User login

A new and completely different pain medicine

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

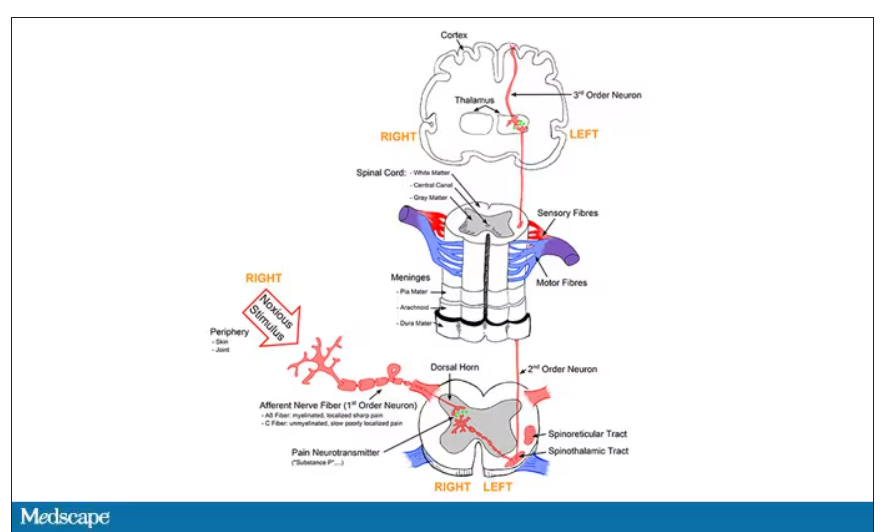

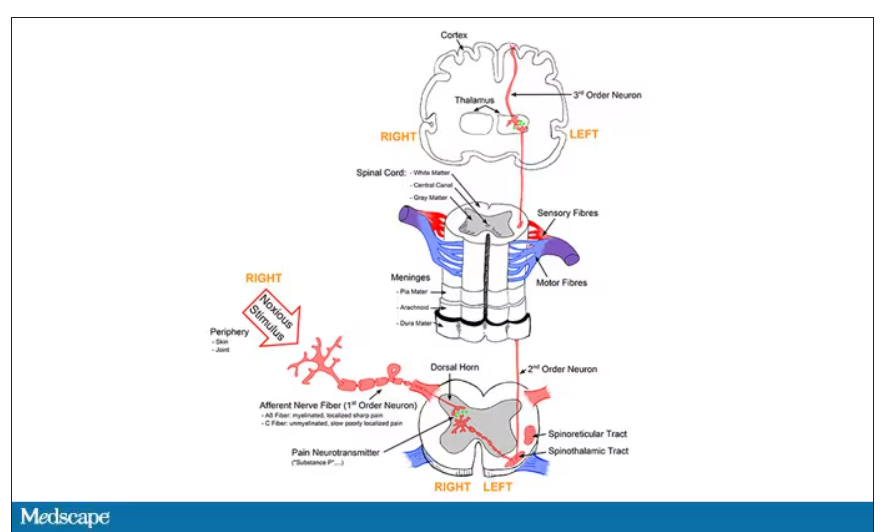

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

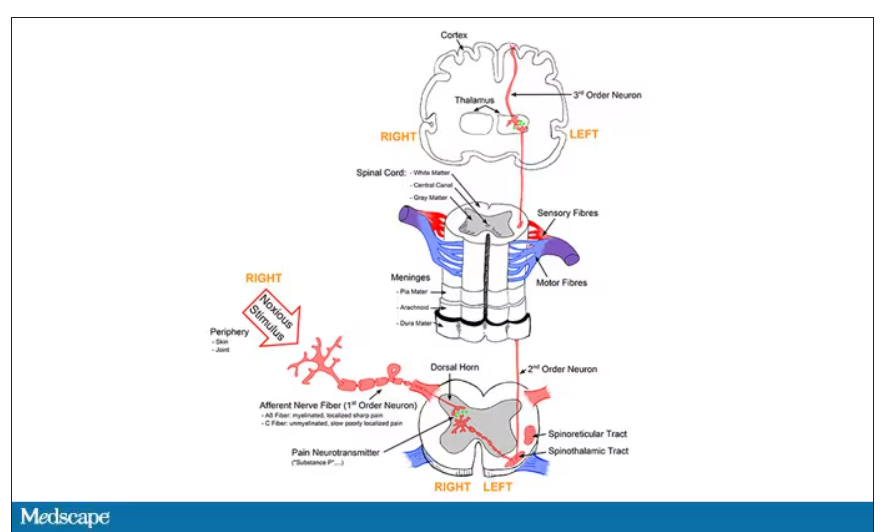

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

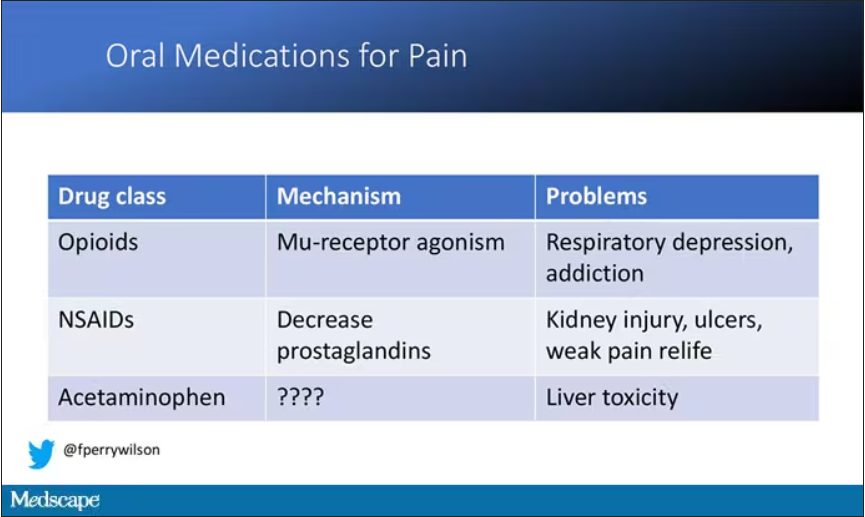

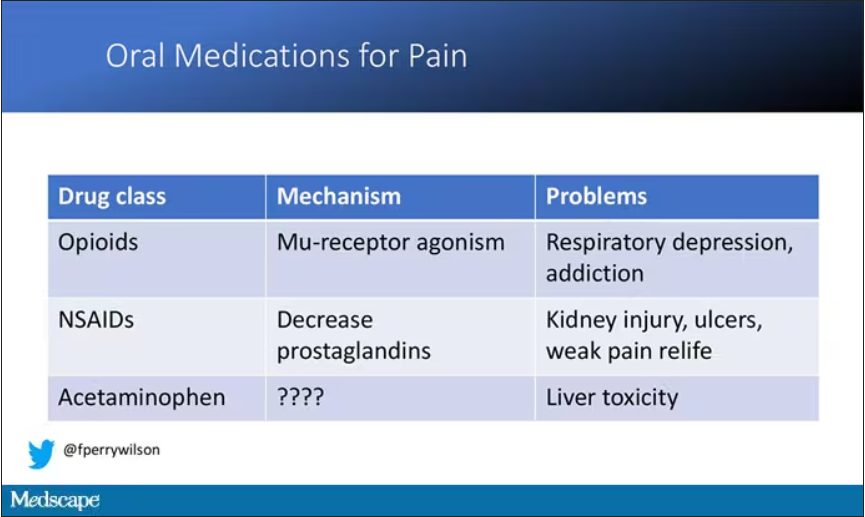

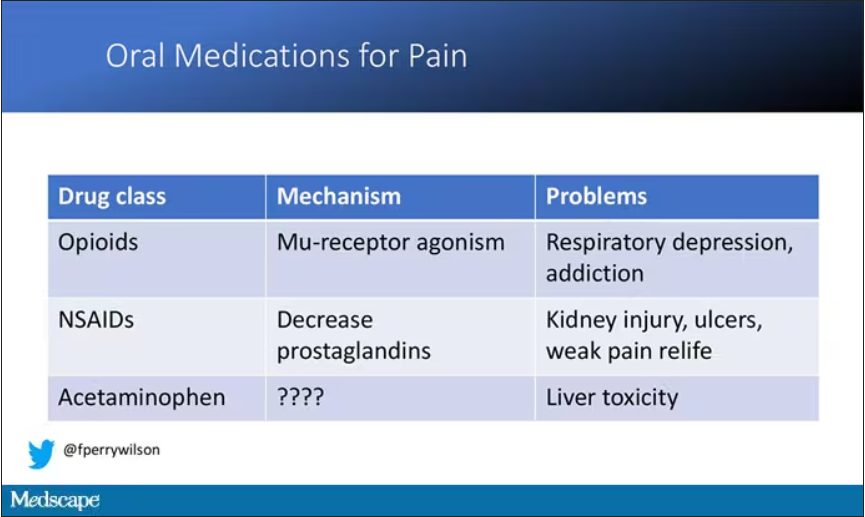

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

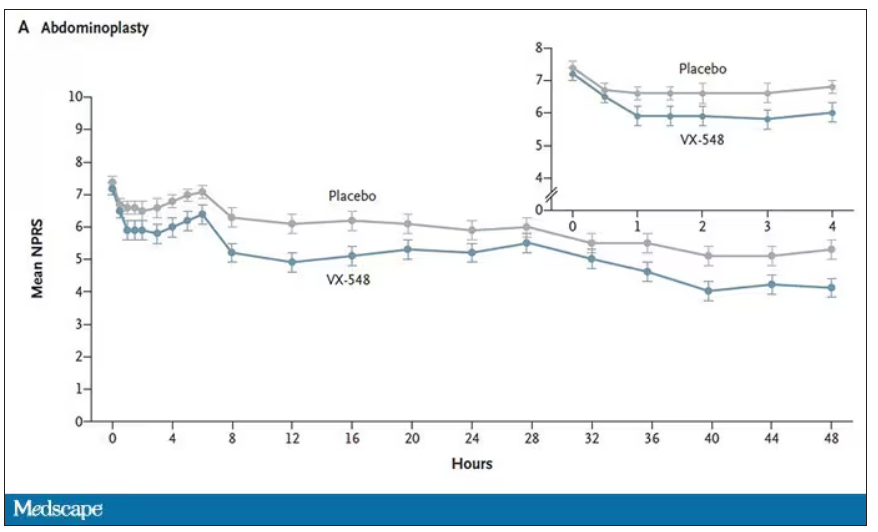

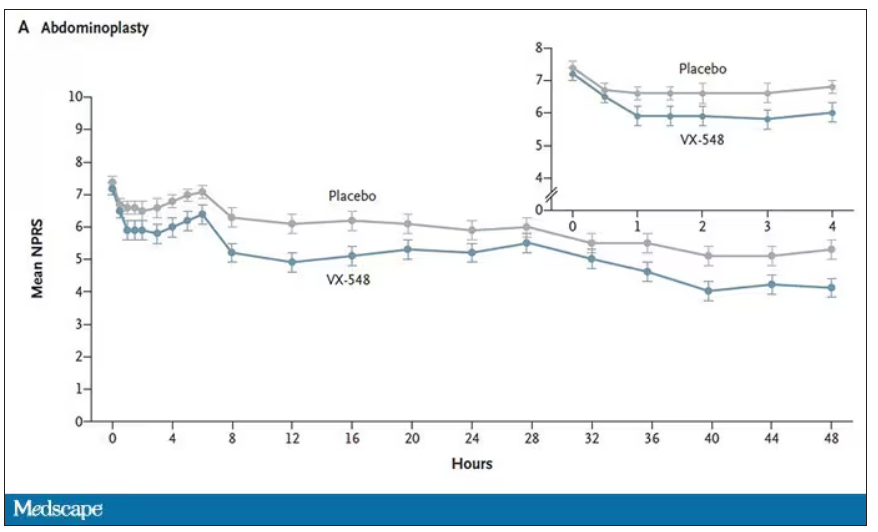

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

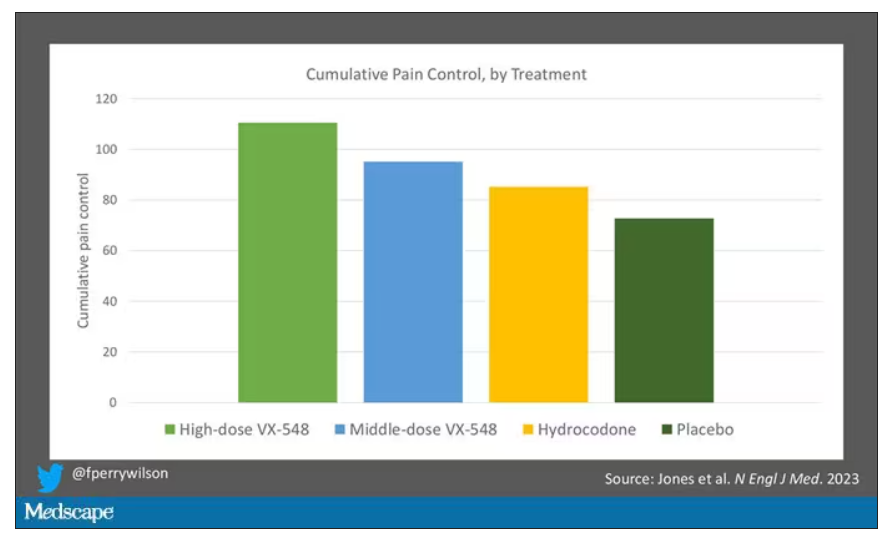

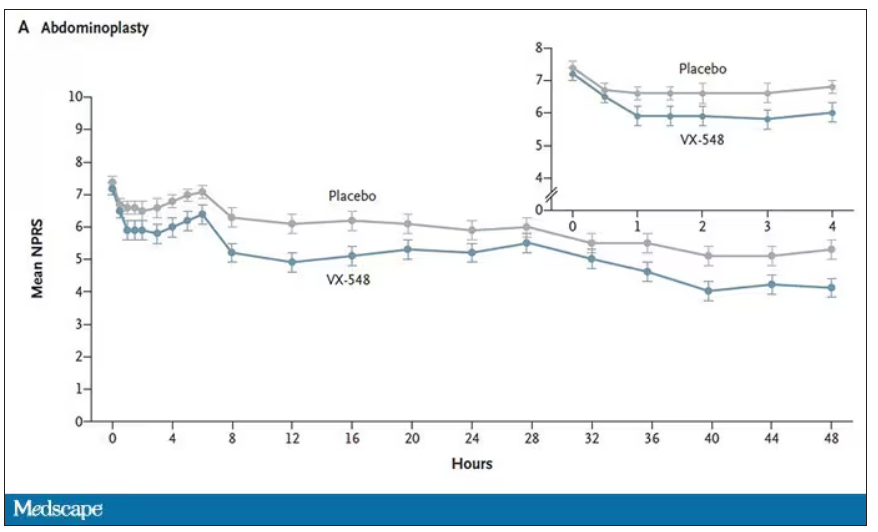

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

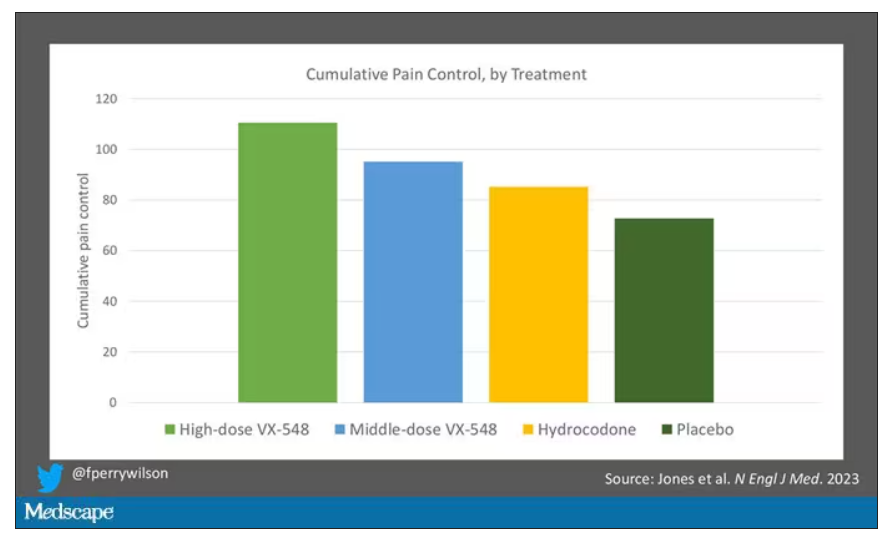

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

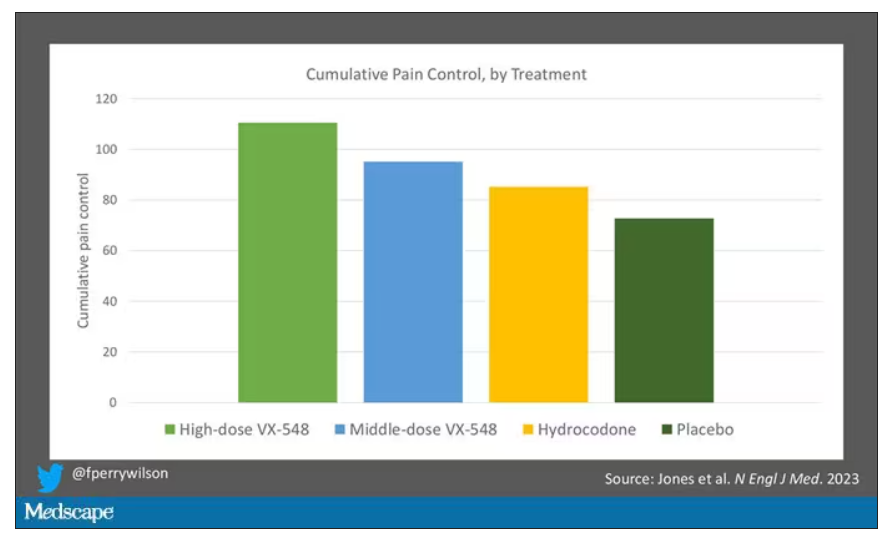

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

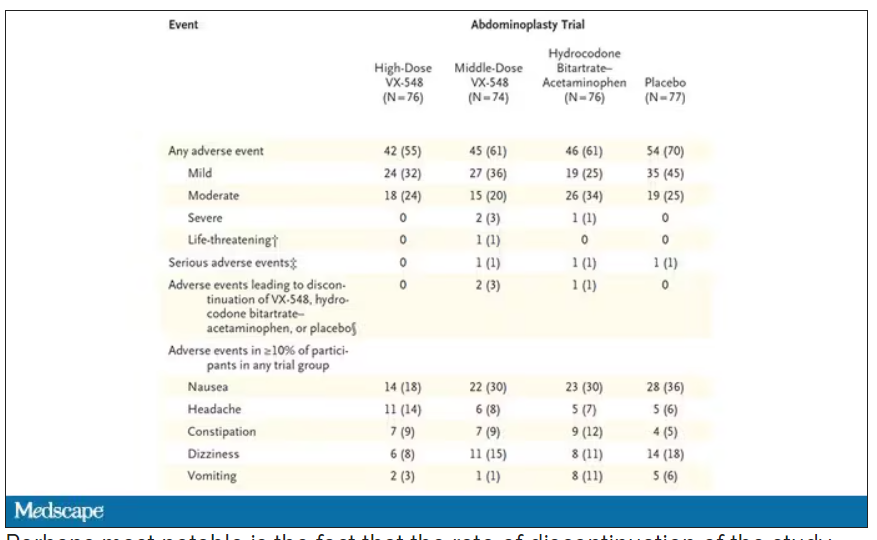

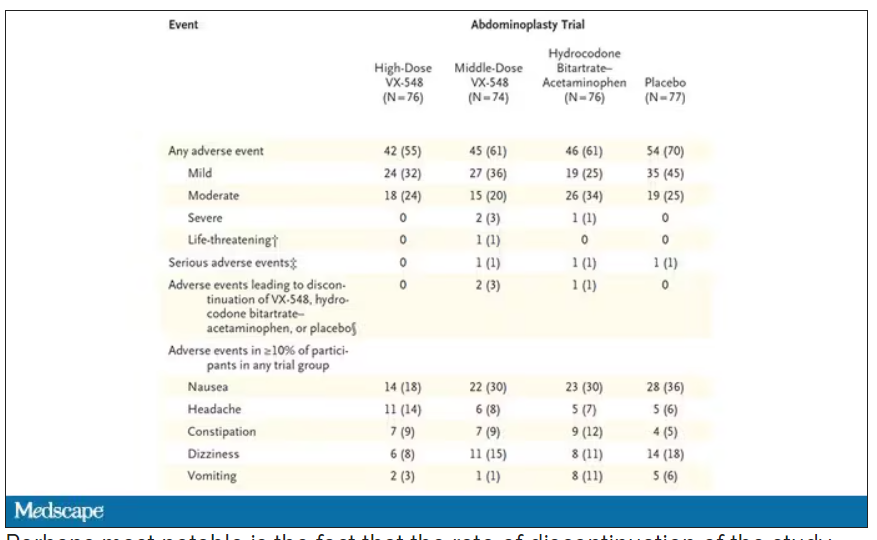

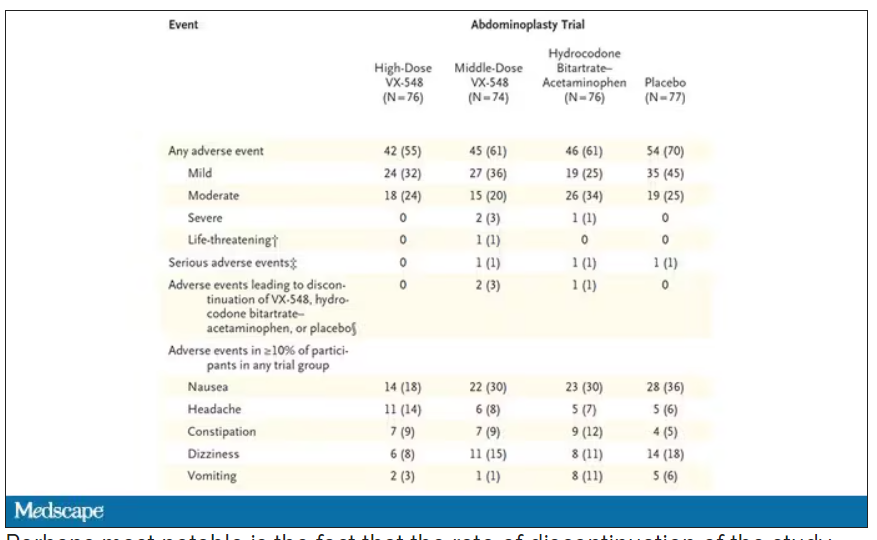

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Prescribing lifestyle changes: When medicine isn’t enough

