User login

Native American Tribes Settle ‘Epic’ Opioid Deal

Hundreds of Native American tribes have tentatively settled in what one of the lead attorneys describes as “an epic deal”: The top 3 pharmaceutical distributors in the US and Johnson & Johnson have agreed to pay $665 million for deceptive marketing practices and overdistribution of opioids. Native Americans were among those hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. Between 2006 and 2014, Native Americans were nearly 50% more likely than non-Natives to die of an opioid overdose. In 2014, they ranked number 1 for death by opioid overdose.

Overprescribing was rampant. In some areas, such as southwestern Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and Alabama, prescriptions were 5 to 6 times higher than the national average. The overprescribing was largely due to massive and aggressive billion-dollar marketing campaigns, which misrepresented the safety of opioid medications. Purdue Pharma, for instance, trained sales representatives to claim that the risk of addiction was “less than 1 percent.” In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Caleb Alexander, MD, codirector of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, said, “When I was in residency training, we were taught that one needn’t worry about the addictive potential of opioids if a patient had true pain.” He said it was no accident that physicians were cultivated to overestimate the effectiveness for chronic, noncancer pain while underestimating the risks.

Native Americans were not only in the target group for prescriptions, but also apparently singularly targeted. “We were preyed upon,” said Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby in the Washington Post. “It was unconscionable.” A Washington Post analysis found that, between 2006 and 2014, opioid distributors shipped an average of 36 pills per person in the US. States in the so-called opioid belt (mostly Southern states), received an average of 60 to 66 pills per person. The distributors shipped 57 pills per person to Oklahoma, home to nearly 322,000 Native Americans. (The opioid death rate for Native Americans in Oklahoma from 2006 to 2014 was more than triple the nationwide rate for non-Natives.) In South Dakota as recently as 2015, enough opioids were prescribed to medicate every adult around-the-clock for 19 consecutive days. Native Americans comprise 9% of South Dakota’s population; however, almost 30% of the patients are being treated for opioid use disorder.

In the settlement, which is a first for tribes, McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen would pay $515 million over 7 years. Johnson & Johnson would contribute $150 million in 2 years to the federally recognized tribes. “This settlement is a real turning point in history,” said Lloyd Miller, one of the attorneys representing one-third of the litigating tribes.

But the money is still small compensation for ravaging millions of lives. “Flooding the Native community with Western medicine—sedating a population rather than seeking to understand its needs and challenges—is not an acceptable means of handling its trauma,” the Lakota People’s Law Project says in an article on its website. Thus, the money dispersal will be overseen by a panel of tribal health experts, to go toward programs that aid drug users and their communities.

The funds will be managed in a way that will consider the long-term damage, Native American leaders vow. Children, for instance, have not been exempt from the sequelae of the overprescribing. Foster care systems are “overrun” with children of addicted parents, the Law Project says, and the children are placed in homes outside the tribe. “In the long run, this has the potential to curtail tribal membership, break down familial lines, and degrade cultural values.”

Dealing with the problem has drained tribal resources—doubly strained by the COVID-19 epidemic. Chairman Douglas Yankton, of the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota, said in a statement, “The dollars that will flow to Tribes under this initial settlement will help fund crucial, on-reservation, culturally appropriate opioid treatment services.”

However, Chairman Kristopher Peters, of the Squaxin Island Tribe in Washington State, told the Washington Post, “There is no amount of money that’s going to solve the generational issues that have been created from this. Our hope is that we can use these funds to help revitalize our culture and help heal our people.”

Johnson & Johnson says it no longer sells prescription opioids in the US

Hundreds of Native American tribes have tentatively settled in what one of the lead attorneys describes as “an epic deal”: The top 3 pharmaceutical distributors in the US and Johnson & Johnson have agreed to pay $665 million for deceptive marketing practices and overdistribution of opioids. Native Americans were among those hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. Between 2006 and 2014, Native Americans were nearly 50% more likely than non-Natives to die of an opioid overdose. In 2014, they ranked number 1 for death by opioid overdose.

Overprescribing was rampant. In some areas, such as southwestern Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and Alabama, prescriptions were 5 to 6 times higher than the national average. The overprescribing was largely due to massive and aggressive billion-dollar marketing campaigns, which misrepresented the safety of opioid medications. Purdue Pharma, for instance, trained sales representatives to claim that the risk of addiction was “less than 1 percent.” In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Caleb Alexander, MD, codirector of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, said, “When I was in residency training, we were taught that one needn’t worry about the addictive potential of opioids if a patient had true pain.” He said it was no accident that physicians were cultivated to overestimate the effectiveness for chronic, noncancer pain while underestimating the risks.

Native Americans were not only in the target group for prescriptions, but also apparently singularly targeted. “We were preyed upon,” said Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby in the Washington Post. “It was unconscionable.” A Washington Post analysis found that, between 2006 and 2014, opioid distributors shipped an average of 36 pills per person in the US. States in the so-called opioid belt (mostly Southern states), received an average of 60 to 66 pills per person. The distributors shipped 57 pills per person to Oklahoma, home to nearly 322,000 Native Americans. (The opioid death rate for Native Americans in Oklahoma from 2006 to 2014 was more than triple the nationwide rate for non-Natives.) In South Dakota as recently as 2015, enough opioids were prescribed to medicate every adult around-the-clock for 19 consecutive days. Native Americans comprise 9% of South Dakota’s population; however, almost 30% of the patients are being treated for opioid use disorder.

In the settlement, which is a first for tribes, McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen would pay $515 million over 7 years. Johnson & Johnson would contribute $150 million in 2 years to the federally recognized tribes. “This settlement is a real turning point in history,” said Lloyd Miller, one of the attorneys representing one-third of the litigating tribes.

But the money is still small compensation for ravaging millions of lives. “Flooding the Native community with Western medicine—sedating a population rather than seeking to understand its needs and challenges—is not an acceptable means of handling its trauma,” the Lakota People’s Law Project says in an article on its website. Thus, the money dispersal will be overseen by a panel of tribal health experts, to go toward programs that aid drug users and their communities.

The funds will be managed in a way that will consider the long-term damage, Native American leaders vow. Children, for instance, have not been exempt from the sequelae of the overprescribing. Foster care systems are “overrun” with children of addicted parents, the Law Project says, and the children are placed in homes outside the tribe. “In the long run, this has the potential to curtail tribal membership, break down familial lines, and degrade cultural values.”

Dealing with the problem has drained tribal resources—doubly strained by the COVID-19 epidemic. Chairman Douglas Yankton, of the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota, said in a statement, “The dollars that will flow to Tribes under this initial settlement will help fund crucial, on-reservation, culturally appropriate opioid treatment services.”

However, Chairman Kristopher Peters, of the Squaxin Island Tribe in Washington State, told the Washington Post, “There is no amount of money that’s going to solve the generational issues that have been created from this. Our hope is that we can use these funds to help revitalize our culture and help heal our people.”

Johnson & Johnson says it no longer sells prescription opioids in the US

Hundreds of Native American tribes have tentatively settled in what one of the lead attorneys describes as “an epic deal”: The top 3 pharmaceutical distributors in the US and Johnson & Johnson have agreed to pay $665 million for deceptive marketing practices and overdistribution of opioids. Native Americans were among those hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. Between 2006 and 2014, Native Americans were nearly 50% more likely than non-Natives to die of an opioid overdose. In 2014, they ranked number 1 for death by opioid overdose.

