User login

Analysis of Pharmacist Interventions Used to Resolve Safety Target of Polypharmacy (STOP) Drug Interactions

Statins are one of the most common medications dispensed in the US and are associated with clinically significant drug interactions.1,2 The most common adverse drug reaction (ADR) of statin drug interactions is muscle-related toxicities.2 Despite technology advances to alert clinicians to drug interactions, updated statin manufacturer labeling, and guideline recommendations, inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of statin drug interactions continues to occur in health care systems.2-10

The medical literature has demonstrated many opportunities for pharmacists to prevent and mitigate drug interactions. At the points of prescribing and dispensing, pharmacists can reduce the number of potential drug interactions for the patient.11-13 Pharmacists also have identified and resolved drug interactions through quality assurance review after dispensing to a patient.7,8

Regardless of the time point of an intervention, the most common method pharmacists used to resolve drug interactions was through recommendations to a prescriber. The recommendations were generated through academic detailing, clinical decision support algorithms, drug conversions, or the pharmacist’s expertise. Regardless of the method the pharmacist used, the prescriber had the final authority to accept or decline the recommendation.7,8,11-13 Although these interventions were effective, pharmacists could further streamline the process by autonomously resolving drug interactions. However, these types of interventions are not well described in the medical literature.

Background

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN), established the Safety Target of Polypharmacy (STOP) report in 2015. At each facility in the network, the report identified patients who were dispensed medications known to have drug interactions. The interactions were chosen by the VISN, and the severity of the interactions was based on coding parameters within the VA computerized order entry system, which uses a severity score based on First Databank data. At the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (Truman VA) in Columbia, Missouri, > 500 drug interactions were initially active on the STOP report. The most common drug interactions were statins with gemfibrozil and statins with niacin.14-18 The Truman VA Pharmacy Service was charged with resolving the interactions for the facility.

The Truman VA employs 3 Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) Clinical Pharmacy Specialists (CPS) practicing within primary care clinics. PACT is the patientcentered medical home model used by the VA. PACT CPS are ambulatory care pharmacists who assist providers in managing diseases using a scope of practice. Having a scope of practice would have allowed the PACT CPS to manage drug interactions with independent prescribing authority. However, due to the high volume of STOP report interactions and limited PACT CPS resources, the Pharmacy Service needed to develop an efficient, patient-centered method to resolve them. The intervention also needed to allow pharmacists, both with and without a scope of practice, to address the interactions.

Methods

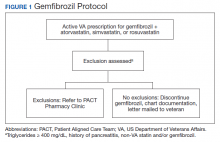

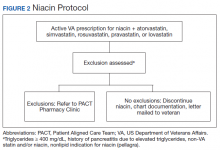

The Truman VA Pharmacy Service developed protocols, approved by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, to manage the specific gemfibrozil-statin and niacinstatin interactions chosen for the VISN 15 STOP report (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols were designed to identify patients who did not have a clear indication for gemfibrozil or niacin, were likely to maintain triglycerides (TGs) < 500 mg/dL without these medications, and would not likely require close monitoring after discontinuation.19 The protocols allowed pharmacists to autonomously discontinue gemfibrozil or niacin if patients did not have a history of pancreatitis, TGs ≥ 400 mg/dL or a nonlipid indication for niacin (eg, pellagra) after establishing care at Truman VA. Additionally, both interacting medications had to be dispensed by the VA. When pharmacists discontinued a medication, it was documented in a note in the patient electronic health record. The prescriber was notified through the note and the patient received a notification letter. Follow-up laboratory monitoring was not required as part of the protocol.

If patients met any of the exclusion criteria for discontinuation, the primary care provider (PCP) was notified to place a consult to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic for individualized interventions and close monitoring. Patients prescribed niacin for nonlipid indications were allowed to continue with their current drug regimen. At each encounter, the PACT CPS assessed for ADRs, made individualized medication changes, and arranged follow-up appointments. Once the interaction was resolved and treatment goals met, the PCP resumed monitoring of the patient’s lipid therapy.

Following all pharmacist interventions, a retrospective quality improvement analysis was conducted. The primary outcome was to evaluate the impact of discontinuing gemfibrozil and niacin by protocol on patients’ laboratory results. The coprimary endpoints were to describe the change in TG levels and the percentage of patients with TGs ≥ 500 mg/dL at least 5 weeks following the pharmacist-directed discontinuation by protocol. Secondary outcomes included the time required to resolve the interactions and a description of the PACT CPS pharmacologic interventions. Additionally, a quality assurance peer review was used to ensure the pharmacists appropriately utilized the protocols.

Data were collected from August 2016 to September 2017 for patients prescribed gemfibrozil and from May 2017 to January 2018 for patients prescribed niacin. The time spent resolving interactions was quantified based on encounter data. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic information and the endpoints associated with each outcome. The project was reviewed by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board, Truman VA privacy and information security officers, and was determined to meet guidelines for quality improvement.

Results

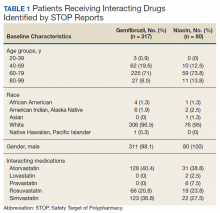

The original STOP report included 397 drug interactions involving statins with gemfibrozil or niacin (Table 1). The majority of patients were white and male aged 60 to 79 years. Gemfibrozil was the most common drug involved in all interactions (79.8%). The most common statins were atorvastatin (40%) and simvastatin (36.5%).

Gemfibrozil-Statin Interactions

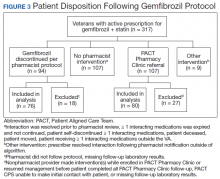

Pharmacists discontinued gemfibrozil by protocol for 94 patients (29.6%), and 107 patients (33.8%) were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic (Figure 3). For the remaining 116 patients (36.6%), the drug interaction was addressed outside of the protocol for the following reasons: the drug interaction was resolved prior to pharmacist review; an interacting prescription was expired and not to be continued; the patient self-discontinued ≥ 1 interacting medications; the patient was deceased; the patient moved; the patient was receiving ≥ 1 interacting medications outside of the VA; or the prescriber resolved the interaction following notification by the pharmacist.

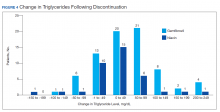

Ultimately, the interaction was resolved for all patients with a gemfibrozil-statin interaction on the STOP report. Following gemfibrozil discontinuation by protocol, 76 patients (80.9%) had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. Sixty-two patients’ (82%) TG levels decreased or increased by < 100 mg/dL (Figure 4), and the TG levels of 1 patient (1.3%) increased above the threshold of 500 mg/dL. The mean (SD) time to the first laboratory result after the pharmacists mailed the notification letter was 6.5 (3.6) months (range, 1-17). The pharmacists spent a mean of 16 minutes per patient resolving each interaction.

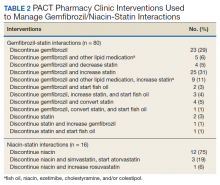

Of the 107 patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic, 80 (74.8%) had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. These patients were followed by the PACT CPS until the drug interaction was resolved and confirmed to have TG levels at goal (< 500 mg/dL). Gemfibrozil doses ranged from 300 mg daily to 600 mg twice daily, with 70% (n = 56) of patients taking 600 mg twice daily. The PACT CPS made 148 interventions (Table 2). Twenty-three (29%) patients required only gemfibrozil discontinuation. The remaining 57 patients (71%) required at least 2 medication interventions. The PACT CPS generated 213 encounters for resolving drug interactions with a median of 2 encounters per patient.

