User login

Pediatric emergencies associated with unnecessary testing: AAP

Children seen for these conditions in emergency settings and even in primary care offices could experience avoidable pain, exposure to harmful radiation, and other harms, according to the group.

“The emergency department has the ability to rapidly perform myriad diagnostic tests and receive results quickly,” said Paul Mullan, MD, MPH, chair of the AAP’s Section of Emergency Medicine’s Choosing Wisely task force. “However, this comes with the danger of diagnostic overtesting.”

The five recommendations are as follows:

- Radiographs should not be obtained for children with bronchiolitis, croup, asthma, or first-time wheezing.

- Laboratory tests for screening should not be undertaken in the medical clearance process of children who require inpatient psychiatric admission unless clinically indicated.

- Laboratory testing or a CT scan of the head should not be ordered for a child with an unprovoked, generalized seizure or a simple febrile seizure whose mental status has returned to baseline.

- Abdominal radiographs should not be obtained for suspected constipation.

- Comprehensive viral panel testing should not be undertaken for children who are suspected of having respiratory viral illnesses.

The AAP task force partnered with Choosing Wisely Canada to create the recommendations. The list is the first of its kind to be published jointly by two countries, according to the release.

“We hope this Choosing Wisely list will encourage clinicians to rely on their clinical skills and avoid unnecessary tests,” said Dr. Mullan, who is also a physician at Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters and professor of pediatrics at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children seen for these conditions in emergency settings and even in primary care offices could experience avoidable pain, exposure to harmful radiation, and other harms, according to the group.

“The emergency department has the ability to rapidly perform myriad diagnostic tests and receive results quickly,” said Paul Mullan, MD, MPH, chair of the AAP’s Section of Emergency Medicine’s Choosing Wisely task force. “However, this comes with the danger of diagnostic overtesting.”

The five recommendations are as follows:

- Radiographs should not be obtained for children with bronchiolitis, croup, asthma, or first-time wheezing.

- Laboratory tests for screening should not be undertaken in the medical clearance process of children who require inpatient psychiatric admission unless clinically indicated.

- Laboratory testing or a CT scan of the head should not be ordered for a child with an unprovoked, generalized seizure or a simple febrile seizure whose mental status has returned to baseline.

- Abdominal radiographs should not be obtained for suspected constipation.

- Comprehensive viral panel testing should not be undertaken for children who are suspected of having respiratory viral illnesses.

The AAP task force partnered with Choosing Wisely Canada to create the recommendations. The list is the first of its kind to be published jointly by two countries, according to the release.

“We hope this Choosing Wisely list will encourage clinicians to rely on their clinical skills and avoid unnecessary tests,” said Dr. Mullan, who is also a physician at Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters and professor of pediatrics at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children seen for these conditions in emergency settings and even in primary care offices could experience avoidable pain, exposure to harmful radiation, and other harms, according to the group.

“The emergency department has the ability to rapidly perform myriad diagnostic tests and receive results quickly,” said Paul Mullan, MD, MPH, chair of the AAP’s Section of Emergency Medicine’s Choosing Wisely task force. “However, this comes with the danger of diagnostic overtesting.”

The five recommendations are as follows:

- Radiographs should not be obtained for children with bronchiolitis, croup, asthma, or first-time wheezing.

- Laboratory tests for screening should not be undertaken in the medical clearance process of children who require inpatient psychiatric admission unless clinically indicated.

- Laboratory testing or a CT scan of the head should not be ordered for a child with an unprovoked, generalized seizure or a simple febrile seizure whose mental status has returned to baseline.

- Abdominal radiographs should not be obtained for suspected constipation.

- Comprehensive viral panel testing should not be undertaken for children who are suspected of having respiratory viral illnesses.

The AAP task force partnered with Choosing Wisely Canada to create the recommendations. The list is the first of its kind to be published jointly by two countries, according to the release.

“We hope this Choosing Wisely list will encourage clinicians to rely on their clinical skills and avoid unnecessary tests,” said Dr. Mullan, who is also a physician at Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters and professor of pediatrics at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma linked to higher carotid plaque burden

