User login

Summertime and Mosquitoes Are Breeding

There are over 3700 types of mosquitoes worldwide and over 200 types in the continental United States, of which only 12 are associated with transmitting diseases to humans. The majority are just a nuisance. Since they cannot readily be distinguished, strategies to prevent any bites are recommended.

West Nile Virus

In the US, West Nile virus (WNV) is the leading cause of neuroinvasive arboviral disease. Just hearing the name took me back to New York in 1999 when sightings of dead birds around the city and boroughs were reported daily. The virus was isolated that same year. The enzootic circle occurs between mosquitoes and birds, which are the primary vertebrate host via the bite of Culex mosquitoes. After a bite from an infected mosquito, humans are usually a dead-end host since the level and duration of viremia needed to infect another mosquito is insufficient.

Human-to-human transmission is documented through blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation. Vertical transmission is rarely described. Initially isolated in New York, WNV quickly spread across North America and has been isolated in every continent except Antarctica. Most cases occur in the summer and autumn.

Most infected individuals are asymptomatic. Those who do develop symptoms have fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, and a transient rash. Less than 1% develop meningitis/encephalitis symptoms similar to other causes of aseptic meningitis. Those with encephalitis in addition to fever and headache may have altered mental status and focal neurologic deficits including flaccid paralysis or movement disorders.

Detection of anti-WNV IgM antibodies (AB) in serum or CSF is the most common way to make the diagnosis. IgM AB usually is present within 3-8 days after onset of symptoms and persists up to 90 days. Data from ArboNET, the national arboviral surveillance system managed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments, reveal that from 1999 to 2022 there were 56,575 cases of WNV including 28,684 cases of neuroinvasive disease. In 2023 there were 2,406 and 1,599 cases, respectively. Those historic totals for WNV are 10 times greater than the totals for all the other etiologies of neuroinvasive arboviral diseases in the US combined (Jamestown Canyon, LaCrosse, St. Louis, and Eastern Equine encephalitis n = 1813).

Remember to include WNV in your differential of a febrile patient with neurologic symptoms, mosquito bites, blood transfusions, and organ transplantation. Treatment is supportive care.

The US began screening all blood donations for WNV in 2003. Organ donor screening is not universal.

Dengue

Dengue, another arbovirus, is transmitted by bites of infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, which prefer to feed during the daytime. There are four dengue virus serotypes: DENV-1 DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. In endemic areas, all four serotypes are usually co-circulating and people can be infected by each one.

Long-term immunity is type specific. Heterologous protection lasts only a few months. Dengue is endemic throughout the tropics and subtropics of Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Approximately 53% of the world’s population live in an area where dengue transmission can occur. In the US, most cases are reported from Puerto Rico. Dengue is endemic in the following US territories: Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and free associated states. Most cases reported on the mainland are travel related. However, locally acquired dengue has been reported. From 2010 to 2023 Hawaii reported 250 cases, Florida 438, and Texas 40 locally acquired cases. During that same period, Puerto Rico reported more than 32,000 cases. It is the leading cause of febrile illness for travelers returning from the Caribbean, Latin America, and South Asia. Peru is currently experiencing an outbreak with more than 25,000 cases reported since January 2024. Most cases of dengue occur in adolescents and young adults. Severe disease occurs most often in infants, those with underlying chronic disease, pregnant women, and persons infected with dengue for the second time.

Symptoms range from a mild febrile illness to severe disease associated with hemorrhage and shock. Onset is usually 7-10 days after infection and symptoms include high fever, severe headache, retro-orbital pain, arthralgia and myalgias, nausea, and vomiting; some may develop a generalized rash.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies dengue as 1) dengue with or without warning signs for progression of disease and 2) severe dengue. Warning signs for disease progression include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, fluid accumulation (e.g., ascites, pericardial or pleural effusion), mucosal bleeding, restlessness, postural hypotension, liver enlargement greater than 2 cm. Severe dengue is defined as any sign of severe plasma leakage leading to shock, severe bleeding or organ failure, or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress. Management is supportive care.

Prevention: In the US, Dengvaxia, a live attenuated tetravalent vaccine, is approved for use in children aged 9–16 years with laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and living in areas where dengue is endemic. It is administered at 0, 6, and 12 months. It is not available for purchase on the mainland. Continued control of the vector and personal protection is necessary to prevent recurrent infections.

CHIKV

Chikungunya (CHIKV), which means “that which bends up” in the Mkonde language of Tanzania, refers to the appearance of the person with severe usually symmetric arthralgias characteristic for this infection that otherwise is often clinically confused with dengue and Zika. It too is transmitted by A. aegypti and A. albopictus and is prevalent in tropical Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Like dengue it is predominantly an urban disease. The WHO reported the first case in the Western Hemisphere in Saint Martin in December 2013. By August 2014, 31 additional territories and Caribbean or South American countries reported 576,535 suspected cases. Florida first reported locally acquired CHIKV in June 2014. By December an additional 11 cases had been identified. Texas reported one case in 2015. Diagnosis is with IgM ab or PCR. Treatment is supportive with most recovering from acute illness within 2 weeks. Data in adults indicate 40-52% may develop chronic or recurrent joint pain.

Prevention: IXCHIQ, a live attenuated vaccine, was licensed in November 2023 and recommended by the CDC in February 2024 for use in persons at least 18 years of age with travel to destinations where there is a CHIKV outbreak. It may be considered for persons traveling to a country or territory without an outbreak but with evidence of CHIKV transmission among humans within the last 5 years and those staying in endemic areas for a cumulative period of at least 6 months over a 2-year period. Specific recommendations for lab workers and persons older than 65 years were also made. This is good news for your older patients who may be participating in mission trips, volunteering, studying abroad, or just vacationing in an endemic area. Adolescent vaccine trials are ongoing and pediatric trials will soon be initiated. In addition, vector control and use of personal protective measures cannot be emphasized enough.

There are several other mosquito borne diseases, however our discussion here is limited to three. Why these three? WNV as a reminder that it is the most common neuroinvasive agent in the US. Dengue and CHIKV because they are not endemic in the US so they might not routinely be considered in febrile patients; both diseases have been reported and acquired on the mainland and your patients may travel to an endemic area and return home with an unwanted souvenir. You will be ready for them.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Chikungunya. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html.

Fagrem AC et al. West Nile and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases–United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Aug 25;72(34):901-906.

Fever in Returned Travelers, Travel Medicine (Fourth Edition). 2019. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-54696-6.00056-2.

Paz-Baily et al. Dengue Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2021 MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Dec 17;70(6):1-16).

Staples JE and Fischer M. Chikungunya virus in the Americas — what a vectorborne pathogen can do. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 4;371(10):887-9.

Mosquitoes and Diseases A-Z, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/diseases.html.

There are over 3700 types of mosquitoes worldwide and over 200 types in the continental United States, of which only 12 are associated with transmitting diseases to humans. The majority are just a nuisance. Since they cannot readily be distinguished, strategies to prevent any bites are recommended.

West Nile Virus

In the US, West Nile virus (WNV) is the leading cause of neuroinvasive arboviral disease. Just hearing the name took me back to New York in 1999 when sightings of dead birds around the city and boroughs were reported daily. The virus was isolated that same year. The enzootic circle occurs between mosquitoes and birds, which are the primary vertebrate host via the bite of Culex mosquitoes. After a bite from an infected mosquito, humans are usually a dead-end host since the level and duration of viremia needed to infect another mosquito is insufficient.

Human-to-human transmission is documented through blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation. Vertical transmission is rarely described. Initially isolated in New York, WNV quickly spread across North America and has been isolated in every continent except Antarctica. Most cases occur in the summer and autumn.

