User login

Buprenorphine proves effective for fentanyl users in the ED

based on data from nearly 900 individuals.

California EDs include a facilitation program known as CA Bridge for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Guidelines for CA Bridge call for high-dose buprenorphine to treat patients in drug withdrawal, with doses starting at 8-16 mg, Hannah Snyder, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues wrote.

“Buprenorphine has been repeatedly shown to save lives and prevent overdoses,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We know that emergency department–initiated buprenorphine is an essential tool for increasing access. In the era of fentanyl, both patients and providers have expressed concerns that buprenorphine may not work as well as it did when patients were more likely to be using heroin or opioid pills.

“This retrospective cohort study provides additional information about emergency department buprenorphine as fentanyl becomes increasingly prevalent.”

In a research letter published in JAMA Network Open, the investigators reviewed data from the electronic health records of 896 patients who presented with opioid use disorder (OUD) at 16 CA Bridge EDs between Jan. 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020. All patients with OUD were included regardless of chief concern, current treatment, treatment desires, or withdrawal. A total of 87 individuals reported fentanyl use; if no fentanyl use was reported, the patient was classified as not using fentanyl. The median age of the patients was 35 years, two thirds were male, approximately 46% were White and non-Hispanic, and 30% had unstable housing.

The primary outcome was follow-up engagement at 7-14 days and 25-37 days.

A total of 492 patients received buprenorphine, including 44 fentanyl users, and 439 initiated high doses of 8-32 mg. At a 30-day follow-up, eight patients had precipitated withdrawal, including two cases in fentanyl users; none of these cases required hospital admission.

The follow-up engagement was similar for both groups, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.60 for administered buprenorphine at the initial ED encounter, 1.09 for 7-day follow-up, and 1.33 for 30-day follow-up.

The findings were limited by the retrospective design and use of clinical documentation, which likely resulted in underreporting of fentanyl use and follow-up, the researchers noted. However, the results supported the effectiveness of buprenorphine for ED patients in withdrawal with a history of fentanyl exposure.

“We were pleased to see that precipitated withdrawal was relatively uncommon in this study, and that patients who did and did not use fentanyl followed up at similar rates,” said Dr. Snyder. “This aligns with our clinical experience and prior research showing that emergency department buprenorphine starts continue to be an essential tool.”

The message for clinicians: “If a patient presents to the emergency department in objective opioid withdrawal and desires buprenorphine, they should be offered treatment in that moment,” Dr. Snyder said. “Treatment protocols used by hospitals in this study are available online. Emergency departments can offer compassionate and evidence-based treatment initiation 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year.”

More data needed on dosing strategies

“We need additional research to determine best practices for patients who use fentanyl and want to start buprenorphine, but are not yet in withdrawal,” Dr. Snyder said. “Doses of buprenorphine like those in this study are only appropriate for patients who are in withdrawal with objective signs, so some patients may struggle to wait long enough after their last use to go into sufficient withdrawal.”

Precipitated withdrawal does occur in some cases, said Dr. Snyder. “If it does, the emergency department is a very good place to manage it. We need additional research to determine best practices in management to make patients as comfortable as possible, including additional high-dose buprenorphine as well as additional adjunctive agents.”

Findings support buprenorphine

“The classic approach to buprenorphine initiation, which emerged from psychiatry outpatient office visits, is to start with very small doses of buprenorphine [2-4 mg] and titrate up slowly,” Reuben J. Strayer, MD, said in an interview.

“This dose range turns out to be the ‘sour spot’ most likely to cause the most important complication around buprenorphine initiation–precipitated withdrawal,” said Dr. Strayer, the director of addiction medicine in the emergency medicine department at Maimonides Medical Center, New York.

“One of the current focus areas of OUD treatment research is determining how to initiate buprenorphine without entailing a period of spontaneous withdrawal and without causing precipitated withdrawal,” Strayer explained. “The two primary strategies are low-dose buprenorphine initiation [LDBI, less than 2 mg, sometimes called microdosing] and high-dose [HDBI, ≥ 16 mg] buprenorphine initiation. HDBI is attractive because the primary treatment of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal is more buprenorphine.

“Additionally, using a high dose up front immediately transitions the patient to therapeutic blood levels, which protects the patient from withdrawal, cravings, and overdose from dangerous opioids (heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone).”

However, “the contamination and now replacement of heroin with fentanyl in the street drug supply has challenged buprenorphine initiation, because fentanyl, when used chronically, accumulates in the body and leaks into the bloodstream slowly over time, preventing the opioid washout that is required to eliminate the risk of precipitated withdrawal when buprenorphine is administered,” said Dr. Strayer.

The current study demonstrates that patients who are initiated with a first dose of 8-16 mg buprenorphine are unlikely to experience precipitated withdrawal and are successfully transitioned to buprenorphine maintenance and clinic follow-up, Dr. Snyder said, but he was surprised by the low rate of precipitated withdrawal in the current study, “which is discordant with what is being anecdotally reported across the country.”

However, the take-home message for clinicians is the support for the initiation of buprenorphine in emergency department settings at a starting dose of 8-16 mg, regardless of reported fentanyl use, he said. “Given the huge impact buprenorphine therapy has on OUD-related mortality, clinicians should make every effort to initiate buprenorphine for OUD patients at every opportunity, and precipitated withdrawal is very unlikely in appropriately selected patients.

“Many clinicians remain reluctant to initiate buprenorphine in ED settings for unfamiliarity with the drug, fear of precipitated withdrawal, or concerns around the certainty of outpatient follow-up,” Dr. Snyder said. “Education, encouragement, systems programming, such as including decision support within the electronic health record, and role-modeling from local champions will promote wider adoption of this lifesaving practice.”

Looking ahead, “more research, including prospective research, is needed to refine best practices around buprenorphine administration,” said Dr. Snyder. Questions to address include which patients are most at risk for precipitated withdrawal and whether there are alternatives to standard initiation dosing that are sufficiently unlikely to cause precipitated withdrawal. “Possibly effective alternatives include buprenorphine initiation by administration of long-acting injectable depot buprenorphine, which accumulates slowly, potentially avoiding precipitated withdrawal, as well as a slow intravenous buprenorphine infusion such as 9 mg given over 12 hours.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Snyder disclosed grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the California Department of Health Care Services during the study. Dr. Strayer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

based on data from nearly 900 individuals.