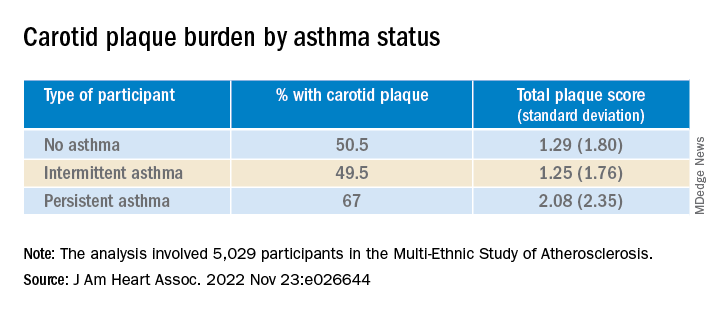

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

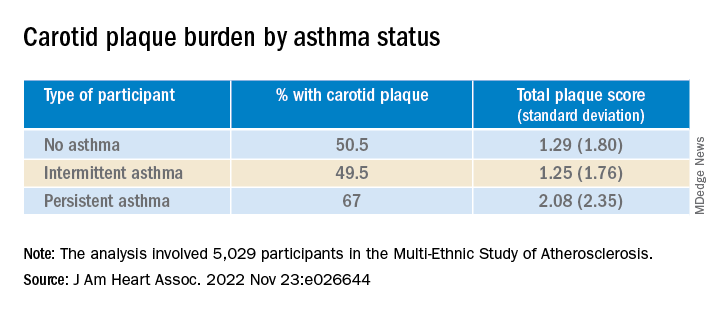

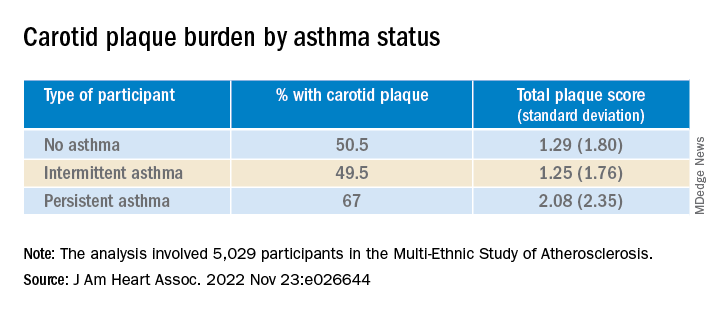

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

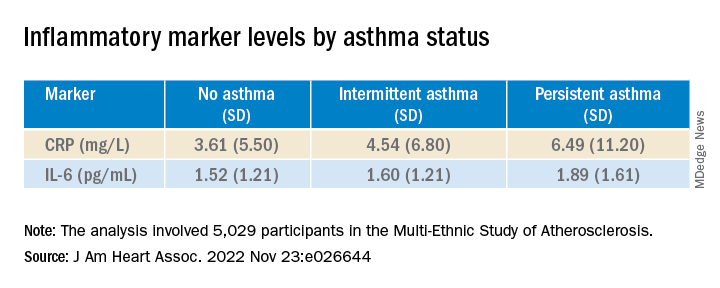

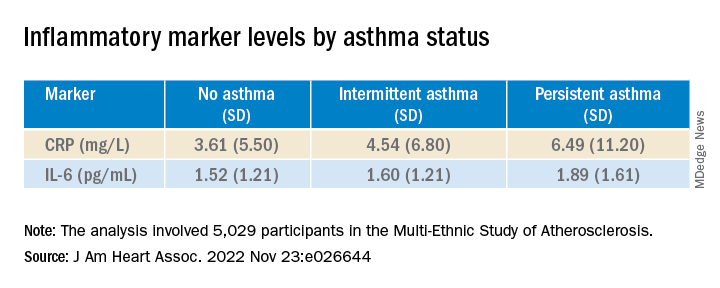

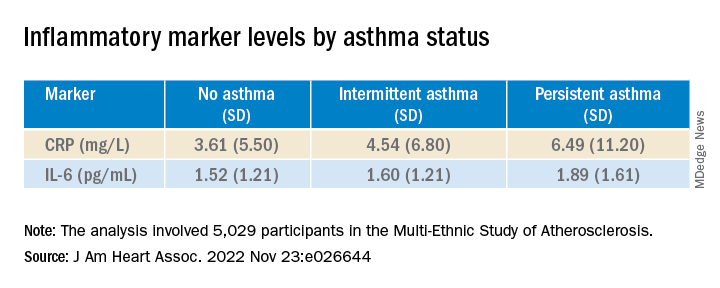

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Asthma management: How the guidelines compare

CASE

Erica S*, age 22, has intermittent asthma and presents to your clinic to discuss refills of her albuterol inhaler. Two years ago, she was hospitalized for a severe asthma exacerbation because she was unable to afford medications. Since then, her asthma has generally been well controlled, and she needs to use albuterol only 1 or 2 times per month. Ms. S says she has no morning chest tightness or nocturnal coughing, but she does experience increased wheezing and shortness of breath with activity.

What would you recommend? Would your recommendation differ if she had persistent asthma?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity .

As of 2020, more than 20 million adults and 4 million children younger than 18 years of age in the United States were living with asthma.1 In 2019 alone, there were more than 1.8 million asthma-related emergency department visits for adults, and more than 790,000 asthma-related emergency department visits for children. Asthma caused more than 4000 deaths in the United States in 2020.1 Given the scale of the burden of asthma, it is not surprising that approximately 60% of all asthma visits occur in primary care settings,2 making it essential that primary care physicians stay abreast of recent developments in asthma diagnosis and management.

Since 1991, the major guidance on best practices for asthma management in the United States has been provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)’s National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP). Its last major update on asthma was released in 2007 as the Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3).3 Since that time, there has been significant progress in our understanding of asthma as a complex spectrum of phenotypes, which has advanced our knowledge of pathophysiology and helped refine treatment. In contrast to the NAEPP, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has published annual updates on asthma management incorporating up-to-date information.4 In response to the continuously evolving body of knowledge on asthma, the NAEPP Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group published the 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines.5

Given the vast resources available on asthma, our purpose in this article is not to provide a comprehensive review of the stepwise approach to asthma management, but instead to summarize the major points presented in the 2020 Focused Updates and how these compare and contrast with the latest guidance from GINA.

A heterogeneous disease

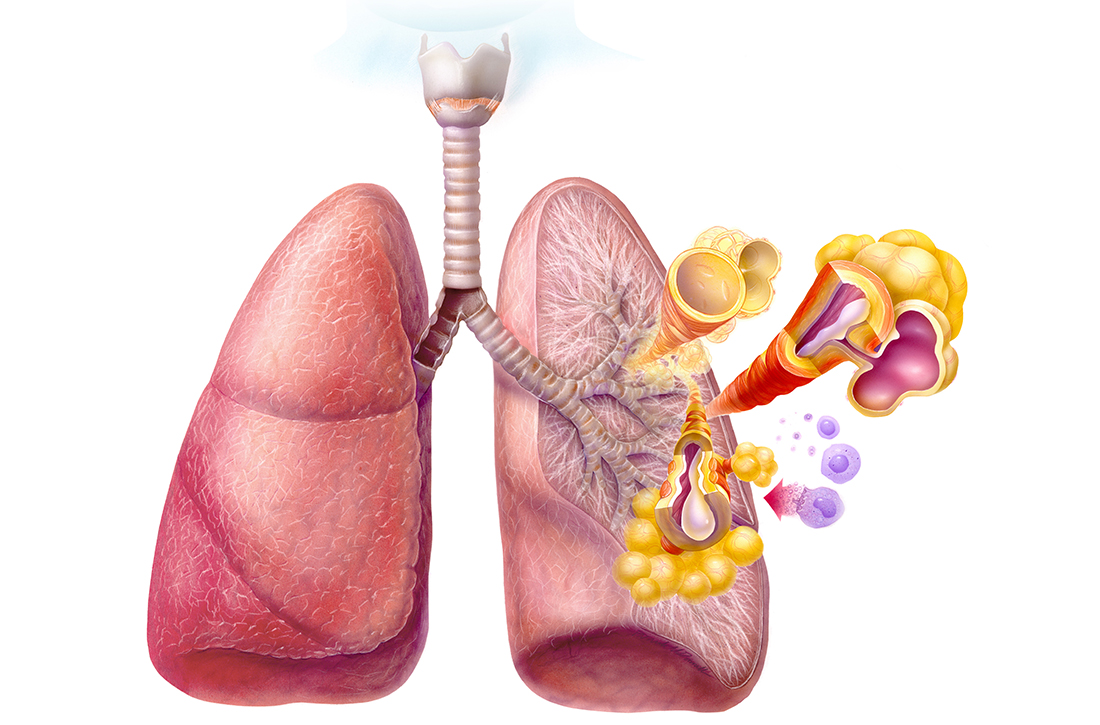

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by both variable symptoms and airflow limitation that change over time, often in response to external triggers such as exercise, allergens, and viral respiratory infections. Common symptoms include wheezing, cough, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. Despite the common symptomatology, asthma is a heterogeneous disease with several recognizable phenotypes including allergic, nonallergic, and asthma with persistent airflow limitation.

Continue to: The airflow limitation...

The airflow limitation in asthma occurs through both airway hyperresponsiveness to external stimuli and chronic airway inflammation. Airway constriction is regulated by nerves to the smooth muscles of the airway. Beta-2 nerve receptors have long been the target of asthma therapy with both short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABAs) as rescue treatment and long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABAs) as maintenance therapy.3,4 However, there is increasing evidence that cholinergic nerves also have a role in airway regulation in asthma, and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) have recently shown benefit as add-on therapy in some types of asthma.4-6 Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) have long held an important role in reducing airway inflammation, especially in the setting of allergic or eosinophilic inflammation.3-5

Spirometry is essential to asthma Dx—but what about FeNO?

The mainstay of asthma diagnosis is confirming both a history of variable respiratory symptoms and variable expiratory airflow limitation exhibited by spirometry. Obstruction is defined as a reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and as a decreased ratio of FEV1 over forced vital capacity (FVC) based on predicted values. An increase of at least 12% in FEV1 post bronchodilator use indicates asthma for adolescents and adults.