Most infected individuals are asymptomatic. Those who do develop symptoms have fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, and a transient rash. Less than 1% develop meningitis/encephalitis symptoms similar to other causes of aseptic meningitis. Those with encephalitis in addition to fever and headache may have altered mental status and focal neurologic deficits including flaccid paralysis or movement disorders.

Detection of anti-WNV IgM antibodies (AB) in serum or CSF is the most common way to make the diagnosis. IgM AB usually is present within 3-8 days after onset of symptoms and persists up to 90 days. Data from ArboNET, the national arboviral surveillance system managed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments, reveal that from 1999 to 2022 there were 56,575 cases of WNV including 28,684 cases of neuroinvasive disease. In 2023 there were 2,406 and 1,599 cases, respectively. Those historic totals for WNV are 10 times greater than the totals for all the other etiologies of neuroinvasive arboviral diseases in the US combined (Jamestown Canyon, LaCrosse, St. Louis, and Eastern Equine encephalitis n = 1813).

Remember to include WNV in your differential of a febrile patient with neurologic symptoms, mosquito bites, blood transfusions, and organ transplantation. Treatment is supportive care.

The US began screening all blood donations for WNV in 2003. Organ donor screening is not universal.

Dengue

Dengue, another arbovirus, is transmitted by bites of infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, which prefer to feed during the daytime. There are four dengue virus serotypes: DENV-1 DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. In endemic areas, all four serotypes are usually co-circulating and people can be infected by each one.

Long-term immunity is type specific. Heterologous protection lasts only a few months. Dengue is endemic throughout the tropics and subtropics of Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Approximately 53% of the world’s population live in an area where dengue transmission can occur. In the US, most cases are reported from Puerto Rico. Dengue is endemic in the following US territories: Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and free associated states. Most cases reported on the mainland are travel related. However, locally acquired dengue has been reported. From 2010 to 2023 Hawaii reported 250 cases, Florida 438, and Texas 40 locally acquired cases. During that same period, Puerto Rico reported more than 32,000 cases. It is the leading cause of febrile illness for travelers returning from the Caribbean, Latin America, and South Asia. Peru is currently experiencing an outbreak with more than 25,000 cases reported since January 2024. Most cases of dengue occur in adolescents and young adults. Severe disease occurs most often in infants, those with underlying chronic disease, pregnant women, and persons infected with dengue for the second time.

Symptoms range from a mild febrile illness to severe disease associated with hemorrhage and shock. Onset is usually 7-10 days after infection and symptoms include high fever, severe headache, retro-orbital pain, arthralgia and myalgias, nausea, and vomiting; some may develop a generalized rash.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies dengue as 1) dengue with or without warning signs for progression of disease and 2) severe dengue. Warning signs for disease progression include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, fluid accumulation (e.g., ascites, pericardial or pleural effusion), mucosal bleeding, restlessness, postural hypotension, liver enlargement greater than 2 cm. Severe dengue is defined as any sign of severe plasma leakage leading to shock, severe bleeding or organ failure, or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress. Management is supportive care.

Prevention: In the US, Dengvaxia, a live attenuated tetravalent vaccine, is approved for use in children aged 9–16 years with laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and living in areas where dengue is endemic. It is administered at 0, 6, and 12 months. It is not available for purchase on the mainland. Continued control of the vector and personal protection is necessary to prevent recurrent infections.

CHIKV

Chikungunya (CHIKV), which means “that which bends up” in the Mkonde language of Tanzania, refers to the appearance of the person with severe usually symmetric arthralgias characteristic for this infection that otherwise is often clinically confused with dengue and Zika. It too is transmitted by A. aegypti and A. albopictus and is prevalent in tropical Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Like dengue it is predominantly an urban disease. The WHO reported the first case in the Western Hemisphere in Saint Martin in December 2013. By August 2014, 31 additional territories and Caribbean or South American countries reported 576,535 suspected cases. Florida first reported locally acquired CHIKV in June 2014. By December an additional 11 cases had been identified. Texas reported one case in 2015. Diagnosis is with IgM ab or PCR. Treatment is supportive with most recovering from acute illness within 2 weeks. Data in adults indicate 40-52% may develop chronic or recurrent joint pain.

Prevention: IXCHIQ, a live attenuated vaccine, was licensed in November 2023 and recommended by the CDC in February 2024 for use in persons at least 18 years of age with travel to destinations where there is a CHIKV outbreak. It may be considered for persons traveling to a country or territory without an outbreak but with evidence of CHIKV transmission among humans within the last 5 years and those staying in endemic areas for a cumulative period of at least 6 months over a 2-year period. Specific recommendations for lab workers and persons older than 65 years were also made. This is good news for your older patients who may be participating in mission trips, volunteering, studying abroad, or just vacationing in an endemic area. Adolescent vaccine trials are ongoing and pediatric trials will soon be initiated. In addition, vector control and use of personal protective measures cannot be emphasized enough.

There are several other mosquito borne diseases, however our discussion here is limited to three. Why these three? WNV as a reminder that it is the most common neuroinvasive agent in the US. Dengue and CHIKV because they are not endemic in the US so they might not routinely be considered in febrile patients; both diseases have been reported and acquired on the mainland and your patients may travel to an endemic area and return home with an unwanted souvenir. You will be ready for them.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Chikungunya. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html.

Fagrem AC et al. West Nile and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases–United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Aug 25;72(34):901-906.

Fever in Returned Travelers, Travel Medicine (Fourth Edition). 2019. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-54696-6.00056-2.

Paz-Baily et al. Dengue Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2021 MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Dec 17;70(6):1-16).

Staples JE and Fischer M. Chikungunya virus in the Americas — what a vectorborne pathogen can do. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 4;371(10):887-9.

Mosquitoes and Diseases A-Z, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/diseases.html.

There are over 3700 types of mosquitoes worldwide and over 200 types in the continental United States, of which only 12 are associated with transmitting diseases to humans. The majority are just a nuisance. Since they cannot readily be distinguished, strategies to prevent any bites are recommended.

West Nile Virus

In the US, West Nile virus (WNV) is the leading cause of neuroinvasive arboviral disease. Just hearing the name took me back to New York in 1999 when sightings of dead birds around the city and boroughs were reported daily. The virus was isolated that same year. The enzootic circle occurs between mosquitoes and birds, which are the primary vertebrate host via the bite of Culex mosquitoes. After a bite from an infected mosquito, humans are usually a dead-end host since the level and duration of viremia needed to infect another mosquito is insufficient.

Human-to-human transmission is documented through blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation. Vertical transmission is rarely described. Initially isolated in New York, WNV quickly spread across North America and has been isolated in every continent except Antarctica. Most cases occur in the summer and autumn.

Most infected individuals are asymptomatic. Those who do develop symptoms have fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, and a transient rash. Less than 1% develop meningitis/encephalitis symptoms similar to other causes of aseptic meningitis. Those with encephalitis in addition to fever and headache may have altered mental status and focal neurologic deficits including flaccid paralysis or movement disorders.

Detection of anti-WNV IgM antibodies (AB) in serum or CSF is the most common way to make the diagnosis. IgM AB usually is present within 3-8 days after onset of symptoms and persists up to 90 days. Data from ArboNET, the national arboviral surveillance system managed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments, reveal that from 1999 to 2022 there were 56,575 cases of WNV including 28,684 cases of neuroinvasive disease. In 2023 there were 2,406 and 1,599 cases, respectively. Those historic totals for WNV are 10 times greater than the totals for all the other etiologies of neuroinvasive arboviral diseases in the US combined (Jamestown Canyon, LaCrosse, St. Louis, and Eastern Equine encephalitis n = 1813).