In psychiatry, patients come to us with their list of symptoms, often a diagnosis they’ve made themselves, and the expectation that they will be given medication to fix their problem. Their diagnoses are often right on target – people often know if they are depressed or anxious, and Doctor Google may provide useful information.

Sometimes they want a specific medication, one they saw in a TV ad, or one that helped them in the past or has helped someone they know. As psychiatrists have focused more on their strengths as psychopharmacologists and less on psychotherapy, it gets easy for both the patient and the doctor to look to medication, cocktails, and titration as the only thing we do.

“My medicine stopped working,” is a line I commonly hear. Often the patient is on a complicated regimen that has been serving them well, and it seems unlikely that the five psychotropic medications they are taking have suddenly “stopped working.” An obvious exception is the SSRI “poop out” that can occur 6-12 months or more after beginning treatment. In addition, it’s important to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed, and that the generic formulations have not changed.

But as rates of mental illness increase, some of it spurred on by difficult times,

This is not to devalue our medications, but to help the patient see symptoms as having multiple factors and give them some means to intervene, in addition to medications. At the beginning of therapy, it is important to “prescribe” lifestyle changes that will facilitate the best possible outcomes.

Nonpharmaceutical prescriptions

Early in my career, people with alcohol use problems were told they needed to be substance free before they were candidates for antidepressants. While we no longer do that, it is still important to emphasize abstinence from addictive substances, and to recommend specific treatment when necessary.

Patients are often reluctant to see their use of alcohol, marijuana (it’s medical! It’s part of wellness!), or their pain medications as part of the problem, and this can be difficult. There have been times, after multiple medications have failed to help their symptoms, when I have said, “If you don’t get treatment for this problem, I am not going to be able to help you feel better” and that has been motivating for the patient.

