User login

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

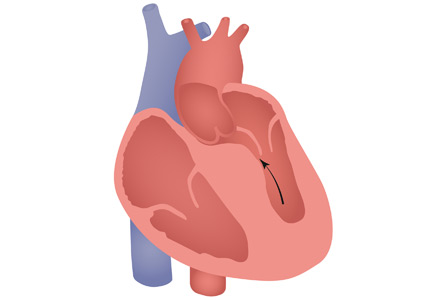

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

Postsurgical hypoparathyroidism is not primary hypoparathyroidism

To the Editor: I read with interest the case of a 67-year-old woman with bilateral hand numbness, published in the March 2018 issue of the Journal, and I would like to suggest 2 important corrections to this article.1

The authors present a case of hypocalcemia secondary to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism but describe it as due to primary hypoparathyroidism. The patient had undergone thyroidectomy 10 years earlier and since then had hypocalcemia, secondary to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism, that was treated with calcium and vitamin D, until she stopped taking these agents. Postsurgical hypothyroidism is the most common cause of acquired or secondary hypoparathyroidism and is not primary hypoparathyroidism. I strongly feel that this requires an update or correction to the article. This patient may have associated malabsorption, as the authors alluded to, as the cause of her “normal” serum parathyroid hormone level.

The patient also had hypomagnesemia, which the authors state could have been due to furosemide use and “uncontrolled” diabetes mellitus. Diabetes doesn’t need to be uncontrolled to cause hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia is common in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, with a prevalence of 14% to 48% in patients with diabetes compared with 2.5% to 15% in the general population.2 It is often multifactorial and may be secondary to one or more of the following factors: poor dietary intake, autonomic dysfunction, altered insulin resistance, glomerular hyperfiltration, osmotic diuresis (uncontrolled diabetes), recurrent metabolic acidosis, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and therapy with drugs such as metformin and sulfonylureas.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and hypomagnesemia often enter a vicious cycle in which hypomagnesemia worsens insulin resistance and insulin resistance, by reducing the activity of renal magnesium channel transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) type 6, perpetuates hypomagnesemia.3

- Radwan SS, Hamo KN, Zayed AA. A 67-year-old woman with bilateral hand numbness. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(3):200–208. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17026

- Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2(2):366–373. doi:10.2215/CJN.02960906

- Gommers LM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, de Baaij JH. Hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes: a vicious circle? Diabetes 2016; 65(1):3–13. doi:10.2337/db15-1028

To the Editor: I read with interest the case of a 67-year-old woman with bilateral hand numbness, published in the March 2018 issue of the Journal, and I would like to suggest 2 important corrections to this article.1

The authors present a case of hypocalcemia secondary to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism but describe it as due to primary hypoparathyroidism. The patient had undergone thyroidectomy 10 years earlier and since then had hypocalcemia, secondary to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism, that was treated with calcium and vitamin D, until she stopped taking these agents. Postsurgical hypothyroidism is the most common cause of acquired or secondary hypoparathyroidism and is not primary hypoparathyroidism. I strongly feel that this requires an update or correction to the article. This patient may have associated malabsorption, as the authors alluded to, as the cause of her “normal” serum parathyroid hormone level.

The patient also had hypomagnesemia, which the authors state could have been due to furosemide use and “uncontrolled” diabetes mellitus. Diabetes doesn’t need to be uncontrolled to cause hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia is common in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, with a prevalence of 14% to 48% in patients with diabetes compared with 2.5% to 15% in the general population.2 It is often multifactorial and may be secondary to one or more of the following factors: poor dietary intake, autonomic dysfunction, altered insulin resistance, glomerular hyperfiltration, osmotic diuresis (uncontrolled diabetes), recurrent metabolic acidosis, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and therapy with drugs such as metformin and sulfonylureas.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and hypomagnesemia often enter a vicious cycle in which hypomagnesemia worsens insulin resistance and insulin resistance, by reducing the activity of renal magnesium channel transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) type 6, perpetuates hypomagnesemia.3

To the Editor: I read with interest the case of a 67-year-old woman with bilateral hand numbness, published in the March 2018 issue of the Journal, and I would like to suggest 2 important corrections to this article.1

The authors present a case of hypocalcemia secondary to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism but describe it as due to primary hypoparathyroidism. The patient had undergone thyroidectomy 10 years earlier and since then had hypocalcemia, secondary to postsurgical hypoparathyroidism, that was treated with calcium and vitamin D, until she stopped taking these agents. Postsurgical hypothyroidism is the most common cause of acquired or secondary hypoparathyroidism and is not primary hypoparathyroidism. I strongly feel that this requires an update or correction to the article. This patient may have associated malabsorption, as the authors alluded to, as the cause of her “normal” serum parathyroid hormone level.