Remember to include WNV in your differential of a febrile patient with neurologic symptoms, mosquito bites, blood transfusions, and organ transplantation. Treatment is supportive care.

The US began screening all blood donations for WNV in 2003. Organ donor screening is not universal.

Dengue

Dengue, another arbovirus, is transmitted by bites of infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, which prefer to feed during the daytime. There are four dengue virus serotypes: DENV-1 DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. In endemic areas, all four serotypes are usually co-circulating and people can be infected by each one.

Long-term immunity is type specific. Heterologous protection lasts only a few months. Dengue is endemic throughout the tropics and subtropics of Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Approximately 53% of the world’s population live in an area where dengue transmission can occur. In the US, most cases are reported from Puerto Rico. Dengue is endemic in the following US territories: Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and free associated states. Most cases reported on the mainland are travel related. However, locally acquired dengue has been reported. From 2010 to 2023 Hawaii reported 250 cases, Florida 438, and Texas 40 locally acquired cases. During that same period, Puerto Rico reported more than 32,000 cases. It is the leading cause of febrile illness for travelers returning from the Caribbean, Latin America, and South Asia. Peru is currently experiencing an outbreak with more than 25,000 cases reported since January 2024. Most cases of dengue occur in adolescents and young adults. Severe disease occurs most often in infants, those with underlying chronic disease, pregnant women, and persons infected with dengue for the second time.

Symptoms range from a mild febrile illness to severe disease associated with hemorrhage and shock. Onset is usually 7-10 days after infection and symptoms include high fever, severe headache, retro-orbital pain, arthralgia and myalgias, nausea, and vomiting; some may develop a generalized rash.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies dengue as 1) dengue with or without warning signs for progression of disease and 2) severe dengue. Warning signs for disease progression include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, fluid accumulation (e.g., ascites, pericardial or pleural effusion), mucosal bleeding, restlessness, postural hypotension, liver enlargement greater than 2 cm. Severe dengue is defined as any sign of severe plasma leakage leading to shock, severe bleeding or organ failure, or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress. Management is supportive care.

Prevention: In the US, Dengvaxia, a live attenuated tetravalent vaccine, is approved for use in children aged 9–16 years with laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and living in areas where dengue is endemic. It is administered at 0, 6, and 12 months. It is not available for purchase on the mainland. Continued control of the vector and personal protection is necessary to prevent recurrent infections.

CHIKV

Chikungunya (CHIKV), which means “that which bends up” in the Mkonde language of Tanzania, refers to the appearance of the person with severe usually symmetric arthralgias characteristic for this infection that otherwise is often clinically confused with dengue and Zika. It too is transmitted by A. aegypti and A. albopictus and is prevalent in tropical Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Like dengue it is predominantly an urban disease. The WHO reported the first case in the Western Hemisphere in Saint Martin in December 2013. By August 2014, 31 additional territories and Caribbean or South American countries reported 576,535 suspected cases. Florida first reported locally acquired CHIKV in June 2014. By December an additional 11 cases had been identified. Texas reported one case in 2015. Diagnosis is with IgM ab or PCR. Treatment is supportive with most recovering from acute illness within 2 weeks. Data in adults indicate 40-52% may develop chronic or recurrent joint pain.

Prevention: IXCHIQ, a live attenuated vaccine, was licensed in November 2023 and recommended by the CDC in February 2024 for use in persons at least 18 years of age with travel to destinations where there is a CHIKV outbreak. It may be considered for persons traveling to a country or territory without an outbreak but with evidence of CHIKV transmission among humans within the last 5 years and those staying in endemic areas for a cumulative period of at least 6 months over a 2-year period. Specific recommendations for lab workers and persons older than 65 years were also made. This is good news for your older patients who may be participating in mission trips, volunteering, studying abroad, or just vacationing in an endemic area. Adolescent vaccine trials are ongoing and pediatric trials will soon be initiated. In addition, vector control and use of personal protective measures cannot be emphasized enough.

There are several other mosquito borne diseases, however our discussion here is limited to three. Why these three? WNV as a reminder that it is the most common neuroinvasive agent in the US. Dengue and CHIKV because they are not endemic in the US so they might not routinely be considered in febrile patients; both diseases have been reported and acquired on the mainland and your patients may travel to an endemic area and return home with an unwanted souvenir. You will be ready for them.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Chikungunya. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html.

Fagrem AC et al. West Nile and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases–United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Aug 25;72(34):901-906.

Fever in Returned Travelers, Travel Medicine (Fourth Edition). 2019. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-54696-6.00056-2.

Paz-Baily et al. Dengue Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2021 MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Dec 17;70(6):1-16).

Staples JE and Fischer M. Chikungunya virus in the Americas — what a vectorborne pathogen can do. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 4;371(10):887-9.

Mosquitoes and Diseases A-Z, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/diseases.html.

Using the Road Map

I had a premed college student with me, a young lady trying to figure out if medicine was for her, and what exactly a neurologist does.

The patient, a gentlemen in his mid-70s, had just left. He had some unusual symptoms. Not implausible, but the kind of case where the answers don’t come together easily. I’d ordered tests for the usual suspects and walked him up front.

When I got back she asked me “what do you think is wrong with him?”

Without thinking I said “I have no idea.” By this time I’d turned to some scheduling messages from my secretary, and didn’t register the student’s surprise for a moment.

I mean, I’m an attending physician. To her I’m the epitome of the career. I got accepted to (and survived) medical school. I made it through residency and fellowship and have almost 26 years of trench-earned experience behind me (hard to believe for me, too, sometimes). And yet I’d just said I didn’t know what was going on.

Reversing the roles and thinking back to the late 1980s, I probably would have felt the same way she did.

Of course “I have no idea” is a bit of unintentional hyperbole. I have some idea, just not a clear answer yet. I’d turned over the possible locations and causes, and so ordered tests to help narrow it down. As one of my attendings in residency used to say, “some days you need a rifle, some days a shotgun” to figure it out.

Being a doctor, even a good one (I hope I am, but not making any guarantees) doesn’t mean you know everything, or have the ability to figure it out immediately. Otherwise we wouldn’t need imaging, labs, and a host of other tests. Sherlock Holmes was a lot of things, but Watson was the doctor.

To those at the beginning of their careers, just like it was to us then, this is a revelation. Aren’t we supposed to know everything? We probably once believed we would, too, someday.

What combination of tests and decisions will hopefully lead us to the correct point.

Most of us realize that intuitively at this point, but it can be hard to explain to others. We have patients ask “what do you think is going on?” and we often have no answer other than “not sure yet, but I’ll try to find out.”

We don’t realize how far we’ve come until we see ourselves in someone who’s starting the same journey. And that’s something you can’t teach.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I had a premed college student with me, a young lady trying to figure out if medicine was for her, and what exactly a neurologist does.

The patient, a gentlemen in his mid-70s, had just left. He had some unusual symptoms. Not implausible, but the kind of case where the answers don’t come together easily. I’d ordered tests for the usual suspects and walked him up front.

When I got back she asked me “what do you think is wrong with him?”

Without thinking I said “I have no idea.” By this time I’d turned to some scheduling messages from my secretary, and didn’t register the student’s surprise for a moment.

I mean, I’m an attending physician. To her I’m the epitome of the career. I got accepted to (and survived) medical school. I made it through residency and fellowship and have almost 26 years of trench-earned experience behind me (hard to believe for me, too, sometimes). And yet I’d just said I didn’t know what was going on.

Reversing the roles and thinking back to the late 1980s, I probably would have felt the same way she did.

