User login

‘Deeper dive’ into opioid overdose deaths during COVID pandemic

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

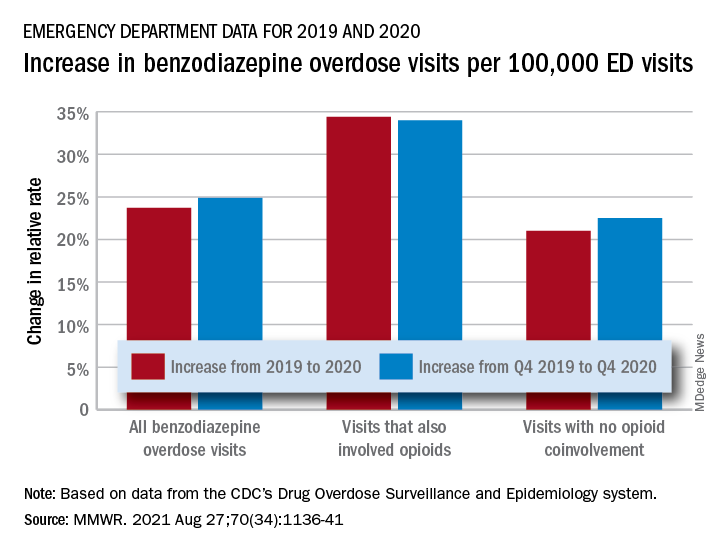

EDs saw more benzodiazepine overdoses, but fewer patients overall, in 2020

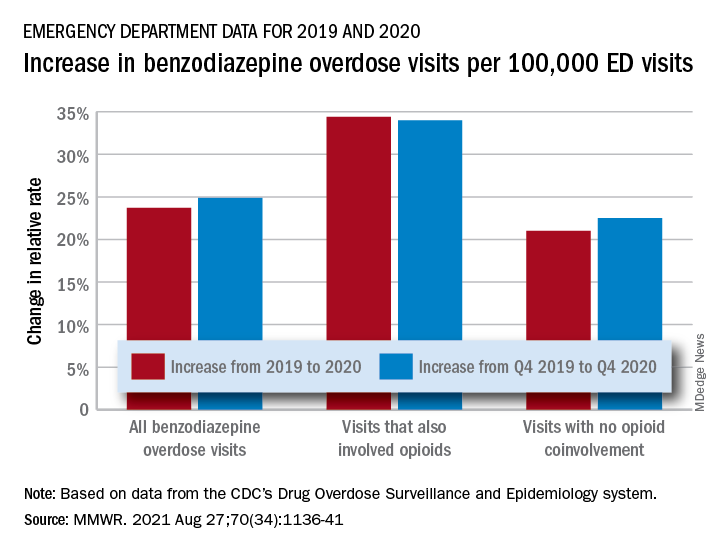

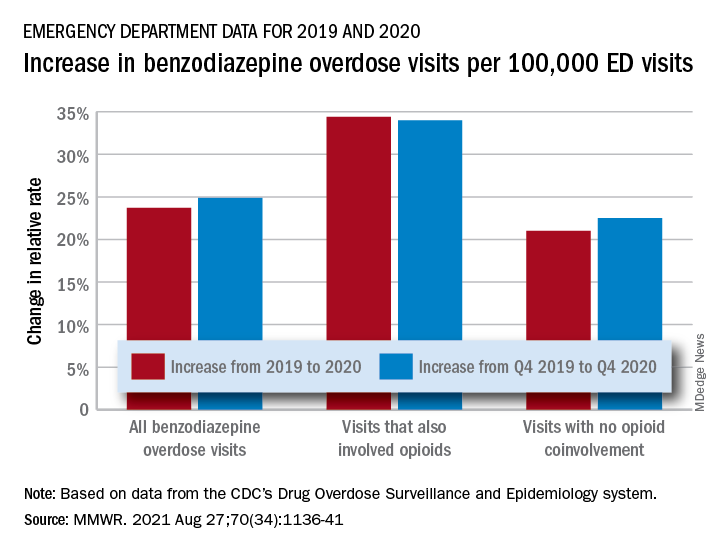

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

Self-described ‘assassin,’ now doctor, indicted for 1M illegal opioid doses

A according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The substances include oxycodone and morphine.

Adrian Dexter Talbot, MD, 55, of Slidell, La., is also charged with maintaining a medical clinic for the purpose of illegally distributing controlled substances, per the indictment.

Because the opioid prescriptions were filled using beneficiaries’ health insurance, Dr. Talbot is also charged with defrauding Medicare, Medicaid, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana of more than $5.1 million.

When contacted by this news organization for comment on the case via Twitter, Dr. Talbot or a representative responded with a link to his self-published book on Amazon. In his author bio, Dr. Talbot refers to himself as “a former assassin,” “retired military commander,” and “leader of the Medellin Cartel’s New York operations at the age of 16.” The Medellin Cartel is a notorious drug distribution empire.