The patient also had hypomagnesemia, which the authors state could have been due to furosemide use and “uncontrolled” diabetes mellitus. Diabetes doesn’t need to be uncontrolled to cause hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia is common in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, with a prevalence of 14% to 48% in patients with diabetes compared with 2.5% to 15% in the general population.2 It is often multifactorial and may be secondary to one or more of the following factors: poor dietary intake, autonomic dysfunction, altered insulin resistance, glomerular hyperfiltration, osmotic diuresis (uncontrolled diabetes), recurrent metabolic acidosis, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and therapy with drugs such as metformin and sulfonylureas.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and hypomagnesemia often enter a vicious cycle in which hypomagnesemia worsens insulin resistance and insulin resistance, by reducing the activity of renal magnesium channel transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) type 6, perpetuates hypomagnesemia.3

- Radwan SS, Hamo KN, Zayed AA. A 67-year-old woman with bilateral hand numbness. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(3):200–208. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17026

- Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2(2):366–373. doi:10.2215/CJN.02960906

- Gommers LM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, de Baaij JH. Hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes: a vicious circle? Diabetes 2016; 65(1):3–13. doi:10.2337/db15-1028

- Radwan SS, Hamo KN, Zayed AA. A 67-year-old woman with bilateral hand numbness. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(3):200–208. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17026

- Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2(2):366–373. doi:10.2215/CJN.02960906

- Gommers LM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, de Baaij JH. Hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes: a vicious circle? Diabetes 2016; 65(1):3–13. doi:10.2337/db15-1028

In reply: Postsurgical hypoparathyroidism is not primary hypoparathyroidism

In Reply: We thank Dr. Parmar and appreciate his important comments.

Regarding the difference between primary and secondary hypoparathyroidism, the definition varies among investigators. Some define primary hypoparathyroidism as a condition characterized by primary absence or deficiency of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which results in hypocalcemia and which can be congenital or acquired, including postsurgical hypoparathyroidism.1–4 In principle, this is similar to the classification of disorders affecting other endocrine glands as primary and secondary. For example, primary hypothyroidism refers to a state of low thyroid hormones resulting from impairment or loss of function of the thyroid gland itself, such as in Hashimoto thyroiditis, radioactive iodine therapy, or thyroidectomy, among others.5 We adopted this definition in our article. In contrast, secondary hypoparathyroidism is characterized by low PTH secretion in response to certain conditions that cause hypercalcemia. Non-PTH-mediated hypercalcemia is a more common term used to describe this state of secondary hypoparathyroidism.

Other investigators restrict the term “primary hypoparathyroidism” to nonacquired (congenital or hereditary) etiologies, while applying the term “secondary hypoparathyroidism” to acquired etiologies.6

Concerning the association between diabetes mellitus and hypomagnesemia, we agree that diabetes does not need to be uncontrolled to cause hypomagnesemia. However, the patient described in our article presented with severe hypomagnesemia (serum level 0.6 mg/dL), which is not commonly associated with diabetes. Most cases of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are mild and asymptomatic, whereas severe manifestations including seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, and acute tetany are rarely encountered in clinical practice.7 Furthermore, numerous studies have shown a negative correlation between serum magnesium level and glycemic control.7–11 A recent study reported that plasma triglyceride and glucose levels are the main determinants of the plasma magnesium concentration in patients with type 2 diabetes.12

Our patient’s diabetes was uncontrolled, as evidenced by her hemoglobin A1c level of 9.7% and her random serum glucose level of 224 mg/dL. Therefore, it is more likely that “uncontrolled diabetes mellitus” (in addition to diuretic use) was the cause of her symptomatic severe hypomagnesemia rather than controlled diabetes mellitus.

- Mendes EM, Meireles-Brandão L, Meira C, Morais N, Ribeiro C, Guerra D. Primary hypoparathyroidism presenting as basal ganglia calcification secondary to extreme hypocalcemia. Clin Pract 2018; 8(1):1007. doi:10.4081/cp.2018.1007

- Vadiveloo T, Donnan PT, Leese GP. A population-based study of the epidemiology of chronic hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res 2018; 33(3):478-485. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3329

- Hendy GN, Cole DEC, Bastepe M. Hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet], South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2017. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279165. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- Rosa RG, Barros AJ, de Lima AR, et al. Mood disorder as a manifestation of primary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:326. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-326

- Almandoz JP, Gharib H. Hypothyroidism: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Med Clin North Am 2012; 96(2):203–221. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.005

- Fouda UM, Fouda RM, Ammar HM, Salem M, Darouti ME. Impetigo herpetiformis during the puerperium triggered by secondary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. Cases J 2009; 2:9338. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9338

- Tosiello L. Hypomagnesemia and diabetes mellitus. A review of clinical implications. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156(11):1143–1148. pmid: 8639008

- Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham PA, et al. Lower serum magnesium levels are associated with more rapid decline of renal function in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. Clin Nephrol 2005; 63(6):429–436. pmid:15960144

- Tong GM, Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency in critical illness. J Intensive Care Med 2005; 20(1):3–17. doi:10.1177/0885066604271539

- Resnick LM, Altura BT, Gupta RK, Laragh JH, Alderman MH, Altura BM. Intracellular and extracellular magnesium depletion in type 2 (non-insulin-independent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1993; 36(8):767–770. pmid:8405745

- Pun KK, Ho PW. Subclinical hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and hypomagnesemia in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1989; 7(3)163–167. pmid: 2605984

- Kurstjens S, de Baaij JH, Bouras H, Bindels RJ, Tack CJ, Hoenderop JG. Determinants of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol 2017; 176(1):11–19. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-0517

In Reply: We thank Dr. Parmar and appreciate his important comments.

Regarding the difference between primary and secondary hypoparathyroidism, the definition varies among investigators. Some define primary hypoparathyroidism as a condition characterized by primary absence or deficiency of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which results in hypocalcemia and which can be congenital or acquired, including postsurgical hypoparathyroidism.1–4 In principle, this is similar to the classification of disorders affecting other endocrine glands as primary and secondary. For example, primary hypothyroidism refers to a state of low thyroid hormones resulting from impairment or loss of function of the thyroid gland itself, such as in Hashimoto thyroiditis, radioactive iodine therapy, or thyroidectomy, among others.5 We adopted this definition in our article. In contrast, secondary hypoparathyroidism is characterized by low PTH secretion in response to certain conditions that cause hypercalcemia. Non-PTH-mediated hypercalcemia is a more common term used to describe this state of secondary hypoparathyroidism.

Other investigators restrict the term “primary hypoparathyroidism” to nonacquired (congenital or hereditary) etiologies, while applying the term “secondary hypoparathyroidism” to acquired etiologies.6

Concerning the association between diabetes mellitus and hypomagnesemia, we agree that diabetes does not need to be uncontrolled to cause hypomagnesemia. However, the patient described in our article presented with severe hypomagnesemia (serum level 0.6 mg/dL), which is not commonly associated with diabetes. Most cases of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are mild and asymptomatic, whereas severe manifestations including seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, and acute tetany are rarely encountered in clinical practice.7 Furthermore, numerous studies have shown a negative correlation between serum magnesium level and glycemic control.7–11 A recent study reported that plasma triglyceride and glucose levels are the main determinants of the plasma magnesium concentration in patients with type 2 diabetes.12

Our patient’s diabetes was uncontrolled, as evidenced by her hemoglobin A1c level of 9.7% and her random serum glucose level of 224 mg/dL. Therefore, it is more likely that “uncontrolled diabetes mellitus” (in addition to diuretic use) was the cause of her symptomatic severe hypomagnesemia rather than controlled diabetes mellitus.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Parmar and appreciate his important comments.

Regarding the difference between primary and secondary hypoparathyroidism, the definition varies among investigators. Some define primary hypoparathyroidism as a condition characterized by primary absence or deficiency of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which results in hypocalcemia and which can be congenital or acquired, including postsurgical hypoparathyroidism.1–4 In principle, this is similar to the classification of disorders affecting other endocrine glands as primary and secondary. For example, primary hypothyroidism refers to a state of low thyroid hormones resulting from impairment or loss of function of the thyroid gland itself, such as in Hashimoto thyroiditis, radioactive iodine therapy, or thyroidectomy, among others.5 We adopted this definition in our article. In contrast, secondary hypoparathyroidism is characterized by low PTH secretion in response to certain conditions that cause hypercalcemia. Non-PTH-mediated hypercalcemia is a more common term used to describe this state of secondary hypoparathyroidism.

Other investigators restrict the term “primary hypoparathyroidism” to nonacquired (congenital or hereditary) etiologies, while applying the term “secondary hypoparathyroidism” to acquired etiologies.6

Concerning the association between diabetes mellitus and hypomagnesemia, we agree that diabetes does not need to be uncontrolled to cause hypomagnesemia. However, the patient described in our article presented with severe hypomagnesemia (serum level 0.6 mg/dL), which is not commonly associated with diabetes. Most cases of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are mild and asymptomatic, whereas severe manifestations including seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, and acute tetany are rarely encountered in clinical practice.7 Furthermore, numerous studies have shown a negative correlation between serum magnesium level and glycemic control.7–11 A recent study reported that plasma triglyceride and glucose levels are the main determinants of the plasma magnesium concentration in patients with type 2 diabetes.12

Our patient’s diabetes was uncontrolled, as evidenced by her hemoglobin A1c level of 9.7% and her random serum glucose level of 224 mg/dL. Therefore, it is more likely that “uncontrolled diabetes mellitus” (in addition to diuretic use) was the cause of her symptomatic severe hypomagnesemia rather than controlled diabetes mellitus.

