User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Will New Obesity Drugs Make Bariatric Surgery Obsolete?

MADRID — In spirited presentations at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Louis J. Aronne, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, made a compelling case that the next generation of obesity medications will make bariatric surgery obsolete, and Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London in England, made an equally compelling case that they will not.

In fact, Dr. Rubino predicted that “metabolic” surgery — new nomenclature reflecting the power of surgery to reduce not only obesity, but also other metabolic conditions, over the long term — will continue and could even increase in years to come.

‘Medical Treatment Will Dominate’

“Obesity treatment is the superhero of treating metabolic disease because it can defeat all of the bad guys at once, not just one, like the other treatments,” Dr. Aronne told meeting attendees. “If you treat somebody’s cholesterol, you’re just treating their cholesterol, and you may actually increase their risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). You treat their blood pressure, you don’t treat their glucose and you don’t treat their lipids — the list goes on and on and on. But by treating obesity, if you can get enough weight loss, you can get all those things at once.”

He pointed to the SELECT trial, which showed that treating obesity with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist reduced major adverse cardiovascular events as well as death from any cause, results in line with those from other modes of treatment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) or lipid lowering, he said. “But we get much more with these drugs, including positive effects on heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a 73% reduction in T2D. So, we’re now on the verge of a major change in the way we manage metabolic disease.”

Dr. Aronne drew a parallel between treating obesity and the historic way of treating hypertension. Years ago, he said, “we waited too long to treat people. We waited until they had severe hypertension that in many cases was irreversible. What would you prefer to do now for obesity — have the patient lose weight with a medicine that is proven to reduce complications or wait until they develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and then have them undergo surgery to treat that?”

Looking ahead, “the trend could be to treat obesity before it gets out of hand,” he suggested. Treatment might start in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2, who would be treated to a target BMI of 25. “That’s only a 10% or so change, but our goal would be to keep them in the normal range so they never go above that target. In fact, I think we’re going to be looking at people with severe obesity in a few years and saying, ‘I can’t believe someone didn’t treat that guy earlier.’ What’s going to happen to bariatric surgery if no one gets to a higher weight?”

The plethora of current weight-loss drugs and the large group on the horizon mean that if someone doesn’t respond to one drug, there will be plenty of other choices, Dr. Aronne continued. People will be referred for surgery, but possibly only after they’ve not responded to medical treatment — or just the opposite. “In the United States, it’s much cheaper to have surgery, and I bet the insurance companies are going to make people have surgery before they can get the medicines,” he acknowledged.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley suggests that the global market for the newer weight-loss drugs could increase by 15-fold over the next 5 years as their benefits expand beyond weight loss and that as much as 9% of the US population will be taking the drugs by 2035, Dr. Aronne said, adding that he thinks 9% is an underestimate. By contrast, the number of patients treated by his team’s surgical program is down about 20%.

“I think it’s very clear that medical treatment is going to dominate,” he concluded. “But, it’s also possible that surgery could go up because so many people are going to be coming for medical therapy that we may wind up referring more for surgical therapy.”

‘Surgery Is Saving Lives’

Dr. Rubino is convinced that anti-obesity drugs will not make surgery obsolete, “but it will not be business as usual,” he told meeting attendees. “In fact, I think these drugs will expedite a process that is already ongoing — a transformation of bariatric into metabolic surgery.”

“Bariatric surgery will go down in history as one of the biggest missed opportunities that we, as medical professionals, have seen over the past many years,” he said. “It has been shown beyond any doubt to reduce all-cause mortality — in other words, it saves lives,” and it’s also cost effective and improves quality of life. Yet, fewer than 1% of people globally who meet the criteria actually get the surgery.

Many clinicians don’t inform patients about the treatment and don’t refer them for it, he said. “That would be equivalent to having surgery for CVD [cardiovascular disease], cancer, or other important diseases available but not being accessed as they should be.”

A big reason for the dearth of procedures is that people have unrealistic expectations about diet and exercise interventions for weight loss, he said. His team’s survey, presented at the 26th World Congress of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, showed that 43% of respondents believed diet and exercise was the best treatment for severe obesity (BMI > 35). A more recent survey asked which among several choices was the most effective weight-loss intervention, and again a large proportion “believed wrongly that diet and exercise is most effective — more so than drugs or surgery — despite plenty of evidence that this is not the case.”

In this context, he said, “any surgery, no matter how safe or effective, would never be very popular.” If obesity is viewed as a modifiable risk factor, patients may say they’ll think about it for 6 months. In contrast, “nobody will tell you ‘I will think about it’ if you tell them they need gallbladder surgery to get rid of gallstone pain.”

Although drugs are available to treat obesity, none of them are curative, and if they’re stopped, the weight comes back, Dr. Rubino pointed out. “Efficacy of drugs is measured in weeks or months, whereas efficacy of surgery is measured in decades of durability — in the case of bariatric surgery, 10-20 years. That’s why bariatric surgery will remain an option,” he said. “It’s not just preventing disease, it’s resolving ongoing disease.”

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is showing value for people with established T2D, whereas in the past, it was mainly considered to be a weight-loss intervention for younger, healthier patients, he said. “In my practice, we’re operating more often in people with T2D, even those at higher risk for anesthesia and surgery — eg, patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, on dialysis — and we’re still able to maintain the same safety with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that we had with healthier patients.”

A vote held at the end of the session revealed that the audience was split about half and half in favor of drugs making bariatric surgery obsolete or not.

