User login

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

The veteran population, with its unique and diverse types of exposure and military service experiences, faces distinct health factors compared with the general population. These factors can be categorized into exposures during military service and those occurring postservice. While the latter phase incorporates psychological issues that may arise while transitioning to civilian life, the service period is associated with major physical, chemical, and psychological exposures that can impact veterans’ health. Carcinogenesis related to military exposures is concerning, and different types of malignancies have been associated with military exposures.1 The 2022 introduction of the Cancer Moonshot initiative served as a breeding ground for multiple projects aimed at investigation of exposure-related carcinogenesis, prompting increased attention and efforts to linking specific exposures to specific malignancies.2

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer, accounting for 1.3% of all cancer deaths.3 Although it may only account for 1% to 5% of skin cancer diagnoses, its incidence in the United States’ population has been increasing.4,5 There were 97,610 estimated new cases of melanoma in 2023, according to the National Cancer Institute.6

The incidence of melanoma may be higher in the military population compared with the general population.7 Melanoma is the fourth-most common cancer diagnosed in veterans.8

Several demographic characteristics of the US military population are associated with higher melanoma incidence and poorer prognosis, including male sex, older age, and White race. Apart from sun exposure—a known risk factor for melanoma development—other factors, such as service branch, seem to contribute to risk, with the highest melanoma rates noted in the Air Force.9 According to a study by Chang et al, veterans have a higher risk of stage III (18%) or stage IV (13%) melanoma at initial diagnosis.8

Molecular testing of metastatic melanoma is currently the standard of care for guiding the use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies such as BRAF, MEK, and KIT inhibitors. This comparative analysis details the melanoma comprehensive genomic profiles observed at a large US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC) and those reported in reference databases.

Methods

A query to select all metastatic melanomas sent for comprehensive genomic profiling from the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), identified 35 cases from 2019 through 2023 as the study population. The health records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic information, military service history, melanoma history, other medical, social, and family histories. The comprehensive genomic profiling reports were reviewed to collect the reported pathogenic variants, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) for each case.

The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used to identify the most commonly mutated genes in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for the general population.4,5 The literature was consulted to determine the MSI status and TMB in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for separate reference populations.6,7 The frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) status, TMB ≥ 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb), and mutations in each of the 20 most commonly mutated genes was determined and compared between melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas and KCVAMC cases. Corresponding P values were calculated to identify significant differences. Values were calculated for the entire sample as well as a subgroup with Agent Orange (AO) exposure. The study was approved by the KCVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

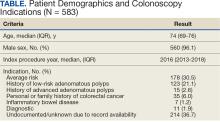

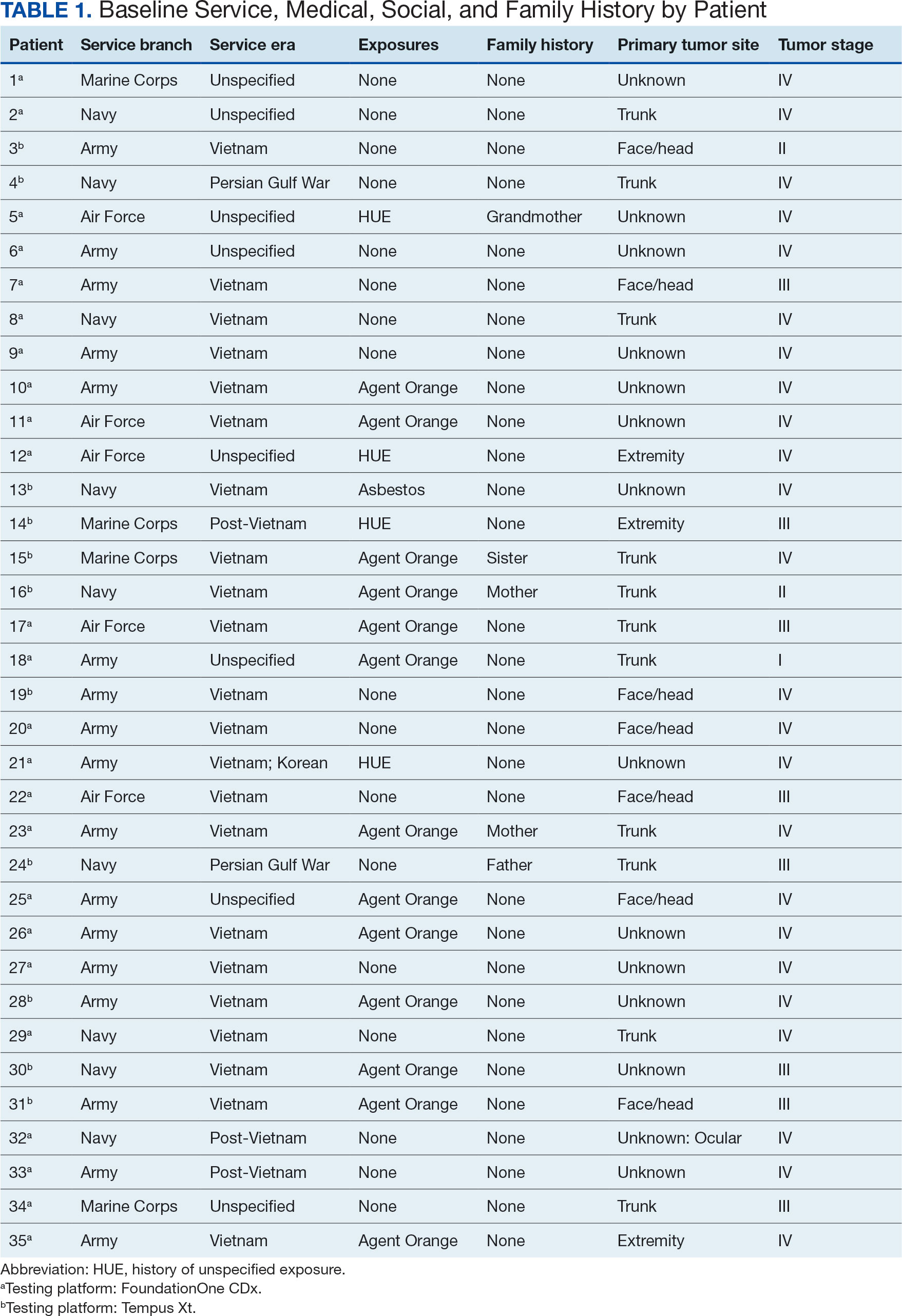

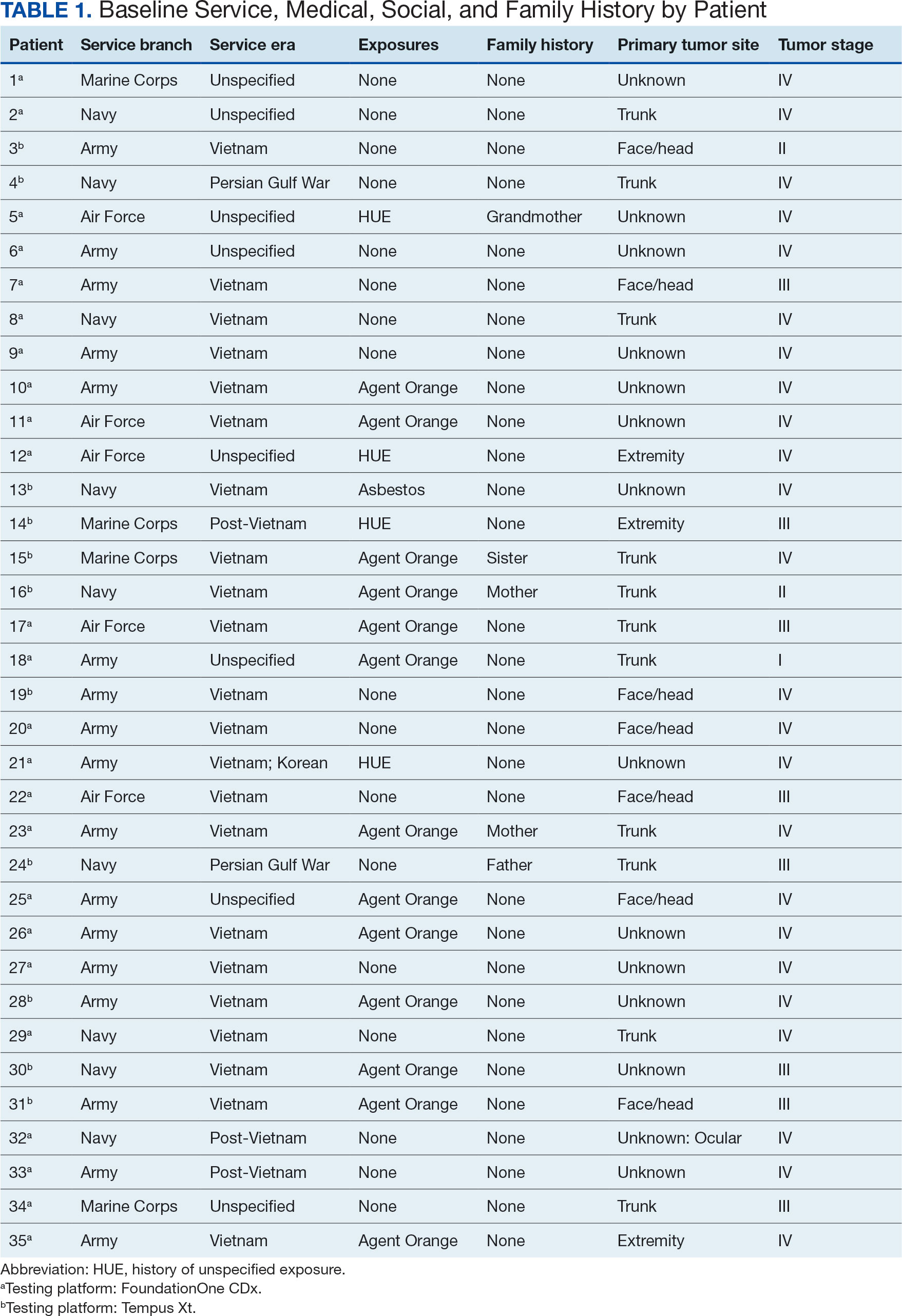

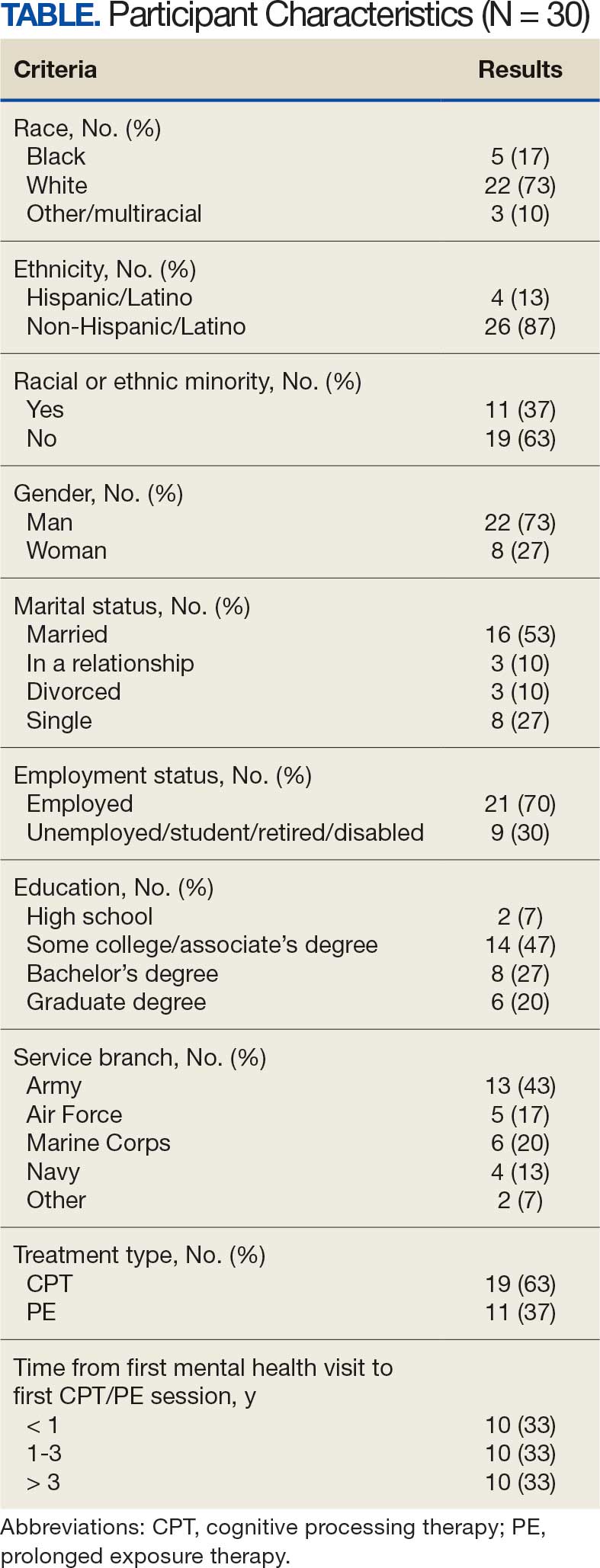

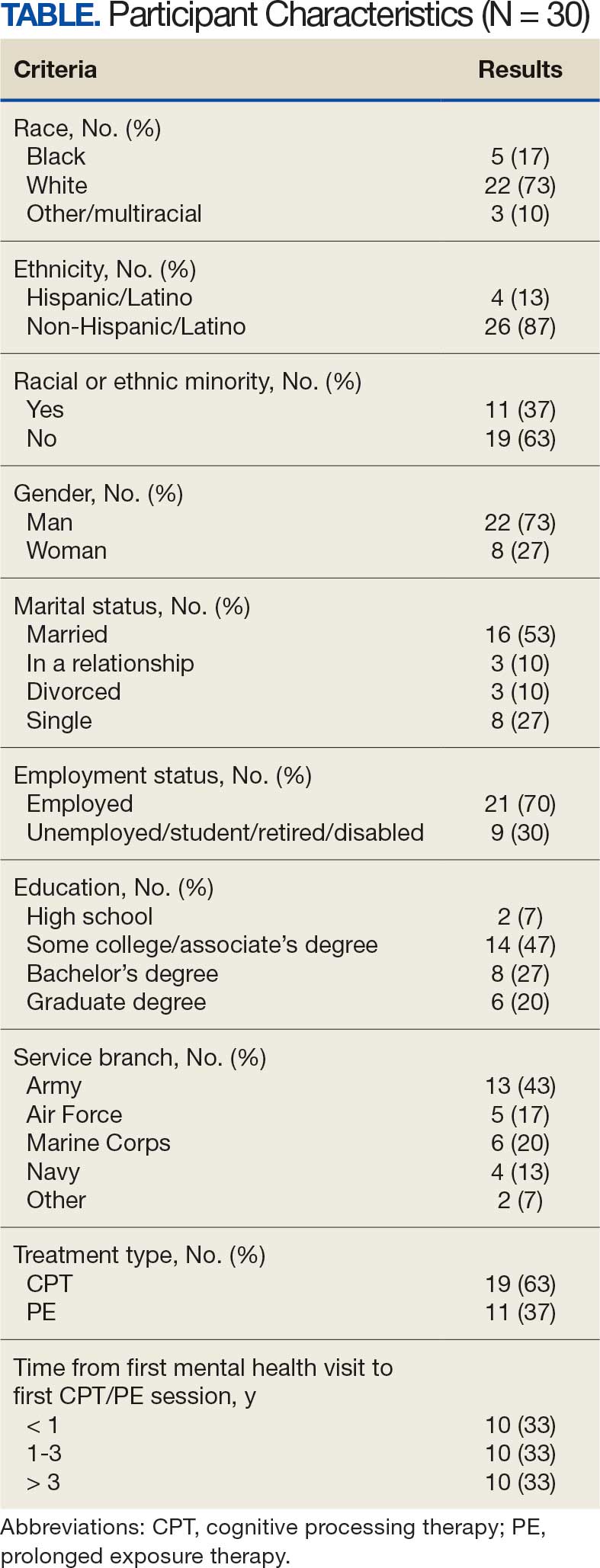

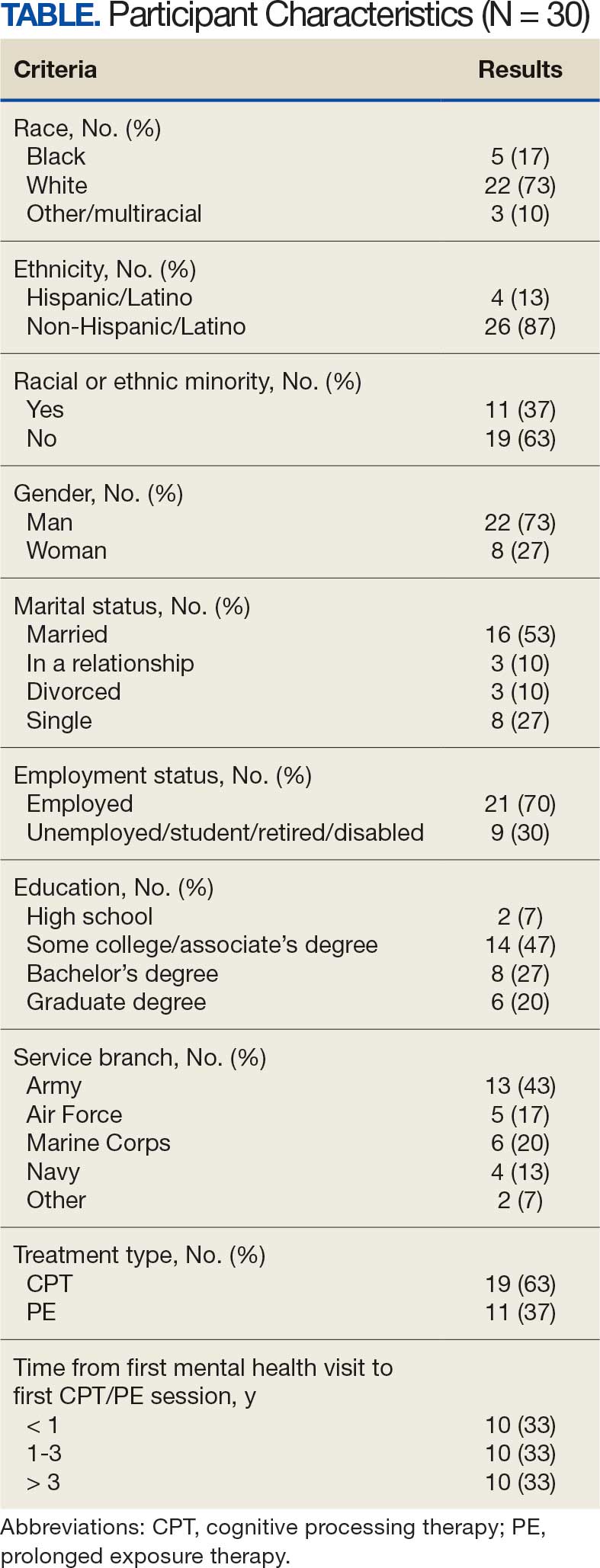

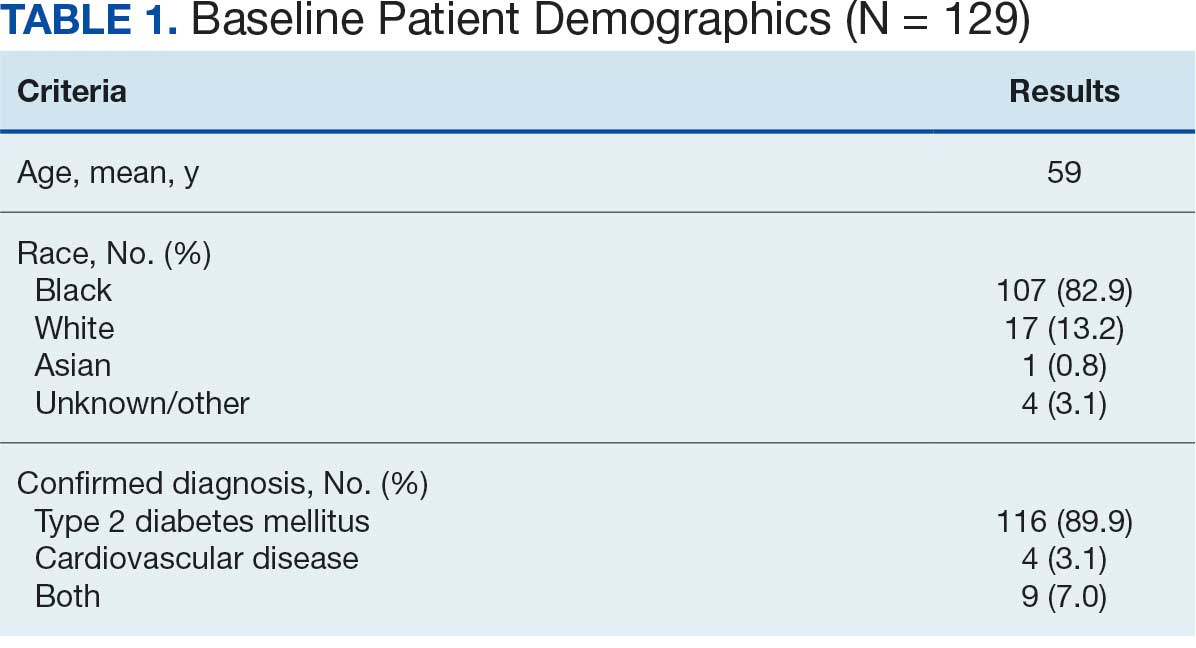

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 72.9 (9.4) years (range, 39-90 years). The mean (SD) duration of military service was 1654 (1421) days (about 4 years, 6 months, and 10 days). Of the 35 patients included, 22 (63%) served during the Vietnam era (November 1, 1965, to April 30, 1975) and 2 (6%) served during the Persian Gulf War era (August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991). Seventeen veterans (49%) served in the Army, 9 in the Navy (26%), 5 in the Air Force (14%), and 4 in the Marine Corps (11%). Definitive AO exposure was noted in 13 patients (37%) (Table 1).