There are other “prescriptions” to write. Regular sleep is essential for people with mood disorders, and this can be difficult for many patients, especially those who do shift work, or who have regular disruptions to their sleep from noise, pets, and children. Exercise is wonderful for the cardiovascular system, calms anxiety, and maintains strength, endurance, mobility, and quality of life as people age. But it can be a hard sell to people in a mental health crisis.

Nature is healing, and sunshine helps with maintaining circadian rhythms. For those who don’t exercise, I often “prescribe” 20 to 30 minutes a day of walking, preferably outside, during daylight hours, in a park or natural setting. For people with anxiety, it is important to check their caffeine consumption and to suggest ways to moderate it – moving to decaffeinated beverages or titrating down by mixing decaf with caffeinated.

Meditation is something that many people find helpful. For anxious people, it can be very difficult, and I will prescribe a specific instructional video course that I like on the well-being app InsightTimer – Sarah Blondin’s Learn How to Meditate in Seven Days. The sessions are approximately 10 minutes long, and that seems like the right amount of time for a beginner.

When people are very ill and don’t want to go into the hospital, I talk with them about things that happen in the hospital that are helpful, things they can try to mimic at home. In the hospital, patients don’t go to work, they don’t spend hours a day on the computer, and they are given a pass from dealing with the routine stresses of daily life.

I ask them to take time off work, to avoid as much stress as possible, to spend time with loved ones who give them comfort, and to avoid the people who leave them feeling drained or distressed. I ask them to engage in activities they find healing, to eat well, exercise, and avoid social media. In the hospital, I emphasize, they wake patients up in the morning, ask them to get out of bed and engage in therapeutic activities. They are fed and kept from intoxicants.

When it comes to nutrition, we know so little about how food affects mental health. I feel like it can’t hurt to ask people to avoid fast foods, soft drinks, and processed foods, and so I do.

And what about compliance? Of course, not everyone complies; not everyone is interested in making changes and these can be hard changes. I’ve recently started to recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear. Sometimes a bit of motivational interviewing can also be helpful in getting people to look at slowly moving toward making changes.

In prescribing lifestyle changes, it is important to offer most of these changes as suggestions, not as things we insist on, or that will leave the patient feeling ashamed if he doesn’t follow through. They should be discussed early in treatment so that patients don’t feel blamed for their illness or relapses. As with all the things we prescribe, some of these behavior changes help some of the people some of the time. Suggesting them, however, makes the strong statement that treating psychiatric disorders can be about more than passively swallowing a pill.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

In psychiatry, patients come to us with their list of symptoms, often a diagnosis they’ve made themselves, and the expectation that they will be given medication to fix their problem. Their diagnoses are often right on target – people often know if they are depressed or anxious, and Doctor Google may provide useful information.

Sometimes they want a specific medication, one they saw in a TV ad, or one that helped them in the past or has helped someone they know. As psychiatrists have focused more on their strengths as psychopharmacologists and less on psychotherapy, it gets easy for both the patient and the doctor to look to medication, cocktails, and titration as the only thing we do.

“My medicine stopped working,” is a line I commonly hear. Often the patient is on a complicated regimen that has been serving them well, and it seems unlikely that the five psychotropic medications they are taking have suddenly “stopped working.” An obvious exception is the SSRI “poop out” that can occur 6-12 months or more after beginning treatment. In addition, it’s important to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed, and that the generic formulations have not changed.

But as rates of mental illness increase, some of it spurred on by difficult times,

This is not to devalue our medications, but to help the patient see symptoms as having multiple factors and give them some means to intervene, in addition to medications. At the beginning of therapy, it is important to “prescribe” lifestyle changes that will facilitate the best possible outcomes.

Nonpharmaceutical prescriptions

Early in my career, people with alcohol use problems were told they needed to be substance free before they were candidates for antidepressants. While we no longer do that, it is still important to emphasize abstinence from addictive substances, and to recommend specific treatment when necessary.

Patients are often reluctant to see their use of alcohol, marijuana (it’s medical! It’s part of wellness!), or their pain medications as part of the problem, and this can be difficult. There have been times, after multiple medications have failed to help their symptoms, when I have said, “If you don’t get treatment for this problem, I am not going to be able to help you feel better” and that has been motivating for the patient.

There are other “prescriptions” to write. Regular sleep is essential for people with mood disorders, and this can be difficult for many patients, especially those who do shift work, or who have regular disruptions to their sleep from noise, pets, and children. Exercise is wonderful for the cardiovascular system, calms anxiety, and maintains strength, endurance, mobility, and quality of life as people age. But it can be a hard sell to people in a mental health crisis.

Nature is healing, and sunshine helps with maintaining circadian rhythms. For those who don’t exercise, I often “prescribe” 20 to 30 minutes a day of walking, preferably outside, during daylight hours, in a park or natural setting. For people with anxiety, it is important to check their caffeine consumption and to suggest ways to moderate it – moving to decaffeinated beverages or titrating down by mixing decaf with caffeinated.

Meditation is something that many people find helpful. For anxious people, it can be very difficult, and I will prescribe a specific instructional video course that I like on the well-being app InsightTimer – Sarah Blondin’s Learn How to Meditate in Seven Days. The sessions are approximately 10 minutes long, and that seems like the right amount of time for a beginner.

When people are very ill and don’t want to go into the hospital, I talk with them about things that happen in the hospital that are helpful, things they can try to mimic at home. In the hospital, patients don’t go to work, they don’t spend hours a day on the computer, and they are given a pass from dealing with the routine stresses of daily life.

I ask them to take time off work, to avoid as much stress as possible, to spend time with loved ones who give them comfort, and to avoid the people who leave them feeling drained or distressed. I ask them to engage in activities they find healing, to eat well, exercise, and avoid social media. In the hospital, I emphasize, they wake patients up in the morning, ask them to get out of bed and engage in therapeutic activities. They are fed and kept from intoxicants.

When it comes to nutrition, we know so little about how food affects mental health. I feel like it can’t hurt to ask people to avoid fast foods, soft drinks, and processed foods, and so I do.

And what about compliance? Of course, not everyone complies; not everyone is interested in making changes and these can be hard changes. I’ve recently started to recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear. Sometimes a bit of motivational interviewing can also be helpful in getting people to look at slowly moving toward making changes.

In prescribing lifestyle changes, it is important to offer most of these changes as suggestions, not as things we insist on, or that will leave the patient feeling ashamed if he doesn’t follow through. They should be discussed early in treatment so that patients don’t feel blamed for their illness or relapses. As with all the things we prescribe, some of these behavior changes help some of the people some of the time. Suggesting them, however, makes the strong statement that treating psychiatric disorders can be about more than passively swallowing a pill.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

In psychiatry, patients come to us with their list of symptoms, often a diagnosis they’ve made themselves, and the expectation that they will be given medication to fix their problem. Their diagnoses are often right on target – people often know if they are depressed or anxious, and Doctor Google may provide useful information.

Sometimes they want a specific medication, one they saw in a TV ad, or one that helped them in the past or has helped someone they know. As psychiatrists have focused more on their strengths as psychopharmacologists and less on psychotherapy, it gets easy for both the patient and the doctor to look to medication, cocktails, and titration as the only thing we do.

“My medicine stopped working,” is a line I commonly hear. Often the patient is on a complicated regimen that has been serving them well, and it seems unlikely that the five psychotropic medications they are taking have suddenly “stopped working.” An obvious exception is the SSRI “poop out” that can occur 6-12 months or more after beginning treatment. In addition, it’s important to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed, and that the generic formulations have not changed.

But as rates of mental illness increase, some of it spurred on by difficult times,

This is not to devalue our medications, but to help the patient see symptoms as having multiple factors and give them some means to intervene, in addition to medications. At the beginning of therapy, it is important to “prescribe” lifestyle changes that will facilitate the best possible outcomes.

Nonpharmaceutical prescriptions

Early in my career, people with alcohol use problems were told they needed to be substance free before they were candidates for antidepressants. While we no longer do that, it is still important to emphasize abstinence from addictive substances, and to recommend specific treatment when necessary.

Patients are often reluctant to see their use of alcohol, marijuana (it’s medical! It’s part of wellness!), or their pain medications as part of the problem, and this can be difficult. There have been times, after multiple medications have failed to help their symptoms, when I have said, “If you don’t get treatment for this problem, I am not going to be able to help you feel better” and that has been motivating for the patient.