Dr. Talbot is listed as the author of another book on Google Books detailing his time as a “former teenage assassin” and leader of the cartel, told as he struggles with early onset Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Talbot could spend decades in prison

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 444 residents of the Bayou State lost their lives because of an opioid-related drug overdose in 2018. During that year, the state’s health care providers wrote more than 79.4 opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, which puts the state in the top five in the United States in 2018, when the average U.S. rate was 51.4 prescriptions per 100 persons.

Charged with one count each of conspiracy to unlawfully distribute and dispense controlled substances and maintaining drug-involved premises and conspiracy to commit health care fraud, Dr. Talbot is also charged with four counts of unlawfully distributing and dispensing controlled substances. He is scheduled for a federal court appearance on September 10.

In addition to presigning prescriptions for individuals he didn’t meet or examine, federal officials allege Dr. Talbot hired another health care provider to similarly presign prescriptions for people who weren’t examined at a medical practice in Slidell, where Dr. Talbot was employed. The DOJ says Dr. Talbot took a full-time job in Pineville, La., and presigned prescriptions while no longer physically present at the Slidell clinic.

A speaker’s bio for Dr. Talbot indicates he worked as chief of medical services for the Alexandria Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Pineville.

According to the DOJ’s indictment, Dr. Talbot was aware that patients were filling the prescriptions that were provided outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose. This is what triggered the DOJ’s fraudulent billing claim.

Dr. Talbot faces a maximum penalty of 10 years for conspiracy to commit health care fraud and 20 years each for the other counts, if convicted.

Dr. Talbot was candidate for local coroner

In February 2015, Dr. Talbot announced his candidacy for coroner for St. Tammany Parish, about an hour’s drive south of New Orleans, reported the Times Picayune. The seat was open because the previous coroner had resigned and ultimately pleaded guilty to a federal corruption charge.

The Times Picayune reported at the time that Dr. Talbot was a U.S. Navy veteran, in addition to serving as medical director and a primary care physician at the Medical Care Center in Slidell. Among the services provided to his patients were evaluations and treatment for substance use and mental health disorders, according to a press release issued by Dr. Talbot’s campaign.

Dr. Talbot’s medical license was issued in 1999 and inactive as of 2017, per the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners.

Louisiana expects $325M in multistate settlement with opioid companies

Louisiana is a party to a multistate and multijurisdictional lawsuit where the state is expected to receive more than $325 million in a settlement reached with drug distributors Cardinal, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen, and drug manufacturer Johnson & Johnson, reported the Louisiana Illuminator in July. The total settlement may reach $26 billion dollars.

The Associated Press reported in July that there have been at least $40 billion in completed or proposed settlements, penalties, and fines between governments as a result of the opioid epidemic since 2007.

That total doesn’t include a proposed settlement involving members of the Sackler family, who own Purdue Pharmaceuticals, which manufactured and marketed the opioid painkiller OxyContin. The Sackler family have agreed to pay approximately $4.3 billion and surrender ownership of their bankrupt company, reported NPR. The family’s proposed settlement is part of a deal involving Purdue Pharmaceuticals worth more than $10 billion, reported Reuters.

In 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths, the highest number recorded in a 12-month period, per the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fentanyl, an illicitly manufactured synthetic opioid, was the lead driver of those deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The substances include oxycodone and morphine.

Adrian Dexter Talbot, MD, 55, of Slidell, La., is also charged with maintaining a medical clinic for the purpose of illegally distributing controlled substances, per the indictment.

Because the opioid prescriptions were filled using beneficiaries’ health insurance, Dr. Talbot is also charged with defrauding Medicare, Medicaid, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana of more than $5.1 million.

When contacted by this news organization for comment on the case via Twitter, Dr. Talbot or a representative responded with a link to his self-published book on Amazon. In his author bio, Dr. Talbot refers to himself as “a former assassin,” “retired military commander,” and “leader of the Medellin Cartel’s New York operations at the age of 16.” The Medellin Cartel is a notorious drug distribution empire.

Dr. Talbot is listed as the author of another book on Google Books detailing his time as a “former teenage assassin” and leader of the cartel, told as he struggles with early onset Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Talbot could spend decades in prison

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 444 residents of the Bayou State lost their lives because of an opioid-related drug overdose in 2018. During that year, the state’s health care providers wrote more than 79.4 opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, which puts the state in the top five in the United States in 2018, when the average U.S. rate was 51.4 prescriptions per 100 persons.

Charged with one count each of conspiracy to unlawfully distribute and dispense controlled substances and maintaining drug-involved premises and conspiracy to commit health care fraud, Dr. Talbot is also charged with four counts of unlawfully distributing and dispensing controlled substances. He is scheduled for a federal court appearance on September 10.

