User login

Irregularly Hyperpigmented Plaque on the Right Heel

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen Disease

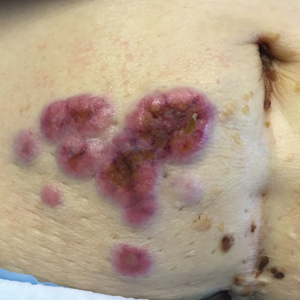

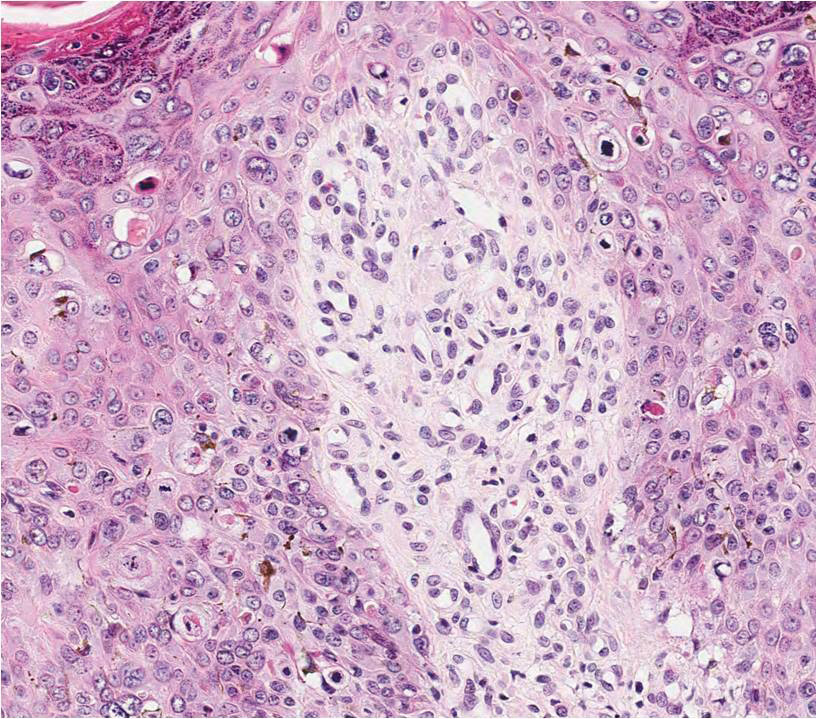

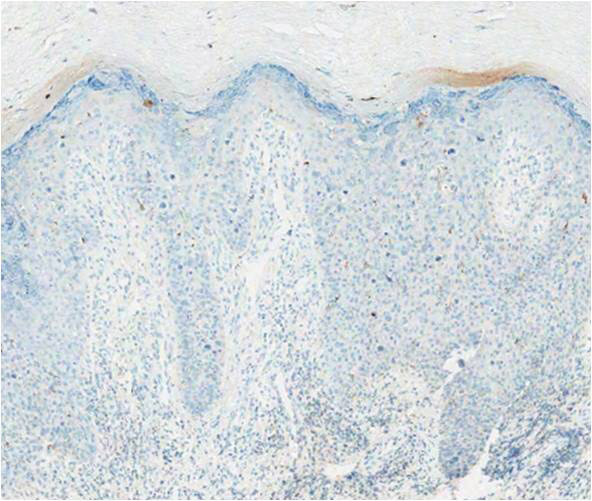

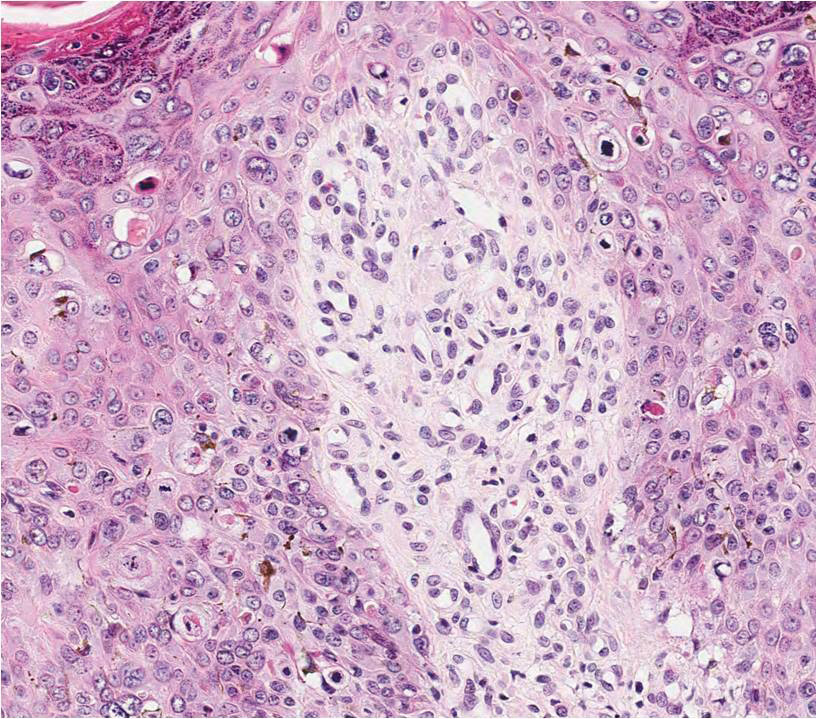

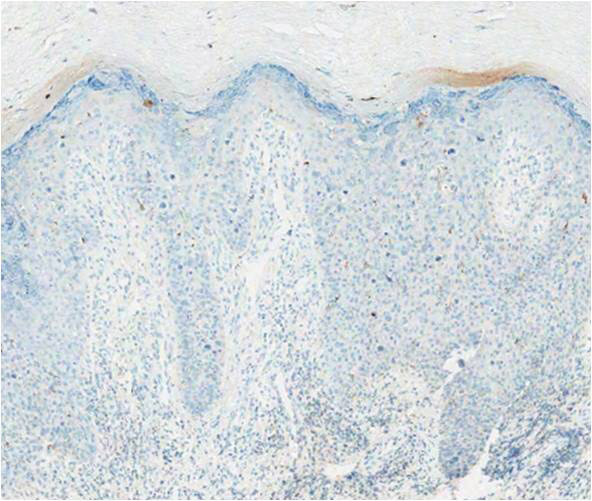

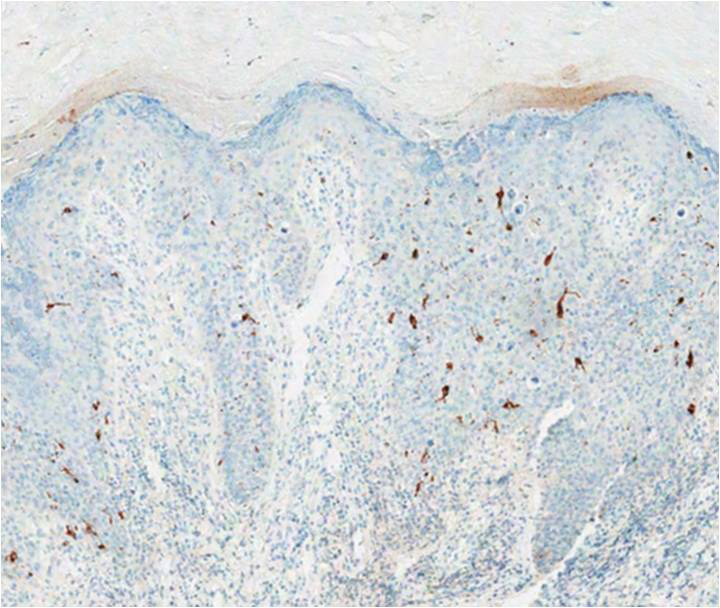

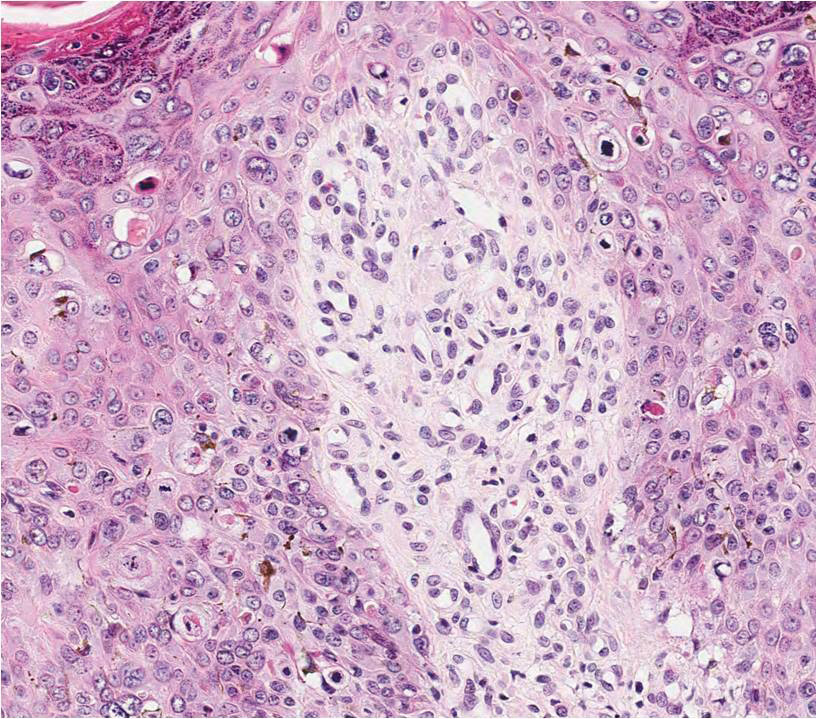

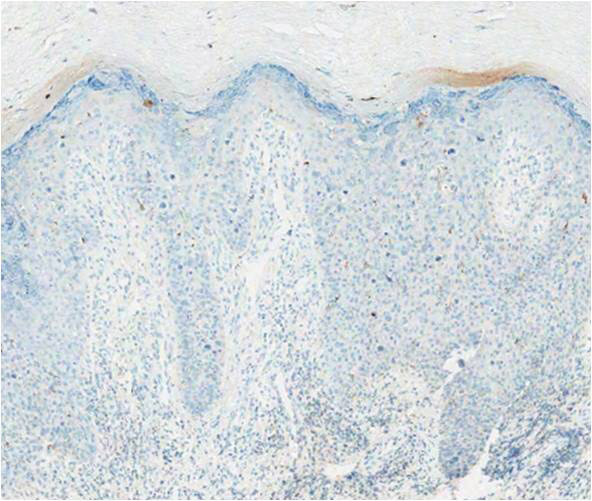

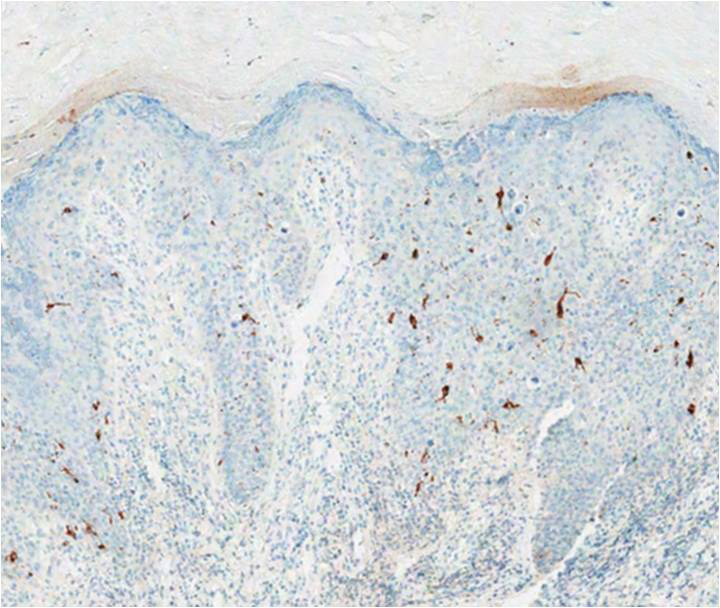