California EDs include a facilitation program known as CA Bridge for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Guidelines for CA Bridge call for high-dose buprenorphine to treat patients in drug withdrawal, with doses starting at 8-16 mg, Hannah Snyder, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues wrote.

“Buprenorphine has been repeatedly shown to save lives and prevent overdoses,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We know that emergency department–initiated buprenorphine is an essential tool for increasing access. In the era of fentanyl, both patients and providers have expressed concerns that buprenorphine may not work as well as it did when patients were more likely to be using heroin or opioid pills.

“This retrospective cohort study provides additional information about emergency department buprenorphine as fentanyl becomes increasingly prevalent.”

In a research letter published in JAMA Network Open, the investigators reviewed data from the electronic health records of 896 patients who presented with opioid use disorder (OUD) at 16 CA Bridge EDs between Jan. 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020. All patients with OUD were included regardless of chief concern, current treatment, treatment desires, or withdrawal. A total of 87 individuals reported fentanyl use; if no fentanyl use was reported, the patient was classified as not using fentanyl. The median age of the patients was 35 years, two thirds were male, approximately 46% were White and non-Hispanic, and 30% had unstable housing.

The primary outcome was follow-up engagement at 7-14 days and 25-37 days.

A total of 492 patients received buprenorphine, including 44 fentanyl users, and 439 initiated high doses of 8-32 mg. At a 30-day follow-up, eight patients had precipitated withdrawal, including two cases in fentanyl users; none of these cases required hospital admission.

The follow-up engagement was similar for both groups, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.60 for administered buprenorphine at the initial ED encounter, 1.09 for 7-day follow-up, and 1.33 for 30-day follow-up.

The findings were limited by the retrospective design and use of clinical documentation, which likely resulted in underreporting of fentanyl use and follow-up, the researchers noted. However, the results supported the effectiveness of buprenorphine for ED patients in withdrawal with a history of fentanyl exposure.

“We were pleased to see that precipitated withdrawal was relatively uncommon in this study, and that patients who did and did not use fentanyl followed up at similar rates,” said Dr. Snyder. “This aligns with our clinical experience and prior research showing that emergency department buprenorphine starts continue to be an essential tool.”

The message for clinicians: “If a patient presents to the emergency department in objective opioid withdrawal and desires buprenorphine, they should be offered treatment in that moment,” Dr. Snyder said. “Treatment protocols used by hospitals in this study are available online. Emergency departments can offer compassionate and evidence-based treatment initiation 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year.”

More data needed on dosing strategies

“We need additional research to determine best practices for patients who use fentanyl and want to start buprenorphine, but are not yet in withdrawal,” Dr. Snyder said. “Doses of buprenorphine like those in this study are only appropriate for patients who are in withdrawal with objective signs, so some patients may struggle to wait long enough after their last use to go into sufficient withdrawal.”

Precipitated withdrawal does occur in some cases, said Dr. Snyder. “If it does, the emergency department is a very good place to manage it. We need additional research to determine best practices in management to make patients as comfortable as possible, including additional high-dose buprenorphine as well as additional adjunctive agents.”

Findings support buprenorphine

“The classic approach to buprenorphine initiation, which emerged from psychiatry outpatient office visits, is to start with very small doses of buprenorphine [2-4 mg] and titrate up slowly,” Reuben J. Strayer, MD, said in an interview.

“This dose range turns out to be the ‘sour spot’ most likely to cause the most important complication around buprenorphine initiation–precipitated withdrawal,” said Dr. Strayer, the director of addiction medicine in the emergency medicine department at Maimonides Medical Center, New York.

“One of the current focus areas of OUD treatment research is determining how to initiate buprenorphine without entailing a period of spontaneous withdrawal and without causing precipitated withdrawal,” Strayer explained. “The two primary strategies are low-dose buprenorphine initiation [LDBI, less than 2 mg, sometimes called microdosing] and high-dose [HDBI, ≥ 16 mg] buprenorphine initiation. HDBI is attractive because the primary treatment of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal is more buprenorphine.

“Additionally, using a high dose up front immediately transitions the patient to therapeutic blood levels, which protects the patient from withdrawal, cravings, and overdose from dangerous opioids (heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone).”

However, “the contamination and now replacement of heroin with fentanyl in the street drug supply has challenged buprenorphine initiation, because fentanyl, when used chronically, accumulates in the body and leaks into the bloodstream slowly over time, preventing the opioid washout that is required to eliminate the risk of precipitated withdrawal when buprenorphine is administered,” said Dr. Strayer.

The current study demonstrates that patients who are initiated with a first dose of 8-16 mg buprenorphine are unlikely to experience precipitated withdrawal and are successfully transitioned to buprenorphine maintenance and clinic follow-up, Dr. Snyder said, but he was surprised by the low rate of precipitated withdrawal in the current study, “which is discordant with what is being anecdotally reported across the country.”

However, the take-home message for clinicians is the support for the initiation of buprenorphine in emergency department settings at a starting dose of 8-16 mg, regardless of reported fentanyl use, he said. “Given the huge impact buprenorphine therapy has on OUD-related mortality, clinicians should make every effort to initiate buprenorphine for OUD patients at every opportunity, and precipitated withdrawal is very unlikely in appropriately selected patients.

“Many clinicians remain reluctant to initiate buprenorphine in ED settings for unfamiliarity with the drug, fear of precipitated withdrawal, or concerns around the certainty of outpatient follow-up,” Dr. Snyder said. “Education, encouragement, systems programming, such as including decision support within the electronic health record, and role-modeling from local champions will promote wider adoption of this lifesaving practice.”

Looking ahead, “more research, including prospective research, is needed to refine best practices around buprenorphine administration,” said Dr. Snyder. Questions to address include which patients are most at risk for precipitated withdrawal and whether there are alternatives to standard initiation dosing that are sufficiently unlikely to cause precipitated withdrawal. “Possibly effective alternatives include buprenorphine initiation by administration of long-acting injectable depot buprenorphine, which accumulates slowly, potentially avoiding precipitated withdrawal, as well as a slow intravenous buprenorphine infusion such as 9 mg given over 12 hours.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Snyder disclosed grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the California Department of Health Care Services during the study. Dr. Strayer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

based on data from nearly 900 individuals.

California EDs include a facilitation program known as CA Bridge for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Guidelines for CA Bridge call for high-dose buprenorphine to treat patients in drug withdrawal, with doses starting at 8-16 mg, Hannah Snyder, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues wrote.