In addition to presigning prescriptions for individuals he didn’t meet or examine, federal officials allege Dr. Talbot hired another health care provider to similarly presign prescriptions for people who weren’t examined at a medical practice in Slidell, where Dr. Talbot was employed. The DOJ says Dr. Talbot took a full-time job in Pineville, La., and presigned prescriptions while no longer physically present at the Slidell clinic.

A speaker’s bio for Dr. Talbot indicates he worked as chief of medical services for the Alexandria Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Pineville.

According to the DOJ’s indictment, Dr. Talbot was aware that patients were filling the prescriptions that were provided outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose. This is what triggered the DOJ’s fraudulent billing claim.

Dr. Talbot faces a maximum penalty of 10 years for conspiracy to commit health care fraud and 20 years each for the other counts, if convicted.

Dr. Talbot was candidate for local coroner

In February 2015, Dr. Talbot announced his candidacy for coroner for St. Tammany Parish, about an hour’s drive south of New Orleans, reported the Times Picayune. The seat was open because the previous coroner had resigned and ultimately pleaded guilty to a federal corruption charge.

The Times Picayune reported at the time that Dr. Talbot was a U.S. Navy veteran, in addition to serving as medical director and a primary care physician at the Medical Care Center in Slidell. Among the services provided to his patients were evaluations and treatment for substance use and mental health disorders, according to a press release issued by Dr. Talbot’s campaign.

Dr. Talbot’s medical license was issued in 1999 and inactive as of 2017, per the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners.

Louisiana expects $325M in multistate settlement with opioid companies

Louisiana is a party to a multistate and multijurisdictional lawsuit where the state is expected to receive more than $325 million in a settlement reached with drug distributors Cardinal, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen, and drug manufacturer Johnson & Johnson, reported the Louisiana Illuminator in July. The total settlement may reach $26 billion dollars.

The Associated Press reported in July that there have been at least $40 billion in completed or proposed settlements, penalties, and fines between governments as a result of the opioid epidemic since 2007.

That total doesn’t include a proposed settlement involving members of the Sackler family, who own Purdue Pharmaceuticals, which manufactured and marketed the opioid painkiller OxyContin. The Sackler family have agreed to pay approximately $4.3 billion and surrender ownership of their bankrupt company, reported NPR. The family’s proposed settlement is part of a deal involving Purdue Pharmaceuticals worth more than $10 billion, reported Reuters.

In 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths, the highest number recorded in a 12-month period, per the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fentanyl, an illicitly manufactured synthetic opioid, was the lead driver of those deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The substances include oxycodone and morphine.

Adrian Dexter Talbot, MD, 55, of Slidell, La., is also charged with maintaining a medical clinic for the purpose of illegally distributing controlled substances, per the indictment.

Because the opioid prescriptions were filled using beneficiaries’ health insurance, Dr. Talbot is also charged with defrauding Medicare, Medicaid, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana of more than $5.1 million.

When contacted by this news organization for comment on the case via Twitter, Dr. Talbot or a representative responded with a link to his self-published book on Amazon. In his author bio, Dr. Talbot refers to himself as “a former assassin,” “retired military commander,” and “leader of the Medellin Cartel’s New York operations at the age of 16.” The Medellin Cartel is a notorious drug distribution empire.

Dr. Talbot is listed as the author of another book on Google Books detailing his time as a “former teenage assassin” and leader of the cartel, told as he struggles with early onset Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Talbot could spend decades in prison

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 444 residents of the Bayou State lost their lives because of an opioid-related drug overdose in 2018. During that year, the state’s health care providers wrote more than 79.4 opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, which puts the state in the top five in the United States in 2018, when the average U.S. rate was 51.4 prescriptions per 100 persons.

Charged with one count each of conspiracy to unlawfully distribute and dispense controlled substances and maintaining drug-involved premises and conspiracy to commit health care fraud, Dr. Talbot is also charged with four counts of unlawfully distributing and dispensing controlled substances. He is scheduled for a federal court appearance on September 10.

In addition to presigning prescriptions for individuals he didn’t meet or examine, federal officials allege Dr. Talbot hired another health care provider to similarly presign prescriptions for people who weren’t examined at a medical practice in Slidell, where Dr. Talbot was employed. The DOJ says Dr. Talbot took a full-time job in Pineville, La., and presigned prescriptions while no longer physically present at the Slidell clinic.

A speaker’s bio for Dr. Talbot indicates he worked as chief of medical services for the Alexandria Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Pineville.

According to the DOJ’s indictment, Dr. Talbot was aware that patients were filling the prescriptions that were provided outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose. This is what triggered the DOJ’s fraudulent billing claim.

Dr. Talbot faces a maximum penalty of 10 years for conspiracy to commit health care fraud and 20 years each for the other counts, if convicted.

Dr. Talbot was candidate for local coroner

In February 2015, Dr. Talbot announced his candidacy for coroner for St. Tammany Parish, about an hour’s drive south of New Orleans, reported the Times Picayune. The seat was open because the previous coroner had resigned and ultimately pleaded guilty to a federal corruption charge.