“I think we may have to duke it out now,” Dr. Aronne quipped.

Dr. Aronne disclosed being a consultant, speaker, and adviser for and receiving research support from Altimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Intellihealth, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Senda, UnitedHealth Group, Versanis, and others; he has ownership interests in ERX, Intellihealth, Jamieson, Kallyope, Skye Bioscience, Veru, and others; and he is on the board of directors of ERX, Jamieson Wellness, and Intellihealth/FlyteHealth. Dr. Rubino disclosed receiving research and educational grants from Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic; he is on the scientific advisory board/data safety advisory board for Keyron, Morphic Medical, and GT Metabolic Solutions; he receives speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Ethicon, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; and he is president of the nonprofit Metabolic Health Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID — In spirited presentations at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Louis J. Aronne, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, made a compelling case that the next generation of obesity medications will make bariatric surgery obsolete, and Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London in England, made an equally compelling case that they will not.

In fact, Dr. Rubino predicted that “metabolic” surgery — new nomenclature reflecting the power of surgery to reduce not only obesity, but also other metabolic conditions, over the long term — will continue and could even increase in years to come.

‘Medical Treatment Will Dominate’

“Obesity treatment is the superhero of treating metabolic disease because it can defeat all of the bad guys at once, not just one, like the other treatments,” Dr. Aronne told meeting attendees. “If you treat somebody’s cholesterol, you’re just treating their cholesterol, and you may actually increase their risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). You treat their blood pressure, you don’t treat their glucose and you don’t treat their lipids — the list goes on and on and on. But by treating obesity, if you can get enough weight loss, you can get all those things at once.”

He pointed to the SELECT trial, which showed that treating obesity with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist reduced major adverse cardiovascular events as well as death from any cause, results in line with those from other modes of treatment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) or lipid lowering, he said. “But we get much more with these drugs, including positive effects on heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a 73% reduction in T2D. So, we’re now on the verge of a major change in the way we manage metabolic disease.”

Dr. Aronne drew a parallel between treating obesity and the historic way of treating hypertension. Years ago, he said, “we waited too long to treat people. We waited until they had severe hypertension that in many cases was irreversible. What would you prefer to do now for obesity — have the patient lose weight with a medicine that is proven to reduce complications or wait until they develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and then have them undergo surgery to treat that?”

Looking ahead, “the trend could be to treat obesity before it gets out of hand,” he suggested. Treatment might start in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2, who would be treated to a target BMI of 25. “That’s only a 10% or so change, but our goal would be to keep them in the normal range so they never go above that target. In fact, I think we’re going to be looking at people with severe obesity in a few years and saying, ‘I can’t believe someone didn’t treat that guy earlier.’ What’s going to happen to bariatric surgery if no one gets to a higher weight?”

The plethora of current weight-loss drugs and the large group on the horizon mean that if someone doesn’t respond to one drug, there will be plenty of other choices, Dr. Aronne continued. People will be referred for surgery, but possibly only after they’ve not responded to medical treatment — or just the opposite. “In the United States, it’s much cheaper to have surgery, and I bet the insurance companies are going to make people have surgery before they can get the medicines,” he acknowledged.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley suggests that the global market for the newer weight-loss drugs could increase by 15-fold over the next 5 years as their benefits expand beyond weight loss and that as much as 9% of the US population will be taking the drugs by 2035, Dr. Aronne said, adding that he thinks 9% is an underestimate. By contrast, the number of patients treated by his team’s surgical program is down about 20%.

“I think it’s very clear that medical treatment is going to dominate,” he concluded. “But, it’s also possible that surgery could go up because so many people are going to be coming for medical therapy that we may wind up referring more for surgical therapy.”

‘Surgery Is Saving Lives’

Dr. Rubino is convinced that anti-obesity drugs will not make surgery obsolete, “but it will not be business as usual,” he told meeting attendees. “In fact, I think these drugs will expedite a process that is already ongoing — a transformation of bariatric into metabolic surgery.”

“Bariatric surgery will go down in history as one of the biggest missed opportunities that we, as medical professionals, have seen over the past many years,” he said. “It has been shown beyond any doubt to reduce all-cause mortality — in other words, it saves lives,” and it’s also cost effective and improves quality of life. Yet, fewer than 1% of people globally who meet the criteria actually get the surgery.

Many clinicians don’t inform patients about the treatment and don’t refer them for it, he said. “That would be equivalent to having surgery for CVD [cardiovascular disease], cancer, or other important diseases available but not being accessed as they should be.”

A big reason for the dearth of procedures is that people have unrealistic expectations about diet and exercise interventions for weight loss, he said. His team’s survey, presented at the 26th World Congress of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, showed that 43% of respondents believed diet and exercise was the best treatment for severe obesity (BMI > 35). A more recent survey asked which among several choices was the most effective weight-loss intervention, and again a large proportion “believed wrongly that diet and exercise is most effective — more so than drugs or surgery — despite plenty of evidence that this is not the case.”

In this context, he said, “any surgery, no matter how safe or effective, would never be very popular.” If obesity is viewed as a modifiable risk factor, patients may say they’ll think about it for 6 months. In contrast, “nobody will tell you ‘I will think about it’ if you tell them they need gallbladder surgery to get rid of gallstone pain.”