Of the 35 patients, 24 (69%) had metastatic disease and the primary site of melanoma was unknown in 14 patients (40%). One patient (Patient 32) had an intraocular melanoma. The primary site was the trunk for 11 patients (31%), the face/head for 7 patients (20%) and extremities for 3 patients (9%). Eight patients (23%) were pT3 stage (thickness > 2 mm but < 4 mm), 7 patients (20%) were pT4 stage (thickness > 4 mm), and 5 patients (14%) were pT1 (thickness ≥ 1 mm). One patient had a primary lesion at pT2 stage, and 1 had a Tis stage lesion. Three patients (9%) had a family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative.

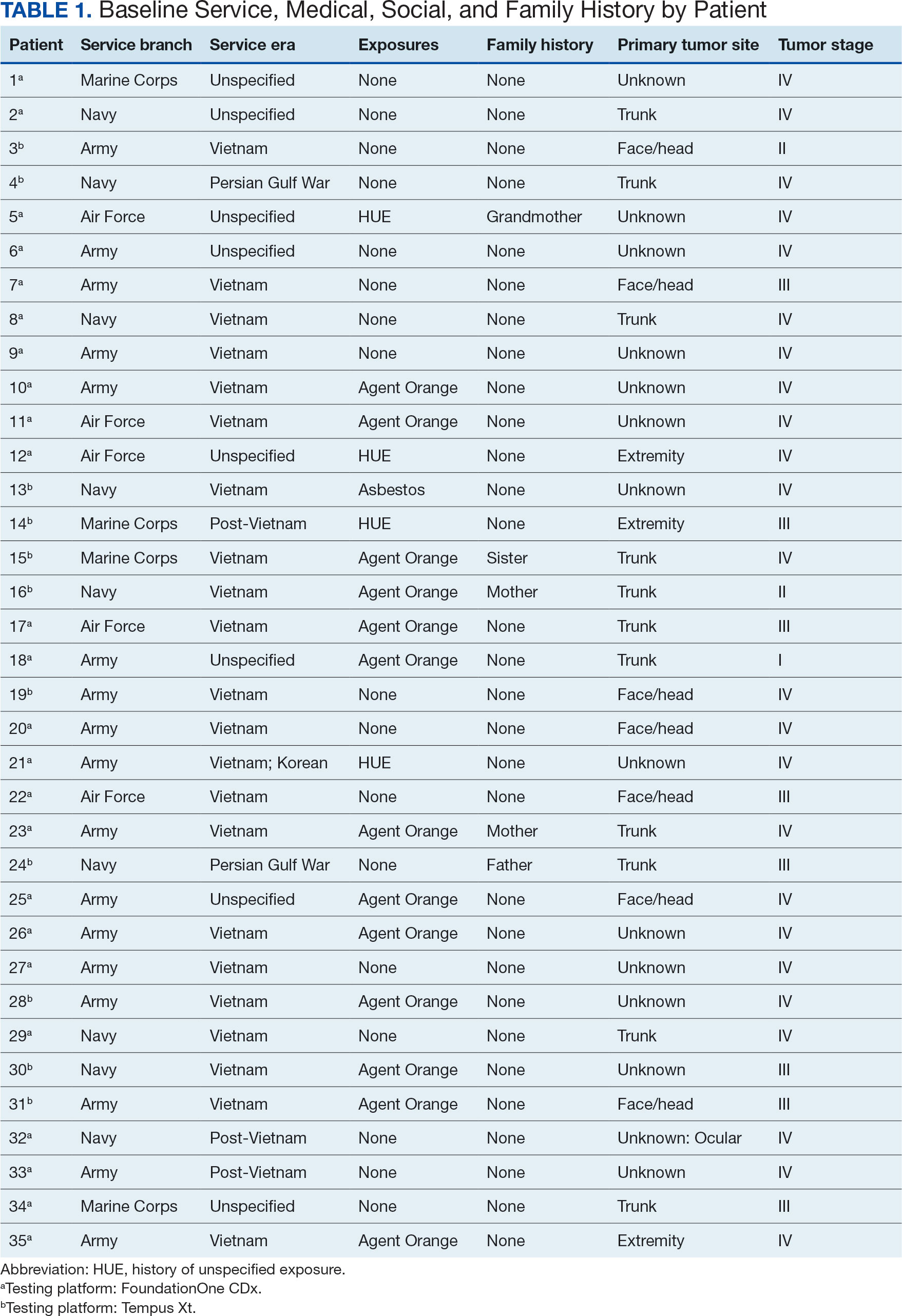

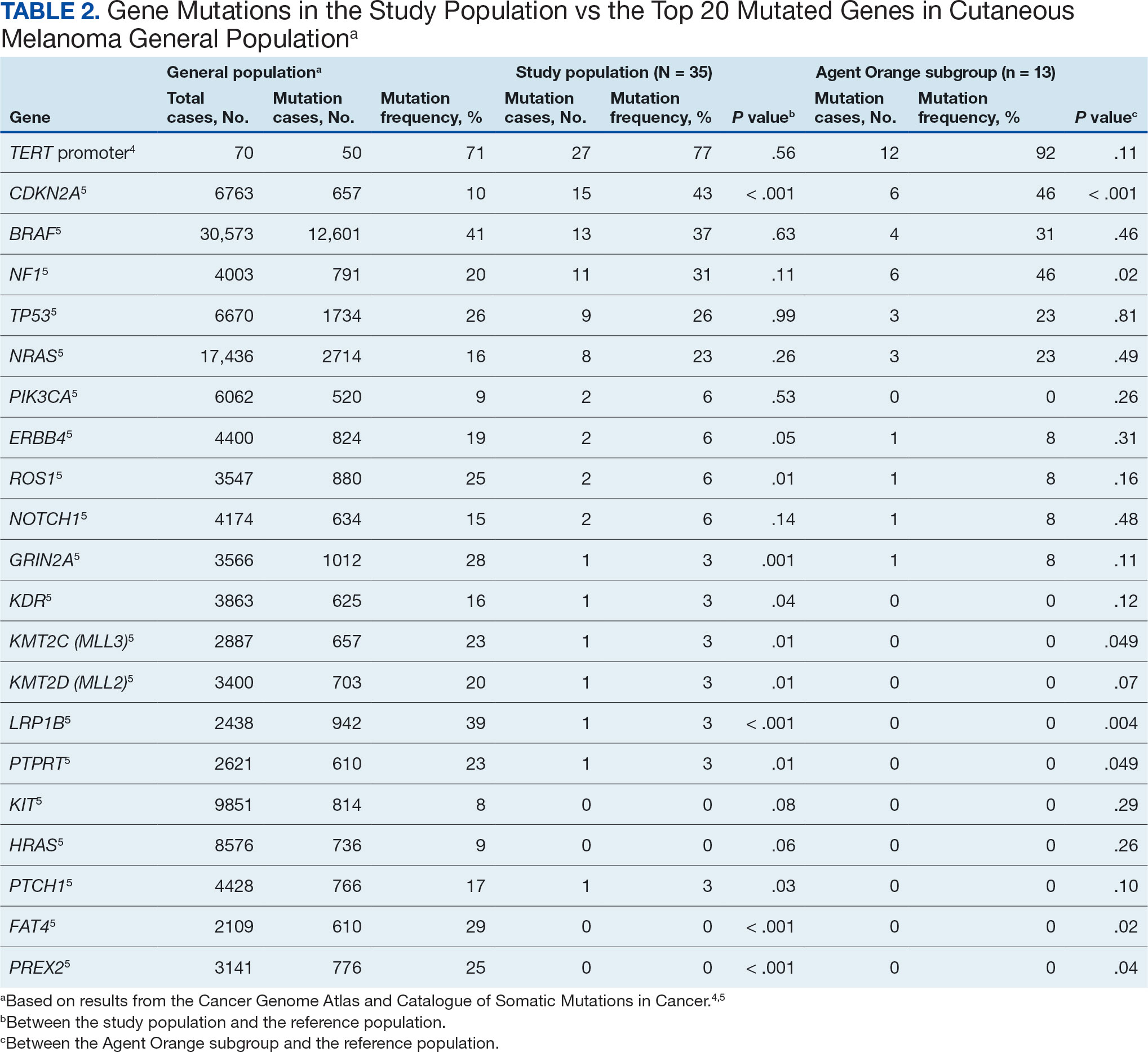

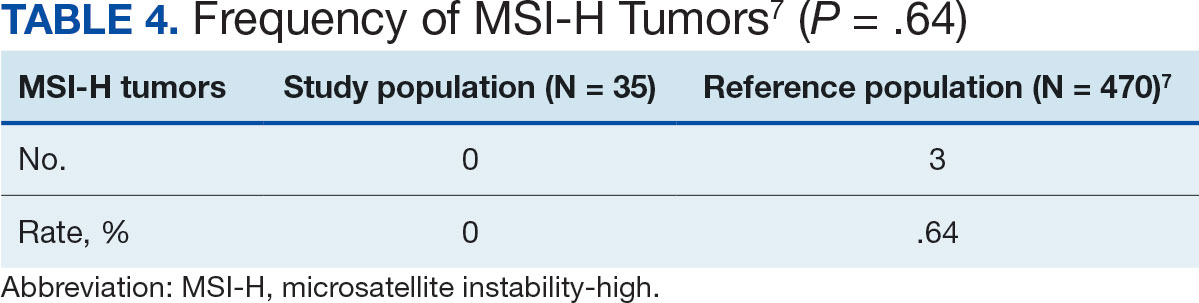

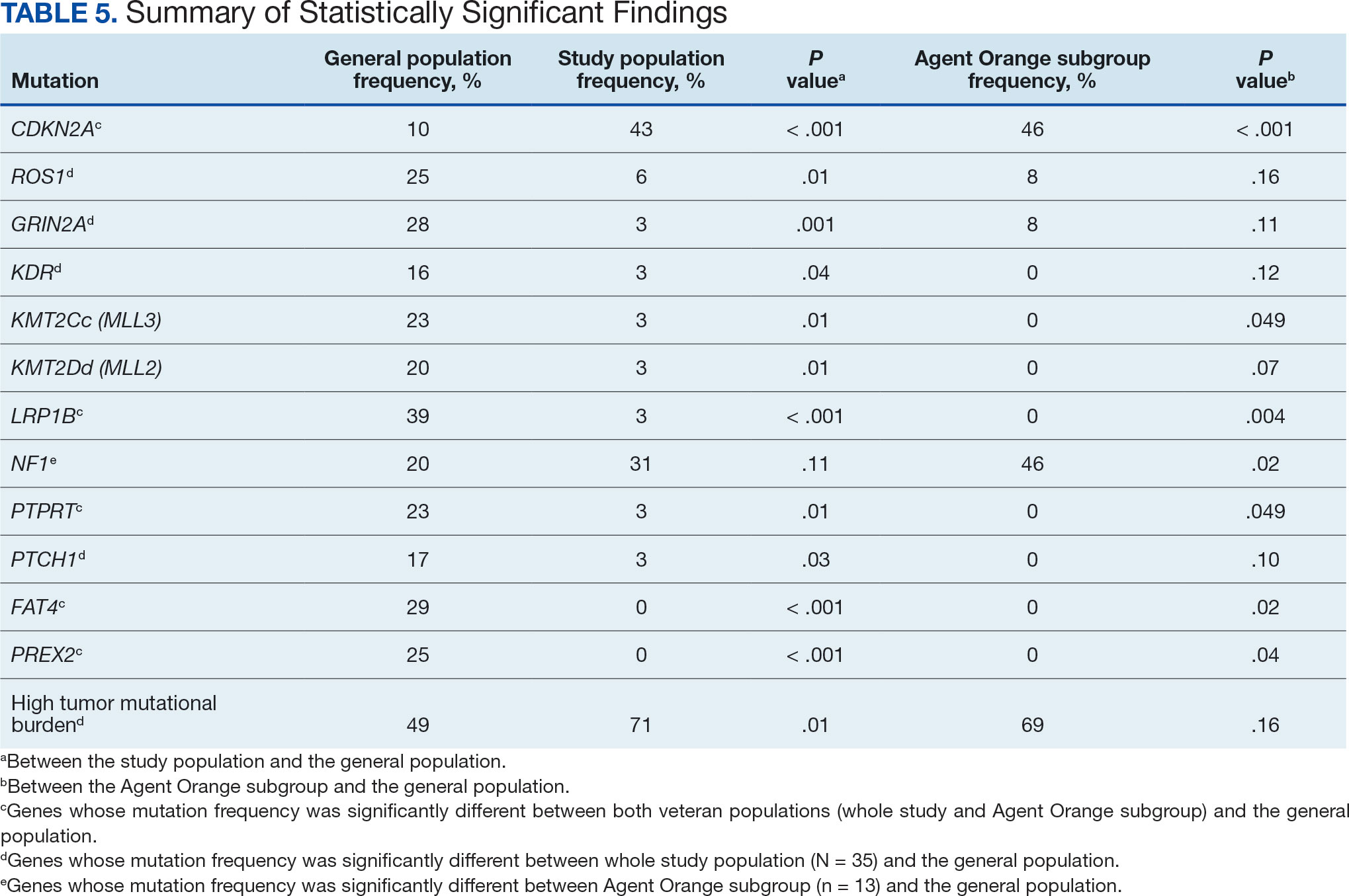

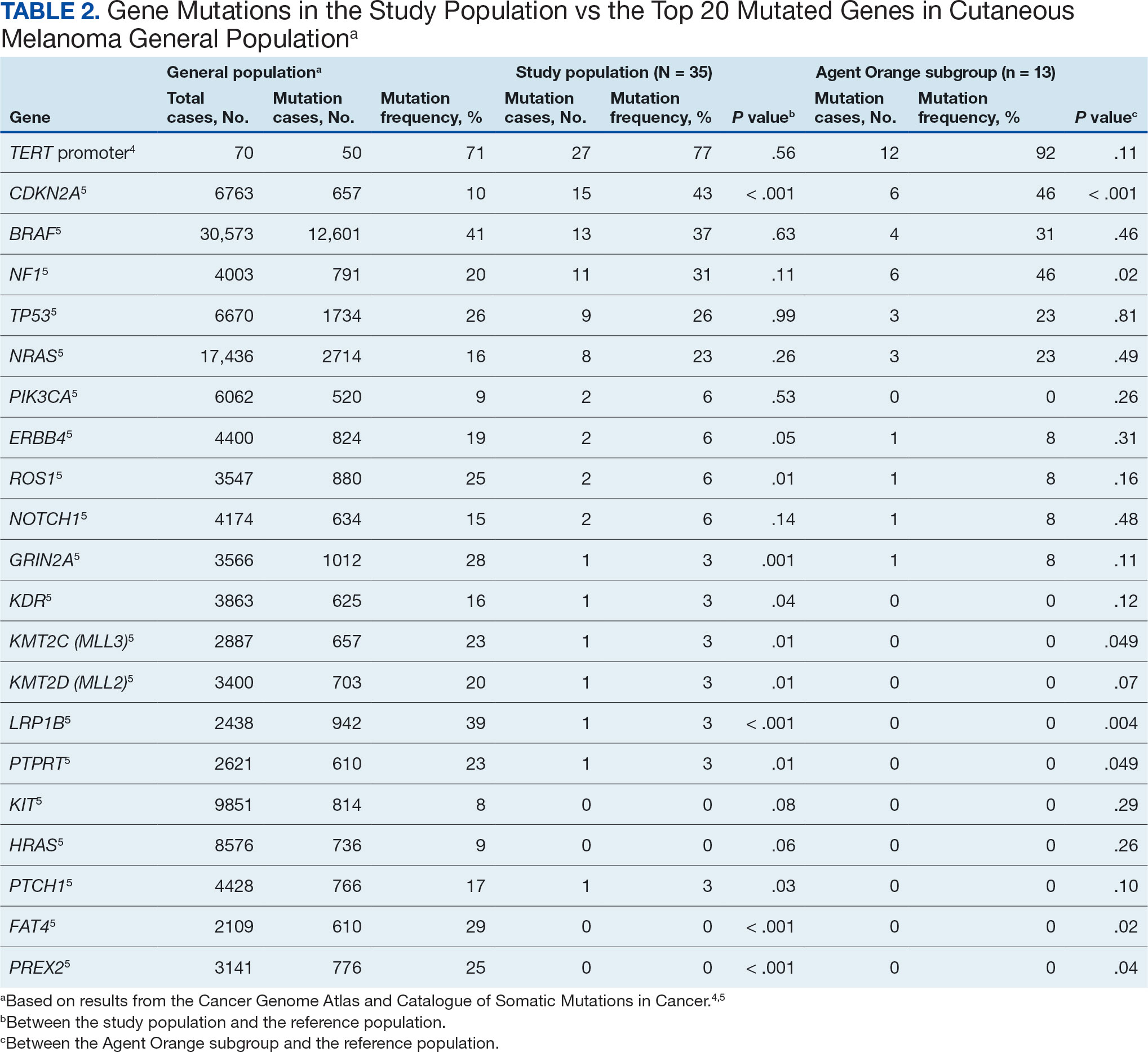

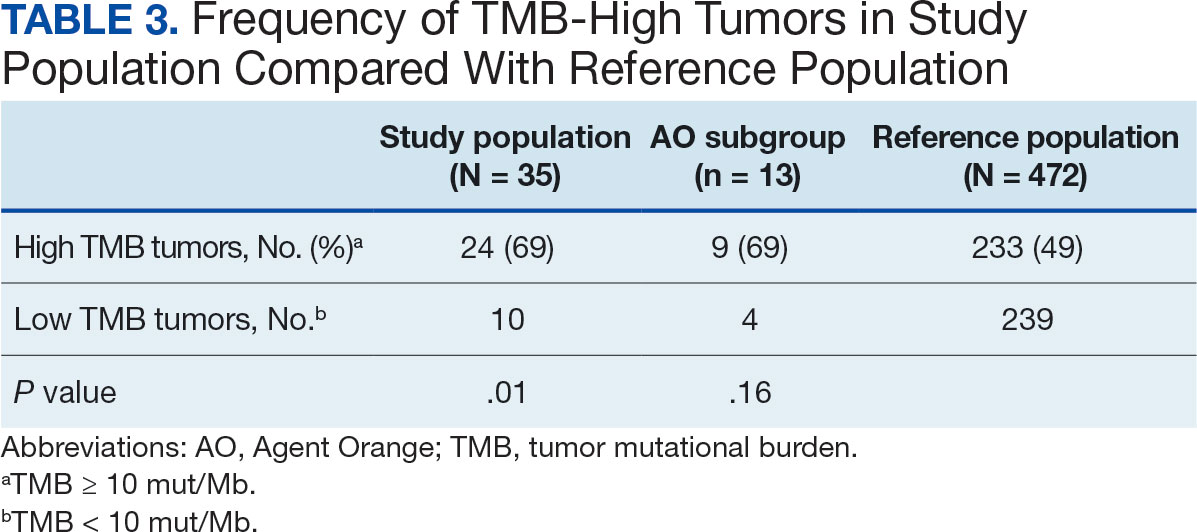

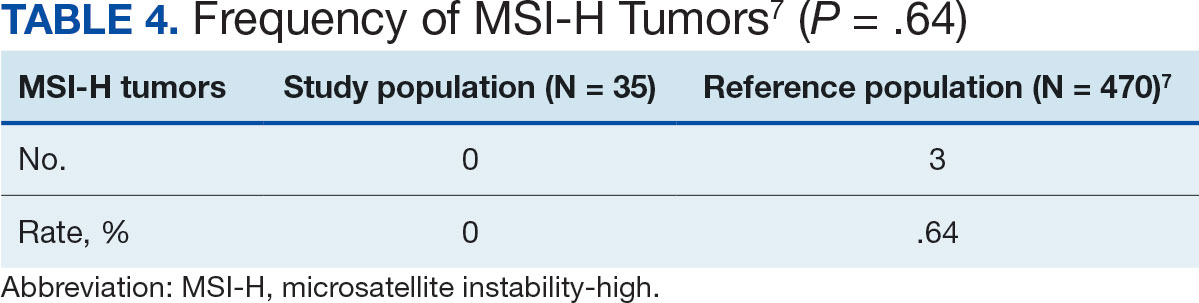

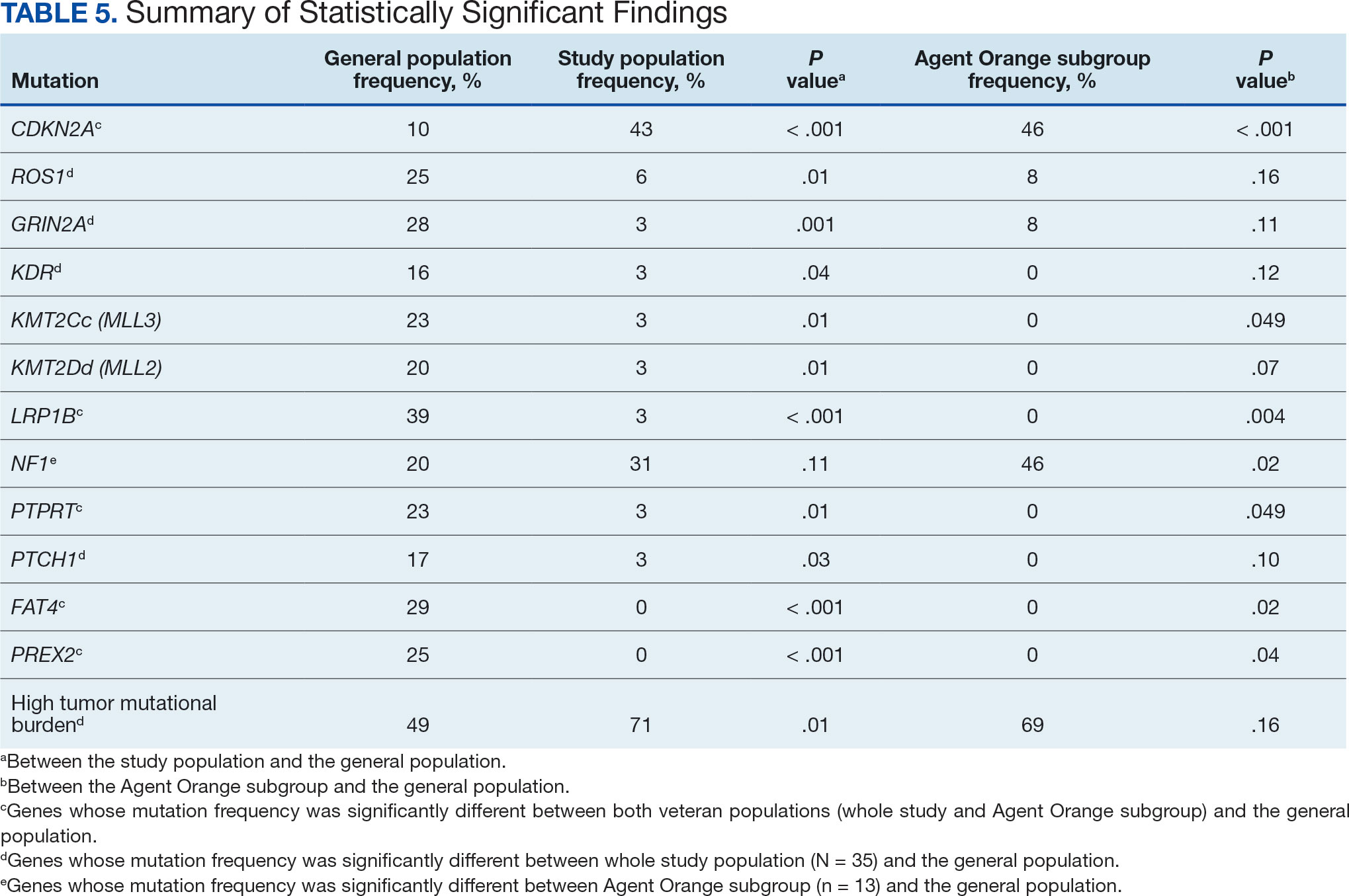

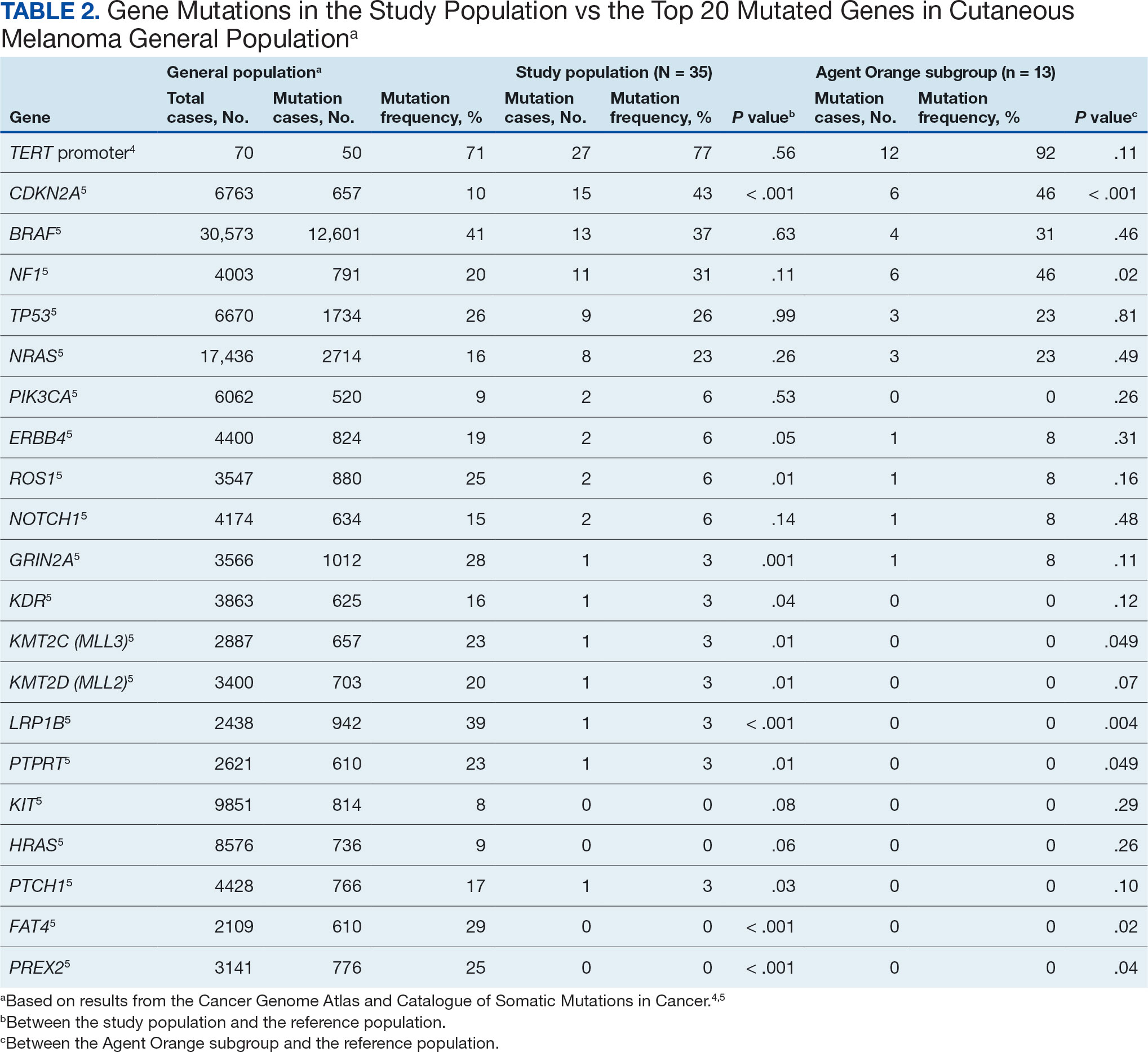

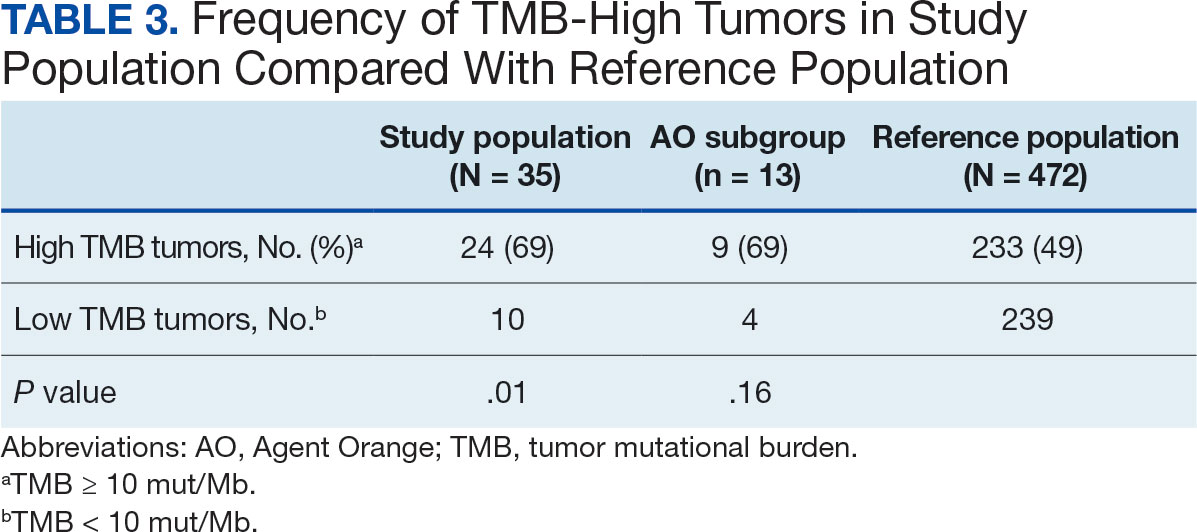

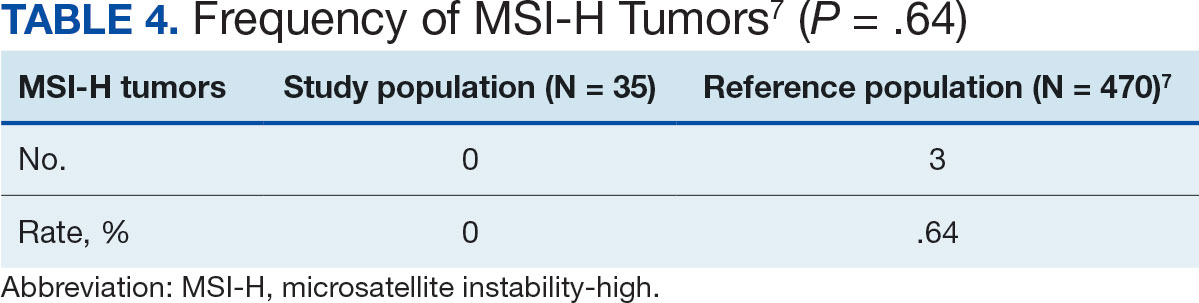

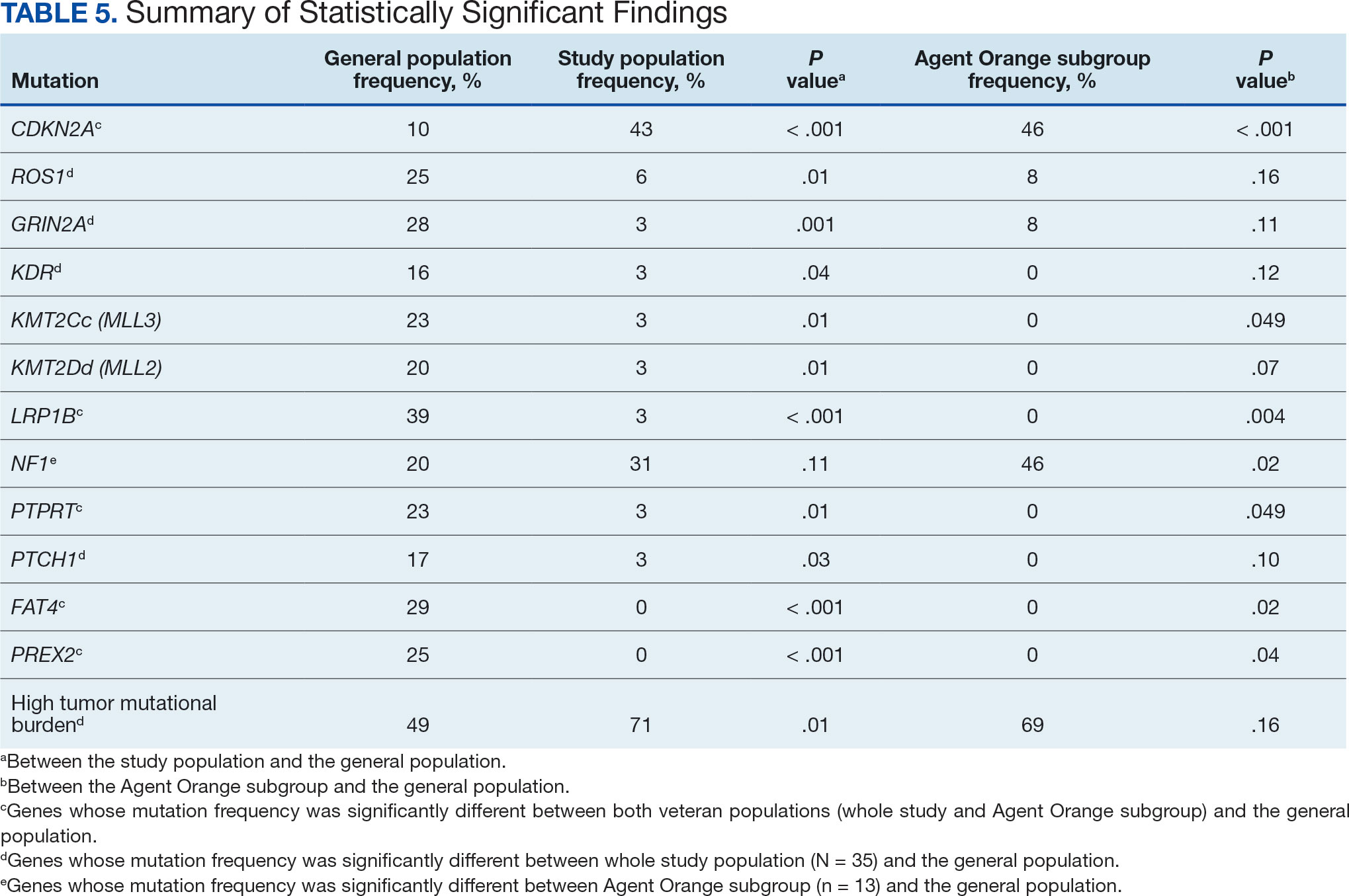

The list of genes mutated in melanoma cells in the study population is provided in the eAppendix.10,11 Twenty-seven patients (77%) had mutations in TERT promoter, 15 (43%) in CDKN2A/B, 13 (37%) in BRAF, 11 (31%) in NF1, 9 (26%) in TP53, and 8 (23%) in NRAS (Table 2). The majority of mutations in TERT promoter were c.- 146C>T (18 of 27 patients [67%]), whereas c.-124C>T was the second-most common (8 of 27 patients [30%]). The 2 observed mutations in the 13 patients with BRAF mutations were V600E and V600K, with almost equal distribution (54% and 46%, respectively). The mean (SD) TMB was 33.2 (39) mut/Mb (range, 1-203 mut/Mb). Ten patients (29%) had a TMB < 10 mut/Mb, whereas 24 (69%) had a TMB > 10 mut/Mb. The TMB could not be determined in 1 case. The frequency of TMB-high tumors in the study population compared with frequency in the reference population is shown in Table 3.12 Only 3 patients (0.64%) in the reference population had MSI-H tumors, and the microsatellite status could not be determined in those tumors (Table 4).13 Table 5 outlines statistically significant findings.

Agent Orange Subgroup

AO was a tactical herbicide used by the US military, named for the orange band around the storage barrels. Possible mutagenic properties of AO have been attributed to its byproduct, dioxin. Among the most common cancers known to be associated with AO exposure are bladder and prostate carcinoma and hematopoietic neoplasms. The association between genetic alterations and AO exposure was studied in veterans with prostate cancer.14 However, to our knowledge, insufficient information is available to determine whether an association exists between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant dioxin and melanoma. Because a significant proportion of this study population had a well-documented history of AO exposure (37.1%), we were able to analyze them as a subgroup and to separately compare their mutation frequency with the general population.

Results were notable for different distributions of the most frequently mutated genes in the AO subgroup compared with the whole study population. As such, TERT promoter remained the most frequently mutated gene (92%), followed by CDKN2A/B (46%); however, frequency of mutations in NF1 (46%) outnumbered those of BRAF (31%), the fourth-most common mutation. Moreover, when compared with the general melanoma population, a significantly higher frequency of mutations in the NF1 gene was observed in the AO subgroup—not the entire study population.

Discussion

Given that veterans constitute a distinct population, there is reasonable interest in investigating characteristic health issues related to military service. Skin cancer—melanoma in particular—has been researched recently in a veteran population. The differences in demographics, tumor characteristics, and melanoma- specific survival in veterans compared with the general population have already been assessed. According to Chang et al, compared with the general population, veterans are more likely to present with metastatic disease and have lower 5-year survival rates.8

Melanoma is one of the most highly mutated malignancies.15 Fortunately, the most common mutation in melanoma, BRAF V600E, is now considered therapeutically targetable. However, there are still many mutations that are less often discussed and not well understood. Regardless of therapeutic implications, all mutations observed in melanoma are worth investigating because a tumor’s genomic profile also can provide prognostic and etiologic information. Developing comprehensive descriptions of melanoma mutational profiles in specific populations is critical to advancing etiologic understanding and informing prevention strategies.

Our results demonstrate the high prevalence of TERT promoter mutations with characteristic ultraviolet signature (C>T) in the study population. This aligns with general evidence that TERT promoter mutations are common in cutaneous melanomas: 77% of this study sample and up to 86% of all mutations are TERT promoter mutations, according to Davis et al.15TERT promoter mutations are positively associated with the initiation, invasion, and metastasis of melanoma. In certain subtypes, there is evidence that the presence of TERT promoter mutations is significantly associated with risk for extranodal metastasis and death.16 The second-most common mutated gene in the veteran study population was CDKN2A/B (43%), and the third-most mutated gene was BRAF (37%).

In chronically sun-exposed skin NF1, NRAS, and occasionally BRAF V600K mutations tend to predominate. BRAF V600E mutations, on the other hand, are rare in these melanomas.15 In our study population, the most prevalent melanoma site was the trunk (31%), which is considered a location with an intermittent pattern of sun exposure.17

This study population also had a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations. High frequencies of CDKN2A/B mutations have been reported in familial melanomas, but only 1 patient with CDKN2A/B mutations had a known family history of melanoma.15 Tumors in the study population showed significantly lower frequency of mutations in ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 (P < .05).

In this study the subgroup of veterans with AO exposure differed from the whole study population. As such, CDKN2A/B mutations were observed with the same frequency as NF1 mutations (46% each); however, BRAF mutations constituted only 31% of the mutations. In addition, the frequency of NF1 mutations was significantly higher in the AO subgroup compared with the general population, but not in the whole study population.

Our sample also differed from the reference population by showing a significantly higher frequency of TMB-high (ie, ≥ 10 mut/Mb) tumors (71% vs 49%; P = .01).12 Interestingly, no significant difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors was observed between the AO subgroup and the reference population (69% vs 49%; P = .16). There also was no statistically significant difference between the frequency of MSI-H tumors in our study population and the reference population (P = .64).13

One patient in the study population had uveal melanoma. Mutations encountered in this patient’s tumor differed from the general mutational profile of tumors. None of the 21 mutations depicted in Table 2 were present in this sample.10,11 On the other hand, those mutations frequently observed in intraocular melanomas, BAP1 and GNA11, were present in this patient.18 Additionally, this particular melanoma possessed mutations in genes RICTOR, RAD21, and PIK3R1.

Limitations

This study population consisted exclusively of male patients, introducing sex as a potential confounder in analyzing differences between the study population and the general population. As noted in a 2020 systematic review, there were no sex-based differences in the frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT genes.19