“Buprenorphine has been repeatedly shown to save lives and prevent overdoses,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We know that emergency department–initiated buprenorphine is an essential tool for increasing access. In the era of fentanyl, both patients and providers have expressed concerns that buprenorphine may not work as well as it did when patients were more likely to be using heroin or opioid pills.

“This retrospective cohort study provides additional information about emergency department buprenorphine as fentanyl becomes increasingly prevalent.”

In a research letter published in JAMA Network Open, the investigators reviewed data from the electronic health records of 896 patients who presented with opioid use disorder (OUD) at 16 CA Bridge EDs between Jan. 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020. All patients with OUD were included regardless of chief concern, current treatment, treatment desires, or withdrawal. A total of 87 individuals reported fentanyl use; if no fentanyl use was reported, the patient was classified as not using fentanyl. The median age of the patients was 35 years, two thirds were male, approximately 46% were White and non-Hispanic, and 30% had unstable housing.

The primary outcome was follow-up engagement at 7-14 days and 25-37 days.

A total of 492 patients received buprenorphine, including 44 fentanyl users, and 439 initiated high doses of 8-32 mg. At a 30-day follow-up, eight patients had precipitated withdrawal, including two cases in fentanyl users; none of these cases required hospital admission.

The follow-up engagement was similar for both groups, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.60 for administered buprenorphine at the initial ED encounter, 1.09 for 7-day follow-up, and 1.33 for 30-day follow-up.

The findings were limited by the retrospective design and use of clinical documentation, which likely resulted in underreporting of fentanyl use and follow-up, the researchers noted. However, the results supported the effectiveness of buprenorphine for ED patients in withdrawal with a history of fentanyl exposure.

“We were pleased to see that precipitated withdrawal was relatively uncommon in this study, and that patients who did and did not use fentanyl followed up at similar rates,” said Dr. Snyder. “This aligns with our clinical experience and prior research showing that emergency department buprenorphine starts continue to be an essential tool.”

The message for clinicians: “If a patient presents to the emergency department in objective opioid withdrawal and desires buprenorphine, they should be offered treatment in that moment,” Dr. Snyder said. “Treatment protocols used by hospitals in this study are available online. Emergency departments can offer compassionate and evidence-based treatment initiation 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year.”

More data needed on dosing strategies

“We need additional research to determine best practices for patients who use fentanyl and want to start buprenorphine, but are not yet in withdrawal,” Dr. Snyder said. “Doses of buprenorphine like those in this study are only appropriate for patients who are in withdrawal with objective signs, so some patients may struggle to wait long enough after their last use to go into sufficient withdrawal.”

Precipitated withdrawal does occur in some cases, said Dr. Snyder. “If it does, the emergency department is a very good place to manage it. We need additional research to determine best practices in management to make patients as comfortable as possible, including additional high-dose buprenorphine as well as additional adjunctive agents.”

Findings support buprenorphine

“The classic approach to buprenorphine initiation, which emerged from psychiatry outpatient office visits, is to start with very small doses of buprenorphine [2-4 mg] and titrate up slowly,” Reuben J. Strayer, MD, said in an interview.

“This dose range turns out to be the ‘sour spot’ most likely to cause the most important complication around buprenorphine initiation–precipitated withdrawal,” said Dr. Strayer, the director of addiction medicine in the emergency medicine department at Maimonides Medical Center, New York.

“One of the current focus areas of OUD treatment research is determining how to initiate buprenorphine without entailing a period of spontaneous withdrawal and without causing precipitated withdrawal,” Strayer explained. “The two primary strategies are low-dose buprenorphine initiation [LDBI, less than 2 mg, sometimes called microdosing] and high-dose [HDBI, ≥ 16 mg] buprenorphine initiation. HDBI is attractive because the primary treatment of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal is more buprenorphine.

“Additionally, using a high dose up front immediately transitions the patient to therapeutic blood levels, which protects the patient from withdrawal, cravings, and overdose from dangerous opioids (heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone).”

However, “the contamination and now replacement of heroin with fentanyl in the street drug supply has challenged buprenorphine initiation, because fentanyl, when used chronically, accumulates in the body and leaks into the bloodstream slowly over time, preventing the opioid washout that is required to eliminate the risk of precipitated withdrawal when buprenorphine is administered,” said Dr. Strayer.

The current study demonstrates that patients who are initiated with a first dose of 8-16 mg buprenorphine are unlikely to experience precipitated withdrawal and are successfully transitioned to buprenorphine maintenance and clinic follow-up, Dr. Snyder said, but he was surprised by the low rate of precipitated withdrawal in the current study, “which is discordant with what is being anecdotally reported across the country.”

However, the take-home message for clinicians is the support for the initiation of buprenorphine in emergency department settings at a starting dose of 8-16 mg, regardless of reported fentanyl use, he said. “Given the huge impact buprenorphine therapy has on OUD-related mortality, clinicians should make every effort to initiate buprenorphine for OUD patients at every opportunity, and precipitated withdrawal is very unlikely in appropriately selected patients.

“Many clinicians remain reluctant to initiate buprenorphine in ED settings for unfamiliarity with the drug, fear of precipitated withdrawal, or concerns around the certainty of outpatient follow-up,” Dr. Snyder said. “Education, encouragement, systems programming, such as including decision support within the electronic health record, and role-modeling from local champions will promote wider adoption of this lifesaving practice.”

Looking ahead, “more research, including prospective research, is needed to refine best practices around buprenorphine administration,” said Dr. Snyder. Questions to address include which patients are most at risk for precipitated withdrawal and whether there are alternatives to standard initiation dosing that are sufficiently unlikely to cause precipitated withdrawal. “Possibly effective alternatives include buprenorphine initiation by administration of long-acting injectable depot buprenorphine, which accumulates slowly, potentially avoiding precipitated withdrawal, as well as a slow intravenous buprenorphine infusion such as 9 mg given over 12 hours.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Snyder disclosed grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the California Department of Health Care Services during the study. Dr. Strayer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

The SHOW UP Act Threatens VA Telehealth

In February, the US House of Representatives hurriedly passed the Stopping Home Office Work’s Unproductive Problems (SHOW UP) Act, H.R. 139, a bill that calls into question the contributions of federal employees allowed to work from home and resets telework policies to those in place in 2019. Its author, House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer (R, Kentucky) claimed that this change was necessary because the expansion of federal telework during the COVID-19 pandemic “has crippled the ability of agencies to get their jobs done and created backlogs.” His targets included the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), where, he charged, “veterans have been unable…to obtain care they have earned.” He added, “it’s hard to argue that teleworking has helped the VA.”