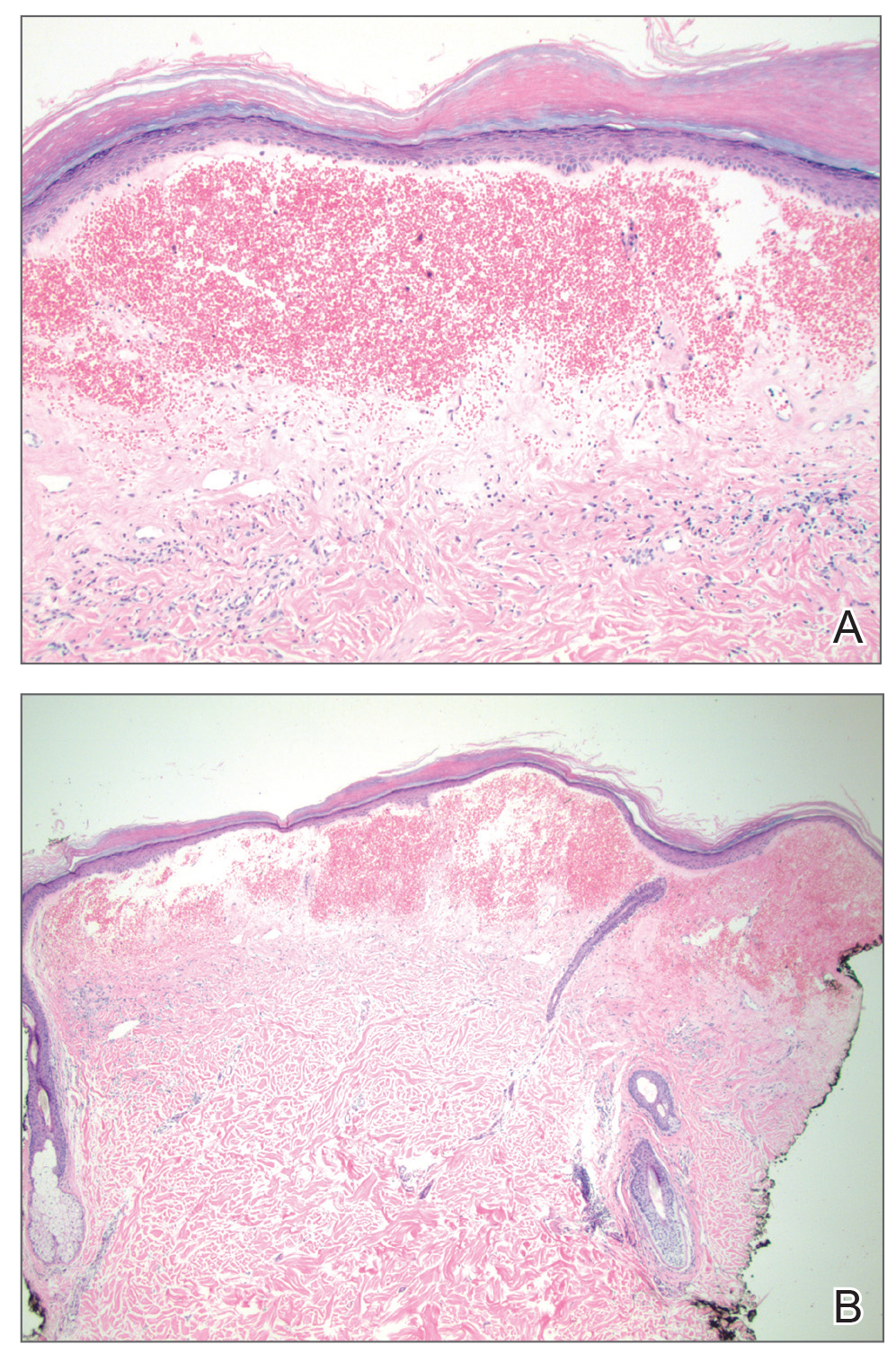

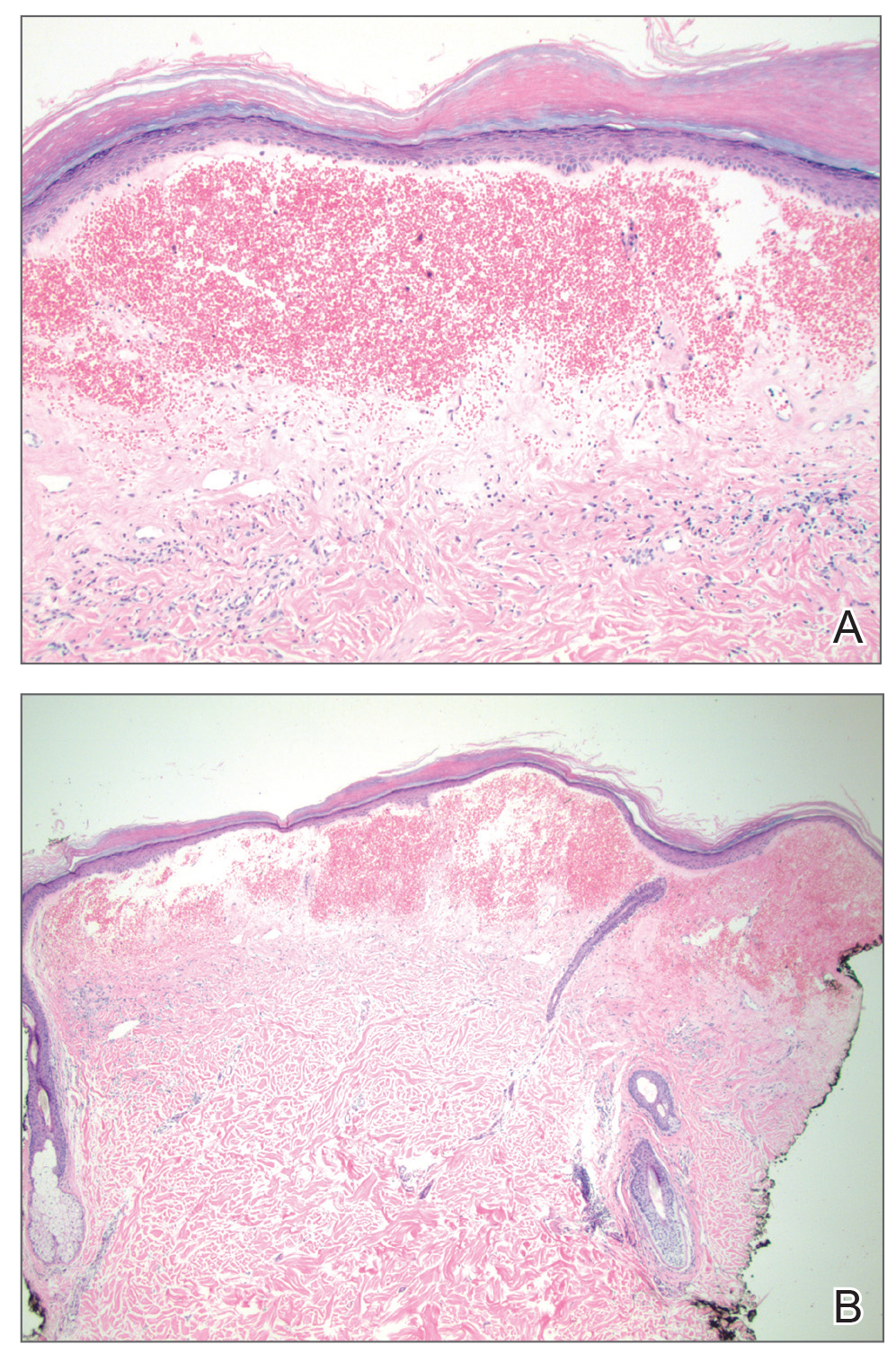

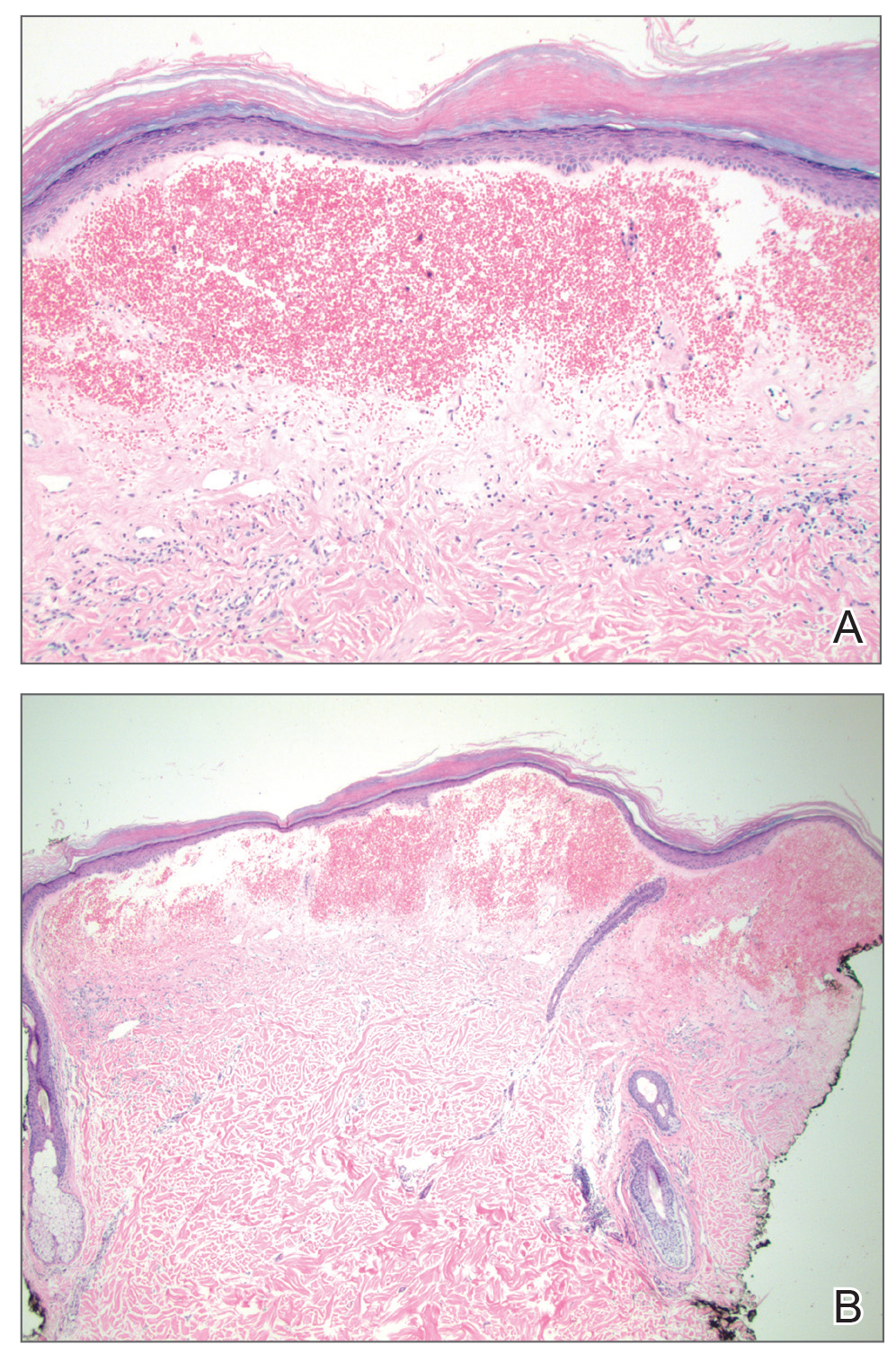

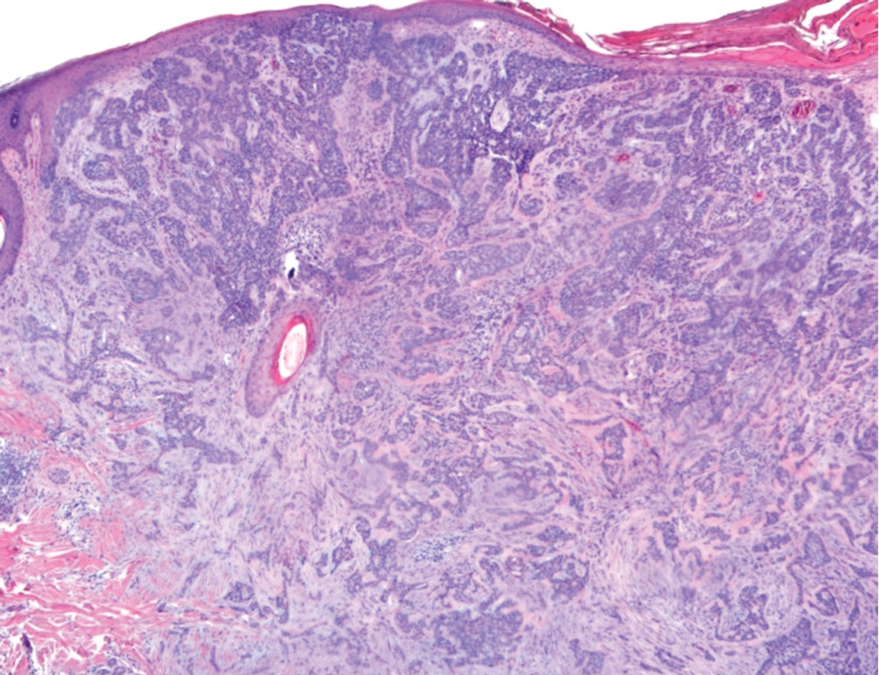

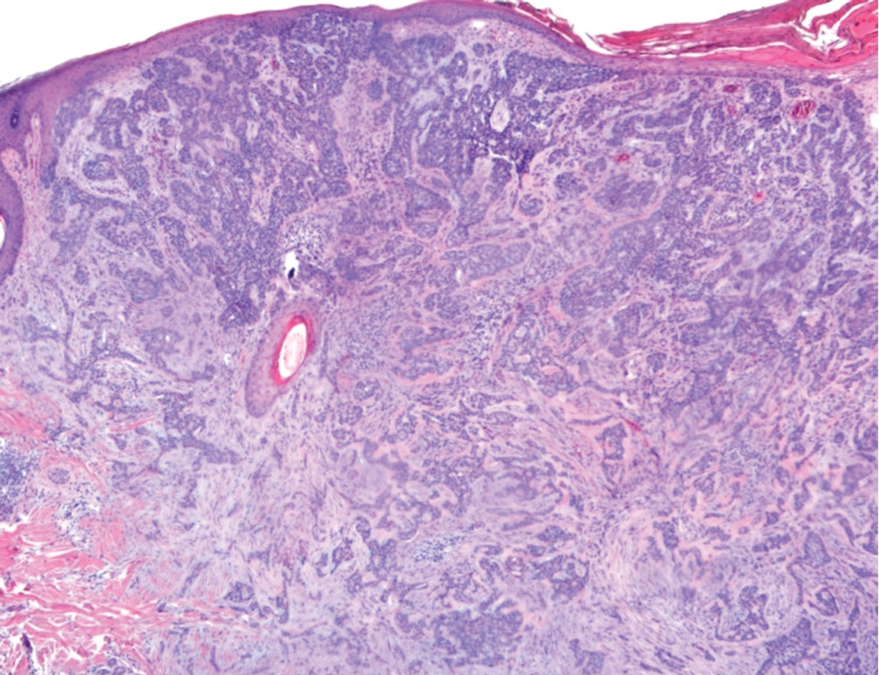

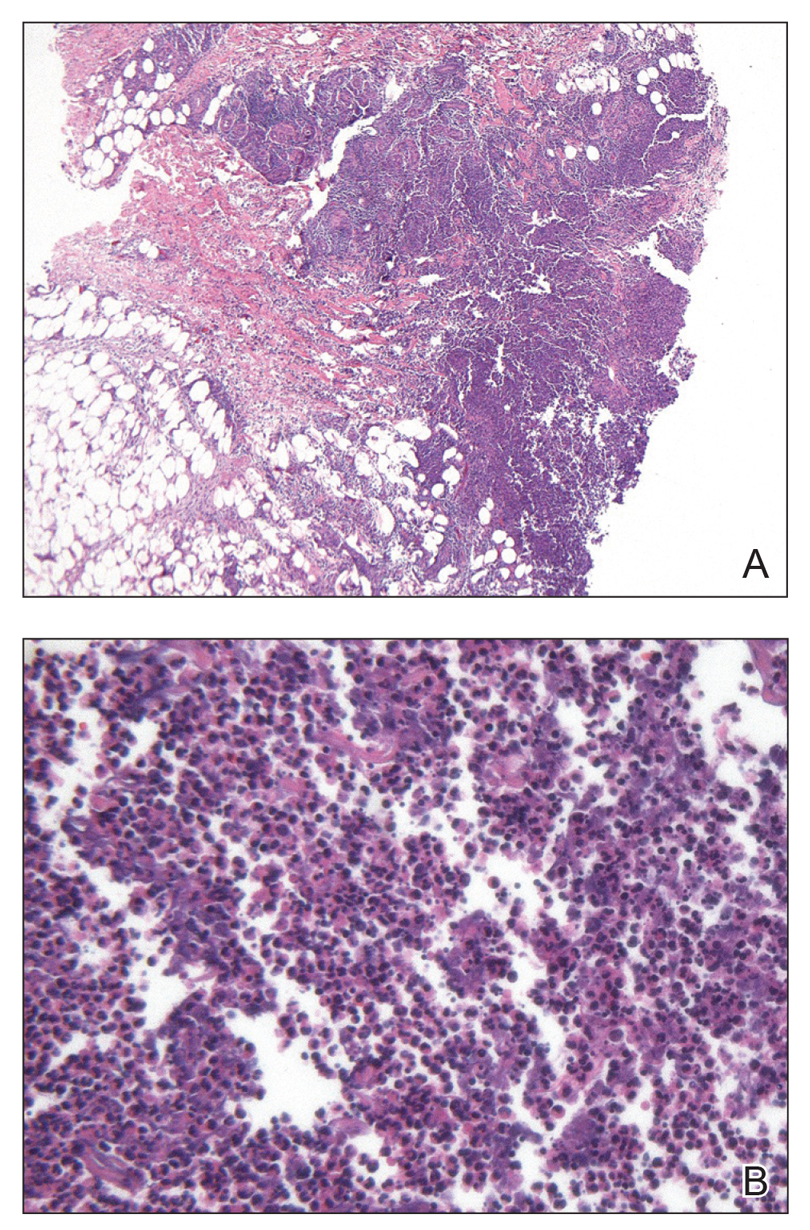

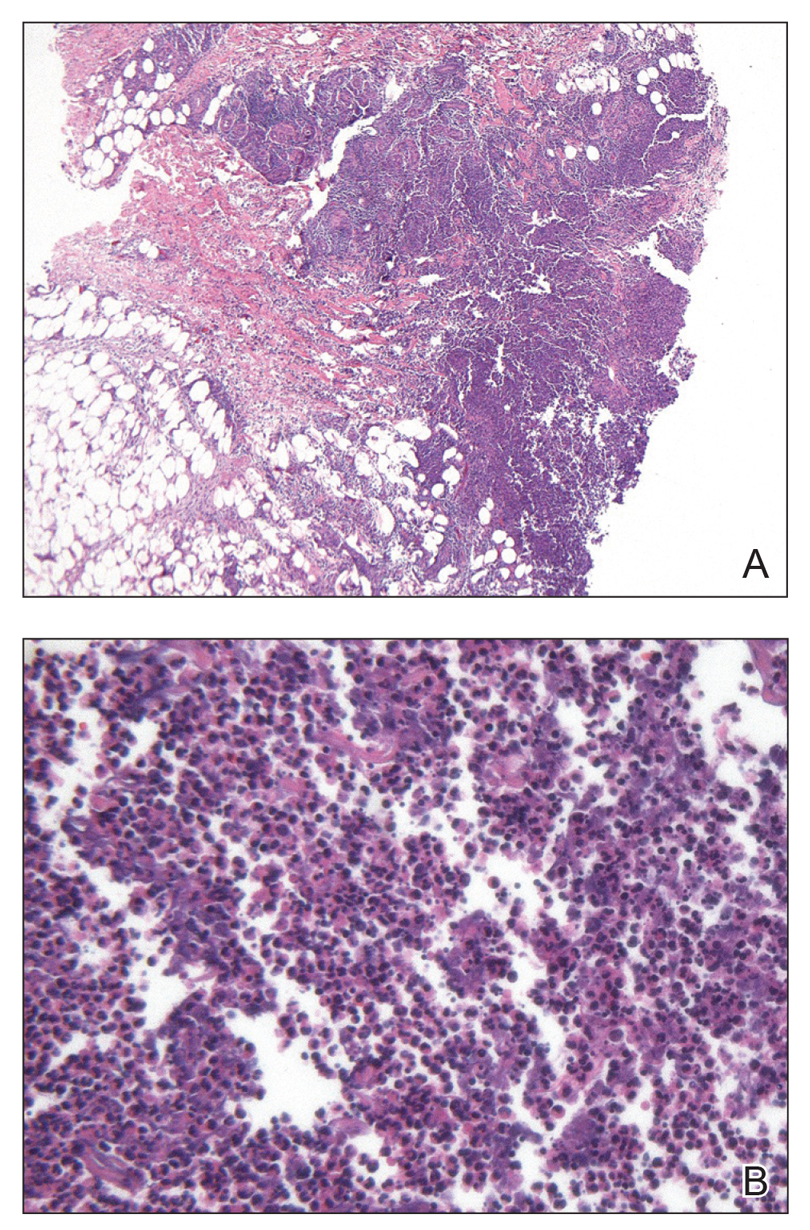

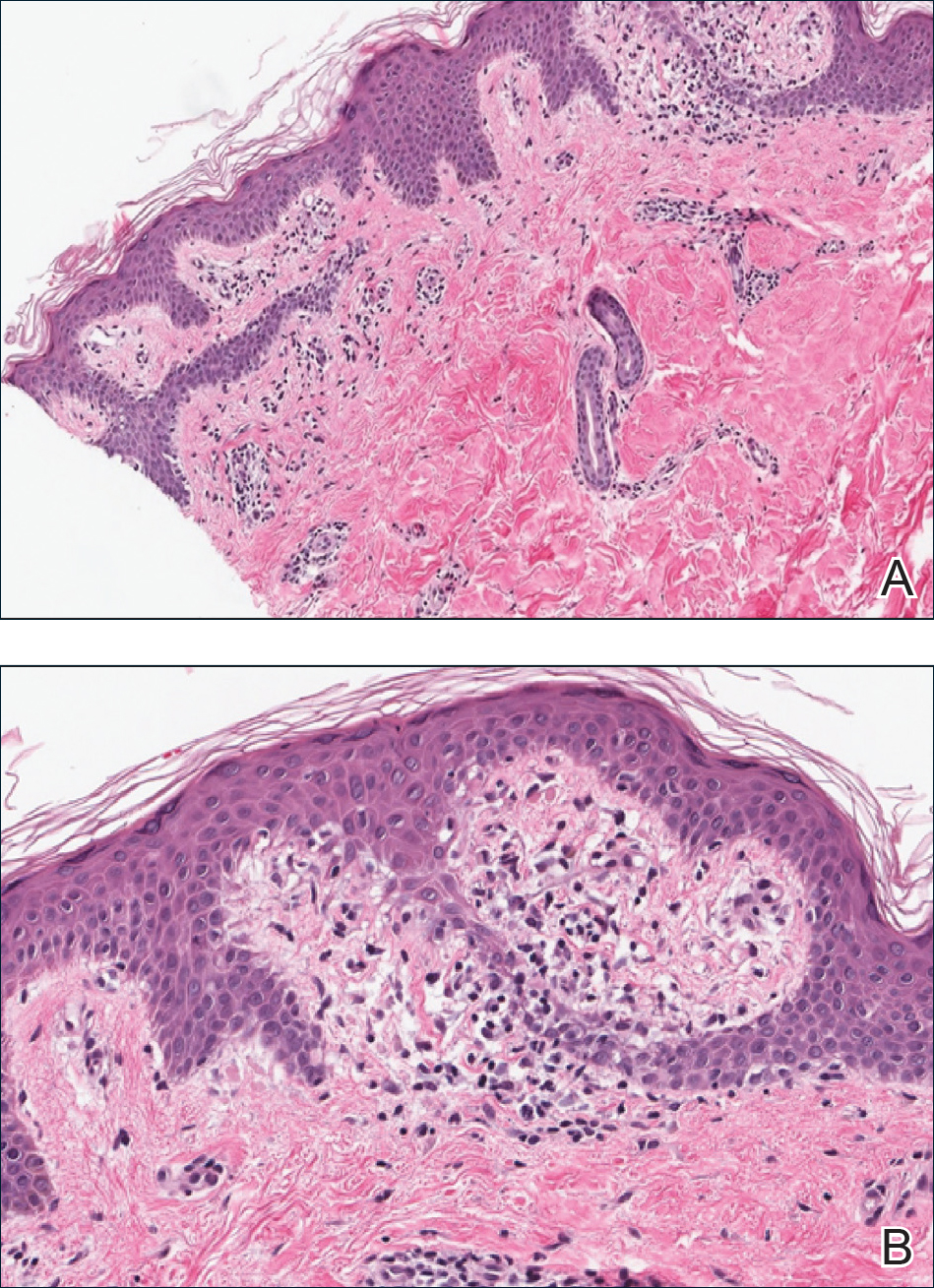

A biopsy of the lesion was performed for suspected acral malignant melanoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and keratinocytes in complete disorder with atypical mitoses and pleomorphism affecting the full layer of the epidermis (Figure 1). The basement membrane was intact. Melanin pigmentation was increased in the lower epidermis and the upper dermis, and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate was present in the dermis. Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 2) and melanoma

antigen (Figure 3) recognized by T cells (melan-A) both revealed negative results. Histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of pigmented Bowen disease (BD).