Of course “I have no idea” is a bit of unintentional hyperbole. I have some idea, just not a clear answer yet. I’d turned over the possible locations and causes, and so ordered tests to help narrow it down. As one of my attendings in residency used to say, “some days you need a rifle, some days a shotgun” to figure it out.

Being a doctor, even a good one (I hope I am, but not making any guarantees) doesn’t mean you know everything, or have the ability to figure it out immediately. Otherwise we wouldn’t need imaging, labs, and a host of other tests. Sherlock Holmes was a lot of things, but Watson was the doctor.

To those at the beginning of their careers, just like it was to us then, this is a revelation. Aren’t we supposed to know everything? We probably once believed we would, too, someday.

What combination of tests and decisions will hopefully lead us to the correct point.

Most of us realize that intuitively at this point, but it can be hard to explain to others. We have patients ask “what do you think is going on?” and we often have no answer other than “not sure yet, but I’ll try to find out.”

We don’t realize how far we’ve come until we see ourselves in someone who’s starting the same journey. And that’s something you can’t teach.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I had a premed college student with me, a young lady trying to figure out if medicine was for her, and what exactly a neurologist does.

The patient, a gentlemen in his mid-70s, had just left. He had some unusual symptoms. Not implausible, but the kind of case where the answers don’t come together easily. I’d ordered tests for the usual suspects and walked him up front.

When I got back she asked me “what do you think is wrong with him?”

Without thinking I said “I have no idea.” By this time I’d turned to some scheduling messages from my secretary, and didn’t register the student’s surprise for a moment.

I mean, I’m an attending physician. To her I’m the epitome of the career. I got accepted to (and survived) medical school. I made it through residency and fellowship and have almost 26 years of trench-earned experience behind me (hard to believe for me, too, sometimes). And yet I’d just said I didn’t know what was going on.

Reversing the roles and thinking back to the late 1980s, I probably would have felt the same way she did.

Of course “I have no idea” is a bit of unintentional hyperbole. I have some idea, just not a clear answer yet. I’d turned over the possible locations and causes, and so ordered tests to help narrow it down. As one of my attendings in residency used to say, “some days you need a rifle, some days a shotgun” to figure it out.

Being a doctor, even a good one (I hope I am, but not making any guarantees) doesn’t mean you know everything, or have the ability to figure it out immediately. Otherwise we wouldn’t need imaging, labs, and a host of other tests. Sherlock Holmes was a lot of things, but Watson was the doctor.

To those at the beginning of their careers, just like it was to us then, this is a revelation. Aren’t we supposed to know everything? We probably once believed we would, too, someday.

What combination of tests and decisions will hopefully lead us to the correct point.

Most of us realize that intuitively at this point, but it can be hard to explain to others. We have patients ask “what do you think is going on?” and we often have no answer other than “not sure yet, but I’ll try to find out.”

We don’t realize how far we’ve come until we see ourselves in someone who’s starting the same journey. And that’s something you can’t teach.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

ERISA Health Plan Lawsuits: Why Should We Care?

A recently filed lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson can serve as an example to use when advocating for patients who have insurance through their employers that can potentially hurt them physically and financially. When your patient has an employer-funded health insurance plan where the employer directly pays for all medical costs — called an ERISA plan for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act — there are certain accountability, fairness, and fiduciary responsibilities that the employers must meet. These so-called ERISA plans do not have to follow state utilization management legislation that addresses harmful changes in insurers’ formularies and other policies, so when the plans are not properly overseen and do not mandate the delivery of proper care at the lowest cost, both the patient and employer may be losing out.

The J&J lawsuit serves as a bellwether warning to self-insured employers to demand transparency from their third-party administrators so as not to (knowingly or unknowingly) breach their fiduciary duty to their health plans and employees. These duties include ensuring reasonable plan costs as well as acting in the best interest of their employees. There were multiple complaints in the lawsuit by a J&J employee, stating that she paid a much higher price for her multiple sclerosis drug through the plan than the price she eventually found at a lower cost pharmacy. The allegations state that J&J failed to show prudence in its selection of a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). In addition, the company failed to negotiate better drug pricing terms, and the design of the drug plan steered patients to the PBM specialty pharmacy, resulting in higher prices for the employees. All of these led to higher drug costs and premiums for employees, which, according to the lawsuit, is a breach of J&J’s fiduciary duties.

Why Should Rheumatologists Care About This?

With all insurance plans, it feels as though we are dealing with obstacles every day that keep us from giving the excellent rheumatologic care that our patients deserve. Self-insured employers now account for over 50% of commercial health plans, and as rheumatologists caring for the employees of these companies, we can use those transparency, accountability, and fiduciary responsibilities of the employer to ensure that our patients are getting the proper care at the lowest cost.

Not only is the J&J lawsuit a warning to self-insured employers, but a reminder to rheumatologists to be on the lookout for drug pricing issues and formulary construction that leads to higher pricing for employees and the plan. For example, make note if your patient is forced to fail a much higher priced self-injectable biologic before using a much lower cost infusible medication. Or if the plan mandates the use of the much higher priced adalimumab biosimilars over the lower priced biosimilars or even the highest priced JAK inhibitor over the lowest priced one. Let’s not forget mandated white bagging, which is often much more expensive to the plan than the buy-and-bill model through a rheumatologist’s office.

Recently, we have been able to help rheumatology practices get exemptions from white-bagging mandates that large self-insured employers often have in their plan documents. We have been able to show that the cost of obtaining the medication through specialty pharmacy (SP) is much higher than through the buy-and-bill model. Mandating that the plan spend more money on SP drugs, as opposed to allowing the rheumatologist to buy and bill, could easily be interpreted as a breach of fiduciary duty on the part of the employer by mandating a higher cost model.

CSRO Payer Issue Response Team

I have written about the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO)’s Payer Issue Response Team (PIRT) in the past. Rheumatologists around the country can send to PIRT any problems that they are having with payers. A recent PIRT submission involved a white-bagging mandate for an employee of a very large international Fortune 500 company. This particular example is important because of the response by the VP of Global Benefits for this company. Express Scripts is the administrator of pharmacy benefits for this company. The rheumatologist was told that he could not buy and bill for an infusible medicine but would have to obtain the drug through Express Scripts’ SP. He then asked Express Scripts for the SP medication’s cost to the health plan in order to compare the SP price versus what the buy-and-bill model would cost this company. Express Scripts would not respond to this simple transparency question; often, PBMs claim that this is proprietary information.

I was able to speak with the company’s VP of Global Benefits regarding this issue. First of all, he stated that his company was not mandating white bagging. I explained to him that the plan documents had white bagging as the only option for acquisition of provider-administered drugs. A rheumatologist would have to apply for an exemption to buy and bill, and in this case, it was denied. This is essentially a mandate.

I gave the VP of Global Benefits an example of another large Fortune 500 company (UPS) that spent over $30,000 per year more on an infusible medication when obtained through SP than what it cost them under a buy-and-bill model. I had hoped that this example would impress upon the VP the importance of transparency in pricing and claims to prevent his company from unknowingly costing the health plan more and its being construed as a breach of fiduciary duty. It was explained to me by the VP of Global Benefits that his company is part of the National Drug Purchasers Coalition and they trust Express Scripts to do the right thing for them. As they say, “You can lead a horse to water, but can’t make it drink.”

Liability of a Plan That Physically Harms an Employee?