There are other “prescriptions” to write. Regular sleep is essential for people with mood disorders, and this can be difficult for many patients, especially those who do shift work, or who have regular disruptions to their sleep from noise, pets, and children. Exercise is wonderful for the cardiovascular system, calms anxiety, and maintains strength, endurance, mobility, and quality of life as people age. But it can be a hard sell to people in a mental health crisis.

Nature is healing, and sunshine helps with maintaining circadian rhythms. For those who don’t exercise, I often “prescribe” 20 to 30 minutes a day of walking, preferably outside, during daylight hours, in a park or natural setting. For people with anxiety, it is important to check their caffeine consumption and to suggest ways to moderate it – moving to decaffeinated beverages or titrating down by mixing decaf with caffeinated.

Meditation is something that many people find helpful. For anxious people, it can be very difficult, and I will prescribe a specific instructional video course that I like on the well-being app InsightTimer – Sarah Blondin’s Learn How to Meditate in Seven Days. The sessions are approximately 10 minutes long, and that seems like the right amount of time for a beginner.

When people are very ill and don’t want to go into the hospital, I talk with them about things that happen in the hospital that are helpful, things they can try to mimic at home. In the hospital, patients don’t go to work, they don’t spend hours a day on the computer, and they are given a pass from dealing with the routine stresses of daily life.

I ask them to take time off work, to avoid as much stress as possible, to spend time with loved ones who give them comfort, and to avoid the people who leave them feeling drained or distressed. I ask them to engage in activities they find healing, to eat well, exercise, and avoid social media. In the hospital, I emphasize, they wake patients up in the morning, ask them to get out of bed and engage in therapeutic activities. They are fed and kept from intoxicants.

When it comes to nutrition, we know so little about how food affects mental health. I feel like it can’t hurt to ask people to avoid fast foods, soft drinks, and processed foods, and so I do.

And what about compliance? Of course, not everyone complies; not everyone is interested in making changes and these can be hard changes. I’ve recently started to recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear. Sometimes a bit of motivational interviewing can also be helpful in getting people to look at slowly moving toward making changes.

In prescribing lifestyle changes, it is important to offer most of these changes as suggestions, not as things we insist on, or that will leave the patient feeling ashamed if he doesn’t follow through. They should be discussed early in treatment so that patients don’t feel blamed for their illness or relapses. As with all the things we prescribe, some of these behavior changes help some of the people some of the time. Suggesting them, however, makes the strong statement that treating psychiatric disorders can be about more than passively swallowing a pill.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Will this trial help solve chronic back pain?

Chronic pain, and back pain in particular, is among the most frequent concerns for patients in the primary care setting. Roughly 8% of adults in the United States say they suffer from chronic low back pain, and many of them say the pain is significant enough to impair their ability to move, work, and otherwise enjoy life. All this, despite decades of research and countless millions in funding to find the optimal approach to treating chronic pain.

As the United States crawls out of the opioid epidemic, a group of pain specialists is hoping to identify effective, personalized approaches to managing back pain. Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of anesthesiology, internal medicine, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is helping lead the BEST trial. With projected enrollment of nearly 800 patients, BEST will be the largest federally funded clinical trial of interventions to treat chronic low back pain.

In an interview, The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are your thoughts on the current state of primary care physicians’ understanding and management of pain?

Primary care physicians need a lot of help in demystifying the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of pain, but back pain is a really good place to start. When it comes to back pain, most primary care physicians are not any more knowledgeable than a layperson.

What has the opioid debacle-cum-tragedy taught you about pain management, particular as regards people with chronic pain?

I don’t feel opioids should ever be used to treat chronic low back pain. The few long-term studies that have been performed using opioids for longer than 3 months suggest that they often make pain worse rather than just failing to make pain better – and we know they are associated with a significantly increased all-cause mortality with increased deaths from myocardial infarction, accidents, and suicides, in addition to overdose.

Given how many patients experience back pain, how did we come to the point at which primary care physicians are so ill equipped?

We’ve had terrible pain curricula in medical schools. To give you an example: I’m one of the leading pain experts in the world and I’m not allowed to teach our medical students their pain curriculum. The students learn about neurophysiology and the anatomy of the nerves, not what’s relevant in pain.

This is notorious in medical school: Curricula are almost impossible to modify and change. So it starts with poor training in medical school. And then, regardless of what education they do or don’t get in medical school, a lot of their education about pain management is through our residencies – mainly in inpatient settings, where you’re really seeing the management of acute pain and not the management of chronic pain.

People get more accustomed to managing acute pain, where opioids are a reasonable option. It’s just that when you start managing subacute or chronic pain, opioids don’t work as well.

The other big problem is that historically, most people trained in medicine think that if you have pain in your elbow, there’s got to be something wrong in your elbow. This third mechanism of pain, central sensitization – or nociplastic pain – the kind of pain that we see in fibromyalgia, headache, and low back pain, where the pain is coming from the brain – that’s confusing to people. People can have pain without any damage or inflammation to that region of the body.

Physicians are trained that if there’s pain, there’s something wrong and we have to do surgery or there’s been some trauma. Most chronic pain is none of that. There’s a big disconnect between how people are trained, and then when they go out and are seeing a tremendous number of people with chronic pain.

What are the different types of pain, and how should they inform clinicians’ understanding about what approaches might work for managing their patients in pain?

The way the central nervous system responds to pain is analogous to the loudness of an electric guitar. You can make an electric guitar louder either by strumming the strings harder or by turning up the amplifier. For many people with fibromyalgia, low back pain, and endometriosis, for example, the problem is really more that the amplifier is turned up too high rather than its being that the guitar is strummed too strongly. That kind of pain where the pain is not due to anatomic damage or inflammation is particularly flummoxing for providers.

Can you explain the design of the new study?

It’s a 13-site study looking at four treatments: enhanced self-care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and duloxetine. It’s a big precision medicine trial, trying to take everything we’ve learned and putting it all into one big study.

We’re using a SMART design, which randomizes people to two of those treatments, unless they are very much improved from the first treatment. To be eligible for the trial, you have to be able to be randomized to three of the four treatments, and people can’t choose which of the four they get.

We give them one of those treatments for 12 weeks, and at the end of 12 weeks we make the call – “Did you respond or not respond?” – and then we go back to the phenotypic data we collected at the beginning of that trial and say, “What information at baseline that we collected predicts that someone is going to respond better to duloxetine or worse to duloxetine?” And then we create the phenotype that responds best to each of those four treatments.

None of our treatments works so well that someone doesn’t end up getting randomized to a second treatment. About 85% of people so far need a second treatment because they still have enough pain that they want more relief. But the nice thing about that is we’ve already done all the functional brain imaging and all these really expensive and time-consuming things.

We’re hoping to have around 700-800 people total in this trial, which means that around 170 people will get randomized to each of the four initial treatments. No one’s ever done a study that has functional brain imaging and all these other things in it with more than 80 or 100 people. The scale of this is totally unprecedented.

Given that the individual therapies don’t appear to be all that successful on their own, what is your goal?

The primary aim is to match the phenotypic characteristics of a patient with chronic low back pain with treatment response to each of these four treatments. So at the end, we can give clinicians information on which of the patients is going to respond to physical therapy, for instance.

Right now, about one out of three people respond to most treatments for pain. We think by doing a trial like this, we can take treatments that work in one out of three people and make them work in one out of two or two out of three people just by using them in the right people.

How do you differentiate between these types of pain in your study?

We phenotype people by asking them a number of questions. We also do brain imaging, look at their back with MRI, test biomechanics, and then give them four different treatments that we know work in groups of people with low back pain.

We think one of the first parts of the phenotype is, do they have pain just in their back? Or do they have pain in their back plus a lot of other body regions? Because the more body regions that people have pain in, the more likely it is that this is an amplifier problem rather than a guitar problem.

Treatments like physical therapy, surgery, and injections are going to work better for people in whom the pain is a guitar problem rather than an amplifier problem. And drugs like duloxetine, which works in the brain, and cognitive-behavioral therapy are going to work a lot better in the people with pain in multiple sites besides the back.

To pick up on your metaphor, do any symptoms help clinicians differentiate between the guitar and the amplifier?

Sleep problems, fatigue, memory problems, and mood problems are common in patients with chronic pain and are more common with amplifier pain. Because again, those are all central nervous system problems. And so we see that the people that have anxiety, depression, and a lot of distress are more likely to have this kind of pain.