Pigmented BD is a rare variant that accounts for 1.7% (N=420) to 5.5% (N=951) of all cases of BD.1,2 It is reported to affect men more than women and to be more prevalent in individuals with higher Fitzpatrick skin types.3 Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation, chemicals (eg, arsenic), or human papillomavirus, as well as immunosuppression, are known to be related to pigmented BD.2,4 Clinically, pigmented BD commonly involves nonexposed areas such as the anogenital area, trunk, and extremities, unlike typical BD that involves sun-exposed areas.5 In addition, it most frequently presents as a well-delineated, irregularly pigmented, asymptomatic

plaque and not as a scaly erythematous plaque. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis may be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, pigmented extramammary Paget disease, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, and melanocytic nevi.

Histopathologically, a varying amount of melanin deposit is noted on hematoxylin and eosin staining, along with features of BD, including disarrayed atypical keratinocytes involving the full epidermis but not the basement membrane, with atypical individual cell keratinization.3,5,6 Pigmented extramammary Paget disease can mimic pigmented BD clinically and pathologically, but Paget cells stain positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucicarmine, whereas cells in pigmented BD stain negative.7 Moreover, negative staining for human melanoma black, melan-A, and S-100 helps differentiate malignant melanoma from pigmented BD.8

The prognosis of pigmented BD is similar to classic BD and is independent of the presence of melanin pigment.6 Therefore, the treatment options do not differ from those for typical BD and include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, curettage, electrosurgery, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

In our case, the patient and her family did not want surgical removal; therefore, 1 course of fractional laser-assisted PDT and 2 courses of ablative laser-assisted PDT were performed. Unfortunately, the lesion persisted, possibly because it was too large and pigmented. Two months later, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% was applied (4 courses) after using an ablative laser over 3 consecutive days with a 1-month interval between courses. The lesion resolved without any adverse events.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online January 15, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:765-769.

- Hernandez C, Ivkovic A, Fowler A. Growing plaque on foot. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:603-605.

- Hwang SW, Kim JW, Park SW, et al. Two cases of pigmented Bowen’s disease. Ann Dermatol 2002;14:127-129.

- Wilmer EM, Lee KC, Higgins W 2nd, et al. Hyperpigmented palmar plaque: an unexpected diagnosis of Bowen disease. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18573.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Gonçalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-884.

- Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:995-1000.

- Öztürk Durmaz E, Dog˘ an Ekici I, Ozian F, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease of the genitalia masquerading as malignant melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:130-133.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen Disease

A biopsy of the lesion was performed for suspected acral malignant melanoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and keratinocytes in complete disorder with atypical mitoses and pleomorphism affecting the full layer of the epidermis (Figure 1). The basement membrane was intact. Melanin pigmentation was increased in the lower epidermis and the upper dermis, and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate was present in the dermis. Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 2) and melanoma

antigen (Figure 3) recognized by T cells (melan-A) both revealed negative results. Histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of pigmented Bowen disease (BD).

Pigmented BD is a rare variant that accounts for 1.7% (N=420) to 5.5% (N=951) of all cases of BD.1,2 It is reported to affect men more than women and to be more prevalent in individuals with higher Fitzpatrick skin types.3 Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation, chemicals (eg, arsenic), or human papillomavirus, as well as immunosuppression, are known to be related to pigmented BD.2,4 Clinically, pigmented BD commonly involves nonexposed areas such as the anogenital area, trunk, and extremities, unlike typical BD that involves sun-exposed areas.5 In addition, it most frequently presents as a well-delineated, irregularly pigmented, asymptomatic

plaque and not as a scaly erythematous plaque. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis may be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, pigmented extramammary Paget disease, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, and melanocytic nevi.

Histopathologically, a varying amount of melanin deposit is noted on hematoxylin and eosin staining, along with features of BD, including disarrayed atypical keratinocytes involving the full epidermis but not the basement membrane, with atypical individual cell keratinization.3,5,6 Pigmented extramammary Paget disease can mimic pigmented BD clinically and pathologically, but Paget cells stain positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucicarmine, whereas cells in pigmented BD stain negative.7 Moreover, negative staining for human melanoma black, melan-A, and S-100 helps differentiate malignant melanoma from pigmented BD.8

The prognosis of pigmented BD is similar to classic BD and is independent of the presence of melanin pigment.6 Therefore, the treatment options do not differ from those for typical BD and include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, curettage, electrosurgery, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

In our case, the patient and her family did not want surgical removal; therefore, 1 course of fractional laser-assisted PDT and 2 courses of ablative laser-assisted PDT were performed. Unfortunately, the lesion persisted, possibly because it was too large and pigmented. Two months later, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% was applied (4 courses) after using an ablative laser over 3 consecutive days with a 1-month interval between courses. The lesion resolved without any adverse events.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen Disease

A biopsy of the lesion was performed for suspected acral malignant melanoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and keratinocytes in complete disorder with atypical mitoses and pleomorphism affecting the full layer of the epidermis (Figure 1). The basement membrane was intact. Melanin pigmentation was increased in the lower epidermis and the upper dermis, and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate was present in the dermis. Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 2) and melanoma

antigen (Figure 3) recognized by T cells (melan-A) both revealed negative results. Histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of pigmented Bowen disease (BD).

Pigmented BD is a rare variant that accounts for 1.7% (N=420) to 5.5% (N=951) of all cases of BD.1,2 It is reported to affect men more than women and to be more prevalent in individuals with higher Fitzpatrick skin types.3 Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation, chemicals (eg, arsenic), or human papillomavirus, as well as immunosuppression, are known to be related to pigmented BD.2,4 Clinically, pigmented BD commonly involves nonexposed areas such as the anogenital area, trunk, and extremities, unlike typical BD that involves sun-exposed areas.5 In addition, it most frequently presents as a well-delineated, irregularly pigmented, asymptomatic

plaque and not as a scaly erythematous plaque. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis may be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, pigmented extramammary Paget disease, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, and melanocytic nevi.

Histopathologically, a varying amount of melanin deposit is noted on hematoxylin and eosin staining, along with features of BD, including disarrayed atypical keratinocytes involving the full epidermis but not the basement membrane, with atypical individual cell keratinization.3,5,6 Pigmented extramammary Paget disease can mimic pigmented BD clinically and pathologically, but Paget cells stain positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucicarmine, whereas cells in pigmented BD stain negative.7 Moreover, negative staining for human melanoma black, melan-A, and S-100 helps differentiate malignant melanoma from pigmented BD.8

The prognosis of pigmented BD is similar to classic BD and is independent of the presence of melanin pigment.6 Therefore, the treatment options do not differ from those for typical BD and include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, curettage, electrosurgery, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

In our case, the patient and her family did not want surgical removal; therefore, 1 course of fractional laser-assisted PDT and 2 courses of ablative laser-assisted PDT were performed. Unfortunately, the lesion persisted, possibly because it was too large and pigmented. Two months later, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% was applied (4 courses) after using an ablative laser over 3 consecutive days with a 1-month interval between courses. The lesion resolved without any adverse events.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online January 15, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:765-769.

- Hernandez C, Ivkovic A, Fowler A. Growing plaque on foot. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:603-605.

- Hwang SW, Kim JW, Park SW, et al. Two cases of pigmented Bowen’s disease. Ann Dermatol 2002;14:127-129.

- Wilmer EM, Lee KC, Higgins W 2nd, et al. Hyperpigmented palmar plaque: an unexpected diagnosis of Bowen disease. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18573.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Gonçalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-884.

- Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:995-1000.

- Öztürk Durmaz E, Dog˘ an Ekici I, Ozian F, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease of the genitalia masquerading as malignant melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:130-133.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online January 15, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:765-769.

- Hernandez C, Ivkovic A, Fowler A. Growing plaque on foot. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:603-605.

- Hwang SW, Kim JW, Park SW, et al. Two cases of pigmented Bowen’s disease. Ann Dermatol 2002;14:127-129.

- Wilmer EM, Lee KC, Higgins W 2nd, et al. Hyperpigmented palmar plaque: an unexpected diagnosis of Bowen disease. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18573.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Gonçalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-884.

- Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:995-1000.

- Öztürk Durmaz E, Dog˘ an Ekici I, Ozian F, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease of the genitalia masquerading as malignant melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:130-133.

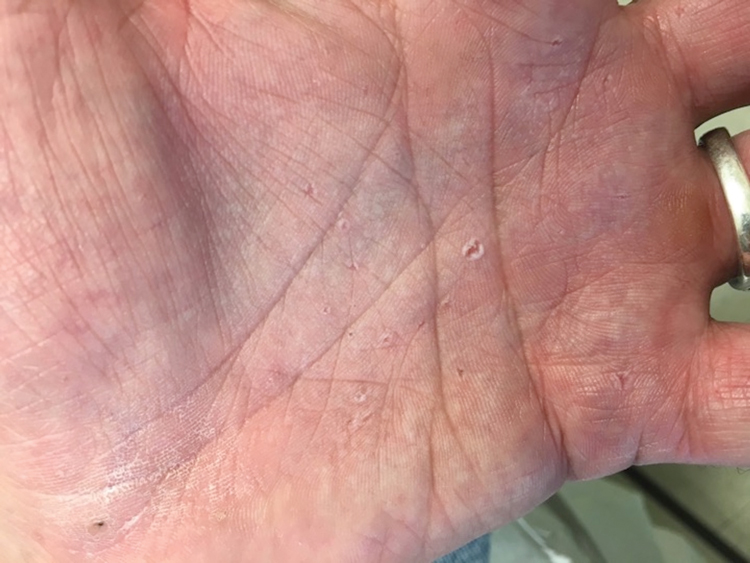

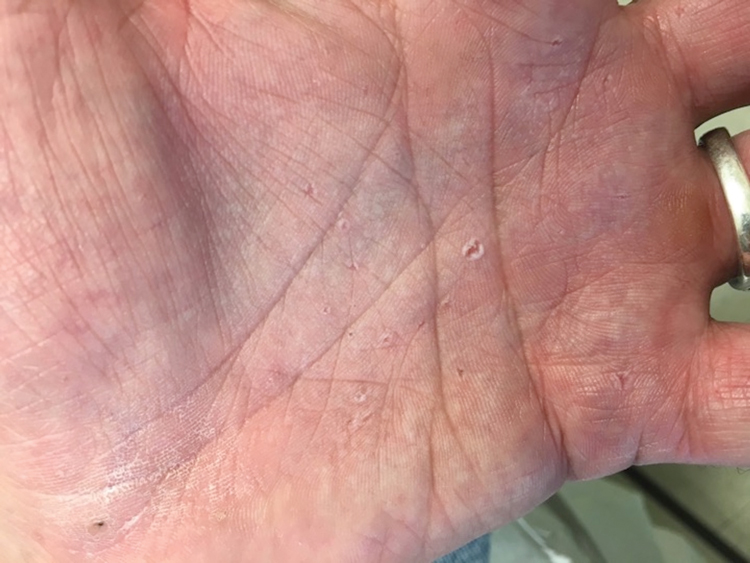

A 56-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic plaque on the right heel that had grown

steadily over the last year. Pigmented lesions were not appreciated on other sites, and lymph nodes were not enlarged. Her medical history was otherwise normal, except for bilateral hearing loss due to encephalitis at the age of 5 years. None of her family members had similar symptoms. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, irregularly hyperpigmented plaque on the right heel.