A slightly different example of a self-insured employer, presumably unknowingly, allowing its third-party administrator to mishandle the care of an employee was recently brought to me by a rheumatologist in North Carolina. She takes care of an employee who has rheumatoid arthritis with severe interstitial lung disease (ILD). The employee’s pulmonary status was stabilized on several courses of Rituxan (reference product of rituximab). Recently, BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina, the third-party administrator of this employer’s plan, mandated a switch to a biosimilar of rituximab for the treatment of the ILD. The rheumatologist appealed the nonmedical switch but gave the patient the biosimilar so as not to delay care. Her patient’s condition is now deteriorating with progression of the ILD, and she once again has asked for an exemption to use Rituxan, which had initially stabilized the patient. Her staff told her that the BCBSNC rep said that the patient would have to have a life-threatening infusion reaction (and present the bill for the ambulance) before they would approve a return to the reference product. An employer that knowingly or unknowingly allows a third-party administrator to act in such a way as to endanger the life of an employee could be considered to be breaching its fiduciary duty. (Disclaimer: I am not an attorney — merely a rheumatologist with common sense. Nor am I making any qualitative statement about biosimilars.)

We now have a lawsuit to which you can refer when advocating for our patients who are employed by large, self-insured employers. It is unfortunate that it is not the third-party administrators or PBMs that can be sued, as they are generally not the fiduciaries for the plan. It is the unsuspecting employers who “trust” their brokers/consultants and the third-party administrators to do the right thing. Please continue to send us your payer issues. And if your patient works for a self-insured employer, I will continue to remind the CEO, CFO, and chief compliance officer that an employer with an ERISA health plan can potentially face legal action if the health plan’s actions or decisions cause harm to an employee’s health — physically or in the wallet.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

A recently filed lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson can serve as an example to use when advocating for patients who have insurance through their employers that can potentially hurt them physically and financially. When your patient has an employer-funded health insurance plan where the employer directly pays for all medical costs — called an ERISA plan for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act — there are certain accountability, fairness, and fiduciary responsibilities that the employers must meet. These so-called ERISA plans do not have to follow state utilization management legislation that addresses harmful changes in insurers’ formularies and other policies, so when the plans are not properly overseen and do not mandate the delivery of proper care at the lowest cost, both the patient and employer may be losing out.

The J&J lawsuit serves as a bellwether warning to self-insured employers to demand transparency from their third-party administrators so as not to (knowingly or unknowingly) breach their fiduciary duty to their health plans and employees. These duties include ensuring reasonable plan costs as well as acting in the best interest of their employees. There were multiple complaints in the lawsuit by a J&J employee, stating that she paid a much higher price for her multiple sclerosis drug through the plan than the price she eventually found at a lower cost pharmacy. The allegations state that J&J failed to show prudence in its selection of a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). In addition, the company failed to negotiate better drug pricing terms, and the design of the drug plan steered patients to the PBM specialty pharmacy, resulting in higher prices for the employees. All of these led to higher drug costs and premiums for employees, which, according to the lawsuit, is a breach of J&J’s fiduciary duties.

Why Should Rheumatologists Care About This?

With all insurance plans, it feels as though we are dealing with obstacles every day that keep us from giving the excellent rheumatologic care that our patients deserve. Self-insured employers now account for over 50% of commercial health plans, and as rheumatologists caring for the employees of these companies, we can use those transparency, accountability, and fiduciary responsibilities of the employer to ensure that our patients are getting the proper care at the lowest cost.

Not only is the J&J lawsuit a warning to self-insured employers, but a reminder to rheumatologists to be on the lookout for drug pricing issues and formulary construction that leads to higher pricing for employees and the plan. For example, make note if your patient is forced to fail a much higher priced self-injectable biologic before using a much lower cost infusible medication. Or if the plan mandates the use of the much higher priced adalimumab biosimilars over the lower priced biosimilars or even the highest priced JAK inhibitor over the lowest priced one. Let’s not forget mandated white bagging, which is often much more expensive to the plan than the buy-and-bill model through a rheumatologist’s office.

Recently, we have been able to help rheumatology practices get exemptions from white-bagging mandates that large self-insured employers often have in their plan documents. We have been able to show that the cost of obtaining the medication through specialty pharmacy (SP) is much higher than through the buy-and-bill model. Mandating that the plan spend more money on SP drugs, as opposed to allowing the rheumatologist to buy and bill, could easily be interpreted as a breach of fiduciary duty on the part of the employer by mandating a higher cost model.

CSRO Payer Issue Response Team

I have written about the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO)’s Payer Issue Response Team (PIRT) in the past. Rheumatologists around the country can send to PIRT any problems that they are having with payers. A recent PIRT submission involved a white-bagging mandate for an employee of a very large international Fortune 500 company. This particular example is important because of the response by the VP of Global Benefits for this company. Express Scripts is the administrator of pharmacy benefits for this company. The rheumatologist was told that he could not buy and bill for an infusible medicine but would have to obtain the drug through Express Scripts’ SP. He then asked Express Scripts for the SP medication’s cost to the health plan in order to compare the SP price versus what the buy-and-bill model would cost this company. Express Scripts would not respond to this simple transparency question; often, PBMs claim that this is proprietary information.

I was able to speak with the company’s VP of Global Benefits regarding this issue. First of all, he stated that his company was not mandating white bagging. I explained to him that the plan documents had white bagging as the only option for acquisition of provider-administered drugs. A rheumatologist would have to apply for an exemption to buy and bill, and in this case, it was denied. This is essentially a mandate.

I gave the VP of Global Benefits an example of another large Fortune 500 company (UPS) that spent over $30,000 per year more on an infusible medication when obtained through SP than what it cost them under a buy-and-bill model. I had hoped that this example would impress upon the VP the importance of transparency in pricing and claims to prevent his company from unknowingly costing the health plan more and its being construed as a breach of fiduciary duty. It was explained to me by the VP of Global Benefits that his company is part of the National Drug Purchasers Coalition and they trust Express Scripts to do the right thing for them. As they say, “You can lead a horse to water, but can’t make it drink.”

Liability of a Plan That Physically Harms an Employee?

A slightly different example of a self-insured employer, presumably unknowingly, allowing its third-party administrator to mishandle the care of an employee was recently brought to me by a rheumatologist in North Carolina. She takes care of an employee who has rheumatoid arthritis with severe interstitial lung disease (ILD). The employee’s pulmonary status was stabilized on several courses of Rituxan (reference product of rituximab). Recently, BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina, the third-party administrator of this employer’s plan, mandated a switch to a biosimilar of rituximab for the treatment of the ILD. The rheumatologist appealed the nonmedical switch but gave the patient the biosimilar so as not to delay care. Her patient’s condition is now deteriorating with progression of the ILD, and she once again has asked for an exemption to use Rituxan, which had initially stabilized the patient. Her staff told her that the BCBSNC rep said that the patient would have to have a life-threatening infusion reaction (and present the bill for the ambulance) before they would approve a return to the reference product. An employer that knowingly or unknowingly allows a third-party administrator to act in such a way as to endanger the life of an employee could be considered to be breaching its fiduciary duty. (Disclaimer: I am not an attorney — merely a rheumatologist with common sense. Nor am I making any qualitative statement about biosimilars.)

We now have a lawsuit to which you can refer when advocating for our patients who are employed by large, self-insured employers. It is unfortunate that it is not the third-party administrators or PBMs that can be sued, as they are generally not the fiduciaries for the plan. It is the unsuspecting employers who “trust” their brokers/consultants and the third-party administrators to do the right thing. Please continue to send us your payer issues. And if your patient works for a self-insured employer, I will continue to remind the CEO, CFO, and chief compliance officer that an employer with an ERISA health plan can potentially face legal action if the health plan’s actions or decisions cause harm to an employee’s health — physically or in the wallet.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

A recently filed lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson can serve as an example to use when advocating for patients who have insurance through their employers that can potentially hurt them physically and financially. When your patient has an employer-funded health insurance plan where the employer directly pays for all medical costs — called an ERISA plan for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act — there are certain accountability, fairness, and fiduciary responsibilities that the employers must meet. These so-called ERISA plans do not have to follow state utilization management legislation that addresses harmful changes in insurers’ formularies and other policies, so when the plans are not properly overseen and do not mandate the delivery of proper care at the lowest cost, both the patient and employer may be losing out.