- Mendes EM, Meireles-Brandão L, Meira C, Morais N, Ribeiro C, Guerra D. Primary hypoparathyroidism presenting as basal ganglia calcification secondary to extreme hypocalcemia. Clin Pract 2018; 8(1):1007. doi:10.4081/cp.2018.1007

- Vadiveloo T, Donnan PT, Leese GP. A population-based study of the epidemiology of chronic hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res 2018; 33(3):478-485. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3329

- Hendy GN, Cole DEC, Bastepe M. Hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet], South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2017. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279165. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- Rosa RG, Barros AJ, de Lima AR, et al. Mood disorder as a manifestation of primary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:326. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-326

- Almandoz JP, Gharib H. Hypothyroidism: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Med Clin North Am 2012; 96(2):203–221. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.005

- Fouda UM, Fouda RM, Ammar HM, Salem M, Darouti ME. Impetigo herpetiformis during the puerperium triggered by secondary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. Cases J 2009; 2:9338. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9338

- Tosiello L. Hypomagnesemia and diabetes mellitus. A review of clinical implications. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156(11):1143–1148. pmid: 8639008

- Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham PA, et al. Lower serum magnesium levels are associated with more rapid decline of renal function in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. Clin Nephrol 2005; 63(6):429–436. pmid:15960144

- Tong GM, Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency in critical illness. J Intensive Care Med 2005; 20(1):3–17. doi:10.1177/0885066604271539

- Resnick LM, Altura BT, Gupta RK, Laragh JH, Alderman MH, Altura BM. Intracellular and extracellular magnesium depletion in type 2 (non-insulin-independent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1993; 36(8):767–770. pmid:8405745

- Pun KK, Ho PW. Subclinical hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and hypomagnesemia in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1989; 7(3)163–167. pmid: 2605984

- Kurstjens S, de Baaij JH, Bouras H, Bindels RJ, Tack CJ, Hoenderop JG. Determinants of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol 2017; 176(1):11–19. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-0517

- Mendes EM, Meireles-Brandão L, Meira C, Morais N, Ribeiro C, Guerra D. Primary hypoparathyroidism presenting as basal ganglia calcification secondary to extreme hypocalcemia. Clin Pract 2018; 8(1):1007. doi:10.4081/cp.2018.1007

- Vadiveloo T, Donnan PT, Leese GP. A population-based study of the epidemiology of chronic hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res 2018; 33(3):478-485. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3329

- Hendy GN, Cole DEC, Bastepe M. Hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet], South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2017. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279165. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- Rosa RG, Barros AJ, de Lima AR, et al. Mood disorder as a manifestation of primary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:326. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-326

- Almandoz JP, Gharib H. Hypothyroidism: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Med Clin North Am 2012; 96(2):203–221. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.005

- Fouda UM, Fouda RM, Ammar HM, Salem M, Darouti ME. Impetigo herpetiformis during the puerperium triggered by secondary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. Cases J 2009; 2:9338. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9338

- Tosiello L. Hypomagnesemia and diabetes mellitus. A review of clinical implications. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156(11):1143–1148. pmid: 8639008

- Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham PA, et al. Lower serum magnesium levels are associated with more rapid decline of renal function in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. Clin Nephrol 2005; 63(6):429–436. pmid:15960144

- Tong GM, Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency in critical illness. J Intensive Care Med 2005; 20(1):3–17. doi:10.1177/0885066604271539

- Resnick LM, Altura BT, Gupta RK, Laragh JH, Alderman MH, Altura BM. Intracellular and extracellular magnesium depletion in type 2 (non-insulin-independent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1993; 36(8):767–770. pmid:8405745

- Pun KK, Ho PW. Subclinical hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and hypomagnesemia in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1989; 7(3)163–167. pmid: 2605984

- Kurstjens S, de Baaij JH, Bouras H, Bindels RJ, Tack CJ, Hoenderop JG. Determinants of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol 2017; 176(1):11–19. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-0517

Reply to “In Reference to 'Improving the Safety of Opioid Use for Acute Noncancer Pain in Hospitalized Adults: A Consensus Statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine'”

Hall et al. draw attention to the important question of whether some patients may benefit from a naloxone prescription when discharged from the hospital with a short-term opioid prescription for acute pain. Although all members of the working group agreed that naloxone is appropriate in some cases, we were hesitant to recommend this as a standard practice for several reasons.

First, the intent of our Consensus Statement1 was to synthesize and summarize the areas of consensus in existing guidelines; none of the existing guidelines included in our systematic review make a recommendation for naloxone prescription in the setting of short-term opioid use for acute pain.2 We believe that this may relate to the fact that the risk factors for overdose and the threshold of risk above which naloxone would be beneficial have yet to be defined for this population and are likely to differ from those defined in patients using opioids chronically.