Overprescribing was rampant. In some areas, such as southwestern Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and Alabama, prescriptions were 5 to 6 times higher than the national average. The overprescribing was largely due to massive and aggressive billion-dollar marketing campaigns, which misrepresented the safety of opioid medications. Purdue Pharma, for instance, trained sales representatives to claim that the risk of addiction was “less than 1 percent.” In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Caleb Alexander, MD, codirector of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, said, “When I was in residency training, we were taught that one needn’t worry about the addictive potential of opioids if a patient had true pain.” He said it was no accident that physicians were cultivated to overestimate the effectiveness for chronic, noncancer pain while underestimating the risks.

Native Americans were not only in the target group for prescriptions, but also apparently singularly targeted. “We were preyed upon,” said Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby in the Washington Post. “It was unconscionable.” A Washington Post analysis found that, between 2006 and 2014, opioid distributors shipped an average of 36 pills per person in the US. States in the so-called opioid belt (mostly Southern states), received an average of 60 to 66 pills per person. The distributors shipped 57 pills per person to Oklahoma, home to nearly 322,000 Native Americans. (The opioid death rate for Native Americans in Oklahoma from 2006 to 2014 was more than triple the nationwide rate for non-Natives.) In South Dakota as recently as 2015, enough opioids were prescribed to medicate every adult around-the-clock for 19 consecutive days. Native Americans comprise 9% of South Dakota’s population; however, almost 30% of the patients are being treated for opioid use disorder.

In the settlement, which is a first for tribes, McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen would pay $515 million over 7 years. Johnson & Johnson would contribute $150 million in 2 years to the federally recognized tribes. “This settlement is a real turning point in history,” said Lloyd Miller, one of the attorneys representing one-third of the litigating tribes.

But the money is still small compensation for ravaging millions of lives. “Flooding the Native community with Western medicine—sedating a population rather than seeking to understand its needs and challenges—is not an acceptable means of handling its trauma,” the Lakota People’s Law Project says in an article on its website. Thus, the money dispersal will be overseen by a panel of tribal health experts, to go toward programs that aid drug users and their communities.

The funds will be managed in a way that will consider the long-term damage, Native American leaders vow. Children, for instance, have not been exempt from the sequelae of the overprescribing. Foster care systems are “overrun” with children of addicted parents, the Law Project says, and the children are placed in homes outside the tribe. “In the long run, this has the potential to curtail tribal membership, break down familial lines, and degrade cultural values.”

Dealing with the problem has drained tribal resources—doubly strained by the COVID-19 epidemic. Chairman Douglas Yankton, of the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota, said in a statement, “The dollars that will flow to Tribes under this initial settlement will help fund crucial, on-reservation, culturally appropriate opioid treatment services.”

However, Chairman Kristopher Peters, of the Squaxin Island Tribe in Washington State, told the Washington Post, “There is no amount of money that’s going to solve the generational issues that have been created from this. Our hope is that we can use these funds to help revitalize our culture and help heal our people.”

Johnson & Johnson says it no longer sells prescription opioids in the US

Opioid exposure in early pregnancy linked to congenital anomalies

Exposure to opioid analgesics during the first trimester of pregnancy appears to increase the risk of congenital anomalies diagnosed in the first year of life, researchers report.

While the absolute risk of congenital anomalies was low, these findings add to an increasing body of evidence suggesting that prenatal exposure to opioids may confer harm to infants post partum.

“We undertook a population-based cohort study to estimate associations between opioid analgesic exposure during the first trimester and congenital anomalies using health administrative data capturing all narcotic prescriptions during pregnancy,” lead author Alexa C. Bowie, MPH, of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., and colleagues reported in CMAJ.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed administrative health data in a single-payer health care system from 2013 to 2018. They identified parent-infant pair records for all live births and stillbirths that occurred at more than 20 weeks’ gestation.

The exposure of interest was a prescription for any opioid analgesic with a fill date between the estimated date of conception and less than 14 weeks’ gestation. The referent group included any infant not exposed to an opioid analgesic during the index pregnancy period.

Results

The study cohort included a total of 599,579 gestational parent-infant pairs. Of these, 11,903 (2.0%) were exposed to opioid analgesics, and most were exposed during the first trimester only (75.8%).

Overall, 2.0% of these infants developed a congenital anomaly during the first year of life; the prevalence of congenital anomalies was 2.0% in unexposed infants and 2.8% in exposed infants.

Relative to unexposed infants, the researchers observed greater risks among infants who were exposed for some anomaly groups, including many specific anomalies, such as ankyloglossia (any opioid: adjusted risk ratio, 1.88; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-2.72; codeine: aRR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.35-3.40), as well as gastrointestinal anomalies (any opioid: aRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.15-1.85; codeine: aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.12-2.09; tramadol: aRR, 2.69; 95% CI 1.34-5.38).

After sensitivity analyses, which included exposure 4 weeks before conception or excluded individuals with exposure to opioid analgesics before pregnancy, the findings remained unchanged.

“Although the overall risk was low, we observed an increased risk of any congenital anomaly with tramadol, and a previously unreported risk with morphine,” the researchers wrote.

“Previous studies reported elevated risks of heart anomalies with first-trimester exposure to any opioid analgesic, codeine, and tramadol, but others reported no association with any opioid analgesic or codeine,” they explained.

Interpreting the results

Study author Susan Brogly, PhD, of Queen’s University said “Our population-based study confirms evidence of a small increased risk of birth defects from opioid analgesic exposure in the first trimester that was observed in a recent study of private insurance and Medicaid beneficiaries in the U.S. We further show that this small increased risk is not due to other risk factors for fetal harm in women who may take these medications.”

“An opioid prescription dispensed in the first trimester would imply that there was an acute injury or chronic condition also present in the first trimester, which may also be associated with congenital abnormalities,” commented Elisabeth Poorman, MD, MPH, a clinical instructor and primary care physician at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Opioid use disorder is often diagnosed incorrectly; since the researchers used diagnostic billing codes to exclude individuals with opioid use disorder, some women may have been missed,” Dr. Poorman explained.

Ms. Bowie and colleagues acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the identification of cases using diagnostic billing codes. As a result, exposure-dependent recording bias could be present and limit the applicability of the findings.

“The diagnosis and documentation of minor anomalies and those with subtle medical significance could be vulnerable to exposure-dependent recording bias,” Ms. Bowie wrote.

Dr. Poorman recommended that these results should be interpreted with caution given these and other limitations. “Overall, results from this study may imply that there is limited evidence to suspect opioids are related to congenital abnormalities due to a very small difference observed in relatively unequal groups,” she concluded.

This study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development and was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health. One author reported receiving honoraria from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

Exposure to opioid analgesics during the first trimester of pregnancy appears to increase the risk of congenital anomalies diagnosed in the first year of life, researchers report.

While the absolute risk of congenital anomalies was low, these findings add to an increasing body of evidence suggesting that prenatal exposure to opioids may confer harm to infants post partum.

“We undertook a population-based cohort study to estimate associations between opioid analgesic exposure during the first trimester and congenital anomalies using health administrative data capturing all narcotic prescriptions during pregnancy,” lead author Alexa C. Bowie, MPH, of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., and colleagues reported in CMAJ.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed administrative health data in a single-payer health care system from 2013 to 2018. They identified parent-infant pair records for all live births and stillbirths that occurred at more than 20 weeks’ gestation.

