we manage patients in a socially distancing environment. We also need to think about managing gynecological oncology departments in the face of disease amongst staff, the risks of transmission, and the reduced clinical service.”

Dr. Ledermann noted that “ring-fencing” a few hospitals to deal only with patients free of COVID-19 might be a way forward. This approach has been used in Northern Italy and was recently started in London.

“We try to divide and have separate access between COVID-positive and -negative patients,” said Anna Fagotti, MD, an assistant professor at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome and another coauthor of the editorial.

“We are trying to divide the work flow of patients and try to ensure treatment to cancer patients as much as we can,” she explained. “This means that it’s a very difficult situation, and, every time, you have to deal with the number of places available as some places have been taken by other patients from the emergency room. We are still trying to have a number of beds and intensive care unit beds available for our patients.”

Setting up dedicated hospitals is a good idea, but it has to be done before the “tsunami” of cases hits and there are no more intensive care beds or ventilators, according to Antonio González-Martín, MD, of Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, another coauthor of the editorial.

Limiting hospital visits

Strategies to limit the number of times patients need to come into hospital for appointments and treatment is key to getting through the pandemic, Sandro Pignata, MD, of Instituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale in Naples, Italy, said during the webinar.

“It will be imperative to explore options that reduce the number of procedures or surgical interventions that may be associated with prolonged operative time, risk of major blood loss, necessitating blood products, risk of infection to the medical personnel, or admission to intensive care units,” Dr. Ramirez and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

“In considering management of disease, we must recognize that, in many centers, access to routine visits and surgery may be either completely restricted or significantly reduced. We must, therefore, consider options that may still offer our patients a treatment plan that addresses their disease while at the same time limiting risk of exposure,” the authors wrote.

The authors declared no competing interests or specific funding in relation to their work, and the webinar participants had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ramirez PT et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001419.

To manage patients with gynecologic cancers, oncologists in the United States and Europe are recommending reducing outpatient visits, delaying surgeries, prolonging chemotherapy regimens, and generally trying to keep cancer patients away from those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

“We recognize that, in this special situation, we must continue to provide our gynecologic oncology patients with the highest quality of medical services,” Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and associates wrote in an editorial published in the International Journal of Gynecological Cancer.

At the same time, the authors added, the safety of patients, their families, and medical staff needs to be assured.

Dr. Ramirez and colleagues’ editorial includes recommendations on how to optimize the care of patients with gynecologic cancers while prioritizing safety and minimizing the burden to the healthcare system. The group’s recommendations outline when surgery, radiotherapy, and other treatments might be safely postponed and when they need to proceed out of urgency.

Some authors of the editorial also described their experiences with COVID-19 during a webinar on managing patients with advanced ovarian cancer, which was hosted by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO).

A lack of resources

In Spain, health resources “are collapsed” by the pandemic, editorial author Luis Chiva, MD, said during the webinar.

At his institution, the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, 98% of the 1,500 intensive care beds were occupied by COVID-19 patients at the end of March. So the hope was to be able to refer their patients to other communities where there may still be some capacity.

Another problem in Spain is the high percentage of health workers infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. More than 15,000 health workers were recently reported to be sick or self-isolating, which is around 14% of the health care workforce in the country.

Dr. Chiva noted that this puts those treating gynecologic cancers in a difficult position. On the one hand, surgery to remove a high-risk ovarian mass should not be delayed, but the majority of hospitals in Spain simply cannot perform this type of surgery during the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, due to this specific situation, almost, I would say in 80%-90% of hospitals, we are only able to carry out emergency surgical procedures,” Dr. Chiva said. That’s general emergency procedures such as appendectomies, removing blockages, and dealing with hemorrhages, not gynecologic surgeries. “It’s almost impossible to schedule the typical oncological cases,” he said.

Even with the Hospital IFEMA now set up at the Feria de Madrid, which is usually used to host large-scale events, there are “minimal options for performing standard oncological surgery,” Dr. Chiva said. He estimated that just 5% of hospitals in Spain are able to perform oncologic surgeries as normal, with maybe 15% able to offer surgery without the backup of postsurgical intensive care.

‘Ring-fencing’

“This is really an unusual time for us,” commented Jonathan Ledermann, MD, vice president of ESGO and a professor of medical oncology at University College London, who moderated the webinar.

“This is affecting the way in which we diagnose our patients and have access to care,” he said. “It compromises the way in which we treat patients. We have to adjust our treatment pathways. We have to look at the risks of coronavirus infection in cancer patients and how we manage patients in a socially distancing environment. We also need to think about managing gynecological oncology departments in the face of disease amongst staff, the risks of transmission, and the reduced clinical service.”

Dr. Ledermann noted that “ring-fencing” a few hospitals to deal only with patients free of COVID-19 might be a way forward. This approach has been used in Northern Italy and was recently started in London.

“We try to divide and have separate access between COVID-positive and -negative patients,” said Anna Fagotti, MD, an assistant professor at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome and another coauthor of the editorial.

“We are trying to divide the work flow of patients and try to ensure treatment to cancer patients as much as we can,” she explained. “This means that it’s a very difficult situation, and, every time, you have to deal with the number of places available as some places have been taken by other patients from the emergency room. We are still trying to have a number of beds and intensive care unit beds available for our patients.”

Setting up dedicated hospitals is a good idea, but it has to be done before the “tsunami” of cases hits and there are no more intensive care beds or ventilators, according to Antonio González-Martín, MD, of Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, another coauthor of the editorial.

