User login

Heart rate variability: Are we ignoring a harbinger of health?

A very long time ago, when I ran clinical labs, one of the most ordered tests was the “sed rate” (aka ESR, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Easy, quick, and low cost, with high sensitivity but very low specificity. If the sed rate was normal, the patient probably did not have an infectious or inflammatory disease. If it was elevated, they probably did, but no telling what. Later, the C-reactive protein (CRP) test came into common use. Same general inferences: If the CRP was low, the patient was unlikely to have an inflammatory process; if high, they were sick, but we didn’t know what with.

Could the heart rate variability (HRV) score come to be thought of similarly? Much as the sed rate and CRP are sensitivity indicators of infectious or inflammatory diseases, might the HRV score be a sensitivity indicator for nervous system (central and autonomic) and cardiovascular (especially heart rhythm) malfunctions?

A substantial and relatively old body of heart rhythm literature ties HRV alterations to posttraumatic stress disorder, physician occupational stress, sleep disorders, depression, autonomic nervous system derangements, various cardiac arrhythmias, fatigue, overexertion, medications, and age itself.

More than 100 million Americans are now believed to use smartwatches or personal fitness monitors. Some 30%-40% of these devices measure HRV. So what? Credible research about this huge mass of accumulating data from “wearables” is lacking.

What is HRV?

HRV is the variation in time between each heartbeat, in milliseconds. HRV is influenced by the autonomic nervous system, perhaps reflecting sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. Some devices measure HRV 24/7. My Fitbit Inspire 2 reports only nighttime measures during 3 hours of sustained sleep. Most trackers report averages; some calculate the root mean squares; others calculate standard deviations. All fitness trackers warn not to use the data for medical purposes.

Normal values (reference ranges) for HRV begin at an average of 100 msec in the first decade of life and decline by approximately 10 msec per decade lived. At age 30-40, the average is 70 msec; age 60-70, it’s 40 msec; and at age 90-100, it’s 10 msec.

As a long-time lab guy, I used to teach proper use of lab tests. Fitness trackers are “lab tests” of a sort. We taught never to do a lab test unless you know what you are going to do with the result, no matter what it is. We also taught “never do anything just because you can.” Curiosity, we know, is a frequent driver of lab test ordering.

That underlying philosophy gives me a hard time when it comes to wearables. I have been enamored of watching my step count, active zone minutes, resting heart rate, active heart rate, various sleep scores, and breathing rate (and, of course, a manually entered early morning daily body weight) for several years. I even check my “readiness score” (a calculation using resting heart rate, recent sleep, recent active zone minutes, and perhaps HRV) each morning and adjust my behaviors accordingly.

Why monitor HRV?

But what should we do with HRV scores? Ignore them? Try to understand them, perhaps as a screening tool? Or monitor HRV for consistency or change? “Monitoring” is a proper and common use of lab tests.

Some say we should improve the HRV score by managing stress, getting regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, getting enough sleep, and not smoking or consuming excess alcohol. Duh! I do all of that anyway.

The claims that HRV is a “simple but powerful tool that can be used to track overall health and well-being” might turn out to be true. Proper study and sharing of data will enable that determination.

To advance understanding, I offer an n-of-1, a real-world personal anecdote about HRV.

I did not request the HRV function on my Fitbit Inspire 2. It simply appeared, and I ignored it for some time.

A year or two ago, I started noticing my HRV score every morning. Initially, I did not like to see my “low” score, until I learned that the reference range was dramatically affected by age and I was in my late 80s at the time. The vast majority of my HRV readings were in the range of 17 msec to 27 msec.

Last week, I was administered the new Moderna COVID-19 Spikevax vaccine and the old folks’ influenza vaccine simultaneously. In my case, side effects from each vaccine have been modest in the past, but I never previously had both administered at the same time. My immune response was, shall we say, robust. Chills, muscle aches, headache, fatigue, deltoid swelling, fitful sleep, and increased resting heart rate.

My nightly average HRV had been running between 17 msec and 35 msec for many months. WHOA! After the shots, my overnight HRV score plummeted from 24 msec to 10 msec, my lowest ever. Instant worry. The next day, it rebounded to 28 msec, and it has been in the high teens or low 20s since then.

Off to PubMed. A recent study of HRV on the second and 10th days after administering the Pfizer mRNA vaccine to 75 healthy volunteers found that the HRV on day 2 was dramatically lower than prevaccination levels and by day 10, it had returned to prevaccination levels. Some comfort there.

Another review article has reported a rapid fall and rapid rebound of HRV after COVID-19 vaccination. A 2010 report demonstrated a significant but not dramatic short-term lowering of HRV after influenza A vaccination and correlated it with CRP changes.

Some believe that the decline in HRV after vaccination reflects an increased immune response and sympathetic nervous activity.

I don’t plan to receive my flu and COVID vaccines on the same day again.

So, I went back to review what happened to my HRV when I had COVID in 2023. My HRV was 14 msec and 12 msec on the first 2 days of symptoms, and then returned to the 20 msec range.

I received the RSV vaccine this year without adverse effects, and my HRV scores were 29 msec, 33 msec, and 32 msec on the first 3 days after vaccination. Finally, after receiving a pneumococcal vaccine in 2023, I had no adverse effects, and my HRV scores on the 5 days after vaccination were indeterminate: 19 msec, 14 msec, 18 msec, 13 msec, and 17 msec.

Of course, correlation is not causation. Cause and effect remain undetermined. But I find these observations interesting for a potentially useful screening test.

George D. Lundberg, MD, is the Editor in Chief of Cancer Commons.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A very long time ago, when I ran clinical labs, one of the most ordered tests was the “sed rate” (aka ESR, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Easy, quick, and low cost, with high sensitivity but very low specificity. If the sed rate was normal, the patient probably did not have an infectious or inflammatory disease. If it was elevated, they probably did, but no telling what. Later, the C-reactive protein (CRP) test came into common use. Same general inferences: If the CRP was low, the patient was unlikely to have an inflammatory process; if high, they were sick, but we didn’t know what with.

Could the heart rate variability (HRV) score come to be thought of similarly? Much as the sed rate and CRP are sensitivity indicators of infectious or inflammatory diseases, might the HRV score be a sensitivity indicator for nervous system (central and autonomic) and cardiovascular (especially heart rhythm) malfunctions?