The exposure of interest was a prescription for any opioid analgesic with a fill date between the estimated date of conception and less than 14 weeks’ gestation. The referent group included any infant not exposed to an opioid analgesic during the index pregnancy period.

Results

The study cohort included a total of 599,579 gestational parent-infant pairs. Of these, 11,903 (2.0%) were exposed to opioid analgesics, and most were exposed during the first trimester only (75.8%).

Overall, 2.0% of these infants developed a congenital anomaly during the first year of life; the prevalence of congenital anomalies was 2.0% in unexposed infants and 2.8% in exposed infants.

Relative to unexposed infants, the researchers observed greater risks among infants who were exposed for some anomaly groups, including many specific anomalies, such as ankyloglossia (any opioid: adjusted risk ratio, 1.88; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-2.72; codeine: aRR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.35-3.40), as well as gastrointestinal anomalies (any opioid: aRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.15-1.85; codeine: aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.12-2.09; tramadol: aRR, 2.69; 95% CI 1.34-5.38).

After sensitivity analyses, which included exposure 4 weeks before conception or excluded individuals with exposure to opioid analgesics before pregnancy, the findings remained unchanged.

“Although the overall risk was low, we observed an increased risk of any congenital anomaly with tramadol, and a previously unreported risk with morphine,” the researchers wrote.

“Previous studies reported elevated risks of heart anomalies with first-trimester exposure to any opioid analgesic, codeine, and tramadol, but others reported no association with any opioid analgesic or codeine,” they explained.

Interpreting the results

Study author Susan Brogly, PhD, of Queen’s University said “Our population-based study confirms evidence of a small increased risk of birth defects from opioid analgesic exposure in the first trimester that was observed in a recent study of private insurance and Medicaid beneficiaries in the U.S. We further show that this small increased risk is not due to other risk factors for fetal harm in women who may take these medications.”

“An opioid prescription dispensed in the first trimester would imply that there was an acute injury or chronic condition also present in the first trimester, which may also be associated with congenital abnormalities,” commented Elisabeth Poorman, MD, MPH, a clinical instructor and primary care physician at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Opioid use disorder is often diagnosed incorrectly; since the researchers used diagnostic billing codes to exclude individuals with opioid use disorder, some women may have been missed,” Dr. Poorman explained.

Ms. Bowie and colleagues acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the identification of cases using diagnostic billing codes. As a result, exposure-dependent recording bias could be present and limit the applicability of the findings.

“The diagnosis and documentation of minor anomalies and those with subtle medical significance could be vulnerable to exposure-dependent recording bias,” Ms. Bowie wrote.

Dr. Poorman recommended that these results should be interpreted with caution given these and other limitations. “Overall, results from this study may imply that there is limited evidence to suspect opioids are related to congenital abnormalities due to a very small difference observed in relatively unequal groups,” she concluded.

This study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development and was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health. One author reported receiving honoraria from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

Exposure to opioid analgesics during the first trimester of pregnancy appears to increase the risk of congenital anomalies diagnosed in the first year of life, researchers report.

While the absolute risk of congenital anomalies was low, these findings add to an increasing body of evidence suggesting that prenatal exposure to opioids may confer harm to infants post partum.

“We undertook a population-based cohort study to estimate associations between opioid analgesic exposure during the first trimester and congenital anomalies using health administrative data capturing all narcotic prescriptions during pregnancy,” lead author Alexa C. Bowie, MPH, of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., and colleagues reported in CMAJ.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed administrative health data in a single-payer health care system from 2013 to 2018. They identified parent-infant pair records for all live births and stillbirths that occurred at more than 20 weeks’ gestation.

The exposure of interest was a prescription for any opioid analgesic with a fill date between the estimated date of conception and less than 14 weeks’ gestation. The referent group included any infant not exposed to an opioid analgesic during the index pregnancy period.

Results

The study cohort included a total of 599,579 gestational parent-infant pairs. Of these, 11,903 (2.0%) were exposed to opioid analgesics, and most were exposed during the first trimester only (75.8%).

Overall, 2.0% of these infants developed a congenital anomaly during the first year of life; the prevalence of congenital anomalies was 2.0% in unexposed infants and 2.8% in exposed infants.

Relative to unexposed infants, the researchers observed greater risks among infants who were exposed for some anomaly groups, including many specific anomalies, such as ankyloglossia (any opioid: adjusted risk ratio, 1.88; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-2.72; codeine: aRR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.35-3.40), as well as gastrointestinal anomalies (any opioid: aRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.15-1.85; codeine: aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.12-2.09; tramadol: aRR, 2.69; 95% CI 1.34-5.38).

After sensitivity analyses, which included exposure 4 weeks before conception or excluded individuals with exposure to opioid analgesics before pregnancy, the findings remained unchanged.

“Although the overall risk was low, we observed an increased risk of any congenital anomaly with tramadol, and a previously unreported risk with morphine,” the researchers wrote.

“Previous studies reported elevated risks of heart anomalies with first-trimester exposure to any opioid analgesic, codeine, and tramadol, but others reported no association with any opioid analgesic or codeine,” they explained.

Interpreting the results

Study author Susan Brogly, PhD, of Queen’s University said “Our population-based study confirms evidence of a small increased risk of birth defects from opioid analgesic exposure in the first trimester that was observed in a recent study of private insurance and Medicaid beneficiaries in the U.S. We further show that this small increased risk is not due to other risk factors for fetal harm in women who may take these medications.”

“An opioid prescription dispensed in the first trimester would imply that there was an acute injury or chronic condition also present in the first trimester, which may also be associated with congenital abnormalities,” commented Elisabeth Poorman, MD, MPH, a clinical instructor and primary care physician at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Opioid use disorder is often diagnosed incorrectly; since the researchers used diagnostic billing codes to exclude individuals with opioid use disorder, some women may have been missed,” Dr. Poorman explained.

Ms. Bowie and colleagues acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the identification of cases using diagnostic billing codes. As a result, exposure-dependent recording bias could be present and limit the applicability of the findings.

“The diagnosis and documentation of minor anomalies and those with subtle medical significance could be vulnerable to exposure-dependent recording bias,” Ms. Bowie wrote.

Dr. Poorman recommended that these results should be interpreted with caution given these and other limitations. “Overall, results from this study may imply that there is limited evidence to suspect opioids are related to congenital abnormalities due to a very small difference observed in relatively unequal groups,” she concluded.

This study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development and was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health. One author reported receiving honoraria from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

FROM CMAJ

Two emerging drugs exacerbating opioid crisis

Two illicit drugs are contributing to a sharp rise in fentanyl-related deaths, a new study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows.

Para-fluorofentanyl, a schedule I substance often found in heroin packets and counterfeit pills, is making a comeback on the illicit drug market, Jordan Trecki, PhD, and associates reported in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2022 Jan 28;71[4]:153-5). U.S. medical examiner reports and national law enforcement seizure data point to a rise in encounters of this drug along with metonitazene, a benzimidazole-opioid, in combination with fentanyl.

On their own, para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene can kill the user through respiratory depression. Combinations of these substances and other opioids, including fentanyl-related compounds or adulterants, “pose an even greater potential harm to the patient than previously observed,” reported Dr. Trecki, a pharmacologist affiliated with the Drug Enforcement Administration, and colleagues.

Opioids contribute to about 75% of all U.S. drug overdose deaths, which rose by 28.5% during 2020-2021, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. And fentanyl is replacing heroin as the primary drug of use, said addiction specialist Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, in an interview.