More recently, studies have examined the role of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in the diagnosis of asthma. The 2020 Focused Updates report states that FeNO may be useful when the diagnosis of asthma is uncertain using initial history, physical exam, and spirometry findings, or when spirometry cannot be performed reliably.5 Levels of FeNO > 50 ppb make eosinophilic inflammation and treatment response to an ICS more likely. FeNO levels < 25 ppb make inflammatory asthma less likely and should prompt a search for an alternate diagnosis.5 For patients with FeNO of 25 to 50 ppb, more detailed clinical context is needed. In contrast, the 2022 GINA updates conclude that FeNO is not yet an established diagnostic tool for asthma.4

Management

When to start and adjust an ICS

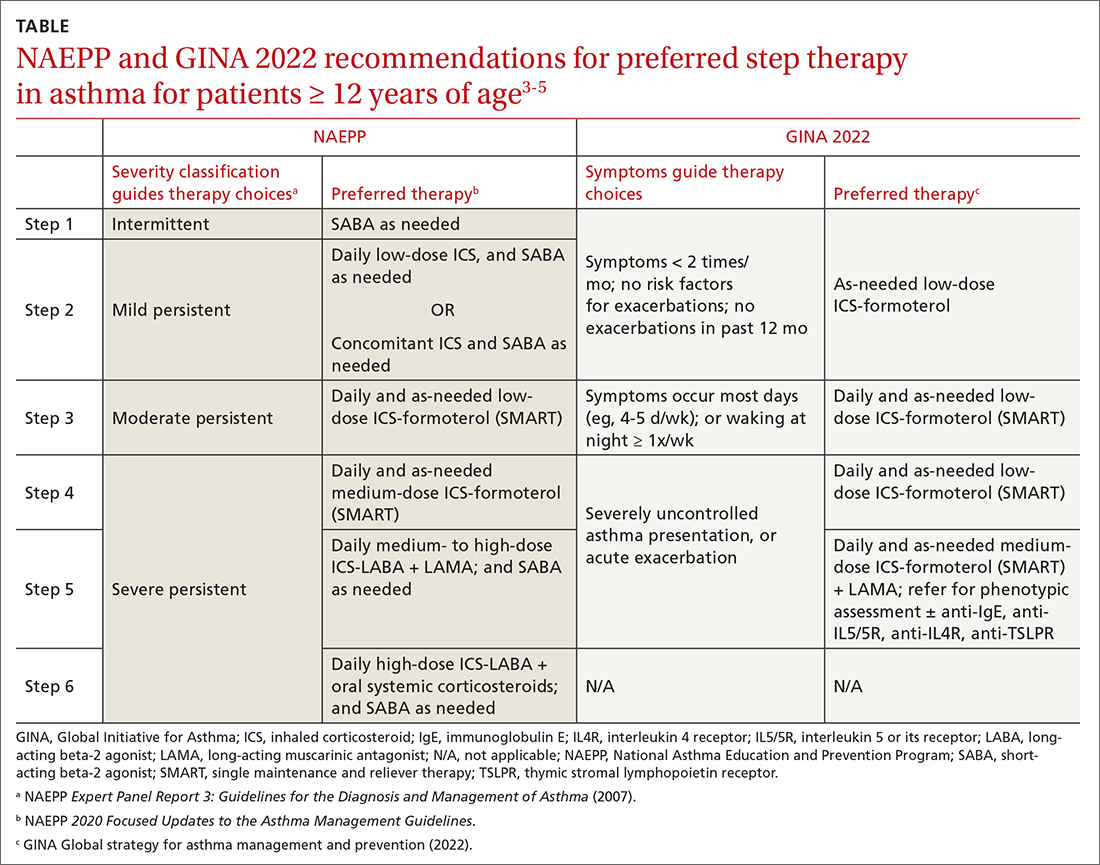

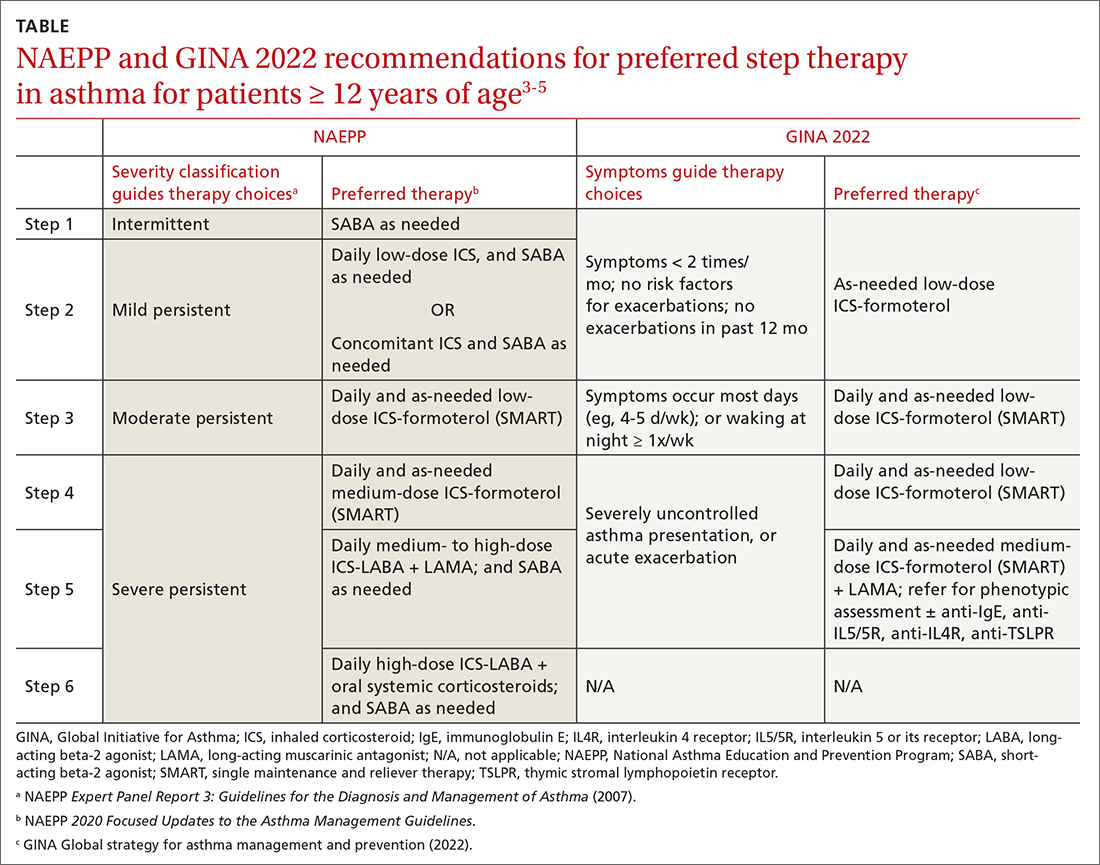

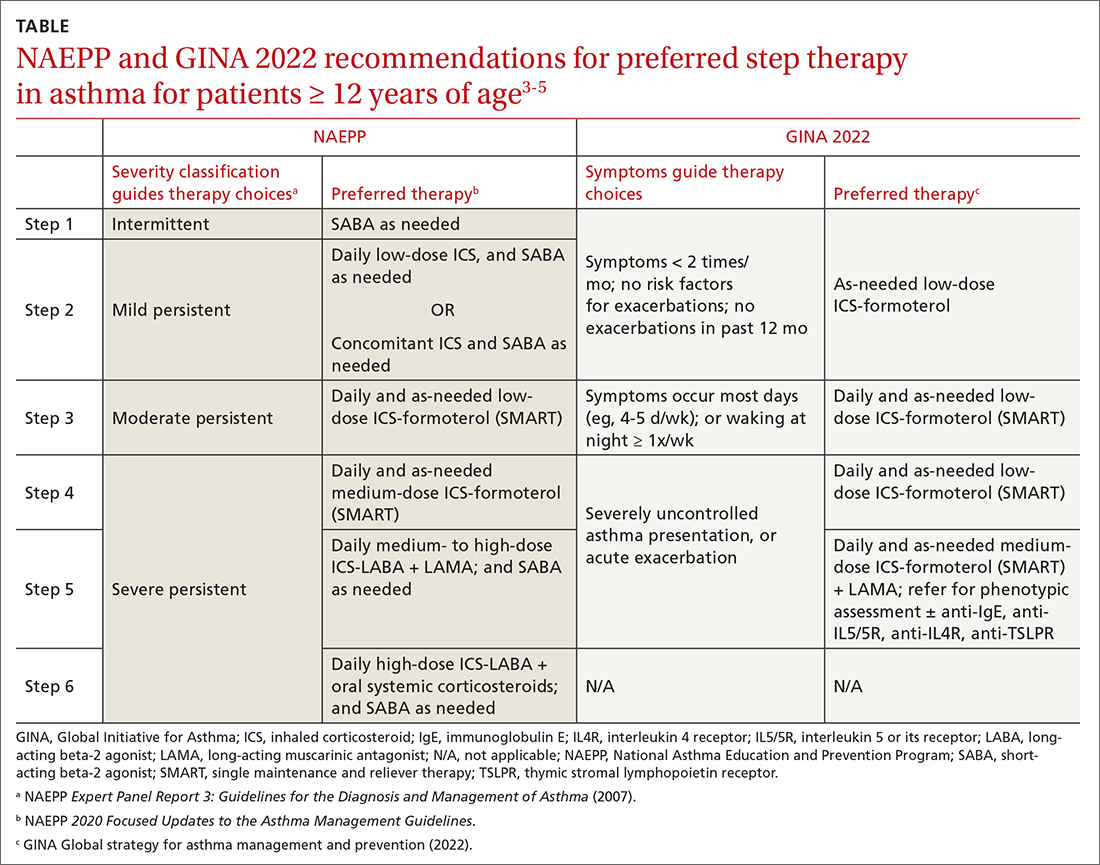

ICSs continue to be the primary controller treatment for patients with asthma. However, the NAEPP and GINA have provided different guidance on how to initiate step therapy (TABLE3-5). NAEPP focuses on severity classification, while GINA recommends treatment initiation based on presenting symptoms. Since both guidelines recommend early follow-up and adjustment of therapy according to level of control, this difference becomes less apparent in ongoing care.

A more fundamental difference is seen in the recommended therapies for each step (TABLE3-5). Whereas the 2020 Focused Updates prefers a SABA as needed in step 1, GINA favors a low-dose combination of ICS-formoterol as needed. The GINA recommendation is driven by supportive evidence for early initiation of low-dose ICS in any patient with asthma for greater improvement in lung function. This also addresses concerns that overuse of as-needed SABAs may increase the risk for severe exacerbations. Evidence also indicates that the risk for asthma-related death and urgent asthma-related health care increases when a patient takes a SABA as needed as monotherapy compared with ICS therapy, even with good symptom control.7,8

Continue to: Dosing of an ICS

Dosing of an ICS is based on step therapy regardless of the guideline used and is given at a total daily amount—low, medium, and high—for each age group. When initiating an ICS, consider differences between available treatment options (eg, cost, administration technique, likely patient adherence, patient preferences) and employ shared decision-making strategies. Dosing may need to be limited depending on the commercially available product, especially when used in combination with a LABA. However, as GINA emphasizes, a low-dose ICS provides the most clinical benefit. A high-dose ICS is needed by very few patients and is associated with greater risk for local and systemic adverse effects, such as adrenal suppression. With these considerations, both guidelines recommend using the lowest effective ICS dose and stepping up and down according to the patient’s comfort level.

Give an ICS time to work. Although an ICS can begin to reduce inflammation within days of initiation, the full benefit may be evident only after 2 to 3 months.4 Once the patient’s asthma is well controlled for 3 months, stepping down the dose can be considered and approached carefully. Complete cessation of ICSs is associated with significantly higher risk for exacerbations. Therefore, a general recommendation is to step down an ICS by 50% or reduce ICS-LABA from twice-daily administration to once daily. Risk for exacerbation after step-down therapy is heightened if the patient has a history of exacerbation or an emergency department visit in the past 12 months, a low baseline FEV1, or a loss of control during a dose reduction (ie, airway hyperresponsiveness and sputum eosinophilia).