Although drugs are available to treat obesity, none of them are curative, and if they’re stopped, the weight comes back, Dr. Rubino pointed out. “Efficacy of drugs is measured in weeks or months, whereas efficacy of surgery is measured in decades of durability — in the case of bariatric surgery, 10-20 years. That’s why bariatric surgery will remain an option,” he said. “It’s not just preventing disease, it’s resolving ongoing disease.”

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is showing value for people with established T2D, whereas in the past, it was mainly considered to be a weight-loss intervention for younger, healthier patients, he said. “In my practice, we’re operating more often in people with T2D, even those at higher risk for anesthesia and surgery — eg, patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, on dialysis — and we’re still able to maintain the same safety with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that we had with healthier patients.”

A vote held at the end of the session revealed that the audience was split about half and half in favor of drugs making bariatric surgery obsolete or not.

“I think we may have to duke it out now,” Dr. Aronne quipped.

Dr. Aronne disclosed being a consultant, speaker, and adviser for and receiving research support from Altimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Intellihealth, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Senda, UnitedHealth Group, Versanis, and others; he has ownership interests in ERX, Intellihealth, Jamieson, Kallyope, Skye Bioscience, Veru, and others; and he is on the board of directors of ERX, Jamieson Wellness, and Intellihealth/FlyteHealth. Dr. Rubino disclosed receiving research and educational grants from Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic; he is on the scientific advisory board/data safety advisory board for Keyron, Morphic Medical, and GT Metabolic Solutions; he receives speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Ethicon, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; and he is president of the nonprofit Metabolic Health Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID — In spirited presentations at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Louis J. Aronne, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, made a compelling case that the next generation of obesity medications will make bariatric surgery obsolete, and Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London in England, made an equally compelling case that they will not.

In fact, Dr. Rubino predicted that “metabolic” surgery — new nomenclature reflecting the power of surgery to reduce not only obesity, but also other metabolic conditions, over the long term — will continue and could even increase in years to come.

‘Medical Treatment Will Dominate’

“Obesity treatment is the superhero of treating metabolic disease because it can defeat all of the bad guys at once, not just one, like the other treatments,” Dr. Aronne told meeting attendees. “If you treat somebody’s cholesterol, you’re just treating their cholesterol, and you may actually increase their risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). You treat their blood pressure, you don’t treat their glucose and you don’t treat their lipids — the list goes on and on and on. But by treating obesity, if you can get enough weight loss, you can get all those things at once.”

He pointed to the SELECT trial, which showed that treating obesity with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist reduced major adverse cardiovascular events as well as death from any cause, results in line with those from other modes of treatment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) or lipid lowering, he said. “But we get much more with these drugs, including positive effects on heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a 73% reduction in T2D. So, we’re now on the verge of a major change in the way we manage metabolic disease.”

Dr. Aronne drew a parallel between treating obesity and the historic way of treating hypertension. Years ago, he said, “we waited too long to treat people. We waited until they had severe hypertension that in many cases was irreversible. What would you prefer to do now for obesity — have the patient lose weight with a medicine that is proven to reduce complications or wait until they develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and then have them undergo surgery to treat that?”

Looking ahead, “the trend could be to treat obesity before it gets out of hand,” he suggested. Treatment might start in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2, who would be treated to a target BMI of 25. “That’s only a 10% or so change, but our goal would be to keep them in the normal range so they never go above that target. In fact, I think we’re going to be looking at people with severe obesity in a few years and saying, ‘I can’t believe someone didn’t treat that guy earlier.’ What’s going to happen to bariatric surgery if no one gets to a higher weight?”

The plethora of current weight-loss drugs and the large group on the horizon mean that if someone doesn’t respond to one drug, there will be plenty of other choices, Dr. Aronne continued. People will be referred for surgery, but possibly only after they’ve not responded to medical treatment — or just the opposite. “In the United States, it’s much cheaper to have surgery, and I bet the insurance companies are going to make people have surgery before they can get the medicines,” he acknowledged.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley suggests that the global market for the newer weight-loss drugs could increase by 15-fold over the next 5 years as their benefits expand beyond weight loss and that as much as 9% of the US population will be taking the drugs by 2035, Dr. Aronne said, adding that he thinks 9% is an underestimate. By contrast, the number of patients treated by his team’s surgical program is down about 20%.

“I think it’s very clear that medical treatment is going to dominate,” he concluded. “But, it’s also possible that surgery could go up because so many people are going to be coming for medical therapy that we may wind up referring more for surgical therapy.”

‘Surgery Is Saving Lives’

Dr. Rubino is convinced that anti-obesity drugs will not make surgery obsolete, “but it will not be business as usual,” he told meeting attendees. “In fact, I think these drugs will expedite a process that is already ongoing — a transformation of bariatric into metabolic surgery.”

“Bariatric surgery will go down in history as one of the biggest missed opportunities that we, as medical professionals, have seen over the past many years,” he said. “It has been shown beyond any doubt to reduce all-cause mortality — in other words, it saves lives,” and it’s also cost effective and improves quality of life. Yet, fewer than 1% of people globally who meet the criteria actually get the surgery.

Many clinicians don’t inform patients about the treatment and don’t refer them for it, he said. “That would be equivalent to having surgery for CVD [cardiovascular disease], cancer, or other important diseases available but not being accessed as they should be.”