A substantial and relatively old body of heart rhythm literature ties HRV alterations to posttraumatic stress disorder, physician occupational stress, sleep disorders, depression, autonomic nervous system derangements, various cardiac arrhythmias, fatigue, overexertion, medications, and age itself.

More than 100 million Americans are now believed to use smartwatches or personal fitness monitors. Some 30%-40% of these devices measure HRV. So what? Credible research about this huge mass of accumulating data from “wearables” is lacking.

What is HRV?

HRV is the variation in time between each heartbeat, in milliseconds. HRV is influenced by the autonomic nervous system, perhaps reflecting sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. Some devices measure HRV 24/7. My Fitbit Inspire 2 reports only nighttime measures during 3 hours of sustained sleep. Most trackers report averages; some calculate the root mean squares; others calculate standard deviations. All fitness trackers warn not to use the data for medical purposes.

Normal values (reference ranges) for HRV begin at an average of 100 msec in the first decade of life and decline by approximately 10 msec per decade lived. At age 30-40, the average is 70 msec; age 60-70, it’s 40 msec; and at age 90-100, it’s 10 msec.

As a long-time lab guy, I used to teach proper use of lab tests. Fitness trackers are “lab tests” of a sort. We taught never to do a lab test unless you know what you are going to do with the result, no matter what it is. We also taught “never do anything just because you can.” Curiosity, we know, is a frequent driver of lab test ordering.

That underlying philosophy gives me a hard time when it comes to wearables. I have been enamored of watching my step count, active zone minutes, resting heart rate, active heart rate, various sleep scores, and breathing rate (and, of course, a manually entered early morning daily body weight) for several years. I even check my “readiness score” (a calculation using resting heart rate, recent sleep, recent active zone minutes, and perhaps HRV) each morning and adjust my behaviors accordingly.

Why monitor HRV?

But what should we do with HRV scores? Ignore them? Try to understand them, perhaps as a screening tool? Or monitor HRV for consistency or change? “Monitoring” is a proper and common use of lab tests.

Some say we should improve the HRV score by managing stress, getting regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, getting enough sleep, and not smoking or consuming excess alcohol. Duh! I do all of that anyway.

The claims that HRV is a “simple but powerful tool that can be used to track overall health and well-being” might turn out to be true. Proper study and sharing of data will enable that determination.

To advance understanding, I offer an n-of-1, a real-world personal anecdote about HRV.

I did not request the HRV function on my Fitbit Inspire 2. It simply appeared, and I ignored it for some time.

A year or two ago, I started noticing my HRV score every morning. Initially, I did not like to see my “low” score, until I learned that the reference range was dramatically affected by age and I was in my late 80s at the time. The vast majority of my HRV readings were in the range of 17 msec to 27 msec.

Last week, I was administered the new Moderna COVID-19 Spikevax vaccine and the old folks’ influenza vaccine simultaneously. In my case, side effects from each vaccine have been modest in the past, but I never previously had both administered at the same time. My immune response was, shall we say, robust. Chills, muscle aches, headache, fatigue, deltoid swelling, fitful sleep, and increased resting heart rate.

My nightly average HRV had been running between 17 msec and 35 msec for many months. WHOA! After the shots, my overnight HRV score plummeted from 24 msec to 10 msec, my lowest ever. Instant worry. The next day, it rebounded to 28 msec, and it has been in the high teens or low 20s since then.

Off to PubMed. A recent study of HRV on the second and 10th days after administering the Pfizer mRNA vaccine to 75 healthy volunteers found that the HRV on day 2 was dramatically lower than prevaccination levels and by day 10, it had returned to prevaccination levels. Some comfort there.

Another review article has reported a rapid fall and rapid rebound of HRV after COVID-19 vaccination. A 2010 report demonstrated a significant but not dramatic short-term lowering of HRV after influenza A vaccination and correlated it with CRP changes.

Some believe that the decline in HRV after vaccination reflects an increased immune response and sympathetic nervous activity.

I don’t plan to receive my flu and COVID vaccines on the same day again.

So, I went back to review what happened to my HRV when I had COVID in 2023. My HRV was 14 msec and 12 msec on the first 2 days of symptoms, and then returned to the 20 msec range.

I received the RSV vaccine this year without adverse effects, and my HRV scores were 29 msec, 33 msec, and 32 msec on the first 3 days after vaccination. Finally, after receiving a pneumococcal vaccine in 2023, I had no adverse effects, and my HRV scores on the 5 days after vaccination were indeterminate: 19 msec, 14 msec, 18 msec, 13 msec, and 17 msec.

Of course, correlation is not causation. Cause and effect remain undetermined. But I find these observations interesting for a potentially useful screening test.

George D. Lundberg, MD, is the Editor in Chief of Cancer Commons.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A very long time ago, when I ran clinical labs, one of the most ordered tests was the “sed rate” (aka ESR, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Easy, quick, and low cost, with high sensitivity but very low specificity. If the sed rate was normal, the patient probably did not have an infectious or inflammatory disease. If it was elevated, they probably did, but no telling what. Later, the C-reactive protein (CRP) test came into common use. Same general inferences: If the CRP was low, the patient was unlikely to have an inflammatory process; if high, they were sick, but we didn’t know what with.

Could the heart rate variability (HRV) score come to be thought of similarly? Much as the sed rate and CRP are sensitivity indicators of infectious or inflammatory diseases, might the HRV score be a sensitivity indicator for nervous system (central and autonomic) and cardiovascular (especially heart rhythm) malfunctions?

A substantial and relatively old body of heart rhythm literature ties HRV alterations to posttraumatic stress disorder, physician occupational stress, sleep disorders, depression, autonomic nervous system derangements, various cardiac arrhythmias, fatigue, overexertion, medications, and age itself.

More than 100 million Americans are now believed to use smartwatches or personal fitness monitors. Some 30%-40% of these devices measure HRV. So what? Credible research about this huge mass of accumulating data from “wearables” is lacking.

What is HRV?

HRV is the variation in time between each heartbeat, in milliseconds. HRV is influenced by the autonomic nervous system, perhaps reflecting sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. Some devices measure HRV 24/7. My Fitbit Inspire 2 reports only nighttime measures during 3 hours of sustained sleep. Most trackers report averages; some calculate the root mean squares; others calculate standard deviations. All fitness trackers warn not to use the data for medical purposes.