Limiting hospital visits

Strategies to limit the number of times patients need to come into hospital for appointments and treatment is key to getting through the pandemic, Sandro Pignata, MD, of Instituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale in Naples, Italy, said during the webinar.

“It will be imperative to explore options that reduce the number of procedures or surgical interventions that may be associated with prolonged operative time, risk of major blood loss, necessitating blood products, risk of infection to the medical personnel, or admission to intensive care units,” Dr. Ramirez and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

“In considering management of disease, we must recognize that, in many centers, access to routine visits and surgery may be either completely restricted or significantly reduced. We must, therefore, consider options that may still offer our patients a treatment plan that addresses their disease while at the same time limiting risk of exposure,” the authors wrote.

The authors declared no competing interests or specific funding in relation to their work, and the webinar participants had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ramirez PT et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001419.

To manage patients with gynecologic cancers, oncologists in the United States and Europe are recommending reducing outpatient visits, delaying surgeries, prolonging chemotherapy regimens, and generally trying to keep cancer patients away from those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

“We recognize that, in this special situation, we must continue to provide our gynecologic oncology patients with the highest quality of medical services,” Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and associates wrote in an editorial published in the International Journal of Gynecological Cancer.

At the same time, the authors added, the safety of patients, their families, and medical staff needs to be assured.

Dr. Ramirez and colleagues’ editorial includes recommendations on how to optimize the care of patients with gynecologic cancers while prioritizing safety and minimizing the burden to the healthcare system. The group’s recommendations outline when surgery, radiotherapy, and other treatments might be safely postponed and when they need to proceed out of urgency.

Some authors of the editorial also described their experiences with COVID-19 during a webinar on managing patients with advanced ovarian cancer, which was hosted by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO).

A lack of resources

In Spain, health resources “are collapsed” by the pandemic, editorial author Luis Chiva, MD, said during the webinar.

At his institution, the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, 98% of the 1,500 intensive care beds were occupied by COVID-19 patients at the end of March. So the hope was to be able to refer their patients to other communities where there may still be some capacity.

Another problem in Spain is the high percentage of health workers infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. More than 15,000 health workers were recently reported to be sick or self-isolating, which is around 14% of the health care workforce in the country.

Dr. Chiva noted that this puts those treating gynecologic cancers in a difficult position. On the one hand, surgery to remove a high-risk ovarian mass should not be delayed, but the majority of hospitals in Spain simply cannot perform this type of surgery during the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, due to this specific situation, almost, I would say in 80%-90% of hospitals, we are only able to carry out emergency surgical procedures,” Dr. Chiva said. That’s general emergency procedures such as appendectomies, removing blockages, and dealing with hemorrhages, not gynecologic surgeries. “It’s almost impossible to schedule the typical oncological cases,” he said.

Even with the Hospital IFEMA now set up at the Feria de Madrid, which is usually used to host large-scale events, there are “minimal options for performing standard oncological surgery,” Dr. Chiva said. He estimated that just 5% of hospitals in Spain are able to perform oncologic surgeries as normal, with maybe 15% able to offer surgery without the backup of postsurgical intensive care.

‘Ring-fencing’

“This is really an unusual time for us,” commented Jonathan Ledermann, MD, vice president of ESGO and a professor of medical oncology at University College London, who moderated the webinar.

“This is affecting the way in which we diagnose our patients and have access to care,” he said. “It compromises the way in which we treat patients. We have to adjust our treatment pathways. We have to look at the risks of coronavirus infection in cancer patients and how we manage patients in a socially distancing environment. We also need to think about managing gynecological oncology departments in the face of disease amongst staff, the risks of transmission, and the reduced clinical service.”

Dr. Ledermann noted that “ring-fencing” a few hospitals to deal only with patients free of COVID-19 might be a way forward. This approach has been used in Northern Italy and was recently started in London.

“We try to divide and have separate access between COVID-positive and -negative patients,” said Anna Fagotti, MD, an assistant professor at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome and another coauthor of the editorial.

“We are trying to divide the work flow of patients and try to ensure treatment to cancer patients as much as we can,” she explained. “This means that it’s a very difficult situation, and, every time, you have to deal with the number of places available as some places have been taken by other patients from the emergency room. We are still trying to have a number of beds and intensive care unit beds available for our patients.”

Setting up dedicated hospitals is a good idea, but it has to be done before the “tsunami” of cases hits and there are no more intensive care beds or ventilators, according to Antonio González-Martín, MD, of Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, another coauthor of the editorial.

Limiting hospital visits

Strategies to limit the number of times patients need to come into hospital for appointments and treatment is key to getting through the pandemic, Sandro Pignata, MD, of Instituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale in Naples, Italy, said during the webinar.

“It will be imperative to explore options that reduce the number of procedures or surgical interventions that may be associated with prolonged operative time, risk of major blood loss, necessitating blood products, risk of infection to the medical personnel, or admission to intensive care units,” Dr. Ramirez and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

“In considering management of disease, we must recognize that, in many centers, access to routine visits and surgery may be either completely restricted or significantly reduced. We must, therefore, consider options that may still offer our patients a treatment plan that addresses their disease while at the same time limiting risk of exposure,” the authors wrote.

The authors declared no competing interests or specific funding in relation to their work, and the webinar participants had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ramirez PT et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001419.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGICAL CANCER

Treating rectal cancer in the COVID-19 era: Expert guidance

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, minimizing risks of infection to patients with cancer while maintaining good outcomes remains a priority. An international panel of experts has now issued recommendations for treating patients with rectal cancer, which includes using a short pre-operative course of radiotherapy (SCRT) and then delaying surgery.