The Times Picayune reported at the time that Dr. Talbot was a U.S. Navy veteran, in addition to serving as medical director and a primary care physician at the Medical Care Center in Slidell. Among the services provided to his patients were evaluations and treatment for substance use and mental health disorders, according to a press release issued by Dr. Talbot’s campaign.

Dr. Talbot’s medical license was issued in 1999 and inactive as of 2017, per the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners.

Louisiana expects $325M in multistate settlement with opioid companies

Louisiana is a party to a multistate and multijurisdictional lawsuit where the state is expected to receive more than $325 million in a settlement reached with drug distributors Cardinal, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen, and drug manufacturer Johnson & Johnson, reported the Louisiana Illuminator in July. The total settlement may reach $26 billion dollars.

The Associated Press reported in July that there have been at least $40 billion in completed or proposed settlements, penalties, and fines between governments as a result of the opioid epidemic since 2007.

That total doesn’t include a proposed settlement involving members of the Sackler family, who own Purdue Pharmaceuticals, which manufactured and marketed the opioid painkiller OxyContin. The Sackler family have agreed to pay approximately $4.3 billion and surrender ownership of their bankrupt company, reported NPR. The family’s proposed settlement is part of a deal involving Purdue Pharmaceuticals worth more than $10 billion, reported Reuters.

In 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths, the highest number recorded in a 12-month period, per the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fentanyl, an illicitly manufactured synthetic opioid, was the lead driver of those deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alcohol use by young adolescents drops during pandemic

The restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic altered patterns of substance use by early adolescents to less alcohol use and greater use and misuse of nicotine and prescription drugs, based on data from more than 7,000 youth aged 10-14 years.

Substance use in early adolescence is a function of many environmental factors including substance availability, parent and peer use, and family function, as well as macroeconomic factors, William E. Pelham III, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues wrote. “Thus, it is critical to evaluate how substance use during early adolescence has been impacted by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, a source of large and sustained disruptions to adolescents’ daily lives in terms of education, contact with family/friends, and health behaviors.”

In a prospective, community-based cohort study, published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers conducted a three-wave assessment of substance use between May 2020 and August 2020, and reviewed prepandemic assessments from 2018 to 2019. The participants included 7,842 adolescents with an average age of 12 years who were initially enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study at age 9-10 years. At the start of the study, 48% of the participants were female, 20% were Hispanic, 15% were Black, and 2% were Asian. Participants completed three online surveys between May 2020 and August 2020.

Each survey included the number of days in the past 30 days in which the adolescents drank alcohol; smoked cigarettes; used electronic nicotine delivery systems; smoked a cigar, hookah, or pipe; used smokeless tobacco products; used a cannabis product; abused prescription drugs; used inhalants; or used any other drugs. The response scale was 0 days to 10-plus days.

The overall prevalence of substance use among young adolescents was similar between prepandemic and pandemic periods; however fewer respondents reported using alcohol, but more reported using nicotine or misusing prescription medications.

Across all three survey periods, 7.4% of youth reported any substance use, 3.4% reported ever using alcohol, and 3.2% reported ever using nicotine. Of those who reported substance use, 79% reported 1-2 days of use in the past month, and 87% reported using a single substance.

In comparing prepandemic and pandemic substance use, the prevalence of alcohol use in the past 30 days decreased significantly, from 2.1% to 0.8%. However, use of nicotine increased significantly from 0% to 1.3%, and misuse of prescription drugs increased significantly from 0% to 0.6%. “Changes in the rates of use of any substance, cannabis, or inhalants were not statistically significant,” the researchers wrote.

Sex and ethnicity were not associated with substance use during the pandemic, but rates of substance use were higher among youth whose parents were unmarried or had lower levels of education, and among those with preexisting externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Youth who reported higher levels of uncertainty related to COVID-19 were significantly more likely to report substance use; additionally, stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were positively association with any substance use during the pandemic survey periods. Youth whose parents experienced hardship or whose parents used alcohol or drugs also were more likely to report substance use.

“Stability in the overall rate of substance use in this cohort is reassuring given that the pandemic has brought increases in teens’ unoccupied time, stress, and loneliness, reduced access to support services, and disruptions to routines and family/parenting practices, all of which might be expected to have increased youth substance use,” the researchers noted. The findings do not explain the decreased alcohol use, but the researchers cited possible reasons for reduced alcohol use including lack of contact with friends and social activities, and greater supervision by parents.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the comparison of prepandemic and pandemic substance use in younger adolescents, which may not reflect changes in substance use in older adolescents. The study also could not establish causality, and did not account for the intensity of substance use, such as number of drinks, the researchers wrote. However, the results were strengthened by the longitudinal design and large, diverse study population, and the use of prepandemic assessments that allowed evaluation of changes over time.