Normal values (reference ranges) for HRV begin at an average of 100 msec in the first decade of life and decline by approximately 10 msec per decade lived. At age 30-40, the average is 70 msec; age 60-70, it’s 40 msec; and at age 90-100, it’s 10 msec.

As a long-time lab guy, I used to teach proper use of lab tests. Fitness trackers are “lab tests” of a sort. We taught never to do a lab test unless you know what you are going to do with the result, no matter what it is. We also taught “never do anything just because you can.” Curiosity, we know, is a frequent driver of lab test ordering.

That underlying philosophy gives me a hard time when it comes to wearables. I have been enamored of watching my step count, active zone minutes, resting heart rate, active heart rate, various sleep scores, and breathing rate (and, of course, a manually entered early morning daily body weight) for several years. I even check my “readiness score” (a calculation using resting heart rate, recent sleep, recent active zone minutes, and perhaps HRV) each morning and adjust my behaviors accordingly.

Why monitor HRV?

But what should we do with HRV scores? Ignore them? Try to understand them, perhaps as a screening tool? Or monitor HRV for consistency or change? “Monitoring” is a proper and common use of lab tests.

Some say we should improve the HRV score by managing stress, getting regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, getting enough sleep, and not smoking or consuming excess alcohol. Duh! I do all of that anyway.

The claims that HRV is a “simple but powerful tool that can be used to track overall health and well-being” might turn out to be true. Proper study and sharing of data will enable that determination.

To advance understanding, I offer an n-of-1, a real-world personal anecdote about HRV.

I did not request the HRV function on my Fitbit Inspire 2. It simply appeared, and I ignored it for some time.

A year or two ago, I started noticing my HRV score every morning. Initially, I did not like to see my “low” score, until I learned that the reference range was dramatically affected by age and I was in my late 80s at the time. The vast majority of my HRV readings were in the range of 17 msec to 27 msec.

Last week, I was administered the new Moderna COVID-19 Spikevax vaccine and the old folks’ influenza vaccine simultaneously. In my case, side effects from each vaccine have been modest in the past, but I never previously had both administered at the same time. My immune response was, shall we say, robust. Chills, muscle aches, headache, fatigue, deltoid swelling, fitful sleep, and increased resting heart rate.

My nightly average HRV had been running between 17 msec and 35 msec for many months. WHOA! After the shots, my overnight HRV score plummeted from 24 msec to 10 msec, my lowest ever. Instant worry. The next day, it rebounded to 28 msec, and it has been in the high teens or low 20s since then.

Off to PubMed. A recent study of HRV on the second and 10th days after administering the Pfizer mRNA vaccine to 75 healthy volunteers found that the HRV on day 2 was dramatically lower than prevaccination levels and by day 10, it had returned to prevaccination levels. Some comfort there.

Another review article has reported a rapid fall and rapid rebound of HRV after COVID-19 vaccination. A 2010 report demonstrated a significant but not dramatic short-term lowering of HRV after influenza A vaccination and correlated it with CRP changes.

Some believe that the decline in HRV after vaccination reflects an increased immune response and sympathetic nervous activity.

I don’t plan to receive my flu and COVID vaccines on the same day again.

So, I went back to review what happened to my HRV when I had COVID in 2023. My HRV was 14 msec and 12 msec on the first 2 days of symptoms, and then returned to the 20 msec range.

I received the RSV vaccine this year without adverse effects, and my HRV scores were 29 msec, 33 msec, and 32 msec on the first 3 days after vaccination. Finally, after receiving a pneumococcal vaccine in 2023, I had no adverse effects, and my HRV scores on the 5 days after vaccination were indeterminate: 19 msec, 14 msec, 18 msec, 13 msec, and 17 msec.

Of course, correlation is not causation. Cause and effect remain undetermined. But I find these observations interesting for a potentially useful screening test.

George D. Lundberg, MD, is the Editor in Chief of Cancer Commons.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

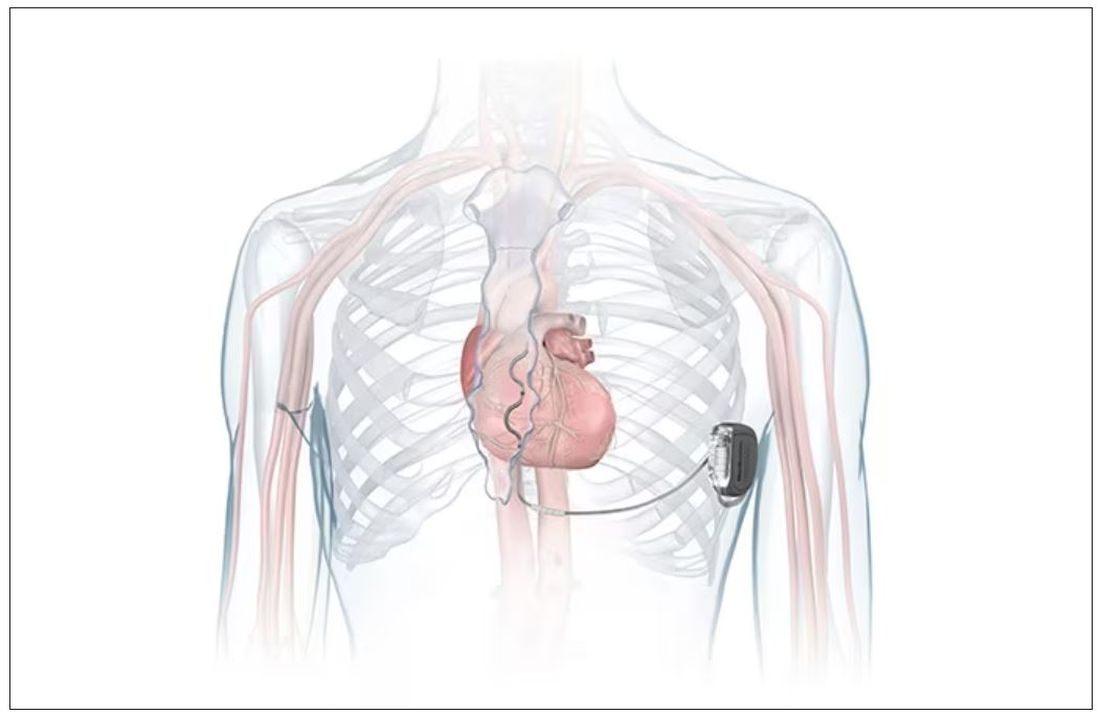

FDA okays first extravascular ICD system

which uses a single lead implanted substernally to allow antitachycardia pacing and low-energy defibrillation while avoiding the vascular space for lead placement.