Does medical imaging help?

There’s a terrible relationship between what you see on an MRI of the back and whether someone has pain or how severe the pain is going to be. There’s always going to be individuals that have a lot of anatomic damage who don’t have any pain because they happen to be on the other end of the continuum from fibromyalgia; they’re actually pain-insensitive people.

What are your thoughts about ketamine as a possible treatment for chronic pain?

I have a mentee who’s doing a ketamine trial. We’re doing psilocybin trials in patients with fibromyalgia. Ketamine is such a dirty drug; it has so many different mechanisms of action. It does have some psychedelic effects, but it also is an NMDA blocker. It really has so many different effects.

I think it’s being thrown around like water in settings where we don’t yet know it to be efficacious. Even the data in treatment-refractory depression are pretty weak, but we’re so desperate to do something for those patients. If you’re trying to harness the psychedelic properties of ketamine, I think there’s other psychedelics that are a lot more interesting, which is why we’re using psilocybin for a subset of patients. Most of us in the pain field think that the psychedelics will work best for the people with chronic pain who have a lot of comorbid psychiatric illness, especially the ones with a lot of trauma. These drugs will allow us therapeutically to get at a lot of these patients with the side-by-side psychotherapy that’s being done as people are getting care in the medicalized setting.

Dr. Clauw reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Tonix, Theravance, Zynerba, Samumed, Aptinyx, Daiichi Sankyo, Intec, Regeneron, Teva, Lundbeck, Virios, and Cerephex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic pain, and back pain in particular, is among the most frequent concerns for patients in the primary care setting. Roughly 8% of adults in the United States say they suffer from chronic low back pain, and many of them say the pain is significant enough to impair their ability to move, work, and otherwise enjoy life. All this, despite decades of research and countless millions in funding to find the optimal approach to treating chronic pain.

As the United States crawls out of the opioid epidemic, a group of pain specialists is hoping to identify effective, personalized approaches to managing back pain. Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of anesthesiology, internal medicine, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is helping lead the BEST trial. With projected enrollment of nearly 800 patients, BEST will be the largest federally funded clinical trial of interventions to treat chronic low back pain.

In an interview, The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are your thoughts on the current state of primary care physicians’ understanding and management of pain?

Primary care physicians need a lot of help in demystifying the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of pain, but back pain is a really good place to start. When it comes to back pain, most primary care physicians are not any more knowledgeable than a layperson.

What has the opioid debacle-cum-tragedy taught you about pain management, particular as regards people with chronic pain?

I don’t feel opioids should ever be used to treat chronic low back pain. The few long-term studies that have been performed using opioids for longer than 3 months suggest that they often make pain worse rather than just failing to make pain better – and we know they are associated with a significantly increased all-cause mortality with increased deaths from myocardial infarction, accidents, and suicides, in addition to overdose.

Given how many patients experience back pain, how did we come to the point at which primary care physicians are so ill equipped?

We’ve had terrible pain curricula in medical schools. To give you an example: I’m one of the leading pain experts in the world and I’m not allowed to teach our medical students their pain curriculum. The students learn about neurophysiology and the anatomy of the nerves, not what’s relevant in pain.

This is notorious in medical school: Curricula are almost impossible to modify and change. So it starts with poor training in medical school. And then, regardless of what education they do or don’t get in medical school, a lot of their education about pain management is through our residencies – mainly in inpatient settings, where you’re really seeing the management of acute pain and not the management of chronic pain.

People get more accustomed to managing acute pain, where opioids are a reasonable option. It’s just that when you start managing subacute or chronic pain, opioids don’t work as well.

The other big problem is that historically, most people trained in medicine think that if you have pain in your elbow, there’s got to be something wrong in your elbow. This third mechanism of pain, central sensitization – or nociplastic pain – the kind of pain that we see in fibromyalgia, headache, and low back pain, where the pain is coming from the brain – that’s confusing to people. People can have pain without any damage or inflammation to that region of the body.

Physicians are trained that if there’s pain, there’s something wrong and we have to do surgery or there’s been some trauma. Most chronic pain is none of that. There’s a big disconnect between how people are trained, and then when they go out and are seeing a tremendous number of people with chronic pain.

What are the different types of pain, and how should they inform clinicians’ understanding about what approaches might work for managing their patients in pain?

The way the central nervous system responds to pain is analogous to the loudness of an electric guitar. You can make an electric guitar louder either by strumming the strings harder or by turning up the amplifier. For many people with fibromyalgia, low back pain, and endometriosis, for example, the problem is really more that the amplifier is turned up too high rather than its being that the guitar is strummed too strongly. That kind of pain where the pain is not due to anatomic damage or inflammation is particularly flummoxing for providers.

Can you explain the design of the new study?

It’s a 13-site study looking at four treatments: enhanced self-care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and duloxetine. It’s a big precision medicine trial, trying to take everything we’ve learned and putting it all into one big study.

We’re using a SMART design, which randomizes people to two of those treatments, unless they are very much improved from the first treatment. To be eligible for the trial, you have to be able to be randomized to three of the four treatments, and people can’t choose which of the four they get.

We give them one of those treatments for 12 weeks, and at the end of 12 weeks we make the call – “Did you respond or not respond?” – and then we go back to the phenotypic data we collected at the beginning of that trial and say, “What information at baseline that we collected predicts that someone is going to respond better to duloxetine or worse to duloxetine?” And then we create the phenotype that responds best to each of those four treatments.

None of our treatments works so well that someone doesn’t end up getting randomized to a second treatment. About 85% of people so far need a second treatment because they still have enough pain that they want more relief. But the nice thing about that is we’ve already done all the functional brain imaging and all these really expensive and time-consuming things.

We’re hoping to have around 700-800 people total in this trial, which means that around 170 people will get randomized to each of the four initial treatments. No one’s ever done a study that has functional brain imaging and all these other things in it with more than 80 or 100 people. The scale of this is totally unprecedented.

Given that the individual therapies don’t appear to be all that successful on their own, what is your goal?

The primary aim is to match the phenotypic characteristics of a patient with chronic low back pain with treatment response to each of these four treatments. So at the end, we can give clinicians information on which of the patients is going to respond to physical therapy, for instance.

Right now, about one out of three people respond to most treatments for pain. We think by doing a trial like this, we can take treatments that work in one out of three people and make them work in one out of two or two out of three people just by using them in the right people.

How do you differentiate between these types of pain in your study?

We phenotype people by asking them a number of questions. We also do brain imaging, look at their back with MRI, test biomechanics, and then give them four different treatments that we know work in groups of people with low back pain.

We think one of the first parts of the phenotype is, do they have pain just in their back? Or do they have pain in their back plus a lot of other body regions? Because the more body regions that people have pain in, the more likely it is that this is an amplifier problem rather than a guitar problem.

Treatments like physical therapy, surgery, and injections are going to work better for people in whom the pain is a guitar problem rather than an amplifier problem. And drugs like duloxetine, which works in the brain, and cognitive-behavioral therapy are going to work a lot better in the people with pain in multiple sites besides the back.

To pick up on your metaphor, do any symptoms help clinicians differentiate between the guitar and the amplifier?

Sleep problems, fatigue, memory problems, and mood problems are common in patients with chronic pain and are more common with amplifier pain. Because again, those are all central nervous system problems. And so we see that the people that have anxiety, depression, and a lot of distress are more likely to have this kind of pain.

Does medical imaging help?

There’s a terrible relationship between what you see on an MRI of the back and whether someone has pain or how severe the pain is going to be. There’s always going to be individuals that have a lot of anatomic damage who don’t have any pain because they happen to be on the other end of the continuum from fibromyalgia; they’re actually pain-insensitive people.

What are your thoughts about ketamine as a possible treatment for chronic pain?

I have a mentee who’s doing a ketamine trial. We’re doing psilocybin trials in patients with fibromyalgia. Ketamine is such a dirty drug; it has so many different mechanisms of action. It does have some psychedelic effects, but it also is an NMDA blocker. It really has so many different effects.

I think it’s being thrown around like water in settings where we don’t yet know it to be efficacious. Even the data in treatment-refractory depression are pretty weak, but we’re so desperate to do something for those patients. If you’re trying to harness the psychedelic properties of ketamine, I think there’s other psychedelics that are a lot more interesting, which is why we’re using psilocybin for a subset of patients. Most of us in the pain field think that the psychedelics will work best for the people with chronic pain who have a lot of comorbid psychiatric illness, especially the ones with a lot of trauma. These drugs will allow us therapeutically to get at a lot of these patients with the side-by-side psychotherapy that’s being done as people are getting care in the medicalized setting.