Using SCRT translates to fewer hospital appointments, which will keep patients safer and allow them to maintain social distancing. The panel also found that surgery can be safely delayed by up to 12 weeks, and thus will allow procedures to be rescheduled after the pandemic peaks.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is a global emergency and we needed to work very quickly to identify changes that would benefit patients,” said David Sebag-Montefiore, MD, a professor of clinical oncology at the University of Leeds and honorary clinical oncologist with the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, who led the 15 member panel. “Our recommendations were published 20 days after our first meeting.”

“This process normally takes many months, if not years,” he said in a statement.

The recommendations were published online April 2 in Radiotherapy and Oncology.

The panel used the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) rectal cancer guidelines as a framework to describe these new recommendations.

Recommendations by Stage

The recommendations were categorized into four subgroups based on cancer stage.

Early stage

- The ESMO guidelines recommend total mesorectal excision (TME) surgery without pre-operative radiotherapy for most cases.

- Panel recommendation also strongly supports the use of TME without pre-operative radiotherapy.

Intermediate stage

- The ESMO guidelines recommend TME alone or combined with SCRT or conventional radiotherapy (CRT) if there is uncertainty that a good quality mesorectal excision can be achieved.

- The panel strongly recommends TME alone in regions where high quality surgery is performed. The use of radiotherapy in this subgroup requires careful discussion, as the benefits of preoperative radiotherapy are likely to be small. If radiotherapy is used, then the preferred option should be SCRT.

Locally advanced

- The ESMO guideline recommends either pre-operative SCRT or CRT.

- The panel strongly recommends the use of SCRT and notes two phase 3 trials have compared SCRT and CRT and showed comparable outcomes for local recurrence, disease-free survival, overall survival, and late toxicity. In the COVID-19 setting, the panel points out that SCRT has many advantages over CRT, namely that there is less acute toxicity, fewer treatments which translate to less travel and contact with other patients and staff, and a significantly reduced risk of COVID-19 infection during treatment.

Timing of surgery after SCRT

- The ESMO guideline does not have any recommendations as they were issued before the Stockholm III trial (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:336-46).

- The panel notes that the use of SCRT and delaying surgery has advantages that can be beneficial in both routine clinical practice and the COVID-19 setting. Several clinical trials have recommended that surgery should be performed within 3-7 days of completing radiotherapy, but the Stockholm III trial reported no difference in outcomes when surgery was delayed. It compared surgery performed within 1 week versus 4-8 weeks following SCRT and there was no difference in any survival endpoints. In addition, a longer delay to surgery was associated with a reduction in post-operative and surgical morbidity although no differences in severe complications or re-operations.

Advanced subgroup

- The ESMO guidelines recommend the use of pre-operative CRT or SCRT followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. CRT should be given as a fluoropyrimidine (usually capecitabine) combined with radiotherapy of 45-50.4 Gy over 5-5.5 weeks. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered but there is wide international variation in its use.

- The panel recommends that two options be considered based on the current evidence. The first is pre-op CRT, which is the most established standard of care, with the duration of concurrent capecitabine chemotherapy limited to 5-5.5 weeks. The second option is SCRT with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In this case, the duration of radiotherapy is substantially less and has advantages versus CRT. “We consider both options to be acceptable but note the advantages of using SCRT in the COVID-19 setting,” the authors write. “The decision to use neoadjuvant chemotherapy in option 2 will reflect the attitudes to neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in each country, the assessment of the risk-benefit ratio, considering the risk factors for COVID-19 increased mortality, and the capacity and prioritization of chemotherapy delivery.”

Organ Preservation

Organ preservation is being increasingly considered when a complete clinical response is achieved after CRT or SCRT, the panel points out. “An organ preservation approach may be considered during the COVID-19 period providing that resources for an adequate surveillance including imaging and endoscopy are available to detect local failures that require salvage surgery,” they write.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, minimizing risks of infection to patients with cancer while maintaining good outcomes remains a priority. An international panel of experts has now issued recommendations for treating patients with rectal cancer, which includes using a short pre-operative course of radiotherapy (SCRT) and then delaying surgery.

Using SCRT translates to fewer hospital appointments, which will keep patients safer and allow them to maintain social distancing. The panel also found that surgery can be safely delayed by up to 12 weeks, and thus will allow procedures to be rescheduled after the pandemic peaks.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is a global emergency and we needed to work very quickly to identify changes that would benefit patients,” said David Sebag-Montefiore, MD, a professor of clinical oncology at the University of Leeds and honorary clinical oncologist with the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, who led the 15 member panel. “Our recommendations were published 20 days after our first meeting.”

“This process normally takes many months, if not years,” he said in a statement.

The recommendations were published online April 2 in Radiotherapy and Oncology.

The panel used the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) rectal cancer guidelines as a framework to describe these new recommendations.

Recommendations by Stage

The recommendations were categorized into four subgroups based on cancer stage.

Early stage

- The ESMO guidelines recommend total mesorectal excision (TME) surgery without pre-operative radiotherapy for most cases.

- Panel recommendation also strongly supports the use of TME without pre-operative radiotherapy.

Intermediate stage

- The ESMO guidelines recommend TME alone or combined with SCRT or conventional radiotherapy (CRT) if there is uncertainty that a good quality mesorectal excision can be achieved.

- The panel strongly recommends TME alone in regions where high quality surgery is performed. The use of radiotherapy in this subgroup requires careful discussion, as the benefits of preoperative radiotherapy are likely to be small. If radiotherapy is used, then the preferred option should be SCRT.