Overall, the results highlight the importance of preexisting and acute risk protective factors in mitigating substance use in young adolescents, and suggest the potential of economic support for families and emotional support for youth as ways to reduce risk, the researchers concluded.

Predicting use and identifying risk factors

“It was important to conduct research at this time so we know how trends have changed during the pandemic,” Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said in an interview. The research helps clinicians “so we can better predict which substances our patients may be using, especially those with preexisting psychological conditions and those at socioeconomic disadvantage.

“I was surprised by the increased prescription drug use, but it make sense, as adolescents are at home more and may be illicitly using their parents medications,” Dr. Kinsella noted. “I think as they go back to school, trends will shift back to where they were as they will be spending more time with friends.” The take-home message to clinicians is the increased use of nicotine and prescription drugs during the pandemic, and future research should focus on substance use trends in 14- to 20-year-olds.

The ABCD study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the current study also received support from the National Science Foundation and Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kinsella had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic altered patterns of substance use by early adolescents to less alcohol use and greater use and misuse of nicotine and prescription drugs, based on data from more than 7,000 youth aged 10-14 years.

Substance use in early adolescence is a function of many environmental factors including substance availability, parent and peer use, and family function, as well as macroeconomic factors, William E. Pelham III, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues wrote. “Thus, it is critical to evaluate how substance use during early adolescence has been impacted by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, a source of large and sustained disruptions to adolescents’ daily lives in terms of education, contact with family/friends, and health behaviors.”

In a prospective, community-based cohort study, published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers conducted a three-wave assessment of substance use between May 2020 and August 2020, and reviewed prepandemic assessments from 2018 to 2019. The participants included 7,842 adolescents with an average age of 12 years who were initially enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study at age 9-10 years. At the start of the study, 48% of the participants were female, 20% were Hispanic, 15% were Black, and 2% were Asian. Participants completed three online surveys between May 2020 and August 2020.

Each survey included the number of days in the past 30 days in which the adolescents drank alcohol; smoked cigarettes; used electronic nicotine delivery systems; smoked a cigar, hookah, or pipe; used smokeless tobacco products; used a cannabis product; abused prescription drugs; used inhalants; or used any other drugs. The response scale was 0 days to 10-plus days.

The overall prevalence of substance use among young adolescents was similar between prepandemic and pandemic periods; however fewer respondents reported using alcohol, but more reported using nicotine or misusing prescription medications.

Across all three survey periods, 7.4% of youth reported any substance use, 3.4% reported ever using alcohol, and 3.2% reported ever using nicotine. Of those who reported substance use, 79% reported 1-2 days of use in the past month, and 87% reported using a single substance.

In comparing prepandemic and pandemic substance use, the prevalence of alcohol use in the past 30 days decreased significantly, from 2.1% to 0.8%. However, use of nicotine increased significantly from 0% to 1.3%, and misuse of prescription drugs increased significantly from 0% to 0.6%. “Changes in the rates of use of any substance, cannabis, or inhalants were not statistically significant,” the researchers wrote.

Sex and ethnicity were not associated with substance use during the pandemic, but rates of substance use were higher among youth whose parents were unmarried or had lower levels of education, and among those with preexisting externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Youth who reported higher levels of uncertainty related to COVID-19 were significantly more likely to report substance use; additionally, stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were positively association with any substance use during the pandemic survey periods. Youth whose parents experienced hardship or whose parents used alcohol or drugs also were more likely to report substance use.

“Stability in the overall rate of substance use in this cohort is reassuring given that the pandemic has brought increases in teens’ unoccupied time, stress, and loneliness, reduced access to support services, and disruptions to routines and family/parenting practices, all of which might be expected to have increased youth substance use,” the researchers noted. The findings do not explain the decreased alcohol use, but the researchers cited possible reasons for reduced alcohol use including lack of contact with friends and social activities, and greater supervision by parents.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the comparison of prepandemic and pandemic substance use in younger adolescents, which may not reflect changes in substance use in older adolescents. The study also could not establish causality, and did not account for the intensity of substance use, such as number of drinks, the researchers wrote. However, the results were strengthened by the longitudinal design and large, diverse study population, and the use of prepandemic assessments that allowed evaluation of changes over time.

Overall, the results highlight the importance of preexisting and acute risk protective factors in mitigating substance use in young adolescents, and suggest the potential of economic support for families and emotional support for youth as ways to reduce risk, the researchers concluded.

Predicting use and identifying risk factors

“It was important to conduct research at this time so we know how trends have changed during the pandemic,” Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said in an interview. The research helps clinicians “so we can better predict which substances our patients may be using, especially those with preexisting psychological conditions and those at socioeconomic disadvantage.

“I was surprised by the increased prescription drug use, but it make sense, as adolescents are at home more and may be illicitly using their parents medications,” Dr. Kinsella noted. “I think as they go back to school, trends will shift back to where they were as they will be spending more time with friends.” The take-home message to clinicians is the increased use of nicotine and prescription drugs during the pandemic, and future research should focus on substance use trends in 14- to 20-year-olds.