Additionally, if practitioners follow the recommendations to limit prescribing for acute pain to the minimum dose and duration of an opioid that was presumably administered in the hospital with an observed response, then the risk of overdose and the potential benefit of naloxone will decrease. Furthermore, emerging data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating noninferiority of nonopioid analgesics in the management of acute pain suggest that we should not so readily presume opioids to be the necessary or the best option.3-5 Data questioning the benefits of opioids over other safer therapies have particularly important implications for patients in whom the risks are felt to be high enough to warrant consideration of naloxone.

Disclosures

Dr. Herzig reports receiving compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Herzig is funded by a grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines.. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2979. PubMed

3. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. PubMed

4. Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12672 PubMed

5. Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3 PubMed

Hall et al. draw attention to the important question of whether some patients may benefit from a naloxone prescription when discharged from the hospital with a short-term opioid prescription for acute pain. Although all members of the working group agreed that naloxone is appropriate in some cases, we were hesitant to recommend this as a standard practice for several reasons.

First, the intent of our Consensus Statement1 was to synthesize and summarize the areas of consensus in existing guidelines; none of the existing guidelines included in our systematic review make a recommendation for naloxone prescription in the setting of short-term opioid use for acute pain.2 We believe that this may relate to the fact that the risk factors for overdose and the threshold of risk above which naloxone would be beneficial have yet to be defined for this population and are likely to differ from those defined in patients using opioids chronically.

Additionally, if practitioners follow the recommendations to limit prescribing for acute pain to the minimum dose and duration of an opioid that was presumably administered in the hospital with an observed response, then the risk of overdose and the potential benefit of naloxone will decrease. Furthermore, emerging data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating noninferiority of nonopioid analgesics in the management of acute pain suggest that we should not so readily presume opioids to be the necessary or the best option.3-5 Data questioning the benefits of opioids over other safer therapies have particularly important implications for patients in whom the risks are felt to be high enough to warrant consideration of naloxone.

Disclosures

Dr. Herzig reports receiving compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Herzig is funded by a grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

Hall et al. draw attention to the important question of whether some patients may benefit from a naloxone prescription when discharged from the hospital with a short-term opioid prescription for acute pain. Although all members of the working group agreed that naloxone is appropriate in some cases, we were hesitant to recommend this as a standard practice for several reasons.

First, the intent of our Consensus Statement1 was to synthesize and summarize the areas of consensus in existing guidelines; none of the existing guidelines included in our systematic review make a recommendation for naloxone prescription in the setting of short-term opioid use for acute pain.2 We believe that this may relate to the fact that the risk factors for overdose and the threshold of risk above which naloxone would be beneficial have yet to be defined for this population and are likely to differ from those defined in patients using opioids chronically.

Additionally, if practitioners follow the recommendations to limit prescribing for acute pain to the minimum dose and duration of an opioid that was presumably administered in the hospital with an observed response, then the risk of overdose and the potential benefit of naloxone will decrease. Furthermore, emerging data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating noninferiority of nonopioid analgesics in the management of acute pain suggest that we should not so readily presume opioids to be the necessary or the best option.3-5 Data questioning the benefits of opioids over other safer therapies have particularly important implications for patients in whom the risks are felt to be high enough to warrant consideration of naloxone.

Disclosures

Dr. Herzig reports receiving compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Herzig is funded by a grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines.. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2979. PubMed

3. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. PubMed

4. Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12672 PubMed

5. Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3 PubMed

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines.. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2979. PubMed

3. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. PubMed

4. Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12672 PubMed

5. Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3 PubMed

In Reference to “Improving the Safety of Opioid Use for Acute Noncancer Pain in Hospitalized Adults: A Consensus Statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine”

We read with great interest the consensus statement on improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain by Herzig et al.1 We strongly support the recommendations outlined in the document.

However, we would like to advocate for an additional recommendation that was considered but not included by the authors. Given the proven benefit—with minimal risk—in providing naloxone to patients and family members, we encourage naloxone prescriptions at discharge for all patients at risk for opioid overdose independent of therapy duration.2 Even opioid-naive patients who are prescribed opioids at hospital discharge have a significantly higher risk for chronic opioid use.3

We support extrapolating recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to prescribe naloxone to all patients at discharge who are at risk for an opioid overdose, including those with a history of overdose or substance use disorder as well as those receiving a prescription of ≥50 mg morphine equivalents per day or who use opioids and benzodiazepines.4,5

Given the current barriers to healthcare access, prescribing naloxone at discharge may be a rare opportunity to provide a potential life-saving intervention to prevent a fatal opioid overdose.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4);263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 2016;111(7):1177-1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. PubMed

3. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. PubMed

4. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. PubMed

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63, Full Document. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18- 5063FULLDOC. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA18-5063FULLDOC/SMA18-5063FULLDOC.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2018.