A big reason for the dearth of procedures is that people have unrealistic expectations about diet and exercise interventions for weight loss, he said. His team’s survey, presented at the 26th World Congress of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, showed that 43% of respondents believed diet and exercise was the best treatment for severe obesity (BMI > 35). A more recent survey asked which among several choices was the most effective weight-loss intervention, and again a large proportion “believed wrongly that diet and exercise is most effective — more so than drugs or surgery — despite plenty of evidence that this is not the case.”

In this context, he said, “any surgery, no matter how safe or effective, would never be very popular.” If obesity is viewed as a modifiable risk factor, patients may say they’ll think about it for 6 months. In contrast, “nobody will tell you ‘I will think about it’ if you tell them they need gallbladder surgery to get rid of gallstone pain.”

Although drugs are available to treat obesity, none of them are curative, and if they’re stopped, the weight comes back, Dr. Rubino pointed out. “Efficacy of drugs is measured in weeks or months, whereas efficacy of surgery is measured in decades of durability — in the case of bariatric surgery, 10-20 years. That’s why bariatric surgery will remain an option,” he said. “It’s not just preventing disease, it’s resolving ongoing disease.”

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is showing value for people with established T2D, whereas in the past, it was mainly considered to be a weight-loss intervention for younger, healthier patients, he said. “In my practice, we’re operating more often in people with T2D, even those at higher risk for anesthesia and surgery — eg, patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, on dialysis — and we’re still able to maintain the same safety with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that we had with healthier patients.”

A vote held at the end of the session revealed that the audience was split about half and half in favor of drugs making bariatric surgery obsolete or not.

“I think we may have to duke it out now,” Dr. Aronne quipped.

Dr. Aronne disclosed being a consultant, speaker, and adviser for and receiving research support from Altimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Intellihealth, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Senda, UnitedHealth Group, Versanis, and others; he has ownership interests in ERX, Intellihealth, Jamieson, Kallyope, Skye Bioscience, Veru, and others; and he is on the board of directors of ERX, Jamieson Wellness, and Intellihealth/FlyteHealth. Dr. Rubino disclosed receiving research and educational grants from Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic; he is on the scientific advisory board/data safety advisory board for Keyron, Morphic Medical, and GT Metabolic Solutions; he receives speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Ethicon, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; and he is president of the nonprofit Metabolic Health Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2024

Is Minimal Access Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy a Safer Option?

TOPLINE:

Given that both procedures appear safe overall, the choice may be guided by patients’ preference.

METHODOLOGY:

- Compared with a conventional mastectomy, a nipple-sparing mastectomy offers superior esthetic outcomes in patients with breast cancer. However, even the typical nipple-sparing approach often results in visible scarring and a high risk for nipple or areola necrosis. A minimal access approach, using endoscopic or robotic techniques, offers the potential to minimize scarring and better outcomes, but the complication risks are not well understood.

- Researchers performed a retrospective study that included 1583 patients with breast cancer who underwent conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 1356) or minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 227) between 2018 and 2020 across 21 institutions in the Republic of Korea.

- Postoperative complications, categorized as short term (< 30 days) and long term (< 90 days), were compared between the two groups.

- The minimal access group had a higher percentage of premenopausal patients (73.57% vs 66.67%) and women with firm breasts (66.08% vs 31.27%).

TAKEAWAY:

- In total, 72 individuals (5.31%) in the conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy group and 7 (3.08%) in the minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy group developed postoperative complications of grade IIIb or higher.

- The rate of complications between the conventional and minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy groups in the short term (34.29% for conventional vs 32.16% for minimal access; P = .53) and long term (38.72% vs 32.16%, respectively; P = .06) was not significantly different.

- The conventional group experienced significantly fewer wound infections — both in the short term (1.62% vs 7.49%) and long term (4.28% vs 7.93%) — but a significantly higher rate of seroma (14.23% vs 9.25%), likely because of the variations in surgical instruments used during the procedures.

- Necrosis of the nipple or areola occurred more often in the minimal access group in the short term (8.81% vs 3.91%) but occurred more frequently in the conventional group in the long term (6.71% vs 2.20%).

IN PRACTICE:

“The similar complication rates suggest that both C-NSM [conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy] and M-NSM [minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy] may be equally safe options,” the authors wrote. “Therefore, the choice of surgical approach should be tailored to patient preferences and individual needs.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Joo Heung Kim, MD, Yongin Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Yongin, South Korea, was published online on August 14, 2024, in JAMA Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective design comes with inherent biases. The nonrandom assignment of the participants to the two groups and the relatively small number of cases of minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy may have affected the findings. The involvement of different surgeons and use of early robotic surgery techniques may have introduced bias as well.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by Yonsei University College of Medicine and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Two authors reported receiving grants and consulting fees outside of this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Given that both procedures appear safe overall, the choice may be guided by patients’ preference.

METHODOLOGY:

- Compared with a conventional mastectomy, a nipple-sparing mastectomy offers superior esthetic outcomes in patients with breast cancer. However, even the typical nipple-sparing approach often results in visible scarring and a high risk for nipple or areola necrosis. A minimal access approach, using endoscopic or robotic techniques, offers the potential to minimize scarring and better outcomes, but the complication risks are not well understood.

- Researchers performed a retrospective study that included 1583 patients with breast cancer who underwent conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 1356) or minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 227) between 2018 and 2020 across 21 institutions in the Republic of Korea.

- Postoperative complications, categorized as short term (< 30 days) and long term (< 90 days), were compared between the two groups.

- The minimal access group had a higher percentage of premenopausal patients (73.57% vs 66.67%) and women with firm breasts (66.08% vs 31.27%).