Quality assurance review identified 5 patients (5.3%) who underwent gemfibrozil discontinuation by protocol, despite having criteria that would have recommended against discontinuation. In accordance with the protocol criteria, these patients were later referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. None of these patients experienced a TG increase at or above the threshold of 500 mg/dL after gemfibrozil was initially discontinued but were excluded from the earlier analysis.

Niacin-Statin Interactions

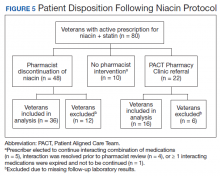

Pharmacists discontinued niacin by protocol for 48 patients (60.0%), and 22 patients (27.5%) were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic (Figure 5). For the remaining 5 patients (6.3%), the interaction was either addressed outside the protocol prior to pharmacist review, or an interacting prescription was expired and not to be continued. Additionally, niacin was continued per prescriber preference in 5 patients (6.3%).

Thirty-six patients (75%) had TG laboratory results available following niacin discontinuation by protocol and were included in the analysis. Most patients’ (n = 33, 91.7%) TG levels decreased or increased by < 100 mg/dL. No patient had a TG level that increased higher than the threshold of 500 mg/dL. The mean (SD) time to the first laboratory result after the pharmacists mailed the notification letter, was 5.3 (2.5) months (range, 1.2-9.8). The pharmacists spent a mean of 15 minutes per patient resolving each interaction. The quality assurance review found no discrepancies in the pharmacists’ application of the protocol.

Of the 22 patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic, 16 (72.7%) patients had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. As with the gemfibrozil interactions, these patients were followed by the PACT Pharmacy Clinic until the drug interaction was resolved and confirmed to have TGs at goal (< 500 mg/dL). Niacin doses ranged from 500 mg daily to 2,000 mg daily, with the majority of patients taking 1,000 mg daily. The PACT CPS made 23 interventions. The PACT CPS generated 46 encounters for resolving drug interactions with a median of 2 encounters per patient.

Discussion

Following gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation by protocol, most patients with available laboratory results experienced either a decrease or modest TG elevation. The proportion of patients experiencing a decrease in TGs was unexpected but potentially multifactorial. Individual causes for the decrease in TGs were beyond the scope of this analysis. The retrospective design limited the ability to identify variables that could have impacted TG levels when gemfibrozil or niacin were started and discontinued. Although the treatment of TG levels is not indicated until it is ≥ 500 mg/dL, due to an increased risk of pancreatitis, both protocols excluded patients with a history of TGs ≥ 400 mg/dL.19 The lower threshold was set to compensate for anticipated increase in TG levels, following gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation, and to minimize the number of patients with TG levels ≥ 500 mg/dL. The actual impact on patients’ TG levels supports the use of this lower threshold in the protocol.

When TG levels increased by 200 to 249 mg/dL after gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation, patients were evaluated for possible underlying causes, which occurred for 4 gemfibrozil and 1 niacin patient. One patient started a β-blocker after gemfibrozil was initiated, and 3 patients were taking gemfibrozil prior to establishing care at the VA. The TG levels of the patient taking niacin correlated with an increased hemoglobin A1c. The TG level for only 1 patient taking gemfibrozil increased above the 500 mg/dL threshold. The patient had several comorbidities known to increase TG levels, but the comorbidities were previously well controlled. No additional medication changes were made at that time, and the TG levels on the next fasting lipid panel decreased to goal. The patient did not experience any negative clinical sequelae from the elevated TG levels.

Thirty-five patients (36%) who were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic required only either gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation. These patients were evaluated to identify whether adjustments to the protocols would have allowed for pharmacist discontinuation without referral to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. Twenty-four of these patients (69%) had repeated TG levels ≥ 400 mg/dL prior to referral to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. Additionally, there was no correlation between the gemfibrozil or niacin doses and the change in TG levels following discontinuation. These data indicate the protocols appropriately identified patients who did not have an indication for gemfibrozil or niacin.

In addition to drug interactions identified on the STOP report, the PACT CPS resolved 12 additional interactions involving simvastatin and gemfibrozil. Additionally, unnecessary lipid medications were deprescribed. The PACT CPS identified 13 patients who experienced myalgias, an ADR attributed to the gemfibrozil- statin interaction. Of those, 9 patients’ ADRs resolved after discontinuing gemfibrozil alone. For the remaining 4 patients, additional interventions to convert the patient to another statin were required to resolve the ADR.

Using pharmacists to address the drug interactions shifted workload from the prescribers and other primary care team members. The mean time spent to resolve both gemfibrozil and niacin interactions by protocol was 15.5 minutes. One hundred fortytwo patients (35.8%) had drug interactions resolved by protocol, saving the PACT CPS’ expertise for patients requiring individualized interventions. Drug interactions were resolved within 4 PACT CPS encounters for 93.8% of the patients taking gemfibrozil and within 3 PACT CPS encounters for 93.8% of the patients taking niacin.

The protocols allowed 12 additional pharmacists who did not have an ambulatory care scope of practice to assist the PACT CPS in mitigating the STOP drug interactions. These pharmacists otherwise would have been limited to making consultative recommendations. Simultaneously, the design allowed for the PACT pharmacists’ expertise to be allocated for patients most likely to require interventions beyond the protocols. This type of intraprofessional referral process is not well described in the medical literature. To the authors’ knowledge, the only studies described referrals from hospital pharmacists to community pharmacists during transitions of care on hospital discharge.20,21

Limitations

The results of this study are derived from a retrospective chart review at a single VA facility. The autonomous nature of PACT CPS interventions may be difficult to replicate in other settings that do not permit pharmacists the same prescriptive authority. This analysis was designed to demonstrate the impact of the pharmacist in resolving major drug interactions. Patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic who also had their lipid medications adjusted by a nonpharmacist provider were excluded. However, this may have minimized the impact of the PACT CPS on the patient care provided. As postintervention laboratory results were not available for all patients, some patients’ TG levels could have increased above the 500 mg/dL threshold but were not identified. The time investment was extensive and likely underestimates the true cost of implementing the interventions.

Because notification letters were used to instruct patients to stop gemfibrozil or niacin, several considerations need to be addressed when interpreting the follow-up laboratory results. First, we cannot confirm whether the patients received the letter or the exact date the letter was received. Additionally, we cannot confirm whether the patients followed the instructions to stop the interacting medications or the date the medications were stopped. It is possible some patients were still taking the interacting medication when the first laboratory was drawn. Should a patient have continued the interacting medication, most would have run out and been unable to obtain a refill within 90 days of receiving the letter, as this is the maximum amount dispensed at one time. The mean time to the first laboratory result for both gemfibrozil and niacin was 6.5 and 5.3 months, respectively. Approximately 85% of patients completed the first laboratory test at least 3 months after the letter was mailed.

The protocols were designed to assess whether gemfibrozil or niacin was indicated and did not assess whether the statin was indicated. Therefore, discontinuing the statin also could have resolved the interaction appropriately. However, due to characteristics of the patient population and recommendations in current lipid guidelines, it was more likely the statin would be indicated.22,23 The protocols also assumed that patients eligible for gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation would not need additional changes to their lipid medications. The medication changes made by the PACT CPS may have gone beyond those minimally necessary to resolve the drug interaction and maintain TG goals. Patients who had gemfibrozil or niacin discontinued by protocol also may have benefited from additional optimization of their lipid medications.