Weigh the utility of FeNO measurement. The 2020 Focused Updates also recommend considering FeNO measurement to guide treatment choice and monitoring, although this is based on overall low certainty of evidence.5 GINA affirms the mixed evidence for FeNO, stating that while a few studies have shown significantly reduced exacerbations among children, adolescents, and pregnant women with FeNO-guided treatment, other studies have shown no significant difference in exacerbations.4,9-15 At this time, the role for FeNO in asthma management remains inconclusive, and access to it is limited across primary care settings.

When assessing response to ICS therapy (and before stepping up therapy), consider patient adherence, inhaler technique, whether allergen exposure is persistent, and possible comorbidities. Inhaler technique can be especially challenging, as each inhaler varies in appearance and operation. Employ patient education strategies (eg, videos, demonstration, teach-back methods). If stepping up therapy is indicated, adding a LABA is recommended over increasing the ICS dose. Since asthma is variable, stepping up therapy can be tried and reassessed in 2 to 3 months.

SMART is preferred

Single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) with ICS-formoterol, used as needed, is the preferred therapy for steps 3 and 4 in both GINA recommendations and the 2020 Focused Updates (TABLE3-5). GINA also prefers SMART for step 5. The recommended SMART combination that has been studied contains budesonide (or beclomethasone, not available in combination in the United States) for the ICS and formoterol for the LABA in a single inhaler that is used both daily for control and as needed for rescue therapy.

Continue to: Other ICS-formoterol...

Other ICS-formoterol or ICS-LABA combinations can be considered for controller therapy, especially those described in the NAEPP and GINA alternative step therapy recommendations. However, SMART has been more effective than other combinations in reducing exacerbations and provides similar or better levels of control at lower average ICS doses (compared with ICS-LABA with SABA or ICS with SABA) for adolescent and adult patients.3,4 As patients use greater amounts of ICS-formoterol during episodes of increased symptoms, this additional ICS may augment the anti-inflammatory effects. SMART may also improve adherence, especially among those who confuse multiple inhalers.

SMART is also recommended for use in children. Specifically, from the 2020 Focused Updates, any patient ≥ 4 years of age with a severe exacerbation in the past year is a good SMART candidate. Also consider SMART before higher-dose ICS-LABA and SABA as needed. Additional benefits in this younger patient population are fewer medical visits or less systemic corticosteroid use with improved control and quality of life.

Caveats. Patients who have a difficult time recognizing symptoms may not be good candidates for SMART, due to the potential for taking higher or lower ICS doses than necessary.

SMART specifically refers to formoterol combinations that produce bronchodilation within 1 to 3 minutes.16 For example, the SMART strategy is not recommended for patients using ICS-salmeterol as controller therapy.

Although guideline supported, SMART options are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use as reliever therapy.

Continue to: With the single combination...

With the single combination inhaler, consider the dosing limits of formoterol. The maximum daily amount of formoterol for adolescents and adults is 54 μg (12 puffs) delivered with the budesonide-formoterol metered dose inhaler. When using SMART as reliever therapy, the low-dose ICS-formoterol recommendation remains. However, depending on insurance coverage, a 1-month supply of ICS-formoterol may not be sufficient for additional reliever therapy use.