TAKEAWAY:

- In total, 72 individuals (5.31%) in the conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy group and 7 (3.08%) in the minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy group developed postoperative complications of grade IIIb or higher.

- The rate of complications between the conventional and minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy groups in the short term (34.29% for conventional vs 32.16% for minimal access; P = .53) and long term (38.72% vs 32.16%, respectively; P = .06) was not significantly different.

- The conventional group experienced significantly fewer wound infections — both in the short term (1.62% vs 7.49%) and long term (4.28% vs 7.93%) — but a significantly higher rate of seroma (14.23% vs 9.25%), likely because of the variations in surgical instruments used during the procedures.

- Necrosis of the nipple or areola occurred more often in the minimal access group in the short term (8.81% vs 3.91%) but occurred more frequently in the conventional group in the long term (6.71% vs 2.20%).

IN PRACTICE:

“The similar complication rates suggest that both C-NSM [conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy] and M-NSM [minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy] may be equally safe options,” the authors wrote. “Therefore, the choice of surgical approach should be tailored to patient preferences and individual needs.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Joo Heung Kim, MD, Yongin Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Yongin, South Korea, was published online on August 14, 2024, in JAMA Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective design comes with inherent biases. The nonrandom assignment of the participants to the two groups and the relatively small number of cases of minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy may have affected the findings. The involvement of different surgeons and use of early robotic surgery techniques may have introduced bias as well.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by Yonsei University College of Medicine and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Two authors reported receiving grants and consulting fees outside of this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Given that both procedures appear safe overall, the choice may be guided by patients’ preference.

METHODOLOGY:

- Compared with a conventional mastectomy, a nipple-sparing mastectomy offers superior esthetic outcomes in patients with breast cancer. However, even the typical nipple-sparing approach often results in visible scarring and a high risk for nipple or areola necrosis. A minimal access approach, using endoscopic or robotic techniques, offers the potential to minimize scarring and better outcomes, but the complication risks are not well understood.

- Researchers performed a retrospective study that included 1583 patients with breast cancer who underwent conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 1356) or minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 227) between 2018 and 2020 across 21 institutions in the Republic of Korea.

- Postoperative complications, categorized as short term (< 30 days) and long term (< 90 days), were compared between the two groups.

- The minimal access group had a higher percentage of premenopausal patients (73.57% vs 66.67%) and women with firm breasts (66.08% vs 31.27%).

TAKEAWAY:

- In total, 72 individuals (5.31%) in the conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy group and 7 (3.08%) in the minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy group developed postoperative complications of grade IIIb or higher.

- The rate of complications between the conventional and minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy groups in the short term (34.29% for conventional vs 32.16% for minimal access; P = .53) and long term (38.72% vs 32.16%, respectively; P = .06) was not significantly different.

- The conventional group experienced significantly fewer wound infections — both in the short term (1.62% vs 7.49%) and long term (4.28% vs 7.93%) — but a significantly higher rate of seroma (14.23% vs 9.25%), likely because of the variations in surgical instruments used during the procedures.

- Necrosis of the nipple or areola occurred more often in the minimal access group in the short term (8.81% vs 3.91%) but occurred more frequently in the conventional group in the long term (6.71% vs 2.20%).

IN PRACTICE:

“The similar complication rates suggest that both C-NSM [conventional nipple-sparing mastectomy] and M-NSM [minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy] may be equally safe options,” the authors wrote. “Therefore, the choice of surgical approach should be tailored to patient preferences and individual needs.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Joo Heung Kim, MD, Yongin Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Yongin, South Korea, was published online on August 14, 2024, in JAMA Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective design comes with inherent biases. The nonrandom assignment of the participants to the two groups and the relatively small number of cases of minimal access nipple-sparing mastectomy may have affected the findings. The involvement of different surgeons and use of early robotic surgery techniques may have introduced bias as well.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by Yonsei University College of Medicine and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Two authors reported receiving grants and consulting fees outside of this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Reform School’ for Pharmacy Benefit Managers: How Might Legislation Help Patients?