Regarding NF1 mutations, only NF1-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas were more frequently observed in female patients, whereas nonacral NF1-mutated melanomas were more frequently observed in male patients.20 However, there is currently no clear evidence of whether the mutational landscapes of cutaneous melanoma differ by sex.21 Among the 11 cases with NF1-mutatation, site of origin was known in 6, 5 of which originated at nonacral sites. Although the AO subgroup also consisted entirely of male patients, this does not explain the observed increased frequency of NF1 mutations relative to the general population. No such difference was observed between the whole study population, which also consisted exclusively of male patients, and the general population. The similar frequencies of nonacral location in the whole study population (3 acral, 18 nonacral, 14 unknown site of origin) and AO subgroup (1 acral, 7 nonacral, 5 unknown site of origin) preclude location as an explanation.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network proposed a framework for genomic classification of melanoma into 4 subtypes based on the pattern of the most prevalent significantly mutated genes: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and triple–wild-type. According to that study, BRAF mutations were indeed associated with younger age, in contrast to the NF1-mutant genomic subtype, which was more prevalent in older individuals with higher TMB.22 This emphasizes the need to interpret the potential association of AO exposure and NF1 mutation in melanoma with caution, although additional studies are required to observe the difference between the veteran population and age-matched general population.

On the other hand, Yu et al reported no significant differences of TMB values between patients aged < 60 and ≥ 60 years with melanoma.23 In short, the observed differences we report in our limited study warrant additional investigation with larger sample sizes, sex-matched controlling, and age-matched controlling. The study was limited by its small sample size and the single location.

Conclusion

The genomic profile of melanomas in the veteran population appears to be similar to that of the general population with a few possible differences. Melanomas in the veteran study population showed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations; lower frequency of ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 mutations; and higher TMB. In addition, melanomas in the AO subgroup showed higher frequencies of NF1 mutations. The significance of such findings remains to be determined by further investigation.

- Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military: An updated analysis. Cancer. 2024;130(1):96-106. doi:10.1002/cncr.34978

- Singer DS. A new phase of the Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1345-1347. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01881-5

- Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Melanoma mortality trends in 28 European countries: a retrospective analysis for the years 1960-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1514. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/cancers15051514

- Okobi OE, Abreo E, Sams NP, et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: an analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) database. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70697. doi:10.7759/cureus.70697

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:e2034-e2039. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00127

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Rezaei SJ, Kim J, Onyeka S, et al. Skin cancer and other dermatologic conditions among US veterans. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3043

- Chang MS, La J, Trepanowski N, et al. Increased relative proportions of advanced melanoma among veterans: a comparative analysis with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.063

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957-959. doi:10.1126/science.1229259

- Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941-D947. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1015

- Li M, Gao X, Wang X. Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1090838. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1090838

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00073. doi:10.1200/PO.17.00073

- Lui AJ, Pagadala MS, Zhong AY, et al. Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the Million Veteran Program. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.06.14.23291413. doi:10.1101/2023.06.14.23291413

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499. doi:10.1002/cncr.31345

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J Oncol. 2022;2022:6300329. doi:10.1155/2022/6300329

- Whiteman DC, Stickley M, Watt P, et al. Anatomic site, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3172-3177. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1325

- Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:728-733. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903

- Gutiérrez-Castañeda LD, Nova JA, Tovar-Parra JD. Frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in different populations and histological subtypes of melanoma: a systemic review. Melanoma Res. 2020;30:62- 70. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000628

- Thielmann CM, Chorti E, Matull J, et al. NF1-mutated melanomas reveal distinct clinical characteristics depending on tumour origin and respond favourably to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.035

- D’Ecclesiis O, Caini S, Martinoli C, et al. Gender-dependent specificities in cutaneous melanoma predisposition, risk factors, somatic mutations, prognostic and predictive factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7945. doi:10.3390/ijerph18157945

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044

- Yu Z, Wang J, Feng L, et al. Association of tumor mutational burden with age in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e13590-e13590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e13590

The veteran population, with its unique and diverse types of exposure and military service experiences, faces distinct health factors compared with the general population. These factors can be categorized into exposures during military service and those occurring postservice. While the latter phase incorporates psychological issues that may arise while transitioning to civilian life, the service period is associated with major physical, chemical, and psychological exposures that can impact veterans’ health. Carcinogenesis related to military exposures is concerning, and different types of malignancies have been associated with military exposures.1 The 2022 introduction of the Cancer Moonshot initiative served as a breeding ground for multiple projects aimed at investigation of exposure-related carcinogenesis, prompting increased attention and efforts to linking specific exposures to specific malignancies.2

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer, accounting for 1.3% of all cancer deaths.3 Although it may only account for 1% to 5% of skin cancer diagnoses, its incidence in the United States’ population has been increasing.4,5 There were 97,610 estimated new cases of melanoma in 2023, according to the National Cancer Institute.6

The incidence of melanoma may be higher in the military population compared with the general population.7 Melanoma is the fourth-most common cancer diagnosed in veterans.8

Several demographic characteristics of the US military population are associated with higher melanoma incidence and poorer prognosis, including male sex, older age, and White race. Apart from sun exposure—a known risk factor for melanoma development—other factors, such as service branch, seem to contribute to risk, with the highest melanoma rates noted in the Air Force.9 According to a study by Chang et al, veterans have a higher risk of stage III (18%) or stage IV (13%) melanoma at initial diagnosis.8

Molecular testing of metastatic melanoma is currently the standard of care for guiding the use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies such as BRAF, MEK, and KIT inhibitors. This comparative analysis details the melanoma comprehensive genomic profiles observed at a large US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC) and those reported in reference databases.