We read with great interest the consensus statement on improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain by Herzig et al.1 We strongly support the recommendations outlined in the document.

However, we would like to advocate for an additional recommendation that was considered but not included by the authors. Given the proven benefit—with minimal risk—in providing naloxone to patients and family members, we encourage naloxone prescriptions at discharge for all patients at risk for opioid overdose independent of therapy duration.2 Even opioid-naive patients who are prescribed opioids at hospital discharge have a significantly higher risk for chronic opioid use.3

We support extrapolating recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to prescribe naloxone to all patients at discharge who are at risk for an opioid overdose, including those with a history of overdose or substance use disorder as well as those receiving a prescription of ≥50 mg morphine equivalents per day or who use opioids and benzodiazepines.4,5

Given the current barriers to healthcare access, prescribing naloxone at discharge may be a rare opportunity to provide a potential life-saving intervention to prevent a fatal opioid overdose.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

We read with great interest the consensus statement on improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain by Herzig et al.1 We strongly support the recommendations outlined in the document.

However, we would like to advocate for an additional recommendation that was considered but not included by the authors. Given the proven benefit—with minimal risk—in providing naloxone to patients and family members, we encourage naloxone prescriptions at discharge for all patients at risk for opioid overdose independent of therapy duration.2 Even opioid-naive patients who are prescribed opioids at hospital discharge have a significantly higher risk for chronic opioid use.3

We support extrapolating recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to prescribe naloxone to all patients at discharge who are at risk for an opioid overdose, including those with a history of overdose or substance use disorder as well as those receiving a prescription of ≥50 mg morphine equivalents per day or who use opioids and benzodiazepines.4,5

Given the current barriers to healthcare access, prescribing naloxone at discharge may be a rare opportunity to provide a potential life-saving intervention to prevent a fatal opioid overdose.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4);263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 2016;111(7):1177-1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. PubMed

3. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. PubMed

4. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. PubMed

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63, Full Document. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18- 5063FULLDOC. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA18-5063FULLDOC/SMA18-5063FULLDOC.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2018.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4);263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 2016;111(7):1177-1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. PubMed

3. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. PubMed

4. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. PubMed

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63, Full Document. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18- 5063FULLDOC. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA18-5063FULLDOC/SMA18-5063FULLDOC.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2018.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Aortic aneurysm: Fluoroquinolones, genetic counseling

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Cikach et al on thoracic aortic aneurysm.1 For medical management of this condition, the authors emphasized controlling blood pressure and heart rate and also avoiding isometric exercises and heavy lifting. In addition to their recommendations, we believe there is plausible evidence to advise caution if fluoroquinolone antibiotics are used in this setting.

Three large population-based studies, from Canada,2 Taiwan,3 and Sweden,4 collectively demonstrated a significant 2-fold increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection presenting within 60 days of fluoroquinolone use compared with other antibiotic exposure. Moreover, a longer duration of fluoroquinolone use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection.3

Mechanistically, fluoroquinolones have been shown to up-regulate production of several matrix metalloproteinases, including metalloproteinase 2, leading to degradation of type I collagen.2,5 Type I and type III are the dominant collagens in the aortic wall, and collagen degradation is implicated in aortic aneurysm formation and expansion.

Fluoroquinolones are widely prescribed in both outpatient and inpatient settings and are sometimes used for long durations in the geriatric population.2 It is possible that these drugs have a propensity to increase aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection in older patients who already have aortic aneurysm. Accordingly, this might make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable for using these drugs in these situations, and other antibiotics should be used, if indicated.

Furthermore, if fluoroquinolones are used in patients with aortic aneurysm, perhaps imaging studies of the aneurysm should be done more frequently than once a year to detect accelerated aneurysm growth. Finally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of increased aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection with fluoroquinolone use.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e010077. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077

- Lee C-C, Lee MG, Chen Y-S, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1839–1847. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389

- Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2018; 360:k678. doi:10.1136/bmj.k678

- Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(1):67–73. doi:10.1002/jor.21196

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Cikach et al on thoracic aortic aneurysm.1 For medical management of this condition, the authors emphasized controlling blood pressure and heart rate and also avoiding isometric exercises and heavy lifting. In addition to their recommendations, we believe there is plausible evidence to advise caution if fluoroquinolone antibiotics are used in this setting.

Three large population-based studies, from Canada,2 Taiwan,3 and Sweden,4 collectively demonstrated a significant 2-fold increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection presenting within 60 days of fluoroquinolone use compared with other antibiotic exposure. Moreover, a longer duration of fluoroquinolone use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection.3

Mechanistically, fluoroquinolones have been shown to up-regulate production of several matrix metalloproteinases, including metalloproteinase 2, leading to degradation of type I collagen.2,5 Type I and type III are the dominant collagens in the aortic wall, and collagen degradation is implicated in aortic aneurysm formation and expansion.