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

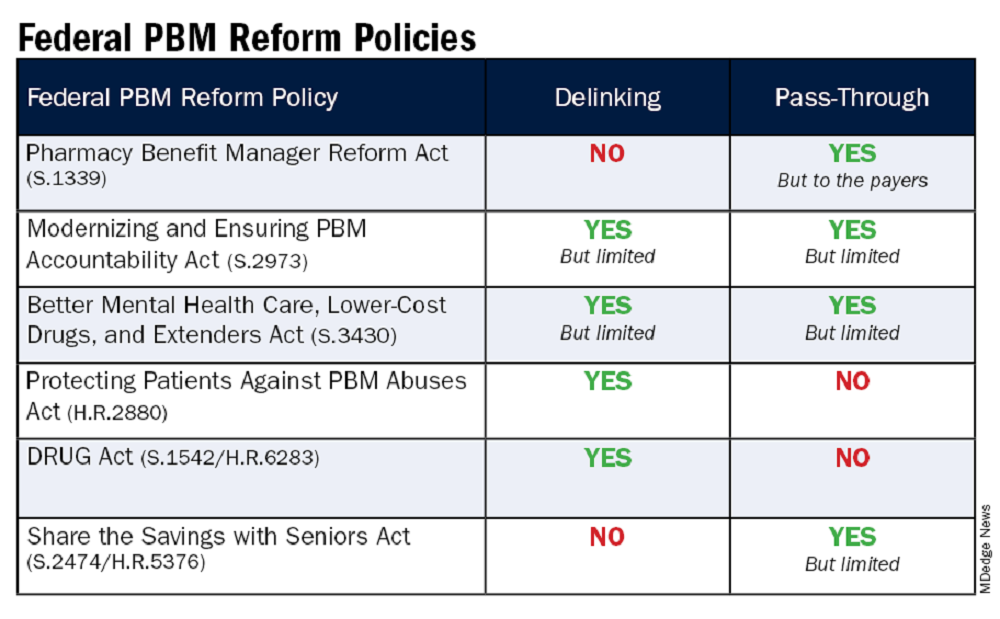

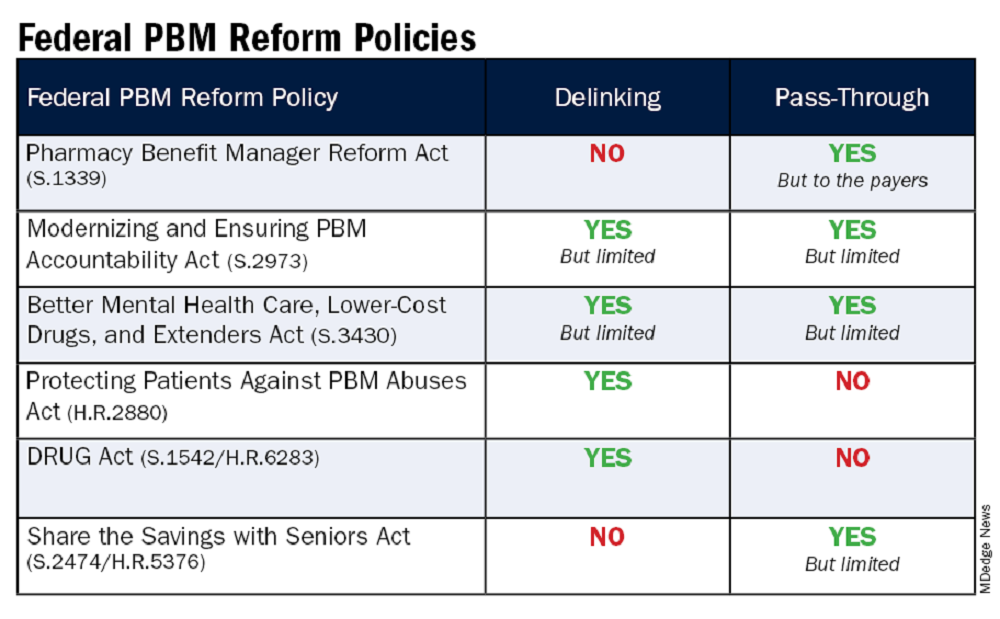

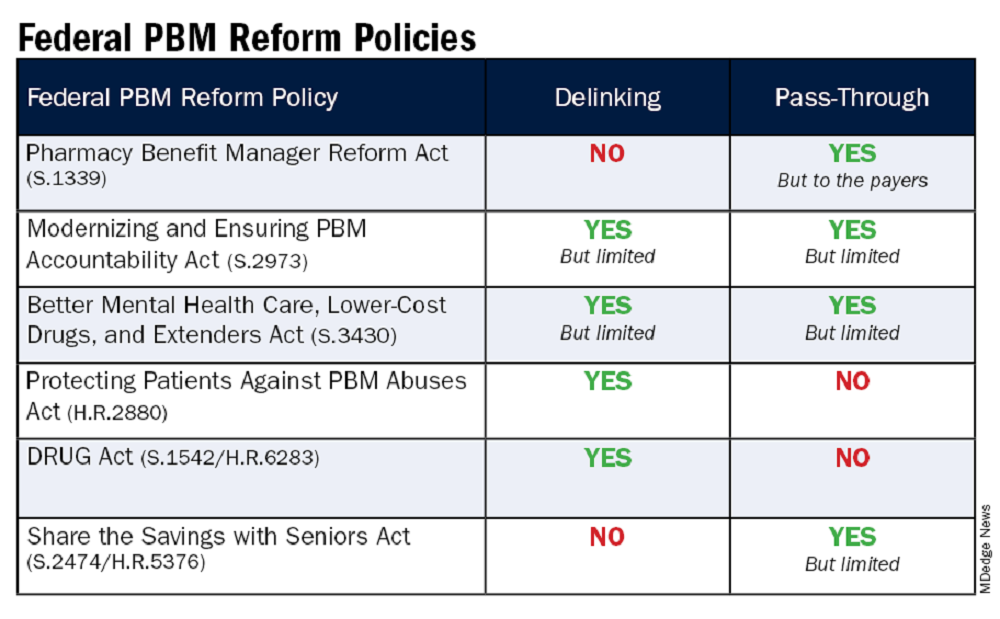

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

Beyond Weight Loss, Limited Bariatric Surgery Benefits in Older Adults

TOPLINE:

For older adults with obesity, bariatric surgery does not appear to significantly reduce the risk for obesity-related cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD), as it does in younger adults.

METHODOLOGY:

- Bariatric surgery has been shown to decrease the risk for obesity-related cancer and CVD but is typically reserved for patients aged < 60 years. Whether the same holds for patients who undergo surgery at older ages is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed nationwide data from three countries (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) to compare patients with no history of cancer or CVD and age ≥ 60 years who underwent bariatric surgery against matched controls who received nonoperative treatment for obesity.