Dr. Clauw reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Tonix, Theravance, Zynerba, Samumed, Aptinyx, Daiichi Sankyo, Intec, Regeneron, Teva, Lundbeck, Virios, and Cerephex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic pain, and back pain in particular, is among the most frequent concerns for patients in the primary care setting. Roughly 8% of adults in the United States say they suffer from chronic low back pain, and many of them say the pain is significant enough to impair their ability to move, work, and otherwise enjoy life. All this, despite decades of research and countless millions in funding to find the optimal approach to treating chronic pain.

As the United States crawls out of the opioid epidemic, a group of pain specialists is hoping to identify effective, personalized approaches to managing back pain. Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of anesthesiology, internal medicine, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is helping lead the BEST trial. With projected enrollment of nearly 800 patients, BEST will be the largest federally funded clinical trial of interventions to treat chronic low back pain.

In an interview, The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are your thoughts on the current state of primary care physicians’ understanding and management of pain?

Primary care physicians need a lot of help in demystifying the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of pain, but back pain is a really good place to start. When it comes to back pain, most primary care physicians are not any more knowledgeable than a layperson.

What has the opioid debacle-cum-tragedy taught you about pain management, particular as regards people with chronic pain?

I don’t feel opioids should ever be used to treat chronic low back pain. The few long-term studies that have been performed using opioids for longer than 3 months suggest that they often make pain worse rather than just failing to make pain better – and we know they are associated with a significantly increased all-cause mortality with increased deaths from myocardial infarction, accidents, and suicides, in addition to overdose.

Given how many patients experience back pain, how did we come to the point at which primary care physicians are so ill equipped?

We’ve had terrible pain curricula in medical schools. To give you an example: I’m one of the leading pain experts in the world and I’m not allowed to teach our medical students their pain curriculum. The students learn about neurophysiology and the anatomy of the nerves, not what’s relevant in pain.

This is notorious in medical school: Curricula are almost impossible to modify and change. So it starts with poor training in medical school. And then, regardless of what education they do or don’t get in medical school, a lot of their education about pain management is through our residencies – mainly in inpatient settings, where you’re really seeing the management of acute pain and not the management of chronic pain.

People get more accustomed to managing acute pain, where opioids are a reasonable option. It’s just that when you start managing subacute or chronic pain, opioids don’t work as well.

The other big problem is that historically, most people trained in medicine think that if you have pain in your elbow, there’s got to be something wrong in your elbow. This third mechanism of pain, central sensitization – or nociplastic pain – the kind of pain that we see in fibromyalgia, headache, and low back pain, where the pain is coming from the brain – that’s confusing to people. People can have pain without any damage or inflammation to that region of the body.

Physicians are trained that if there’s pain, there’s something wrong and we have to do surgery or there’s been some trauma. Most chronic pain is none of that. There’s a big disconnect between how people are trained, and then when they go out and are seeing a tremendous number of people with chronic pain.

What are the different types of pain, and how should they inform clinicians’ understanding about what approaches might work for managing their patients in pain?

The way the central nervous system responds to pain is analogous to the loudness of an electric guitar. You can make an electric guitar louder either by strumming the strings harder or by turning up the amplifier. For many people with fibromyalgia, low back pain, and endometriosis, for example, the problem is really more that the amplifier is turned up too high rather than its being that the guitar is strummed too strongly. That kind of pain where the pain is not due to anatomic damage or inflammation is particularly flummoxing for providers.

Can you explain the design of the new study?

It’s a 13-site study looking at four treatments: enhanced self-care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and duloxetine. It’s a big precision medicine trial, trying to take everything we’ve learned and putting it all into one big study.

We’re using a SMART design, which randomizes people to two of those treatments, unless they are very much improved from the first treatment. To be eligible for the trial, you have to be able to be randomized to three of the four treatments, and people can’t choose which of the four they get.

We give them one of those treatments for 12 weeks, and at the end of 12 weeks we make the call – “Did you respond or not respond?” – and then we go back to the phenotypic data we collected at the beginning of that trial and say, “What information at baseline that we collected predicts that someone is going to respond better to duloxetine or worse to duloxetine?” And then we create the phenotype that responds best to each of those four treatments.

None of our treatments works so well that someone doesn’t end up getting randomized to a second treatment. About 85% of people so far need a second treatment because they still have enough pain that they want more relief. But the nice thing about that is we’ve already done all the functional brain imaging and all these really expensive and time-consuming things.

We’re hoping to have around 700-800 people total in this trial, which means that around 170 people will get randomized to each of the four initial treatments. No one’s ever done a study that has functional brain imaging and all these other things in it with more than 80 or 100 people. The scale of this is totally unprecedented.

Given that the individual therapies don’t appear to be all that successful on their own, what is your goal?

The primary aim is to match the phenotypic characteristics of a patient with chronic low back pain with treatment response to each of these four treatments. So at the end, we can give clinicians information on which of the patients is going to respond to physical therapy, for instance.

Right now, about one out of three people respond to most treatments for pain. We think by doing a trial like this, we can take treatments that work in one out of three people and make them work in one out of two or two out of three people just by using them in the right people.

How do you differentiate between these types of pain in your study?

We phenotype people by asking them a number of questions. We also do brain imaging, look at their back with MRI, test biomechanics, and then give them four different treatments that we know work in groups of people with low back pain.

We think one of the first parts of the phenotype is, do they have pain just in their back? Or do they have pain in their back plus a lot of other body regions? Because the more body regions that people have pain in, the more likely it is that this is an amplifier problem rather than a guitar problem.

Treatments like physical therapy, surgery, and injections are going to work better for people in whom the pain is a guitar problem rather than an amplifier problem. And drugs like duloxetine, which works in the brain, and cognitive-behavioral therapy are going to work a lot better in the people with pain in multiple sites besides the back.

To pick up on your metaphor, do any symptoms help clinicians differentiate between the guitar and the amplifier?

Sleep problems, fatigue, memory problems, and mood problems are common in patients with chronic pain and are more common with amplifier pain. Because again, those are all central nervous system problems. And so we see that the people that have anxiety, depression, and a lot of distress are more likely to have this kind of pain.

Does medical imaging help?

There’s a terrible relationship between what you see on an MRI of the back and whether someone has pain or how severe the pain is going to be. There’s always going to be individuals that have a lot of anatomic damage who don’t have any pain because they happen to be on the other end of the continuum from fibromyalgia; they’re actually pain-insensitive people.

What are your thoughts about ketamine as a possible treatment for chronic pain?

I have a mentee who’s doing a ketamine trial. We’re doing psilocybin trials in patients with fibromyalgia. Ketamine is such a dirty drug; it has so many different mechanisms of action. It does have some psychedelic effects, but it also is an NMDA blocker. It really has so many different effects.

I think it’s being thrown around like water in settings where we don’t yet know it to be efficacious. Even the data in treatment-refractory depression are pretty weak, but we’re so desperate to do something for those patients. If you’re trying to harness the psychedelic properties of ketamine, I think there’s other psychedelics that are a lot more interesting, which is why we’re using psilocybin for a subset of patients. Most of us in the pain field think that the psychedelics will work best for the people with chronic pain who have a lot of comorbid psychiatric illness, especially the ones with a lot of trauma. These drugs will allow us therapeutically to get at a lot of these patients with the side-by-side psychotherapy that’s being done as people are getting care in the medicalized setting.

Dr. Clauw reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Tonix, Theravance, Zynerba, Samumed, Aptinyx, Daiichi Sankyo, Intec, Regeneron, Teva, Lundbeck, Virios, and Cerephex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Who owns your genes?

Who owns your genes? The assumption of any sane person would be that he or she owns his or her own genes. I mean, how dumb a question is that?

Yet, in 2007, Dov Michaeli, MD, PhD, described how an American company had claimed ownership of genetic materials and believed that it had the right to commercialize those naturally occurring bits of DNA. Myriad Genetics began by patenting mutations of BRCA. Dr. Michaeli issued a call for action to support early efforts to pass legislation to restore and preserve individual ownership of one’s own genes. This is a historically important quick read/watch/listen. Give it a click.