The role of LAMAs as add-on therapy

Bronchiolar smooth muscle tone is mediated by complex mechanisms that include cholinergic stimulation at muscarinic (M3) receptors.17 LAMAs, a mainstay in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are likely to be effective in reducing asthma exacerbations and the need for oral steroids. When patients have not achieved control at step 4 of asthma therapy, both the 2020 Focused Updates and GINA now recommend considering a LAMA (eg, tiotropium) as add-on therapy for patients > 12 years of age already taking medium-dose ICS-LABA for modest improvements in lung function and reductions in severe exacerbations. GINA recommendations also now include a LAMA as add-on treatment for those ages 6 to 11 years, as some evidence supports the use in school-aged children.18 It is important to note that LAMAs should not replace a LABA for treatment, as the ICS-LABA combination is likely more effective than ICS-LAMA.

Addressing asthma-COPD overlap

Asthma and COPD are frequently and frustratingly intertwined without clear demarcation. This tends to occur as patients age and chronic lung changes appear from longstanding asthma. However, it is important to distinguish between these conditions, because there are clearly delineated treatments for each that can improve outcomes.

The priority in addressing asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) is to evaluate symptoms and determine if asthma or COPD is predominant.19 This includes establishing patient age at which symptoms began, variation and triggers of symptoms, and history of exposures to smoke/environmental respiratory toxins. Age 40 years is often used as the tipping point at which symptom onset favors a diagnosis of COPD. Serial spirometry may also be used to evaluate lung function over time and persistence of disease. If a firm diagnosis is evasive, consider a referral to a pulmonary specialist for further testing.

Choosing to use an ICS or LAMA depends on which underlying disorder is more likely. While early COPD management includes LAMA + LABA, the addition of an ICS is reserved for more severe disease. High-dose ICSs, particularly fluticasone, should be limited in COPD due to an increased risk for pneumonia. For asthma or ACO, the addition of an ICS is critical and prioritized to reduce airway inflammation and risk for exacerbations and death. While a LAMA is likely useful earlier in ACO, it is not used until step 5 of asthma therapy. Given the complexities of ACO treatment, further research is needed to provide adequate guidance.

CASE

For Ms. S, you would be wise to use an ICS-formoterol combination for as-needed symptom relief. If symptoms were more persistent, you could consider recommending the ICS-formoterol inhaler as SMART therapy, with regular doses taken twice daily and extra doses taken as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 2426 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; [email protected]

1. CDC. Most recent national asthma data. Accessed October 24, 2022. www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm

2. Akinbami LJ, Santo L, Williams S, et al. Characteristics of asthma visits to physician offices in the United States: 2012–2015 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2019;128:1-20.

3. NHLBI. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH Publication 07-4051. 2007. Accessed October 24, 2022. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/EPR-3_Asthma_Full_Report_2007.pdf

4. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf

5. NHLBI. 2020 Focused updates to the asthma management guidelines. Accessed October 24, 2022. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/all-publications-and-resources/2020-focused-updates-asthma-management-guidelines

6. Lazarus SC, Krishnan JA, King TS, et al. Mometasone or tiotropium in mild asthma with a low sputum eosinophil level. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2009-2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814917

7. Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, et al. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-336. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430504

8. Suissa S, Ernst P, Kezouh A. Regular use of inhaled corticosteroids and the long term prevention of hospitalisation for asthma. Thorax. 2002;57:880-884. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.880

9. Szefler SJ, Mitchell H, Sorkness CA, et al. Management of asthma based on exhaled nitric oxide in addition to guideline-based treatment for inner-city adolescents and young adults: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1065-1072. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61448-8

10. Calhoun WJ, Ameredes BT, King TS, et al. Comparison of physician-, biomarker-, and symptom-based strategies for adjustment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adults with asthma: the BASALT randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308:987-997. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10893

11. Garg Y, Kakria N, Katoch CDS, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide as a guiding tool for bronchial asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76:17-22. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2018.02.001

12. Honkoop PJ, Loijmans RJ, Termeer EH, et al. Symptom- and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide-driven strategies for asthma control: a cluster-randomized trial in primary care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:682-8.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.016

13. Peirsman EJ, Carvelli TJ, Hage PY, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide in childhood allergic asthma management: a randomised controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:624-631. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22873

14. Powell H, Murphy VE, Taylor DR, et al. Management of asthma in pregnancy guided by measurement of fraction of exhaled nitric oxide: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:983-990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60971-9

15. Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, et al. The use of exhaled nitric oxide to guide asthma management: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:231-237. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1427OC

16. Stam J, Souren M, Zweers P. The onset of action of formoterol, a new beta 2 adrenoceptor agonist. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1993;31:23-26.

17. Evgenov OV, Liang Y, Jiang Y, et al. Pulmonary pharmacology and inhaled anesthetics. In: Gropper MA, Miller RD, Evgenov O, et al, eds. Miller’s Anesthesia. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020:540-571.

18. Rodrigo GJ, Neffen H. Efficacy and safety of tiotropium in school-age children with moderate-to-severe symptomatic asthma: a systematic review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:573-578. doi: 10.1111/pai.12759

19. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Asthma, COPD, and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). 2015. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GOLD_ACOS_2015.pdf

CASE

Erica S*, age 22, has intermittent asthma and presents to your clinic to discuss refills of her albuterol inhaler. Two years ago, she was hospitalized for a severe asthma exacerbation because she was unable to afford medications. Since then, her asthma has generally been well controlled, and she needs to use albuterol only 1 or 2 times per month. Ms. S says she has no morning chest tightness or nocturnal coughing, but she does experience increased wheezing and shortness of breath with activity.

What would you recommend? Would your recommendation differ if she had persistent asthma?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity .

As of 2020, more than 20 million adults and 4 million children younger than 18 years of age in the United States were living with asthma.1 In 2019 alone, there were more than 1.8 million asthma-related emergency department visits for adults, and more than 790,000 asthma-related emergency department visits for children. Asthma caused more than 4000 deaths in the United States in 2020.1 Given the scale of the burden of asthma, it is not surprising that approximately 60% of all asthma visits occur in primary care settings,2 making it essential that primary care physicians stay abreast of recent developments in asthma diagnosis and management.

Since 1991, the major guidance on best practices for asthma management in the United States has been provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)’s National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP). Its last major update on asthma was released in 2007 as the Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3).3 Since that time, there has been significant progress in our understanding of asthma as a complex spectrum of phenotypes, which has advanced our knowledge of pathophysiology and helped refine treatment. In contrast to the NAEPP, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has published annual updates on asthma management incorporating up-to-date information.4 In response to the continuously evolving body of knowledge on asthma, the NAEPP Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group published the 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines.5

Given the vast resources available on asthma, our purpose in this article is not to provide a comprehensive review of the stepwise approach to asthma management, but instead to summarize the major points presented in the 2020 Focused Updates and how these compare and contrast with the latest guidance from GINA.

A heterogeneous disease

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by both variable symptoms and airflow limitation that change over time, often in response to external triggers such as exercise, allergens, and viral respiratory infections. Common symptoms include wheezing, cough, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. Despite the common symptomatology, asthma is a heterogeneous disease with several recognizable phenotypes including allergic, nonallergic, and asthma with persistent airflow limitation.

Continue to: The airflow limitation...