Locally advanced

- The ESMO guideline recommends either pre-operative SCRT or CRT.

- The panel strongly recommends the use of SCRT and notes two phase 3 trials have compared SCRT and CRT and showed comparable outcomes for local recurrence, disease-free survival, overall survival, and late toxicity. In the COVID-19 setting, the panel points out that SCRT has many advantages over CRT, namely that there is less acute toxicity, fewer treatments which translate to less travel and contact with other patients and staff, and a significantly reduced risk of COVID-19 infection during treatment.

Timing of surgery after SCRT

- The ESMO guideline does not have any recommendations as they were issued before the Stockholm III trial (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:336-46).

- The panel notes that the use of SCRT and delaying surgery has advantages that can be beneficial in both routine clinical practice and the COVID-19 setting. Several clinical trials have recommended that surgery should be performed within 3-7 days of completing radiotherapy, but the Stockholm III trial reported no difference in outcomes when surgery was delayed. It compared surgery performed within 1 week versus 4-8 weeks following SCRT and there was no difference in any survival endpoints. In addition, a longer delay to surgery was associated with a reduction in post-operative and surgical morbidity although no differences in severe complications or re-operations.

Advanced subgroup

- The ESMO guidelines recommend the use of pre-operative CRT or SCRT followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. CRT should be given as a fluoropyrimidine (usually capecitabine) combined with radiotherapy of 45-50.4 Gy over 5-5.5 weeks. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered but there is wide international variation in its use.

- The panel recommends that two options be considered based on the current evidence. The first is pre-op CRT, which is the most established standard of care, with the duration of concurrent capecitabine chemotherapy limited to 5-5.5 weeks. The second option is SCRT with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In this case, the duration of radiotherapy is substantially less and has advantages versus CRT. “We consider both options to be acceptable but note the advantages of using SCRT in the COVID-19 setting,” the authors write. “The decision to use neoadjuvant chemotherapy in option 2 will reflect the attitudes to neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in each country, the assessment of the risk-benefit ratio, considering the risk factors for COVID-19 increased mortality, and the capacity and prioritization of chemotherapy delivery.”

Organ Preservation

Organ preservation is being increasingly considered when a complete clinical response is achieved after CRT or SCRT, the panel points out. “An organ preservation approach may be considered during the COVID-19 period providing that resources for an adequate surveillance including imaging and endoscopy are available to detect local failures that require salvage surgery,” they write.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, minimizing risks of infection to patients with cancer while maintaining good outcomes remains a priority. An international panel of experts has now issued recommendations for treating patients with rectal cancer, which includes using a short pre-operative course of radiotherapy (SCRT) and then delaying surgery.

Using SCRT translates to fewer hospital appointments, which will keep patients safer and allow them to maintain social distancing. The panel also found that surgery can be safely delayed by up to 12 weeks, and thus will allow procedures to be rescheduled after the pandemic peaks.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is a global emergency and we needed to work very quickly to identify changes that would benefit patients,” said David Sebag-Montefiore, MD, a professor of clinical oncology at the University of Leeds and honorary clinical oncologist with the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, who led the 15 member panel. “Our recommendations were published 20 days after our first meeting.”

“This process normally takes many months, if not years,” he said in a statement.

The recommendations were published online April 2 in Radiotherapy and Oncology.

The panel used the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) rectal cancer guidelines as a framework to describe these new recommendations.

Recommendations by Stage

The recommendations were categorized into four subgroups based on cancer stage.

Early stage

- The ESMO guidelines recommend total mesorectal excision (TME) surgery without pre-operative radiotherapy for most cases.

- Panel recommendation also strongly supports the use of TME without pre-operative radiotherapy.

Intermediate stage

- The ESMO guidelines recommend TME alone or combined with SCRT or conventional radiotherapy (CRT) if there is uncertainty that a good quality mesorectal excision can be achieved.

- The panel strongly recommends TME alone in regions where high quality surgery is performed. The use of radiotherapy in this subgroup requires careful discussion, as the benefits of preoperative radiotherapy are likely to be small. If radiotherapy is used, then the preferred option should be SCRT.

Locally advanced

- The ESMO guideline recommends either pre-operative SCRT or CRT.

- The panel strongly recommends the use of SCRT and notes two phase 3 trials have compared SCRT and CRT and showed comparable outcomes for local recurrence, disease-free survival, overall survival, and late toxicity. In the COVID-19 setting, the panel points out that SCRT has many advantages over CRT, namely that there is less acute toxicity, fewer treatments which translate to less travel and contact with other patients and staff, and a significantly reduced risk of COVID-19 infection during treatment.

Timing of surgery after SCRT

- The ESMO guideline does not have any recommendations as they were issued before the Stockholm III trial (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:336-46).

- The panel notes that the use of SCRT and delaying surgery has advantages that can be beneficial in both routine clinical practice and the COVID-19 setting. Several clinical trials have recommended that surgery should be performed within 3-7 days of completing radiotherapy, but the Stockholm III trial reported no difference in outcomes when surgery was delayed. It compared surgery performed within 1 week versus 4-8 weeks following SCRT and there was no difference in any survival endpoints. In addition, a longer delay to surgery was associated with a reduction in post-operative and surgical morbidity although no differences in severe complications or re-operations.

Advanced subgroup

- The ESMO guidelines recommend the use of pre-operative CRT or SCRT followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. CRT should be given as a fluoropyrimidine (usually capecitabine) combined with radiotherapy of 45-50.4 Gy over 5-5.5 weeks. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered but there is wide international variation in its use.