“For patients with stimulant use disorder and even cannabis use disorder, fentanyl is becoming more and more common as an adulterant in those substances, often resulting in inadvertent use. Hence, fentanyl and fentanyl-like drugs and fentanyl analogues are becoming increasingly common and important,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, director of the psychiatric emergency room at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System. He was not involved with the MMWR study.

Tennessee data reflect national problem

Recent data from a medical examiner in Knoxville, Tenn., illustrate what might be happening nationwide with those two emerging substances.

Over the last 2 years, the Knox County Regional Forensic Center has identified para-fluorofentanyl in the toxicology results of drug overdose victims, and metonitazene – either on its own or in combination with fentanyl and para-fluorofentanyl. Fentanyl appeared in 562 or 73% of 770 unintentional drug overdose deaths from November 2020 to August 2021. Forty-eight of these cases involved para-fluorofentanyl, and 26 involved metonitazene.

“Although the percentage of law enforcement encounters with these substances in Tennessee decreased relative to the national total percentage within this time frame, the increase in encounters both within Tennessee and nationally reflect an increased distribution of para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene throughout the United States,” the authors reported.

How to identify substances, manage overdoses

The authors encouraged physicians, labs, and medical examiners to be on the lookout for these two substances either in the emergency department or when identifying the cause of drug overdose deaths.

They also advised that stronger opioids, such as fentanyl, para-fluorofentanyl, metonitazene, or other benzimidazoles may warrant additional doses of the opioid-reversal drug naloxone.

While he hasn’t personally seen any of these drugs in his practice, “I would assume that these are on the rise due to inexpensive cost to manufacture and potency of effect,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, also an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The need for additional naloxone to manage acute overdoses is a key takeaway of the MMWR paper, he added. Clinicians should also educate patients about harm reduction strategies to avoid overdose death when using potentially powerful and unknown drugs. “Things like start low and go slow, buy from the same supplier, do not use opioids with alcohol or benzos, have Narcan available, do not use alone, etc.”

Dr. Fuehrlein had no disclosures.

Two illicit drugs are contributing to a sharp rise in fentanyl-related deaths, a new study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows.

Para-fluorofentanyl, a schedule I substance often found in heroin packets and counterfeit pills, is making a comeback on the illicit drug market, Jordan Trecki, PhD, and associates reported in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2022 Jan 28;71[4]:153-5). U.S. medical examiner reports and national law enforcement seizure data point to a rise in encounters of this drug along with metonitazene, a benzimidazole-opioid, in combination with fentanyl.

On their own, para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene can kill the user through respiratory depression. Combinations of these substances and other opioids, including fentanyl-related compounds or adulterants, “pose an even greater potential harm to the patient than previously observed,” reported Dr. Trecki, a pharmacologist affiliated with the Drug Enforcement Administration, and colleagues.

Opioids contribute to about 75% of all U.S. drug overdose deaths, which rose by 28.5% during 2020-2021, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. And fentanyl is replacing heroin as the primary drug of use, said addiction specialist Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, in an interview.

“For patients with stimulant use disorder and even cannabis use disorder, fentanyl is becoming more and more common as an adulterant in those substances, often resulting in inadvertent use. Hence, fentanyl and fentanyl-like drugs and fentanyl analogues are becoming increasingly common and important,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, director of the psychiatric emergency room at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System. He was not involved with the MMWR study.

Tennessee data reflect national problem

Recent data from a medical examiner in Knoxville, Tenn., illustrate what might be happening nationwide with those two emerging substances.

Over the last 2 years, the Knox County Regional Forensic Center has identified para-fluorofentanyl in the toxicology results of drug overdose victims, and metonitazene – either on its own or in combination with fentanyl and para-fluorofentanyl. Fentanyl appeared in 562 or 73% of 770 unintentional drug overdose deaths from November 2020 to August 2021. Forty-eight of these cases involved para-fluorofentanyl, and 26 involved metonitazene.

“Although the percentage of law enforcement encounters with these substances in Tennessee decreased relative to the national total percentage within this time frame, the increase in encounters both within Tennessee and nationally reflect an increased distribution of para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene throughout the United States,” the authors reported.

How to identify substances, manage overdoses

The authors encouraged physicians, labs, and medical examiners to be on the lookout for these two substances either in the emergency department or when identifying the cause of drug overdose deaths.

They also advised that stronger opioids, such as fentanyl, para-fluorofentanyl, metonitazene, or other benzimidazoles may warrant additional doses of the opioid-reversal drug naloxone.

While he hasn’t personally seen any of these drugs in his practice, “I would assume that these are on the rise due to inexpensive cost to manufacture and potency of effect,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, also an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The need for additional naloxone to manage acute overdoses is a key takeaway of the MMWR paper, he added. Clinicians should also educate patients about harm reduction strategies to avoid overdose death when using potentially powerful and unknown drugs. “Things like start low and go slow, buy from the same supplier, do not use opioids with alcohol or benzos, have Narcan available, do not use alone, etc.”

Dr. Fuehrlein had no disclosures.

Two illicit drugs are contributing to a sharp rise in fentanyl-related deaths, a new study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows.

Para-fluorofentanyl, a schedule I substance often found in heroin packets and counterfeit pills, is making a comeback on the illicit drug market, Jordan Trecki, PhD, and associates reported in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2022 Jan 28;71[4]:153-5). U.S. medical examiner reports and national law enforcement seizure data point to a rise in encounters of this drug along with metonitazene, a benzimidazole-opioid, in combination with fentanyl.

On their own, para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene can kill the user through respiratory depression. Combinations of these substances and other opioids, including fentanyl-related compounds or adulterants, “pose an even greater potential harm to the patient than previously observed,” reported Dr. Trecki, a pharmacologist affiliated with the Drug Enforcement Administration, and colleagues.

Opioids contribute to about 75% of all U.S. drug overdose deaths, which rose by 28.5% during 2020-2021, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. And fentanyl is replacing heroin as the primary drug of use, said addiction specialist Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, in an interview.

“For patients with stimulant use disorder and even cannabis use disorder, fentanyl is becoming more and more common as an adulterant in those substances, often resulting in inadvertent use. Hence, fentanyl and fentanyl-like drugs and fentanyl analogues are becoming increasingly common and important,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, director of the psychiatric emergency room at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System. He was not involved with the MMWR study.

Tennessee data reflect national problem

Recent data from a medical examiner in Knoxville, Tenn., illustrate what might be happening nationwide with those two emerging substances.

Over the last 2 years, the Knox County Regional Forensic Center has identified para-fluorofentanyl in the toxicology results of drug overdose victims, and metonitazene – either on its own or in combination with fentanyl and para-fluorofentanyl. Fentanyl appeared in 562 or 73% of 770 unintentional drug overdose deaths from November 2020 to August 2021. Forty-eight of these cases involved para-fluorofentanyl, and 26 involved metonitazene.

“Although the percentage of law enforcement encounters with these substances in Tennessee decreased relative to the national total percentage within this time frame, the increase in encounters both within Tennessee and nationally reflect an increased distribution of para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene throughout the United States,” the authors reported.

How to identify substances, manage overdoses

The authors encouraged physicians, labs, and medical examiners to be on the lookout for these two substances either in the emergency department or when identifying the cause of drug overdose deaths.

They also advised that stronger opioids, such as fentanyl, para-fluorofentanyl, metonitazene, or other benzimidazoles may warrant additional doses of the opioid-reversal drug naloxone.