“The Aurora EV-ICD system is a tremendous step forward in implantable defibrillator technology,” Bradley P. Knight, MD, medical director of electrophysiology at Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute, Chicago, said in a company news release.

“Placing the leads outside of the heart, rather than inside the heart and veins, reduces the risk of long-term complications, ultimately allowing us to further evolve safe and effective ICD technology,” said Dr. Knight, who was involved in the pivotal trial that led to U.S. approval.

The approval, which includes the system’s proprietary procedure implant tools, was supported by results from a global pivotal study that demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the system.

Results of the study were presented at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology in 2022.

The study enrolled 356 patients who were at risk of sudden cardiac death and who had a class I or IIa indication for ICD. Participants were enrolled at 46 sites in 17 countries.

The device’s effectiveness in delivering defibrillation therapy at implant (primary efficacy endpoint) was 98.7%, compared with a prespecified target of 88%.

There were no major intraprocedural complications, nor were any unique complications observed that were related to the EV ICD procedure or system, compared with transvenous and subcutaneous ICDs.

Additionally, 33 defibrillation shocks were avoided by having antitachycardia pacing programmed “on.”

At 6 months, 92.6% of patients (Kaplan-Meier estimate) were free from major system- and/or procedure-related major complications, such as hospitalization, system revision, or death.

The Aurora EV-ICD system is indicated for patients who are at risk of life-threatening arrhythmias, who have not previously undergone sternotomy, and who do not need long-term bradycardia pacing.

The Aurora EV-ICD system is similar in size, shape, and longevity to traditional transvenous ICDs.

Medtronic said the Aurora EV-ICD system will be commercially available on a limited basis in the United States in the coming weeks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

which uses a single lead implanted substernally to allow antitachycardia pacing and low-energy defibrillation while avoiding the vascular space for lead placement.

“The Aurora EV-ICD system is a tremendous step forward in implantable defibrillator technology,” Bradley P. Knight, MD, medical director of electrophysiology at Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute, Chicago, said in a company news release.

“Placing the leads outside of the heart, rather than inside the heart and veins, reduces the risk of long-term complications, ultimately allowing us to further evolve safe and effective ICD technology,” said Dr. Knight, who was involved in the pivotal trial that led to U.S. approval.

The approval, which includes the system’s proprietary procedure implant tools, was supported by results from a global pivotal study that demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the system.

Results of the study were presented at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology in 2022.

The study enrolled 356 patients who were at risk of sudden cardiac death and who had a class I or IIa indication for ICD. Participants were enrolled at 46 sites in 17 countries.

The device’s effectiveness in delivering defibrillation therapy at implant (primary efficacy endpoint) was 98.7%, compared with a prespecified target of 88%.

There were no major intraprocedural complications, nor were any unique complications observed that were related to the EV ICD procedure or system, compared with transvenous and subcutaneous ICDs.

Additionally, 33 defibrillation shocks were avoided by having antitachycardia pacing programmed “on.”

At 6 months, 92.6% of patients (Kaplan-Meier estimate) were free from major system- and/or procedure-related major complications, such as hospitalization, system revision, or death.

The Aurora EV-ICD system is indicated for patients who are at risk of life-threatening arrhythmias, who have not previously undergone sternotomy, and who do not need long-term bradycardia pacing.

The Aurora EV-ICD system is similar in size, shape, and longevity to traditional transvenous ICDs.

Medtronic said the Aurora EV-ICD system will be commercially available on a limited basis in the United States in the coming weeks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

which uses a single lead implanted substernally to allow antitachycardia pacing and low-energy defibrillation while avoiding the vascular space for lead placement.

“The Aurora EV-ICD system is a tremendous step forward in implantable defibrillator technology,” Bradley P. Knight, MD, medical director of electrophysiology at Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute, Chicago, said in a company news release.

“Placing the leads outside of the heart, rather than inside the heart and veins, reduces the risk of long-term complications, ultimately allowing us to further evolve safe and effective ICD technology,” said Dr. Knight, who was involved in the pivotal trial that led to U.S. approval.

The approval, which includes the system’s proprietary procedure implant tools, was supported by results from a global pivotal study that demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the system.

Results of the study were presented at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology in 2022.

The study enrolled 356 patients who were at risk of sudden cardiac death and who had a class I or IIa indication for ICD. Participants were enrolled at 46 sites in 17 countries.

The device’s effectiveness in delivering defibrillation therapy at implant (primary efficacy endpoint) was 98.7%, compared with a prespecified target of 88%.

There were no major intraprocedural complications, nor were any unique complications observed that were related to the EV ICD procedure or system, compared with transvenous and subcutaneous ICDs.

Additionally, 33 defibrillation shocks were avoided by having antitachycardia pacing programmed “on.”

At 6 months, 92.6% of patients (Kaplan-Meier estimate) were free from major system- and/or procedure-related major complications, such as hospitalization, system revision, or death.

The Aurora EV-ICD system is indicated for patients who are at risk of life-threatening arrhythmias, who have not previously undergone sternotomy, and who do not need long-term bradycardia pacing.

The Aurora EV-ICD system is similar in size, shape, and longevity to traditional transvenous ICDs.

Medtronic said the Aurora EV-ICD system will be commercially available on a limited basis in the United States in the coming weeks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Diagnosis creep’: Are some AFib patients overtreated?

without those treatments having been validated in those particular groups.

This concern has been highlighted recently in the atrial fibrillation (AF) field, with the recent change in the definition of hypertension in the United States at lower levels of blood pressure causing a lot more patients to become eligible for oral anticoagulation at an earlier stage in their AF course.

U.S. researchers analyzed data from 316,388 patients with AF from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence outpatient quality improvement registry, and found that at 36 months’ follow-up, 83.5% of patients met the new 130/80 mm Hg definition of hypertension, while only 53.3% met the previous 140/90 mm Hg definition.

The diagnosis of hypertension gives 1 point in the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which is used to determine risk in AF patients, those with scores of 2 or more being eligible for oral anticoagulation.

The researchers report that in patients with an index CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 (before the hypertension diagnosis), at 36 months, 83% fulfilled the 130/80 mm Hg definition of hypertension while the 140/90 mm Hg definition was met by only 50%, giving a large increase in the number of patients who could qualify for oral anticoagulation therapy.