- The panel recommends that two options be considered based on the current evidence. The first is pre-op CRT, which is the most established standard of care, with the duration of concurrent capecitabine chemotherapy limited to 5-5.5 weeks. The second option is SCRT with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In this case, the duration of radiotherapy is substantially less and has advantages versus CRT. “We consider both options to be acceptable but note the advantages of using SCRT in the COVID-19 setting,” the authors write. “The decision to use neoadjuvant chemotherapy in option 2 will reflect the attitudes to neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in each country, the assessment of the risk-benefit ratio, considering the risk factors for COVID-19 increased mortality, and the capacity and prioritization of chemotherapy delivery.”

Organ Preservation

Organ preservation is being increasingly considered when a complete clinical response is achieved after CRT or SCRT, the panel points out. “An organ preservation approach may be considered during the COVID-19 period providing that resources for an adequate surveillance including imaging and endoscopy are available to detect local failures that require salvage surgery,” they write.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When to treat, delay, or omit breast cancer therapy in the face of COVID-19

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

AGA CPU: Screening and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with NAFLD

Physicians should consider liver cancer screening for all patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and cirrhosis, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Screening “should be offered for patients with cirrhosis of varying etiologies when the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma is approximately at least 1.5% per year, as has been noted with NAFLD cirrhosis,” wrote Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates. Although patients with noncirrhotic NAFLD also can develop hepatocellular carcinoma, “[a]t this point, we believe that [the benefit of screening] is restricted to patients with compensated cirrhosis or those with decompensated cirrhosis listed for liver transplantation,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Liver cancer in NAFLD often goes undetected until it is advanced enough that patients are not candidates for curative therapy. Current guidelines provide limited recommendations on which patients with NAFLD to monitor for hepatocellular carcinoma, how best to do so, and how often. To fill this gap, Dr. Loomba and associates reviewed and cited 79 published papers and developed eight suggestions for clinical practice.

Patients with NAFLD and stage 0-2 fibrosis are at “extremely low” risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and should not be routinely screened, the practice update stated. Advanced fibrosis is a clear risk factor but can be challenging to detect in NAFLD – imaging is often insensitive, and screening biopsy tends to be infeasible. Hence, the experts suggest considering liver cancer screening if patients with NAFLD show evidence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis on at least two noninvasive tests of distinct modalities (that is, the two tests should not both be point-of-care, specialized blood tests or noninvasive imaging). To improve specificity, the recommended cut-point thresholds for cirrhosis are 16.1 kPa for vibration-controlled transient elastography and 5 kPa for magnetic resonance elastography.

Screening ultrasound accurately detects hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis who have a good acoustic window. However, ultrasound quality is operator dependent, and it can be difficult even for experienced users to detect mass lesions in overweight or obese patients. Thus, it is important always to document parenchymal heterogeneity, beam attenuation, and whether the entire liver was visualized. If ultrasound quality is inadequate, patients should be screened every 6 months with CT or MRI, with or without alpha-fetoprotein, according to the practice update.

The authors advised clinicians to counsel all patients with NAFLD and cirrhosis to avoid alcohol and tobacco. “Irrespective of NAFLD, the bulk of epidemiological data support alcohol drinking as a major risk for hepatocellular carcinoma,” they note. Likewise, pooled studies indicate that current smokers are at about 50%-85% greater risk of liver cancer than never smokers. The experts add that “[al]though specific data do not exist, we believe that e-cigarettes may turn out to be equally harmful and patients be counseled to abstain from those as well.”

They also recommended optimally managing dyslipidemia and diabetes among patients with NAFLD who are at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Statins are safe for patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia and may lower hepatocellular carcinoma risk, although more research is needed, according to the experts. For now, they support “the notion that the benefits of statin therapy among patients with dyslipidemia and NAFLD significantly outweigh the risk and should be utilized routinely.” Type 2 diabetes mellitus clearly heightens the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, which metformin appears to reduce among patients with NAFLD, cirrhosis, and type 2 diabetes. Glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists and some thiazolidinediones also appear to attenuate liver steatosis, inflammation, degeneration, and fibrosis, but it remains unclear if these effects ultimately lower cancer risk.

It is unclear if obesity directly contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with NAFLD, but obesity is an “important risk factor” for NAFLD itself, and “weight-loss interventions are strongly recommended to improve NAFLD-related outcomes,” the experts wrote. Pending further studies on whether weight loss reduces liver cancer risk in patients with NAFLD, they called for lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery or bariatric endoscopy procedures to optimally manage obesity in patients with NAFLD who are at risk for liver cancer.

The authors disclosed funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury. Dr. Loomba disclosed ties to Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Bird Rock Bio, Celgene, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, and a number of other companies. Two coauthors disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Genfit, Gilead, and Intercept. The remaining coauthor reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Loomba R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan 29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.053.

Physicians should consider liver cancer screening for all patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and cirrhosis, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Screening “should be offered for patients with cirrhosis of varying etiologies when the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma is approximately at least 1.5% per year, as has been noted with NAFLD cirrhosis,” wrote Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates. Although patients with noncirrhotic NAFLD also can develop hepatocellular carcinoma, “[a]t this point, we believe that [the benefit of screening] is restricted to patients with compensated cirrhosis or those with decompensated cirrhosis listed for liver transplantation,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Liver cancer in NAFLD often goes undetected until it is advanced enough that patients are not candidates for curative therapy. Current guidelines provide limited recommendations on which patients with NAFLD to monitor for hepatocellular carcinoma, how best to do so, and how often. To fill this gap, Dr. Loomba and associates reviewed and cited 79 published papers and developed eight suggestions for clinical practice.