Conclusions

This quality improvement analysis supports further evaluation of the complementary use of protocols and PACT CPS prescriptive authority to resolve statin drug interactions. The gemfibrozil and niacin protocols appropriately identified patients who were less likely to experience an adverse change in TG laboratory results. Patients more likely to require additional medication interventions were appropriately referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinics for individualized care. These data support expanded roles for pharmacists, across various settings, to mitigate select drug interactions at the Truman VA.

Acknowledgments

This quality improvement project is the result of work supported with resources and use of the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital in Columbia, Missouri.

1. The top 200 drugs of 2020 Provided by the ClinCalc DrugStats Database. http://clincalc.com/DrugStats /Top200Drugs.aspx. Updated February 11, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2020.

2. Wiggins BS, Saseen JJ, Page RL 2nd, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Hypertension; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Recommendations for management of clinically significant drug-drug interactions with statins and select agents used in patients with cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(21):e468‐e495. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000456

3. Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Bejian S, Burenheide K, Kane-Gill SL. A critical evaluation of clinical decision support for the detection of drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(6):871‐882. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.583916

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: new restrictions, contraindications, and dose limitations for Zocor (simvastatin) to reduce the risk of muscle injury. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety /ucm256581.htm. Updated December 15, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2020.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. https://www.fda.gov /Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. Updated January 19, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020.

6. US Food and Drug Administration Federal Register. AbbVie Inc. et al; withdrawal of approval of indications related to the coadministration with statins in applications for niacin extended-release tablets and fenofibric acid delayed-release capsules. https://www.federalregister .gov/documents/2016/04/18/2016-08887/abbvie-inc -et-al-withdrawal-of-approval-of-indications-related -to-the-coadministration-with-statins. Published April 18, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020.

7. Lamprecht DG Jr, Todd BA, Denham AM, Ruppe LK, Stadler SL. Clinical pharmacist patient-safety initiative to reduce against-label prescribing of statins with cyclosporine. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(2):140‐145. doi:10.1177/1060028016675352

8. Roblek T, Deticek A, Leskovar B, et al. Clinical-pharmacist intervention reduces clinically relevant drugdrug interactions in patients with heart failure: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:647‐652. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.206

9. Tuchscherer RM, Nair K, Ghushchyan V, Saseen JJ. Simvastatin prescribing patterns before and after FDA dosing restrictions: a retrospective analysis of a large healthcare claims database. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2015;15(1):27‐34. doi:10.1007/s40256-014-0096-x

10. Alford JC, Saseen JJ, Allen RR, Nair KV. Persistent use of against-label statin-fibrate combinations from 2003-2009 despite United States Food and Drug Administration dose restrictions. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(7):623‐630. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.2011.01090.x

11. Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit [published correction appears in JAMA 2000 Mar 8;283(10):1293]. JAMA. 1999;282(3):267‐270. doi:10.1001/jama.282.3.267

12. Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M, Nafziger DA. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014‐2018. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.17.2014

13. Humphries TL, Carroll N, Chester EA, Magid D, Rocho B. Evaluation of an electronic critical drug interaction program coupled with active pharmacist intervention. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(12):1979‐1985. doi:10.1345/aph.1K349

14. Zocor [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2018.

15. Lipitor [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2017.

16. Crestor [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca; 2018.

17. Mevacor [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2012.

18. Wolters Kluwer Health, Lexi-Drugs, Lexicomp. Pravastatin. www.online.lexi.com. [Source not verified.]

19. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Lipidology, Thrombosis, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726

20. Ferguson J, Seston L, Ashcroft DM. Refer-to-pharmacy: a qualitative study exploring the implementation of an electronic transfer of care initiative to improve medicines optimisation following hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):424. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3262-z

21. Ensing HT, Koster ES, Dubero DJ, van Dooren AA, Bouvy ML. Collaboration between hospital and community pharmacists to address drug-related problems: the HomeCoMe-program. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(3):267‐278. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.05.001

22. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction guideline summary. https://www.healthquality.va.gov /guidelines/CD/lipids/LipidSumOptSinglePg31Aug15.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 14, 2020.

23. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25) (suppl 2):S46-48] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132(25):e396]. Circulation. 2014;129(25)(suppl 2): S1‐S45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a

Statins are one of the most common medications dispensed in the US and are associated with clinically significant drug interactions.1,2 The most common adverse drug reaction (ADR) of statin drug interactions is muscle-related toxicities.2 Despite technology advances to alert clinicians to drug interactions, updated statin manufacturer labeling, and guideline recommendations, inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of statin drug interactions continues to occur in health care systems.2-10

The medical literature has demonstrated many opportunities for pharmacists to prevent and mitigate drug interactions. At the points of prescribing and dispensing, pharmacists can reduce the number of potential drug interactions for the patient.11-13 Pharmacists also have identified and resolved drug interactions through quality assurance review after dispensing to a patient.7,8

Regardless of the time point of an intervention, the most common method pharmacists used to resolve drug interactions was through recommendations to a prescriber. The recommendations were generated through academic detailing, clinical decision support algorithms, drug conversions, or the pharmacist’s expertise. Regardless of the method the pharmacist used, the prescriber had the final authority to accept or decline the recommendation.7,8,11-13 Although these interventions were effective, pharmacists could further streamline the process by autonomously resolving drug interactions. However, these types of interventions are not well described in the medical literature.

Background

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN), established the Safety Target of Polypharmacy (STOP) report in 2015. At each facility in the network, the report identified patients who were dispensed medications known to have drug interactions. The interactions were chosen by the VISN, and the severity of the interactions was based on coding parameters within the VA computerized order entry system, which uses a severity score based on First Databank data. At the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (Truman VA) in Columbia, Missouri, > 500 drug interactions were initially active on the STOP report. The most common drug interactions were statins with gemfibrozil and statins with niacin.14-18 The Truman VA Pharmacy Service was charged with resolving the interactions for the facility.

The Truman VA employs 3 Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) Clinical Pharmacy Specialists (CPS) practicing within primary care clinics. PACT is the patientcentered medical home model used by the VA. PACT CPS are ambulatory care pharmacists who assist providers in managing diseases using a scope of practice. Having a scope of practice would have allowed the PACT CPS to manage drug interactions with independent prescribing authority. However, due to the high volume of STOP report interactions and limited PACT CPS resources, the Pharmacy Service needed to develop an efficient, patient-centered method to resolve them. The intervention also needed to allow pharmacists, both with and without a scope of practice, to address the interactions.

Methods

The Truman VA Pharmacy Service developed protocols, approved by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, to manage the specific gemfibrozil-statin and niacinstatin interactions chosen for the VISN 15 STOP report (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols were designed to identify patients who did not have a clear indication for gemfibrozil or niacin, were likely to maintain triglycerides (TGs) < 500 mg/dL without these medications, and would not likely require close monitoring after discontinuation.19 The protocols allowed pharmacists to autonomously discontinue gemfibrozil or niacin if patients did not have a history of pancreatitis, TGs ≥ 400 mg/dL or a nonlipid indication for niacin (eg, pellagra) after establishing care at Truman VA. Additionally, both interacting medications had to be dispensed by the VA. When pharmacists discontinued a medication, it was documented in a note in the patient electronic health record. The prescriber was notified through the note and the patient received a notification letter. Follow-up laboratory monitoring was not required as part of the protocol.