“While the definition of hypertension has changed in response to landmark clinical trials, CHA2DS2-VASc was validated using an older hypertension definition, with limited ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and higher blood pressure goals for treatment,” the authors state.

“Now, patients with AF will meet the CHA2DS2-VASc threshold for oral anticoagulation earlier in their disease course. However, it is not known if patients with scores of 1 or 2 using the new hypertension definition have sufficient stroke risk to offset the bleeding risk of oral anticoagulation and will receive net clinical benefit,” they point out.

This study was published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

Senior author of the report, Mintu Turakhia, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University/iRhythm Technologies Inc., said AF is a good example of how “diagnosis creep” may lead to patients receiving inappropriate treatment.

“Risk scores derived when risk variables were described in one way are starting to be applied based on a diagnosis made in a totally different way,” he said in an interview. “Diagnosis creep is a problem everywhere in medicine. The goal of this study was to quantify what this means for the new definition of hypertension in the context of risk scoring AF patients for anticoagulation treatment. We are calling attention to this issue so clinicians are aware of possible implications.”

Dr. Turakhia explained that the CHA2DS2-VASc score was formulated based on claims data so there was a record of hypertension on the clinical encounter. That hypertension diagnosis would have been based on the old definition of 140/90 mm Hg.

“But now we apply a label of hypertension in the office every time someone has a measurement of elevated blood pressure – treated or untreated – and the blood pressure threshold for a hypertension diagnosis has changed to 130/80 mm Hg,” he said. “We are asking what this means for risk stratification scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc, and how do we quantify what that means for anticoagulation eligibility?”

He said that while identifying hypertension at lower blood pressures may be beneficial with regard to starting antihypertensive treatment earlier with a consequent reduction in cardiovascular outcomes, when this also affects risk scores that determine treatment for other conditions, as is the case for AF, the case is not so clear.

Dr. Turakhia pointed out that with AF, there are additional factors causing diagnosis creep, including earlier detection of AF and identification of shorter episodes due to the use of higher sensitivity tools to detect abnormal rhythms.

“What about the patient who has been identified as having AF based on just a few seconds found on monitoring and who is aged 65 (so just over the age threshold for 1 point on the CHA2DS2-VASc score)?” he asked. “Now we’re going to throw in hypertension with a blood pressure measurement just over 130/80 mm Hg, and they will be eligible for anticoagulation.”

Dr. Turakhia noted that in addition to earlier classification of hypertension, other conditions contributing to the CHA2DS2-VASc score are also being detected earlier, including diabetes and reduced ejection fractions that are considered heart failure.

“I worry about the sum of the parts. We don’t know if the risk score performs equally well when we’re using these different thresholds. We have to be careful that we are not exposing patients to the bleeding risks of anticoagulation unnecessarily. There is a clear issue here,” he said.

What should clinicians do?

In a comment, Gregory Lip, MD, chair of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Liverpool, England, who helped develop the CHA2DS2-VASc score, said clinicians needed to think more broadly when considering hypertension as a risk factor for the score.

He points out that if a patient had a history of hypertension but is now controlled to below 130/80 mm Hg, they would still be considered to be at risk per the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

And for patients without a history of hypertension, and who have a current blood pressure measurement of around 130/80 mm Hg, Dr. Lip advises that it would be premature to diagnose hypertension immediately.

“Hypertension is not a yes/no diagnosis. If you look at the relationship between blood pressure and risk of stroke, it is like a continual dose-response. It doesn’t mean that at 129/79 there is no stroke risk but that at 130/80 there is a stroke risk. It’s not like that,” he said.

“I wouldn’t make a diagnosis on a one-off blood pressure measurement. I would want to monitor that patient and get them to do home measurements,” he commented. “If someone constantly has levels around that 130/80 mm Hg, I don’t necessarily rush in with a definite diagnosis of hypertension and start drug treatment. I would look at lifestyle first. And in such patients, I wouldn’t give them the 1 point for hypertension on the CHA2DS2-VASc score.”

Dr. Lip points out that a hypertension diagnosis is not just about blood pressure numbers. “We have to assess the patients much more completely before giving them a diagnosis and consider factors such as whether there is evidence of hypertension-related end-organ damage, and if lifestyle issues have been addressed.”

Are new risk scores needed?

Dr. Turakhia agreed that clinicians need to look at the bigger picture, but he also suggested that new risk scores may need to be developed.

“All of us in the medical community need to think about whether we should be recalibrating risk prediction with more contemporary evidence – based on our ability to detect disease now,” he commented.

“This could even be a different risk score altogether, possibly incorporating a wider range of parameters or perhaps incorporating machine learning. That’s really the question we need to be asking ourselves,” Dr. Turakhia added.

Dr. Lip noted that there are many stroke risk factors and only those that are most common and have been well validated go into clinical risk scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc.

“These risks scores are by design simplifications, and only have modest predictive value for identifying patients at high risk of stroke. You can always improve on clinical risk scores by adding in other variables,” he said. “There are some risk scores in AF with 26 variables. But the practical application of these more complex scores can be difficult in clinical practice. These risks scores are meant to be simple so that they can be used by busy clinicians in the outpatient clinic or on a ward round. It is not easy to input 26 different variables.”

He also noted that many guidelines are now veering away from categorizing patients at high, medium, or low risk of stroke, which he refers to as “artificial” classifications. “There is now more of a default position that patients should receive stroke prevention normally with a DOAC [direct oral anticoagulant] unless they are low risk.”

Dr. Turakhia agreed that it is imperative to look at the bigger picture when identifying AF patients for anticoagulation. “We have to be careful not to take things at face value. It is more important than ever to use clinical judgment to avoid overtreatment in borderline situations,” he concluded.

This study was supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Dr. Turakhia reported employment from iRhythm Technologies; equity from AliveCor, Connect America, Evidently, and Forward; grants from U.S. Food and Drug Administration, American Heart Association, Bayer, Sanofi, Gilead, and Bristol Myers Squibb; and personal fees from Pfizer and JAMA Cardiology (prior associate editor) outside the submitted work. Dr. Lip has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

without those treatments having been validated in those particular groups.

This concern has been highlighted recently in the atrial fibrillation (AF) field, with the recent change in the definition of hypertension in the United States at lower levels of blood pressure causing a lot more patients to become eligible for oral anticoagulation at an earlier stage in their AF course.