In related legislation, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), originally introduced by New York Rep. Louise Slaughter in 1995, was ultimately spearheaded by California Rep. Xavier Becerra (now Secretary of Health & Human Services) to passage by the House of Representatives on April 25, 2007, by a vote of 420-9-3. Led by Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, it was passed by the Senate on April 24, 2008, by a vote of 95-0. President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on May 21, 2008.

GINA is a landmark piece of legislation that protects Americans. It prohibits employers and health insurers from discriminating against people on the basis of their genetic information, and it also prohibits the use of genetic information in life insurance and long-term care insurance.

Its impact has been immense. GINA has been indispensable in promoting progress in the field of human genetics. By safeguarding individuals against discrimination based on genetic information, it has encouraged broader participation in research, built public trust, and stimulated advancements in genetic testing and personalized medicine. GINA’s impact extends beyond borders and has influenced much of the rest of the world.

As important as GINA was to the field, more was needed. National legislation to protect ownership of genetic materials has, despite many attempts, still not become law in the United States. However, in our system of divided government and balance of power, we also have independent courts.

June 13, 2023, was the 10th anniversary of another landmark event. The legal case is that of the Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, a Salt Lake City–based biotech company that held patents on isolated DNA sequences associated with breast and ovarian cancer. The AMP, joined by several other organizations and researchers, challenged Myriad’s gene patents, arguing that human genes are naturally occurring and, therefore, should not be subject to patenting. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court held that naturally occurring DNA segments are products of nature and therefore are not eligible for patent protection.

This was a pivotal decision in the field of human genetics and had a broad impact on genetic research. The decision clarified that naturally occurring DNA sequences cannot be patented, which means that researchers are free to use these sequences in their research without fear of patent infringement. This has led to a vast increase in the amount of genetic research being conducted, and it has also led to the development of new genetic tests and treatments.

The numbers of genetic research papers published in scientific journals and of genetic tests available to consumers have increased significantly, while the cost of genetic testing has decreased significantly. The AMP v. Myriad decision is likely to continue to have an impact for many years to come.

Thank you, common sense, activist American molecular pathologists, Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court for siding with the people.Dr. Lundbert is editor in chief of Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Who owns your genes? The assumption of any sane person would be that he or she owns his or her own genes. I mean, how dumb a question is that?

Yet, in 2007, Dov Michaeli, MD, PhD, described how an American company had claimed ownership of genetic materials and believed that it had the right to commercialize those naturally occurring bits of DNA. Myriad Genetics began by patenting mutations of BRCA. Dr. Michaeli issued a call for action to support early efforts to pass legislation to restore and preserve individual ownership of one’s own genes. This is a historically important quick read/watch/listen. Give it a click.

In related legislation, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), originally introduced by New York Rep. Louise Slaughter in 1995, was ultimately spearheaded by California Rep. Xavier Becerra (now Secretary of Health & Human Services) to passage by the House of Representatives on April 25, 2007, by a vote of 420-9-3. Led by Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, it was passed by the Senate on April 24, 2008, by a vote of 95-0. President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on May 21, 2008.

GINA is a landmark piece of legislation that protects Americans. It prohibits employers and health insurers from discriminating against people on the basis of their genetic information, and it also prohibits the use of genetic information in life insurance and long-term care insurance.

Its impact has been immense. GINA has been indispensable in promoting progress in the field of human genetics. By safeguarding individuals against discrimination based on genetic information, it has encouraged broader participation in research, built public trust, and stimulated advancements in genetic testing and personalized medicine. GINA’s impact extends beyond borders and has influenced much of the rest of the world.

As important as GINA was to the field, more was needed. National legislation to protect ownership of genetic materials has, despite many attempts, still not become law in the United States. However, in our system of divided government and balance of power, we also have independent courts.

June 13, 2023, was the 10th anniversary of another landmark event. The legal case is that of the Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, a Salt Lake City–based biotech company that held patents on isolated DNA sequences associated with breast and ovarian cancer. The AMP, joined by several other organizations and researchers, challenged Myriad’s gene patents, arguing that human genes are naturally occurring and, therefore, should not be subject to patenting. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court held that naturally occurring DNA segments are products of nature and therefore are not eligible for patent protection.

This was a pivotal decision in the field of human genetics and had a broad impact on genetic research. The decision clarified that naturally occurring DNA sequences cannot be patented, which means that researchers are free to use these sequences in their research without fear of patent infringement. This has led to a vast increase in the amount of genetic research being conducted, and it has also led to the development of new genetic tests and treatments.

The numbers of genetic research papers published in scientific journals and of genetic tests available to consumers have increased significantly, while the cost of genetic testing has decreased significantly. The AMP v. Myriad decision is likely to continue to have an impact for many years to come.

Thank you, common sense, activist American molecular pathologists, Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court for siding with the people.Dr. Lundbert is editor in chief of Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Who owns your genes? The assumption of any sane person would be that he or she owns his or her own genes. I mean, how dumb a question is that?

Yet, in 2007, Dov Michaeli, MD, PhD, described how an American company had claimed ownership of genetic materials and believed that it had the right to commercialize those naturally occurring bits of DNA. Myriad Genetics began by patenting mutations of BRCA. Dr. Michaeli issued a call for action to support early efforts to pass legislation to restore and preserve individual ownership of one’s own genes. This is a historically important quick read/watch/listen. Give it a click.

In related legislation, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), originally introduced by New York Rep. Louise Slaughter in 1995, was ultimately spearheaded by California Rep. Xavier Becerra (now Secretary of Health & Human Services) to passage by the House of Representatives on April 25, 2007, by a vote of 420-9-3. Led by Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, it was passed by the Senate on April 24, 2008, by a vote of 95-0. President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on May 21, 2008.

GINA is a landmark piece of legislation that protects Americans. It prohibits employers and health insurers from discriminating against people on the basis of their genetic information, and it also prohibits the use of genetic information in life insurance and long-term care insurance.

Its impact has been immense. GINA has been indispensable in promoting progress in the field of human genetics. By safeguarding individuals against discrimination based on genetic information, it has encouraged broader participation in research, built public trust, and stimulated advancements in genetic testing and personalized medicine. GINA’s impact extends beyond borders and has influenced much of the rest of the world.

As important as GINA was to the field, more was needed. National legislation to protect ownership of genetic materials has, despite many attempts, still not become law in the United States. However, in our system of divided government and balance of power, we also have independent courts.

June 13, 2023, was the 10th anniversary of another landmark event. The legal case is that of the Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, a Salt Lake City–based biotech company that held patents on isolated DNA sequences associated with breast and ovarian cancer. The AMP, joined by several other organizations and researchers, challenged Myriad’s gene patents, arguing that human genes are naturally occurring and, therefore, should not be subject to patenting. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court held that naturally occurring DNA segments are products of nature and therefore are not eligible for patent protection.

This was a pivotal decision in the field of human genetics and had a broad impact on genetic research. The decision clarified that naturally occurring DNA sequences cannot be patented, which means that researchers are free to use these sequences in their research without fear of patent infringement. This has led to a vast increase in the amount of genetic research being conducted, and it has also led to the development of new genetic tests and treatments.

The numbers of genetic research papers published in scientific journals and of genetic tests available to consumers have increased significantly, while the cost of genetic testing has decreased significantly. The AMP v. Myriad decision is likely to continue to have an impact for many years to come.

Thank you, common sense, activist American molecular pathologists, Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court for siding with the people.Dr. Lundbert is editor in chief of Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Babe Ruth’s unique cane, and why he used it

Babe Ruth was arguably the greatest athlete in American history.

Certainly, there have been, and always will be, many great figures in all sports. But none of them – Michael Jordan or LeBron James or Tom Brady – have ever, probably will never, dominate sports AND society in the way Babe Ruth did.

Ruth wasn’t an angel, nor did he claim to be. But he was a center of American life the way no athlete ever was or will be.

He was a remarkably good baseball player. In an era where home runs were rarities, he hit more than the entire rest of Major League Baseball combined. But he wasn’t just a slugger, he was an excellent play maker, fielder, and pitcher. (He was actually one of the best pitchers of his era, something else mostly forgotten today.)

Ruth retired in 1935. He never entirely left the limelight, with fans showing up even to watch him play golf in celebrity tournaments. In 1939 he spoke on July 4 at Lou Gehrig appreciation day as his former teammate was publicly dying of ALS.