While he hasn’t personally seen any of these drugs in his practice, “I would assume that these are on the rise due to inexpensive cost to manufacture and potency of effect,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, also an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The need for additional naloxone to manage acute overdoses is a key takeaway of the MMWR paper, he added. Clinicians should also educate patients about harm reduction strategies to avoid overdose death when using potentially powerful and unknown drugs. “Things like start low and go slow, buy from the same supplier, do not use opioids with alcohol or benzos, have Narcan available, do not use alone, etc.”

Dr. Fuehrlein had no disclosures.

Marijuana use linked to nausea, vomiting of pregnancy

Use of marijuana during pregnancy was associated with symptoms of nausea and vomiting and with use of prescribed antiemetics, according to a study presented Feb. 3 at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. It’s unclear, however, whether the association suggests that pregnant individuals are using marijuana in an attempt to treat their symptoms or whether the marijuana use is contributing to nausea and vomiting – or neither, Torri D. Metz, MD, of the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, told attendees.

“Cannabis use has been increasing among pregnant individuals,” Dr. Metz said. “Reported reasons for use range from habit to perceived benefit for treatment of medical conditions, including nausea and vomiting.” She noted a previous study that found that dispensary employees in Colorado recommended cannabis to pregnant callers for treating of nausea despite no clinical evidence of it being an effective treatment.

”Anecdotally, I can say that many patients have told me that marijuana is the only thing that makes them feel better in the first trimester, but that could also be closely tied to marijuana alleviating their other symptoms, such as anxiety or sleep disturbances,” Ilina Pluym, MD, of the department of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. ”In the brain, marijuana acts to alleviate nausea and vomiting, and it has been used successfully to treat nausea [caused by] chemotherapy,” said Dr. Pluym, who attended the abstract presentation but was not involved in the research. “But in the gut, with long-term marijuana use, it can have the opposite effect, which is what is seen in cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.”

Past research that has identified a link between cannabis use and nausea in pregnancy has typically relied on administrative data or self-reporting that are subject to recall and social desirability bias instead of a biomarker to assess cannabis use. This study therefore assessed marijuana use based on the presence of THC-COOH in urine samples and added the element of investigating antiemetic use in the population.

The study enrolled 10,038 nulliparous pregnant patients from eight U.S. centers from 2010 to 2013 who were an average 11 weeks pregnant. All participants completed the Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) tool at their first study visit and consented to testing of their previously frozen urine samples. The PUQE tool asks participants how often they have experienced nausea, vomiting, or retching or dry heaves within the previous 12 hours. A score of 1-6 is mild, a score of 7-12 is moderate, and a score of 13 or higher is severe.

Overall, 15.8% of participants reported moderate to severe nausea and 38.2% reported mild nausea. A total of 5.8% of participants tested positive for marijuana use based on THC levels in urine. Those with incrementally higher levels of THC, at least 500 ng/mg of creatinine, were 1.6 times more likely to report moderate to severe nausea after accounting for maternal age, body mass index, antiemetic drug use, and gestational age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.6; P < .001). An association did not exist, however, with any level of nausea overall. Those with higher creatinine levels were also 1.9 times more likely to report vomiting and 1.6 times more likely to report dry heaves or retching (P < .001).

About 1 in 10 participants (9.6%) overall had used a prescription antiemetic drug. Antiemetics were more common among those who had used marijuana: 18% of those with detectable THC had used antiemetics, compared with 12% of those without evidence of cannabis use (P < .001). However, most of those who used marijuana (83%) took only one antiemetic.

Among the study’s limitations were its lack of data on the reasons for cannabis use and the fact that it took place before widespread cannabidiol products became available, which meant most participants were using marijuana by smoking it.

Dr. Pluym also pointed out that the overall rate of marijuana use during pregnancy is likely higher today than it was in 2010-2013, before many states legalized its use. “But legalization shouldn’t equal normalization in pregnancy,” she added.

In addition, while the PUQE score assesses symptoms within the previous 12 hours, THC can remain in urine samples anywhere from several days to several weeks after marijuana is used.

”We’re unable to establish cause and effect,” Dr. Metz said, “but what we can conclude is that marijuana use was associated with early pregnancy nausea and vomiting.”

The findings emphasize the need for physicians to ask patients about their use of marijuana and seek to find out why they’re using it, Dr. Metz said. If it’s to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, ob.gyns. should ensure patients are aware of the potential adverse effects of marijuana use in pregnancy and mention safe, effective alternatives. Research from the National Academy of Sciences has shown consistent evidence of decreased fetal growth with marijuana use in pregnancy, but there hasn’t been enough evidence to assess potential long-term neurological effects.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Metz and Dr. Pluym reported no disclosures.

Use of marijuana during pregnancy was associated with symptoms of nausea and vomiting and with use of prescribed antiemetics, according to a study presented Feb. 3 at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. It’s unclear, however, whether the association suggests that pregnant individuals are using marijuana in an attempt to treat their symptoms or whether the marijuana use is contributing to nausea and vomiting – or neither, Torri D. Metz, MD, of the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, told attendees.

“Cannabis use has been increasing among pregnant individuals,” Dr. Metz said. “Reported reasons for use range from habit to perceived benefit for treatment of medical conditions, including nausea and vomiting.” She noted a previous study that found that dispensary employees in Colorado recommended cannabis to pregnant callers for treating of nausea despite no clinical evidence of it being an effective treatment.

”Anecdotally, I can say that many patients have told me that marijuana is the only thing that makes them feel better in the first trimester, but that could also be closely tied to marijuana alleviating their other symptoms, such as anxiety or sleep disturbances,” Ilina Pluym, MD, of the department of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. ”In the brain, marijuana acts to alleviate nausea and vomiting, and it has been used successfully to treat nausea [caused by] chemotherapy,” said Dr. Pluym, who attended the abstract presentation but was not involved in the research. “But in the gut, with long-term marijuana use, it can have the opposite effect, which is what is seen in cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.”

Past research that has identified a link between cannabis use and nausea in pregnancy has typically relied on administrative data or self-reporting that are subject to recall and social desirability bias instead of a biomarker to assess cannabis use. This study therefore assessed marijuana use based on the presence of THC-COOH in urine samples and added the element of investigating antiemetic use in the population.

The study enrolled 10,038 nulliparous pregnant patients from eight U.S. centers from 2010 to 2013 who were an average 11 weeks pregnant. All participants completed the Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) tool at their first study visit and consented to testing of their previously frozen urine samples. The PUQE tool asks participants how often they have experienced nausea, vomiting, or retching or dry heaves within the previous 12 hours. A score of 1-6 is mild, a score of 7-12 is moderate, and a score of 13 or higher is severe.

Overall, 15.8% of participants reported moderate to severe nausea and 38.2% reported mild nausea. A total of 5.8% of participants tested positive for marijuana use based on THC levels in urine. Those with incrementally higher levels of THC, at least 500 ng/mg of creatinine, were 1.6 times more likely to report moderate to severe nausea after accounting for maternal age, body mass index, antiemetic drug use, and gestational age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.6; P < .001). An association did not exist, however, with any level of nausea overall. Those with higher creatinine levels were also 1.9 times more likely to report vomiting and 1.6 times more likely to report dry heaves or retching (P < .001).

About 1 in 10 participants (9.6%) overall had used a prescription antiemetic drug. Antiemetics were more common among those who had used marijuana: 18% of those with detectable THC had used antiemetics, compared with 12% of those without evidence of cannabis use (P < .001). However, most of those who used marijuana (83%) took only one antiemetic.