If patients met any of the exclusion criteria for discontinuation, the primary care provider (PCP) was notified to place a consult to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic for individualized interventions and close monitoring. Patients prescribed niacin for nonlipid indications were allowed to continue with their current drug regimen. At each encounter, the PACT CPS assessed for ADRs, made individualized medication changes, and arranged follow-up appointments. Once the interaction was resolved and treatment goals met, the PCP resumed monitoring of the patient’s lipid therapy.

Following all pharmacist interventions, a retrospective quality improvement analysis was conducted. The primary outcome was to evaluate the impact of discontinuing gemfibrozil and niacin by protocol on patients’ laboratory results. The coprimary endpoints were to describe the change in TG levels and the percentage of patients with TGs ≥ 500 mg/dL at least 5 weeks following the pharmacist-directed discontinuation by protocol. Secondary outcomes included the time required to resolve the interactions and a description of the PACT CPS pharmacologic interventions. Additionally, a quality assurance peer review was used to ensure the pharmacists appropriately utilized the protocols.

Data were collected from August 2016 to September 2017 for patients prescribed gemfibrozil and from May 2017 to January 2018 for patients prescribed niacin. The time spent resolving interactions was quantified based on encounter data. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic information and the endpoints associated with each outcome. The project was reviewed by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board, Truman VA privacy and information security officers, and was determined to meet guidelines for quality improvement.

Results

The original STOP report included 397 drug interactions involving statins with gemfibrozil or niacin (Table 1). The majority of patients were white and male aged 60 to 79 years. Gemfibrozil was the most common drug involved in all interactions (79.8%). The most common statins were atorvastatin (40%) and simvastatin (36.5%).

Gemfibrozil-Statin Interactions

Pharmacists discontinued gemfibrozil by protocol for 94 patients (29.6%), and 107 patients (33.8%) were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic (Figure 3). For the remaining 116 patients (36.6%), the drug interaction was addressed outside of the protocol for the following reasons: the drug interaction was resolved prior to pharmacist review; an interacting prescription was expired and not to be continued; the patient self-discontinued ≥ 1 interacting medications; the patient was deceased; the patient moved; the patient was receiving ≥ 1 interacting medications outside of the VA; or the prescriber resolved the interaction following notification by the pharmacist.

Ultimately, the interaction was resolved for all patients with a gemfibrozil-statin interaction on the STOP report. Following gemfibrozil discontinuation by protocol, 76 patients (80.9%) had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. Sixty-two patients’ (82%) TG levels decreased or increased by < 100 mg/dL (Figure 4), and the TG levels of 1 patient (1.3%) increased above the threshold of 500 mg/dL. The mean (SD) time to the first laboratory result after the pharmacists mailed the notification letter was 6.5 (3.6) months (range, 1-17). The pharmacists spent a mean of 16 minutes per patient resolving each interaction.

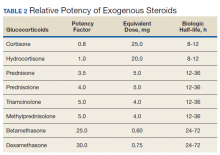

Of the 107 patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic, 80 (74.8%) had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. These patients were followed by the PACT CPS until the drug interaction was resolved and confirmed to have TG levels at goal (< 500 mg/dL). Gemfibrozil doses ranged from 300 mg daily to 600 mg twice daily, with 70% (n = 56) of patients taking 600 mg twice daily. The PACT CPS made 148 interventions (Table 2). Twenty-three (29%) patients required only gemfibrozil discontinuation. The remaining 57 patients (71%) required at least 2 medication interventions. The PACT CPS generated 213 encounters for resolving drug interactions with a median of 2 encounters per patient.

Quality assurance review identified 5 patients (5.3%) who underwent gemfibrozil discontinuation by protocol, despite having criteria that would have recommended against discontinuation. In accordance with the protocol criteria, these patients were later referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. None of these patients experienced a TG increase at or above the threshold of 500 mg/dL after gemfibrozil was initially discontinued but were excluded from the earlier analysis.

Niacin-Statin Interactions

Pharmacists discontinued niacin by protocol for 48 patients (60.0%), and 22 patients (27.5%) were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic (Figure 5). For the remaining 5 patients (6.3%), the interaction was either addressed outside the protocol prior to pharmacist review, or an interacting prescription was expired and not to be continued. Additionally, niacin was continued per prescriber preference in 5 patients (6.3%).

Thirty-six patients (75%) had TG laboratory results available following niacin discontinuation by protocol and were included in the analysis. Most patients’ (n = 33, 91.7%) TG levels decreased or increased by < 100 mg/dL. No patient had a TG level that increased higher than the threshold of 500 mg/dL. The mean (SD) time to the first laboratory result after the pharmacists mailed the notification letter, was 5.3 (2.5) months (range, 1.2-9.8). The pharmacists spent a mean of 15 minutes per patient resolving each interaction. The quality assurance review found no discrepancies in the pharmacists’ application of the protocol.

Of the 22 patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic, 16 (72.7%) patients had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. As with the gemfibrozil interactions, these patients were followed by the PACT Pharmacy Clinic until the drug interaction was resolved and confirmed to have TGs at goal (< 500 mg/dL). Niacin doses ranged from 500 mg daily to 2,000 mg daily, with the majority of patients taking 1,000 mg daily. The PACT CPS made 23 interventions. The PACT CPS generated 46 encounters for resolving drug interactions with a median of 2 encounters per patient.

Discussion

Following gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation by protocol, most patients with available laboratory results experienced either a decrease or modest TG elevation. The proportion of patients experiencing a decrease in TGs was unexpected but potentially multifactorial. Individual causes for the decrease in TGs were beyond the scope of this analysis. The retrospective design limited the ability to identify variables that could have impacted TG levels when gemfibrozil or niacin were started and discontinued. Although the treatment of TG levels is not indicated until it is ≥ 500 mg/dL, due to an increased risk of pancreatitis, both protocols excluded patients with a history of TGs ≥ 400 mg/dL.19 The lower threshold was set to compensate for anticipated increase in TG levels, following gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation, and to minimize the number of patients with TG levels ≥ 500 mg/dL. The actual impact on patients’ TG levels supports the use of this lower threshold in the protocol.

When TG levels increased by 200 to 249 mg/dL after gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation, patients were evaluated for possible underlying causes, which occurred for 4 gemfibrozil and 1 niacin patient. One patient started a β-blocker after gemfibrozil was initiated, and 3 patients were taking gemfibrozil prior to establishing care at the VA. The TG levels of the patient taking niacin correlated with an increased hemoglobin A1c. The TG level for only 1 patient taking gemfibrozil increased above the 500 mg/dL threshold. The patient had several comorbidities known to increase TG levels, but the comorbidities were previously well controlled. No additional medication changes were made at that time, and the TG levels on the next fasting lipid panel decreased to goal. The patient did not experience any negative clinical sequelae from the elevated TG levels.

Thirty-five patients (36%) who were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic required only either gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation. These patients were evaluated to identify whether adjustments to the protocols would have allowed for pharmacist discontinuation without referral to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. Twenty-four of these patients (69%) had repeated TG levels ≥ 400 mg/dL prior to referral to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. Additionally, there was no correlation between the gemfibrozil or niacin doses and the change in TG levels following discontinuation. These data indicate the protocols appropriately identified patients who did not have an indication for gemfibrozil or niacin.