The airflow limitation in asthma occurs through both airway hyperresponsiveness to external stimuli and chronic airway inflammation. Airway constriction is regulated by nerves to the smooth muscles of the airway. Beta-2 nerve receptors have long been the target of asthma therapy with both short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABAs) as rescue treatment and long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABAs) as maintenance therapy.3,4 However, there is increasing evidence that cholinergic nerves also have a role in airway regulation in asthma, and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) have recently shown benefit as add-on therapy in some types of asthma.4-6 Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) have long held an important role in reducing airway inflammation, especially in the setting of allergic or eosinophilic inflammation.3-5

Spirometry is essential to asthma Dx—but what about FeNO?

The mainstay of asthma diagnosis is confirming both a history of variable respiratory symptoms and variable expiratory airflow limitation exhibited by spirometry. Obstruction is defined as a reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and as a decreased ratio of FEV1 over forced vital capacity (FVC) based on predicted values. An increase of at least 12% in FEV1 post bronchodilator use indicates asthma for adolescents and adults.

More recently, studies have examined the role of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in the diagnosis of asthma. The 2020 Focused Updates report states that FeNO may be useful when the diagnosis of asthma is uncertain using initial history, physical exam, and spirometry findings, or when spirometry cannot be performed reliably.5 Levels of FeNO > 50 ppb make eosinophilic inflammation and treatment response to an ICS more likely. FeNO levels < 25 ppb make inflammatory asthma less likely and should prompt a search for an alternate diagnosis.5 For patients with FeNO of 25 to 50 ppb, more detailed clinical context is needed. In contrast, the 2022 GINA updates conclude that FeNO is not yet an established diagnostic tool for asthma.4

Management

When to start and adjust an ICS

ICSs continue to be the primary controller treatment for patients with asthma. However, the NAEPP and GINA have provided different guidance on how to initiate step therapy (TABLE3-5). NAEPP focuses on severity classification, while GINA recommends treatment initiation based on presenting symptoms. Since both guidelines recommend early follow-up and adjustment of therapy according to level of control, this difference becomes less apparent in ongoing care.

A more fundamental difference is seen in the recommended therapies for each step (TABLE3-5). Whereas the 2020 Focused Updates prefers a SABA as needed in step 1, GINA favors a low-dose combination of ICS-formoterol as needed. The GINA recommendation is driven by supportive evidence for early initiation of low-dose ICS in any patient with asthma for greater improvement in lung function. This also addresses concerns that overuse of as-needed SABAs may increase the risk for severe exacerbations. Evidence also indicates that the risk for asthma-related death and urgent asthma-related health care increases when a patient takes a SABA as needed as monotherapy compared with ICS therapy, even with good symptom control.7,8

Continue to: Dosing of an ICS

Dosing of an ICS is based on step therapy regardless of the guideline used and is given at a total daily amount—low, medium, and high—for each age group. When initiating an ICS, consider differences between available treatment options (eg, cost, administration technique, likely patient adherence, patient preferences) and employ shared decision-making strategies. Dosing may need to be limited depending on the commercially available product, especially when used in combination with a LABA. However, as GINA emphasizes, a low-dose ICS provides the most clinical benefit. A high-dose ICS is needed by very few patients and is associated with greater risk for local and systemic adverse effects, such as adrenal suppression. With these considerations, both guidelines recommend using the lowest effective ICS dose and stepping up and down according to the patient’s comfort level.

Give an ICS time to work. Although an ICS can begin to reduce inflammation within days of initiation, the full benefit may be evident only after 2 to 3 months.4 Once the patient’s asthma is well controlled for 3 months, stepping down the dose can be considered and approached carefully. Complete cessation of ICSs is associated with significantly higher risk for exacerbations. Therefore, a general recommendation is to step down an ICS by 50% or reduce ICS-LABA from twice-daily administration to once daily. Risk for exacerbation after step-down therapy is heightened if the patient has a history of exacerbation or an emergency department visit in the past 12 months, a low baseline FEV1, or a loss of control during a dose reduction (ie, airway hyperresponsiveness and sputum eosinophilia).

Weigh the utility of FeNO measurement. The 2020 Focused Updates also recommend considering FeNO measurement to guide treatment choice and monitoring, although this is based on overall low certainty of evidence.5 GINA affirms the mixed evidence for FeNO, stating that while a few studies have shown significantly reduced exacerbations among children, adolescents, and pregnant women with FeNO-guided treatment, other studies have shown no significant difference in exacerbations.4,9-15 At this time, the role for FeNO in asthma management remains inconclusive, and access to it is limited across primary care settings.

When assessing response to ICS therapy (and before stepping up therapy), consider patient adherence, inhaler technique, whether allergen exposure is persistent, and possible comorbidities. Inhaler technique can be especially challenging, as each inhaler varies in appearance and operation. Employ patient education strategies (eg, videos, demonstration, teach-back methods). If stepping up therapy is indicated, adding a LABA is recommended over increasing the ICS dose. Since asthma is variable, stepping up therapy can be tried and reassessed in 2 to 3 months.

SMART is preferred

Single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) with ICS-formoterol, used as needed, is the preferred therapy for steps 3 and 4 in both GINA recommendations and the 2020 Focused Updates (TABLE3-5). GINA also prefers SMART for step 5. The recommended SMART combination that has been studied contains budesonide (or beclomethasone, not available in combination in the United States) for the ICS and formoterol for the LABA in a single inhaler that is used both daily for control and as needed for rescue therapy.

Continue to: Other ICS-formoterol...

Other ICS-formoterol or ICS-LABA combinations can be considered for controller therapy, especially those described in the NAEPP and GINA alternative step therapy recommendations. However, SMART has been more effective than other combinations in reducing exacerbations and provides similar or better levels of control at lower average ICS doses (compared with ICS-LABA with SABA or ICS with SABA) for adolescent and adult patients.3,4 As patients use greater amounts of ICS-formoterol during episodes of increased symptoms, this additional ICS may augment the anti-inflammatory effects. SMART may also improve adherence, especially among those who confuse multiple inhalers.

SMART is also recommended for use in children. Specifically, from the 2020 Focused Updates, any patient ≥ 4 years of age with a severe exacerbation in the past year is a good SMART candidate. Also consider SMART before higher-dose ICS-LABA and SABA as needed. Additional benefits in this younger patient population are fewer medical visits or less systemic corticosteroid use with improved control and quality of life.

Caveats. Patients who have a difficult time recognizing symptoms may not be good candidates for SMART, due to the potential for taking higher or lower ICS doses than necessary.

SMART specifically refers to formoterol combinations that produce bronchodilation within 1 to 3 minutes.16 For example, the SMART strategy is not recommended for patients using ICS-salmeterol as controller therapy.

Although guideline supported, SMART options are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use as reliever therapy.

Continue to: With the single combination...

With the single combination inhaler, consider the dosing limits of formoterol. The maximum daily amount of formoterol for adolescents and adults is 54 μg (12 puffs) delivered with the budesonide-formoterol metered dose inhaler. When using SMART as reliever therapy, the low-dose ICS-formoterol recommendation remains. However, depending on insurance coverage, a 1-month supply of ICS-formoterol may not be sufficient for additional reliever therapy use.