The ABCD study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the current study also received support from the National Science Foundation and Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kinsella had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic altered patterns of substance use by early adolescents to less alcohol use and greater use and misuse of nicotine and prescription drugs, based on data from more than 7,000 youth aged 10-14 years.

Substance use in early adolescence is a function of many environmental factors including substance availability, parent and peer use, and family function, as well as macroeconomic factors, William E. Pelham III, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues wrote. “Thus, it is critical to evaluate how substance use during early adolescence has been impacted by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, a source of large and sustained disruptions to adolescents’ daily lives in terms of education, contact with family/friends, and health behaviors.”

In a prospective, community-based cohort study, published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers conducted a three-wave assessment of substance use between May 2020 and August 2020, and reviewed prepandemic assessments from 2018 to 2019. The participants included 7,842 adolescents with an average age of 12 years who were initially enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study at age 9-10 years. At the start of the study, 48% of the participants were female, 20% were Hispanic, 15% were Black, and 2% were Asian. Participants completed three online surveys between May 2020 and August 2020.

Each survey included the number of days in the past 30 days in which the adolescents drank alcohol; smoked cigarettes; used electronic nicotine delivery systems; smoked a cigar, hookah, or pipe; used smokeless tobacco products; used a cannabis product; abused prescription drugs; used inhalants; or used any other drugs. The response scale was 0 days to 10-plus days.

The overall prevalence of substance use among young adolescents was similar between prepandemic and pandemic periods; however fewer respondents reported using alcohol, but more reported using nicotine or misusing prescription medications.

Across all three survey periods, 7.4% of youth reported any substance use, 3.4% reported ever using alcohol, and 3.2% reported ever using nicotine. Of those who reported substance use, 79% reported 1-2 days of use in the past month, and 87% reported using a single substance.

In comparing prepandemic and pandemic substance use, the prevalence of alcohol use in the past 30 days decreased significantly, from 2.1% to 0.8%. However, use of nicotine increased significantly from 0% to 1.3%, and misuse of prescription drugs increased significantly from 0% to 0.6%. “Changes in the rates of use of any substance, cannabis, or inhalants were not statistically significant,” the researchers wrote.

Sex and ethnicity were not associated with substance use during the pandemic, but rates of substance use were higher among youth whose parents were unmarried or had lower levels of education, and among those with preexisting externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Youth who reported higher levels of uncertainty related to COVID-19 were significantly more likely to report substance use; additionally, stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were positively association with any substance use during the pandemic survey periods. Youth whose parents experienced hardship or whose parents used alcohol or drugs also were more likely to report substance use.

“Stability in the overall rate of substance use in this cohort is reassuring given that the pandemic has brought increases in teens’ unoccupied time, stress, and loneliness, reduced access to support services, and disruptions to routines and family/parenting practices, all of which might be expected to have increased youth substance use,” the researchers noted. The findings do not explain the decreased alcohol use, but the researchers cited possible reasons for reduced alcohol use including lack of contact with friends and social activities, and greater supervision by parents.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the comparison of prepandemic and pandemic substance use in younger adolescents, which may not reflect changes in substance use in older adolescents. The study also could not establish causality, and did not account for the intensity of substance use, such as number of drinks, the researchers wrote. However, the results were strengthened by the longitudinal design and large, diverse study population, and the use of prepandemic assessments that allowed evaluation of changes over time.

Overall, the results highlight the importance of preexisting and acute risk protective factors in mitigating substance use in young adolescents, and suggest the potential of economic support for families and emotional support for youth as ways to reduce risk, the researchers concluded.

Predicting use and identifying risk factors

“It was important to conduct research at this time so we know how trends have changed during the pandemic,” Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said in an interview. The research helps clinicians “so we can better predict which substances our patients may be using, especially those with preexisting psychological conditions and those at socioeconomic disadvantage.

“I was surprised by the increased prescription drug use, but it make sense, as adolescents are at home more and may be illicitly using their parents medications,” Dr. Kinsella noted. “I think as they go back to school, trends will shift back to where they were as they will be spending more time with friends.” The take-home message to clinicians is the increased use of nicotine and prescription drugs during the pandemic, and future research should focus on substance use trends in 14- to 20-year-olds.

The ABCD study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the current study also received support from the National Science Foundation and Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kinsella had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Four police suicides in the aftermath of the Capitol siege: What can we learn?

Officer Scott Davis is a passionate man who thinks and talks quickly. As a member of the Special Events Team for Montgomery County, Maryland, he was already staging in Rockville, outside of Washington, D.C., when the call came in last Jan. 6 to move their unit to the U.S. Capitol.

“It was surreal,” said Mr. Davis. “There were people from all different groups at the Capitol that day. Many people were trying to get out, but others surrounded us. They called us ‘human race traitors.’ And then I heard someone say, ‘It’s good you brought your shields, we’ll carry your bodies out on them.’”