Methods

A query to select all metastatic melanomas sent for comprehensive genomic profiling from the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), identified 35 cases from 2019 through 2023 as the study population. The health records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic information, military service history, melanoma history, other medical, social, and family histories. The comprehensive genomic profiling reports were reviewed to collect the reported pathogenic variants, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) for each case.

The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used to identify the most commonly mutated genes in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for the general population.4,5 The literature was consulted to determine the MSI status and TMB in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for separate reference populations.6,7 The frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) status, TMB ≥ 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb), and mutations in each of the 20 most commonly mutated genes was determined and compared between melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas and KCVAMC cases. Corresponding P values were calculated to identify significant differences. Values were calculated for the entire sample as well as a subgroup with Agent Orange (AO) exposure. The study was approved by the KCVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 72.9 (9.4) years (range, 39-90 years). The mean (SD) duration of military service was 1654 (1421) days (about 4 years, 6 months, and 10 days). Of the 35 patients included, 22 (63%) served during the Vietnam era (November 1, 1965, to April 30, 1975) and 2 (6%) served during the Persian Gulf War era (August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991). Seventeen veterans (49%) served in the Army, 9 in the Navy (26%), 5 in the Air Force (14%), and 4 in the Marine Corps (11%). Definitive AO exposure was noted in 13 patients (37%) (Table 1).

Of the 35 patients, 24 (69%) had metastatic disease and the primary site of melanoma was unknown in 14 patients (40%). One patient (Patient 32) had an intraocular melanoma. The primary site was the trunk for 11 patients (31%), the face/head for 7 patients (20%) and extremities for 3 patients (9%). Eight patients (23%) were pT3 stage (thickness > 2 mm but < 4 mm), 7 patients (20%) were pT4 stage (thickness > 4 mm), and 5 patients (14%) were pT1 (thickness ≥ 1 mm). One patient had a primary lesion at pT2 stage, and 1 had a Tis stage lesion. Three patients (9%) had a family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative.

The list of genes mutated in melanoma cells in the study population is provided in the eAppendix.10,11 Twenty-seven patients (77%) had mutations in TERT promoter, 15 (43%) in CDKN2A/B, 13 (37%) in BRAF, 11 (31%) in NF1, 9 (26%) in TP53, and 8 (23%) in NRAS (Table 2). The majority of mutations in TERT promoter were c.- 146C>T (18 of 27 patients [67%]), whereas c.-124C>T was the second-most common (8 of 27 patients [30%]). The 2 observed mutations in the 13 patients with BRAF mutations were V600E and V600K, with almost equal distribution (54% and 46%, respectively). The mean (SD) TMB was 33.2 (39) mut/Mb (range, 1-203 mut/Mb). Ten patients (29%) had a TMB < 10 mut/Mb, whereas 24 (69%) had a TMB > 10 mut/Mb. The TMB could not be determined in 1 case. The frequency of TMB-high tumors in the study population compared with frequency in the reference population is shown in Table 3.12 Only 3 patients (0.64%) in the reference population had MSI-H tumors, and the microsatellite status could not be determined in those tumors (Table 4).13 Table 5 outlines statistically significant findings.

Agent Orange Subgroup

AO was a tactical herbicide used by the US military, named for the orange band around the storage barrels. Possible mutagenic properties of AO have been attributed to its byproduct, dioxin. Among the most common cancers known to be associated with AO exposure are bladder and prostate carcinoma and hematopoietic neoplasms. The association between genetic alterations and AO exposure was studied in veterans with prostate cancer.14 However, to our knowledge, insufficient information is available to determine whether an association exists between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant dioxin and melanoma. Because a significant proportion of this study population had a well-documented history of AO exposure (37.1%), we were able to analyze them as a subgroup and to separately compare their mutation frequency with the general population.

Results were notable for different distributions of the most frequently mutated genes in the AO subgroup compared with the whole study population. As such, TERT promoter remained the most frequently mutated gene (92%), followed by CDKN2A/B (46%); however, frequency of mutations in NF1 (46%) outnumbered those of BRAF (31%), the fourth-most common mutation. Moreover, when compared with the general melanoma population, a significantly higher frequency of mutations in the NF1 gene was observed in the AO subgroup—not the entire study population.

Discussion

Given that veterans constitute a distinct population, there is reasonable interest in investigating characteristic health issues related to military service. Skin cancer—melanoma in particular—has been researched recently in a veteran population. The differences in demographics, tumor characteristics, and melanoma- specific survival in veterans compared with the general population have already been assessed. According to Chang et al, compared with the general population, veterans are more likely to present with metastatic disease and have lower 5-year survival rates.8

Melanoma is one of the most highly mutated malignancies.15 Fortunately, the most common mutation in melanoma, BRAF V600E, is now considered therapeutically targetable. However, there are still many mutations that are less often discussed and not well understood. Regardless of therapeutic implications, all mutations observed in melanoma are worth investigating because a tumor’s genomic profile also can provide prognostic and etiologic information. Developing comprehensive descriptions of melanoma mutational profiles in specific populations is critical to advancing etiologic understanding and informing prevention strategies.

Our results demonstrate the high prevalence of TERT promoter mutations with characteristic ultraviolet signature (C>T) in the study population. This aligns with general evidence that TERT promoter mutations are common in cutaneous melanomas: 77% of this study sample and up to 86% of all mutations are TERT promoter mutations, according to Davis et al.15TERT promoter mutations are positively associated with the initiation, invasion, and metastasis of melanoma. In certain subtypes, there is evidence that the presence of TERT promoter mutations is significantly associated with risk for extranodal metastasis and death.16 The second-most common mutated gene in the veteran study population was CDKN2A/B (43%), and the third-most mutated gene was BRAF (37%).

In chronically sun-exposed skin NF1, NRAS, and occasionally BRAF V600K mutations tend to predominate. BRAF V600E mutations, on the other hand, are rare in these melanomas.15 In our study population, the most prevalent melanoma site was the trunk (31%), which is considered a location with an intermittent pattern of sun exposure.17

This study population also had a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations. High frequencies of CDKN2A/B mutations have been reported in familial melanomas, but only 1 patient with CDKN2A/B mutations had a known family history of melanoma.15 Tumors in the study population showed significantly lower frequency of mutations in ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 (P < .05).

In this study the subgroup of veterans with AO exposure differed from the whole study population. As such, CDKN2A/B mutations were observed with the same frequency as NF1 mutations (46% each); however, BRAF mutations constituted only 31% of the mutations. In addition, the frequency of NF1 mutations was significantly higher in the AO subgroup compared with the general population, but not in the whole study population.

Our sample also differed from the reference population by showing a significantly higher frequency of TMB-high (ie, ≥ 10 mut/Mb) tumors (71% vs 49%; P = .01).12 Interestingly, no significant difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors was observed between the AO subgroup and the reference population (69% vs 49%; P = .16). There also was no statistically significant difference between the frequency of MSI-H tumors in our study population and the reference population (P = .64).13

One patient in the study population had uveal melanoma. Mutations encountered in this patient’s tumor differed from the general mutational profile of tumors. None of the 21 mutations depicted in Table 2 were present in this sample.10,11 On the other hand, those mutations frequently observed in intraocular melanomas, BAP1 and GNA11, were present in this patient.18 Additionally, this particular melanoma possessed mutations in genes RICTOR, RAD21, and PIK3R1.

Limitations

This study population consisted exclusively of male patients, introducing sex as a potential confounder in analyzing differences between the study population and the general population. As noted in a 2020 systematic review, there were no sex-based differences in the frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT genes.19

Regarding NF1 mutations, only NF1-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas were more frequently observed in female patients, whereas nonacral NF1-mutated melanomas were more frequently observed in male patients.20 However, there is currently no clear evidence of whether the mutational landscapes of cutaneous melanoma differ by sex.21 Among the 11 cases with NF1-mutatation, site of origin was known in 6, 5 of which originated at nonacral sites. Although the AO subgroup also consisted entirely of male patients, this does not explain the observed increased frequency of NF1 mutations relative to the general population. No such difference was observed between the whole study population, which also consisted exclusively of male patients, and the general population. The similar frequencies of nonacral location in the whole study population (3 acral, 18 nonacral, 14 unknown site of origin) and AO subgroup (1 acral, 7 nonacral, 5 unknown site of origin) preclude location as an explanation.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network proposed a framework for genomic classification of melanoma into 4 subtypes based on the pattern of the most prevalent significantly mutated genes: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and triple–wild-type. According to that study, BRAF mutations were indeed associated with younger age, in contrast to the NF1-mutant genomic subtype, which was more prevalent in older individuals with higher TMB.22 This emphasizes the need to interpret the potential association of AO exposure and NF1 mutation in melanoma with caution, although additional studies are required to observe the difference between the veteran population and age-matched general population.

On the other hand, Yu et al reported no significant differences of TMB values between patients aged < 60 and ≥ 60 years with melanoma.23 In short, the observed differences we report in our limited study warrant additional investigation with larger sample sizes, sex-matched controlling, and age-matched controlling. The study was limited by its small sample size and the single location.

Conclusion

The genomic profile of melanomas in the veteran population appears to be similar to that of the general population with a few possible differences. Melanomas in the veteran study population showed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations; lower frequency of ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 mutations; and higher TMB. In addition, melanomas in the AO subgroup showed higher frequencies of NF1 mutations. The significance of such findings remains to be determined by further investigation.

The veteran population, with its unique and diverse types of exposure and military service experiences, faces distinct health factors compared with the general population. These factors can be categorized into exposures during military service and those occurring postservice. While the latter phase incorporates psychological issues that may arise while transitioning to civilian life, the service period is associated with major physical, chemical, and psychological exposures that can impact veterans’ health. Carcinogenesis related to military exposures is concerning, and different types of malignancies have been associated with military exposures.1 The 2022 introduction of the Cancer Moonshot initiative served as a breeding ground for multiple projects aimed at investigation of exposure-related carcinogenesis, prompting increased attention and efforts to linking specific exposures to specific malignancies.2

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer, accounting for 1.3% of all cancer deaths.3 Although it may only account for 1% to 5% of skin cancer diagnoses, its incidence in the United States’ population has been increasing.4,5 There were 97,610 estimated new cases of melanoma in 2023, according to the National Cancer Institute.6

The incidence of melanoma may be higher in the military population compared with the general population.7 Melanoma is the fourth-most common cancer diagnosed in veterans.8

Several demographic characteristics of the US military population are associated with higher melanoma incidence and poorer prognosis, including male sex, older age, and White race. Apart from sun exposure—a known risk factor for melanoma development—other factors, such as service branch, seem to contribute to risk, with the highest melanoma rates noted in the Air Force.9 According to a study by Chang et al, veterans have a higher risk of stage III (18%) or stage IV (13%) melanoma at initial diagnosis.8

Molecular testing of metastatic melanoma is currently the standard of care for guiding the use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies such as BRAF, MEK, and KIT inhibitors. This comparative analysis details the melanoma comprehensive genomic profiles observed at a large US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC) and those reported in reference databases.

Methods

A query to select all metastatic melanomas sent for comprehensive genomic profiling from the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), identified 35 cases from 2019 through 2023 as the study population. The health records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic information, military service history, melanoma history, other medical, social, and family histories. The comprehensive genomic profiling reports were reviewed to collect the reported pathogenic variants, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) for each case.

The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used to identify the most commonly mutated genes in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for the general population.4,5 The literature was consulted to determine the MSI status and TMB in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for separate reference populations.6,7 The frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) status, TMB ≥ 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb), and mutations in each of the 20 most commonly mutated genes was determined and compared between melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas and KCVAMC cases. Corresponding P values were calculated to identify significant differences. Values were calculated for the entire sample as well as a subgroup with Agent Orange (AO) exposure. The study was approved by the KCVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 72.9 (9.4) years (range, 39-90 years). The mean (SD) duration of military service was 1654 (1421) days (about 4 years, 6 months, and 10 days). Of the 35 patients included, 22 (63%) served during the Vietnam era (November 1, 1965, to April 30, 1975) and 2 (6%) served during the Persian Gulf War era (August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991). Seventeen veterans (49%) served in the Army, 9 in the Navy (26%), 5 in the Air Force (14%), and 4 in the Marine Corps (11%). Definitive AO exposure was noted in 13 patients (37%) (Table 1).

Of the 35 patients, 24 (69%) had metastatic disease and the primary site of melanoma was unknown in 14 patients (40%). One patient (Patient 32) had an intraocular melanoma. The primary site was the trunk for 11 patients (31%), the face/head for 7 patients (20%) and extremities for 3 patients (9%). Eight patients (23%) were pT3 stage (thickness > 2 mm but < 4 mm), 7 patients (20%) were pT4 stage (thickness > 4 mm), and 5 patients (14%) were pT1 (thickness ≥ 1 mm). One patient had a primary lesion at pT2 stage, and 1 had a Tis stage lesion. Three patients (9%) had a family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative.

The list of genes mutated in melanoma cells in the study population is provided in the eAppendix.10,11 Twenty-seven patients (77%) had mutations in TERT promoter, 15 (43%) in CDKN2A/B, 13 (37%) in BRAF, 11 (31%) in NF1, 9 (26%) in TP53, and 8 (23%) in NRAS (Table 2). The majority of mutations in TERT promoter were c.- 146C>T (18 of 27 patients [67%]), whereas c.-124C>T was the second-most common (8 of 27 patients [30%]). The 2 observed mutations in the 13 patients with BRAF mutations were V600E and V600K, with almost equal distribution (54% and 46%, respectively). The mean (SD) TMB was 33.2 (39) mut/Mb (range, 1-203 mut/Mb). Ten patients (29%) had a TMB < 10 mut/Mb, whereas 24 (69%) had a TMB > 10 mut/Mb. The TMB could not be determined in 1 case. The frequency of TMB-high tumors in the study population compared with frequency in the reference population is shown in Table 3.12 Only 3 patients (0.64%) in the reference population had MSI-H tumors, and the microsatellite status could not be determined in those tumors (Table 4).13 Table 5 outlines statistically significant findings.

Agent Orange Subgroup

AO was a tactical herbicide used by the US military, named for the orange band around the storage barrels. Possible mutagenic properties of AO have been attributed to its byproduct, dioxin. Among the most common cancers known to be associated with AO exposure are bladder and prostate carcinoma and hematopoietic neoplasms. The association between genetic alterations and AO exposure was studied in veterans with prostate cancer.14 However, to our knowledge, insufficient information is available to determine whether an association exists between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant dioxin and melanoma. Because a significant proportion of this study population had a well-documented history of AO exposure (37.1%), we were able to analyze them as a subgroup and to separately compare their mutation frequency with the general population.

Results were notable for different distributions of the most frequently mutated genes in the AO subgroup compared with the whole study population. As such, TERT promoter remained the most frequently mutated gene (92%), followed by CDKN2A/B (46%); however, frequency of mutations in NF1 (46%) outnumbered those of BRAF (31%), the fourth-most common mutation. Moreover, when compared with the general melanoma population, a significantly higher frequency of mutations in the NF1 gene was observed in the AO subgroup—not the entire study population.

Discussion

Given that veterans constitute a distinct population, there is reasonable interest in investigating characteristic health issues related to military service. Skin cancer—melanoma in particular—has been researched recently in a veteran population. The differences in demographics, tumor characteristics, and melanoma- specific survival in veterans compared with the general population have already been assessed. According to Chang et al, compared with the general population, veterans are more likely to present with metastatic disease and have lower 5-year survival rates.8

Melanoma is one of the most highly mutated malignancies.15 Fortunately, the most common mutation in melanoma, BRAF V600E, is now considered therapeutically targetable. However, there are still many mutations that are less often discussed and not well understood. Regardless of therapeutic implications, all mutations observed in melanoma are worth investigating because a tumor’s genomic profile also can provide prognostic and etiologic information. Developing comprehensive descriptions of melanoma mutational profiles in specific populations is critical to advancing etiologic understanding and informing prevention strategies.

Our results demonstrate the high prevalence of TERT promoter mutations with characteristic ultraviolet signature (C>T) in the study population. This aligns with general evidence that TERT promoter mutations are common in cutaneous melanomas: 77% of this study sample and up to 86% of all mutations are TERT promoter mutations, according to Davis et al.15TERT promoter mutations are positively associated with the initiation, invasion, and metastasis of melanoma. In certain subtypes, there is evidence that the presence of TERT promoter mutations is significantly associated with risk for extranodal metastasis and death.16 The second-most common mutated gene in the veteran study population was CDKN2A/B (43%), and the third-most mutated gene was BRAF (37%).

In chronically sun-exposed skin NF1, NRAS, and occasionally BRAF V600K mutations tend to predominate. BRAF V600E mutations, on the other hand, are rare in these melanomas.15 In our study population, the most prevalent melanoma site was the trunk (31%), which is considered a location with an intermittent pattern of sun exposure.17

This study population also had a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations. High frequencies of CDKN2A/B mutations have been reported in familial melanomas, but only 1 patient with CDKN2A/B mutations had a known family history of melanoma.15 Tumors in the study population showed significantly lower frequency of mutations in ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 (P < .05).

In this study the subgroup of veterans with AO exposure differed from the whole study population. As such, CDKN2A/B mutations were observed with the same frequency as NF1 mutations (46% each); however, BRAF mutations constituted only 31% of the mutations. In addition, the frequency of NF1 mutations was significantly higher in the AO subgroup compared with the general population, but not in the whole study population.

Our sample also differed from the reference population by showing a significantly higher frequency of TMB-high (ie, ≥ 10 mut/Mb) tumors (71% vs 49%; P = .01).12 Interestingly, no significant difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors was observed between the AO subgroup and the reference population (69% vs 49%; P = .16). There also was no statistically significant difference between the frequency of MSI-H tumors in our study population and the reference population (P = .64).13

One patient in the study population had uveal melanoma. Mutations encountered in this patient’s tumor differed from the general mutational profile of tumors. None of the 21 mutations depicted in Table 2 were present in this sample.10,11 On the other hand, those mutations frequently observed in intraocular melanomas, BAP1 and GNA11, were present in this patient.18 Additionally, this particular melanoma possessed mutations in genes RICTOR, RAD21, and PIK3R1.

Limitations

This study population consisted exclusively of male patients, introducing sex as a potential confounder in analyzing differences between the study population and the general population. As noted in a 2020 systematic review, there were no sex-based differences in the frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT genes.19

Regarding NF1 mutations, only NF1-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas were more frequently observed in female patients, whereas nonacral NF1-mutated melanomas were more frequently observed in male patients.20 However, there is currently no clear evidence of whether the mutational landscapes of cutaneous melanoma differ by sex.21 Among the 11 cases with NF1-mutatation, site of origin was known in 6, 5 of which originated at nonacral sites. Although the AO subgroup also consisted entirely of male patients, this does not explain the observed increased frequency of NF1 mutations relative to the general population. No such difference was observed between the whole study population, which also consisted exclusively of male patients, and the general population. The similar frequencies of nonacral location in the whole study population (3 acral, 18 nonacral, 14 unknown site of origin) and AO subgroup (1 acral, 7 nonacral, 5 unknown site of origin) preclude location as an explanation.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network proposed a framework for genomic classification of melanoma into 4 subtypes based on the pattern of the most prevalent significantly mutated genes: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and triple–wild-type. According to that study, BRAF mutations were indeed associated with younger age, in contrast to the NF1-mutant genomic subtype, which was more prevalent in older individuals with higher TMB.22 This emphasizes the need to interpret the potential association of AO exposure and NF1 mutation in melanoma with caution, although additional studies are required to observe the difference between the veteran population and age-matched general population.

On the other hand, Yu et al reported no significant differences of TMB values between patients aged < 60 and ≥ 60 years with melanoma.23 In short, the observed differences we report in our limited study warrant additional investigation with larger sample sizes, sex-matched controlling, and age-matched controlling. The study was limited by its small sample size and the single location.

Conclusion

The genomic profile of melanomas in the veteran population appears to be similar to that of the general population with a few possible differences. Melanomas in the veteran study population showed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations; lower frequency of ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 mutations; and higher TMB. In addition, melanomas in the AO subgroup showed higher frequencies of NF1 mutations. The significance of such findings remains to be determined by further investigation.

- Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military: An updated analysis. Cancer. 2024;130(1):96-106. doi:10.1002/cncr.34978

- Singer DS. A new phase of the Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1345-1347. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01881-5

- Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Melanoma mortality trends in 28 European countries: a retrospective analysis for the years 1960-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1514. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/cancers15051514

- Okobi OE, Abreo E, Sams NP, et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: an analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) database. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70697. doi:10.7759/cureus.70697

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:e2034-e2039. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00127

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Rezaei SJ, Kim J, Onyeka S, et al. Skin cancer and other dermatologic conditions among US veterans. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3043

- Chang MS, La J, Trepanowski N, et al. Increased relative proportions of advanced melanoma among veterans: a comparative analysis with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.063

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957-959. doi:10.1126/science.1229259

- Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941-D947. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1015

- Li M, Gao X, Wang X. Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1090838. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1090838

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00073. doi:10.1200/PO.17.00073

- Lui AJ, Pagadala MS, Zhong AY, et al. Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the Million Veteran Program. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.06.14.23291413. doi:10.1101/2023.06.14.23291413

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499. doi:10.1002/cncr.31345

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J Oncol. 2022;2022:6300329. doi:10.1155/2022/6300329

- Whiteman DC, Stickley M, Watt P, et al. Anatomic site, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3172-3177. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1325

- Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:728-733. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903

- Gutiérrez-Castañeda LD, Nova JA, Tovar-Parra JD. Frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in different populations and histological subtypes of melanoma: a systemic review. Melanoma Res. 2020;30:62- 70. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000628

- Thielmann CM, Chorti E, Matull J, et al. NF1-mutated melanomas reveal distinct clinical characteristics depending on tumour origin and respond favourably to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.035

- D’Ecclesiis O, Caini S, Martinoli C, et al. Gender-dependent specificities in cutaneous melanoma predisposition, risk factors, somatic mutations, prognostic and predictive factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7945. doi:10.3390/ijerph18157945

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044

- Yu Z, Wang J, Feng L, et al. Association of tumor mutational burden with age in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e13590-e13590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e13590

- Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military: An updated analysis. Cancer. 2024;130(1):96-106. doi:10.1002/cncr.34978

- Singer DS. A new phase of the Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1345-1347. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01881-5

- Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Melanoma mortality trends in 28 European countries: a retrospective analysis for the years 1960-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1514. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/cancers15051514

- Okobi OE, Abreo E, Sams NP, et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: an analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) database. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70697. doi:10.7759/cureus.70697

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:e2034-e2039. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00127

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Rezaei SJ, Kim J, Onyeka S, et al. Skin cancer and other dermatologic conditions among US veterans. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3043

- Chang MS, La J, Trepanowski N, et al. Increased relative proportions of advanced melanoma among veterans: a comparative analysis with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.063

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957-959. doi:10.1126/science.1229259

- Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941-D947. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1015

- Li M, Gao X, Wang X. Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1090838. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1090838

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00073. doi:10.1200/PO.17.00073

- Lui AJ, Pagadala MS, Zhong AY, et al. Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the Million Veteran Program. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.06.14.23291413. doi:10.1101/2023.06.14.23291413

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499. doi:10.1002/cncr.31345

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J Oncol. 2022;2022:6300329. doi:10.1155/2022/6300329

- Whiteman DC, Stickley M, Watt P, et al. Anatomic site, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3172-3177. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1325

- Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:728-733. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903

- Gutiérrez-Castañeda LD, Nova JA, Tovar-Parra JD. Frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in different populations and histological subtypes of melanoma: a systemic review. Melanoma Res. 2020;30:62- 70. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000628

- Thielmann CM, Chorti E, Matull J, et al. NF1-mutated melanomas reveal distinct clinical characteristics depending on tumour origin and respond favourably to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.035

- D’Ecclesiis O, Caini S, Martinoli C, et al. Gender-dependent specificities in cutaneous melanoma predisposition, risk factors, somatic mutations, prognostic and predictive factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7945. doi:10.3390/ijerph18157945

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044

- Yu Z, Wang J, Feng L, et al. Association of tumor mutational burden with age in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e13590-e13590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e13590

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

Colorectal Cancer Characteristics and Mortality From Propensity Score-Matched Cohorts of Urban and Rural Veterans

Colorectal Cancer Characteristics and Mortality From Propensity Score-Matched Cohorts of Urban and Rural Veterans

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with an estimated 52,550 deaths in 2023.1 However, the disease burden varies among different segments of the population.2 While both CRC incidence and mortality have been decreasing due to screening and advances in treatment, there are disparities in incidence and mortality across the sociodemographic spectrum including race, ethnicity, education, and income.1-4 While CRC incidence is decreasing for older adults, it is increasing among those aged < 55 years.5 The incidence of CRC in adults aged 40 to 54 years has increased by 0.5% to 1.3% annually since the mid-1990s.6 The US Preventive Services Task Force now recommends starting CRC screening at age 45 years for asymptomatic adults with average risk.7

Disparities also exist across geographical boundaries and living environment. Rural Americans faces additional challenges in health and lifestyle that can affect CRC outcomes. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural residents are more likely to be older, have lower levels of education, higher levels of poverty, lack health insurance, and less access to health care practitioners (HCPs).8-10 Geographic proximity, defined as travel time or physical distance to a health facility, has been recognized as a predictor of inferior outcomes.11 These aspects of rural living may pose challenges for accessing care for CRC screening and treatment.11-13 National and local studies have shown disparities in CRC screening rates, incidence, and mortality between rural and urban populations.14-16

It is unclear whether rural/urban disparities persist under the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health care delivery model. This study examined differences in baseline characteristics and mortality between rural and urban veterans newly diagnosed with CRC. We also focused on a subpopulation aged ≤ 45 years.

Methods

This study extracted national data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) hosted in the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) environment. VINCI is an initiative to improve access to VA data and facilitate the analysis of these data while ensuring veterans’ privacy and data security.17 CDW is the VHA business intelligence information repository, which extracts data from clinical and nonclinical sources following prescribed and validated protocols. Data extracted included demographics, diagnosis, and procedure codes for both inpatient and outpatient encounters, vital signs, and vital status. This study used data previously extracted from a national cohort of veterans that encompassed all patients who received a group of commonly prescribed medications, such as statins, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 blockers, acetaminophen-containing products, and hydrocortisone-containing skin applications. This cohort encompassed 8,648,754 veterans, from whom 2,460,727 had encounters during fiscal years (FY) 2016 to 2021 (study period). The cohort was used to ensure that subjects were VHA patients, allowing them to adequately capture their clinical profiles.

Patients were identified as rural or urban based on their residence address at the date of their first diagnosis of CRC. The Geospatial Service Support Center (GSSC) aggregates and updates veterans’ residence address records for all enrolled veterans from the National Change of Address database. The data contain 1 record per enrollee. GSSC Geocoded Enrollee File contains enrollee addresses and their rurality indicators, categorized as urban, rural, or highly rural.18 Rurality is defined by the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) categories developed by the Department of Agriculture and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services.19 Urban areas had RUCA codes of 1.0 to 1.1, and highly rural areas had RUCA scores of 10.0. All other areas were classified as rural. Since the proportion of veterans from highly rural areas was small, we included residents from highly rural areas in the rural residents’ group.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All veterans newly diagnosed with CRC from FY 2016 to 2021 were included. We used the ninth and tenth clinical modification revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) to define CRC diagnosis (Supplemental materials).4,20 To ensure that patients were newly diagnosed with CRC, this study excluded patients with a previous ICD-9-CM code for CRC diagnosis since FY 2003.

Comorbidities were identified using diagnosis and procedure codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters, which were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) at the time of CRC diagnosis using the weighted method described by Schneeweiss et al.21 We defined CRC high-risk conditions and CRC screening tests, including flexible sigmoidoscopy and stool tests, as described in previous studies (Supplemental materials).20

The main outcome was total mortality. The date of death was extracted from the VHA Death Ascertainment File, which contains mortality data from the Master Person Index file in CDW and the Social Security Administration Death Master File. We used the date of death from any cause, as cause of death was not available.

A propensity score (PS) was created to match rural (including highly rural) and urban residents at a ratio of 1:1. Using a standard procedure described in prior publications, multivariable logistic regression used all baseline characteristics to estimate the PS and perform nearest-number matching without replacement.22,23 A caliper of 0.01 maximized the matched cohort size and achieved balance (Supplemental materials). We then examined the balance of baseline characteristics between PS-matched groups.

Analyses

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis estimated the hazard ratio (HR) of death in rural residents compared to urban residents in the PS-matched cohort. The outcome event was the date of death during the study’s follow-up period (defined as period from first CRC diagnosis to death or study end), with censoring at the study’s end date (September 30, 2021). The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by inspecting the Kaplan-Meier curves. Multiple analyses examined the HR of total mortality in the PS-matched cohort, stratified by sex, race, and ethnicity. We also examined the HR of total mortality stratified by duration of follow-up.

Another PS-matching analysis among veterans aged ≤ 45 years was performed using the same techniques described earlier in this article. We performed a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to compare mortality in PS-matched urban and rural veterans aged ≤ 45 years. The HR of death in all veterans aged ≤ 45 years (before PS-matching) was estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, adjusting for PS.

Dichotomous variables were compared using X2 tests and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Baseline characteristics with missing values were converted into categorical variables and the proportion of subjects with missing values was equalized between treatment groups after PS-matching. For subgroup analysis, we examined the HR of total mortality in each subgroup using separate Cox proportional hazards regression models similar to the primary analysis but adjusted for PS. Due to multiple comparisons in the subgroup analysis, the findings should be considered exploratory. Statistical tests were 2-tailed, and significance was defined as P < .05. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted from June 2022 to January 2023 using STATA, Version 17. The VA Orlando Healthcare System Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived requirements for informed consent because only deidentified data were used.