The role of LAMAs as add-on therapy

Bronchiolar smooth muscle tone is mediated by complex mechanisms that include cholinergic stimulation at muscarinic (M3) receptors.17 LAMAs, a mainstay in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are likely to be effective in reducing asthma exacerbations and the need for oral steroids. When patients have not achieved control at step 4 of asthma therapy, both the 2020 Focused Updates and GINA now recommend considering a LAMA (eg, tiotropium) as add-on therapy for patients > 12 years of age already taking medium-dose ICS-LABA for modest improvements in lung function and reductions in severe exacerbations. GINA recommendations also now include a LAMA as add-on treatment for those ages 6 to 11 years, as some evidence supports the use in school-aged children.18 It is important to note that LAMAs should not replace a LABA for treatment, as the ICS-LABA combination is likely more effective than ICS-LAMA.

Addressing asthma-COPD overlap

Asthma and COPD are frequently and frustratingly intertwined without clear demarcation. This tends to occur as patients age and chronic lung changes appear from longstanding asthma. However, it is important to distinguish between these conditions, because there are clearly delineated treatments for each that can improve outcomes.

The priority in addressing asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) is to evaluate symptoms and determine if asthma or COPD is predominant.19 This includes establishing patient age at which symptoms began, variation and triggers of symptoms, and history of exposures to smoke/environmental respiratory toxins. Age 40 years is often used as the tipping point at which symptom onset favors a diagnosis of COPD. Serial spirometry may also be used to evaluate lung function over time and persistence of disease. If a firm diagnosis is evasive, consider a referral to a pulmonary specialist for further testing.

Choosing to use an ICS or LAMA depends on which underlying disorder is more likely. While early COPD management includes LAMA + LABA, the addition of an ICS is reserved for more severe disease. High-dose ICSs, particularly fluticasone, should be limited in COPD due to an increased risk for pneumonia. For asthma or ACO, the addition of an ICS is critical and prioritized to reduce airway inflammation and risk for exacerbations and death. While a LAMA is likely useful earlier in ACO, it is not used until step 5 of asthma therapy. Given the complexities of ACO treatment, further research is needed to provide adequate guidance.

CASE

For Ms. S, you would be wise to use an ICS-formoterol combination for as-needed symptom relief. If symptoms were more persistent, you could consider recommending the ICS-formoterol inhaler as SMART therapy, with regular doses taken twice daily and extra doses taken as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 2426 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; [email protected]

CASE

Erica S*, age 22, has intermittent asthma and presents to your clinic to discuss refills of her albuterol inhaler. Two years ago, she was hospitalized for a severe asthma exacerbation because she was unable to afford medications. Since then, her asthma has generally been well controlled, and she needs to use albuterol only 1 or 2 times per month. Ms. S says she has no morning chest tightness or nocturnal coughing, but she does experience increased wheezing and shortness of breath with activity.

What would you recommend? Would your recommendation differ if she had persistent asthma?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity .

As of 2020, more than 20 million adults and 4 million children younger than 18 years of age in the United States were living with asthma.1 In 2019 alone, there were more than 1.8 million asthma-related emergency department visits for adults, and more than 790,000 asthma-related emergency department visits for children. Asthma caused more than 4000 deaths in the United States in 2020.1 Given the scale of the burden of asthma, it is not surprising that approximately 60% of all asthma visits occur in primary care settings,2 making it essential that primary care physicians stay abreast of recent developments in asthma diagnosis and management.

Since 1991, the major guidance on best practices for asthma management in the United States has been provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)’s National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP). Its last major update on asthma was released in 2007 as the Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3).3 Since that time, there has been significant progress in our understanding of asthma as a complex spectrum of phenotypes, which has advanced our knowledge of pathophysiology and helped refine treatment. In contrast to the NAEPP, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has published annual updates on asthma management incorporating up-to-date information.4 In response to the continuously evolving body of knowledge on asthma, the NAEPP Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group published the 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines.5

Given the vast resources available on asthma, our purpose in this article is not to provide a comprehensive review of the stepwise approach to asthma management, but instead to summarize the major points presented in the 2020 Focused Updates and how these compare and contrast with the latest guidance from GINA.

A heterogeneous disease

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by both variable symptoms and airflow limitation that change over time, often in response to external triggers such as exercise, allergens, and viral respiratory infections. Common symptoms include wheezing, cough, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. Despite the common symptomatology, asthma is a heterogeneous disease with several recognizable phenotypes including allergic, nonallergic, and asthma with persistent airflow limitation.

Continue to: The airflow limitation...

The airflow limitation in asthma occurs through both airway hyperresponsiveness to external stimuli and chronic airway inflammation. Airway constriction is regulated by nerves to the smooth muscles of the airway. Beta-2 nerve receptors have long been the target of asthma therapy with both short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABAs) as rescue treatment and long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABAs) as maintenance therapy.3,4 However, there is increasing evidence that cholinergic nerves also have a role in airway regulation in asthma, and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) have recently shown benefit as add-on therapy in some types of asthma.4-6 Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) have long held an important role in reducing airway inflammation, especially in the setting of allergic or eosinophilic inflammation.3-5

Spirometry is essential to asthma Dx—but what about FeNO?

The mainstay of asthma diagnosis is confirming both a history of variable respiratory symptoms and variable expiratory airflow limitation exhibited by spirometry. Obstruction is defined as a reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and as a decreased ratio of FEV1 over forced vital capacity (FVC) based on predicted values. An increase of at least 12% in FEV1 post bronchodilator use indicates asthma for adolescents and adults.

More recently, studies have examined the role of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in the diagnosis of asthma. The 2020 Focused Updates report states that FeNO may be useful when the diagnosis of asthma is uncertain using initial history, physical exam, and spirometry findings, or when spirometry cannot be performed reliably.5 Levels of FeNO > 50 ppb make eosinophilic inflammation and treatment response to an ICS more likely. FeNO levels < 25 ppb make inflammatory asthma less likely and should prompt a search for an alternate diagnosis.5 For patients with FeNO of 25 to 50 ppb, more detailed clinical context is needed. In contrast, the 2022 GINA updates conclude that FeNO is not yet an established diagnostic tool for asthma.4

Management

When to start and adjust an ICS

ICSs continue to be the primary controller treatment for patients with asthma. However, the NAEPP and GINA have provided different guidance on how to initiate step therapy (TABLE3-5). NAEPP focuses on severity classification, while GINA recommends treatment initiation based on presenting symptoms. Since both guidelines recommend early follow-up and adjustment of therapy according to level of control, this difference becomes less apparent in ongoing care.

A more fundamental difference is seen in the recommended therapies for each step (TABLE3-5). Whereas the 2020 Focused Updates prefers a SABA as needed in step 1, GINA favors a low-dose combination of ICS-formoterol as needed. The GINA recommendation is driven by supportive evidence for early initiation of low-dose ICS in any patient with asthma for greater improvement in lung function. This also addresses concerns that overuse of as-needed SABAs may increase the risk for severe exacerbations. Evidence also indicates that the risk for asthma-related death and urgent asthma-related health care increases when a patient takes a SABA as needed as monotherapy compared with ICS therapy, even with good symptom control.7,8

Continue to: Dosing of an ICS

Dosing of an ICS is based on step therapy regardless of the guideline used and is given at a total daily amount—low, medium, and high—for each age group. When initiating an ICS, consider differences between available treatment options (eg, cost, administration technique, likely patient adherence, patient preferences) and employ shared decision-making strategies. Dosing may need to be limited depending on the commercially available product, especially when used in combination with a LABA. However, as GINA emphasizes, a low-dose ICS provides the most clinical benefit. A high-dose ICS is needed by very few patients and is associated with greater risk for local and systemic adverse effects, such as adrenal suppression. With these considerations, both guidelines recommend using the lowest effective ICS dose and stepping up and down according to the patient’s comfort level.