Large Hemorrhagic Plaque With Central Crusting

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

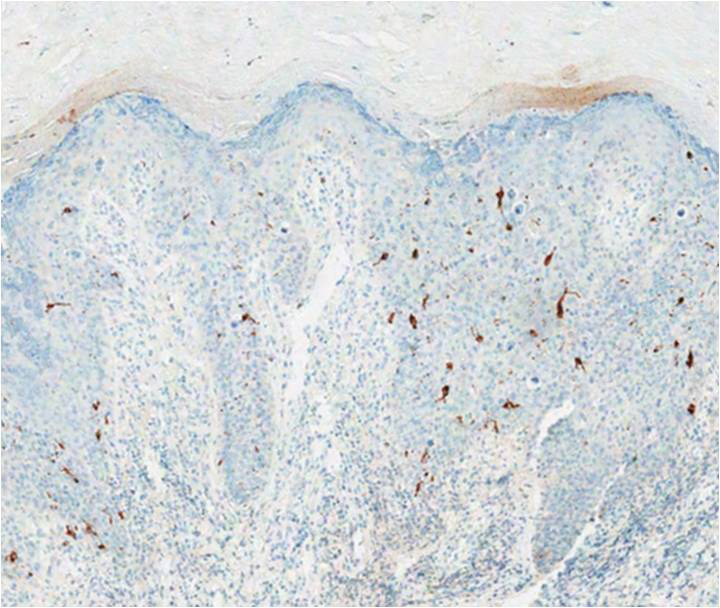

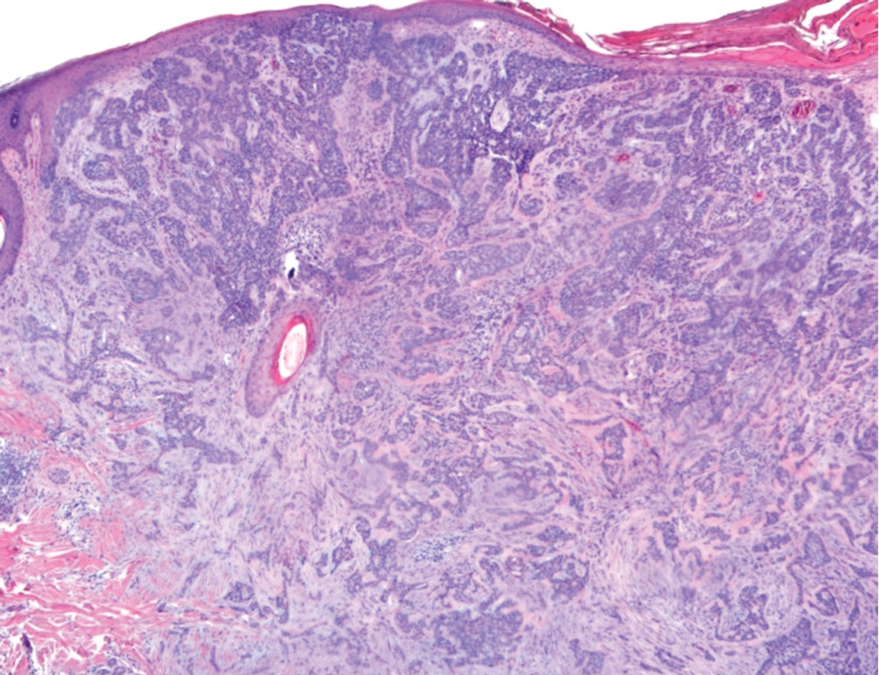

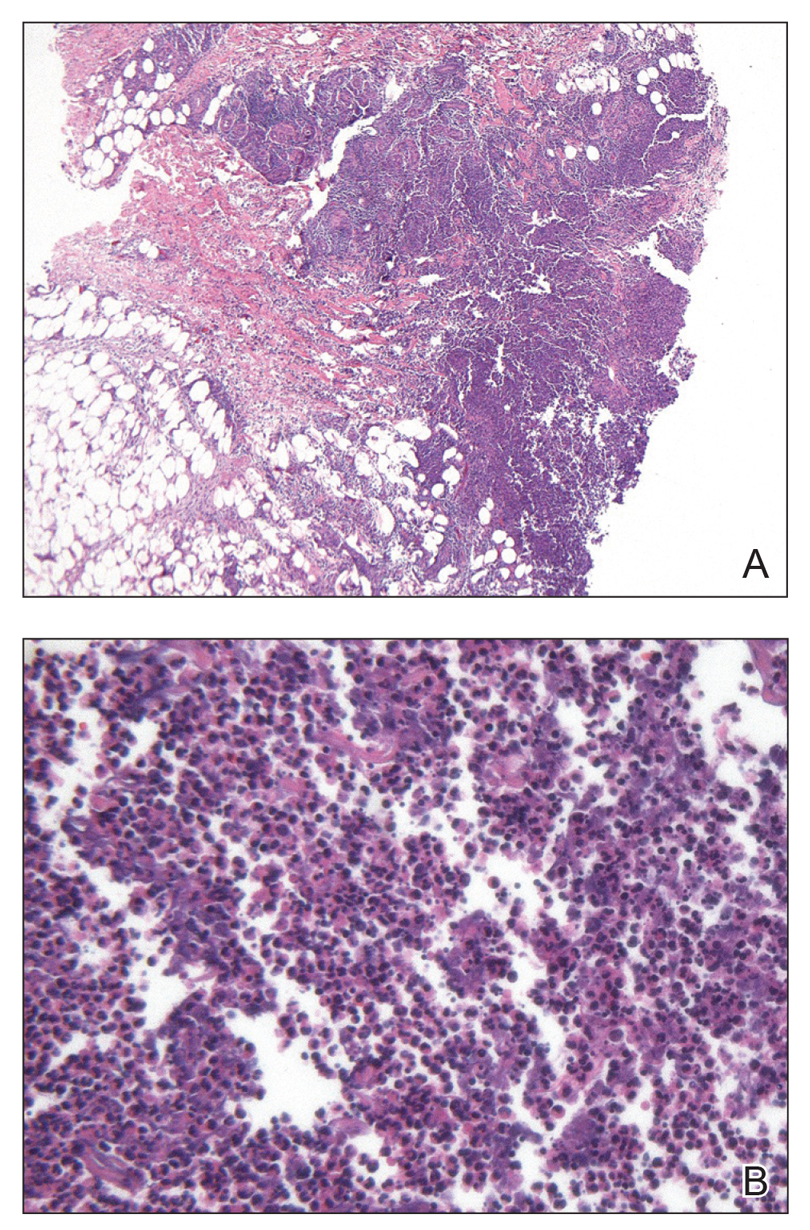

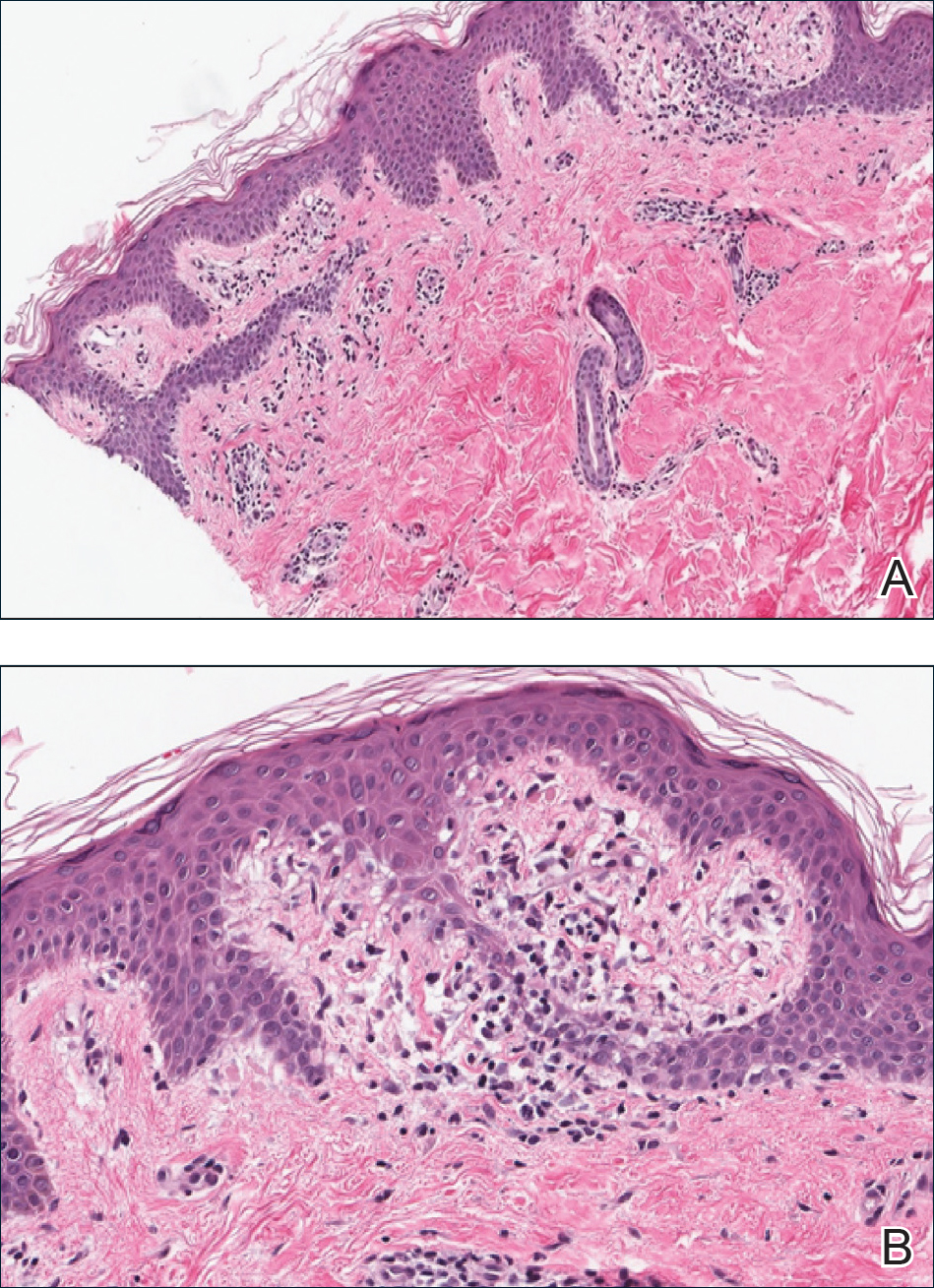

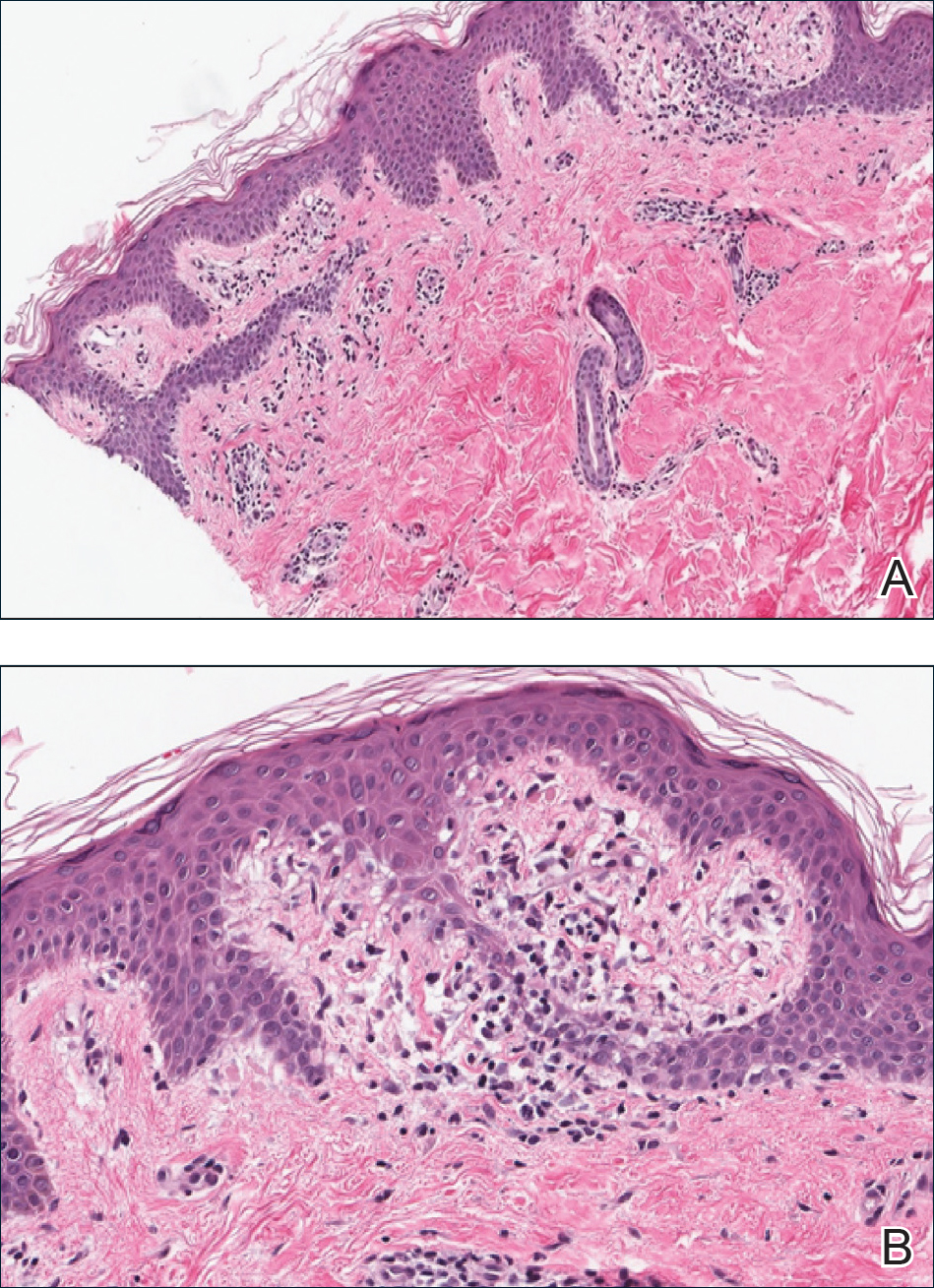

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

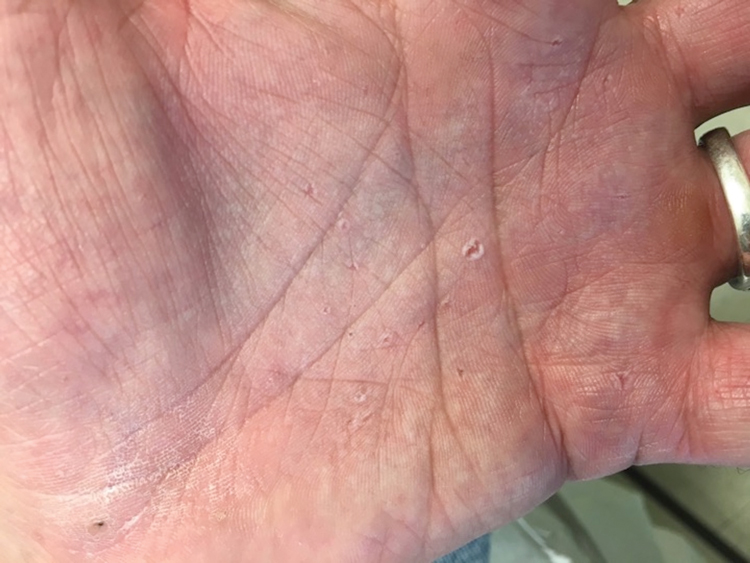

A 54-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to dermatology by her primary care provider for evaluation of a hematoma on the posterior neck that had developed gradually over 5 months. The lesion initially was asymptomatic but more recently had started to be painful and bleed intermittently. The patient denied any personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a large hemorrhagic plaque on the left side of the posterior neck with central brown-yellow crusting. There were few smaller, white, thin, sclerotic plaques with crinkling atrophy at the periphery of and inferolateral to the lesion. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the hemorrhagic plaque.

Erythematous Periumbilical Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

A 75-year-old woman (patient 1) with a history of localized invasive ductal breast cancer treated definitively with lumpectomy and radiation therapy more than a decade ago presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple periumbilical pink-red papules (top) of 2 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 10 days of acyclovir treatment prescribed by her primary care physician for presumed herpes zoster.

An 86-year-old man (patient 2) with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple pink periumbilical papules (bottom) of 6 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 21 days of valacyclovir treatment prescribed by his oncologist for presumed herpes zoster.

Small White Spots on the Lips

The Diagnosis: Fordyce Granules

Fordyce granules are prevalent benign anatomic variations that occur in approximately 80% of the population.1 The spots usually present as multiple (usually >10) 1- to 2-mm, painless, yellow-white papules in a symmetric bilateral distribution. They are normal superficial sebaceous glands seen on mucosal surfaces including the oral mucosa, lips, and genitalia. The papules are asymptomatic, and patients often are unaware of their presence. They can appear at any age and can last for months to years. No treatment is indicated, and patients need only reassurance.1

There are several differential diagnoses.2 Granular cell tumors present as solitary, yellowish or pink, slightly indurated, nonmobile, firm masses that usually measure less than 2 cm in diameter and can be associated with local paresthesia. The oral cavity is the second most common site after the skin and usually involves the dorsum of the tongue; however, granular cell tumors also may develop in the substance of the buccal mucosa, lips, or floor of the mouth. On histopathology, the neoplasm is composed of cells with granular cytoplasm that is of neural origin. Granular cell tumors are slow growing and may be present for months. The mean age of onset is in the fourth decade, and females are more likely to be affected. Excisional biopsy is diagnostic and curative.2

Mucoceles of the mouth are solitary, bluish clear, fluctuant, dome-shaped, well-demarcated nodules that usually appear on the lower lip.3 They are caused by rupture of a salivary gland duct due to minor trauma. Mucin is excreted into the surrounding soft tissues, leading to abrupt nontender swelling over the next several weeks. If they originate deeper within the lip they may appear normal in color. Most range from 1 to 2 mm in diameter but can grow to up to several centimeters in size. Other affected sites may include the ventral tongue, posterior buccal mucosa, or soft palate. Excisional biopsy and conservative surgical excision are recommended for diagnosis and management, respectively.3

Oral leukoplakia is a sharply demarcated, white, mucosal plaque that represents either epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, or hyperkeratosis of unknown etiology. It is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. The patient may present with a hoarse voice and history of tobacco use. The risk for malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma varies from 0% to 20% over the course of 30

years.4 The lesions occur on any mucosal surface, cannot be rubbed off, and usually are asymptomatic.5 The ventral tongue, floor of the mouth, and soft palate are associated with epithelial dysplasia and invasive carcinoma more often than other mucosal sites. There are 2 main types of leukoplakia: localized (unilateral plaque) and proliferative. Because of the risk for cancer, biopsy always is indicated and should be taken from different areas of the lesion (ie, red, verrucous, or nodular areas) if the lesion is nonhomogeneous. Treatment involves excision in the setting of dysplasia or invasive carcinoma. Photodynamic therapy has been shown to reduce the size of oral leukoplakia lesions and is being studied as an alternative therapy.5

Herpes simplex virus type 1 is a common infection of the oral mucosa that classically causes multiple vesicular lesions with an inflammatory erythematous base.6 The lesions are painful and may last for 10 to 14 days. Patients also may develop systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. Once primary infection with herpes simplex virus has occurred, the virus lives in a latent state in ganglion neurons and can reactivate.6

- Massmanian A, Sorni Valls G, Vera Sempere FJ. Fordyce spots on the glans penis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:498-500.

- Lerman M, Freedman PD. Nonneural granular cell tumor of the oral cavity: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:382-384.

- Oka M, Nishioka E, Miyachi R, et al. Case of superficial mucocele of the lower lip. J Dermatol. 2007;34:754-756.

- Lodi G, Sardella A, Bez C, et al. Interventions for treating oral leukoplakia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD001829.

- Selvam NP, Sadaksharam J, Singaravelu G, et al. Treatment of oral leukoplakia with photodynamic therapy: a pilot study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:464-467.

- Klein RS. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection.

The Diagnosis: Fordyce Granules

Fordyce granules are prevalent benign anatomic variations that occur in approximately 80% of the population.1 The spots usually present as multiple (usually >10) 1- to 2-mm, painless, yellow-white papules in a symmetric bilateral distribution. They are normal superficial sebaceous glands seen on mucosal surfaces including the oral mucosa, lips, and genitalia. The papules are asymptomatic, and patients often are unaware of their presence. They can appear at any age and can last for months to years. No treatment is indicated, and patients need only reassurance.1