While oversight of government programs is an authority of Congress, the SHOW UP Act is based on unsubstantiated assumptions of dereliction. It also disregards the devastating impact the proposed changes will have on veterans’ ability to receive care and inaccurately implies improving it. As the Senate considers the bill, they should take heed of these and other facts involving this often misunderstood form of labor.

COVID-19 irrevocably transformed the use of virtual care within the VA and across the world. Even as the pandemic subsides, public and private health care systems have continued to use telework-centered telehealth far above prepandemic levels, especially for mental health and primary care. Employers, including the VA, capitalize on telework for its benefits to both consumers and the workforce. For consumers, research supports the clinical effectiveness of telemental health service, as well as its cost-effectiveness and consumer satisfaction. On the workforce side, research has documented heightened productivity, lower distractibility, and higher job satisfaction among counselors who shifted to remote work.

Remote work also serves as a key tool in attracting and retaining a qualified workforce. As one VA service chief explained, “I am having enough trouble competing with the private sector, where extensive telework is now the norm. If telework options were rolled back, the private sector will have a field day picking off my best staff.” These comments are consistent with the data. McKinsey’s American Opportunity Survey shows that Americans have embraced remote work and want more of it. Recent data from Gallup show that 6 of 10 currently exclusively remote employees would be extremely likely to change companies if they lost their remote flexibility. Further, Gallup data show that when an employee’s location preference does not match their current work location, burnout rises, and engagement drops.

Between 2019 and 2023, the VA’s telework expansion is what has enabled it to meet the growing demand for mental health services. VA is keeping pace by having 2 or more clinicians rotate between home and a shared VA office. Forcing these hybrid practitioners to work full time at VA facilities would drastically reduce the number of patients they can care for. There simply are not enough offices on crammed VA grounds to house staff who telework today. The net result would be that fewer appointments would be available, creating longer wait times. And that is just for existing patients. It does not factor in the expected influx due to new veteran eligibility made possible by the toxic exposures PACT Act.

Here is another good example of crucial VA telework: With the advent of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, VA is adding more than 1000 new Veterans Crisis Line responders. All these new positions are remote. The SHOW UP Act would inhibit this expansion of lifesaving programs.

Veterans want more, not fewer, telehealth options. At a House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs hearing this past September, the VA reported that most veterans would prefer to receive mental health services virtually than to have to commute to a VA medical center or clinic. Telehealth benefits veterans in meaningful ways, including that it reduces their travel time, travel expense, depletion of sick leave, and need for childcare. Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, military sexual trauma, those with mobility issues, or those who struggle with the stigma of mental health treatment may prefer the familiarity of their own homes for care. Virtual options also relieve a patient’s need to enter a hospital and be unnecessarily exposed to contagious viruses. That’s safer not only for veterans but also for VA staff.

Finally, virtual care improves treatment. Research has revealed that the likelihood of missing telehealth appointments is lower than for in-person appointments. When patients miss appointments, continuity of care is disrupted, and health care outcomes are diminished.

The pandemic is receding, but the advantages of telework-centered virtual care are greater than ever. Political representatives who want to show up for veterans should do everything in their power to expand—not cut—VA’s ability to authorize working from home.

In February, the US House of Representatives hurriedly passed the Stopping Home Office Work’s Unproductive Problems (SHOW UP) Act, H.R. 139, a bill that calls into question the contributions of federal employees allowed to work from home and resets telework policies to those in place in 2019. Its author, House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer (R, Kentucky) claimed that this change was necessary because the expansion of federal telework during the COVID-19 pandemic “has crippled the ability of agencies to get their jobs done and created backlogs.” His targets included the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), where, he charged, “veterans have been unable…to obtain care they have earned.” He added, “it’s hard to argue that teleworking has helped the VA.”

While oversight of government programs is an authority of Congress, the SHOW UP Act is based on unsubstantiated assumptions of dereliction. It also disregards the devastating impact the proposed changes will have on veterans’ ability to receive care and inaccurately implies improving it. As the Senate considers the bill, they should take heed of these and other facts involving this often misunderstood form of labor.

COVID-19 irrevocably transformed the use of virtual care within the VA and across the world. Even as the pandemic subsides, public and private health care systems have continued to use telework-centered telehealth far above prepandemic levels, especially for mental health and primary care. Employers, including the VA, capitalize on telework for its benefits to both consumers and the workforce. For consumers, research supports the clinical effectiveness of telemental health service, as well as its cost-effectiveness and consumer satisfaction. On the workforce side, research has documented heightened productivity, lower distractibility, and higher job satisfaction among counselors who shifted to remote work.

Remote work also serves as a key tool in attracting and retaining a qualified workforce. As one VA service chief explained, “I am having enough trouble competing with the private sector, where extensive telework is now the norm. If telework options were rolled back, the private sector will have a field day picking off my best staff.” These comments are consistent with the data. McKinsey’s American Opportunity Survey shows that Americans have embraced remote work and want more of it. Recent data from Gallup show that 6 of 10 currently exclusively remote employees would be extremely likely to change companies if they lost their remote flexibility. Further, Gallup data show that when an employee’s location preference does not match their current work location, burnout rises, and engagement drops.

Between 2019 and 2023, the VA’s telework expansion is what has enabled it to meet the growing demand for mental health services. VA is keeping pace by having 2 or more clinicians rotate between home and a shared VA office. Forcing these hybrid practitioners to work full time at VA facilities would drastically reduce the number of patients they can care for. There simply are not enough offices on crammed VA grounds to house staff who telework today. The net result would be that fewer appointments would be available, creating longer wait times. And that is just for existing patients. It does not factor in the expected influx due to new veteran eligibility made possible by the toxic exposures PACT Act.

Here is another good example of crucial VA telework: With the advent of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, VA is adding more than 1000 new Veterans Crisis Line responders. All these new positions are remote. The SHOW UP Act would inhibit this expansion of lifesaving programs.

Veterans want more, not fewer, telehealth options. At a House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs hearing this past September, the VA reported that most veterans would prefer to receive mental health services virtually than to have to commute to a VA medical center or clinic. Telehealth benefits veterans in meaningful ways, including that it reduces their travel time, travel expense, depletion of sick leave, and need for childcare. Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, military sexual trauma, those with mobility issues, or those who struggle with the stigma of mental health treatment may prefer the familiarity of their own homes for care. Virtual options also relieve a patient’s need to enter a hospital and be unnecessarily exposed to contagious viruses. That’s safer not only for veterans but also for VA staff.