Mr. Davis described hours of mayhem during which he was hit with bear spray, a brick, a chair, and a metal rod. One of the members of Mr. Davis’ unit remains on leave with a head injury nearly 9 months after the siege.

“It went on for 3 hours, but it felt like 15 minutes. Then, all of a sudden, it was over.”

For the members of law enforcement at the Capitol that day, the repercussions are still being felt, perhaps most notably in the case of the four officers who subsequently died of suicide. Three of the officers were with the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia and one worked for the Capitol Police Department.

Police officers are subjected to traumas on a regular basis and often placed in circumstances where their lives are in danger. Yet four suicides within a short time – all connected to a single event – is particularly shocking and tragic, even more so for how little attention it has garnered to date.

What contributes to the high rate of suicide among officers?

Scott Silverii, PhD, a former police officer and author of Broken and Blue: A Policeman’s Guide to Health, Hope, and Healing, commented that he “wouldn’t be surprised if there are more suicides to come.” This stems not only from the experiences of that day but also the elevated risk for suicide that law enforcement officers already experienced prior to the Capitol riots. Suicide remains a rare event, with a national all-population average of 13.9 per 100,000 citizens. But as Dr. Silverii noted, more officers die by suicide each year than are killed in the line of duty.

“Suicide is a big part of police culture – officers are doers and fixers, and it is seen as being more honorable to take yourself out of the equation than it is to ask for help,” he said. “Most officers come in with past pain, and this is a situation where they are being overwhelmed and under-respected. At the same time, police culture is a closed culture, and it is not friendly to researchers.”

Another contributor is the frequency with which law enforcement officers are exposed to trauma, according to Vernon Herron, Director of Officer Safety and Wellness for the Baltimore City Police.

Mr. Herron said, citing the psychiatric and addiction issues that officers commonly experience.

Protecting the protectors

Mr. Herron and others are working to address these problems head-on.

“We are trying to identify employees exposed to trauma and to offer counseling and intervention,” he said, “Otherwise, everything else will fall short.”

Yet implementing such measures is no easy task, given the lack of a central oversight organization for law enforcement, said Sheldon Greenberg, PhD, a former police officer and professor of management in the School of Education at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“In the United States there is no such thing as ‘The Police.’ There is no one in a position to set policy, standards, or training mandates nationally,” he said. “There are approximately 18,000 police and sheriff departments in the country, and many of them are small. No one can compel law enforcement agencies to implement officer wellness and suicide prevention programs, make counseling available to officers, or train supervisors and peers to identify suicide ideation.”

Dr. Greenberg said a further barrier to helping police officers considering self-harm is posed by the fact that even if they do seek out counseling, there is no guarantee that it will remain confidential.

“Support personnel have an obligation to report an officer who is thinking about committing suicide,” he said. “Many officers are concerned about this lack of confidentiality and that they may be branded if they seek help.”

Although Dr. Greenberg said many police officers are self-professed “action junkies,” even their unusually high capacity for stress is often tested by the realities of the job.

“Increasing demands for service, shortages of personnel, misinformation about police, COVID-19, talk about restructuring policing with little concrete direction, increased exposure to violence, greater numbers of vulnerable people, and more take a toll over time,” he lamented. “In addition, we are in a recruiting crisis in law enforcement, and there are no standards to ensure the quality of psychological screening provided to applicants. Many officers will go through their entire career and never be screened again. We know little about the stresses and strains that officers bring to the job.”

After the siege

It is not clear how many police officers were present at the Capitol on Jan. 6. During the chaos of the day, reinforcements to the Capitol Police Department arrived from Washington D.C., Maryland, and Virginia, but no official numbers on responders were obtained; Mr. Davis thought it was likely that there were at least 1,000 law enforcement officers present. Those who did respond sustained an estimated 100 injuries, including an officer who died the next day. Of the officers who died by suicide, one died 3 days after, another died 9 days later, and two more died in July – numbers that contradict the notion that this is some coincidence. Officer Alexander Kettering, a colleague of Mr. Davis who has been with Montgomery County Police for 15 years, was among those tasked with protecting the Capitol on Jan. 6. The chaos, violence, and destruction of the day has stuck with him and continues to occupy his thoughts.

“I had a front-row seat to the whole thing. It was overwhelming, and I’ve never seen people this angry,” said Mr. Kettering. “There were people up on the veranda and on the scaffolding set up for the inauguration. They were smashing windows and throwing things into the crowd. It was insane. There were decent people coming up to us and saying they would pray for us, then others calling us traitors, telling us to stand down and join them.”

In the aftermath of the Capitol siege, Mr. Kettering watched in dismay as the narrative of the day’s events began to warp.

“At first there was a consensus that what happened was so wrong, and then the politics took over. People were saying it wasn’t as bad as the media said, that it really wasn’t that violent and those speaking out are traitors or political operatives. I relive it every day, and it’s hard to escape, even in casual conversation.”