In addition to drug interactions identified on the STOP report, the PACT CPS resolved 12 additional interactions involving simvastatin and gemfibrozil. Additionally, unnecessary lipid medications were deprescribed. The PACT CPS identified 13 patients who experienced myalgias, an ADR attributed to the gemfibrozil- statin interaction. Of those, 9 patients’ ADRs resolved after discontinuing gemfibrozil alone. For the remaining 4 patients, additional interventions to convert the patient to another statin were required to resolve the ADR.

Using pharmacists to address the drug interactions shifted workload from the prescribers and other primary care team members. The mean time spent to resolve both gemfibrozil and niacin interactions by protocol was 15.5 minutes. One hundred fortytwo patients (35.8%) had drug interactions resolved by protocol, saving the PACT CPS’ expertise for patients requiring individualized interventions. Drug interactions were resolved within 4 PACT CPS encounters for 93.8% of the patients taking gemfibrozil and within 3 PACT CPS encounters for 93.8% of the patients taking niacin.

The protocols allowed 12 additional pharmacists who did not have an ambulatory care scope of practice to assist the PACT CPS in mitigating the STOP drug interactions. These pharmacists otherwise would have been limited to making consultative recommendations. Simultaneously, the design allowed for the PACT pharmacists’ expertise to be allocated for patients most likely to require interventions beyond the protocols. This type of intraprofessional referral process is not well described in the medical literature. To the authors’ knowledge, the only studies described referrals from hospital pharmacists to community pharmacists during transitions of care on hospital discharge.20,21

Limitations

The results of this study are derived from a retrospective chart review at a single VA facility. The autonomous nature of PACT CPS interventions may be difficult to replicate in other settings that do not permit pharmacists the same prescriptive authority. This analysis was designed to demonstrate the impact of the pharmacist in resolving major drug interactions. Patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic who also had their lipid medications adjusted by a nonpharmacist provider were excluded. However, this may have minimized the impact of the PACT CPS on the patient care provided. As postintervention laboratory results were not available for all patients, some patients’ TG levels could have increased above the 500 mg/dL threshold but were not identified. The time investment was extensive and likely underestimates the true cost of implementing the interventions.

Because notification letters were used to instruct patients to stop gemfibrozil or niacin, several considerations need to be addressed when interpreting the follow-up laboratory results. First, we cannot confirm whether the patients received the letter or the exact date the letter was received. Additionally, we cannot confirm whether the patients followed the instructions to stop the interacting medications or the date the medications were stopped. It is possible some patients were still taking the interacting medication when the first laboratory was drawn. Should a patient have continued the interacting medication, most would have run out and been unable to obtain a refill within 90 days of receiving the letter, as this is the maximum amount dispensed at one time. The mean time to the first laboratory result for both gemfibrozil and niacin was 6.5 and 5.3 months, respectively. Approximately 85% of patients completed the first laboratory test at least 3 months after the letter was mailed.

The protocols were designed to assess whether gemfibrozil or niacin was indicated and did not assess whether the statin was indicated. Therefore, discontinuing the statin also could have resolved the interaction appropriately. However, due to characteristics of the patient population and recommendations in current lipid guidelines, it was more likely the statin would be indicated.22,23 The protocols also assumed that patients eligible for gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation would not need additional changes to their lipid medications. The medication changes made by the PACT CPS may have gone beyond those minimally necessary to resolve the drug interaction and maintain TG goals. Patients who had gemfibrozil or niacin discontinued by protocol also may have benefited from additional optimization of their lipid medications.

Conclusions

This quality improvement analysis supports further evaluation of the complementary use of protocols and PACT CPS prescriptive authority to resolve statin drug interactions. The gemfibrozil and niacin protocols appropriately identified patients who were less likely to experience an adverse change in TG laboratory results. Patients more likely to require additional medication interventions were appropriately referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinics for individualized care. These data support expanded roles for pharmacists, across various settings, to mitigate select drug interactions at the Truman VA.

Acknowledgments

This quality improvement project is the result of work supported with resources and use of the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital in Columbia, Missouri.

Statins are one of the most common medications dispensed in the US and are associated with clinically significant drug interactions.1,2 The most common adverse drug reaction (ADR) of statin drug interactions is muscle-related toxicities.2 Despite technology advances to alert clinicians to drug interactions, updated statin manufacturer labeling, and guideline recommendations, inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of statin drug interactions continues to occur in health care systems.2-10

The medical literature has demonstrated many opportunities for pharmacists to prevent and mitigate drug interactions. At the points of prescribing and dispensing, pharmacists can reduce the number of potential drug interactions for the patient.11-13 Pharmacists also have identified and resolved drug interactions through quality assurance review after dispensing to a patient.7,8

Regardless of the time point of an intervention, the most common method pharmacists used to resolve drug interactions was through recommendations to a prescriber. The recommendations were generated through academic detailing, clinical decision support algorithms, drug conversions, or the pharmacist’s expertise. Regardless of the method the pharmacist used, the prescriber had the final authority to accept or decline the recommendation.7,8,11-13 Although these interventions were effective, pharmacists could further streamline the process by autonomously resolving drug interactions. However, these types of interventions are not well described in the medical literature.

Background

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN), established the Safety Target of Polypharmacy (STOP) report in 2015. At each facility in the network, the report identified patients who were dispensed medications known to have drug interactions. The interactions were chosen by the VISN, and the severity of the interactions was based on coding parameters within the VA computerized order entry system, which uses a severity score based on First Databank data. At the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (Truman VA) in Columbia, Missouri, > 500 drug interactions were initially active on the STOP report. The most common drug interactions were statins with gemfibrozil and statins with niacin.14-18 The Truman VA Pharmacy Service was charged with resolving the interactions for the facility.

The Truman VA employs 3 Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) Clinical Pharmacy Specialists (CPS) practicing within primary care clinics. PACT is the patientcentered medical home model used by the VA. PACT CPS are ambulatory care pharmacists who assist providers in managing diseases using a scope of practice. Having a scope of practice would have allowed the PACT CPS to manage drug interactions with independent prescribing authority. However, due to the high volume of STOP report interactions and limited PACT CPS resources, the Pharmacy Service needed to develop an efficient, patient-centered method to resolve them. The intervention also needed to allow pharmacists, both with and without a scope of practice, to address the interactions.

Methods

The Truman VA Pharmacy Service developed protocols, approved by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, to manage the specific gemfibrozil-statin and niacinstatin interactions chosen for the VISN 15 STOP report (Figures 1 and 2). The protocols were designed to identify patients who did not have a clear indication for gemfibrozil or niacin, were likely to maintain triglycerides (TGs) < 500 mg/dL without these medications, and would not likely require close monitoring after discontinuation.19 The protocols allowed pharmacists to autonomously discontinue gemfibrozil or niacin if patients did not have a history of pancreatitis, TGs ≥ 400 mg/dL or a nonlipid indication for niacin (eg, pellagra) after establishing care at Truman VA. Additionally, both interacting medications had to be dispensed by the VA. When pharmacists discontinued a medication, it was documented in a note in the patient electronic health record. The prescriber was notified through the note and the patient received a notification letter. Follow-up laboratory monitoring was not required as part of the protocol.