There are several differential diagnoses.2 Granular cell tumors present as solitary, yellowish or pink, slightly indurated, nonmobile, firm masses that usually measure less than 2 cm in diameter and can be associated with local paresthesia. The oral cavity is the second most common site after the skin and usually involves the dorsum of the tongue; however, granular cell tumors also may develop in the substance of the buccal mucosa, lips, or floor of the mouth. On histopathology, the neoplasm is composed of cells with granular cytoplasm that is of neural origin. Granular cell tumors are slow growing and may be present for months. The mean age of onset is in the fourth decade, and females are more likely to be affected. Excisional biopsy is diagnostic and curative.2

Mucoceles of the mouth are solitary, bluish clear, fluctuant, dome-shaped, well-demarcated nodules that usually appear on the lower lip.3 They are caused by rupture of a salivary gland duct due to minor trauma. Mucin is excreted into the surrounding soft tissues, leading to abrupt nontender swelling over the next several weeks. If they originate deeper within the lip they may appear normal in color. Most range from 1 to 2 mm in diameter but can grow to up to several centimeters in size. Other affected sites may include the ventral tongue, posterior buccal mucosa, or soft palate. Excisional biopsy and conservative surgical excision are recommended for diagnosis and management, respectively.3

Oral leukoplakia is a sharply demarcated, white, mucosal plaque that represents either epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, or hyperkeratosis of unknown etiology. It is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. The patient may present with a hoarse voice and history of tobacco use. The risk for malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma varies from 0% to 20% over the course of 30

years.4 The lesions occur on any mucosal surface, cannot be rubbed off, and usually are asymptomatic.5 The ventral tongue, floor of the mouth, and soft palate are associated with epithelial dysplasia and invasive carcinoma more often than other mucosal sites. There are 2 main types of leukoplakia: localized (unilateral plaque) and proliferative. Because of the risk for cancer, biopsy always is indicated and should be taken from different areas of the lesion (ie, red, verrucous, or nodular areas) if the lesion is nonhomogeneous. Treatment involves excision in the setting of dysplasia or invasive carcinoma. Photodynamic therapy has been shown to reduce the size of oral leukoplakia lesions and is being studied as an alternative therapy.5

Herpes simplex virus type 1 is a common infection of the oral mucosa that classically causes multiple vesicular lesions with an inflammatory erythematous base.6 The lesions are painful and may last for 10 to 14 days. Patients also may develop systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. Once primary infection with herpes simplex virus has occurred, the virus lives in a latent state in ganglion neurons and can reactivate.6

The Diagnosis: Fordyce Granules

Fordyce granules are prevalent benign anatomic variations that occur in approximately 80% of the population.1 The spots usually present as multiple (usually >10) 1- to 2-mm, painless, yellow-white papules in a symmetric bilateral distribution. They are normal superficial sebaceous glands seen on mucosal surfaces including the oral mucosa, lips, and genitalia. The papules are asymptomatic, and patients often are unaware of their presence. They can appear at any age and can last for months to years. No treatment is indicated, and patients need only reassurance.1

There are several differential diagnoses.2 Granular cell tumors present as solitary, yellowish or pink, slightly indurated, nonmobile, firm masses that usually measure less than 2 cm in diameter and can be associated with local paresthesia. The oral cavity is the second most common site after the skin and usually involves the dorsum of the tongue; however, granular cell tumors also may develop in the substance of the buccal mucosa, lips, or floor of the mouth. On histopathology, the neoplasm is composed of cells with granular cytoplasm that is of neural origin. Granular cell tumors are slow growing and may be present for months. The mean age of onset is in the fourth decade, and females are more likely to be affected. Excisional biopsy is diagnostic and curative.2

Mucoceles of the mouth are solitary, bluish clear, fluctuant, dome-shaped, well-demarcated nodules that usually appear on the lower lip.3 They are caused by rupture of a salivary gland duct due to minor trauma. Mucin is excreted into the surrounding soft tissues, leading to abrupt nontender swelling over the next several weeks. If they originate deeper within the lip they may appear normal in color. Most range from 1 to 2 mm in diameter but can grow to up to several centimeters in size. Other affected sites may include the ventral tongue, posterior buccal mucosa, or soft palate. Excisional biopsy and conservative surgical excision are recommended for diagnosis and management, respectively.3

Oral leukoplakia is a sharply demarcated, white, mucosal plaque that represents either epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, or hyperkeratosis of unknown etiology. It is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. The patient may present with a hoarse voice and history of tobacco use. The risk for malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma varies from 0% to 20% over the course of 30

years.4 The lesions occur on any mucosal surface, cannot be rubbed off, and usually are asymptomatic.5 The ventral tongue, floor of the mouth, and soft palate are associated with epithelial dysplasia and invasive carcinoma more often than other mucosal sites. There are 2 main types of leukoplakia: localized (unilateral plaque) and proliferative. Because of the risk for cancer, biopsy always is indicated and should be taken from different areas of the lesion (ie, red, verrucous, or nodular areas) if the lesion is nonhomogeneous. Treatment involves excision in the setting of dysplasia or invasive carcinoma. Photodynamic therapy has been shown to reduce the size of oral leukoplakia lesions and is being studied as an alternative therapy.5

Herpes simplex virus type 1 is a common infection of the oral mucosa that classically causes multiple vesicular lesions with an inflammatory erythematous base.6 The lesions are painful and may last for 10 to 14 days. Patients also may develop systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. Once primary infection with herpes simplex virus has occurred, the virus lives in a latent state in ganglion neurons and can reactivate.6

- Massmanian A, Sorni Valls G, Vera Sempere FJ. Fordyce spots on the glans penis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:498-500.