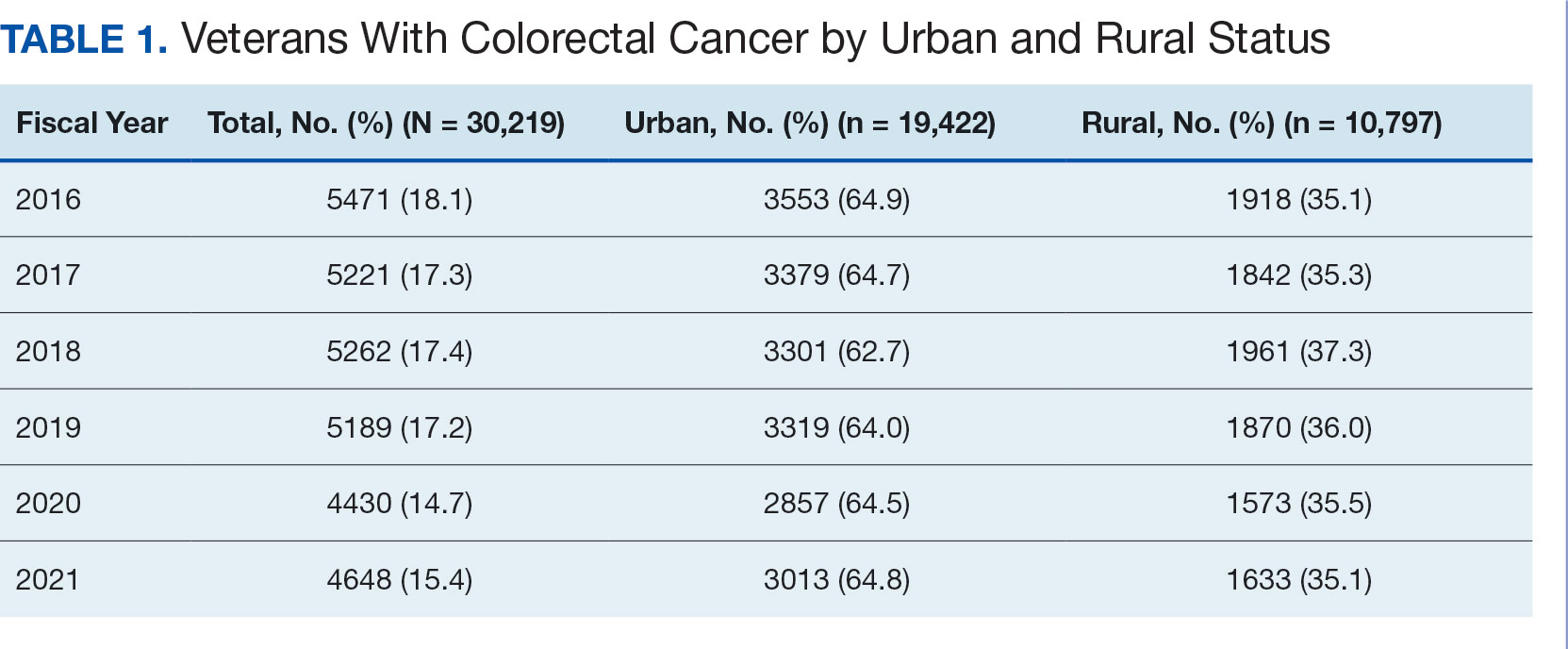

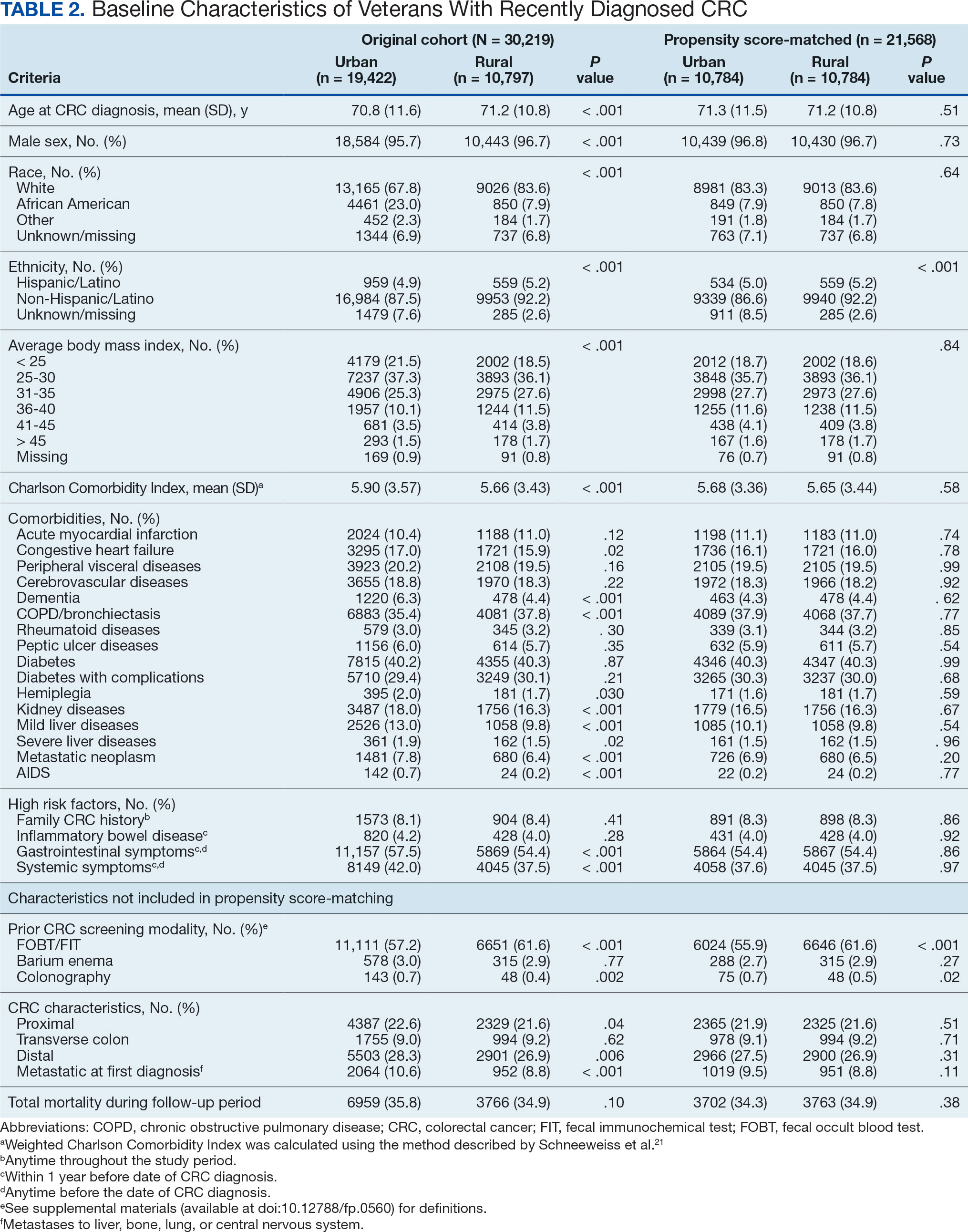

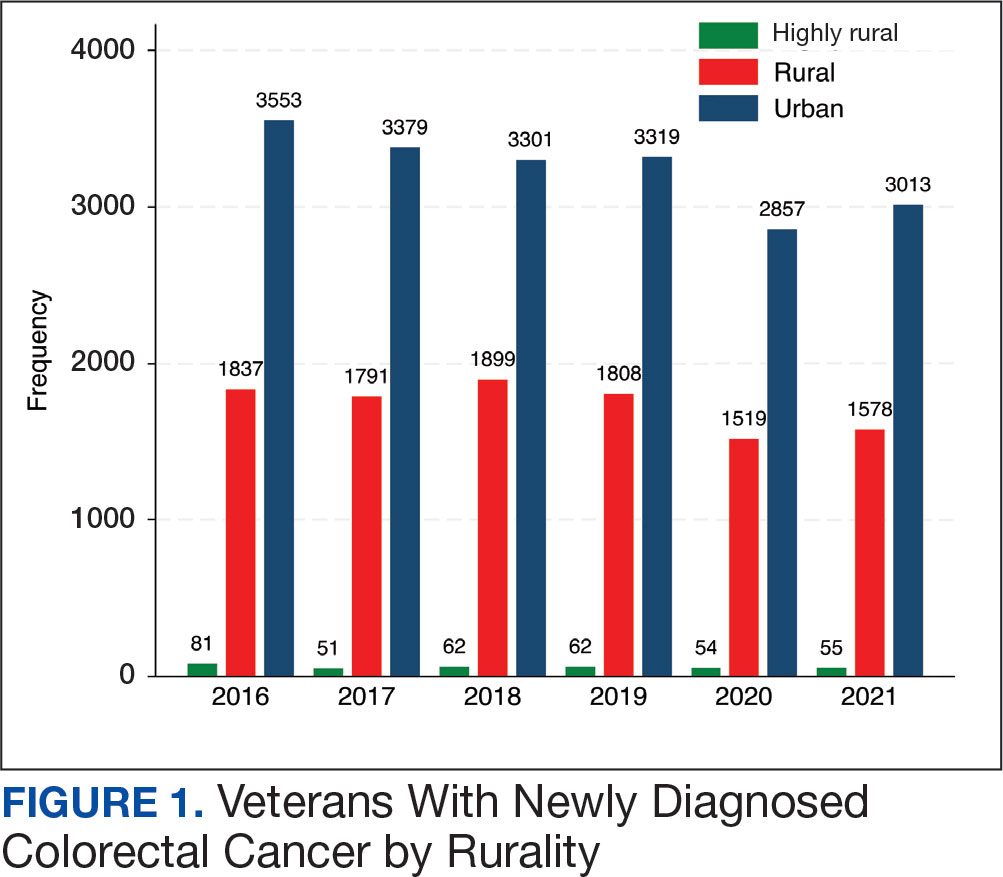

Results

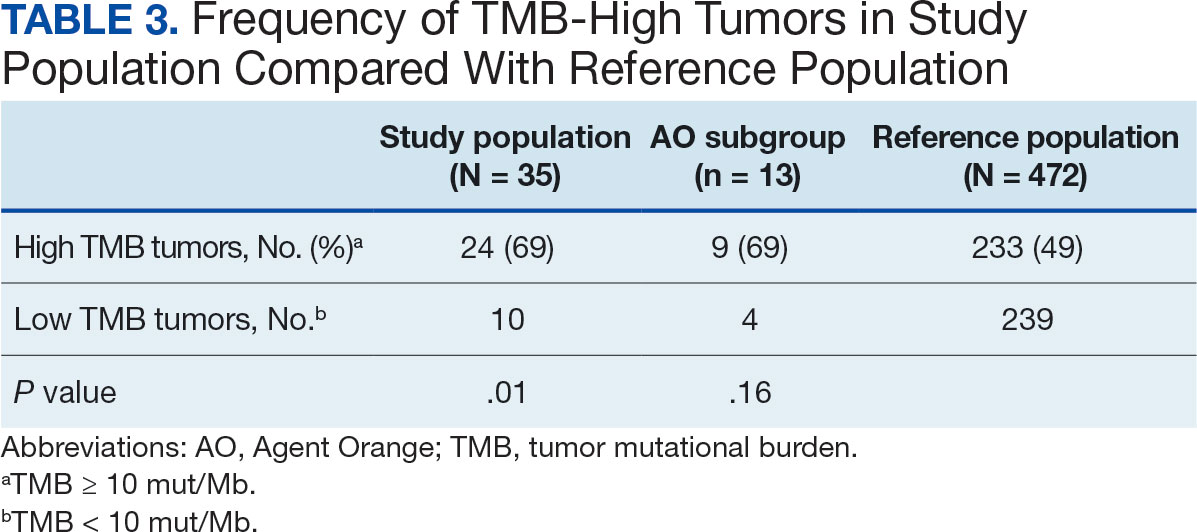

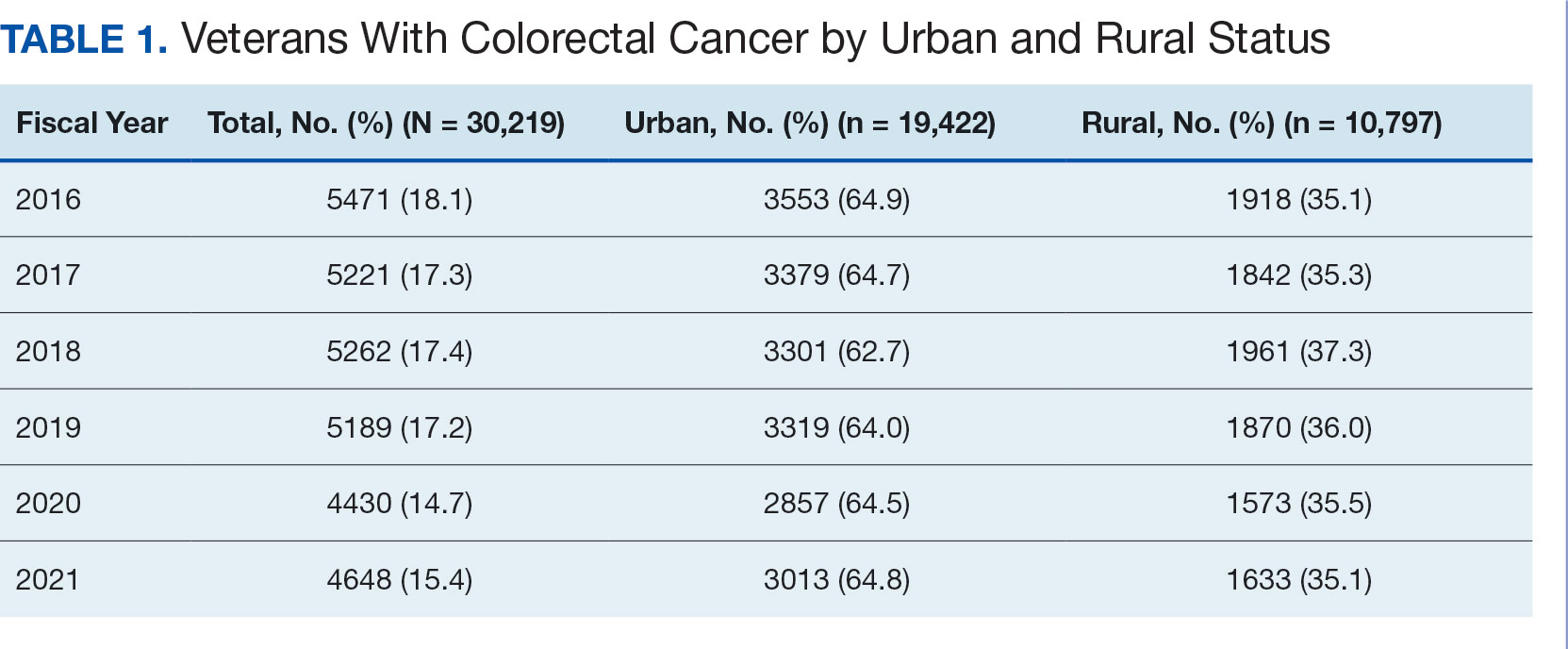

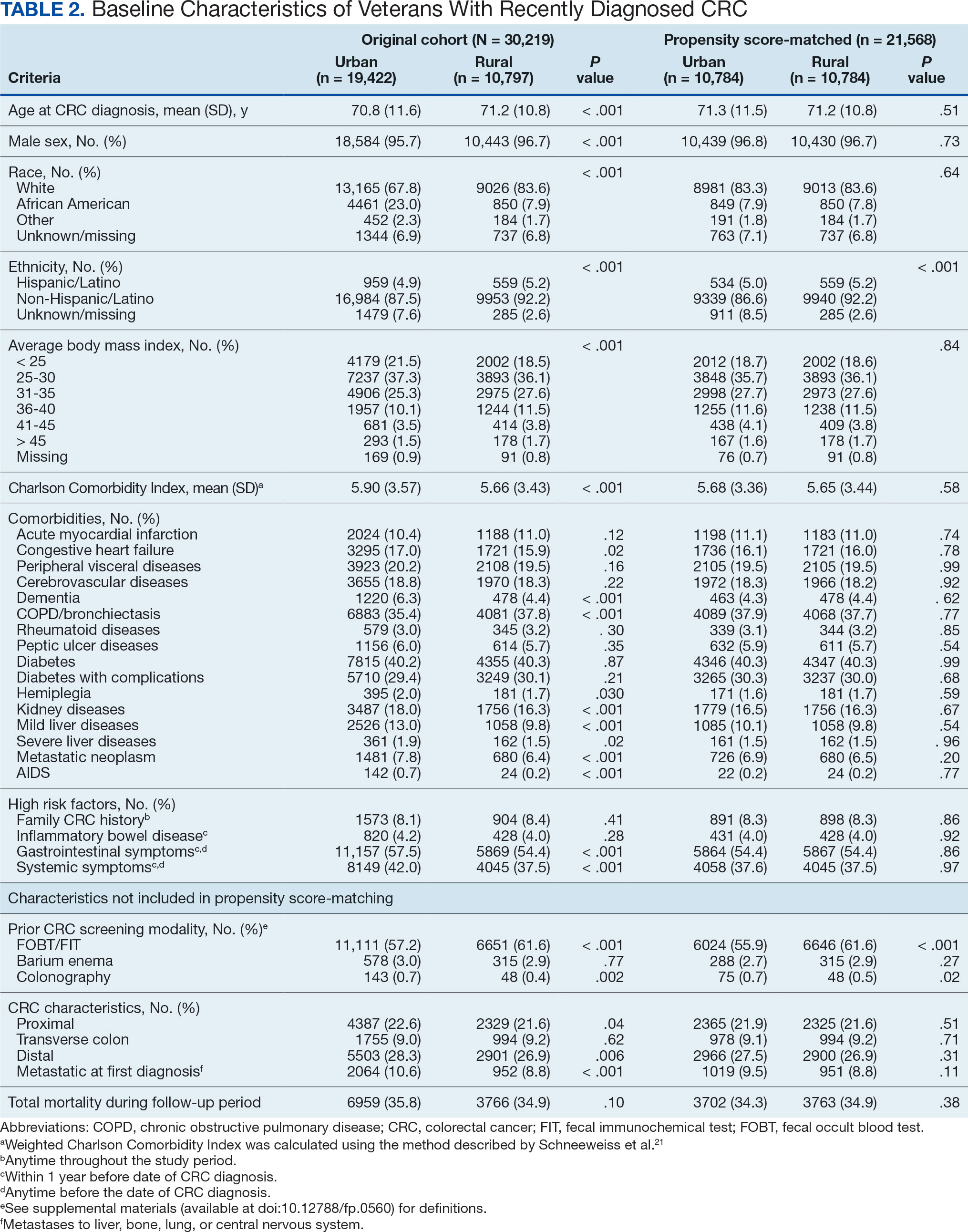

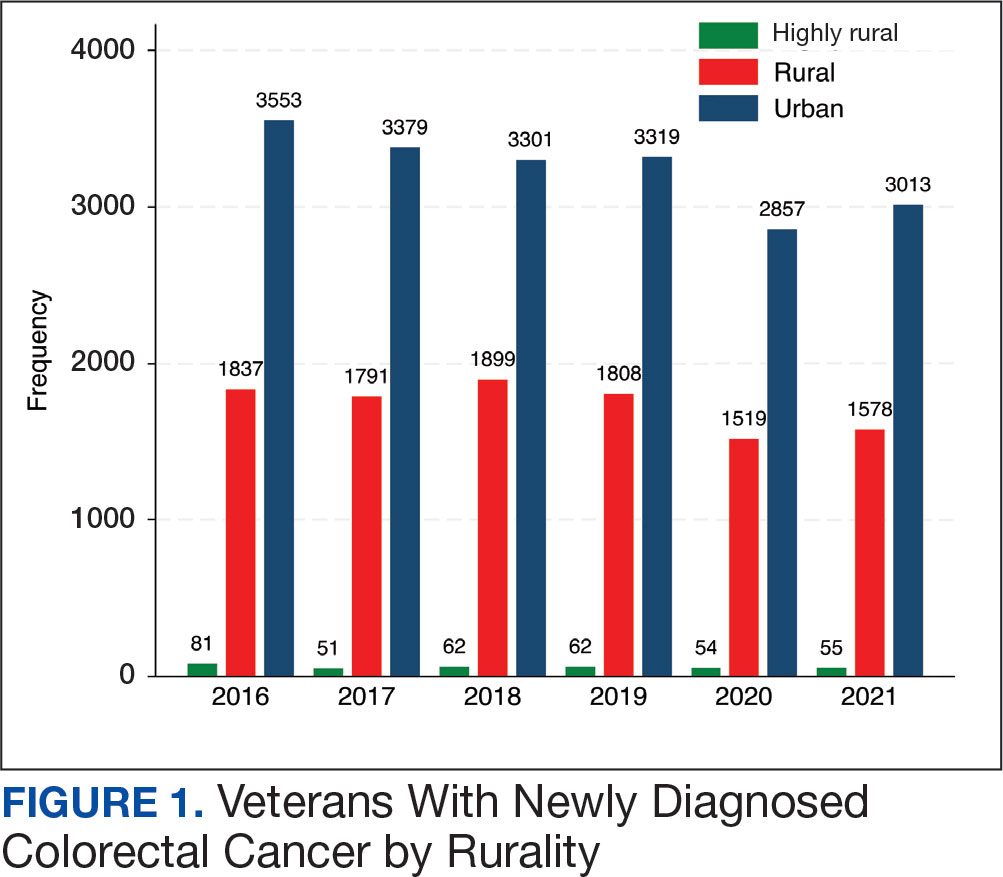

After excluding 49 patients (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0560), we identified 30,219 veterans with newly diagnosed CRC between FY 2016 to 2021 (Table 1). Of these, 19,422 (64.3%) resided in urban areas and 10,797 (35.7%) resided in rural areas (Table 2). The mean (SD) duration from the first CRC diagnosis to death or study end was 832 (640) days, and the median (IQR) was 723 (246–1330) days. Overall, incident CRC diagnoses were numerically highest in FY 2016 and lowest in FY 2020 (Figure 1). Patients with CRC in rural areas vs urban areas were significantly older (mean, 71.2 years vs 70.8 years, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be male (96.7% vs 95.7%, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be White (83.6% vs 67.8%, respectively; P < .001) and more likely to be non-Hispanic (92.2% vs 87.5%, respectively; P < .001). In terms of general health, rural veterans with CRC were more likely to be overweight or obese (81.5% rural vs 78.5% urban; P < .001) but had fewer mean comorbidities as measured by CCI (5.66 rural vs 5.90 urban; P < .001). A higher proportion of rural veterans with CRC had received stool-based (fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test) CRC screening tests (61.6% rural vs 57.2% urban; P < .001). Fewer rural patients presented with systemic symptoms or signs within 1 year of CRC diagnosis (54.4% rural vs 57.5% urban, P < .001). Among urban patients with CRC, 6959 (35.8%) deaths were observed, compared with 3766 (34.9%) among rural patients (P = .10).

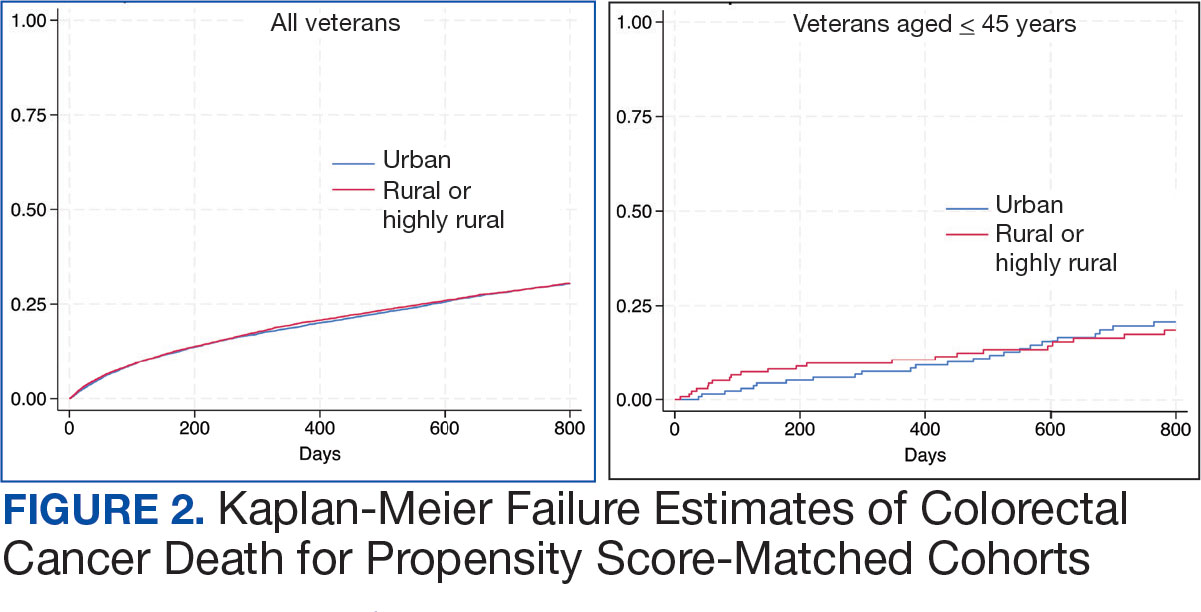

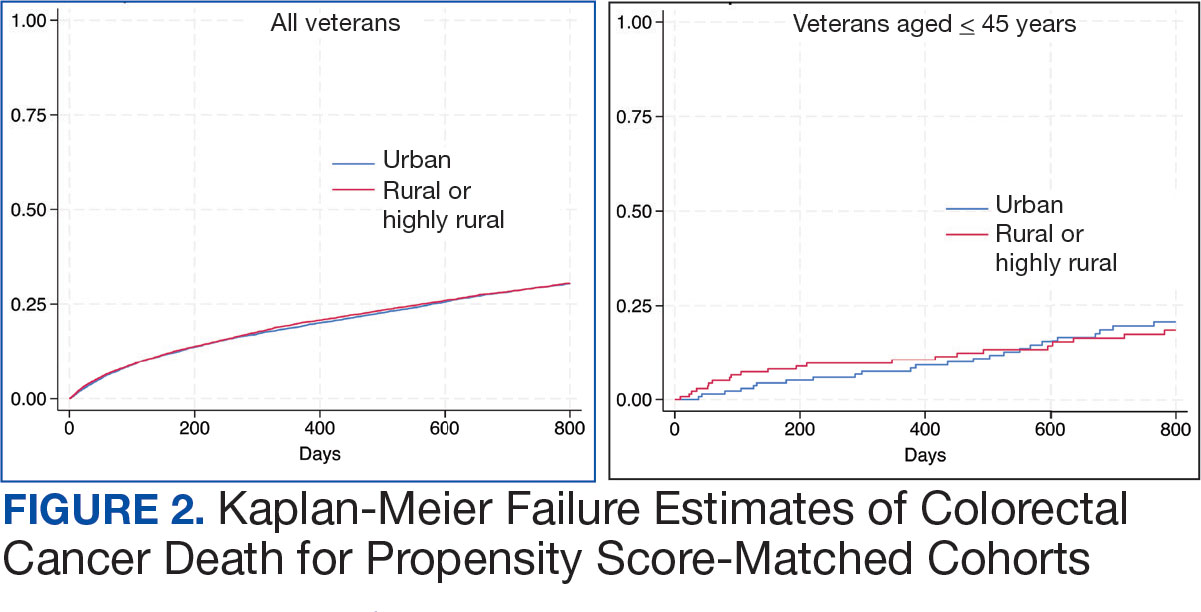

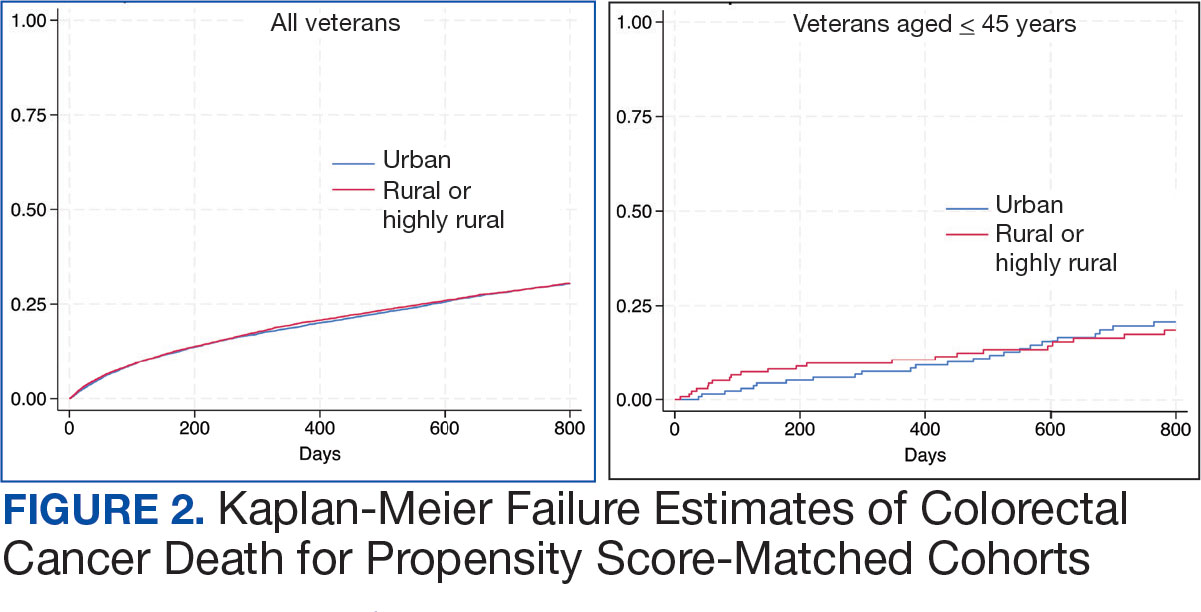

There were 21,568 PS-matched veterans: 10,784 in each group. In the PS-matched cohort, baseline characteristics were similar between veterans in urban and rural communities, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and comorbidities. Among rural patients with CRC, 3763 deaths (34.9%) were observed compared with 3702 (34.3%) among urban veterans. There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban CRC residents (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06; P = .53) (Figure 2).