If patients met any of the exclusion criteria for discontinuation, the primary care provider (PCP) was notified to place a consult to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic for individualized interventions and close monitoring. Patients prescribed niacin for nonlipid indications were allowed to continue with their current drug regimen. At each encounter, the PACT CPS assessed for ADRs, made individualized medication changes, and arranged follow-up appointments. Once the interaction was resolved and treatment goals met, the PCP resumed monitoring of the patient’s lipid therapy.

Following all pharmacist interventions, a retrospective quality improvement analysis was conducted. The primary outcome was to evaluate the impact of discontinuing gemfibrozil and niacin by protocol on patients’ laboratory results. The coprimary endpoints were to describe the change in TG levels and the percentage of patients with TGs ≥ 500 mg/dL at least 5 weeks following the pharmacist-directed discontinuation by protocol. Secondary outcomes included the time required to resolve the interactions and a description of the PACT CPS pharmacologic interventions. Additionally, a quality assurance peer review was used to ensure the pharmacists appropriately utilized the protocols.

Data were collected from August 2016 to September 2017 for patients prescribed gemfibrozil and from May 2017 to January 2018 for patients prescribed niacin. The time spent resolving interactions was quantified based on encounter data. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic information and the endpoints associated with each outcome. The project was reviewed by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board, Truman VA privacy and information security officers, and was determined to meet guidelines for quality improvement.

Results

The original STOP report included 397 drug interactions involving statins with gemfibrozil or niacin (Table 1). The majority of patients were white and male aged 60 to 79 years. Gemfibrozil was the most common drug involved in all interactions (79.8%). The most common statins were atorvastatin (40%) and simvastatin (36.5%).

Gemfibrozil-Statin Interactions

Pharmacists discontinued gemfibrozil by protocol for 94 patients (29.6%), and 107 patients (33.8%) were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic (Figure 3). For the remaining 116 patients (36.6%), the drug interaction was addressed outside of the protocol for the following reasons: the drug interaction was resolved prior to pharmacist review; an interacting prescription was expired and not to be continued; the patient self-discontinued ≥ 1 interacting medications; the patient was deceased; the patient moved; the patient was receiving ≥ 1 interacting medications outside of the VA; or the prescriber resolved the interaction following notification by the pharmacist.

Ultimately, the interaction was resolved for all patients with a gemfibrozil-statin interaction on the STOP report. Following gemfibrozil discontinuation by protocol, 76 patients (80.9%) had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. Sixty-two patients’ (82%) TG levels decreased or increased by < 100 mg/dL (Figure 4), and the TG levels of 1 patient (1.3%) increased above the threshold of 500 mg/dL. The mean (SD) time to the first laboratory result after the pharmacists mailed the notification letter was 6.5 (3.6) months (range, 1-17). The pharmacists spent a mean of 16 minutes per patient resolving each interaction.

Of the 107 patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic, 80 (74.8%) had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. These patients were followed by the PACT CPS until the drug interaction was resolved and confirmed to have TG levels at goal (< 500 mg/dL). Gemfibrozil doses ranged from 300 mg daily to 600 mg twice daily, with 70% (n = 56) of patients taking 600 mg twice daily. The PACT CPS made 148 interventions (Table 2). Twenty-three (29%) patients required only gemfibrozil discontinuation. The remaining 57 patients (71%) required at least 2 medication interventions. The PACT CPS generated 213 encounters for resolving drug interactions with a median of 2 encounters per patient.

Quality assurance review identified 5 patients (5.3%) who underwent gemfibrozil discontinuation by protocol, despite having criteria that would have recommended against discontinuation. In accordance with the protocol criteria, these patients were later referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. None of these patients experienced a TG increase at or above the threshold of 500 mg/dL after gemfibrozil was initially discontinued but were excluded from the earlier analysis.

Niacin-Statin Interactions

Pharmacists discontinued niacin by protocol for 48 patients (60.0%), and 22 patients (27.5%) were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic (Figure 5). For the remaining 5 patients (6.3%), the interaction was either addressed outside the protocol prior to pharmacist review, or an interacting prescription was expired and not to be continued. Additionally, niacin was continued per prescriber preference in 5 patients (6.3%).

Thirty-six patients (75%) had TG laboratory results available following niacin discontinuation by protocol and were included in the analysis. Most patients’ (n = 33, 91.7%) TG levels decreased or increased by < 100 mg/dL. No patient had a TG level that increased higher than the threshold of 500 mg/dL. The mean (SD) time to the first laboratory result after the pharmacists mailed the notification letter, was 5.3 (2.5) months (range, 1.2-9.8). The pharmacists spent a mean of 15 minutes per patient resolving each interaction. The quality assurance review found no discrepancies in the pharmacists’ application of the protocol.

Of the 22 patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic, 16 (72.7%) patients had TG laboratory results available and were included in the analysis. As with the gemfibrozil interactions, these patients were followed by the PACT Pharmacy Clinic until the drug interaction was resolved and confirmed to have TGs at goal (< 500 mg/dL). Niacin doses ranged from 500 mg daily to 2,000 mg daily, with the majority of patients taking 1,000 mg daily. The PACT CPS made 23 interventions. The PACT CPS generated 46 encounters for resolving drug interactions with a median of 2 encounters per patient.

Discussion

Following gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation by protocol, most patients with available laboratory results experienced either a decrease or modest TG elevation. The proportion of patients experiencing a decrease in TGs was unexpected but potentially multifactorial. Individual causes for the decrease in TGs were beyond the scope of this analysis. The retrospective design limited the ability to identify variables that could have impacted TG levels when gemfibrozil or niacin were started and discontinued. Although the treatment of TG levels is not indicated until it is ≥ 500 mg/dL, due to an increased risk of pancreatitis, both protocols excluded patients with a history of TGs ≥ 400 mg/dL.19 The lower threshold was set to compensate for anticipated increase in TG levels, following gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation, and to minimize the number of patients with TG levels ≥ 500 mg/dL. The actual impact on patients’ TG levels supports the use of this lower threshold in the protocol.

When TG levels increased by 200 to 249 mg/dL after gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation, patients were evaluated for possible underlying causes, which occurred for 4 gemfibrozil and 1 niacin patient. One patient started a β-blocker after gemfibrozil was initiated, and 3 patients were taking gemfibrozil prior to establishing care at the VA. The TG levels of the patient taking niacin correlated with an increased hemoglobin A1c. The TG level for only 1 patient taking gemfibrozil increased above the 500 mg/dL threshold. The patient had several comorbidities known to increase TG levels, but the comorbidities were previously well controlled. No additional medication changes were made at that time, and the TG levels on the next fasting lipid panel decreased to goal. The patient did not experience any negative clinical sequelae from the elevated TG levels.

Thirty-five patients (36%) who were referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic required only either gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation. These patients were evaluated to identify whether adjustments to the protocols would have allowed for pharmacist discontinuation without referral to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. Twenty-four of these patients (69%) had repeated TG levels ≥ 400 mg/dL prior to referral to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic. Additionally, there was no correlation between the gemfibrozil or niacin doses and the change in TG levels following discontinuation. These data indicate the protocols appropriately identified patients who did not have an indication for gemfibrozil or niacin.

In addition to drug interactions identified on the STOP report, the PACT CPS resolved 12 additional interactions involving simvastatin and gemfibrozil. Additionally, unnecessary lipid medications were deprescribed. The PACT CPS identified 13 patients who experienced myalgias, an ADR attributed to the gemfibrozil- statin interaction. Of those, 9 patients’ ADRs resolved after discontinuing gemfibrozil alone. For the remaining 4 patients, additional interventions to convert the patient to another statin were required to resolve the ADR.