- Lerman M, Freedman PD. Nonneural granular cell tumor of the oral cavity: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:382-384.

- Oka M, Nishioka E, Miyachi R, et al. Case of superficial mucocele of the lower lip. J Dermatol. 2007;34:754-756.

- Lodi G, Sardella A, Bez C, et al. Interventions for treating oral leukoplakia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD001829.

- Selvam NP, Sadaksharam J, Singaravelu G, et al. Treatment of oral leukoplakia with photodynamic therapy: a pilot study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:464-467.

- Klein RS. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection.

- Massmanian A, Sorni Valls G, Vera Sempere FJ. Fordyce spots on the glans penis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:498-500.

- Lerman M, Freedman PD. Nonneural granular cell tumor of the oral cavity: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:382-384.

- Oka M, Nishioka E, Miyachi R, et al. Case of superficial mucocele of the lower lip. J Dermatol. 2007;34:754-756.

- Lodi G, Sardella A, Bez C, et al. Interventions for treating oral leukoplakia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD001829.

- Selvam NP, Sadaksharam J, Singaravelu G, et al. Treatment of oral leukoplakia with photodynamic therapy: a pilot study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:464-467.

- Klein RS. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection.

White Concretions on the Hair Shaft

The Diagnosis: White Piedra

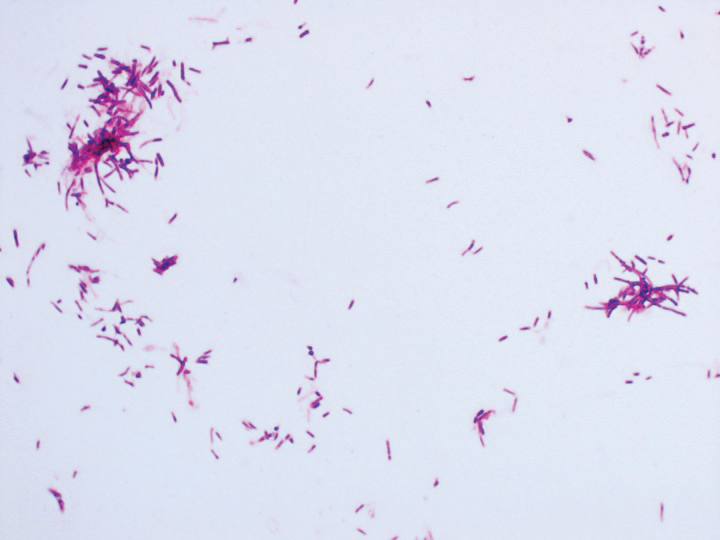

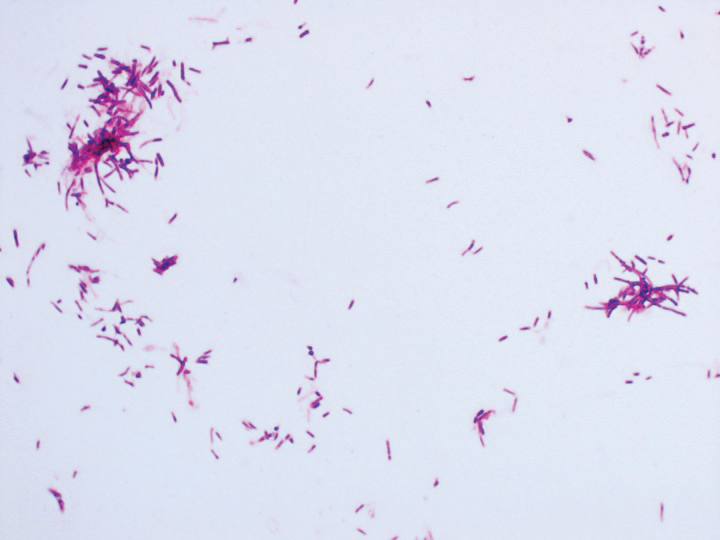

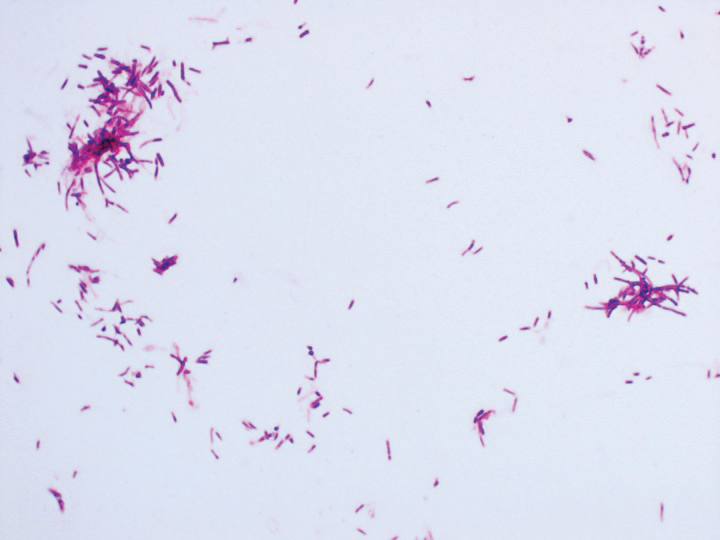

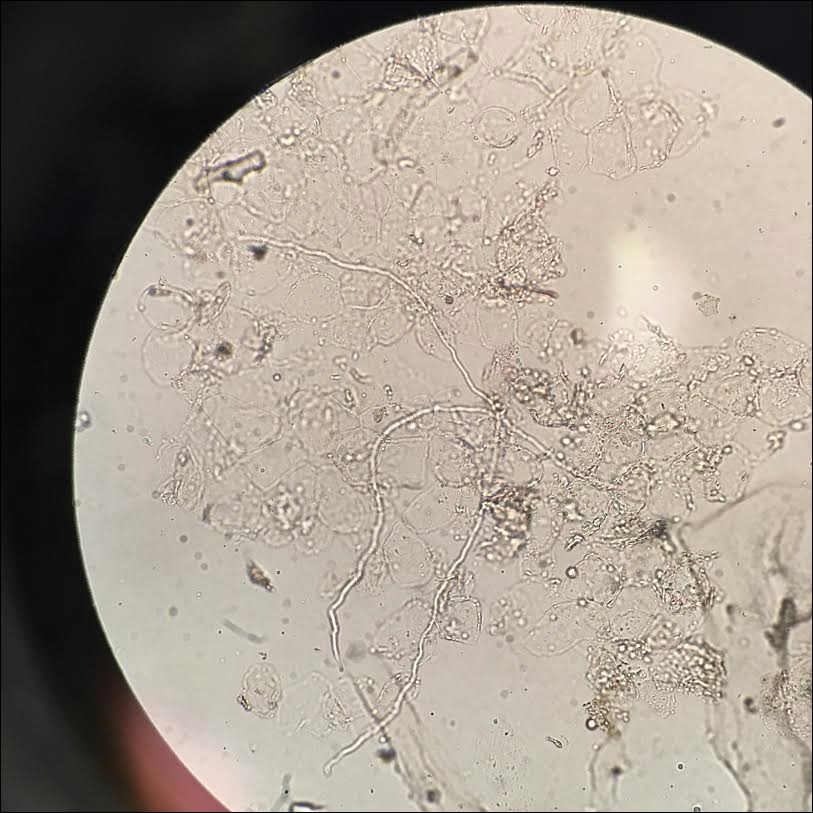

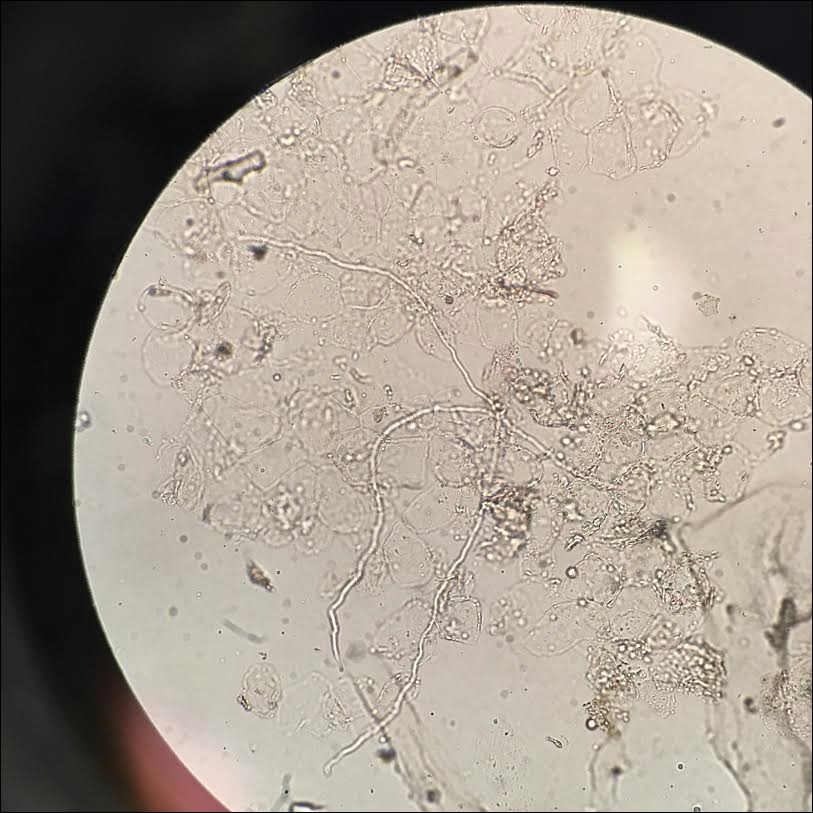

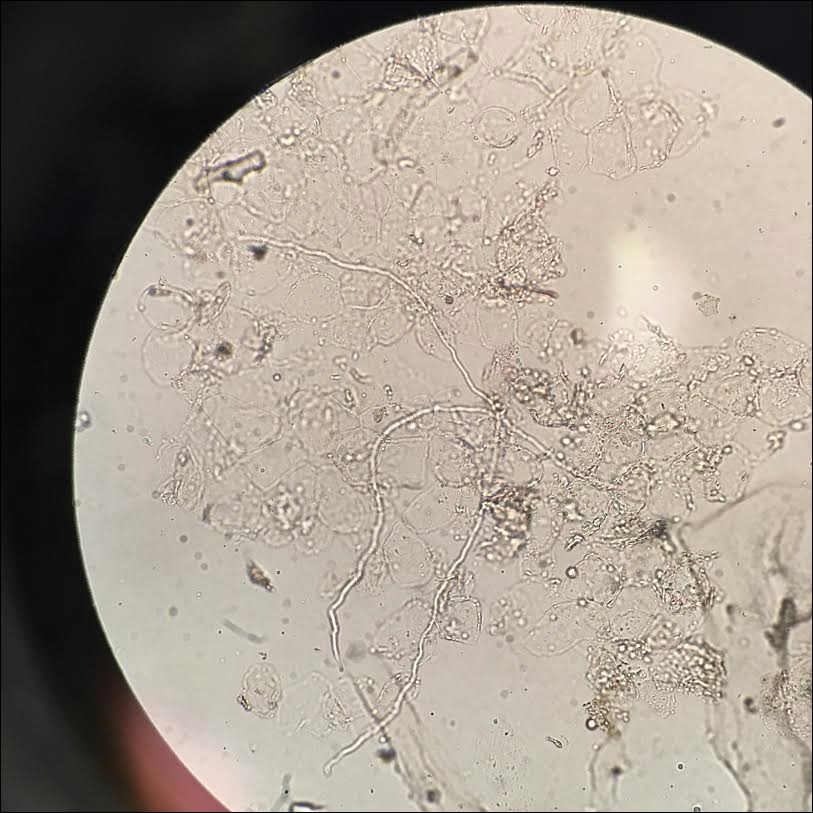

A fungal culture demonstrated a filamentous fungus that was identified as Trichosporon inkin via DNA sequencing, which confirmed the diagnosis of white piedra (WP).