Among the study’s limitations were its lack of data on the reasons for cannabis use and the fact that it took place before widespread cannabidiol products became available, which meant most participants were using marijuana by smoking it.

Dr. Pluym also pointed out that the overall rate of marijuana use during pregnancy is likely higher today than it was in 2010-2013, before many states legalized its use. “But legalization shouldn’t equal normalization in pregnancy,” she added.

In addition, while the PUQE score assesses symptoms within the previous 12 hours, THC can remain in urine samples anywhere from several days to several weeks after marijuana is used.

”We’re unable to establish cause and effect,” Dr. Metz said, “but what we can conclude is that marijuana use was associated with early pregnancy nausea and vomiting.”

The findings emphasize the need for physicians to ask patients about their use of marijuana and seek to find out why they’re using it, Dr. Metz said. If it’s to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, ob.gyns. should ensure patients are aware of the potential adverse effects of marijuana use in pregnancy and mention safe, effective alternatives. Research from the National Academy of Sciences has shown consistent evidence of decreased fetal growth with marijuana use in pregnancy, but there hasn’t been enough evidence to assess potential long-term neurological effects.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Metz and Dr. Pluym reported no disclosures.

Use of marijuana during pregnancy was associated with symptoms of nausea and vomiting and with use of prescribed antiemetics, according to a study presented Feb. 3 at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. It’s unclear, however, whether the association suggests that pregnant individuals are using marijuana in an attempt to treat their symptoms or whether the marijuana use is contributing to nausea and vomiting – or neither, Torri D. Metz, MD, of the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, told attendees.

“Cannabis use has been increasing among pregnant individuals,” Dr. Metz said. “Reported reasons for use range from habit to perceived benefit for treatment of medical conditions, including nausea and vomiting.” She noted a previous study that found that dispensary employees in Colorado recommended cannabis to pregnant callers for treating of nausea despite no clinical evidence of it being an effective treatment.

”Anecdotally, I can say that many patients have told me that marijuana is the only thing that makes them feel better in the first trimester, but that could also be closely tied to marijuana alleviating their other symptoms, such as anxiety or sleep disturbances,” Ilina Pluym, MD, of the department of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. ”In the brain, marijuana acts to alleviate nausea and vomiting, and it has been used successfully to treat nausea [caused by] chemotherapy,” said Dr. Pluym, who attended the abstract presentation but was not involved in the research. “But in the gut, with long-term marijuana use, it can have the opposite effect, which is what is seen in cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.”

Past research that has identified a link between cannabis use and nausea in pregnancy has typically relied on administrative data or self-reporting that are subject to recall and social desirability bias instead of a biomarker to assess cannabis use. This study therefore assessed marijuana use based on the presence of THC-COOH in urine samples and added the element of investigating antiemetic use in the population.

The study enrolled 10,038 nulliparous pregnant patients from eight U.S. centers from 2010 to 2013 who were an average 11 weeks pregnant. All participants completed the Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) tool at their first study visit and consented to testing of their previously frozen urine samples. The PUQE tool asks participants how often they have experienced nausea, vomiting, or retching or dry heaves within the previous 12 hours. A score of 1-6 is mild, a score of 7-12 is moderate, and a score of 13 or higher is severe.

Overall, 15.8% of participants reported moderate to severe nausea and 38.2% reported mild nausea. A total of 5.8% of participants tested positive for marijuana use based on THC levels in urine. Those with incrementally higher levels of THC, at least 500 ng/mg of creatinine, were 1.6 times more likely to report moderate to severe nausea after accounting for maternal age, body mass index, antiemetic drug use, and gestational age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.6; P < .001). An association did not exist, however, with any level of nausea overall. Those with higher creatinine levels were also 1.9 times more likely to report vomiting and 1.6 times more likely to report dry heaves or retching (P < .001).

About 1 in 10 participants (9.6%) overall had used a prescription antiemetic drug. Antiemetics were more common among those who had used marijuana: 18% of those with detectable THC had used antiemetics, compared with 12% of those without evidence of cannabis use (P < .001). However, most of those who used marijuana (83%) took only one antiemetic.

Among the study’s limitations were its lack of data on the reasons for cannabis use and the fact that it took place before widespread cannabidiol products became available, which meant most participants were using marijuana by smoking it.

Dr. Pluym also pointed out that the overall rate of marijuana use during pregnancy is likely higher today than it was in 2010-2013, before many states legalized its use. “But legalization shouldn’t equal normalization in pregnancy,” she added.

In addition, while the PUQE score assesses symptoms within the previous 12 hours, THC can remain in urine samples anywhere from several days to several weeks after marijuana is used.

”We’re unable to establish cause and effect,” Dr. Metz said, “but what we can conclude is that marijuana use was associated with early pregnancy nausea and vomiting.”

The findings emphasize the need for physicians to ask patients about their use of marijuana and seek to find out why they’re using it, Dr. Metz said. If it’s to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, ob.gyns. should ensure patients are aware of the potential adverse effects of marijuana use in pregnancy and mention safe, effective alternatives. Research from the National Academy of Sciences has shown consistent evidence of decreased fetal growth with marijuana use in pregnancy, but there hasn’t been enough evidence to assess potential long-term neurological effects.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Metz and Dr. Pluym reported no disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Intranasal oxytocin shows early promise for cocaine dependence

Intranasal oxytocin (INOT) is showing early promise as a treatment for cocaine dependence, new research suggests.

Results of a small 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with cocaine use disorder showed a high level of abstinence in those who received INOT beginning 2 weeks after treatment initiation.

“In this population of cocaine-dependent individuals in a community clinic setting, , compared to placebo,” lead author Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, a Teaneck, N.J.–based psychiatrist, said in an interview.

On the other hand, “the findings were paradoxical because there was a greater dropout rate in the intranasal oxytocin group after week 1, suggesting that oxytocin might have a biphasic effect, which should be addressed in future studies,” added Dr. Raby, who was an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, division on substance abuse, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, when the trial was conducted.

The study was published in the March issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports.

‘Crying need’

“Focus on stress reactivity in addiction and on the loss of social norms among drug users has generated interest in oxytocin, due to its purported role in these traits and regulation of stress,” the authors wrote.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that regulates autonomic functions. Previous research in cannabis users suggests it may have a role in treating addiction by reportedly reducing cravings. In addition, earlier research also suggests it cuts stress reactivity and state anger in cocaine users.

A previous trial of INOT showed it decreased cocaine craving, and additional research has revealed recurrent cocaine use results in lower endogenous oxytocin levels and depleted oxytocin in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

“The bias of my work is to look for simple, nonaddictive medicinal approaches that can be used in the community settings, because that’s where the greatest crying need lies and where most problems from drug addiction occur,” said Dr. Raby.

“There has been long-standing interest in how the brain adaptive systems, or so-called ‘stress systems,’ adjust in the face of drug dependence in general, and the main focus of the study has been to understand this response and use the insight from these adaptations to develop medicinal treatments for drug abuse, particularly cocaine dependence,” he added.

To investigate the potential for INOT to promote abstinence from cocaine, the researchers randomized 26 patients with cocaine use disorder (73% male, mean [SD] age, 50.2 [5.4] years). Most participants had been using cocaine on a regular basis for about 25 years, and baseline average days of cocaine use was 11.1 (5.7) during the 30 days prior to study entry.

At a baseline, the researchers collected participants’ medical history and conducted a physical examination, urine toxicology, electrocardiogram, comprehensive metabolic panel, and complete blood count. They used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview to confirm the diagnosis of cocaine dependence.