U.S. researchers analyzed data from 316,388 patients with AF from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence outpatient quality improvement registry, and found that at 36 months’ follow-up, 83.5% of patients met the new 130/80 mm Hg definition of hypertension, while only 53.3% met the previous 140/90 mm Hg definition.

The diagnosis of hypertension gives 1 point in the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which is used to determine risk in AF patients, those with scores of 2 or more being eligible for oral anticoagulation.

The researchers report that in patients with an index CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 (before the hypertension diagnosis), at 36 months, 83% fulfilled the 130/80 mm Hg definition of hypertension while the 140/90 mm Hg definition was met by only 50%, giving a large increase in the number of patients who could qualify for oral anticoagulation therapy.

“While the definition of hypertension has changed in response to landmark clinical trials, CHA2DS2-VASc was validated using an older hypertension definition, with limited ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and higher blood pressure goals for treatment,” the authors state.

“Now, patients with AF will meet the CHA2DS2-VASc threshold for oral anticoagulation earlier in their disease course. However, it is not known if patients with scores of 1 or 2 using the new hypertension definition have sufficient stroke risk to offset the bleeding risk of oral anticoagulation and will receive net clinical benefit,” they point out.

This study was published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

Senior author of the report, Mintu Turakhia, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University/iRhythm Technologies Inc., said AF is a good example of how “diagnosis creep” may lead to patients receiving inappropriate treatment.

“Risk scores derived when risk variables were described in one way are starting to be applied based on a diagnosis made in a totally different way,” he said in an interview. “Diagnosis creep is a problem everywhere in medicine. The goal of this study was to quantify what this means for the new definition of hypertension in the context of risk scoring AF patients for anticoagulation treatment. We are calling attention to this issue so clinicians are aware of possible implications.”

Dr. Turakhia explained that the CHA2DS2-VASc score was formulated based on claims data so there was a record of hypertension on the clinical encounter. That hypertension diagnosis would have been based on the old definition of 140/90 mm Hg.

“But now we apply a label of hypertension in the office every time someone has a measurement of elevated blood pressure – treated or untreated – and the blood pressure threshold for a hypertension diagnosis has changed to 130/80 mm Hg,” he said. “We are asking what this means for risk stratification scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc, and how do we quantify what that means for anticoagulation eligibility?”

He said that while identifying hypertension at lower blood pressures may be beneficial with regard to starting antihypertensive treatment earlier with a consequent reduction in cardiovascular outcomes, when this also affects risk scores that determine treatment for other conditions, as is the case for AF, the case is not so clear.

Dr. Turakhia pointed out that with AF, there are additional factors causing diagnosis creep, including earlier detection of AF and identification of shorter episodes due to the use of higher sensitivity tools to detect abnormal rhythms.

“What about the patient who has been identified as having AF based on just a few seconds found on monitoring and who is aged 65 (so just over the age threshold for 1 point on the CHA2DS2-VASc score)?” he asked. “Now we’re going to throw in hypertension with a blood pressure measurement just over 130/80 mm Hg, and they will be eligible for anticoagulation.”

Dr. Turakhia noted that in addition to earlier classification of hypertension, other conditions contributing to the CHA2DS2-VASc score are also being detected earlier, including diabetes and reduced ejection fractions that are considered heart failure.

“I worry about the sum of the parts. We don’t know if the risk score performs equally well when we’re using these different thresholds. We have to be careful that we are not exposing patients to the bleeding risks of anticoagulation unnecessarily. There is a clear issue here,” he said.

What should clinicians do?

In a comment, Gregory Lip, MD, chair of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Liverpool, England, who helped develop the CHA2DS2-VASc score, said clinicians needed to think more broadly when considering hypertension as a risk factor for the score.

He points out that if a patient had a history of hypertension but is now controlled to below 130/80 mm Hg, they would still be considered to be at risk per the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

And for patients without a history of hypertension, and who have a current blood pressure measurement of around 130/80 mm Hg, Dr. Lip advises that it would be premature to diagnose hypertension immediately.

“Hypertension is not a yes/no diagnosis. If you look at the relationship between blood pressure and risk of stroke, it is like a continual dose-response. It doesn’t mean that at 129/79 there is no stroke risk but that at 130/80 there is a stroke risk. It’s not like that,” he said.

“I wouldn’t make a diagnosis on a one-off blood pressure measurement. I would want to monitor that patient and get them to do home measurements,” he commented. “If someone constantly has levels around that 130/80 mm Hg, I don’t necessarily rush in with a definite diagnosis of hypertension and start drug treatment. I would look at lifestyle first. And in such patients, I wouldn’t give them the 1 point for hypertension on the CHA2DS2-VASc score.”

Dr. Lip points out that a hypertension diagnosis is not just about blood pressure numbers. “We have to assess the patients much more completely before giving them a diagnosis and consider factors such as whether there is evidence of hypertension-related end-organ damage, and if lifestyle issues have been addressed.”

Are new risk scores needed?

Dr. Turakhia agreed that clinicians need to look at the bigger picture, but he also suggested that new risk scores may need to be developed.

“All of us in the medical community need to think about whether we should be recalibrating risk prediction with more contemporary evidence – based on our ability to detect disease now,” he commented.

“This could even be a different risk score altogether, possibly incorporating a wider range of parameters or perhaps incorporating machine learning. That’s really the question we need to be asking ourselves,” Dr. Turakhia added.

Dr. Lip noted that there are many stroke risk factors and only those that are most common and have been well validated go into clinical risk scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc.

“These risks scores are by design simplifications, and only have modest predictive value for identifying patients at high risk of stroke. You can always improve on clinical risk scores by adding in other variables,” he said. “There are some risk scores in AF with 26 variables. But the practical application of these more complex scores can be difficult in clinical practice. These risks scores are meant to be simple so that they can be used by busy clinicians in the outpatient clinic or on a ward round. It is not easy to input 26 different variables.”

He also noted that many guidelines are now veering away from categorizing patients at high, medium, or low risk of stroke, which he refers to as “artificial” classifications. “There is now more of a default position that patients should receive stroke prevention normally with a DOAC [direct oral anticoagulant] unless they are low risk.”

Dr. Turakhia agreed that it is imperative to look at the bigger picture when identifying AF patients for anticoagulation. “We have to be careful not to take things at face value. It is more important than ever to use clinical judgment to avoid overtreatment in borderline situations,” he concluded.