Patients with NAFLD and stage 0-2 fibrosis are at “extremely low” risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and should not be routinely screened, the practice update stated. Advanced fibrosis is a clear risk factor but can be challenging to detect in NAFLD – imaging is often insensitive, and screening biopsy tends to be infeasible. Hence, the experts suggest considering liver cancer screening if patients with NAFLD show evidence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis on at least two noninvasive tests of distinct modalities (that is, the two tests should not both be point-of-care, specialized blood tests or noninvasive imaging). To improve specificity, the recommended cut-point thresholds for cirrhosis are 16.1 kPa for vibration-controlled transient elastography and 5 kPa for magnetic resonance elastography.

Screening ultrasound accurately detects hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis who have a good acoustic window. However, ultrasound quality is operator dependent, and it can be difficult even for experienced users to detect mass lesions in overweight or obese patients. Thus, it is important always to document parenchymal heterogeneity, beam attenuation, and whether the entire liver was visualized. If ultrasound quality is inadequate, patients should be screened every 6 months with CT or MRI, with or without alpha-fetoprotein, according to the practice update.

The authors advised clinicians to counsel all patients with NAFLD and cirrhosis to avoid alcohol and tobacco. “Irrespective of NAFLD, the bulk of epidemiological data support alcohol drinking as a major risk for hepatocellular carcinoma,” they note. Likewise, pooled studies indicate that current smokers are at about 50%-85% greater risk of liver cancer than never smokers. The experts add that “[al]though specific data do not exist, we believe that e-cigarettes may turn out to be equally harmful and patients be counseled to abstain from those as well.”

They also recommended optimally managing dyslipidemia and diabetes among patients with NAFLD who are at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Statins are safe for patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia and may lower hepatocellular carcinoma risk, although more research is needed, according to the experts. For now, they support “the notion that the benefits of statin therapy among patients with dyslipidemia and NAFLD significantly outweigh the risk and should be utilized routinely.” Type 2 diabetes mellitus clearly heightens the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, which metformin appears to reduce among patients with NAFLD, cirrhosis, and type 2 diabetes. Glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists and some thiazolidinediones also appear to attenuate liver steatosis, inflammation, degeneration, and fibrosis, but it remains unclear if these effects ultimately lower cancer risk.

It is unclear if obesity directly contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with NAFLD, but obesity is an “important risk factor” for NAFLD itself, and “weight-loss interventions are strongly recommended to improve NAFLD-related outcomes,” the experts wrote. Pending further studies on whether weight loss reduces liver cancer risk in patients with NAFLD, they called for lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery or bariatric endoscopy procedures to optimally manage obesity in patients with NAFLD who are at risk for liver cancer.

The authors disclosed funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury. Dr. Loomba disclosed ties to Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Bird Rock Bio, Celgene, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, and a number of other companies. Two coauthors disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Genfit, Gilead, and Intercept. The remaining coauthor reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Loomba R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan 29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.053.

Physicians should consider liver cancer screening for all patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and cirrhosis, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Screening “should be offered for patients with cirrhosis of varying etiologies when the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma is approximately at least 1.5% per year, as has been noted with NAFLD cirrhosis,” wrote Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates. Although patients with noncirrhotic NAFLD also can develop hepatocellular carcinoma, “[a]t this point, we believe that [the benefit of screening] is restricted to patients with compensated cirrhosis or those with decompensated cirrhosis listed for liver transplantation,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Liver cancer in NAFLD often goes undetected until it is advanced enough that patients are not candidates for curative therapy. Current guidelines provide limited recommendations on which patients with NAFLD to monitor for hepatocellular carcinoma, how best to do so, and how often. To fill this gap, Dr. Loomba and associates reviewed and cited 79 published papers and developed eight suggestions for clinical practice.

Patients with NAFLD and stage 0-2 fibrosis are at “extremely low” risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and should not be routinely screened, the practice update stated. Advanced fibrosis is a clear risk factor but can be challenging to detect in NAFLD – imaging is often insensitive, and screening biopsy tends to be infeasible. Hence, the experts suggest considering liver cancer screening if patients with NAFLD show evidence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis on at least two noninvasive tests of distinct modalities (that is, the two tests should not both be point-of-care, specialized blood tests or noninvasive imaging). To improve specificity, the recommended cut-point thresholds for cirrhosis are 16.1 kPa for vibration-controlled transient elastography and 5 kPa for magnetic resonance elastography.

Screening ultrasound accurately detects hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis who have a good acoustic window. However, ultrasound quality is operator dependent, and it can be difficult even for experienced users to detect mass lesions in overweight or obese patients. Thus, it is important always to document parenchymal heterogeneity, beam attenuation, and whether the entire liver was visualized. If ultrasound quality is inadequate, patients should be screened every 6 months with CT or MRI, with or without alpha-fetoprotein, according to the practice update.

The authors advised clinicians to counsel all patients with NAFLD and cirrhosis to avoid alcohol and tobacco. “Irrespective of NAFLD, the bulk of epidemiological data support alcohol drinking as a major risk for hepatocellular carcinoma,” they note. Likewise, pooled studies indicate that current smokers are at about 50%-85% greater risk of liver cancer than never smokers. The experts add that “[al]though specific data do not exist, we believe that e-cigarettes may turn out to be equally harmful and patients be counseled to abstain from those as well.”