The study began with a 7-day inpatient abstinence induction stage, after which participants were randomized to receive either INOT 24 IU or intranasal placebo (n = 15 and n = 11, respectively).

Patients attended the clinic three times per week. At each visit, they completed the cocaine craving scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Clinician Global Inventory (all self-reports), as well as the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB) to document cocaine use.

Participants were trained to self-administer an intranasal solution at home, with compliance monitored in two ways – staff observed self-administration of the randomized medication at the time of clinic visits and weighed the “at home bottle.”

Cocaine use was determined via urine toxicology and TLFB self-report.

Threshold period

INOT did not induce ≥ 3 weeks of continuous abstinence. However, beginning with week 3, the odds of weekly abstinence increased dramatically in the INOT group, from 4.61 (95% confidence interval,1.05, 20.3) to 15.0 (1.18, 190.2) by week 6 (t = 2.12, P = .037).

The overall medication group by time interaction across all 6 weeks was not significant (F1,69 = 1.73, P = .19); but when the interaction was removed, the difference between the overall effect of medication (INOT vs. placebo) over all 6 weeks “reached trend-level significance” (F1,70) = 3.42, P = .07).

The subjective rating outcomes (cravings, perceived stress, cocaine dependence, and depression) “did not show a significant medication group by time interaction effect,” the authors reported, although stress-induced cravings did tend toward a significant difference between the groups.

Half of the patients did not complete the full 6 weeks. Of those who discontinued, 85% came from the INOT group and 15% from the placebo group. Of the 11 who dropped out from the treatment group, seven were abstinent at the time of discontinuation for ≥ 1 week.

There were no significant differences in rates of reported side effects between the two groups.

“This study highlights some promise that perhaps there is a threshold period of time you need to cross, after which time oxytocin could really be really helpful as acute or maintenance medication,” said Dr. Raby. The short study duration might have been a disadvantage. “We might have seen better results if the study had been 8 or 12 weeks in duration.”

Using motivational approaches during the early phase – e.g., psychotherapy or a voucher system – might increase adherence, and then “after this initial lag, we might see a more therapeutic effect,” he suggested.

Dr. Raby noted that his group studied stress hormone secretions in the cocaine-dependent study participants during the 7-day induction period and that the findings, when published, could shed light on this latency period. “Cocaine dependence creates adaptations in the stress system,” he said.

‘Nice first step’

Commenting on the study, Jane Joseph, PhD, professor in the department of neurosciences and director of the neuroimaging division at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said it is “nice to see a clinical trial using oxytocin in cocaine dependence [because] preclinical research has shown fairly convincing effects of oxytocin in reducing craving or stress in the context of cocaine seeking, but findings are rather mixed in human studies.”

Dr. Joseph, who was not involved with the study, said her group’s research showed oxytocin to be the most helpful for men with cocaine use disorder who reported childhood trauma, while for women, oxytocin “seemed to worsen their reactivity to cocaine cues.”

She said the current study is a “nice first step” and suggested that future research should include larger sample sizes to “address some of the individual variability in the response to oxytocin by examining sex differences or trauma history.”

The study was supported by an award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Raby and coauthors and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intranasal oxytocin (INOT) is showing early promise as a treatment for cocaine dependence, new research suggests.

Results of a small 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with cocaine use disorder showed a high level of abstinence in those who received INOT beginning 2 weeks after treatment initiation.

“In this population of cocaine-dependent individuals in a community clinic setting, , compared to placebo,” lead author Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, a Teaneck, N.J.–based psychiatrist, said in an interview.

On the other hand, “the findings were paradoxical because there was a greater dropout rate in the intranasal oxytocin group after week 1, suggesting that oxytocin might have a biphasic effect, which should be addressed in future studies,” added Dr. Raby, who was an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, division on substance abuse, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, when the trial was conducted.

The study was published in the March issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports.

‘Crying need’

“Focus on stress reactivity in addiction and on the loss of social norms among drug users has generated interest in oxytocin, due to its purported role in these traits and regulation of stress,” the authors wrote.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that regulates autonomic functions. Previous research in cannabis users suggests it may have a role in treating addiction by reportedly reducing cravings. In addition, earlier research also suggests it cuts stress reactivity and state anger in cocaine users.

A previous trial of INOT showed it decreased cocaine craving, and additional research has revealed recurrent cocaine use results in lower endogenous oxytocin levels and depleted oxytocin in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

“The bias of my work is to look for simple, nonaddictive medicinal approaches that can be used in the community settings, because that’s where the greatest crying need lies and where most problems from drug addiction occur,” said Dr. Raby.

“There has been long-standing interest in how the brain adaptive systems, or so-called ‘stress systems,’ adjust in the face of drug dependence in general, and the main focus of the study has been to understand this response and use the insight from these adaptations to develop medicinal treatments for drug abuse, particularly cocaine dependence,” he added.

To investigate the potential for INOT to promote abstinence from cocaine, the researchers randomized 26 patients with cocaine use disorder (73% male, mean [SD] age, 50.2 [5.4] years). Most participants had been using cocaine on a regular basis for about 25 years, and baseline average days of cocaine use was 11.1 (5.7) during the 30 days prior to study entry.

At a baseline, the researchers collected participants’ medical history and conducted a physical examination, urine toxicology, electrocardiogram, comprehensive metabolic panel, and complete blood count. They used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview to confirm the diagnosis of cocaine dependence.

The study began with a 7-day inpatient abstinence induction stage, after which participants were randomized to receive either INOT 24 IU or intranasal placebo (n = 15 and n = 11, respectively).

Patients attended the clinic three times per week. At each visit, they completed the cocaine craving scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Clinician Global Inventory (all self-reports), as well as the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB) to document cocaine use.

Participants were trained to self-administer an intranasal solution at home, with compliance monitored in two ways – staff observed self-administration of the randomized medication at the time of clinic visits and weighed the “at home bottle.”

Cocaine use was determined via urine toxicology and TLFB self-report.

Threshold period

INOT did not induce ≥ 3 weeks of continuous abstinence. However, beginning with week 3, the odds of weekly abstinence increased dramatically in the INOT group, from 4.61 (95% confidence interval,1.05, 20.3) to 15.0 (1.18, 190.2) by week 6 (t = 2.12, P = .037).

The overall medication group by time interaction across all 6 weeks was not significant (F1,69 = 1.73, P = .19); but when the interaction was removed, the difference between the overall effect of medication (INOT vs. placebo) over all 6 weeks “reached trend-level significance” (F1,70) = 3.42, P = .07).

The subjective rating outcomes (cravings, perceived stress, cocaine dependence, and depression) “did not show a significant medication group by time interaction effect,” the authors reported, although stress-induced cravings did tend toward a significant difference between the groups.

Half of the patients did not complete the full 6 weeks. Of those who discontinued, 85% came from the INOT group and 15% from the placebo group. Of the 11 who dropped out from the treatment group, seven were abstinent at the time of discontinuation for ≥ 1 week.

There were no significant differences in rates of reported side effects between the two groups.

“This study highlights some promise that perhaps there is a threshold period of time you need to cross, after which time oxytocin could really be really helpful as acute or maintenance medication,” said Dr. Raby. The short study duration might have been a disadvantage. “We might have seen better results if the study had been 8 or 12 weeks in duration.”