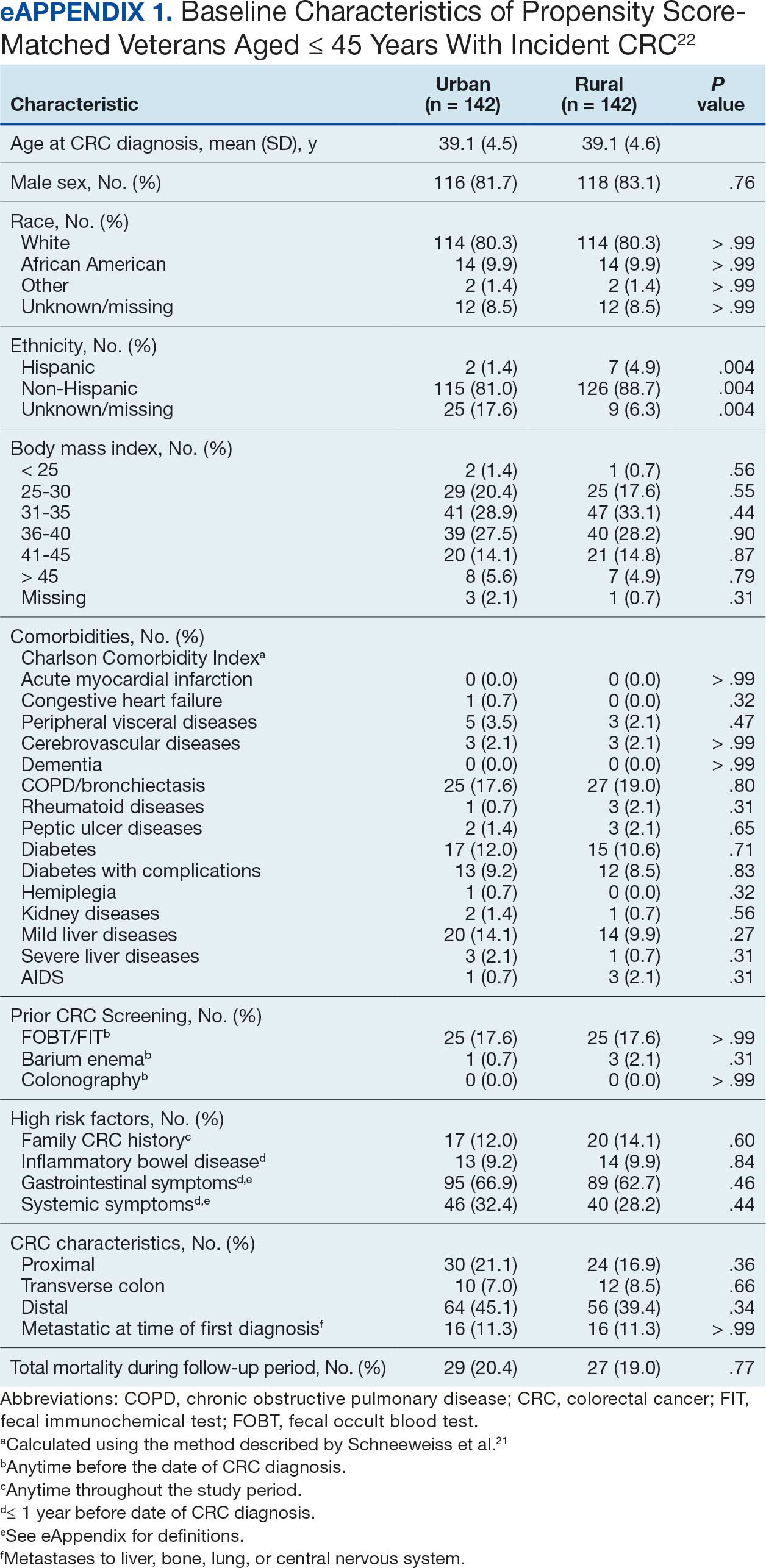

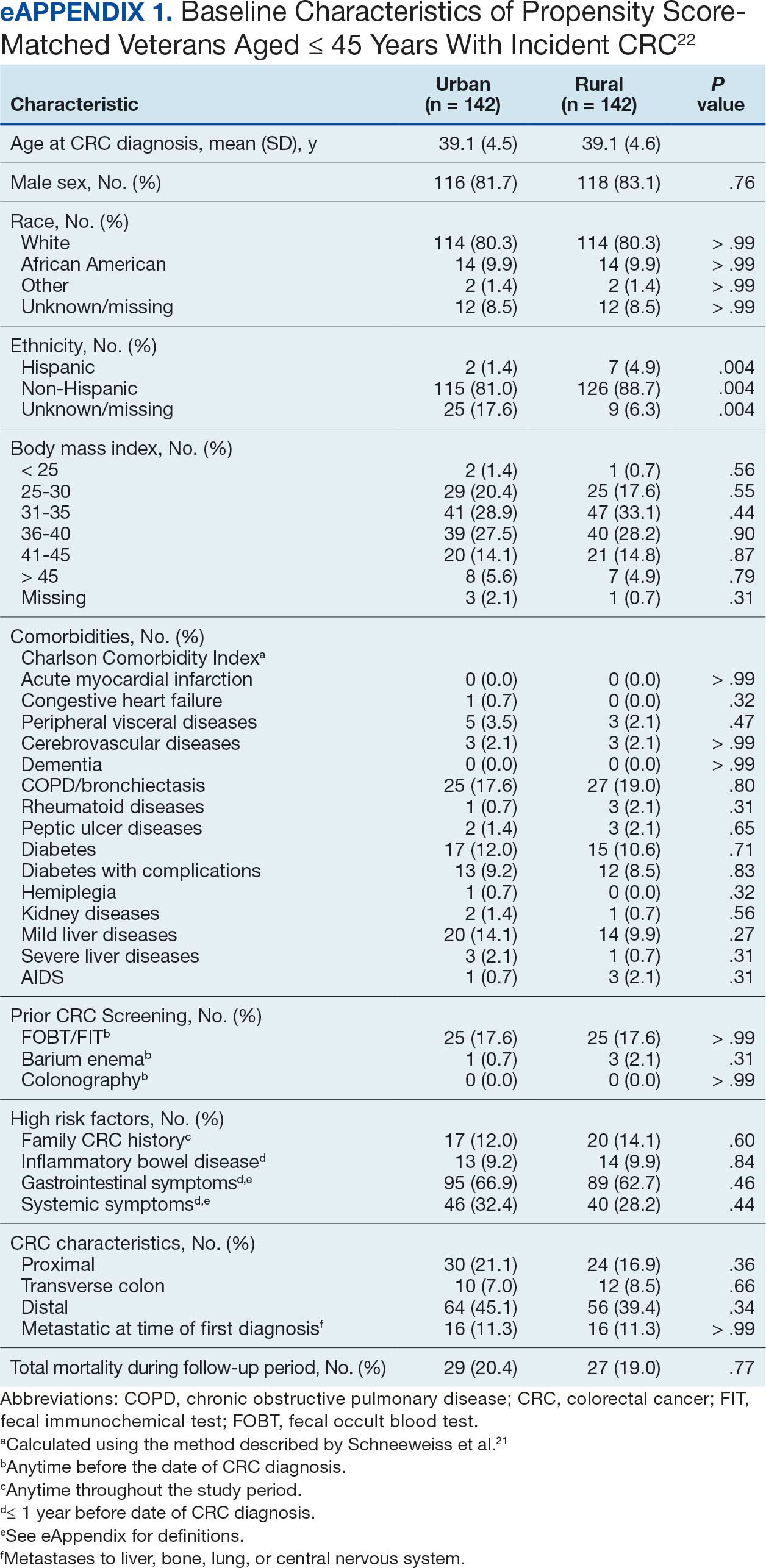

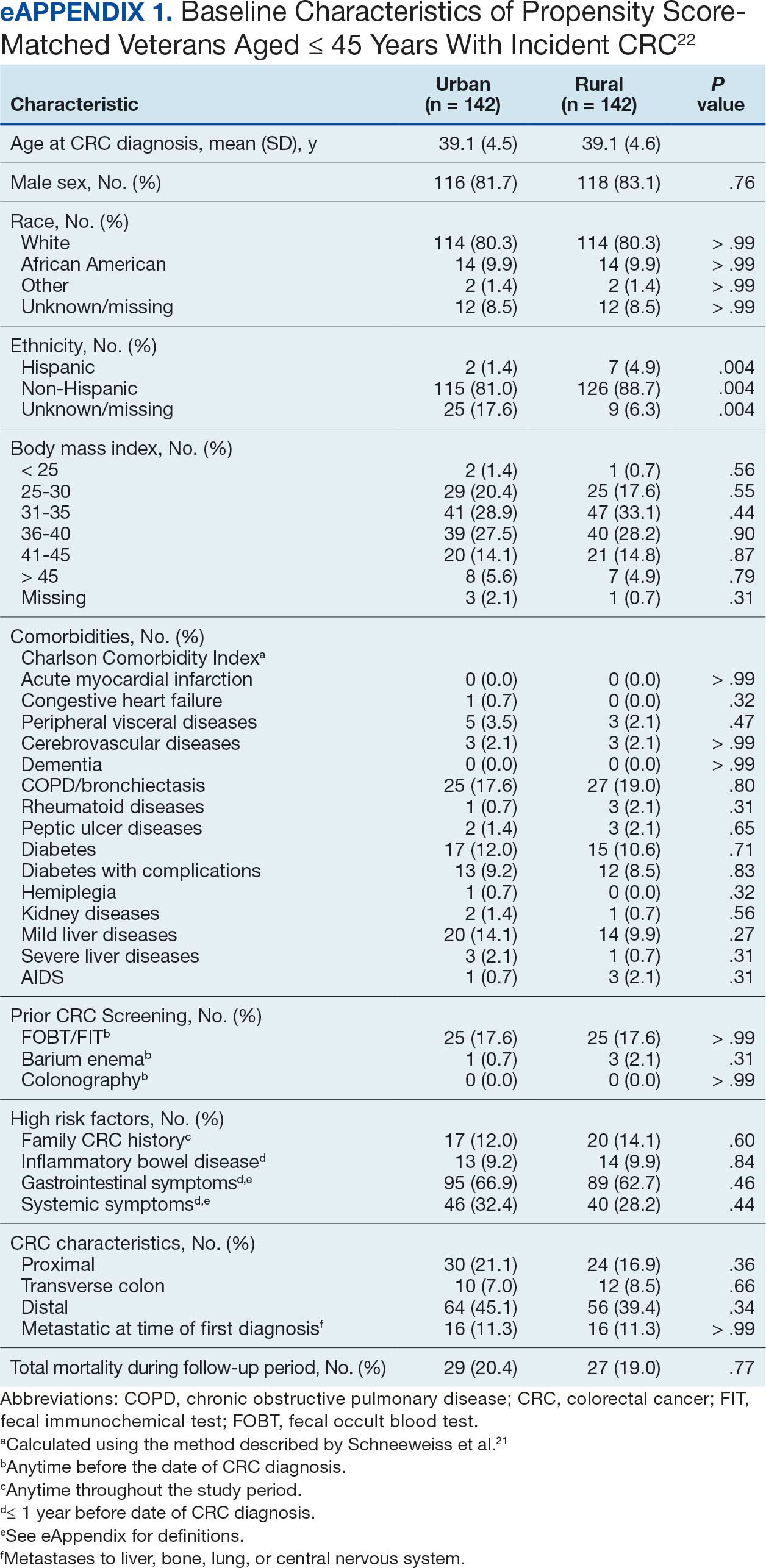

Among veterans aged ≤ 45 years, 551 were diagnosed with CRC (391 urban and 160 rural). We PS-matched 142 pairs of urban and rural veterans without residual differences in baseline characteristics (eAppendix 1). There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.57-1.63; P = .90) (Figure 2). Similarly, no difference in mortality was observed adjusting for PS between all rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.67-1.59; P = .88).