He added that the days’ events were compounded by the already heightened tensions surrounding the national debate around policing.

“It’s been 18 months of stress, of anti-police movements, and there is a fine line between addressing police brutality and being anti-police,” Mr. Kettering said, noting that the aforementioned issues have all contributed to the ongoing struggles his fellow officers are experiencing.

“It’s not a thing for cops to talk about how an event affected them,” he said. “A lot of officers have just shut down. People have careers and pensions to protect, and every time we stop a motorist, something could go wrong, even if we do everything right. There are mixed signals: They tell us, ‘Defend but don’t defend.’”

His colleague, Mr. Davis, said that officers “need more support from politicians,” noting that he felt particularly insulted by a comment made by a Montgomery County public official who accused the officers present at the Capitol of racism. “And finally, we feel a little betrayed by the public.”

More questions than answers from the Capitol’s day of chaos

What about the events of Jan. 6 led to the suicides of four law enforcement officers and what can be done to prevent more deaths in the future? There are the individual factors of each man’s personal history, circumstances, and vulnerabilities, including the sense of being personally endangered, witnessing trauma, and direct injury – one officer who died of suicide had sustained a head injury that day.

We don’t know if the officers went into the event with preexisting mental illness or addiction or if the day’s events precipitated psychiatric episodes. And with all the partisan anger surrounding the presidential election, we don’t know if each officer’s political beliefs amplified his distress over what occurred in a social media climate where police are being faulted by all sides.

When multiple suicides occur in a community, there is always concern about a “copycat” phenomena. These concerns are made more difficult to address, however, given the police culture of taboo and stigma associated with getting professional help, difficulty accessing care, and career repercussions for speaking openly about suicidal thoughts and mental health issues.

Finally, there is the current political agenda that leaves officers feeling unsupported, fearful of negative outcomes, and unappreciated. The Capitol siege in particular embodied a great deal of national distress and confusion over basic issues of truth, justice, and perceptions of reality in our polarized society.

Can we move to a place where those who enforce laws have easy access to treatment, free from stigma? Can we encourage a culture that does not tolerate brutality or racism, while also refusing to label all police as bad and lending support to their mission? Can we be more attuned to the repercussions of circumstances where officers are witnesses to trauma, are endangered themselves, and would benefit from acknowledgment of their distress?

Time will tell if our anti-police pendulum swings back. In the meantime, these four suicides among people defending our country remain tragically overlooked.

Dinah Miller, MD, is coauthor of Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice in Baltimore and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Officer Scott Davis is a passionate man who thinks and talks quickly. As a member of the Special Events Team for Montgomery County, Maryland, he was already staging in Rockville, outside of Washington, D.C., when the call came in last Jan. 6 to move their unit to the U.S. Capitol.

“It was surreal,” said Mr. Davis. “There were people from all different groups at the Capitol that day. Many people were trying to get out, but others surrounded us. They called us ‘human race traitors.’ And then I heard someone say, ‘It’s good you brought your shields, we’ll carry your bodies out on them.’”

Mr. Davis described hours of mayhem during which he was hit with bear spray, a brick, a chair, and a metal rod. One of the members of Mr. Davis’ unit remains on leave with a head injury nearly 9 months after the siege.

“It went on for 3 hours, but it felt like 15 minutes. Then, all of a sudden, it was over.”

For the members of law enforcement at the Capitol that day, the repercussions are still being felt, perhaps most notably in the case of the four officers who subsequently died of suicide. Three of the officers were with the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia and one worked for the Capitol Police Department.

Police officers are subjected to traumas on a regular basis and often placed in circumstances where their lives are in danger. Yet four suicides within a short time – all connected to a single event – is particularly shocking and tragic, even more so for how little attention it has garnered to date.

What contributes to the high rate of suicide among officers?

Scott Silverii, PhD, a former police officer and author of Broken and Blue: A Policeman’s Guide to Health, Hope, and Healing, commented that he “wouldn’t be surprised if there are more suicides to come.” This stems not only from the experiences of that day but also the elevated risk for suicide that law enforcement officers already experienced prior to the Capitol riots. Suicide remains a rare event, with a national all-population average of 13.9 per 100,000 citizens. But as Dr. Silverii noted, more officers die by suicide each year than are killed in the line of duty.

“Suicide is a big part of police culture – officers are doers and fixers, and it is seen as being more honorable to take yourself out of the equation than it is to ask for help,” he said. “Most officers come in with past pain, and this is a situation where they are being overwhelmed and under-respected. At the same time, police culture is a closed culture, and it is not friendly to researchers.”

Another contributor is the frequency with which law enforcement officers are exposed to trauma, according to Vernon Herron, Director of Officer Safety and Wellness for the Baltimore City Police.

Mr. Herron said, citing the psychiatric and addiction issues that officers commonly experience.

Protecting the protectors

Mr. Herron and others are working to address these problems head-on.