Finally, virtual care improves treatment. Research has revealed that the likelihood of missing telehealth appointments is lower than for in-person appointments. When patients miss appointments, continuity of care is disrupted, and health care outcomes are diminished.

The pandemic is receding, but the advantages of telework-centered virtual care are greater than ever. Political representatives who want to show up for veterans should do everything in their power to expand—not cut—VA’s ability to authorize working from home.

In February, the US House of Representatives hurriedly passed the Stopping Home Office Work’s Unproductive Problems (SHOW UP) Act, H.R. 139, a bill that calls into question the contributions of federal employees allowed to work from home and resets telework policies to those in place in 2019. Its author, House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer (R, Kentucky) claimed that this change was necessary because the expansion of federal telework during the COVID-19 pandemic “has crippled the ability of agencies to get their jobs done and created backlogs.” His targets included the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), where, he charged, “veterans have been unable…to obtain care they have earned.” He added, “it’s hard to argue that teleworking has helped the VA.”

While oversight of government programs is an authority of Congress, the SHOW UP Act is based on unsubstantiated assumptions of dereliction. It also disregards the devastating impact the proposed changes will have on veterans’ ability to receive care and inaccurately implies improving it. As the Senate considers the bill, they should take heed of these and other facts involving this often misunderstood form of labor.

COVID-19 irrevocably transformed the use of virtual care within the VA and across the world. Even as the pandemic subsides, public and private health care systems have continued to use telework-centered telehealth far above prepandemic levels, especially for mental health and primary care. Employers, including the VA, capitalize on telework for its benefits to both consumers and the workforce. For consumers, research supports the clinical effectiveness of telemental health service, as well as its cost-effectiveness and consumer satisfaction. On the workforce side, research has documented heightened productivity, lower distractibility, and higher job satisfaction among counselors who shifted to remote work.

Remote work also serves as a key tool in attracting and retaining a qualified workforce. As one VA service chief explained, “I am having enough trouble competing with the private sector, where extensive telework is now the norm. If telework options were rolled back, the private sector will have a field day picking off my best staff.” These comments are consistent with the data. McKinsey’s American Opportunity Survey shows that Americans have embraced remote work and want more of it. Recent data from Gallup show that 6 of 10 currently exclusively remote employees would be extremely likely to change companies if they lost their remote flexibility. Further, Gallup data show that when an employee’s location preference does not match their current work location, burnout rises, and engagement drops.

Between 2019 and 2023, the VA’s telework expansion is what has enabled it to meet the growing demand for mental health services. VA is keeping pace by having 2 or more clinicians rotate between home and a shared VA office. Forcing these hybrid practitioners to work full time at VA facilities would drastically reduce the number of patients they can care for. There simply are not enough offices on crammed VA grounds to house staff who telework today. The net result would be that fewer appointments would be available, creating longer wait times. And that is just for existing patients. It does not factor in the expected influx due to new veteran eligibility made possible by the toxic exposures PACT Act.

Here is another good example of crucial VA telework: With the advent of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, VA is adding more than 1000 new Veterans Crisis Line responders. All these new positions are remote. The SHOW UP Act would inhibit this expansion of lifesaving programs.

Veterans want more, not fewer, telehealth options. At a House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs hearing this past September, the VA reported that most veterans would prefer to receive mental health services virtually than to have to commute to a VA medical center or clinic. Telehealth benefits veterans in meaningful ways, including that it reduces their travel time, travel expense, depletion of sick leave, and need for childcare. Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, military sexual trauma, those with mobility issues, or those who struggle with the stigma of mental health treatment may prefer the familiarity of their own homes for care. Virtual options also relieve a patient’s need to enter a hospital and be unnecessarily exposed to contagious viruses. That’s safer not only for veterans but also for VA staff.

Finally, virtual care improves treatment. Research has revealed that the likelihood of missing telehealth appointments is lower than for in-person appointments. When patients miss appointments, continuity of care is disrupted, and health care outcomes are diminished.

The pandemic is receding, but the advantages of telework-centered virtual care are greater than ever. Political representatives who want to show up for veterans should do everything in their power to expand—not cut—VA’s ability to authorize working from home.