- The main outcome was obesity-related cancer, defined as a composite outcome of breast, endometrial, esophageal, colorectal, and kidney cancer. The secondary outcome was CVD, defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage.

- Analyses were adjusted for diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, and frailty.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 15,300 patients (66.4% women) included, 2550 underwent bariatric surgery (including gastric bypass in 1930) and 12,750 matched controls received nonoperative treatment for obesity.

- During a median 5.8 years of follow-up, 658 (4.3%) people developed obesity-related cancer and 1436 (9.4%) developed CVD.

- Bariatric surgery in adults aged ≥ 60 years was not associated with a reduced risk for obesity-related cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81) or CVD (HR, 0.86) compared with matched nonoperative controls.

- Bariatric surgery appeared to be associated with a decreased risk for obesity-related cancer in women (HR, 0.76).

- There was a decreased risk for both obesity-related cancer (HR, 0.74) and CVD (HR, 0.82) in patients who underwent gastric bypass.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings from this study suggest a limited role of bariatric surgery in older patients for the prevention of obesity-related cancer or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote, noting that this “may be explained by the poorer weight loss and resolution of comorbidities observed in patients who underwent surgery at an older age.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Peter Gerber, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Capio St Göran’s Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data on smoking status and body mass index were not available. The observational design limited the ability to draw causal inferences. The null association between bariatric surgery and outcomes may be due to limited power.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the Swedish Society of Medicine. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

For older adults with obesity, bariatric surgery does not appear to significantly reduce the risk for obesity-related cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD), as it does in younger adults.

METHODOLOGY:

- Bariatric surgery has been shown to decrease the risk for obesity-related cancer and CVD but is typically reserved for patients aged < 60 years. Whether the same holds for patients who undergo surgery at older ages is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed nationwide data from three countries (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) to compare patients with no history of cancer or CVD and age ≥ 60 years who underwent bariatric surgery against matched controls who received nonoperative treatment for obesity.

- The main outcome was obesity-related cancer, defined as a composite outcome of breast, endometrial, esophageal, colorectal, and kidney cancer. The secondary outcome was CVD, defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage.

- Analyses were adjusted for diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, and frailty.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 15,300 patients (66.4% women) included, 2550 underwent bariatric surgery (including gastric bypass in 1930) and 12,750 matched controls received nonoperative treatment for obesity.

- During a median 5.8 years of follow-up, 658 (4.3%) people developed obesity-related cancer and 1436 (9.4%) developed CVD.

- Bariatric surgery in adults aged ≥ 60 years was not associated with a reduced risk for obesity-related cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81) or CVD (HR, 0.86) compared with matched nonoperative controls.

- Bariatric surgery appeared to be associated with a decreased risk for obesity-related cancer in women (HR, 0.76).

- There was a decreased risk for both obesity-related cancer (HR, 0.74) and CVD (HR, 0.82) in patients who underwent gastric bypass.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings from this study suggest a limited role of bariatric surgery in older patients for the prevention of obesity-related cancer or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote, noting that this “may be explained by the poorer weight loss and resolution of comorbidities observed in patients who underwent surgery at an older age.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Peter Gerber, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Capio St Göran’s Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data on smoking status and body mass index were not available. The observational design limited the ability to draw causal inferences. The null association between bariatric surgery and outcomes may be due to limited power.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the Swedish Society of Medicine. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

For older adults with obesity, bariatric surgery does not appear to significantly reduce the risk for obesity-related cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD), as it does in younger adults.

METHODOLOGY:

- Bariatric surgery has been shown to decrease the risk for obesity-related cancer and CVD but is typically reserved for patients aged < 60 years. Whether the same holds for patients who undergo surgery at older ages is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed nationwide data from three countries (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) to compare patients with no history of cancer or CVD and age ≥ 60 years who underwent bariatric surgery against matched controls who received nonoperative treatment for obesity.

- The main outcome was obesity-related cancer, defined as a composite outcome of breast, endometrial, esophageal, colorectal, and kidney cancer. The secondary outcome was CVD, defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage.

- Analyses were adjusted for diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, and frailty.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 15,300 patients (66.4% women) included, 2550 underwent bariatric surgery (including gastric bypass in 1930) and 12,750 matched controls received nonoperative treatment for obesity.

- During a median 5.8 years of follow-up, 658 (4.3%) people developed obesity-related cancer and 1436 (9.4%) developed CVD.

- Bariatric surgery in adults aged ≥ 60 years was not associated with a reduced risk for obesity-related cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81) or CVD (HR, 0.86) compared with matched nonoperative controls.

- Bariatric surgery appeared to be associated with a decreased risk for obesity-related cancer in women (HR, 0.76).

- There was a decreased risk for both obesity-related cancer (HR, 0.74) and CVD (HR, 0.82) in patients who underwent gastric bypass.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings from this study suggest a limited role of bariatric surgery in older patients for the prevention of obesity-related cancer or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote, noting that this “may be explained by the poorer weight loss and resolution of comorbidities observed in patients who underwent surgery at an older age.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Peter Gerber, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Capio St Göran’s Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data on smoking status and body mass index were not available. The observational design limited the ability to draw causal inferences. The null association between bariatric surgery and outcomes may be due to limited power.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the Swedish Society of Medicine. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Silent Exodus: Are Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Quiet Quitting?