The J&J lawsuit serves as a bellwether warning to self-insured employers to demand transparency from their third-party administrators so as not to (knowingly or unknowingly) breach their fiduciary duty to their health plans and employees. These duties include ensuring reasonable plan costs as well as acting in the best interest of their employees. There were multiple complaints in the lawsuit by a J&J employee, stating that she paid a much higher price for her multiple sclerosis drug through the plan than the price she eventually found at a lower cost pharmacy. The allegations state that J&J failed to show prudence in its selection of a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). In addition, the company failed to negotiate better drug pricing terms, and the design of the drug plan steered patients to the PBM specialty pharmacy, resulting in higher prices for the employees. All of these led to higher drug costs and premiums for employees, which, according to the lawsuit, is a breach of J&J’s fiduciary duties.

Why Should Rheumatologists Care About This?

With all insurance plans, it feels as though we are dealing with obstacles every day that keep us from giving the excellent rheumatologic care that our patients deserve. Self-insured employers now account for over 50% of commercial health plans, and as rheumatologists caring for the employees of these companies, we can use those transparency, accountability, and fiduciary responsibilities of the employer to ensure that our patients are getting the proper care at the lowest cost.

Not only is the J&J lawsuit a warning to self-insured employers, but a reminder to rheumatologists to be on the lookout for drug pricing issues and formulary construction that leads to higher pricing for employees and the plan. For example, make note if your patient is forced to fail a much higher priced self-injectable biologic before using a much lower cost infusible medication. Or if the plan mandates the use of the much higher priced adalimumab biosimilars over the lower priced biosimilars or even the highest priced JAK inhibitor over the lowest priced one. Let’s not forget mandated white bagging, which is often much more expensive to the plan than the buy-and-bill model through a rheumatologist’s office.

Recently, we have been able to help rheumatology practices get exemptions from white-bagging mandates that large self-insured employers often have in their plan documents. We have been able to show that the cost of obtaining the medication through specialty pharmacy (SP) is much higher than through the buy-and-bill model. Mandating that the plan spend more money on SP drugs, as opposed to allowing the rheumatologist to buy and bill, could easily be interpreted as a breach of fiduciary duty on the part of the employer by mandating a higher cost model.

CSRO Payer Issue Response Team

I have written about the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO)’s Payer Issue Response Team (PIRT) in the past. Rheumatologists around the country can send to PIRT any problems that they are having with payers. A recent PIRT submission involved a white-bagging mandate for an employee of a very large international Fortune 500 company. This particular example is important because of the response by the VP of Global Benefits for this company. Express Scripts is the administrator of pharmacy benefits for this company. The rheumatologist was told that he could not buy and bill for an infusible medicine but would have to obtain the drug through Express Scripts’ SP. He then asked Express Scripts for the SP medication’s cost to the health plan in order to compare the SP price versus what the buy-and-bill model would cost this company. Express Scripts would not respond to this simple transparency question; often, PBMs claim that this is proprietary information.

I was able to speak with the company’s VP of Global Benefits regarding this issue. First of all, he stated that his company was not mandating white bagging. I explained to him that the plan documents had white bagging as the only option for acquisition of provider-administered drugs. A rheumatologist would have to apply for an exemption to buy and bill, and in this case, it was denied. This is essentially a mandate.

I gave the VP of Global Benefits an example of another large Fortune 500 company (UPS) that spent over $30,000 per year more on an infusible medication when obtained through SP than what it cost them under a buy-and-bill model. I had hoped that this example would impress upon the VP the importance of transparency in pricing and claims to prevent his company from unknowingly costing the health plan more and its being construed as a breach of fiduciary duty. It was explained to me by the VP of Global Benefits that his company is part of the National Drug Purchasers Coalition and they trust Express Scripts to do the right thing for them. As they say, “You can lead a horse to water, but can’t make it drink.”

Liability of a Plan That Physically Harms an Employee?

A slightly different example of a self-insured employer, presumably unknowingly, allowing its third-party administrator to mishandle the care of an employee was recently brought to me by a rheumatologist in North Carolina. She takes care of an employee who has rheumatoid arthritis with severe interstitial lung disease (ILD). The employee’s pulmonary status was stabilized on several courses of Rituxan (reference product of rituximab). Recently, BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina, the third-party administrator of this employer’s plan, mandated a switch to a biosimilar of rituximab for the treatment of the ILD. The rheumatologist appealed the nonmedical switch but gave the patient the biosimilar so as not to delay care. Her patient’s condition is now deteriorating with progression of the ILD, and she once again has asked for an exemption to use Rituxan, which had initially stabilized the patient. Her staff told her that the BCBSNC rep said that the patient would have to have a life-threatening infusion reaction (and present the bill for the ambulance) before they would approve a return to the reference product. An employer that knowingly or unknowingly allows a third-party administrator to act in such a way as to endanger the life of an employee could be considered to be breaching its fiduciary duty. (Disclaimer: I am not an attorney — merely a rheumatologist with common sense. Nor am I making any qualitative statement about biosimilars.)

We now have a lawsuit to which you can refer when advocating for our patients who are employed by large, self-insured employers. It is unfortunate that it is not the third-party administrators or PBMs that can be sued, as they are generally not the fiduciaries for the plan. It is the unsuspecting employers who “trust” their brokers/consultants and the third-party administrators to do the right thing. Please continue to send us your payer issues. And if your patient works for a self-insured employer, I will continue to remind the CEO, CFO, and chief compliance officer that an employer with an ERISA health plan can potentially face legal action if the health plan’s actions or decisions cause harm to an employee’s health — physically or in the wallet.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