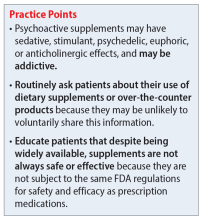

Psychoactive supplements: What to tell patients

Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

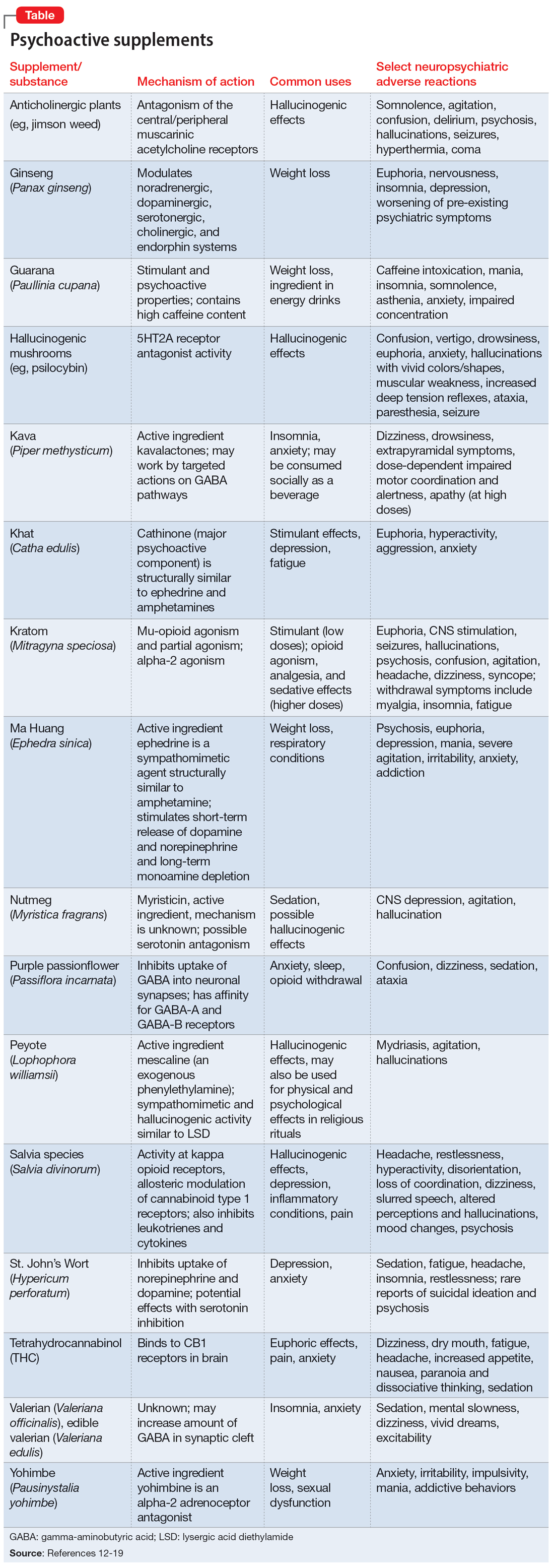

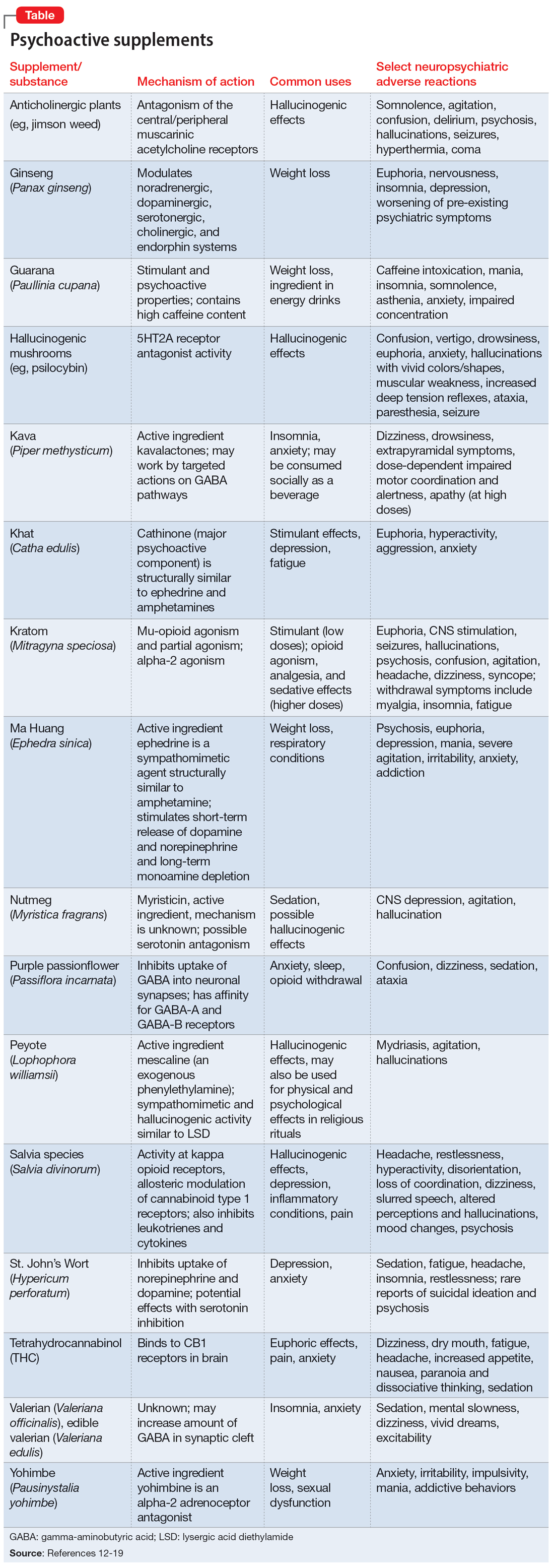

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...

Another category of “supplements” includes medications that are not FDA-approved but are approved for therapeutic use in other countries and readily available in the US via online sources. Such medications include phenibut, a glutamic acid derivative that functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and outside of the US it is prescribed for anxiolysis and other psychiatric indications.22 In the US, phenibut may be used as a nootropic or as a dietary supplement to treat anxiety, sleep problems, and other psychiatric disorders.22 It may also be used recreationally to induce euphoria. Chronic phenibut use results in tolerance and abrupt discontinuation may mimic benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.13,22

Educating patients about supplements

One of the most critical steps in assessing a patient’s supplement use is to directly ask them about their use of herbal or over-the-counter products. Research has consistently shown that patients are unlikely to disclose supplement use unless they are specifically asked.23,24

Additional strategies include25,26:

- Approach patients without judgment; ask open-ended questions to determine their motivations for using supplements.

- Explain the difference between supplements medically necessary to treat vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium) and those without robust clinical evidence.

- Counsel patients that many supplements with psychoactive properties, if indicated, are generally meant to be used short-term and not as substitutes for prescription medications.

- Educate patients that supplements have limited evidence regarding their safety and efficacy, but like prescription medications, supplements may cause organ damage, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions.

- Remind patients that commonly used nutritional supplements/dietary aids, including protein or workout supplements, may contain potentially harmful ingredients.

- Utilize evidence-based resources such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database14 or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov) to review levels of evidence and educate patients.

- When toxicity or withdrawal is suspected, reach out to local poison control centers for guidance.

- For a patient with a potential supplement-related substance use disorder, urine drug screens may be of limited utility and evidence is often sparse; clinicians may need to rely on primary literature such as case reports to guide management.

- If patients wish to continue taking a supplement, recommend they purchase supplements from manufacturers that have achieved the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. Products with the USP mark undergo quality assurance measures to ensure the product contains the ingredients listed on the label in the declared potency and amounts, does not contain harmful levels of contaminants, will be metabolized in the body within a specified amount of time, and has been produced in keeping with FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.

CASE CONTINUED

In the ED, the consulting psychiatry team discusses Mr. D’s use of phenibut with him, and asks if he uses any additional supplements or nonprescription medications. Mr. D discloses he has been anxious and having trouble sleeping, and a friend recommended phenibut as a safe, natural alternative to medication. The team explains to Mr. D that phenibut’s efficacy has not been studied in the US and that based on available evidence, it is likely unsafe. It may have serious adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, and is potentially addictive.

Mr. D says he was unaware of these risks and agrees to stop taking phenibut. The treatment team discharges him from the ED with a referral for outpatient psychiatric services to address his anxiety and insomnia.