Piedra refers to a group of fungal infections presenting as gritty nodules adherent to the hair shaft.1 It is further categorized into black piedra, which occurs more commonly in tropical climates and is caused by Piedraia hortae, and WP, which occurs in tropical and temperate climates and is caused by the Trichosporon genus.1-3 Among the Trichosporon genus, clinical manifestations have varied based on species; for example, T inkin commonly causes genital WP, Trichosporon ovoides commonly causes scalp WP, and Trichosporon asahii and Trichosporon mucoides have been described to cause systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.1,4 Scalp WP most commonly occurs in children and young adults, and females are at greater risk than males.1,2,5,6

Clinically, WP presents with pale irregular nodules along the hair shaft that are not fluorescent on Wood lamp examination.1,6,7 Nodules are soft and easily detached from the hair shaft, unlike the hard, tightly adherent nodules seen in black piedra.1,7 White piedra affects hair in a variety of areas including the scalp, beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillae, and genitals.1,7 Affected hair may become brittle and break at points of invasion.1 Alternatively, WP may resemble tinea capitis with scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia, though tinea typically affects the base of the hair shaft.1 Immunocompromised patients can develop disseminated WP, and cases of progressive pneumonia, lung abscess, peritonitis, vascular access infection, and endocarditis have been reported.2

Diagnosis of WP is made through a combination of clinical findings and culture of infected hair. Potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrates sleevelike concretions formed of masses of septate hyphae with dense zones of arthrospores and blastospores.1,2 Culture on Sabouraud agar demonstrates creamy colonies that develop a dull, gray, wrinkled surface.1,2 Differential diagnosis includes pediculosis; however, the concretions of WP are circumferential around the hair shaft on microscopy.1 Notably, a case of concomitant WP and pediculosis has been reported.8 In cases of potential pediculosis resistant to therapy, consider hair casts, which are asymptomatic, white, cylindrical concretions that encircle the hair without adherence and can therefore be differentiated from pediculosis via dermoscopy.9 Because this phenomenon is more commonly observed in preadolescent girls, it is hypothesized that scalp inflammation due to traction from hairstyles or atopic dermatitis contributes to the development of hair casts.9,10 Thus, when a potassium hydroxide mount is equivocal for nits and dermoscopy demonstrates concretions that completely encircle the hair shaft, it is important to perform a microbiologic culture to rule out piedra of the hair or scalp. Other differential diagnoses include tinea capitis, black piedra, trichobacteriosis, and hair shaft abnormalities.

Transmission of WP is thought to result from a combination of poor hygiene; humidity due to climate; personal care practices such as habitually tying wet hair, applying hair oils and conditioners, or covering hair according to social customs; and close contact with an infected individual.1,3,6 Long scalp hair potentially correlates with increased risk.1,6 Finally, WP has been described in animals and has been isolated from soil, vegetable matter, and water.3,10

Treatment of WP generally involves removal of infected hair, antifungal agents, and improved hygienic habits to avoid relapses. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines/Outcomes Committee recommends complete removal of infected hair; however, patients may desire hair-preserving treatments.11 Kiken et al1 reported success with the combination of an oral azole antifungal agent for 3 weeks to 1 month and an antifungal shampoo for 2 to 3 months. The authors proposed that oral medication eliminates scalp carriage while antifungal shampoo eliminates hair shaft concretions.1

1. Kiken DA, Sekaran A, Antaya RJ, et al. White piedra in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:956-961.

2. Bonifaz A, Gómez-Daza F, Paredes V, et al. Tinea versicolor, tinea nigra, white piedra, and black piedra. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:140-145.

3. Shivaprakash MR, Singh G, Gupta P, et al. Extensive white piedra of the scalp caused by Trichosporon inkin: a case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:481-486.

4. Goldberg LJ, Wise EM, Miller NS. White piedra caused by Trichosporon inkin: a report of two cases in a northern climate. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:866-868.

5. Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

6. Fischman O, Bezerra FC, Francisco EC, et al. Trichosporon inkin: an uncommon agent of scalp white piedra. report of four cases in Brazilian children. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:85-89.

7. Pontes ZB, Ramos AL, Lima Ede O, et al. Clinical and mycological study of scalp white piedra in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:747-750.

8. Marques SA, Richini-Pereira VB, Camargo RM. White piedra and pediculosis capitis in the same patient. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:786-787.

9. Gnarra M, Saraceni P, Rossi A, et al. Challenging diagnosis of peripillous sheaths. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:E112-E113.

10. França K, Villa RT, Silva IR, et al. Hair casts or pseudonits. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:121-122.

11. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: piedra. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:122-124.

The Diagnosis: White Piedra

A fungal culture demonstrated a filamentous fungus that was identified as Trichosporon inkin via DNA sequencing, which confirmed the diagnosis of white piedra (WP).

Piedra refers to a group of fungal infections presenting as gritty nodules adherent to the hair shaft.1 It is further categorized into black piedra, which occurs more commonly in tropical climates and is caused by Piedraia hortae, and WP, which occurs in tropical and temperate climates and is caused by the Trichosporon genus.1-3 Among the Trichosporon genus, clinical manifestations have varied based on species; for example, T inkin commonly causes genital WP, Trichosporon ovoides commonly causes scalp WP, and Trichosporon asahii and Trichosporon mucoides have been described to cause systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.1,4 Scalp WP most commonly occurs in children and young adults, and females are at greater risk than males.1,2,5,6

Clinically, WP presents with pale irregular nodules along the hair shaft that are not fluorescent on Wood lamp examination.1,6,7 Nodules are soft and easily detached from the hair shaft, unlike the hard, tightly adherent nodules seen in black piedra.1,7 White piedra affects hair in a variety of areas including the scalp, beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillae, and genitals.1,7 Affected hair may become brittle and break at points of invasion.1 Alternatively, WP may resemble tinea capitis with scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia, though tinea typically affects the base of the hair shaft.1 Immunocompromised patients can develop disseminated WP, and cases of progressive pneumonia, lung abscess, peritonitis, vascular access infection, and endocarditis have been reported.2

Diagnosis of WP is made through a combination of clinical findings and culture of infected hair. Potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrates sleevelike concretions formed of masses of septate hyphae with dense zones of arthrospores and blastospores.1,2 Culture on Sabouraud agar demonstrates creamy colonies that develop a dull, gray, wrinkled surface.1,2 Differential diagnosis includes pediculosis; however, the concretions of WP are circumferential around the hair shaft on microscopy.1 Notably, a case of concomitant WP and pediculosis has been reported.8 In cases of potential pediculosis resistant to therapy, consider hair casts, which are asymptomatic, white, cylindrical concretions that encircle the hair without adherence and can therefore be differentiated from pediculosis via dermoscopy.9 Because this phenomenon is more commonly observed in preadolescent girls, it is hypothesized that scalp inflammation due to traction from hairstyles or atopic dermatitis contributes to the development of hair casts.9,10 Thus, when a potassium hydroxide mount is equivocal for nits and dermoscopy demonstrates concretions that completely encircle the hair shaft, it is important to perform a microbiologic culture to rule out piedra of the hair or scalp. Other differential diagnoses include tinea capitis, black piedra, trichobacteriosis, and hair shaft abnormalities.

Transmission of WP is thought to result from a combination of poor hygiene; humidity due to climate; personal care practices such as habitually tying wet hair, applying hair oils and conditioners, or covering hair according to social customs; and close contact with an infected individual.1,3,6 Long scalp hair potentially correlates with increased risk.1,6 Finally, WP has been described in animals and has been isolated from soil, vegetable matter, and water.3,10

Treatment of WP generally involves removal of infected hair, antifungal agents, and improved hygienic habits to avoid relapses. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines/Outcomes Committee recommends complete removal of infected hair; however, patients may desire hair-preserving treatments.11 Kiken et al1 reported success with the combination of an oral azole antifungal agent for 3 weeks to 1 month and an antifungal shampoo for 2 to 3 months. The authors proposed that oral medication eliminates scalp carriage while antifungal shampoo eliminates hair shaft concretions.1

The Diagnosis: White Piedra

A fungal culture demonstrated a filamentous fungus that was identified as Trichosporon inkin via DNA sequencing, which confirmed the diagnosis of white piedra (WP).

Piedra refers to a group of fungal infections presenting as gritty nodules adherent to the hair shaft.1 It is further categorized into black piedra, which occurs more commonly in tropical climates and is caused by Piedraia hortae, and WP, which occurs in tropical and temperate climates and is caused by the Trichosporon genus.1-3 Among the Trichosporon genus, clinical manifestations have varied based on species; for example, T inkin commonly causes genital WP, Trichosporon ovoides commonly causes scalp WP, and Trichosporon asahii and Trichosporon mucoides have been described to cause systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.1,4 Scalp WP most commonly occurs in children and young adults, and females are at greater risk than males.1,2,5,6

Clinically, WP presents with pale irregular nodules along the hair shaft that are not fluorescent on Wood lamp examination.1,6,7 Nodules are soft and easily detached from the hair shaft, unlike the hard, tightly adherent nodules seen in black piedra.1,7 White piedra affects hair in a variety of areas including the scalp, beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, axillae, and genitals.1,7 Affected hair may become brittle and break at points of invasion.1 Alternatively, WP may resemble tinea capitis with scalp hyperkeratosis and alopecia, though tinea typically affects the base of the hair shaft.1 Immunocompromised patients can develop disseminated WP, and cases of progressive pneumonia, lung abscess, peritonitis, vascular access infection, and endocarditis have been reported.2

Diagnosis of WP is made through a combination of clinical findings and culture of infected hair. Potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrates sleevelike concretions formed of masses of septate hyphae with dense zones of arthrospores and blastospores.1,2 Culture on Sabouraud agar demonstrates creamy colonies that develop a dull, gray, wrinkled surface.1,2 Differential diagnosis includes pediculosis; however, the concretions of WP are circumferential around the hair shaft on microscopy.1 Notably, a case of concomitant WP and pediculosis has been reported.8 In cases of potential pediculosis resistant to therapy, consider hair casts, which are asymptomatic, white, cylindrical concretions that encircle the hair without adherence and can therefore be differentiated from pediculosis via dermoscopy.9 Because this phenomenon is more commonly observed in preadolescent girls, it is hypothesized that scalp inflammation due to traction from hairstyles or atopic dermatitis contributes to the development of hair casts.9,10 Thus, when a potassium hydroxide mount is equivocal for nits and dermoscopy demonstrates concretions that completely encircle the hair shaft, it is important to perform a microbiologic culture to rule out piedra of the hair or scalp. Other differential diagnoses include tinea capitis, black piedra, trichobacteriosis, and hair shaft abnormalities.

Transmission of WP is thought to result from a combination of poor hygiene; humidity due to climate; personal care practices such as habitually tying wet hair, applying hair oils and conditioners, or covering hair according to social customs; and close contact with an infected individual.1,3,6 Long scalp hair potentially correlates with increased risk.1,6 Finally, WP has been described in animals and has been isolated from soil, vegetable matter, and water.3,10

Treatment of WP generally involves removal of infected hair, antifungal agents, and improved hygienic habits to avoid relapses. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Guidelines/Outcomes Committee recommends complete removal of infected hair; however, patients may desire hair-preserving treatments.11 Kiken et al1 reported success with the combination of an oral azole antifungal agent for 3 weeks to 1 month and an antifungal shampoo for 2 to 3 months. The authors proposed that oral medication eliminates scalp carriage while antifungal shampoo eliminates hair shaft concretions.1

1. Kiken DA, Sekaran A, Antaya RJ, et al. White piedra in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:956-961.

2. Bonifaz A, Gómez-Daza F, Paredes V, et al. Tinea versicolor, tinea nigra, white piedra, and black piedra. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:140-145.

3. Shivaprakash MR, Singh G, Gupta P, et al. Extensive white piedra of the scalp caused by Trichosporon inkin: a case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:481-486.

4. Goldberg LJ, Wise EM, Miller NS. White piedra caused by Trichosporon inkin: a report of two cases in a northern climate. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:866-868.

5. Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

6. Fischman O, Bezerra FC, Francisco EC, et al. Trichosporon inkin: an uncommon agent of scalp white piedra. report of four cases in Brazilian children. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:85-89.

7. Pontes ZB, Ramos AL, Lima Ede O, et al. Clinical and mycological study of scalp white piedra in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:747-750.

8. Marques SA, Richini-Pereira VB, Camargo RM. White piedra and pediculosis capitis in the same patient. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:786-787.

9. Gnarra M, Saraceni P, Rossi A, et al. Challenging diagnosis of peripillous sheaths. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:E112-E113.

10. França K, Villa RT, Silva IR, et al. Hair casts or pseudonits. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:121-122.