Vitamin D Supplements May Be a Double-Edged Sword

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

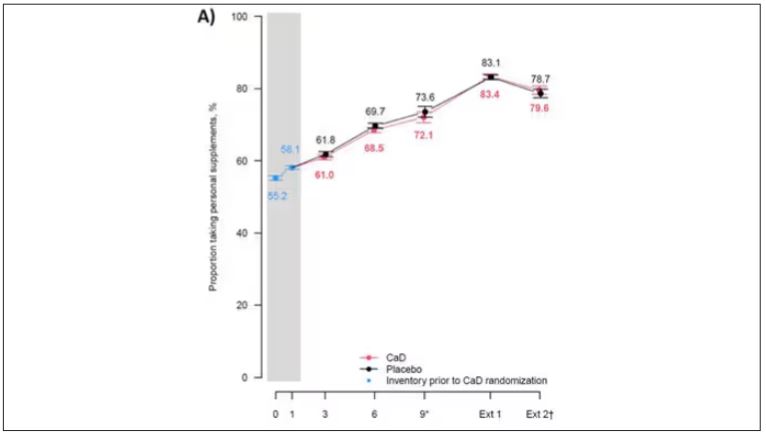

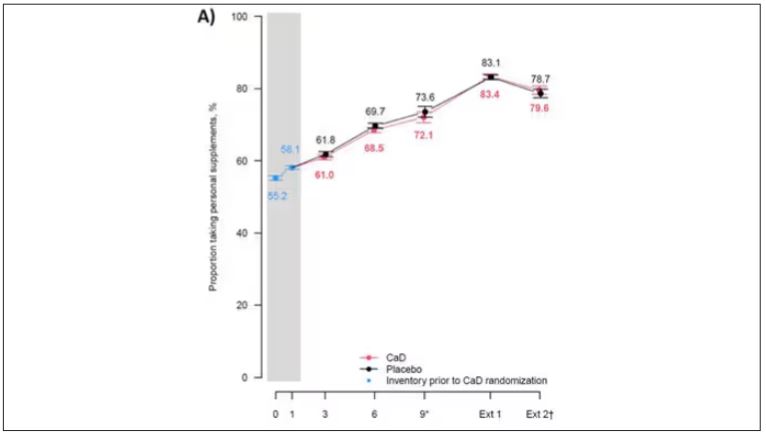

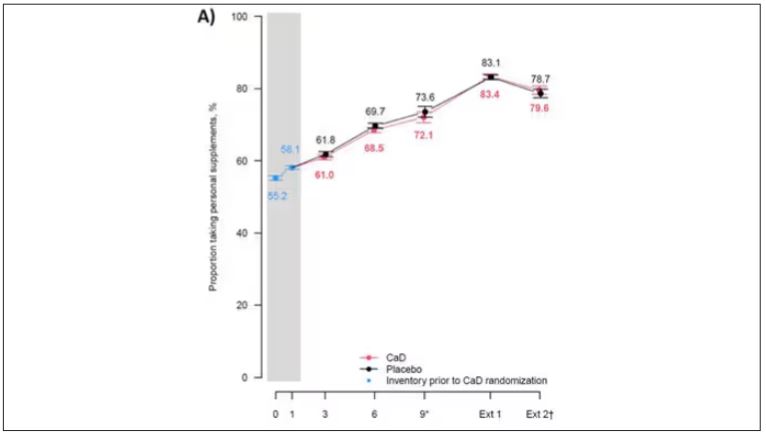

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

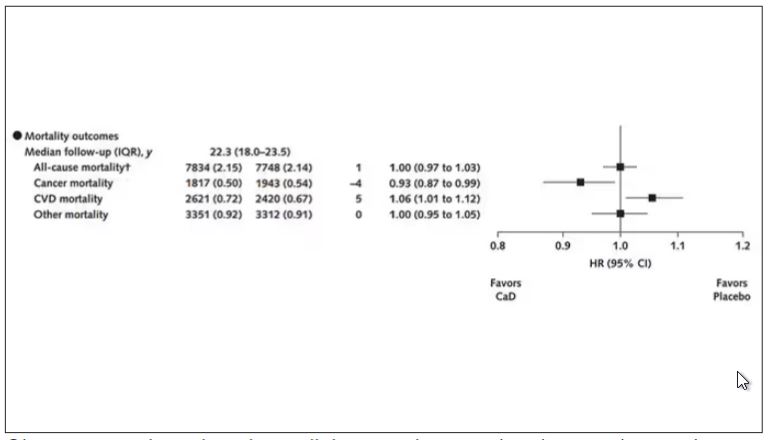

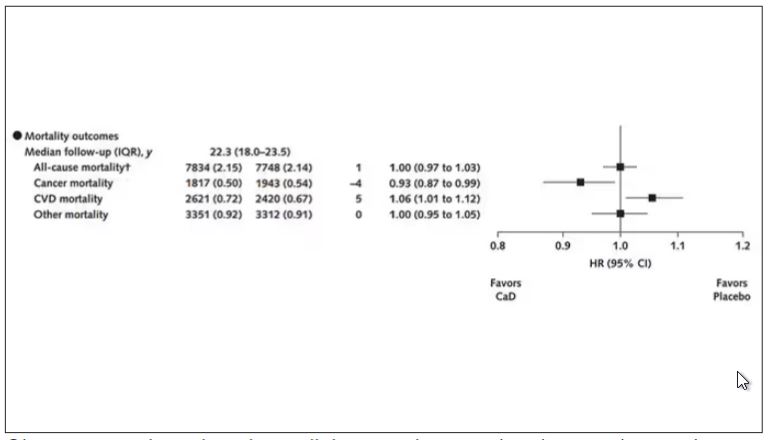

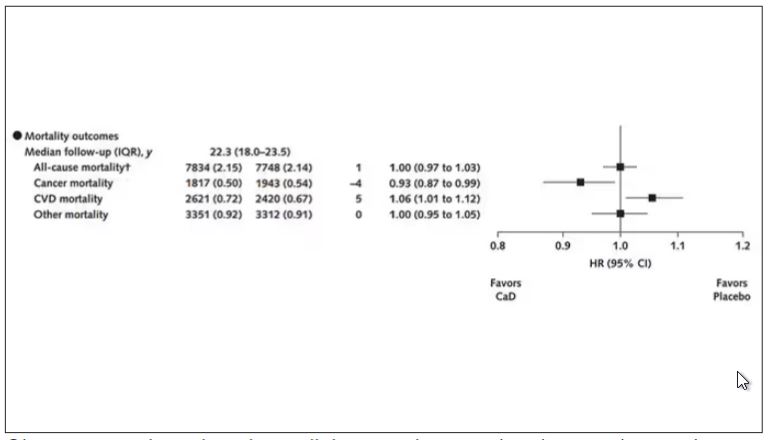

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.