This study was supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Dr. Turakhia reported employment from iRhythm Technologies; equity from AliveCor, Connect America, Evidently, and Forward; grants from U.S. Food and Drug Administration, American Heart Association, Bayer, Sanofi, Gilead, and Bristol Myers Squibb; and personal fees from Pfizer and JAMA Cardiology (prior associate editor) outside the submitted work. Dr. Lip has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

without those treatments having been validated in those particular groups.

This concern has been highlighted recently in the atrial fibrillation (AF) field, with the recent change in the definition of hypertension in the United States at lower levels of blood pressure causing a lot more patients to become eligible for oral anticoagulation at an earlier stage in their AF course.

U.S. researchers analyzed data from 316,388 patients with AF from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence outpatient quality improvement registry, and found that at 36 months’ follow-up, 83.5% of patients met the new 130/80 mm Hg definition of hypertension, while only 53.3% met the previous 140/90 mm Hg definition.

The diagnosis of hypertension gives 1 point in the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which is used to determine risk in AF patients, those with scores of 2 or more being eligible for oral anticoagulation.

The researchers report that in patients with an index CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 (before the hypertension diagnosis), at 36 months, 83% fulfilled the 130/80 mm Hg definition of hypertension while the 140/90 mm Hg definition was met by only 50%, giving a large increase in the number of patients who could qualify for oral anticoagulation therapy.

“While the definition of hypertension has changed in response to landmark clinical trials, CHA2DS2-VASc was validated using an older hypertension definition, with limited ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and higher blood pressure goals for treatment,” the authors state.

“Now, patients with AF will meet the CHA2DS2-VASc threshold for oral anticoagulation earlier in their disease course. However, it is not known if patients with scores of 1 or 2 using the new hypertension definition have sufficient stroke risk to offset the bleeding risk of oral anticoagulation and will receive net clinical benefit,” they point out.

This study was published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

Senior author of the report, Mintu Turakhia, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University/iRhythm Technologies Inc., said AF is a good example of how “diagnosis creep” may lead to patients receiving inappropriate treatment.

“Risk scores derived when risk variables were described in one way are starting to be applied based on a diagnosis made in a totally different way,” he said in an interview. “Diagnosis creep is a problem everywhere in medicine. The goal of this study was to quantify what this means for the new definition of hypertension in the context of risk scoring AF patients for anticoagulation treatment. We are calling attention to this issue so clinicians are aware of possible implications.”

Dr. Turakhia explained that the CHA2DS2-VASc score was formulated based on claims data so there was a record of hypertension on the clinical encounter. That hypertension diagnosis would have been based on the old definition of 140/90 mm Hg.

“But now we apply a label of hypertension in the office every time someone has a measurement of elevated blood pressure – treated or untreated – and the blood pressure threshold for a hypertension diagnosis has changed to 130/80 mm Hg,” he said. “We are asking what this means for risk stratification scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc, and how do we quantify what that means for anticoagulation eligibility?”

He said that while identifying hypertension at lower blood pressures may be beneficial with regard to starting antihypertensive treatment earlier with a consequent reduction in cardiovascular outcomes, when this also affects risk scores that determine treatment for other conditions, as is the case for AF, the case is not so clear.

Dr. Turakhia pointed out that with AF, there are additional factors causing diagnosis creep, including earlier detection of AF and identification of shorter episodes due to the use of higher sensitivity tools to detect abnormal rhythms.

“What about the patient who has been identified as having AF based on just a few seconds found on monitoring and who is aged 65 (so just over the age threshold for 1 point on the CHA2DS2-VASc score)?” he asked. “Now we’re going to throw in hypertension with a blood pressure measurement just over 130/80 mm Hg, and they will be eligible for anticoagulation.”

Dr. Turakhia noted that in addition to earlier classification of hypertension, other conditions contributing to the CHA2DS2-VASc score are also being detected earlier, including diabetes and reduced ejection fractions that are considered heart failure.

“I worry about the sum of the parts. We don’t know if the risk score performs equally well when we’re using these different thresholds. We have to be careful that we are not exposing patients to the bleeding risks of anticoagulation unnecessarily. There is a clear issue here,” he said.

What should clinicians do?

In a comment, Gregory Lip, MD, chair of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Liverpool, England, who helped develop the CHA2DS2-VASc score, said clinicians needed to think more broadly when considering hypertension as a risk factor for the score.

He points out that if a patient had a history of hypertension but is now controlled to below 130/80 mm Hg, they would still be considered to be at risk per the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

And for patients without a history of hypertension, and who have a current blood pressure measurement of around 130/80 mm Hg, Dr. Lip advises that it would be premature to diagnose hypertension immediately.

“Hypertension is not a yes/no diagnosis. If you look at the relationship between blood pressure and risk of stroke, it is like a continual dose-response. It doesn’t mean that at 129/79 there is no stroke risk but that at 130/80 there is a stroke risk. It’s not like that,” he said.

“I wouldn’t make a diagnosis on a one-off blood pressure measurement. I would want to monitor that patient and get them to do home measurements,” he commented. “If someone constantly has levels around that 130/80 mm Hg, I don’t necessarily rush in with a definite diagnosis of hypertension and start drug treatment. I would look at lifestyle first. And in such patients, I wouldn’t give them the 1 point for hypertension on the CHA2DS2-VASc score.”

Dr. Lip points out that a hypertension diagnosis is not just about blood pressure numbers. “We have to assess the patients much more completely before giving them a diagnosis and consider factors such as whether there is evidence of hypertension-related end-organ damage, and if lifestyle issues have been addressed.”

Are new risk scores needed?

Dr. Turakhia agreed that clinicians need to look at the bigger picture, but he also suggested that new risk scores may need to be developed.

“All of us in the medical community need to think about whether we should be recalibrating risk prediction with more contemporary evidence – based on our ability to detect disease now,” he commented.

“This could even be a different risk score altogether, possibly incorporating a wider range of parameters or perhaps incorporating machine learning. That’s really the question we need to be asking ourselves,” Dr. Turakhia added.

Dr. Lip noted that there are many stroke risk factors and only those that are most common and have been well validated go into clinical risk scores such as CHA2DS2-VASc.