Using pharmacists to address the drug interactions shifted workload from the prescribers and other primary care team members. The mean time spent to resolve both gemfibrozil and niacin interactions by protocol was 15.5 minutes. One hundred fortytwo patients (35.8%) had drug interactions resolved by protocol, saving the PACT CPS’ expertise for patients requiring individualized interventions. Drug interactions were resolved within 4 PACT CPS encounters for 93.8% of the patients taking gemfibrozil and within 3 PACT CPS encounters for 93.8% of the patients taking niacin.

The protocols allowed 12 additional pharmacists who did not have an ambulatory care scope of practice to assist the PACT CPS in mitigating the STOP drug interactions. These pharmacists otherwise would have been limited to making consultative recommendations. Simultaneously, the design allowed for the PACT pharmacists’ expertise to be allocated for patients most likely to require interventions beyond the protocols. This type of intraprofessional referral process is not well described in the medical literature. To the authors’ knowledge, the only studies described referrals from hospital pharmacists to community pharmacists during transitions of care on hospital discharge.20,21

Limitations

The results of this study are derived from a retrospective chart review at a single VA facility. The autonomous nature of PACT CPS interventions may be difficult to replicate in other settings that do not permit pharmacists the same prescriptive authority. This analysis was designed to demonstrate the impact of the pharmacist in resolving major drug interactions. Patients referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinic who also had their lipid medications adjusted by a nonpharmacist provider were excluded. However, this may have minimized the impact of the PACT CPS on the patient care provided. As postintervention laboratory results were not available for all patients, some patients’ TG levels could have increased above the 500 mg/dL threshold but were not identified. The time investment was extensive and likely underestimates the true cost of implementing the interventions.

Because notification letters were used to instruct patients to stop gemfibrozil or niacin, several considerations need to be addressed when interpreting the follow-up laboratory results. First, we cannot confirm whether the patients received the letter or the exact date the letter was received. Additionally, we cannot confirm whether the patients followed the instructions to stop the interacting medications or the date the medications were stopped. It is possible some patients were still taking the interacting medication when the first laboratory was drawn. Should a patient have continued the interacting medication, most would have run out and been unable to obtain a refill within 90 days of receiving the letter, as this is the maximum amount dispensed at one time. The mean time to the first laboratory result for both gemfibrozil and niacin was 6.5 and 5.3 months, respectively. Approximately 85% of patients completed the first laboratory test at least 3 months after the letter was mailed.

The protocols were designed to assess whether gemfibrozil or niacin was indicated and did not assess whether the statin was indicated. Therefore, discontinuing the statin also could have resolved the interaction appropriately. However, due to characteristics of the patient population and recommendations in current lipid guidelines, it was more likely the statin would be indicated.22,23 The protocols also assumed that patients eligible for gemfibrozil or niacin discontinuation would not need additional changes to their lipid medications. The medication changes made by the PACT CPS may have gone beyond those minimally necessary to resolve the drug interaction and maintain TG goals. Patients who had gemfibrozil or niacin discontinued by protocol also may have benefited from additional optimization of their lipid medications.

Conclusions

This quality improvement analysis supports further evaluation of the complementary use of protocols and PACT CPS prescriptive authority to resolve statin drug interactions. The gemfibrozil and niacin protocols appropriately identified patients who were less likely to experience an adverse change in TG laboratory results. Patients more likely to require additional medication interventions were appropriately referred to the PACT Pharmacy Clinics for individualized care. These data support expanded roles for pharmacists, across various settings, to mitigate select drug interactions at the Truman VA.

Acknowledgments

This quality improvement project is the result of work supported with resources and use of the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital in Columbia, Missouri.

1. The top 200 drugs of 2020 Provided by the ClinCalc DrugStats Database. http://clincalc.com/DrugStats /Top200Drugs.aspx. Updated February 11, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2020.

2. Wiggins BS, Saseen JJ, Page RL 2nd, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Hypertension; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Recommendations for management of clinically significant drug-drug interactions with statins and select agents used in patients with cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(21):e468‐e495. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000456

3. Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Bejian S, Burenheide K, Kane-Gill SL. A critical evaluation of clinical decision support for the detection of drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(6):871‐882. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.583916

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: new restrictions, contraindications, and dose limitations for Zocor (simvastatin) to reduce the risk of muscle injury. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety /ucm256581.htm. Updated December 15, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2020.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. https://www.fda.gov /Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. Updated January 19, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020.

6. US Food and Drug Administration Federal Register. AbbVie Inc. et al; withdrawal of approval of indications related to the coadministration with statins in applications for niacin extended-release tablets and fenofibric acid delayed-release capsules. https://www.federalregister .gov/documents/2016/04/18/2016-08887/abbvie-inc -et-al-withdrawal-of-approval-of-indications-related -to-the-coadministration-with-statins. Published April 18, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020.

7. Lamprecht DG Jr, Todd BA, Denham AM, Ruppe LK, Stadler SL. Clinical pharmacist patient-safety initiative to reduce against-label prescribing of statins with cyclosporine. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(2):140‐145. doi:10.1177/1060028016675352

8. Roblek T, Deticek A, Leskovar B, et al. Clinical-pharmacist intervention reduces clinically relevant drugdrug interactions in patients with heart failure: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:647‐652. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.206

9. Tuchscherer RM, Nair K, Ghushchyan V, Saseen JJ. Simvastatin prescribing patterns before and after FDA dosing restrictions: a retrospective analysis of a large healthcare claims database. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2015;15(1):27‐34. doi:10.1007/s40256-014-0096-x

10. Alford JC, Saseen JJ, Allen RR, Nair KV. Persistent use of against-label statin-fibrate combinations from 2003-2009 despite United States Food and Drug Administration dose restrictions. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(7):623‐630. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.2011.01090.x

11. Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit [published correction appears in JAMA 2000 Mar 8;283(10):1293]. JAMA. 1999;282(3):267‐270. doi:10.1001/jama.282.3.267

12. Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M, Nafziger DA. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014‐2018. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.17.2014

13. Humphries TL, Carroll N, Chester EA, Magid D, Rocho B. Evaluation of an electronic critical drug interaction program coupled with active pharmacist intervention. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(12):1979‐1985. doi:10.1345/aph.1K349

14. Zocor [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2018.

15. Lipitor [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2017.

16. Crestor [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca; 2018.

17. Mevacor [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2012.

18. Wolters Kluwer Health, Lexi-Drugs, Lexicomp. Pravastatin. www.online.lexi.com. [Source not verified.]

19. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Lipidology, Thrombosis, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726

20. Ferguson J, Seston L, Ashcroft DM. Refer-to-pharmacy: a qualitative study exploring the implementation of an electronic transfer of care initiative to improve medicines optimisation following hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):424. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3262-z

21. Ensing HT, Koster ES, Dubero DJ, van Dooren AA, Bouvy ML. Collaboration between hospital and community pharmacists to address drug-related problems: the HomeCoMe-program. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(3):267‐278. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.05.001

22. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction guideline summary. https://www.healthquality.va.gov /guidelines/CD/lipids/LipidSumOptSinglePg31Aug15.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 14, 2020.

23. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25) (suppl 2):S46-48] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132(25):e396]. Circulation. 2014;129(25)(suppl 2): S1‐S45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a

1. The top 200 drugs of 2020 Provided by the ClinCalc DrugStats Database. http://clincalc.com/DrugStats /Top200Drugs.aspx. Updated February 11, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2020.

2. Wiggins BS, Saseen JJ, Page RL 2nd, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Hypertension; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Recommendations for management of clinically significant drug-drug interactions with statins and select agents used in patients with cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(21):e468‐e495. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000456

3. Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Bejian S, Burenheide K, Kane-Gill SL. A critical evaluation of clinical decision support for the detection of drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(6):871‐882. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.583916

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: new restrictions, contraindications, and dose limitations for Zocor (simvastatin) to reduce the risk of muscle injury. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety /ucm256581.htm. Updated December 15, 2017. Accessed May 12, 2020.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. https://www.fda.gov /Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. Updated January 19, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020.

6. US Food and Drug Administration Federal Register. AbbVie Inc. et al; withdrawal of approval of indications related to the coadministration with statins in applications for niacin extended-release tablets and fenofibric acid delayed-release capsules. https://www.federalregister .gov/documents/2016/04/18/2016-08887/abbvie-inc -et-al-withdrawal-of-approval-of-indications-related -to-the-coadministration-with-statins. Published April 18, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020.

7. Lamprecht DG Jr, Todd BA, Denham AM, Ruppe LK, Stadler SL. Clinical pharmacist patient-safety initiative to reduce against-label prescribing of statins with cyclosporine. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(2):140‐145. doi:10.1177/1060028016675352

8. Roblek T, Deticek A, Leskovar B, et al. Clinical-pharmacist intervention reduces clinically relevant drugdrug interactions in patients with heart failure: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:647‐652. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.206

9. Tuchscherer RM, Nair K, Ghushchyan V, Saseen JJ. Simvastatin prescribing patterns before and after FDA dosing restrictions: a retrospective analysis of a large healthcare claims database. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2015;15(1):27‐34. doi:10.1007/s40256-014-0096-x

10. Alford JC, Saseen JJ, Allen RR, Nair KV. Persistent use of against-label statin-fibrate combinations from 2003-2009 despite United States Food and Drug Administration dose restrictions. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(7):623‐630. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.2011.01090.x

11. Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit [published correction appears in JAMA 2000 Mar 8;283(10):1293]. JAMA. 1999;282(3):267‐270. doi:10.1001/jama.282.3.267

12. Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M, Nafziger DA. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014‐2018. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.17.2014

13. Humphries TL, Carroll N, Chester EA, Magid D, Rocho B. Evaluation of an electronic critical drug interaction program coupled with active pharmacist intervention. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(12):1979‐1985. doi:10.1345/aph.1K349

14. Zocor [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2018.

15. Lipitor [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2017.

16. Crestor [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca; 2018.

17. Mevacor [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2012.

18. Wolters Kluwer Health, Lexi-Drugs, Lexicomp. Pravastatin. www.online.lexi.com. [Source not verified.]

19. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Lipidology, Thrombosis, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726

20. Ferguson J, Seston L, Ashcroft DM. Refer-to-pharmacy: a qualitative study exploring the implementation of an electronic transfer of care initiative to improve medicines optimisation following hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):424. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3262-z

21. Ensing HT, Koster ES, Dubero DJ, van Dooren AA, Bouvy ML. Collaboration between hospital and community pharmacists to address drug-related problems: the HomeCoMe-program. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(3):267‐278. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.05.001

22. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction guideline summary. https://www.healthquality.va.gov /guidelines/CD/lipids/LipidSumOptSinglePg31Aug15.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 14, 2020.

23. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25) (suppl 2):S46-48] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132(25):e396]. Circulation. 2014;129(25)(suppl 2): S1‐S45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a

Biologics may carry melanoma risk for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

The in a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

The studies included in the analysis, however, had limitations, including a lack of those comparing biologic and conventional systemic therapy in psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to Shamarke Esse, MRes, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences at the University of Manchester (England) and colleagues. “We advocate for more large, well-designed studies of this issue to be performed to help improve certainty” regarding this association, they wrote.

Previous studies that have found an increased risk of melanoma in patients on biologics for psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and IBD have “typically used the general population as the comparator,” they noted. There is a large amount of evidence that has established short-term efficacy and safety of biologics, compared with conventional systemic treatments, but concerns about longer-term cancer risk associated with biologics remains a concern. Moreover, they added, “melanoma is a highly immunogenic skin cancer and therefore of concern to patients treated with TNFIs [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] because melanoma risk increases with suppression of the immune system and TNF-alpha plays an important role in the immune surveillance of tumors.12,13

In their review, the researchers identified seven cohort studies from MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases published between January 1995 and February 2019 that evaluated melanoma risk in about 34,000 patients receiving biologics and 135,370 patients who had never been treated with biologics, and were receiving conventional systemic therapy for psoriasis, RA, or IBD. Of these, four studies were in patients with RA, two studies were in patients with IBD, and a single study was in patients with psoriasis. Six studies examined patients taking TNF inhibitors, but only one of six studies had information on specific TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) in patients with RA. One study evaluated abatacept and rituximab in RA patients.

The researchers analyzed the pooled relative risk across all studies. Compared with patients who received conventional systemic therapy, there was a nonsignificant association with risk of melanoma in patients with psoriasis (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-4.09), RA (pooled relative risk, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83-1.74), and IBD (pRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.60-2.40).

Among RA patients who received TNF inhibitors only, there was a slightly elevated nonsignificant risk of melanoma (pRR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43). Patients receiving rituximab had a pRR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.38-1.39), and patients taking abatacept had a pRR of 1.43 (95% CI, 0.66-3.09), compared with RA patients receiving conventional systemic therapy. When excluding two major studies in the RA subgroup of patients in a sensitivity analysis, pooled risk estimates varied from 0.91 (95% CI, 0.69-1.18) to 1.95 (95% CI, 1.16- 3.30). There were no significant between-study heterogeneity or publication bias among the IBD and RA studies.

Mr. Esse and colleagues acknowledged the small number of IBD and psoriasis studies in the meta-analysis, which could affect pooled risk estimates. “Any future update of our study through the inclusion of newly published studies may produce significantly different pooled risk estimates than those reported in our meta-analysis,” they said. In addition, the use of health insurance databases, lack of risk factors for melanoma, and inconsistent information about treatment duration for patients receiving conventional systemic therapy were also limitations.

“Prospective cohort studies using an active comparator, new-user study design providing detailed information on treatment history, concomitant treatments, biologic and conventional systemic treatment duration, recreational and treatment-related UV exposure, skin color, and date of melanoma diagnosis are required to help improve certainty. These studies would also need to account for key risk factors and the latency period of melanoma,” the researchers said.

Mr. Esse disclosed being funded by a PhD studentship from the Psoriasis Association. One author disclosed receiving personal fees from Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis outside the study; another disclosed receiving grants and personal fees from those and several other pharmaceutical companies during the study, and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside of the submitted work; the fourth author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Esse S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 20;e201300.

The in a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

The studies included in the analysis, however, had limitations, including a lack of those comparing biologic and conventional systemic therapy in psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to Shamarke Esse, MRes, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences at the University of Manchester (England) and colleagues. “We advocate for more large, well-designed studies of this issue to be performed to help improve certainty” regarding this association, they wrote.