While she cared deeply about her work, Melissa Adams*, a family nurse practitioner (NP) in Madison, Alabama, was being frequently triple-booked, didn’t feel respected by her office manager, and started to worry about becoming burned out. When she sought help, “the administration was tone-deaf,” she said. “When I asked about what I could do to prevent burnout, they sent me an article about it. It was clear to me that asking for respite from triple-booking and asking to be respected by my office manager wasn’t being heard ... so I thought, ‘how do I fly under the radar and get by with what I can?’ ” That meant focusing on patient care and refusing to take on additional responsibilities, like training new hires or working with students.

“You’re overworked and underpaid, and you start giving less and less of yourself,” Ms. Adams said in an interview.

Quiet quitting, defined as performing only the assigned tasks of the job without making any extra effort or going the proverbial extra mile, has gained attention in the press in recent years. A Gallup poll found that about 50% of the workforce were “quiet quitters” or disengaged.

It may be even more prevalent in healthcare, where a recent survey found that 57% of frontline medical staff, including NPs and physician assistants (PAs), report being disengaged at work.

The Causes of Quiet Quitting

Potential causes of quiet quitting among PAs and NPs include:

- Unrealistic care expectations. Ms. Adams said.

- Lack of trust or respect. Physicians don’t always respect the role that PAs and NPs play in a practice.

- Dissatisfaction with leadership or administration. There’s often a feeling that the PA or NP isn’t “heard” or appreciated.

- Dissatisfaction with pay or working conditions.

- Moral injury. “There’s no way to escape being morally injured when you work with an at-risk population,” said Ms. Adams. “You may see someone who has 20-24 determinants of health, and you’re expected to schlep them through in 8 minutes — you know you’re not able to do what they need.”

What Quiet Quitting Looks Like

Terri Smith*, an NP at an academic medical center outpatient clinic in rural Vermont, said that, while she feels appreciated by her patients and her team, there’s poor communication from the administration, which has caused her to quietly quit.

“I stopped saying ‘yes’ to all the normal committee work and the extra stuff that used to add a lot to my professional enjoyment,” she said. “The last couple of years, my whole motto is to nod and smile when administration says to do something — to put your head down and take care of your patients.”

While the term “quiet quitting” may be new, the issue is not, said Bridget Roberts, PhD, a healthcare executive who ran a large physician’s group of 100 healthcare providers in Jacksonville, Florida, for a decade. “Quiet quitting is a fancy title for employees who are completely disengaged,” said Dr. Roberts. “When they’re on the way out, they ‘check the box’. That’s not a new thing.”

“Typically, the first thing you see is a lot of frustration in that they aren’t able to complete the tasks they have at hand,” said Rebecca Day, PMNHP, a doctoral-educated NP and director of nursing practice at a Federally Qualified Health Center in Corbin, Kentucky. “Staff may be overworked and not have enough time to do what’s required of them with patient care as well as the paperwork required behind the scenes. It [quiet quitting] is doing just enough to get by, but shortcutting as much as they can to try to save some time.”

Addressing Quiet Quitting

Those kinds of shortcuts may affect patients, admits Ms. Smith. “I do think it starts to seep into patient care,” she said. “And that really doesn’t feel good ... at our institution, I’m not just an NP — I’m the nurse, the doctor, the secretary — I’m everybody, and for the last year, almost every single day in clinic, I’m apologizing [to a patient] because we can’t do something.”

Watching for this frustration can help alert administrators to NPs and PAs who may be “checking out” at work. Open lines of communication can help you address the issue. “Ask questions like ‘What could we do differently to make your day easier?’” said Dr. Roberts. Understanding the day-to-day issues NPs and PAs face at work can help in developing a plan to address disengagement.

When Dr. Day sees quiet quitting at her practice, she talks with the advance practice provider about what’s causing the issue. “’Are you overworked? Are you understaffed? Are there problems at home? Do you feel you’re receiving inadequate pay?’ ” she said. “The first thing to do is address that and find mutual ground on the issues…deal with the person as a person and then go back and deal with the person as an employee. If your staff isn’t happy, your clinic isn’t going to be productive.”

Finally, while reasons for quiet quitting may vary, cultivating a collaborative atmosphere where NPs and PAs feel appreciated and valued can help reduce the risk for quiet quitting. “Get to know your advanced practice providers,” said Ms. Adams. “Understand their strengths and what they’re about. It’s not an ‘us vs them’ ... there is a lot more commonality when we approach it that way.” Respect for the integral role that NPs and PAs play in your practice can help reduce the risk for quiet quitting — and help provide better patient care.

*Names have been changed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While she cared deeply about her work, Melissa Adams*, a family nurse practitioner (NP) in Madison, Alabama, was being frequently triple-booked, didn’t feel respected by her office manager, and started to worry about becoming burned out. When she sought help, “the administration was tone-deaf,” she said. “When I asked about what I could do to prevent burnout, they sent me an article about it. It was clear to me that asking for respite from triple-booking and asking to be respected by my office manager wasn’t being heard ... so I thought, ‘how do I fly under the radar and get by with what I can?’ ” That meant focusing on patient care and refusing to take on additional responsibilities, like training new hires or working with students.

“You’re overworked and underpaid, and you start giving less and less of yourself,” Ms. Adams said in an interview.

Quiet quitting, defined as performing only the assigned tasks of the job without making any extra effort or going the proverbial extra mile, has gained attention in the press in recent years. A Gallup poll found that about 50% of the workforce were “quiet quitters” or disengaged.