Fluoroquinolones are widely prescribed in both outpatient and inpatient settings and are sometimes used for long durations in the geriatric population.2 It is possible that these drugs have a propensity to increase aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection in older patients who already have aortic aneurysm. Accordingly, this might make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable for using these drugs in these situations, and other antibiotics should be used, if indicated.

Furthermore, if fluoroquinolones are used in patients with aortic aneurysm, perhaps imaging studies of the aneurysm should be done more frequently than once a year to detect accelerated aneurysm growth. Finally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of increased aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection with fluoroquinolone use.

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Cikach et al on thoracic aortic aneurysm.1 For medical management of this condition, the authors emphasized controlling blood pressure and heart rate and also avoiding isometric exercises and heavy lifting. In addition to their recommendations, we believe there is plausible evidence to advise caution if fluoroquinolone antibiotics are used in this setting.

Three large population-based studies, from Canada,2 Taiwan,3 and Sweden,4 collectively demonstrated a significant 2-fold increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection presenting within 60 days of fluoroquinolone use compared with other antibiotic exposure. Moreover, a longer duration of fluoroquinolone use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection.3

Mechanistically, fluoroquinolones have been shown to up-regulate production of several matrix metalloproteinases, including metalloproteinase 2, leading to degradation of type I collagen.2,5 Type I and type III are the dominant collagens in the aortic wall, and collagen degradation is implicated in aortic aneurysm formation and expansion.

Fluoroquinolones are widely prescribed in both outpatient and inpatient settings and are sometimes used for long durations in the geriatric population.2 It is possible that these drugs have a propensity to increase aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection in older patients who already have aortic aneurysm. Accordingly, this might make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable for using these drugs in these situations, and other antibiotics should be used, if indicated.

Furthermore, if fluoroquinolones are used in patients with aortic aneurysm, perhaps imaging studies of the aneurysm should be done more frequently than once a year to detect accelerated aneurysm growth. Finally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of increased aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection with fluoroquinolone use.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e010077. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077

- Lee C-C, Lee MG, Chen Y-S, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1839–1847. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389

- Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2018; 360:k678. doi:10.1136/bmj.k678

- Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(1):67–73. doi:10.1002/jor.21196

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e010077. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077

- Lee C-C, Lee MG, Chen Y-S, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1839–1847. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389

- Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2018; 360:k678. doi:10.1136/bmj.k678

- Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(1):67–73. doi:10.1002/jor.21196

Aortic aneurysm: Fluoroquinolones, genetic counseling

To the Editor: The review of thoracic aortic aneurysm by Cikach et al1 was excellent. However, we noted that referral for clinical genetic counseling and testing is suggested only if 1 or more first-degree relatives have aneurysmal disease.

Absence of a family history does not rule out syndromic aortopathy, which can occur de novo. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of syndromic aortopathy can be made on the basis of physical features that can be very subtle, such as pectus deformities, scoliosis, dolichostenomelia, joint hypermobility or contractures, craniofacial features, or skin fragility.2

Genetic counseling is paramount even if molecular testing is negative or inconclusive, which can occur in more than 50% of patients referred.3 Clinical genetic evaluation would also facilitate testing for other family members who may be affected, and would help to coordinate care for nonvascular conditions that may be associated with the syndrome.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. OMIM. Online mendelian inheritance in man. https://omim.org. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Mazine A, Moryousef-Abitbol JH, Faghfoury H, Meza JM, Morel C, Ouzounian M. Yield of genetic testing in patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(11):2005. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)35394-9

To the Editor: The review of thoracic aortic aneurysm by Cikach et al1 was excellent. However, we noted that referral for clinical genetic counseling and testing is suggested only if 1 or more first-degree relatives have aneurysmal disease.

Absence of a family history does not rule out syndromic aortopathy, which can occur de novo. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of syndromic aortopathy can be made on the basis of physical features that can be very subtle, such as pectus deformities, scoliosis, dolichostenomelia, joint hypermobility or contractures, craniofacial features, or skin fragility.2

Genetic counseling is paramount even if molecular testing is negative or inconclusive, which can occur in more than 50% of patients referred.3 Clinical genetic evaluation would also facilitate testing for other family members who may be affected, and would help to coordinate care for nonvascular conditions that may be associated with the syndrome.

To the Editor: The review of thoracic aortic aneurysm by Cikach et al1 was excellent. However, we noted that referral for clinical genetic counseling and testing is suggested only if 1 or more first-degree relatives have aneurysmal disease.