Give an ICS time to work. Although an ICS can begin to reduce inflammation within days of initiation, the full benefit may be evident only after 2 to 3 months.4 Once the patient’s asthma is well controlled for 3 months, stepping down the dose can be considered and approached carefully. Complete cessation of ICSs is associated with significantly higher risk for exacerbations. Therefore, a general recommendation is to step down an ICS by 50% or reduce ICS-LABA from twice-daily administration to once daily. Risk for exacerbation after step-down therapy is heightened if the patient has a history of exacerbation or an emergency department visit in the past 12 months, a low baseline FEV1, or a loss of control during a dose reduction (ie, airway hyperresponsiveness and sputum eosinophilia).

Weigh the utility of FeNO measurement. The 2020 Focused Updates also recommend considering FeNO measurement to guide treatment choice and monitoring, although this is based on overall low certainty of evidence.5 GINA affirms the mixed evidence for FeNO, stating that while a few studies have shown significantly reduced exacerbations among children, adolescents, and pregnant women with FeNO-guided treatment, other studies have shown no significant difference in exacerbations.4,9-15 At this time, the role for FeNO in asthma management remains inconclusive, and access to it is limited across primary care settings.

When assessing response to ICS therapy (and before stepping up therapy), consider patient adherence, inhaler technique, whether allergen exposure is persistent, and possible comorbidities. Inhaler technique can be especially challenging, as each inhaler varies in appearance and operation. Employ patient education strategies (eg, videos, demonstration, teach-back methods). If stepping up therapy is indicated, adding a LABA is recommended over increasing the ICS dose. Since asthma is variable, stepping up therapy can be tried and reassessed in 2 to 3 months.

SMART is preferred

Single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) with ICS-formoterol, used as needed, is the preferred therapy for steps 3 and 4 in both GINA recommendations and the 2020 Focused Updates (TABLE3-5). GINA also prefers SMART for step 5. The recommended SMART combination that has been studied contains budesonide (or beclomethasone, not available in combination in the United States) for the ICS and formoterol for the LABA in a single inhaler that is used both daily for control and as needed for rescue therapy.

Continue to: Other ICS-formoterol...

Other ICS-formoterol or ICS-LABA combinations can be considered for controller therapy, especially those described in the NAEPP and GINA alternative step therapy recommendations. However, SMART has been more effective than other combinations in reducing exacerbations and provides similar or better levels of control at lower average ICS doses (compared with ICS-LABA with SABA or ICS with SABA) for adolescent and adult patients.3,4 As patients use greater amounts of ICS-formoterol during episodes of increased symptoms, this additional ICS may augment the anti-inflammatory effects. SMART may also improve adherence, especially among those who confuse multiple inhalers.

SMART is also recommended for use in children. Specifically, from the 2020 Focused Updates, any patient ≥ 4 years of age with a severe exacerbation in the past year is a good SMART candidate. Also consider SMART before higher-dose ICS-LABA and SABA as needed. Additional benefits in this younger patient population are fewer medical visits or less systemic corticosteroid use with improved control and quality of life.

Caveats. Patients who have a difficult time recognizing symptoms may not be good candidates for SMART, due to the potential for taking higher or lower ICS doses than necessary.

SMART specifically refers to formoterol combinations that produce bronchodilation within 1 to 3 minutes.16 For example, the SMART strategy is not recommended for patients using ICS-salmeterol as controller therapy.

Although guideline supported, SMART options are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use as reliever therapy.

Continue to: With the single combination...

With the single combination inhaler, consider the dosing limits of formoterol. The maximum daily amount of formoterol for adolescents and adults is 54 μg (12 puffs) delivered with the budesonide-formoterol metered dose inhaler. When using SMART as reliever therapy, the low-dose ICS-formoterol recommendation remains. However, depending on insurance coverage, a 1-month supply of ICS-formoterol may not be sufficient for additional reliever therapy use.

The role of LAMAs as add-on therapy

Bronchiolar smooth muscle tone is mediated by complex mechanisms that include cholinergic stimulation at muscarinic (M3) receptors.17 LAMAs, a mainstay in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are likely to be effective in reducing asthma exacerbations and the need for oral steroids. When patients have not achieved control at step 4 of asthma therapy, both the 2020 Focused Updates and GINA now recommend considering a LAMA (eg, tiotropium) as add-on therapy for patients > 12 years of age already taking medium-dose ICS-LABA for modest improvements in lung function and reductions in severe exacerbations. GINA recommendations also now include a LAMA as add-on treatment for those ages 6 to 11 years, as some evidence supports the use in school-aged children.18 It is important to note that LAMAs should not replace a LABA for treatment, as the ICS-LABA combination is likely more effective than ICS-LAMA.

Addressing asthma-COPD overlap

Asthma and COPD are frequently and frustratingly intertwined without clear demarcation. This tends to occur as patients age and chronic lung changes appear from longstanding asthma. However, it is important to distinguish between these conditions, because there are clearly delineated treatments for each that can improve outcomes.

The priority in addressing asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) is to evaluate symptoms and determine if asthma or COPD is predominant.19 This includes establishing patient age at which symptoms began, variation and triggers of symptoms, and history of exposures to smoke/environmental respiratory toxins. Age 40 years is often used as the tipping point at which symptom onset favors a diagnosis of COPD. Serial spirometry may also be used to evaluate lung function over time and persistence of disease. If a firm diagnosis is evasive, consider a referral to a pulmonary specialist for further testing.

Choosing to use an ICS or LAMA depends on which underlying disorder is more likely. While early COPD management includes LAMA + LABA, the addition of an ICS is reserved for more severe disease. High-dose ICSs, particularly fluticasone, should be limited in COPD due to an increased risk for pneumonia. For asthma or ACO, the addition of an ICS is critical and prioritized to reduce airway inflammation and risk for exacerbations and death. While a LAMA is likely useful earlier in ACO, it is not used until step 5 of asthma therapy. Given the complexities of ACO treatment, further research is needed to provide adequate guidance.

CASE

For Ms. S, you would be wise to use an ICS-formoterol combination for as-needed symptom relief. If symptoms were more persistent, you could consider recommending the ICS-formoterol inhaler as SMART therapy, with regular doses taken twice daily and extra doses taken as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 2426 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; [email protected]

1. CDC. Most recent national asthma data. Accessed October 24, 2022. www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm

2. Akinbami LJ, Santo L, Williams S, et al. Characteristics of asthma visits to physician offices in the United States: 2012–2015 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2019;128:1-20.

3. NHLBI. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH Publication 07-4051. 2007. Accessed October 24, 2022. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/EPR-3_Asthma_Full_Report_2007.pdf

4. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf

5. NHLBI. 2020 Focused updates to the asthma management guidelines. Accessed October 24, 2022. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/all-publications-and-resources/2020-focused-updates-asthma-management-guidelines

6. Lazarus SC, Krishnan JA, King TS, et al. Mometasone or tiotropium in mild asthma with a low sputum eosinophil level. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2009-2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814917

7. Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, et al. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-336. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430504

8. Suissa S, Ernst P, Kezouh A. Regular use of inhaled corticosteroids and the long term prevention of hospitalisation for asthma. Thorax. 2002;57:880-884. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.880