Related Resources

- Tillman B. The hidden dangers of supplements: a case of substance-induced psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2020; 19(7):e7-e8. doi:10.12788/cp.0018

- McQueen CE. Herb–drug interactions: caution patients when changing supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2017; 16(6):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine • Fioricet with Codeine

1. Graziano S, Orsolini L, Rotolo MC, et al. Herbal highs: review on psychoactive effects and neuropharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):750-761.

2. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

3. O’Neill-Dee C, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Natural psychoactive substance-related exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(8):813-820.

4. Gray DC, Rutledge CM. Herbal supplements in primary care: patient perceptions, motivations, and effects on use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):6-12.

5. Wu K, Messamore E. Reimagining roles of dietary supplements in psychiatric care. AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E437-E442.

6. Snyder FJ, Dundas ML, Kirkpatrick C, et al. Use and safety perceptions regarding herbal supplements: a study of older persons in southeast Idaho. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(1):81-95.

7. Schulz P, Hede V. Alternative and complementary approaches in psychiatry: beliefs versus evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(3):207-214.

8. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Pub L 103-417, 103rd Cong (1993-1994).

9. Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):478-485.

10. New psychoactive substances. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. November 10, 2021. Updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/new-psychoactive-substances/

11. Shafi A, Berry AJ, Sumnall H, et al. New psychoactive substances: a review and updates. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320967197.

12. Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, et al. Adverse psychiatric effects associated with herbal weight-loss products. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:120679.

13. IBM Micromedex POISINDEX® System. IBM Watson Health. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com

14. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

15. Savage KM, Stough CK, Byrne GJ, et al. Kava for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (K-GAD): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:493.

16. Swogger MT, Smith KE, Garcia-Romeu A, et al. Understanding kratom use: a guide for healthcare providers. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:801855.

17. Modabbernia A, Akhondzadeh S. Saffron, passionflower, valerian and sage for mental health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):85-91.

18. Coffeen U, Pellicer F. Salvia divinorum: from recreational hallucinogenic use to analgesic and anti-inflammatory action. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1069-1076.

19. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Valerian Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Updated March 15, 2013. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Valerian-HealthProfessional

20. An H, Sohn H, Chung S. Phentermine, sibutramine and affective disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(1):7-12.

21. Miliano C, Margiani G, Fattore L, et al. Sales and advertising channels of new psychoactive substances (NPS): internet, social networks, and smartphone apps. Brain Sci. 2018;8(7):123.

22. Hardman MI, Sprung J, Weingarten TN. Acute phenibut withdrawal: a comprehensive literature review and illustrative case report. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019;19(2):125-129.

23. Guzman JR, Paterniti DA, Liu Y, et al. Factors related to disclosure and nondisclosure of dietary supplements in primary care, integrative medicine, and naturopathic medicine. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2019;5(4):10.23937/2469-5793/1510109.

24. Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1573.

25. Aldridge Young C. ‘No miracle cures’: counseling patients about dietary supplements. Pharmacy Today. 2014;February:35.

26. United States Pharmacopeia. USP Verified Mark. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.usp.org/verification-services/verified-mark

Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...

Another category of “supplements” includes medications that are not FDA-approved but are approved for therapeutic use in other countries and readily available in the US via online sources. Such medications include phenibut, a glutamic acid derivative that functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and outside of the US it is prescribed for anxiolysis and other psychiatric indications.22 In the US, phenibut may be used as a nootropic or as a dietary supplement to treat anxiety, sleep problems, and other psychiatric disorders.22 It may also be used recreationally to induce euphoria. Chronic phenibut use results in tolerance and abrupt discontinuation may mimic benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.13,22

Educating patients about supplements

One of the most critical steps in assessing a patient’s supplement use is to directly ask them about their use of herbal or over-the-counter products. Research has consistently shown that patients are unlikely to disclose supplement use unless they are specifically asked.23,24

Additional strategies include25,26:

- Approach patients without judgment; ask open-ended questions to determine their motivations for using supplements.

- Explain the difference between supplements medically necessary to treat vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium) and those without robust clinical evidence.

- Counsel patients that many supplements with psychoactive properties, if indicated, are generally meant to be used short-term and not as substitutes for prescription medications.

- Educate patients that supplements have limited evidence regarding their safety and efficacy, but like prescription medications, supplements may cause organ damage, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions.

- Remind patients that commonly used nutritional supplements/dietary aids, including protein or workout supplements, may contain potentially harmful ingredients.

- Utilize evidence-based resources such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database14 or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov) to review levels of evidence and educate patients.

- When toxicity or withdrawal is suspected, reach out to local poison control centers for guidance.

- For a patient with a potential supplement-related substance use disorder, urine drug screens may be of limited utility and evidence is often sparse; clinicians may need to rely on primary literature such as case reports to guide management.

- If patients wish to continue taking a supplement, recommend they purchase supplements from manufacturers that have achieved the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. Products with the USP mark undergo quality assurance measures to ensure the product contains the ingredients listed on the label in the declared potency and amounts, does not contain harmful levels of contaminants, will be metabolized in the body within a specified amount of time, and has been produced in keeping with FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.

CASE CONTINUED

In the ED, the consulting psychiatry team discusses Mr. D’s use of phenibut with him, and asks if he uses any additional supplements or nonprescription medications. Mr. D discloses he has been anxious and having trouble sleeping, and a friend recommended phenibut as a safe, natural alternative to medication. The team explains to Mr. D that phenibut’s efficacy has not been studied in the US and that based on available evidence, it is likely unsafe. It may have serious adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, and is potentially addictive.

Mr. D says he was unaware of these risks and agrees to stop taking phenibut. The treatment team discharges him from the ED with a referral for outpatient psychiatric services to address his anxiety and insomnia.

Related Resources

- Tillman B. The hidden dangers of supplements: a case of substance-induced psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2020; 19(7):e7-e8. doi:10.12788/cp.0018

- McQueen CE. Herb–drug interactions: caution patients when changing supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2017; 16(6):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine • Fioricet with Codeine

Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...

Another category of “supplements” includes medications that are not FDA-approved but are approved for therapeutic use in other countries and readily available in the US via online sources. Such medications include phenibut, a glutamic acid derivative that functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and outside of the US it is prescribed for anxiolysis and other psychiatric indications.22 In the US, phenibut may be used as a nootropic or as a dietary supplement to treat anxiety, sleep problems, and other psychiatric disorders.22 It may also be used recreationally to induce euphoria. Chronic phenibut use results in tolerance and abrupt discontinuation may mimic benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.13,22

Educating patients about supplements

One of the most critical steps in assessing a patient’s supplement use is to directly ask them about their use of herbal or over-the-counter products. Research has consistently shown that patients are unlikely to disclose supplement use unless they are specifically asked.23,24

Additional strategies include25,26:

- Approach patients without judgment; ask open-ended questions to determine their motivations for using supplements.