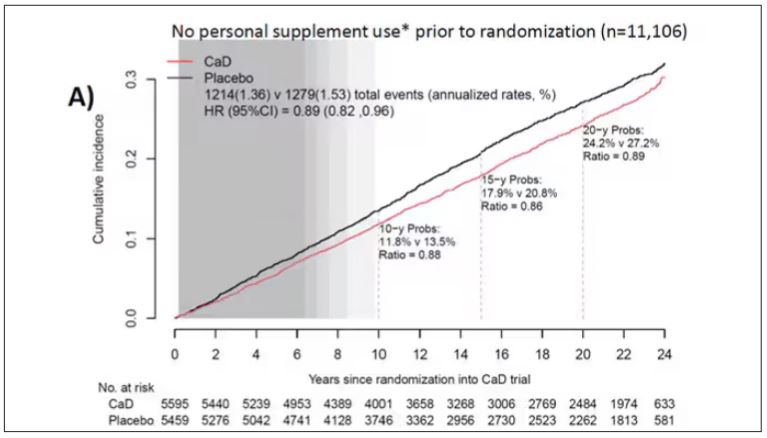

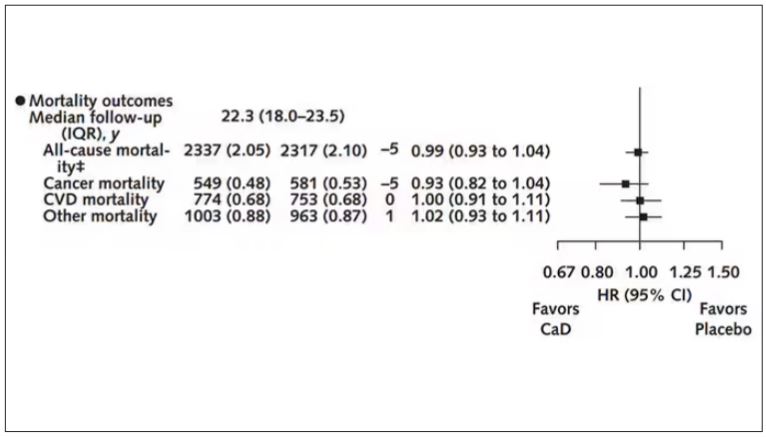

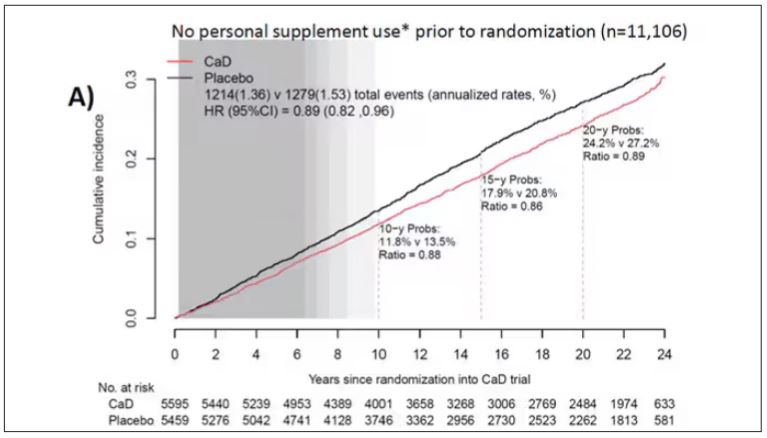

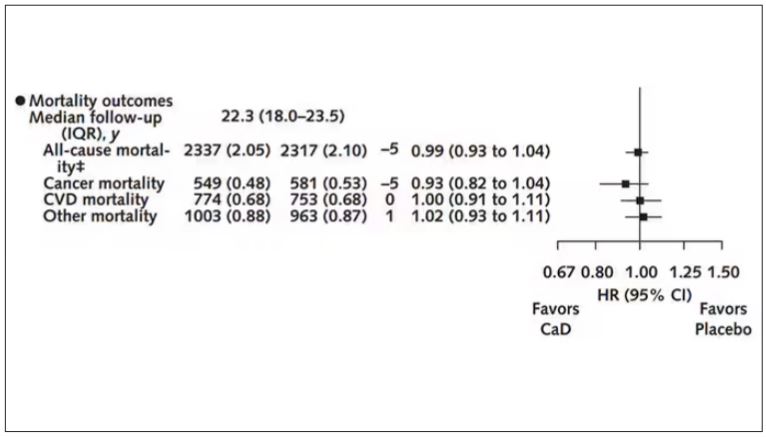

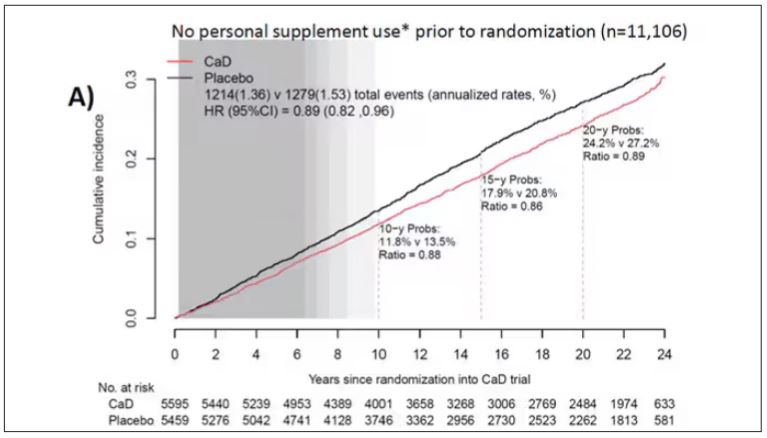

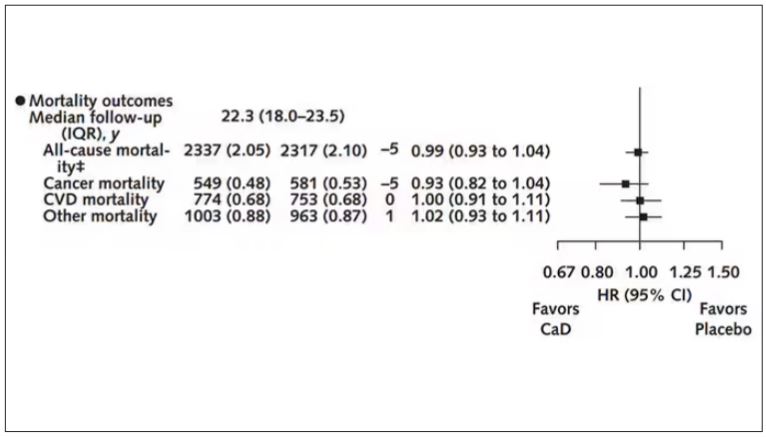

To get a better view of the real effects of randomization, the authors restricted the analysis to just those who did not use outside supplements. If vitamin D supplements help, then these are the people they should help. This group had about a 11% reduction in the incidence of cancer — statistically significant — and a 7% reduction in cancer mortality that did not meet the bar for statistical significance.

There was no increase in cardiovascular disease among this group. But this small effect on cancer was nowhere near enough to significantly reduce the rate of all-cause mortality.

Among those using supplements, vitamin D supplementation didn’t really move the needle on any outcome.

I know what you’re thinking: How many of these women were vitamin D deficient when we got started? These results may simply be telling us that people who have normal vitamin D levels are fine to go without supplementation.

Nearly three fourths of women who were not taking supplements entered the trial with vitamin D levels below the 50 nmol/L cutoff that the authors suggest would qualify for deficiency. Around half of those who used supplements were deficient. And yet, frustratingly, I could not find data on the effect of randomization to supplementation stratified by baseline vitamin D level. I even reached out to Dr Thomson to ask about this. She replied, “We did not stratify on baseline values because the numbers are too small statistically to test this.” Sorry.

In the meantime, I can tell you that for your “average woman,” vitamin D supplementation likely has no effect on mortality. It might modestly reduce the risk for certain cancers while increasing the risk for heart disease (probably through coronary calcification). So, there might be some room for personalization here. Perhaps women with a strong family history of cancer or other risk factors would do better with supplements, and those with a high risk for heart disease would do worse. Seems like a strategy that could be tested in a clinical trial. But maybe we could ask the participants to give up their extracurricular supplement use before they enter the trial. F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.

To get a better view of the real effects of randomization, the authors restricted the analysis to just those who did not use outside supplements. If vitamin D supplements help, then these are the people they should help. This group had about a 11% reduction in the incidence of cancer — statistically significant — and a 7% reduction in cancer mortality that did not meet the bar for statistical significance.

There was no increase in cardiovascular disease among this group. But this small effect on cancer was nowhere near enough to significantly reduce the rate of all-cause mortality.

Among those using supplements, vitamin D supplementation didn’t really move the needle on any outcome.

I know what you’re thinking: How many of these women were vitamin D deficient when we got started? These results may simply be telling us that people who have normal vitamin D levels are fine to go without supplementation.

Nearly three fourths of women who were not taking supplements entered the trial with vitamin D levels below the 50 nmol/L cutoff that the authors suggest would qualify for deficiency. Around half of those who used supplements were deficient. And yet, frustratingly, I could not find data on the effect of randomization to supplementation stratified by baseline vitamin D level. I even reached out to Dr Thomson to ask about this. She replied, “We did not stratify on baseline values because the numbers are too small statistically to test this.” Sorry.

In the meantime, I can tell you that for your “average woman,” vitamin D supplementation likely has no effect on mortality. It might modestly reduce the risk for certain cancers while increasing the risk for heart disease (probably through coronary calcification). So, there might be some room for personalization here. Perhaps women with a strong family history of cancer or other risk factors would do better with supplements, and those with a high risk for heart disease would do worse. Seems like a strategy that could be tested in a clinical trial. But maybe we could ask the participants to give up their extracurricular supplement use before they enter the trial. F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.