They also recommended optimally managing dyslipidemia and diabetes among patients with NAFLD who are at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Statins are safe for patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia and may lower hepatocellular carcinoma risk, although more research is needed, according to the experts. For now, they support “the notion that the benefits of statin therapy among patients with dyslipidemia and NAFLD significantly outweigh the risk and should be utilized routinely.” Type 2 diabetes mellitus clearly heightens the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, which metformin appears to reduce among patients with NAFLD, cirrhosis, and type 2 diabetes. Glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists and some thiazolidinediones also appear to attenuate liver steatosis, inflammation, degeneration, and fibrosis, but it remains unclear if these effects ultimately lower cancer risk.

It is unclear if obesity directly contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with NAFLD, but obesity is an “important risk factor” for NAFLD itself, and “weight-loss interventions are strongly recommended to improve NAFLD-related outcomes,” the experts wrote. Pending further studies on whether weight loss reduces liver cancer risk in patients with NAFLD, they called for lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery or bariatric endoscopy procedures to optimally manage obesity in patients with NAFLD who are at risk for liver cancer.

The authors disclosed funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury. Dr. Loomba disclosed ties to Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Bird Rock Bio, Celgene, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, and a number of other companies. Two coauthors disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Genfit, Gilead, and Intercept. The remaining coauthor reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Loomba R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan 29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.053.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