“These risks scores are by design simplifications, and only have modest predictive value for identifying patients at high risk of stroke. You can always improve on clinical risk scores by adding in other variables,” he said. “There are some risk scores in AF with 26 variables. But the practical application of these more complex scores can be difficult in clinical practice. These risks scores are meant to be simple so that they can be used by busy clinicians in the outpatient clinic or on a ward round. It is not easy to input 26 different variables.”

He also noted that many guidelines are now veering away from categorizing patients at high, medium, or low risk of stroke, which he refers to as “artificial” classifications. “There is now more of a default position that patients should receive stroke prevention normally with a DOAC [direct oral anticoagulant] unless they are low risk.”

Dr. Turakhia agreed that it is imperative to look at the bigger picture when identifying AF patients for anticoagulation. “We have to be careful not to take things at face value. It is more important than ever to use clinical judgment to avoid overtreatment in borderline situations,” he concluded.

This study was supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Dr. Turakhia reported employment from iRhythm Technologies; equity from AliveCor, Connect America, Evidently, and Forward; grants from U.S. Food and Drug Administration, American Heart Association, Bayer, Sanofi, Gilead, and Bristol Myers Squibb; and personal fees from Pfizer and JAMA Cardiology (prior associate editor) outside the submitted work. Dr. Lip has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

EMA warns that omega-3-acid ethyl esters may cause AFib

In its September meeting, the Should atrial fibrillation develop, intake of the medication must be stopped permanently.

Omega-3-acid ethyl esters are used to treat hypertriglyceridemia if lifestyle changes, particularly those related to nutrition, have not been sufficient to lower the blood triglyceride level. Hypertriglyceridemia is a risk factor for coronary heart disease.

During a Periodic Safety Update Single Assessment Procedure, the EMA safety committee analyzed systematic overviews and meta-analyses of randomized, controlled clinical studies. Experts found a dose-dependent increase in the risk for atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiovascular diseases or cardiovascular risk factors who were being treated with omega-3-acid ethyl esters, compared with those treated with placebo. The observed risk was at its highest at a dose of 4 g/d.

The PRAC will recommend an update to the Summary of Product Characteristics for preparations that contain omega-3-acid ethyl esters. The aim is to inform physicians, pharmacists, and patients of the risk for atrial fibrillation. A notification will be sent to health care professionals soon to inform them of further details.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

In its September meeting, the Should atrial fibrillation develop, intake of the medication must be stopped permanently.

Omega-3-acid ethyl esters are used to treat hypertriglyceridemia if lifestyle changes, particularly those related to nutrition, have not been sufficient to lower the blood triglyceride level. Hypertriglyceridemia is a risk factor for coronary heart disease.

During a Periodic Safety Update Single Assessment Procedure, the EMA safety committee analyzed systematic overviews and meta-analyses of randomized, controlled clinical studies. Experts found a dose-dependent increase in the risk for atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiovascular diseases or cardiovascular risk factors who were being treated with omega-3-acid ethyl esters, compared with those treated with placebo. The observed risk was at its highest at a dose of 4 g/d.

The PRAC will recommend an update to the Summary of Product Characteristics for preparations that contain omega-3-acid ethyl esters. The aim is to inform physicians, pharmacists, and patients of the risk for atrial fibrillation. A notification will be sent to health care professionals soon to inform them of further details.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

In its September meeting, the Should atrial fibrillation develop, intake of the medication must be stopped permanently.

Omega-3-acid ethyl esters are used to treat hypertriglyceridemia if lifestyle changes, particularly those related to nutrition, have not been sufficient to lower the blood triglyceride level. Hypertriglyceridemia is a risk factor for coronary heart disease.

During a Periodic Safety Update Single Assessment Procedure, the EMA safety committee analyzed systematic overviews and meta-analyses of randomized, controlled clinical studies. Experts found a dose-dependent increase in the risk for atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiovascular diseases or cardiovascular risk factors who were being treated with omega-3-acid ethyl esters, compared with those treated with placebo. The observed risk was at its highest at a dose of 4 g/d.

The PRAC will recommend an update to the Summary of Product Characteristics for preparations that contain omega-3-acid ethyl esters. The aim is to inform physicians, pharmacists, and patients of the risk for atrial fibrillation. A notification will be sent to health care professionals soon to inform them of further details.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Decoding AFib recurrence: PCPs’ role in personalized care

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Anxiety, depression ease after AFib ablation: Clinical or placebo effect?

who had initially tested high for such psychological distress.

The finding, said the researchers, may point to an overlooked potential benefit of ablation that can be discussed with patients considering whether to have the procedure.

Importantly, the 100 adults with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AFib in the randomized trial weren’t blinded to treatment assignment, which was either ablation or continued medical therapy.

That leaves open the possibility that psychological distress improved in the ablation group not from any unique effect of ablation itself but because patients expected to benefit from the procedure.

The investigators acknowledged that their trial, called REMEDIAL, can’t rule out a placebo effect as part of the observed benefit. Indeed, studies suggest that there is a substantial placebo component of AFib ablation – which, notably, is usually done to make patients feel better.

But the current findings are more consistent with the conventional view that patients feel better primarily because ablation reduces the AFib causing their symptoms, the group said.

Psychological stress in the study started to fall early after the procedure and continued to decline consistently over the next 6 months (P = .006) and 12 months (P = .005), not a typical pattern for placebo, they wrote.

Moreover, the mental health benefits “correlated very strongly” with less recurrent AFib, reduced AFib burden, and withdrawal of beta-blockers and antiarrhythmic agents, outcomes that might be expected from ablation, said Jonathan M. Kalman, MBBS, PhD.

“Of course, I cannot say there is no placebo effect from having had the procedure, and maybe that something to consider,” but it’s probably not the main driver of benefit, he said in an interview. The relationship between successful AFib ablation “and improvements in physical and now mental health is overwhelming.”

Dr. Kalman, who is affiliated with Royal Melbourne Hospital, is senior author on the study, published in JAMA.

The findings add to “strong, reproducible evidence that ablation is the best way to tackle rhythm control in [AFib] populations” regardless of age, mental health status, or AFib burden, said Auroa Badin, MD, who wasn’t involved in REMEDIAL but has studied the psychological effects of arrhythmia ablation.

For example, there is “very good evidence” from CABANA and other trials that AFib ablation “considerably improves quality of life,” Dr. Badin, of OhioHealth Heart & Vascular Physicians, Columbus, said in an interview. The current study “just emphasizes that there’s also a psychological effect.”