Using motivational approaches during the early phase – e.g., psychotherapy or a voucher system – might increase adherence, and then “after this initial lag, we might see a more therapeutic effect,” he suggested.

Dr. Raby noted that his group studied stress hormone secretions in the cocaine-dependent study participants during the 7-day induction period and that the findings, when published, could shed light on this latency period. “Cocaine dependence creates adaptations in the stress system,” he said.

‘Nice first step’

Commenting on the study, Jane Joseph, PhD, professor in the department of neurosciences and director of the neuroimaging division at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said it is “nice to see a clinical trial using oxytocin in cocaine dependence [because] preclinical research has shown fairly convincing effects of oxytocin in reducing craving or stress in the context of cocaine seeking, but findings are rather mixed in human studies.”

Dr. Joseph, who was not involved with the study, said her group’s research showed oxytocin to be the most helpful for men with cocaine use disorder who reported childhood trauma, while for women, oxytocin “seemed to worsen their reactivity to cocaine cues.”

She said the current study is a “nice first step” and suggested that future research should include larger sample sizes to “address some of the individual variability in the response to oxytocin by examining sex differences or trauma history.”

The study was supported by an award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Raby and coauthors and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intranasal oxytocin (INOT) is showing early promise as a treatment for cocaine dependence, new research suggests.

Results of a small 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with cocaine use disorder showed a high level of abstinence in those who received INOT beginning 2 weeks after treatment initiation.

“In this population of cocaine-dependent individuals in a community clinic setting, , compared to placebo,” lead author Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, a Teaneck, N.J.–based psychiatrist, said in an interview.

On the other hand, “the findings were paradoxical because there was a greater dropout rate in the intranasal oxytocin group after week 1, suggesting that oxytocin might have a biphasic effect, which should be addressed in future studies,” added Dr. Raby, who was an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, division on substance abuse, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, when the trial was conducted.

The study was published in the March issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports.

‘Crying need’

“Focus on stress reactivity in addiction and on the loss of social norms among drug users has generated interest in oxytocin, due to its purported role in these traits and regulation of stress,” the authors wrote.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that regulates autonomic functions. Previous research in cannabis users suggests it may have a role in treating addiction by reportedly reducing cravings. In addition, earlier research also suggests it cuts stress reactivity and state anger in cocaine users.

A previous trial of INOT showed it decreased cocaine craving, and additional research has revealed recurrent cocaine use results in lower endogenous oxytocin levels and depleted oxytocin in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

“The bias of my work is to look for simple, nonaddictive medicinal approaches that can be used in the community settings, because that’s where the greatest crying need lies and where most problems from drug addiction occur,” said Dr. Raby.

“There has been long-standing interest in how the brain adaptive systems, or so-called ‘stress systems,’ adjust in the face of drug dependence in general, and the main focus of the study has been to understand this response and use the insight from these adaptations to develop medicinal treatments for drug abuse, particularly cocaine dependence,” he added.

To investigate the potential for INOT to promote abstinence from cocaine, the researchers randomized 26 patients with cocaine use disorder (73% male, mean [SD] age, 50.2 [5.4] years). Most participants had been using cocaine on a regular basis for about 25 years, and baseline average days of cocaine use was 11.1 (5.7) during the 30 days prior to study entry.

At a baseline, the researchers collected participants’ medical history and conducted a physical examination, urine toxicology, electrocardiogram, comprehensive metabolic panel, and complete blood count. They used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview to confirm the diagnosis of cocaine dependence.

The study began with a 7-day inpatient abstinence induction stage, after which participants were randomized to receive either INOT 24 IU or intranasal placebo (n = 15 and n = 11, respectively).

Patients attended the clinic three times per week. At each visit, they completed the cocaine craving scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Clinician Global Inventory (all self-reports), as well as the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB) to document cocaine use.

Participants were trained to self-administer an intranasal solution at home, with compliance monitored in two ways – staff observed self-administration of the randomized medication at the time of clinic visits and weighed the “at home bottle.”

Cocaine use was determined via urine toxicology and TLFB self-report.

Threshold period

INOT did not induce ≥ 3 weeks of continuous abstinence. However, beginning with week 3, the odds of weekly abstinence increased dramatically in the INOT group, from 4.61 (95% confidence interval,1.05, 20.3) to 15.0 (1.18, 190.2) by week 6 (t = 2.12, P = .037).

The overall medication group by time interaction across all 6 weeks was not significant (F1,69 = 1.73, P = .19); but when the interaction was removed, the difference between the overall effect of medication (INOT vs. placebo) over all 6 weeks “reached trend-level significance” (F1,70) = 3.42, P = .07).

The subjective rating outcomes (cravings, perceived stress, cocaine dependence, and depression) “did not show a significant medication group by time interaction effect,” the authors reported, although stress-induced cravings did tend toward a significant difference between the groups.

Half of the patients did not complete the full 6 weeks. Of those who discontinued, 85% came from the INOT group and 15% from the placebo group. Of the 11 who dropped out from the treatment group, seven were abstinent at the time of discontinuation for ≥ 1 week.

There were no significant differences in rates of reported side effects between the two groups.

“This study highlights some promise that perhaps there is a threshold period of time you need to cross, after which time oxytocin could really be really helpful as acute or maintenance medication,” said Dr. Raby. The short study duration might have been a disadvantage. “We might have seen better results if the study had been 8 or 12 weeks in duration.”

Using motivational approaches during the early phase – e.g., psychotherapy or a voucher system – might increase adherence, and then “after this initial lag, we might see a more therapeutic effect,” he suggested.

Dr. Raby noted that his group studied stress hormone secretions in the cocaine-dependent study participants during the 7-day induction period and that the findings, when published, could shed light on this latency period. “Cocaine dependence creates adaptations in the stress system,” he said.

‘Nice first step’

Commenting on the study, Jane Joseph, PhD, professor in the department of neurosciences and director of the neuroimaging division at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said it is “nice to see a clinical trial using oxytocin in cocaine dependence [because] preclinical research has shown fairly convincing effects of oxytocin in reducing craving or stress in the context of cocaine seeking, but findings are rather mixed in human studies.”

Dr. Joseph, who was not involved with the study, said her group’s research showed oxytocin to be the most helpful for men with cocaine use disorder who reported childhood trauma, while for women, oxytocin “seemed to worsen their reactivity to cocaine cues.”

She said the current study is a “nice first step” and suggested that future research should include larger sample sizes to “address some of the individual variability in the response to oxytocin by examining sex differences or trauma history.”

The study was supported by an award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Raby and coauthors and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DRUG AND ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE REPORTS

Naloxone Dispensing in Patients at Risk for Opioid Overdose After Total Knee Arthroplasty Within the Veterans Health Administration

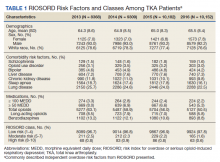

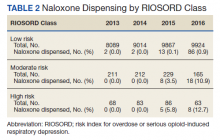

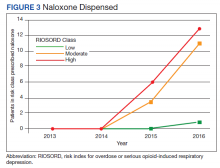

Opioid overdose is a major public health challenge, with recent reports estimating 41 deaths per day in the United States from prescription opioid overdose.1,2 Prescribing naloxone has increasingly been advocated to reduce the risk of opioid overdose for patients identified as high risk. Naloxone distribution has been shown to decrease the incidence of opioid overdoses in the general population.3,4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends considering naloxone prescription for patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, opioid dosages ≥ 50 morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and concurrent use of benzodiazepines.5