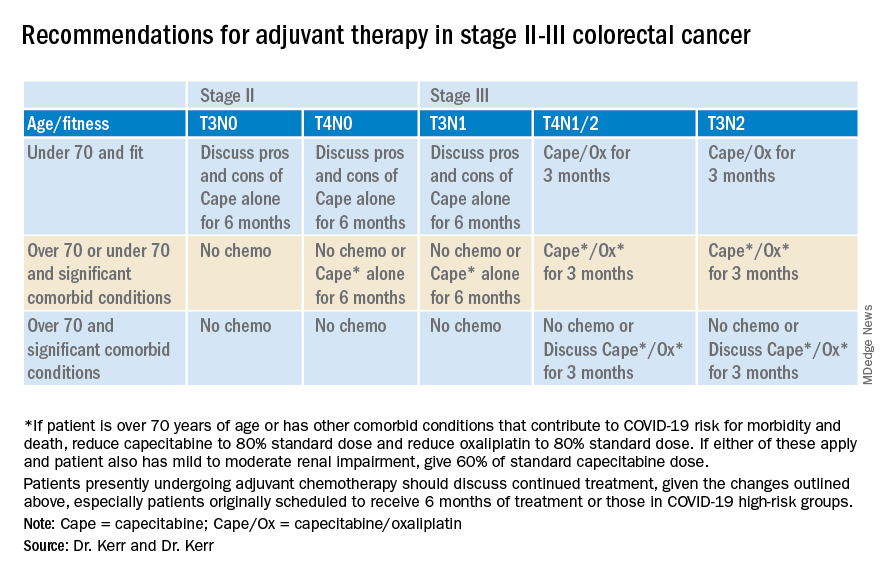

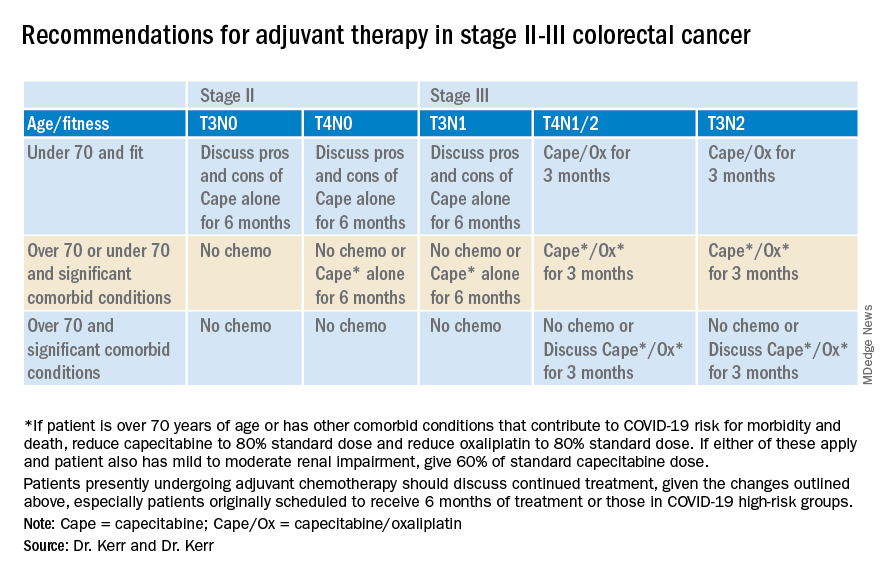

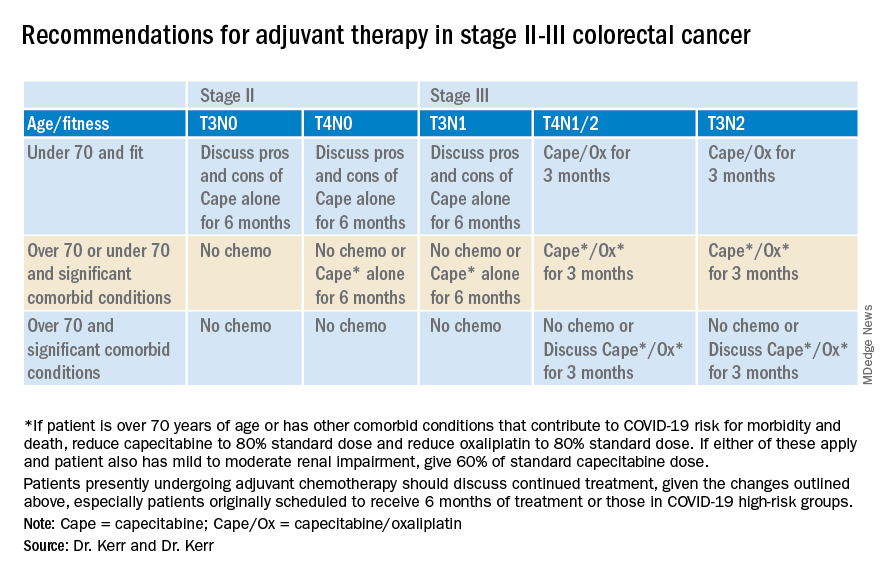

Colorectal cancer: Proposed treatment guidelines for the COVID-19 era

In light of the rapid changes affecting cancer clinics due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. David Kerr and Dr. Rachel Kerr, both specialists in gastrointestinal cancers at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, drafted these guidelines for the use of chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients. Dr. Kerr and Dr. Kerr are putting forth this guidance as a topic for discussion and debate.

Our aim in developing these recommendations for the care of colorectal cancer patients in areas affected by the COVID-19 outbreak is to reduce the comorbidity of chemotherapy and decrease the risk of patients dying from COVID-19, weighed against the potential benefits of receiving chemotherapy. These recommendations are also designed to reduce the burden on chemotherapy units during a time of great pressure.

We have modified the guidelines in such a way that, we believe, will decrease the total number of patients receiving chemotherapy – particularly in the adjuvant setting – and reduce the overall immune impact of chemotherapy on these patients. Specifically, we suggest changing doublet chemotherapy to single-agent chemotherapy for some groups; changing to combinations involving capecitabine rather than bolus and infusional 5-FU for other patients; and, finally, making reasonable dose reductions upfront to reduce the risk for cycle 1 complications.

By changing from push-and-pump 5-FU to capecitabine for the vast majority of patients, we will both reduce the rates of neutropenia and decrease throughput in chemotherapy outpatient units, reducing requirements for weekly line flushing, pump disconnections, and other routine maintenance.

We continue to recommend the use of ToxNav germline genetic testing as a genetic screen for DPYD/ENOSF1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to identify patients at high risk for fluoropyrimidine toxicity.

Use of biomarkers to sharpen prognosis should also be considered to refine therapeutic decisions.

Recommendations for stage II-III colorectal cancer

Recommendations for advanced colorectal cancer

Which regimen? Capecitabine/oxaliplatin should be the default backbone chemotherapy (rather than FOLFOX) in order to decrease the stress on infusion units.

Capecitabine plus irinotecan should be considered rather than FOLFIRI. However, in order to increase safety, reduce the dose of the capecitabine and the irinotecan, both to 80%, in all patient groups; and perhaps reduce the capecitabine dose further to 60% in those over the age of 70 or with significant comorbid conditions.

Treatment breaks. Full treatment breaks should be considered after 3 months of treatment in most patients with lower-volume, more indolent disease.

Treatment deintensification to capecitabine alone should be used in those with higher-volume disease (for example, more than 50% of liver replaced by tumor) at the beginning of treatment.

Deferring the start of any chemotherapy. Some older patients, or those with significant other comorbidities (that is, those who will be at increased risk for COVID-19 complications and death); who have low-volume disease, such as a couple of small lung metastases or a single liver metastasis; or who were diagnosed more than 12 months since adjuvant chemotherapy may decide to defer any chemotherapy for a period of time.

In these cases, we suggest rescanning at 3 months and discussing further treatment at that point. Some of these patients will be eligible for other interventions, such as resection, ablation, or stereotactic body radiation therapy. However, it will be important to consider the pressures on these other services during this unprecedented time.

Chemotherapy after resection of metastases. Given the lack of evidence and the present extenuating circumstances, we would not recommend any chemotherapy in this setting.

David J. Kerr, MD, CBE, MD, DSc, is a professor of cancer medicine at the University of Oxford. He is recognized internationally for his work in the research and treatment of colorectal cancer, and has founded three university spin-out companies: COBRA Therapeutics, Celleron Therapeutics, and Oxford Cancer Biomarkers. In 2002, he was appointed Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth. Rachel S. Kerr, MBChB, is a medical oncologist and associate professor of gastrointestinal oncology at the University of Oxford. She holds a UK Department of Health Fellowship, where she is clinical director of phase 3 trials in the oncology clinical trials office.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In light of the rapid changes affecting cancer clinics due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. David Kerr and Dr. Rachel Kerr, both specialists in gastrointestinal cancers at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, drafted these guidelines for the use of chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients. Dr. Kerr and Dr. Kerr are putting forth this guidance as a topic for discussion and debate.

Our aim in developing these recommendations for the care of colorectal cancer patients in areas affected by the COVID-19 outbreak is to reduce the comorbidity of chemotherapy and decrease the risk of patients dying from COVID-19, weighed against the potential benefits of receiving chemotherapy. These recommendations are also designed to reduce the burden on chemotherapy units during a time of great pressure.

We have modified the guidelines in such a way that, we believe, will decrease the total number of patients receiving chemotherapy – particularly in the adjuvant setting – and reduce the overall immune impact of chemotherapy on these patients. Specifically, we suggest changing doublet chemotherapy to single-agent chemotherapy for some groups; changing to combinations involving capecitabine rather than bolus and infusional 5-FU for other patients; and, finally, making reasonable dose reductions upfront to reduce the risk for cycle 1 complications.