Absence of a family history does not rule out syndromic aortopathy, which can occur de novo. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of syndromic aortopathy can be made on the basis of physical features that can be very subtle, such as pectus deformities, scoliosis, dolichostenomelia, joint hypermobility or contractures, craniofacial features, or skin fragility.2

Genetic counseling is paramount even if molecular testing is negative or inconclusive, which can occur in more than 50% of patients referred.3 Clinical genetic evaluation would also facilitate testing for other family members who may be affected, and would help to coordinate care for nonvascular conditions that may be associated with the syndrome.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. OMIM. Online mendelian inheritance in man. https://omim.org. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Mazine A, Moryousef-Abitbol JH, Faghfoury H, Meza JM, Morel C, Ouzounian M. Yield of genetic testing in patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(11):2005. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)35394-9

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. OMIM. Online mendelian inheritance in man. https://omim.org. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Mazine A, Moryousef-Abitbol JH, Faghfoury H, Meza JM, Morel C, Ouzounian M. Yield of genetic testing in patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(11):2005. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)35394-9

In reply: Aortic aneurysm: Fluoroquinolones, genetic counseling

In Reply: We thank Drs. Goldstein and Mascitelli for their comments regarding fluoroquinolones and thoracic aortic aneurysms. We acknowledge that fluoroquinolones (particularly ciprofloxacin) have been associated with a risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection based on large observational studies from Taiwan, Canada, and Sweden. Although all of the studies have shown an association between ciprofloxacin and aortic aneurysm, the causative role is not well established. In addition, the numbers of events were very small in these large cohorts of patients. In our large tertiary care practice at Cleveland Clinic, we have very few patients with aortic aneurysm or dissection who have used fluoroquinolones.

We recognize the association; however, our paper was intended to emphasize the more common causes and treatment options that primary care physicians are likely to encounter in routine practice.

We also thank Drs. Ayoubieh and MacCarrick for their comments about genetic counseling. We agree that genetic counseling is important, as is a detailed physical examination for subtle features of genetically mediated aortic aneurysm. In fact, we incorporate the physical examination when patients are seen at our aortic center so as to recognize the physical features. We do routinely recommend screening of first-degree relatives even without significant family history on an individual basis and make appropriate referrals for other conditions that can be seen in these patients. Our article, however, is primarily intended to emphasize the importance of referring these patients for more-focused care at a specialized center, where we incorporate all of the suggestions that were made.

In Reply: We thank Drs. Goldstein and Mascitelli for their comments regarding fluoroquinolones and thoracic aortic aneurysms. We acknowledge that fluoroquinolones (particularly ciprofloxacin) have been associated with a risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection based on large observational studies from Taiwan, Canada, and Sweden. Although all of the studies have shown an association between ciprofloxacin and aortic aneurysm, the causative role is not well established. In addition, the numbers of events were very small in these large cohorts of patients. In our large tertiary care practice at Cleveland Clinic, we have very few patients with aortic aneurysm or dissection who have used fluoroquinolones.

We recognize the association; however, our paper was intended to emphasize the more common causes and treatment options that primary care physicians are likely to encounter in routine practice.

We also thank Drs. Ayoubieh and MacCarrick for their comments about genetic counseling. We agree that genetic counseling is important, as is a detailed physical examination for subtle features of genetically mediated aortic aneurysm. In fact, we incorporate the physical examination when patients are seen at our aortic center so as to recognize the physical features. We do routinely recommend screening of first-degree relatives even without significant family history on an individual basis and make appropriate referrals for other conditions that can be seen in these patients. Our article, however, is primarily intended to emphasize the importance of referring these patients for more-focused care at a specialized center, where we incorporate all of the suggestions that were made.

In Reply: We thank Drs. Goldstein and Mascitelli for their comments regarding fluoroquinolones and thoracic aortic aneurysms. We acknowledge that fluoroquinolones (particularly ciprofloxacin) have been associated with a risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection based on large observational studies from Taiwan, Canada, and Sweden. Although all of the studies have shown an association between ciprofloxacin and aortic aneurysm, the causative role is not well established. In addition, the numbers of events were very small in these large cohorts of patients. In our large tertiary care practice at Cleveland Clinic, we have very few patients with aortic aneurysm or dissection who have used fluoroquinolones.

We recognize the association; however, our paper was intended to emphasize the more common causes and treatment options that primary care physicians are likely to encounter in routine practice.

We also thank Drs. Ayoubieh and MacCarrick for their comments about genetic counseling. We agree that genetic counseling is important, as is a detailed physical examination for subtle features of genetically mediated aortic aneurysm. In fact, we incorporate the physical examination when patients are seen at our aortic center so as to recognize the physical features. We do routinely recommend screening of first-degree relatives even without significant family history on an individual basis and make appropriate referrals for other conditions that can be seen in these patients. Our article, however, is primarily intended to emphasize the importance of referring these patients for more-focused care at a specialized center, where we incorporate all of the suggestions that were made.