- Explain the difference between supplements medically necessary to treat vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium) and those without robust clinical evidence.

- Counsel patients that many supplements with psychoactive properties, if indicated, are generally meant to be used short-term and not as substitutes for prescription medications.

- Educate patients that supplements have limited evidence regarding their safety and efficacy, but like prescription medications, supplements may cause organ damage, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions.

- Remind patients that commonly used nutritional supplements/dietary aids, including protein or workout supplements, may contain potentially harmful ingredients.

- Utilize evidence-based resources such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database14 or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov) to review levels of evidence and educate patients.

- When toxicity or withdrawal is suspected, reach out to local poison control centers for guidance.

- For a patient with a potential supplement-related substance use disorder, urine drug screens may be of limited utility and evidence is often sparse; clinicians may need to rely on primary literature such as case reports to guide management.

- If patients wish to continue taking a supplement, recommend they purchase supplements from manufacturers that have achieved the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. Products with the USP mark undergo quality assurance measures to ensure the product contains the ingredients listed on the label in the declared potency and amounts, does not contain harmful levels of contaminants, will be metabolized in the body within a specified amount of time, and has been produced in keeping with FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.

CASE CONTINUED

In the ED, the consulting psychiatry team discusses Mr. D’s use of phenibut with him, and asks if he uses any additional supplements or nonprescription medications. Mr. D discloses he has been anxious and having trouble sleeping, and a friend recommended phenibut as a safe, natural alternative to medication. The team explains to Mr. D that phenibut’s efficacy has not been studied in the US and that based on available evidence, it is likely unsafe. It may have serious adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, and is potentially addictive.

Mr. D says he was unaware of these risks and agrees to stop taking phenibut. The treatment team discharges him from the ED with a referral for outpatient psychiatric services to address his anxiety and insomnia.

Related Resources

- Tillman B. The hidden dangers of supplements: a case of substance-induced psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2020; 19(7):e7-e8. doi:10.12788/cp.0018

- McQueen CE. Herb–drug interactions: caution patients when changing supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2017; 16(6):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine • Fioricet with Codeine

1. Graziano S, Orsolini L, Rotolo MC, et al. Herbal highs: review on psychoactive effects and neuropharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):750-761.

2. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

3. O’Neill-Dee C, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Natural psychoactive substance-related exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(8):813-820.

4. Gray DC, Rutledge CM. Herbal supplements in primary care: patient perceptions, motivations, and effects on use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):6-12.

5. Wu K, Messamore E. Reimagining roles of dietary supplements in psychiatric care. AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E437-E442.

6. Snyder FJ, Dundas ML, Kirkpatrick C, et al. Use and safety perceptions regarding herbal supplements: a study of older persons in southeast Idaho. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(1):81-95.

7. Schulz P, Hede V. Alternative and complementary approaches in psychiatry: beliefs versus evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(3):207-214.

8. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Pub L 103-417, 103rd Cong (1993-1994).

9. Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):478-485.

10. New psychoactive substances. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. November 10, 2021. Updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/new-psychoactive-substances/

11. Shafi A, Berry AJ, Sumnall H, et al. New psychoactive substances: a review and updates. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320967197.

12. Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, et al. Adverse psychiatric effects associated with herbal weight-loss products. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:120679.

13. IBM Micromedex POISINDEX® System. IBM Watson Health. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com

14. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

15. Savage KM, Stough CK, Byrne GJ, et al. Kava for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (K-GAD): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:493.

16. Swogger MT, Smith KE, Garcia-Romeu A, et al. Understanding kratom use: a guide for healthcare providers. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:801855.

17. Modabbernia A, Akhondzadeh S. Saffron, passionflower, valerian and sage for mental health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):85-91.

18. Coffeen U, Pellicer F. Salvia divinorum: from recreational hallucinogenic use to analgesic and anti-inflammatory action. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1069-1076.

19. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Valerian Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Updated March 15, 2013. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Valerian-HealthProfessional

20. An H, Sohn H, Chung S. Phentermine, sibutramine and affective disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(1):7-12.

21. Miliano C, Margiani G, Fattore L, et al. Sales and advertising channels of new psychoactive substances (NPS): internet, social networks, and smartphone apps. Brain Sci. 2018;8(7):123.

22. Hardman MI, Sprung J, Weingarten TN. Acute phenibut withdrawal: a comprehensive literature review and illustrative case report. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019;19(2):125-129.

23. Guzman JR, Paterniti DA, Liu Y, et al. Factors related to disclosure and nondisclosure of dietary supplements in primary care, integrative medicine, and naturopathic medicine. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2019;5(4):10.23937/2469-5793/1510109.

24. Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1573.

25. Aldridge Young C. ‘No miracle cures’: counseling patients about dietary supplements. Pharmacy Today. 2014;February:35.

26. United States Pharmacopeia. USP Verified Mark. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.usp.org/verification-services/verified-mark

1. Graziano S, Orsolini L, Rotolo MC, et al. Herbal highs: review on psychoactive effects and neuropharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):750-761.

2. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

3. O’Neill-Dee C, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Natural psychoactive substance-related exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(8):813-820.

4. Gray DC, Rutledge CM. Herbal supplements in primary care: patient perceptions, motivations, and effects on use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):6-12.

5. Wu K, Messamore E. Reimagining roles of dietary supplements in psychiatric care. AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E437-E442.

6. Snyder FJ, Dundas ML, Kirkpatrick C, et al. Use and safety perceptions regarding herbal supplements: a study of older persons in southeast Idaho. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(1):81-95.

7. Schulz P, Hede V. Alternative and complementary approaches in psychiatry: beliefs versus evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(3):207-214.

8. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Pub L 103-417, 103rd Cong (1993-1994).

9. Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):478-485.

10. New psychoactive substances. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. November 10, 2021. Updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/new-psychoactive-substances/

11. Shafi A, Berry AJ, Sumnall H, et al. New psychoactive substances: a review and updates. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320967197.

12. Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, et al. Adverse psychiatric effects associated with herbal weight-loss products. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:120679.

13. IBM Micromedex POISINDEX® System. IBM Watson Health. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com

14. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com