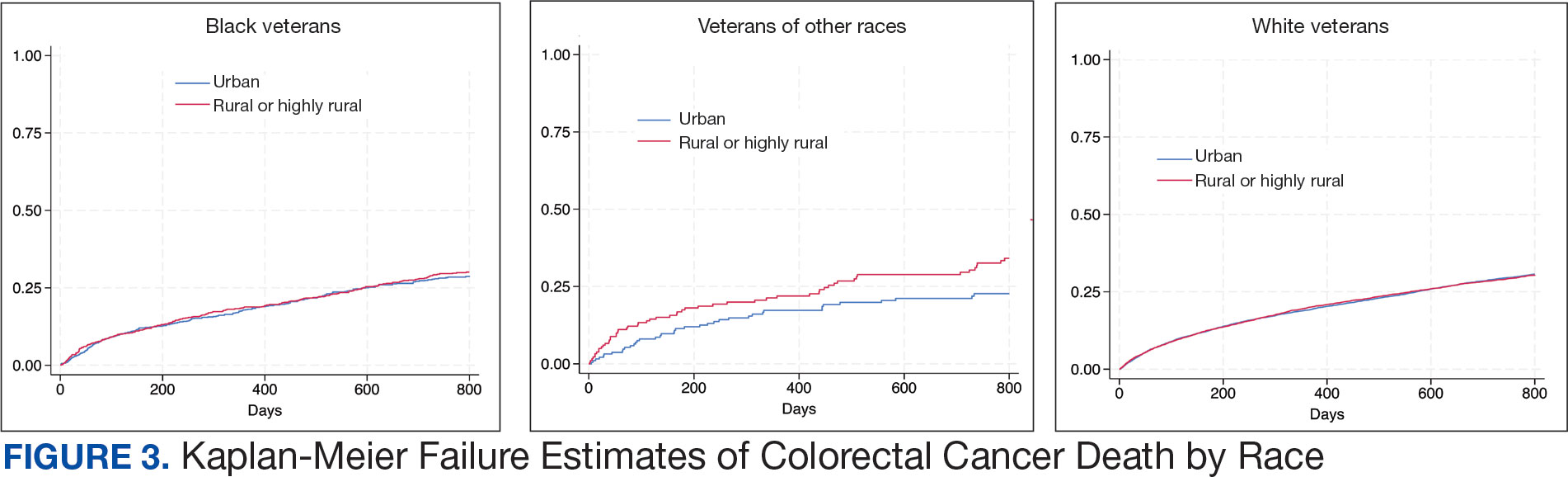

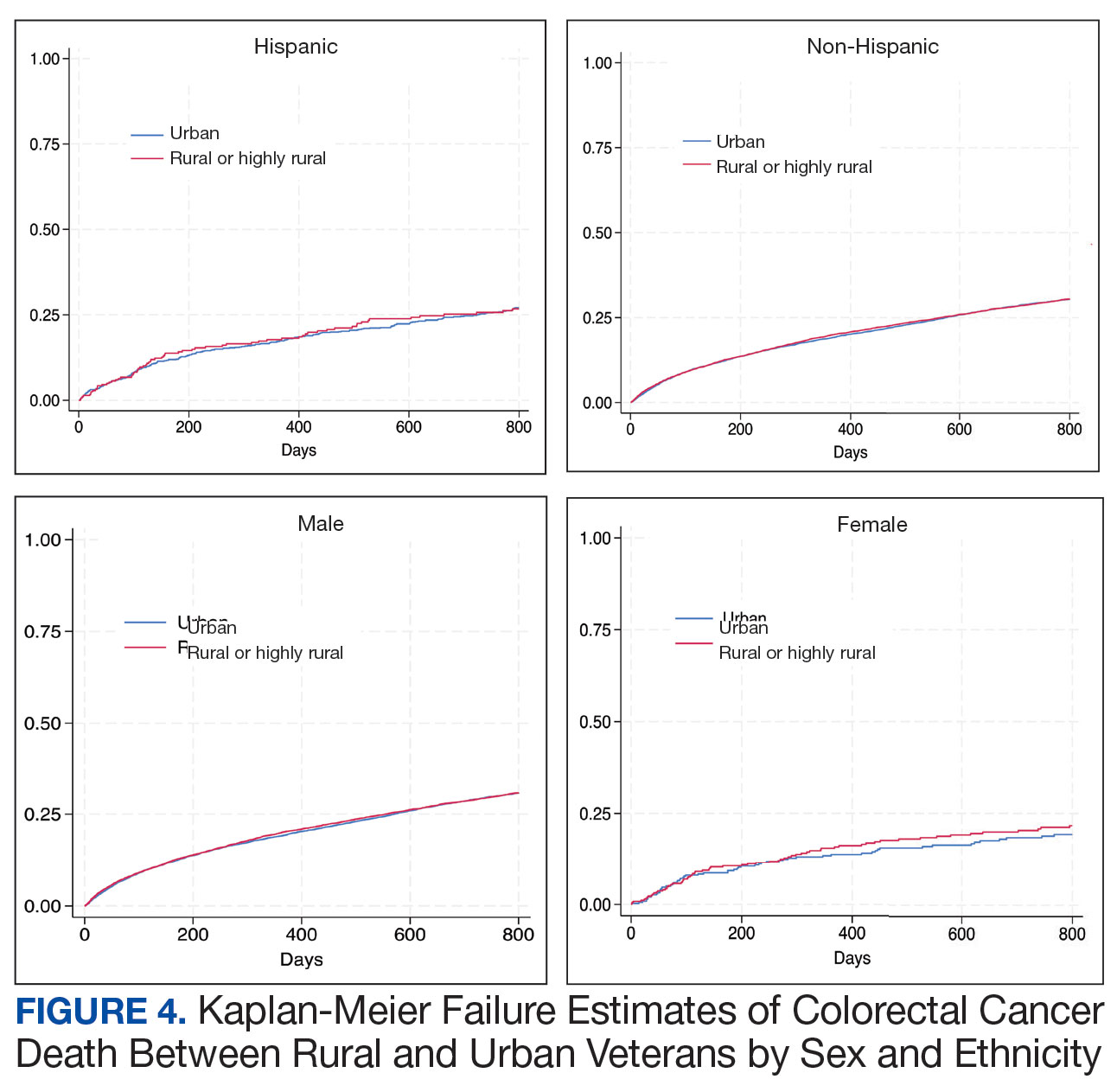

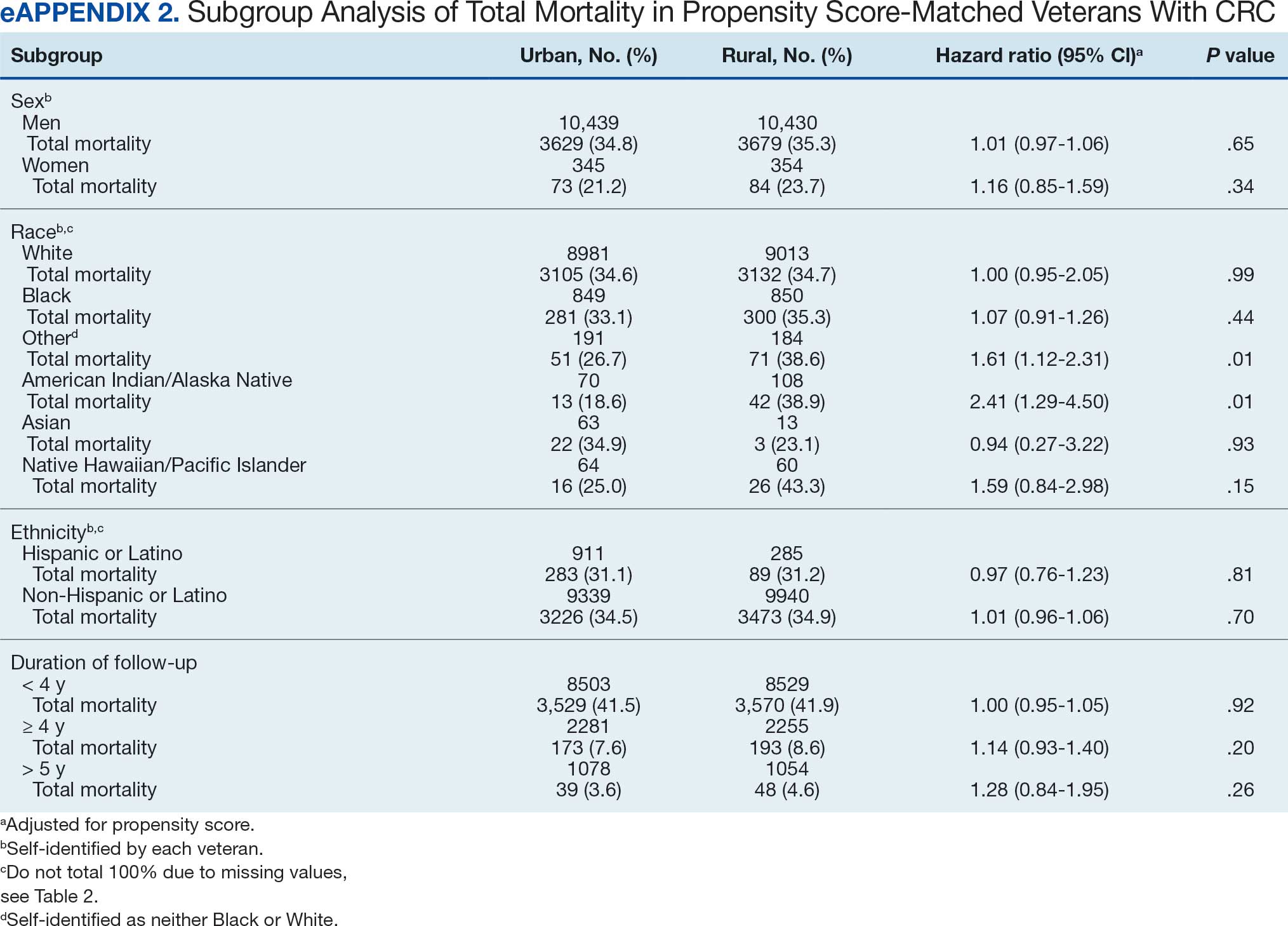

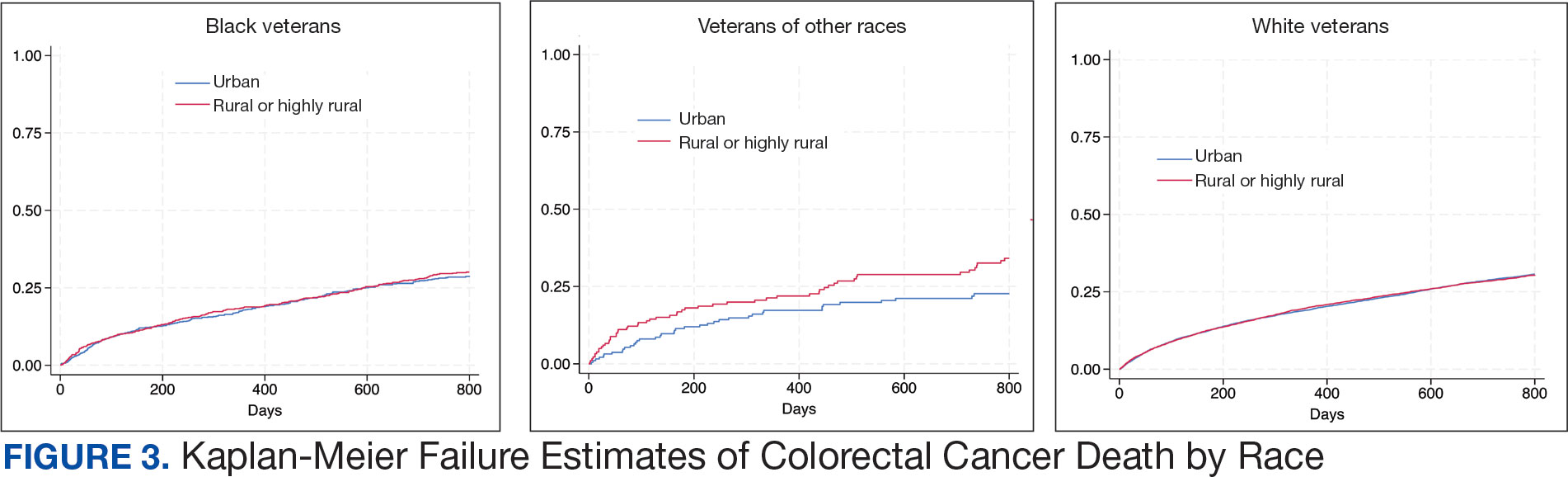

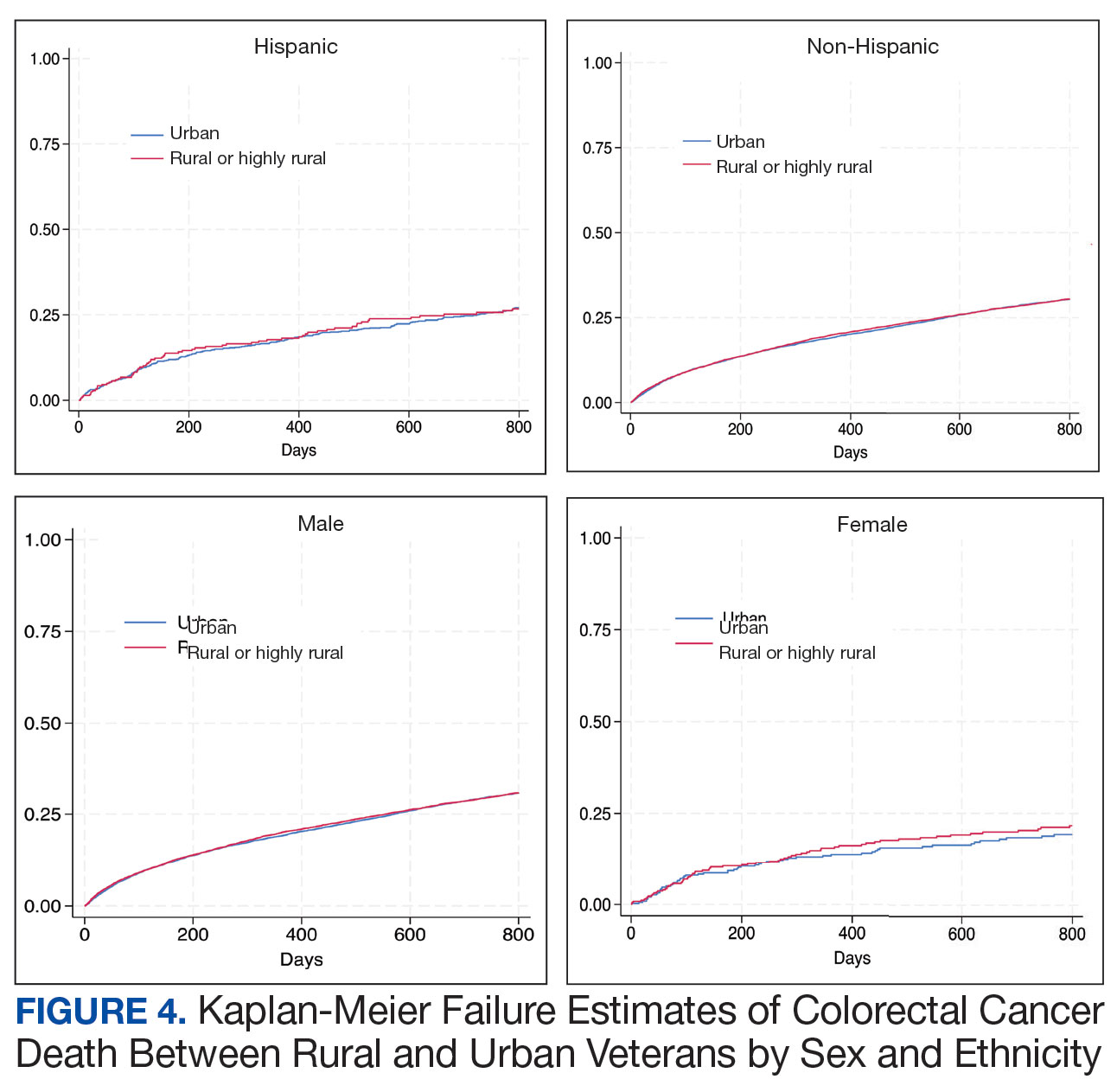

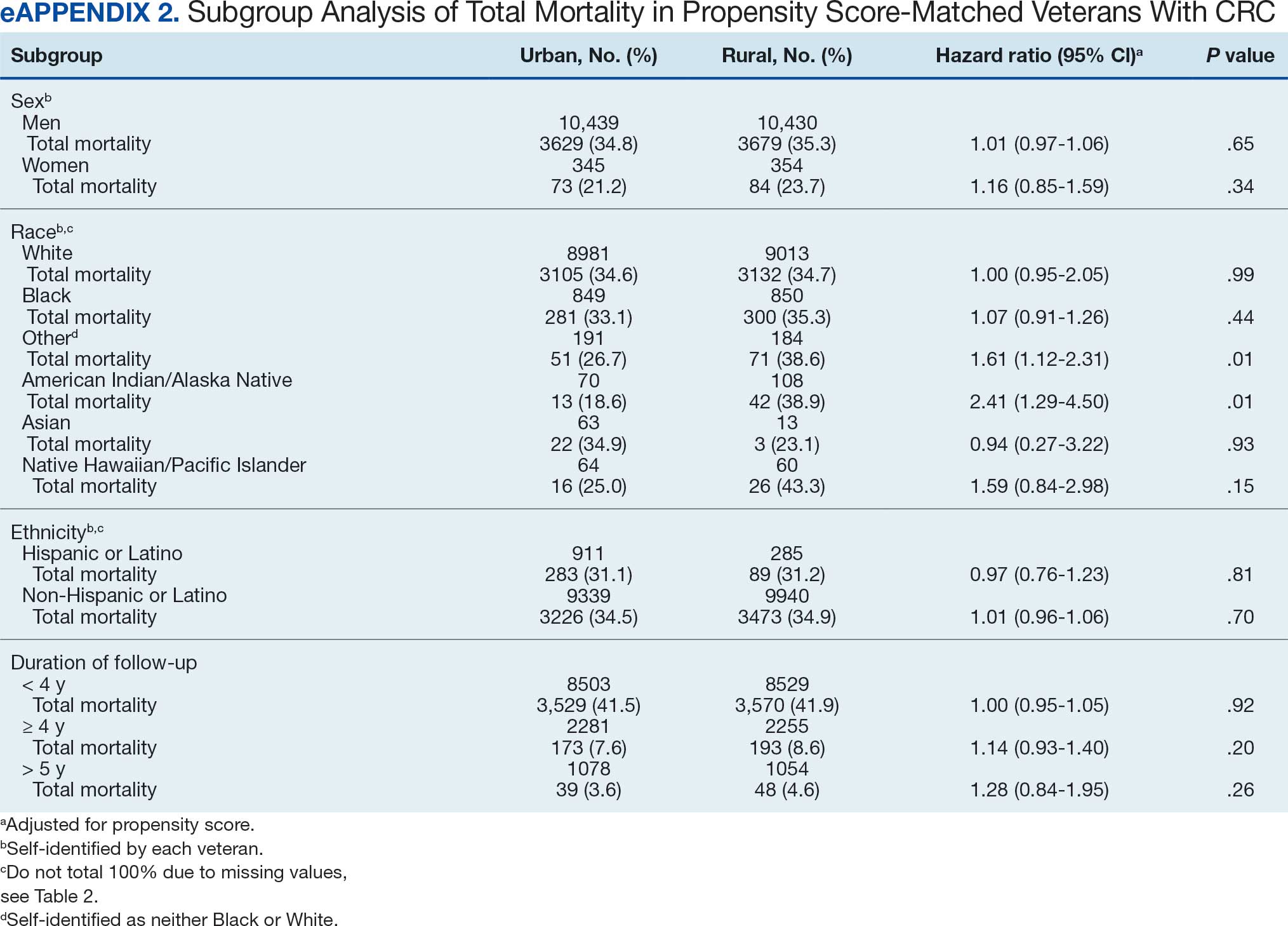

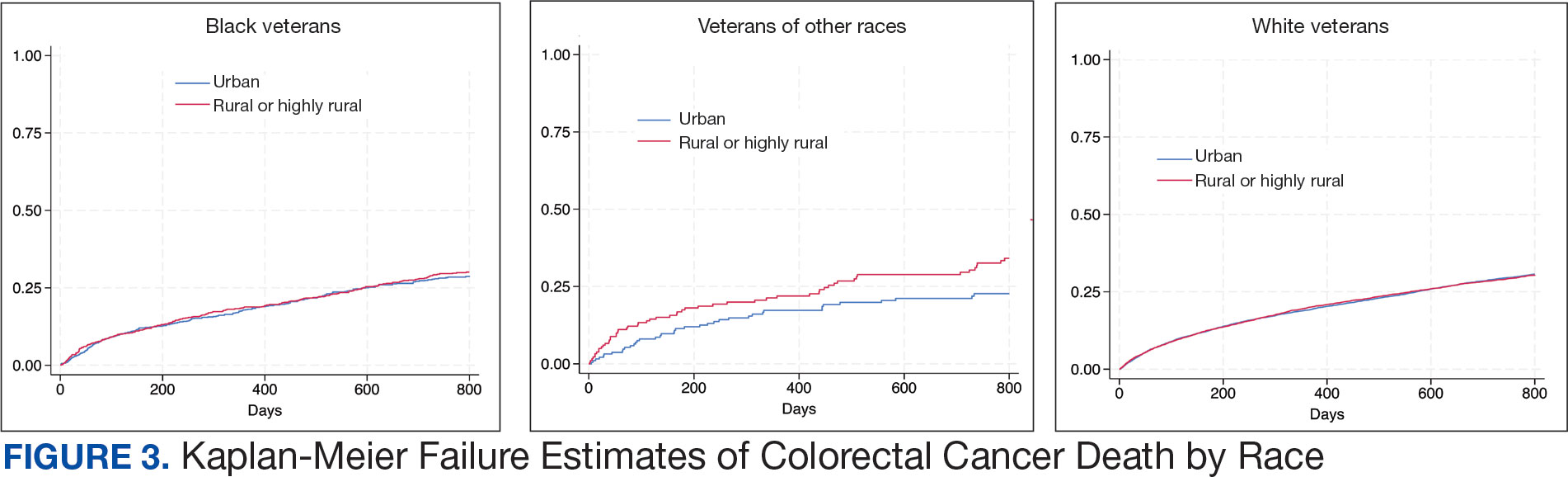

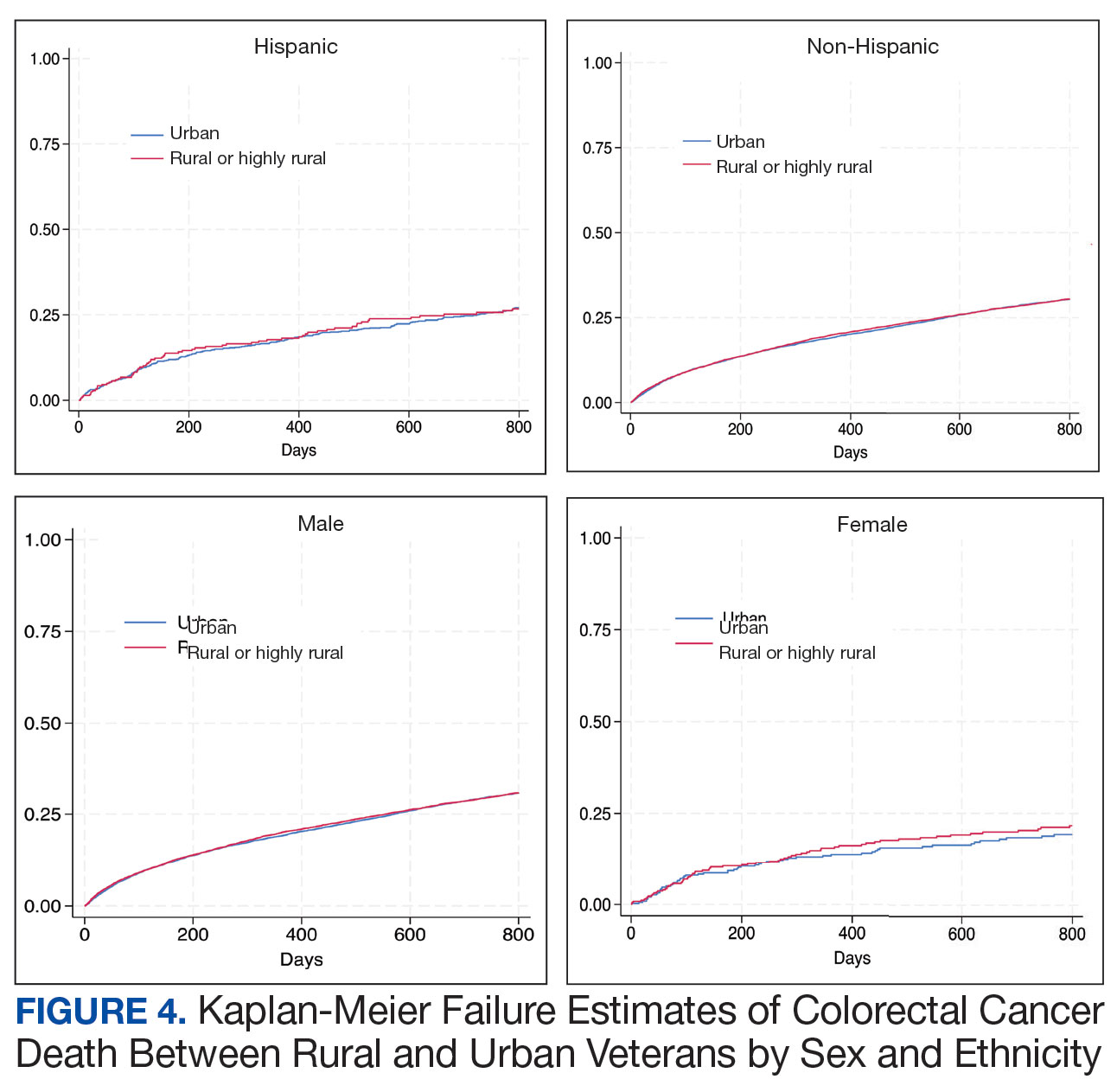

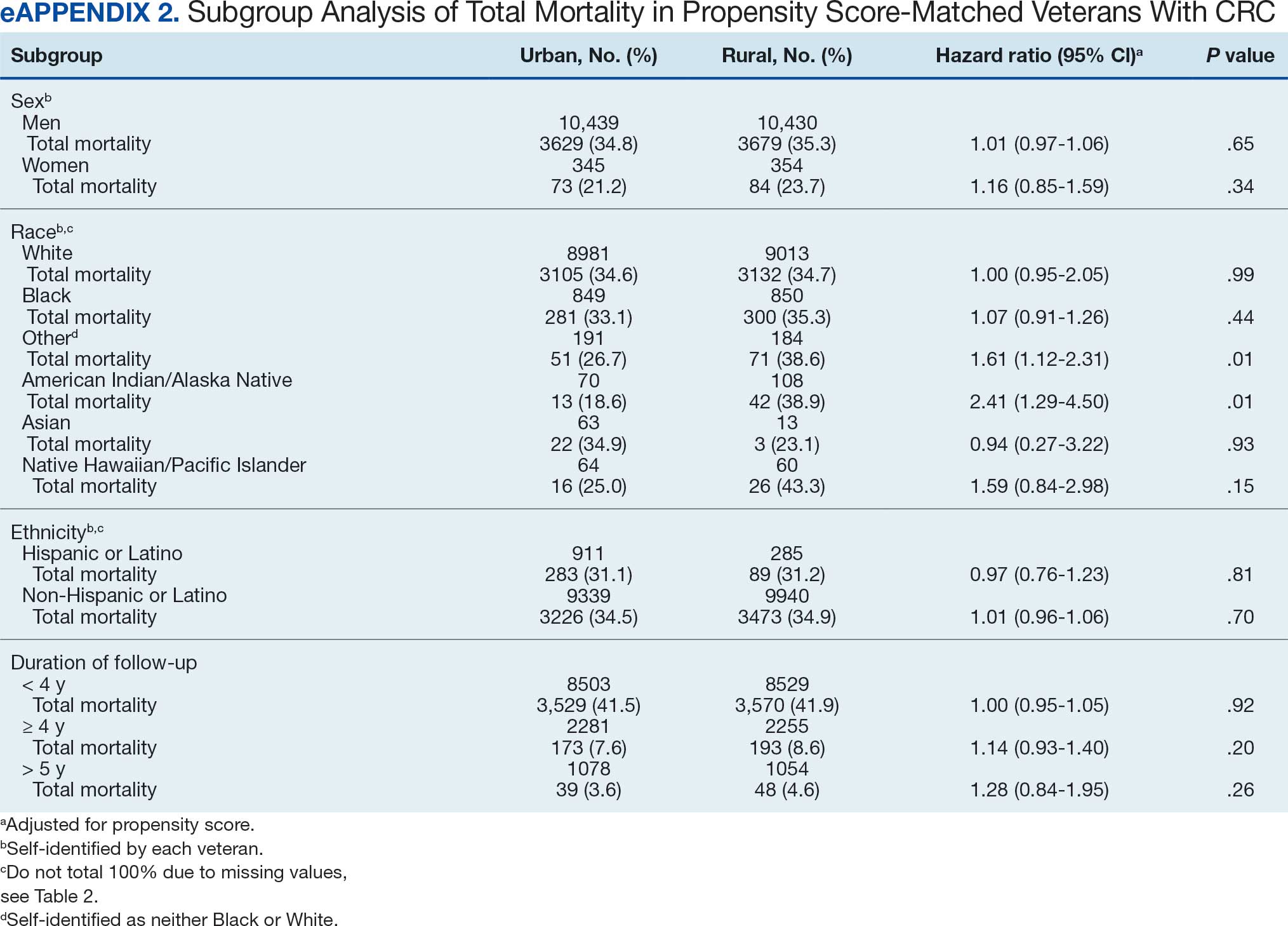

There was no difference in total mortality between rural and urban veterans in any subgroup except for American Indian or Alaska Native veterans (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006) (eAppendix 2).

Discussion

This study examined characteristics of patients with CRC between urban and rural areas among veterans who were VHA patients. Similar to other studies, rural veterans with CRC were older, more likely to be White, and were obese, but exhibited fewer comorbidities (lower CCI and lower incidence of congestive heart failure, dementia, hemiplegia, kidney diseases, liver diseases and AIDS, but higher incidence of chronic obstructive lung disease).8,16 The incidence of CRC in this study population was lowest in FY 2020, which was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is attributed to COVID-19 pandemic disruption of health services.24 The overall mortality in this study was similar to rates reported in other studies from the VA Central Cancer Registry.4 In the PS-matched cohort, where baseline characteristics were similar between urban and rural patients with CRC, we found no disparities in CRC-specific mortality between veterans in rural and urban areas. Additionally, when analysis was restricted to veterans aged ≤ 45 years, the results remained consistent.

Subgroup analyses showed no significant difference in mortality between rural and urban areas by sex, race or ethnicity, except rural American Indian or Alaska Native veterans who had double the mortality of their urban counterparts (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006). This finding is difficult to interpret due to the small number of events and the wide CI. While with a Bonferroni correction the adjusted P value was .08, which is not statistically significant, a previous study found that although CRC incidence was lower overall in American Indian or Alaska Native populations compared to non-Hispanic White populations, CRC incidence was higher among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals in some areas such as Alaska and the Northern Plains.25,26 Studies have noted that rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations experience greater poverty, less access to broadband internet, and limited access to care, contributing to poorer cancer outcomes and lower survival.27 Thus, the finding of disparity in mortality between rural and urban American Indian or Alaska Native veterans warrants further study.

Other studies have raised concerns that CRC disproportionately affects adults in rural areas with higher mortality rates.14-16 These disparities arise from sociodemographic factors and modifiable risk factors, including physical activity, dietary patterns, access to cancer screening, and gaps in quality treatment resources.16,28 These factors operate at multiple levels: from individual, local health system, to community and policy.2,27 For example, a South Carolina study (1996–2016) found that residents in rural areas were more likely to be diagnosed with advanced CRC, possibly indicating lower rates of CRC screening in rural areas. They also had higher likelihood of death from CRC.15 However, the study did not include any clinical parameters, such as comorbidities or obesity. A statewide, population-based study in Utah showed that rural men experienced a lower CRC survival in their unadjusted analysis.16 However, the study was small, with only 3948 urban and 712 rural residents. Additionally, there was no difference in total mortality in the whole cohort (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07) or in CRC-specific death (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.08). A nationwide study also showed that CRC mortality rates were 8% higher in nonmetropolitan or rural areas than in the most urbanized areas containing large metropolitan counties.29 However, this study did not include descriptions of clinical confounders, such as comorbidities, making it difficult to ascertain whether the difference in CRC mortality was due to rurality or differences in baseline risk characteristics.

In this study, the lack of CRC-specific mortality disparities may be attributed to the structures and practices of VHA health care. Recent studies have noted that mortality of several chronic medical conditions treated at the VHA was lower than at non-VHA hospitals.30,31 One study that measured the quality of nonmetastatic CRC care based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines showed that > 72% of VHA patients received guideline-concordant care for each diagnostic and therapeutic measure, except for follow-up colonoscopy timing, which appear to be similar or superior to that of the private sector.30,32,33 Some of the VA initiative for CRC screening may bypass the urban-rurality divide such as the mailed fecal immunochemical test program for CRC. This program was implemented at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid disruptions of medical care.34 Rural patients are more likely to undergo fecal immunochemical testing when compared to urban patients in this data. Beyond clinical care, the VHA uses processes to tackle social determinants of health such as housing, food security, and transportation, promoting equal access to health care, and promoting cultural competency among HCPs.35-37

The results suggest that solutions to CRC disparities between rural and urban areas need to consider known barriers to rural health care, including transportation, diminished rural health care workforce, and other social determinants of health.9,10,27,38 VHA makes considerable efforts to provide equitable care to all enrolled veterans, including specific programs for rural veterans, including ongoing outreach.39 This study demonstrated lack of disparity in CRC-specific mortality in veterans receiving VHA care, highlighting the importance of these efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

This study used the VHA cohort to compare patient characteristics and mortality between patients with CRC residing in rural and urban areas. The study provides nationwide perspectives on CRC across the geographical spectrum and used a longitudinal cohort with prolonged follow-up to account for comorbidities.

However, the study compared a cohort of rural and urban veterans enrolled in the VHA; hence, the results may not reflect CRC outcomes in veterans without access to VHA care. Rurality has been independently associated with decreased likelihood of meeting CRC screening guidelines among veterans and military service members.38 This study lacked sufficient information to compare CRC staging or treatment modalities among veterans. Although the data cannot identify CRC stage, the proportions of patients with metastatic CRC at diagnosis and CRC location were similar between groups. The study did not have information on their care outside of VHA setting.

This study could not ascertain whether disparities existed in CRC treatment modality since rural residence may result in referral to community-based CRC care, which did not appear in the data. To address these limitations, we used death from any cause as the primary outcome, since death is a hard outcome and is not subject to ascertainment bias. The relatively short follow-up time is another limitation, though subgroup analysis by follow-up did not show significant differences. Despite PS matching, residual unmeasured confounding may exist between urban and rural groups. The predominantly White, male VHA population with high CCI may limit the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

Rural VHA enrollees had similar survival rates after CRC diagnosis compared to their urban counterparts in a PS-matched analysis. The VHA models of care—including mailed CRC screening tools, several socioeconomic determinants of health (housing, food security, and transportation), and promoting equal access to health care, as well as cultural competency among HCPs—HCPs—may help alleviate disparities across the rural-urban spectrum. The VHA should continue efforts to enroll veterans and provide comprehensive coordinated care in community partnerships.

- Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254. doi:10.3322/caac.21772

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):354-367. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029

- Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, Inskip PD, McGlynn KA, Cook MB. Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1668-75. doi:10.1002/ijc.25481

- Zullig LL, Smith VA, Jackson GL, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics from the Veterans Affairs central cancer registry. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15(4):e199-e204. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2016.04.005

- Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 2021. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews:Chapter 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570917/

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

- Hines R, Markossian T, Johnson A, Dong F, Bayakly R. Geographic residency status and census tract socioeconomic status as determinants of colorectal cancer outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e63-e71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301572

- Cauwels J. The many barriers to high-quality rural health care. 2022;(9):1-32. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.22.0254

- Gong G, Phillips SG, Hudson C, Curti D, Philips BU. Higher US rural mortality rates linked to socioeconomic status, physician shortages, and lack of health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood);38(12):2003-2010. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00722

- Aboagye JK, Kaiser HE, Hayanga AJ. Rural-urban differences in access to specialist providers of colorectal cancer care in the United States: a physician workforce issue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):537-543. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5062

- Lyckholm LJ, Hackney MH, Smith TJ. Ethics of rural health care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40(2):131-138. doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00139-1

- Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341-378. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341